Introduction

How can educational experiences in public spaces such as museums, libraries, and eco-sanctuaries support learners to address pressing social, cultural, and ecological issues? Working with four primary teachers and two secondary teachers, their ākonga (Years 3–10), and educators from 10 providers of learning experiences outside the classroom in the Wellington region, this project investigated how the cross-curricular themes of “future-focused issues” (Ministry of Education, 2007, p. 9) and active citizenship are conceptualised and enacted through education outside the classroom. It explored how ākonga relationships with people and places beyond the school environment can stimulate their engagement with wider societal concerns.

The challenges ahead for our young people and Aotearoa as a society—such as climate change, inequality, and the ongoing effects of colonisation—are pressing. These challenges, or future-focused issues, provoke ongoing debates in society, differing judgements and passions, and competing recommendations for change (Milligan et al., 2016). “Wicked problems” such as climate change are highly interconnected with other issues and resist simple, once-and-for-all solutions (Bolstad, 2011; Papprill, 2016). Teaching for critical and active citizenship invites learners to consider and respond to these issues for themselves, in relation to their own life-worlds, in contrast to learning experiences that affirm the status quo by positioning children and young people as passive recipients of pre-packaged meanings and conceptions of social change (Harcourt et al., 2016; Westheimer, 2010).

It is “recognised [that] learning both inside and outside school encourages young people to be capable and knowledgeable citizens, who are involved with the communities they live in” (Ministry of Education, 2016, p. 4). Education outside the classroom provides valued and unique experiences that extend the curriculum and hold considerable potential to support children and young people’s engagement with pressing issues, particularly because sites and spaces such as memorial parks, zoos, and art galleries reflect ideas about our society and can contribute to debate and change. In this study, for example, a visit to Zealandia Te Māra a Tāne reinforced learners’ commitment to conservation, and another to Pukeahu National War Memorial Park invited consideration about the relationship between conflict and who we are as a nation. These visits were part of a learning arc, defined in this project as the intentional connections made between pre-, during-, and post-visit learning to support critical and active citizenship.

This research addressed the question: How can collaboration between teachers and educators better assist learners to respond to future-focused issues through education outside the classroom? Very little research has considered how education outside the classroom can elevate learning to focus on issues, and an even smaller pool of literature has examined how it can enhance learners’ active citizenship. This study builds from a small but growing body of guidance (e.g., Ministry of Education, 2016, 2021; Ministry for Culture and Heritage, 2016) and research evidence about effective education outside the classroom practices in Aotearoa (e.g., Eames et al., 2006; Eames & Aguayo, 2020; Hill et al., 2020; Milligan & Rusholme, 2016; Moreland et al., 2006; Williams, 2012). Much of the existing research literature focuses on either teacher or educator perspectives and a small slice of a learning arc, such as the visit. In contrast, this study captures the complexity of collaboration across multiple actors and sites. This research provides insight into how closer collaboration between teachers and educators, and stronger connections between learning experiences inside and outside the classroom, can support children and young people’s critical, creative, and democratic engagement with issues that face them and Aotearoa.

The key findings in this report related to three “Cs” or sub-questions that guided the research:

- Conceptions: What meanings and practices do teachers, educators, and students associate with futurefocused issues and active citizenship through education outside the classroom?

- Connections: What kinds of experiences enable learners to make connections across formal and informal educational settings, explore wider societal debates, and offer spaces for response?

- Collaboration: What forms of collaboration between teachers and educators best support learners to critically and creatively respond to future-focused issues?

Collaborative action research methodology

This qualitative study used a collaborative action research methodology (Carr & Kemmis, 1986; Locke et al., 2013; Sinnema et al., 2011). Study participants included ākonga (n = 151) and teachers (n = 6) from three urban primary schools and one secondary school in the Wellington region. The study also included educators (n = 21) from Dowse Art Museum, City Gallery Wellington Te Whare Toi, Zealandia Te Māra a Tāne, New Zealand Police Museum, Wellington Museum Te Waka Huia o Ngā Taonga Tuku Iho, Pukeahu National War Memorial Park, National Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, Wellington Zoo, Capital E Nōku te Ao, and New Zealand Parliament. Four university research mentors led the project and supported the collaborative inquiry. To protect participant anonymity, pseudonyms are used for students, teachers, schools, and educators in this report.

To the extent possible, the teachers, educators, and university research mentors were jointly engaged in co-constructing two cycles of planning, action, and reflection. In 2019 and 2020, reflection and planning (RAP, Table 1 below) teams formed around each participating class’s learning context and the visit sites that had been negotiated between teachers and educators. Each learning context and the associated RAP team formed the boundaries of eight “cases” (Stake, 2006) across the 2 years, tied together through common research questions.

| Ākonga from | Teachers | Ākonga year levels | Number of ākonga | Research mentor | Educators from |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Miro School 2019 |

Anna |

Years 4 & 5 | 26 | Frank |

Wellington Museum |

| Miro School 2020 |

Anna |

Years 4 & 5 | 25 | Frank | Parliament, New Zealand Police Museum |

| Karaka School 2019 |

Tony |

Year 10 | 28 | Kate |

Te Papa, Zealandia Te Māra a Tāne |

| Karaka School 2020 |

Leslie |

Year 9 | 27 | Kate | Pukeahu National War Memorial Park, Zealandia Te Māra a Tāne |

| Whārangi School 2019 |

Louise, Jane |

Years 3 & 4 | 21 | Sarah |

Wellington Zoo, Pukeahu National War Memorial Park |

| Whārangi School 2020 | Louise, Jane |

Years 5 & 6 |

9 |

Sarah |

The Dowse Art Museum, Te Papa |

| Akeake School 2019 | Janet |

Years 5 & 6 |

9 |

Andrea |

Wellington Zoo |

| Akeake School 2020 | Janet |

Years 5 & 6 |

6 |

Andrea |

Parliament, Te Papa |

A deliberately broad cross-section of organisations were invited to participate, giving teachers a wide range of visit options. The wider project group included all educators who attended seven project hui, shared their understanding about the project and its themes, learnt from each other’s expertise, and reflected on emerging findings, regardless of whether the sites they represented were visited as part of the project. Educators at sites selected by teachers committed to collaborative action research cycles. RAP groups (teacher(s), educators, and a research mentor) developed and evaluated learning arcs, strategised programme delivery, and reflected on the process. A key research focus was the outcomes for a small group of ākonga at each school. Insights from the first year enabled RAP groups to refine and transfer interventions to new learning contexts. The frequency of RAP group meetings varied depending on the group, but all met at least once at the beginning and, with one exception, once at the end of each learning arc. RAP discussions typically continued through email exchanges.

A research framework, inspired by Martha Nusbaum (Hipkins, 2017, 2019) and others and co-constructed with teachers, was developed to notice shifts in learning in relation to learner inquiries. The framework included four capabilities: making meaning through disciplinary learning; using emotions as a productive force for change; navigating perspectives and representations; and contributing as citizens (see Appendix A). The framework enabled a retrospective focus on what the learning ecosystem enabled ākonga to do and be throughout the learning arc; that is, the learning outcomes. It also supported teacher and educator planning by directing this towards future-focused issues and active citizenship, providing examples of what teachers and educators might ask and ākonga might express in relation to each capability throughout the learning arc.

