1. Literature review

This literature review is intended to provide a background to the project undertaken and described in this report. In essence the project seeks to apply a research-based model of literacy instruction developed in New Zealand to investigate the efficacy of the model in raising student achievement. It is our intention to do so using collaborative teacher and researcher partnerships in order to investigate and interrogate the ways in which the model can respond to the needs of specific students, teachers, and schools. This being the case, the literature on adolescent literacy is reviewed, effective instructional approaches are evaluated, and the outcomes of “successful” interventions are described. Secondly, we investigate the literature on effective professional development, and in particular the efficacy of research partnerships for promoting teacher learning and practice.

Adolescent literacy

Over the past 25 years, the field of adolescent literacy has changed dramatically (Vacca & Vacca, 2007) as the “research base that supports our knowledge of oral and written language development, linguistics, psychology, and other areas related to literacy has expanded” (Sturtevant & Linek, 2004, p. 4).

The contemporary field of adolescent literacy is underpinned by broadened constructs of learner, text, and context, and by considerations of the social and cultural demands placed on secondary learners (Lester, 2000; Moje, Dillon & O’Brien, 2000). The field takes into account adolescents’ literacy practices beyond the secondary classroom, adolescents’ expanded notion of text, and the relationship between literacy and the development of identity (Moje, Young, Readance & Moore, 2000; Moore, Bean, Birdyshaw & Rycik, 1999; Patel Stevens, 2002). Contemporary conceptions of adolescent literacy are perhaps best summed up by the International Reading Association’s (IRA) position statement on adolescent literacy:

Adolescents entering the adult world in the 21st century will read and write more than at any other time in human history. They will need advanced levels of literacy to perform their jobs, run their households, act as citizens, and conduct their personal lives. They will need literacy to cope with the flood of information they will find everywhere they turn. They will need literacy to feed their imaginations so they can create the world of the future. In a complex and sometimes even dangerous world, their ability to read will be crucial. Continual instruction in literacy beyond the early grades is needed (Moore et al., 1999, p. 99).

Literacy learning

Instruction beyond the early grades is necessary not only to equip adolescents for the adult world, but to enable them to successfully navigate the world of secondary school. Given that the nature of the texts that adolescents are required to interact with has changed significantly, and that the literacy demands that secondary schools place on adolescents have increased in complexity (and may well be greater than those of the primary school (Christie, 1998; Ivey & Broaddus, 2000), the nature of the actual literacy skills required for success across the curriculum has changed.

In addition to mastering content knowledge in a wide variety of disciplines, teenagers need to develop “content literacy” (Sturtevant & Linek, 2004; Vacca & Vacca, 2007). Content literacy is a relatively new term which refers to the ability to learn effectively through reading, writing, viewing and discussion, in every content area. According to Vacca and Vacca (2007, p. 10) a variety of classroom-related factors influence content literacy in a given discipline, including:

The learner’s prior knowledge of, attitude toward, and interest in the subject;

The learner’s purpose for engaging in reading, writing, and discussion;

The language and conceptual difficulty of the text material;

The assumptions that the text writers make about their audience of readers;

The text structures that writers use to organise ideas and information; and

The teacher’s beliefs about and attitude toward the use of texts in learning situations.

In order to experience success across the curriculum, students need to be aware of the extent to which the distinctive discourse forms of different disciplines will affect their ability to make sense of the new material they encounter (Dean & Grierson, 2005; Stowell, 2000; Unsworth, 2001). Specifically, secondary school students are required to use the skills and strategies developed during early reading instruction, and their prior knowledge, to interact with text to interpret and construct meaning before, during, and after reading. In particular, and as distinct from primary schools, secondary schools require that students: read large amounts of text; learn specialised and technical vocabulary; master knowledge of the various text structures that are used to organise subject material; and make meaning from the texts that are predominantly used by teachers as the basis of instruction (Bryant, Ugel, Thompson, & Hamff, 1999). To engage in meaning making at a sophisticated level, students must be able to think beyond the literal recall of content-area facts and they must develop the skills to interpret, apply, and interact with a wide variety of texts at a variety of levels (Ruddell, 1996).

However, there are large numbers of students who struggle to develop content literacy (Author, 2002, cited in Hall, 2005; McDonald & Thornley, 2004). National and international achievement statistics indicate low levels of literacy achievement for secondary school students along with disparities in achievement (Crooks & Flockton, 2000; Flockton & Crooks, 2001, 2002; Greenleaf, Schoenbach, Cziko, & Mueller, 2001; McDonald & Thornley, 2005; Ministry of Education, 2003), and support the “notion of a literacy crisis” in secondary schools (de Leon, 2002, p. 2).

The difficulties that most adolescents who struggle with reading face are not caused by an inability to decode words but by the fact that they have limited vocabularies and/or lack broad background knowledge to apply to their reading. Students find that their literacy endeavours are hampered because they are unable to “get beyond the words”, to get access to bigger and more complex ideas (Darwin & Fleischman, 2005). As Delfino (1998, pp. 17–18) explains:

Most students for whom English is the primary language can read, if by reading we mean the decoding of words. But that is the problem. They read word-by-word, and these isolated words do not add up to any larger meaning for them. They are not engaged in the text when they read; they do not use the strategies that good readers use automatically. They don’t realise that reading their science book will require any different skill, action, or response from what they experience when they read a novel. They don’t see pictures as they read; they don’t make predictions as to what will happen next or what someone will say. They respond literally and don’t think metaphorically. Because they don’t make predictions, they don’t see irony or the juxtaposition of thought or actions that engage and delight successful readers. These students do not turn to books when they need to escape or when they want to meet new friends. They do not turn to books when they want to visit new places or experience exciting adventures. They do not turn to books when they yearn to visit the future or learn from the past. For these students, reading brings only frustration and failure.

Effective literacy instruction

In order to support students to meet the literacy challenges of secondary school, and to develop content literacy, it is vital that teachers plan and implement instruction that facilitates both content knowledge and literacy learning. Teachers’ content literacy knowledge is an important factor in student achievement, and teachers who provide content literacy instruction can impact strongly on their students’ current and future success (Sturtevant & Linek, 2004; Vacca & Vacca, 2007). However, many teachers lack knowledge of the literacy challenges inherent in different curriculum areas and are ill-equipped to teach students to meet those challenges (Darwin & Fleischman, 2005; Hall, 2005; Thornley & McDonald, 2002). Historically, direct literacy instruction in secondary classrooms has been limited to the development of study skills and vocabulary knowledge (Hall, 2005). When students have encountered difficulties with texts, teachers have commonly responded by ameliorating texts and providing students with key ideas and concepts through alternate means such as inclass lectures, producing notes, and tutorial books (McDonald, Thornley & Fitzpatrick, 2005; Schoenbach, Greenleaf, Cziko & Hurwitz, 1999). According to Darwin and Fleischman (2005, p. 85), “this practice may actually circumvent students’ need to improve their literacy skills, thus avoiding the problem rather than addressing it”.

In order to effectively address students’ needs in order that they can improve their literacy skills, teaching must account for students’ prior experiences (in relation to content, text, and text reading and writing) and must provide opportunities for students that will help them to explore, discover, and think critically within specific disciplines (Lester, 2000; McDonald & Thornley, 2004; Moore & Murphy, 1987). To these ends, teachers need to use their content expertise along with their knowledge of learning processes and instructional strategies, to negotiate and to make explicit the specific ways in which students are required to interact with texts for their content areas (Hall, 2005; Lester, 2000). As Vacca and Vacca (2007, p. 7) explain:

Teaching content well means helping students discover and understand the structure of a discipline. The student who discovers and understands a discipline’s structure will be able to contend with its many detailed aspects. From an instructional perspective, teachers must help students see the ‘big picture’ and develop the important concepts and powerful ideas that are part of each subject …. To help students become literate in a content area does not mean to teach them how to read, write or talk as might be the case in a reading or English classroom. Instead reading, writing, talking, and viewing are tools that students learn to use with texts in content areas.

