1. Introduction

Whaia te iti kahuranhi

Strive for the things in life that are important to you

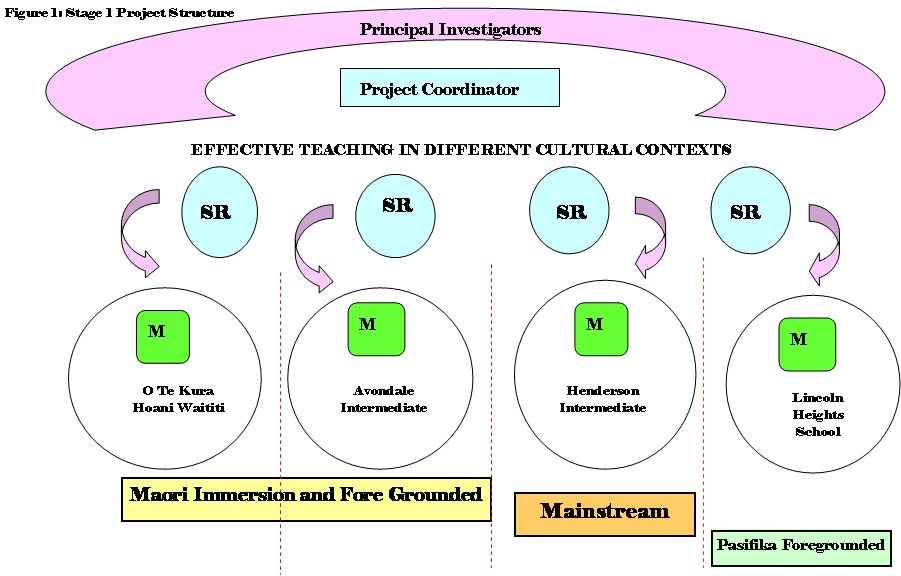

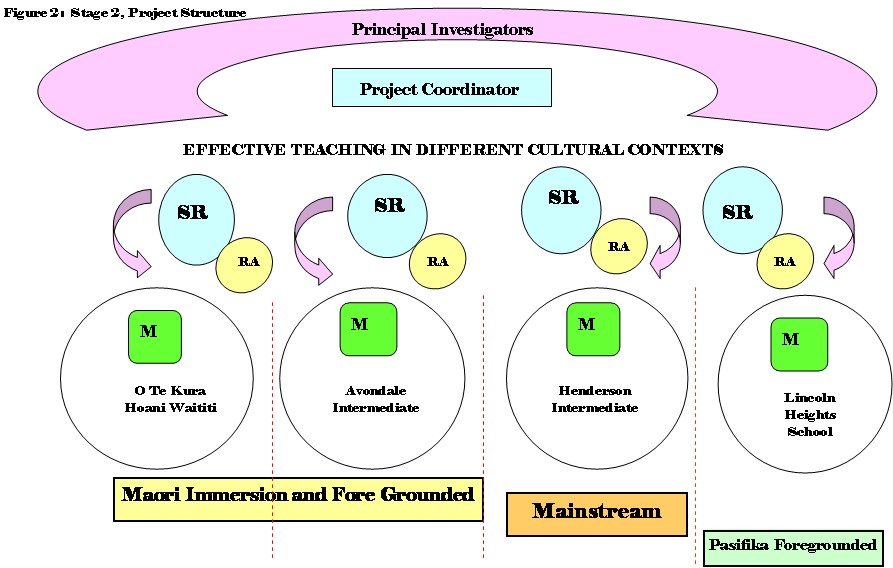

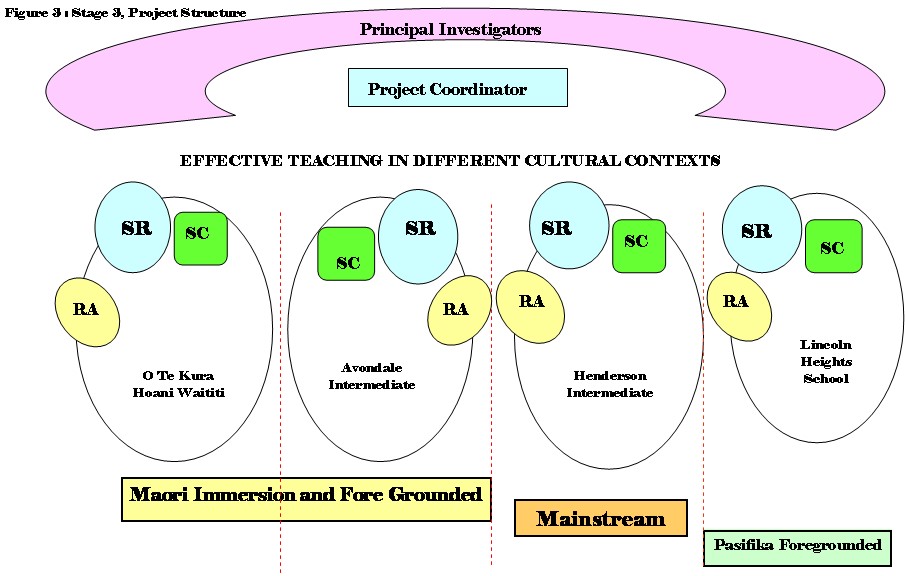

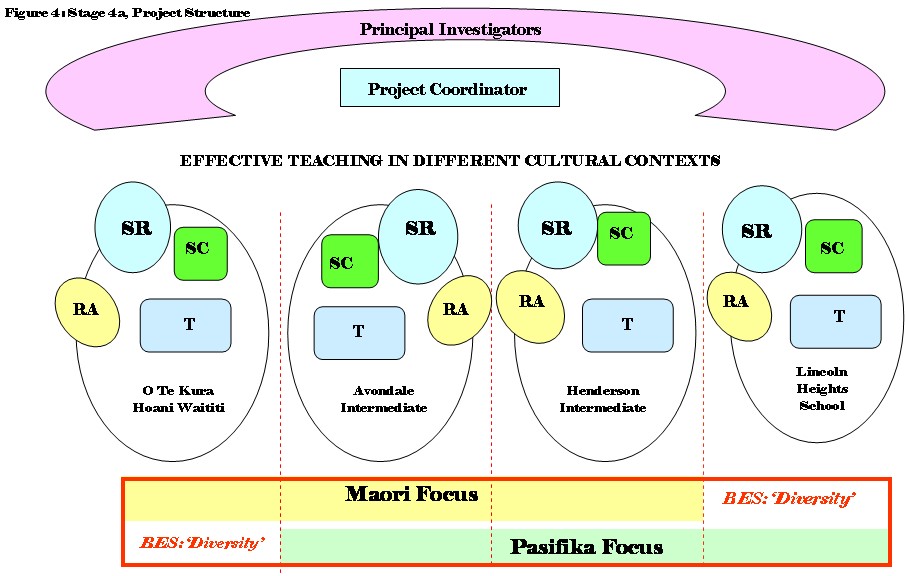

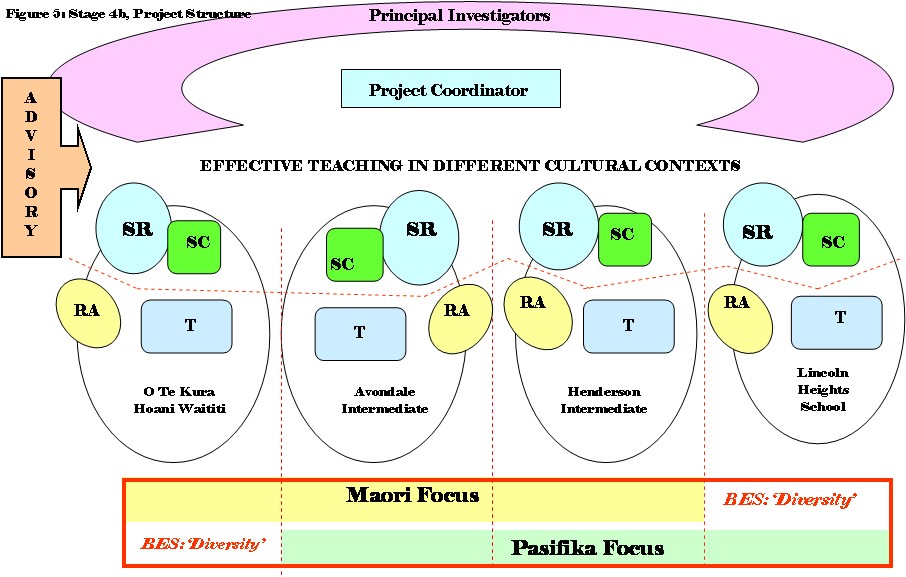

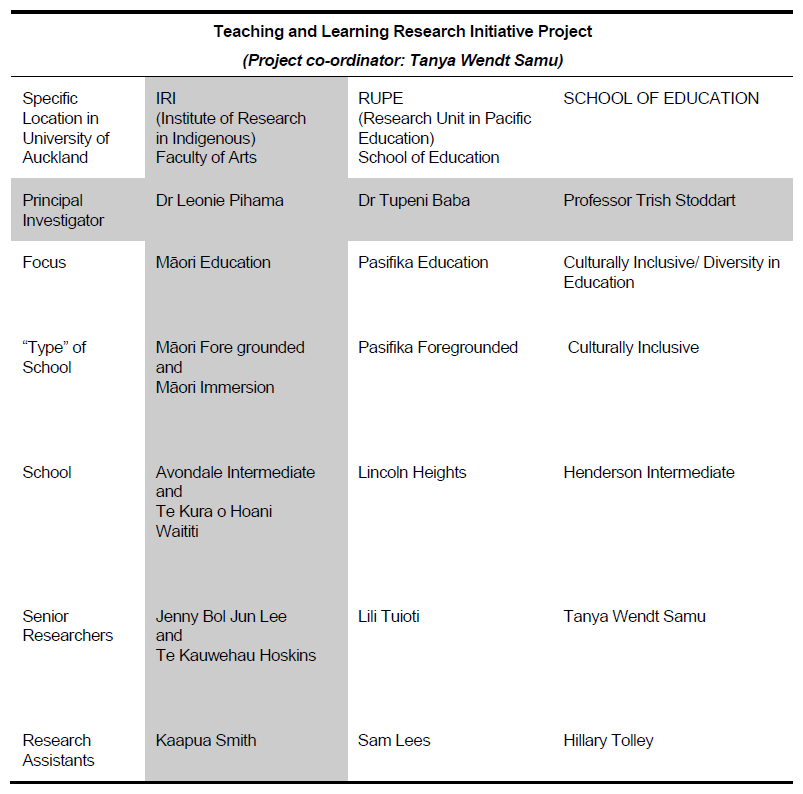

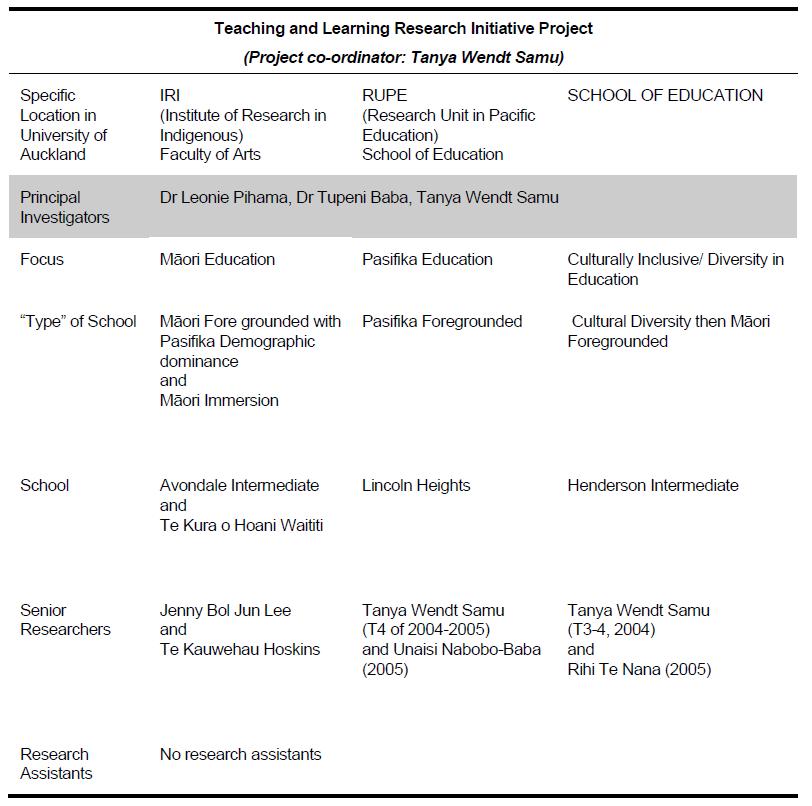

This research project was developed as a part of the Teaching and Learning Research Initiative (TLRI) tender process that is managed by the New Zealand Council for Educational Research (NZCER). The project began with a collaborative team of Māori, Pasifika and Pākehā researchers, brought together with the intention of working across four different school contexts that included kura kaupapa Māori, schools in which Pasifika and Māori were culturally in the foreground and mainstream[1] sites. Unanticipated changes to the composition of the research team occurred during project implementation and had a significant impact—these are detailed and discussed in section 2, part 2 and section 5. With respect to the four different school contexts, as researchers established relationships and deepened their knowledge, it became clear that the original categorisations used in the proposal did not reflect the realities. This is mapped out in section 4.

Aims and objectives

The project proposal noted the key aim of the research project as being:

to analyse a range of teaching practices for Māori and Pasifika students in Auckland city schools and conduct a comparative analysis of the teaching and learning of these students in classrooms that focus on Māori and Pasifika language and culture with classrooms where instructional practices focus on mainstreaming, and there is no, or limited input, of Māori and Pasifika language and cultural instruction. (Stoddart, Pihama, & Baba, 2003, p. 2)

Furthermore, the research sought to extend the current understanding of effective generic teaching practices by identifying the context-specific and general principles of effective teaching practice for Years 7 and 8 Māori and Pasifika pupils.

It became evident that the school that had originally been selected as the “mainstream” context provided a Māori bilingual unit which had a significant input into the overall school environment. The research began with working with a syndicate of Year 8 teachers that included the teachers of the Māori bilingual unit. The research focus for that school moved to one of working with the Māori bilingual teachers within the unit—after an initial series of data gathering activities with non-Māori teachers of the syndicate. As such, there was a shift in focus in that research case study from a study of mainstream generic programmes to a study of an approach that placed Māori in the foreground.

Prior educational research has tended to focus either on the relationship of social, cultural, and linguistic background factors to student educational performance or on general teaching strategies for teaching school subjects to all students (Darling-Hammond, 1996). From Māori, Pasifika, and social and cultural theoretical perspectives, however, these factors cannot be separated (Coxon, Anae, Mara, Samu, & Finau, 2001; Helu-Thaman, 1999; Hohepa, Smith, Smith, & McNaughton, 1992; Phillips, McNaughton, & McDonald, 2001; Pihama, 1996; Tharp & Gallimore, 1988; Vygotsky, 1978). There is increasing evidence that the integration of language, culture, and pedagogy are central to effective teaching and learning processes in school (Alton-Lee, 2003; Beecher & Arthur, 2001; Heath, 1982; Freedman & Daiute, 2001; Jones, 1991; Hohepa, Smith, Smith, & McNaughton, 1992; Nuthall, 1999; Stoddart, Pinal, Latzke, & Canaday, 2002). The calls are growing for a range of cultural approaches which allow for different ways of imparting knowledge.

Research questions

The original team of researchers proposed the following research questions:

