Introduction

This project is about exploring and strengthening young children’s story-telling expertise. Building on research that shows that children’s narrative competence is linked to later literacy learning at school, we wanted to understand more fully how conditions for literacy learning are, and could be, supported within early years education settings. Using a design-based intervention methodology and a multi-layered analytical approach we observed and analysed story-telling episodes within early childhood settings and classrooms to understand, within these episodes, the contributions of contexts and story-partners for children’s early development of narrative competence. Our aim was to contribute to the international literature and develop storying strategies with and for teachers.

Literacy and narrative

We have known for a long time that the extent of very young children’s oral vocabulary is related to their later literacy performance in the early school years (Clay, 1991; Ministry of Education, 1999; NICHD Early Child Care Research Network, 2005; Suggate, Schaughency, & Reese, 2012). Children’s oral vocabulary is particularly important for their later reading comprehension once they have surpassed the ‘learning to read’ phase in Years 1 and 2 and have entered the ‘reading to learn’ phase by Years 3 and 4 (NICHD Early Child Care Research Network, 2005; Sénéchal & LeFevre, 2002). Oral language involves much more than simply vocabulary: other critical skills include children’s awareness of the sounds of words and their understanding and expression of larger story structures or narratives (Dickinson, McCabe, Anastasopoulos, Peisner-Feinberg, & Poe, 2003). Narrative skills in particular feature prominently in children’s later literacy in American and New Zealand research (Griffin, Hemphill, Camp, & Wolf, 2004; Reese, Suggate, Long, & Schaughency, 2010). For instance, Reese et al. (2010) demonstrated that the quality of children’s oral narrative expression in the first two years of reading instruction uniquely predicted their later reading, over and above the role of their vocabulary knowledge and decoding skill.

Narrative competence is a valuable outcome in its own right. A major source of support for preschool children’s narratives comes in the form of adult–child reminiscing conversations. These are critical to children’s remembering and telling of personal narratives (Reese & Fivush, 2008). In New Zealand education settings, however, with recent shifts towards narrative assessment approaches in early years settings (Gunn & de Vocht van Alphen, 2011; Morton, McMenamin, Moore, & Molloy, 2012), teachers are now turning children’s narratives in new directions, to include understanding and supporting learning. In New Zealand early childhood education provision (and in other countries too), narrative has therefore already become an important aspect of the pedagogy via assessment (Ministry of Education, 2004, 2007, 2009). Learning Story assessment resources from New Zealand (Carr, 2001; Carr & Lee, 2012) have been translated into Danish, Italian, Japanese, Korean, and Mandarin.

Much research in the area of children’s narrative and literacy to date has been conducted with children and families in the early years of primary school. Children’s narrative capabilities, however, are developing in the early childhood years, well before school entry (Reese & Newcombe, 2007; Snow, Burns, & Griffin, 1998), so we became interested in discovering how children are supported to story-tell in early childhood, and how these discoveries can inform the practice in early childhood settings and school. This project has considered narrative in a wider context—beyond assessment strategies—and has found that, in order for children to become adept at story-telling, the use of mediating resources (for example, conversation partners, objects, and environments that mediate storying) need to be wide-ranging and deliberate.

Building on prior research

This research has built on a collection of prior TLRI studies that have researched languages and literacy at a number of levels of early childhood and school. A recent project ‘Literacy Learning in e-learning Contexts: Mining the New Zealand action research evidence’ (McDowall, Davey, Hatherly, & Ham, 2012) has particularly strong links to the project. This e-learning project involved children and teachers from across the sectors of early childhood education (ECE), primary, and secondary. The key findings of the study indicated that ICT is employed by teachers to support children’s reading and writing in ways that exceeded usual print-based classroom methods (McDowall et al., 2012).

A TLRI project on young children’s learning in museums (Carr, Clarkin-Phillips, Beer, Thomas, & Waiatai, 2012) concluded that dialogue, designed to enhance meaning-making competencies, was strengthened by a set of mediating tools: ‘boundary objects’. These objects belonged in more than one place and provided a common focus for talk. We have used mediating tools to further explore how objects and artefacts are, and could be, used specifically for storying across several contexts and an extended period of time.

Large-scale quantitative research has demonstrated that narrative expertise in the early school years is linked to literacy competence (for example, Reese, Leyva, Sparks, & Grolnick, 2010). The research gap was the lack of in-depth case studies, over time, about what features of narrative expertise can develop in early childhood, how they can be strengthened in an early childhood centre, and how this development can be co-ordinated across several contexts in the early years (family, early childhood centre, New Entrant classroom, Year 1 and perhaps Year 2 classrooms).

Two relevant early childhood studies, ‘Learning Wisdom’ (see case studies from this project in Carr & Lee, 2012) and the recent ‘Pedagogical Intersubjectivity’ project (Bateman, 2012), contribute knowledge about methods of data collection and of analysis relevant to this current project. The first of these included audiotaping and videotaping conversations between teachers and children and identified context- and content-relevant conversational strategies that teachers used in order to implement effective teaching and learning. Conversations were analysed in broad terms: authenticity; co-authoring; personal connections; and group interactions (Carr, 2011). The teachers often deliberately used identity and disposition language that emphasised developing competence, a feature of interest in conversation analysis, one of the modes of data analysis used in this study. The data analysis in the ‘Pedagogical Intersubjectivity’ project demonstrated how teachers support children’s problem inquiry through systematic turn-taking sequences (Bateman, 2013) and the asymmetry of knowledge demonstrated between teachers and young children during everyday conversations (Bateman & Waters, 2013). Turn-taking sequences between teachers and children were analysed in detail using conversation analysis where this approach was found to be most valuable in demonstrating how teaching and learning was achieved in everyday practice.

