Introduction

This research project examined the contribution internally assessed course work makes to motivating young people to think historically; that is to develop reasoned, evidence-based understandings of the past that equip them to participate in society as critical citizens who can think independently and adjudicate between competing claims of historical authenticity. Our findings indicate that conducting internally assessed course work makes a major contribution to how students (as novices) learn to think critically about the past. developing the ability to think historically is counter-intuituive and has been described as an “unnatural act” (Wineburg, 2001). It can seldom be acquired from everyday experiences. Rather, it requires systematic instruction in how the discipline of history operates (Sturtevant & Linek, 2004; Alexander, 1997). In this research, it was evident that students (as novices) were able to develop advanced understandings of historical thinking through course work. Their inquiry processes emulated how historians (as experts in the domain) generate and evaluate knowledge.

Key findings

- Thinking historically: Internally assessed course work makes a major contribution to how young people learn to think historically, adjudicate between competing versions of historical authenticity and understand how second-order concepts operate in the discipline.

- Quality teaching: Teachers who had an advanced understanding of how the discipline of history operates were able to provide specific feedback to students during the internally-assessed research process and this was a key contributing factor in young people learning to think critically about the past.

- Motivation: Students were intrinsically motivated to develop advanced levels of disciplinary thinking when they engaged with course work and they did not see external examinations as being as worthwhile in developing historical thinking. They especially valued the personal autonomy of course work and their willingness to commit to the substantial workload required in internal assessment reflected the opportunity this type of learning offered to investigate historical questions that were of personal interest.

Major implications

- If internally assessed course work is to contribute to students learning to think critically about the past, the achievement standards and internally assessed tasks need to explicitly and appropriately reflect the discipline of history (including second-order, procedural concepts).

- If teachers are to provide specific feedback to students during the internally assessed research process that develops their ability to effectively engage in historical thinking, they need to have advanced understandings of both how the discipline of history operates and subject-specific pedagogies.

- Internally assessed course work should be a substantial component of senior history programmes, as the opportunity to investigate historical questions that are of personal interest is an important motivating factor in how young people learn how to think historically.

The research

Background

This research project examined whether conducting internally assessed course work contributes to students (as novices) learning think historically. It contributes to our understanding of how young people learn to think critically, the role of internal assessment in this process, and questions to do with motivation. Learning how to think historically requires young people develop a working knowledge of the disciplinary concepts of history. novices typically develop expertise in a field by emulating experts. we investigated whether students develop expertise in history when they conduct research-based course work. This was based on the hypothesis that novices are likely to learn how to think historically when they conduct research, as this process is an important feature of how experts in the field generate and evaluate knowledge. Investigating if there is a correlation between students conducting internally assessed course work and learning how to think historically is timely. While up to half of the NCEA credits that students accumulate in their senior history programmes are based on internally assessed research-based tasks, there is criticism that this type of assessment is demotivating for boys, lacks academic credibility and that external examinations are a more valid measure of students’ intellectual development (Morris, 2010, Coddington, 2011; New Zealand Listener, 2012).

The question of how young people learn to think historically (and the role of internal assessment in this process) is of especial importance for the social sciences as this learning area of the curriculum is about “how people can participate as critical, active, informed and responsible citizens” (Ministry of Education, 2007. p. 30). Learning how to think historically can make an important contribution to equipping young people to participate in society as critical citizens who can think independently and adjudicate between competing claims of historical “truth”. However, thinking critically about the past is counter-intuituive. It has been described as an “unnatural act” (Wineburg 2001). Disciplinary knowledge in subjects such as history can seldom be acquired from everyday experiences but rather requires systematic instruction in the methodologies, concepts and principles of the domain of the academic discipline as negotiated by experts in the field (Sturtevant & Linek, 2004; Alexander, 1997; McDonald & Thornley, 2009). In the case of history, unless young people have grasped how the discipline of history operates, they typically make sense of the past through community memories and popular media (Wineburg 2001) and their beliefs about the past are shaped by the present, with new information being filtered through often firmly held views (Gardner 1985).

