1. Aims, objectives, and research questions

There is very little documented research information about New Zealand teachers’ and children’s attitudes, knowledge, and values regarding the Arts. There has been a major change to the school curriculum (with the Arts becoming one essential learning area) and there are reported difficulties in the teaching and learning of the Arts within primary classrooms (Education Review Office, 1995, 1999). However, there is also evidence that a curriculum leadership model allowing teachers to selectively develop discipline knowledge according to needs works well in instances where schools have committed themselves to a climate that supports a learning culture (Beals, Hipkins, Cameron, & Watson, 2003).

In the international context, there is growing evidence of the importance of learning in the Arts. Richard Deasy (2002), introducing a compendium of 62 studies entitled Critical Links: Learning in the Arts and Student Academic Achievement, noted that: “All of the essayists agree that future research needs to define with greater depth, richness and specificity the nature of the Arts learning experience itself and its companion, the Arts teaching experience” (p. 6). This was locally reiterated by O’Connor, Brodie, Dunmill, and Hong (2003).

There is some New Zealand evidence that teachers lack confidence in teaching drama and dance, but indicate more comfort with the teaching of visual art and music (Hipkins, Strafford, Tiatia, & Beals, 2003; McGee, Harlow, Miller, Cowie, Hill, Jones, & Donaghy, 2003). However, there is no fixed relationship between teacher confidence and teacher efficacy, so the issue of confidence itself may not be the pedagogical issue of concern. Moreover, research by the National Educational Monitoring Project (NEMP) and the Education Review Office (ERO), found that just over half of the schools sampled had adequate visual art programmes and only 13 percent of schools had music programmes that met children’s needs (Ministry of Education, 2006b). There is also local and international evidence that some teachers over-rely on certain “ritual patterns” of practice (Efland, 2002; Nuthall, 2001) in teaching and that these formulaic ways of framing professional knowledge can impede teaching and learning. Such issues warrant further research to examine their veracity and to provide the basis for the trialing of approaches that build capability in teaching and learning in the Arts.

In a dual focus, this project investigated what children bring to the Arts areas with a focus on development of ideas and related skills in each of the Arts disciplines (Craft, 2000). The indication from adviser reports and curriculum reviews is that there is little understanding by teachers of learning progressions in the Arts, particularly in dance and drama (Ministry of Education, 2006b). By focussing on children’s learning in the Arts, one is in a stronger position to ascertain the ways in which teachers can effectively facilitate children’s learning processes (see “Developing ideas in the Arts” strand of The Arts in the New Zealand Curriculum, Ministry of Education, 2000). Second, it investigated what key, selected teachers teach and what children learn in each of the Arts disciplines. It examined the nature of any “ritual patterns” of teaching that support or constrain Arts education, and by doing so, considered ways of developing pedagogical processes that deepen children’s experiences and understanding in the Arts.

As a major outcome, the project provides an insight into how teachers can deepen and extend children’s experiences, understanding, and engagement when they are learning in the Arts in primary classrooms.

The overall aim of the project was to investigate how the development of ideas in the Arts can be promoted, enhanced, and refined in primary classrooms, and in doing so, build knowledge related to Arts pedagogy and research. There was also the associated aim of capacity building for Arts research amongst university and teacher partners.

Objectives

In order to achieve this aim, University of Waikato (UoW) researchers, in conjunction with teacher–researchers:

- compared and contrasted the particular processes and skills that children employ in classroom programmes in developing ideas within music, visual art, drama and dance, and in the process identified differences, contrasts and concerns

- reviewed the literature on Arts education and Arts educational research

- interrogated learning and teaching in the Arts in respect to children’s development of ideas

- ascertained the pedagogies and philosophies that enhance the development of ideas and related skills in and through each of the Arts disciplines

- trialled and evaluated some interventions (designed in collaboration with schools) that aimed to extend ways in which teachers can deepen children’s learning when they are working in the Arts.

Research questions

In order to achieve these objectives, the following research questions guided the project:

- What features characterise the classroom practices/processes of a sample of teachers engaging children in activities aimed at developing ideas and related skills within one or more of the Arts disciplines (music, visual art, drama, and dance)?

- What are the children’s perceptions of their own idea formation when engaged in developing their ideas in the Arts?

- What factors and related discourses shape child and teacher understandings of how ideas and related skills can be developed in the Arts through a range of classroom practices/ processes? How do these discourses relate to each other and to the larger context of the school and the national policy environment?

- Taking into account current research and literature and the professional knowledge of participating teachers and researchers, what pedagogical practices might be expected to enhance the development of children’s ideas and related skills in and through each of the Arts disciplines?

- What specific interventions, at either school or classroom level, appear to enhance the development of children’s ideas and related skills in and through the various Arts disciplines?

2. Research design and methodologies

The project drew on ethnographic, case study, and action research traditions of educational research. In keeping with naturalistic inquiry, this project recognises that “meaning arises out of social situations and is handled through interpretive processes” (Cohen, Manion, & Morrison, 2000, p. 138). Teaching and learning practices and the meanings one attaches to them are also context-related and socially constructed. In this respect, the project’s aim to deepen understanding and extend practice can be related to an aim to identify those salient features which underpin teacher and child understandings, and Arts-related classroom activities and practices in general.

The design of this study is responsive and open to the unexpected, the unpredictable, and the expressive as is particularly relevant in the Arts (Eisner, 2002). This two-year study richly documented, but also critically scrutinised in a collaborative way the lives and experiences of teachers and children as evidenced through Arts education. As a result, it aimed for a deeper understanding of what students know, what they need, and what constitutes effective Arts pedagogy. Eisner argued:

What we need are empirically grounded examples of artistic thinking related to the nature of the tasks students engage in, the materials with which they work, the context’s norms and the cues the teacher provides to advance their students’ thinking. (2002, p. 217)

The project included three university staff and 10 generalist teachers (Years 0–6) across eight schools as co-researchers willing to focus on at least one Arts form and specialist/lead teachers working across syndicates within the primary school setting. At the proposal stage, a number of local schools expressed interest in examining and extending the potential of the Arts in education. Some had been involved in Arts teaching development work and were interested in research that helps them to understand more about the teaching-learning nexus in the Arts. This research partnership, therefore, met the needs of both schools and TLRI goals in that the inquiry focussed on questions of practice of importance to teachers and the profession.

The partnership schools have Arts education practices that show commitment to delivering successful Arts programmes by staff in a supportive school context. Indications of commitment have been validated by recent Arts professional development, adviser advocacy, and supporting Education Review Office (ERO) reports. Supportive principals in a range of schools (see Table 1) confirmed their interest in their staff participating in the project as a way of building on their already existing relationships with the University of Waikato. The sample is inclusive across decile ranges, distinctive ethnic populations, teacher strengths, and urban and rural contexts around Hamilton and the wider Waikato region.

A) University of Waikato researchers and practitioners

| Project director/researcher: Project researcher: Project researcher: Project manager: |

Dr Deborah Fraser Clare Henderson Graham Price Carolyn Jones |

Consultative Reference Group members: The School of Education at UoW has a consultant team with expertise in researching, learning, and teaching in the Arts. These people contributed to this project: Associate Professor Terry Locke, Dr Viv Aitken, Dr Karen Barbour, Sue Cheesman, and Cathy Short.

