Introduction

This Teaching and learning research initiative (TLRI) project was sited in a kindergarten, Tai Tamariki, at the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa in Wellington. This kindergarten is a full day-centre for children aged 0–5 years. On average, 70 percent of the families include staff at Te Papa. The research focused on the relationship between the teachers, children and families at the kindergarten and selected exhibitions at Te Papa. It was extended to include these relationships with exhibitions at nearby art galleries.

Key findings

The project’s goals and intentions were to construct an understanding of how the children at this kindergarten made meaning of what they encountered and experienced at the museum, and what opportunities strengthened this learning. There were three key findings from this:

- Children’s meaning-making practices: Children were making connections with prior knowledge, recognising alternative perspectives, developing expertise, personalising their experience and engaging in dialogue.

- The opportunities: Boundary objects (laminated photographs of the exhibits, sketch books, learning stories, and, for one exhibit, a book especially prepared) invited and provoked dialogue about museum objects and exhibitions.

- The opportunities: Teacher strategies for encouraging meaning-making dialogue included constructing boundary objects, providing resources for the children to represent their ideas, inviting perspective-taking, focusing the children’s attention, recognising and suggesting analogies and comparisons, introducing a problem or a puzzle, listening to the children’s views, and asking genuine questions.

Major implications

A permeable or flexible curriculum enables teachers to respond to children’s interests during and after visits to a museum. Children have a diversity of interests and were often enhancing their understanding by making connections to prior knowledge and experiences.

The construction of “boundary objects” that make connections between a museum and an early childhood centre or school can add opportunities for revisiting what has been learned.

These boundary objects must be accompanied by dialogue; the sites for this dialogue will include the museum or art gallery, the early childhood setting, or wider family contexts.

The research

The research has involved university researchers and teacher researchers working together to identify the ways in which children make meaning as they interact with the exhibits and collections at Te Papa. The kindergarten had not long opened when the research started and so both teachers and children were exploring this unique context and finding out what it meant to “go upstairs”. not only were there many amazing artefacts and collections to discover and explore but the physical space of the museum and the expectations and responsibilities associated with being a “museum visitor” also provided new and different learning opportunities.

Research questions

The three questions that guided the research were:

- How might the construction of knowledge and stories about the world and its representation in objects and exhibitions be encouraged in an early childhood centre at Te Papa? a sub-question was: How do young children construct knowledge from museum objects and exhibits?

- Does the opportunity to interact with a range of cultural taonga deepen children’s understanding of the bicultural heritage of Aotearoa/ New Zealand?

- How do the family members, as employees of Te Papa, contribute their “funds of knowledge” to the learning experiences of children attending the early childhood centre, and how do the children share their experiences with their families?

The relevance of these questions to learning and teaching in New Zealand

Learning experiences outside the classroom. New Zealand research on learning experiences outside the classroom (Moreland, Mcgee, Jones, Milne, Donaghy, & Miller, 2005) included a case study of a new entrant/ year 1 class visiting an art gallery. The responses from the children were expressed in drawings, and the long-term relationship and associated regular visits by the children to the local gallery and the local museum was an important feature of their continuity of interest back at school.

Family engagement. research (Hattie, 2005; siraj-Blatchford, 2010) indicates that family expectations strongly influence children’s engagement with education at school. an earlier Tlri project by two of the authors of the current study, involving Taitoko Kindergarten in levin (Clarkin-Phillips & Carr, in press), researched the engagement of parents/whānau in their children’s learning. Initiatives relevant to the current study which engaged families included wall displays of learning stories that came from, or were connected to, family and community; a “transition” portfolio that linked early childhood outcomes with school key competencies; and invitations to families and whānau to have a say on assessments. Comments from whānau indicated that the early childhood programme encouraged whānau to have high, evidence-based expectations, and for children to make connections to their experiences at home.