A range of data sources provided a rich description of the learning arcs and outcomes (Table 2 below). Data collected in the wider team planning and reflection phases included research mentor, RAP, and project hui audio recordings and notes. Each year, teachers and educators participated in semi-structured group interviews of approximately 45 minutes that explored their conceptions and practices of education outside the classroom, active citizenship, and issues-led learning. Data from the “action” phases (cycles of pre-, during- and post-visit planning, action, and reflection) included audio-recorded RAP meetings, teacher and educator planning documents, and student work samples. Student work samples included “exit activities” completed at the conclusion of the visit or upon return to school (see Table 2) and an extensive, contextually variable range of learning artefacts including student presentations, photographs, and written tasks (not recorded in Table 2). Semi-structured focus group interviews of 30–40 minutes with ākonga were conducted before the visit and, where practicable, 4–6 weeks after. The pre-visit interviews asked ākonga about their prior learning, the purpose of the upcoming visits, and the kinds of learning connections they anticipated making. The post-visit interviews asked about the value of the visit, including the feelings it evoked, stories/ perspectives that were shared, and the next steps and actions the visit prompted.

Semi-structured observations were conducted for each site visit using a standardised form designed for the systematic collection of qualitative data by multiple researchers on predetermined categories of interest. Observations were made about length of visit, group composition, and spatial movement through the site. Researchers also observed the activities and topics engaged with; the learning intentions (either explicit or implicit); the educator’s delivery style (for example, explaining and/or open versus closed questioning); transitions and reflections between activities; teacher participation; student engagement; examples of capabilities; and external factors that may have impacted the experience such as noise, weather, other visitors, etc. Most visits had two observers working simultaneously to help mitigate the potential “observer effect” of having a single observer. At the end of each visit, observers recorded “debriefing” notes detailing any initial and/or overall impressions.

| Phase 1, 2019 | Phase 2, 2020 | |

|---|---|---|

| Teacher and educator focus group interviews | 5 | 6 |

| Project hui recordings and notes | 9 | 3 |

| Research mentor hui recordings and notes | 13 | 13 |

| RAP team meetings recordings and notes | 14 | 12 |

| RAP planning documents | 8 | 5 |

| Visit observations | 7 | 8 |

| Student exit activities | 4 | 5 |

| Student pre/post focus group interviews | 10 | 9 |

Project meeting and interview recordings were transcribed and analysed using constant comparison and thematic analysis methods (Braun & Clarke, 2006). Visit co-observers worked together to combine their notes in one document post-visit, then one researcher created a combined spreadsheet that included a summary of each visit. This summary spreadsheet was checked by all research mentors to ensure verisimilitude. It was then used to make cross-visit comparisons across the various categories of interest and functioned as a convenient reference document for comparing the observation data with other data sets for each of the case study groups. Deductive within-case analyses were conducted for each school using the capabilities and a set of open-ended, standardised questions derived from the research questions, and the teachers checked and provided feedback on a summary of these analyses. Cross-case analyses (Bruce et al., 2011; Stake, 2006), using a summary of within-case themes and two ranking exercises, were then used to compare and contrast cases.

Key findings

Two overarching findings emerged from this study. First, the most effective learning arcs involved teachers and educators working together in a shared direction of travel. This demanded high levels of flexibility and adaptability and involved time, relational trust, and a willingness to be responsive to evolving learning designs. Second, how teacher and educator practices articulated, or worked in, with each other mattered. Effective learning arcs integrated the capabilities across the pre-, during-, or post-visit phases, and fueled students’ interests in issues they had identified and felt genuinely puzzling or urgent for them. The visit experience particularly nurtured the “contributing as citizens” capability by attending to ākonga identities, belonging, and participation skills as citizens, and focused on what students could do with their learning.

The following sections are organised around the research sub-questions and highlight key findings from this study that relate to: (a) how educators, teachers, and ākonga conceived education outside the classroom as well as its relationship to critical and active citizenship; and (b) the teacher and educator practices and interventions that were most effective in elevating the learning arcs and supporting ākonga to engage with issues and consider how they could contribute to change. Three visits appeared to have an enduring effect on learning. Many other learning arcs held strong potential, most notably in the planning stages. Even where there was less evidence of visits having contributed to enhanced learning outcomes, there were compelling examples of conversations and pedagogical approaches that hold promise for future iterations of learning designs; for example, creating opportunities for ākonga to consider and critique children’s representation in the visit sites.

Conceptions and practices

This section shares key findings about the meanings and practices that teachers, informal educators, and students associate with future-focused issues and active citizenship through education outside the classroom. We found that:

- teachers and educators viewed education outside the classroom as a complex learning ecosystem

- teachers and educators hold different views about the nature and place of future-focused issues and active citizenship in education outside the classroom. Discussion and agreement about where and how these dimensions will feature in the learning arc is important

- ākonga are better supported to explore and respond to social, cultural, and ecological issues when a “curriculum immersion” approach is taken to feeding learner inquiries.

A complex learning ecosystem

The teachers and educators conceptualised education outside the classroom as a learning ecosystem that included schools, providers, and other places in the Wellington region and beyond. The metaphor of a learning ecosystem, contributed by one educator in a project hui, resonated with the wider group because it dissolved what felt like overly stark distinctions between, for example, classrooms and their school communities, and formal education (“inside the classroom”) and informal education (“outside the classroom”). It instead recognised a web of existing, new, and potential relationships within and between places and people in the student’s local and wider community. One educator commented that providers could offer access to other experts, staff, and taonga in their site and networks to enhance the learning. At Te Papa and Zealandia, this consideration was extended to include guest speakers from within, or connected to, the organisation who could offer specific insight or expertise. The metaphor also recognised the connectedness of learning experiences that involve children and young people, their teachers, and educators and the whole learning ecosystem as nourishing rich, authentic, experiential and provocative learning that “can’t be googled”. Multiple learning pathways or “arcs” were enabled by this ecosystem. The learning arcs most often connected schools to more than one site, which meant that there was more than one pre-, during-, or postvisit phase. The learning arcs also included other experts, community resources, and providers who did not participate in this study.