B) Original 2005 group of teacher–researchers and buddies (see Table 1)

| School | Frankton | Ham East | Hukanui | Hillcrest | Pukete | Piopio |

| Decile | 3 | 4 | 10 | 10 | 7 | 4 |

| Ethnicity | 50% Päkehä 42% Mäori 5% Pasifika 3% Asian |

42% Päkehä 29% Mäori 11% Somali 10% Asian 8% Other |

81% Päkehä 13% Asian 3% Mäori |

71% Päkehä 19% Asian 6% Mäori |

75% Päkehä 19% Mäori 6% Other |

77% Päkehä 20% Mäori 3% Other |

| Art | Francis Pye (lead teacher arts) Year 4 |

Olive Jones Year 4Maggie Frost Year 1 |

Shona McRae Years 5/6 | Marianne Robertson | Judith Blake Year 4 | |

| Music | Philippa Defluiter Years 5/6 | Kelly Thompson (lead teacher arts) Years 2/3 |

Fiona Bevege Year 0 | |||

| Drama | Irene Cheung Years 3/4 | Shirley Tyson | Gay Gilbert DP Years 5/6 |

Judith Blake Year 4Liz Amoore Year 4 |

Amanda Klemick Years 1/2 | |

| Dance | Olive Jones Year 4Jude O’Neil |

Shirley Tyson DP Years 5/6 |

Fiona Bevege Year 0 Amanda Klemick |

The school partnerships arose through the University of Waikato’s awareness of longstanding relationships with Arts innovation and practice with supportive administrative leadership. All of the schools had participated with in-depth models of Arts professional development provided under Ministry contract from 2001–2004. Key practitioners emerged as Arts curriculum leaders and operated within syndicates or across their school. Of the eight initial teachers, four held arts leadership responsibilities within their school and two were teaching deputy principals who lead the Arts development in the school. Four of the teachers operated within a semi-specialist role for teaching an Arts discipline beyond their own classroom. Two teachers were Arts informed generalist teachers who have more than one arts discipline as their strength .All were reflective practitioners with an expressed interest in participative research. They also indicated an existing “critical friend” or buddy relationship within their school. They have much to offer the “blue skies” edge of current arts education practice in primary settings. Collectively, their student communities represent a spread of student ethnicities, decile rating, urban-rural communities, and levels of schooling from Years 0–6 (see above).

C) Teacher–researcher changes

As is inevitable in any classroom-based study spanning two years, there were changes to staff, and as a corollary to schools, involved in this project. Phillippa Defluiter was unable to start the project due to a serious family illness. She was replaced by Fiona Bevege at Piopio who initially was Amanda Klemick’s buddy. Shona McRae left Hamilton at the end of 2005 to live in Dunedin. She was replaced by Lisa Rose of Tauriko school (Bay of Plenty) in 2006. Kelly Thompson left Pukete school to go on parental leave at the end of 2005. She was replaced in 2006 by Andrea Goodman of Cambridge Primary. Olive Jones left Hamilton East at the end of 2005 as a result of winning a research fellowship to study at the University of Waikato. She was initially replaced by her buddy Trish Bush who moved to Fairfield Intermediate. However, Trish was unable to continue in the project. So, in the end the project involved eight different schools and 10 teacher–researchers.

The children involved also changed as teachers had new classes in 2006. Therefore, informed consent processes needed to be repeated with hundreds of children and their parents/caregivers. For schools new to the project (Tauriko and Cambridge Primary) project agreements and ethical consents had to be negotiated with principals and boards of trustees at the commencement of 2006.

D) Methodology

This project employed an eclectic research methodology, tailored to address the above research questions and described briefly as follows.

Case study

Case studies allow for an in depth investigation into specific instances with a view to developing or illustrating general instances (Stake, 2005). In the case of this project, the specific instances are classes and schools. As Yin (1989) pointed out, case study research can be:

- exploratory (description and analysis leading to the development of hypotheses)

- descriptive (providing narrative accounts and rich vignettes of practice)

- explanatory (offering causal explanations of the impact of various interventions).

Case study methodology is particularly pertinent to questions 1 and 4. In addition, aspects of ethnographic research (rather than a complete ethnography) were used for descriptive analysis to achieve insider case studies that are both story-telling and science (Fetterman, 1998). Fetterman’s reference to insiders is pertinent here, in that this project methodology collaborated with children and teachers in ways that collapse the insider/outsider distinction that characterises “them/us” research.

Action research

Unlike positivistic research models, action research is adaptive, tentative, and evolutionary (Burns, 1994). This research model has also been undertaken because of its commitment to selfreflexivity, collegiality, and critique. “Action research is an enquiry by the self into the self, undertaken in company with others acting as research participants and critical learning partners” (McNiff, 2002, p. 15). Action research, given its cyclic nature and focus on the trialling of interventions, is particularly pertinent to all of the research questions. Action research is particularly suited to the empowerment of teachers as researchers. Moreover, in line with issues of validation (see McNiff, 2002), teacher–researchers used critical friends, research buddies in their respective schools and validation groups—all of which are potential aids to quality assurance and dissemination.

Self-study

Finally, in order to examine these questions, the staff involved (both university and school staff) drew upon self-study methodology within this action research framework. In this respect, McNiff’s statement above regarding critical self-reflexivity is most pertinent. As Carr and Kemmis observed: “practices are changed by changing the ways in which they are understood” (1986, p. 91). Self-study encompasses a belief that who one is, is significant both in the teaching and researching process (Loughran, 1999). The fact that the assumptions that support and/or constrain one’s practice and experience are examined within the educator’s work context is an important facet of self-study. Such an approach clearly positions the researcher as part of the social world at the heart of the study and leads to a focus on the “researcher-self” (Alvesson, 2002, p. 171) and to varying degrees either the researcher’s personal experience, or explorations of the experiences of those with whom the researcher is involved in a day-to-day basis, are placed at the centre of the study. Self-study is particularly pertinent to questions 3 and 5.

University and teacher–researchers inevitably faced issues (including ethical ones) given the insider/outsider tensions, the familiarity all have with classrooms, and the associated difficulties with reconceptualising how things might be done. These will be discussed in more detail later on in this report. Throughout the project, collaborators needed to exercise caution in their examination of practice and strive to resist premature closure. All parties needed to hold the tension of apparent contradictions, being both interested (in effective Arts pedagogy) and disinterested (in order to heighten perception) so that they might “surprise themselves in a landscape of practice with which many are very familiar indeed” (McWilliam, 2004, p. 14).

E) Methods

An eclectic range of methods were employed to capture rich, triangulated data. These included:

- surveys

- classroom observations (of e.g., teachers, class, focus groups of five children, individuals— through timed running records, video and audio-tape)

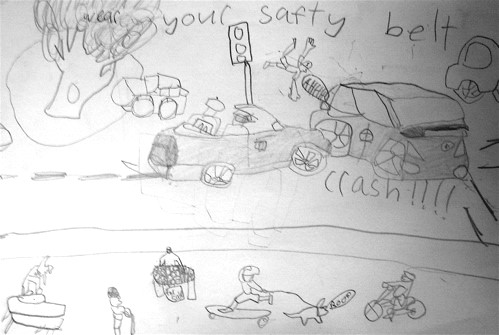

- work samples (e.g., self-assessments, matrices, digital camera shots, audio and video of ideas-in-progress, children’s interactions and work completed/performed)

- interviews (with teachers, with children in focus groups of five, informally with individual children while working and sometimes after their lessons)

- document analysis (e.g., teachers’ planning, school policy statements)

- reflective self-study comments (e.g., emails, field notes, musings ‘journal’ entries, phone conversations).

