Mā ngā korero tuku iho tātou me ō tātou ao e kitea ai, e rongongia ai, e whaiora ai.[1]

E tatou te fauina i tatou ma a tatou si’osi’omaga, e ala iā tatou tala.[2]

We craft ourselves and our worlds in stories.

Understand Me was born out of an aspirational exploration of ways for teachers to deepen relationships with young children and families to open space for their knowledges to be valued in the everyday educational curriculum. The origin was a desire to facilitate a shift from awareness of cultural competencies to action that values family pedagogies in the learning life of the classroom. Family pedagogies are everyday ways of knowing, learning, and teaching within a family, across generations (see Delgado Bernal, 2001; Jacobs et al., 2021; Skerrett & Ritchie, 2019). We were searching for a different way of seeing, being with and entering each other’s worlds to better understand the languages, cultures and experiences of a child and their family in the school context.[3]

We envisioned storied-conversations as reciprocal multi-modal interactions, co-created in the everyday being-listening-telling of children, families and teachers. The stories, shared within belonging conversations, are precious taonga (treasures) that strengthen relationships and amplify learning and teaching through invited reflection.

The essence of storied-conversations is crystallised in the name of the project, Understand Me, derived from a report of former New Zealand Children’s Commissioner (2018) Judge Andrew Becroft, for which over a hundred tamariki (children) and rangatahi (youth) were interviewed. A Māori boy who had been interviewed expressed his desire to have teachers who understood his identity as Māori, saying: “If they can’t understand me, how can I understand them?” (p. 9). Through storied-conversations, children and the adults who care for them story their worlds and selves, forging a pathway of understanding for relational-cultural knowledge sharing from home to school.

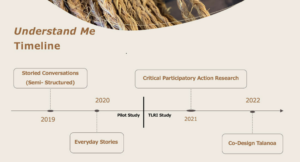

We searched for a school that was already on the path of reaching out to families to invite their knowledges into the school. We knew that undertaking this project in a school that was not on such a path would be too challenging otherwise. Papatoetoe North School (PNS) accepted us as partners on their journey in 2019. See Figure 1 for the transitions of the study over time. PNS is a large (N = 750–860) Years 1 to 6 school that represents the superdiversity of Auckland (44% Pacific heritage with 24% Samoan, 28% Indian and 22% Māori). English is an additional language for 30% of the students. Key strengths of the school noted by the Education Review Office (2018) were: a culture of high expectations; educationally powerful relationships with parents, whānau and community that positively impact on learning outcomes for children; and support programmes for children with additional learning needs.

Our cultural-locatedness as researchers does not fully represent the diverse worldviews of the children, families, and teachers who contributed to the project. Marieta is Samoan-born, Jacoba is Samoan-Dutch, Jan and Meg are American of European descent, and Alison was born in Hong Kong (see Author Bios). Marieta’s leadership was central to sustaining the project and sharing the school’s understanding of the mili le afa metaphor (explained in detail in the methodology section). We are the designated co-authors within the larger collective (see Author Note for names and positions).

As encapsulated in the opening maxim, if our stories are us and we craft ourselves and our worlds in stories, how might the sharing of memorable stories create openings for understanding a child’s world? (Gaffney et al., 2019, p. 6). To begin to find out, we undertook a pilot study in 2019 in which we engaged with a child, their whānau and teacher, sharing stories in triads for an hour at three intervals. In the third session (which involved video-stimulated reflections), the child, whānau and teacher responded to brief video snippets of the first two storying sessions. While these storied-conversations clearly opened space to enrich children’s school learning experiences, the formal structure needed to be eased (Appendix A: Co-design Evolution). This challenge shaped the next steps we took in the project, the evolution of which is depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1 Timeline of Design Evolution of Understand Me, by Year

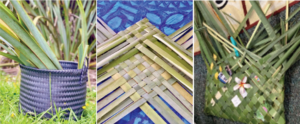

The five teachers who had participated in the initial year of the pilot study shared their experiences with teachers new to the project and with the School Leadership Team (Gaffney, 2019–2020). From their spoken words, Jacoba Matapo (2020) created a poem that continues to nurture and inspire children and teachers (see Appendix B: Understand Me Poem). Teachers were invited to think more broadly about stories and where storying takes place. How do we move forward naturally? We met with teachers approximately every other month in design hui, sharing noticings and reflections. In the final session of the pilot study, we gathered on the mat in the school library, which depicted a map of Samoa. We wove our stories, literally and figuratively, into a kete, using harakeke that Jacoba and her daughter had gathered for the purpose (see Figure 2). The kete, intentionally unfinished, is displayed in a place of pride in the Staff Room along with the poem.

Figure 2 The Harakeke, Initial Weaving and Unfinished Kete from Finale Session (3 March 2020)

Out of the conversations with teachers in the design hui, ideas, like seedlings tracking sunlight, found their way above ground. Together, we wondered about the value of stories to inform teaching practice. We were re-shaping our notions of storying to open up to everyday noticing, to celebrate the mundane and to view stories as beyond words, embodied, connecting, disconnecting, reconnecting to fluid identities in relationship to this place. Our notions of storying were also informed by a whisper of caution – to not assume which stories are the most important to share. Building on the momentum of the pilot study, the Teaching Learning Research Initiative (TLRI, Gaffney & Jacobs, 2020) supported the expansion of Understand Me to additional schools and allowed for younger siblings of whānau already attending school to engage in the project.

Understand Me is grounded in three research questions that evolved from the pilot study:

Research Questions

- How might a child, parent and teacher better see and understand each other’s worlds through storied-conversations?

- How might knowings, already existing in the everyday lives of children and families, forge a pathway from home to shape curriculum and pedagogies?

- How might educators embrace the tensions between the relational and the quantifiable to reimagine curriculum through storying with children and families?

As we branched to two more primary schools, we referred to PNS as the seed school. Our intent was to have each additional school, one in Northland and another in Auckland, shape Understand Me within their context. The two schools initiated participation in 2021 but for different reasons were unable to continue. Restrictions associated with Covid-19 closed schools and disrupted family interactions. However, the foundational roots of Understand Me at PNS not only sustained but expanded the project, with the number of participating teachers increasing each year (see Table 1). While we had originally planned to engage with three teachers across the three schools, we ultimately exceeded our goal for the total number of participating teachers within the single school. (See Appendix C for information about PNS project team members.)

| Year | Number of Teachers |

|---|---|

| 2019 (Pilot) | 5 |

| 2020 (Pilot) | 7 |

| 2021 (TLRI) | 11 |

| 2022 (TLRI) | 16* |

*One teacher withdrew in August.

