1. Aims, objectives and research questions

Drawing from both kaupapa Māori and Western perspectives, this study has focused on global issues of ecological sustainability in a variety of local/national early childhood education contexts. It has aimed to contribute to an emerging body of research which illuminates, documents and integrates possibilities for early childhood education pedagogies that reflect and enact an ethic of care, both from kaupapa Māori (Ka’ai, Moorfield, Reilly, & Mosley, 2004; Mead, 2003; Ritchie, 1992) and Western theoretical perspectives (Braidotti, 2002; Dahlberg & Moss, 2005; Foucault, 1997; Gilligan, 1982; Goldstein, 1998; Noddings, 1994, 1995). We considered this emphasis on ecological sustainability as a teaching and learning issue (Gruenewald, 2003), philosophically grounded in an ethic of care with a particular focus on respect for Papatūānuku, to be incredibly timely in light of discussions on climate change and globalisation (Bosselmann, 1995; Mies, 1999; Plumwood, 1993; Shiva, 1997; Smith, 2001).

For Māori, a sense of ecological responsibility is sourced in a conscious awareness of Papatūānuku (Haywood & Wheen, 2004; Kereama-Royal & Ashton, 2000; Marsden, 2003; Te Puna o te Matauranga, 2003). This realisation that our destiny is intimately/ultimately bound up with the destiny of the earth reflects a holistic and respectful view of life (Marsden, 2003). For this study, tikanga Māori has reinforced our imperative, in positioning us and our co-researcher educators as kaitiaki of our environment:

It is the task of all things of creation, particularly human beings, to seek te ao marama, enlightenment and fulfilment [sic]. Nature is forever in the state of te kore, te po, and seeking te ao marama … it suggests a cycle and rhythm of life. And one in which the past, the present and the future are forever interacting. (Henare, 1998, p. 3)

This research focus on ecology and sustainability in the context of early childhood education was instigated by a teacher, Marina Bachmann, of Collectively Kids Childcare and Education Centre, who felt passionate about the possibility of developing a project that investigates how to “take action” against global warming and climate change with children, families and teachers (see Section 3.3). In a first conversation with the teacher it quickly became evident that we shared the desire to research how teaching and learning with young children can evolve around the notion of ethics of care for self, others and the environment as constructive action towards ecological sustainability. In consultation with other co-researchers, it became clear that we also shared common understandings across both Māori and Western constructions of the ethics of care. Throughout our work on this project we were privileged by the support of kaumātua and kuia for whom this sentiment of regard for our unity and totality with the environment and universe is intrinsic. This is expressed, for instance, by the Waikato people’s emphasis on kaitiakitanga of the river. Tainui kaituhi Carmen Kirkwood states:

It is not our mana that makes the river great. It has its own mana. People get mixed up about that. What it should be about, today, is the wellbeing of that taonga. And that’s for all people. We should be addressing our environment right now as a total people. We should be looking at what we can do together, what we can learn from one another, right now, to restore the river. (cited in Kereama-Royal & Ashton, 2000, p. 35)

Our collective (practitioners and academic co-researchers) interest in this project arose from our awareness that learners and teachers urgently need to have access to knowledges and practices that enable understandings of the increasingly complex ethical relationships between self, others and the environment. Initial research on the topic of ecological/sustainable practices in early childhood education, both nationally and internationally, generated few results (Flogaitis, Daskolia, & Agelidou, 2005; Flogaitis, Daskolia, & Liarakou, 2005; Russo, 2001). This has changed over the course of the research project. There is clear evidence of an emerging focus on ecological issues in early childhood education (Pramling-Samuelsson & Kaga, 2008), and the literature is beginning to point out how important research in this area is (Davies, Engdahl, Otieno, Pramling-Samuelsson, Siraj-Blatchford, & Vallabh, 2009) which positions this project in a “cutting edge” category.

The study was planned and developed in close collaboration with a range of teachers who work in very diverse communities. These teachers hold a wide range of expectations of themselves as educators, of aspirations for children and pedagogies that enact global/local community values and knowledges. At the outset of the study, some of these teachers had expressed their sense of feeling overwhelmed by what they had perceived to be the need for drastic change in the light of environmental degradation, and their sense of a lack of support to begin the process. It is not surprising that these teachers articulated a sense of disempowerment. The Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment, Dr J. Morgan Williams, puts the task these teachers are facing into the wider New Zealand context:

Our dominant value systems are at the very heart of unsustainable practices. Making progress towards better ways of living therefore needs to be a deeply social, cultural, philosophical and political process—not simply a technical or economic one. Technical and economic mechanisms will certainly be key parts of the process. However, they will not come into play unless we, as a society, are prepared to openly and honestly debate the ways that our desired qualities of life can be met. That is why there must be a vastly expanded focus on education for sustainability. (Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment (PCE), 2004, p. 5)

Critical and postmodern perspectives are increasingly being applied to pedagogical thinking, validating and honouring our human vulnerability and situationality within the ecosystem, resulting in reconceptualisation of previously unquestioned assumptions reliant on positivistic technological fixes for environmental plundering (Gruenewald, 2003; Simon & Smith, 2001). Pedagogies of place have been the subject of recent theorising (Edwards & Usher, 2000; Gruenewald, 2003; Knapp, 2005). These theorisings reprioritise our interconnected and interdependent relationship as local and global citizens of the earth; they suggest that we integrate these understandings in our educational praxis, grounding them in respect for our localised positionalities, focusing on how we live in order to ensure that our places/planet are/is respected and preserved by current inhabitants for future generations (see Section 3.3 in this report). It is interesting that these recent conceptualisations are exploring territory congruent with longstanding and enduring indigenous philosophies that are imbued with attitudes of respect and care for the environment (Haig-Brown & Dannenmann, 2002; Hill & Stairs, 2002; Patterson, 2000). (See Section 3.2 in this report.)

The need to foster diversity and multiple perspectives is also strongly emphasised in research that discusses concepts of ecology in the context of social and cultural discourses (Bryld & Lykke, 2000). By working across a range of different sites that all have an interest in engaging their local communities, we have been able to gather evidence for practices that work in very diverse communities (inner-city, rural, kaupapa Māori, North and South Island, kindergarten and childcare). (See Section 3.4 in this report.)

Our overall intention for this project, inspired by a conversation with teachers, was to build a culture of ecological sustainability practices in early childhood education. This rationale also involved expanding the focus of an ethic of care that has already been strongly articulated by some teachers in the context of kaupapa Māori perspectives’ pedagogies (Ritchie & Rau, 2006, 2008). Recent research in early childhood education in Aotearoa has documented ways in which teachers have moved from “teaching about” tikanga Māori, to enacting and modelling Māori values such as manaakitanga within everyday routines and pedagogies (Ritchie & Rau, 2006, 2008). Whakapapa and manaakitanga are core organising frameworks within tikanga Māori (Ka’ai et al., 2004; Mead, 2003).

We were particularly excited by the opportunity of researching the possibilities of bicultural pedagogies based on ecology (broadly theorised in this context as an ethic of care for self, others and Papatūānuku). Te Whāriki (Ministry of Education, 1996), the New Zealand early childhood curriculum, creates a powerful base from which to develop ecological pedagogies. It draws on the notion of four interconnected dimensions (the physical/tinana; the mental/hinengaro; the spiritual/wairua; and the emotional/whatumanawa) to produce the idea of the child as a holistic learner. These dimensions are further embedded through the four principles (empowerment/whakamana; holistic development/kotahitanga; family and community/whānau tangata; relationships/ngā hononga). In many ways, ecology was already part of New Zealand’s early childhood education discourse (see Section 3.1 in this report)—the question then became about how “ecology” is put into practice(s), and whether these existing practices support sustainability. These are the four broad areas framing this study:

- What philosophies and policies guide teachers/whānau in their efforts to integrate issues of ecological sustainability into their current practices?

- How are Māori ecological principles informing and enhancing a kaupapa of ecological sustainability, as articulated by teachers, tamariki and whānau?

- In what ways do teachers/whānau articulate and/or work with pedagogies that emphasise the interrelationships between an ethic of care for self, others and the environment in local contexts?

- How do/can centres work with their local community in the process of producing ecologically sustainable practices?