Case studies of teachers’ existing practices were produced by the team of teacher and university researchers and these highlighted themes and issues related to how children develop their ideas in the Arts and what appears to support or constrain this process (see project findings section). The case studies were devised from an amalgam of classroom observations, work samples, surveys, interviews, and reflective self-study comments. Perspectives from teachers, university staff, children and school policy documents helped to build rich, triangulated sense-making accounts of current practice (Stenhouse, 1985). These case studies provided a platform upon which to base the action research phase wherein teacher–researchers devised questions of concern to explore problems, issues, and possibilities. Ongoing discussion amongst all the research team enabled the refining of both questions and methods. Teacher–researchers were assisted in this process by the university-researchers acting as critical friends as well as joint investigators (see also Ewing, Smith, Anderson, Gibson, & Manuel, 2004). This action research cycle formed the majority of the 2006 focus. The questions included:

- What effect does nonverbal feedback and feedforward have on the exploration and development of ideas in dance?

- What effect does children working as individuals, and as pairs, have on the development and refinement of ideas in music?

- What is the impact of symbolic representation on the development and refinement of children’s ideas in music?

- How are students currently exploring, generating, and developing their ideas in the visual arts? What supports or constrains students’ self-directed imagery using learned skills and strategies?

- What is the influence of teacher-in-role on children developing and refining their ideas in drama? In what ways can teacher-in-role contribute to deepening the drama and children’s ownership of ideas in drama?

These questions provided direction for ongoing data collection that enabled a close scrutiny on learning and teaching in the Arts. They represent the authentic or felt questions, issues, and concerns of the teachers themselves (Lankshear & Knobel, 2004) as they strove to scrutinise and extend their current practice. Teacher ownership of their questions is vital during collaborative action research and it affirms their knowledge as practitioners and as developing researchers.

F) Analysis

Initial data were shared after each lesson with each teacher–researcher and a summary was coconstructed on what seemed to support and what seemed to constrain learning in the Arts. Any other salient points that neither supported nor constrained were noted as “interesting”. The strength of this analysis was its immediacy (as close to the action as possible) and the coconstructed nature of it in order to capture multiple perspectives. The analysis also helped to identify any “rituals of practice” that were part of each teacher’s practice.

Second, teacher–researchers were involved in analysis alongside Arts educators, consultants and a lecturer in human development (all whom comprise the Arts project team) at regular roundtable meetings. Specific data, such as video clips from the classroom teachers’ rooms, were shared and analysed initially through a process of description, in order to avoid premature judgement, based on what each person sees. After each person spoke one-by-one, the same data were discussed a second time based this round on what each person interprets from what they and others saw. This describe-then-interpret process (Feldman, 1973) has helped the team withhold initial judgements, avoid defensiveness and minimise the biases that leaping to judgement usually entails (Claude, 2005). The teacher whose class was being viewed was asked to record what each person says, a role that also helped to minimise defensiveness. This process does not guarantee freedom from bias, but rather, helps to mitigate and counter seeing what one chooses to see. Hearing each person’s interpretation often provides contrasts and refinements and any agreements help build analysis that is robust and reliable.

Both inductive and deductive processes were used. For example, in a deductive fashion, theories such as the notion of “rituals of practice” were drawn upon to illuminate and organise data. However, empirical data grounded in observation and so forth were inductively used to determine categories.

G) Ethical considerations

Justification

The obvious implications of the research evidence to date, coupled with the motivation to focus on implementing the Arts in the New Zealand curriculum in greater depth (Beals et al., 2003), precipitated the imperative to conduct New Zealand-based research specific to the context of Arts education in New Zealand .This research study is significant in that it acknowledges the need for quality research on the Arts in New Zealand schools that investigates, first, how children learn in the Arts, and, from this, the factors that contribute to effective teaching in the Arts.

Access to participants

Ongoing discussions with schools, school support services, and colleagues identified teachers who participated in this project. The University of Waikato’s School of Education’s ongoing relationship with these schools and teachers laid a sound foundation for the further development of collegial relationships around the research process. A partnership agreement outlining roles and responsibilities for project partners was discussed and signed which confirmed involvement.

Once the project was approved, access to schools and classrooms was confirmed officially through the boards of trustees of the schools involved. The teachers on the research team assisted with this process and contributed to the full ethics proposal required by the School of Education’s ethics committee at the University of Waikato. The teacher–researchers were also responsible for ensuring that the ethical guidelines of their particular schools were adhered to.

The children concerned were those taught by the teacher–researchers. However, it was clarified, through introductory letters to parents/caregivers (via the boards of trustees of each school) that children were not obliged to provide data in any form if for any reason they did not wish to be involved. Given that the data collection was complemented by the classroom programme, there was little cause for concern. However, a couple of parents/caregivers specifically requested that data were not collected about their child/ren and this was respected.

For those parents/caregivers for whom English is not a first language, and for whom written letters may have been an obstacle for clarity, the school was consulted with regard to alternative and culturally appropriate means of communication, preferably in parents’/caregivers’ first language.

Informed consent

With the teacher–researchers concerned, it was hoped that since they were part of the research process they were unlikely, given their collaborative role in this project, to withdraw. However, this possibility cannot be precluded and there were a number of teacher–researcher withdrawals and changes for circumstances outside the realm of the project (see C) Teacher–researcher changes for details under Research design and methodologies).

Included in an introductory letter that outlined the purpose of the study was a consent form that all participants are asked to sign and return. It reinforced that participants have the right to decline or withdraw with no questions asked, but did clarify that once the project is underway it is preferred that commitment be ongoing. The introductory letter also explained what the collected data could be used for in terms of milestones, publications, and presentations.

A special consent form was designed for the children of each class. This included visuals of what they might be involved in, alongside simple descriptors, with a place to sign and date. It also outlined that they were under no obligation to participate and that they would not be cited without their consent. All but one child gave their consent to participate and that child changed his mind (not due to any coercion) and did decide to sign. All the children’s and parents/caregivers’ consent forms were marked off against a roll by the teacher–researcher and the originals were kept safely at the University of Waikato.

Care was also taken during all preliminary stages that teachers and schools were fully aware of the commitment involved so that expectations were shared. This was addressed to a considerable extent by the teachers’ involvement in planning some of the specifics and the ongoing evolution of the project as a result of joint roundtables, research analyses, and the action research cycle of plan-evaluate-plan. Obviously, there were times when the schools involved were committed to other important events, such as parent interviews, so care was taken to time research activities around such events to maximise opportunity. Care was also taken to negotiate roundtable meetings months in advance to help schools with booking relievers and maximise teacher–researchers’ attendance.

Potential harm to participants

It was important that no participant felt that they were being judged on their efficacy as an Arts teacher or learner. The aim of this study was to ascertain what the current situation is in the teaching and learning of visual art, music, dance, and drama and then to jointly plan interventions that intend to further the development of ideas in the Arts. Care was taken to ensure that teacher–researchers recognise that issues that arise are of direct interest and importance to the project, not a problem or criticism of any person. Processes that were employed to minimise harm are further outlined in the section on contribution to building capability and capacity.

Ongoing dialogue between all staff involved (university and school) highlighted the nature of action research and consolidated mutual understanding of the project’s aims. When necessary and appropriate, consultants were invited to support staff as they jointly pursued research tasks.

Other

Quality assurance was ongoing through consultation with external experts in the field (both academic and professional) who provided invaluable feedback (see the list in Acknowledgements). Cognisance was also taken of the feedback that the children provided and teacher release was necessary at certain crucial stages (in addition to the roundtables) so that teacher–researchers had the uninterrupted time, energy and focus to discuss data collection processes and scrutinise and comment on emerging findings.