Research partnerships between university researchers and teacher researchers in which learning stories feature as an assessment strategy or a mediating tool for conversations have also been useful (Carr et al., 2012; Gunn & de Vocht van Alphen, 2011; special issue of Early Childhood Folio, 2011). They reach into the digital world: videos that the children have produced, sequences of photographs taken by teachers or children (Carr & Lee, 2012 p. 37), learning stories re-visited (Gunn & Vocht van Alphen, 2011), and digital story-telling

(Colbert, 2006). Teachers often need guidance about when to add their own voices to communication episodes (Bateman, 2011); and there is a call to further investigate how stories are “begun and ended, how characters are introduced into a storytelling, how recipients figure out what they should or could be making of a storytelling, and how storytelling practices are used in institutional settings” (Mandelbaum, 2013, p. 506).

Research questions

Two major research questions guided this project:

- What storying opportunities exist in early years settings and what happens in them?

a. What contributions do story-partners make to these storying events? With what effects?

b. How do mediating resources work to support children’s storying? - How can these opportunities be strengthened?

Research design

This project used an inductive approach to discover the story-telling practices that were evident in everyday situations in early childhood centres and the first 18 months of school. This approach enabled us to provide a resource at the end of the project (Bateman, Carr, Gunn, & Reese, forthcoming) for early childhood and New Entrant teachers that includes exemplars of how storying can be strengthened across settings. The iterative cycle format in this methodology (video observation—university researcher analysis—collaborative discussions with teachers and family members—informing around what works) was especially appropriate for this project because it actively engaged participants in a collaborative and responsive research process. Teachers were therefore participants in the research, contributing to each design and to the follow-up discussions, and subsequently changing or adding to their practice as a response to the evolving findings. Families and children, too, were invited to participate in what we called a ‘story-telling advisory group’ (STAG). In this way we aimed to further the theoretical knowledge in the field; at the same time the project provided practical ideas, linked to valuable purposes, for practitioners.

Our methodological approach involved discussions between the university researchers, teacher researchers, children, and families in two early childhood centres (one in the North Island, and one in the South Island) about (i) opportunities and resources that encourage, and might further encourage, children to engage in story-telling and (ii) how we might recognise the features of storying that connect with literacy competence. The teachers’ past experiences and the families’ viewpoints were invaluable for these discussions. We used video recordings to embark on the research cycle in the two early childhood sites to begin:

- an investigation of what storying actually looked like for 12 four-year-old children in those two centres (six case studies in each), over several everyday sessions where teachers were aware of storying opportunities

- an analysis of story-telling episodes identified by the university researchers

- a discussion with the university researchers, teachers, children, and families in a STAG meeting to refine and improve analysis of story opportunities.

Cycle Two covered the same ground, several months after the first observation, in the same early childhood centres. For Cycles Three, Four, and Five the case study children were progressively moving to school, and so the video documentation followed the children to their first, second (and third in some cases) school classroom, following discussions that included the New Entrant teachers in the STAG meetings, and taking the children into the zone where their growing narrative competence is reflected in literacy expertise and motivation (Reese et al., 2010).

Data collection methods

Cycle One: January–June 2014

Two early childhood centres were chosen for six characteristics: sited in a low-income community (local schools are decile three or lower); some families for whom English is not the home language; a range of multi-modal communication resources available for teachers and children; an interest by the teachers in storying; a good working relationship with surrounding schools; and an enthusiasm for this research project. One was in the North Island (and worked with University of Waikato researchers) and one was in the South Island (where the University of Otago researchers worked). In each centre, six families, chosen by the age of the children (children who had their fifth birthday during the first two school terms of 2015 and all intend to attend the same school), were approached and agreed to participate in the research as case studies.

Data gathering included:

- Audio recordings of discussions with case study families, seeking information about storying in the home and establishing, with teachers, the STAG members.

- Over several days, and in negotiation with the teacher researchers, the university researchers observed, video recorded and audio recorded episodes of the case study children participating in the everyday routine of the centre where potential story-telling and story-making occurred.

- Field notes and recordings were taken during video recordings of each case study child, and episodes of story-telling and story-making were identified and transcribed, then discussed with families during a subsequent STAG meeting.

- Discussions between the teachers and university researchers occurred immediately after the observations and again after the initial analysis of the data. Together with the STAG members a new awareness of how to support story-telling and the benefits of specific types of story-telling was developed.

Cycles Two, Three, Four, and Five: June 2014–August 2016

The events ii, iii, and iv were repeated. In Cycles Three, Four, and Five the observations shifted to the contributing schools where the school teachers became part of the existing STAG team. Audio and video data were collected in the same way to Cycles One and Two. We then built on the findings in Cycles One and Two to explore, in collaboration with the New Entrant and Year 1 teachers, the opportunities to tell and re-tell stories, and included families and home languages, in a school classroom. Mediating resources—materials and ICTs that were effective in the early childhood centre—were discussed with school teachers and sometimes found to be used in the school situation, creating consistency between the two contexts.

