Introduction

Although the practicum is generally accepted as a core element in teacher preparation programmes, the assessment of student teachers’ competence during practicums appears to be particularly problematic as making judgments about complex performances, such as teaching, is a sophisticated process. As with any form of assessment, judgments are made against some criterion or normative standard, and this judgment must ultimately involve some implicit or explicit understanding of what constitutes good teaching (Porter, Youngs, & Odden, 2001), which in itself is a contested construct.

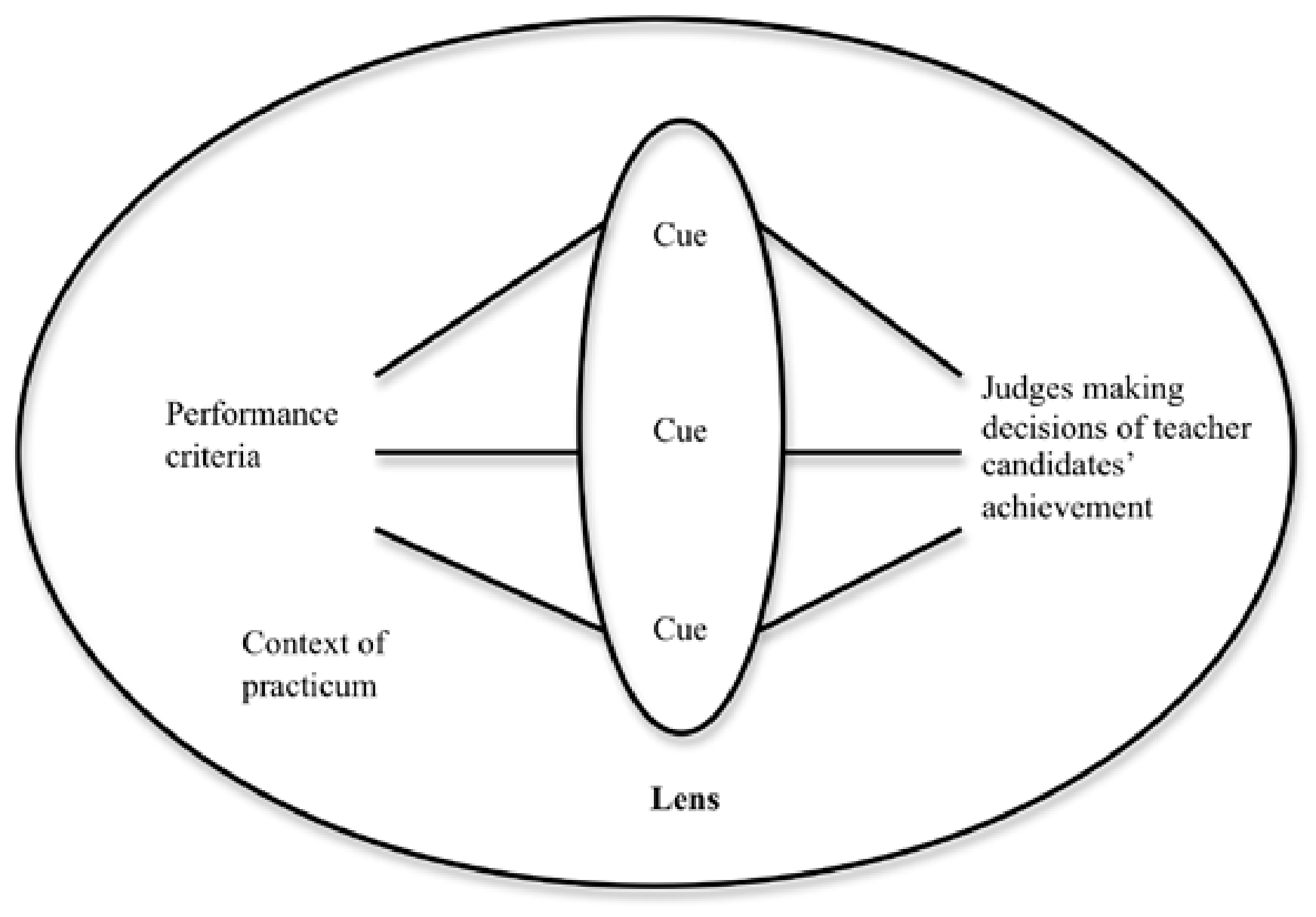

In this 2-year research project, Social Judgment Theory (Hammond, Rohrbaugh, Mumpower, & Adelman, 1977) was used to better understand judgments of “readiness to teach”. Social Judgment Theory suggests that some of the variation in people’s judgments comes from the context in which the judgments are made, and some comes from factors within the judges. This is important in settings such as the practicum, where the context plays a crucial role. Social Judgment Theory is interested in judges’ cues and policies. In the context of the practicum, cues are those aspects of a student teacher’s practice that the assessors pay attention to. The policies are the assessor’s beliefs, value systems and expectations that direct their attention to specific cues.