Museum education outside the centre and the classroom. Museum education can provide rich opportunities for children’s learning. Anderson, Piscitelli, Weier, Everett, and Taylor (2002), Everett & Piscitelli (2006), and Piscitelli and Anderson (2001) have written of the benefits of children having experiences with authentic artefacts and resources such as are available through museums and art galleries. Their research (in Australia) on 99 children aged between 4 and 6 years old and four museums found that the children appeared to make few links and connections between the museum experience and their experience back in the classroom or early childhood centre or in their home settings, and the authors suggested that children may “compartmentalise” their learning by place. Australian research explored the ways in which children shared their ideas and experiences with others: teachers, peers and families. This is relevant to New Zealand, since all cities have major museums and many towns have local museums; schools and early childhood centres visit them frequently.

Methodology and analysis

The project used a methodology under the general umbrella of practitioner inquiry or action research. In this case, university researchers worked with teacher researchers in a “continuous process of problem posing, data gathering, analysis, and action” (Cochran-Smith & Donnell (2006, p. 504). This collaboration was valuable for researching the complexity of the kindergarten context and for providing opportunities for university researchers, teacher researchers and children to develop a stronger and more authentic understanding of their teaching-and-learning practices. Practitioner or teacher inquiry blurs the boundary between research and practice; it has the capacity to construct theory and to contribute to our understanding of knowing and learning (Cochran-Smith & Donnell, 2006). Four exhibitions formed four “cycles” of data-gathering and were the central focus of this research: (a) the Paperskin exhibition of tapa artefacts and masks from Papua new guinea, including a video of the Baining fire dancers, (b) the European Masters exhibition of paintings, (c) an exhibition of artists from the Pacific, Oceania, at the Wellington City Gallery, and (d) permanent exhibitions at Rongomaraeroa Marae at Te Papa.

The Paperskin exhibition

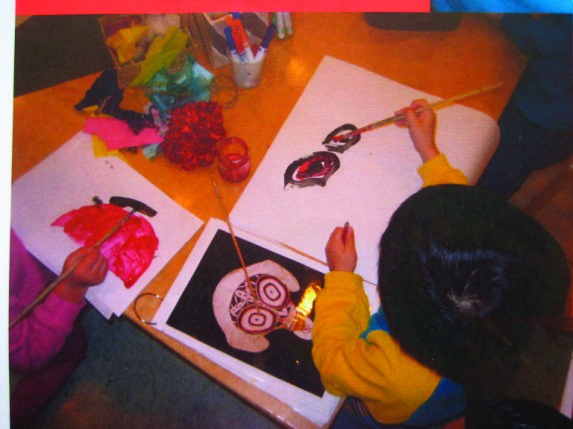

Before the visits to the Paperskin exhibition, regular documentation of the children’s work had included their interest in mask-making, fabrics (including tapa cloth in the permanent exhibition) and face painting. We collected these documents, which included photographs (some of them on the wall of the kindergarten) and written records of episodes of learning. Inspection of this data alerted us to the role of materials in the construction of interest and exploration by small groups of children. A teacher had brought in a roll of plain blue fabric and the children cut out the fabric, draped it, and connected it back together in different ways, using cellotape, tying, a glue gun, and sewing. Table mirrors had encouraged face-painting, and another teacher brought in some large brown paper bags; the children used these to make masks, painting them and adding decorative elements.

The new exhibition of tapa cloth artefacts from the south Pacific, entitled Paperskin, opened at the museum. This exhibition included large patterned tapa cloth wall hangings, a number of large and striking masks made from bamboo and tapa cloth and a video of the Papua New Guinea Baining fire dancers. The teachers and 10 children aged between two-and-a half and five years made five visits to the Paperskin exhibition; the university researchers accompanied them on two of these visits. Learning stories were written of these visits and follow-on activities were also photographed, documented and discussed. a book was constructed to respond to the children’s interest in the fire dancers, and an audiotape was made of conversations.

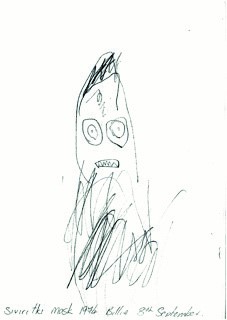

Children took sketchbooks with them and drew their favourite masks or tapa patterns. a video demonstrating the purpose and making of tapa ran continuously during the exhibition.

