Introduction

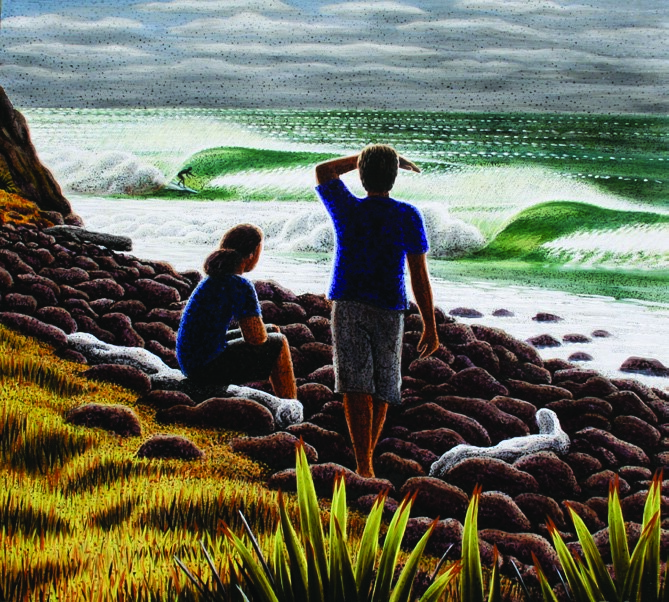

We can think of changes in the international literacy landscape as a powerful wave. It has reached our shores here in New Zealand; there is no escaping it. In this report, we argue that given the changes affecting our classrooms through information and communications technology, and increasing student diversity not only do we want to prepare ourselves for the wave, but we wish to harness its power.

This “wave” involves a reconceptualisation of literacy, known as “multiliteracies”, that takes account of an increasing cultural and linguistic diversity and rapid changes in communication technologies. our research project sought to address the paucity of research on multiliteracies in New Zealand, building on a growing body of international literature on multiliteracies.

Key findings

In order for educators to harness the wave of multiliteracies, we found:

- That they need to reconceptualise literacy and literacy practices; and,

- Rethink pedagogy.

As we will see in the upcoming findings section, these findings present a number of challenges for teachers.

Background

In 1996, a group of leading literacy researchers from the United States, United Kingdom, and Australia coined the term “multiliteracies” (The New London Group, 1996). They proposed a reconceptualisation of literacy that attended to increased cultural and linguistic diversity due to changes in migration in the context of a global economy. also, it took into account the rapid changes in communication technologies that have resulted in wider access to multimodal texts; that is, texts that draw not only upon linguistic codes and conventions, but also visual, audio, gestural and spatial modes of meaning (see figure 1) (Cope & Kalantzis, 2006, 2009; The new London group, 1996). Reconsidering literacy as multiliteracies encourages us to shift our thinking about literacy acquisition from a global mental process acquired according to a developmental, hierarchical timeline to a conceptualisation of literacy as “a repertoire of changing practices for communicating purposefully in multiple social and cultural contexts” (Mills, 2010, p. 247). In short, a multiliteracies view encourages us to broaden our understandings of literacy.

Yet current resources used by New Zealand teachers define literacy as “the ability to understand, respond to, and use those forms of written language that are required by society and valued by individuals and communities” (Ministry of Education, 2003, p. 13, emphasis added). This conceptualisation of literacy omits a future focus (Limbrick & Aikman, 2008) and potentially limits approaches to literacy instruction, which frequently resemble the traditional approaches used by generations of New Zealand teachers. Consequently, teachers tend to largely focus on supporting students to make sense of written texts (Ministry of Education, 2005). When using traditional approaches to literacy instruction, teachers are less likely to encourage students to critically analyse texts (Sandretto with Klenner, 2011), engage with a wide variety of text types (Sandretto & Critical literacy Research Team, 2008), make use of the experiences students bring with them to school (McDowall, Cameron, Dinglewith, Gilmore, & Macgibbon, 2007) or capitalise on students’ ever-increasing out-of-school literacy practices (Hull & Schultz, 2001).