The complexity of the learning ecosystem was a notable theme in project hui and RAP discussions. Teachers and educators felt that creating effective learning designs within this ecosystem was challenging because it involved working across differences in organisational affordances and constraints, professional practices and values, and school needs and interests. Educators, for example, noted that organisational funding, priorities, and offerings shaped the programmes they could provide and the freedom or capacity they had as educators to meet learning needs. A challenging aspect of their work, as educators saw it, was being responsive to local curricula. The curriculum diversity among the schools in this study was indicative of the challenges they faced. The teachers were part of distinctive, innovative learning and teaching communities that were exploring different pedagogical and inquiry approaches (see Table 3), the focuses for learning varied widely across school contexts (see Table 4), and each inquiry evolved considerably during the learning arc. All providers had created durable and flexible programming but adapting (and in some cases creating new) programmes to meet the needs and interests of schools and learners was a sophisticated undertaking. The complexity of the learning ecosystem was also heightened by staffing turnover among providers, and changes in teaching personnel, student cohorts, and learning contexts within the life of the project. This meant that each learning arc had a high degree of novelty and, in short, nothing stood still. As one educator noted, flexibility and design thinking were needed on the part of teachers and educators.

| School | Overarching pedagogical approach | Inquiry approach |

|---|---|---|

| Miro | Place- and community-based | Guided and student-led |

| Whārangi | Place- and community-based | Guided and student-led |

| Akeake | Play-based | Student-led |

| Karaka | Social inquiry | Teacher-led and guided |

Different views about the nature and place of issues and active citizenship

Teachers and educators held a wide range of conceptions about the nature and place of future-focused issues and active citizenship within education outside the classroom. All the educators believed that their sites contributed to societal debates, despite society sometimes changing faster than their institutions. However, some educators and teachers found it challenging to see how the visits could be used as a stimulus for exploring wider societal issues. Some educators were concerned that focusing on issues could narrow the learning or be emotionally charged for children and young people. Many sites also had strong perspectives with regards to sustainability (e.g., Zealandia, Wellington Zoo) or citizenship (e.g., Parliament, Police Museum). This was an advantage where the site’s perspective aligned with the inquiry question; for example, the question “Who has a voice? Who doesn’t? How can we challenge or change this?” aligned well with Zealandia’s focus on giving a voice to nature. Educators noted that there were sometimes tensions between their personal beliefs and their organisation’s aims, agendas, and ethos. Nevertheless, they stressed that educators can in many instances play a vital role in adding an important layer of critical engagement and connection to wider social, cultural, and ecological issues, though this was not always evident to or welcomed by teachers outside this study.

In general, the teachers were more open to presenting challenging or difficult issues to ākonga than the educators. This was evident in the learning contexts (Table 4), all of which offered opportunities for ākonga to explore societal contentiousness and/or social action. The learning contexts were meaningful in the lives of ākonga and their communities and made connections to societal issues within their sphere of influence rather than directly “about” wider global, social, and cultural issues. Ākonga held different degrees of awareness about the connection between their inquiry questions and wider issues and the teachers stressed the importance of knowing their learners in order to decide how to make these connections. In Whārangi and Akeake Schools, for example, ākonga had engaged with issues of homelessness, the local built environment, and global food security prior to and during the project. Anna noted that issues for some of her ākonga “in survival mode” were much closer to home. However, she felt that all her ākonga had “a growing understanding that they have a part to play in their family, school, community and world … [and that] they have a responsibility to play the part” (Teacher focus group interview 1, 2019).

| School/Year | Learning contexts | Examples of key concepts explored | Connections to wider societal issues |

|---|---|---|---|

| Miro School 2019 | How can we tell missing stories to impact the future? | Stories/narratives Perspectives Kaitiakitanga Injustice |

Colonisation Silencing |

| Miro School 2020 | How can I best contribute as a citizen? | Rules and laws Rights and responsibilities Fairness |

Student-selected issues around citizenship |

| Karaka School 2019 | What are the challenges and opportunities of tiaki? | Cultural and environmental tiaki Decision making |

Colonisation Ecological protection |

| Karaka School 2020 | Who has a voice? Who doesn’t? How can we challenge or change this? | Voice Perspectives Dissent Representation |

Conscientious objection Ecological issues (such as granting of legal personhood to waterways) |

| Whārangi School 2019 | I have a voice. What do I want to say? Is it true that community makes a stronger world? |

Perspectives Values Voice Contribution |

Homelessness Deforestation Conservation Animal rights and welfare Community action Colonisation |

| Whārangi School 2020 | Do we need to share our culture to honour it for the future? What difference does this make to all of us? |

Perspectives Stories/narratives Value Voice Cultural tiaki Contribution |

Connections to individual and shared cultures Recognising and speaking their stories The significance of keeping stories alive |

| Akeake School 2019 | How can we design spaces that meet the needs of humans and animals? |

Collaboration Design Space shelter Interaction |

Conservation Animal rights and welfare Adultism |

| Akeake School 2020 | How can we create a student council to act on opportunities to benefit others? | Collectivism Resistance and change Rights and responsibilities Organisation and leadership Representation |

Youth voice |

Developing dispositions and capabilities for responding to issues of concern was of primary importance to the teachers. The notion of transformative learning held appeal because it spoke to the interactions between personal and societal change, and teachers valued the educators modelling commitment and passion in this regard. However, many teachers were reticent about how far social action could be taken, in an ageappropriate way. Louise and Jane, for example, wrestled with “not wanting to push kids beyond what they’re ready for” (Teacher interview 1, 2020). Tony also questioned the extent of learners’ individual agency in the face of enormous global issues. He asked, “Are we dismissing the importance of having a shift in thinking or just raising your own awareness? That has to be a precedent before taking action” (Miro, RAP4, 2020). These teachers wondered whether developing social consciousness and shifting perceptions were more appropriate aims. Nevertheless, and echoing a sentiment that was common to the primary teachers in particular, Louise and Jane reflected that “we do it [encourage social action] anyway” and had been surprised about what their ākonga had been capable of (Teacher interview 1, 2020).

The educators held a wider range of conceptions of active citizenship—ranging from an absence of vocabulary to describe its relationship to their practice, to the belief that this was better explored in the classroom, through to developing a programme that enhanced students’ sense of belonging and capacity to contribute to change. The relationship between the educators’ practices, their organisations, societal issues, and active citizenship moved between:

- advocacy: focused on solutions to an issue or predetermined acceptable behaviours

- critical consciousness: perspectives and issues were explored critically and/or a range of possibilities and skills for action were considered

- neutrality: contentiousness and the subject of social action were absent or muted.

Educators who took an advocacy or critical consciousness approach played an important role in supporting learners to engage with and respond to societal issues. Some sought opportunities to highlight connections to learners’ concerns at features and locations within the site and were careful to ask which issues would be appropriate to discuss with the students before the visit. At Wellington Museum, the Dowse Art Museum, and Pukeahu National War Memorial Park, educators prompted ākonga to notice stories and representations that were present or missing in exhibition spaces—adding a layer of criticality that was not immediately obvious to ākonga. Other educators provided ākonga with valuable conceptual material that could support their social actions; for example, by adding ideas to their skills toolbox at Parliament, making a choice to support sustainable products at the Zoo, or exploring examples of past protests at Te Papa. Importantly, educators did not attempt to do everything: what mattered was agreement between teachers and educators about where and how future-focused issues and active citizenship—including the skills of criticality, perspectival thinking, and social action—would be foregrounded across the learning arc.