Social Judgment Theory uses a lens model to frame its research. This is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: The lens model in Social Judgment Theory

To tap into how teachers and education faculty academics make their decisions about prospective teachers, a series of tasks were developed that explored the question: What aspects of a student teacher’s practice are considered when judgments of his/her “readiness to teach” are made? To better understand the extent to which these judgments are authentic, trustworthy and evidence based, we also captured judgment-linked professional discussions in the schools, analysed documents and explored the different ways by which the practice of the student teachers was assessed in schools.

Key findings from the research

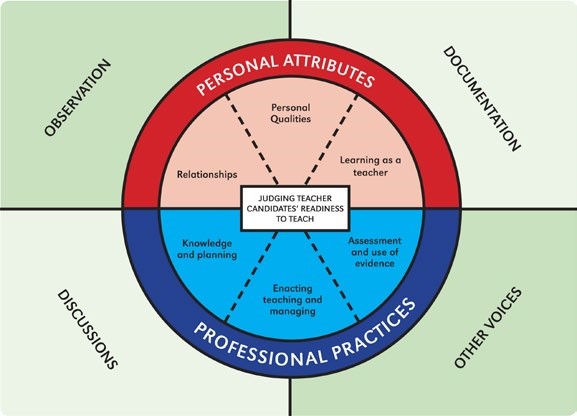

- Assessors of student teachers’ readiness to teach appeared to use six dimensions of effective practice to judge student teachers’ practice. Three dimensions are associated with personal attributes: “Learning as a teacher”, “Personal qualities/dispositions” and “Relationships”. Three dimensions are associated with professional practice: “Knowledge and planning”, “Enacting teaching and management” and “Assessment and use of evidence”. Across our study participants, both personal attributes and professional practice are considered in equal measure.

- Overall judgments of student teachers’ readiness to teach are likely to be holistic judgments. Judges seem to consider the six dimensions simultaneously and in relationship with each other. However, they prioritise the six agreed-upon dimensions idiosyncratically. Additionally, although there may be broad agreement about key areas for judging student teachers, individual judges vary in their views about what is “essential” and what can be “excused” or “fixed later”. This is often linked to the judges’ prior experience of student teachers, and of learning to teach themselves.

- Shared understandings of expectations of student teacher practice were likely to be built within the practicum context when:

- expectations for the student teachers were connected to Graduating Teacher Standards and the six identified dimensions of effective practice

- expectations were conveyed through documentation and professional development activities for student teachers and associate teachers, with the whole school considering what effective practice looks like

- responsibility for summative assessments of student teachers’ practice on practicum was shared across a number of teacher educators (university and school based) and a range of assessment strategies was used.

Major implications

- Judging readiness to teach is a process that has significant outcomes for the student teacher, the profession and pupil learning, so it needs to be trustworthy and dependable. It is a complicated task as teacher education is complex. Currently much of this decision making is idiosyncratic and not transparent to all concerned.

- There is a need to construct a view of effective student teacher practice that is shared by teacher educators and student teachers, and that conveys clear expectations. Teacher educators in both schools and universities would benefit from professional development focused on judging student teacher practice. Such professional development should include clarifying expectations, understanding available standards and criteria and developing awareness of the assumptions and experiences that underpin decision making.

- The processes and strategies of judging readiness to teach should be made clear to all involved in the judgment process, including, and especially, the student teachers.

The research

Background to the research

In New Zealand, as elsewhere, research has identified the critical role teachers play in children’s learning and achievement (e.g., Alton-Lee, 2003; Hattie, 2009). The challenge for initial teacher education is to prepare student teachers to work effectively in an increasingly complex and diverse environment, and to teach in more sophisticated ways to meet the demands inherent in The New Zealand Curriculum (Ministry of Education, 2007) and the National Standards (Ministry of Education, 2010). The practicum plays a critical role in initial teacher education programmes, providing authentic opportunities for student teachers, working alongside and supervised by experienced teachers, to gain understandings about the realities and complexities of teaching. The practicum is also a key site for determining student teacher suitability, or otherwise, for entry into the profession. The quality of the practicum will likely define the quality of teacher education (Zeichner, 1990).

However, the assessment of student teacher learning during a practicum is problematic. Problematic issues include the tension between different purposes of assessment, the impact of context on practice and defining what is “good practice” (Porter, Youngs, & Odden, 2001). In New Zealand, assessment of the New Zealand Teachers Council Graduating Teacher Standards (New Zealand Teachers Council, 2007) is inherently difficult, as the standards do not lend themselves to direct, objective judgment. Moreover, if standards are to impact positively on student teachers’ understanding of their practice, then the teachers and the appraisers must be part of a community of interpreters (Wiliam, 1996) who share norms of practice and agree on what constitutes appropriate evidence of good teaching.