In contrast, a multiliteracies perspective supports students to decode, make meaning, use and critically analyse multiple text types for multiple purposes in diverse contexts (Luke & Freebody, 1999). This framework is known as the four resources model and can be applied across all texts in all curriculum areas (Healy & Honan, 2004). In figure 1, we see that the five semiotic systems form the focus for decoding. The critical analysis component of multiliteracies is known as critical literacy and is considered to be an important aspect of multiliteracies (Anstey & Bull, 2006; Sandretto with Klenner, 2011).

| Code breaking Essentially, how do I crack the code of this text? |

Semiotic systemsLinguistic: oral and written language (vocabulary, generic structure, punctuation, grammar, paragraphing). Visual: Still and moving images (colour, vectors, line, foreground, viewpoint). Gestural: facial expressions and body language (movement, speed, stillness, body position). Audio: Music and sound effects (volume, pitch, rhythm, silence, pause). Spatial: layout and organisation of objects and space (proximity, direction, position in space). |

| Meaning making Essentially, what does this text mean to me? |

|

| Text user Essentially, what do I do to use this text purposefully? |

|

| Text analyst Essentially, how might I be shaped through engagement with this text? |

Source: Bull, G., & Anstey, M. (2010). Evolving pedagogies: Reading and writing in a multimodal world. Carlton, Vic: Curriculum Press. (pp. 10, 19)

In addition, from a multiliteracies perspective, it is vital to bridge the literacies students use out of school with the literacies they use in school. Students’ out-of-school literacies are shaped by the “funds of knowledge” developed in the social spaces of home, peer groups, communities and popular culture (Moje et al., 2004; Moll, Amanti, Neff, & Gonzalez, 1992). Moll (1992) and his colleagues argue that “strategic connections” (p. 132) between home and school are essential to develop pedagogy that is more relevant and engaging for our students.

In response to a growing demand to revise literacy policy and resources, the Ministry of Education formed the multiliteracies working group to consider the influence of information and communication technologies on literacy (Jones, 2009; Moje et al., 2004). The group drafted a framework for multiliteracies acquisition which took a multiliteracies lens to the four resources model (Luke & Freebody, 1999) of learning the code, making meaning, using texts, and analysing texts. The group signalled a need to augment current literacy practice and policy:

The working group concluded that we need to expand on current practice models to take account of the need for young people to develop a range of social, creative, ethical and cultural practices to make meaning in a technology rich and culturally diverse world. (p. 1)

Unfortunately the findings of this group did not come to fruition. This was a missed opportunity for New Zealand literacy policy.

This TLRI research project, “Critical Multiliteracies for ‘New Times’”, was developed to conduct forward-looking research and honour the findings of the multiliteracies working group. The phrase “new times” has been placed in quotation marks to highlight the idea that the times we find ourselves in are not all that new. writers have been considering the effect of globalisation on education for some time now (Gee, Hull, & Lankshear, 1996; Gilbert, 2005; Moje et al., 2004). The research project sought to address the paucity of research on multiliteracies in New Zealand and drew upon previous TLRI research into critical literacy (Sandretto & Critical Literacy Research Team, 2006, 2008; Sandretto et al., 2006; Sandretto with Klenner, 2011).

The project built on a growing body of literature on multiliteracies in Australia (Bulfin & North, 2007; Mills, 2006; Walsh, 2006), Canada (Cummins, 2006; McClay, 2006; Peterson, Botelho, Jang, & Kerekes, 2007), the United States (Lewis & Fabos, 2000, 2005; Minarik, 2000) and the United Kingdom (El Refaie, 2009; Kress, 2003; Millard, 2006).

The project investigated the main research question:

“How can teachers bridge students’ in- and out-of-school literacies to enhance their critical analysis of multiple types of texts (e.g., books, films, websites, videos) in order to prepare them for a ultiliterate future?”

It also investigated the subquestions:

- What are the literacy practices of students in- and out-of-school?

- How does the range of modes and media embedded within contemporary communication landscapes shape these practices?

- How do students make sense of their developing multiliteracies?

- How do teachers use knowledge of students’ in- and out-of-school literacy practices to work alongside students in the classroom? In the remainder of this report, we discuss the research design, findings, major implications and limitations.

Research Design

The research design for the project built on the successful design of two previous TLRI projects into critical literacy (Sandretto & Critical literacy Research Team, 2008; Sandretto et al., 2006). Over the course of the 2-year project, 19 teachers and their students from seven schools participated. The schools included full primary schools, two intermediates and a college, and included rural and urban sites. Some schools were able to send teachers successive years and other schools sent a pair or small group of teachers any given year. This design supported the participating teachers to form a community of practice and to build capacity and capability around critical multiliteracies (Lave & Wenger, 1991) within and across the participating schools.

All of the students of each participating teacher were involved in whole-class lessons, and five students from each class were involved as researchers examining their own multiliteracies. These same five students were also involved in focus group interviews after each videotaped lesson.

The participating teachers:

- Took part in nine release days over the year (including two research hui)

- Conducted an ethnography of the in- and out-of-school literacy practices of one of their students, and shared these findings at a research hui with other participating teachers, principals and the researchers

- had two literacy lessons videotaped

- Conducted and participated in an initial and exit interview with other participating teachers

- Took part in an end-of-year research hui with students, principals and the researchers.