Co-Design Methodology: Evolutions in Co-Design

The three schools invited to participate were onside with Understand Me from the conceptualisation of the proposal. Following orienting sessions to Understand Me and explaining ethics, teachers expressed their interest to a point person in the school and completed ethics consents. Given the intense relationality of the study, we engaged in individual, in-person, conversational one-hour interviews with each prospective teacher (i.e., 18 interviews in 2021 and 5 interviews in 2022). Conversation starters invited the teachers to share a bit about themselves: what had attracted them to the project; ways that they currently moved closer to children and families in their work; a memorable story about their teaching; what they value most about teaching; and the potential the project could have for their teaching, including what they wanted for their school. These conversations contributed to shared understanding and shared power, essential to this collective and reflective research.

The methodology used in this research from the pilot through the 2 years of this study has evolved in unexpected ways. The turns, or iterations, grew out of layered conversations with teachers and school leaders and discussions in research meetings. The changes, though seemingly subtle and naturally occurring, reflected substantial paradigm shifts. Three paradigmatic shifts were in (a) methodology, (b) positioning of storied-conversations and (c) inclusion of children younger than 5 years old.

Shifts in Methodology

Unlike traditional research, the description provided in this section could not have been written before we started. Rather the co-design methodology is a manifestation of the shared partnerships within the project. We initiated the TLRI study using critical participatory action research (CPAR; Kemmis & McTaggart, 2014). The CPAR approach evolved into ongoing co-design talanoa. Co-design demonstrated an openness towards the fluid nature of the research design as well as methods of interactions and ways of reconceptualising data. The use of talanoa (Vaioleti, 2006) as the apt descriptor for the approach arose from collective conversations with teachers and school leaders. Talanoa as a method of ongoing co-design prioritised relational and cultural interactions in this space intentionally created for connection and dialogue. These co-agential interactions preceded the naming of the approach.

The co-design talanoa sessions were a safe and caring space for collective sharing – a space for teachers to slow down and reflect on their noticing of and, listening and attending to everyday stories in whatever ways children and families chose to tell them. The teachers presenced themselves in these lived moments to enter the worlds of children, their families and each other. The teachers leaned in and leaned back, cherishing what mattered to their colleagues and presencing new pathways of potentialities as they co-created their ongoing transformative story. The university researchers thoughtfully planned a provocation to animate each session and engaged in talanoa with teachers. The teachers valued these sessions, as they chose to participate in the 1- to 1.5-hour sessions at 7:30 am (and we think it was more than the muffins).

The shape of each year was composed of a welcoming session in Term 1 in which teachers shared their reflections from the previous year with prospective teachers and the School Leadership Team. The finale sessions early in Term 4 reflected the epitome of deep teacher reflection on memorable moments, identities of self, cumulative noticings and examples of teaching practices. Co-design talanoa and the storied-conversations took place between the bookends of the initial and closing sessions. (See Appendices D1, D2 and D3 for information about sessions, co-design talanoa and storied-conversations, respectively.)

Shifts in Storied-Conversations

The positioning of storied-conversations over the course of the research reflects a notable paradigm shift, as depicted in Appendix A. In the original conceptualisation of Understand Me, semi-structured storied-conversations were the catalysts for deepening relationships and enhancing learning and teaching. As the project evolved to embrace fluid co-design, storied-conversations arose as outcomes of teachers’ noticings, or occasionally as a request by whānau.

Light years away from the initial, scheduled storied-conversations, pop-up stories (some recorded, some not) were more spontaneous, corresponding with the deepening trust across project partners. Storied-conversations were scheduled in 1 or 2 days of a teacher’s request. The recorded storied-conversations included families from a range of self-identified ethnicities and cultures (Māori–2, Samoan–1, Tongan–1, Tongan-European-Māori–1, Fijian–2 Bangladeshi–1, Pakistani–1). The wide representation of ethnic backgrounds is an indicator of the teachers’ eagerness to deepen relationships and understandings with families across cultural and linguistic differences. Invitations were often prompted by an item brought from home or something shared in class (e.g., a drawing, written story, song, or object), indicative of the teachers heightened noticing, expressed in their self-reflections. Serendipitously, the final storied-conversation of the project, captured in the photos in Figure 3, popped up in the school garden – it doesn’t get more organic than that!

Figure 3 Pop-up Storied-Conversation in the School Garden (1 December 2022)

Shift in Inclusion of Young Children

Another evolution in the design occurred as a collective innovation. A kindergarten affiliated with the school was going to engage in Understand Me in the final year. Given the ongoing concerns with Covid, we took a step back and incorporated the school’s multi-generationality. Prior storied-conversations had included siblings, cousins, aunties and grandparents – we merely amplified the call to engage younger siblings. PNS was thrilled with this way forward, as it reflected the existing whānau ethos of the school and enhanced feelings of belongingness for their soon-to-be new entrants. Of 10 documented storied-conversation sessions in 2022 and 2023, half included siblings aged 2–5 years (see Appendix D3).

The data comprise extensive documentation. Research partners developed agenda and summarised notes for all sessions (i.e., research-team meetings, beginning- and end-of-year leadership-team meetings, and co-design talanoa). Audio and video recordings of interviews, co-design talanoa and storied-conversations, and Zoom presentations by the team for the school and conferences were transcribed by a third party.

We used an innovative, continuous, collective, dialogic approach of sensemaking for our analysis. Each talanoa session with teachers and meetings with the leadership team were intentional dialogues for retrospective reflection and for mirroring tentative insights. The finale sessions each year allowed salient stories to surface and build, one on the other, across individuals. Connections were made within and across sessions, storied-conversations, classrooms and events. Shared recollections led to common insights and consolidation of meaning, particularly in preparation for collaborative presentations.

The conversations in these gatherings were critically reflective, driven by ethics of care for children, their whānau and teachers, gleaning their strengths manifested in stories from our multiple perspectives. We sustained sensemaking dialogue until we reached a consensus, enriched by dissention (Simpson, 2014). In the finale session, following an hour of robust reflection, we shared versions of the five findings with the Senior Leadership Team and the teachers and asked if the insights made sense and rang true, and whether we had missed anything. “Meaning is derived … through a compassionate web of interdependent relationships” (Simpson, 2014, p. 11). The meanings generated from this culminating session are presented next in the findings.