Norrie and Lenski (1998) argue that the role of the teacher is critical in guiding students to think in various ways about texts as they are read. They suggest that for teachers to achieve this they must encourage students by responding to them in generative ways that prompt their students to understand, to clarify, to validate, and to raise questions. Viewing the teaching and learning process in this way means that building students’ skills as readers and as manipulators of information becomes an act of negotiation overlaid by the teacher’s knowledge of literacy processes as they relate to their content area (Moje, Dillon, et al., 2000).

Teachers hold a wide range of beliefs about literacy instruction in the content areas. These beliefs include: that content-area teachers either cannot or should not teach literacy; that teaching literacy in the content areas is important; that content-area teachers would like to teach literacy but do not know how; and that teaching literacy is the responsibility of others, for example English teachers and/or reading specialists (Hall, 2000).

The belief that literacy instruction is someone else’s role has been particularly widespread amongst content area teachers (Behrman, 2004; Denti & Guerin, 2004). For example, secondary teachers who participated in a study reviewed by Hall (see Bintz, 1997, cited in Hall, 2005) acknowledged that their students had reading difficulties but they did not believe that they should work to improve this. According to Denti and Guerin (2004, p. 115), “the statement ‘I’ve never taught reading and I don’t know how’ expresses an accurate self-evaluation of many high school teachers”. In response to opinions of this nature, Vacca and Vacca (2007, p. 7) argue that:

The pursuit of content literacy does not diminish the teacher’s role as a subject matter specialist … who’s in a better, more strategic position to show students how to learn with texts in a particular content area and grade level than the teacher who guides what students are expected to learn and how they are to learn it?

Just as it is important that teachers believe that they are teachers of literacy, it is equally crucial that they believe that their students are capable of success. As Hill and Hawk’s (2000) study of effective teachers in Achievement in Multicultural High Schools (AIMHI) schools suggests, it is a combination of beliefs held by teachers about their work and about their students that contributes to the development of effective teachers. It has been shown that teachers’ attitudes towards their students affects the quality of educational opportunity available to those students (Alton-Lee, 2003; Cook, Tankersley, Cook & Landrum, 2000), and the importance of the holding of high levels of expectation for students has been well documented Ministry of Education, 2004). According to Carpenter, McMurchy-Pilkington and Sutherland (2000), the set of beliefs driving effective teaching practices must include the recognition that students can take responsibility for their own learning when teachers support them to do so, a personal and public passion for teaching, and a strong sense of connectedness with students and their worlds (see also Bishop, Berryman, Tiakiwai & Richardson, 2003).

Professional development in adolescent literacy

Training or transmission models of professional development have historically been the primary vehicle for the delivery of teacher professional development. Traditional models have been criticised because of their focus on learning content knowledge, and their underlying assumption that teachers are knowledge recipients (Timperley, Phillips, & Wiseman, 2003; Timperley & Wiseman, 2003) and because they fail to consider the contextual circumstances of teachers, students, and schools or to take account of teachers’ knowledge and previous learning experiences (Ball & Cohen, 1999; Borko, 2004; Guskey, 2000; King & Newmann, 2000; Putnam & Borko, 1997). A particularly damning criticism along these lines is levelled at traditional forms of professional development by Fullan (1991, p. 315, cited in Hawley & Valli, 1999, p. 134) who states that “nothing has promised so much and has been so frustratingly wasteful as the thousands of workshops and conferences that led to no significant change in practice when teachers returned to their classrooms”.

Certainly, there is little record of professional development programmes leading to changes in practice that result in changes in student achievement (Earl & Katz, 2002; Little & Houston, 2003). It is becoming increasingly clear that teachers’ professional development and learning is fundamental to raising student achievement (Poulson & Avramadis, 2003; Taylor, Pearson, Peterson, & Rodriguez, 2005, Timperley & Phillips, 2003), and consequently improving student outcomes has become a primary rationale and purpose for professional development (Hawley & Valli, 1999).

A number of elements that are characteristic of the type of professional learning which supports teachers towards the type of literacy instruction that can improve their students’ outcomes have been identified in the school change, professional development, and adolescent literacy research literature. Specifically, effective professional development in adolescent literacy acknowledges the complexity of adolescent literacy and the necessity for literacy instruction, and it is characterised by a shared vision for literacy reform amongst all stakeholders (Bean & Harper, 2004). Such professional development is ideally located in collegial communities of practice (Birman, Desmone, Porter, & Garet, 2000; Fernandez, 2002) and supported by strong instructional and collegial leadership (Poulson & Avramidis, 2003; Taylor et al., 2005).

Furthermore, for professional development in adolescent literacy to be effective, it needs to be firmly based in both relevant research and in the realities of school life and teachers’ daily practice (Elmore & Burney, 1997; Fernandez, 2002; Hawley & Valli, 1999). It also needs to be informed by student learning data, including students’ perceptions (Kershner, 1999) and information about teachers’ practices and beliefs, in order to encourage teachers to reflect on and analyse their students’ learning alongside their own theories, beliefs, and values and the ways in which they might use various content-literacy methods and strategies within the secondary school context (Bean & Harper, 2004; Kinnucan-Welsch, Rosemary & Grogan, 2006; O’Brien, Stewart, & Moje, 1995).

Teacher–researcher research partnerships as professional development

Several writers (for example, Cole & Knowles, 1993; Robinson, 2003; Saunders, 2004) have pointed out the commonalities between research and teaching, noting that the practice of each requires many of the same dispositions, skills, and understandings; that is, “attitudes of openness, intellectual curiosity, and a willingness to step outside a frame of reference to see things in new ways” (Robinson, 2003, p. 28). In Saunders’ view:

Researching and teaching have this in common, at the very least. They are about knowledge-creation and imaginative meaning making, in publicly accountable ways, in a complex and unpredictable world. The focus today must therefore be on illuminating how teachers can be enabled to exercise research-informed professional judgement in the service of a creative practice (2004, p. 164).

Although these commonalities would seem to suggest that the road to creating and sustaining teacher–researcher research partnerships is a smooth one, there are inherent tensions in the relationships between teachers and researchers and the cultures in which they function (Cousins & Simon, 1996; Graham, 1998). This literature review explores, and takes account of, these tensions as it considers the central question of how teachers and researchers can conduct and perform research, not only in the service of a creative practice, but also in partnership with each other and, most importantly, in the service of improving student outcomes from, and experiences of, schooling.

This review draws on literature from the fields of action research, critical inquiry, and professional development. It also pays attention to the Teaching and Learning Research Initiative’s (TLRI) position and perspectives on teacher–researcher research partnerships.

Much of the literature around teacher–researcher research partnerships has been generated by the school professional development movement and, as such, primarily deals with school and university partnerships (Lacina, 2006), which are generally located within professional learning communities or communities of practice (Graham, 1998). Frankham and Howes (2006) view the communities of practice model as a useful one for analysing the learning and commitments of colleagues working together. They do, however, caution against “using the concept [of a community of practice] normatively, with features of communities of practice identified and then used as indicators of the appropriateness of relationships and processes in a particular setting” (p. 629).

In reality, there are a range of models for communities of practice, and partnerships play out in various ways and take various forms. Graetz, Mastropieri, Scruggs, and Agosta (2004), for example, outline two options. The first option involves researchers asking teachers to implement specific interventions in their classrooms and, therefore, teachers assuming the role of the intervener rather than the designer of research. Alternatively, researchers ask teachers to identify the challenges in their classrooms, and teachers and researchers then work together to identify possible solutions in the research literature and to create systematic research designs to evaluate the proposed solution (see Greenwood, Tapia, Abbott, & Walton, 2003, for a discussion of a similar model to this second option).

In the New Zealand context, Oliver (2005) examined teachers’ experiences in five TLRI projects. The projects in Oliver’s study fell into two areas of inquiry. The first emphasised the teacher and teaching. Researchers provided teachers with strategies to reflect on their practice and guided and mentored them to make changes to practice and methodology in order to enhance their teaching in general and/or better align their practice with curriculum developments. Change in teacher practice was implicit in the second area of inquiry, which focused on students, student learning, or curriculum. The teachers’ roles were to test students, analyse the results, and develop theories, findings, and recommendations that would enhance student learning.