Back at the kindergarten, the children’s drawings of masks and tapa patterns were displayed. The teachers downloaded images of the masks and tapa which were laminated and put around the art area for the children’s reference. One child used a photo of his favourite mask to paint a detailed representation of the mask, asking for specific paint colours and choosing different sized brushes for the finer details. another child used some bark pieces, pipe-cleaners and other materials to recreate a two-headed crocodile mask, inspired by the Paperskin exhibition. another example of meaning-making occurred when a child told a personal story using a tapa pattern after looking at images and talking about them. Her story included horizontal lines for the land, side-by-side circles for the sea, triangles for trees and at the very bottom of the picture her close kindergarten friend (who was overseas at the time) “holding her breath forever”.

The book about the Baining Fire Dancers provided further opportunities for discussion. The dialogue and conversations between the children and teachers as they looked at the book together created opportunities for the children to explore and express different perspectives, make connections with prior experiences, look and listen attentively and make analogies and comparisons.

We were interested in how children shared their knowledge and experiences of the museum with their families. In some instances, children insisted on taking their parents upstairs to show them their favourite exhibits. after the Paperskin exhibition, some of the children were keen to take their parents to show them the masks and tapa. One parent reported: “she took me around and explained what all the pieces were—she had remembered a lot of what the exhibit was about from her visits with the kindergarten children”. another parent talked about her child, who was particularly interested in the fire dancers, making drawings of these at home on a number of occasions. One family who have a collection of masks from different countries displayed on their walls at home commented that their daughter insisted on knowing where every mask came from and made a tapa mask to wear to a birthday dress up party. This interest in masks coincided with visits to Paperskin.

|

|

Details of the findings from this phase of the project have been published in Carr, Clarkin-Phillips, Beer, Thomas, & Waitai (2012). In summary, the children’s focused attention and meaning-making from their visits to the Paperskin exhibition were strengthened by:

- Boundary objects that travelled to and from Te Papa and Tai Tamariki, or appeared in both places, or were clearly connecting objects (sketch books, learning stories and assessment portfolios, books specially written about an exhibit and read in both places, an exhibit cabinet in the kindergarten)

- dialogue between teachers and children (or among children) that accompanied the boundary objects

- Opportunities, including resources, for multimodal meaning-making at the kindergarten.

The European Masters exhibition

The European Masters exhibition included 96 nineteenth- and twentieth-century paintings from the Städel Museum in Frankfurt, Germany. Visiting the exhibition meant children needed to learn the protocols associated with art galleries: for example, staying behind the yellow line when looking at a painting, and talking quietly. The Tai Tamariki children very quickly assumed the role of “exhibition hosts” and would remind visitors to stay behind the line or “not talk in too louder voices”.

The kindergarten visited this exhibition four times, which gave the children the opportunity to become familiar with the paintings. The teachers also purchased the book containing reproductions of the paintings, photocopying and laminating many of these to display them around the kindergarten in much the same way as had been done with the Paperskin images. sketchbooks were not allowed in the exhibition so the reproduced images were a useful prompt for drawings and paintings back at the kindergarten.

The teachers documented the children’s comments while visiting the exhibition and displayed any related work at the kindergarten. The children were also gaining further knowledge about the displaying of artefacts. They began to ask the teachers to read what was on the information cards beside each painting and this provided ideas or opinions from the children. Including the name and dates of the artist, the title (or “untitled”) of the work, and the medium used to create the work, became a familiar practice to the children who would insist that this information was included on a card alongside any of their own displayed work. Children looked intently at the paintings and saw details not noticed by adults. In one encounter a child talked about the donkeys in a painting and a museum visitor standing alongside that child said “i didn’t even see the donkeys until you pointed them out”.

The analysis of the documentation on this phase found children making meaning in the following ways, either spontaneously or in response to cues, modelling, or provocations from the teachers:

- making connections with previous knowledge and other exhibitions

- looking closely

- making commentary that includes affect or feelings associated with viewing a painting, and sharing these ideas with others

- making sense of a painting by personal storying

- imaginatively representing ideas in their own paintings, inspired by a particular painting or paintings from the exhibition

- adding or requesting written labels in order to provide relevant information for others.