Findings: Mili le Afa: A Process of Collective Action and Embodied Engagement

The story of PNS started before Understand Me. This project report documents neither the beginning nor the end of their story. Understand Me is part of the collective action that PNS is doing to add strength to the relational-cultural curriculum and pedagogies the school is building with the community. We use traditional Samoan rope-making (mili le afa) as a metaphor to depict the collective action in which we have been engaged with PNS and to story the process of co-design talanoa and storied-conversations (see Figure 4).

The metaphor was chosen through co-authoring conversations with Samoan colleagues.

Everything that we do at Papatoetoe North School is connected. The mili, the afa … [Marieta demonstrates mili, the rubbing motion of the afa between the palms of her hands] … Understand Me, the storying, the conversations around home learning, it is all connected … This has not been done before. This is something that we are doing at PNS … It’s something that is here and it’s now and connected to what we’re doing. (Marieta Morgan, deputy principal, PNS school meeting, 8 March 2022)

Figure 4 PowerPoint Slide Designed by Deputy Principal and Teachers to Connect the School’s Current Value Focus on Thrive, Using Mili le Afa, with Understand Me

Mili le afa is a traditional Samoan and Pacific innovation. Afa is made from the fibrous husk which is the surrounding layer that cushions the hard shell inside the coconut. Made from niu’afa trees, afa is the strongest natural fibre in the world and the only one known to be resistant to salt water (Percival, 2012). The mili process is a unique cultural craft of melding the fibres by rubbing them between the palms of the hands and on bare thighs to produce cords. These ropes had to be strong enough to build va’a (water crafts) and fale (Samoan traditional home) that would be safe and durable.

The metaphor represents the people – children, whānau, teachers and us – inclusive of the stories of the wider community and of those who came before and those not yet born. Importantly, the mili le afa process is drawn from the natural environment, which carries meanings and knowledges that add life to and continue to live within the objects built and stories shared (Malifa, in Percival, 2012). The stories that we share, like the collective actions taken to prepare to mili le afa, are everyday occasions, not special ones. These practical, mundane acts hold meanings (SaSa, in Percival, 2012), as does the embodied engagement of storying.

To describe an indescribable process, we divide it into five strands of afa: presencing, making visible, entwining, doing and building. Each strand is briefly summarised. When afa are joined into strong ropes to lash structures that sustain and withstand climate challenges, the individual fibres are not separately identifiable. Understand Me is like that – it represents strands of the afa that PNS is joining through their relational practices that strengthen and bind their learning community.

Presencing invites teachers to slow down, observe and listen intently to learn with a child and their family in everyday interactions. The intentionality of presencing creates space and time for connections to a child’s ways of being and expressing that are openings to understanding their world. Through presencing, a teacher values a child’s subjectivities and competencies, which, in turn, contributes to their belonging and wellbeing in a collective.

All of the strands of fibre, like stories, are present in the everyday. We make subtle stories visible through our noticings. Stories are unearthed in naturally occurring embodied conversations, which extend beyond talk. Storied-conversations transform the teller and the listener and strengthen relationships with people, their histories and geographies of place.

Through the mili process of storying, relationships of children, their whānau and teachers are entwined. Their languages, knowings and objects of home are joined to and sustained in the school curriculum. As teachers reflect upon and share their insights in co-design talanoa sessions, they make these moments visible and respond to conversations initiated by children, reversing the flow of teaching and learning from child to teacher.

Mili is an active process and requires doing – working the afa – to connect. By inviting, listening and being with, we go beyond awareness, joining new fibres that bind meanings that strengthen the whole. What will we build with our collective strengths?

Home learning, the school’s inquiry approach with families, was a common theme throughout the co-design talanoa and storied-conversations. The desire to draw forth and bind knowings from home to school was a driver for ongoing work. Addressing the lack of satisfaction with attempts to reconceptualise home learning was a challenge the teachers and leadership team found invigorating. The sense that “we-are-not-yet-there” sat alongside the aspiration that we will get there.

Findings as Cords of Afa

The task is to unearth what is already there and mili (rubbing/binding) the afa strands into chords, a process that is both simple and complex. To make sense of and explain what occurred during the course of the project, we conceptualise the data as afa (see Figure 5). These cords of afa are theoretically and practically connected – impossible to pull apart. In the process of data analysis, we have illuminated separate findings as cords, and acknowledge that each cord does not exist without the others.

Figure 5 Cords of Afa

Photo: Marieta Morgan

Photo: Marieta Morgan

In the following section, we share storied-conversations to illustrate the cords of findings. Teachers and family members included in the report approved the names, pronouns, text, and images representing their contributions. Our intent was to ensure that the interpretations of children, family members, and teachers aligned with how we represented and shared their stories in the report. This step was taken in addition to compliance with ethics protocols approved by the University of Auckland Human Participants Ethics Committee (Ref: 20165). In addition, teachers and families whose images are shown in the report signed photo consent forms and consented for their stories to be reported as required by the New Zealand Council for Educational Research.

1. Storied-Conversations with People, Places and Things Were Hidden in Plain Sight

Noticing is inherent in being. We all notice. In the context of storied-conversations between teachers, the teller initiates, bringing forward their noticings. The distinctions between teller and listener are seamless and fluid. Within the constant flow of everyday conversations, teachers involved in the project began to attend differently to the noticings of children. What teachers were noticing and sharing with each other had the potential to shape what they chose to attend to in their learning and teaching with children. We all notice, but what do we notice? Hidden in plain sight, stories were nestled in silences and boisterous moments, expressed with voices and with bodies, on the playground, in the fale, at the school gate – moments saturated with multigenerational connections. What follows is one of those moments.[4]

Rose is on the brink of turning 8, which she says is going to be very different than 7. Rose’s family had recently returned from a 4-month visit to Bangladesh. They showed Judith, Rose’s teacher, a brightly coloured embroidered dress that Rose had selected and the handmade embroidered fabric that her mum was sewing for a pillow. Judith video-recorded their three-way conversation, which was a true pop-up story! A week later, an expanded storied-conversation took place, which included Rose’s younger brother (age 5), who had just started attending PNS that term. Judith and Rose’s mother had already been planning how they could bring the family’s Bangladesh culture and language into the school. Sharing precious cultural crafts opened the flow of the sharing of a wide stream of Rose’s experiences, from fishing for snapper by hand, to staying in their family home, to being with her grandmother, to going to school, cooking, celebrating Independence Day, speaking Bangla, her growing understanding of the Muslim religion and Eid and Ramadan festival and learning embroidery from her mother.

Over time, co-design talanoa facilitated a collective heightened awareness amongst the teachers of the stories emerging all around them. They became more attuned to storied-conversations. In the project finale, one teacher reflected on how one Hindi word, spoken on the playground, had opened up a space for her to understand a child’s story.