Using a curriculum immersion approach

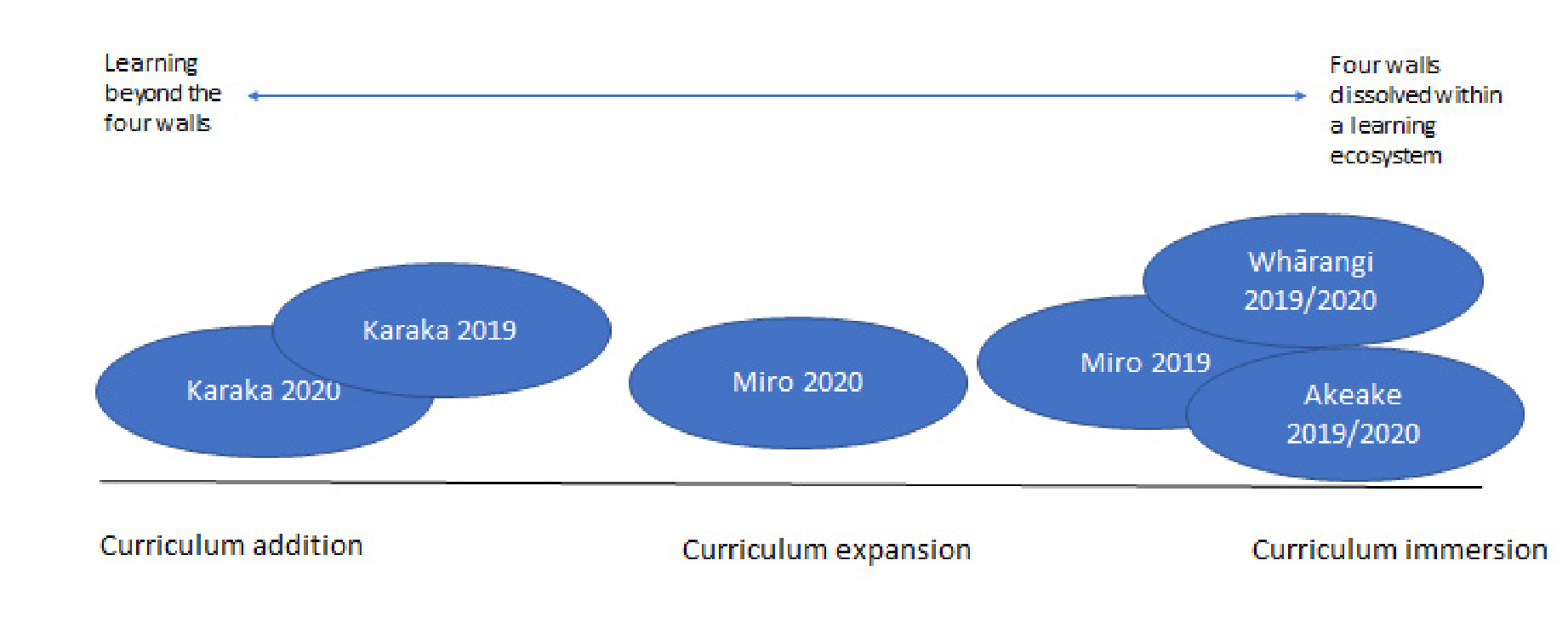

How teachers thought about and linked the curriculum to learning opportunities outside the school shaped learner expectations about what could be gained through visits and made a difference to outcomes for ākonga. Some approaches were more effective than others. At one end of a continuum (see Figure 1), an “additive” approach involved teachers seizing the opportunities that the project afforded to supplement the learning and teaching programme. These visits were characterised by teachers casting the net on behalf of their students; that is, being open-minded about outcomes rather than conceiving the visit as being integral to a pre- and post-visit learning design. A “curriculum expansion” approach involved teachers selecting sites with a clear eye to the conceptual connections the visit could support and capitalising on the experience across the learning arc. An “immersion” approach also focused on learning that lay behind the scenes, including understandings about the nature and purposes of the sites, access to expert knowledge that wouldn’t have been available had students visited as members of the public, and opportunities for students to give voice and expression to their concerns, identities, and agency. The approach was typified by guided or student-led inquiries, high levels of engagement with the local community, and ākonga having stronger input into the learning direction, learning processes, and visit site selection.

A curriculum immersion approach was the most satisfying for ākonga because: (a) they could see themselves in the learning; (b) they held expectations that the visit would add to their learning, over and above it being an enjoyable experience; and (c) it was performative; that is, they could see how they could apply what they had learnt from the visit. Janet reflected on the importance of this:

I don’t want to take them somewhere for the sake of it. I want to be maximising their experience. You want the students to be active with their learning; that is, what’s going to inspire you when you come back to school? What can you do with this? (Akeake, RAP2, 2020)

FIGURE 1: How teachers made links between the curriculum and visit experiences

Ākonga whose teachers took a curriculum expansion or immersion approach typically expected more from the visit in terms of the questions they asked and their expectations for new learning. For these ākonga, connections between their learning at school and the visits was clear: they knew why they were at each site and came eager and ready to learn. This was particularly evident when ākonga played an active role in determining which sites to visit. The use of clearly articulated focus questions prepared Whārangi School students to be on the lookout for ideas and responses during visits to the Zoo and Pukeahu in 2019 (see Table 2 above). At Pukeahu, for example, the students made a strong connection to the effects of colonisation, expressing anger, sadness, and solidarity with a member of the group who is mana whenua. As Jess expressed:

The fact that when the settlers came and destroyed the Māoris’ garden. That was an important food source them. That connects to what some of us have been doing because that might have been a really important source of food for them. (Whārangi student interview 2, 2019)

This and other new learning at both sites fuelled the students’ understandings of the connections between injustices, strong communities, and how they could use their voice to contribute to change.

In contrast, pre-visit interviews with ākonga whose teachers took a curriculum additive approach revealed that ākonga were less clear about the purpose of upcoming visits. Their expectations focused on what they might encounter at each site, rather than what they might learn or draw from them. These ākonga also tended to take a more passive approach during visits, often positioning themselves as recipients of learning rather than active participants. Noticeably, while these ākonga certainly valued and enjoyed many of their on-site experiences, they did not see them as being central to their inquiries or, in some instances, that they had any influence on or relevance to subsequent learning. This disconnect emphasises the importance of the teacher and ākonga co-constructing and holding the learning arc.

Connections

This section shares key findings about enhancing learning connections across formal and informal educational settings. Ākonga are better supported to explore and respond to social, cultural, and ecological issues when:

- the coherence between pre-, during-, and post-visit learning is made explicit to ākonga

- an overarching question or provocation anchors the learning arc

- selective and rich use is made of the visit site to promote critical, perspectival thinking

- visits enfranchise ākonga by enhancing a sense of belonging and capacity to take action.

Creating and maintaining coherence across the learning arc

A key factor in crafting a “connected, cohesive, and cumulative experience” (Charitonos et al., 2012, p. 3) for ākonga was ensuring that the coherence between pre-, during-, and post-visit learning was obvious. When the thread of learning became too thin, ākonga found it hard to make connections between the visit sites, their learning, and their own lives. The teacher played a critical role here in terms of setting up the learning, supporting ākonga to personally connect with the participatory aspects of the learning, and ensuring that ākonga were on board with the value and purpose of their upcoming visits. The educators also had a role to play in creating a reflective end point to the visit experience that would connect to post-visit learning.