- How do instructional practices and philosophy vary across four contexts: Te Kura Kaupapa Māori o Hoani Waititi Marae, in which students are immersed in Māori language and culture; “culturally foregrounded” schools, where there are focused programmes and curriculum for Māori and Pasifika students; and a “mainstream” school, where generic programmes are designed to meet the needs of all students?

- Which principals of practice are common to these contexts and which are context-specific?

- Are there differences in Māori and Pasifika students’ learning outcomes and motivation across the four contexts?

- How do Māori and Pasifika students and parents from the four schools view effective teaching practices and is there consistency between these perspectives and school philosophy and practice?

- How do teacher characteristics (knowledge of students’ language and culture; views of learners; personal political and pedagogical perspectives; personal cultural identity; and professional education and experiences) vary across the contexts? How do such characteristics influence individual teachers instructional practices?

- What is the influence of subject matter on the development of culturally and linguistically responsive teaching practices?

- How does school culture influence and support the development of culturally and linguistically responsive pedagogy?

When these questions were formed, prior to entering each of the schools and kura, the intention was to collect comparable data from each site. However, because the research sites were vastly different, in ways that were not anticipated before the researchers became more involved within each context, some questions were more relevant than others, particularly in a kura kaupapa environment.

The research team established one overarching key research question to guide the studies in each of the four schooling sites and clarify the emphasis in this research project:

To what extent is culture (Māori and/or Pasifika) embedded in the teaching and learning processes at the school, and how in turn does that contribute to the development of culturally and linguistically responsive pedagogy?

This broad question helped shape the way researchers approached the various research activities.

Their intentions were:

- To stay in line with a key purpose of the research, described in the proposal as identifying:

core principles underlying pedagogy that is culturally and linguistically responsive and to analyse how these principles are elaborated in classroom contexts that vary in the degree of emphasis placed on students’ language and culture—kura kaupapa Māori, in which students are immersed in Māori language and culture; culturally foregrounded where there are focused programmes and curriculum for Māori and Pasifika students; and mainstream where generic programmes are designed to meet the needs of all students. (Stoddart et al, 2003, p. 2)

Section 4 maps the knowledge and understandings gained in each school context in relation to this.

- to contribute to the literature. This outcome is provided as a comprehensive literature review in section

- to contribute to a wider research and academic agenda in regards to the building of research capacity that includes:

- the development of a cross-cultural, cross-disciplinary team of Māori, Pasifika and Pākehā scholars and practitioners who will collaborate to provide multiple lenses and perspectives on the integration of language, culture and teaching

- the mentoring and support of a group of emerging Māori and Pasifika scholars engaged in masters and doctoral programmes in the context of a large-scale empirical study

- the integration of research and practice, in the form of collaboration between researchers and practitioners informs both research and school policies and practice, and through the development of teacher education and curriculum resources.

Section 6 describes and discusses the outcomes related to capability and capacity building.