The participating students:

- Conducted a study into their multiliteracies, constructed a poster to share their research findings, and took part in an end-of-year research hui with teachers, principals and the researchers

- participated in two focus group interviews with the researchers after videotaped lessons and one exit interview conducted by participating teachers.

Data analysis began early in the project and still continues. each successive round of data gathering informed the next. The research team working days allowed time for reflection and further analysis to inform the development of multiliteracies pedagogies. a great deal of data was collected. for each year over the two years we collected:

- Initial and exit interviews with the participating teachers (ii and ei)[2]

- student focus group interviews (FGI) after each videotaped lesson and at the end of the year

- Teacher powerpoint presentations and audiotaped presentations of the results of the ethnography into the in- and out-of-school literacy practices of one student (research hui/RH)

- student posters (p) presenting their findings of their autoethnography of themselves as multiliterate people

- student voice templates (SVT) after each collaborative analysis of videotaped lessons where the participating teachers reflected on the feedback from the student focus group interviews and suggested ways they wished to change their practice

- follow-up interviews with participating teachers from 2011 during 2012[3] (y2i) to investigate the sustainability of the research findings

- Transcripts from audiotaped research team working day discussions (RTWD).

To develop the findings in this report, each researcher coded one set of data across all of the sources for one year. evidence from the transcripts was located in a shared word document against the themes that each researcher added as they analysed the data. The framework learning from students, learning from teachers, learning about students, and learning about teachers was used to organise the themes. Then each researcher moderated one data set from the other year against the themes document. The researchers did not find any discrepancies in their coding. The critical sociocultural framework (Moje & Lewis, 2007), the research literature, the research team working day discussions with the participating teachers and the input from the student researchers influenced the development of the themes and the selection of the key findings for this report.

Findings

The first challenge: Reconceptualise literacy and literacy practices

The primary challenge facing educators is the need to reconceptualise literacy and literacy practices in light of the “new times” described in the introduction. A key aim of the research was to support teachers to engage with the theories and practices of critical multiliteracies (Bull & Anstey, 2010; Sandretto with Klenner, 2011). The research design created extended spaces for the participating teachers to engage with the theories and practices of critical multiliteracies and to critically reflect on their literacy programmes and pedagogies. For example, one teacher commented during the presentation of the study of one student:

Investigating the individual student’s literacy habits has highlighted my own narrow viewpoint of what literacy actually is. It has enlightened me to the changing nature of literacy for children in today’s world. It already has me thinking about what it actually translates to when I’m doing a guided reading activity, as in what is this going to allow the child to do? Am I using a range of texts or sources in my classroom? Are the children allowed time to analyse everyday texts, and do I use a context in my teaching that is actually relevant to the needs of my children today? I know that this was supposed to be research on one student, but it’s certainly given me a broader view, and I’ve sort of had to consider whether or not the contexts that I provide reading activities are actually valid at times and whether or not the child’s getting anything out of it, other than me saying “guided reading – tick” you know. So it’s certainly made me think about that. (RH, 2012, p. 5)[4]

Here we see the power of the research design where the teachers conducted an ethnography of the in- and out-of-school literacy practices of one student as a means to prompt critical reflection on their teaching practices. The participating teacher in the previous quotation refers to an increased awareness of the shifting literacy landscape, as well as how his classroom practices may have limited the opportunities for students to decode, make meaning, use and critically analyse a wide variety of texts.

Not only did the participating teachers have multiple opportunities to reconceptualise literacy and literacy practices, the participating students did as well. For instance:

Interviewer: What did you learn about yourself as a multiliterate person this year?

Student 2: It means communication.

Student 3: Your mind’s like communicating with lots of different things, like reading and people.

Student 4: It’s like everyday things we use as texts…and like all the semiotic systems and communication and stuff. (FGI, 2012, pp. 1–2).

Here the students explain that their understandings of literacy are now focused on communication using a wider range of texts with attention to the ways that the semiotic systems and different types of texts are used to communicate, rather than solely an emphasis on traditional reading and writing.

A corollary of reconceptualising literacy and literacy practices is the need to reconceptualise what counts as a text. We are advocating that teachers and students develop a metatextual awareness (Unsworth, 2006). In other words, an understanding about texts, their varieties, how they are constructed and their potential affordances. for example:

Yeah, and I think that has been one of the big learning curves for us actually, that when we came in, I think we probably thought of text as a traditional text, maybe we might have extended that to oral language and visual language but really just the fact that it is all text and really everything involves a text of some type. (EI, 2011, p. 2)

In this exit interview, the participating teacher is able to point to the ways in which the project supported her to broaden her understanding of what counts as a text.

The students also shifted their conceptualisations of what counts as a text:

Interviewer: Has it made you think about texts differently?