The Oceania exhibition

The teachers had noticed the children’s interest in cameras and, coupled with the Brian Brake photography exhibition, the children made their own photo exhibition at the kindergarten. When one of the toddlers tried to rip the pictures off the wall and the teacher explained that she (the toddler) didn’t understand that this was not appropriate, an older child explained “How could she know? There’s no line”. The child was referring to the yellow lines at the art exhibition that form a barrier when viewing artworks. He then asked for tape and constructed a line for the kindergarten’s exhibition.

The Oceania exhibition provided further opportunities for children to represent and re-contextualise their knowledge. This exhibition was in collaboration with the Wellington City Gallery, which is within easy walking distance from the kindergarten. The children visited the City Gallery and the associated works at Te Papa. Particularly distinctive artistic styles, such as works by Richard Killeen displayed in both locations, were recognised by the children as the “same”. The visits to the City Gallery prompted ideas about the children constructing their own gallery at the kindergarten. Facilitated by questioning and provocations from the teachers, the children used a collapsible wooden house frame (previously constructed for them by parents employed at Te Papa) to make their gallery. The idea that white walls are necessary to make the artwork look “differenter” resolved the question of what colour to paint the gallery.

Our analysis found that children were growing an understanding of the protocols and etiquette associated with art galleries and museums in the following ways:

- The children recognised that lines (usually yellow) on the floor, as barriers to the visitor, were signs for a sensible rule in a gallery.

- They recognised “no touching” and “no camera” signs, (which they constructed for their own gallery).

- Art works were carefully and thoughtfully displayed by the children, accompanied by information cards that included the child’s name and the date.

- The children used materials other than paints, crayons, pencils and collage resources to create art works that belong to the wider world of “art”. Installations involving tyres, plastic crates and other “found” materials from the kindergarten environment were constructed inside the art gallery and given titles.

- Attention was paid to the background for an art display.

- The children recognised the importance of being respectful of others in a gallery, speaking quietly and modelling this for the younger children.

Rongomaraeroa Marae at Te Papa: The opportunity to interact with a range of cultural taonga

The children at the kindergarten regularly visited the permanent exhibitions at Te Papa, especially the marae, Rongomaraeroa. The kindergarten’s infants and toddlers were included in these visits; they became familiar with the route from the kindergarten to the marae, and often returned to the carvings, which they were permitted to touch. These visits were enhanced by teachers fluent in te reo Māori and knowledgeable about taonga. These teachers talked to the children about the stories that accompany the carvings and wrote stories about the children’s responses for their portfolios. They also facilitated visits from other centres, giving advice that had emerged from the experience of Tai Tamariki visits.

A number of practices instituted at the kindergarten have been influenced and enriched by the access to taonga of tangata whenua. When a decision was made to make a korowai as a “special day” commemoration garment (birthday or leaving celebrations), the teachers took the children to look at the korowai collection upstairs in the museum. an interest in weaving stemmed from these visits and so further connections were made between traditional Māori practices. Wearing the korowai has become a part of the culture at Tai Tamariki and a parent commented on how “proud my daughter was when she wore the korowai on her birthday”.

Regular kapa haka sessions held at the museum provided opportunities for children to become involved with this tikanga practice and the teachers reported the children re-enacting haka and song with poi back at the kindergarten. an interest in the taonga pūoro permanent collection allows children to become familiar with traditional Māori instruments and describe their sounds. One child comments that the pūtorino (bugle or double bugle) is “like a smile”, and the nguru (nose flute) sounds “like a bird”. “i can hear the person’s breath that was doing the flute”, a child exclaimed when listening to the kōauau/flutes. Later, at the kindergarten, some of the children who had been upstairs to interact with the puōro, picked up shells and blew into them to make sounds or made noises with their mouths and breath, imitating the sounds of the puōro.

Parents have also commented on children’s growing knowledge of things Māori. One parent, as a recent immigrant to New Zealand, was impressed by his child’s knowledge of te reo and the meaning of artefacts such as pou and korowai.