Collaboration is central to research partnerships

The idea of partnership which is prioritised by TLRI is that of partnership as a reciprocal process which builds teachers’ and researchers’ research capability and deepens their understandings of teacher practice. This notion of partnership extends to partnerships between teachers and is underpinned by a premise of collaborative knowledge building and sharing of tasks (Oliver, 2005).

Similarly, within the international literature, collaboration is held as central and critical to teacher–researcher research partnerships whatever specific forms and foci the partnerships may have (Corden, 2002; Goodnough, 2004; Graetz et al., 2004). Collaborative research enterprises are viewed as ones where people work together to create and produce knowledge that can benefit individuals, the group, or both. A distinction is sharply drawn between partnerships that are collaborative and those which are “merely cooperative” (Goodnough, 2004, p. 323). In contrast to collaboration, co-operation is seen to focus on individual learning, encouraging people to help each other out, and often amounting to nothing more than teachers’ co-operation with researchers’ research agenda (Cole & Knowles, 1993; Goodnough, 2004).

In drawing the distinction between collaboration and co-operation, a number of writers emphasise the “essentiality of negotiation” (Cole & Knowles, 1993, p. 488) to truly collaborative research. Negotiation is seen as an ongoing process which includes negotiating roles, responsibilities, status, commitment, and available energies (Cole & Knowles, 1993; Goodnough, 2004). Such a process is evident in Graetz et al.’s (2004) description of a partnership between school and university personnel. The partnership was centred around a classroom problem where, because participants considered that the collaborative relationship was critical, “nothing [italics added] was undertaken without discussion among the participants” (Graetz et al., 2004, p. 277).

A cautionary note is sounded in this regard by Cole and Knowles, who assert that:

Collaboration for collaboration’s sake seems counter-productive. True collaboration is more likely to result when the aim is not for equal involvement in all aspects of the research; but, rather, for negotiated and mutually agreed upon involvement where strengths and available time commitments to proceed are honoured. (1993, emphases in original)

As the preceding would indicate, collaboration, as it is conceptualised and enacted in the context of teacher–researcher research partnerships, is complex, and at times, problematic. It is particularly problematic that the culture of schools and universities differ dramatically in focus, tempo, and rewards (Graham, 1998). Berger et al. (2005) assert that teacher research is contrary to the culture of schools, noting that the collaborative, collective orientation of research groups is at odds with school cultures that typically support teaching as an isolated activity and “assign peculiar meanings to equity, collaboration and excellence” (p. 103).

Clearly, then, the notion of collaboration resists simple definitions. According to Frankham and Howes (2006, p. 627), it is the very “unknowability” of concepts such as collaboration, relationship, and partnership that define them, and it is therefore difficult to provide exact criteria for the types of relationships and processes that constitute collaborative research partnerships.

This difficulty is compounded by contrasting views on aspects of collegiality. For example, Lacina (2006) holds that respect and collegiality should be developed prior to a collaborative project, whereas the results of Frankham and Howes’ study of the role of university researchers, in a project aimed at developing inclusive practices in schools through collaborative action research, suggest the opposite. As Frankham and Howes (2006, p. 617) note:

One of the issues highlighted is that it is in the process of setting up an action research project that many disturbances are evident and, perhaps, inevitable. We argue that it is in working with these disturbances that one might begin to establish the basis of a collaborative relationship, rather than implying that collaboration may result in such things.

The complexities involved in providing a template for collaborative research relationships notwithstanding, a number of writers (for example, Cole & Knowles, 1993; Goodnough, 2004; Graetz et al., 2004; Lacina, 2006; Oliver, 2005) agree that certain conditions need to be present for research partnerships to be truly collaborative. Collaborative research relationships are underpinned by:

The understanding that each partner in the inquiry process contributes particular and important expertise, and that the relationship between the classroom teacher and the university researcher, for example, is multi-faceted and not powerfully hierarchical. (Cole & Knowles, 1993, p. 478)

Based on this understanding, collaborative research partnerships accord equal status to all partners; are typically founded on participants’ common values and beliefs; and are underpinned by fundamental assumptions about the importance and mutuality of goals, interpretation, and reporting, and about the potency of multiple perspectives (Ball & Cohen, 1999; Borko, 2004; Putnam & Borko, 1997).

Teachers as partners in research relationships

In addition to the conditions discussed above as being necessary for collegiality, teacher ownership is seen as central to collaborative research partnerships. Hargreaves (1994, in Lacina, 2006) found that teachers resent prescribed collegiality, especially when they see no direct relationship between the collaborative initiative and their own classrooms. As both Lacina (2006) and Oliver (2005) emphasise, teachers must have a voice in choosing with whom they want to collaborate and when to collaborate. It is also important that teachers have a voice in the nature of the inquiry. Goodnough (2004, p. 324) notes that:

in order to foster collaborative inquiry the participants need to experience empowerment throughout the process. One way to do this … [is] to structure an experience in which teachers would determine the research questions and how to design action research projects … to explore an issue or problem that would be most meaningful for their professional practice.

However, the process of teachers initiating, designing, and conducting research is not necessarily straightforward. Simply developing a teacher culture which values and expects evidence-based discussion of the quality of teaching and learning is problematic and, at a fundamental level, teachers’ conception of research and of themselves as researchers can impact on their ability to engage in research activities. For example, teacher-researchers in one of the schools in Berger et al.’s 2005 study initially

struggled simply with the idea of qualitative research thinking of it as foreign and distant … they report that that it took them months and months to even feel comfortable beginning to pose questions and that those early questions were awkward and unanswerable—either enormous and unwieldy or too small and uninteresting. (emphasis in original).

Like the teachers in th school from Berger et al.’s study, teacher-researchers in Graham’s (1998) study had had limited experience as classroom researchers and also struggled with the idea of “research”. To these teachers, “research was a devil word” (p. 255), representing situations where researchers who were isolated in universities knowing “little and caring less about classroom complexities” passed down theories for practitioners to implement.

In a similar vein to teachers experiencing researchers as arrogant people who are ready to criticise and recommend change without appreciating the complexity of the contexts they are investigating, researchers can experience teachers as defensive, suspicious, and unresponsive, with a limited understanding of the intellectual and practical challenges involved in doing worthwhile research (Lacina, 2006; Oliver, 2005; Stipek, Ryan & Alarcon, 2001). Furthermore, researchers may be reluctant to enter into full collaboration with teachers because they are unwilling to relinquish their status and power as experts at “doing research” (Cochran-Smith & Lytle, 1993; Sweeney, 2003; Zeichner, 1995). As noted by Cousins and Simon:

Differences in power and stature between researchers (traditional producers of knowledge) and users (traditional receivers of knowledge) and the formers’ desire to maintain its privileged position may lead to inadvertent or unconscious acts that are consistent with its motives or even to mischievous behaviours designed to protect the status quo. (1996, p. 202)

The attitudes outlined above, linked as they are to those tensions between university and school which are rooted in issues of power, status, and authority (Frankham & Howes, 2006; Graham, 1998; Lacina, 2006), are indicative of the “oppositional discourse” (Robinson, 2003, p. 27) of practitioners versus researchers. According to Graham (1998), the attitudes associated with this oppositional discourse are enormous obstacles to overcome and require a shift in assumptions and expectations about who creates, and what counts for, knowledge and in roles and responsibilities.

The roles and responsibilities of teacher and researcher within partnerships are clearly not as uncomplicated or unproblematic as conventional constructions of these roles and responsibilities (as equal, straightforward, and unproblematic, with the teacher bringing the perspectives of practice and the researcher bringing the theoretical perspectives (Frankham & Howes, 2006)) would suggest. As previously indicated, teacher inexperience and lack of familiarity with research processes can complicate the processes of collegiality and teacher ownership that are inherent to collaborative research partnerships. Furthermore, without ongoing support, the results of teacher research can sometimes be less than optimal. As Berger et al. note:

Teachers—like all new researchers—have trouble formulating researchable questions, connecting their data collection methods to questions they are asking, and drawing conclusions from the often messy data of schools and schooling. We found that when teachers were given confidence in their natural researching abilities without the benefit of additional skills or ongoing assistance, the research seemed quite simplistic. (2005, p. 102)

Teacher inexperience in “doing research” was discussed by Oliver in her (2005) report of teachers’ experiences in five TLRI projects. In four of these projects the teachers became involved after academic researchers had formulated the research project designs and research questions. Although they had not had input into the overall aims, objectives, design, or methodology of their project, these teachers indicated that the research was well planned, they were happy with it, and that they could have had some input if they had wanted to. They all felt that the research design and the framing of research questions were broad enough for them to write specific research questions and flexible enough to be contextualised within their practice and/or national educational initiatives.