Most visits ended with a pre-planned reflective activity that connected to the learning inquiry, although timing issues meant that this was sometimes rushed or not completed on site, instead being handed over to the teacher to complete back at school. Well-executed exit activities firmed up connections between the visit and the inquiry focus, reinforcing what ākonga had been learning about, and supporting them to make personal connections to the learning. For example, at Wellington Museum, the reflective questions “If you could tell any story in this space what would it be? If you could tell any story about your family, what would it be?” provoked a lot of discussion amongst ākonga, teachers, and parents. The teacher used this question as the basis of further discussions and responses back at school.

Using an overarching question or provocation to anchor learning

A strong, authentically co-constructed overarching question or conceptual focus provided an anchor point for the learning arc. The strength of this overarching question or big idea played a critical role in the success of the learning experiences. Overarching questions that resonated with teachers and educators provided fertile ground for identifying meaningful connections across sites. Most importantly, well-crafted questions invited and encouraged ākonga to explore issues of relevance to their own lives and communities. For example, the inquiry question “How can I best contribute as a citizen?” immediately positioned ākonga as active contributors to their communities while also signalling that developing skills, knowledge, and experience can contribute to the efficacy of their social actions. Some sites built on emotional responses in relation to the inquiry question, and, where this happened, students’ critical and creative responses to the future-focused issues in their inquiry question were enhanced.

Disciplinary concepts that underpinned the overarching question provided another important bridge between school and sites and connecting concepts across and within sites enriched and expanded student understandings. For example, in a pre-visit RAP meeting, the teacher and educators discussed a bundle of concepts that would enrich Akeake School students’ interest in promoting youth voice. At the start of their visit to Parliament, ākonga were told that they would be talking about laws, change, rights, and responsibility. Students were invited to contribute their own ideas and connections based on learning they had done at school. The concepts were returned to in various locations within Parliament, with connections made to the importance of debate, public participation in government decision making, and the skills required to create change. Like the overarching question, it was essential that these key concepts were introduced prior to the visits and educator attempts to make connections with learning at school understandably fell flat when student pre-exposure to the concepts was limited or non-existent.

For educators, aligning the overarching question, learning intentions for the visit, and questioning was an important way to establish and strengthen explicit connections between school and their site. On most visits, the overarching question formed the basis of stated learning intentions. For example, in a visit to The Dowse, the educator explained that the students would be exploring how stories are told (the focus of their inquiry), then expanded on this by explaining that ākonga would be “looking at ways that museums work really hard to honour stories” including “the mistakes we have made in the past” and “what we are still learning”. Clearly stated learning intentions that were reiterated and scaffolded meaningfully throughout the visit supported ākonga to build on their prior knowledge and ensured that the purpose of the visit was linked to their unfolding inquiry. Post-visit interviews showed that ākonga did not automatically connect visit experiences to personally or socially significant issues. In these instances, the work that took place back in the classroom played an especially important role in connecting the site visit to wider societal issues.

Effective (focused, open-ended, critical, and scaffolded) questioning supported students to make connections between prior knowledge, the focus for learning, and the site. These connections were most evident when questions were planned in advance, with clear conceptual connections to the overarching question, and when the teacher and educators co-constructed questions that could be asked at different stages of the visit. There was a clear emphasis on educator-directed questions across all of the visits. “In the moment” questions tended to be more closed in nature, or too open and unsupported, and opportunities to use questions to probe students’ prior understandings or prompt deep learning were not always taken up.

Teachers and educators found the capabilities framework useful for orientating visits towards future-focused issues and active citizenship. Many educators were already unconsciously incorporating aspects of the capabilities into their regular programmes, but this deliberate focus encouraged educators to make them more explicit and often deepened or challenged the messaging of their programmes. However, because the framework was new to the teachers and educators, giving full expression to the capabilities was difficult, particularly regarding levelling the capabilities appropriately for the students. Some site visits considered the capabilities at a surface level, while others assumed prior knowledge or skills the students didn’t have. “Making meaning with disciplinary concepts” was integral to all learning arcs, and the most productive planning discussions centred on identifying the concept or bundle of concepts that educators would focus on in the visit. “Contributing as citizens” was the most evident capability in primary school learning arcs, and “navigating perspectives and representations” in secondary students’ learning. Inquiry questions and visit learning intentions tended not to foreground “using emotions as a productive force for change”, and there was less evidence of emotional responses in visit experiences adding to a sense of wanting to bring about change. Affective connections tended to be established and nurtured in the school environment.

Effective use of the visit site

The targeted use of space in the visit site, and deliberate attention to taking advantage of the space to deepen and enrich the purpose of the visit, strengthened the coherence of the learning experiences and in some cases encouraged educators to use their sites in new ways. In planning meetings, educators and teachers discussed which features or locations within their site would best lend themselves to exploration of conceptual understandings and to critical, perspectival thinking. In the most effective visits, educators carefully considered the progression of learning, including how features of the site itself could add a fresh dimension to the exploration of key ideas and concepts. In other visits, a considerable amount of time was spent in classroom-like spaces, instead of educators capitalising on the rich offerings their sites provided.

Across all visits, links between the site and the overarching question were generally made through educatordirected approaches, with less attention paid to supporting ākonga to independently explore sites in deliberate or critical ways (noting that in sites such as Parliament, independent exploration is not an option). In some instances, ākonga were given opportunities to free roam, with little or no connection made to their inquiries, either in terms of how the purpose of the free time was presented or in how it was unpacked afterwards. Sometimes this exploration allowed ākonga unfamiliar with the site to become more comfortable or to unleash their curiosity about the site. Most often, however, valuable opportunities for ākonga to read the sites, develop their own questions or ideas, or make connections with the purpose of the visit slipped to the wayside.

An important aspect of the targeted use of space involved supporting critical and perspectival thinking in and about the site. The focus on capabilities encouraged educators and teachers to consider ways in which the visits could support ākonga to navigate perspectives and representations, including examining the roles of the institutions themselves. In some cases, examining perspectives was the primary focus of the visit; for example, at Pukeahu, ākonga explored which voices were missing in the war memorials. In post-visit interviews, these ākonga reflected that their understanding of the memorial site had shifted, identifying the invisibility of those who object to war. This exploration could have been strengthened by further exploration of why these voices were missing, how it benefits institutions to display dominant narratives, or what the consequences of missing narratives might be.

Enfranchising ākonga

One of the most compelling findings was that the strongest learning arcs placed student voice and agency at the centre, with visits enfranchising ākonga by enhancing their sense of belonging and capacity to take action. Central to this was ensuring that learning experiences connected with issues and ideas that mattered to ākonga, with a clear emphasis on active citizenship or ways to apply their learning. For example, Akeake School students visiting Parliament could identify ways in which the visit deepened and focused their understanding in relation to their own roles on the student council. For example, one student stated that:

It was a good experience knowing that a council can be based off another council that runs well. So, when we went to Parliament, I felt like it was an example of what we should do … having the ministers to suit us is a good idea because not all the ministers will suit our school values. (Hana, student interview 3, 2020)

In particular, the concept of representation had a profound effect on how they established their student council. The students decided on ministers for roles that represented the student body and that other students had asked for. They saw the potential education outside the classroom holds in supporting active citizenship and, because of the visit, viewed Parliament as a place to start a conversation about ideas. Noticeably, when an issue held meaning for students, they made their own connections across sites even when this was not the primary purpose of the visit; for example, identifying responses to climate change.

