1. Introduction

Background

Historically, kindergartens have provided early childhood environments for over three year-olds. Recent demographic changes have seen a fall in enrolments and in the numbers of children on waiting lists. The pressure to keep kindergartens on full rolls so that they can benefit from higher funding has meant that many kindergartens have enrolled a significant number of under-three year-olds in their centres. This has proven to be a challenge for teachers in terms of their teaching practices, programming and curriculum goals. Factors in the teaching environment, such as a physical environment structured primarily for the older-age child, and the large group setting of 30 to 45 children per session impact on the experiences of all the children but particularly on the very young child.

The history, philosophy and current context of the New Zealand Free Kindergarten Associations kindergartens have been shaped by the beliefs and practices of the participants in the service – teachers, trainers, management bodies, and the families whose children participate in the service. A body of literature has now built around this that also identifies the pedagogical practices which have arisen in kindergartens (Dempster, 1986; Duncan, 2001a; Dunedin Kindergarten Association, 1989; Levitt, 1979; Lockhart, 1975; May, 1997, 2001). That the majority of children attending kindergartens have largely been aged three years and over is therefore a matter of record and remains the case in kindergartens in areas whose demographics support waiting lists and high enrolments. Examples of such areas are Christchurch and most of Auckland.

There is also, however, considerable variation in New Zealand over the starting age of children at kindergarten, and in many areas there are significant numbers of two year-olds attending kindergarten. As early as 1994 teachers in South Island kindergarten associations were identifying that they had younger children (under-three years-old) starting in the afternoon session, and they discussed the impact that this had on their traditional programme:

LAURA (Interview 1994): Oh that pressure [to keep rolls full] is absolutely awful (pause). Absolutely dreadful. I mean every kindergarten teacher that I know will be doing their utmost to get their rolls full (pause). They are really trying. People are not being slack. Like I mean I’m taking children at two [years] eleven [months]. In the afternoon I am offering a care programme (pause). It’s absolute survival (pause). I tried to think of innovative ideas. I don’t know what to do (pause). We may have permanent playgroup Monday, Tuesday, Thursday1, I don’t know (pause).The age group is so wide now that I don’t want to bring any morning children back in the afternoon because their age group is too wide. It’s not family grouping. It’s nothing. It’s just yuck (pause). (Duncan, 2001b, p. 112)

A 1997 policy document in the Dunedin Kindergarten Association also discussed the necessity for under-three year-olds (Dunedin Kindergarten Association, 1997). By 2003 the age of children attending in Dunedin kindergartens had lowered further with children starting as young as on their second birthday. Additionally, the number of these very young children had increased in the sessions also. For example, in 2003, two Dunedin kindergartens had 50% of their afternoon-session children aged less than three-years, in three kindergartens, over 30% were under three, and in one kindergarten 26% of their entire enrolment was under three years. Within the full Association, of the 22 kindergartens, half had more than one-third of their afternoon session enrolments filled with underthree year-olds.

What Don’t We Know?

The changing context for kindergartens raises questions about its impact on the experiences of children and teachers. Earlier research by one of the investigators in this study (Duncan, 2001a; Duncan, Bowden, Smith, 2005), resulted in many questions about what good teaching practices and positive learning experiences for children would ‘look like’ in this new environment. For example: some teachers had been able to see this change as having many positive features, while others had been struggling with the increased physical demands of toileting children who were not yet fully toilet-trained, and with concerns about physical safety.

Academic and research literature on two year-olds in early childhood settings in New Zealand is limited; our literature search for this study made it clear that two year-olds often fall into a ‘black hole’ between being an infant and toddler (0-2 years) and being a young child or preschooler (3-5 years). This means that information pertaining to just two year-olds, or directed at working with two year-olds, is likewise very limited. It is important to question why this is so: Is it because researchers and academics have moved away from an age-related developmental discourse? Or is it because two year-olds have been subsumed into being either a toddler or a young child? Or could it be that the current New Zealand age groupings in early childhood education and care centres reinforce the invisibility of two year-olds? What does becoming a ‘kindy kid’ at two years-old now mean?

Our study has been framed with these questions in mind, mindful also that the kindergarten associations were framing similar questions when planning the future of their service (Stoke-Campbell, 2003, personal communication). [General manager of Dunedin Kindergarten Association, 2003].

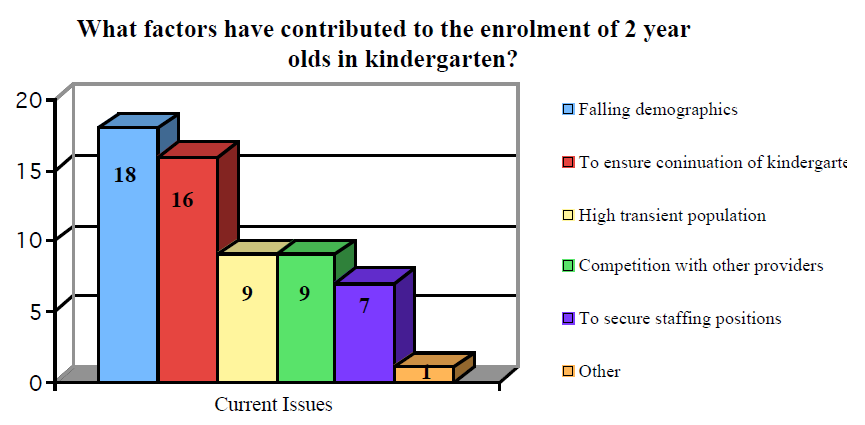

As we began the study, additional areas of interest came to our attention as conversations around the project were generated in different kindergarten gatherings in New Zealand. Our interest in the national picture of kindergarten services was increased when in March 2005, at the beginning of the second year of this project, Judith Duncan presented preliminary findings to a Kindergarten Senior Teacher Hui in Wellington. The comments and concerns raised by Senior Teachers from each of the different associations were remarkably similar to the concerns raised by teachers in this study and this suggested to us that a shared discourse might be operating within the kindergarten service around the ability of kindergartens to meet quality outcomes for their youngest children. This prompted us to design and administer a questionnaire, to canvas the associations about the wider national issues associated with having two year-olds in kindergartens. This national survey was an addition to our original project design, which focused on case study kindergartens within the Dunedin and Wellington Kindergarten Associations.

The Dunedin Context

The Dunedin Kindergarten Association governs and manages 22 kindergartens, with around 1500 children attending in the greater Dunedin area. It has a long history of kindergarten provision, as the place where the first independent kindergarten was begun in 1889. A promotional pamphlet for the association describes its philosophies as based on ‘”play as a tool to teach children the skills they need for school, and to discover that learning is fun!”. It also states that each kindergarten “has a planned curriculum that builds each child’s development over the whole year so that they are best prepared for school and beyond” (Dunedin Kindergarten Association, 2005).

The association itself had changing management over the life of this project: Between 2003-2006 there were three different General Managers, and while a new Senior Teacher position began in 2003, three changes of staffing also occurred in this position over this time. A complete new Board was appointed in 2003, and in 2004 the Education Review Office report noted:

The board is effectively governing the association. The board’s primary focus is on children and improving association operations. It is giving priority to developing a culture of improved communication and building effective relationships. It has reviewed the association’s constitution and developed a strategic vision that values partnerships, collaboration and quality. (Education Review Office, 2004)

Within this context, the consideration of two year-olds as part of the kindergarten provisions were part of the General Manager and Board discussions and so this research was seen by the Association to be timely.