Some of those teachers responded “yes and no” when asked to have input into the research and qualified this by noting that they were so unsure when embarking on the projects that they were in no position to make suggestions. As they engaged in conducting the research and became familiar with the research design and objectives they were able to make changes based on their experiences of the project. Oliver posits that “it is possible that if those teachers had been involved in setting the research objectives, designing the research or writing the questions, they may have been less unsure early on of the purposes of the project” (2005, p. 19).

In contrast, the four teachers in the other project in Oliver’s study (all of whom had completed or were completing their Master of Education degrees) initiated their individual research projects and then worked together with researchers and other teachers involved in the project to construct the overall TLRI project. These four teachers designed their own research questions and designed and undertook their individual projects under the supervision of the researchers. Oliver thought that it was possible that these teachers were more likely to initiate research projects because they were in management positions (with less classroom contact time) and had established relationships with university researchers and academics to call on.

Lack of familiarity with research processes proved no barrier to teachers’ equal participation in research partnerships in one school in Berger et al.’s (2005) study. In this school, teacher research was mandated by the principal; the principal and deputy had established a multitude of ways to discuss research across groups; every faculty member, including the principal, had an active research question; staff development time was used to teach (mainly quantitative) research methods; and faculty meetings were centred on data. In these ways teacher research was a “fully integrated part of every teacher’s experience” (p. 99) and they owned the research. Berger et al. found that:

Teachers did not seem to struggle with the idea of research even though many of them had had no experience with teacher research before. They found the quantitative methods of measuring, documenting and analysing … challenging, but none of them spoke of … [any] kind of lengthy struggle to develop researchable questions … These teachers clearly felt empowered about their teaching, felt more expert and certain about their craft and they connected their research directly to curricular changes and/or student achievement. (2005, pp. 99–100)

Berger et al. did note that some elements which they regarded as crucial to teacher research (specifically a focus on individual students and the central questions of self-examination and teacher roles and development) were not present in the teachers’ conversations. This point notwithstanding, Berger et al. found that the research informed and promoted a high level of collaboration and that the teacher–researcher research partnerships which were enacted within the school were generally collaborative and successful ones.

Factors which Berger et al. identified as being key to this success included the research-driven culture of the school; a strategic choice of teachers; the perceived positive impact of the research; the researcher’s conduct; a long-term commitment to research projects; encouragement to present research results to other staff and wider audiences; and, most especially, the principal’s mandate and support of teacher research.

Berger et al. were surprised by how critical the work of the principal was (see also Lacina, 2006; Oliver, 2005). This was highlighted by the contrasting experiences in two other schools in their study. In one of these schools, following a state mandate, the principal had mandated research for all teachers. Some of the teachers were strongly resistant to this mandate and, consequently, the principal withdrew it with the result that more than half the teachers chose not to do research. The principal of the other of these two schools actively sought and gained funding for teacher research, and teachers were well paid for the research work they undertook (e.g. writing during vacations). When the principal left the school and the funding ran out (and was not reapplied for by the next principal, who did not value teacher research) research within the school ended.

Berger et al.’s “greater learning” (2005, p. 100) in this regard was that teacher research will not become a school-wide effort if it is not mandated, but that the principal who mandates the research must be extraordinarily careful about how they go about implementing and supporting such initiatives (Berger et al.., 2005; Lacina, 2006). Berger et al. described the paradox that was revealed in this instance as “teacher research must be mandated/ teacher research can’t be mandated”:

[Teacher research] must be championed by a strong principal; it can’t be owned by the principal .… It seemed an interesting paradox that the principal’s key role would require strong leadership to mandate the research, set up the structures and then give ownership of the research to the teachers (2005, p. 101, emphasis in the original).

Researchers as partners in research relationships

Another paradox that Berger et al. discussed centred on the role of the academic researcher. They framed this paradox as “there must be an outside actor; the outside actor’s role is questionable” (p. 101). Outside actors were those who were generally based in universities, professional leagues, unions, or funding agencies. Whilst they were credited with bringing some important ideas, skills, and support to the teacher-researchers, none of the teachers or administrators that Berger et al. interviewed could point to exactly how the outside agent had been of use or what would have happened in the absence of such an agent.

In contrast, whilst still viewing the role as problematic, other writers have specified responsibilities and roles of researchers. As previously mentioned, the initiation and planning of research within teacher–researcher research partnerships typically falls into the purview of academic researchers (Corden, 2002; Goodnough, 2004), as do associated responsibilities such as ongoing project management, budgeting, monitoring and resourcing. Arguably, this situation could be the result of researcher experience, expertise, and available resources, or more simply it could arise from the “often casual presumption that academic researchers can decide to enact ‘partnership’ or ‘collaborative’ work” (Frankham & Howes, 2006, p. 620). Whatever the cause, and as previously noted, researcher control of the initiation and design of research can be argued to serve to maintain the status quo in respect to researcher status and power (Cousins & Simon, 1996).

Another way that the role of academic researcher is seen as overplaying the researcher’s importance is through its emphasis on techniques of facilitation. Kemmis and McTaggart (2005) see that the role of academic researcher is primarily and specifically concerned with facilitation and they regard this as being somewhat paradoxical and problematic, in that it can “implicitly differentiate … the work of theoreticians and practitioners, academics and workers” (Kemmis & Mc Taggart, 2005, p. 569). Influenced by Habermas (1996), Kemmis and McTaggart have come to understand research partnerships as open and inclusive networks where the facilitator can be a “contributing co-participant, albeit with particular knowledge or expertise that can be helpful to the group” (p. 595) and where all members of the partnership can take a facilitator role. This understanding is echoed by teachers in Oliver’s (2005) study who saw that guidance and mentoring from the researchers helped the development of strong partnerships where members were equal but took different roles at different times.

Some writers (for example, Graham, 1998; Greenwood et al., 2003; Saunders, 2004) argue that a central part of the researcher’s role is that of modelling and providing guidance on researcher positioning and research practices and of supporting school-based research with scholarly expertise and methodological protocols. On the other hand, Frankham and Howes’s (2006) experience suggests that expertise and protocols were the “least important elements of what university researchers brought to the table” (pp. 619–620). Frankham and Howes argue that it was by working in and through relationships that they, as researchers, began to play a part in developments in the school. They promote an ethnographic-type engagement by researchers in settings so that, over time, teachers change from seeing the researcher as “wanting” something from the school to viewing them as nonthreatening co-conspirators and, consequently, researchers attain insider status at schools.

Clearly then, the adoption of a nonevaluative stance (Cole & Knowles, 1993; Stipek, Ryan, & Alarcon, 2001) is central to the positioning of academic researchers within collaborative research partnerships. The current study for example, adopted the vision of role of researcher as conceptualised by Groundwater-Smith and Dadds (2004, p. 242, cited in Oliver, 2005, p. 5) as “work[ing] with teachers rather than on teachers”.

Researchers work with teachers in various ways through collaborative research partnerships. In addition to utilising the previously mentioned processes of facilitation, modelling, and mentoring, research groups support teachers to learn about research and research methods through reading and discussing professional readings; examining research projects completed by other teachers; evaluating and analysing data to make links between data and theory; and designing data collection tools (Corden, 2002; Goodnough, 2004; Graham, 1998).

Research frameworks and methodologies

Action research frameworks are “perhaps the best illustration[s] of how teachers are participating in and initiating alternative models of inquiry that involve them in the interpretation and representation of their own experiences” (Cole & Knowles, 1993, p. 477). Certainly, action research has been hugely influential in the area of teacher research and teacher–researcher research partnerships, and a great deal of the research and practice in the field has been generated in the context of action research (Corden, 2002; Frankham & Howes, 2006; Goodnough, 2004; Kemmis & McTaggart, 2005; Oliver, 2005).