Student 2: It makes us think like there’s all different ways to communicate to other people. Instead of just talking you can point, use your hands, you can nod, use your face, use your hands . . .

Student 3: At first I thought it was just writing and all that (FGI, 19/06/2012, p.5).

In this focus group interview, the students articulate that their participation in the project has expanded their understandings of what counts as a text. Their understanding has moved beyond a traditional linguistic text to an understanding that they can construct a text using any of the semiotic systems that are available to communicate their message. In another focus group interview, a student explained that as a result of participation in the project:

You . . . definitely notice a lot more of the all of the texts and affordances that you’re using from this. Because you kind of notice more of what you do in a day. you’re normally just noticing about the main thing . . . [for instance] like walking the dog that’s all really you’re thinking about. not really, like, are you socialising . . . or use [the] visual [semiotic system] and . . . you don’t really notice them . . . but now. (FGI, 5/12/11, pp. 2–3)

Here we can see that some students have taken up a broader understanding of what counts as a text. “A text is a vehicle through which individuals communicate with one another, using the codes and conventions of society” (Robinson & Robinson, 2003, p. 3). In this excerpt, the student demonstrates an understanding that there are codes and conventions involved even in walking the dog: keeping the dog on a leash, cleaning up after it, and so on.

And lastly, an integral aspect of reconceptualising literacy is the metalanguage that accompanies it. we found that teachers and students need multiple opportunities to engage with and adopt the metalanguage of critical multiliteracies. Students suggested that teachers need to explicitly teach and revisit the metalanguage of critical multiliteracies:

Student 4: Yeah um [you] do a different semiotic system each day, so one day visual, one day gestural like that . . . because it can get confusing all at once . . . When we got to it, we got to it all together and then we had to actually say them out and say what they meant and some of us had no clue because um, it was just like we had no idea.

Interviewer: Is that because you didn’t really understand the metalanguage?

Student 4: Well, I understood it but it was like too many things to remember. (FGI, 29/10/2012, p. 4).

Teachers echoed this sentiment:

Because they have got the language to talk about it as well, they can then actually start to um, explain it in more depth. (EI, 2011, p. 8)

The ultimate goal is for the students to take ownership of the metalanguage and use it independently:

Yeah but it’s rewarding to see that the children have actually continued to express themselves and use the same language even when the video camera’s not there. (Y2I, 2012, p. 2)

Some students wished they had been introduced to the metalanguage earlier:

Well . . . when you’re younger, like, when you’re just coming into school I think you should learn about them, you’ll get a better understanding about them, because I managed multiliteracies in term one this year . . . That was quite a shock that I hadn’t heard of them ever before. (FGI, 29/10/2012, p. 4).

In their feedback to the researchers and participating teachers, the students signalled the usefulness of the metalanguage and suggested that students of all ages should have access to the language needed to understand and develop multiliterate practices.

Reconceptualising literacy includes reconceptualising what counts as a text and developing a metalanguage to talk about texts. Researchers working in the area of critical multiliteracies emphasise that “the field needs to shift from an emphasis on teaching reading, writing, spelling and grammar to one that offers more flexibility in the kinds of meaning-making that students do” (Mclean & Rowsell, 2013, p. 1). It is of great concern that here in New Zealand we do not seem to be aware that the global wave of multiliteracies has arrived on our shores and demands a shift in our literacy policies, pedagogies and practices. Authors such as Limbrick and Aiken (2008) in the New Zealand context also highlight the need to shift the ways we think about literacy in Aotearoa.

The second challenge: Rethink pedagogy

To shift teaching and learning to accommodate the wave of literacy change, we found that teachers need opportunities to rethink their literacy pedagogies, trial new pedagogies and reflect on the outcomes of those trials with the support of their students. There is no one right way to teach critical multiliteracies. We urge teachers to develop strategies that are appropriate for their contexts and their students. Nonetheless, we were able to gather a great deal of insight from the teachers and students’ reflections on literacy pedagogies.

After engaging with the transcript of a student focus group interview, one of the participating teachers reflected that he intended to shift his pedagogy in light of what the students were saying. He would:

Do more moving through the analysis stage into the applying, creating stage, aim to do a better job of covering the receptive and productive sides of literacy. (SVT, 28/09/11)

Here the teacher demonstrates an increased awareness to not only address the decoding and analysis of texts, but to also to provide students with opportunities to make texts. Another teacher reiterated the emphasis on student agency and creating texts:

Break systems down more, have students create more texts (ICT activities) as well as analyse. Ownership for the students, let them have more control over the direction of the lesson topics. (SVT, 2011)

A different teacher reflected on the ethnography of one student that she conducted in the first term during the research hui presentation:

So I looked at the students in my class, their interests and backgrounds, and then how can I incorporate something to engage them all on a daily basis? It’s not easy when it ranges from pink cupcakes to Justin Bieber or one Direction, snot jokes, war games or sport. If you think of what all the kids are into when you’ve got a group, you’re not going to be able to engage every single one of them at one time. But just if you’ve got more of an awareness like we’ve been talking about with what your kids are into, then that helps you with your classroom programme . . . So it’s not easy, but not impossible. (RH, 2012, pp. 2–3, emphasis added).