At a wider level, this research contributes to questions about the purpose and place of discipline-informed subjects such as history in the senior secondary school curriculum. Although disciplinary knowledge is “always fallible and open to challenge” (Young 2013, p. 107) Bolstad and Gilbert argue it is through disciplinary thinking that students (as novices) shift from focusing on the superficial features of knowledge to developing the characteristics of experts who tend to “think in terms of deep structures or the underlying principles of knowledge” (2012, p. 15). This research also contributes to our understanding of how young people learn to think critically. Although there is a consensus among educators that critical thinking is an “intrinsic good” (Moore, 2011), there is a division between proponents of generic problem-solving, critical-thinking skills (Ennis, 1989, 1991; Cottrell, 2011) and those who argue that learning to think critically is developed within the frameworks of academic disciplines, such as “historical thinking” (McPeck, 1981, 1990; Brown, Collins, & Duguid, 1989). Finally, this research contributes to our understanding of adolescent motivation and in particular why students who conducted internally assessed course work were intrinsically motivated to complete demanding research-orientated tasks to an advanced level.

Research questions

The two research questions were:

- Does conducting internally assessed research-based course work contribute to young people learning to think historically and developing expertise in how the discipline of history operates?

- What factors make a difference to young people developing expertise in the discipline of history when conducting internally assessed research-based course work?

Methodology

The research adopted a mixed-methods approach to gathering and analysing the data (Levstik & Barton, 2008) including interviewing, focus groups, questionnaires and documentary analysis. Students’ responses were coded using Nvivo 8. The process was informed by a grounded theory perspective that allowed for the complexity of the rich variety of data that was gathered from student’s interaction with their research studies (Glaser & Strauss, 1967) yet was bounded and structured by the research questions above. Our understanding of historical thinking was informed by proponents of the “disciplinary approach” to history education (Lee & Ashby, 2000; Levesque, 2008; Seixas, 1997, 1994; Shemilt, 1987), who argue that learning how to think historically provides young people with reasoned, evidence-based understandings the past.

The focus of the research was on how young people develop an understanding of what are called second-order or procedural concepts, such as significance, perspective, evidence, cause and consequence, and continuity and change (Lee 2004; Seixas & Morton, 2013). Lee (2004) argues that while history may be diverse, it has some characteristic organising ideas and these can be divided into substantive concepts that are linked to content (the substance of history), and procedural or second-order concepts. The former is concerned with the “what”’ of history while the latter is concerned with the “‘doing” of history: in particular, the approaches historians employ when they interrogate the past and construct reasoned explanations of past events. To develop disciplinary expertise requires students develop a firm grasp of these second-order or procedural concepts (Ercikan & Seixas, 2011) and it is through students’ ability to use these concepts that their capacity to think historically becomes evident. The researchers paid particular attention to how students thought critically about the past through variations on the following questions:

- Why are there different versions and interpretations of the past?

- Are there better ways of thinking about or approaching the past than others?

- How do we establish what is important to know about in the past?

For this project, we interviewed 98 (n= 98) history students (ages 16-17) in five schools over a two-year period. All had studied history previously for at least one year and were thus familiar with the protocols and requirements of internal assessment. As well as interviews and focus groups, we also collected documentary evidence (including how students personally evaluated the research process). We interviewed teachers, focusing particularly on how they assessed their students’ work and the nature of feedback they provided during the research process. The majority of participants demonstrated advanced understandings of how the discipline of history operates, so to ascertain if they were typical of their cohort, students in the home classes of those interviewed during 2012 completed a historical thinking questionnaire (n=152). This questionnaire asked students to agree/disagree with a series of statements about Gallipoli that indicated their understanding of historical thinking (such as “what is seen as significant in history changes over time” [agree]; “Primary sources provide more accurate evidence” [disagree]). This questionnaire served as a pilot for a nation-wide survey (n= 2568) to ascertain history students’ ability to think historically. Students in 34 schools throughout the country completed a generic questionnaire where they were asked to agree/disagree with a series of statements that indicated their understanding of historical thinking and consider the question of historical significance in relation to the Treaty of Waitangi. All quantitative data has now been entered on Excel and qualitative data on significance and the Treaty have been transcribed. The analysis process has begun and findings from this part of the study will be disseminated in future publications.

Findings

This study identified that conducting research-based course work was making an important contribution to participants developing strong disciplinary understandings of history. Participants could generally critique the past through an historical thinking framework and this appears to be a consequence of students’ close engagement with the process of how knowledge is produced in the discipline. Participants were also highly motivated to complete these assessments and this appeared to be a consequence of students’ personal autonomy over what they study and the sense of ownership they had of their learning. It was also apparent that the extent to which students were successful in this style of learning was in part due to the knowledge teachers had of how the discipline of history operates and their ability to structure assessments to reflect this, as well as the quality of the feedback they gave to students during the research process.