2. Research overview

E poto le Tautai a e se lana atu lama

The navigator is wise but can also be wrong

(Knowledge is never complete, there is always something more to learn)

Participating schools

The intention of this project was to carry out in-depth case study research in west Auckland as opposed to south Auckland. The main reason was that there had been limited research to date about Māori and Pasifika learners in settings:

- that focus on Year 8 learners (learners about to make the transition to secondary schooling— another specific area on which there is limited research)

- that are decile 3 (as opposed to the wealth of school-based research in decile 1 schools y that are located in west Auckland, as opposed to south Auckland (Waitakere city’s Pasifika populations are growing rapidly, ranking second highest in the Auckland region after the city of Manukau)

- wherein Māori and Pasifika learners make up significant-sized minorities in a culturally diverse student body.

It was intended that the project would include a kura kaupapa Māori in order to explore the relationship between culture and pedagogy in a context where it could be assumed that this did indeed exist in both philosophy and practice because of the unique historical development of the specific kura involved.

It was also the intention to approach schools fitting the general criteria outlined above that were known to be “good schools” (refer to section 3, part 3 and literature on the methodology known as “portraiture”). A number of “sources” were drawn on in order to identify four “good” decile 3 schools located in west Auckland with Year 8 learners. Ministry of Education data were used to create a list of possible schools, and senior colleagues in the university’s Faculty of Education and a former senior Ministry of Education official with specialist experience in Pasifika education projects were asked for their perceptions of schools fitting the general criteria. Members of the research team living in west Auckland drew on their general knowledge of wider community perceptions of schools on the list.

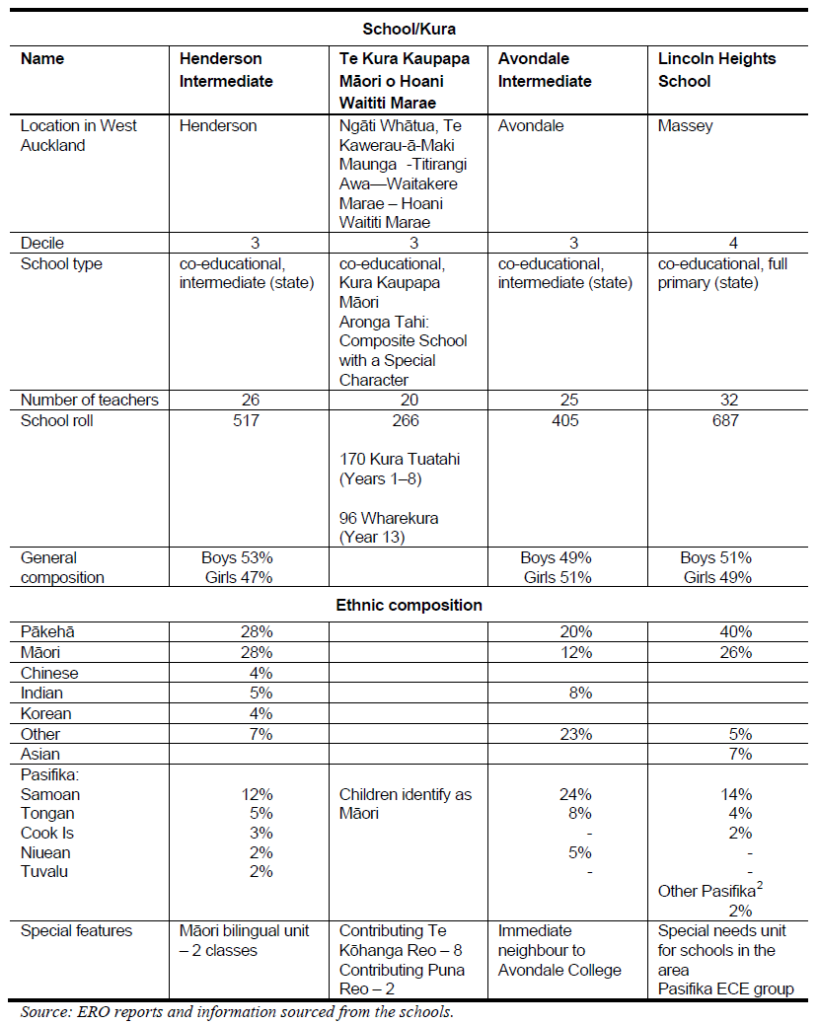

Four schools agreed to participate in the project: Henderson Intermediate; Te Kura Kaupapa Māori o Hoani Waititi Marae; Avondale Intermediate; and Lincoln Heights. Table 1 provides a comparative overview of the participating schools. Brief descriptions of each school are given below.

Henderson Intermediate

Henderson Intermediate had a school population of 517 students from a diverse ethnic community of which Māori and Pākehā comprise the two highest groups at 28 percent each. The ethnic breakdown for the balance is: Samoan, 12 percent; Indian, 5 percent; Tongan, 5 percent; Korean, 4 percent; Chinese, 4 percent; Cook Island Māori, 3 percent; Niuean, 2 percent; Tuvaluan, 2 percent; and “other”, 7 percent. The school has a decile 3 rating and a teaching staff of 26. Most of the students come from Waitakere city; however, some students travel from the greater Auckland region to attend this school. This is reflected in the increased enrolments the school has experienced in the past 24 months which include a significant number of “out of zone” enrolments.

The research reveals that the Māori bilingual teaching staff have similar philosophical and professional ideals in their teaching practices. They have chosen to teach in the unit because they are Māori and, as Māori teachers, consciously chose to teach in a designated Māori space. Within the bilingual unit, the teachers have a strong desire to nurture and support the development of their students’ Māori identity. The unit enables them to teach within a partial Māori language and related cultural practice that is held within a solid Māori world view structure. There is a strong philosophical notion amongst the teachers that they are the facilitators of the learning process and thus teaching and learning takes place on a number of relational levels—between the teachers, between the teacher and the student; and between student and student.

According to the teachers, the bilingual unit exists in a supportive wider school context. Strong leadership has been a significant factor in the acceptance, growth, and participation of the wider school with Māori knowledge, culture, and other related Māori initiatives. Since 2004, the teaching staff have received extensive professional development pertaining to Māori curriculum and the school has actively engaged in the development of Māori programmes.

Te Kura Kaupapa Māori o Hoani Waititi Marae

Te Kura Kaupapa Māori o Hoani Waititi Marae was established in 1985. As part of Hoani Waititi Marae, a pan-tribal urban-based marae in west Auckland, the kura was part of the vision and aspirations of the community for “mātauranga Māori motuhake” (“full autonomy and status for Māori knowledge and values”). The kura was considered an integral part in providing “birth-to death” marae-based education, and therefore is closely connected to the philosophies of the Hoani Waititi Marae.

As the first kura kaupapa Māori in New Zealand, this community-driven kaupapa Māori initiative began outside of the state-funded system. It was officially recognised at the end of 1989 when an amendment to the Education Act 1989, Part 12, section 155 legislated the establishment of kura kaupapa Māori as special character schools.

Today the kura provides for Year 1 to Year 13 students. With a current roll of 277, the majority (69 percent) of the children come from outside the local area (more than 3.5 km radius). Most of the children are graduates of 10 köhanga reo and puna reo in the local district. The kura is categorised as a decile 3 school, and the children identify as Māori. Pākehā and other ethnic groups can enrol. Tipene Lemon was appointed as principal at the beginning of 2005. Like Tipene, most of the staff (70 percent) have whānau (children, nieces, nephews, and grandchildren) who attend the kura. One teacher has been on the staff since the inception of the kura, and four teachers are former students.

Te Aho Matua, the document that underpins all kura kaupapa Māori legally and, more importantly, philosophically is the “foundation document” (Mataira, 1997) of Te Kura Kaupapa Māori o Hoani Waititi Marae and is fundamental to understanding how this kura functions. Te Aho Matua sets out the philosophies and creates the context where “being Māori” is a “taken for granted” norm at the kura. Ahuatanga ako (Māori pedagogies) is a significant part of Te Aho Matua. It involves the interaction of Māori cultural concepts at work. Whanaungatanga is one framework within which Māori pedagogy operates that goes beyond the teacher–student or teacher–parent relationships to a whānau-based relationship centred on the marae.

Avondale Intermediate

Avondale Intermediate serves a multi-ethnic community and is located in Avondale, a western suburb of Auckland city. The school has grown over the past four years (much of growth has been from out-of-zone enrolments), representing increased community confidence, and it now caters for 536 pupils. A large number of students come to Avondale Intermediate from Rosebank Primary School and the majority of students go on to attend Avondale College. The school’s special features include a special needs cluster unit (schools in the cluster provide a component of their Resource Teachers: Learning and Behaviour (RTLB) resource to provide a full-time RTLB on site at Avondale Intermediate), and Oaklyn Special School Satellite Unit, administered from Avondale Intermediate. The aim is to base these students in a mainstream school setting and, where appropriate, to “mainstream” students.

Avondale Intermediate has undergone significant structural and philosophical changes since 2001 when Rota Carrington became the principal. There have also been significant changes in staffing through this time, including an increase in Māori teachers. Avondale Intermediate currently employs 27 staff and has a decile rating of 3.

Over the past five years, the school has developed a well-articulated philosophy and culture that seeks to be positively responsive to its diverse multi-ethnic demographic. This demographic includes a large Pasifika population (Samoan, 23 percent; Tongan, 7 percent; Niuean, 4 percent; and Cook Island Māori, 5 percent); a growing Māori population at 20 percent; together with Chinese (7 percent), Indian (14 percent), and African (3 percent). Pākehā students comprise 12 percent of the school population (Education Review Office, 2005).