Teacher action research is broadly located within constructivist and/or interpretive frameworks variously reflecting hermeneutics, phenomenology, and interactionist perspectives (Cole & Knowles, 1993; Oliver, 2005). Although it generally involves systematic inquiry into practice through cycles of planning, acting, observing, and reflecting, a number of writers agree that there is no specific blueprint for the process of action research or, as Frankham and Howes (2006, p. 628) put it, action research has to be “reinvented over and over again”.

In contrast to conventional research, action research involves inductive inquiry, which yields fuzzy, rather than firm, generalisations from which tentative hypotheses can potentially be formulated to stimulate further action research (Corden, 2002; Goodnough, 2004). Participatory action research (Kemmis & McTaggart, 2005), in particular, is distinguished from conventional research in several ways, most notably that it involves shared ownership of research projects; community-based analysis of social problems; and an orientation toward community action. Participatory action research does not regard either theory or practice as pre-eminent in the relationship between them. It aims to articulate and develop theory and practice in relation to the other by critically reasoning about both of them and their consequences and, in doing so, to transform theory and practice. Participant-researchers “are embarked on a process of transforming themselves as researchers, transforming their research practices and transforming the practice settings of their research” (Kemmis & McTaggart, 2005, p. 575).

Whether they employ action research and/or other methods such as case study (Smith, 2004), collaborative teacher–researcher research partnerships involve a mutual process of practitioner and researcher theory testing using data (Graetz et al., 2004; Robinson & Lai, 2006). Working with data is a primary/central activity of research partnerships (Berger et al., 2005) and the literature from the school professional development movement emphasises cultures of inquiry as sites for evidence-based research (Frey, 2002; Snow-Gerono, 2005).

Like most aspects of teacher–researcher research partnerships, working with data within cultures of inquiry is complex. Merely ensuring that teachers are provided with enough high-quality opportunities to learn the skills required to collect, interpret, and use evidence about the link between their teaching and their students’ learning is difficult (Robinson, 2003). Furthermore, there are inherent tensions in developing a culture of inquiry—for example the tension between being critical of colleagues in order to engage in deep professional learning and the simultaneous need for trust and respect—which the research on professional learning communities does not resolve (Robinson & Lai, 2006).

Tensions aside, teacher–researcher research partnerships generally employ multiple methods of data collection to enhance data analysis, interpretation, and corroboration and to build an evidence base. Data is collected from a range of sources including: participant and nonparticipant observation of student and teacher practice and meetings (Frankham & Howes, 2006; Goodnough, 2004; Greenwood et al., 2003); documents such as lesson plans, notes, letters and accounts between head teacher and researcher, and journals (Frankham & Howes, 2006; Goodnough, 2004); semistructured and informal interviews (Goodnough, 2004); teacher, parent, and student questionnaires (Corden, 2002; Frankham & Howes, 2006; Smith, 2004); student achievement data (Greenwood et al., 2003; Stipek et al., 2001); accounts and interventions by researcherparticipants (Frankham & Howes, 2006); consultations (Gratez et al., 2004); and student work samples (Corden, 2002).

Data analysis, within teacher–researcher research partnerships, uses a variety of methods such as dialectical analysis and grounded theory and can employ analysis software programs such as SPSS and NUDIST (Bernard, 2002; Goodnough, 2004; Greenwood et al., 2003; Kemmis & McTaggart, 2005).

In conjunction with drawing on data, collaborative teacher–researcher research partnerships draw on theory and research (Goodnough, 2004; Gratez et al., 2004). Central to this are investigations of the theories and assumptions which teachers operate under, and the promotion of dialogue between teacher theories and wider theoretical frameworks (Oliver, 2005; Robinson & Lai, 2006). Robinson and Lai (2006) caution that the use of theory falls short if not coupled with practitioners’ critical examination of practice:

[Critical examination of practice] requires dialogue between teachers’ theories of action (…knowledge, beliefs and actions) and external researchers’ theoretical frameworks. In such dialogue, practitioners are required to provide and defend their theories of action. They are also required to use published research to heighten their awareness of other perspectives, provide content for reflection, and develop theoretical justifications … this approach is more likely to foster significant and worthwhile improvements to teacher practice than attempts to disseminate academic research and theory to practitioners without also examining practitioner theory. (p. 198)

Not only should collaborative teacher–researcher research partnerships encourage teachers to engage with published research, in order to be truly collaborative and to promote teacher ownership of, in this case, the building of knowledge, they should encourage teacher dissemination of research findings (Berger et al., 2005; Goodnough, 2004; Robinson & Lai, 2006). However, as Oliver (2005, p. 9) notes, findings from teacher research are “rarely disseminated beyond the teacher-researchers to wider staff”. Findings from one of the schools in Berger et al.’s (2005) study perhaps go some way to illuminating the reasons for this. Teacherresearchers in this school did not share their research with wider staff. They reasoned that if the other teachers had “been curious they’d have asked us”. Conversely, the teachers who were not involved in the research felt that “if there was something important they were learning … they would tell us about it” (Berger et al., 2005, p. 97).

Although the teacher-researchers in this school did not share their findings with wider staff, they did write papers and speak at conferences. Arguably, this is the exception rather than the rule as is a partnership discussed by Gebhard, Harman, and Seger (2007). Gebhard et al. describe ACCELA—a school–university partnership—as differing from other such partnerships in that participants regularly present their data to colleagues, principals, and district administrators as “a way of collectively reflecting on the implications of their work for teaching, learning and policy making across institutional contexts” (p. 421). Sharing research findings and writing for academic and practitioner audiences is a role that most typically is undertaken by academic researchers (Oliver, 2005) and, as such, it is yet another contested/problematic aspect of teacher–researcher partnerships (Kemmis & McTaggart, 2005), one that is linked to dilemmas associated with representation and voice and with deriving mutual benefit from research (Cole & Knowles, 1993).

Whereas, as previous discussions indicate, the role of academic researcher was conceptualised and problematised in various ways in much of the literature consulted for this review, the role and responsibilities of the teacher were relatively unexplored. With the few notable exceptions already discussed, descriptions of the role of the teacher appeared to be mainly limited to data gathering and analysis and to implementing strategies. The opposite is the case in regard to the outcomes of research partnerships. The impact of research partnerships on teachers was explored in much greater detail than the impact on researchers. This could be attributed to most of the consulted literature being written by academic researchers and, arguably, it suggests that researcher–teacher partnerships are often conceptualised as ‘helping relationships’.

Impacts/outcomes of partnerships

In addition to the impacts on researchers and teachers, outcomes of teacher–researcher research partnerships have been conceptualised in terms of schools and of students. The notion of prespecified outcomes as output is problematised by Frankham and Howes (2006), who affirm the importance of process, not just the effects of process.

This point notwithstanding, impacts on researchers that were identified by the literature were mainly to do with researchers “developing a better understanding of the constraints and opportunities of real educational contexts” (Stipek et al., 2001, p. 144). As one teacher in Oliver’s study stated, “I think the most important part of that relationship is the university getting a handle on what the chalk face is” (2005, p. 23). Cousins and Simon (1996, p. 202) did note that researchers also stood to gain intellectual enrichment and revitalisation of their approaches to research, or “new constructs for interpreting phenomena; a more differentiated, reconfigured way of representing processes underlying a given study or research program; and the reconceptualisation of the approach to the research program”.

The impacts on teachers from participation in collaborative teacher–researcher research partnerships are typically framed in terms of teacher knowledge, learning, and practice. As previously discussed, collaboration is considered a powerful professional development tool and one which promotes teacher learning. Although empirical research about how teachers actually learn in collaborative settings has been sparse (Borko, 2004), new frameworks for understanding how teachers question, test, refine, and revise their content knowledge are now beginning to emerge (Davies & Walker, 2005).

A one-year study by Meirink, Meijer, and Verloop (2007) explored the impact on six teachers of their participation in collaborative learning communities. In line with research on teacher learning, Meirink et al. conceptualised learning “as a change in cognition (knowledge, beliefs, attitudes, emotions) that can lead to changes in teaching practice” (2007, p. 147), noting that changes in cognition do not necessarily have to result in changes in behaviour to be labelled learning or vice versa. The impact of teacher participation in collaborative groups was explored in relation to reported changes in cognition and behaviour.