Last week, I was on duty on the playground. I think Isini has a new student in her class, an Indian girl with glasses, and she was climbing on the spider [playground equipment]. And I said, “Watch out! You might fall!” And then she just ignored me. Then I spoke in the language [Hindi]. I said, “Neeche!”, which means “come down.” Then she came down and she looked at my face like this [Dolly makes a wide-eyed expression]. And then she ran away. Then she came again and she touched me and she said, “India?” Then she was telling me her whole story, like how they came from India…what Mum is doing, what Dad is doing. (Dolly, project finale, 3 March 2023)

Dolly’s story, shared within the collective, expanded and deepened reflection beyond the story itself. A single word in a child’s language opened a pathway to her immigration story. One word can carry a story. As teachers listened to one another in co-design talanoa, opportunities for storied-conversations, hidden in plain sight, became more visible.

2. Through Co-Design Talanoa, Teachers Co-Created a Nurturing Space to Slow Down, Reflect, Share New Understandings and Interrogate Tensions in Their Work

The co-design talanoa sessions were a reflective space to collectively share openings and tensions associated with privileging everyday storied-conversations in learning and teaching. Teachers were able to better understand the push-pull between the relational and the institutional, acknowledging tensions between understanding family pedagogies and the expectation to meet system-driven outcomes. Teachers also reconnected with their own histories and stories, which prompted them to extend the same invitation to children and families. In the project finale, Marieta reflected on the power of the early morning gatherings.

The moments when we got to hui in the mornings. We did that. I just realised, who does that at a school in the mornings? Like, who turns up that early to sit there and then share at those levels? (Marieta, Deputy Principal, project finale, 3 March 2023)

During one co-design talanoa session, Jacoba shared her intergenerational weaving practice with the group. Gazing at the map of Samoa printed on the rug in the school library where we gathered (see Figure 6), Barbara was struck by the stories shared and the strong connection to her roots.

Then, the ladies would gather together in the fale Samoa, fale ia, like that, wear their lavalava, and then they will sit there and strand the whole day. And then the next day, they would start weaving and putting this all together. And you hear stories they talk about. Beautiful talanoa! And it [talanoa] is just bringing me back to my roots. (Barbara, teacher, co-design talanoa, 3 June 2022)

Figure 6 Co-Design Talanoa on the Samoan Map

Engaging in collective storying alongside the teachers also shaped how we were seen and how we saw ourselves as partners in the project. Over time, as we became more embedded in the life of the school community, our presence as researchers became ordinary and faded into the background. We were invited to understand how teachers were growing the ideas that surfaced in the co-design talanoa, and we were trusted to engage with the tensions in their work.

Engaging in collective storying alongside the teachers also shaped how we were seen and how we saw ourselves as partners in the project. Over time, as we became more embedded in the life of the school community, our presence as researchers became ordinary and faded into the background. We were invited to understand how teachers were growing the ideas that surfaced in the co-design talanoa, and we were trusted to engage with the tensions in their work.

Co-design talanoa with teachers surfaced concerns about whether a focus on stories could lead to “tangible outcomes.” Teachers who had participated in the pilot shared their aspirations to tap more meaningfully into children’s stories, highlighting the importance of academic and relational outcomes. One teacher stated: “I am interested in how to get those stories out of them, and how storying can help them with their literacy, and how their story can help with our relationships” (Brendon, co-design talanoa, 9 June 2021). Teachers new to Understand Me asked how to include children’s stories within the assessment-driven demands of teaching.

One teacher openly wondered whether the school’s name for home learning should be changed to demonstrate how much teachers valued family stories. She suggested that the school “try and integrate ‘Understand Me-home learning’, ‘home learning-Understand Me’. Just to change the ‘home learning’ into that title. Like, you say ‘Understand Me’ – the families would start to say they really want us to talk about our story” (Judith, co-design talanoa, 9 June 2021). Judith’s provocation sparked a quest at PNS for a new name for home learning that would match the intent. This moment generated new openings for teachers to consider the purpose of their existing home-learning approach and whether this pedagogical practice reflected the knowledges and experiences of children’s families and homes. One teacher explained that, as a result of the co-design talanoa of Understand Me, “right across the school, we begin to have these shifts in our minds. We are not sending home this work to tick the box” (Teacher, co-design talanoa, 9 June 2021).

Teachers critically reflected that home learning, in practice, did not necessarily reflect the relational pedagogies they aspired to enact. Embracing these tensions during co-design talanoa led to openings for reimagining how teachers might co-author curriculum with children and families in ways that prioritised relationships alongside achievement. Teachers wanted “to begin to see the expertise in the parents and to bring that into school” (Teacher, co-design talanoa, 9 June 2021). They were ready to learn from their students “because kids tell you things that you don’t know” (Teacher, co-design talanoa, 9 June 2021).

Teachers in co-design talanoa talked about how their own stories had been undervalued in school when they were children. “I was that kid who would push down my stories” (Teacher, co-design talanoa, 9 June 2021). Others observed that some children feel their stories are not worthy of sharing at school. As one said: “The kids have stories, but they don’t feel they have stories” (Teacher, co-design talanoa, 9 June 2021).

Tensions surfaced about how parents’ views of education aligned more with what the system traditionally rewards, causing them to resist valuing stories as school curriculum. “They have a different view of education, compared to what we are doing now” (Teacher, co-design talanoa, 9 June 2021). Tensions also emerged regarding how families privileged English: “They think knowing your home language doesn’t make you smart” (Teacher, co-design talanoa, 9 June 2021).

Prominent in the storied-conversations with teachers was an undercurrent of the systemic privileging of measurable outcomes. One teacher explained: “As teachers, we are always bound by ‘Oh, is it a product?’ ‘Are we producing a product and a task, and is it markable, achievable?’” (Teacher, co-design talanoa, 9 June 2021). Another teacher wondered: “So, how do you measure a story? You don’t. We still have a job and we still have goals and things we have to go towards” (Teacher, co-design talanoa, 9 June 2021). Teachers also challenged the separation of relationships and achievement: “You don’t have to separate them completely” (Teacher, co-design talanoa, 9 June 2021). One teacher emphasised that “the relationship is so key to us having those stories and those conversations with our parents, where we can gently and over time help them understand” (Teacher, co-design talanoa, 9 June 2021). Marieta acknowledged how these personal stories contributed to the “school story”:

Having these deliberate sessions and knowing that you are part of the school story, to me, has been that beautiful highlighting of the treasures that sit within us – and not to forget, because it is easy to forget in the school system. (Marieta, Deputy Principal, New Zealand Association of Research in Education conference, 15 November 2021)

In the co-design talanoa, the intersecting individual voices of the teachers joined together to strengthen the collective and the school community.