These overarching aims were unpacked in the following way:

1. To focus on policies and practices that address the need for change towards more ecologically sustainable practices in early childhood centres. Each centre will already have practices and policies in place that can either be developed or modified.

The objectives of this aim were to:

- examine current practices and policies

- identify areas for developing existing practices and policies.

Questions that guided the research under this aim were:

- What aspects of current policies and practices can be defined as “ecologically sustainable”?

- Based on current practices, how can learning and teaching become more focused on ecological sustainability?

2. To consider ways in which Māori ecological principles can inform and enhance a kaupapa of ecological sustainability, as articulated by teachers, tamariki and whānau.

The objectives of this aim were to:

- identify those principles and practices reflective of Te Ao Māori conceptualisations

- build and strengthen knowledge and understandings around this kaupapa

- further develop and/or modify existing practices and policies.

Questions that guided the research under this aim were:

- What understandings do we have of Māori ecological principles?

- Based on what is currently understood, how can these kaupapa Māori conceptualisations inform our learning and teaching in order to enhance a focus on sustainability?

3. To understand how teachers articulate and work with a pedagogy of place that emphasises the interrelationships between an ethic of care for self, others and the environment. Within this project, the use of the term “pedagogies of place” refers to the understanding that practices do not exist in isolation; they arise according to available knowledges and discourses in specific locations.

The objectives of this aim were to:

- examine the discursive relations between practices, knowledges and pedagogies

- begin the process of critically illuminating, documenting and integrating diverse knowledges to generate “pedagogies of place”.

Questions that guided the research under this aim were:

- What are the existing relationships between self, others and the environment in each centre?

- What does it mean to practise “an ethic of care for self, others and the environment” in the centre context?

- How can ethics be strengthened and articulated in ways that promote ecological sustainability in the context of pedagogies of place?

- How do wider social and cultural discourses inform teachers’, tamariki and whānau understandings of a pedagogy of ecological sustainability?

4. To investigate how centres work with the local community in the process of producing sustainable practices, based on an ethic of care for the self, others and the environment.

The objectives of this aim were to:

- co-explore with teachers how their sustainable practices relate to those valued and practised in their local community

- articulate how these practices, discourses and/or resources are responsive to an ethic of care for self, others and the environment.

Questions that guided the research under this aim were:

- How do existing pedagogies relate to practices, discourses and/or resources that exist within the local community?

- In what ways are links to the local community strengthened and/or developed?

- How do ethics held within each centre relate to the local context?

2. Overview and discussion about the research design/methodologies employed

Collaborative discussions and hui were arranged to ensure that the teacher co-researchers were involved in the final research design, and were able to tailor data collection instruments and processes to their own contexts and preferences. The theoretical paradigms for this study drew upon qualitative research methodologies (Kincheloe, 1991) such as kaupapa Māori (Bishop & Glynn, 1999; Mead, 1996; Smith, 1999); critical indigenous (Denzin, Lincoln, & Smith, 2008) and ethnographic modes that offer exploratory, naturalistic, holistic, multimodal and interpretative approaches to the study of people and communities (Aubrey, David, Godfrey, & Thompson, 2000; Barnhardt, 1994; Schensul, 1985). Processes for data theorising included dialogical negotiation of meaning (Siraj-Blatchford & Siraj-Blatchford, 1997) and collaborative storying (Bishop, 1996, 1997). Also central to the research process were ongoing reflexive supportive relationships between each participating centre and the academic researcher(s) who worked closely alongside the teacher co-researchers and tamariki/whānau of that centre. Our intention was to build a research community of practice, the foundations of which are trusting and respectful relationships that allow for challenge and critique (Wright & Ryder, 2006).

Ethical considerations and a range of data gathering strategies were explored with teacher coresearchers at a preliminary hui. Each centre had an academic researcher working closely alongside the educators to support the research process and utilise data-gathering strategies that the participants considered appropriate for their particular contexts. Different centres have utilised photographs, audiotaped and videotaped co-theorising interviews, documentation of tamariki and whānau narratives. A strength of the study has been the co-theorising hui where teacher coresearchers shared both their data and their methodological strategies with the teams from other centres. This co-theorising model demonstrates the increased researcher capacity that is consistent with one of the Teaching and Learning Research Initiative (TLRI) strategic goals. Teaching teams who had participated in previous studies that had utilised similar methodologies (Ritchie & Rau, 2006, 2008), demonstrated leadership in sharing their research skills with teams who were new to research at the preliminary collective hui for methodological discussion. Some centres preferred their assigned academic researcher to utilise an ethnographic approach, whereby they collaborated alongside the researcher who took primary responsibility for data collection by spending time participating alongside the educators, tamariki and whānau in that centre’s daily activities. Data gathering also included documentary analysis (Fitzgerald, 2007) of centre policies pertaining to manaakitanga and sustainability. Interviews were transcribed and, along with other written data, were analysed utilising a qualitative software analysis program.

3. Research findings

This findings section is framed around the four research areas:

3.1. Philosophies for sustainability:

What philosophies and policies guide teachers/whānau in their efforts to integrate issues of ecological sustainability into their current practices? (Janita Craw lead writer)

3.2 Te Ao Māori:

How are Māori ecological principles informing and enhancing a kaupapa of ecological sustainability, as articulated by teachers, tamariki and whānau? (Cheryl Rau lead writer)

3.3 Pedagogies of place:

In what ways do teachers/whānau articulate and/or work with pedagogies that emphasise the interrelationships between an ethic of care for self, others and the environment in local contexts? (Iris Duhn lead writer)

3.4 Communities of ecological endeavour:

How do/can centres work with their local community in the process of producing ecologically sustainable practices? (Jenny Ritchie lead writer)

Glossary of early childhood centre abbreviations

In this report, each centre has been allocated an abbreviated reference as follows:

Bellmont Kindergarten Te Kupenga, Hamilton [BM]

Collectively Kids Childcare and Education Centre, Auckland [CK]

Galbraith Kindergarten, Ngāruawāhia [GB]

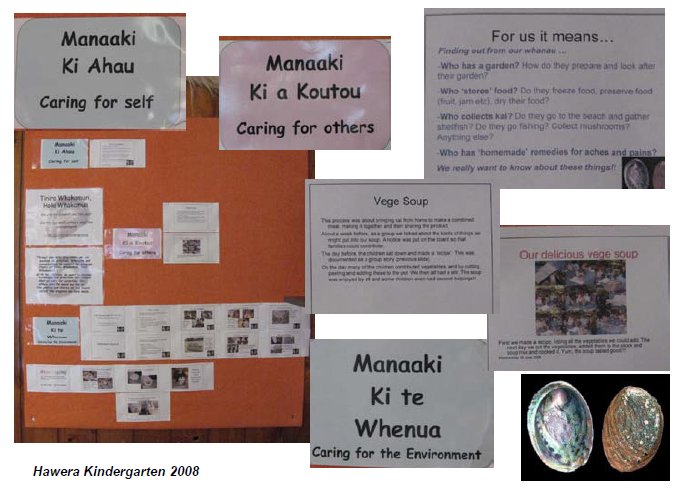

Hawera Kindergarten, Hawera [HW]

Koromiko Kindergarten, Hawera [KM]

Maungatapu Kindergarten, Tauranga [MT]

Meadowbank Kindergarten, Auckland [MB]

Raglan Childcare and Education Centre, Raglan [RC]

Papamoa Kindergarten, Tauranga [PM]

Richard Hudson Kindergarten, Dunedin [RH]

3.1 Developing philosophies and policies that guide ecological sustainability practices in early childhood education

Introduction

Trees cause more pollution than automobiles do … (Ronald Reagan, 1981)

Environmental scientists have since confirmed Reagan was partially right—although we are the real villains every time we, for example, hop in a car or leave lights on when we’ve left the room, for all the good they do in the world, trees do produce atmospheric ozone: “in hot weather, trees release volatile organic hydrocarbons including terpenes and isoprenes—two molecules linked to photochemical smog. In very hot weather, the production of these begins to accelerate …” (Radford, 2004). This example emphasises the complexity of developing a knowledge and understanding of ecological sustainable issues such as climate warming. Implementing an ethic of care that involves caring about ecologically sustainable issues that affect “our world”, our “life and the way we live it”, such as climate warming or local/global peace are (or should be) of concern to us all within early childhood education (Lenz Taguchi, 2010; Pramling-Samuelsson & Kaga, 2008; Selby, 2008). Perhaps an inspiring example of the active commitment that is not unique in, or to, early childhood education is ex Aotearoa New Zealand kindergarten teacher and tireless inter/national campaigner for peace and nonviolence, Alyn Ware—Alyn was recently awarded a Right Livelihood Award in recognition “for … effective and creative advocacy and initiatives over two decades to further peace education and to rid the world of nuclear weapons” (The Right Livelihood Award, 2009). This report reveals the kind of active commitment (and advocacy) that a number of early childhood teachers/teaching teams across the country are considering as part of their endeavour to make a difference in the/ir worlds; teachers and communities are paying attention, in one way or another, to what becoming ethical and responsible means in a world committed to ecological sustainability.

