Tū mātātoa, kei kiriora tō tū[1]

Stand strong lest you become complacent

A child in this study told us that he had learned he was brave by travelling on a Halloween train journey that engendered fear and trepidation. Months later, this child asked a researcher that his teacher be told he was ‘the brave one’. When asked why, he explained that his teachers would feel comfortable giving him more difficult tasks: “I am brave to give it a go … I’m not scared so it would help me because I wouldn’t be scared, I’d be brave. She would know that I’m not scared of anything so she doesn’t have to be worried; if there was a task and she would think I’m scared of it—I’m not.”

Tū mātātoa, kei kiriora tō tū

Stand strong lest you become complacent

Tū mātātoa

This term encourages the notion that learning is a process that requires specific attributes—focus, clarity of intent, circumspection, a will to learn, self-discipline, courage, energy. It also encourages a child to be single-minded when asked to explore the unknown. In regards to our project, it reflects that learning can occur in many different ways. Hence, the interpretation of knowledge not only becomes an act of information attainment, but also increases self-esteem and development of learning skills—that is, the child’s understanding of the unknown is enlightened and barriers of doubt demolished. This process again requires a specific set of dispositions and an environment that assists in unleashing a child’s potential, resulting in an evolution of individual learning strategies. The outcome of this process is encapsulated by the terms considered when formulating this whakataukī, ‘courage/learning/believing in oneself/willingness to face fear’.

… kei kiriora tō tū

In the Māori world, and particularly in the use of whakataukī (proverb) and whakatauākī (quote), there exist in many circumstances, words, phrases, epithets, that act as gentle reminders to the consequences of our actions. This is exemplified in the second aspect of this whakataukī that suggests what will occur if a child’s potential is not realised or encouraged. In regards to this whakataukī, the warning is not primarily for the children, but implicates those responsible for the teaching and learning of our children—teachers, parents, and whānau. This implicitly voices elements of both individual and collective acts of responsibility of teaching and learning. This is best encapsulated by the following enquiry: “How can teachers, parents, whānau ensure that our children’s desire to learn can be encouraged so that their experiences of learning can develop an inquisitive mind with clarity and self-discipline?” The response to that query supports the justification of this whakataukī.

1. Introduction

Learning and personal development are integral to the human condition. Both learning and teaching are integral to life as a social being. As professional educators, we are socialised to think of learning and teaching first and foremost as professionally planned, curriculum–oriented activities that take place in institutionalised educational settings (kōhanga reo, early childhood centres, kura and schools, wānanga and tertiary education organisations). However, we also know that ‘students’ spend the considerably greater part of their days and years simply as ‘children’.

Rizvi (2007) argues it is important to develop a language of learning, which emphasises “collective, critical and reflective learning, as well as learning from experience” (p. 129). However, informal and everyday learning is broadly understood as being “largely invisible, because much of it is either taken for granted or not recognised as learning” (Eraut, 2004, p. 249). Various efforts have been made to clarify the phenomenon of informal learning. Initial attempts often did this by contrasting with formal learning. For Schugurensky (2015), defining something by what it is not does not help to reveal its qualities. Also, it “places informal learning at the margins of the margins” (p. 20).

Callanan, Cervantes, and Loomis (2011) reviewed research about informal learning and proposed five dimensions, which we use as a working definition for informal learning. Informal learning is typically nondidactic, highly socially collaborative, embedded in meaningful activity, initiated by learners’ interest or choice, and not externally assessed (Callanan et al., 2011).

Children participate in everyday activities and settings alone, as members of whānau, friendship networks, faith and culture groups, activity clubs and societies, and the like. All this, too, involves learning and teaching. In everyday activities and settings, repertoires of children’s learning vary from the informal and incidental to the formal and instructional. Similarly, whenever children are at home and in their local neighbourhood’s natural and built environments, they encounter diverse forms of teaching that seek to influence and shape their learning. These pedagogical forms are embodied in, for example, streetscapes and public spaces, advertising and commercial signage, fairs and festivals, kapa haka competitions, cultural events and gatherings, museums and galleries, spoken word events, street theatre, fashion, body art, graffiti, the playing out of youth popular cultural rituals, and so on and so forth.

We know that the nature and forms of learning and teaching in neighbourhood communities are likely to vary considerably according to the child’s social class location and what they have to learn to negotiate outside the home. In some communities, mobile truck shops, bottle stores, and fast food outlets are ubiquitous; in others, there are gated housing enclaves and manicured playgrounds and sports facilities. Children learn a lot from their often multiple, fluid positionings within their birth and/or blended family structures, and through their or their family’s interactions with agents and institutions of the state. The point is that everyday life provides innumerable opportunities for children as both learners and teachers to acquire the knowledge, skills, and dispositions of how to act as autonomous agents and social beings. Typically, children are successful learners and teachers in many aspects of their everyday relations, activities, and settings.

Against this, as researchers and teacher educators we have become concerned at what we see as the increasingly narrow, simplistic focus on the quantifiable and measurable achievement outcomes of children resulting from their time spent in formal educational settings, as opposed to judgements about the holistic quality of children’s learning and development which draw both on their time in early childhood education or school, and their complex lives outside school. During the 3 years when this research was undertaken (2015–17), education policy and professional discourses were dominated by Better Public Service (BPS) targets, specifically the proportions of children in Years 1–8 achieving at or above National Standards (NS) in reading, writing, and mathematics; and the proportions of students leaving secondary school with National Certificate of Educational Achievement (NCEA) Level 2.

It seemed to us that an emphasis on NS and BPS targets had led well-intentioned politicians, officials, and educators to forget a very basic fact about learning that we all know from our own childhoods and from the experience of being parents or grandparents, aunts, and uncles. Namely, that:

children learn through the demands they meet and through the demands they put on others in everyday activities in activity settings participating in different institutions. Children’s learning takes place through orientation to demands that dominate the different activity settings. (Hedegaard, 2012, p. 136)