The numbers of under-three year-olds in Dunedin has been quite changeable over the 2003 – 2006 period. However, Association documentation shows that there has been a considerable number of under- three year-olds for over five years within the Association. As is demonstrated in the following table, there have been fluctuations of numbers within the kindergartens, as well as within the Association, and this changes the daily contexts for each of the kindergartens.

| Name of Kindergarten | November 2003 Under 3’s |

March 2005 Under 3’s |

|---|---|---|

| Abbotsford | 7 | 0 |

| Bayfield | 7 | 13 |

| Brockville | 10 | 0 |

| Concord | 14 | 13 |

| Corstorphine | 12 | 13 |

| Grants Braes | 11 | 15 |

| Green Island | 0 | 0 |

| Halfway Bush | 0 | 2 |

| Helen Deem | 7 | 14 |

| Jonathon Rhodes | 1 | 0 |

| Kaikorai | 11 | 9 |

| Kelsey Yaralla | 13 | 16 |

| Mornington | 10 | 4 |

| Mosgiel Central | 0 | 4 |

| Port Chalmers | 2 | 2 |

| Rachael Reynolds | 15 | 17 |

| Reid Park | 20 | 4 |

| Richard Hudson | 11 | 8 |

| Roslyn | 0 | 0 |

| Rotary Park | 0 | 4 |

| St Kilda | 1 | 6 |

| Wakari | 10 | 5 |

| Totals: | 162 | 120 |

| Percentage of enrolments | 10.8% | 8% |

Comments on the Dunedin Kindergarten Association processes for including two year-olds: (Contributed by Jill Cameron in 2004- Relieving Senior Teacher 2004-2005)

Documentation:

There may have been documentation of this in individual kindergarten’s staff meeting books. There was reference to younger children attending sessions in the General Managers report to the Board of Trustees 13 March 2001:

Extra support has been placed into [name of kindergarten] for one term (one session per week for 7 weeks) to help address the issues that very young children create. The staff have initiated an extension programme in the Wednesday afternoon to give the older (10) afternoon children more opportunity for learning. This move has been well received by the kindergarten parents and we are investigating the option of this continuing to the end of the year with the funding being used to keep the extra staffing in place.

And reference to professional development:

Stuart Guyton (ECD) will run two workshops for staff in the term 1 break on programming for toddlers and young children.

Policy, Association Decision or Just Happened?

Due to the demographics and ever decreasing numbers of preschool children this has resulted in the lowering of waiting lists and younger children getting into sessions. Kindergartens’ licenses were for children aged from two years-old so the regulations allowed for this to take place. As children became younger entering the afternoon session it was a natural progression to enroll children under-three into sessions. Informal discussion took place between the association and individual kindergartens concerned.

Discussion with teachers

Kindergartens carried out brain storming ideas for providing programmes for under-threes. Challenges were discussed and ideas to overcome these shared. Teaching teams worked to find their own best practice and shared their ideas with other kindergartens. Discussion with regards to best practice has occurred informally and as part of a large group debate. Particular focus of the discussion has been group size, environment size and teacher skill base to cater for this different from traditional age group. During the initial introduction of under-threes into the kindergarten programme, care was taken by teaching teams to manage the number of younger children in the programme. Teachers were aware of the impact of having younger children in the programme and would monitor the number of younger children in a session at one time.

The Association supported professional development for teachers that focused on younger children. Course information was shared to enable teachers appropriate opportunities to become more skilled and confident in this area. For example, Stuart Guyton held a workshop on providing a programme for toddlers and young children.

Association philosophy

The [Dunedin] association philosophy is concerned with providing excellence in accessible education and care for children. With the age of children entering kindergarten becoming younger, the association has not changed its position with regards to its philosophy but has broadened its focus area in terms of ages of children. Families have supported this.

Statement from Association

There has not been a statement from the association regarding underthrees in kindergarten.

The Wellington Context

The Wellington Region Free Kindergarten Association governs and administers 56 kindergartens that cover a diverse range of communities from Levin to the eastern suburbs of Wellington. Over 4100 children attend the Association kindergartens. The Association was set up in 1905 with its first kindergarten opening in April 1906.

At the start of the project in 2004, there were four senior teachers and a Services’ Manager who, between them, provided professional advice to kindergarten teachers across the region. The senior teachers each have responsibility for a group of kindergartens and visit each of them at least once a term. In 2006, there are five senior teachers.

The Association describes itself as employing only “fully qualified and registered teachers and overall our staff turnover is low”. Its statement of values includes a commitment to “ensuring that the activities of the Association and kindergartens centre on the needs of the child as learner, and on the principles, requirements, goals and objectives stated in the Charter”.

An Education Review Office (ERO) report on the association kindergartens carried out between January to September 2005, during the second year of this study, says that the Association:

[H]as given serious consideration to the diversification of service provision to better reflect, or meet, different community needs. This has resulted in changes in session times or reorganization of groupings, in some kindergartens. However, the majority of Wellington kindergartens retain the traditional morning and afternoon sessions with tow afternoons of non-contact time each week. (Education Review Office, 2005)

Table 2 demonstrates that the total number of two-year olds in Wellington kindergartens is much lower than that in Dunedin and spread across fewer of the kindergartens in the Association. While in Dunedin 20 out of a total of 22 kindergartens (91%) had under-three year olds on their roll at the times shown in Table 1, in Wellington 25 out of 56 kindergartens (45%) were in this position, and of these only seven (28%) kindergartens had more than five two year-olds at any one time. By comparison, 75% of kindergartens in Dunedin which had two year-olds attending, had five or more during the times shown in Table 1. These differences between the two association contexts in our study illustrates the variability that exists between different associations nationally (for further discussion of this see Level Four findings of this report). A list of the starting ages of children enrolled in Wellington kindergartens tabled at a meeting with the Association in early 2005 shows that the youngest starting age across the kindergartens in September 2004 was two years eight months.

| NAME OF KINDERGARTEN | UNDER 3s 1 July 2004 | UNDER 3s 1 July 2005 |

|---|---|---|

| ADVENTURE | 0 | 0 |

| ASCOT PARK | 4 | 9 |

| BELLEVUE | 0 | 0 |

| BERHAMPORE | 0 | 0 |

| BETTY MONTFORD | 0 | 0 |

| BRIAN WEBB | 0 | 0 |

| BROOKLYN | 0 | 1 |

| CAMBRIDGE STREET | 0 | 0 |

| CAMPBELL | 0 | 0 |

| CHURTON PARK | 0 | 0 |

| CLYDE QUAY | 0 | 4 |

| DISCOVERY | 0 | 0 |

| EAST HARBOUR | 11 | 7 |

| HATAITAI | 0 | 4 |

| ISLAND BAY | 0 | 0 |

| JOHNSONVILLE | 0 | 5 |

| JOHNSONVILLE WEST | 0 | 0 |

| KATOA | 2 | 4 |

| KHANDALLAH | 0 | 0 |

| LYALL BAY | 0 | 0 |

| MARAEROA | 0 | 0 |

| MIRAMAR CENTRAL | 0 | 0 |

| MIRAMAR NORTH | 6 | 3 |

| MOIRA GALLAGHER | 0 | 0 |

| MUNGAVIN | 0 | 3 |

| NEWLANDS | 0 | 0 |

| NEWTOWN | 2 | 0 |

| NGAHINA | 2 | 4 |

| NGAIO | 0 | 0 |

| NORTHLAND | 0 | 0 |

| ONSLOW | 0 | 0 |

| OTAKI | 0 | 1 |

| PAPAKOWHAI | 0 | 1 |

| PAPARANGI | 0 | 0 |

| PARAPARAUMU | 0 | 0 |

| PAREMATA | 0 | 0 |

| PARSONS AVE | 0 | 0 |

| PETONE | 0 | 0 |

| PETONE BEACH | 0 | 1 |

| PLIMMERTON | 3 | 0 |

| PUKERUA BAY | 0 | 0 |

| RAUMATI BEACH | 4 | 2 |

| RAUMATI SOUTH | 10 | 5 |

| SEATOUN | 0 | 0 |

| STRATHMORE PARK | 2 | 1 |

| SUNSHINE | 3 | 0 |

| TAIRANGI | 0 | 0 |

| TAITOKO | 3 | 5 |

| TAWA CENTRAL | 0 | 0 |

| TITAHI BAY | 0 | 0 |

| TUI PARK | 1 | 3 |

| WADESTOWN | 0 | 0 |

| WAIKANAE | 0 | 0 |

| WAITANGIRUA | 10 | 12 |

| WELLINGTON SOUTH | 0 | 0 |

| WRIGHTS HILL | 3 | 4 |

| Totals | 65 | 84 |

| Percentage of enrolments | 1.5 % | 2% |

Under 3’s in Kindergartens Research: Wellington Kindergarten Association (Contributed by Margaret Bleasdale, Senior Teacher, June 2005)

Setting up the Research

The Association currently has approximately 18 out of 56 kindergartens with children under-three years of age enrolled in the afternoon sessions.