This cultural diversity is regarded as a school strength and is actively included and valued in the school. Tikanga Māori is also valued in the school and guides day-to-day school protocols and practices. The school culture is also strongly student-centred and has a range of practices and programmes designed to encourage student participation and the development of a range of high level thinking skills. These school priorities are well supported through whānau-based composite classrooms, wherein Year 7 and Year 8 students are combined. The school is also organised into whānau, each one named after a native tree, for example, Rimu and Kowhai. Each whānau has an associated colour and other symbols of identity.

Lincoln Heights School

Lincoln Heights School is a full primary (Years 1–8), decile 4 school located in Massey, Waitakere city. It has a staff of 26 teachers, and a school roll of 605 students, of whom 53 percent are male, and 47 percent female. Lincoln Heights is an ethnically diverse school, with 31 percent of the school roll Pākehā; 27 percent Māori; 27 percent Pasifika (15 percent Samoan, 4 percent Tongan, 3 percent Cook Island Māori, 2 percent Niuean, and 2 percent Fijian); 5 percent Asian; and “others”, including Middle Eastern, make up 13 percent of the roll. The school has a high number of children with ORRS (Ongoing and Reviewable Resourcing Schemes) funding. It has a reputation in this part of Waitakere city for being a school that caters well for special needs. Most of ORRS’s children are mainstreamed.

Teaching and learning programmes at Lincoln Heights reflect what its most recent Education Review Office (ERO) report (released in February 2006) describes as a “strong values base and an educational vision”. This has enabled the school to provide “an educational environment that is stimulating, inclusive and highly learner-centred” and teaching programmes that “strongly emphasise assisting students to become self-directed learners. Positive interpersonal relationships with staff and other adults are the foundation for teaching programmes” (ERO, 2006, pp. 2–3). The ERO report made reference to Lincoln Heights’ “long history of developing innovative approaches to teaching and learning” (2006, p. 2) but neither acknowledges nor names the deeply embedded theories and ideas of William Glasser underlying the school’s education vision, its teaching programmes, and its approach to management. Glasser (1992) developed an approach to the management of student behaviour that involved socialisation to the notion of quality.

Table 1 provides a comparative demographic overview of the four different contexts involved in this project. The most recent ERO report available for each school was sought from the ERO website to source the data included in the table. It must be noted that the kura figures include all levels of learning from new entrants through to the secondary levels. Lincoln Heights is a full primary so the figures will also include learners from other levels besides Year 7 and 8. During the development of the project proposal, Lincoln Heights was a decile 3 school.

Table 1 Demographic characteristics of the four schools

2. Pasifika-specific data is gathered for only three Pasifika cultural groups (Samoan, Tongan, Cook Islands) at this school. Data for students who identify as any other Pasifika cultural groups (e.g., Niue etc) are put together, as total numbers of students are very low.

Research design and methodologies

A detailed discussion of the project, its design and methodologies (particularly in relation to the strategic values of the TLRI, and for future research and development) can be found in sections 2 and 4. This part of the report will describe the research design and discuss the issues of significance to developing the kinds of relationships and partnerships that were of significance to the implementation of the project. Also included is a discussion about the barriers to implementation that were encountered.

Project design and methodological framework

The project was designed to address the overall research question in three parts (described as “phases” in the original TLRI proposal as well as in project’s application to the University of Auckland’s Human Participants Ethics Committee). These were:

- definition of effective teaching practice across schools and cultural groups

- documenting and analysing characteristics of culturally responsive teaching practices

- production of policy, practice, and research reports.

The primary means for gathering data (interviews, focus groups, analysis of school documentation, school observations, and classroom observations) were also intended to help develop collaborative relationships between researchers, practitioners, and community members, and shape the research project itself.

The collaborative relationships were not the only significant influence that shaped the research, particularly in terms of the specific approaches taken in the four different schools and kura. A number of key terms can be used to link the overall research framework and describe its “essence”. The terms are: ethnographic, case study, narrative, participant observer, and privileged observer.

Wolcott provides a concise description of ethnographic research as it pertains to education (1988). A multi-dimensional approach is employed involving a variety of data gathering techniques such as interviews, analysis of documents, and participant observation. However, for Wolcott, the determining feature of ethnographic research is the focus on how ordinary people make sense of the experiences of their own lives. This is facilitated through participant observation which involves reducing the distance between the researcher (as observer) and those participating by allowing themselves to be observed. Of the different participant styles that Wolcott describes, the privileged observer appears to be most like the role that the senior researchers developed in the three schools and the kura. Privileged observers become such by virtue of the relationships they form. As a consequence of mutual trust and respect, participants do more that give the researcher permission to observe and to query. They actively engage, support, and reveal more and more. The research process is much more of a shared enterprise, and involves conscious power sharing.

Other characteristics of ethnographic research, as described by Cohen, Manion, and Morrison (2000), that can be identified in this project include:

- “knower and known are interactive, inseparable”

- “behaviour and thereby data are socially situated, context-related, context-dependent and context-rich. To understand a situation researchers need to understand the context because situations affect behaviour and perspectives and vice versa”

- “inquiry is influenced by the choice of the paradigm that guides the investigation” y “inquiry is influenced by the choice of the substantive theory utilised to guide the collection and analysis of data and in the interpretation of findings”

- “inquiry is influenced by the values that inhere in the context”. (2000, pp. 137, 138)

Cohen, Manion, and Morrison also describe case studies as an approach to research. They state:

Case studies provide a unique example of real people in real situations enabling readers to understand ideas more clearly than simply presenting them with abstract theories and principles. … Case studies can penetrate situations in ways that are not always susceptible to numerical analysis. (2000, p. 181)

They describe a number of characteristics of case studies. The following resonate with the researchers in terms of this project. For example, a case study:

- “is concerned with a rich and vivid description of events relevant to the case” y “provides a chronological narrative of events relevant to the case” y “blends a description of events with the analysis of them”

- “focuses on individual actors or groups of actors and seeks to understand their perceptions of events”

- “[has a researcher who] is integrally involved in the case”

- “[attempts] to portray the richness of the case in writing up the report”. (2000, p. 182)

Finally, narratives involve an “emphasis on using the interplay between interviewer and interviewee to actively construct” (Cohen et al., 2000, p. 163). Narratives draw heavily on the words of the persons interviewed, and are often “backed up” by observations, interviews with others, and the study of relevant documentation.

The literature review contained within section 3, provides in-depth discussion on the methodological theories that informed the research in different contexts or settings.

Overview of research activities

A number of different research activities were used across the schools and kura. These were: interviews and focus groups; classroom observations; observation of selected school and community activities; the collection and analysis of documents; and the development of school purakau or portraits. The individual school case study, purakau, or portrait provides more detailed information about the research activities carried out within the school or kura. Section 4 maps out the four rich sources of new knowledge and information.

Relationships and partnerships: Issues of significance

There were a number of issues of significance to the establishment of critically important relationships and partnerships. The primary set of relationships was that between researchers and each school.

The process of establishing and developing school-based partnerships

Schools are not always willing to be involved in research projects. This may be due to having had poor experiences with research projects (Coxon et al., 2001, pp. 13–14) in the past or simply because schools and their teachers have demanding, time consuming responsibilities and very high professional expectations of themselves. For some principals, there may be an understandable reluctance to make a commitment to be involved in a research project, particularly a project that is presented as “pathology” (Lawrence-Lightfoot, 1983; Lawrence-Lightfoot & Davis, 1997); that is, a study of what is wrong—of identifying the causal factors of problems of teachers, their work, and the settings within which they work. The steps which the research team followed in the process of identifying schools, and making the initial approaches in order to be welcomed by the school management to come and collaborate with their staff, are listed below.

The research team enlisted the support of specific senior academic staff for an initial informal approach to selected schools. For example, the principal of one school had recently been a postgraduate student of one of the professors. Two members of the research team happened to be parents in the school community of the kura. The project was able to use pre-existing relationships for the initial approaches to three of the four schools. The relative importance of these networks cannot be underestimated. When formal approaches were made, it was with confidence that there would be a warm, interested, and prompt reception.

The fourth school was “cold” in that the research team had did not have informal networks or contacts with senior staff or management. The initial approach was made via a formal email about the project and a request for the opportunity to discuss it further with the principal. More time and effort was required in this school to establish credibility, given that the project team did not have the almost “instant” goodwill and even credibility that comes from a mutual, well-regarded acquaintance’s sponsorship.

A formal meeting was scheduled at each school with its principal or delegated senior management person (for example, deputy principal). Research team members who attended were: one of the three principal investigators, the senior researcher that would work with the school, and a research assistant. In addition to discussing the overall research project, and what would be involved with the partnership, the principal assigned a senior management team member to carry out a coordinating role between the project and school based activities (referred to as “the school research co-ordinator” or “the co-ordinator”).

A meeting with staff was organised for a later date. In two of the schools, the opportunity for the research team to speak to the staff as a whole about the project, and to field questions, was slotted into a scheduled after-school staff meeting. They were given a handout that summarised the research questions. These particular meetings were generally non-eventful—researchers left with the impression that staff in those meetings were tired and vaguely interested but preoccupied, with more immediate concerns. In one of the other schools, research team members were invited to a special late morning meeting with senior Year 7 and Year 8 staff, Pasifika board of trustee members, and the whole senior management team. All staff in attendance were focused and interested in the presentation. The discussion about the research project was robust.

