Introduction

Ko te kaupapa tonu, ko te whakatupu i te mahara o te hirikapo kia tiu ai ki te muri, arā, kia puta he whakaaro i pokepokengia nō roto tonu i ngā whakahekenga kāwai o ngā tūpuna o te tamaiti, kua maranga te wā e kaumātua haere ana te tamaiti, ngōna kanohi kua huaki, ngōna taringa kua pīkari, ngā whakaaro kua korikori, tōna wairua hīkaka kua ngawhā, ngērā kaupapa katoa o te tamaiti i taua wā o te tupu. Mā tēnei kōrero hoki hei kawe te taonga o te rongo hirikapo, arā, ngā whakaaro, ngā mahara, nāna ko te waha, nā te waha ko te kupu kōrero e makere iho ai i te ārero tarapepe. Heoi anō he tohutohu anō kei roto e kī ana, manaakingia ngā kai o te hirikapo o te tamaiti, he taonga. Ki te kore e tika te manaakingia e ngā mātua, tērā te wā ka ātitirauhea i te puāwaitanga o te rau. Ngērā kaupapa katoa. (Haki Tuaupiki, 2013)

This project grew out of the desire of a kōhanga and a kura—Te Kōhanga Reo o Ngā Kuaka and Tōku Māpihi Maurea Kura Kaupapa Māori respectively—to enhance transitions between their two sites for tamariki and whānau. Although visits to Tōku Māpihi Maurea before beginning at the kura were available for Ngā Kuaka tamariki on acceptance for enrolment, the instigators of this project believed a more formal transition programme would be beneficial to tamariki and their whānau. The kōhanga and kura were interested in tamariki and whānau experiencing a more effective transition across the two environments and the learning and curriculum in those respective sites.

The kōhanga and kura approached researchers at the University of Waikato Te Kura Toi Tangata Faculty of Education with the research question below and together we developed the proposal. From the outset the project was collaborative, cross-sector, and involved researchers from the kōhanga, the kura and the university.

The research question

The overarching research question for this project was:

1. Pehea rā te āhuatanga me te kounga o ngā whakawhitinga mai i te kōhanga ki te kura mō ngā tamariki, whānau, kaiako me te hapori?

What do effective transitions from kōhanga to kura look like, feel like, and sound like, for tamariki, whānau, kaiako and the community?

Associated research questions were:

- How does the collaborative kaupapa of the akoranga whakawhiti (transition programme) integrate kura wahanga ako in ways that foster children’s emerging understandings?

- What opportunities are given to tamariki to take responsibility for their own learning and assessment in the akoranga whakawhiti?

- What roles do parents, wider whānau and kaiako have in the transition journey?

- In what ways does the akoranga whakawhiti support children’s learning and development by building on children’s existing working theories and interests?

The significance of the study to kōhanga reo and kura

In Aotearoa New Zealand there is an explicit policy and practice focus on improving Māori educational transitions. Ka Hikitia Managing for Success: The Māori Education Strategy 2008–2012 (Ministry of Education, 2009) identifies “building strong foundations for learning early in the system and at key transition points as a prerequisite for further education and qualifications” (p. 11). Ka Hikitia Accelerating Success: The Māori Education

Strategy 2013–2017 focuses on “supporting successful transitions across the educational journey of Māori students” (Ministry of Education, 2013, p. 24). The 2013–2017 strategy sets out actions to support successful transitions for five focus areas, which include a focus on (a) Māori language in education, (b) early learning, and (c) primary education (Ministry of Education, 2013). While this strategy emphasises conventional academic outcomes and qualifications, it also calls attention to the importance of developing “a strong sense of belonging” along with the importance of supporting identity, language, and culture for successful education transitions (p. 24). Goals identified for early childhood and primary schooling under the early learning focus include Māori parents and families accessing their choice of high quality, Māori medium education.