Interpretation and evidence

Drawing on the work of van Sledright (2011), Seixas and Morton (2013) and Alexander (1997), the researchers constructed a set of criteria (Table 1) to map patterns of epistemological understanding of historical interpretation and evidence. The aim of this framework was to contribute to our understanding of students’ cognition in this area. The intention was not to establish a set of firm criteria that can be used to measure progression. The criteria is largely exploratory at this stage given that empirical evidence of students’ progression in historical thinking is still in a transitional, ongoing phase and is a hypothesis to be “confirmed and revised” based on further research (Ercikan & Seixas, 2011, p. 247).

| Novice (functional) | Competent (emerging) | Expert (powerful) |

| Historians are able to provide a “neutral”, objective explanation of past events. | Historical accounts are interpretations and reflect the historians’ viewpoints. | Historical accounts are interpretations and reflect the historians’ viewpoints

Explanations that draw on reliable evidence are more accurate than those that do not. |

| Knowledge comes from an external source and is certain.

Little grasp of the interpretive nature of historical explanations or that there are multiple versions of past events.

Trusts that the assertions of historians/ textbooks are neutral and objective.

Unable to use disciplinary criteria to judge the relative merits of historical explanations. |

Knowledge is generated by human minds and is uncertain.

Understands the interpretive nature of historical explanations and that there are multiple versions of the past events. Understands that the assertions of historians/textbooks are not neutral and objective. Unable to differentiate between historical arguments that are based on reliable, corroborated evidence and those that are not. |

Knowledge is generated by human minds and is uncertain.

Understands the interpretive nature of historical explanations and that there are multiple versions of the past events. Understands that the assertions of historians/textbooks are not neutral and objective. Able to differentiate between historical arguments that are based on reliable, corroborated evidence and those that are not. |

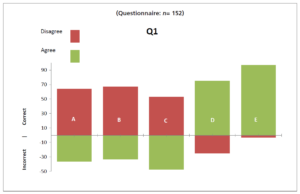

Figure 1 shows students’ responses to the statements in the questionnaire about historical interpretation and evidence. It demonstrates their understanding of how these disciplinary concepts operate in history based on the criteria in Table 1.

The statements were:

A: Primary sources provide more accurate evidence.

B: Historians will eventually be able to uncover all of the relevant evidence about the Gallipoli campaign.

C: Eye witness accounts of soldiers fighting in Gallipoli are more reliable than historians writing after the event.

D: Historians will never be able to fully understand what happened at Gallipoli in 1915.

E: Some historical accounts are more accurate than others.

Figure 1 Students’ responses to statements about historical interpretation and evidence

What advanced understandings look like

About two-thirds of participants interviewed demonstrated advanced notions of how the discipline of history operates in regards to the reliability of sources and the interpretive nature of history. This was also reflected in the wider cohort where (with the exception of statement 3: only 53 percent correct), most students demonstrated an understanding that historical explanations are always interpretative and of how the second-order concept of evidence operates. These students had a good grasp of the strengths and weaknesses of sources and demonstrated an understanding that objectivity is not a realistic option for historians, as shown in the following comments:

Well a good thing to do with sources, especially with reliability, is comparing them to other things. So if it is an account of a certain event like the Cuban Revolution, to compare it to another source that also has the same things happening, you can tell whether it’s true or false or whether it’s just a perspective or whether someone’s just kind of put forward their own point of view.

I think it is important not to read any historical document and see it as fact, I think you have to read multiple ones and draw a personal opinion. Anything can be biased and probably will be if it is written by someone who knows a lot about the topic, so I think as long as enough information is provided then people will be able to draw their own conclusions from what has happened in history and you can work out by cross checking everyone’s information that is out there as well.

One student initially argued that truth is attainable when accounting for the past (where there is historical evidence to support a particular claim) but when asked to what extent it was possible for historians to fully account for the actions of individuals in the past, he conceded that this would not be possible and our experiences over time can change how we remember the past:

It’s something you will never truly know. you can guess at it, but you can never be completely certain. The person might lie or have changed their mind over time so you can never actually know what the person is thinking.

What emerging and novice understandings look like

About 20 percent of participants interviewed were working at a competent level with regard to evidence and interpretation, and were able to clearly distinguish that there were multiple perspectives of the past; however, they were less confident about establishing why there were different views. Typically, when pressed, they tended to revert to there always being “two sides to any view of the past”:

There are two sides to every story, so then there are different points of view and you can’t say one is necessarily better unless you are trying to look at it from their point of view.