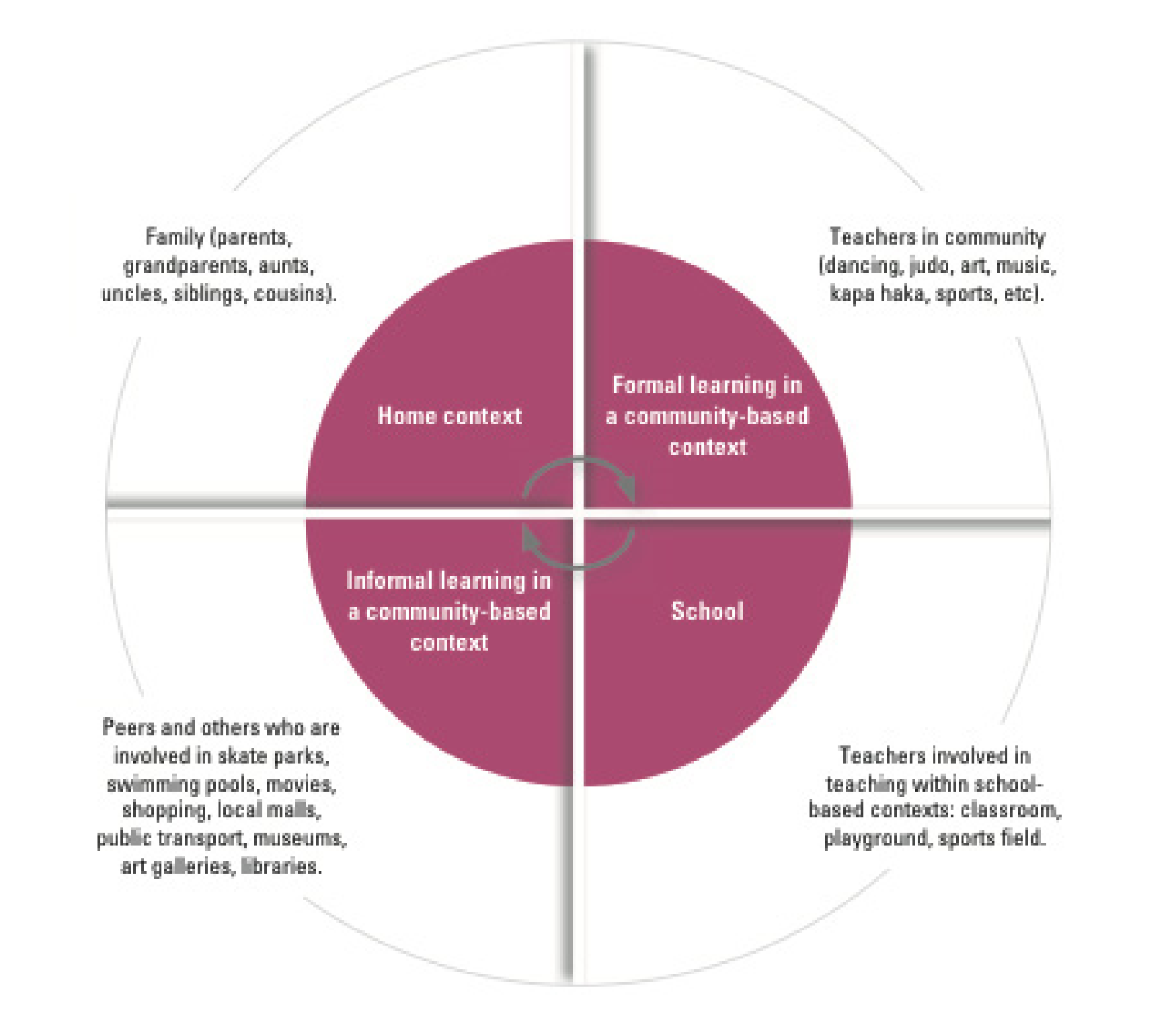

On this basis, it seems sensible to draw explicitly on the learning strengths (knowledge, skills, dispositions) that children bring from everyday activities to the formal education setting of, in this study, the senior primary school. In that sense, we realised that our project would require us to work both with children, as students, and with their teachers, as learners, within a broad scope of informal and everyday learning. Figure 1 shows the scope of diverse formal and informal ‘teaching’ roles in community, school, and family contexts, and we argue that informal and everyday learning can include formal contexts (e.g. schools). Teachers have a role to play in the informal learning of children at school through recognising informal and everyday learning in the classroom and playground, as well as in these children’s lives outside school. As noted later in this report, this awareness enables teachers to gain a deeper knowledge and appreciation of children as learners.

For this research project, we intentionally sought partner schools in socioeconomically disadvantaged, lower decile schools. We also made a conscious decision to carry out the research in ethnically and culturally diverse communities. On the one hand, this was for us an issue of social justice—based on the maxim that one should do educational research where it is likely to have the most benefit. On the other hand, we went into the research anticipating that it would be in communities where we might expect children to experience and have to negotiate the most challenging differences between the cultures of their home and community, and those of their classroom and school.

The overarching research question we developed for the research project was:

How can knowledge of students’ informal learning outside of school enhance teaching and learning practice in the classroom?

This overarching question was broken down into two research sub-questions that we planned to investigate over the 3 years of the TLRI project grant. Each of these in turn was articulated in three parts or strands, as follows:

1. How can children meaningfully identify and document their own learning? (Years 1 and 2)

- What is the impact on children’s learning when they develop their own research question with regards to their informal learning and then document their own learning through rich media autobiographies?

- Do children see the link between their learning outside of school, and their learning at school?

- How does the Children Research Advisory Group (CRAG) inform research with children?

2. What can teachers and family/whānau learn from children’s out-of-school informal learning to better support them in formal and non-formal learning activities at school? (Years 2 and 3)

- How can teachers learn to adapt their pedagogical practice using a strengths-based approach to better support their students’ learning in the classroom?

- How do multiple teacher communities learn to adapt pedagogical practice across schools?

- What practical, evidence-based resources can be developed to assist teachers and family and whānau to better support children’s learning?

Figure 1: The scope of informal and everyday learning across contexts

2. Conceptual framework

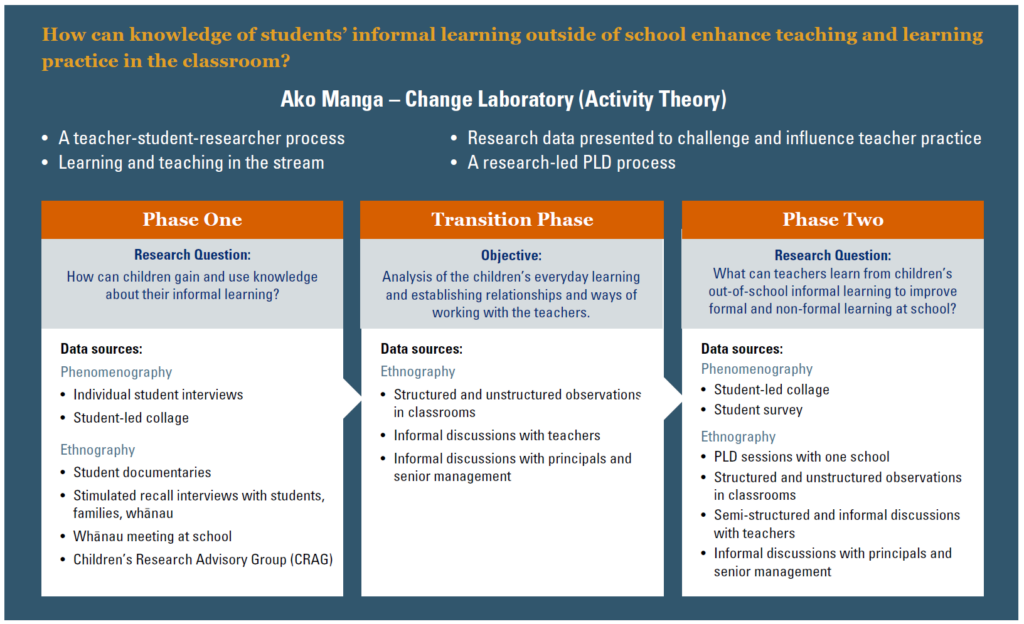

The learning of both the participating students and their teachers was investigated within their everyday learning communities or networks of activity using Cultural Historical Activity Theory (CHAT) (Engeström, 2009). CHAT analyses are concerned with the communities, rules, mediating artefacts, divisions of labour, roles, and motives of an activity system. To support and investigate the teachers’ learning in the study, we adapted the ‘change laboratory’ (Engeström, 2009; Engeström, Miettinen, & Punamaki, 1999) for the Aotearoa New Zealand context, referred to here as Ako Manga. Ako Manga was an intentional, structured, collaborative approach to professional learning and development (PLD) used to promote innovation within the class, syndicate, or school.

In third generation CHAT, Change Laboratory requires an active intervention within the authentic context of the classroom, and the engagement of researchers, teacher researchers, students, and classroom teachers. By reframing the Change Laboratory process to Ako Manga, we were able to connote ‘learning and teaching in the stream of action’. This became a research-led PLD model that enabled teachers to constantly re-negotiate the purposes and focus for their classroom and students, within the broader frame of children’s informal and everyday learning experience.

2.1 Method

There were two main phases to the 3-year programme of research, one focused on understanding children’s everyday learning. In this phase of the research, 36 children (Years 5–6 students, 9–10-year-olds) were interviewed about their learning outside-of-school and asked how they knew when they had learned something.

These children included 20 female and 16 male with a high proportion of Māori learners (58% identified as Māori; 33% NZ European; 6% Pasifika; and 3% other (e.g. Irish)).