Here the teacher notes the complex diversity of the classroom and individual students that we all strive to cater for on a daily basis. The task of engaging with the diversity of one student’s literacy practices in and out of school illustrated the need for teachers to draw on students’ funds of knowledge (Moll et al., 1992) as a means to make literacy pedagogy more authentic and relevant.

This notion that “it’s not easy, but not impossible” was evident in students’ advice to teachers on how to teach critical multiliteracies. They offered a rich but eclectic range of suggestions for teachers. for example,

Peer teaching seems to help kids who are struggling more than one-on-one with the teacher, so introducing a buddy learning programme is a good idea. (p, 2012) I find it easier when learning multiliteracy to work in groups because it helps to talk to other people about the different systems and how they work. (p, 2012)

I’d let them do some hands-on things. So I’d let them, if I trusted them, I’d let them go into YouTube and find a YouTube video and point out one that showed all five semiotic systems. (FGI, 2011, p. 7)

Make them work by themselves. (FGI, 2011, p. 5)

Teachers should also ask for their students’ opinions on what they want to learn and how they want to learn it. (p, 2012)

These excerpts are but a few of the suggestions made by the students. The diversity of their advice reinforces the idea that there is no one right way to go about teaching critical multiliteracies. Listening to your students, however, is vital.

A very important element of the design of this project was how we positioned students. They acted as researchers who shared their sage advice with the teachers and researchers on the project. The research poster fair gave the students an opportunity to publicly share with a wider audience including teacher educators, principals and parents. We found in one instance that the students were not only able to comment on the teachers’ pedagogy, but they could do so by applying the metalanguage of critical multiliteracies. Students commented on the ways their teacher effectively positioned herself in the classroom. The teacher unusually locates herself in the centre of the classroom to direct the lesson, rather than at the front of the room.

Student 5: Yeah she doesn’t usually like stand up at the front, she usually like sits herself down right in the middle . . .

Student 2: So she can see our point of view.

Student 5: So it’s seeing what we see and stuff.

Interviewer: So she uses [the] spatial [semiotic system]?

Student 1: Mmmm, very carefully. (FGI, 2012, p. 7)

In our view, this is a sophisticated observation. The students are not only aware of what the teacher does in order to teach, but also view the act of teaching as a text. They are able to apply the metalanguage of the semiotic systems to make sense of why their teacher chooses this atypical pedagogy.

The notion of listening to students to inform pedagogy is not new (e.g., Cook-Sather, 2006; Sandretto with Klenner, 2011). A number of educational researchers advocate for working alongside students to make enlightened school reform and educational policy (Bolstad, 2011; Fielding, 2001; Rudduck, 2007). We found by positioning the students as powerful partners in learning we could begin to articulate ways that teachers can bridge students’ in- and out-of-school literacies. This bridge supports teachers and students to enhance their critical analysis of multiple types of texts to prepare them for a multiliterate future.

Implications

In this section, we discuss the implications of our two key findings: the challenge of reconceptualising literacy and literacy practices, and the challenge of rethinking pedagogy.

Reconceptualising literacy and literacy practices

The first implication from this challenge of reconceptualising literacy and literacy practices is that teachers need to expand their literacy repertoire by increasing the variety and types of texts they use with students in the classroom.

Teachers need to feel free to experiment with the wave of new multimodal texts that draw upon audio, gestural, linguistic, spatial and visual codes and conventions to communicate. Teachers will also need support from colleagues and management to shift their practices beyond an over reliance on traditional paper texts that draw largely upon the linguistic semiotic system.

A second implication is to consider how the reconceptualisation of literacy might play out, or be evident, in classroom practice.

Teachers will need to engage in direct acts of teaching to support students to take ownership of the metalanguage of critical multiliteracies and apply it across their everyday lives in and out of school.

Teachers and students will need to revisit the metalanguage as they engage with a variety of texts for a variety of purposes across the curriculum.

Rethinking pedagogy

The first implication of this challenge of rethinking pedagogy is that teachers need to find ways to listen to students to inform teaching and learning.

How might teachers do this? In the project we conducted focus group interviews with students as a means to listen to them and inform our evolving critical multiliteracy pedagogies. Teachers conducted an ethnography of the literacy practices of one student in and out-of-school (Sandretto & Tilson, 2011), and the students completed an auto-ethnography of their own multiliterate practices and shared their findings at a research poster fair (Kenway & Youdell, 2011). The intersection of these three data sources richly informed the participating teachers’ literacy pedagogies. The teachers aim to uplift some of these data gathering tools to continue to inform their practices.