It depends who writes history, so there are always two sides to something so if you went and looked at world war II and if you were in germany and you looked at it and they would be giving Hitler’s point of view but if you came over here the Allies recalled history in a different way. It’s who you see and what side you want to believe. So it’s who is writing it and everyone has different interpretations, different cultures see different things.

A minority of about 10 percent of students were working with weaker notions of the past with novice level responses such as “there is no real way to know what actually happened in history but what is important is what your teacher thinks happened” or “back a long time ago, then it was the leader who wrote the history or told people to write the history for them, but now it’s like diverse. People write books and they’re more free”. The first indicates a student who is functioning at a very low level of understanding of how the discipline operates (very much accepting the authority of the teacher) while the latter statement reflects a high-trust model that our understanding of historical knowledge is progressing over time. There were also comments such as “history is written by the victor”, and a number of participants who expressed a naive, high-trust model of the authority of historians/textbooks as being neutral and objective.

In my project I chose to use quite a neutral character because I did a diary so I chose to use a person with a neutral view on the partition and they had to have an equal view of both sides and not be too on one side or too much on the other side, in the end I chose a social scientist because then they would understand the balance of having an equal view and not judging things by certain events and they would look into things deeper so it worked quite well because then it was not too biased on either side.

Historical significance

As with the criteria above (Table 1), the researchers drew on the work of van Sledright (2011), Seixas and Morton (2013) and Alexander (1997) to construct a set of criteria (Table 2) to map patterns of epistemological understanding of the concept of significance. Significance is a second-order, procedural concept that plays a central role in how historians operate. Historians cannot study everything that happened in the past so they select particular “historical events, personages, dates or phenomena that are more important to their studies than others” (Levesque, 2008, p. 41).

Table 2 Levels of epistemological understanding of historical significance

| Novice (functional) | Competent (emerging) | Expert (powerful) |

| Passive view of what is significant in history. What is significant is unquestioned, fixed and permanent. | Significance changes over time. It is not fixed and depends on historians’ community perspectives.

Unable to differentiate why some events are more significant than others. |

What is significant in the past changes over time. It is not fixed and depends on historians’/community perspectives.