The second phase focused on systematically supporting and evaluating changes in the pedagogical practices of teachers as they attempted to strengthen the links between children’s everyday learning and their learning in school. There was also a transitional phase between the two main phases while we completed the analysis of the children’s everyday learning and established relationships and ways of working with the teachers for the Ako Manga in action (see Figure 2).

During these two phases we employed complementary data generating methods within a CHAT analysis framework to generate rich data sets. In the first phase, we used phenomenography to ‘map’ the phenomenon of everyday learning from the learner’s perspective (Marton, 1981, 1986; Marton & Booth, 1997). This was followed up with an ethnographic study focused on understanding the children’s everyday learning in their multiple activity systems. A key feature of the data generation in this phase was that the children used iPads, as mediating artefacts, to both collect data about their learning and facilitate the production of rich media learning documentaries or autobiographies. Given that both the partner schools in phase one of this study had over half the student roll identifying as Māori, and both had bilingual classes, the use of ‘pūrākau’ (or storying) (Lee, Pihama, & Smith, 2012) was employed to facilitate the participation of Māori learners. In the second phase we used both ethnographic and unstructured and structured observations in the classroom, individual and focus group interviews with teachers, informal discussions with teachers, principals, and senior management, and other forms of data gathering. At times the teachers requested the type of data to be gathered as they sought to more fully understand their students’ everyday learning and link it to learning in the classroom. As data were generated and analysed in both phases, particular attention was given to the communities, rules, mediating artefacts, divisions of labour, roles, and motives of all the activity systems.

Figure 2: Overview of research questions and methods

2.2 Collaborators and participants over the 3 years

In phase one of the research we worked in partnership with two schools, and an additional two schools were involved in phase two. A strength of the partnership schools was their considerable student diversity. The school decile is given for the year each was approached to partner in the research.

School A, Decile 4 (2014), Roll: 450 (50% identified as Māori; 8% Pasifika).

School B, Decile 1 (2014), Roll: 170 (66% identified as Māori; 8% Pasifika).

School C, Decile 1 (2015), Roll: 245 (56% identified as Māori; 24% Pasifika).

School D, Decile 3 (2015), Roll: 290 (32% identified as Māori; 7% Pasifika).

The research gained ethics approval through the Massey University Ethics Committee. Initially, 99 students participated in a collage process to represent their everyday learning and a further 26 children from another school did so in a later phase (total n = 125). From the initial 99 students, 36 of these were individually interviewed, A further 12 children were more intensively involved in documenting their informal learning over an 18-month period. For the potential 12 students in the in-depth phase, whānau meetings were held for families of the students in their own school setting. In these research contexts it was important that we conducted the hui according to tikanga Māori, including mihi whakatau, karakia, and kai. Although these hui could be seen as a means to disseminate project details, research participant information, and to generally answer any queries regarding the research process, they were much more than this; they were about meeting kanohi ki te kanohi and establishing relations and trust in culturally relevant ways (see Bourke, Loveridge, O’Neill, Erueti, & Jamieson, 2017).

In total, 10 teachers across the four schools were involved during the course of the project. The Ako Manga phase involved three schools and nine teachers. In phase two, two teachers in one of the original schools continued their work on what they had learned from the children’s ideas about informal learning to change their practice. In addition, three teachers from another school, and four teachers from a further school engaged with the way that children understood their informal and everyday learning.

2.3 Method in action

We explored how young students learn outside school in both cultural and social contexts as active members of multiple learning communities.

i. Student-led collage development on their informal and everyday (99 Years 5–6 students across two schools).

ii. Phenomenographic interviews with 36 (Years 5 and 6) children on informal learning outside-of-school. Individual semistructured interviews were undertaken with children to explore the phenomenon of informal learning in their lives.

iii. Student learning documentaries. The object of this ethnographic phase of the research was to have a small number of students (n = 12) develop documentaries about their informal learning using digital tablets (iPads) supplied to them through the research project, in order to gain a clearer understanding of the complexity of their everyday learning. The children were acknowledged at the end of the research through a Certificate of Participation.

iv. Children attended a day-long workshop at Massey University where they were introduced to concepts and examples of storying and story boards to structure their personal accounts. Children then continued to work on their documentaries at home and at school. A research assistant worked individually with children to help clarify what each child wanted to represent about their everyday learning. Each child produced a documentary of around 5 minutes. In one school, the children presented their learning documentaries to staff, whānau, and 99 peers.

v. Stimulated recall interviews with the children, their parents, and wider family. These occurred in the children’s homes with the documentaries being used to prompt discussion about what and how children were learning informally and how understandings of learning had changed over the project for both children and parents.

vi. A Children’s Reference Advisory Group (CRAG) (n = 6) was established. Children from a different school were invited to participate to discuss aspects of the research findings with children (e.g. the conceptions of informal learning identified by the children) without breaching the confidentiality of those children who were participants in the research. The CRAG ensured the research had face validity for the children involved. Such groups have been used successfully in supporting researchers to work alongside children as co-researchers (e.g. Bourke & Loveridge, 2014; Lundy & McEvoy, 2011). They are argued to be a powerful means to facilitate student voice in research to ensure their meaningful participation while also building “capacity for children as researchers in a variety of settings” (Kellett, 2011, p. 209).

The second phase involved an ethnographic method working with teachers to understand how these processes contribute to learning and assessment in a school classroom context. Data collection proceeded at different rates in the three schools due to the ebb and flow of daily life in each school. In phase two, in particular, the research was responsive to the particular questions that each teacher was interested in investigating, and the data collection methods and timetables varied to accommodate these.

2.4 Data analysis

The data in phase one were analysed collaboratively by the research team. For example, for the phenomenographic interviews, individual transcripts were read and re-read to ascertain each child’s conceptions of informal learning and to collectively develop categories of description. For each child, two researchers independently coded the interview as reliability checks to ensure we were ‘seeing the same thing’.

In phase two, some data were analysed collaboratively by the research team and the teachers. For example, the structured and unstructured observations were discussed and analysed together and then the teachers decided what they would do next in their classrooms. Other data, such as the student survey or focus group interviews with teachers, were analysed by the research team.

3. Children’s conceptions of informal and everyday learning

Everyday informal learning includes all sorts of activities, with all sorts of people. We heard about: shopping with family members; looking after siblings; caring for pets; playing with siblings, cousins, friends; connecting to adults and constantly forming and re-forming with different whānau; riding bikes, learning to use skateboards, roller blading; cooking roti, making milkshakes and dips for chips; singing, dancing, kapa haka; putting nappies on a newborn sibling; dressing up siblings, pets, themselves; learning to put on make-up, creating ‘silly’ movie clips; outdoor games, rugby, soccer, netball, basketball; painting, drawing, sewing, gardening, playing canasta, caring for a rat, dog, cat, horse—even hotwiring a car. Learning was joyful but was at times about ways to deal with unbearably hard experiences: watching your father drown; learning your friend has died in a house fire. Learning could be tough, sad, and include ongoing grieving. A mosaic of learning emerged from these interviews, comprising whole pieces and fragments, facets that were near perfect and others that were flawed. Above all, there was a strong sense of learning having multiple dimensions and occurring within and between people, sometimes quiet and solitary and other times vibrant and social.

The collages were as individual as the children themselves.

Image 1: Examples of children’s collages of informal and everyday learning

The representations of learning that the children chose to collate on their paper do not make sense to an outsider at first glance. It was important to talk with the students to understand what they were representing. For example, two children can use the same representation but have entirely different meanings. Take the picture of a car. For one boy, it was because he was passionate about cars, and wanted to own one when he was older. For another child, the identical picture represented the child’s Aunty picking her up in her red car each weekend to take her out of town. It was the trip with Aunty she was trying to represent. A number of boys chose the same picture of modern art, which for them all represented graffiti. For one child he wanted to denote the act of graffiti, but for another boy it was what he learned about ‘design’. In a further example, one boy had a picture of a man who was playing cricket. He explained that he liked watching cricket with his father as his father travelled overseas a lot for his job and he did not get much time with him.