3. Storied-Conversations Invited Potentialities in Which Children, Whānau, and Teachers Understood Each Other and Themselves in New Ways

Storied-conversations led to moments in which children, parents and teachers discovered and deepened the connections between them. Openings for children, whānau and teachers to value stories different from their own expanded their learning and nurtured the wellbeing of all storying partners. Parents shared stories about themselves that children had not heard before. Teachers opened windows for parents into their children’s lives at school. Children witnessed their parents and teachers engaging in new ways. Children surprised teachers and parents and themselves with their contributions. In some moments, teacher mindsets shifted as a result of trying on perspectives different from their own.

Something in interactions between Troy (age 7), his mother and teacher opened the space for Troy to lead a storied-conversation. No warm-up or slow start. Troy was the centre of the conversation as he enthusiastically talked about his deep knowledge of Egypt, using technical terminology with confidence to name historical artefacts and people. He then made a transition and declared, “I want you to know – what I want to be is an archaeologist.” He storied that desire, without any prodding, and shared how he was so “curious about everything.” With excitement, he storied a trip he had taken to the Auckland War Memorial Museum the previous weekend to find his great grandfather’s name on the plaque in WWI Hall of Memories. This conversation ushered in Troy’s family history within the life of the school, presencing connections with Māori whānau near and far (Troy, storied-conversation, June 16, 2022).

An unanticipated impact of engaging in storied-conversations was children witnessing the strength of whānau-teacher relationships. Several parents said that they had seldom shared their views with teachers about children and family. The teachers’ recognition of the strengths of a family, in front of their children, created an entryway for parents to open up about themselves with ease. A mother from Bangladesh shared about family history and cultural views on marriage, education and parenting, prompted by the teacher’s affirming observation of an uncle’s care for her children.

He was taking care of this little one so nicely. When he was taking them back home, worried about the rain and making them wear raincoats. I was like, “Oh my goodness!” So, it is such a close bonding in the family. (Dolly, storied-conversation, August 25, 2022)

The move to online learning and teaching during the Covid-19-imposed lockdowns shifted the school’s focus even more clearly on home, as Zoom windows invited teachers to see and hear the everyday pedagogies in families. One teacher, Jill, reflected on how keen families were to respond when teachers invited them to share videos from home:

There were so many videos coming through whenever we asked for anything that said, “Oh, what do you do [at home]?” It was her and her nana, and previously what had been said [by teachers] was, “Oh, poor Nana! She has to start cooking an hour before Bianca gets home!” Or, “She has to cook for an hour with Bianca every day!” But then seeing the video of them cooking together and the joy that came from that, and just the reminder that the learning isn’t all about the math that was done while they were cooking. The learning was about coming together as a village and the power of all the people that feed into that child, and we are just a part of that. (Jill, co-design talanoa, 9 December 2021)

Moments like these highlighted the pedagogies of family and home that are embedded in storied-conversations, sparking what Marieta called the staff’s “collective earnestness” to understand what knowing a child meant for learning and teaching.

4. Home and Intergenerational Family Pedagogies Were Unearthed in Storied-Conversations, Shifting the Directional Flow of Knowledges and Challenging Social Hierarchies

The intentional reversal of the flow of knowings from school-to-home to home-to-school brought family pedagogies into clearer view for teachers. Co-design talanoa sessions carved out time for teachers to revisit their intentions to shape curriculum co-constructed with children and families, and the ease of talanoa spilled over into the classroom. Teachers began to see the ways and the extent to which the curriculum could be enhanced by storied-conversations.

In an all-school Zoom meeting to kick off 2022, teachers were invited to reflect on the first year of the project. A teacher shared her shift in mindset from hearing the family’s version of a news report about the family’s boat being stranded. The teacher described how the family’s story allowed her to resist deficit thinking,

Life was really rich, and what they wanted for their children was exactly what I want for my child and for…all our kids. So, now that I say that every time I see the mother, she wants to talk with me. The last one was a headline story about them on the boat, and the whole country would have looked at them saying…you know, “what terrible parents.” But what the mum said to me was…the Coast Guard congratulated them, and that’s what we didn’t hear. So she told me the rest of the story, how they said he [her husband] did everything right. (Marion, teacher, school Zoom meeting, 8 March 2022)

This moment altered the way Marion listened to the mother and the trust between them.

Following Marion’s reflection, other teachers chimed in about how they saw a shift in the mother’s presence at the school. Relational shifts with families spread to other teachers connected to the family.

Another teacher marvelled at children’s talanoa about Tonga in relation to the school’s inquiry theme, thrive.

The most impressive thing was when I showed them the pictures of Tonga. Even before I could say anything, the Tongan children burst out. One boy said, “Oh Miss, you know, this is Tonga, and there’s been a big flood in Tonga.” The Tongan children chipped in by saying, “My Nana is doing this and my Mum is doing that,” “We’ve been going to the church,” “We’ve been collecting food parcels.” I paused and thought these pictures had been so powerful, prompting their prior knowledge and personal voice and I had not seen this before. As a teacher, now I think: what is my next step forward with this? As a teacher, how do I interweave it into my school literacy practice? How do I use it in the classroom? [emphasis added] The overarching thing about talanoa is that it doesn’t have to be complicated. It can be done really very simple. They have moved me with these things. (Kavita, all-school Zoom meeting, 8 March 2022)

The willingness of teachers to critically reflect on their practice and to position themselves as learners in the presence of their colleagues at this Zoom meeting had impact beyond the project. The following week, these teacher quotes were featured in a professional session on culturally responsive teaching. Thus, insights from their own colleagues were used as exemplars of critical self-reflection on cultural identities and responsiveness. These reflections and the way school leaders valued them spurred several new teachers to join the project in 2022. The stories shared in the All-Staff School meeting showed the wider staff that Understand Me was not a programme or a procedure, but rather was an enactment of the school’s ethos.

5. The School Embraced Its Family-Gifted Place

PNS is a family-gifted place. The welcoming school entrance is adorned with poster-size photos of tamariki with their whānau. Fale are placed thoughtfully throughout the grounds so parents and whānau can, in Stan’s words, “come and stay awhile” (Stan Tiatia, Principal, opening hui with research partners, March 1, 2022). Being a “family-gifted place” means the families over generations have attended the school; it is their place. Concurrently, over the process of the project, the gifts the families made to PNS became more visible in the official school curriculum.