Able to differentiate why some events are more significant than others. |

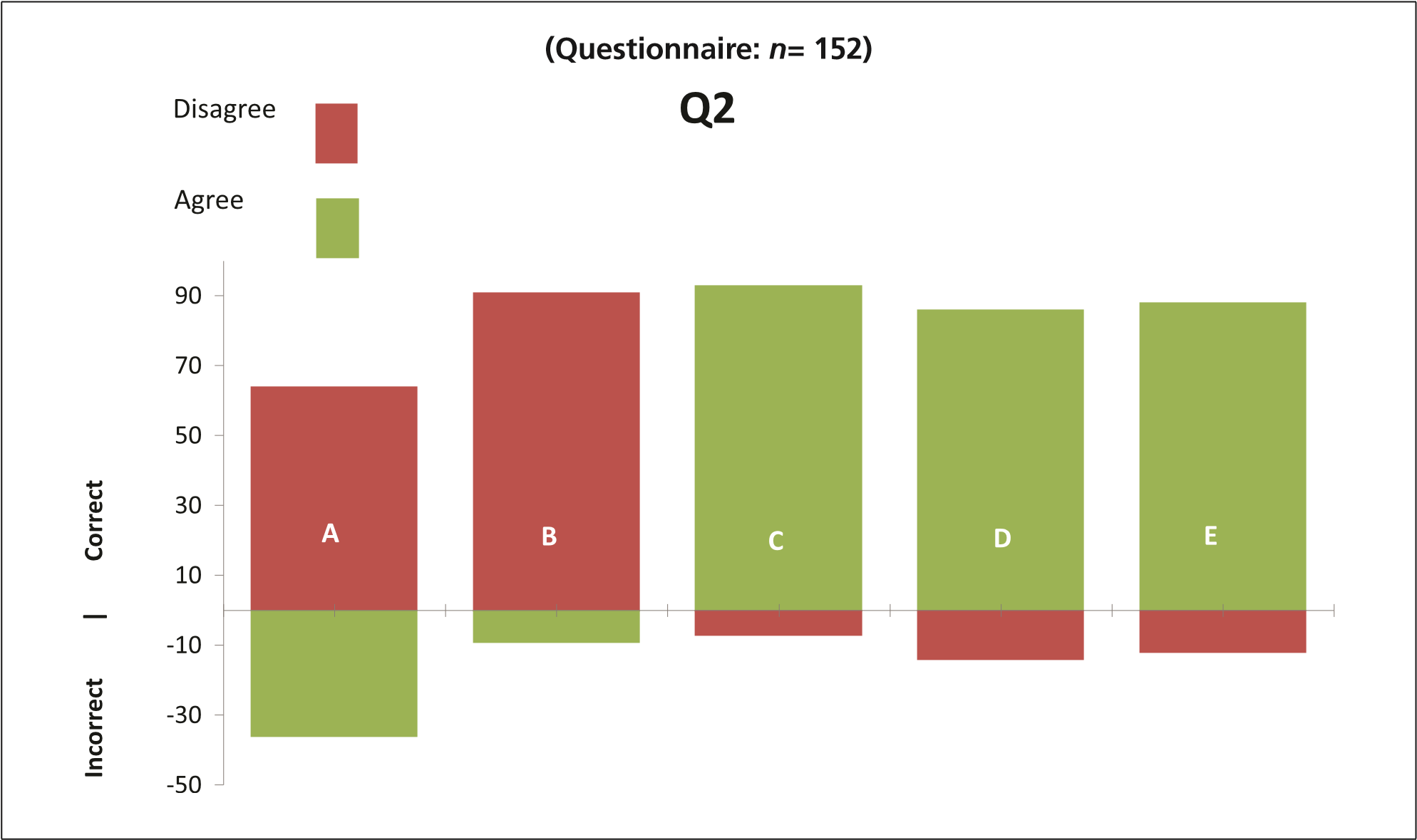

Figure 2 shows students’ responses to the statements in the questionnaire about historical significance. It demonstrates their understanding of how this disciplinary concept operates in history based on the criteria in Table 2.

A: Primary sources provide more accurate evidence.

B: Historical events that are significant to New Zealanders are significant to the rest of the world.

C: The reasons that New Zealanders see Gallipoli as significant will depend on their personal perspectives about this event.

D: What is seen as significant in history changes over time.

E: Not all New Zealanders see ANZAC day as significant today or have done so in the past.

Figure 2 Students’ responses to statements about historical significance

The question of historical significance is currently of some importance in the New Zealand history teaching community (Harcourt, et al., 2011) and was one of the major areas of focus for the interviewers. While teachers have considerable autonomy in how they shape their programmes (and for internal assessment, students typically choose their own topics), the curriculum and achievement standards require history programmes to be “of significance to New Zealanders”. While students had a good grasp of how the concept of significance operates in the discipline, what appears to be troubling is the grafting of the phrase “to New Zealanders” on to significance. This phrase is required in most of the achievement standards and it appears to be confusing students. To address this requirement, participants were typically adopting a literal response that either looked at specific New Zealand events and personalities in isolation or, when studying international contexts, made explicit links with a New Zealander who had been involved in some way. For example, the Cambodian genocide was claimed to be significant by a number of students because a New Zealander was tragically captured, tortured and killed there, rather than the students ascribing significance on criteria that reflects historical thinking (Seixas, 1997; Seixas & Morton, 2013):

[W]e had to relate it back to New Zealand and Cambodia actually had a New Zealander die at the hands of the regime so that made it easier.

Participants typically saw “significance to New Zealanders” as an inconvenient “add-on”:

The significance to New Zealand part I thought was at times very frustrating . . . they want more to discuss the direct parallels with New Zealand which I think is frustrating and sometimes difficult to do. New Zealand is a very small place on the global scale and drawing parallels to New Zealand is a bit stretched because of the fact that there is not a whole lot of things that you can really say because New Zealand is a small place and it hasn’t been colonised for that long so.

In one internally assessed study (that the whole class had completed), students had been asked to compare the battle of the Little Big Horn in Dakota in 1876 with the defeat of the British in the New Zealand wars some 30 years earlier. The comparison to participants felt awkward as they felt the New Zealand experience wasn’t very important:

I think that it’s hard to make these comparisons with the Battle of Little Bighorn and New Zealand because sometimes I don’t really think that it was actually significant to New Zealand and the only way you could write about significance was just saying that they were similar in this way.

Students in this example were not engaging with significance in a way that reflected an understanding of how the concept of significance operates in the discipline. For example, they had not been encouraged to consider why Americans see the battle of the Little Big Horn as significant whereas New Zealanders do not see a similar event in the same light. In reality, the actual events were not so very different. They were both relatively minor nineteenth century, frontier conflicts in which indigenous people were able to defeat a colonising military force but neither battle had a major effect on the overall settlement of these frontier societies. However, what students were not able to do is critically reflect on why in America the “battle of the Little Big Horn” is seen to be of significance while in New Zealand a similar event is not.