After the formal meeting with the staff, a special meeting was scheduled with the teachers in the group or syndicate that school management had determined would work with the researchers. These were Year 8 teachers—due to the composite approach in one school, these were the teachers of Year 7 and 8 students. The groups were made up of four to five teachers, with the exception of the kura which had a much smaller number of students in their Year 8 programme, and hence had a smaller number of teachers to work with. The date and time for this meeting was suggested by the school co-ordinator. The research team prepared and delivered written invitations to attend afternoon tea with the researchers.

These meetings were well received. Again, tired teachers seemed to come into the staffroom out of a sense of duty and, at that point, without much in the way of a personal commitment or interest in the project. Having nice refreshments did appear to have an impact on the tenor of the meeting. The senior researchers ensured that they demonstrated awareness, sensitivity, and appreciation for the teachers’ time. As former classroom teachers themselves, this was not difficult. Their empathy was genuine.

The research team sought permission from the boards of trustees. Formal letters were presented (including a participant information sheet and consent letter). In some schools, a senior researcher attended one of the monthly meetings of the board of trustees to describe the project and answer any questions. In other schools, the opportunity for the senior researcher to interact with board of trustee members occurred later in the project. In some instances, interesting connections were made between researchers and one or more board members—for example, in one school, the senior researcher met an acquaintance from her former classroom teaching days, who was a parent member of the board of trustees.

Regular meetings with the syndicate or group of teachers were either scheduled or at least discussed. The stated purpose of such meetings was to discuss literature, organise classroom observations and interviews with teachers and, more importantly, create a collaborative research unit.

Nurturing confidence, establishing credibility and collegial acceptance in schools

Even after principals warmly and enthusiastically accepted the opportunity to be involved and delegated a senior management person to work directly with the project team, senior researchers were very careful about personalising their interactions with teachers. They did not want to assume that teacher participation was fine because the enthusiastic principal and deputy principal said it was so and wanted the teachers to be involved. welcomed

It was incredibly difficult to develop the kind of practitioner–researcher relationships where teachers were actively involved with the research process. It was hoped that the type of practitioner–researcher collaborations that would develop would have teachers engaged in reading and discussing literature, in addition to being observed teaching, being interviewed, and participating in discussions. A number of strategies were developed in order to address this, including:

- Developing a model for the project’s evolving structure and relationships between the various roles (see Appendix A).

- Making the literature informing the project accessible to busy teachers by means of writing “Pulse Points”. These were summaries of literature, each no more than four pages long. Altogether, six were written with the view that, in regular meetings with staff, these would be points of discussion. However, when it became very difficult to schedule and hold such meetings, the “Pulse Points” were passed to teachers via their pigeon holes in two of the schools. The informal feedback from teachers was that these were interesting—however, the full potential of these summaries remains unexplored.

- Scheduling meetings with group or syndicate staff that aligned with either their syndicate’s after-school meeting schedule, or the days after school that they did not have fixed school commitments.

- Ensuring there were refreshments (food and drink) when there were meetings. Again, senior researchers were always mindful that teachers are busy people and their involvement in this research project was in many ways an act of goodwill on their part.

- Giving personalised, on-the-spot responses, from senior researchers, to teacher and school needs. For example, in one school, the school co-ordinator had a minor car accident prior to a meeting with the senior researcher. His twin sons (pre-schoolers) who were passengers in the car were unsettled and fearful for some days after the incident. It was obvious that this was very much on the school co-ordinator’s mind. The senior researcher purchased a story book about a group of noisy, active dinosaurs and gave it to the co-ordinator to read to his sons in order to distract his boys. It was a gesture of sympathy and concern from one person to another.

- Providing teachers with a token gesture of appreciation, or “koha”, for their contribution. This was altered during the course of the project. The original plan (as discussed with principals) was that teacher relief would be given to the school for the time involved by their teachers.

However, rather than needing relief for teachers so they could be interviewed and their classes observed and so on, senior researchers decided that for commitment to a series of specific activities, teachers could select one of three options: a teacher release day that would be designated for their use (not the general staff pool), or $200 in book vouchers, or $200 towards a professional development course of their choice. The presentation of the koha was framed very carefully—it was not presented as an entitlement but rather as a gesture of genuine appreciation from the research project. Teachers in two of the schools selected book vouchers. In the kura, the preference was for a lump sum contribution to the school for an upcoming, whole-school professional development experience. A similar decision was made in the fourth setting, for the group of teachers involved.

This may not be a common practice for school-based research. However, due to the nature of the underlying qualitative research framework (which facilitated the development of in-depth knowledge of each school) and the inter-personal nature of the research–practitioner relationships (developed on mutual understanding and respect as professionals), the researchers were driven by the need to reciprocate in ways that would directly benefit and empower their school-based colleagues.

This method of koha was very well received. For example, in one school, upon receiving the book vouchers (their choice), the teachers purchased additional resources for use with their students (such as new books for their classroom book corners).

- providing participants (such as teachers and management) with transcriptions of interviews to review and give feedback. They were presented with the opportunity to amend or withdraw their comments. Because transcriptions were so literal, the general response was “Did I really say ‘um’ that many times?!” There was only one instance where a participant requested that the interview occur again, as she was not comfortable with what she had said in the transcript. The researchers believe that, in addition to being a feature of ethical practice, such an action (that is, giving transcripts to interviewees to check) was a means of validating and respecting participants, and ensuring the balance of power was not overly “tipped” towards the researchers.

Barriers encountered: Overwhelm and overcome

A series of highly significant barriers were experienced over the lifetime of the project, several being unanticipated and beyond the control of the research team, particularly the senior researchers. Some events had an immediate, obvious impact but they also had a sustained effect that was more subtle, less obvious, even insidious and overwhelming.

Major losses and changes in project (research) leadership

Half-way through the first year of the project (June 2004), one of the principal investigators left to attend conferences in the United States, and was expected back four weeks later. Her return was delayed by weeks, then months, due to the after-effects of a traumatic incident she was involved in. In the first week of December 2004, the project team received a direct communication from her that she would not be returning to New Zealand and had resigned from her position at the university. It was this principal investigator who had been the main driver of the research design and co-authored the proposal. She introduced portraiture as a methodology to the research team, but opportunities to share her knowledge with the senior researchers before she left were limited. Of the three principal investigators, she was the one that was going to be more “hands on” in the field, working alongside senior researchers and mentoring.

Finding a replacement was very difficult. Senior academic staff who had been involved in the development of the original proposal were, by and large, already committed elsewhere in terms of research, and understandably, the research design (already fixed in terms of being accepted as a project proposal, and “sealed” by the ethics committee process) was not something a new person could take on easily with any sense of ownership. The dilemma of a replacement was addressed by the recommendation of one of the remaining principal investigators that the project coordinator be “elevated” to the role of principal investigator, given that for six months she had been responsible for milestone reports and getting the school-specific relationships started in the schools (with the exception of the kura).

A second principal investigator left the project when his research fellowship with the university finished in the fourth quarter of 2005 and he returned to Fiji. The third principal investigator resigned from her position at the university early in 2006, before the final reporting for the project was completed.

Restructuring and institutional change within the university

When the project proposal was first submitted to the Teaching and Learning Research Initiative in 2003, the proposed research team consisted of academic staff and postgraduate students of the School of Education, located in the Faculty of Arts, University of Auckland. In September 2004, the university amalgamated with the Auckland College of Education. A new Faculty of Education was established, comprising the former Auckland College of Education and the former School of Education. Much of 2005 was “business as usual” for the two former institutions, although the pace of preparation for change began to accelerate in the second semester of that year. Researchers for this project found themselves in an organisation that embarked on a programme of profound, accelerated change which impacted on the professional circumstances of the senior researchers. This was to have a significant impact in terms of work loads and provided a severe challenge to what was possible for senior researchers to do in the field in 2005 and into 2006 with regards to final reporting.

Some of the professional changes in circumstances in terms of roles and responsibilities for individuals included: in 2005, one senior researcher took leave from employment for the whole year (but continued her commitment to this project), and submitted her resignation at the end of 2005. Another senior researcher, also the project co-ordinator and principal investigator, was promoted to a new and demanding management position within the new faculty, starting in October 2005. The absence of a fully involved, experienced senior academic staff member to lead, mentor, and provide an overarching monitoring role on the project became even more pronounced.

Schools: Predictable and unpredictable

Despite senior researchers having classroom experience, the senior researcher assigned to each school soon learned the extent to which their teacher-colleagues were busy people—hugely busy! Schools are undoubtedly systems of procedures, practices, and policies involving people. Teachers are people who get sick, they change jobs (as does management), they have to address sudden events involving students (for example, squabbles on the playground), and they do far more than teach students in classrooms. Sickness, sorrow, and even celebrations can impact unexpectedly on appointments for interviews, classroom observations, and so on. Other more traumatic events can affect the whole school community in profound ways, as well as affecting the “privileged observers” who have established a rapport with individual teachers. Take, for example, the sudden death of a participating teacher in one of the schools. The senior researcher involved with the school attended her funeral. The researcher was unable to touch the transcripts of the deceased teacher’s interviews and field notes for months afterwards. Perhaps it is the nature of the research framework developed and used within each school that made the unexpected events or barriers to the research even more problematic, and even overwhelming.