That PNS is a family-gifted place was evident in the intergenerational family histories at the school: many teachers had been PNS students and parents before they joined the staff, and other staff had children in the school. A new teacher, looking back on the year, said she had “experienced being in a school that is more like a family, which I hadn’t been in before” (Chelsea, co-design talanoa, 9 December 2021). Parents involved in storied-conversations also emphasised the importance of the school culture:

Isini [Teacher]: I feel like Papatoetoe North – like, culture is a huge thing for us, and it is something that is really quite significant here.

Mother: Exactly, because I had seen other schools – I have four sisters here [Auckland]. The kids are the same [age], and I have been to their schools, and I have seen the difference from this school to theirs, and they even come and, like we talk with each other: how was your school, did you have any function, did you have anything? Like this school, the principal, the board, they have kept everything in contact, like the culture, the island, everything. So, it feels like we are at home because other schools, they don’t normally do all this. (Storied-conversation, 25 August 2022)

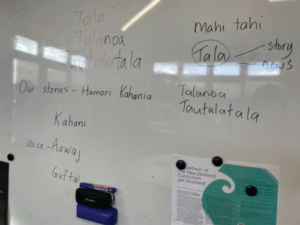

A significant moment for us was an invitation to attend a community celebration at the end of 2022. Over time, we had come to understand that the school IS the community, and that we were part of it. During the celebration, Marieta shared how the school was working to rename home learning. She was describing a list of possibilities on the whiteboard in the board room (see Figure 7).

We have been on that journey of looking at changing it, not for the sake of changing [the name], but because it needs to. I want you to have a look at the board. We have left [some], we have rubbed some off, but you can see the working of the name possibilities. Mahi tahi, we have got a Tala, Talanoa, Tautalatala, and then a Hindi name, Kahani. I just thought I would leave it up there because we are still talking about it. We still haven’t settled on what we call our new home learning, but the other thing is doing it more digitally so that the stories can come, which is what we are showing in the hall. That is why this celebration is as it is today – because of the home-learning journey. And even the way that we are celebrating – and it is not just kids who have completed 80% [of the home learning], but it is everybody. And we are celebrating everyone. (School community celebration, 1 December 2022)

Figure 7 Brainstorming New Names for Home Learning on the Whiteboard

This moment highlighted the journey the school is on to move from home learning to relationality as a measure of performance. Celebrating a “measure” (a home-learning completion rate of 80%) had shifted to celebrating families and the community. This moment, like others during the celebration, could be connected back to what we learned over time about the ethos of the school.

This moment highlighted the journey the school is on to move from home learning to relationality as a measure of performance. Celebrating a “measure” (a home-learning completion rate of 80%) had shifted to celebrating families and the community. This moment, like others during the celebration, could be connected back to what we learned over time about the ethos of the school.

The comfortable presence of young children at the celebration who would become future students at PNS was a reflection of the participation of younger siblings in the everyday life of the school community. Siblings’ stories sparked the idea of including younger children in the project before they transitioned to school.

I have just really valued having – for the first time – siblings together in a classroom. Three sets of siblings – and two of my learners have come back in the last couple of weeks– have been brand new, Year 0. They would normally cry a little bit on the first day and want to go home, but they have been so confident with their Year 2 sibling with them. And then, coming back after the weekend and having the same story together, you know, whipping up their shorts and showing the scratches on their legs from the rock pools they went to and seeing a jellyfish, and the other two going down to the skate park. The animation between them as they jointly tell their story from home. It has been quite a unique experience for us, teaching siblings. (Sarah V., co-design talanoa, 9 December 2021)

Whānau and community, strongly represented within the school gates, served as a support structure for the transition to school for young children. Thus, parents and teachers easily took up including children’s younger siblings in storied-conversations with whānau. In one storied-conversation, a mother shared the significance of the family’s devotions and the Fijian language at home and church, prompting stories from both her children.

Ethelyn, not yet 5 years old, wanted to talk about the people she calls her “church family”:

There is a girl – Leilani – at church, and it is Kevin, and Melissa, and Dukes, and Kandi and the dad.

Nancy, Ethelyn’s older sister in Year 2, shared her favourite Bible verse:

In the Bible, they mostly love, and it is called Jeremiah, Verse 3: “Call to me, and I will answer you, and I will tell you things that you did not know.”

Ethelyn chimed in:

And there is another Bible verse about “I am a hard worker.” (Storied-conversation, 5 April 2022)

In this moment, Ethelyn, only 2 weeks away from starting school, felt confident and compelled to share what she knows, and what she has learned in her years at home. Throughout the project, teachers opened themselves to the stories, lived experiences, and pedagogies of family and home, including their own.

Implications: Connecting Relationships, Curriculum and Pedagogies

In this report, we have gathered moments that teachers noticed, made visible and used to connect relationships, knowings, curriculum and pedagogies. The mili process, like the work of the teachers, is continuous and has a rhythm. Aligned with the mili le afa metaphor, the teachers’ plaiting of the five strands of presencing, making visible, entwining, doing and building will continue to yield strong and versatile rope. The rope provides structural strength for the (metaphorical) community fale PNS is building. The fale is welcoming and has no doors; it is shaped by the people who dwell there. Like the rope-making process, storied-conversations are not special occasions. The ongoing, everyday work of storied-conversations requires intentionally moving towards what you do not know in relationship with children and families.

We now share the understory that lay beneath the storied-conversations. In ecology, the understory is a thriving layer of an interconnected ecosystem between the canopy of trees and the ground cover that is essential for sustaining human and non-human life. Our project revealed three interconnected elements that served as the understory supporting the ecosystem of Understand Me and had implications for the collective: engaging in professional-learning research, embracing tensions and sustaining the unfinished, everyday work of understanding.

Collectively Engage in Professional-Learning Research

When Understand Me became part of the story of PNS, the school was on an intentionally relational, strengths-based path that centred children, families and community. The school was described often by whānau as a place where they felt welcome and belonged. As research partners, we entered the community to learn from their strengths – the ones they may not yet have seen or named in the vital life of their understory.

“You are documenting what we are doing and making it visible” (1 March 2022) was a statement made by Principal Stan Tiatia. Leadership support for Understand Me was critical to sustaining the project and for growing it in a way that aligned with the school’s aspirations. Understand Me was prioritised perhaps because it reflected the school’s ethos: this work has a place in this school at this time. The research validates their work, their stories, as treasured outcomes.