The children could talk about their learning in their lives outside of school in varied ways both explicitly (the child who used pipe-cleaners and plaited them, had learned plaiting from her sister who was a hairdresser and then was able to plait her younger sister’s hair), and implicitly (the child who chose just three pictures and then painted half his picture black and the other half blue). The teacher later explained to us that these colours represented gang affiliations.

Predictable forms of learning outside of school were represented (piano lessons, guitar lessons) as well as less predictable (crossword puzzles, maths, gardening). Locations or other means to access learning included visits to specific places (e.g. Mt. Bruce for the kiwis), internet (using YouTube clips to learn Minecraft), looking at photos, and learning to apply make-up by watching and being taught by an older sister.

3.1 The categories of description for informal and everyday learning

The results showed the variation of the phenomenon of informal learning with five categories of description for informal learning that ranged from least sophisticated (A) to most sophisticated or inclusive views (E) (see the summary in Figure 3).

Category A[2]

Category A was represented by children who knew they were a member of their family and friendship groups but did not connect these relationships to their learning. They engaged in activities because they were told to, and tended to learn things through listening or watching what was happening without understanding the meaning of an activity. They were yet to see a relationship between the activities they engaged in and who they were becoming, or their feelings. For example, one child talked about copying others to learn. She also described learning to sing by imitating a singer on the computer, and copying her brother. When asked about how she went about choosing what to learn, or learning by herself she was unclear on her strategy or purpose.

Category B

Category B was represented by children’s conceptions of informal learning as ways to fill in time, avoid being bored, and engaging in tasks for the ‘sake of doing them’ rather than for the sake of participating in their learning more broadly. At this stage they might copy or repeat games, ideas, or activities they are exposed to, but are not actively reflecting on these activities as learning or progressing in learning. Through the child’s play with friends, she participates in whatever presents itself. For example, a child saw biking as something to do, and learned new ways to bike (one-handed) when her mother suggested she take her hands off the bars. Through the mother’s prompt the child learned new ways to bike. This example shows also that, within this category, unintended learning can emerge from activities that are serendipitous.

Category C

In contrast to Category A where other people were not intentional sources of learning or sought out to support children ‘to learn’, Category C was represented by children who recognised that they needed others to learn. In this category, children expressed conceptions that they themselves have a role in thinking about the strategies they use as they learn ‘some thing’. For these children, the everyday activities they engage in had meaning for them. Within this category, children were engaging in an activity as a way of being with a valued other (e.g.

parent, sibling, peer, family member). They were beginning to understand the connections between what they were learning and their emotions. Given this more sophisticated and more inclusive conception of informal and everyday learning, Category C also shows how children’s learning contributed to their sense of identity. In this way, they were beginning to orient themselves towards what they wanted to do, where they wanted to head, and who they were becoming. An internal motivation could be discerned.

One child explained to the interviewer how he learned to go down a water slide leaning backwards with feet crossed over. He expressed how he needed others to help him learn something because others were telling him how to do this. What he is learning has meaning for him and he makes the connection between what he learned and his sense of pride. It also contributed to his sense of being someone who would tackle things that he felt scared of doing.

Category D

As the children became more confident in their learning outside of school they became more deliberate about approaching those people who they knew could further their understanding, or who could teach them a specific skill. The children who expressed conceptions of everyday learning within Category D linked these to risk-taking and not being afraid to fall or fail. In part, this may have been because they had a level of confidence that enabled them to view themselves as successful learners, rather than not being able to do something. They could see the difference between not performing a task, and learning to perform a task. The ability to ‘read’ emotions in themselves and others was integral to this category. One child explained how her visits to the local library with her father were both about being with a valued other and accessing reading material that she chose. Notably, she was not going because she had to, or because the father thought she ought to, but rather because she appreciated that her reading enabled her ‘to find out new things’.

Category E

The most sophisticated and inclusive category of description was illustrated by children’s conceptions of everyday informal learning that captured their learning in a broader context of home, community, and global living, where learning in a range of contexts had meaning and purpose, and where the child was both teacher and learner across generations. In one example, a child talked about her garden and learning to grow a range of plants. She could explain what she did (water plants), and why. In addition, she used this as a metaphor for people and place. She talked specifically about the native plant harakeke (flax) which has a specific purpose in weaving. She drew on tikanga Māori in which the harakeke (flax bush) is likened to the whānau (family) with the child in the centre, protected by the mātua (parents) and only the tūpuna (the grandparents), the outer older leaves, are harvested for use.

Figure 3: Categories of description of informal and everyday learning

Categories of description for informal and everyday learning

A. The child knows s/he is a member of the family and friendship group and engages in activities to comply with requests. The child reveals little understanding of activity meaning or purpose, or of her/ his role in the family or friendship group context. The child has yet to understand who s/he is across multiple contexts. The child has yet to see a relationship between activity and feelings.

B. The child knows how relationships work and her/his role in them and engages in activities to fill in time or avoid being bored. The child copies and repeats the activity s/he is learning to do without reflection. The child sees the activity might have meaning for her/him. The child recognises the activity produces a range of feelings.

C. The child knows that s/he needs others to learn and participates in activities to spend time with valued others. The child understands that the activity has meaning for her/him and others. The child intentionally thinks about how s/he practises in order to learn and orientates towards what s/he wants to learn. The child regulates her/his emotions during an activity in order to move from one activity state to another.

D. The child can see her/his role in helping to (make meaning) (create knowledge) with others. The child knows who to go to for particular learning and believes the learning will be useful for her/him in other settings. The child is prepared to take risks in order to learn something new and can see her/his role in helping to make meaning and create knowledge with others. The child understands others’ emotions as a result of undertaking an activity.

E. The child can choose the relations that are best for her/his/others’ learning and can appreciate the world as a complex place. The child improvises and is creative in her/his approach to learning and across multiple contexts. The child intentionally creates meaning for and with others. The child understands that s/he can influence emotions in others and has a sense of being able to regulate her/ his own and others’ emotions.

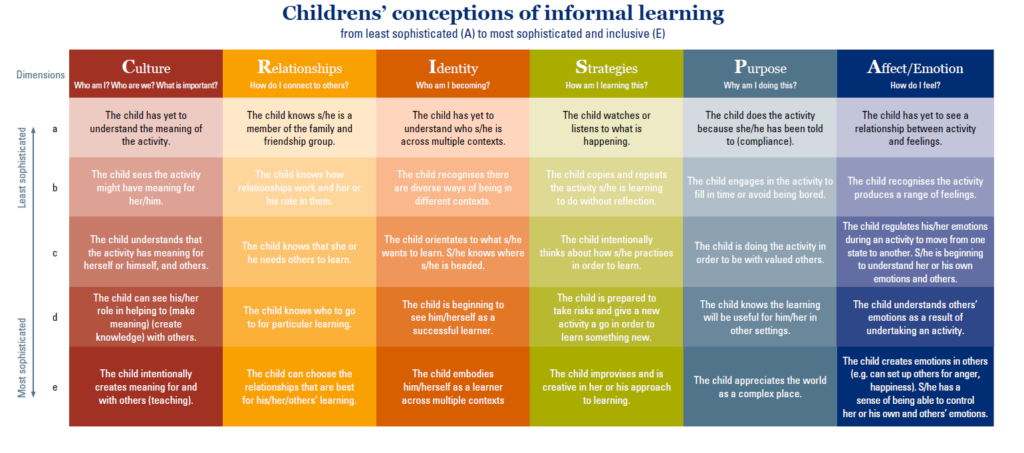

3.2 The six dimensions of informal and everyday learning: CRISPA

Our analysis revealed common dimensions of children’s everyday activities and settings that influenced how and why these children participated in the activities they chose to describe (see Figure 4).