This component of the report will indicate how the teachers (re)considered their philosophy, their policies and practices they identified as being essential to supporting “a culture of caring for education for ecological sustainability”, in the broadest sense, in early childhood education settings. It will indicate the teachers’ different responses revealed in the research data to the first key question that would guide their self-review and action planning processes that would enable them to develop a direction for ecologically sustainable practices particular to their community and context. The question asked: What philosophies and policies guide teachers and whānau in their efforts to integrate issues of ecological sustainability into their current practices? The main objective of this question was to encourage the teachers to (re)examine their current philosophy, policies and practices and identify the need (or the desire) for transformative change towards becoming more ecologically sustainable in their philosophies, their policies and as a result in their practices in early childhood settings.

3.1.1 Becoming philosophical and/or theoretical about ecological sustainability in early childhood education

… Sustainability is the capacity to endure. In ecology the word describes how biological systems remain diverse and productive over time. For humans it is the potential for longterm maintenance of wellbeing, which in turn depends on the wellbeing of the natural world and the responsible use of natural resources.

(Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 2010b)

When the teachers were brought together in an initial collective hui at the outset of the research they shared their different understandings of the research project and exchanged ideas about how they might ascertain their centre’s specific direction/s in response to the aims/objectives of the research. It was evident from the beginning that some centres, particularly, but not exclusively, those actively engaged in Enviroschools projects—and/or those who had already been involved in previous research projects that focused on developing principles and practices of whakawhanaungatanga in their centres (Ritchie & Rau, 2006, 2008)—had already embarked on a journey towards developing a philosophical/theoretical knowledge and understanding of the potential to develop ecologically sustainable practices in early childhood education. Hence, it was anticipated that the centres would already have philosophy statements, policies and practices in place that would, in one way or another—through processes of critical self-review—support the teachers/teaching teams to ascertain what education for sustainability would look like in their particular setting (Pramling-Samuelsson & Kaga, 2008). Further, these self-review processes would enable them to modify or develop current policies and strategic plans to ensure that the learning and teaching practices in their particular contexts could become more deeply focused on ecological sustainability—as teachers indicated:

… we looked at our philosophy and also reflected on how central and vital Papatūānuku is to ecological sustainability … our collective vision compares children to trees—with attentive gardeners (teachers and parents/other adults) to tend and nurture them … [RH]

… caring for the self, others and the environment are fundamental to the centre philosophy, policies and projects, drive the centre programme and define our relationships beyond the centre … sustaining the quality of the programme requires ongoing input from all members of the centre community … [CK]

… by being part of the environmental issues in our community highlights for children the connection between the community and kindergarten. Families/whānau are empowered to make a difference and care for the environment locally … [PM]

… we are in sustainability and the things that (have) happened in our environment have a long history … [GB]

… recycling has been a part of our kindergarten for some time now but we decided to revisit the process as we have not talked about it for a while … [KM]

… everything I’ve heard, read, seen and experienced leaves me with no doubt that the impact of global warming is the biggest challenge our children will face. And it’s one that has already had devastating effects on many children in the world … children and the environment are vulnerable … [CK]

3.1.2 Drivers for critical engagement—a catylyst for change in early childhood education

A number of different desires acted as drivers that motivated different teachers and teaching teams to be involved in the research project. For a number of individual teachers and/or teaching teams, the journey towards enacting the principles and practices towards an ecologically sustainable curriculum was relatively new. One teacher identified herself when she began the research as an “eco-skeptic”—she suggested:

… being a part of a team that is committed to the ecological sustainability approach has been a huge step for me, but having us all take it on board has helped to make these changes worthwhile … we’re all at different levels on the continuum and we’re all progressing at our own pace … [CK]

Some teachers had entered into the research project because there was a member or several members/whole teams whose drive and commitment were in response to a strong desire to enact the potential for developing deeper philosophical understandings, policies and practices in all early childhood settings. They had a vision that early childhood settings could be places/spaces where environmental and ecologically sustainable ways of living were centred within the everyday practices. From this perspective, “education for sustainability” work is inseparable from a participation in the everyday cultural/other politics that abound in the community—as Giroux (2000) suggests, pedagogy “in this discourse is about linking the construction of knowledge to issues of ethics, politics and power” (p. 25). He suggests: it is in the realm of everyday culture that “identities are forged, citizenship rights are enacted, and possibilities are developed for translating acts of interpretation into forms of intervention” (p. 25). Teachers were interested in developing a knowledge and understanding of how their own and others’ agency unfolds in the everyday teaching and learning practices that occur in the early childhood setting that support “education for sustainability” in relation to the children, parents/whānau and the community. A few examples suggest:

… it’s one of the … ecological principles that we’ve become more aware of on our journey and manaakitanga: caring for people and our environment. As a team we acknowledge the shift in our practice and our philosophy. We’ve reflected on our values and our beliefs and how this shift in thinking is now evident in the kindergarten environment … Our planning, evaluation, self-review processes always are within the context of education for sustainability … we’ve realised that things take time and we will continue to review, discuss and implement new plans with both a bicultural and environment influence. It is about taking small steps and learning with children and families; empowering people with many different skills and ideas to come on the journey with us. [PM]

… an area that really interests me is developing critical and engaged citizenship in children and strengthening the advocacy role of the centre … [CK]

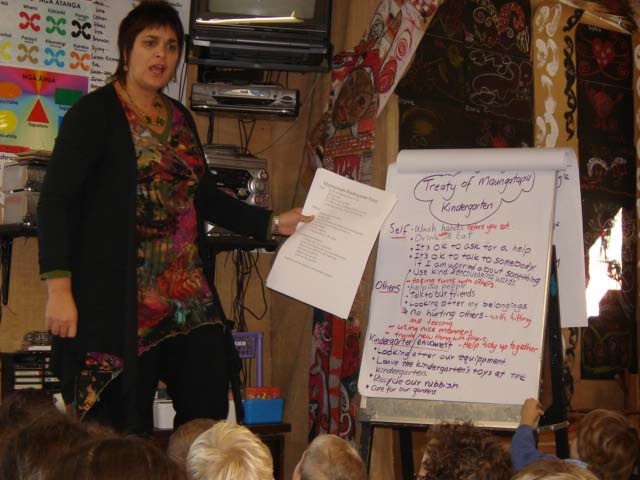

It was evident that the research meant different things to different teachers/teaching teams in the project. Although some teachers were at the early stages of developing a philosophical knowledge and understanding of how they might engage with ecological sustainability, for others, the philosophical commitment to ecological sustainability revealed itself at a much deeper level. The documentation gathered as an essential component of the research data emphasises the importance placed on Te Whāriki (Ministry of Education, 1996) as a major support document for teachers. However, they articulated a number of other influences that determined how they were developing their understandings and ecologically sustainable practices in early childhood settings. Several made visible the idea that the Treaty of Waitangi underpinned their approach. For some teachers, a deep commitment to “Māori” involved developing a knowledge and understanding of tikanga Māori and its relationships with the earth, the universe. For these teachers, it was about embedding this knowledge into the very fabric, the principles and practices, of life and the way of living in the early childhood setting—they articulated how this commitment framed their research journey:

… The research is about Māori ecological principles, how they’re informing and enhancing a kaupapa of ecological sustainability … the Māori worldview is holistic and cyclic, one in which every person is linked to every living thing and to the atua, which is the Gods. Māori customary concepts are interconnected through our whakapapa, which is your genealogy that links to te taha wairua, which is your spiritual element, and te taha kikokiko, which is your intellect or your body and your whole spirit. [PM]

For other teachers, the catalyst for critical engagement that happened as a result of designing and developing the physical environment for teaching teams was on occasion the catalyst for changed practices that initiated or enabled teachers to develop a deeper commitment to their ecologically sustainable research journey:

… while planning our new outdoor environment we visited several other kindergartens to gain some ideas about how we wanted to move forward with our environment. One of the kindergartens … was involved in Enviroschools and we became interested in the areas of their environment set up with ecologically sustainable systems … [MB]

… Developing new premises has allowed us to begin to address ecological sustainability in a more serious and effective manner … [CK]

For one team, the catalyst for changed practices and a deeper commitment happened as a result of changes within the teaching team:

… what happens for a change of team, teams have to look inwardly and talk about what they believe, what they value, talk about their philosophy and recreate a common understanding, and this was at a time when this particular team started to really recognise that they had common interests around sustainability. [Tauranga Kindergarten Association Senior Teacher]

Yet this was also perceived as a threat—or perhaps a catalyst for further challenges that included defining their understandings of sustainability with “a respect and a connectedness with the past, the present and the future”—the teachers’ reflections indicated:

… can it be embedded in the kindergarten, in the kindergarten philosophy, in terms of should the team change. Teams will change. Is it something that has to come with the people in the team?