Māori and Pasifika research assistants and project administrators: A puddle not a pool

It was the intention of the project to develop capacity and capability of emerging Māori and Pasifika researchers (discussed in more detail in section 6). However, the project found that there was a significant shortage of appropriate, qualified researchers and research assistants when original researchers and research assistants left the project due to changes in their personal and professional circumstances. The departure of one of the original senior researchers in the middle of 2004 was not addressed until 2005, when a doctoral student of Fijian heritage was employed as a senior researcher up until her return to Fiji in August. A Māori post-graduate student was employed when a senior researcher took leave from her University position for a year, in 2005 as well. Each of the research assistants left, and finding suitable replacements with access to their own transport was so difficult that the effort to search for such support was given up.

Culturally grounded ethical issues and responses

Research ethics and principles are discussed in the literature review in section 3. Areas of debate regarding ethical issues, particularly in terms of different cultural perspectives (including institutional or organisational perspectives) included:

- acknowledging teachers and their expertise and skills via koha that truly reflected the givers’ respect for teachers professional expertise and contributions

- locating a Pasifika research agenda in relation to a Māori research agenda. At times, there were tensions which needed careful and sensitive negotiating.

3. Literature review

To understand is hard. Once one understands, action is easy.

Sun Yat Sen, 1866–1925

This project has been informed by research-based literature in the following broad areas:

- culturally based research paradigms, models and methodologies

- literature, based on the New Zealand and United States contexts, on diversity in education and culturally responsive pedagogies (or, more appropriately for the New Zealand context, “responsiveness to diversity framework”).

The literature in this section has been organised into a number of subsections:

- kaupapa Māori (principles and practices that have resulted in methodological developments known broadly as kaupapa Māori research)

- Pasifika research ethics and principles (which are informing new and emerging approaches to research that foster a greater sense of ownership by the Pasifika researchers and participants involved)

- portraiture as a qualitative methodology

- diversity and multicultural education in the context of the United States y “responsiveness to diversity framework” in the context of New Zealand.

Recalling, reviewing, and reconstructing cultural ways of research

Kaupapa Māori

Kaupapa Māori principles and practices have been instrumental in the methodological development of this research. Graham Hingangaroa Smith (1997) stresses the need for kaupapa Māori principles to be in active relationship with practice. Linda Tuhiwai Smith (2000) also emphasises the need for kaupapa Māori methodologies to provide frameworks for understanding what is happening in the domain of Māori education, whilst simultaneously interrogating other research methodologies and their contribution to understanding what is happening in education in this country. She advocates the need to construct research maps that extend our research horizons:

What maps should qualitative researchers study before venturing onto such [tricky] terrain? This is not a trick question but rather one that suggests that we do have some maps. We can begin with all the maps of qualitative research we currently have, then draw some new maps that enrich and extend the boundaries of our understandings beyond the margins. We need to draw on all our maps of understanding. Even those tired and retired maps of qualitative research may hold important clues such as the origin stories or genealogical beginnings of certain trends and sticking points in qualitative research. (2005, p. 102)

Here Linda Smith is suggesting that we should not be limited to current and popular research practices (whether it be qualitative or quantitative), but must recall, review, and reconstruct our cultural ways of research so that we can better unravel and begin to change the multiplicity of things that negatively affect our lives. Kaupapa Māori contributes to that role in this research, in that it provides a framework from which to engage and select other research maps to use within the research process. “Portraiture” is another methodological approach which is discussed in the following section.

In order to locate the research findings outlined in this report, a key notion that must first be engaged is that of kaupapa Māori. Kaupapa Māori is a term that has its origins in a history that reaches back thousands of years. It is not a new term. The term “kaupapa” is outlined in some depth by Mereana Taki (1996, p. 17) who writes:

Kaupapa is derived from key words and their conceptual bases. Kau is often used to describe the process of ‘coming into view or appearing for the first time, to disclose’. Taken further kau may be translated as ‘representing an inarticulate sound, breast of a female, bite, gnaw, reach, arrive, reach its limit, be firm, be fixed, strike home, place of arrival’ (H. W. Williams c. 1844–1985, p. 464). Papa is used to mean ‘ground, foundation base’. Together kaupapa encapsulates these concepts, and a basic foundation of it is ‘ground rules, customs, the right of way of doing things’.

Sheilagh Walker (1996) has also discussed kaupapa Māori. For Walker, “kaupapa” is the explanation that gives meaning to the “life of Māori”. It is the base on which the super-structures of Te Ao may be viewed. Māori are tangata, born into a geophysical cultural milieu. Kaupapa Māori becomes kaupapa tangata. What evolves is this—He aha te mea nui o te Ao? He tangata, he tangata, he tangata. In essence, this whakatauki explains kaupapa Māori.

Tuakana Nepe (1991, p. 15) discusses kaupapa Māori in relation to the development of kura kaupapa Māori. She states that kaupapa Māori is the “conceptualisation of Māori knowledge” that has been developed through oral tradition. This is the process by which the Māori mind “receives, internalises, differentiates, and formulates ideas and knowledge exclusively through Te Reo Māori.” Nepe situates Māori knowledge specifically within te reo Māori. Kaupapa Māori knowledge is not to be confused with Pākehā knowledge or general knowledge that has been translated into Māori. Kaupapa Māori knowledge has its origins in a metaphysical base that is distinctly Māori. As Nepe states, this influences the way Māori people think, understand, interact, and interpret the world.

For Nepe, Māori knowledge is esoteric and tuturu Māori. It validates the Māori world view and is owned and controlled by Māori through te reo Māori. Te reo Māori is the only language that can access, conceptualise, and internalise in spiritual terms this body of knowledge. From this, it can be taken that Māori language and kaupapa Māori knowledge are inextricably bound. One is the means to the other. Ka penei te kōrero a Nepe:

Kei te tino marama tatou katoa ma te reo Māori anake ka taea te whawha atu i te hohonutanga me tuturutanga o nga mātauranga o nga matua, tipuna. Kotahi anake te huarahi. Korerotia, korerotia, korerotia te reo ki a tatou tamariki i nga wa katoa. Whangaitia, whangaitia, whangaitia o ratou wairua Māori. Kahore e taea e nga ture Pakeha. Kahore e taea e te reo Pakeha. Ma te reo Māori anake ka tutuki nga moemoea katoa mo a tatou tamariki. (1991, p. 15)

Nepe’s writing argues for the significance of kaupapa Māori as an educational intervention system to address the Māori educational crisis and to ensure the survival of kaupapa Māori knowledge and te reo Māori.

The writing of Graham Smith is instrumental here. Smith’s academic writing spans ten years. His 1997 text, The Development of Kaupapa Māori Theory and Praxis, is pivotal. The centrality of te reo Māori me ōna tïkanga is also highlighted by Smith (1997). He identifies and discusses three key themes within the kaupapa Māori paradigm—the validity and legitimacy of Māori; the survival and revival of Māori language and culture; and Māori autonomy over their own cultural wellbeing and their own lives.

This locates te reo Māori me ōna tïkanga as critical elements in any discussion of kaupapa Māori principles and practices and is in line with the assertions made by Nepe that Māori language must be viewed as essential in the reproduction of kaupapa Māori. Expanding the discussion of what constitutes kaupapa Māori principles and practices in a changing world has been the focus of many Māori people involved in research and development of Māori programmes in the various sectors. It is noted, however, that in regard to national developments the area of Māori education has been crucial. The developments of te kōhanga reo and kura kaupapa Māori have placed Māori in a position where what is kaupapa Māori , and its importance and significance, is responsive to the identification of Māori pedagogical practices that have been made. This has brought to the fore debates over various kupu, tïkanga, and kawa and how they are best located as kaupapa Māori practice.

Kaupapa Māori knowledge permeates each of the components of kaupapa Māori education including te kōhanga reo, kura kaupapa Māori, kura kaupapa Māori teaching training, the development of kura kaupapa Māori resources, whare wānanga and whare kura. Graham Smith (1997) outlines kaupapa Māori as a term used by Māori to describe the practice and philosophy of living a “Māori” culturally informed life. In essence, this is a Māori world view which incorporates thinking and understanding. Māori writers and academics from several different disciplines have articulated the importance, centrality, validity, and the imperative to guarantee the survival of te reo Māori.

Following on from Nepe, Taina Pohatu (1996) advances the argument that cultural underpinnings of whenua and whakapapa are imperative to ensure cultural transmission and acquisition (socialisation). His work, entitled I Tipu ai Tātau i nga Turi o Tātau Matua Tipuna, is a statement of cultural re-centering and emancipation.

Kaupapa Māori has emerged as a discourse and a reality, as a theory and a praxis directly from Māori lived realities and experiences. One of those realities is that for more than a century and a half, the New Zealand education system has failed the majority of Māori children who have passed through it. Kaupapa Māori as an educational intervention system was initiated by Māori to address the Māori educational crisis and to ensure the survival of kaupapa Māori knowledge and te reo Māori.

The term “theory” has been deliberately co-opted by Graham Smith (1997) and linked to “kaupapa Māori” in order to develop a counter-hegemonic practice and to understand the cultural constraints exemplified within critical questions such as “what counts as theory?” Smith challenges the narrow, eurocentric interpretation of “theory” as it has been applied within New Zealand education.

Sheilagh Walker (1996) also unpacks the history of Western philosophy, choosing to locate kaupapa Māori within a distinctly theoretical terrain that is Māori initiated, defined and controlled. Kaupapa Māori theory has had the dual effect of providing both the theoretical “space” to support the academic writing of Māori scholars as well as being the subject of critical interrogation, analysis and application.