Figure 4: The dimensions of children’s informal and everyday learning

Culture

Culture, referring to the home culture or the culture of a larger group affiliation such as ethnicity, was evident in the way some children spoke about their learning and how they experienced the meaning of activities in which they participated. For some children there was no apparent recognition that the meaning of activities or their participation was part of the ‘way we do things here’ whereas other children did have a sense that the activity meant something for their family or broader cultural group. More sophisticated conceptions of this dimension included seeing that they had a role in helping to make meaning or create knowledge with others. The most sophisticated expression of this dimension incorporated a sense of the child intentionally creating meaning for and with others, as they moved between learning themselves to teaching others.

Relationships

The importance of relationships for the children was evident in the way they chose to learn with, from, and about the people in their lives. As a starting point, children learn they are a member of a family or a friendship group and begin to understand how relationships work and their role within them. More sophisticated conceptions within this dimension included children recognising that they needed others to learn. Children had progressed to learning that individuals bring different skillsets, and knew who to go to in order to learn from specific activities out-of-school; for example, cooking, dancing, sports, and games. The most sophisticated conception within this dimension was that the child made intentional decisions in choosing who was best for their learning, and how to access this support. As a dimension of their learning, relationships were critical for all the children, and as they became more sophisticated in their understanding, they were able to use relationships in multiple and meaningful ways to support their informal learning.

Identity

Identity was clearly important to informal learning for every child, and tended to be emergent even among children with a least sophisticated conception of informal learning. For example, while a child might not yet have a good understanding of her/himself across their home, community, and learning contexts, they did recognise they were members of a family group. As children started to recognise the diverse ways of being across contexts, they were better able to make comparisons about their ‘self’ at home playing with siblings on the one hand, and their ‘self’ with peers on their skateboards on the other hand. While not incompatible, the separate ‘selves’ did mean children tended to separate their understanding of learning and did not orientate to the ‘bigger picture’ of understanding their identity as a learner. However, as the children began to orientate to what they wanted to learn, and where they were headed, they began to see themselves, individually as a successful learner, and could accommodate diverse contexts easily and with confidence. For children who developed an increasingly sophisticated conception of informal learning they embodied themselves as learners across multiple and complex contexts. Their identity as a learner was not determined by a single person, or activity, or external representation of their learning, but through their intentional participation as a learner.

Strategies

The strategies children used within their informal and everyday learning could be encapsulated in a common question “How am I learning?” For some children, merely listening to or watching what was happening might on the surface appear a passive strategy, but could also indicate a clear and considered approach (i.e. intentional learning) to their informal learning as a starting point. The next conception involved the child copying or repeating what they wanted to learn, although with little reflection as they engaged in their learning. A more sophisticated conception again was seen when the children intentionally participated using a strategy around practice and ‘trial and error’ in order to learn. For many children, informal learning meant spending hours honing a dance move, learning the words from popular songs, or working out a sports maneuver. All these activities evidenced intentional, repetitive, and strategic purpose. As the child grew in confidence, the strategy of taking risks in order to learn was more evident. Risk-taking as a strategy indicated that the child had an aspiration and belief s/he could ‘get there’ but that taking risks was important to move closer to their goals.

Purpose

The purpose of doing an activity was another dimension inherent to children’s accounts of their informal learning. For children with the least sophisticated conceptions of informal learning they engaged in activities because they had been told to or to fill in time and they did not recognise what they were doing as learning or having the potential for learning. Other children recognised that the purpose of them doing an activity, such as singing with their friends or their cousins, was so that they could spend time with other people they valued. More sophisticated conceptions of this dimension showed the child being aware that their learning would be useful for him or her in other settings. As they acquired more sophisticated conceptions of learning, children understood the worlds they moved in as complex and that there might be a range of purposes for participating in activities.

Affect/emotion

The way that children felt emotionally as they participated in activities was another important dimension for understanding informal learning. While some children did not articulate any relationship between doing an activity and their feelings, others were able to recognise that participating in certain activities made them feel scared, or proud, or happy. As children became more sophisticated in their understanding of the relationship between doing an activity and how they were feeling they began to be able to regulate their own emotions and understand the emotions of others who were undertaking activities. For children with the most sophisticated conceptions of learning this also included recognition of their capacity to prompt emotional responses in others. For example, a recognition that their engagement in activities made family members feel proud or connected or that they knew how to ‘push another child’s button’.

3.3 Examples of children and their informal learning

In this research we saw how children started to see learning ‘in a different way’ and ‘with new eyes’ during the process of their involvement. They could connect their out-of-school learning to a school environment, but in ways we had not expected. For example, the children drew on their experiences of learning and being challenged outside of school and related these to experiences in the school context. One child linked her discussion from making mistakes and having accidents in her roller blading, and making mistakes to learn in other contexts. ‘I’ve had a lot of accidents and I’ve had a lot of scars. In our cul de sac there’s a really bumpy and sharp road and then it goes really smooth.’ She later stated that ‘it’s not that I like learning from my mistakes but it’s good to learn from your mistakes … [to the teacher] I like learning by you showing me, because you’re an expert because you’re the teacher.’ On her participation in this research, the child reported that she ‘had learnt a lot of things but I don’t know how to explain. Like, I’ve learnt that learning outside of school is really good … you’re kind of learning more outside of school than you do in school. In school we learn the same thing every day, same activities.’

In another example, at Halloween, a train ride in the local botanical gardens enabled people to take a ride while ‘actors’ would dress up to scare people. Popular among children and young adults alike, the child included this experience in his documentary. ‘When we were going to the [park] to go on the Halloween train. It took us a while to go on the train because there was, like, millions of people there. Here is me and my cousin.’ Alongside the documentary, the child had inserted vivid pictures of himself and his cousins dressed up, with face paint depicting ghosts and ghouls. Some months later, when asked what he wanted the teacher to learn about his everyday learning he raised this experience specifically because, as he said, he was brave to go on the train. The Halloween train was particularly important for one child as he ‘wanted to get scared’. He linked this to learning that is scary, and said that he enjoyed learning with his older cousins ‘because it’s more fun, and I learn more from them’. Months later he reiterated that ‘Halloween helps me with bravery, being a brave person.’ He explains that by riding the Halloween train he learned to ‘never give up and take a challenge. I wanted to take a risk and take a challenge and see if it was actually scary …’ When connecting this experience to school he talked about athletics and when asked who was the learner he was becoming, he instantly replied ‘the brave one’. Taking risks and trying was important for this child. Later in the interview the one thing he wanted his teacher to know was that he was ‘brave’. When asked why, he explained that it was so the teachers would know that with difficult tasks ‘I am brave to give it a go … I’m not scared so it would help me because I wouldn’t be scared, I’d be brave . She would know that I’m not scared of anything so she doesn’t have to be worried; if there was a task and she would think I’m scared of it—I’m not.’

4. Guiding teacher action

While there was initial hesitation in seeing everyday activity as ‘learning’, the children and their families, and later their teachers, could appreciate that the concept of ‘learning’ beyond the school made sense and had value for them. For some families it came as a revelation that day-to-day activities such as chores, grocery shopping, and looking after younger siblings or the family pet could have a strong ‘learning’ component. As we worked with teachers in schools, the interest and motivation to know their learners was very apparent across all schools, but the forms this took varied. For some, the curriculum or assessment requirements served as the principal frame of reference to know the child and their learning. This meant that assessment practices tended to guide teacher understanding, rather than the wish to actively know the child and their learning more broadly.