… sustainability today is drawing on the past … when the team changes … things get lost, things that have been built up but … that accumulated knowledge … I’m sort of loving that idea of these accumulated stories so that even if the team does change, I mean how do we build sustainable practices so that they don’t disappear completely because we know they can …

… we’ve seen the whakatauki as past, present, future and the change of teams and I just wanted to say … each person here represents a team, and then the team represents a community and it goes back and back … like in the ocean that goes right back … I don’t know how many people we would actually affect in a day. [KM]

On several occasions teachers noted it was a particular “event” that created conditions for further productive thought—and new actions. Lenz Taguchi suggests, “through everything we do we add something to the world” (2010, p. 52); one event is connected to another. Some teachers’ motivation to pursue the what for, why and how would they manage or engage in everyday ecological sustainable practices with the children happened as a result of an excursion or a parting gift:

… But it was the worm farm that first started it off, wasn’t it. A trip to the worm farm … it was all new I think the recycling story … how it started … Papatūānuku. The recycling … [RC]

… we got underway … when we received a worm farm … a leaving present from one of our families … [MB]

Another teacher made connections with her own personal experiences as a way in to developing her knowledge and understanding of what ecological sustainability might mean in the here and now—and perhaps, the future:

… (the) lifestyle because I first was there in the 70s and you know I just loved gardening and just being in nature with children and just doing it. [Penny, RN]

Although the centres often differed in the things that motivated their interest and in their approaches to ecologically sustainable policies and practices, they all endeavoured to weave their developing knowledge and understandings into their fabric of life and way of living early childhood education in ways that made sense in their particular context. They were interested in establishing the kind of culture that enabled ways of being and becoming ecologically sustainable to occur “naturally” in the daily practices (Lenz Taguchi, 2010; Slattery, 2006). The principles of practices inherent in this approach are as essential to managing some of the challenges as they are to making a personal/professional commitment to being actively engaged in ethically determined ecologically sustainable practices; as teachers indicated:

… sustainable practice, it’s what we do, all the time. [RC]

… being sustainable is a way of life. It has to be really ingrained in the programme or else it won’t work. For example, there is a high turnover of children and whānau at kindergarten. We are constantly starting from the beginning again … [MB]

… sustainability is meeting the needs of current generations without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs … and that’s been the basis of what we’ve gone on with from there … it’s now written into our philosophy, it’s written into our strategic plan … [KM]

Creating and developing a shared professional knowledge and personal/team/centre/community philosophy that accepted an active engagement with local/global ecologically sustainable policies and everyday practices was central to this endeavour. Identifying the “need” (or the “desire”) for change towards more ecologically sustainable practices was inevitably determined by the teachers’ professional knowledge and understandings of what ecological sustainability might be. This, together with their image of what it meant to be a child in their particular early childhood context, determined how they interpreted and understood the possibilities for ecologically sustainable practice within an early childhood setting. One team used a “gardening” metaphor to articulate their philosophy:

… we believe that children are like young and tender plants and that we teachers, parents, whānau and caregivers are the loving and caring gardeners who nurture them, water them, and support them so that they can grow into mighty and fruitful trees. ‘Na te moa i takahi te rātā.’ The rātā which was trodden on by a moa when young will never grow straight, so early influences cannot be altered. [RH]

Slattery (2006) suggests that policies that promote “holistic and ecological models of curriculum dissolve the artificial boundaries between the outside community and the (centre)” (p. 216). He emphasises the importance of “teaching that celebrates the interconnectedness of knowledge, learning experiences, international communities, the natural world, and life itself” (p. 216). This can be interpreted to indicate a dissolving of the artificial boundaries that prevent children, teachers and parents/whānau and the community working—and learning—collaboratively in the shared endeavour that ecological sustainability demands. Hence, for many of the teaching teams, redeveloping a policy or vision statement at the beginning of the research project that reinforced a shared commitment to ecological sustainability acted as a “guiding light” and encouraged them to “orchestrate holistic learning experiences thoughtfully and carefully” (Slattery, 2006, p. 216) in collaboration with the children, with parents/whānau and/or with other people/experts in the community.

However, the teaching teams and the teachers within them often understood what this meant for early childhood education in different ways; another team articulated in their philosophy:

… children are our present and the future … we aim to provide children with a curriculum that will enable them to make the most of diverse challenges in the present and the future … [CK]

The teachers indicated in the rationale they wrote for being involved in the research that they were intent on developing (and enacting) a deeper knowledge and understanding of ecological sustainability—and of the ecological systems theory promoted in Te Whāriki (Ministry of Education, 1996):

… Global warming is beginning to impact on children’s lives and will shape their future. Within the framework of our philosophy, doing our best as teachers means addressing this issue within the centre, as well as moving beyond our immediate environment to education, involvement in community projects, advocacy and lobbying. [CK, 2007]

3.1.3 Te Whāriki and other curriculum initiatives as frameworks for ecological sustainabiity in early childhood education

Philosophies and policies in early childhood education are driven by a combination of personal/professional beliefs about values about a range of things about (early childhood) education—about teaching and learning, as well as how we know and understand the world and what it means to be human (or nonhuman) living life on planet Earth—from a range of different perspectives. These are informed by particular carefully selected theoretical understandings that enable teachers to enact their personal/professional beliefs and values in ways that benefit children’s learning. Fundamental to Te Whāriki’s (Ministry of Education, 1996) philosophy and framework is an ecological approach derived from Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory (Cullen, 2004, p. 70). Cullen suggests this approach to curriculum implementation confronts teachers with philosophical and practical dilemmas as they endeavour to reconstruct their professional knowledge in ways that enable them to work effectively within it. She explains this approach as “family focused, emphasising partnership with families, authentic assessment and learning in natural settings” (Cullen, 2004, pp. 70–71). However, this research challenged the teachers to go further than this—it expected them to engage in a process of collective inquiry that involved making changes to their philosophies, their policies and practices in ways that emphasised the centrality of ecological sustainability within a holistic sociocultural curriculum. An ecological approach was described by one team in their philosophy statement:

… where children are influenced by values and beliefs of his or her family and society/community in which they live. [MB]

The teachers revised their philosophy and vision statements to reinforce principles that valued ecological sustainability practices. They believed that a knowledge and understanding of different worldviews were important for all children, their parents and whānau—particularly in relation to Māori as the indigenous peoples of Aotearoa. They stated:

… we endeavour to honour te Tiriti o Waitangi in spirit and in practice. We are completely committed to our bicultural journey. [RH]

… our vision … is for teachers, children, and family/whānau to learn and maintain an ecologically sustainable environment at kindergarten that will incorporate Māori ecological principles. [MB]

… we aim to involve (our)selves, children and families in community and global environmental issues to advocate for more environmentally friendly practices (for example, transition towns network, ties with Oxfam). [CK]

Although the philosophical/theoretical framework Te Whāriki (Ministry of Education, 1996) provides is highly valued by many in early childhood education, it has often been criticised for the lack of explicit expectation or direction that it offers early childhood teachers in relation to specific subject/content knowledge and practices. However, the Ministry of Education has a generic website, Education for Sustainability (http://efs.tki.org.nz/), that provides guidelines for all who work in education. It sends a strong message:

… Sustainability is a critical issue for New Zealand—environmentally, economically, culturally, politically, and socially. We need to learn how to live smarter to reduce our impact on the environment so that our natural resources will be around for future generations. (2010)

Such policy documents can be understood as “vehicles and instruments” of particular discourses that prescribe what is important if not essential in an early childhood environment (Moss & Petrie, 2002). These documents “paint a picture” of the desirable practices that determine what is best or wise for children and their learning. Although the research did not set out specifically to ascertain how these documents might guide and support teachers (or whether they do) with worthwhile ecologically sustainable practices, it is evident that the teachers relied heavily on principles and ecological systems theory that underpin Te Whāriki (Ministry of Education, 1996) as a basis for connecting their knowledge, their ideas and aspirations to implement practices in response to the ecological sustainability issues that abound in the community.