Student voice and agency were also supported through a range of educator pedagogies that enhanced the educator–ākonga and ākonga–ākonga learning relationships. Ākonga who had previously visited a site (e.g., the Wellington Zoo, Zealandia, or Parliament), or who had previous positive experiences as museum or gallery visitors, showed greater confidence in the spaces. Educators who greeted ākonga outside the site and explained how the visit would unfold played an important role in bridging the gap for students who were unfamiliar with, or potentially intimidated or overwhelmed by, the visit site. Ākonga noted that the learning activities they enjoyed the most involved student–student interaction. These interactions helped develop their relationships while also supporting their learning. Many ākonga also reflected enthusiastically on personal stories told by informal educators or guest speakers, or on presenter knowledge or passion, and particularly responded to stories about other young people who had taken action and made a difference.

Collaboration

Teacher–educator–ākonga relationships and collaboration are vital. Ākonga are better supported to explore and respond to social, cultural, and ecological issues when:

- shared planning processes interrogate and enrich connections to an overarching question and strengthens educators’ knowledge of students

- communication is responsive to evolving learning designs, especially shortly before the visit

- teachers and educators actively negotiate roles and build and maintain relational trust

- students are involved as partners in the learning arc

- teachers and educators contribute to each other’s professional growth.

Robust pre-planning discussions

Learning outcomes were strongly influenced by the extent and quality of collaboration between teachers and educators. Ideally, each visit was preceded by an initial planning meeting, either in person or online, and usually with educators from all related visit sites present. The focus was on developing a shared understanding of the overarching inquiry, key concepts and capabilities being explored, and then working together to construct a map of how the visits would unfold. In almost all cases, the planning meeting felt generative for both the teachers and educators. One teacher from Whārangi School noted that:

I was surprised by the richness of our planning conversations, and in both conversations our planning changed quite significantly as a result of the conversations from what we all expected, and it became something else … And when we got to the places, it went straight to the heart of it. There wasn’t any of that fluffiness. It went ‘boom’ and landed really well. (Whārangi, RAP3, 2019)

In the few instances where there wasn’t dialogue between the teachers and the educators who would be involved in the visit, or planning meetings were held separately with each provider, aspects of the learning sequence felt “out-of-sync”. This was characterised by an absence of mutual vocabulary and understanding, and in those cases the research mentors became a default source of information.

While the teachers setting the direction of travel was essential, planning was very much a two-way process. At the first meeting, the teacher typically shared their initial ideas for the overarching question or big idea, explaining its position within a broader learning cycle; for example, within a year-long or term’s inquiry focus. Educators commented on the benefits of this discussion and in particular on being given detailed information about what ākonga had been learning before the visit. One educator commented, for example, that this had made “a huge difference for us. Normally we spend a lot of time trying to gauge that as the session begins, what they know. This time we had a common reference point.” The groups discussed the overarching question in depth, teasing out its strength, clarity, and relevance. Through this process, the question was often adapted or refined, or sub-inquiry questions established that were specific to each site. Key concepts were also identified and discussed, with teacher and educator understanding often enriched and expanded through the sharing of different perspectives. The teams then worked together to explore potential points of connection between the learning focus and site offerings (e.g., features, exhibits, or spaces).

Pre-planning sessions also provided an opportunity for the teacher to talk to the educators about their learners; for example, how they learn best, what is important to them, and, in some cases, relationship dynamics within the group. This supported educators to make meaningful connections to the learners’ lives, explore emotional responses ākonga might have to the site, and consider how these could be an impetus for rich inquiry and critical thinking. There was some teacher frustration when the intent of this discussion was not reflected in the site visits; for example, when the visit content was pitched at the wrong level or the activities relied too heavily on educators delivering content to the ākonga.

Responsive communication about evolving learning designs

A key characteristic of the learning inquiries was that the trajectories changed and often evolved rapidly in the lead up to a visit. Clear and timely communication between teachers and educators therefore played a key role in maintaining the coherence of the visits and their alignment to the overarching question or idea that ākonga were exploring. A great deal of ground could shift in the time between the planning meetings and visit. In some cases this was positive; for example, it gave educators time to draw upon other forms of support: expert colleagues such as specialist curators, bicultural advisers, or external partners who could provide insight or content to enhance the learning experience. However, personnel changes in educators during or between planning and delivery phases negatively impacted on visits, diminishing the extent to which the teachers felt able to authentically engage. In these situations, teachers compensated for this gap during or after visit sessions to maintain relevance and ākonga connection to the overarching question or capabilities. The few days or week before the visit was a critical period for consolidating visit planning, and it was vital that teachers and educators maintained close communication to check for alignment or slippage in the learning intentions and to ensure the ākonga interests and questions could be picked up in the visit. Under some circumstances, an evolving approach to the overarching question affected the confidence of the educators. Without supportive dialogue, this impaired the relationship between teachers and educators, in some cases leading to overthinking, or under-delivery during a visit as the planning intent evaporated.

Google documents were a useful way to capture shifts in thinking, share the prior learning and interests of ākonga, and provide feedback or suggestions on planned activities or questions. They supported a more responsive process, with educators and teachers using them to check their understanding, test out their ideas, and gain insight into each other’s practice or into the learning experiences of ākonga. Not all educators felt that this iterative process would be a workable option in everyday practice, due to time constraints and large volumes of schools they routinely worked with. However, the richness of the information was valued. One educator commented that, in regular practice, teachers completing the “prior learning” and “what do you hope ākonga will get out of the visit” sections of upcoming trip forms often respond with a single word or leave the sections blank altogether, leaving the educator with little or nothing to build on.

Educators also commented that being aware of what was happening when other visits were also contributing to the same learning enabled them to build in points of connection/reference to other sites within their programmes. The sharing of fixed planning tools, such as meeting notes, session, or lesson plans, and visit run sheets, in many cases supported dialogue and understandings between educators at different sites, as well as with the teachers, as in this instance:

Educator: I got to see your (other provider) lesson plan—that was really helpful as a model.

Teacher: It was impressive, you actually heard us! I’ve done that before and what we’ve ended up with wasn’t what we expected. You listened and heard us and tailored the big themes to meet our needs.

Educator at the other site: Well that’s what we wanted.