A second implication of the second challenge is a consideration of the frame one might use as a prompt to rethink pedagogy. Teachers need to audit their literacy programmes to ensure that they support students to engage with all four resources of decoding, making meaning, using texts and critically analysing texts.

A number of researchers working in the field of multiliteracies advocate that teachers map their literacy programmes against the four resource model to ensure that they are delivering a balanced literacy programme (Santoro, 2004).

Limitations

Every project has limitations. A limitation of this project was the narrow age band of participating students. While the age band of participating students included only year 7 and 8 students, this project sought to address a paucity of research that connects literacy instruction at the middle school level with students’ out-of-school literacies (Alvermann, 2004). The researchers in the project, however, support the enactment of critical multiliteracies across the full primary and secondary sectors (Bull & Anstey, 2010), including the early childhood sector (Haggerty & Mitchell, 2010).

Conclusions

The participating teachers in the project were positioned as knowledgeable professionals who acted as researchers, as well as developed and implemented multiliteracies pedagogies for their own contexts. The teachers, and the students, were not positioned as what has been described in the literature as “data plantations” (Irving , 1997, as cited in Tyson, 2006, p. 42), but rather they were active members of the research team who were co-constructing knowledge alongside the researchers. Good research is good professional development for the researchers (see Honan, 2007). All the participating researchers, teachers and students learned a great deal about critical multiliteracies and ourselves as critically multiliterate people. The ultimate goal for most research projects in education is to support changes in practice. While we concede that there is a great deal more work to be done, we believe we have made a start: “I think because of this research my teaching will be changed” (EI, 2011, p. 1). Another teacher commented:

I think for me it actually quite, it will be quite a significant change, it should help me to have a . . . much richer literacy programme and with kind of deeper thinking and richer tasks and yeah I hope it will be really useful, and like [participating teacher] I am pretty sceptical about a lot of PD yeah you, I don’t know how much it cost, $300 a day plus a reliever and you wonder afterwards what you actually got out of it but I actually feel that my thinking has developed and it can add on to the stuff that I do and it can fit into the stuff that I do. (IE, 2011, p. 10)

The challenges of reconceptualising literacy and rethinking pedagogy will not be achieved overnight. Teachers and their students need multiple opportunities over extended periods of time to engage with the theories and practices of critical multiliteracies and to shape them for their own contexts. Research that creates opportunities for students, teachers and researchers to work together to co-construct new knowledge will support us all to achieve these goals.

Footnotes

- Reproduced with permission. See http://www.tonyogle.com/originals/wave+watchers.html ↑

- The abbreviations listed here are used as codes to identify the sources of the data extracts later on in this report. ↑

- follow-up interviews with the 2012 participating teachers to explore sustainability will take place during Term 2 of 2013. ↑

- Some of the identifying features of the transcript audit trail have been removed to ensure the anonymity of the participating teachers and students. ↑

References

Alvermann, D. E. (2004). Seeing and then seeing again. Journal of Literacy Research, 36(3), 289–302.

Anstey, M., & Bull, G. (2006). Teaching and learning multiliteracies: Changing times, changing literacies. Newark, DE: International Reading Association.

Bolstad, R. (2011). from “student voice” to “youth-adult partnership”. Set: Research Information for Teachers 1, 31–33.

Bulfin, S., & North, S. (2007). negotiating digital literacy practices across school and home: Case studies of young people in Australia. Language and Education, 21(3), 247–263.

Bull, G., & Anstey, M. (2010). Evolving pedagogies: Reading and writing in a multimodal world. Carlton, Vic: Curriculum Press.

Cook-Sather, A. (2006). “Change based on what students say”: preparing teachers for a paradoxical model of leadership. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 9(4), 345–358.

Cope, B., & Kalantzis, M. (2006). From literacy to “multiliteracies” learning to mean in the new communications environment. English Studies in Africa, 49(1), 23–45.

Cope, B., & Kalantzis, M. (2009). “Multiliteracies”: new literacies, new learning. Pedagogies: An International Journal, 4(3), 164–195.

Cummins, J. (2006). Multiliteracies and equity: How do Canadian schools measure up? Education Canada, 46(2), 4–7.

El Refaie, E. (2009). Multiliteracies: How readers interpret political cartoons. Visual Communication, 8(2), 181–205.

Fielding, M. (2001). Beyond the rhetoric of student voice: new departures or new constraints in the transformation of 21st century schooling? FORUM, 43(2), 100–110.