Transition, alongside autonomy and te reo Māori, has been identified as a critical issue in Māori medium education (Bright, Barnes, & Hutchings, 2013, 2015; Hohepa & Paki, 2017; Hutchings, Barnes, Taupo, & Bright, 2012; Skerrett, 2010). When this project began in 2014, only 49 percent of kōhanga reo tamariki transitioned to Māori medium school contexts nationally (Ministry of Education, 2016). Transition is of major significance to both kōhanga and kura. Particular and unique characteristics of transition are located within whānau aspirations pertaining to te reo Māori, tikanga Māori, and mātauranga Maori, which led to the initiation of the first kohanga in 1981. The first kura kaupapa Māori sites were developed in the mid-1980s out of kōhanga whānau desires for their tamariki to experience ongoing kaupapa Māori education through te reo Māori. In this sense the kura whānau and kōhanga whānau were (and often still are) one and the same, and transition can be understood as relatively seamless. Arguably it is better understood more broadly as continuity of a shared kaupapa and vision encompassing tamariki, whānau and hapori (community) than more narrowly in terms of continuity of learning of tamariki.

There have been a number of changes since the early development of kōhanga reo and kura kaupapa Māori which can affect transitions today. These include the development of the early childhood curriculum document Te Whāriki (Ministry of Education, 1996) and the kura curriculum document Te Marautanga o Aotearoa (Ministry of Education, 2008).1 However, there is relatively little evidence about the degree of alignment between Te Whāriki and Te Marautanga o Aotearoa. We were interested in exploring connections between these two curricula that went beyond a focus on transition between the two to looking at the possibilities of an innovative blend of curriculum that supports kaupapa Māori education across kōhanga and kura.

Methodology

An action research approach we refer to as “te takarangi” was taken within a kaupapa Māori methodology (L. Smith, 2012). The foundations of kaupapa Māori as theory and as research can be traced to Māoriinitiated developments, in particular kōhanga reo and kura kaupapa Māori (Pihama, 2010). In keeping with kaupapa Māori approaches, the project was initiated by the kōhanga and kura and they were closely involved in designing and implementing the research. Fundamental elements of kaupapa Māori include the validity and legitimacy of mātauranga Māori, tikanga Māori, and te reo Māori. These helped to provide appropriate touchstones for the analysis of the data collected and the presentation of findings. The findings were of direct benefit to the kōhanga and kura kaiako researchers, whānau, and tamariki involved, and to the kōhanga and kura. The findings also have potential to support and benefit kōhanga reo, kura kaupapa Māori, and Māori medium schooling more generally.

An action research approach in education is seen to help cut across the so-called theory–practice divide (Carr & Kemmis, 1986). The approach helped to reinforce the position of the kaiako researchers as reflective and reflexive practitioners who not only provided theory with concrete form and structure in their planning and teaching but also theorised about and from their planning and teaching practice, alongside other members of the research team. Action research is often described as involving a spiral or cycle of planning, action, monitoring and reflection. McNiff (1988) goes further to describe action research as more often a process of “spirals on spirals” as aspects or findings may emerge that result in an exploration down a path that was not initially anticipated. The term “te takarangi”,2 as applied to our action research, captures the notion of spirals on spirals for our project.

A takarangi is a three-dimensional (at least) carved form, which means that there will always be aspects that remain unseen, yet to be discovered. The project also drew on te hurihanga whakaako pakirehua me te waihanga mātauranga (the inquiry learning and knowledge creation cycle)3 (Ministry of Education, 2008, p. 16). The cycle helped to reinforce the importance of not only kaiako and tumuaki but also whānau and iwi as key to answering (and asking) questions related to student learning.

A takarangi is a three-dimensional (at least) carved form, which means that there will always be aspects that remain unseen, yet to be discovered. The project also drew on te hurihanga whakaako pakirehua me te waihanga mātauranga (the inquiry learning and knowledge creation cycle)3 (Ministry of Education, 2008, p. 16). The cycle helped to reinforce the importance of not only kaiako and tumuaki but also whānau and iwi as key to answering (and asking) questions related to student learning.