H) Project timetable

Project team roundtable meetings included teacher–researchers and University of Waikato (UoW) research team, buddies and often consultants. M.1: is Milestone 1 due date.

| Phase 1 | |

| Dec 2004 | Initial project team round-table: Initial discussion cycle surrounding problem definition and planning of initial data collection. |

| Feb–May 2005 M.1: 31 Mar 2005 |

Ethical consent procedures. Initial sound and vision checks plus data collection round in schools by teacher–researchers and UoW researchers. Identification of initial issues arising in data collection and the research partnership. |

| Phase 2 | |

| Jun 2005 M.2: 30 Jun 2005 Jul–Sep 2005 |

Three rounds of data collection in schools by teacher–researchers and UoW researchers—refining of observations. Second project team round-table: Collaborative analysis of data extracts and identification of emerging categories/themes for case studies. Co-construction of case studies. |

| Mid-Sep M.3: 30 Sep 2005 Oct–Nov 2005 |

Further collaborative analysis of data collection and refining of observation schedules. Teacher–researchers trialing research in buddies’ classrooms. Third project team round-table: Co-construction of final case studies; teacher–researchers sharing with buddies. Discussion of research questions for the action research phase. |

| Nov–Dec 2005 M.4: 31 Dec 2005 |

Fourth project team round-table: Refinement of research questions and methods for the action research phase. Preparation for 2006. Initial dissemination period (Teacher Research Symposium, UoW). |

| Phase 3 | |

| Dec 2005–Feb 2006 M.5: 31 Mar 2006 |

Bringing on two new schools and teacher–researchers. New round of ethical consents for all parents/caregivers and children. Trialling methodology to scrutinise new questions. Teacher–researchers working in their own schools, with UoW researchers, to examine questions, leading to trial of interventions. |

| Mar–Apr 2006 | Trialling interventions in schools and collection of intervention-related data. |

| End of term 1 | Fifth project team round-table: Report-back of intervention-related data, refinement of interventions. Second dissemination period (Dialogues & Differences Conference, Melbourne). |

| May–Sep 2006 M.6: 30 Jun 2006 |

Trialling interventions in schools and collection of intervention-related data by teacher–researchers and UoW researchers. |

| Phase 4 | |

| Sep 2006 M.7: 30 Sep 2006 Sep–Nov 2006 |

Final project team round-table: Analysis and evaluation of interventions and discussion of overall project findings. Summary of commonalities emerging from each Arts discipline. Implications for current practice and further research. |

| Phase 5 | |

| Nov 2006–Dec 2006 | Final analysis, conclusions, and report writing by UoW researchers. Third dissemination period of project findings and conclusions (NZARE, Rotorua). |

| Final Report due 31 December 2006 |

3a. Project findings: research questions

The initial research questions are listed again here and each of these is discussed under the themes that emerged to follow:

- What features characterise the classroom practices/processes of a sample of teachers engaging children in activities aimed at developing ideas and related skills within one or more of the Arts disciplines (music, visual art, drama, and dance)?

- What are the children’s perceptions of their own idea formation when engaged in developing their ideas in the Arts?

- What factors and related discourses shape child and teacher understandings of how ideas and related skills can be developed in the Arts through a range of classroom practices/ processes? How do these discourses relate to each other and to the larger context of the school and the national policy environment?

- Taking into account current research and the professional knowledge of participating teachers and researchers, what pedagogical practices might be expected to enhance the development of children’s ideas and related skills in and through each of the Arts disciplines?

- What specific interventions, at either school or classroom level, appear to enhance the development of children’s ideas and related skills in and through the various Arts disciplines?

Rituals of practice

In terms of the features of classrooms that characterise teachers’ pedagogy in the Arts the initial case studies, co-constructed in the first year of the project, provided a wealth of detailed material including a number of “rituals” or common practices that were a largely unconscious part of teachers’ repertoires (Efland, 2002; Nuthall, 2001). These rituals or largely taken-for-granted assumptions, could either support or constrain what happened when children were learning through and in the Arts, depending on the context and goals of the lessons, and the children’s needs. These rituals included the following:

- An emphasis was on the teaching of practical knowledge, with minimal attention or time given to the teaching of artistic idea development and structuring.

- Group work in dance, drama, and music was a common practice for both management and pedagogical reasons.

- Visual art was usually undertaken individually even if children were placed in groups.

- Teachers chose the topic or theme to be explored and this was usually framed by narrative. While these were open-ended enough to allow children to locate their experiences, deviation from the set brief was rare.

- Resource choice was usually made by the teacher; children chose from a pre-selected range of resource material.

- An emphasis was on brainstorming ideas, explaining, sharing, and interpreting art skills and processes in words, mostly spoken and sometimes written.

- While the value of process was recognised, explicit valuing of subtask completions, presentations, and finished work was often foregrounded.

- In the performing Arts, feedback on work was given mostly at the end of a session and if time limitations prevailed, was vulnerable to being foreshortened or eliminated.

- Reflection and evaluation of work produced was generally through an adult lens; perceived “best” Arts practice drew on a limited range of adult Arts paradigms and genre.

Overall, the initial case studies revealed a main emphasis on practical knowledge or the teaching of Arts skills and elements, determined and defined by the teacher. This emphasis on skills and elements tended to take priority over clarifying and deepening how ideas might be developed in the Arts. However, there is a distinct and important relationship between practical knowledge (PK) and development of ideas (DI) and both are necessary in the creative process. The relationship between these two, therefore, requires careful consideration. Too little PK lessens the quality of DI exploration and the communication of ideas. Skill development is necessary and essential in learning as greater grasp of skills offers greater opportunity for exploration, refinement, and flexibility to express one’s ideas. But PK can also constrain and dominate to the extent that DI is minimised or overlooked. Too much PK conveys the message that skills and elements are paramount, including the meeting of learning outcomes which are often based on that which is observable and measurable. PK that is tightly scaffolded by the teacher can easily become a management strategy, more than a pedagogical technique. Such PK provides children with skill progressions and a sense of accomplishment from seeing growth in their ability to create in the Arts. However, PK by itself does not take thinking very far and too much PK can hinder, even annihilate thinking, if compliance to conventions becomes a paramount goal.

Development of ideas is a much more elusive concept wherein possibilities are considered, explored, tested, rejected, resurrected, and pushed in directions that are not wholly determined at the outset. Eisner (1994) maintained that the Arts need to allow for flexible purposing and expressive outcomes. Behavioural objectives with their clearly defined learning outcomes can be too closed for the unknown directions that Arts creation needs. This freedom to explore is necessary if Arts programmes are to go beyond the information given (Bruner, 1974) and enable children to bring their imaginations to the task at hand. Noteworthy was the fact that the initial case studies often revealed that exploratory play was marginalised in favour of carefully defined criteria such as “we are learning to” lists.

Moreover, DI requires ongoing qualitative assessments where the development is towards something better. This does not preclude setbacks and regressions which are part and parcel of the messiness of learning. Learning does not proceed smoothly in a linear, staircase fashion (Barker, 2001; Claxton, 1999) despite what some models of human development have claimed. Good learners, according to Claxton (2002, p. 18), like a challenge, know that learning is sometimes hard, are not afraid to make mistakes, and like the feel of learning. It seems that development of ideas requires the elements of “good learning”. This good learning is invariably aimed towards improvement; something that is qualitatively better than before.