It is not uncommon for students to have sophisticated levels of understanding of one particular second-order, or procedural, historical thinking concept and not others (Ercikan & Seixas, 2011). However this does not appear to be the case with these participants in regard to significance. Although the question of significance is challenging for young people (Counsell, 2004), the findings from the questionnaire indicate that most students in this cohort had a good grasp of the concept. Rather, it appears that it is the inclusion of the phrase “of significance to New Zealanders”’ in the achievement standards that is proving problematic. one of the project’s teacher researchers argues that in addressing this question, teachers and students need to problematise “of significance to New Zealanders” (Enright, 2013). That is, they need to see this phrase as not fixed but rather as a contested term. In this, he is reinforcing the historical thinking ideas that are at the heart of how this phrase is intended to operate in the curriculum achievement objectives (Ministry of Education, 2007) where the grafting of “to New Zealanders” on to significance provides the opportunity to provide an additional dimension to teaching and learning history in the twenty-first century. Another teacher on the project put it this way:

We have taken a really empathetic approach to try and really get into the minds of what was going or to really try to understand perspectives and so they are wanting to empathise with a problem, not necessarily as a New Zealander but as a human who has emotions and who has compassion and . . . thinking as a New Zealander rather than just thinking of it as a world citizen or as a human

Motivation

Participants were highly motivated to complete these assessments to an advanced standard through their experiences of internally assessed course work. The credits earned for this component of the programme were an extrinsic motivating factor for participants. Students commented that given the workload pressure of the senior school (and because internally assessed projects took a considerable amount of effort and time), they had to prioritise the areas of their courses they focused on. credits did make a difference in motivating students to develop disciplinary expertise (Meyer et al., 2009). Typically one student indicated that:

if I didn’t have the incentive of getting excellence credits with it, I probably would put less effort into the work that I would do . . . I would be less likely to work on that of my own accord and go to the extent of research that I would if there was credits available.

However intrinsic motivation also played a significant role in motivating students to develop disciplinary thinking. course work in history had a reputation among the participants as requiring a considerable time commitment in comparison with other subjects, yet these students highly valued this process and saw it as intrinsically worthwhile. This high level of motivation appears to be the result of the personal autonomy they enjoyed in choosing what they studied. one student indicated that in internal assessment she was “learning for the sake of learning and because of this and because I am learning for myself I almost feel like I want to do my own ideas justice”. Another talked about the “joy” he got out conducting research projects and that he had “enough space to work in a way that suits me” and “the best opportunity to show how much I have learnt and my enthusiasm for the subject”. The willingness to commit to a substantial workload was in part shaped by the opportunity internal assessment gave partipants to investigate historical questions that were of personal interest (as well as the opportunity to develop particular research skills).

[Y]ou get into it and you kind of feel yourself learning and knowing more about what is going on. we had to do the research first and I was going through heaps of stuff and information and finding out all these new things as evidence which can be useful for answering questions, and then you feel like you are really knowledgeable and it’s not like something that is a grueling task, you just want to go and write this report and make it the best that you can and it is about making something so that when you are done you feel like you have gained some intelligence from it.

Although these students were typically academically successful, they did not see external examinations as being as valuable in developing historical thinking. This is of interest as the external examinations in history are largely shaped around the disciplinary concepts in the curriculum. They include disciplinary approaches such as source analysis and writing essays that require students to argue a point of view supported by evidence (Ministry of Education, 2011). Participants, however, generally saw internal assessment as making a more worthwhile contribution to developing their ability to think critically about the past, compared with external exams, as well providing knowledge that was of more long-lasting value:

I find with researching any topic that I often look at two different accounts just to see who is right, but with the externals it’s a lot more narrow a path and I just do is two or three essays on what we have learnt this year and just memorise everything from that and then prepare for the question.

It works a lot better than the externals where we are just memorising a bunch of facts and essay structure and putting it together. with this [internal assessment] your motivation isn’t just to get the credits at the end, you find yourself being driven by your interest and because you have got the time it’s not just about passing the essay, you are given this space to explore, so it’s a lot better for history as a topic

Teacher feedback

Teachers who had an advanced understanding of how the discipline of history operates were able provide specific feedback to students during the internally assessed research process and this is a key contributing factor in young people learning to think critically about the past and to think historically. These teachers not only had a firm grasp of the explicit requirements of the achievement standards but also how to draw out the historical thinking ideas that inform these standards. This was reflected in how they marked students work, with one teacher talking about knowing enough about the the discipline to “have the confidence to trust your own judgment”.