Teacher: But often stuff gets lost in translation, or diluted, or you end up with something unrelated. We’ve had that happen, so be encouraged! (Whārangi, RAP3, 2019)

Actively negotiating roles, building and maintaining relational trust

Planning discussions fostered a sense of partnership and mutual purpose in ways that recognised and valued different practitioner worldviews and personalities, and complementary skills and expertise. Teachers and educators often held preconceived ideas about the roles they would play during the visit, usually unstated and mostly borne out of respect for each other’s spaces and professional practice. A consistent theme in post-visit RAP group reflections was recognition that teachers and educators rarely discuss their respective roles prior to visits and that there could be scope for a more collaborative co-teaching approach. During the visit, teachers tended to hand over the responsibility for the learning to the educators, often participating solely as observers, or only engaging with ākonga during small-group or individual activities. Anna noted that “There were instances where I was tempted to jump in, but this was not something we had discussed so I didn’t.” However, educators tended to welcome teachers contributing questions or comments at strategic points.

The possibility of co-teaching was discussed in some RAP planning meetings, but there were mixed views about this, including one teacher and educator rejecting the idea. Where some form of collaboration was agreed to, it was generally that teachers would step in with question prompts, expand upon the content when needed, and work with ākonga to amplify their voice through the process. One educator noted that they highly valued these forms of teacher engagement and at the same time found the dynamic exhausting. When it was professionally inappropriate for an educator to challenge the values and priorities of the institution they represented, teachers had greater freedom to seed that thinking for ākonga through the questions they posed.

Relational trust between teachers and educators was central to learning outcomes. In the least impactful visit experiences, either the teacher or educator felt let down by the other. In these instances, a great deal of effort had gone into preparing ākonga for the visit or developing a visit programme. When this professional generosity was not matched by the other party, feelings of disappointment ensued. These were expressed to the research mentor and not each other.

Involving students as partners in the learning arc

Teachers typically acted as a conduit between their ākonga and educators by summarising and sharing learning needs, interests, and questions. Teachers who adopted a guided or student-led approach to learning inquiries elevated ākonga as partners in shaping the learning trajectory as the dialogue between teachers and ākonga grew across the inquiry. Examples included ākonga helping to choose visit destinations and ākonga questions being emailed to educators prior to the visit. Ākonga at Akeake School held the clear expectation that educators were there to meet their learning needs and answer their questions. This added an additional voice and dynamic to the planning process.

Some educators were nervous about or not equipped to adapt their programming to meet the challenge of recognising ākonga as partners in the process. The impact of this was a misalignment between the expectations of the teacher, their ākonga, and the educators, and in particular a muffling rather than amplification of student voice. For example, educators at one site had access to questions and interests that ākonga had shared prior to the visit. These questions were significantly richer than those addressed during the visit and one of the educators was surprised about how much ākonga already knew. An educator from another site visited this same group of students before a planned visit (as part of their ordinary practice) to build relationships and discover ākonga interests. Although the site visit did not go ahead, it was clear that the educator was well prepared to meet the depth of their inquiries.

Teachers and educators contributing to each other’s professional growth

Within the RAP groups, teachers and educators were hesitant about providing feedback about each other’s practice, particularly when the visit or the ways ākonga had been set up for the visit did not meet expectations. Feedback loops between educators and teachers that contribute to practice improvement are scarce, and this hampers effective reflection and professional development. For most educators, what happened in the classroom before, during, and after visits was largely invisible. The impact of their teaching, or the students’ visit to their site and the contribution it made to students’ conception of the overarching question, understanding of issues, and/or journey towards social action remained opaque. Feeling out of the loop was a common experience and a source of some frustration.

Major implications

This research considered how ākonga relationships with people and places within and beyond their community could hold meaning for their concerns and support their contribution to conversations about their futures. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the most comprehensive internationally and holds the closest approximation to practice in the way that has engaged teachers, educators, and ākonga over time and across a wide repertoire of learning arcs and visit sites. The relatively few learning arcs where visits had an enduring effect on learning outcomes—even with high levels of practitioner effort and expertise—suggests that elevating education outside the classroom to a focus on pressing societal issues and active citizenship is challenging indeed. Nevertheless, the project illuminated rich possibilities for enhancing learning arcs to achieve these aims, particularly if the key findings discussed above are implemented in concert.

This study holds four main and interconnected implications for enabling ākonga to explore future-focused issues and contribute to change through education outside the classroom.

- The course of learner inquiries will inevitably evolve, but a sharply focused “golden thread” is needed through the visit experience. A tripartite relationship between ākonga, teachers, and educators is highly effective in supporting learner inquiries, but it is particularly important that teachers and ākonga hold the intent and vision for the learning arc and the visits within it. An overarching question, conceptual focus, or provocation—that is owned by the teacher and ākonga and tested by all parties—provides an essential anchor for the visit experience(s). It enables ākonga to make “horizontal” (across the learning arc) and elevated “vertical” (to issues and action) learning connections. Visit outcomes were negligible when teachers had insufficiently conceptualised the role and intentions of the visit and showed limited engagement with the unfolding learning in relation to the overarching question during the visit.

- The role of the educator is sophisticated and requires more structural support. An emphasis on local curriculum and inquiry-led approaches in schools means that educator planning requires increasingly higher levels of adaptability and flexibility. “Off-the-peg” programmes were insufficient to meet the needs and expectations of ākonga involved in this project. However, educators are typically accountable to the number of ākonga their programmes involve, and this student volume-focused model does not lend itself to the rich, relational planning that can encompass evolving teacher or ākonga ideas. Time and resources are needed to support educator responsiveness, flexible planning, and professional growth. There was clear evidence that educators wanted more opportunities to enhance their practice. In particular, while all the visits held interest for ākonga, greater skills and confidence among educators (specifically in relation to using learning intentions, ākonga-centred questioning, targeted use of visit spaces, and noticing learning outcomes during the visit) could enhance visit coherence and alignment to overarching learning focuses. Routine opportunities for educators to observe each other’s practice and act as critical friends could also further support educator pedagogies.

- Effective collaboration between teachers and educators is vital. Evidence from this study suggests that teachers’ communication with educators needs to go well beyond the typical few words or lines in a provider booking form. Planning meetings and shared planning documents were important mechanisms for ensuring the coherence of the learning arc; time spent or not spent in discussion impacted on the learning outcomes. Relational trust was also important and this study suggests that further exploration of co-teaching models and methods for teachers and educators to “close the loop” by providing feedback to each other are important: especially when this illuminates the impact and effectiveness of a visit in the learning arc.

- Ākonga enfranchisement matters. Fostering belonging was foundational to effective visits and was enhanced when teachers included ākonga as active partners in the learning process and educators worked to value prior knowledge: firmly establishing the relevance of the visit, and creating trust with ākonga by acknowledging their mana and weaving their voices into the learning. Fuelling their sense of agency was even more important. Some educators and teachers created a learning arc where ākonga emerged from visit experiences feeling galvanised, empowered, and equipped to address issues that mattered to them. Visit experiences in these learning arcs offered ākonga opportunities to critically reflect on what was being presented to them, enabled them to understand how the visit site contributes to societal change, and demonstrated how they can be changemakers. However, in less effective learning arcs, this potential was either not realised, or partially realised, and ākonga returned to their classrooms with their kete full of information, but a paucity of tools for future use. Teachers taking a curriculum immersion approach, and educators carving out opportunities for future-focused consideration and citizenship capability building during a visit are key. Enabling ākonga to critically reflect upon the personal and societal significance of their visit and how they might draw from the experience to influence their lifeworld is also crucial.