The research anticipated that any changes the teachers would make to their philosophy and policies would recognise that “education for sustainability” would offer children “learning experiences and interactions in rich environments in which nature has a central place (and) that builds (children’s) capabilities as active, engaged young citizens” (Davis, 2009, p. 228). However, for many of the teachers involved, the learning was as much about seeing themselves and parents/whānau as learners, as ethical and responsible citizens, learning—through a “green” lens, with/alongside children—as it was about the benefits to children’s learning per se. This “community of learners approach” is often transparent in their philosophical statements, in their policies and in the discourses they use to explain their practices. Although the centres involved in the research differed in the type of centre they were (childcare/kindergarten, public/private), the kind of community (urban/rural) they inhabited, there was an expectation that the teachers would incorporate and make visible how they would, in their specific environment, integrate different and diverse knowledge/s into their philosophies and policies, and consequently into their practices. In particular, that they would consider how they valued Māori ecological principles and practices and how these might be (re)enacted with and alongside other perspectives. As one team indicated:

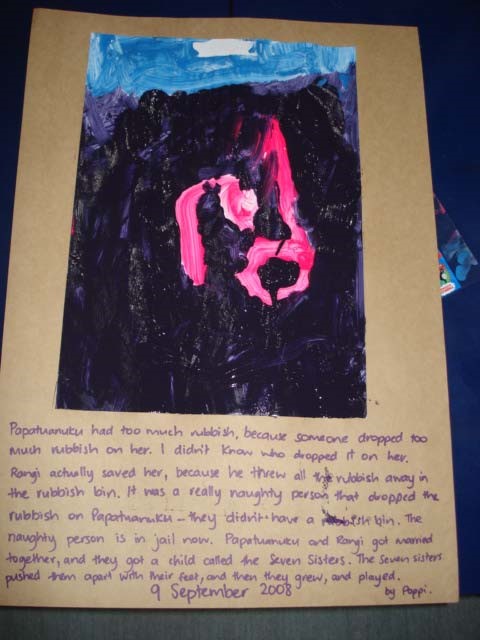

… We thought it’s really important to us to share the stories and the legends of our local place … even the other stories and legends like Papatūānuku and Ranganui. It’s important to pass on the local legends and knowledge of the land and each place has a significance because of its locality, and it creates an ownership and pride of place for everyone … a sense of tūrangawaewae, a place to belong, within the kindergarten community and not working in isolation but also working with the community. The community has a lot to offer and that’s [the] value, being part of it … This story is about the orca whales who were stranded on [the] beach last year and that was a big thing for our community … [PM]

However, for many teachers, it was the “normalised” practices and processes of writing “philosophy statements” and of “self-review” that enabled them to ascertain the implications of “the big picture” stuff (for example, the community, climate change) and bring their values to the fore or identify their lifestyle aspirations and the learning opportunities these concerns offered in their everyday practices. These processes and practices strengthened the teaching team’s commitment and supported the teachers to develop shared visions together with action plans that identified the things the team valued in relation to ecological sustainability that would support them to implement practices identified as relevant to children, parents, whānau and the community.

In another instance, the teachers articulated connections between what they were doing in relation to ecological sustainability practices with the National Heart Foundation of New Zealand’s initiative that acknowledges early childhood education’s commitment to self-care health practices.

Teachers consistently identified “links” with Te Whāriki (Ministry of Education, 1996). In particular they used the “learning outcomes” to explain the things that children did and the learning that might have occurred; in particular, children’s developing relationships with people, places and things (for example, celebrating Matariki as part of their annual practices or their daily recycling and reusing paper practices). Te Whāriki’s (Ministry of Education, 1996) specific learning outcomes contributed to teachers’ ways of explaining how they enabled children “to contribute positively to the environment”. This also involved teachers writing vision statements and/or policy and developing their philosophy statements in response to making “connections with family and community” as part of their strategy for addressing “environmental issues”. In several instances, this highlighted how they worked with the community “within the programme”. For one centre, the local community had established a recycling centre that became an important place of motivation for the teachers and children. For other centres, the (added) inspiration came from their neighbourly “Enviroschools”—several centres had award-winning Enviroschools next door whilst some were already “Envirokindergartens”. This often had the effect of enabling the school and the early childhood centre (often a kindergarten rather than a childcare setting) to build reciprocal, if not collaborative, working relationships. As one teacher articulated:

… our local school hosted the Rā Whakangāhau last year and we were invited to participate … [we have] a really close relationship with our school, they’re our neighbour … they’re right on our doorstep … for us it was that acknowledgement about being part of the community … being engaged … that was incredibly valuable for us … it was reciprocal, it was wonderful … [PM]

Understanding the early childhood centre as being part of the community and having a dynamic engagement with that community involve developing a complex understanding of the possibilities and the potential for developing sociocultural curriculum. Dalli (2008, p. 173) notes the ten-year strategic plan (Ministry of Education, 2002) for early childhood education describes early childhood education as “a multi-disciplinary field that draws on knowledge/s from diverse areas”, an approach consistent with Te Whāriki. Understanding Te Whāriki as “a weaving (Whāriki) of experiences that are not subject-bound but arise when … teachers are able to draw knowledgeably on insights from others with whom they might develop collaborative relationships” (Dalli, 2008, p. 173) with teachers/parents/whānau and others beyond the centre is evident in this TLRI research. As Dalli (2008) reinforces, teachers understand their professional role as including “being part of the community, making links with schools … and making use of valuable community resources”, a role that actively supports “the life of the community” (p. 182). This being part of the community and making links with schools is also about making connections between the learning that is valued within and across these different contexts—and in society generally.

3.1.4 Resourcing—developing ecological sustainability know-how

Knowledge has the power to produce and change action. Having what is referred to as a “content” or “subject-specific” knowledge, that is, knowing something about something, being informed or having a depth of subject knowledge/s has been identified by several early childhood researchers and writers as being essential to enabling teachers to “provide children with a curriculum” that enhances teaching and learning in early childhood education (see, for example, Cullen & Hedges, 2005). Learning and teaching ecologically sustainable practices is no different; developing a knowledge about, for example, global warming and/or Māori ecological principles and practices enabled teachers to identify policies and relevant practices in response. For some teaching teams, developing an in-depth knowledge was focused explicitly on building their knowledge and understanding of tikanga Māori ecological principles and practices.

The teachers sought to resource their professional knowledge and practices in a number of ways that included a range of “extracurricular” activities:

- attending workshops: Yoga, Edible Foods or Sustainability as a Team

- consulting and collaborating with the kaumātua or other representatives of the local iwi

- working collaboratively with more expert others in the community; for example, working with parents/whānau who were expert compost makers

- developing working relationships with neighbouring Enviroschools

- participating in whole-team/Kindergarten Association relationship-building days that involved “beach clean-up” experiences

- contacting other eco-friendly groups in the local neighbourhood.