The two settings most directly involved in the project were Tōku Whakakai Marihi, which houses the kōhanga programme for the tuakana (elder children) and Te Aroha, the new entrant classroom at the kura. Parents of tamariki in these two settings were provided with information about the project and asked for their consent to the participation of their tamariki and whānau. Tamariki in the two settings were also provided with information, and asked for their consent. Qualitative methods were used to gather data to explore the above research question. Data collected included: mātakitaki (observations); uiuinga (interviews); whakawhiti kōrero (conversations); notes and recordings from hui rangahau (research meetings); kaiako notes and journaling; photographs and video recordings; school planning documents; assessment records; and samples of tamariki work (including writing, drawing, constructions, performances, and presentations). The nature of the project resulted in data collected in identifiable phases, described below.

Baseline phase: Māori medium transition landscape in Hamilton

The project began by re-presenting the project to Te Kōhanga Reo o Ngā Kuaka and Tōku Māpihi Maurea Kura Kaupapa Māori whānau at whānau and board of trustees hui to reaffirm their support. We then met with chairs of the Hamilton kōhanga purapura (regional cluster) and attended a Hamilton purapura hui to discuss the project with other local kōhanga. Details about the project were also shared at a hui of Waikato kura and information was gathered from five kura to provide some baseline understandings about Māori medium transitions in the Hamilton area. Information indicated a wide range of Māori transition realities and strategies. For example:

- While ideally kura expected tamariki to come from kōhanga or Māori medium early childhood education settings, in reality there were significant differences in where new entrant tamariki came from, ranging from a founding kōhanga to a number of neighbourhood kōhanga through to local, largely English-medium early childhood centres.

- Not all kura held te reo Māori expectations of enrolling tamariki, their whānau, or their homes.

- There were large differences in numbers of new entrants expected to enrol at each kura in a given year, ranging from none to 20.

- Pre-entry experiences could range from three 1-hour-long visits before starting kura to tamariki joining the new entrant classroom programme for three mornings a week for up to a month.

Phase 1

The aims of Phase 1 were to ensure shared understandings across kura and kōhanga whānau about the project and to develop shared knowledge across the research team about the kōhanga and kura settings directly involved in the project.

Data gathering activities in this phase involved:

- hui with the kōhanga and the kura whānau

- observations in the Tōku Whakakai Marihi and Te Aroha settings

- kaiako researchers journaling observations

- uiuinga and hui with kaiako teaching in the Tōku Whakakai Marihi and Te Aroha settings

- hui rangahau.

Phase 2

Phase 2, in effect, spanned the entire project. In this phase, information was gathered about parents’ and tamariki’ views and experiences of moving from the kōhanga to the kura.

Data gathering in this phase included:

- uiuinga with parents of tamariki in the process of moving from kōhanga to kura

- whakawhiti kōrero with tamariki before and after moving from kōhanga to kura

- observations of pōwhiri and whakatau (official welcome) for tamariki and whānau moving from kōhanga to kura

- observations and information sharing at hui held for parents and whānau of tamariki moving from kōhanga to kura

- observations during formal kura visits of tamariki and parents/whānau members before the tamariki started kura.

In 2015, during phase 2, some parents and whānau at the kōhanga became involved in a contract that worked with early childhood centres and kōhanga across Hamilton. The contract provided practical advice about transition, along with resources that could be used in the home.

Phase 3

Phase 3 focused on collaborative planning and teaching that developed out of knowledge and understandings gained from Phase 1 and as they emerged from Phase 2. We also investigated the development of shared knowledge and understandings about the curriculum documents Te Whāriki and Te Marautanga o Aotearoa. Kaiako researchers collaborated to develop cross-curricular and cross-context teaching and learning programmes that were kaupapa driven, culturally informed, and culturally centered.

Data gathering in this phase included:

- document analysis

- written notes, Google docs, and records from collaborative kōhanga–kura curriculum planning activities

- kaupapa/unit plans

- tamariki work samples

- Te Whatu Pōkeka (kaupapa Māori assessment for learning exemplars), pakiwaitara (learning narratives) on the kōhanga Educa site (Educa is password-protected online software for early learning centres and programmes)

- observations of collaborative curriculum planning

- observations of parallel and of collaborative teaching and learning activities

- whakawhiti kōrero with kaiako and tumuaki

- hui rangahau.