There is limited research evidence from any source about how valid and reliable judgments are made about a student teacher’s level of achievement on practicum, or the ways in which school and university personnel make evidence-based, trustworthy judgments of student teachers’ readiness to teach. It is not clear on what basis New Zealand tertiary institutions and schools make judgments about students teachers’ achievement against the learning outcomes of the practicum or how issues to do with reliability and validity of judgments are addressed. Nor is it apparent how the practicum partner institutions make decisions regarding student teachers meeting the practice requirements of the Graduating Teacher Standards on their final practicum and hence being deemed competent to graduate and become beginning teachers. Therefore, this research therefore set out to (i) clarify the expectations of the assessors of student teacher practice and (ii) identify authentic and trustworthy practice-based assessment strategies that enable more dependable judgments of graduating students’ readiness to teach.

The research questions were:

- How is graduating student teachers’ readiness to teach ascertained by those who judge them in diverse practice settings?

- To what extent are those judgments authentic, trustworthy and evidence based?

Research context

The context for the study was the school-based assessment practices associated with the final-year practicum for students enrolled in a 3-year Bachelor of Education (Teaching) programme at The University of Auckland. In this programme the student teachers are in schools for 3 weeks at the start of Term 1 and for 7 weeks over the end of Term 2 and the beginning of Term 3. Teacher educators associated with the student teachers during practicums are university liaison lecturers from the Faculty of Education and the principals, adjunct lecturers and associate teachers in the school. ALs have particular responsibility for the practicum placement and work closely with the university liaison lecturers, the student teachers and their associate teachers.

Research design

To answer the research questions, and to enable substantive and robust findings, a multiple case study approach across four schools was used (Yin, 2009). Within the four case studies the eight university-based researchers (university researchers and university liaison lecturers) and eight teacher researchers (principals and adjunct lecturers) in the team:

- carried out both individual and focus group interviews about the cues and sources of evidence used by the people within the practicum setting

- captured individual and group discussions around assessment strategies used when making decisions about student teacher practice

- kept records of discussions between principals, adjunct lecturers, university liaison lecturers and associate teachers related to assessment decision making in order to capture cues and evidence used

- carried out document analysis in order to identify the cues that are used when teacher educators make judgments of a student teacher’s achievement of the practicum learning outcomes and their readiness to teach.

Three data-generating instruments were specifically designed for this study. Other research processes captured ongoing professional discussions and documentation associated with the practicum. The design of the study incorporated feedback of findings to the participants with opportunities for co-construction of future directions for the study. As 12 of the 16 team members were also participants in the study, this research can also be categorised as practitioner research (Fox, Martin, & Green, 2007).

Answering the first research question

Three specific instruments were designed to generate data to help us answer the first research question: How is graduating student teachers’ readiness to teach ascertained by those who judge them in diverse practice settings?

- Instrument 1 (20Questions) was designed to elicit the cues, evidence and policies used by the teacher educator assessors.

- Instrument 2 (Vignettes) was designed to further test the findings developed from the administration of Instrument 1.

- Instrument 3 (Online survey) was designed to provide individual feedback to teacher educators as to their prioritisation of professional practice dimensions when making judgments of student teachers’ readiness to teach.

Instrument 1: 20Question scenario

Instrument 1 was designed to capture the cues used and evidence sought by those who assess student teaching when they judge readiness to teach. Thirty participants, including the university liaison lecturers, principals, adjunct lecturers and associate teachers from four schools completed this task. The task involved an interview about a scenario (shown in Figure 2).

| I’d like you to imagine that you are talking to a colleague about a student teacher they have in their classroom. Your colleague has come to you for some advice about whether their student teacher should pass practicum. She is trying to decide if the student teacher is ready to teach.

I’d like you to think for a moment, and then tell me what questions you would ask your colleague to help you judge whether the student teacher is ready to teach. Initially I am going to ask you for 20 questions. Think about the areas that you feel are important in judging if someone is ready to be a teacher. What would you ask your colleague to find out about these areas? |

Figure 2: Scenario for 20Questions instrument

After posing 20 questions they were asked to choose the five most important questions that would be central to their decision and, for each of these questions, to outline what they would actually look for as evidence of whether the student teacher was practising as expected. After analysis of these data we identified six key dimensions on which student teachers are judged. Three of these dimensions are professional practice dimensions and three are personal attributes. These dimensions were used to develop instruments 2 and 3.