Gee, J. P., Hull, G., & Lankshear, C. (1996). The new work order: Behind the language of the new capitalism. St Leonards, NSW: Allen & Unwin.

Gilbert, J. (2005). Catching the knowledge wave? The knowledge society and the future of education. Wellington: NZCER press.

Haggerty, M., & Mitchell, l. (2010). exploring curriculum implications of multimodal literacy in a New Zealand early childhood setting. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 18(3), 327–339. Doi: 10.1080/1350293x.2010.500073 Healy, A., & Honan, E. (2004). Text next: New resources for literacy learning. Newtown, NSW, Australia: PETA.

Honan, E. (2007). Teachers engaging in Research as professional Development. In T. Townsend & R. Bates (eds.), Handbook of Teacher Education (pp. 613–624): Springer Netherlands.

Hull, G., & Schultz, K. (2001). Literacy and learning out of school: a review of theory and research. Review of Educational Research, 71(4), 575–611.

Jones, S. (2009). Making connections with multiliteracies. Wellington: Ministry of Education.

Kenway, J., & Youdell, D. (2011). The emotional geographies of education: Beginning a conversation. Emotion, Space and Society, 4(3), 131–136. Doi: 10.1016/j.emospa.2011.07.001

Kress, G. (2003). Literacy in the new media age. London: Routledge.

Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lewis, C., & Fabos, B. (2000). But will it work in the heartland? a response and illustration. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 43(5), 462–469.

Lewis, C., & Fabos, B. (2005). Instant messaging, literacies, and social identities. Reading Research Quarterly, 40(4), 470–501.

Limbrick, l., & Aikman, M. (2008). Literacy and English: a discussion document prepared for the Minister of Education (pp. 1–30). Auckland: Faculty of Education, University of Auckland.

Luke, A., & Freebody, P. (1999). A map of possible practices: further notes on the four resources model. Practically Primary, 4(2). Retrieved from http://www.alea.edu.au/Freebody.htm

McClay, J. K. (2006). Collaborating with teachers and students in multiliteracies research:” Se hace camino al andar”. Alberta Journal of Educational Research, 52(3), 182–195.

McDowall, S., Cameron , M., Dinglewith, R. , Gilmore, A., & Macgibbon, l. (2007). Evaluation of the literacy professional development project. Wellington: Ministry of Education.

Mclean, C. A., & Rowsell, J. (2013). (Re)designing literacy teacher education: a call for change. Teaching Education, 24(1), 1–26. Doi: 10.1080/10476210.2012.721127

Millard, E. (2006). Transformative pedagogy: Teachers creating a literacy of fusion. In K. Pahl & J. Rowsell (eds.), Travel notes from the New Literacy studies (pp. 234–253). Clevedon: Multilingual Matters ltd.

Mills, K. A. (2006). ‘Mr Travelling-at-will Ted Doyle’ discourses in a multiliteracies classroom. Australian Journal of Language and Literacy, 29(2), 132(118).

Mills, K. A. (2010). A review of the “digital turn” in the new literacy Studies. Review of Educational Research, 80(2), 246–271.

Minarik, l. T. (2000). A second grade teacher’s encounters with multiple literacies. In M. A. Gallego & S. Hollingsworth (eds.), What counts as literacy: Challenging the school standard (pp. 285–291). New York: Teachers College Press.

Ministry of Education. (2003). Effective literacy practice in years 1–4. Wellington, New Zealand: Learning Media.

Ministry of Education. (2005). Guided reading: Years 5–8. Wellington: Learning Media Ltd.

Moje, E. B., Ciechanowski, K. M., Kramer, K., Ellis, l., Carrillo, R. , & Collazo, T. (2004). Working toward Third Space in content area literacy: an examination of everyday Funds of Knowledge and discourse. Reading Research Quarterly, 39(1), 38–70.

Moje, E. B., & Lewis, C. (2007). Examining opportunities to learn literacy: The role of critical sociocultural literacy research. In C. Lewis, P. Enciso & E. B. Moje (eds.), Reframing sociocultural research on literacy: Identity, agency and power (pp. 15–48). Mahwah, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum associates.

Moll, l. C., Amanti, C., Neff, D., & Gonzalez, N. (1992). Funds of knowledge for teaching: using a qualitative approach to connect homes and classrooms. Theory into Practice, 31(2), 132–141.

Peterson, S. S., Botelho, M. J., Jang, E., & Kerekes, J. (2007). Writing assessment: what would multiliteracies teachers do? Literacy Learning: The Middle Years, 15(1), 29–35.

Robinson, E., & Robinson, S. (2003). What does it mean? Discourse, text, culture: An Introduction. Sydney, NSW: Mcgraw-Hill Book Company.