Limitations of the project

The project had the following limitations:

- This study did not include a comparison with external examinations and it would be useful to do so with a particular focus on how young people develop understandings of second order concepts in history.

- This study would benefit from a second study of historical thinking in 3–5 years’ time, once the alignment of the New Zealand curriculum with the achievement standards has been embedded.

- This research was informed by students in five schools where history was a strong subject. As such, it is a “point-in-time” study that could be used to evaluate the extent to which young people are learning to think historically in less advantaged schools. This evaulation process has begun with the gathering of data from a historical-thinking questionnaire (n= 2568) from a diverse range of 34 secondary schools from throughout the country.

Conclusion

The ability to think critically about the past is a key feature of critical citizenship. Through conducting internally assessed course work, participants in this study were developing advanced understandings of how the discipline of history operates and learning how to think historically. This appears to be an outcome of emulating how historians make and critique “truth-claims” when they conduct research. This was especially apparent among students with regard to their understanding of the contested and interpretive features of the subject. Participants typically had a good grasp of the strengths and weaknesses of sources and the need to be cautious of accepting historical arguments at face value. generally they were developing the critical, analytical tools that historians use to interrogate the past and (despite the substantial workload) they saw internally assessed research-based course work as intrinsically valuable in developing the ability to think historically, and more worthwhile than external examinations. course work is making a major contribution to how these young people were learning to participate in society as critical citizens who can think independently and adjudicate between competing claims of historical authenticity.

Recommendations

Quality teaching: To be able to teach their students to think historically, history teachers need to have advanced understandings of both how the discipline of history operates and appropriate subject-specific pedagogical approaches. developing the ability to teach young people to think historically should be central to how history teachers are educated both at preservice level and throughout their career (through professional development opportunities). History teachers should also have experienced opportunties to personally engage in the research process at postgraduate level.

Achievement standards: Both external and internal achievement standards should be regularly monitored by subject experts to ensure that they appropriately reflect secondorder concepts of historical thinking such as significance.

Social sciences: Historical thinking is not only a priority for senior history programmes: students in all secondary social science programmes (including social studies) should learn to think critically about the past as this is a core component of being able to participate constructively in society as critical citizens .

References

Alexander, P. A. (1997). Mapping the multidimensional nature of domain learning: The interplay of cognitive, motivational and strategic forces. Advances in Motivation and Achievement, 10, 213–250.

Bolstad, R., & Gilbert, J. (2012). Supporting future-oriented learning and teaching – A New Zealand perspective. Wellington: Ministry of Education.

Brown, J. S., Collins, A., & Duguid, P. (1989). Situated cognition and the culture of learning. Educational Researcher, 18(1), 32–41.

Coddington, D. (2011, July). Blowing the whistle. North & South, 304, 50−56.

Cottrell, S. (2011). Critical thinking skills. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Counsell. C. (2004). Looking through a Josephine Butler shaped window: Focussing pupils’ thinking on historical significance. Teaching History, 114, 30–36.

Ercikan, K., & Seixas. P. (2011). Assessment of historical thinking. In G. Schraw & D. H. Robinson (Eds.), Assessment of higher order thinking. Information Age: Charlotte. N.C. pp. 245-259.

Enright, P. (2013). Issues of significance: centralising significance. History Teacher Aotearoa, 1(1), 16–27.

Ennis, R. H. (1989). Critical thinking and subject specificity: clarification and needed research. Education Researcher, 18(3), 4–10.

Ennis, R. H. (1991). Critical thinking: A streamlined conception. Teaching Philosophy, 14(1), 5–24.

Editorial. (2012, March). New Zealand Listener, 24−30.

Gardiner, H. (1985). The mind’s new science: A history of the cognitive revolution. New York: Basic Books.

Glasser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. New York: Aldine.

Harcourt, M., & Sheehan, M. (Eds.) (2012). History matters: Teaching and learning history in 21st New Zealand. Wellington: NZCER Press.

Lee, P. (2004). understanding history. In P. Seixas (Ed.), Theorizing historical consciousness (pp. 129–164). Toronto: university of Toronto Press.

Lee, P., & Ashby, R. (2000). Progression in historical understanding among students ages 7–14. In P. Stearns, P. Seixas, & S. Wineburg (Eds.), Knowing, teaching and learning history. (pp. 199–222). New York: New York University Press.