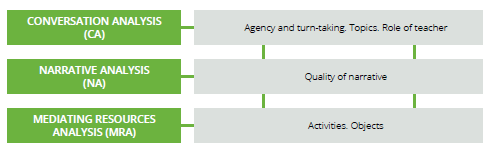

There were three layers of data analysis: Conversation analysis, Narrative analysis, and Mediating resources analysis.

Conversation analysis

Conversation analysis (CA) is a branch of ethnomethodology which investigates the everyday verbal and nonverbal exchanges between people in detail in order to find the systematic ways that they accomplish daily activities. Empirical research into everyday interactions through the use of CA revealed the turn-taking sequences of communication between members of society through a first pair part (FPP) and second pair part

(SPP) which mark an initiation of an interaction (FPP) and a response to that initiation (SPP) (Sacks, Schegloff, & Jefferson, 1974). People co-construct interactions with each other through these mundane turn-taking sequences, and social organisation unfolds through verbal and nonverbal orientation to specific things and not to others in the production of these interactions. A shared understanding, or intersubjectivity, between members is essential during the turn-taking process in order for the interaction to develop, and a breakdown in intersubjectivity is noticeable through the call for conversation repair (Schegloff, 1992). Story-telling is an area of interaction which has been investigated using CA where the structure of a story-telling episode was found to be an interactive process whereby the teller has an extended turn at talk whilst the receiver of the story marks their understanding that a story is being told by withholding their chance to speak (Mandelbaum, 2013). A CA approach to investigating the features of story-telling provided a good insight into how stories were produced in early childhood and school settings, and the role of the teacher in supporting children’s story-telling in turntaking, systematic ways.

The story-telling footage was transcribed and analysed using CA (Sacks, 1992) in order to reveal the turnby-turn verbal and nonverbal exchanges between the participating teachers and children, and peer–peer interactions. This approach provided the ‘zooming in’ on the interaction, explanation, or assisted story-telling activity. These detailed turn-taking sequences also revealed the broader social organisation processes evident during the interactions and so added a depth of understanding in informing learning and teaching. CA therefore complemented and supported the wider context of the whole project; hence our combined conversation, narrative, and resource analysis approach.

Narrative analysis

Narrative researchers typically focus on narrative form (structure), content (plot, characters, temporal factors, etc.), and whether stories are told using a first- or third-person orientation (Bamberg, 2012). Our method allowed us to gather examples of the stories children tell in structured and spontaneous storying activities in order to explore both their structure and quality. The data were interrogated for narrative content, including the introduction, description, and positioning of characters (through words, gesture, or movement), and orienting information: the continuity of events, references to consequences and (implicit) causation, and features that located the story in a particular place. Other features were noted too: for example, how children drew upon mediating tools as they told stories and how stories introduced ‘Trouble’ to keep the story-line going (Bruner, 2002). The final aspect of our narrative analysis introduced quantitative measures of story quality and involved an adaptation of Reese, Sparks, and Suggate’s (2012) method. Narrative analysis offered opportunities for ‘zooming out’ on the wider cultural purpose or story.

Mediating resources analysis

The question of how story-partners and mediating tools figure in children’s narrative competence was explored. Connecting these analyses together were the mediating ‘tools’: story exemplars; book-making and story-making opportunities; and materials, information communication technology (ICT), and other mediating resources that teacher and university researchers recognised during the project. The project also explored the ways in which home languages contributed to language, narrative, and literacy competencies in the early years—in early childhood provision and in school. The influence of the physical place was important too: the assumption here being that children construct learning through participation, an alternative to the notion that learning is unproblematically ‘transferred’ from one place to another. We were interested in how language competence and early literacy might be ‘re-contextualised’ (Van Oers, 1998) or ‘propagated’ (Beach, 2003) from one place (early childhood setting) to another (school), and the role in this process of mediational resources. The category of mediating resources described as ‘boundary objects’ (mediating resources that crossed ‘boundaries’ between places and people: see Carr et al., 2012), was of particular interest. The following figure outlines the analytical approaches we used, and how they work together.

Selected findings

Our findings have emerged from the everyday interactions that our participating children engaged in during their last year at kindergarten and first 18 months at school. As such, the findings from this project add new information about the opportunities for story-telling in children’s natural everyday experiences, the ways in which specific types of story-telling promote key learning opportunities, and how these opportunities can be strengthened by teachers. The key findings identified and explored further here are: 1) the value of learning stories for story retell; 2) the affordances of mediating resources in supporting story-telling; 3) conversational strategies that encourage story-telling; and 4) observed links between storying and early literacy.

Finding 1: The value of Learning Stories for story retell

From: Reese, E., Gunn, A., Bateman, A., & Carr, M. (2016, November). Telling stories about Learning Stories. Paper presented at the New Zealand Association for Educational Research conference, Wellington.

Learning Stories are narrative assessments of children’s learning. This way of documenting learning recognises that each child learns at their own pace with people, places, and things, and through responsive and reciprocal relationships with others (Carr & Lee, 2012). Stories are written about a learning event that a child has achieved, and these stories are collated as a book for the child and their family to treasure.

The sharing phase of Learning Stories and how teachers tell stories with children about their Learning Stories was particularly interesting in our video footage, and helped in answering the research questions regarding: What storying opportunities exist in early years settings and how do mediating resources work to support children’s storying?