Consulting with others was, for some, an integral part of puzzling over the meanings of concepts in ways that would enable them to develop more depth—as they indicated:

… Papatūānuku is another real strength [in our] philosophy. That at the moment is in draft and we’re discussing it because what does the wider concept of Papatūānuku [mean]; we could say Mother Earth but there’s a wider concept to it and we need to work with all whānau and with our local iwi about what does that mean to them. [GB]

… the families that are in our community that are going the extra step, with no-dig gardens, and being self-sustainable and environmentally sustainable … that has become deeper to me, and means a lot … [CK]

However, how teachers in early childhood education “politicise” their approach to curriculum philosophy and theory (that is, how they take into account—and they did—the nature and evolution of, for example, capitalism’s consumer and exploitative culture (Reynolds, 2004)) is too often left up to particular teachers/teaching teams. This involves going beyond a “technicist approach” to both policy and practices (Moss, 2007). As Moss (2007) emphasises:

“democratic participation (and in the context of this research, it is import to add here, a less consumerist and exploitative democratic participation) is an important criterion of citizenship; it is a means by which children and adults can participate with others in shaping decisions affecting themselves, groups of which they are members of and the wider society”. (p. 7)

From this perspective (“green” as in an ecologically responsive), citizenship can be understood as a matter of developing community spirit as well as about being a responsible or “wise” consumer (for example, encouraging and aiding parents/whānau to buy eco-friendly goods (Fair Trade coffee or light bulbs)) and other sustainable practices (for example, saving power for the good of the environment) as well as for personal benefit (reduced family/whānau electricity bills). As one teacher stated:

… there is no question that to live sustainably we have to reduce consumption—how do you do this with kids who are bombarded with messages to consume, who regularly confuse need and want … [CK]

Moss and Petrie (2002) suggest that children’s “spaces”—they use “spaces” as a deliberate strategy to avoid the neoliberal language of “services”—can be (or often are) “products” of public policy; that is, they are institutions, often “with narrow policy agendas (e.g., learning goals, readiness for school, childcare)” that result in a narrow curriculum focus with narrow learning opportunities for children (p. 110). It is evident from this research that many early childhood teachers are endeavouring to offer more than this, to be innovative in the way that they interpret curriculum, the way they interpret Te Whāriki (Ministry of Education, 1996), and in the philosophies and theories they draw on to ensure that opportunities for dynamic, value-ladened learning and teaching happen—for children, parents/whānau and teachers. The teachers in this research are endeavouring to be the kinds of teachers who are able to (re)enact new kinds of education for sustainability that, as Pramling-Samuelsson and Kaga (2008) predict, “… can help prevent further degradation of our planet, and that foster caring and responsible citizens genuinely concerned with and capable of contributing to a just and peaceful world” (p. 9). A teacher indicated:

… we have high expectations of the children, even our very young ones, to care for our resources, tidy, take responsibility and this is an area that I would really like to continue working at, looking at alternative pleasures, like the joys of receiving and using an item with a history attached to it; giving home-made presents … [CK]

3.1.5 Identifying principles important to teachers engaging with education for ecological sustainability in early childhood education

Although the centres developed focuses specific to their early childhood setting and local community, there were a number of recurring themes evident across much of the research data that stood out as being of importance or significance in regards to developing philosophies and policies pertinent to education for sustainability—in practice. These are:

- establishing an “ethic of care”

- connecting with nature

- “reducing, reusing and recycling” resources.

3.1.5.1 Establishing an “ethic of care”

Often, different members of different teaching teams had different understandings of what it meant to “care” for the environment (self and other). For some, “caring” meant children “sharing” with each other or caring for nature (growing vegetables, taking care of animals). Others who were aware of the “big picture” stuff sought meaningful ways of making sense of how an early childhood setting could be (pro)actively engaged in “making a difference” to the way we care for either our human selves and others or our other-than-human animals, places and things.

Moss and Petrie (2002) use the term “care” to refer to “an ethic, applicable to all practices and relationships within a children’s space … (to) foreground responsibility, competence, integrity, and responsiveness to the Other” (p. 115). In the context of “caring for ecological sustainability”, the Other is interpreted as all other humans (people) or other-than-human—animals, places (the local/global environment)—as well as all nonliving things in the world. Moss and Petrie quote Readings (1997) to suggest, “children’s spaces have the possibility of being a ‘loci of ethical practices’” (p. 155, cited in Moss & Petrie, 2002, p. 115) that foster an ethic of care of all living/nonliving things, places and spaces. Moss and Petrie (2002) suggest this approach implies a “consciousness that relationships and practices that arise from being a collective setting are not just technical” (p. 115). From this perspective, the traditional practices of, for example, caring for animals, growing plants in an early childhood setting or integrating caring for Papatūānuku, can be understood as “technical”. Hence, perhaps key “questions of provocation” being asked, if not revealed, in this research might be: (a) What makes these practice(s) ethical? and (b) In what ways do they contribute to the principles and practices of education for (local/global) ecological sustainability? As one team articulated:

… we are committed to education for children and parents about and for the environment … we want children to see caring for their environment as being a natural process and part of their lives … [PM]

The teachers were somewhere on a journey that would challenge them to integrate an “ethic of care” that, in some way, recognised the dynamic interplay between Māori/Pākehā perspectives as well as the micro/macro: the interstitial (in)between spaces that exist between the early childhood setting, the community and the wider (local/global) world (Lenz Taguchi, 2010). An “ethic of care” as an everyday practice, in relation to local/global environmental and ecologically sustainable concerns (and practices), can be understood as an exploration of the complex relationships between people, places and things. From this perspective, coming to know the (non)natural world, “is as much a matter of feeling as of concepts” (Hinman, 2008, p. 319); it involves a deep connection with, and a coming to know the (non)natural world in ways “that do not involve domination and mastery but rather harmony, balance, and peace” (Hinman, 2008, p. 319). As teachers explained:

… it’s that wonderful ecological feel. [BM]

… the turning point was Matariki. We learnt about and celebrated Matariki … This strongly encapsulated our views and approach … [MB]

However, integrating environmental education/education for sustainability into the policies, the curriculum and in the practices of early childhood education is not without its challenges. Sobel (1999) cautions that expecting young children to engage with ecological issues “prematurely” cultivates a culture of fear that results in cutting children off from possible sources of strength. He advocates policies and practices that foster what he believes is children’s natural empathy with nature. However, many of the teachers worked collaboratively with children, parents/whānau in thoughtful and careful ways that enabled children to engage with complex issues about nature, about the environment and about ecologically sustainable ways of living that were meaningful to them. They were motivated by the intent to, for example:

… involve children, families and teachers in advocacy for child, family and environmentally friendly policies and practices … [CK]

… support children to see caring for their environment as being a natural process and part of their lives. [PM]

3.1.5.2 Connecting with nature

An emphasis in the curriculum on young children learning a “care and respect” for the environment or the “wonders of nature” is not new (Lewin-Benham, 2006; Rosenow, 2008). It is an emphasis that is often driven by a belief—or an image of the child—that suggests children have a natural tendency or affinity to bond with nature or because nature has so much to teach them (Sobel, 1999). However, more recently, for many, an emphasis on nature has arisen because of: (a) a concern for environmental issues that affect all our (local/global) lives—children’s included (now and in the future) —and are a result of our (local/global) human activity; the earthquake in Haiti being a most recent example; and (b) for many writers, a concern that many children—as well as many others in our communities/society—are, for a number of reasons, disconnected from the natural world and that this disconnection has detrimental effects—for individual health and wellbeing as well as the health and wellbeing of the community/society and the environment (Lewin-Benham, 2006; Louv, 2005; Nimmo & Hallett, 2007; Rosenow, 2008; Sobel, 1999). Louv’s (2005) popular award-winning text, Last Child in the Woods, suggests many children today experience “nature-deficit disorder” and calls for:

… a new ‘wonder land’ where the wild things will be: a new back to the land movement, another future, in which children and nature are reunited—and the natural world is more deeply valued and protected … (p. 4)

Although Louv (2005) here promotes a somewhat romantic image of “the child of nature”, a focus on children—as well as teachers, and parents/whānau—(re)connecting with the values of “nature”, the natural world, the environment, the world of Papatūānuku, in meaningful ways was a big focus for many of the teachers/teaching teams for a number of different and dynamic reasons that included:

… Whakamana, respect, a mutual respect between tamariki, children and the environment. Early experiences with the natural world have been positively linked with the development of imagination and sense of wonder. Through these practices children learn about giving back to the earth. They see the cycle of growth in practical terms. Whakamana, we aim to create respect, a mutual respect for tamariki, the children, and the environment. Children develop a sense of mana … [PM]

… Kaitiakitanga, is looking after places, things and people. We have observed our children gain a sense of pride and respect for our kindergarten environment. We believe that when children have the opportunity to engage and care for the natural environment they will gain the skills, knowledge and desire to care for it in the future. The environment is the third teacher … [PM]