The initial case studies showed that children’s first idea response to a challenge or task in the Arts was often accepted and considered the best response. There were few and sometimes no opportunities given to repeat, refine, review, and revise. In contrast, skills were often built upon through revision and extension, especially in the skill dominant classrooms. A slightly different tension emerges for teachers using a process drama approach where first response is often valued as better or at least “truer”. In “lived through” process drama, the emphasis is often on the spontaneous and the authentic response, rather than reworking towards a polished product. Even in a process drama approach, however, there are times where responses may be reworked and refined, thus, the spontaneous and the more polished can co-exist.

The initial case studies showed that little cognisance was taken of what children brought to the Arts in terms of their existing knowledge, preferences, and interests beyond the classroom. The theme or topic of a lesson or unit was usually chosen by the teacher and largely driven by a narrative and the skill conventions of the particular art form. A wealth of rich contexts were used to explore the Arts in classrooms such as: school camp experiences; the kiwi icon of fish and chips; re-enactment of Jack in the Beanstalk, Maui Catches the Sun, and The Three Little Pigs; winter weather; storms; The Gruffalo; a Waitomo caves trip; field trips to dairy farms; and bush walks. Children’s meaning making seemed to be enhanced by contexts that were familiar to them, as well as appealing. Sometimes children brought their particular cultural expressions, images from popular media, or Arts knowing to their lessons, such as known vernacular dance moves or musical sound motifs. When and if they did, it was often in incidental and marginal ways. For example, during Jack and the Beanstalk, when the giant is charging down the beanstalk after Jack, one of the young Mäori boys turned his charge into a haka with great gusto. These findings concur with Glover (2001) and Dogani (2004) who argued that stories and cues such as words are widely used to give structure to children’s musical work. However, they maintained that this appears to be an adult led phenomenon and, if given creative freedom, did not appear in children’s work in the early stages. Indeed, they argued that an over-emphasis by teachers on narrative may actually be stunting composition.

Aligned to this is the question of permission seeking for including personal content and discoveries; children sometimes shared creative ideas in the interviews that did not surface in the lessons. For instance, children in a dance interview revealed that they had a myriad of ideas that could be used as a means of developing their dance, but that they did not volunteer them within the class devising time, because they would not fit the theme, or the teacher might not like them.

The influence of policy, paradigms, school culture, and structures

A range of factors and related discourses shape and inform child and teacher understandings in the Arts. School programme structures and rationales effect the possibilities and limitations for development within arts experiences. Wider Arts discourse result in influential paradigms and historically preferred arts pedagogies (Efland, 2002, 2004; Eisner, 1972; Kerlavage, 1992; Price, 2005). These discourses influence policy and curriculum and the ways in which these influences are played out in classrooms is elaborated upon later in this report (see Multiple paradigms in art education and children’s imagery). Alongside resources and the teacher’s own voice, these ultimately manifest within the choices teachers make when constructing programmes. For generalist teachers in particular, the initial case studies revealed some dominant discourses that underpin teaching in the Arts; the Arts are usually driven by linguistic and narrative ways of knowing and apart from visual art, are usually taught in groups. The teacher and university researchers were open to further examining these assumptions.

Primary children’s development of ideas in the Arts is a neglected fields-based research niche, both nationally and internationally. This project helps to address this gap and, in doing so, promotes ways of knowing that fall outside most studies in classrooms. Gardner (1983, 1993) has successfully challenged traditional notions of intelligence, proposing that schools have long over-looked a range of intelligences that are undervalued and underserved. The dominant discourse surrounding what counts as knowledge in most educational institutions is the emphasis on literacy and numeracy. Other ways of thinking are often marginalised, such as the visual/spatial, the musical and the bodily kinaesthetic; these ways of thinking are emphasised in the Arts. Williams (2004) and Claxton (1997) pointed out that intuitive intelligence is similarly undervalued. Williams suggested that visual intelligence is the primary intuitive intelligence used to make sense of our world. This study challenges the existing dominant discourse to raise the status of that which may be overlooked in traditional “measures” of school success. Valuing Arts-related intelligences effectively reduces the inequality of a system that privileges the linguistic and the logical-mathematical.

A project such as this is inevitably influenced by the culture and philosophy of the school in which the teachers work, a finding which is evident in the wider literature on school-based research and teacher change. Interest and support by colleagues and school leaders makes an obvious difference when it comes to a) advocacy for the Arts and b) support for the research project. Research indicates that the principal has a critical influence on the success of curriculum implementation (Ministry of Education, 2006b) and a similar claim can be made in regards to our research. Those teacher–researchers who felt supported by their school found much greater interest in what they were doing and greater value placed on research. Those who did not experience the same levels of support found it rather isolating and lonely at times. They spoke of the crucial importance of having: ongoing collaboration with the Arts project team; the regular visits of the university-researcher; and the generative nature of discussions at the roundtables. For all project members these aspects made a key difference for cohesion, momentum, and progress, both professionally and psychologically.

Aligned to school culture and philosophy is the way in which schools structure learning opportunities. This project comprised schools with very different approaches to teaching the Arts from: eight week elective blocks where children were drawn from numerous classrooms; to formal structured whole-class lessons led by the teacher; to programmes fostering a “community of learning” approach that encouraged peer teaching and seldom saw children working on the same thing at any stage of the day. The variations from school to school were marked and effected the ways in which the Arts were taught, learnt, and assessed. In contrast to Holland and O’Connor (2004) who claimed that the Arts provide co-constructed learning environments in which teachers and children learn from each other, this project found that the culture of the school and the philosophy of the teacher were the factors that influenced how the Arts were taught. The Arts as disciplines do not dictate the pedagogical approaches teachers will employ. (Neelands, 2004, for example, noted that it is not drama but what we do with it that makes it efficacious.) Rather, teachers develop distinct pedagogical content knowledge, and this, along with the particular culture of each school, influences how the Arts are interpreted and experienced by children.

From a sociocultural perspective, learning and teaching in classrooms can be considered a dynamic, participatory process that occurs and is influenced by the personal, the interpersonal, and the institutional (Rogoff, 2003). These three “lenses” are mutually responsive and cannot be neatly separated (Sewell, 2006). In other words, studying children’s learning in the Arts cannot be severed from the social and cultural context in which that learning takes place. Those classrooms that foster a community of learning convey a seamless and dynamic relationship between teacher, learners, and the Arts media they are working with. Moreover, the social and cultural context in which learning takes place, both transforms, and is transformed by, the way in which people interact and participate within that context.

Enhancing children’s learning in the Arts

For me the initial delight is in remembering something I didn’t know I knew.

Robert Frost

The final two research questions aimed to examine what enhanced children’s development of ideas and related skills in and through the Arts disciplines. A number of findings surfaced in the project which are identified below. As a result of the identification of a range of rituals of practice, or taken-for-granted assumptions and approaches, the teachers set themselves challenges through their action research questions to trial some different ways of teaching, aimed at enhancing children’s learning. The following questions (listed earlier under methods) were refined through discussion between teacher- and university-researchers and helped to frame the investigations:

- What effect does nonverbal feedback and feedforward have on the exploration and development of ideas in dance?

- What effect does children working as individuals, and as pairs, have on the development and refinement of ideas in music?

- What is the impact of symbolic representation on the development and refinement of children’s ideas in music?

- How are students currently exploring, generating, and developing their ideas in the visual arts? What supports or constrains students’ self-directed imagery using learned skills and strategies?