Russell Bishop and Ted Glynn (1999, p. 61) refer to kaupapa Māori as the “flourishing of a proactive Māori political discourse”. For these writers, kaupapa Māori is a movement and a consciousness. Since the 1980s, with the advent of te kōhanga reo, kaupapa Māori has become an influential, coherent philosophy and practice for Māori conscientisation, resistance and transformative praxis, advancing Māori cultural and educational outcomes within education. As Graham Smith (1997) outlines, kaupapa Māori theory is still in the formative stages despite the appearance of the term within discussion forums in the 1980s when the Department of Education was attempting to introduce “taha Māori” into the curriculum.

As Graham Smith (1997) has articulated, kaupapa Māori initiatives develop intervention and transformation at the level of both “institution” and “mode”. The mode can be understood in terms of the pedagogy, the curriculum, and evaluation. The institutional level is the infrastructural component and involves economics, power, ideology, and constructed notions of democracy. Kaupapa Māori challenges the political context of unequal power relations and associated structural impediments. Smith makes the point, however, that transforming the mode and the institution is not sufficient. It is the political context of unequal power relations that must be challenged and changed. In short:

Kaupapa Māori strategies question the right of Pākehā to dominate and exclude Māori preferred interests in education, and asserts the validity of Māori knowledge, language, custom and practice, and its right to continue to flourish in the land of its origin, as the tangata whenua (indigenous) culture. (1997, p. 273)

Kaupapa Māori thus challenges, questions and critiques Pākehā hegemony. It does not reject or exclude Pākehā culture. It is not a “one or the other” choice. As Graham Smith (1997) states, the theoretical boundaries of kaupapa Māori have been tested, interrogated, and reflected upon by the Māori community and the Auckland academic group, and disseminated locally and internally. To put it succinctly, at the core of kaupapa Māori is the catch-cry “to be Māori is the norm”.

Key intervention elements in kaupapa Māori

The Māori Education Commission (1999), in its third report, discussed several intervention and success factors that underlie kura kaupapa Māori. The factors identified are:

- tino rangatiratanga

- emancipatory model

- visionary approach

- Māori knowledge validation

- akonga Māori: Māori pedagogy

- school kawa

- whānau control

- kia piki ake i ngā raruraru o te kainga.[3]

Identifying these elements provides indicators as to key elements underpinning kaupapa Māori developments. These elements also lean heavily on the work of Graham Smith (1997), who outlines also six of the seven areas identified by the Māori Education Commission. That work is foundational in the development of analyses regarding kaupapa Māori in education and therefore deserves in-depth discussion.

Graham Smith (1997) highlights six intervention elements that are an integral part of kaupapa Māori and which are evident in kaupapa Māori sites. These are:

- tino rangatiratanga (the “self-determination” principle)

- taonga tuku iho (the “cultural aspirations” principle)

- ako Māori (the “culturally preferred pedagogy” principle)

- kia piki ake i nga raruraru o te kainga (the “socioeconomic” mediation principle)

- whānau (the extended family structure principle)

- kaupapa (the “collective philosophy” principle).

These principles are also articulated by other writers and therefore an overview of each is provided.

Tino rangatiratanga: The “self-determination” principle

The principle of tino rangatiratanga goes straight to the heart of kaupapa Māori. It has been discussed in terms of sovereignty, autonomy and mana motuhake, self-determination and independence. Situated within the Treaty of Waitangi, it is the antithesis of kawanatanga. The principle of tino rangatiratanga has guided kaupapa Māori initiatives, reinforcing the goal of seeking more meaningful control over one’s own life and cultural well-being. A crucial question remains—can tino rangatiratanga be achieved within existing Pākehā-dominated institutional structures? Te kōhanga reo and kura kaupapa Māori, for example, were started outside of conventional schooling explicitly in order for Māori to take control of their destiny.

The theory and praxis of tino rangatiratanga will be discussed in relation to other mainstream services for Māori including kaupapa Māori justice, kaupapa Māori health, kaupapa Māori housing, kaupapa Māori employment and other social services. In the area of health, Mason Durie (1998) relates that in the 1980s, tino rangatiratanga became part of the new Māori health movement where health initiatives were claimed by Māori as their own.

Taonga tuku iho: The “cultural aspirations” principle

A kaupapa Māori framework asserts a position that to be Māori is both valid and legitimate and in such a framework to being Māori is taken for granted. Te reo Māori, mātauranga Māori, tikanga Māori and ahuatanga Māori are actively legitimated and validated.[4] This principle acknowledges the strong emotional and spiritual factor in kaupapa Māori, which is introduced to support the commitment of Māori to intervene in the educational crisis.

Ako Māori: The “culturally preferred pedagogy” principle

This principle promotes teaching and learning practices that are unique to tikanga Māori. There is an acknowledgment of “borrowed” pedagogies. Māori are able to choose their own preferred pedagogies. Rangimarie Rose Pere (1982) writes in some depth on key elements in Māori pedagogy. In her publication Ako she provides expansive discussion regarding tikanga Māori concepts and their application to Māori pedagogies.

Kia Piki Ake i Nga Raruraru o Te Kainga: The “socioeconomic” mediation principle

This addresses the issue of Māori socioeconomic disadvantage and the negative pressures this brings to bear on whānau and their children in the education environment. This principle acknowledges that despite these difficulties, kaupapa Māori mediation practices and values are able to intervene successfully for the wellbeing of the whānau. The collective responsibility of the Māori community and whānau comes to the foreground.

Whānau: The “extended family structure” principle

The principle of whānau, like tino rangatiratanga, sits at the heart of kaupapa Māori. The whānau and the practice of whanaungatanga is an integral part of Māori identity and culture. The cultural values, customs, and practices which organise around the whānau and “collective responsibility” are a necessary part of Māori survival and educational achievement.

Within the writings outlined in this literature review, there are many examples where the principle of whānau and whanaungatanga come to the foreground as a necessary ingredient for Māori health, Māori justice and Māori prosperity. One of the most potent examples of whānau can be seen in the dynamic organisation known as Te Whānau o Waipareira. This organisation came into being in 1981, becoming a charitable trust in 1984. The origins of the whānau, however, date back to the 1940s and 1950s when Māori urbanisation occurred.

Kaupapa: The “collective philosophy” principle

Kaupapa Māori initiatives in Māori education are held together by a collective commitment and a vision. Te Aho Matua is a formal charter which has collectively been articulated by Māori working in kaupapa Māori initiatives. This vision connects Māori aspirations to political, social, economic, and cultural well-being.

Leonie Pihama (1993) has also written extensively on kaupapa Māori theory. For Pihama, inherent in kaupapa Māori theory is an intrinsic critique of power structures in Aotearoa that historically have constructed Māori people in binary opposition to Pākehā, reinforcing the discourse of Māori as the “other”. Kaupapa Māori theory aligns itself with Critical Theory in that it seeks to expose power relations that perpetuate the continued oppression of Māori people.

Pasifika research principles and values

Introduction

The Pasifika researchers involved with this project were guided by specific values and principles. Their approach to various research activities and the structure of the overall project was influenced by their own culturally-based articulations of principles such as reciprocity, respect, and contribution. This part of the section identifies and articulates the Pasifika researchers’ approach to the research.

The metaphor

“Fale” is the Samoan word for house. Traditional Samoan fale construction, particularly of ceremonial fale, is an architectural and cultural art form developed over many hundreds of years, and is unique to this part of Polynesia. The fale tele (round house) is one form of ceremonial meeting house. Its basic structure shapes the metaphor for the set of ethical principles and values that informed this project’s Pasifika researchers’ practices.

A fale tele has between one to three centre posts, on the top of which is fixed the vaulted roof. When the centre posts or poutu are set and upright, they become part of the skeletal structure that firstly, sets the height of the fale, and secondly, enables the builders to construct the frame of the fale both above and below the poutu. Raising the poutu is like the laying of a cornerstone of a significant European-style building, for example a church or cathedral. This is such a key part of the fale construction that a feast is held to mark the event.

Following this, the ridge post is placed on top of the poutu and the process of constructing the complicated rafters and arches of the vaulted roof begins. Another “remarkable aspect of the fale tele design” (UNESCO, 1992, p. 43) is that when the wall posts are put into place, few of them are actually necessary for supporting the roof. According to a UNESCO resource:

the ultimate proof of the master builder’s skill would be to let the fale remain in the form of the umbrella it emulates at the outset. Wall posts are not structural necessities. (1992, p. 43)

A Pasifika paradigm

The poutu provide the fale tele with structural strength. An explicit set of principles to inform research practice provides the integral strength for Pasifika researchers—it is the source of their integrity, even mana as Pasifika researchers. This in turn shapes their sense of place, and even ownership, to a certain extent, over the research processes. The principles justify the ways that relationships were developed and nurtured within the project.

The poutu set the height of the fale or project. The height of the centre of the fale determines the expanse of the building—both vertically and horizontally. Three principles, articulated from a Pasifika perspective, set the aspirations—visions, even—for the outcomes of the project. These are visions about accelerating achievement for Pasifika learners, and promoting the social and economic development of their communities, their peoples. These are lofty visions and ideals. In a mainstream tertiary context, the research capacity of researchers is increasingly being determined by constructs such as Performance Based Research Funding (PBRF); however Pasifika researchers’ visions do not include PBRF measures of research outputs, personal academic career advancement, or potential publications. While these are important, they cannot set the heights of the fale or project. They are far too low. The concept of poutu provides a Pasifika-based conceptualisation of what constitutes appropriate measures and relationships within Pasifika research processes and has informed the Pasifika research approach to this TLRI project.