During our video recording we captured interactions between children and teachers where they were sharing and re-telling stories from Learning Stories as naturally occurring practice, often in early childhood settings and less commonly in school. The re-tell experiences provided us with the opportunity to explore the types of conversations that occurred during these everyday pedagogical events. We invited teachers to share a Learning Story with each of the participating children and have them re-tell the story in their own words. We were then able to map the variation in conversations about Learning Stories and to assess potential benefits for children’s learning.

Across two kindergartens, we videotaped eight teachers interacting with 11 children over their Learning Story. Most children participated in two interactions with different teachers for a total of 22 interactions. We transcribed the interactions and then coded them for orientation to see if the teacher adopted a book-reading or a reminiscing orientation. A book-reading orientation was marked by the educator reading the stories to the child, accompanied by questions and comments about the photos. A reminiscing orientation was marked by the educator asking the child questions about the past event depicted in each Learning Story, with a focus on what happened. Of the 22 Learning Story interactions, eight were characterised by a book-reading orientation; seven by a personal narrative orientation; and six by a mixture of the two orientations (one interaction could not be coded because of its brevity). Reminiscing orientations were associated with greater engagement on the part of the child and with a higher quantity and quality of speech from the child compared to book-reading orientations.

We are now analysing the conditions under which teachers adopted these different orientations for children, which holds implications for the use of Learning Story re-tell in both early childhood and school settings. Learning Stories are an integral aspect of New Zealand’s approach to early childhood pedagogy, and from this project we now see the values they hold for initiating story re-tell in schools too. Teachers already know the assessment potential of Learning Stories, and we see from this project that ‘revisiting’ Learning Stories, especially as a springboard for reminiscing, offers another opportunity for supporting children’s oral language development. We hope these findings will help early childhood and school teachers realise the full potential of ‘revisiting’ Learning Stories to support children’s oral language development. Thus the learning potential of Learning Stories is not over when pasted or posted in the profile book.

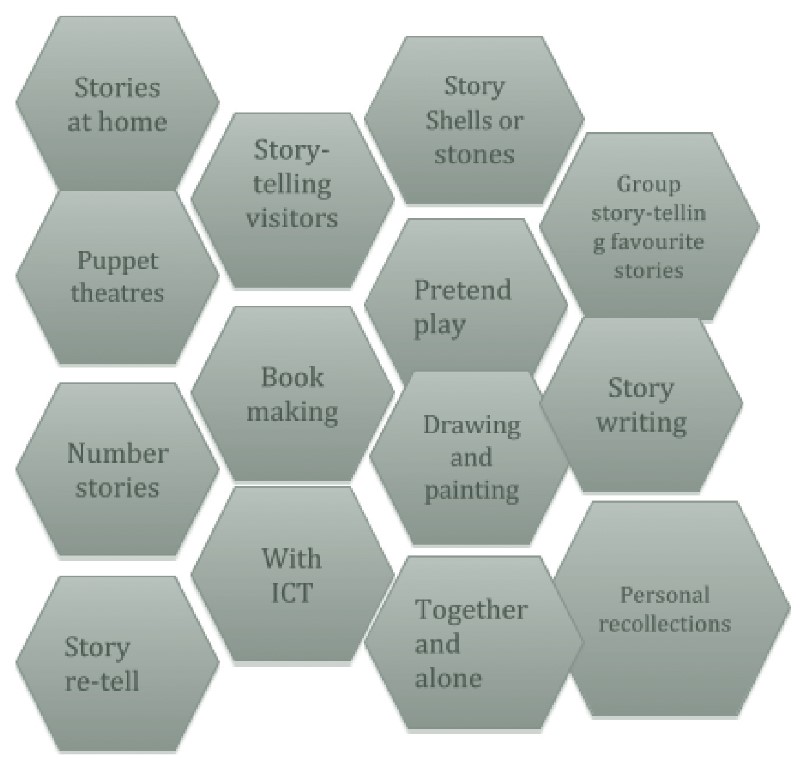

Finding 2: The affordances of mediating resources in supporting story-telling

From: Bateman, A., Carr, M., & Gunn, A. (2017, in press). Children’s use of objects in their storytelling. In C. Hruska & A. Gunn, (Eds.), Interactions and learning: Interaction research and early education. Singapore Springer.

Mediating resources encouraged children’s story-telling in everyday situations in both kindergarten and in the first 18 months of school. People were key to making the material resources work as story-telling opportunities. The availability and levels of engagement from teachers and peers helped to co-produce story-telling and literacy practices in structured and informal ways. We identified the following two material or environmental factors relating to objects from our video footage:

- Spaces: provide and encourage opportunities for structured and informal narrative story-telling and literacy learning.

- Objects: the availability of objects such as story shells, iPads, characters in iPad applications, play dough, puppets, book-making and binding, drawing, painting, swings, and balls worked as physical props to support story-telling and the development of a narrative in children’s stories.

Children were found to be using an object or objects to tell a story in different ways: as a companion to the author, as characters in a systematic storyline for an audience, and to construct a storyline which included trouble. At the same time, the children’s capacities for imagination were demonstrated through their unique use of the objects. These stories were constructed and imagined in spontaneous ways—and the objects did some of this work through offering inspiration.