… nature helps children develop powers of observation and creativity and instil a sense of peace and being at one with the world … The concept of a puna matauranga, growing a pool of knowledge about the world. [PM]

… over time we’ve made a conscious effort to naturalise both our indoor and outdoor environments. We’ve noticed the difference in the children’s play, in this area. They seem to be more engaged and … it seems to be more of a calming environment. [PM]

… the natural environment stimulates social interactions between children. Tuakana teina relationships provide a model for buddy systems and older or more expert tuakana help that guides a less expert teina … [PM]

… we just believe that wherever there’s harekeke, there’s tūpuna and tūpuna need people around them and they need people laughing and enjoying themselves and being good to each other because that’s what the tūpuna do for us and so we just believe this place is full of tūpuna who are looking after us and enjoying the children laughing and playing and singing … and actually being near the harekeke, or maybe it sometimes [is] in the harekeke … (BM)

… nature is not something we can own, we are a part not above the environment and have a responsibility to use the resources in a way that doesn’t damage the system as a whole … [CK]

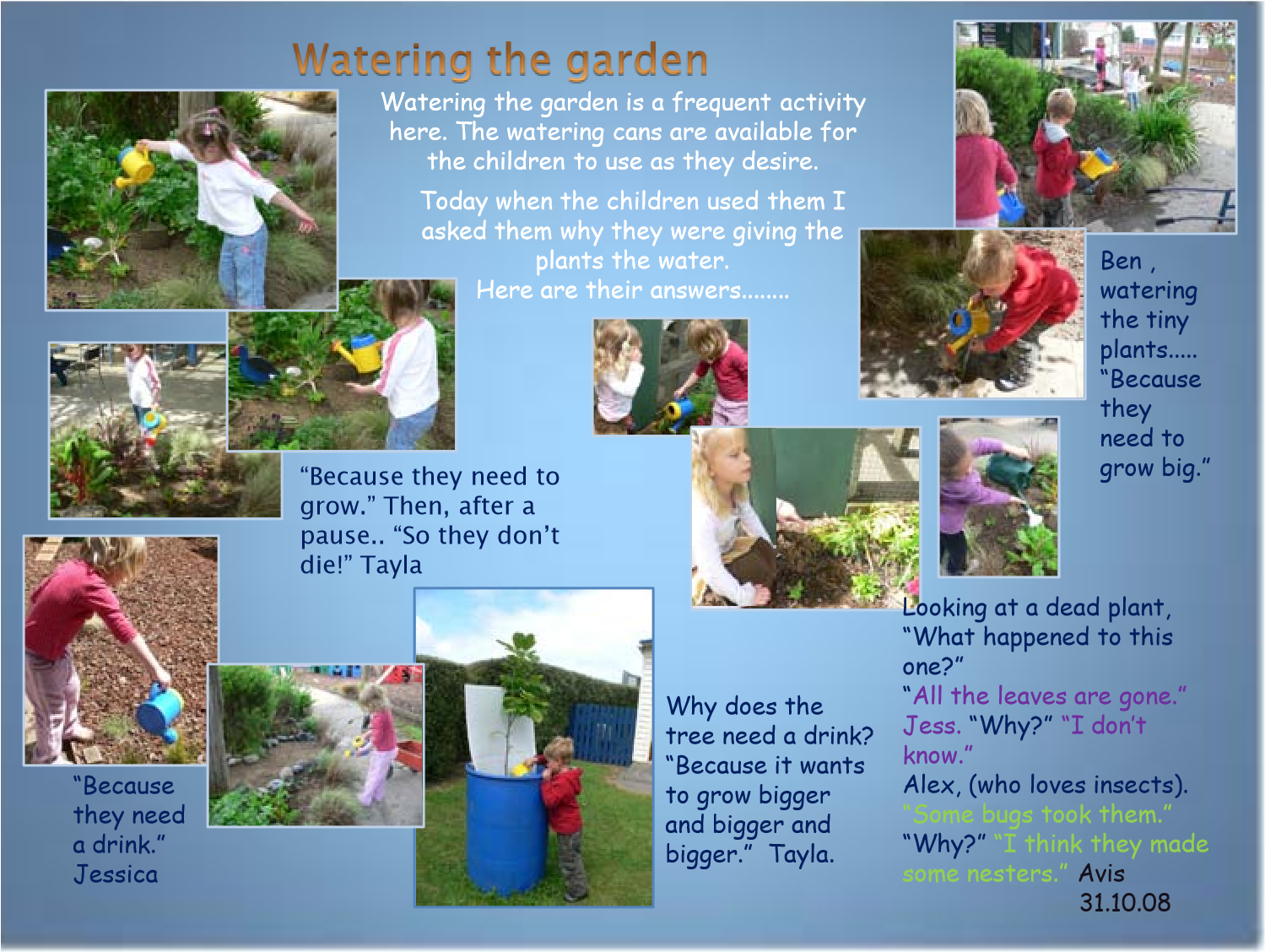

Nimmo and Hallett (2007, p. 1) reinforce the power of the natural world. They note, environmentalists “dream of spaces that belong to nature” to emphasise the importance of having opportunities for, for example, purposeful gardening for children in early childhood settings. They suggest the garden can be understood as a “unique place—a familiar place tamed by humans to serve social purposes such as growing food and meaningful cultural relationships between the work of humans and the complexities and unknowns of the natural world” (p. 32). Developing a love of and commitment to purposeful gardening as an everyday sustainable practice, a way of life, of health and wellbeing, that involves teachers, children and family/whānau (inside/outside the early childhood setting) working together, was fundamental for many of the teachers:

… kids deciding that, yeah I can do real work, not dramatic play stuff all the time, I can do real work … a real garden … and then they go out and get the veggies for tea now. [RC]

… one dad rang me up and he thanked me for making him get outside one night and have to dig over a vegetable garden which they’d never had before but his daughter wanted to plant all her vegetable plants and now they have a regular vegetable garden. [GB]

… we always have available pots and … a range of seeds and children go and plant up seeds whenever they want so planting happens individually … and within our vegetable garden … [GB]

… our vegetable gardens [are] always a source of food which the children use and also we have that free ‘anything extra goes’; whānau are welcome to take it. [GB]

Bates and Tregenze (n.d.) emphasise that the shift from environmental education towards “sustainability education has a broader context of empowering people to take responsibility for making informed decisions towards a sustainable future” (p. 1). They suggest that although the lifelong-learning approach recognises birth as the starting point for crucial learning, this has yet to happen in relation to education for sustainability. Davies et al. (2009) suggest “education for sustainability” in the early years has “the potential to foster socio-environmental resilience based on interdependence and critical thinking … for lives characterized by self respect, respect for others and the environment” (p. 113). For one teaching team, an inclusive approach that recognised an image of the “infant or toddler as learner” and the relevance of ecologically sustainable practices to their lives was fundamental. They:

… view infants and toddlers as powerful and enquiring learners and as active members of the centre community who have much to contribute … caring for each other, their little acts of kindness, helping, having high expectations of social conscience. [CK]

For many teachers, revisiting their understandings of nature and the environment involved increasing their understanding of what it meant to develop deeper and/or other understandings of ecologically sustainable practices—for teachers, parents/whānau and the community—that fostered both a love of and a care and concern for nature and the natural world:

… we looked at our philosophy and also reflected on how central and vital Papatūānuku is to ecological sustainability … if we look after and respect Papatūānuku, she will look after us. [RH]

… we want them to just think about being in the bush … we’ve been able to go up to kahikatea trees and hug them. But this is us starting to look at different places that we can go to … I’d like to take them to the … bush right here in the middle of town and there’s kahikatea in there … [BM]

Several of the teaching teams actively integrating “Māori approaches to environment” into their practices sought new understandings about Papatūānuku that enabled them to be involved in sustaining different knowledges about the world. This involved the teachers finding out about:

… our mountain, water and marae … celebrat[ing] Matariki, locat[ing] and [using] resources that support tikanga within the curriculum. [CK]

… by learning about Rakinui/Ranginui and Papatūānuku we can inspire our children and whānau to consider making ecologically sustainable choices. [RH]