Levesque, S. (2008). Thinking historically: Educating students for the twenty-first century. Toronto: university of Toronto Press.

Levstik, L., & Barton, K. (Eds.) (2008). Researching history education: Theory, method and context (pp. 273–289). New York: Routledge.

Mcdonald, T., & Thornley, C. (2009). Critical literacy for academic success in secondary school: Examining students use if disciplinary knowledge. Critical Literacy: Theories and Practices, 3(2), 56–68.

McPeck, J. E. (1981). Critical thinking education. New York: St Martin’s Press.

McPeck, J. E. (1990). Critical thinking and subject specificity: A reply to Ennis. Educational Researcher, 19(4), 10–12.

Meyer, L. H., Mcclure, J., Walkey, F., Weir K. F., & Mckenzie, L. (2009). Secondary student motivation orientations and standards-based achievement outcomes. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 79, 273–293.

Ministry of Education. (2007). The New Zealand Curriculum. Wellington: Learning Media.

Ministry of Education. (2011). New Zealand curriculum guides: senior secondary: History. Retrieved from http://seniorsecondary.tki.org.nz/ Social-sciences/History

Moore, T. M. (2011). critical thinking and disciplinary thinking: A continuing debate. Higher Education Research and Development, 30(3), 261–274.

Morris, J. (2010). The Headmaster, Ad Augusta Auckland Grammar School. volume 18, no. 3, page 3. Retrieved from: http://www.ags. school.nz/static/content/file/ad_augusta_may_10.pdf

New Zealand Listener. (2012, April 14). Editorial.

Sexias, P. (1994). Students’ understanding of historical significance. Theory and Research in Social Education, 22, 281–304.

Sexias, P. (1997). Mapping the terrain of historical significance. Social Education, 61(1), 22–27.

Seixas, P., & Morton, T. (2013). The big six historical thinking concepts. Toronto: Nelson Education.

Shemilt, D. (1987). Adolescent ideas about evidence and methodology in history. In C. Portland (Ed.), The history curriculum for teachers (pp. 39–61). London: Heinemann.

Sturtevant, E. G., & Linek, W. M. (2004). Content literacy: An inquiry-based case approach. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education.

vanSledright, B. (2011). The challenge of rethinking history education. New York: Routledge.

Wineburg, S. (2001). Historical thinking and other unnatural acts: Charting the future of teaching the past. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Young, M. (2013). Overcoming the crisis in curriculum theory: A knowledge-based approach, Journal of Curriculum Studies, 45(2), 101– 118.

Publications from this study

Sheehan, M. (2013). Learning to think historically through course work: A New Zealand case study. International Journal of Historical Learning and Teaching and Research, 11(2), 129–137.

Sheehan, M. (in press). “History as something to do not something to learn”: Historical thinking, internal assessment and critical citizenship. New Zealand Journal of Educational Studies, 47(2).

Enright, P. (2013). Issues of significance: centralising significance. History Teacher Aotearoa, 1(1), 16–27.

Sheehan, M. (2013). The case for historical thinking: Learning to think critically through inquiry-based history research projects. In V. Ham, R. Davey, & J. Fenaughty (Eds.), International Conference on Thinking: Proceedings of the 16th International Conference on Thinking (ICOT), Core Education, Christchurch, pp. 173-179.

Enright, P. (2012) Kua takato te mānuka: The challenge of contested histories. In M. Harcourt & M. Sheehan (Eds.), History matters: Teaching and learning secondary school history in the 21st century, (pp. 85–104). Wellington: NZCER Press.

Sheehan, M., Howson, J. (2012). Learning to think historically: developing historical thinking through internally assessed research projects. In M. Harcourt and M. Sheehan (Eds.), History matters: Teaching and learning history in 21st New Zealand, (pp. 105–115). Wellington: NZCER Press.

Sheehan, M., Enright, P. Davison, M. History matters 2: Thinking critically about the past in the secondary social sciences. Manuscript in progress. NZCER Press.

About the author

Dr Mark Sheehan is a senior lecturer in the Faculty of Education at Victoria University of Wellington where he teaches undergraduate and postgraduate courses on teaching and learning history and curriculum theory. He has been involved in history education for more than 25 years as a writer, presenter, teacher, researcher, museum educator and curriculum designer. His research interests include teaching and learning history, critical thinking and assessment and the place of disciplinary knowledge in school curricula.