Our analysis has shown how the sequences of action that are essential to building and telling a story are observable through the children’s use of objects. The children orient to objects in such ways that each child has to respond to the prior talk or actions of their play partner, systematically building the storyline in order to co-produce a successful story episode. The story is never the child’s alone and children’s quick reading of the interactions between themselves, people, and objects in specific places combine to co-produce the story. Within children’s stories the chosen objects are sometimes uncontrollable and unexpected. As a consequence we see evidence of children’s flexibility in their story-telling to accommodate the spontaneous actions of their storypartners. However, sometimes the objects are totally predictable and such objects support children’s entry into storying as they take up cultural tropes which they may or may not bend to their own devices. The intelligent ways in which children use the objects in their immediate place has been observed in the story-telling events we videoed. The effect on narrative competence has been seen as we have observed children’s complex, rapid, and fluid decision making as they respond to the unexpected ways the objects interact with them in the world.

By understanding further the affordances of mediating resource objects to young children’s story-telling we appreciate how even so-thought inanimate objects may directly complicate and support children’s story-telling.

Finding 3: Conversational strategies that encourage storytelling

From: Bateman, A., & Carr, M. (2016). Pursuing a telling: Managing a multi-unit turn in children’s storytelling. In A. Bateman & A. Church (Eds.), Children and knowledge: Studies in conversation analysis (pp. 91–110). Singapore: Springer.

During our video recording of story-telling episodes the children were observed managing their story beginnings and endings with narrative strategies involving the utterances “Once upon a time” and “The end”, whereas telling the middle part of the story seemed somewhat problematic, rarely involving an extended turn of talk. The progression of the story-telling was observable as a collaborative project involving joint-attention where the teacher is observed pursuing a telling with verbal and nonverbal prompts. The teacher was key in supporting story-telling here, using strategies such as requesting more information about the story, leaving long pauses, and utilising the affordances of the seashell objects, all of which are taken up by the children. More experienced children who had been attending the kindergarten for a long time were often well versed in the art of story-telling and often informally ‘modelled’ story-telling for the less experienced or less confident children. During the first year of videoing (2014) we noticed that the children who were the ‘listeners’ when we first began the study were keen to participate and contribute a story by the end of the year.

Early childhood teachers often initiated a story-telling activity by talking about possible ways to start a story, asking who could start a story, and giving story-telling start strategies such as “Once upon a time”. The use of gestures such as getting down to the child’s level and holding children’s gaze worked to keep the children interested in the story activity. Pauses were also used by the teacher to allow a ‘turn allocation space’ for the children to advance a story they were telling where teachers avoided leaping in too soon to prompt talk and hijack the thinking time. The teachers were observed pursuing a story-telling by making explicit reference to the story features that the child has already told by attending to characters or the actions they were doing; the question “What happened?” was also often used by teachers to incite discussion around a topic. These types of prompts helped children to elaborate on a specific feature of a story, scaffolding the telling by prompting a narrow focus for the story. The prompts around specific characters and their actions afforded opportunities for children to embellish story ideas, often tying characters and objects together to make an interesting story.

The final part of story-telling sequences that had to be collaboratively managed was the ending of stories. Teachers were observed mobilising the topic of story endings with the children to make it noticeable as an important part in the story-telling process. Discussions with the teachers during the filming process revealed that a strategy had to be employed for marking the end of the story-tellings as it could not be assumed that the children had finished their tellings when an extended pause was evident, due to pauses being a common part of each telling. The teachers further explained that they did not want to disempower the children by closing their story for them prematurely when they felt the story had come to an end: they wanted the children to have autonomy over this action. The children demonstrated their knowledge of ‘the end’ as being an important aspect of the story-telling process as they managed their story endings competently by using ‘the end’ at the end of each of their stories.

To help support children to tell the middle (extended ‘multi-unit’) part of the story, it was attended to as a collaborative project between the children and teacher. The extended multi-unit part of the story was progressed by the teacher who pursued the telling by using verbal prompts such as “Keep going”, and nonverbal gesture such as smiles and nods of the head. The children responded positively to these prompts, as they progressed their story further when these prompts were used. The children demonstrated their competence in creative thinking when they tied the characters to objects with actions, and the recipient design of the telling was observable in the way that the children made their stories interesting and exciting, keeping the audience engaged. These conversational strategies provide insight into how story-telling practices are managed in an early childhood setting, where beginnings and endings are performed in specific ways and multi-unit tellings are facilitated by objects.

Finding 4: Links between storying and early literacy

From: Bateman, A. (2017, in press). Ventriloquism as early literacy practice: Making meaning in pretend play. Early Years: An International Research Journal.

Young children use ventriloquism “the act children engage in when they make objects take on a specific character in their pretend play” (Bateman, 2017, p. 3) to co-produce impromptu story-telling in kindergarten and their first year at primary school. The importance of opportunities for children’s oral formulation of characters in these pretend play episodes is identified, where this activity can be linked to later written literacy practice where children will be required to imagine and formulate characters in their written stories. Emerging literacy skills can also be seen in these pretend play ventriloquism episodes as the children represent one object (for example, a plastic toy) for another (a living being with its own persona), requiring meaning-making, which can be linked to emerging literacy through symbolic representation. The paralinguistic resources that children use to portray a specific type of character through voice quality are also significant in the co-production of meaning-making in spontaneous story-telling in early childhood and in school.