Findings

Findings are framed under significant themes that help to illuminate experiences of tamariki, whānau, and kaiako moving from the kōhanga to the kura. The themes can be seen weaving through all the phases. We present descriptions of each theme along with examples to provide insights into how transition in Māori medium might be strengthened.

The project itself was initially conceived, planned, and developed as a project centring on transition. What we found, however, is that effective transition is positioned as much as a tool (Dunlop, 2017) as it is a central purpose in the movement of tamariki and whānau from the kōhanga to the kura. Successful transition between the kōhanga and the kura, and by implication between Māori medium early childhood settings and Māori medium school settings more generally, is a fundamental tool for the success of Māori medium schooling as a critical supportive site for Māori language regeneration.

Kia mau ki te kaupapa

The importance of transition has been conceptualised in various ways such as readiness (Wesley & Buysse, 2003), border crossings (Peters, 2004), and continuity of learning (Education Review Office, 2015). Transition from a kōhanga to a kura might be better understood as moving within kaupapa Māori borders rather than as moving across borders. This is often expressed in kaupapa Māori settings as “Kia mau ki te kaupapa” or “staying on the kaupapa”. A significant feature of the project was ensuring individual tamariki experienced a level of continuity of kaupapa, as well as continuity of their learning, as they moved from the kōhanga to the kura.

It was not unusual for parents to describe their commitment to the kaupapa as being more than wanting and arranging for their tamariki to go from kōhanga to kura. Some reflected on how that commitment had even preceded the birth of their tamariki. Parents viewed moving between kōhanga to kura as a normal, taken-forgranted expectation for themselves and their tamariki, as expressed in the following:

| Kāore anō kia whai tamariki … I roa e hiahia ana kia tuku i āku tamariki kāore anō kia whānau mai. (Mother) | I hadn’t even started having tamariki yet … but already wanted them to send them [to kōhanga and kura], even though they weren’t born yet. |

I’ve had a long relationship with Tōku Mapihi [before becoming a parent] … I helped out in the classes and ran sports programmes … There’s a huge amount of familiarity between the kura kids and my kids who are in kōhanga. [Daughter now at kura] would say, “when am I going to the kura?” it was normal to her to transition over to the kura. (Father)

Commitment to the kaupapa can now span several generations of whānau; for example, as described by one mother who stated that her tamariki went from the kōhanga to the kura just as she had before them:

| Nā te mea, whakapau kaha tōku whāea, ngōku whāea, me kī me ngōku pakeke ki te whakatū i ngaua wāhi e rua, kei reira tonu tō mātou whānau, e tautoko ana. (Mother) | Because of the energy that my mother, my aunties and my adult family members had expended in setting up those two places, our family is still there, supporting. |

One of the associated research questions asked “What roles do parents, wider whānau and kaiako have in the transition journey?” What is obvious is that for this kōhanga and kura, “transition” of parents and whānau alongside their tamariki assists in the continuity of a shared kaupapa. By ensuring that tamariki move from kōhanga to kura, parents, wider whānau, and kaiako play pivotal roles of enactment: the enactment of ongoing commitment to and active support of the regeneration of te reo Māori, tikanga Māori and mātauranga Māori, as well as to Māori medium education pathways.

Kia whakawhanaunga

The importance of strengthening and building on whanaungatanga (relationships, sense of family and belonging) to effective transitions between kōhanga and kura was evident from the outset of the project. The meanings of whanaungatanga are generated in contexts of action, and include relationships developed through shared experiences of meeting, of working together, and of undertaking interconnected roles and responsibilities (Bishop, Ladwig, & Berryman, 2014; G. Smith, 1995). Irrespective of context and participants, whanaungatanga encompasses value processes that involve not only relational and social but also spiritual dimensions (McNatty & Roa, 2002). Pōwhiri provides a significant context for its enactment of whanaungatanga across Ngā Kuaka Kōhanga Reo and Tōku Māpihi Maurea Kura Kaupapa Māori.