It has been a challenge to find kindergartens with sufficient children who would fit the age criteria for long enough to make participation in the study viable. Factors that influenced this included:

- Children starting when they were too old; for example, 2 [years] 9 [months] and older so they would turn three during the period of observations.

- Teams that were changing, for example, a new head teacher appointed, or changing hours to meet community need.

- Kindergartens that were too far away from Wellington for travel, for example, Levin.

- Current trend of families coming ‘off the street’ to enroll 4 and 3-year olds and filling up previous low rolls which had had underthrees.

Association Policy Environment

Why don’t we have more kindergartens that would fit the research criteria? This sent us on a journey of reflecting on polices in the past and how these have shaped the age composition of the rolls in kindergartens today.

The Wellington Region Free Kindergarten Association has a history of strong commitment to teacher employment conditions. An acknowledgement of the much publicised Quality Indicators led to some changes in the operation of kindergartens over the late 1980s and early 1990s:

- Group sizes lowered;

- Kindergartens were generally licensed for 45 children with three teachers. The Association reduced rolls where possible, moving to group sizes of 42 or 43. Compelling evidence indicated that even the reduction of one or two children could make a difference to the dynamic of the group, even though this decision had repercussions in other areas of Association budget.

- A limit on number of children in the session aged under-three to approximately 10% of the roll.

- At this time few kindergartens had shubs, showers or changing tables and with younger children requiring changing more frequently the high teacher:child ratios posed some concerns.

- Long waiting lists meant that some children were getting very little time at kindergarten.

- It was around this time that the Association moved from length of time on the waiting list as being the criteria for admission, to age order. This was more equitable for children and enrolment on the basis of age has continued. Admitting children by age order had the effect of lifting the average age in sessions.

- Limit on the number of shared places offered. Having children enrolled for less than the three (afternoon) or five (morning) sessions meant considerably more administration was well as meaning that teachers needed to form relationships and interact with more than the average 90 families, a load which was already considerable. Also waiting lists were longer (averaging approximately 30 per kindergarten) so the teachers could encourage parents to have their children attend for all the allocated sessions. There was also pressure on teachers to keep rolls full, the reduced group size mentioned above resulted in maximum funding being an imperative.

2. Aims and Objectives of the Research

Research Questions

Our research questions for this study were:

- What are the experiences of under-three year-olds in the kindergarten setting?

- What factors within the kindergarten environment support positive experiences for the under-three year-olds?

- What factors impact on teachers for positive environments and practices when working with the under-three year-olds in their kindergartens?

- What macro factors impact on the experiences of the under-three year-olds in the kindergarten environment?

Objectives

This project had three main objectives:

- To investigate the experiences of selected two year-olds in four case study kindergartens – two in Dunedin, and two in Wellington;

- To use data on the two year-olds’ experiences as a basis for reflecting with the case study kindergarten teachers on their planning and assessment practices with the under-three-year olds in their kindergartens;

- To facilitate cluster group meetings where the teachers from case study kindergartens lead discussions to enhance learning and teaching experiences in kindergartens that operate in an “underthree year-old context”.

Aims

The study aimed to:

- Capture the current experiences of the children at the centre from as many perspectives as possible;

- To reframe any discourse on the under-three year-olds which works to disadvantage the children or negatively impact on the teacher’s job satisfaction; and

- To work alongside the teachers to identify those discourses and structures which wider society and structures may need to address to ensure a safe, and high quality educational experience for the country’s two year-olds who attend kindergartens.

Strategic priorities

Our project has addressed the following TLRI project priorities:

Strategic value:

1. Reducing inequalities

While the phenomenon of under-three year-olds attending kindergartens is a relatively new issue for the kindergarten service, the overall decline in the traditional kindergarten enrolments indicate that this is going to be a continuing reality for the teachers and the service. We believe that families should have the CHOICE to select which early childhood centre they wish to use, and that EVERY child should have a QUALITY experience at the centre they attend. This research has supported teachers’ reflections on their practices within their programmes for two year-olds and has begun to build a community of practice that is inclusive of two year-olds within the kindergartens involved in this research. As the prompt and high response rate to our national survey of kindergarten associations shows, our study has generated much interest outside of the case study associations. We are confident that the continuing discussions around New Zealand will support improved experiences for two year-olds in kindergartens.

2. Understanding the processes of teaching and learning

This project has supported the kindergarten teachers in their day-to-day teaching practices with the under-threes in their centres. It has acted as an opportunity for teachers to engage in reflective discussions and deconstruction of their images of the very young child, and has encouraged a more inclusive approach to two year-olds in kindergartens. This has occurred both with the teachers in the case study kindergartens, and also with the teachers involved in the cluster groups who developed a sense of a community of practice throughout the duration of the study. The following feedback on the impact of the cluster group meetings from two teachers illustrates this:

It has broadened our understanding of other centres’ experiences and diversity with under-3s and their challenges.

It was interesting to learn that the issues facing under-twos are common. They can take longer to settle and learn the basic routines, for example: hand-washing, participating, eating in designated places, staying on mat at end of session. Toileting issues also.

3. Exploring future possibilities

Both in gathering the data, and discussing these with teachers, the project has facilitated developments in teacher thinking and practice with children. Our expectation was that the project would open up new possibilities not only for the case study children, but also for all children attending kindergartens. We anticipated that this would involve some deconstruction of dominant discourses about children and childhood within kindergartens. At the same time we hoped and anticipated that this deconstruction might also lead to some innovative approaches to working with children in the very early years. We feel that these expectations have begun to be met; this was demonstrated more strongly with the Dunedin teachers who were continuously involved in the project over its two-year duration. For these teachers, involvement in this project has opened up the debate about the future directions of kindergarten policy relating to very young children, including at the level of children’s experience and teachers’ own lived practice. For the Wellington teachers, continuous involvement of the case study teachers was not possible as roll and staff changes at the participating kindergarten resulted in a change of kindergarten for the second year of the project. Nonetheless, by the end of the study, it was clear that some change had occurred away from viewing two-year olds as primarily a challenge to the status quo, and as quite labour intensive, to seeing them as “actually, quite competent”. There was evidence of much reflective thinking and suggestions were shared about helpful strategies to deal with, for example, the challenges of mat time that one kindergarten was experiencing.

Research value

This study has made a significant contribution in our understanding of this under-researched and under-recognised area of education. Working alongside teachers in gathering data, and as full partners in the reflective and analytic parts of the project, this project has added to the teachers’ professional skills and research abilities. The cluster group sessions supported the dissemination of knowledge and debate outside of the immediate case study kindergartens, thus directly impacting on a wider number of kindergartens than only the case study ones. The Dunedin case study teachers took an increasing lead role in the study by presenting aspects of the research to their peers in two cluster groups, and to the New Zealand Association of Research in Education Annual Conference in December, 2005. As expressed earlier, this project directly addressed the key strategic themes of the Teaching and Learning Research Initiative and is forward looking by working in a proactive and inclusive manner.

1. Consolidating and building knowledge

In the discussions with the case study kindergartens, and in the cluster groups, the teachers engaged in reading, reflecting and rethinking of their practices drawing on current research and contemporary theory. The journey of searching and thinking about the issues for two year-olds in this unique early childhood service has generated new research questions, and new understandings of quality practices for two year-olds.