Foregrounding student conceptions enabled teachers to know more about their students than they might have imagined. For example, in this study when the children presented their informal learning documentaries to their peers and teachers, one teacher responded with a surprised, ‘And I thought I knew you!’ to a child. By working with teachers to help them understand informal learning and ‘exposing’ them to how children think about their learning outside school, a catalyst for change in teacher thinking became evident. Teachers demonstrated great interest, excitement, and deliberation as they explored their practice in relation to the informal learning of the children in their everyday lives, and linked these explorations to the classroom context. However, this also led to frustration for some teachers when the imperatives of assessment for accountability purposes were seen to inhibit opportunities for new ways of thinking about assessment to encourage and support broader forms of learning. The Ako Manga process was a key component in supporting teachers to explore students’ conceptions of informal learning, and to play around with new forms of pedagogical practice that emerged.

4.1 Ako Manga process with teachers

Teachers were introduced to the CRISPA framework through in-service teacher PLD days within their own school contexts, and through a series of smaller face-to-face meetings as they worked with the framework in their classrooms. The CRISPA framework was used by the researchers, teacher researchers, and teachers as a tool to present and unpack the complexity of informal learning. It was primarily used by teachers to explore dimensions of learning that they might not typically have considered. Given the dimensions of CRISPA were integrated throughout the children’s conceptions of informal learning, a rubric diagram was introduced to the teachers first so they could: (i) appreciate the overall phenomenon of informal learning from a child’s point of view; and (ii) identify possibilities to support children toward more inclusive conceptions of informal learning.

One school had a full PLD teacher-only day prior to the start of the school year, on informal and everyday learning which started with exploring their own informal learning. The purpose of the collage activity was to help teachers to think about their everyday lives, interests, and learning outside of school and outside of being a ‘teacher’. In this way, we could then introduce the students’ conceptions of everyday learning without the frame of reference to which teachers might default.

Image 2: Collage development with teachers

4.2 Engaging with teachers around children’s conceptions of informal learning

The observations and subsequent discussions produced a rich data set. Teacher and child dialogue was recorded, and a timed account of classroom activity narrated weekly over a school term. The analysis of the observations and the type of questions used with teachers in the follow-up discussions depended on the teaching activity and what we observed. These included:

- I noticed you were … Tell me about that.

- I’m really interested in (explaining something observed) …

- How did you get that information?

- Why did you do that?

- What do you do when a child does not want to make mistakes? (after observing such a child)

- Why didn’t you think it worked for you today? (when a teacher described things going ‘wrong’ in her class)

- You had that young child doing … Why was this?

- I am interested in the relationships you have with your children and how this supports your teaching.

- Let’s talk about … [something observed]

Observable shifts in teachers’ pedagogical thinking and in teacher practice were identified. For example, in one school teachers initially focused on the relationship dimension of the CRISPA framework as it was seen as a strength by the teaching team and a place to build their own teaching capabilities. The teachers used their knowledge of individual children’s informal learning and their interests to inform their programme and planning. For instance, teachers chose specific text for children based on their out-of-school interests and activities, children were encouraged to learn about others’ interests, and share items they came across with their peers who might be interested. The classroom environment and tone encouraged children to share their lives and what was important from their own informal learning experiences. The addition of CRISPA initiated a shift in pedagogical thinking to incorporate children’s informal learning in a more explicit way (see Text box 1 below for teacher reflection).

At another school, a teacher actively used the CRISPA framework to guide her practice. Initially, the framework was used to see if teachers could ‘shift’ the child and their own teaching practice to the next stage. At each meeting with the researchers, the CRISPA framework was central to the discussions until the teacher commented that she was no longer trying to ‘fit’ the child or herself into ‘a box’ to tick. There had been subtle shifts in pedagogical thinking that translated to the teacher’s practice. The teacher had used her strengths in building relationships with both the children and their families and whānau and this became a central theme in the context of children’s learning in class. Informal learning had begun to take ‘centre stage’. One example of this was a girl who was learning martial arts. At school, she was supported by the teacher to make a ‘how-to’ video to share with the class, which prompted children to learn from her and also to make their own ‘how-to’ videos in regards their own interests. Children’s writing captured their informal learning. This made writing relevant and authentic for children and engaged them in an area of focus for the teacher. A further example was shown when a teacher had a conversation with a boy who had found it difficult to engage in learning at school. The teacher learned about the child’s weekend on his koro’s sheep farm, and this provided a pathway to engagement in learning at school. This boy was excited to share what he had learned in the shearing shed and could describe in detail what needed to happen (e.g. dagging a sheep). The teacher added value to this discussion with her own experiences of growing up on a farm, making it a shared experience. Informal learning connections were made that translated into classroom learning as well as strategies for learning.

Text box 1: Teacher reflection on the Ako Manga process

In our research we were not so interested in focusing on specific variations between participating teachers’ responses; rather, we were interested in exploring the experiences teachers had, how they responded to the CRISPA framework, and how it influenced their pedagogical practices. For example, when working with the teachers in the school context, teachers in one school asked the researchers to develop an online survey for their students, and teachers from another school asked to adopt this approach. In both these schools, teachers wanted to ascertain what their students thought about their learning outside school and how these young people were assessing their learning beyond the school gates, without direct teacher support. Subsequently, over 130 Year 5 (10-year-old) students in two schools completed a 22-item online survey developed by the research team. Student responses from one of the questions that asked students where they learned best (and they could choose up to three contexts), indicated that school (76%) and home (76%) were most frequently identified, followed by the outdoors (40%) and friends (35%).

Given that these students viewed home and school as the main places they learn ‘best’, yet only one of these sites explicitly assesses and acknowledges this learning (i.e. school), it was important to ask these learners whether teachers knew what they learned outside school. Nearly three-quarters of the students (70%) felt that teachers did not know what they learned outside school. The children were asked about a range of ways they learned outside school. They were asked to focus on a specific activity they had identified (e.g. learning to play a new card game; a new manoeuvre on their skateboard; a dance routine on YouTube) and then explore the question: How did you know you had learnt? Over half the students reported that they could ‘see’ or ‘feel’ their learning (i.e. they had arrived, achieved their goal, completed the task, or could see improvement). Therefore, without teacher or coach guidance, they were monitoring their own performance, knew what they needed to achieve further, and whether or not they were improving. Only a small percentage reported needing to be told by another person that they had learned, while others recognised they were on their way to learn but ‘I don’t know it yet’. Across the responses only 2% of the students did not know when they had learned. This gives further support to the view that outside of assessment protocols, young people recognise, assess, and actively engage in the assessment of their own learning.

Given that these results suggest children ‘know’ when they are learning outside school, and that it was possible for us to discern variations of sophistication in children’s ‘knowing’, such knowledge would clearly prove useful within a school-based context. These children reported that they either learned to do something (by achieving a goal, reaching a personal best), or could see themselves on a continuum of learning. When asked later in the questionnaire how they knew when they were successful, only 11% needed ‘someone’ to tell them. The majority knew they had arrived, noticed their own improvements, or associated their learning with positive emotional responses (e.g. happy, excited).

4.3 Parents, whānau, and their children’s informal and everyday learning

Parents, family, and whānau of the 12 children making learning documentaries were involved in the research through the children sharing clips, videos, photos, and games they were playing, being ‘coerced’ to perform in front of the iPad camera, and witnessing the development of learning documentaries (autobiographies). These experiences had the effect of influencing the way parents understood their child’s learning and viewed learning more broadly at home.

Parents, and sometimes other caregivers and whānau, were interviewed together with their child at two points during the process: (1) during the formation of the documentaries and to talk about learning at home; and (2) at the end of the project with the documentaries to view. On both occasions, the children were part of the process, and with one exception (where the interview took place at school), the rest were held in the home. The documentaries were watched and stopped at points where the parents or children wished to elaborate on what was being learned or the interviewer wished to seek greater understanding.