The availability and accessibility of Aotearoa artefacts and taonga enabled the children to embody their knowledge through their everyday interactions with people places and things. One of the children commented to a teacher during a visit upstairs to Rongomaraeroa, “look, that’s a koru, like Māori, isn’t it” as she pointed out the patterns on the heke rafter panels. Later that day she was incorporating koru into her artwork.

Another example was the children’s growing familiarity with a range of artefacts. One of the teachers talked about children’s knowledge of moko and its depiction of genealogy and whakapapa. a child looked at three plain life masks and a fourth with a moko and commented “they are all the same but different because we’re looking forward and looking back”. This was her understanding of the stories that moko tell.

The analysis of this phase shows that opportunities for children to develop an understanding of the taonga at Rongomaraeroa were enhanced by:

- teachers who are fluent Maori speakers and knowledgeable about the taonga and the stories and whakapapa that accompany them

- teachers writing learning stories about the children’s interactions with the collections and exhibits for their portfolios and therefore for their whānau—often the learning stories contribute to wall displays

- respectful processes in the museum, and respect for cultural ceremony accompanied by korowai back at the kindergarten

- exhibits that enabled children to interact with the taonga puōro, to listen carefully several times to their favourites, and teachers who recognised (and joined) their attempts to copy the sounds when they were back at the kindergarten

- a marae complex that is open to all, and carvings that can be touched by the children.

Major implications for practice

Boundary objects

The development of boundary objects by the teachers has been helpful in helping children make connections between the kindergarten and the museum. These boundary objects have included sketchbooks, laminated photographs of exhibits and artefacts, and learning stories that document children’s experiences in the museum and at the kindergarten. The availability of open-ended resources for art and construction has been important in allowing children to represent and translate what they had observed at the museums.

The sketchbooks have been taken by the children on visits to the museum and used to draw their favourite artefacts; these are then available to them back at the kindergarten for further reference or revisiting. Children have become skilled at observational drawing, developing ideas about perspective, size and proportion. Laminated photographs of exhibits placed both on the walls of the kindergarten alongside children’s representations of artefacts and around the art area have provided opportunities for children to revisit and study their favourite pieces without having to return to the exhibition.

The specialised language of museums and galleries has become part of the children’s vocabulary. Words such as displaying, titles, taonga, white and yellow lines, gallery, museum, artist, host, feature regularly in children’s conversations both at the kindergarten and visits upstairs.

Boundary objects can be created for any excursion and they will be particularly relevant and value-added when used for one-off excursions. We are mindful that Tai Tamariki is a unique context and that other early childhood centres will seldom have the ability to regularly revisit places outside the centre. However, we hope that our findings about the usefulness of boundary objects provides ideas for other centres to maximise learning outside the centre and create opportunities for children to revisit and re-contextualise their experiences.

Importance of dialogue

Using dialogue to create opportunities for children to recall, make connections, personalise events, create analogies and make comparisons has been a key to sustaining learning. These conversations that include teacher strategies such as focusing, introducing a problem, asking for children’s ideas and opinions when the teacher genuinely doesn’t know the answer, allow children to make meaning and strengthen their understandings and learning dispositions. Quality teacher child interactions are imperative to children’s learning (Dunkin & Hanna, 2001); this research illustrated the ways in which early childhood teachers enhance this learning by responsive and reciprocal relationships and conversations about artefacts, collections and exhibitions in a museum.

Families contributing their funds of knowledge

There is much research that outlines benefits for children when their families are involved in their education (Gonzalez, Moll, & Amanti, 2005; Draper & Duffy, 2003) while the family and community principle in Te Whāriki states “the wider world of family and community is an integral part of the early childhood curriculum’ (p. 42). This research has explored how families’ “funds of knowledge” are used in the kindergarten to extend and enhance children’s learning. at Tai Tamariki, many of the parents (about 70 percent) are employed at Te Papa in a wide range of roles. Over time, as relationships have been built, parents have been able to share some of their knowledge and expertise with the teachers and children as time and conditions have allowed. This sharing and accessing of resources has enabled teachers and children to make stronger connections between “upstairs” and the kindergarten. For instance, the kindergarten has acquired display cabinets, like those used in the museum. Children are able to exhibit their creations in these cabinets and, because of their growing familiarity with displaying and exhibiting, provide information about their art works to be written on cards and displayed, next to their work. These display cabinets have also become “boundary objects” that are the same in two places, making valuable connections across contexts. Other early childhood centres could construct them too. Parents have helped teachers to create resources to extend children’s interest. One of these resources is a collapsible wooden “house” frame. This has become a whare, a house, a shop and, recently, an art gallery.