The activity of ventriloquism was observed in one of the children, Isla, as she engaged in pretend play with characters on the iPad, an activity that was promoted in early childhood and in school, providing consistency between the two contexts. During this activity, Isla demonstrated her competence at orally formulating characters in a story-telling, not through a narrative description around who the character was and what they were doing, but through the act of ventriloquism as she gave each character a specific voice that projected them as being of a certain personality. Through these vocal changes Isla competently created a storyline involving many different characters that engaged in interesting activities.

For the children who had the opportunity to engage in pretend play through collaborative ventriloquism in early childhood and school, they were observed changing their voice prosody, and gazed in the direction of the speaking object, rather than the speaking child. The successful act of ventriloquism was realised in this way where the story partners attended to the toys and objects as though they were real, and had secured the attention of the children and their right to speak through their gaze. By watching the object as it speaks, the children’s direction of focus demonstrates that they are engaged in a spontaneous interaction with that object as they take turns of talk together to co-produce the story. Characters were often played as funny, where they got into trouble and needed rescuing or to solve some problem—all aspects of a ‘good’ story identified by Bruner (2002).

The ways in which the children co-construct a story through ventriloquism in both school and early childhood contexts, with or without the use of an overarching narrative, is a skill that requires fast-paced thinking in order to be responsive to their play partner’s actions in a relevant and timely manner that does not slow down the flow of the storyline, whilst also adding an impromptu contribution that could take the story in any new direction. The findings from this project regarding the activity of ventriloquism suggests that, when given the opportunity to engage in pretend play with open-ended resources such as puppet theatres, playdough, and iPads, children learn to participate in complex meaning-making activities in playful ways, building coherent and systematic storylines that can be seen as early literacy practices. Through providing these open-ended resources in both early childhood and school settings, teachers are providing opportunities for these early literacy practices that are sustainable in different environments.

Major implications

Impact on practice and learning

Throughout our three-year project we have been exploring the opportunities for children’s story-telling in a kindergarten and contributing schools. We have found that story-telling happens in many places within early years classrooms and takes the form of both imaginative story-telling and story-telling in response to teachers’ planned learning experiences. It is supported by resources, the structure of the day—including whether and when teachers plan time for children to engage in open-ended play with resources and materials. It is also encouraged by the ways the story-tellers and their audiences interact. We have taken a very broad approach to story-telling in this research and we have seen many different examples of children’s story-telling being well supported at kindergarten and school.

The rich examples of story-telling that we have collected over the three years are now being compiled in a resource for teachers in both early childhood and the beginning of primary school (Bateman, Carr, Gunn, & Reese, forthcoming). The resource includes several examples from our collection of children’s stories, to share and to talk about with families and teachers. The aim is to raise awareness of opportunities for story-telling, and how best to support story-telling in everyday teaching practice.

There were a number of aspects of the research design and the findings that had an impact on practice and learning, and the strategies for encouraging story re-tell provide some ideas for teachers and families who were not in the study.

1. For families

All of the families who took part in the STAG (story-telling advisory group) meetings were intrigued by the notion that story re-tells contribute to literacy development and enjoyment. At STAG meetings they were recounting the ways and places that their children were re-telling or constructing oral stories for the family’s enjoyment. Some examples of their comments in the early meetings were:

- One of the Mums (STAG May 2014): They do love their portfolios. And other people’s. They like to swap. My oldest son’s eight and he still enjoys sharing his kindergarten Learning Stories! Yeah and he likes sharing them with his sisters as well. He still has fond memories and likes the photos. It’s quite a difficult skill for children to learn, the story re-tell. You’re always trying to get more out of them, or they give you far too much—just give me the five main bits! It’s quite a difficult skill.

- Another Mum (STAG May 2014): He [child] got me into this crazy dress up thing—he’s Wolverine—he goes into the kitchen and puts forks between his fingers and I have to be Spiderman and catch him to get him to bed! He doesn’t like sitting down with me to read a book. So we have to play, and then he makes his own stories.

- (STAG Nov 2014): During a discussion around how children make storybooks in everyday practice, one of the Mums had the following conversation with a kindergarten teacher:

Mum: It’s really amazing. He did it [book-making] at home as well.

Teacher: When the children are taking books home are they reading them?

Mum: Yeah. Not the words, but the pictures.

Teacher: These are becoming their first readers, just like their portfolios are an artefact.

Mum: I like to put the books away, but they want to read them. Everyone who comes to our house, he likes to show the book [he made] to them. He’s very proud of it!

Continuing the discussion on children making their storybooks, one of the Dads talked with the university researchers about the value of the books:

Dad: She tells me how the story goes. What Cinderella does.

Researcher: Does she tell a different story every time she gets it [her story] out?

Dad: No, she sticks to the same story. She gets me to tell it!

Researcher: Have you had to tell it a lot?

Dad: Yes. Before bed. Or getting ready to come to school. ‘Can I have this story?’ Also her drawings have really improved too since she started [book-making].

2. For early years teachers

The kindergarten teachers were seizing more opportunities to encourage the children to story-tell, and the increase in length and complexity of the stories by children who began with little confidence and competence was apparent:

STAG 4 Nov 2015: (New Entrant teacher): I think giving the children confidence, to have a go as well, and there isn’t any right answer or wrong answer when it’s story-telling. I mean it can be whatever you want it to be, you can let your imagination run wild. So having children sometimes very afraid to speak up, for fear of doing it wrong, and be embarrassed in front of their peers, and say ‘Oh gosh, you’ll laugh at me ‘cause I said that’.