More changes in cognition than changes in behaviour were reported by the teachers in Meirink et al.’s study, who reported only “a small number of practical applications of the methods they had got to know during collaboration with their colleagues” (2007, p. 158). Possible explanations that Meirink et al. put forward were that the methods did not fit in with the work plans the teachers had to follow, the period of the inquiry might have been too short as changes in teacher behaviour require time and effort, or that there may have been issues with the methodology of the study in that self-reports of teachers can result in incomplete information on their changes in behaviour.

Sherin outlines a framework which formulates learning in the act of teaching as occurring as teachers negotiate among “three areas of their content knowledge: their understanding of the subject matter, view of curriculum materials, and knowledge of student learning” (2002, p. 119, cited in Davies & walker, 2005, p. 1). Sherin uses the term content knowledge complexes to describe pieces of subject-matter knowledge that are accessed together repeatedly during instruction and become connected. According to Davies and Walker, this process of interconnection is vital:

If teachers are going to provide students with appropriate … challenges and assist the students to gain meaning, they need to be able to access their own content knowledge whilst engaged in the act of teaching. It is crucial teachers are able to notice the significant … moments and respond appropriately (2005, p. 6).

The development of such attitudes of enquiry towards, and increased awareness of, their teaching can be fostered by collaborative teacher–researcher research partnerships, in that they support teachers to restructure existing understandings and to engage in critical thinking (Corden, 2002; Davies & Walker, 2005; Shulman & Shulman, 2004). Certainly, teacher learning or, as Goodnough (2004) puts it, “teacher knowing”’ is an inherent part of teacher research and learning (Oliver, 2005) and there is “plenty of evidence that suggests that engaging with and in research reenergises teachers” (Saunders, 2004, p. 164) and results in improved knowledge and practice of teaching (Corden, 2002).

Involvement in research partnerships can also develop teachers’ knowledge of research, their conception of self as researcher and their sense of agency as researcher (Oliver, 2005). For example, one teacher in Graham’s study discussed how her experience had allowed her to reconceptualise how she viewed research:

One of the biggest ways I have grown is in understanding how simple it can be to do research. I always thought that for research to be worthwhile I had to have control groups, as well as experimental groups, great statistical numbers and formulas, etc. The simple research done showed me that I had been doing research for years and it was and is worthwhile. All of this made me feel more like a professional who is constantly searching for answers and growing in my job. (Graham, 1998, Mentor Teacher Experiences with Research Partners section, para. 2)

A sobering point is noted by Boles et al. (1999, cited in Berger et al., 2005) who, in an investigation of the potential for teacher research to transform individual teaching practice and to create cultures of inquiry in schools, found that whilst teacher research was transformative for the teachers involved, it had no impact on the cultures of the schools they taught in: “the learning that was taking place inside the teacher research groups was either benignly ignored or actively rejected by the other teachers in the building” (p. 94).

Transfer of teacher learning is, likewise, an issue in relation to TLRI. Specifically, the question is whether the learning transfers to teachers’ future classroom practice, to other teachers in the school, and across contexts (for example. other subjects, students) (oliver, 2005). Learners’ characteristics, training delivery and design, and organisational climate all impact on transfer of teacher learning. In order for research to have impact beyond the immediate classroom it needs to be embedded within the overall school culture, and the school needs to plan for specific ways to use and embed the knowledge in order for it to be useful (Oliver, 2005).

The impacts on students of their teachers’ involvement in research partnerships over the periods of research have been documented as including affective outcomes (Corden, 2002; Frankham & Howes, 2006) and improvements in student practice and achievement (Goodnough, 2004; Greenwood et al., 2003; Lacina, 2006; Saunders, 2004; Stipek et al., 2001). As emphasised by Corden (2002) a whole-school policy and a consistent teaching approach appear to be crucial in maintaining and developing any gains in student achievement.

Within the literature consulted for this review the knowledge-generation outcomes of teacher– researcher partnerships were unclear, and projects that were directly concerned with evaluating teacher–researcher research partnerships appeared to be scarce. As Cousins and Simon noted “data remain thin, and many questions need to be answered” (1996, pp. 199–200). Cousins and Simon’s study was one which did focus on the effects of partnerships between researchers and practitioners. Their approach to their participatory evaluation study on policy-induced partnerships was grounded in the principles of social learning theory (i.e., knowledge is socially constructed and shared meaning will develop through processes of social interaction or processing). Cousins and Simon adopted case-study methodology and employed triangulation strategies reliant on mixed methods and multiple data sources (survey questionnaires, formal and informal semistructured 1:1 and group interviews, nonparticipant observations, indepth case profiles).

Conclusion

Whilst there are inherent tensions in the relationships between teachers and researchers, and aspects of these relationships are complex and problematic, the literature does identify a range of conditions that are critical to the success of teacher–researcher research partnerships.

For example, and to a somewhat surprising extent, leadership support was found to be vital to teacher research. To be successful, especially in the long-term, research partnerships need to be supported by research-driven school cultures which have supportive management teams and a long-term commitment to research projects.

Collaboration, in particular, is viewed as being fundamental to partnerships and distinct from cooperation in that collaborative research partnerships accord equal status to all partners, and are typically underpinned by common values, beliefs, and goals. Ideally, collaborative research partnerships are open, inclusive networks where research is an integrated and owned part of teachers’ experience, and where members, as equals, take different roles at different times.

Many of the tensions, contradictions, and complexities inherent in research partnerships arise from, or are intertwined in some way with, notions of collaboration. Resolution of, or at the very least strengthening of partnerships’ abilities to deal with, complexities and conflicts may require a major shift in conceptions and cultures of research. As noted by Saunders:

Essentially, don’t we need to be shifting the research culture from ‘transmission’— researchers disseminating their outputs—to ‘transformation’—professionals seeking, sharing and creating knowledge and understanding from research informed practice? This is the way to strengthen the ‘connective tissue’ between teaching and research (2004, p. 166).

2. Aims, objectives, and research questions

This project aimed to identify a variety of literacy-teaching approaches that could be used in secondary content-area classrooms to improve the achievement of a wide range of students. Specifically, the project aimed to investigate:

- literacy and the extent to which a focus on improved teacher knowledge and practice would lead to increases in student achievement

- the extent to which research partnerships constituted effective forms of both professional learning and research.

The project set the following objectives in order to achieve the aims described above:

- to deepen understanding of the literacy challenges that students face in the various content areas in order to inform assessment, professional practice, professional development, and the preparation of teachers and to provide future direction for research in secondary classrooms

- to identify, develop, and research the efficacy of a range of pedagogical approaches that could fit within the constraints of the secondary classroom

- to develop the relationship between teachers and researchers in order that research into secondary literacy education is better grounded in the context of the classroom and on the needs of students and teachers

- to support involved teachers to become familiar with the complexities of classroom-based research as a means for the development of their own practice

- to identify and describe the impact of the research partnership as a tool for professional learning.

To these ends, the following research questions guided the project:

- to what extent would a focus on improving literacy teaching practice lead to increased student achievement?

- To what extent would research partnerships support the professional learning needs of teachers in relation to advancing student knowledge and skills to meet content-area literacy challenges and assessment demands?

- what elements of current pedagogical practice positively impact on student achievement?

- how could research partnerships enhance our understanding of a range of practices that would positively affect the learning outcomes of a wider range of students?

- which teaching approaches lead to long-term changes in student literacy behaviours?

In order to achieve these outcomes, the data-collection tools outlined in Table 1 have been used.

These tools are described in more detail in the next section.

| Outcome | Data collection method | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interview | Concept map | Student focus group | Observation/ journal entry | Student assessment | |

| Development of teacher knowledge | X | X | X | ||

| Development of teacher pedagogical knowledge | X | X | X | ||

| Increased student achievement | X | X | X | ||

| Utility of partnership approach as effective PD/research approach | X | X | |||

3. Research design and methodologies

Given the complexity and interrelatedness of the issues affecting change in student achievement resulting from teacher–researcher partnerships, a multimethod design and model of analysis (Denzin & Lincoln, 2005) is required for the evaluation of the efficacy of this project. In this case, and as suggested by Miller and Crabtree (2005), a range of research methods are essential, as are multiple ways of triangulating the data and multiple stakeholders in the form of researchers, teacher-researchers, other teachers, and students.