Pōwhiri

Pōwhiri (welcoming ceremonies) are essential for building new and reinforcing existing relationships between groups of people (Bishop et al., 2014). They are an integral part of moving from Ngā Kuaka to Tōku Māpihi Maurea. Pōwhiri or mihi whakatau were held for tamariki and their whānau before their formal transition visits to Te Aroha classroom began. Parents and whānau were accompanied by kōhanga kaiako and teina and passed over as taonga, treasures, into the care of the kura. Parents described pōwhiri as invaluable, they provided a cultural assurance that tamariki would continue to be safe, loved and nurtured when they moved to the kura. Pōwhiri also reinforced the kōhanga and kura relationships with mana whenua (iwi holding tribal authority over the region) and provided tamariki with rich opportunities for cultural learning in real-life meaningful contexts, for example:

| Kāre au i tino whai wā ki te hokihoki ki te kāinga. Ko te pōwhiri he mea āhua tauhou ki a rātou, nā reira, i tae atu ki te pōwhiri kātahi ka rongo i te karanga, ka kī a [tama], kua mate tētahi? (katakata). I mōhio ai i te tangihanga ēngari kāre anō kia waia ki ērā atu momo. Nā reira koinā tētahi o ngā āhua pai o te pōwhiri, kia waia ngā tamariki ki ērā whakatau. Tētahi atu i āhei au ki te tono atu ki te whānau kia haramai. Ahakoa kāre taku whānau i kōnei, kāre au i tono ēngari pai kia mōhio kia taea te pērā, rawe! Ka pai. Me te mea hoki kia tae mai te kōhanga hei tautoko, rawe! | I don’t get a lot of opportunity to return home. It was somewhat unfamiliar to them [mother’s tamariki], so when we arrived at the pōwhiri and heard the call of welcome [son about to begin transition visits] asked, “Has someone died?” (laughter). He knew about bereavement [pōwhiri] but he wasn’t yet familiar with other kinds [of pōwhiri]. So, you know, that’s one of the positive aspects of pōwhiri, to familiarise children with those kinds of welcomes. Another thing is that I was able to ask other family members to come. Although I don’t have family living in this area that was good to know. So it was great that the kōhanga came as support! (Mother) |

Yes I went to their whakatau which is a really good thing to do because all the kids see who’s about to come over and, and it’s a good way to whakanui [celebrate] the kids from the school’s behalf. So it’s not the run of the mill, oh here comes another kid, but here’s a taonga from the kōhanga that’s supported by the kōhanga and this taonga is coming into this school. (Father)

Understanding each other’s programmes and practices

As stated above, the two settings involved directly in the project were the Tōku Whakakai Marihi building at the kōhanga, and the classroom Te Aroha. While the kōhanga and kura kaiako researchers from these two settings knew each other as part of the kōhanga and kura whānau, whanaungatanga had not extended into their professional practice to any great extent. It also became evident that while all research team members shared global understandings about the programmes in the kōhanga and kura, specific understandings about these two settings were less evenly shared. Up until the start of the project, professional relationships between kōhanga and kura staff had largely revolved around the two tumuaki working together at the leadership level, including developing and sharing leadership-related knowledge, understandings, and practices.

During the project, kōhanga and kura kaiako researchers carried out observations of each other’s teaching programmes in their respective settings. Together, they discussed the observations and how they might incorporate their developing understandings into their respective programmes to support tamariki moving between the settings. They then presented their observations at hui rangahau for further discussion and analysis. Immediate changes resulting from the observation visits included kaiako incorporating karakia and waiata from each other’s settings. Kaiako also recognised how differences such as eating times, play activities, and cleaning up routines might affect tamariki when they started kura. This knowledge affected how the kura kaiako in particular interpreted and responded to various behaviours of transitioning tamariki.

Sharing assessment and learning information

Sharing understandings also extended to sharing assessment and learning information collected by the kōhanga. This resulted in changes, some almost immediate, in practices encompassing parents and whānau.