Rudduck, J. (2007). Student voice, student engagement, and school reform. In D. Thiessen & A. Cook-Sather (eds.), International handbook of student experience in elementary and secondary school (pp. 587–610). Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer.

Sandretto, S., & Critical literacy Research Team. (2006). Extending guided reading with critical literacy. Set: Research Information for Teachers, 3, 23–28.

Sandretto, S., & Critical literacy Research Team. (2008). A collaborative self-study into the development and integration of critical literacy practices: final report. Wellington: Teaching and Learning Research Initiative (TLRI).

Sandretto, S., & Tilson, J. (2011). Teachers conducting research into the in and out-of-school multiliterate practices of their students: What can we learn? Paper presented at the Australian Literacy Educators’ Association National Conference, Melbourne.

Sandretto, S., Tilson, J., Hill, P., Howland, R., Parker, R., & Upton, J. (2006). A collaborative self-study into the development of critical literacy practices: Final report. Wellington: Teaching and Learning Research Initiative.

Sandretto, S., with Klenner, S. (2011). Planting seeds: Embedding critical literacy into your classroom programme. Wellington, New Zealand: NZCER press.

Santoro, N. (2004). Using the four resources model across the curriculum. In A. Healy & E. Honan (eds.), Text next: New resources for literacy learning (pp. 51–67). Newtown, NSW, Australia: PETA.

The New London Group. (1996). A pedagogy of multiliteracies: Designing social futures. Harvard Educational Review, 66(1), 60–92.

Tyson, C. A. (2006). Research, race and social education. In K. C. Barton (ed.), Research methods in social studies education (pp. 39–56). Greenwich, CN: Information Age Publishing.

Unsworth, l. (2006). Towards a metalanguage for multiliteracies education: Describing the meaning-making resources of language-image interaction. English Teaching: Practice and Critique, 5(1), 55–76.

Walsh, C. (2006). Beyond the workshop: Doing multiliteracies with adolescents. English in Australia, 41(3), 49–57.

Conference presentations

Hokianga, T., Sandretto, S., & Tilson, J. (2012, September-October). Weaving critical multiliteracies into your classroom programme. Paper presented at the New Zealand Reading association Reading Between the Vines Conference, Hastings, New Zealand.

Prentice, S., Gray, K., Sandretto, S., & Tilson, J. (2012, 4-6 July). Weaving multiliteracies into your classroom programme. Paper presented at the NZATE Words to Burn-Ideas to Ignite, Dunedin, New Zealand.

Sandretto, S., & Tilson, J. (2011a). Preparing students for multiliteracies: Looking to teacher research into the in and out-of-school multiliterate practices of their students. Paper presented at the Australasian Human Development Association 17th Biennial Conference, Dunedin.

Sandretto, S., & Tilson, J. (2011b). Teachers conducting research into the in and out-of-school multiliterate practices of their students: What can we learn? Paper presented at the Australian Literacy Educators’ Association National Conference, Melbourne.

Sandretto, S., & Tilson, J. (2012, September-October). “I sort of thought I knew myself”: Student ethnographies into their multiliterate development. Paper presented at the New Zealand Reading Association Reading Between the Vines Conference, Hastings, New Zealand.

Project Team

The project team comprised two principal researchers and participating teachers and partnership schools.

Participating Teachers

2011

Row 1 (l–R): Susan Sandretto, Shannon Prentice, Kathyrn Gray, Jane Tilson, Jillian Mclean and Kathyrne Tofia.

Row 2: Darryl Reddington, Mark Hunter, Rob Wells, David Ownen and Jared Roddick.

2012

Row 1 (l–R): Moana Thorn, Susan Sandretto, Jane Tilson, Vicky Spiers, Aaron Warrington, and Marianne Coughlin.

Row 2: Sarah Gilbert, Greg Lees, Matt Broad, Chris Marslin, Nigel Waters, Rebecca Johnston and Terry Hokianga

Principal Researchers

Susan Sandretto is currently the primary programmes Coordinator at the University of Otago College of education. She was a member of the Ministry of Education’s Multiliteracies working group. Her research interests include multiliteracies, critical literacy, gender issues in education and practitioner research. She teaches across the primary teacher education and education studies programmes and supervises at the postgraduate level.

Jane Tilson works as a lecturer and researcher at the University of Otago College of education. She currently teaches across the graduate diploma and primary teacher education programmes. Her teaching and research interests include critical literacy and critical multiliteracies, and professional and reflective practice.

Partnership schools

Port Chalmers School

Fairfield School Outram School

Green Island School

St. Hilda’s Collegiate

Dunedin North Intermediate

Tahuna Normal Intermediate

Reference group

Dr. Karen Nairn

Jo Harford

Jenny Hodgkinson

Jennie Upton

Rae Parker