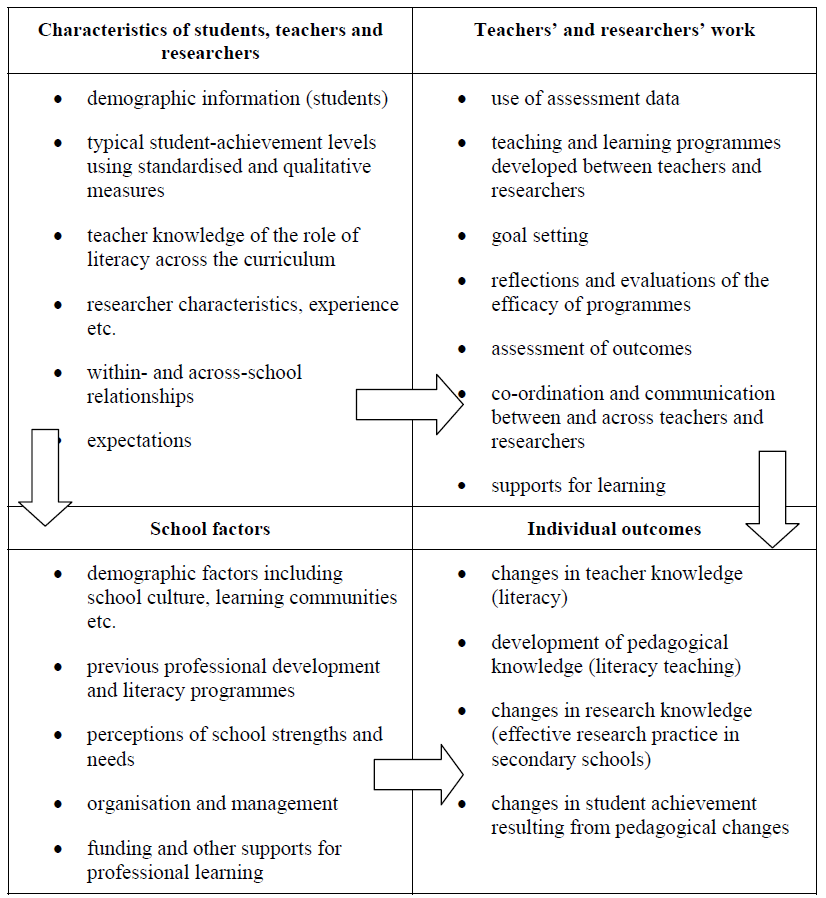

For the purposes of this study, a four-component design was developed at the outset of the projects to guide the development of data-collection tools and the analysis of data collected. This included the description of the characteristics of the participants (students, teachers, researchers) of the project as the independent variables (Miller & Crabtree, 2005); description of the core services of each provider (teachers, researchers) and the context (schools) in which services are provided as the intervening set of variables (Hammond, 1973, cited in Guskey, 2000; Schalock, 1995); and the identification of outcomes (teacher/researcher knowledge, student achievement) as the dependent variable set Miller & Crabtree, 2005). As shown in Figure 1, the effect on each set of variables from the preceding can be described in a linear fashion and is essential to an understanding of the effect of interventions in an individual setting. In the final analysis, the articulation of the links between each set of variables is central to any claim as to the “certainty” and “generalisability” (Schalock, 1995) of the research processes and findings as having applicability to other settings and as tools for change.

Figure 1 Multimethod design and model of analysis

For purposes of our discussion we have differentiated between teacher knowledge and pedagogical knowledge. For our purposes, teacher knowledge refers to the familiarity teachers have with the literature on adolescent literacy, with the challenges facing their students in this area, and with the origin of those challenges ,whereas pedagogical knowledge relates to the ways in which teachers can work with students to raise their literacy achievements

Data collection

The model outlined above required that, alongside the identification of the desired outcomes of the project, understandings be developed of the characteristics of the participants in the project, their various roles, and the contexts within which they work (including the research partnerships) (Hammond, 1973, cited in Guskey, 2000; Schalock, 1995). Consequently, data collection focused on those sources which would provide descriptions of the participants and contexts; facilitate the analysis of the core services of the providers; and assist the identification of outcomes (teacher, researcher, and students).

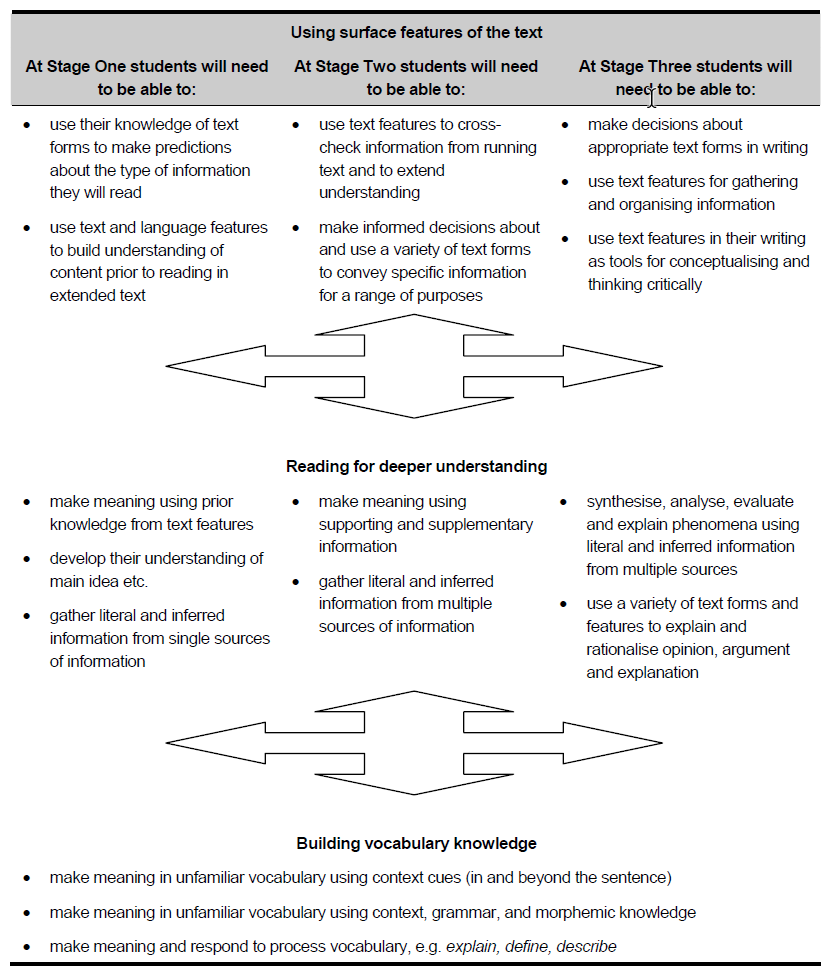

During the design phase for the TLRI projects, discussions took place between the researchers, school management, and teacher-researchers to develop the approach to the literacy investigations to be undertaken. In each instance (discussed in more detail in the findings section) the theoretical base for the investigations was the “scope and sequence” of literacy skills (McDonald & Thornley, 2005). In each school, however, the way in which the efficacy of this tool could be used to increase teacher knowledge and understandings and to raise student achievement evolved as a result of the particular circumstances and aspirations of the school and teacher-researchers. In general the three schools and the projects in them could be described as shown in Table 2.