2. Identifying and addressing gaps in our knowledge

As noted earlier, research-based understanding of the experiences of under-three year-olds in a New Zealand kindergarten setting has, until now, been non-existent. This is despite significant interest in quality provision for infant and toddlers in other early childhood settings. This includes research on topics such as the relationships between children and adults in childcare (Brennan, 2005; Dalli, 1999; Rolfe, 2000), the operation of a primary caregiver (keyperson) system (Dalli, 2000; Elfer, Goldschmeid & Selleck, 2003), caring as curriculum (Rofrano, 2002) and structural elements such as appropriate staff:child ratios (Smith, 1999; Smith, Grima, Gaffney, Powell, Masse, & Barnett, 2000).

These studies point to some key structural aspects normally associated with good practice for under-three year-olds which are missing from normal kindergarten provision. For example, a primary caregiver system combined with a ratio of 1:3, allows one-to-one adult-child interaction to occur and thus the establishment of joint attention between adults and children. Smith (1999) has argued that joint attention episodes between children and adults are central to quality childcare because they allow children to become “known” by the adult who is thus more able to respond to the particular characteristics of individual children. Current discussions about children’s emotional well-being also emphasise the importance of adult-child interaction where there is engagement, “tuningin” (Greenman & Stonehouse, 1997) and a sense of “being present” to the child (Goldstein, 1998).

Our research questions and aims of this study address these very understandings and how they related specifically to two year-olds in kindergartens.

3. Building capability

This research project has been a research journey for all involved. We intended that the research would support the ongoing pedagogical documentation of the involved kindergartens and their ongoing interest and skills in meaningful research within their centres. The ongoing evaluations and discussions with all the partners in the research were used to help refine and reconsider the approaches and methods that we used throughout the two years. The employment of early childhood teachers as research assistants also contributed to building both research AND teaching practice skills and understandings for these teachers. The kindergarten teachers have expressed new understandings and insights about working with two year-olds.

4. Being forward looking

It was proposed that the teachers would be playing the key role in both the research data gathering, in the interpretation and analysis and in changing practices and discourses surrounding their work with children and families. We did not use the terms teacher-as-researcher, or actionresearch, in our proposal as currently many teachers are warned off by the sound of these titles, anticipating more work and very little positive outcomes for themselves. Instead, we had anticipated that by working collaboratively with the teachers as a research team, their involvement in this project would support their professional practice, their documentation work, as well as their emerging or beginning research skills. In conducting observations in the case study kindergartens, we employed early childhood teachers as research assistants. This shifted the role of the case study kindergarten teachers more onto the reflection, analysis and dissemination aspects of the project, rather than the actual observations and data gathering.

The cluster groups of teachers were also a key part of the project with the wider involvement of the other teachers in the geographical area. By working alongside the kindergarten associations we anticipate that there will be sustainable and ongoing professional development and policy decisions at the association level in the future. There has also been an increased national interest in the findings from this study with requests for copies of publications and invitations for presentations to kindergarten teachers around the country.

3. Research Design and Methods

Introduction

The study was initially developed between Judith Duncan and the Dunedin Kindergarten Association and Carmen Dalli and the Wellington Region Free Kindergarten Association.

Selection and Recruitment

The selection of kindergartens began by discussing the project with the Senior Teachers (ST) and Services Manager of the respective kindergarten associations. Each ST suggested likely kindergartens that both met the criteria with children, and where the staff could be interested in being part of the project. A short summary sheet was developed for the ST to take to the kindergartens suggested (See Appendix A). Once the ST had approached the kindergartens, this was then followed up with a phone call from either Judith or Carmen. This selection happened in 2003, as the application for the research grant required that we had our early childhood partners established before we could be considered for funding.

The next step was to re-establish the contact with the kindergartens in 2004 and provide them with further information and work through the full consent before proceeding with the study. However, changing rolls in the original kindergartens meant that they no longer had the children, or the available staff, to participate in the project. The process of selection and invitation was thus repeated and three different kindergartens (two in Dunedin and one in Wellington) joined the project.

In Dunedin, both kindergartens approached had significant numbers of two year-olds and were interested and able to participate in the project for the two years.

However, the Wellington part of study was impacted by a number of unexpected difficulties that required modifications to the original research design.

Rolls

Our first difficulty was to do with rolls: the number of under-threes enrolled in Wellington kindergartens and their age on enrolment.

We started the study wanting two kindergartens in different cities with a parallel profile. At the end of 2003 when we submitted our proposal, the information we had from the kindergarten associations indicated that this would be possible. However, by the start of the project in 2004, it became clear that there were marked differences between the enrolment patterns within the Dunedin Association and those of the Wellington Association (see Tables 1 and 2). While in Dunedin there was no shortage of very young under-threes enrolled in kindergartens, the total number of underthrees in the Wellington Association kindergartens was much smaller, and spread among only 45% of the total kindergartens, as opposed to 91% of the kindergartens in Dunedin.

Moreover, the under-three year olds enrolled in Wellington were closer to three than two-years of age. In Dunedin, we had numerous children who were enrolled at just two years-old.

This impacted on data gathering in Wellington in the following ways:

- There were fewer kindergartens than in Dunedin which could potentially participate in the study;

- There was a shorter span of time during which data gathering could be done before the children turned three.

When, together with the Wellington Kindergarten Association, we approached kindergartens with a history of enrolling under-threes as possible participants, we discovered they had started the year with insufficient numbers of under-threes to make a selection of case-study children; in many cases, the children on the waiting lists were over-three. Finally, for Phase One of the Wellington part of the study, we decided to start the Wellington case studies in a kindergarten with whänau grouping in a low socio-economic area. However, mid-way through this case-study, the “supply” of under-threes suddenly ran out and by August 2004, the first case study had to be terminated. A second case study had also been initiated in July 2004 and this was able to be completed as a full Phase One cycle by early 2005. This meant that only one Wellington kindergarten, rather than the desired two, was included in the study.

Staff changes

A different problem occurred with the Phase One Wellington case study at the start of Phase Two. Two of the teachers from the case study kindergarten moved to different kindergartens, leaving only one of the original teachers in the study kindergarten. The remaining teacher asked us to delay starting the Phase Two data gathering to allow the new staff to settle into the new year. However, by the time this happened, the age structure of the kindergarten had changed so that there were no longer any under-threes to participate in the study.

The combination of staff and roll changes meant that a different kindergarten had to be chosen for Phase Two of the study. A consequence of this was that it was not possible to carry-over the team experience of the case study teachers from Phase One of the study into the second phase.

Fortunately, however, one of the original two teachers in the Phase One kindergarten was able to continue participating in the study through the cluster group meetings. Additionally, the kindergarten that came on board for Phase Two was one of the two kindergartens, which had been part of the original proposal, and the teachers in the Phase Two kindergarten had been part of the cluster groups in Phase One. Nonetheless, it should be noted that the Wellington data are different from the Dunedin ones in that they cannot be used to examine whether the experience of participating in Phase One of the project made a difference to teacher practices in Phase Two for the same teachers.

The Team

Dunedin

Judith Duncan, Children’s Issues Centre, University of Otago.

Michelle Butcher Helen Montgomery, Rosalie Sherburd, Jan Taita, Bev Mackie and Penny McCormack.

Dunedin Kindergarten Association – involvement from Christine Gale (Senior Teacher), Jill Cameron (Relieving Senior Teacher), Jane Ewen (Senior Teacher), and Andrew Campbell-Stoke (General Manager).

Helen Duncan, Julie Lawrence, Karen McCutcheon, Renate Simenaur, and Jessica Tuhega (assisted with various aspects of project 20042005).

Wellington

Carmen Dalli, Institute for Early Childhood Studies, Victoria University of Wellington

Raylene Becker, Kristie Foster, Karmen Hayes, Sue Lake-Ryan, Raylene Muller and Wendy Walker

Wellington Kindergarten Association – involvement from Margaret Bleasdale, Gillian Dodson and Mandy Coulston

Chris Bowden and Kerry Cain (assisted with various aspects of project 2004-2005).