STAG 4 November 2015: (Kindergarten teacher): It’s quite an important topic on oral literacy here and we make that visible to parents through the children’s Learning Stories, because obviously as a parent you want your child to be able to read and write, and so they often think literacy is writing your name. So, through our Learning Stories we are broadening the parents’ understanding of what literacy is—we’re really celebrating children’s oral literacy and explaining to them how this is going to support them to be a reader and a writer in the future.

Early years school teachers (New Entrant and Year 1) were typically beginning the day by hearing children ‘reading’ the stories that they had sent home the evening before for reading to their child by a family member.

They recognised this as a reading activity; they were interested that we also saw it as a valuable storying activity (many of the early ‘readers’ in the New Zealand education system tell very captivating stories, often written by well-established children’s writers). They are often funny as well, adding an enjoyable emotional element to a literacy event. One of our New Entrant teachers made the following important point:

STAG November 2015: (New Entrant teacher): It’s about experiences, providing them with those experiences, because I know that Ready to Read is looking at trying to provide those [particular] reading books. You know, that give them those rich sorts of experiences. The last one I trialled … invites you to have that rich discussion before you read the book, and get them to talk about what they already know about them and things like that. So they’re trying to move that way.

Emphasising the value of mediating resources, we invited the school teachers in Cycle 2 to think of ways to encourage children to tell stories in ‘everyday’ activities in the classroom. They were interested in the research behind our invitation, and very willing to repeat activities and to invent new ones. These included puppet shows, sharing stories at a dough table, block activities that included group negotiation about the story, painting, and drawing.

STAG November 2015: (New Entrant teacher): We’ve been having a reporter card at the moment for our oral language table, two or three times a week. We put a little string with a reporter card on, they have to take it home [knowing] ‘I have to do my show and tell tomorrow, I am a very important person with this string on, with it on my neck, and you’re all going to sit and look at me, so I’m the teacher now, I’m going to show you about my toy!’ And it’s wonderful to actually hear them come with their story.

The limitations of the project

One of our findings (Finding 1) identified that the ‘reminiscing’ book-reading orientation created a greater engagement: a higher quantity and quality of speech. Unfortunately, we did not have time to explore with the teachers as to whether they could change the coding of the re-tells for orientation. It would have been interesting to see whether the teachers used this orientation with the more linguistically able children, or whether this orientation enhanced the linguistic ability and interest. We assume the latter, and are planning more research with larger cohorts to find out.

Conclusion: A patchwork of story-telling

Our video recordings were taken over three years, beginning in the last year of ECE and ending at the second year of school. During the recording we found that story-telling occurred in many places. Not only did specific contexts afford different story-telling opportunities, resources and relationships support story-telling too. We could see a patchwork of story-telling being supported by approaches to teaching and learning in all early years settings.

By learning more about the stories children tell in their early years settings, this research project was designed with an overall purpose to improve literacy outcomes in early years settings, with a particular emphasis on nondominant and low-income communities, where literacy levels are currently inequitable. The narrative analysis, the analysis of conversation strategies, and the mediational resources analysis has enabled us to theorise and test ideas about how we might support literacy and narrative learning in the early years and to co-ordinate design-based strategies across the transition to school and the first two years of schooling. In bringing families, children, and teachers together in joint conversations we traced over time the complexity of learning outcomes in this domain of interest. By focusing on a key aspect of oral language learning (an aspect that has implications for later literacy competence), we anticipate that these findings will assist those teachers who struggle to plan meaningfully for children’s language learning during those early months of school. Noticeably, narrative was observable in explanations of play or work, and in conversations about important events in children’s lives (for example, birthday parties or family events). Narrative underpins teachers’ activity when they’re working on specific literacy and numeracy tasks (for example, inventing a story that can be reproduced as a sentence for writing, or a number story being told to represent an equation). It holds children’s free play together as well as being evident as teachers bring entire classrooms of children together to work with each other in collaborative story-telling. Our aim of this project was to help develop storying strategies with and for teachers to support children’s early narrative and literacy. We hope that these findings have offered a significant contribution to this important national and international arena.

References

Bamberg, M. (2012). Why narrative? Narrative Inquiry, 22(1), 202–210.

Bateman, A. (2011). To intervene, or not to intervene, that is the question. Early Childhood Folio, 15(1), 17–21.

Bateman, A. (2012). Pedagogical intersubjectivity; Understanding how teaching and learning moments occur between children and teachers through everyday conversations in New Zealand. Wellington: NZCER.

Bateman, A. (2013). Responding to children’s answers: Questions embedded in the social context of early childhood education. Early Years: An International Research Journal, 33(2), 275–289. doi:10.1080/09575146.2013.800844

Bateman, A. (2017, in press). Ventriloquism as early literacy practice: Making meaning in pretend play. Early Years: An International Research Journal.

Bateman, A., & Carr, M. (2016). Pursuing a telling: Managing a multi-unit turn in children’s storytelling. In A. Bateman & A. Church (Eds.), Children and knowledge: Studies in conversation analysis (pp. 91–110). Singapore: Springer.

Bateman, A., Carr, M., & Gunn, A. (2017, in press). Children’s use of objects in their storytelling. In C. Hruska & A. Gunn (Eds.), Interactions and learning: Interaction research and early education. Springer.