- What is the influence of teacher-in-role on children developing and refining their ideas in drama? In what ways can teacher-in-role contribute to deepening the drama and children’s ownership of ideas in drama?

Each of these questions formed the action research phase of the project and enabled teacher–researchers to trial some interventions in their classrooms. These interventions were trialled and refined through the cycle of reflection, planning, implementing, evaluating, and subsequent retrialling, taking into account what was gained from the first cycle (Kemmis & McTaggart, 2000; Mills, 2003). Findings from these action research cycles are reported and discussed to follow.

Using nonverbal ways of knowing to teach and learn in the Arts

When I have talked for an hour I feel lousy-

Not so when I have danced for an hour:

The dancers inherit the party

While the talkers wear themselves out and Sit in corners alone, and glower.

Ian Hamilton Finlay

The initial case studies revealed that teachers relied mostly on spoken, and to a lesser extent, written language to convey to children key ideas, sequences, and lesson moves. This reliance on the linguistic was a feature of all classrooms and a predominant mode of operating in one room in particular. While there were advantages in using talk to direct process and dialogue to check understanding, there was a tendency towards question-answer patterns of communication from teacher to children in a relatively uni-directional fashion (a common and well documented phenomenon, see e.g., McGee, 2001; Sewell, 2006). In contrast, the fostering of a “community of learners”, wherein discussion ranged more broadly between children, their peers, and the teacher was noticeable in one classroom in particular. In this class, the whole school emphasised a philosophy of peer teaching and negotiation of learning alongside self-direction.

As a result of the initial case study, and the viewing of her teaching on video, one of the teacher–researchers recognised the ways in which her talk tended to dominate what occurred in dance lessons. Thus, her verbal language had supremacy over the movement of dance. Through discussion with her university colleagues, she set herself the challenge of incorporating more dance gestures and movements to provide increased nonverbal guidance in dance. This did not mean that she did not speak at all, but rather, that she consciously built in specific dance ways of communicating (gestures, movements, bodily expressions) within feedback stages of the lessons. She initially gave feedback on aspects she liked through a danced reflection to her class and using nonverbal moves which she checked verbally, to see if they had understood what she was communicating to them. When the children accurately interpreted the nonverbal message the teacher–researcher felt encouraged by her innovation. After three demonstrations of nonverbal dance feedback, a child in the class asked if he could give nonverbal feedback to his peers. The teacher–researcher quickly agreed that this was a great idea and watched with interest as the children developed their own dance feedback responses. Periodically, she would check in verbally with groups to gauge whether they had understood what their peers were communicating to them (e.g., “What was the person telling you?”) and she assisted with clarifying any confusions or mixed messages. Her “checks” were to confirm children’s understanding rather than to provide verbal explanations. She was surprised to find though, that quite a lot of their communication was clearly conveyed and received.

The teacher–researcher noted that the more confident children used dance moves to communicate their ideas and the less confident used mime. Both forms of nonverbal communication were accepted and encouraged. Over time, however, more children incorporated dance rather than mime, as their skills and confidence grew. She also noted that using dance movements as feedback was easily understood by the children as well as inclusive. For example, children who had English as an additional language were not disadvantaged by nonverbal feedback to the same extent as the giving and receiving of the verbal. When interviewed about the innovation, children commented that, “I like it because I could see what my dance looked like [to someone else]” and “I found it better than being told because it was a surprise.” Moreover, the degree of dance participation time was arguably increased as children kept working on and using their movement repertoire rather than having to anticipate what they were going to say verbally.

Once the children became au fait with giving and receiving nonverbal feedback in dance, the teacher–researcher wanted to extend the process to the giving of suggestions for improvement or “feedforward”. This formed the basis of the next cycle of action research with her class. The lessons still featured some verbal discussion especially when recapping main ideas with the class, outlining changes groups had made to their dances, and refining ideas. The children volunteered dance pointers such as: the importance of using different levels in dance; the need to spread out to give group members room; and to vary individual moves amongst group or unison moves. As with the nonverbal feedback, nonverbal feedforward was offered by children to their peers and checks were made to ensure those receiving the suggestions were clear as to what was meant. It seemed that nonverbal communication required a sharper attention to the message by the children. This was implied by their stillness, lack of fidgeting, and absorbed silence while watching their peers. It was also evidenced by their ability to verbally interpret and adopt or adapt what was conveyed. As a result of these trials, nonverbal peer feedback, and feedforward through dance became a regular part of the dance lessons with the class buying into the culture of nonverbal communication. The children also considered the timing of giving feedback and feedforward by sharing during lessons when groups specifically asked for it, and not just at the end, so that ideas could be developed further in class. Moreover, the children often danced their responses to the feedback and feedforward, creating an intriguing nonverbal dialogue.

Put simply, dance is a nonverbal domain. Bannon and Sanderson (2000) explained that “dance offers a distinct form of communication separate from the expressive statement of direct speech” (p. 16). While some have argued that verbal language is necessary for working in the medium of movement, Bannon and Sanderson (2000) questioned whether it is appropriate to assume that dance experiences can be translated into verbal language in any authentic sense. And while dance researchers agree that reflection and feedback are important in order to inform future action (Chen, 2001; Cone & Cone, 2005; East, 2005; Gibbons, 2004; Lavendar, 1996; Lavendar & Predock-Linnell, 2001), there is little documented evidence related to nonverbal gesture or movement being used as a means of feedback in dance. It also appears that the nature of verbal feedback given in dance can be problematic. Williams (2002) found that teachers when giving dance feedback tend to leave little room for student voice to contribute to the conversation and that the subjective nature of criticism can lead to defensiveness over perceived personal attacks. In addition, Gough (1999) warned against feedback being an activity that only occurs at the conclusion of class.

Lavendar (1996) developed structured approaches to developing critical reflection in dance which included strategies for fostering both objective and subjective feedback. However, the emphasis is on oral and written practices. The case study findings in this project corroborate that verbal language tends to dominate and have supremacy over the use of movement as a communicative medium.

Patterns of verbal interaction in classrooms and the ways in which discussion can influence learning have long been the subject of study. For example, Barnes and Todd’s (1977) seminal study provided some of the best examples of socially constructed knowledge in the research literature and many others have carefully scrutinised verbal dynamics in classroom interaction (e.g., Cazden, 1988; Good & Brophy, 2000; McGee, 2001; Mercer, 1995; Nuthall, 2001). Rather than add to an already extensive literature on this topic, this study offers a contrasting and equally important view on how ideas are constructed and communicated in classrooms. Instead of privileging the linguistic (see earlier under The influence of policy, school culture, and structure), the Arts offer multiple opportunities for learning in and through the unique, largely nonverbal languages of the Arts: through music, dance, drama, and visual art. Arguably, drama is the most ‘verbal’ of these art forms given the speech aspects of teacher-in-role, hot-seating, spoken thoughts, and the like. However, all four art forms are rich in nonverbal ways of communicating, such as gesture, shape, movement, sound, rhythm, tone, pitch, colour, use of space, layering, texture, position, levels, facial expression, body language, perspective, and many more.

It is well established that children make sense of new knowledge in the light of their existing ideas and experiences. However, the claim is often asserted that “essential to this process is language, since talk aids the organization of experience into thought” (emphasis added, Bennett, 1994, p. 63). This assumption about the centrality of talk underpins much of the work in social constructivism wherein knowledge is jointly constructed through dialogue in social contexts. It is important, though, to interpret dialogue broadly, as not just talk but as communication in all its varied forms (Shields & Edwards, 2005). And the Arts provide a wealth of communicative forms, many of which are nonverbal.