| School characteristics | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Students | Decile | Size | Location | |

| School A1 | 70% Pasifika, 20% Māori |

2—integrated school |

300 students | Urban, South Auckland |

| Project description | All Year 9, 10, and 11 students over the two years were included in the research cohort. Initially there were two teacher-researchers, who were joined by a third teacherresearcher in year one. Although intended to focus on science and English, the teacherresearcher in science moved to a full-time Bible studies position. As a result of this and the introduction of a literacy option class for Year 9 students in year two, the project focused on developing relevant teaching approaches to enable students to better access text in Bible studies, literacy option classes and English classes. | |||

| School B | 80% Päkehä, 15% Mäori |

5—state area school |

150 students | Rural, Central Otago |

| Project description | All Year 9, 10, and 11 students over the two years were included in the research cohort. While the project was run by three principal teacher-researchers, a whole-staff model of professional development was used to describe teaching approaches and to trial and measure progress across the curriculum. | |||

| School C | 85% Päkehä, girls school |

6—state single- sex school |

450 students | Rural, north Otago |

| Project description | In the first year one low-stream class of Year 9 students, and one broad band of Year 10 students, and in the second year two Year 11 classes were included in the research cohort. These were all English classes. There were two teacher-researchers in the first year, who were joined by technology and physical education heads of department in the second year. Both new teacher-researchers taught numbers of students in Year 11 cohorts. The project focused on developing a range of teaching approaches to raise achievement of a range of students and, in the second year, to develop consistent literacy teaching approaches across English, physical education, and technology. | |||

The principal researchers had established relationships with the three schools. Schools Two and Three had been involved in a longitudinal study with the principal researchers in which a cohort of their students had been tracked through their high school careers. The teacher-researchers in each school had also engaged with the principal researchers on developing teaching approaches arising from the longitudinal research study findings. School A had also been involved with the principal researchers through an evaluation study, and the teacher-researchers there had expressed interest in applying research findings to their largely Pasifika student body. Although not a purposive sample, the diversity of student experiences, the location of the schools, their characteristics and their willingness to be involved made for a useful study cohort.

In order to contribute to the methodological rigour (Patton, 1990) of the study; to address the complex issues (Harry, Sturges, & Klinger, 2005) involved in literacy teaching and learning in the secondary school (Bryant et al., 1999) and in teacher–researcher research partnerships; and to enhance the study’s validity (Stake, 2000) a range of data-collection techniques (qualitative and quantitative) were used. Data sources included concept maps, teacher and principal interviews, observations of classroom practice, documents, student interviews/focus groups, student assessments, teacher journals, and researcher field notes.

Concept maps

Markham, Mintzes, and Jones (1994) used concept maps in their science education programme assessments as indicators of participants’ conceptual knowledge and understanding in relation to a given phenomenon. The researchers argued that the maps provided a site for individual participants to demonstrate the structural complexity of their knowledge about a topic and their precision in conceptualising relationships between elements of that topic. Researchers undertaking qualitative evaluations of professional development programmes in New Zealand and Australia have also used concept maps to show changes in teachers’ understandings and knowledge (Bobis, 1999; Higgins, 2001; Thomas & Ward, 2001).

Concept maps were used to access teacher-researcher beliefs and to examine the extent to which teacher knowledge was restructured over time (Higgins, 2001). The teacher-researchers all participated in concept-mapping sessions with the researchers at three points during the project: the outset of the project, the beginning of the second year, and the end of the project. During these sessions links were made, and conflicts identified, between the perceived skills and needs of students, the context of their schools, and the content and literacy teaching and learning demands of the curriculum.

Interviews

All teacher participants completed interviews at the end of Year I and II that focused on their literacy knowledge, professional learning, and the value of teacher–researcher partnerships.

Senior managers in participating schools were also interviewed in order to ascertain their perceptions of the development and progress of the TLRI partnership’s work in their schools.

The interviews were semistructured in that the researchers had a predetermined set of questions, or interview schedule (see Appendices A and B). However, the style of the questions was openended, allowing for responsiveness to the lead of the interviewee and for some latitude in the breadth of relevance (Freebody, 2003; Harry et al., 2005).

The interviews were recorded using digital recorders and they were fully transcribed. Copies of the transcriptions were returned to the interview participants for verification and/or amendment. The recordings were only available to the research team and the transcriptions were altered to remove any identifying information.

Observations

During the course of the project, the researchers completed a number of classroom observations of the teaching practice of participating teachers using a running record approach in which the researchers described the activities and scripted relevant comments and discussion points. Given the regular visits made by the principal researchers to participating schools, observations took place at least four times annually and were often undertaken over a number of days.

The observations provided a basis for discussions between the researchers and the participating teachers and informed the ongoing professional development and research work. These observations provided important records of teacher change when reviewed over time.

Documentation

- Meeting minutes

The research partnership held biannual meetings where participants reviewed the literature on literacy, professional learning research, and the progress of the project. At these times they also analysed student work and made decisions about teaching and learning goals for the future. The minutes taken at these meetings, together with notes and audio recordings of presentations and discussions, form a long-term diary of the cycle of thinking, reflection, and planning enacted through the meetings.

- Teacher journals

Each participating teacher also kept a journal of their thoughts; questions; findings and their developing understandings about literacy, teaching, and their students. Journals became important reflective tools for teacher-researchers, and they were used extensively in meeting and interviews with the principal researchers. At two schools teacher-researchers also kept regular logs of the quantity and nature of reading and writing tasks they asked of their students.

- Researcher field notes

During the visits to schools and meetings held, the researchers kept detailed notes of findings, reflections, and the discussion points arising.

- Teaching plans

On numbers of occasions the principal researchers taught for teacher-researchers and teacherresearchers have taught for their colleagues. The plans developed for each of these instances, along with the regular planning of lessons and units of study undertaken by teachers, are a record of changed practices.

Student data

- Assessments

Each school/teacher identified target groups of students as described in Table 2. The collection and analysis of assessments and work samples from these groups provided data which served formative and summative needs.

In each of the three schools, target students completed curriculum-based literacy assessments (Education Associates Content Area Literacy Assessments, abbreviated here to EdAssoc) which were designed to identify literacy skills and needs aligning to the scope and sequence of literacy skills (McDonald & Thornley, 2005, see Section 4 for a description). These assessments formed the baseline information from which the teaching approaches trialled in the project developed. Table 3 shows when these assessments were completed, along with the numbers of students participating. Although the total number of students who participated in the assessment are shown, only the results from students who completed more than one assessment were used in the analysis.

In addition to these assessments, and as a means of measuring change in student achievement over time, students completed asTTle reading assessments at the beginning and end of each school year.

| Data Collection Points | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| February 2006 | October 2006 | February 2007 | October 2007 | |

| School A: EdAssoc | Year 9, N=50 Year 10, N=52 Year 11, N=0 |

Year 9, N=41 Year 10, N=53 Year 11, N=25 |

Year 9, N=41 Year 10, N=49 Year 11, N=32 |

|

| School A: asTTle | Year 9, N=34 Year 10, N=21 Year 11, N=16 |

Year 9, N=34 Year 10, N=21 Year 11, N=16 |

Year 9, N=44 Year 10, N=34 Year 11, N=21 |

Year 9, N=44 Year 10, N=34 Year 11, N=21 |

| School B: EdAssoc | Year 9, N=14 Year 10, N=12 Year 11, N=6 |

Year 9, N=15 Year 10, N=14 Year 11, N=13 |

Year 9, N=15 Year 10, N=14 Year 11, N=13 |

|

| School B: asTTle | Year 9, N=13 Year 10, N=12 Year 11, N=5 |

Year 9, N=13 Year 10, N=12 Year 11, N=5 |

Year 9, N=14 Year 10, N=13 Year 11, N=12 |

Year 9, N=14 Year 10, N=13 Year 11, N=12 |

| School C: EdAssoc | Year 9, N=16 Year 10, N=30 Year 11, N=21 |

Year 9, N=21 Year 10, N=22 Year 11, N=24 |

Year 9, N=16 Year 10, N=18 Year 11, N=0 |

|

| School C: asTTle | Year 9, N=14 Year 10, N=19 Year 11, N=8 |

Year 9, N=14 Year 10, N=19 Year 11, N=8 |

Year 9, N=17 Year 10, N=14 Year 11, N=11 |

Year 9, N=17 Year 10, N=14 Year 11, N=19 |

Note: Year 9 students from 2006 become the Year 10 group in 2007; similarly, Year 10, 2006 become Year 11, 2007.

- Student voice

In each of the target classes, focus groups of students were convened to discuss their perceptions of their literacy challenges along with the approaches to teaching which they felt supported their learning. These meetings were held on an annual basis. At School C students were also surveyed regularly about their literacy learning.

Ethical approval