The expanse of the project, its potential area of impact and change, is determined by how the principles have been articulated and embedded in the project’s overall design and structure, and how closely Pasifika researchers have used these principles as a reference point during project implementation. The primary principles and values that have influenced Pasifika researchers are reciprocity, respect, and contribution.

Sources of the poutu approach to research

The Ministry of Education contracted Coxon, Anae, Mara, Wendt Samu and Finau to develop its Pasifika Education Research Guidelines, which was released in 2002. Other sectors have since developed and released guidelines with similar intents and purposes; for example, the Health Research Council (2004) and the Tertiary Education Commission (2003, for the Performance based Research Fund).

According to the Ministry of Education guidelines, Pasifika research needs to begin by:

identifying Pacific values and the way in which Pacific societies create meaning, and structure and construct reality. (Coxon, Anae, Mara, Samu, & Finau, 2002a, p. 7)

Identifying values and articulating them from a Pasifika perspective is of crucial importance because the creation of relevant meanings for Pasifika participants, and of Pasifika researchers themselves, will engender a strong sense of ownership and personal commitment. This will lead to an improved alignment between the personal–professional values of the individuals involved, and the values that are embedded in the project design, structure and implementation.

The Health Research Council’s research guidelines express similar views on the role of Pasifika research and its starting point. According to the Health Research Council, the primary role of Pasifika research is to:

generate knowledge and understanding both about, and for, Pacific peoples. (Health Research Council of New Zealand, 2004. p. 11)

However, both the Ministry of Education guidelines and the Health Research Council guidelines include statements about the way Pasifika research should be designed and structured as projects.

For example, the Ministry of Education guidelines, in the section about “research teams”, not only describes the possible types of research teams that can come under the banner of “Pasifika research” but also states that Pasifika management and control must be evident in any research project, at all levels.

The Health Research Council guidelines are more explicit and comprehensive:

Pacific research requires the active involvement of Pacific peoples (as researchers, advisors and stakeholders) and demonstrates that Pacific people are more than just the subjects of research. Pacific research will build the capacity and capability of Pacific peoples in research, and contribute to the Pacific knowledge base. (Health Research Council, 2004, p. 11)

The Health Research Council guidelines illustrate the continuum of possible structures for research projects, which have varying degrees of Pasifika participation, including decision making and management roles and positions. The structures range from “Pacific relevance” to “partnership” through to “governance” (2004, p. 6). The Health Research Council guidelines appear to advocate that the ideal structure for projects is one where there is Pasifika governance— that is, the team is Pasifika-led, applies Pasifika paradigms and models, focuses on Pasifika populations, has Pasifika outcomes and exhibits Pasifika ownership.

The Ministry of Education and Health Research Council guidelines identify and discuss “common Pacific values” (Anae et al., 2001, p.14) or “ethical principles of Pacific Health research” (Health Research Council of New Zealand, 2004, p.12). For the Ministry of Education guidelines, the common Pasifika values are: respect, reciprocity, communalism, collective responsibility, gerontocracy, humility, love, service, and spirituality. For the Health Research Council, the ethical principles are: relationships, respect, cultural competency, meaningful engagement, reciprocity, utility, rights, balance, protection, capacity building, and participation. The Tertiary Education Commission’s Performance Based Research Fund produced a set of draft guidelines for assessing evidence portfolios that include Pasifika research. Included in the guidelines was an elaboration of its definition of Pasifika research. According to Tertiary Education Commission, Pasifika research must demonstrate “some or all of the following characteristics and should show a clear relationship with Pacific values, knowledge bases and a Pacific group or community” (2003, p. 2). The characteristics are: paradigm, participation, contribution, and capacity/capability.

It can be argued that what Tertiary Education Commission describes as “characteristics” are also principles, and have a degree of congruence with the some of the “Pacific values” described by the Ministry of Education guidelines, and some of the ethical principles identified and described by the Health Research Council guidelines.

Pasifika researchers and the poutu for this project

The primary principles and values for the Pasifika researchers in this project were reciprocity, respect and contribution. This is how they articulated the principles and values in terms of the research activities and processes they were involved with. As a consequence, the research became Pasifika research.

In terms of reciprocity, Pasifika research involves:

- the perspective that involvement in the research project was a way to serve professional and cultural communities and groups

- the recognition and validation of the relationships between the researcher and the “researched”. Such recognition requires taking, even creating, opportunities to “give” at the site of the interactions; for example, giving mealofa (in this case, personal money in an envelope at the funeral of one of the teacher participants; responding to the request from school management to present a seminar about the research as a part of their Education Review Office review)

- accepting and honouring the responsibility and duty that comes with development of relationships of mutual respect and support.

In terms of respect, Pasifika research:

- demonstrates that Pasifika people (learners, teachers, parents) and others are more than just subjects of research; for example, changing the recognition of teacher involvement from paid teacher relief days to the school to three options for teachers to select (teacher relief for the specific teacher; koha of book vouchers; contribution to a professional development experience of their choice)

- involves the active participation of Pasifika peoples (as researchers, assistants, and project managers)

- is sensitive and responsive to contextual shifts and changes; for example, the unexpected changes to scheduled events due to ill-health of a participant, or to school events

- will acknowledge tangata whenua as tuakana in collaborative research partnerships such as this project, and respond accordingly, informed by Pasifika notions of humility

- actively seeks to accommodate data gathering activities and requirements to the participants’ schedules and programmes.

In terms of contribution, Pasifika research:

- has an impact on Pasifika communities, including small communities of Pasifika teachers within a staff

- contributes to and enhances the Pasifika knowledge base in all areas: for example, research methodology, ethics, and principles; teaching and learning and diversity

- contributes to a greater understanding of Pasifika cultures, experiences, and multiple world views including the socio-cultural experiences within school communities y is relevant and responsive to the needs of Pasifika peoples

- contributes to Pasifika knowledge, spirituality, development, and advancement y is responsive to changing Pasifika contexts.

What is clear is that the principles or the poutu that have influenced the approach to research for Pasifika researchers has enabled connections of new knowledge, understandings, perspectives, and relationships. This has heightened the level of Pasifika ownership within this project.

Portraiture: A methodological approach

As noted in the project outline, this research project involved the development of a “snapshot”, or portrait, of each participating school. In order to develop such a picture, information was collected on school policy, procedures, practice, and processes, and researchers visited as many school events and activities as possible, such as staff meetings, festivals, and sports activities. This section of the literature review engages with the notion of “portraiture”. While some may see the case studies in this research as providing a “snapshot” of a schooling context, it is our view that the term “portrait” is a more accurate description than “snapshot” or “picture”, because it signifies a greater time scale and more elaborate effort—portraits take time and effort to produce—and the process of developing an emerging image is a source of learning in itself in addition to the final piece of art.

The development of a school “portrait” reflects the portraiture method developed by American educational researcher, Sara Lawrence-Lightfoot, of Harvard University. According to Dixson, Chapman, and Hill:

ortraiture is best described as a blending of qualitative methodologies—life history, naturalist inquiry, and most prominently, that of ethnographic methods. (2005, p. 17)

Lawrence-Lightfoot uses the methodology of portraiture to present six portraits of high schools in the United States in her book The Good High School: Portraits of Character and Culture (1983). Through detailed school descriptions, the author seeks to capture each school’s individual culture: its essential features, generic character, the values that define its curricular goals and institutional structure, its individual styles and ritual. In creating these portraits, Lawrence-Lightfoot attempts to trace and understand the connections between the individual and the institution—how its inhabitants create the school’s culture and how they, in turn, are shaped by it, and how individual personality and style influence the collective character of the school. Through this type of research and representation, Lawrence-Lightfoot presents a new understanding of schools as “cultural windows”.

Lawrence-Lightfoot’s approach to understanding specific school contexts is both a methodology and a philosophy in itself. According to Lawrence-Lightfoot:

The portraits in this book are not drawn, they are written. They do not present images of a posed person but descriptions of high schools inhabited by hundreds, thousands of people…. On each canvas in broad strokes, I sketch the backdrop. The shapes and figures are more carefully and distinctively drawn, and attention is paid to design and composition.… Individual faces and voices are rendered in order to tell a broader story about the institutional culture. The details are selected to depict and display general phenomena about people and place. I tell the stories, paint the portraits—‘from the inside out’. (1983, pp. 6-7)

Lawrence-Lightfoot draws heavily on the medium of art to explain and describe the philosophy underlying her portraiture method. For example, in terms of real portraits and the work of artists, she stated:

The portraits captured essence: the spirit, tempo, and movement … portraits tell you about parts of yourself that you are unaware of…or to which you haven’t attended. (1983, p. 5)

[P]ortraits make subjects feel ‘seen’ in a way that they have never felt seen before, fully attended to , wrapped up in an empathetic gaze. (1983, p. 5)

Artists recognize the humanity and vulnerability of the subject…the artist’s gaze searches for the essence, relentless as it tries to move past the surface images…in finding the underside, in piercing the cover, in discovering the unseen, the artist offers a critical and generous perspective—one that is both tough and giving. (1983, p. 6)

Art is used as a metaphor for the observation, interviewing, and writing process that the researchers will go through in order to “draw” what they see and what they learn in schools. The process was one through which Lawrence-Lightfoot sought to present some of the features of each of the schools, a process which she describes as follows: