Introduction

In this project, the research team—a collaboration between teacher researchers and university researchers— was interested in finding out about how children as teachers might engage their families as learners at a museum. This project had two parts. First, it was about young children as museum guides, explaining their understandings about a museum exhibit or object to others. Second, the research explored the ways in which shared experiences with families and friends visiting a museum invited conversations that include families’ social and cultural knowledge, and engaged families in their children’s learning. The research also explored what objects or exhibits and accompanying stories captured the children’s interests and how competently and efficiently they could explain their interpretations to others.

As an outcome, the project also focused on developing and trialling a resource for early childhood centres about making the most from a museum visit. The project involved two early childhood settings: Tai Tamariki Kindergarten and Owhiro Bay Kindergarten, both in Wellington. This resource is in draft form, and we anticipate that it will become available on the Teaching and Learning Research Initiative (TLRI), University of Waikato Wilf Malcolm Institute of Educational Research (WMIER) early years Research Centre and the Ministry of Education ECE Lead websites during 2014.

Research questions

The three research questions for the project were:

- How might children as teachers engage their families in learning at a museum?

- How do families as learners respond to children’s story-telling and explanation?

- What implications do the findings from the first two questions have for museum education in early childhood centres and schools?

Relevance of these questions to learning and teaching in Aotearoa New Zealand

These questions are relevant to learning and teaching in Aotearoa New Zealand in three domains: children having some authority in relation to museum visits, museums as learning spaces, and the role of dialogue with others in meaning-making.

Children having some authority in relation to museum visits: Katrina Weier (2004), in a study of under-5s as docents, completed as a master’s thesis inside a wider study of children in museums (Piscitelli, Weier, & Everret, 2003), explored the benefits for both children and family visitors. She comments that “Research suggests that children demonstrate higher levels of motivation when they have choice and control over their encounters in museums” (p. 107). In her study, children were “empowered” by the experience of being museum guides as they made choices about where to go and what to see, while also increasing their confidence in giving explanations about objects. The visitors being guided by the children were impressed with the children’s abilities to lead, explain, and offer ideas and opinions, and many of the visitors enjoyed “seeing the museum through the child’s eyes” (p. 108). Other studies cited by Weier of children acting as museum guides are of primary or secondary school children. This practice, with young children, had not been researched before in New Zealand.

Museums as learning spaces: Museums are storehouses of national treasures and artefacts. Aotearoa New Zealand has an abundance of museums in both large cities and small towns. In many instances these museums house collections that tell stories of the cultural and social history of a people, a country, a region, or simply a town or village. They also provide a unique connection with Māori, Pacific Island, and other cultural histories, practices, and knowledges in Aotearoa New Zealand. Having an opportunity to visit a local or national museum can help our understanding of ourselves and of others. The benefits of children having experiences with authentic artefacts and resources, such as are available through museums and art galleries, have been emphasised in Australian research (Anderson, Piscitelli, Weier, Everett, & Tayler, 2002; Everett & Piscitelli, 2006; Piscitelli & Anderson, 2001). These and other studies (e.g., Eberbach & Crowley 2009; Wolf & Wood 2012) have provided evidence that museum visits—and visits to other sites in the community that house cultural and historical collections—can provide rich opportunities for learning in the early years. This learning includes the acquisition of knowledge as well as dispositions for learning that include a love of museums.

The role of dialogue in meaning-making: dialogue and conversations between children and children, and between children and adults, is central to effective learning. Research about children’s meaning-making in mathematics in a primary school classroom (Gresalfi, 2009) emphasised the value of opportunities for learners to exercise authority in the meaning-making process. Gresalfi argued that the context of this meaning-making includes being “expected, obligated and entitled to explain” (p. 363). She adds that “collaborative practices are simultaneously important to productive dispositions, conceptual understanding, and preparation for future learning” (p. 363). In Aotearoa New Zealand, being “expected, obligated and entitled to explain” provides a very specific aspect of both the communication strand in Te Whāriki (Goal 2: verbal communication skills for a range of purposes) and the New Zealand Curriculum (the key competency: Using language, symbols and texts). Research in the “learning sciences” literature has indicated the value for longer term learning of learners developing competence in dialogue with others, especially teachers (Mercer, 2002; Mercer & Littleton, 2007). Kevin Crowley and Maureen Callanan (1998, p. 13), in a paper describing their research on parents supporting their children’s scientific thinking in a museum, comment that “when children explain their learning to other children or to adults, they remember their discoveries better and are also more likely to transfer the new knowledge to subsequent problem solving.” Research at The Children’s Museum of Indianapolis (Wolf & Wood, 2012) highlights the importance of adults providing support and scaffolding to maximise learning for children; early work by Haas (1997) had also concluded that supportive interactions and appropriate open-ended questions from adults are necessary for effective learning in a museum. Furthermore, recent work with museum educators (Dysthe, Bernhardt, & Esbjørn, 2013) concluded that dialogue between teachers and students encouraged curiosity, meaning-making, and creativity. This project builds on an earlier TLRI project (Carr, Clarkin-Phillips, Beer, Thomas, & Waitai, 2012) on learning in museums in an Aotearoa New Zealand context, which emphasised the value of dialogue around boundary objects: resources or objects that could belong in both the early childhood centre and the museum (e.g., the children’s sketchbooks and photographs of the exhibits).

Methodology and analysis

This was an action research project in which university researchers worked in partnership with teachers, children, and families. Kemmis and McTaggart (2000, p. 595) suggest that one of the criteria of success in action research is whether participants have developed a stronger and more authentic understanding and development of their practices. We include the children as participants here to emphasise the notion that children themselves can develop a stronger and more authentic understanding of their own meaning-making practices through action research that seeks their views. Practitioner inquiry also has a capacity to construct theory and to contribute to our understanding of knowing and learning in a more general way. Cochran-Smith and Donnell (2006, p. 508) assert that “practitioners are among those who have the authority to construct Knowledge (with a capital K) about teaching and learning.” This methodology combines theory and praxis, keeps the complexity of the centre or classroom context available, and distributes the ownership of the research. Action research “deals with real-life problems in context, and it is built on participation by the non-university problem owners. It creates mutual learning opportunities for researchers and participants, it produces tangible results” (Greenwood & Levin, 2008, p. 81).

A sociocultural theoretical approach was adopted for this study of “real-life problems in context”. The focus of investigation during museum visits was how boundary objects and dialogue worked together (Carr et al., 2012; Mercer & Littleton, 2007; Star & Griesemer, 1989; Tsui & Law, 2007). Boundary objects were the protocols, artefacts, scripts, prior knowledges, dispositions, literacy objects, and people that crossed the borders between kindergarten, museum, and home. These “objects” enabled dialogue and meaning making in responsive and reciprocal ways.

Data were collected from audio-recorded interviews and discussions with teachers and parents, teachers’ audio-recording of children’s conversations, documentation by teachers of children’s learning and their own practice and learning, parents’ written reflections and audio-recordings of visits to the museum with their children, photographs, and children’s artwork and design sketches. A resource was designed in collaboration with teachers and children at Tai Tamariki and then trialled with teachers, children, and parents at another kindergarten in Wellington. The final resource is a result of the feedback from teachers, children, and families at both early childhood settings.

Key findings in relation to research questions

Research Questions One and Two: How might children as teachers engage their families in learning at a museum? and how do families as learners respond to children’s story-telling and explanation?

Data gathered for Research Questions One and Two included observations and recorded conversations. during the project, the children’s visits to exhibitions included Kahu Ora: Living Cloaks, European Masters: 19th–20th Century Art from the Städel Museum (an exhibition of paintings), and Brian Brake, 1927–88: Lens on the World (an exhibition of photographs). The research findings are summarised as four aspects of children as teachers: (a) children recognising, respecting, and reminding others of museum protocols; (b) children as exhibitors and gallery designers, recognising and demonstrating messages in a variety of modes; (c) children developing an appreciation of craft; and (d) children calling on prior knowledge to make meaning and enable explanations.

(a) Children recognising, respecting, and reminding others of museum protocols

Throughout the project children had the opportunity to visit an exhibition more than once. Sometimes the subsequent visits were with a different group of children and teachers so children were able to teach the others about the exhibition. A number of examples of children being teachers and sharing their knowledge and ideas with others emerged during the project. Often this teaching was about the rules and protocols of museum visiting, as children became very adept at looking for visual cues that indicated what was permitted, such as “no camera” signs.

We had initially proposed that children at Tai Tamariki would choose their favourite artefact or collection and construct their own resource that would deepen their expertise, interest their families, and act as prior knowledge and prompts for engaging their families on a museum visit. This proposal was taken up as collaboration between the curator of a museum exhibition and the children. The exhibition of Kahu Ora: Living Cloaks captured the children’s interest and, with some encouragement and input from teachers, children began designing and constructing their own kākahu (cloaks). The curator visited the children’s work at the kindergarten and created an opportunity for their kākahu to be displayed in the main Kahu Ora exhibition at Te Papa Tongarewa.

The exhibiting of the children’s kākahu in the main museum provided an impetus for families to visit the museum with their children, and another opportunity for the children to act as teachers. The children were keen to show their families and other children their exhibited work and offered to be guides for others. A number of the relatives travelled significant distances to come and see the children’s kākahu.

Examples include the following:

- The children demonstrated familiarity with museum protocol (and, in the case of the Kahu Ora exhibition, with tikanga Māori). Children became docents for families and friends. In one incident, a child-as-teacher (Child J) said that the visiting group could not leave until they had “given their thoughts to the ones that have passed on”. She explained [pointing to photos an opposite wall]:

These are the people that are still around and these are the people that have passed away. They are the weavers and all have their own korowai, see! You come over and say a karakia to let them know you are thinking of them, but I can’t do the kai one [referring to a specific karakia].

Child J had been to the exhibition previously with Teacher G, who had talked about the photos of the weavers and the protocols associated with honouring them.

This child-as-teacher had been able to make the distinction between types of karakia. She would have been very familiar with the karakia kai (blessing for food) as this blessing was recited every lunchtime at the kindergarten but realised that this was not an appropriate blessing for honouring ancestors. After this visit, Teacher G gifted to the teachers and children an appropriate karakia to be used when entering the exhibition.

When another child-as-teacher was planning to take members of his family to see the children’s korowai at the exhibition, he asked the teacher to write down the karakia, as he was worried he might not remember it for his granddad.

- Child C took seven adults on one visit and two adults on another. He led the way and told his family members that they needed to “stay close and follow me, I’m the leader”. Before entering the exhibition Child C led his relatives in the karakia and then talked to them about the weavers in the photos, pointing out one who was a friend of one of the teachers at kindergarten, “These are the ones that are dead and these are the ones that are alive and that one is G’s friend.” He also talked about how the korowai were made (“that one is made out of dog hair or something and that one is made out of this flax”) and who had helped make the “Let’s celebrate” cloak.

As they were leaving he insisted that everyone sprinkle themselves with water, despite reluctance from some family members, asserting, “if you’re not going to do what you’re meant to do when you come to Te Papa then you can stay there.”

- Child M took her parents and siblings to the Kahu Ora exhibition, and the parents provided feedback to Teacher B. Following this discussion, Teacher B wrote up the following reflection for Child M’s portfolio:

[Your] Mum, dad and I have talked about how you loved being the leader as you showed them around Kahu Ora; you told me you were the leader, you showed them what to do. This is really valuable knowledge to share, M, and you have shown us lots of different ways that you can be a leader throughout this process. I look forward to seeing what other information you might like to share once your kākahu is displayed and you have been a part of that process. There are lots of things about exhibiting and looking after taonga (treasured artefacts) that we will all learn together. I also love that part of your understandings of what to do in an exhibition incorporates strong concepts of Te Ao Māori. You talk a lot about sprinkling the water on your head and talking to the weavers in the picture (Teacher G taught you a karakia to give thanks to our ancestors for our treasures). I know that this is also a very important part of your family life and Mum and dad are very proud of your understandings.

(b) Children as exhibitors and gallery designers: recognising and demonstrating messages in a variety of modes

Examples include the following:

-

- After a visit to a photography exhibition (Brian Brake, 1927–88: Lens on the World) the children made their own photography exhibition at the kindergarten. Children took photos of people and objects around the kindergarten that captured their interest, and the teachers helped them frame, mount, and display these on a moveable foldaway screen. A label was written for each photograph.

- When children had the opportunity to contribute to an exhibition at a museum, as they did here during the Kahu Ora exhibition, the curator afforded the exhibiting process the same respect as any official exhibit, including the opportunity for the children to dictate the label to go on the wall beside the artefact.

Here is an example of a label for the museum, dictated, with some assistance, by the children:

| Let’s celebrate

Celebration korowai 2012 Made by: A,D, J, and U (all aged 4) and M (aged 3) Velvet and lining fabric strips, knitted mesh fabric base. On loan from Tai Tamariki Kindergarten. Our korowai (tasselled cloak) is special because it is made from fabric which is all different. We made it for birthdays and last days at Tai Tamariki. We made two—this one and a little one, because it would be sad if our babies couldn’t wear korowai. We chose this fabric because it is so soft and we are good at tying knots. It looks a little like the muka (flax fibre) that the weavers showed us how to make in “Kahu Ora”. They let us take harakeke (flax) back to the kindergarten. |

Let’s celebrate exhibited at Te Papa

- The yellow line. On one occasion, soon after the children’s photography exhibition had been constructed, a very young child crawled up to the screen and began to rip the photos from the wall. The teacher started to explain to Child d (an exhibiting child) that the toddler didn’t understand that it wasn’t appropriate to pull the photos off the wall.

Child D then exclaimed “Well how could she know, Becs [the teacher], there is no yellow line!” Child d then asked for some tape to construct a line around the exhibition to provide a barrier. Later he stood in front of a group of children and explained what the line meant. he emphasised that people needed to stand behind the line to keep the work safe. After that lesson, there were no more incidents of children touching the photographs.

Child constructing a ‘yellow line’ in front of children’s photo exhibition at the kindergarten.

- The yellow line (and “too louder voices”):

Another huge interest was patrolling the yellow lines on the floor that were used as a visual barrier in front of the paintings. Many a visitor was asked not to step over the yellow line and tamariki were also quick to talk about ‘too louder’ voices and what they felt were the expectations of being in the art gallery. (Teacher documentation)

- When a group of children decided they wanted to make their own art gallery at the kindergarten they were able to tell the teachers what they would need to make the gallery and why.

The gallery needed to be white because, according to Child K, “they [artists and exhibitors] want it (the artwork) to look differenter.” The following are examples of the children’s suggestions for creating a gallery.

Child Y: On the instructions it says Gallery door—we need that.

Child O: We can make a sign like at the gallery to remind people about respecting the art— especially the little children.

This child made a sign: “No touching because it’s special”.

Child B made two signs, one saying: “No guns, no cars, no running, no skipping in the gallery please” (“it always says please”, he remarked) and another saying “No photographs”.

- Child M, whose kākahu was exhibited first, took some other children to see her kākahu. Teacher N wrote about this experience for inclusion in M’s portfolio:

You requested to be a guide so your friends could see your korowai in Kahu Ora. You led us into the exhibition and showed us where your korowai was on display. What an amazing experience seeing one of our tamariki talk about her own work on display in our national museum, complete with an information card next to your work. L [Te Papa staff member] asked some great questions about how you made the korowai, as did your friends, who listened closely as you explained the materials you used, and what inspired your beautiful creation. Like all our tamariki, your ideas and work are taonga for us in our kindergarten community and now for people who visit Te Papa from all over the world.

This child, when asked what she would like to teach the people that came to see her cloak, replied: “… [tell them] about no touching. About when we put the water on our head when we go.” She also asked Teacher B to write “slow walking” as an instruction and then set to work making a sign.

(c) Children appreciating a craft

When an exhibition included demonstrations of a process, as it did in the Kahu Ora exhibition, where the children also met the weavers, children could begin to appreciate and understand a mode of craft (in this case, weaving as an art). This enabled the children to become entitled to explain the process to others.

Examples:

- After the visit where the weaver had shown them how to strip the flax leaf with a shell to expose the fibre, Child C, on returning to the kindergarten with some flax given to him by the weaver, asked for a shell. he set to work running the sharp edge of the shell along the harakeke to reveal the muka—the silky strands of fibre in the harakeke,— indicating how closely he had watched the weavers in the exhibition. Later in the afternoon Child C and Child A explained clearly to a group of other children and teachers the process of stripping the flax in this way. They also showed how the weavers roll the fibre on their legs to “tighten it so they can then make the cloak.”.

- A teacher comment after her first visit to the Kahu Ora exhibition with a group of children:

-

-

This was my first time visiting the Kahu Ora exhibition with a group of children. The very first thing that caught my attention was the knowledge of the children. They had so much knowledge about, not only the exhibition, but more in- depth knowledge about the materials and methods behind making korowai. The children also had a lot of knowledge about the exhibition; they recognised exhibition pieces, the different materials that pieces were made from, and their own favourite pieces.

(d) Children calling on prior knowledge to make meaning and enable explanations

Prior experience in the early childhood centre enabled children to explain a sequence of events leading up to a completed artefact and to make connections.

- When a group of children were looking at a painting entitled Eruption of Vesuvius by Johan Christian dahl, Child K shared her knowledge of the destruction of Pompeii from an exhibition that she had visited some months earlier. She commented:

You know it’s that volcano when lava comes out and burns people and the dogs … [the volcano] … that spurts things out and made the whole city fall down.

- Child J took four adults to the exhibition. her mother wrote about the visit:

J showed us her favourite cloak, the piupiu one, “it looks like a skirt,” she explained. Then J showed us a cloak made from kiwi feathers, “This korowai is made from kiwi feathers and kakapo feathers.” She then showed us another and told us, “This one is made from lots and lots of bird feathers like kereru. Kereru is almost extinct” and “This one is made from eight dogs. it’s the dog fur that’s used,” she explained. As we left the exhibition J said we have to sprinkle the water on our heads and she described how the children wear their korowai at kindergarten on their birthdays or last day “because it’s a special time”.

Developing a resource

Towards the end of the project we drew on the research data to develop a draft resource as a guide for teachers and families visiting museums. This resource was designed to enable a museum visit to be a valuable learning experience for children and to provide opportunities for dialogue between adults and children. The resource includes conversational prompts for teachers and families. We trialled this resource in a second early childhood centre not located in a museum.

After the construction of the draft resource, two teachers and a small group of children (four) from another early childhood centre participated in trialling the usefulness of the resource. The teachers chose an exhibit at Te Papa Tongarewa (the colossal squid) as the focus of their visit. This choice was based on an ongoing interest by a number of children in their early childhood centre in large creatures. After their visit to the museum and their use of the resource, we interviewed the teachers to get feedback in order to refine and modify the final product. The children returned to Te Papa at a later date with family members and acted as guides. We interviewed parents and children about these subsequent visits. Some parents documented the visit, recalling comments and conversations, while other parents videoed parts of the visit.

Findings from this phase of the research included (i) the value of using a book of photos of favourite artefacts as a prompt for both families and children; (ii) children who are unfamiliar with a museum are likely, in the first instance, to be interested in aspects of the physical environment that surrounds an exhibition, rather than the exhibition itself.

- The value of using a book of photos of favourite artefacts as a prompt for both families and children.

Example (a parent response):

This morning E [2 years 8 months] went back to Te Papa to show me and her cousin O what [the teachers] had shown her at Te Papa last week. Since the trip to Te Papa she had been telling us about the shark and how she wasn’t scared and how she got to wear sunglasses. This seemed to be the highlight. Today she was excited to go back and see the squid, although she kept saying ”I go see the eel,’ ‘you can’t touch the eel, Mummy.” Then she would correct herself and say, ‘is it a squid?’

She loved her own book [of photos of favourite artefacts] and proudly held it. Before we arrived at Te Papa we parked the car by her Opa’s work. She ran in and told her Opa, ‘I going Te Papa. I show O. I’m not scared. I wear glasses. I like sunglasses.’

She then said, ‘Shark going to get us. I touch the shark.’

At Te Papa she led the way. When we got to the squid I lifted her up to show her. She kept saying, ‘You can’t touch it.’

We looked at the video of the squid being moved. She asked why the people were in the water and why they were moving it.

We went to watch the 3D movie and she sat on my knee. ‘Little bit scary. I like the shark.’

When the squid ate the fish she jumped and got such a fright. She continued to watch it, sitting on my knee. The second time the squid ate the fish she got another fright. The music was quite scary and she became a little unsure and didn’t want to watch any more so we moved on.

I think the first time e must have been intrigued and braver without Mummy, but this time she wasn’t so keen. ‘I don’t like hhhooorrr’ (slurping, sucking noise like squid made when it ate the fish). ‘The fish need to eat dinner.’

I think e really enjoyed showing me and her cousin something she had prior knowledge of. (Parent 1)

- Unexpected interests, e.g., The lift/elevator and the café

Example (a parent response):

W [nearly 5 years] took T and me to Te Papa today (Tuesday) to visit the colossal squid.

He told me before we went that it has tentacles, claws, and a beak and it eats hookfish. He said that he went up in a ‘smelly’ lift to see the squid and afterwards he had a fluffy in the café with the group (he showed me exactly where later).

When we arrived at Te Papa, W showed me which doors and lift to take and pressed the buttons to get there. He guided us through the marine exhibit to the squid’s case and told me it was dead inside a box. He then showed me the ‘blog’ about the squid, the video about how they caught the squid. He used the computer to ‘design a squid’. he told me (talked us through) the ‘formalised’ squid bits—claws, beaks etc., and told us where on the squid’s body these went. He told us the story of how the squid died eating and choking on a hookfish. He went through the functions of the body parts. (Parent 2)

Implications for practice

Research Question Three: What implications do the findings from the first two questions have for museum education in early childhood centres and schools?

The following are implications for practice:

-

-

- More than one visit to the same exhibition is very helpful. Resources back at the centre (for example, exhibition catalogues and pamphlets, photographs of artefacts of particular interest) provide a reminder or prompt for children’s commentaries and explanations.

- Resources for drawing (e.g., sketchbooks) encourage children to look closely at exhibits, strengthen the impact of a visit, and add opportunities for dialogue.

- Providing children with the opportunity to become an expert in one aspect of a museum exhibition enables their role as a teacher and their development of explanation abilities. It provides them with funds of prior knowledge, spaces for making meaning.

- Documenting the exhibition visits in ways that allow their stories to be revisited by children, teachers, and families enrich the opportunities to connect families with the museum visit experience, and provide children with practice in explaining.

- Some conversational prompts are helpful. An example is asking children what they would tell others. This example might be seen as an aspect of children being “expected, obligated and entitled to explain” (Gresalfi, 2009, p. 363, see page 3 of this report).

- Opportunities for children to have some authority in relation to museum visits can include the following:

- children taking their own photographs and being expected to dictate explanations;

- a relationship with a curator; this might sometimes be possible in local museums, enabling children to exhibit their work (and/or go behind the scenes)

- children constructing an exhibition at the early childhood centre

- the same protocols or scripts (e.g., karakia) in more than one place, enabling explanations to build on these connections

- messages and signs that children might meet in the museum can be introduced in the early childhood centre.

- children engaging in sustained and complex craft projects to enable an early appreciation of craft.

- teachers writing down events in portfolios of Learning Stories and

- teachers constructing a personalised book of photos of favourite artefacts or spaces to provide prompts for conversations.

-

Summary diagram

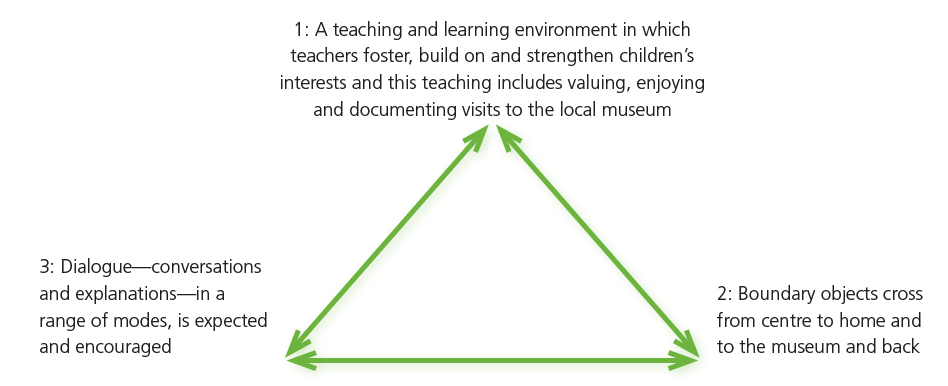

By immersing ourselves in the rich descriptive data from observations, interviews, teacher reflections, and narrative assessment of children’s learning we have identified some common elements that strengthen children’s learning in a museum and contribute to children’s capacities as teachers. These elements, conceptualised as a triad, are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Opportunities for children as teachers in a museum

Publications

This project built on an earlier TLRI project entitled: Our Place: Being Curious at Te Papa. Four papers have so far been published, with a fifth submitted, from this museum research. The abstracts are as follows:

Carr, M., Clarkin-Phillips, J., Beer, A., Thomas, R., & Waitai, M. (2012). Young children developing meaning-making practices in a museum: The role of boundary objects. Museum Management and Curatorship, 27(1), 53–66.

Abstract: A kindergarten, housed in a museum building in the centre of the capital city of New Zealand, has provided a unique opportunity for young children, teachers and university researchers to explore opportunities to learn with, and from, a museum’s artefacts and exhibitions. The authors have researched the ways in which the children constructed meaning from the displays and the knowledge offered by the museum. This article explores the children’s learning when they visited one of the special exhibitions during the first year of an action research project. We highlight their developing boundary-crossing competence and meaning-making practices and explore the role of ‘boundary objects’ in this learning. This article focuses on some of these objects and considers the way in which (associated with dialogue) they contributed to highlighting and strengthening the learning opportunities in the museum.

Clarkin-Phillips, J., Paki, V. A., Fruean, L., Armstrong, G., & Crowe, N. (2012). Exploring Te Ao Māori: The role of museums. Early Childhood Folio, 16(1), 10–14.

Abstract: Museums offer many opportunities for developing knowledge of the bicultural heritage of Aotearoa New Zealand. This article reports on research involving a kindergarten located in a national museum. It discusses children’s growing understanding of te ao Māori (the world of Ma¯ori) through their regular visits to the collections and exhibits in the museum and suggests teachers in early childhood centres may find connecting with their local museum a valuable resource for enhancing bicultural practice.

Clarkin-Phillips, J., Carr, M., Thomas, R., Waitai, M., & Lowe, J. (2013). Stay behind the yellow line: Young children constructing knowledge from an art exhibition. Curator: The Museum Journal, 56(4), 407–420.

Abstract: Studies exploring very young children visiting museums and art galleries are few. The majority of research about museum and gallery visitors explores family group interactions. This paper examines the findings of a study involving three- and four-year-old children visiting an art exhibition in a national museum on more than one occasion. The children’s construction of knowledge about being a museum visitor and exhibitor indicates their ability to develop an appreciation of art and an understanding of the purposes of museums and art galleries.

Clarkin-Phillips, J., Carr, M., Thomas, R., O’Brien, C., Crowe, N., & Armstrong, G. (2014). Children as teachers in a museum: Growing their knowledge of an indigenous culture. International Journal of the Inclusive Museum, 6, 1–12.

Abstract: This research paper was developed from a presentation at the Sixth international Conference on the inclusive Museum in Copenhagen based on findings from a study of preschool (3–4 year old) children acting as museum guides for their families. The research questions for the study were: how do young children as teachers engage their families in learning in the museum and how do families as learners respond to the children’s storytelling and explanations?

The children in the study attend a kindergarten located in the national museum of Aotearoa New Zealand: Te Papa Tongarewa. during an exhibition of indigenous (Māori) woven cloaks (kākahu or korowai), the children constructed their own cloaks back at the kindergarten. The curator exhibited the children’s cloaks in the official korowai exhibition, and the children then began to act as docents for their families and the teachers. This research explored the knowledge and meaning-making acquired by the children and communicated by them to the visiting families and teachers.

The study was an action research project in which university researchers worked alongside teachers, children and families. Children’s visits were observed and their conversations were recorded; teachers and parents were interviewed. Analysis of the data has been categorised in terms of what children were learning and the children’s developing roles as teachers themselves.

References

Anderson, d., Piscitelli, B., Weier, K., Everett, M., & Tayler, C. (2002). Children’s museum experiences: Identifying powerful mediators of learning. Curator, 45, 213–231.

Carr, M., Clarkin-Phillips, J., Beer, A., Thomas, R., & Waitai, M. (2012). Young children developing meaning-making practices in a museum: The role of boundary objects. Journal of Museum Management and Curatorship, 12, 53–66.

Cochran-Smith, M., & Donnell, K. (2006). Practitioner inquiry: Blurring the boundaries of research and practice. In J. L. Green, G. Camilli, P. B. Elmore, A. Skukauskaite, & P. Grace (eds.), Handbook of complementary methods in education Research (pp. 508–18). Washington, DC: Erlbaum for AERA.

Crowley, K., & Callanan, M. (1998). Describing and supporting collaborative scientific thinking in parent-child interactions. Journal of Museum Education, 23(1), 12–17.

Dysthe, O., Bernhardt, N., & Esbjørn, L. (2013). Dialogue-based teaching. The art museum as a learning space. Copenhagen, Denmark: Skoletjenesten.

Eberbach, C., & K. Crowley, K. (2009). From everyday to scientific observation: How children learn to observe the biologist’s world. Review of Educational Research, 79(1), 39–68.

Everret, M., Piscitelli, B. (2006). Hands-on trolley: Facilitating learning through play. Visitor Studies Today, 9(1), 10-17

Greenwood, d., & Levin, M. (2008). Reform of the social sciences and of universities through action research. In N. K. Denzin & y. S. Lincoln (eds.), The landscape of qualitative research (pp. 57–86). London, England: Sage.

Gresalfi, M. S. (2009). Taking up opportunities to learn: Constructing dispositions in mathematics classrooms. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 18, 327–369.

Haas, N. (1997). Project explore: How children are really learning in children’s museums. The Visitor Studies Association, 9(1), 63-–69.

Kemmis, S., & R. McTaggart, R. (2000). Participatory action research. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (eds.), Handbook for qualitative research (pp. 567–605). London, England: Sage.

Mercer, N. (2002). developing dialogues. In G. Wells & G. Claxton. (eds.), Learning for life in the 21st century: Sociocultural perspectives on the future of education. Oxford, England: Blackwell.

Mercer, N., & K. Littleton, K. (2007). Dialogue and the development of children’s thinking: A sociocultural approach. London, England: Routledge.

Piscitelli, B.,& Anderson, d. (2001). young children’s Perspectives of Museum Settings and experiences, Museum Management and Curatorship, 19(3), 269-282

Piscitelli, B., Weier, K., & Everett, M. (2003). Museums and young Children: Partners in Learning About the World. In S. Wright (ed.), Children, Meaning-Making and the Arts (pp. 167192). Frenchs Forest, NSW: Pearson education Australia.

Star, S. L., & Griesemer, J. (1989). Institutional ecology, ‘translations’ and boundary objects: Amateurs and professionals in Berkeley’s Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, 1907–39. Social Studies of Science, 19, 387–420.

Tsui, A., &. Law, d. (2007). Learning as boundary-crossing in school-university partnership. Teaching and Teacher Education, 23(8), 1289–1301.

Weier, K. (2004). Empowering young children in art museums: Letting them take the lead. Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood Education, 5(1)., 106–116.

Wolf, B., & Wood, e. (2012). Integrating scaffolding experiences for the youngest visitors in museums. Journal of Museum Education, |37(1), 29–38.

Notes

1. Unique features of the context

The location of Tai Tamariki Kindergarten in a national museum is a unique context. This unique context was maximised by teachers finding ways to take small groups of children upstairs on a regular basis, using boundary objects to make connections between contexts, and providing a rich learning and teaching environment at the kindergarten.

As researchers we have been very mindful of the uniqueness of the research context. Our conversations with the teachers at Tai Tamariki have included considerations for early childhood centres or schools not located in a museum, hence our implications for practice endeavour to provide useful ideas for such centres.

2. Acknowledgements

The support from the management of the Wellington Region Free Kindergarten Association (WRFKA)*, reflecting their strong belief in practitioners as researchers, contributed greatly to this research project. The WRFKA Senior Teacher, Paula Hunt, attended research meetings with the whole team (teacher researchers and university researchers), and acted as a thoughtful adviser. We have also appreciated the helpful advice, encouragement, and critique from our New Zealand Council for Educational Research mentor, Rachel Bolstad. Furthermore, the relationship between the research team and Te Papa Tongarewa curators was invaluable during this research project.

* The Wellington Region Free Kindergarten Association amalgamated with Rimutaka Kindergarten Association in August 2014 and is now known as He Whānau Manaaki o Tararua Free Kindergarten Association incorporated.