Each art form has a rich nonverbal way of knowing that enables the learner to express things in ways that words cannot, or in ways where words are not adequate. Smith-Autard (1994) argued that “not only are there never adequate words, but there is a tendency not to notice that for which we have no language” (p. 32). When we do notice the nonverbal, this gives children the freedom to explore in ways not driven by linguistic structures. We can speculate that removing the emphasis on “talk” was enabling for children as they had no need to convert actions into words for feedback purposes but could stay in the medium of expression. Using the ways of knowing of the Arts helps to build capacity and greater fluency in the Arts as children become more confident and knowledgeable about how the Arts convey meanings and nuances. This assumes, however, that teachers appreciate the value and subtlety of each art form as a discipline in itself and not purely as a set of skills to master and tasks to complete. It also calls into question the amount of talk that teachers use to convey Arts concepts and ideas. Similarly, this finding suggests that asking children to explain what they are doing or attempting to achieve can be limiting and even misleading. It can be more instructive and fruitful for teachers to ask children to “show me”, rather than “tell me”, about your dance, drama, or music.

By attending to the Arts through the nonverbal, we extend and enhance sensory awareness. Eisner (2000) argued:

… learning to see and hear is precisely what the arts teach; they teach children the art, not of looking, but also of seeing, not only of listening, but also of hearing. They invite students to explore the auditory contours of a musical performance, the movements of a modern dance, the proportions of an architectural from so that they can be experienced as art forms. Seeing in such situations is slowed down and put in the service of feeling. (p. 9)

This attention to the Arts through nonverbal means, heightens perception beyond the linguistic. And for many children, their expression in the Arts outstrips their verbal abilities. They are able to “show” stories, convey feelings, capture moments, compose images and sounds that have expressive power in their own right. The Arts enable those children for whom English is an additional language to participate fully alongside their peers, as long as spoken and written language does not dominate how the Arts are conveyed and interpreted. Moreover, teachers often report surprise at the abilities a range of children reveal in dance. Dance (along with the other art forms) can be a place where teachers see their children in new ways. The Arts do not exclusively rely upon fluency with literacy or numeracy and, therefore, in many ways, it could be argued that the potential for inclusive pedagogy is thereby enhanced.

However, it is not enough to recognise the inclusive potential of the Arts. The ways of knowing that the Arts encapsulate need to be valued and explicitly taught. This includes the processes by which children learn to see, hear, feel, touch, move, express, and gesture. This is not to say that the reception of Arts forms should not, at times, lead to rich verbal dialogue. Interpretive dialogues are further opportunities for children to share their own unique views and construct understanding of the richness of what the Arts offer.

Individuals, pairs, and groups

I walked abroad in a snowy day;

I asked the soft snow with me to play;

She played and she melted in all her prime,

And the winter called it a dreadful crime.

William Blake

Nuthall (2001) found that children:

… already know at least 40–50% of what teachers intend for them to learn. Consequently they spend a lot of time in activities that relate to what they already know and can do. But this prior knowledge is specific to individual students and the teacher cannot assume that more than a tiny fraction is common to the class as a whole. (p. 11)

He went on to argue that the sheer numbers of children in any one class means that teachers tend to focus on teaching the whole class (a feature encouraged in the United Kingdom in recent education policy) and only focus on individuals for brief periods of time. The other common structure or ritual employed by teachers is the use of groups, and this helps teachers to again manage the numbers of children in their classes. The use of “ability” groups is intended to help teachers target particular needs of children clustered around similar levels of attainment.

In order to find out what individual five-year-olds brought to music, one teacher–researcher decided to explore what happened to children’s idea development when they worked as individuals or as pairs, rather than as larger groups or the whole class. Her motivation for this focus was kindled by the initial case study which revealed mostly whole class and group teaching. In music, this can be a convenient management structure, especially when dealing with the sonic properties of music. As a class, and as groups, the children can be instructed to play, and then to cease, so that the sound is controlled and not overwhelming. However, a child’s ability to hear the actual sound he or she is making in such settings is difficult when surrounded by others also making sound. This is certainly lessened by individual and pair work. The challenge remains, however, of providing sufficient space for children to work musically alone or in pairs, without disturbing everyone else.

Another reason for exploring individual and pair work was that within groups, one child tended to dominate the idea generation and dictate to others what to do. The ability (or inability) to negotiate, rather than the quality of musical idea generation, seemed to dominate what happened in groups. As this Arts project was not focused on group work per se, it was beyond the scope of the study to address these dynamics.

As a regular ritual of practice, the teacher–researcher provided a music table in the classroom on which were a variety of objects and instruments for making sound. Her class of five-year-olds were invited informally to “play” at the table before school if they wanted to. To capture this activity, a video camera was set up in the corner (all consents from children and parents were sought in advance). The teacher did not intervene during this free time and went about her usual before school tasks in preparation for the day. A number of children took up the invitation and began experimenting at the table. After an initial play with various objects, each child seemed to settle on an instrument or object to use for sound making and played with gusto.

On viewing the video afterwards, the teacher- and university-researchers observed a number of things. Noteworthy was the fact that the children brought more musical prior knowledge, absorption, and gusto than was first assumed, and more than had been detected or developed during the regular class music programme. Obviously, their technical mastery of instruments influenced their creative music making possibilities, and some were more adept than others. What was noticeable was the skill some did have (e.g., a boy drumming like a band member; the subtle ensemble awareness of some children even when doing their own thing; the nonverbal interchanges; fascination with beat and simple rhythm patterns; recall of known song motifs; and the exploration of pitch). There also appeared to be considerable sensory pleasure in the generation of distinct movements arising from music making, as much as their interest in the sound they produced. The kinaesthetic and auditory were closely linked, and, in addition, there appeared to be pleasure in repeating favoured sounds and moves which was given free rein in the context of the informal setting (Burnard,1999; Glover, 2001; Swanwick & Tillman,1986).

Teachers often complain about the lack of time in the school day to “fit in” all that needs to be covered. This simple intervention is a useful way for children to have valuable exploration time; time which is often constrained in the regular class programme. Teaching can easily be dominated by measurable outputs and scaffolded learning which can result in the neglect of the vital incubatory play/improvisation that is needed in creative process. Such exploration is inevitably noisy, takes up space and invariably looks like nothing is happening. To many teachers it may seem like an indulgence that can be eliminated. However, such freedom for idea and technical experimentation is a critical foundation for idea development in the Arts and demands place and space within Arts teaching. It is also supported by the emphasis on exploration in the Arts curriculum document (Ministry of Education, 1999).

In the second cycle of research, the focus moved to children working individually and in pairs. The teacher–researcher was fortunate to work adjacent to a hall space which was convenient for this initiative. Obviously, there are safety issues involved if young children are working alone, so the adjacent space with a shared door into the classroom enabled the teacher to be in close proximity.

As with the music table, individuals spent time exploring sounds and the properties of their chosen instruments. However, they lost interest and momentum more quickly than at the table surrounded by peers. Significantly, individuals often tried to play more than one instrument at once, signalling a preference for sonic layers. This is of course more easily managed by pairs or small groups. When they worked with a partner though, they persisted for longer, imitated each other’s musical ideas, made subtle adaptations while playing in parallel, and showed some ensemble awareness. However, one child in a pair tended to just follow what the other child did, but at times added his or her own innovations and variations. One pair not only played their instruments together, but also sequenced several sounds together, layering these. Movement seemed integral to the experimental process and several pairs set off around the room dancing as they played. The physical properties of the instruments tended to influence the musical outcome: drums resulted in pattern and beat; glockenspiels resulted in glissando slides and notes sequenced together. Predictably, bells were shaken.