Theoretical framework

Sociocultural perspective

Sociocultural approaches to early childhood education have provided some scope for building new foundations. (Fleer, 2002)

As Fleer (2002) states above, sociocultural approaches offer “scope for building new foundations” not only for research analysis but also in constructing and conceptualising all aspects of pedagogy.

This project aimed to “build new foundations” where we wanted to increase our understanding of teaching and learning processes for two year-olds in kindergarten settings and to understand how the wider contexts of kindergarten impacts on the daily experiences of learning and teaching.

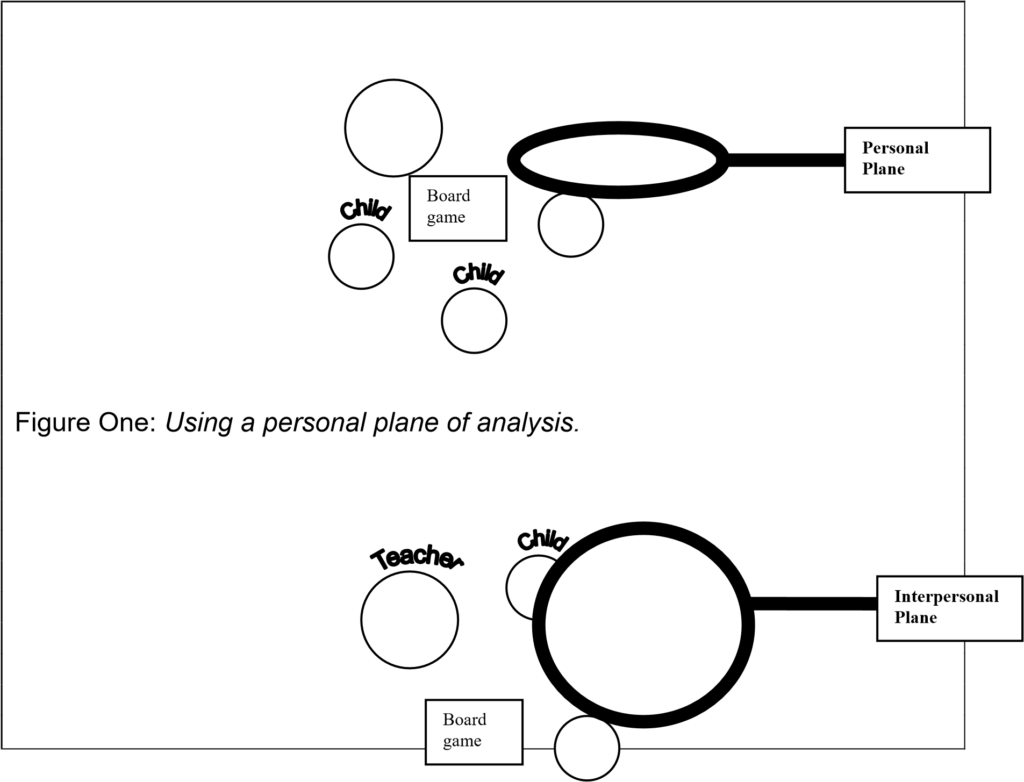

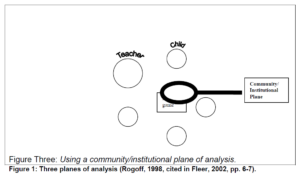

Fleer (2002) has argued that it is possible to focus our analysis of learning and teaching through three different lenses – personal perspectives, interpersonal perspectives and community/institutional perspectives – and thus be able to both observe and conceptualise our teaching in a way that encompasses all aspects of the process. To illustrate this point Fleer provides the following diagram (Figure 1), adapted from Rogoff (1998, p. 688), to demonstrate how when each perspective is combined, the child in context is more accurately captured. This approach moves away from traditional child development position which has often observed the “isolated child” (Fleer, 2002, p. 6).

Building on this multi-level perspective on teaching and learning, we shaped our study around the four levels of learning in the early childhood context, adapted from Bronfenbrenner, (1979 cited in Ministry of Education, 1996, p. 19). These are:

- Level One: The learner engaged with the learning environment;

- Level Two: The immediate learning environments and the relationships between them;

- Level Three: The adults’ environment as it influences their capacity to care and educate;

- Level Four: The nation’s beliefs and values about children and early childhood care and education.

At each of these levels we asked different questions and used a range of methods to gather data on the children’s and the adults’ experiences within the kindergarten programme. While separating out the levels runs the risk of decontextualising each context, it also offered a way of reconceptualising the teaching-learning process in education.

Developmental Discourse

This study has also taken as its starting point a reconceptualisation of the developmental discourse with which the young child is often portrayed. Recent writings by Cannella (1997), Dahlberg, Moss and Pence (1999), and Bloch and Popkowitz (2000) have critiqued our reliance on child development, developmental psychology and age-based theories. They argue that these modernist theories present children as divided into categories; lacking and in the process of ‘becoming’ (see also Woodhead & Faulkner, 2000); provide norms which are perceived as universalised and natural (work to include and exclude children); present development as linear and compartmentalised (physical, intellectual, emotional, social); and use these ideas to explain children’s behaviour and to describe appropriate and inappropriate practices and environments for children (Bredekamp, & Copple, 1997). Cannella (1997) argues that it is timely to critique these ideas; she questions these theories of development:

as a socially constructed notion, embedded within a particular historical context and emerging from a distinctive political and cultural atmosphere, and based on a specific set of values. (p. 45)

How we see a ‘two year-old’ in New Zealand, and what we feel or believe is best practice and the best environments for a two year-old, is an outcome of these ideas. Bloch and Popkowitz (2000) describe the theories and outcomes of child development and educational psychology as working to govern teachers’ and parents’ mentalities in both how they perceive children and for the consequences of the development of today’s pedagogical practices (pp. 20-25). One of the reasons that may account for the anxiety and concern at two year-olds attending kindergarten, under the kindergarten’s current structural arrangements, is the concerns about the abilities of two year-olds which informs much of our thinking about children in this age group. This raises an interesting point for reflecting on how the discourses of ‘ages and stages’ are still dominating much of the discourse of what constitutes ‘good’ or ‘bad’ practice – working as regimes of truth in early childhood education.

Exploring these notions of ‘being two’ – what this means for children, teachers and parents, has been central to this project.

Methods

The research project was divided into two phases. Phase One was undertaken over 2004 and was finished by April 2005, and Phase Two was completed by February 2006. In both phases the same methods were employed, to enable us to compare the experiences of the children between phases, and to observe any changes in practices or perceptions by the teachers over the two years. As mentioned earlier, this comparison between Phase One and Two was not possible in Wellington.

Ethics

Ethical approval for the project was applied for and received by both Victoria University of Wellington and Otago University. The complete ethics applications were also provided to both the Dunedin and Wellington kindergarten associations for their own consent and approval processes. In Dunedin the association require police clearance for all researchers in their kindergartens, and all our employed research assistants, as early childhood teachers, already fitted this criterion.

Procedures

Kindergartens

To be eligible for selection as case study kindergartens enrolments of under-three year-olds in their sessions were required to be substantial. Additionally, the teachers had to be interested and willing to be involved in reflecting on their philosophies and practices, and to take a leadership role in this issue within their association. Importantly, the kindergartens also had to be identified as already demonstrating exemplary practices with two year-olds in their programmes.

Eighteen case study children (three selected from each case study kindergarten in 2004 and another three in 2005) were selected on the basis of their age (the youngest at the kindergarten), their frequency of attendance at the kindergarten (that is, ideally a regular attendee), and their parents’ willingness for their child to be included in the study. We relied on the teachers to determine which child (and their family) would be invited to participate. Once identified, each family received an information pamphlet (see Appendix A) and were able to talk with the teachers and the researcher about their family’s participation in the study. The child was only included when we had received the parental consent.

The parents at the case study kindergartens were also given the opportunity to express their wishes for their children to NOT be included in any data gathering that was happening in the kindergarten, by indicating that they did not want photos or video recordings made of their children while they are playing. These children were then understood as NOT consenting to participate (see Appendix A).

Choice of case study kindergartens

One of the interesting consequences of starting children at kindergarten at a very young age is that it provides a very stable group of children for a maximum of three years. A slower turn-over of children means that the waiting-list cohort gets older while they wait for a place at kindergarten. This then leads to an older starting age in the subsequent cohort of children.

This phenomenon affected the start of our project at the beginning of 2004. In both Dunedin and Wellington, the two kindergartens which had been part of the original project proposal had changed situations and no longer had enough two year-olds to enable the project to begin.

New kindergartens were thus approached in both project locations: In each site, we sought one kindergarten from a low decile area and another from a middle to high decile area to provide different contexts for consideration.

Dunedin

The two kindergartens in Dunedin each had afternoon roll group sizes set at 30 children and both kindergartens had substantial two year-olds over both 2004 and 2005.

The teachers were initially approached by the Dunedin Kindergarten Association, and followed up with a call and visit from Judith Duncan with information sheets and consent forms (See Appendices B & C). Once both kindergartens had agreed to participate, the study began.

Kindergarten A (nearest school decile rating 2)

This kindergarten is situated in a low decile area in one of the older areas of Dunedin. The kindergarten has two trained teachers and uses equity funding to access 9 hours per week of additional teacher support to assist with ratios. The head teacher had taken the further initiative of applying to the Community Grant Organisation (COGS) for additional staffing to support Te Reo Mäori with the children in the kindergarten. A successful application meant that a native speaker of Mäori worked part-time in the programme with the children on a renewable annual basis. Consequently, this kindergarten has a distinctive bi-cultural strength.

Falling demographics within the Dunedin Kindergarten Association had resulted in changed hours of operation for some kindergartens (for further details see Level Four analysis). Over 2004, this meant that two teachers from other kindergartens were also present at the case study kindergarten for designated periods. These teachers supported the afternoon sessions on different days – one as a 0.1 teacher (one afternoon a week) and one as a 0.2 teacher (two afternoons a week). While the head teacher perceived these staffing positions as a help with the under-threes in the programme, none of the teachers were clear about how long these positions would be supported, nor whether there would be any consistency in who teachers filled these positions over time. As it turned out, these concerns were well-founded, as the staffing changed throughout 2004 and was removed by 2005. Interestingly, at the time that the staffing was removed, the group size of children had increased slightly from an average of 17 to an average of 20, so there was no direct correlation between the numbers of two year-olds and the additional staffing component allocated by the Association.

All the teaching staff in the kindergarten were fully trained and registered early childhood teachers.

Kindergarten B (nearest school decile rating 10)

This kindergarten is situated in a high decile suburb in Dunedin. It has two teachers and a roll group size of 30, but in 2004 the actual enrolments were considerably lower (highest enrolment of 24 over the observation period). This had changed in 2005 however, with enrolments close to 30 most days.

The teachers had established strong relationships with the families at the kindergarten. Both were trained early childhood teachers with experience within both the Kindergarten and Education and Care sectors. One teacher had a background which also included some primary teaching (and qualifications), and had spent seven years in early childhood teaching. The other teacher had a combined early childhood experience of 26 years mostly in the kindergarten sector, and a Bachelor of Education (ECE) degree in addition to her kindergarten teaching qualification. At the beginning of the study in 2004, both teachers were relieving in their positions. By mid-2005 when Phase Two of the project began, both teachers had permanent appointments. These contexts impacted on the project and will be discussed later.

Both kindergartens had preservice teachers on teaching practice postings over 2004 and 2005 while observers where in the kindergartens. This made a difference in terms of teacher: child ratio in the observations and on reflection, did not always adequately capture the interactions that would have been possible without the extra adults present. However, it did support the teachers’ to spend more time with particular children and this would be normal consequence of preservice teacher participation in the programmes.

Wellington

Kindergarten C (nearest school decide rating 3)

This kindergarten is situated in a low decile area in one of the older suburbs of Wellington. The kindergarten is situated in a multi-cultural community and at the time of the study nine different ethnic groups were represented on the roll.

The kindergarten is licensed for 43 children and has three teachers. At the time of the study staffing arrangements were changing with one teacher recently returned from leave, one teacher who was relieving and the head teacher who moved to a different kindergarten towards the end of Phase One of the project. The kindergarten did not regularly have high rolls of two-year olds but accepted two-year olds when there were no three or four-year olds on its waiting list who were ready to start. An advertisement for vacancies displayed on the kindergarten noticeboard said: “Vacancies for 3 & 4 year olds! (and sometimes 2 year olds)”. The kindergarten became part of the study because it had the required number of two-years enrolled at the time that data gathering for Phase One. It also had a similar decile profile to Kindergarten A in Dunedin. Unlike the Dunedin kindergarten, however, the three case study children were between two years eight months and two years ten months at the time that we observed them. This is typical of the starting age of two-year olds in Wellington kindergartens but very different to the starting ages of two-year olds in Dunedin

The age structure of children in this kindergarten had changed by the end of Phase One of the study, and this, combined with the change in staffing required a shift of the case study to a different kindergarten. One of the teachers continued to participate in the cluster group meetings with another attending some meetings.

Kindergarten D (nearest school decide rating 10)

This kindergarten had been involved in our original study proposal but had been unable to participate in Phase One as the data gathering period coincided with a time when there were not enough two-year olds on the roll to make participation viable. The teachers in the kindergarten had attended the cluster group meetings in Phase One and were very keen to become a case study kindergarten for Phase Two.

Kindergarten D enjoys significant community support with its activities as well as daily parental presence in sessions. The three teachers in the kindergarten are very well-established members of the community and know many of the families in the area through having had older siblings in the kindergarten. During the observation period two students from different teacher education establishments were present for a number of weeks at a time and the total number of adults present for the full afternoon sessions varied over the whole period between five to seven adults.

The kindergarten is licensed for 30 children in the afternoon and during the observation period, attendance was between 21 to 26 children. The additional parental presence during most of the mat time sessions that started each afternoon was often as high as 10 parents. The kindergarten frequently had two year-olds in its afternoon sessions and had one of the highest numbers of under-threes enrolled within the association. In common with all the other kindergartens in the Wellington region, however, these were all aged closer to three than two-years. In this respect, the profile of this kindergarten was dissimilar to that of Kindergarten B in Dunedin but similar to it in other respects.

Observing in the Kindergarten

The observers, who were not the teachers in each kindergarten, spent 4 to 5 sessions in each kindergarten familiarising themselves with the environment and building up a relationship with the staff and the children. Over this familiarisation period the researcher made notes on the design and layout of the building, and any other environmental assessments.

Observations were then carried out on selected case study children at each kindergarten.

Case Study Children

Within each case study kindergarten three children (total number 18) were selected for observation by the researcher and for discussion and documentation by the teachers.

The children were selected on the basis on age (in Dunedin two years and zero months to three months), and in Wellington, their youngest children, usually two years and eight to ten months), regularity of attendance and parental consent.

Each child was observed for a total of 4-5 sessions which were spread over 1-2 weeks. The observation times varied with the structure of the session, the events of the day and the requests of the kindergarten teachers. The methods used to gain information on the children were:

- Field notes – which took the form of a continuous narrative record of the child with as much dialogue as possible;

- Digital camera photos – focusing on interactions and other examples being captured in the field notes;

- Limited video recording (using the digital camera) – with focus on joint attention and speech interactions of the children.

Within the case study kindergartens we observed the experiences of the children in the settings, the interactions between the teachers and the children, and the children with each other. We were particularly looking for joint attention and responsive relationships. As from previous research shows, these are two of the key factors in positive outcomes for children (Rolfe, 2000, 2004; Smith, 1999). We also examined the physical environment and its layout for impact on the experiences of the underthree year-olds.

A parent of each case study child was interviewed over the same time that their child was observed (in most cases within a few days of the final observation). The focus of the interview was around the following topics:

- Initial expectations from their child’s attendance at kindergarten;

- Current perceptions of their child’s experience in discussion of the photos taken by the researcher; and

- Current expectations for now and the future. (See Appendix D)

In all cases the parent interviewed was a mother (with only one father being present for a short period of an interview) and the interviews were carried out either at the kindergarten or the child’s home. At the completion of the interview the parents were given copies of all the photos of their children (presented in a specifically constructed photo album), and some of the key observations were shared with them.

The kindergarten teachers contributed to the information on the children and their teaching practices by:

- Compiling pedagogical documentation on the case study child, with a particular focus on the research timeline;

- Keeping a reflective practice journal whereby they began to reflect on their work with the under-three’s in their session (in 2004 only);

- Participating in interviews on their perspectives on the case study child and, more importantly, on their reflections on the observations and notes made by the observers on the child and their teaching practices.

At the end of each observational period the observer and teachers engaged in a reflective interview based on the observations recorded by the observer, the notes made in the reflective journal by the teachers (2004 only), and any documentation the teachers may have recorded themselves for the child’s profile over this time. The interview prompted the teachers to explore what they knew about the child, the child’s experiences, and their plans for the child. A second interview was also held to get feedback on the combined observation notes when all the case study observations were complete. This was a reflective interview which allowed the teachers to interrogate their own interactions and practices with children (See Appendix D).

The reflective journal (see Appendix E), which had been seen as time consuming in 2004 was removed in 2005. However, later in the study, the Dunedin teachers who were involved in both phases of the project, began to see this as a key link that had helped their reflection and sense of ‘knowing’ the child in Phase One. The act of writing something each day about a particular child had assisted their feelings of ‘knowing’ the child in a way that no longer occurred without the journal. The Dunedin teachers commented:

[A]t the beginning…we were writing a diary on the child and what they’d done during that session, from our point of view, and I wonder too if that was one way that we got to know that child particularly well [Phase One]. Whereas it was not something we’ve done this time around [Phase Two]. We talked about that as being perhaps the reason why we haven’t known the child, but also that was really time consuming because every afternoon that that child was observed we had to write quite a detailed bit about what that child had done or what we had seen and yeah, then discuss it.

AND

We did get to know those three children extremely well and writing the diaries was – was, I think, really good because you reflected each day. We wrote it up at the end of that day, so we reflected on our experiences with the child that day. We were working in a quite different environment because two teachers – one’s inside, one’s outside – so our reflections were quite different in that respect of our observations of the child. And also our reflections of the day, as such, how things had gone and maybe some things that had impacted on the day. How we – just how we felt about the day.

Another teacher summed up:

And this came through quite strongly [the value of the diary] so even though these were not carried on for the second year, in hindsight, they were probably quite a valuable tool. So there’s a pointer for the next time you do research.

A final interview was held at the end of each year in 2004 and 2005 to support teachers to reflect more widely on their overall kindergarten practices and philosophies which impacted on the children in the kindergarten. These interviews proved to be an opportunity for the teachers to reflect on policies, structures, routines and personal beliefs that shaped their every day teaching and impacted on all the children – not just the case study ones.

Together these methods enabled the kindergarten teachers, along with the observers, to reflect on the experiences of the case study child, the pedagogical practices in each kindergarten, and the wider contexts of teaching and learning within each case study kindergarten.

Professional Development Cluster Groups

Alongside the case study kindergartens, cluster groups of kindergarten teachers were formed in both Dunedin and Wellington. The teachers who joined the groups were from kindergartens that had under three year-olds in their sessions. The purpose of the cluster groups was to build a shared discourse amongst the teachers about, and around, working with two year-olds. The aim was to create a community of learners and a community of practice within kindergartens for two year-olds. Judith and Carmen facilitated these groups and used the sessions to discuss the teachers’ current perceptions and to encourage critical and reflective practice. The teachers were given readings and homework assignments to support their thinking and the group discussions (See Appendix F). In Phase One two sessions were held in each area, and three were held in Phase Two. In Dunedin sixteen teachers regularly took part in all of the cluster groups (including the teachers from the case study kindergartens). In Wellington the number of teachers who attended varied between twelve and six.

The key development in Phase Two was that it was envisaged that the teachers from the case study kindergartens would take a stronger lead in the cluster groups and thus enable the community of learning to continue past the life of the project. In Dunedin, the case study teachers led two sessions – one in 2004 and one in 2005, with teachers from both kindergartens discussing their reflections on participating in the project and what this had meant for their perceptions and understandings of their two year-olds. In Wellington, this aspect of the cluster group method was adjusted due to the discontinuity in case study kindergartens between Phase One and Two. Instead, the cluster group meetings functioned throughout as a venue for exploring teacher experiences and understandings about two year-olds in kindergarten, as well as a forum for exploring macro influences on this.

At the final cluster group a small questionnaire was administered to gauge the impact and usefulness of the cluster group sessions for the participating teachers (see Appendix G). In Dunedin 10 of the 16 were returned. In Wellington, teachers chose to give oral feedback during the final cluster group meeting and two kindergartens supplemented this with written feedback.

Kindergarten Association Survey

By mid-2004 we had became increasingly aware that the national picture of two-year olds in kindergarten was largely unknown. Conversations between Carmen and a number of North Island associations revealed that the reality of kindergartens in different associations was likely very variable. This was confirmed when early in 2005 Judith spoke at a senior teacher hui in Wellington where strong interest was expressed in the initial insights from Phase One of our study. In response to this awareness, we developed a survey, with assistance from Julie Lawrence (Postdoctoral Fellow at the Children’s Issues Centre). The survey was designed to capture a sense of the national situation of two year-olds in kindergartens: we were interested in the number of kindergartens with two year-olds and in identifying the issues or challenges that kindergartens were facing. The results of the survey have enabled us provide a wider context for our findings. The survey findings are also valuable as a stand-alone resource about the current context of two yearolds in New Zealand kindergartens. We had intended that the associations would be followed with phone interviews with Senior Teachers but due to the timing of the return of the individual surveys (late in 2005), this additional step did not occur.

Design of the Questionnaire

The survey questionnaire was designed as a postal, self-completion survey and it was estimated to take approximately 10 minutes to complete. It consisted of 19 questions and was a combination of demographics, selection of key factors for each association, and opportunities for respondents to add additional comments.

Pilot of questionnaire

The questionnaire was piloted with two associations, and small changes were made to clarify the questions before they were mailed out to the other associations (see Appendix H).

Survey methods

In October, 2005 the survey was sent to 32 kindergarten associations throughout New Zealand, addressed to the General Manager of each association. In December a reminder (by letter and phone) was sent to those associations who had not returned their questionnaires and by the end of January we had a total of 29 returned (91%).

Analysis

The computer package SNAP was used to both construct and analyse the data. (See Appendix I for full report of survey data).

4. How the project contributed to building capability and capacity

Capability and capacity building within the project team

The capability and capacity building in this project occurred at many different levels and times across the project. We built this project around the kindergarten teachers (in the case study kindergartens and cluster groups) and other early childhood teachers for our other research tasks. All researchers within the kindergartens were early childhood trained professionals. The support for the cluster groups in the form of note taking was undertaken by a preservice early childhood student (Dunedin), and a research colleague who has considerable experience in early childhood research (Wellington). The literature review was also undertaken by a trained early childhood teacher. The survey of associations was administered by a postdoctoral fellow with the Children’s Issues Centre, who has considerable work and research experience in the early childhood sector from a health and social work perspective. The combined skills of this research team has added to the depth and validity of this project and also has added to the research skills of the teachers, who are emerging researchers and early childhood teachers.

Those involved share their experiences of this study:

The Kindergarten Teachers

Michelle, Penny, Rosalie, Jan and Helen

(transcribed and edited from presentation at the New Zealand Association for Education Conference, December, 2005)

Michelle:

I’m going to start with becoming involved in the project. It was an interesting beginning. We first received a fax from the senior teacher at the kindergarten association asking us how many children under-three we had in our programme. Little did we know when we replied that Judith had a cunning plan and we very honestly replied and soon Judith arrived armed with many consent forms for us to sign. And as a part of that she talked to us about what the research might look like in terms of observations of children and what we would expect as teachers in being part of the project.

As a part of that, she did say at one stage that she would be reporting any bad practice that she saw, both professionally and personally, to the kindergarten association and that absolutely terrified us. My mind boggled – I just wondered what this bad practice was going to look like. And I kind of thought well: we’re a two-teacher kindergarten and perhaps when Penny was outside with a group of children and I was on inside, maybe it would be something that would happen when I was perhaps changing the child in the bathroom, or something. And I couldn’t quite figure what it was going to be, but it was all a little bit scary. We did sign those consent forms.

Penny:

The next part was the building relationships. We were a wee bit scared of Judith at this stage, and perhaps what she was going to find.

And she’d stated too that she wanted to be quite anonymous and not interact with the children because she wanted to observe. So the children found that quite hard because they’re used to having those reciprocal relationships where people keep talking to them and Judith didn’t want to. And often we would get a ‘pointing over’ at a child from Judith to indicate that she wanted us to come and deal with the child so – so it was very interesting. So we had lots of finger-pointing that a child needed attention. But, however, after a few sessions Judith became part of the kindergarten environment and the children reacted very quickly to knowing that there was no use going to Judith because she generally didn’t help them so. Well, she didn’t actually talk very much, because she was always busy writing. She did a lot of writing.

So after a while we even started looking forward to Judith coming and she then started to bring her own lunch and we would have wonderful conversations and discussions over lunch, which was really great so we looked forward to that too.

So the next part: being part of the project. Being part of this project has allowed us to build up really strong relationships with the children that were being observed because we did a very comprehensive diary, a daily diary. Mainly about the day and how it had gone and then particularly about the – the child and the interactions that we’d had during that time with that child. So every afternoon we had to sit down, write up a couple of paragraphs about the day and then the information that we had about that child. So we became very familiar, very quickly with these children and remembering that these children were two-years – and sometimes one day – that they started at our kindergarten. They virtually started on their birthdays. So they were very young. So we were pretty focussed on these children. We really got to know them and realised that these two year-olds were very capable and very confident. It was our first experience with working with two year-olds, AND a large number of two year-olds. So each day that we were being observed we felt quite stressed because our actions and our words were being recorded, especially if we were near that child.

Michelle:

I also had, what Judith calls the ‘researcher effect’ on relationships, while the children were being observed. In the second phase of the research I began to examine my motives for interacting with children and I would ask myself: Am I going to interact with this child now because Judith’s here and I haven’t had an interaction with this child yet today? Or am I going to interact with this child because I see the need for it, at this point in time, with what they’re doing? I’d also examine how many interactions perhaps I’d had with the children of the group, as such, because we had a larger number of children in our afternoon session at that time and I really wanted to have some equity for the children that she was observing at the time. So that became quite difficult for me to determine. When I should and shouldn’t interact with the children? Whether I was doing it purely because Judith was there, or whether it was authentic? And the more I queried it, the harder it became for me to determine whether it was authentic or not.

As Penny was saying before we found that the children underthree were really capable, competent children and we certainly learnt a lot during the project and the following interactions.

Rosalie:

Let me just start with this little introduction, which is how we felt as a team, being part of the research, the good, the bad and the ugly. There wasn’t too much of the ugly. Some of it was, not good – the percentage of two year-olds in our kindergarten are half to two-thirds two year-olds. And this has been the case for several years now, probably since the introduction of bulk funding where there was great pressure on us to keep our roles at the maximum number. So the day they turn two, the day they start. And most of our children do start in the afternoon session, at two. So that’s a lot of little poppets around the place. So we certainly met the requirements for the research.

We’ve had two researchers with us, we had Helen Duncan in 2004, and Jessica Tuhega in 2005. Both of these people were trained early childhood teachers, and had worked in kindergartens and early childhood centres. So very aware of the type of situation they were coming in to. They were very competent, very easy to work with. We did have a lot of laughs and it was very easy for us to forget they were there and just carry on managing the session. They were very nonthreatening. With that number of two year-olds you don’t have time to think too much about other people – adults – they can look after themselves.

We found that probably one of the things that was a bit more difficult was the interviews. In the first year, in 2004, the interviews were at the end of each child’s observations and these were at the end of a double-session day, initially. And they went for about an hour and trying to get our brains concentrating for that length of time was very, very difficult. We were very tired. So the second year we changed it to a noncontact afternoon after lunch and we were a bit more on task at that stage too.

Our involvement: reflecting what Penny and Michelle said, it was probably a lot more work than we actually initially thought. Judith sort of eased us in very gently there – the workload did increase quite dramatically from the first impression. The reflective journals were an extra task at the end of the day. But they were great for all of us, the adults there, to be able to compare what had happened with these children during the session, how they matched with the person observing, who was just doing total observations of that child the whole session. And we did find that, even though we may not have had a great number of interactions with that child, we were certainly aware of what they had been doing and where they had been during the afternoon. And this came through quite strongly so even though these were not carried on for the second year, in hindsight, they were probably quite a valuable tool. So there’s a pointer for the next time you do research, with somebody else – hint, hint.

The observation drafts, which were books on each child that we read – they certainly affected our practice. We were looking at each child through the eyes of an observer who had just been totally focussed on that child. And there were things that we thought we knew about that child but sometimes we didn’t, we weren’t aware of. So that certainly was very valuable for us. A lot of these children had no language, being just two, it was somewhere between a baby talk and forming proper words. They sort of had a wee language almost of their own and they were very non-verbal cute. But what we felt was quite amazing was that they understood each other. We didn’t understand what they were saying, quite often, but they actually understood each other very well. And they would say: this our ga aye aye. And they’d nod and off they’d go. They certainly managed to make themselves understood.

We have learnt a tremendous amount about the two year- olds in our sessions. We did, well, we thought we knew quite a lot about them, but it’s opened our eyes a bit to what was actually happening for these children. I think that the statement: ‘it’s not about knowledge for knowledge sake’ but using theory, and knowledge for change and bring about change at a practical level, summed it up for us. And that’s what I think, is where we’re heading next, is the practical level.

The research: how does that impact on our present situation? We hope it’s going to have some very positive outcomes for two-year olds in the future that it is going to go through to the powers that be and they’re going to take some notice of what has happened.

Jan: We had time to reflect with the journals and also in our clusters and in our little meetings on the Wednesday afternoon. And through that we’ve had to make some changes in the kindergarten.

WELLINGTON KINDERGARTEN TEACHERS commenting on their participation in the research: transcribed from exit interview

Teacher 1: I think it has been quite a thing to draw us together in some ways. We’ve kind of recognised each other’s value as a team. You read through the observations and we’re doing the very best that we can given the resources that we’ve got and the time constraints and everything else, all the factors. We really do want to do our best for the children, but it doesn’t mean that we don’t get frustrated, or that we don’t find times that we could say “Oh, I could have done that better”. We all have times like that and wish that we could be there in a slightly different way for the children.

Teacher 2: We acknowledge and we don’t beat each other up over these things because we know we’re all learning and we’re all on that journey.

Researcher: When you say these observations and our discussions have made you see and value the others, is it because..?

Teacher 1: We don’t see each other…

Researcher: So you see each other in the notes now.

Teacher 1: Yeah, you sort of act in isolation otherwise. We don’t really know….

Researcher: So these notes have been helpful.

Teacher 3: Yes. Because you don’t know what the other teacher has been saying to the children, you don’t know what’s going on. You have a cross-over and you have a few minutes and you’re aware that you’ve left outside unattended so you quickly say what you’ve been doing…We’re all at different places so it’s not like we’re interacting with each. So this has been good.