Instrument 2: Vignettes

Findings from the 20 question interview pointed to idiosyncratic prioritisation of the six agreed-upon dimensions. We wanted to test this further in order to triangulate these findings. Eighteen associate teachers from four schools undertook an hour-long interview that centred on their judgment of student teachers’ practice as presented in fictional vignettes. The vignettes were provided to the associates some days prior to the interview so they could form their views. The participants were asked to indicate if they would grade the “student teacher” as High Pass, Pass, Low Pass or Fail. The interviewer then asked the participants to explain their judgment, focusing on how they approached the task and what they paid the most attention to. This discussion was captured by audiotape.

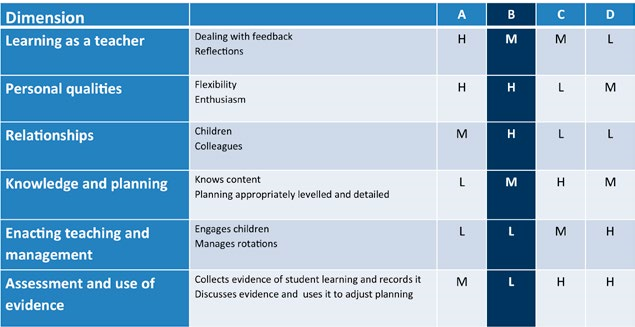

The four vignettes were developed around the dimensions identified from administration of the first instrument. The vignettes were constructed so the student teachers were described very positively, neutrally or negatively on each dimension. Two of the vignettes included statements that represented tendencies to high standards in professional practice but lower in personal attributes and the other two were high in personal attributes but lower in professional practice (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Framework for development of vignettes

Vignette B, containing statements that are high for personal attribute dimensions and low for professional practice dimensions, is shown in Figure 4.

| B has reflected on her practice when I have encouraged her to, and has kept a written journal of her reflections. She receives feedback politely, and has tried to implement some of my suggestions.

B is very flexible when she is teaching, responding to the usual classroom “hiccups” positively and providing direction for the children when things change. She is very enthusiastic about teaching, and conveys this to the children with an open and friendly manner. This has led to B establishing excellent relationships with the children in my class. She takes a genuine interest in them as people, and they respond to this. B has also made an impression on our staff, forming positive, professional relationships with the teachers across the school. B has completed planning for all her teaching. She has needed some support with including the right kind of detail, and with planning work for higher groups in reading and mathematics. She has adequate content knowledge for this level, but might struggle with mathematics at Year 7 and 8. Despite her positive relationships with students, B has struggled to maintain engagement during group lessons. She tends to become focused on one learner’s needs and to forget about the rest of the class. While she can enthuse the children, this enthusiasm needs to be linked to particular learning outcomes – much of B’s teaching was “busy work”, especially for the more able students, and was not worthwhile for my class. B has made little attempt to collect and record assessment information. In discussions about the level of her planning it became clear that she was unsure of the abilities and needs of the students, and was more focused on her “performance” as a teacher, rather than on the learning of the children. |

Figure 4: Example of a vignette

Instrument 3: Online survey

Instrument 3 is a survey instrument designed to provide individual feedback to teacher educators as to their prioritisation of professional practice dimensions when making judgments of student teachers’ readiness to teach. For instrument 3 we took the six identified dimensions of practice and, using fractional factorial design (Wu & Hamada, 2000), developed profiles that represented different patterns of achievement across the six dimensions (in terms of High, Medium and Low achievement) for 27 student teachers. Participant teachers (targeted n = 125) were asked to grade each student teacher on a 9 (high) to 1 (low) scale for overall achievement of the practicum. The survey instrument was presented to the teachers online. On completion of the survey, a multiple regression analysis is automatically computed allowing each teacher to immediately receive an individual report that indicates which one (or two) of the dimensions they prioritise when making judgments and how consistent they are as they make the judgments. The data was also captured by the system, allowing us as researchers to gather anonymous data on the responses of a large number of teachers. This data helped us to build a wider picture of the judgment practices of associate teachers.

Answering the second research question

Two main kinds of data collection were undertaken to generate data in relation to the second research question: To what extent are those judgments authentic, trustworthy and evidence based? These were:

- audiotaping and minute-taking to capture individual and group discussions around assessment strategies and cues and sources of evidence used when making decisions about student teacher practice

- document analysis of practicum-related materials in order to identify the cues/evidence and strategies that are used when teacher educators make judgments of a student teacher’s achievement of the practicum learning outcomes and their readiness to teach.

Analysis of data

Instrument 1 (20Questions scenario)

The qualitative data generated in this study were thematically coded (Braun & Clarke, 2006). Three of the university researchers and one member of the external advisory group initially carried out this analysis. Eleven dimensions were categorised through this process. The analysis was then taken back to the wider research team. We asked the team for their perspective on the codes, whether they seemed to fit with the questions people asked and whether they reflected the key messages about what participants saw as effective teaching given that 12 members of the research team had been participants in this phase of the study. Following this whole team discussion, one principal, two adjunct lecturers, two university liaison lecturers and three researchers from the wider team met to consider the validity of the codes. This meeting resulted in establishing six dimensions that incorporated the previous 11 categories, and had face validity for the school-based practitioners on the team.