Bateman, A., Carr, M., Gunn, A., & Reese, E. (forthcoming). A resource for early narrative and literacy: From early childhood through to school.

Bateman, A., & Waters, J. (2013). Asymmetries of knowledge between children and teachers on a New Zealand bush walk. Australian Journal of Communication, 40(2), 19–32.

Beach, K. (2003). Consequential transitions: A developmental view of knowledge propagation through social organisations. In T. Tuomi-Gröhn & Y. Engeström (Eds.), Between school and work: New perspectives on transfer and boundary-crossing (pp. 39–61). Amsterdam: Pergamon.

Bruner, J. (2002). Making stories: Law, literature, life. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Carr, M. (2001). Assessment in early childhood settings: Learning Stories. London: Sage.

Carr, M. (2011). Young children reflecting on their learning: Teachers’ conversation strategies. Early Years, 31(3), 257–270.

Carr, M., Clarkin-Phillips, J., Beer, A., Thomas, R., & Waitai, M. (2012). Young children developing meaning-making practices in a museum: The role of boundary objects. Journal of Museum Management and Curatorship, 27(1), 53–66.

Carr, M., & Lee, W. (2012). Learning Stories: Constructing learner identities in early education. London: Sage.

Clay, M. (1991). Becoming literate: The construction of inner control. Auckland: Heinemann.

Colbert, J. (2006). New forms of an old art—children’s storytelling and ICT. Early Childhood Folio, 10, 2–5.

Dickinson, D. K., McCabe, A., Anastasopoulos, L., Peisner-Feinberg, E. S., & Poe, M. D. (2003). The comprehensive language approach to early literacy: The interrelationships among vocabulary, phonological sensitivity, and print knowledge among preschool-aged children. Journal of Educational Psychology, 95, 465–481.

Griffin, T. M., Hemphill, L., Camp, L., & Wolf, D. P. (2004). Oral discourse in the preschool years and later literacy skills. First Language, 24, 123–147.

Gunn, A. C., & de Vocht van Alphen, L. (2011). Seeking social justice and equity through narrative assessment in early childhood education. International Journal of Equity and Innovation in Early Childhood, 9(1), 31–43.

Mandelbaum, J. (2013). Storytelling in conversation. In J. Sidnell & T. Stivers (Eds.), The handbook of conversation analysis (pp. 492–507). West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell.

McDowall, S., Davey, R., Hatherly, A., & Ham, V. (2012). Literacy and e-learning: Mining the action research data, Summary. Wellington: Teaching and Learning Research Initiative.

Morton, M., McMenamin, T., Moore, G., & Molloy, S. (2012). Assessment that matters: The transformative potential of narrative assessment for students with special education needs. Assessment Matters, 4, 110–128.

Ministry of Education. (1999). Report of the literacy taskforce. Wellington: Author.

Ministry of Education. (2004/2007/2009). Kei tua o te pae, assessment for learning: Early childhood exemplars. Wellington: Learning Media.

National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Early Child Care Research Network. (2005). Pathways to reading: The role of oral language in the transition to reading. Developmental Psychology, 41, 428–442.

Reese, E., & Fivush, R. (2008). The development of collective remembering. Memory, 16(3), 201–212.

Reese, E., Gunn, A., Bateman, A., & Carr, M. (in preparation). Telling stories about learning stories: The value for children’s narratives of revisiting learning stories. To be submitted to Journal of Early Childhood Literacy.

Reese, E., Gunn, A., Bateman, A., & Carr, M. (2016, November). Telling stories about Learning Stories. Paper presented at the New Zealand Association for Educational Research conference, Wellington.

Reese, E., Leyva, D., Sparks, A., & Grolnick, W. (2010). Maternal elaborative reminiscing increases low-income children’s narrative skills relative to dialogic reading. Early Education and Development, 21, 318–342.

Reese, E., & Newcombe, R. (2007). Training mothers in elaborative reminiscing enhances children’s autobiographical memory and narrative. Child Development, 78(4), 1153–1170.

Reese, E., Sparks, A., & Suggate, S. (2012). Assessing children’s narratives. In E. Hoff (Ed.), Research methods in child language: A practical guide (pp. 133–148). Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

Reese, E., Suggate, S., Long, L., & Schaughency, E. (2009). Children’s oral narrative and reading skills in the first 3 years of reading instruction. Reading and Writing, 23, 627–644.

Sacks, H. (1992). Lectures on conversation (Vols. I & II). Oxford: Blackwell.

Sacks, H., Schegloff, E. A., & Jefferson, G. (1974). A simplest systematics for the organisation of turn-taking for conversation. Language, 50(4), 696–735.

Schegloff, E. A. (1992). Repair after next turn: The last structurally provided defense of intersubjectivity in conversation. The American Journal of Sociology, 97(5), 1295–1345.

Sénéchal, M., & LeFevre, J. (2002). Parental involvement in the development of children’s reading skill: A five-year longitudinal study. Child Development, 73, 445–460.

Snow, C. E., Burns, M. S., & Griffin, P. (1998). Preventing reading difficulties in young children. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

Suggate, S. P., Schaughency, E. A., & Reese, E. (2012). Children learning to read later catch up to children reading earlier. Early Childhood Research Quarterly. doi:10.1016/j,ecresq.2012.04.004

Van Oers, B. (1998). The fallacy of decontextualization. Mind, Culture and Activity, 5(2), 13–142.