All of the parents indicated that they thought informal learning was important and most of them had valued informal learning prior to being involved in the project. One mother commented: ‘I see learning in every aspect of life. Everything we do you are learning … It is wonderful.’ Another parent indicated that she had known that the things her daughter was doing at home were important but she had not connected them with learning: ‘It has definitely changed the way I think … with all of this informal learning I understand more now that this is her learning. It all began to fall into place.’ It also helped her make connections with how she and her partner, as parents, were trying to teach her daughter about life. These teachings were ways of being and doing things as a family member that she and her partner had acquired as children within their own families but not recognised as learning.

Through their children being involved in the project, parents had expanded and deepened understandings of informal learning and its value. One parent commented: ‘You are well aware as parents that children learn things every day about life and living but it is not given the benefit that it deserves but we are very aware that outside of school you do lots of learning in different situations, it is very beneficial. So we fully support it and understand it.’

One parent noted that being involved in the project had challenged her understanding of learning at times and made her question what learning was. Another parent commented that it had reinforced what she had done as a parent in trying to help her child learn informally by building on his interests.

Parents were quick to recognise that their children had taken the lead in making their learning documentaries, making comments such as ‘She did the work herself—I was not involved’ and ‘[my son] had control’. One parent had struggled a little with what the child had included in the documentary but on reflection could see the value: ‘All the bit about friends show he is a very social person, but not as relevant to his informal learning as some of the other stuff, but then social learning is just as important as practical learning and intellectual learning.’

Parents were very positive about their child’s and their family’s involvement in the project and thought it would be a valuable experience for other families. One of the parents noted: ‘She has been changed by it. I just realised how creative she is and how much she has going on in her mind all the time.’ A child said, ‘I’m actually spending time with my family, and including them, and it’s actually a good thing for my family because normally we wouldn’t really be so interested, but all my family have been really interested in this so they’ve done stuff with me.’

5. Reflections on the project

The project values, aims, and design have generated powerful insights on children’s, their families’, and teachers’ appreciations of children’s everyday learning and its affordances within the interactional framework of the classroom. Nevertheless, these insights probably remain somewhat more provisional overall than we originally hoped for or would have liked to have gained after 3 years’ regular immersion in the field. In our experience, the principal reason for this is that everyday and classroom lives, despite their obviously predictable routines and patterns of living and learning, are also very complex and unpredictable. For example, several individuals and groups experienced extraordinary life challenges, which interrupted or ended their participation in the research. Others simply moved in and out of the school settings and communities in which the research was conducted, meaning that key relationships had continually to be built and rebuilt in order for the research momentum to be maintained.

On the basis of our research in these four low decile school communities, such complexities appear to be accommodated by those who learn and work in income poverty and material hardship school settings and communities as just the way life is. Nevertheless, the reality of schooling in challenging life contexts generates very real, material constraints on the completeness and the richness of the learnings that can be gathered from a study like this. The research partners and participants were invariably open and willing and, once they ‘got’ the research, enthusiastic to learn more about children’s learning. It is just that everyday life sometimes took over.

Put crudely, it is asking a lot of learners and teachers who are challenged every day to recreate the necessary conditions of learning, to also participate in research, however important that research may be. Based on our experience, it seems fair to say that teaching and learning, and therefore research about teaching and learning, simply take longer in income poverty and material hardship settings because of the impact of everyday and community life on social, pedagogical, and professional relations. This is not in any way to pathologise learning and teaching and family life (or learners, teachers, and caregivers) in these communities and settings. We were privileged over the course of the project to witness a wonderfully diverse range of learning and teaching events in children’s everyday and classroom lives. However, we want simply to call attention to the need to appreciate that everyday life does not stop at the school gate or the classroom door. Children’s classroom learning and relations are actively shaped by the learning strengths and challenges they bring to the classroom. Researchers and teachers working in partnership need to accommodate themselves to the ebb and flow of the classroom and to the antecedent and consequent effects of the classroom’s permeable boundaries with the everyday world of children’s lives. In that very educative sense, perhaps, the limitations of this study serve as a useful pointer to future studies of teaching and learning in income poverty and material hardship school communities.

6. Implications for research and practice

Over the course of 3 school years, this research project unpacked the complexity of informal and everyday learning, and showed the importance of foregrounding informal and everyday learning with and for children. Children enjoyed being part of this research and teachers learned they can actively involve their own students in their teacher inquiry work.

A direct implication for our own research is that children in culturally diverse families take on the roles that reflect the family, faith, culture, and community traditions they are expected to uphold as adults. We also noted that children living in complex, hybrid family structures are required to simultaneously negotiate a dizzying range of subject positions (being the eldest in one sibling group, the youngest in the next, and neither of these in a third) and relationships with significant adults (e.g. natural parent, step-parent, current parent’s partner) (Bourke, O’Neill, & Loveridge, 2018; O’Neill, Forster, MacIntyre, Rona, & Tu’ulaki Sekeni Tu’imana, 2017). All such variations of experience suggest that it is possible and natural for children and young people to learn to adopt and negotiate multiple embodied subject positions/identities in their lives outside the classroom and the school.

Their use of intent participation (e.g. Rogoff, 2012) was evident within the dimensions of informal learning. These children learned across generations and from unexpected sources, such as pets. As one 5-year-old child in the current study revealed to his teacher, ‘I learnt to dig from Garfield. Garfield is my cat.’

In our experience, research on informal and everyday learning brings bravery and fun back into learning conversations, and identity and belonging to learning debates. It contributes to a richer appreciation that culture, relationships, identity, strategy, purpose, affect/emotion (CRISPA) are inherent in the what and how we learn, every day. Teachers in our study played around with these ideas, and introduced new initiatives into their own classrooms, including taking the time to find out what their students experienced in their informal and everyday learning as children, how to make connections between learning as a child and learning as a student, and how to use the CRISPA framework to embody the student-child’s deep sense of self as a learner.

For our research team, the 12 key ‘takeaways’ for the project include community-based, intergenerational ako, the child as an agentic learner across contexts, whānau and teachers as partners with learners. These may be expressed as follows:

- Informal and everyday learning provides powerful contexts for children to understand themselves as learners, and develop identities as ‘successful learners’ in all aspects of their young lives.

- The role of families/whānau may be ‘underestimated’ in informal and everyday learning by parents themselves, and by schools.

- Parents need support to appreciate the informal learning that happens at home and in community, and its transferability.

- Important ‘others’ (family, peers, coaches, teachers, siblings) have an influence in learning through modelling, participating, and enabling new ways of thinking.

- Intergenerational reciprocal learning and teaching (ako) is evident—old to young, and young to old.

- Learners read context to determine how to engage in their learning.

- An individual’s identity as a learner is complex but is framed simplistically at school to meet the requirements of official policy.

- Children can be enabled to see their everyday learning conceptions and strategies as transferable learning strengths.

- YouTube is used ubiquitously by children for ‘how to’ learning—sharpening up the ability to learn specific skills and hone observational skills more generally.

- Teachers can enrich the possibilities of learning and assessment by explicitly incorporating the CRISPA framework into their planning, ako, and evaluation.

- Student voice and student–teacher partnership approaches have real potential to encourage pedagogical change, and become the learning.

- Student–staff partnerships in schools need to explore ‘learners’ as partners, for which the notion of ‘student’ is too limiting.

Footnotes

- We thank Mr Hone Morris who developed this whakataukī for the project, in collaboration with Dr Bevan Erueti. ↑

- The child’s voice is not present in these summaries. See Bourke, R., O’Neill, J., & Loveridge, J. (2018). Children’s conceptions of informal and everyday learning. Oxford Review of Education. DOI: 10.1080/03054985.2018.1450238↑

Dissemination from the TLRI project

Bourke, R., O’Neill, J., & Loveridge, J. (in preparation). Understanding the dimensions of informal and everyday learning: A CRISPA framework.