Conclusion

The capacity for learning experiences outside the classroom to be powerful, memorable engines of social change for Aotearoa’s ākonga is immense. This study has identified mechanisms that contribute to effective learning arcs that fulfil this aim and dissolve the boundaries between classrooms and visit sites. It has revealed the importance of ākonga enfranchisement and the effectiveness of an immersion approach to incorporating experiences outside the classroom into impactful learning arcs. There is a need for further research to consider how inquiry-led engagement with visit sites can be related to wider societal debates, and how ākonga can be supported to notice the perspective(s) shared at each site, and to use their voice within, or as a result of, a visit. Future investigation of the transitions between classrooms, visit sites, and back again for teachers, educators, and ākonga holds potential. The findings from this study suggest that moving away from an “off-the-peg”, student volume-focused model to one that facilitates teacher, educator, and ākonga participation in a rich, collaborative approach to visit planning, programme delivery, and feedback, anchored to an overarching question, conceptual focus, or provocation, is vital. Additionally, there remains a need to further prioritise the connection to pressing issues, noticed and felt keenly by many ākonga in this study, and opportunities for contributing to change through the extraordinary range of learning experiences and resources that exist outside the classroom, in Aotearoa.

References

Bolstad, R. (2011). Taking a “future focus” in education—what does it mean? An NZCER working paper from the Future-Focussed Issues in Education (FFI) project. New Zealand Council for Educational Research. http://www.nzcer.org.nz/research/publications/ taking-future-focus-education-what-does-it-mean

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi. org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Bruce, C. D., Flynn, T., & Stagg-Peterson, S. (2011). Examining what we mean by collaboration in collaborative action research: A cross-case analysis. Educational Action Research, 19(4), 433–452. https://doi.org/10.1080/09650792.2011.625667

Carr, W., & Kemmis, S. (1986). Becoming critical: Education, knowledge and action research. Deakin University Press.

Charitonos, K., Blake, C., Scanlon, E., & Jones, A. (2012, May 22–25). Trajectories of learning across museums and classrooms. Paper presented at the Transformative Museum Conference, Roskilde, Denmark. http://oro.open.ac.uk/33400/

Eames, C., & Aguayo, C. (2020). Education outside the classroom: Reinforcing learning from the visit using mixed reality. Set: Research Information for Teachers, (2), 31–37. https://doi.org/10.18296/set.0173

Eames, C., Law, B., Barker, M., Iles, H., McKenzie, J., Patterson, R., Williams, P., & Wilson-Hill, F. (2006). Investigating teachers’ pedagogical approaches in environmental education that promote students’ action competence. Final report. Teaching and Learning Research Initiative. http://www.tlri.org.nz/tlri-research/research-completed/school-sector/investigatingteachers%E2%80%99-pedagogical-approaches

Harcourt, M., Milligan, A., & Wood, B. (2016). Teaching social studies for critical, active citizenship in Aotearoa New Zealand. NZCER Press.

Hill, A., North, C., Cosgriff, M., Irwin, D., Boyes, M., & Watson, S. (2020). Education outside the classroom in Aotearoa New Zealand—A comprehensive national study: Final report. Ara Institute of Canterbury.

Hipkins, R. (2017). Weaving a coherent curriculum: How the idea of ‘capabilities’ can help. New Zealand Council for Educational Research. https://www.nzcer.org.nz/system/files/Weaving%20a%20coherent%20curriculum_0.pdf

Hipkins, R. (2019). Weaving a local curriculum from a visionary framework document. European Journal of Curriculum Studies, 5(1), 742–752.

Locke, T., Alcorn, N., & O’Neill, J. (2013). Ethical issues in collaborative action research. Educational Action Research, 21(1), 107–123. https://doi.org/10.1080/09650792.2013.763448

Milligan, A., Hunter, P., & Harcourt, M. (2016). Issues-based social inquiry in social studies and citizenship education. In M. Harcourt, A. Milligan, & B. Wood (Eds.), Teaching social studies for critical, active citizenship in Aotearoa New Zealand (pp. 40–63). NZCER Press.

Milligan, A., & Rusholme, S. (2016). Making the most of citizenship learning across cultural institutions. Set: Research Information for Teachers, (3), 36–44. https://doi.org/10.18296/set.0055

Ministry for Culture and Heritage. (2016). Pedagogical framework for the education programme at Pukeahu National War Memorial Park. https://mch.govt.nz/education/pedagogical-framework-education-programme-pukeahu

Ministry of Education. (2007). The New Zealand curriculum. Learning Media.

Ministry of Education. (2016). EOTC guidelines 2016: Bringing the curriculum alive. https://eotc.tki.org.nz/EOTC-home/EOTCGuidelines#guidelines

Ministry of Education. (2021, December 20). Enriching local curriculum. https://eotc.tki.org.nz/ELC-home

Moreland, J., McGee, C., Jones, A., Milne, L., Donaghy, A., & Miller, T. (2006). Effectiveness of programmes for curriculum based learning experiences outside the classroom: A summary. Centre for Science and Technology Education Research and the Wilf Malcolm Institute of Educational Research, University of Waikato.

Papprill, J. (2016). Active citizenship for a sustainable future: Beyond school learning. Set: Research Information for Teachers, (3), 51–56. https://doi.org/10.18296/set.0057

Sinnema, C., Sewell, A., & Milligan, A. (2011). Evidence-informed collaborative inquiry for improving teaching and learning. Asia– Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 39(3), 247–261.

Stake, R. (2006). Multiple case study analysis. Guilford Press.

Westheimer, J. (2010). What kind of citizen? Democratic dialogues in education. Education Canada, 48(3), 6–10. https://www.edcan. ca/articles/what-kind-of-citizen-democratic-dialogues-in-education/

Williams, P. (2012). Educating for sustainability in New Zealand: Success through Enviroschools. In M. Robertson (Ed.), Schooling for sustainable development: A focus on Australia, New Zealand, and the Oceanic Region (pp. 33–48). Springer.

APPENDIX A

Capabilities for responding to future-focused issues and contributing to change

| Capability | Could be expressed as being able to: |

|---|---|

| Make meaning through disciplinary concepts |

|

| Use emotions as a productive force for change |

|

| Navigate perspectives and representations |

|

| Contribute as citizens |

|

Research team

Te Herenga Waka—Victoria University of Wellington investigators

Andrea Milligan, Sarah Rusholme (based at Experience Wellington), Lee Davidson, Frank Wilson, Kate Potter

Research team members from:

Corinna School, Newtown School, Berhampore School, Wellington East Girls’ College

Dowse Art Museum, City Gallery Wellington Te Whare Toi, Zealandia Te Māra a Tāne, New Zealand Police Museum, Wellington Museum Te Waka Huia o Ngā Taonga Tuku Iho, Pukeahu National War Memorial Park, National Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, Wellington Zoo, Capital E Nōku te Ao, New Zealand Parliament.

Research assistants

Kathleen Murrow, Sola Freeman