While some research conducted in school settings can be seen as intrusive, especially during a period of challenges like those presented by Covid, the teachers and leaders of PNS welcomed our presence.

I want you here in the building. You are always welcome. Even when I don’t say hello or growl, I want you in the building. You can come anytime . . . not just the scheduled times. We need Understand Me to pervade our school, to be part of us. (Stan Tiatia, Principal, opening hui with research partners, March 1, 2022)

Stan’s statement conveys a blurring of research and pedagogy that strengthened the project over time. We weren’t fixing a problem. We had no problem to fix. Our collective research was the enactment of learning and reflections on teaching within trusting relationships. Together, we were engaged in pursuing what is possible when relationships with whānau are integral to curriculum and pedagogy.

At the time of report writing, a teacher asked Marieta Morgan, co-author and Deputy Principal, “Is Understand Me PLD?” This question echoed teachers’ suggestions that we not use the label research, as it was unlike any research they knew. These comments signalled that Understand Me was an integral and inseparable afa that the school is working into their strong and versatile cords of learning. We describe this work as collective professional-learning research to reflect the way we document our learning together as teaching-research partners, with children and families. As we do the deliberate work to mili the knowings of children and whānau, the emerging curriculum and pedagogies are bonded to this school community. Traditional walls between research and teaching, teachers and researchers, home and school, have begun to fall away. The shift from scheduled to pop-up storied-conversations signalled a transition in relational turns among all partners. Project partners lived into the co-design and let the co-design live. Through storied-conversations, extended whānau, including the child, family members, teachers and researchers (Bishop et al., 2014, p. 190) have unearthed the ever-present knowledges already living in the understory, and these have become a visible part of the connected fibres of curriculum-in-the making. The collective partners are placemakers (Gruenewald, 2003) in the unfinished story of the PNS community.

Two examples illustrate the obscuring of traditional distinctions of PLD and research demonstrated by this project. Teachers initiated unprompted, thoughtful provocations in the authentic, conversational flow within co-design talanoa. A prime example was when Kavita posed the question: “What does this mean for me as a teacher?” This self-provocation opened purposeful space for potentialities in everyone’s thinking and teaching. The strength of learning came from the project partners (teachers, school leaders and researchers) building from within ourselves, as they collectively worked the provocations as afa. The work required to go deeper and build systems reflective of the vibrant life of a community’s understory takes time. This time is worthwhile. It is work that leads to contribution.

The sensemaking described in the section on methodological turns is another example of shared learning and the interpretation of experiences from multiple perspectives. The school leaders and teachers shared their insights, and these folded one on the other, spontaneously adding layers of understanding with each new story. Within this context of reciprocal trust and ethics of care, the school leaders, teachers and project personnel were collectively engaged in the research and collectively accountable for the findings. Teachers continually generated meaning (Simpson, 2014, p. 11) from their storied-conversations, shaped the direction of the project and catalysed its impact.

Collectively Embrace the Tensions

Tensions are an integral part of the understory of cultural-relational work. Storied-conversations by nature are intense. They are close-up, unscripted interactions that can deepen a teacher’s understanding of a child and their whānau. Understand Me normalised the precept that we don’t know what children and whānau know, and we are still willing to move forward.

Moving towards understanding the unknown is entwined with tensions. Working alongside each other, we explored areas that sometimes led to discomfort. Tensions arose for teachers between the seemingly conflicting expectations of taking a relational approach and of achieving tangible outcomes. Presencing children and their whānau and genuinely engaging with our distinctive identities and cultures involved doing the uncomfortable, reflective work that opens the space to understanding. Through the cumulative collective reflection that we undertook through the project, tensions from the understory were, like afa, worked (mili) to strengthen the cord of learning.

Time spent reflecting on storied-conversations in co-design talanoa created an environment in which raising tensions was a marker of contribution. The tensions drive the unfinished work. Without the tensions, the work of culturally responsive pedagogies is reduced to a procedure or rhetoric, a box to be ticked. The unresolved tensions propelled the school community and research team to continuously move towards what children and families know. Holding the tensions is work worth doing.

Collectively Sustain the Everyday Work of Understanding

The impact of Understand Me is its contribution to the ongoing PNS story, not as a separate entity but rather as a strand of afa that becomes indistinct when rubbed between the palms of the collective hands. As mili le afa is everyday work, so is valuing the stories of the people and the place to engage in the unfinished work of building the school’s official curriculum. Doing the inner work of exploring the understory strengthens the collective. When we began this project, our goal was not for Understand Me itself to be ongoing, but rather for the connections of relationships, curriculum and pedagogies made within this community to endure. Sustaining the work of noticing and understanding stories in plain sight, and binding new cords into their curriculum and pedagogy, is the collective responsibility of PNS.

Epilogue

In late August 2022, two research partners were leaving the school at the same time, after having engaged in separate storied-conversations. While briefly connecting in the car park, one looked at the other and said, “You know, this isn’t ever going to end, don’t you?” The other nodded, and said, “I’ve already been thinking about that. I’ve got an idea.” (Milestone 4 Report, 30 September 2022).

Research Team Members

Front Row (from left): Dr Meg Jacobs, Prof Janet S Gaffney, Ms Alison M-C Li

Back Row (from left): Assoc Dean-Pasifika Jacoba Matapo, Dr Tauwehe Tamati

Footnotes

- Professor Tom Roa, University of Waikato, expressed these words through a Māori worldview and in metaphorical way, recognising that our stories have been passed down (tuku iho) to us and to our perceived worlds (tatou ao e kitea ai), and that they promote wellbeing and peace. ↑

- Avikaila Sopotulagi Tilialo, Facilitator, Va’atele Education Consulting. ↑

- In addition to Janet S Gaffney and Meg Jacobs, Co-PIs of Understand Me (2022), Dr Tauwehe Tamati (Tu Puna Wananga) and Nola Harvey (Honorary Academic, Te Puna Reo Pohewa | The Marie Clay Research Centre), both at Te Kura Akoranga me Te Tauwhiro Tangata | Faculty of Education and Social Work at Waipapa Taumata Rau |The University of Auckland, were part of the original thought group and continue to advise. ↑

- Gender descriptors and pronouns are those used by the families. ↑

References

Bishop, R., Ladwig, J., & Berryman, M. (2014). The centrality of relationships for pedagogy: The whanaungatanga thesis. American Educational Research Journal, 51(1), 184–214. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831213510019

Children’s Commissioner. (2018). He manu kai matauranga: He tirohanga Māori. I. Education matters to me: Experiences of tamariki and rangatahi Māori. https://www.manamokopuna.org.nz/publications/reports/education-matters-to-me-experiences-of-tamariki-and-rangatahi-maori/

Delgado Bernal, D. (2001). Learning and living pedagogies of the home: The mestiza consciousness of Chicana students. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 14(5), 623–639. https://doi.org/10.1080/09518390110059838

Education Review Office/Tari Arotake Mauranga. (2018). Papatoetoe North School. https://ero.govt.nz/institution/1429/papatoetoe-north-school

Gaffney, J. S. (Principal Investigator). (2019–2020). Understand me: Connecting families and teachers of young children through stories–Phase Two [Grant]. Auckland Airport Community Trust.