Instrument 2 (Vignettes)

Analysis of data generated by the vignette study was carried out by two of the university researchers and a research assistant working under their guidance. Data were quantitatively analysed (the overall judgments) using simple frequency statistics and qualitatively analysed by theming of the explanations for the judgment (Braun & Clarke, 2006). NVivo was used to support this analysis.

Instrument 3 (Online survey)

The data entered via the online survey were automatically analysed using multiple regression statistics, with individual results reported directly to the participants. Collated data became available to the researchers for further statistical analysis.

Transcript, minutes and document analysis

Data generated during professional discussions were captured though audiotaping, and subsequent transcription, or through minute-taking. The scripts captured and documents collected were qualitatively analysed by using processes of theming outlined by Braun and Clarke (2006).

Results

20Questions/sources of evidence

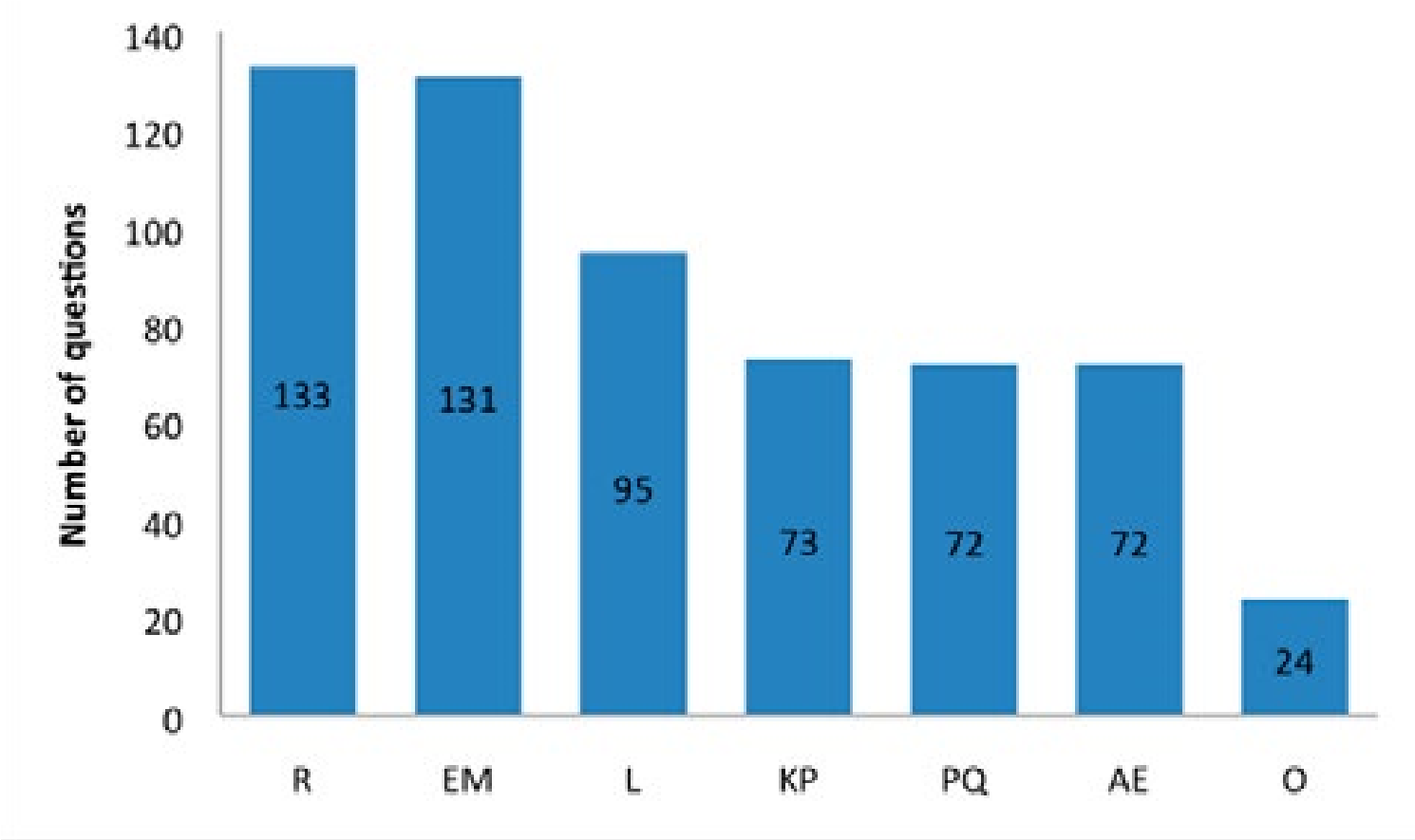

The six dimensions identified in the cue data were indicated above. Our first analysis also enabled us to capture the frequency with which each dimension occurred. 600 questions were captured.