Significantly, pairs and individuals recalled rhythmic patterns and repeated these unprompted. These sound motifs appeared to be part of their sonic repertoire; their personal vernacular. Little is known about what makes pair work effective. Some argue that each child in a pair provides opportunity for mutual growth; some claim that there is more equality in the relationship compared with larger groups (Kutnick & Rogers, 1994); and others state that pairs encourage persistence (Fraser, 1998). Certainly, the smaller the group the less argument there tends to be about whose turn is it and who has access to what resources (Fraser, 1998; Kutnick & Rogers, 1994).

These observations highlighted what children bring to learning and how useful it can be to give them the time and uninterrupted opportunity to explore sonic properties and the feel of their instruments. Free exploration at a music table appears to foster young children’s interest, as does playing music with a partner. This is not to suggest that other approaches to music are not valid and nor to suggest that pairs are invariably “better”. Rather, this cycle highlighted what individual children could do musically which can get obscured in whole class and large group teaching. There are limits to adults viewing children’s creative outcomes through adult lenses of supposed best Arts “practice”, which has an influence on what is valued in creative production (Glover, 2001; Lavendar, 1996) .This in turn, can blinker us to what children are really doing and can distort our perspective as to what children intuitively bring to a creative activity.

The initial case studies revealed that set group work is an accepted ritual of practice in dance, music and drama creative work in primary classrooms, arguably for pragmatic and management reasons, rather than for pedagogical reasons. Some of the group work clearly helps children to grow ideas and negotiate various aspects of their Arts making, especially as a solo or paired context may limit the range of combinations, contrasts, and variations that can be achieved in a work. For instance, for ideas to be developed or “realised” in music, layers of instruments may be required which demands group input if presented live. What we are less clear on is what is the best use of group work in the classroom creative process and whether group work should be unchallenged practice.

The findings show that group dynamics effect the idea development pathway and creative outcome as of necessity, it requires compromise. This means that individual idea generation and development may be thwarted by the collective power of the group. One questions whether group work is necessarily the only way for children to develop their music ideas, as it takes a level of skill to verbally and nonverbally negotiate a desired group outcome (Kutnik & Rogers, 1994; Ota, 2006). The purpose for using group work needs to be considered carefully, for the social skills required may over-shadow the desire for a quality, creative outcome.

It was interesting that dynamic difficulties became less obvious in dance and music. specifically when groups were improvising with minimal verbal interaction. Within this generative mode, where imitation and building off others’ ideas as an ensemble dominated, creative flow appeared more productive. Conversely, we frequently saw productivity stymied and offers blocked when verbal interaction dominated the idea generation.

Aligned with this, group work may also influence the quality of creative idea development and imaginative possibility thinking of which an individual child is capable, and may be particularly damaging for the highly creative child. It is likely that there are times when the skills an individual brings may far outstrip those of the group and the child concerned may have to dumb down their skills to match. Such children deserve opportunities for full extension in music classes and it is debatable whether, as a ritual of practice, mixed-ability group work necessarily allows for this. It could be argued that the group should merely be a mechanism by which music ideas, generated by an individual or pair, can be “realised” or arranged for performance. Nankivell (cited in Glover, 2001) suggested that in music composition, invention of ideas is often individual, whereas the group is used for arranging and sonically realising ideas.

If Arts teachers are to foster creative idea-generation and development in groups, unchallenged rituals of practice may need to be changed to accommodate such things as: the manner in which groupings are contrived; the mechanics of giving and receiving offers and what may block offers; and the purpose for the use of group work in the first instance.

The strengths and limits of symbolic representation

If music be the food of love, play on.

William Shakespeare

This action-research phase centred on how Years 5 and 6 children might adopt, or invent symbol systems to code sound events in a sound scape and how they might develop and refine their ideas using these. A sound scape is defined as a piece of music, which sonically captures an event, image, mood, poem, or narrative of some kind. In other words, the children were expected to evocatively “paint” with sound. The research question arose from an earlier block of creative music making based around a theme, where in both process and product, the teacher–researcher felt that the children had not developed their work to the full. She had a hunch that the use of symbolic representation might aid the process of development and refinement.

The motivational context for the sound scape was “winter weather”, a theme carefully selected by the teacher–researcher in the aspiration that all children would have some experiential knowledge to bring to the compositional process. The teacher was working on the premise that productive generation and development of sound ideas is best embedded within children’s world of knowing, a position substantiated by Efland (2002) who maintained that learning is most meaningful and lasting when related to a person’s life-world.

There had been extensive class discussion related to winter weather, the sound events that this theme might evoke, and the qualities of sound embedded within these .The class explored, shared and reflected on related sounds using conventional, untuned percussion and environmental sounds. As a means of recording their work, symbols were also introduced and examples of graphic notation (icons to represent variations in sound such as wavy lines and swirls) and conventional musical notation were explored. They became aware that symbols could be used: to indicate the structure of the piece; to start and stop; to add dynamic variations; contour or pitch differences; duration (length of sounds); and layers sound (texture). Conventional notation, such as bars and bar lines, and rhythmic notation symbols, were also introduced.

Groups were then given time to develop a sound scape representing a weather condition. Honouring the enactive mode of experimenting with sound, the focus group collaboratively generated their sound ideas through repeated nonverbal improvisations showing heightened ensemble awareness of visual/body cues and listening acuity .These improvisations were interspersed with verbal discussion and at times, heated debate, and negotiation. The devising process and musical output was arguably compromised at times by some unresolved group dynamic issues. After numerous improvisations, they notated their work on a large sheet of paper, overlaying and attaching additional strips as they made alterations to any line as they selected and rejected efforts.

We used skill theory as a means of looking at the detail of their sound scape. Skill theory characterises cognitive development as the skill of regulating or co-ordinating one, two, or two sets of two dimensions of a task within a domain. Developmentally, children as young as 4 or 5 years of age can map discrete musical events within a phrase and by 7 they can map two relational dimensions in a phrase such as pitch and rhythm (Davidson & Scripp, 1989).

The focus group’s (a group of five children of mixed ability and ethnicity) work clearly showed that they could manage at least two relational dimensions at once. They represented: how the sounds were to be played by their symbols (such as strokes or swirls); indicated how often these occurred (e.g., spaced out or close together); and how long they were to continue. At the same time, they showed they were aware of dynamic variation, adjusting the size of the symbols to indicate louder or softer. There was little effort to show pitch variation; rather, their agenda seemed to be sound quality.

Their score showed where they individually started and stopped and also that different lines of the score represented different sound sources, or people playing. In fact, each line sometimes had multiple layers indicating that a child was playing more than one instrument during the piece. However, the score showed no cognisance of the interrelationship in temporal nature of each line operating on the score. That is, each child wrote their own line and where they started or stopped did not necessarily match with the actual, sonic events in other lines. This inability to decentre from the self when writing their cues is interesting given that developmentally, 9–10-year-olds are generally less egocentric. However, they became aware of this when it was pointed out:

| Researcher: | Your symbols show you do not play with the others at the end .Is this what you actually do? | |

| Child: | I do drips … I would make it longer so I finished with Tara’s rainbow sound. |

It seemed as if the child only became aware of this score/sound mismatch when discussing the score.