Gaffney, J. S., & Jacobs, M. (Co-Principal Investigators). (2020). Understand me: Crafting selves and worlds in collective storied conversations with tamariki/children, whānau/families, and kaiako/teachers [Grant]. Teaching & Learning Research Initiative. New Zealand Council for Educational Research.

Gaffney, J. S., Tamati, S. T., & Jacobs, M. M. (2019). Understand Me: Storied-conversations of tamariki/children, whānau/families and kaiako/teachers. Annual Report. Auckland Airport Community Trust.https://www.aucklandairportcommunitytrust.org.nz/2019-annual-report/

Gruenewald, D. A. (2003). Foundations of place: A multidisciplinary framework for place-conscious education. American Educational Research Journal, 40(3), 619–654. https://doi.org/10.3102/00028312040003619

Jacobs, M. M., Harvey, N., & White, A. (2021). Parents and whānau as experts in their worlds: Valuing family pedagogies in early childhood. Kōtuitui: New Zealand Journal of Social Sciences Online, 16(2), 265–282. https://doi.org/10.1080/1177083x.2021.1918187

Kemmis, S., & McTaggart, R. (2014). Critical participatory action research. In D. Coghlan & M. Brydon-Miller (Eds.), The SAGE encyclopedia of action research (pp. 209–211). Sage. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446294406

Matapo, J. (2020, March 3). Understand me [Unpublished poem]. Faculty of Education and Social Work, University of Auckland.

Morgan, M., Gaffney, J. S., Jacobs, M., & Matapo, J. (with Li, A. M.-C.). (2022, October 31). A chronology of nested stories, interweaving pathways of understanding between young children, families and teachers [Video presentation]. Early Childhood Seminar Series, Faculty of Education and Social Work, University of Auckland. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CKea-jQ3RBQ&t=11s

Percival, G. S. (Director). (2012). O le aso ma le filiga, o le aso ma le mata’igatila: Exploring the use of natural fibres in Samoa [Film]. Paradigm Documentaries.

Simpson, L. B. (2014). Land as pedagogy: Nishnaabeg intelligence and rebellious transformation. Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society, 3(3), 1–25.

Skerrett, M., & Ritchie, J. (2019). Te wai a rona: The well-spring that never dries up – Whānau pedagogies and curriculum. In A. Pence & J. Harvell (Eds.), Pedagogies for diverse contexts (pp. 47–62). Taylor & Francis. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781351163927-6

Vaioleti, T. M. (2006). Talanoa methodology: A developing position on Pacific research. Waikato Journal of Education, 12(1), 21–34. https://doi.org/10.15663/wje.v12i1.296

Author Notes

This project was approved by the University of Auckland Human Participants Ethics Committee (UAHPEC20165).

Project Team at Papatoetoe North School

Children, whānau and school community including: Stan Tiatia (Principal), Marieta Morgan (Deputy Principal), Wendy Currie (Assistant Principal Y5/6), Jill Skeet (Assistant Principal Y0/1/2), Kavita Anjali (Y0/1/2), Barbara Ash-Faulalo (Y3/4 Samoan Bilingual), Dalena Cassidy (Y3/4 Te Whānau Tupuranga), Sarah Crane (ESOL), Judith Hickman (Reading Recovery), Tokahi Huri (Y5/6), Isini Kaituu (Y4), Dolly Kaur (Teacher Y0/1), Na‘i Mose (Y2), Marion Nielsen (Y5/6), Brendon Shaw (Y5/6 Te Whānau Tupuranga & CRT), Sarah Veiqaravi (Y0/1).

Author Bios

Marieta Morgan (Born in Samoa with ancestral ties to the villages of Sinamoga, Vaimoso, Vailoa, Falelatai, Mulifanua, Tafua) is Deputy Principal at Papatoetoe North School, where she leads and guides teachers in delivering a curriculum that knows the learner. Her work champions parents as the first and best teachers for their tamariki, and she believes passionately in the importance of building real relationships with parents and whānau. She is an experienced school leader who has the learner and their families at the heart of her work.

Jacoba Matapo has ancestral ties to Siumu village, Upolu Samoa and to Leiden, Holland. Jacoba is Pro-Vice Chancellor, Pacific and an associate professor from the School of Education, Faculty of Culture and Society, at Auckland University of Technology. Her research specialises in indigenous Pacific philosophy and pedagogy in Pacific early childhood education. Her work advocates for the value of indigenous knowledge systems in education and the possibilities of transformation through relational ecologies, story-telling and the art of embodied literacies.

Janet S. Gaffney (American of Irish/German descent) is a professor and director of Te Puna Reo Pohewa | The Marie Clay Research Centre in the Faculty of Education and Social Work, Waipapa Taumata Rau |The University of Auckland. Her research with tamariki/children and their whānau/families is collaboratively envisioned and designed. She strives to cherish the linguistic, cultural and social knowledges and ways of being of young children, their families and teachers, as these are the foundation of relational and respectful learning and teaching.

Meg Jacobs (American of Irish/German/Swiss descent) is a lecturer from the School of Education, Faculty of Culture and Society, Auckland University of Technology. Meg’s research privileges family contributions to understand how children’s early literacies intersect with family languages, cultural practices and histories. Meg’s work aims to amplify early literacies that are undervalued in English-dominant school-sanctioned literacy practices in order to disrupt deficit notions of children’s “readiness” for school.

Alison M.-C. Li (Born in Hong Kong and has an ancestral tie to Guangdong province of China) is a doctoral candidate in the Faculty of Education and Social Work of the University of Auckland. Her study focuses on children’s everyday storying in inclusive early learning environments in Aotearoa and Hong Kong. Her professional goal is to invite and inspire families and teachers to genuinely “read” stories of diversity with openness and respect while continually engaging in children’s playful, relational, sustainable and affective worlds of storying in conversation, play and creation.

The appendices for this online version of the report have been removed. However, you can access them here