| Key: R = Relationships; EM = Enacting teaching and management; L = Learning as a teacher; KP = Knowledge and planning; PQ = Personal qualities; AE = Assessment and use of evidence; O = Other) |

Figure 5: The number of questions of each type posed by participants in the 20Questions task

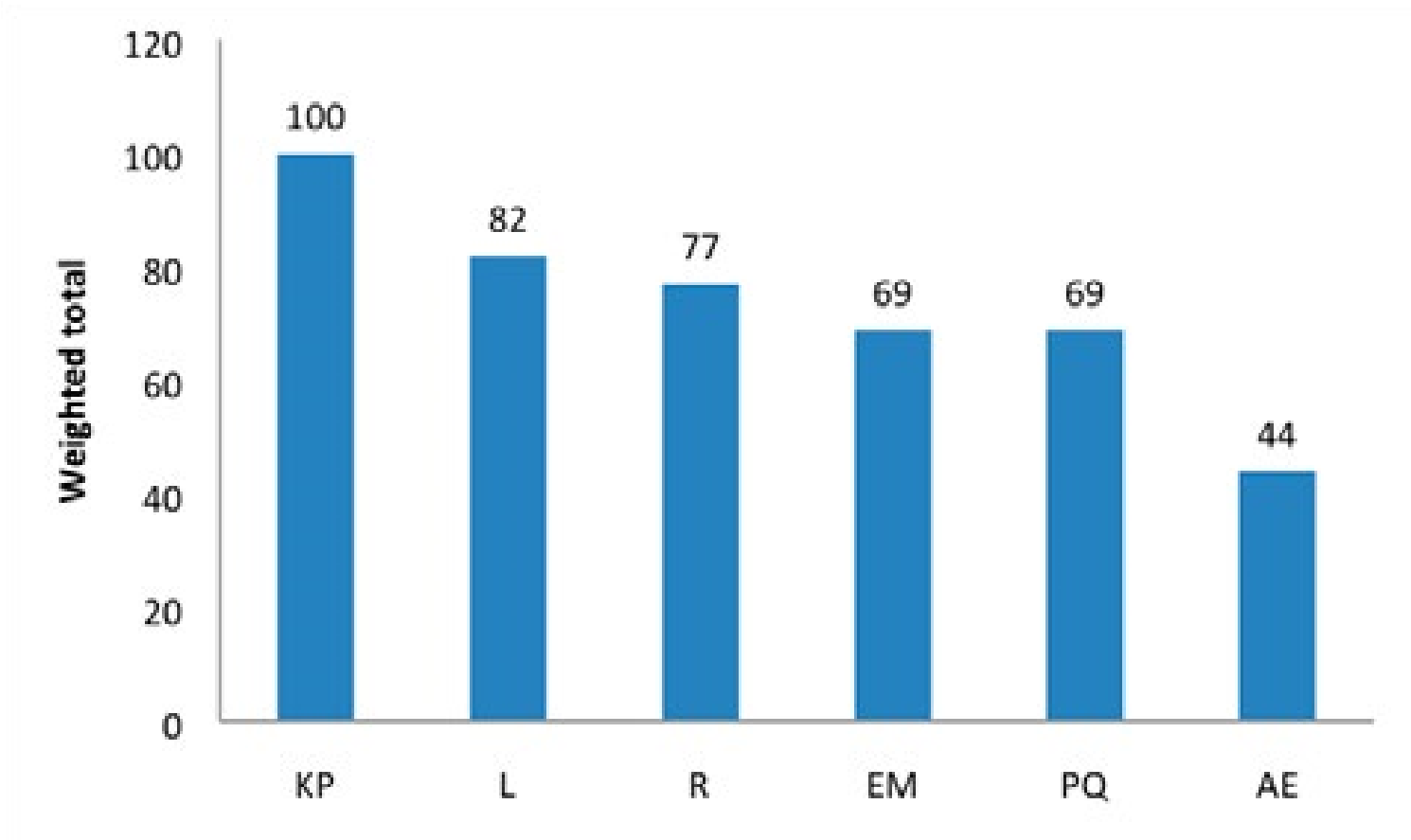

A second analysis of the “top five” questions identified by the participants gave us a picture of the relative importance, for these participants, of each dimension in judging readiness to teach.