Bourke, R., O’Neill, J., & Loveridge, J. (2018). Children’s conceptions of informal and everyday learning. Oxford Review of Education. doi:1 0.1080/03054985.2018.1450238

Bourke, R., O’Neill, J., & Loveridge, J. (2018). What starts to happen to assessment when teachers learn about their children’s informal learning? Australian Educational Researcher, 45(1), 33–50. doi: 10.1007/s13384-018-0259-x

Bourke, R., Loveridge, J., O’Neill J., Erueti B., & Jamieson, A. (2017). A sociocultural analysis of the ethics of involving children in educational research. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 21(3), 259–271.

Bourke, R., O’Neill, J., & Loveridge, J. (26 March 2018). What happens to assessment when teachers learn about children’s informal learning? Ipu Kererū. Blog of the New Zealand Association for Research in Education https://nzareblog.wordpress.com/2018/03/26/assessment-informal-learning/

Conferences

Bourke, R., O’Neill, J., Loveridge, J., Erueti, B., & Jamieson, A. (2015, November). Children’s conceptions of informal and everyday learning. Paper presented at New Zealand Association for Research in Education (NZARE) conference, Te Whare Wānanga o Awānuiarangi, Whakatane.

Bourke, R., & Loveridge, J. (2016, November). The micropolitics of informal learning. Paper presented at the New Zealand Association for Research in Education (NZARE) conference, Victoria University of Wellington, Wellington.

Bourke, R. (2017, October). Informal and fearless learning: A child’s gaze on inclusive practices. Presentation at The Inclusive Education Summit, Adelaide, Australia.

Bourke, R., O’Neill, J., Loveridge, J., Dacre, M., & Wallace, J. (2017, November). Informal and everyday learning: Children’s voice(s), teacher practice and a framework for PLD. Three paper symposium presentation to New Zealand Association for Research in Education Conference 2017, Partnerships: From promise to practice, Mehemea ka moemoeā tātou, ka taea e tātou, Hamilton.

Teacher workshop 20 March 2018

Using student voice effectively in pedagogical partnership: (Re)presentation of student voice. Dissemination workshop for teachers across Mānawatu schools, including Professor Alison Cook-Sather providing two keynotes: (i) Tracing the evolution of student voice, and (ii) Promoting partnership in education through student voice.

References

Bourke, R., & Loveridge, J. (2014). Exploring informed consent and dissent through children’s participation in educational research. International Journal of Research & Method in Education, 37(2), 151–165.

Bourke, R., Loveridge, J., O’Neill J., Erueti B., & Jamieson, A. (2017). A sociocultural analysis of the ethics of involving children in educational research. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 21(3), 259–271.

Bourke, R., O’Neill, J., & Loveridge, J. (2018). What starts to happen to assessment when teachers learn about their children’s informal learning? Australian Educational Researcher, 45(1), 33–50. doi:10.1007/s13384-018-0259-x

Callanan, M., Cervantes, C., & Loomis, M. (2011). Informal learning. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Cognitive Science, 2(6), 646–655.

Engeström, Y. (2009). The future of activity theory: A rough draft. In A. Sannino., H. Daniels., & K. D. Gutiérrez (Eds.), Learning and expanding with activity theory (pp. 303–328). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Engeström, Y., Miettinen, R., & Punamaki, R. (Eds.). (1999). Perspectives on activity theory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Eraut, M. (2004). Informal learning in the workplace. Studies in Continuing Education, 26(2), 247–273. doi:10.1080/158037042000225245

Hedegaard, M. (2012). Analyzing children’s learning and development in everyday settings from a cultural-historical wholeness approach. Mind, Culture, and Activity, 19(2), 127–138.

Kellett, M. (2011). Empowering children and young people as researchers: Overcoming barriers and building capacity. Child Indicators Research, 4(2), 205–219.

Lee, J., Pihama, L., & Smith, L. (2012). Marae-ā-kura: Teaching, learning and living as Māori. Wellington: Teaching and Learning Research Initiative.

Lundy, L., & McEvoy, L. (2011). Children’s rights and research processes: Assisting children to (in)formed views. Childhood, 19(1), 129–144.

Marton, F. (1981). Phenomenography—describing conceptions of the world around us. Instructional Science 10, 177–200.

Marton, F. (1986). Phenomenography—a research approach investigating different understandings of reality. Journal of Thought, 21(2), 28–49.

Marton, F. (2014). Necessary conditions of learning. London: Routledge.

Marton, F., & Booth, S. (1997). Learning and awareness. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Marton, F., & Svensson, L. (1979). Conceptions of research in student learning. Higher Education, 8, 471–486.

O’Neill, J., Forster, M., MacIntyre, L., Rona, S., & Tu’ulaki Sekeni Tu’imana, L. (2017). Towards an ethic of cultural responsiveness in researching Māori and Tongan children’s learning in everyday settings. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 21(3), 286–298.

Rizvi, F. (2007). Lifelong learning: Beyond neo-liberal imaginary. In Philosophical perspectives on lifelong learning (pp. 114–130). Springer: Netherlands.

Rogoff, B. (2012). Fostering a new approach to understanding: Learning through intent community participation. LEARNing Landscapes, 5(2), 45–51.

Schugurensky, D. (2015). On informal learning, informal teaching and informal education: Addressing conceptual, methodological, institutional and pedagogical issues. In O. Mejiuni, P. Cranton, & O. Taiwo (Eds.), Measuring and analyzing informal learning in the digital age (pp. 18–36). PA: IGI Global, 2015.

Acknowledgements

We thank the many brave people involved in supporting and working within this project, all of whom shared a love of learning, a willingness to take risks, and a desire to push the boundaries of what it means ‘to learn’ and consequently the learning that we acknowledge, celebrate, and affirm.

Children, families, whānau

We thank the more than 125 children who participated in a collage art making activity to help us get started on our partnership research journey in early 2015, and those children and teachers who later followed in their footsteps. We thank the 36 children who were interviewed formally to help us arrive at our initial understanding of informal and everyday learning as a sociocultural phenomenon. We continue to be in awe of the 12 children who worked with us over 18 months as they explored their informal learning through digital technology and the production of learning autobiographies that they shared with their family, whānau, peers, teachers, and the researchers, in powerful ways. We thank the families who invited us into their homes to talk with them, learn from them, and to explore their child’s informal and everyday learning together.

Our multi-talented research rōpu

Claire Rainier (Research Assistant, 2015, working with children and young people)

Ella Bourke (Research Assistant, 2016, working with children and young people)

Sarika Rona (Research Assistant, 2016, working with children and young people)

Dave Cochrane (Videographer, 2016, providing digital autobiography support, and working with children and young people)

Amy Young (Research Assistant, 2016, working with children and young people)

Andrew Jamieson (Pasifika Cultural Advisor, 2015–17)

Bevan Erueti (Māori Cultural Advisor, 2015–17)

Nathan Matthews (Māori Cultural Advisor, 2014)

Rosie McEvoy (Business Support Officer, 2015–17)

Maria Dacre (Teacher Researcher, 2017)

Jami Wallace (Teacher Researcher, 2017)

This research was enabled through a partnership with the participating children across four schools, the principals and senior management teams, classroom teachers, and the children’s wider whānau. We thank the teachers who invited us into their classrooms, workgroups, and staffrooms to observe, discuss, enquire, share, and celebrate ako in action in diverse learning areas and spatial arrangements across 12 school terms. We especially acknowledge the teachers who ‘gave it a go’:

Somerset Crescent School: Mara Kean, Lyn Loveridge, and Clare McIlhatton

Central Normal School: Raewynne Hill and Maddy Speirs

Cloverlea School: Mary Burnett, Fiona Jensen, Lisa McFadzean, and Matt Barnacott

Te Kura o Takaro: Marilyn Miller

We acknowledge and thank

- The Teaching and Learning Research Initiative peer review committee for the award of this 3-year grant (2015–17)

- The New Zealand Council for Educational Research (NZCER) for its administration of the grant

- Sally Boyd, Senior Researcher, NZCER for her insightful, constructive feedback on all project milestone reports during the course of the project