3.1.5.3 Reducing, reusing and recycling resources

Recycling is a big area for education for sustainability. It is responsive to both government and local governing body initiatives to encourage “good citizenship” through “reduce, reuse and recycle” practices as a way of encouraging everyone to consider the impact our human activities are having on the environment—and on climate change (Young, 2007). Selby (2008) is critical of those who suggest education for ecological sustainability is about ecological sustainable development (often referred to as ESD) as it is more appropriate, he suggests, to describe it as “ecological sustainable contraction” (rather than development) as a way of acknowledging the urgency to “pull back”—be responsible with, take care of and use less of the world’s natural/nonnatural resources. Young (2007, p. 1) suggests, “it would be irresponsible for us not to share this information with children, to give them the opportunity to learn how their actions impact on the health of the planet. This knowledge enables children to learn how to be part of the climate change solution, and teaches them that they can make a difference”. However, as one teacher indicated, it is not without its challenges:

… I continue to find it a struggle to make complex and potentially scary issues accessible to children in ways that give them the opportunity to engage and respond. My main way of doing that is to complicate their thinking when the opportunity arises … [CK] Another teacher indicated:

… we’re following the principles of reduce, reuse, recycle and we’ve also added conserve as something we look at as well … there’s the ‘living the practice’ … that we put into place that are sustainable … [and there is] getting the advocacy out there, talking to the children about it, talking to the families about it. Explaining what it is, what it means and the importance to the environment, to us, to future generations … [KM]

… it’s not just about recycling and reducing waste, it’s [about] how it impacts on the environment … [KM]

As is evident, engaging in ongoing critical reflection to examine their philosophical beliefs and values added depth to their understandings—broadening their outlook in the processes and practices that enabled young children to be actively involved in these complex issues, as the teachers realised:

… reducing the amount of rubbish by choosing products for the children’s lunchboxes … also, changing the type of packaging. It is one small step towards environmentally sustainable practices but one that we can easily see results from. It is a good place to start for us to feel we are doing our bit for the environment … [KM]

… as a team we’re now into the recycling, reusing, renewing sort of mode and the thing is that it’s recycling with all the sorts of paper—not just your usual recycle that you put out in the garden or at the gate for your council to collect but we’re becoming really conscientious of just scrap paper. The children are now on board to put that to one side and we recycle that and we’re … taking it further and further … [GB]

Having a knowledge and understanding that informed teaching and learning practices was as important for many of these teachers as it was that doing something could make a difference, albeit a small step. They sought the knowledge and understandings they needed to inform the decisions they made about changed practices. As one team explained, they were keen to reduce the:

… level of rubbish production at kindergarten and to help our whānau think about the choices they are making for food storage/preservation coming from home. [RH]

Teachers reiterated their knowledge and understanding to parents/whānau to ensure that they, too, understood the ecological issues at stake:

… packaging makes up 50 percent of all the plastics in landfills. As plastic is not biodegradable, this is creating a massive rubbish problem that will not go away, it will remain a problem for our children and grandchildren … [KM]

Sharing this kind of information with parents/whānau rationalised the changed practices they expected parents to make in support of the practices to reduce, reuse, recycle rubbish within the centre. For example, “litter-less lunchboxes” required parents to use alternative wrappings/storage processes in their children’s lunchboxes.

As is the tradition of early childhood education’s integrated approach to curriculum (Davies et al., 2009), the strong emphasis teachers placed on reducing, reusing and recycling as an integral component of the everyday curriculum practices resulted in a variety of experiences. These were integrated within/across the learning environment, within a range of curriculum areas, in ways that permeated the culture of the centre. A few examples include:

… this is the recycling row where the children learn which things go into which bins …

… the rubbish … collected was sorted and made artwork out of

… we did the wearable arts …

… we incorporate [yoga] into our mat times …

… making our own recycling … our recycled paper ….

… the children helped set up the worm farm … we collected some juice from our worm farm … we keep the worms moist so the worms don’t dry out …

… we made up a chart of daily chores … planting … watering the garden, recycling paper …

… they use the shredder to shred the [used] paper … they put it in the barrel then it’s put into a brick maker and it makes solid bricks ….

… we’ve … had this recycled sandpit shed made, and a parent has built us a carpentry shed out of recycled wood and corrugated iron …

… we don’t use plastic bags anymore, we provide cloth nappies, we garden, compost, recycle, children bring largely rubbish-free lunch; we buy less, use our local supermarket as much as possible, switch to eco-store cleaning products, buy ‘Fair Trade’ products …

… we discussed the elections with the children and they made a banner and some posters for display that included their ideas of what was important for children and families, and we displayed that on [the] road so that the cars could see …

… [we walk] to explore the local park … and the shops and community and library …

3.1.6 Conclusion

This chapter has provided an overview of teachers’ voices gleaned from the research data that provided them with opportunities to articulate the philosophies and approaches that they produced as they strived to put in place policies and practices in support of environmental education/education for sustainability. Davis (2009) noted that there has been little research published that recognises “young children as agents of change around sustainability, what can be called education for the environment” (p. 235). Although children’s voices are invisible here, what is visible is that the teachers in this research were working towards (some already had a sense of what this meant in practice) developing an image of themselves, the children and the parents/whānau as “advocates for sustainability” and as “agents of change”. Although their knowledge and understandings of what Siraj-Blatchford (2009) refers to as a “radical engagement” in education for sustainability might entail in practice has grown throughout the duration of the project, it is not without a feeling sometimes that this is something that is “too big”, something that is overwhelmingly difficult to get a handle on, to make a difference. Yet they recognise that journeying as a life and way of life centred within a philosophy that fosters ecological sustainability policies and practices—over time and across spaces—is inevitable and an ongoing collective project with lots of little steps along the way. This is best surmised through teachers’ voices:

… it feels like we have only just begun as we all learn … [we are] continuing to internally review our practices and environment with a green lens … more networking with New Zealand and worldwide to gain and share ideas that can improve practice(s) in education for sustainability … we have talked about using our local environment more for teaching and learning based on our research from forest kindergartens in Europe. [PM]

… we were thinking about … how can we support others and certainly it’s only an early journey for us, but a little about spreading that, and so … we put a proposal together … about developing an education for sustainability policy, and that’s in its early stages but it just brings that to the fore and also engaging our other kindergartens and what way we can support [them] in practical terms really … putting ourselves out there a little more than we might’ve felt we were comfortable about doing … [Senior Teacher, Tawanga Kindergarten Association]

… The concept of whakawhanaungatanga, a sense of community; through the young child we have the opportunity to influence change in family and community behaviour by involving, connecting and educating them in an environment … and environmental awareness and sustainable practices; it is so important to create a sense of belonging, a sense of tūrangawaewae, within the kindergarten community, and not working in isolation. The community has a lot to offer that we value being a part of. Whakapapa, Māori genealogy, links us with the whenua, our land, moana, our sea, and cultural concepts working with family and whānau. And our pepeha, the children’s genealogy and where that comes from increased our connections, relationships and valuing who people are and where they come from. Children see adults talking and connecting with each other which gives them a sense of mana and pride. [PM]

3.2 Te Ao Māori

Knowledge that endures is spirit driven. It is a life force connected to all other life forces. (Meyer, 2008, p. 218)

Ancient Te Ao Māori epistemology is whakapapa layered, the domains of Te Ira Atua (godly element), Te Ira Tangata (human element) and Te Ira Wairua (spiritual element) an interwoven multidimensional merging.[1] Whakapapa (origins) conceptually embody Māori perceptions of the relationship of the individual in connection to all other things. It is a kaupapa attained and realised through Māori pedagogical processes, one which acknowledges a whakapapa that connects Māori to all things that exist in the world: “We are linked through our whakapapa to insects, fishes, trees, stones and other life forms” (Mead, 1996, p. 211). Knowledge of whakapapa establishes one’s tūrangawaewae, a place of belonging connecting mokopuna to tupuna, whānau, hapū, iwi and whenua, and to the universe. Mokopuna are the imprint of their tupuna, whānau, hapū and iwi (Ka’ai & Higgins, 2004). Māori knowledge, values and beliefs are bound in the procreative pūrakau/Māori reality. It is a narrative that highlights qualities of integrity and relatedness to Ranginui and Papatūānuku, to an intertwined spiritual and cultural relationship with nature. It is within these embedded energies and aspects that Te Ao Māori ecological principles reside.