Figure 6: The weighted total score for each dimension

Finally, our analysis of the evidence sources, and the relationship between the evidence and the dimension it was used to assess, gave us a picture of the richness of the judgment process. This richness is shown in Table 1.

| L | PQ | R | KP | EM | AE | Other | |

| Learning as a teacher | 77% | 4% | 1% | 8% | 6% | 1% | 2% |

| Personal qualities | 36% | 15% | 16% | 11% | 17% | 0% | 5% |

| Relationships | 2% | 5% | 57% | 7% | 20% | 9% | 0% |

| Knowledge and planning | 8% | 0% | 1% | 82% | 7% | 2% | 0% |

| Enacting teaching and management | 6% | 6% | 4% | 23% | 56% | 2% | 3% |

| Assessment and use of evidence | 4% | 2% | 0% | 43% | 4% | 45% | 2% |

| Other | 23% | 15% | 17% | 12% | 19% | 8% | 6% |

While the evidence sources for the questions were strongly linked to the cue dimension, evidence was also drawn from other dimensions for most questions. Evidence was drawn from observation, discussion, documentation and from comments from others (teachers, parents and wha¯nau, and children). A summary of the findings from instrument 1 is shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7: Summary of findings from the 20Questions instrument

Vignette study

The grades given by the associates to the four fictional student teachers described by the vignettes are shown in Table 2.

| A High in PQ and L Med in R and AE Low in KP and EM |

B High in PQ and R Med in L and KP Low in EM and AE |

C High in EM and AE Med in R and L Low in PQ and R |

D High in EM and AE Med in PQ and KP Low in L and R |

| HP = 1 P = 8 LP = 5 F = 4 |

HP = 0 P = 5 LP = 5 F = 8 |

HP = 4 P = 8 LP = 6 F = 0 |

HP = 1 P = 9 LP = 4 F = 4 |

| Key: R = Relationships; EM = Enacting teaching and management; L = Learning as a teacher; KP = Knowledge and planning; PQ = Personal qualities; AE = Assessment and use of evidence; O = Other) HP = High Pass; P = Pass; LP = Low Pass; F = Fail |

Overall, 7 High Pass, 29 Pass, 20 Low Pass and 16 Fail judgments were made. Vignettes B and C contrast the decisions made by the associate teachers. The story within Vignette B indicated high ratings for the personal attributes of “Personal qualities” and “Relationships” but low for the professional practice dimensions of “Enacting teaching and management” and “Assessment and use of evidence”. Vignette C was rated highly for the professional practice dimensions of “Knowledge and planning” and “Assessment and use of evidence” but low for the personal attributes of “Personal qualities” and “Relationships”. The pass grades for Vignette C whose story included comments about difficulties in establishing relationships appear to be in contrast to earlier findings in the larger study that indicated that the ability to establish and maintain relationships with children and colleagues was considered to be a very significant factor when determining student teacher practicum achievement.

The range of grades used by the individual associate teachers across the four vignettes was also variable. Two associate teachers used the full range from High Pass to Fail when making the judgments, ten ranged across three possible positions, four across two possible positions and two associate teachers indicated a Pass judgment across all four vignettes, perhaps in keeping with the university’s general reporting practice of indicating a “Pass/Achieved” or “Not achieved” against the learning outcomes for a practicum placement.

The associate teachers used various strategies when making the decisions. All identified the intended aspects of the vignettes that were strengths and weaknesses. Given the mix of strengths and weaknesses in each vignette, some started from the premise that the student teacher had failed the practicum then searched the vignette for instances that would challenge that decision. Others looked for the strengths first and then weighed these against identified weaknesses, reflecting on whether the positives were more important than the negatives. Others considered the vignettes against the learning outcomes for the final practicum of the teacher education programme or against the Graduating Teacher Standards.

The explanations made for the judgments also indicate variation in the associate teachers’ beliefs about aspects of teaching practice that can be learned once the student becomes a beginning teacher. A significant number of the associate teachers believed that content knowledge, management strategies and aspects of the use of evidence for planning for teaching can be learned at a later date. Others however were sufficiently concerned to fail a student if these aspects of practice were not well demonstrated during the practicum. Still others were prepared to pass a student even if these aspects were somewhat lacking if the student teacher was described as good at receiving and acting upon feedback.

Overall, the equivocal nature of making judgments was significant when these associate teachers considered student teachers’ readiness to teach. The results of this part of our study suggest that although there may be broad agreement about key areas for judging student teachers, individual judges vary in their views about what is “essential” and what can be “excused” or “fixed later”. Judgments of student teachers’ readiness to teach are likely to be holistic with consideration of relationships between different dimensions of practice.

Online survey

At the time of preparation of this report (31 March 2013) the multiple regression study has not generated sufficient collated data for us to analyse and report on. However, multiple regression analyses at the individual level have been shown to have professional learning value for individuals who have completed the task.

Professional discussion and document analysis

Data from across the four schools indicate that judgments of student teachers’ readiness to teach become more transparent and trustworthy when:

- actions are taken to increase the level of shared understandings of the expectations of student teacher practice across the student teachers, school-based teacher educators and university practicum supervisors

- student teachers are given multiple, ongoing and differently natured opportunities to demonstrate their professional capabilities

- multiple judges are involved in the decision making.