Although the unique context of Tai Tamariki will provide opportunities for using parent expertise, all early childhood centres will be able to draw on the knowledge and expertise of their community. It is through the relationships teachers build with families that we learn about families’ funds of knowledge and resources get shared. It is useful to remind ourselves about the potential for learning for the whole community (children, teachers and families) when we are committed to having strong relationships with a local museum or art gallery.

References

Anderson, D., Piscitelli, B., Weier, K., Everett, M., & Taylor, C. (2002). Children’s museum experiences: identifying powerful mediators of learning. Curator, 45, 213–31.

Carr, M., Clarkin-Phillips, J., Beer, A., Thomas, R. , & Waitai, M. (2012). young children developing meaning making practices in a museum: The role of boundary objects. Journal of Museum Management and Curatorship, 12, 53–66.

Clarkin-Phillips, J., Carr, M., Beer, A., Thomas, R. , & Waitai, M. ( 2011). The world upstairs: Children connecting two learning contexts. ecARTnz emagazine of professional practice for early childhood educators in Aotearoa New Zealand. retrieved 23 January, 2012, from http://www.elp.co.nz/educationalleadershipProject_resources_articles_ecarTnz.php

Clarkin-Phillips, J., & Carr, M. (in press). Strengthening reciprocal and responsive relationships in a Whānau Tangata Centre. 2007–2008. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal.

Cochran-Smith, M., & Donnell, K. (2006). Practitioner inquiry: Blurring the boundaries of theory and practice. In J. L. Green, G. Camilli, P. B. Elmore, A. Skukuaskaite, & P. Grace (eds.), Handbook of complementary methods of education (pp. 508–18). Washington, D.C: AERA.

Draper, l., & Duffy, B. (2003). Working with parents. In G. Pugh (ed.), Contemporary issues in the early years: Working collaboratively with parents (pp.146–158). London: Sage.

Dunkin, D., & Hanna, P. (2001). Thinking together: Quality adult:child interactions. Wellington, NZCER Press.

Everett, M., & Piscitelli, B. (2006). Hands-on trolleys: Facilitating learning through play. Visitors Studies Today, 9, 10–17.

González, N., Moll, l., & Amanti, C. (2005). Funds of knowledge. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Hattie, J. (2009). Visible learning. A synthesis of over 800 meta-analyses relating to achievement. London: Routledge.

Ministry of Education. (1996). Te Whāriki. He whāriki mātauranga mō ngā mokopuna o Aotearoa: Early childhood curriculum. Wellington: Learning Media.

Moreland, J., McGee, C., Jones, A., Milne, l., Donaghy, A., & Miller, T. (2005). Effectiveness of programmes for curriculum-based learning experiences outside the classroom. Wellington: Ministry of Education.

Piscitelli, B., & Anderson, D. (2001). Young children’s perspectives of museum settings and experiences. Museum Management and Curatorship, 19, 269–282.

Siraj-Blatchford, I. (2010). Learning in the home and at school: How working class children ‘succeed against the odds’. British Educational Research Journal, 36, 463–482.

Project contacts

Jeanette Clarkin-Phillips Dept of Professional studies Faculty of Education The University of Waikato Email: jgcp@waikato.ac.nz |

Professor Margaret Carr Wilf Malcolm Institute of Educational Research Faculty of Education The University of Waikatoemail margcarr@waikato.ac.nz |

Vanessa Paki Dept of Professional Studies Faculty of Education The University of Waikato email: paki@waikato.ac.nz |

Rebecca Thomas Tai Tamariki Kindergarten Te Papa Wellington |

Fiona Twaddle Tai Tamariki Kindergarten Te Papa Wellington |