A number of different activities have been found to increase shared understandings. These include:

- group discussion among/between associate teachers and student teachers to unpack the practicum learning outcomes

- group consideration of the practicum learning outcomes set against the Graduating Teacher Standards statements and the six identified dimensions of teaching

- Sharing school-based expectations for the practicum with student teachers

- Using the 20Questions and vignette instruments to generate discussion within and between groups of teachers, student teachers and university supervisors.

Activities that support student teachers to identify and present their professional capabilities include:

- reflective evaluation of regular classroom practice with associates, practicum co-ordinators and university supervisors

- presentations by student teachers around one nominated Graduating Teacher Standard (both during and near completion of the practicum)

- practice job interviews with principals and senior staff

All four schools moved away from triadic assessment where the student teacher, associate teacher and university supervisor made practicum outcome decisions after “demonstration” lessons. Principals, practicum co-ordinators, associate teachers, university supervisors and the student teachers all became involved.

Limitations of the project

Judging readiness to teach is a decision with a significant moral and ethical dimension, and it is embedded in long-established and complex processes and settings. We did not delve into these, and thus this study addresses only a part of the whole decision-making enterprise. Although the context of the judgment is important for Social Judgment Theory, as a psychological theory it does not see the context in sociocultural terms. As a result, issues of equity and power relationships have not been explored in this phase of our work. Our results need to be considered alongside a critical view of the practicum and its assessment.

In addition, this study has been carried out in one university and four primary schools associated with the university in student teacher education. It makes no attempt to consider judgment making about student teachers in the early childhood or secondary teacher education contexts with their different contextual practices, nor across different universities with different practicum policies and processes. Also, these four schools were involved in a close partnership with the university and may not be typical of other schools. Some of the findings of this study may not have been possible within other types of university–school relationship.

Conclusion

Using Social Judgment Theory has helped us to build a picture of teacher educators’ judgment-making about student teachers’ readiness to teach. We have shown that making such judgments is a complex and integrated process. Although we have reached a high level of agreement regarding which aspects of a student teachers’ practice are required before graduation, the prioritisation of these is undoubtedly rather idiosyncratic. Overall judgements of student teachers’ readiness to teach are likely to be holistic judgments with consideration of relationships between different dimensions of practice. We have also identified the processes associate teachers engage in to make decisions about readiness to teach. Further study is needed around building shared understandings between associate teachers, student teachers and education faculty academics in this problematic area of initial teacher education.

Some (of the many!) ongoing questions for us to consider include: We have identified the dimensions that the participating judges thought were critical, but what dimensions of a teacher candidate’s practice are identifiable as making a positive difference to student learning? How might our growing knowledge of judgment-making processes help the assessors (often triads of student teacher, university academic and associate teacher) make required final summative decisions at the conclusion of a practicum placement? How can we build greater transparency into the assessment of student teacher practice? Do the student teachers know what is required of them? How can we develop shared understandings of what we are looking for? Can we reduce disagreement or do we cope constructively with it; how can we use dissensus productively? How might we educate judges?

References

Alton-Lee, A. (2003). Quality teaching for diverse students in schooling: Best Evidence Synthesis. Wellington: Ministry of Education.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3, 77–101. Fox, M., Martin, P., & Green, G. (2007). Doing practitioner research. London: Sage.

Hattie, J. (2009). Visible learning. London: Routledge.

Hammond, K., Rohrbaugh, J., Mumpower, J., & Adelman, L. (1977). Social judgement theory: Applications in policy formation. In M. Kaplan & S. Schwartz (Eds.), Human judgment and decision processes in applied settings (pp. 1–29). New York: Academic Press.

Ministry of Education (2007). The New Zealand Curriculum. Wellington: Learning Media.

Ministry of Education. (2010). National Standards. Retrieved 10 April 2010, from http://nzcurriculum.tki.org.nz/National-Standards New Zealand Teachers Council. (2007). The Graduating Teacher Standards. Wellington: New Zealand Teachers Council.

Porter, A. C., Youngs, P., & Odden, A. (2001). Advances in teacher assessments and their uses. In V. Richardson (Ed.), Handbook of research on teaching (4th ed., pp. 259–297). Washington, DC: American Educational Research Association.

Wiliam, D. (1996). Meanings and consequences in standard setting. Assessment in Education, 3, 287–307.

Wu, J., & Hamada, M. (2000). Experiments: Planning, analysis, and parameter design optimisation. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Yin, R. (2009). Case study research: Design and Methods (4 ed.). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Zeichner, K. (1990). Changing directions in the practicum: Looking ahead in the 1990s. Journal of Education for Teaching, 16(2), 105–132.