While parents were encouraged to share their tamaiti’s kete mātauranga (similar to learning portfolios) with the kura and kaiako, this was not happening in any systematic way at the start of the project. Moving to the Educa password-protected online system had, to a certain extent, interrupted previous approaches to information sharing. As a result, the kura did not consistently receive information about incoming tamariki as had been the case before the change. With consent, the new entrant kaiako researcher was able to view online assessment records and information of tamariki about to move to the kura.

A more formal request that parents help their tamaiti choose a pakiwaitara from their kete mātauranga to share at the interview was added to interview information given to parents. This simple change had an almost immediate effect on uiuinga; for example, the kura tumuaki noted:

| I tērā wiki ka uiui māua ko Dorie i ētahi whānau, ngā whānau e rua, ngā tamariki e toru … Ko tēnei te uiui tuatahi kua mau mai te tamaiti he pikitia, he kōrero rānei hei kaupapa kōrero mōna. Me te mīharo anō hoki te uiui tuatahi! I te mutunga, kī mai te pai o te kōrero, kāore he mutunga me kī, ki tana kōrero. Kei tana pepa ētahi whakaahua o te tamaiti e hāngai ana ki ngā momo taputapu … Koinā te kaupapa o tana kōrero … Engari, ko te mea mīharo ko te nui o ngā kōrero, me tana hikakatanga ki te whakaputa i ōna whakaaro … i tino rongo i tōna hikakatanga, i tino rongo i tōna reo. Tino kite i ngā rereketanga ki ētahi atu o ngā uiui … I ngā wā o mua ka tuku pātai noaiho ki te tamaiti, “kei te hiahia koe ki te haere mai ki tēnei kura?”, “he aha ngā mahi pai ki a koe?”. Engari ka noho whakamā te tamaiti. … Ohorere hoki ōna mātua. Pōhēhē i āta whakarite ngā mātua i a ia … engari i ohorere katoa ngā mātua! |

That week Dorie and I interviewed two whānau, three children … This was the first interview that a child brought a picture or story with them as a speaking focus. The first interview was amazing! In the end, the talk was so very good across many aspects, you could say there was no end to his talk. His paper included photos of himself building with particular materials … that was the topic of his talk … But the amazing thing was the amount of talk and his eagerness to express his thoughts, his eagerness and his language really stood out. The differences to other interviews were very clear … Previously we asked a child questions such as “Do you want to come to this school?” “What do you like doing?”. But the child often was overcome with shyness. … His parents were also taken by surprise. We mistakenly assumed that they had prepared him, but they were absolutely astounded! |

The change also triggered some parents to think about and to prepare in depth what they wanted to share at interviews; for example, the tumuaki described parents also bringing their own written statements:

| Kua tae mai ngā mātua me ā rātou tuhinga. I kite au i āta whakaaro rātou mō te uiui….

Ngā tuhituhinga e pā ana ki te tamaiti, e pā ana hoki ki ō rāua hiahia mō tā rāua tamaiti. Ko te wā tuatahi ka kite au i tērā āhuatanga. |

Parents arrived with their own written statements. I could see they had thought deeply about the interview …

The prepared statements were about their child, about their aspirations for their child. This has been the first time I have seen that happen in such a manner |

The kura kaiako researcher reflected on how sharing assessment information affected her knowing individual tamariki. Because of her iwi connections, involvement in sport and other community networks, and teaching older siblings, the kaiako often knew, or knew about, many of the tamariki and their whānau before they entered her classroom. The sharing of assessment information developed this knowing further: into a deeper learning-related pedagogical knowing, arguably providing potential opportunities to begin engaging with existing working theories and interests of a transitioning tamaiti, for example:

| I haere au ki te Kōhanga, i noho ki te taha o te tumuaki o te Kōhanga. I whakamārama mai, i whakaatu mai i Te Whatu Pōkeka, ngā pūrongo, ērā momo mea mō ngā tamariki. I tiro hoki ahau ki ngā tamariki e uiui ana … I tipakohia ētahi o ō rātou kōrero. Ka pānuihia ngā momo kōrero i kite ahau, he mea akoranga, he pūrongo hoki he kōrero, he pakiwaitara mō ia tamaiti …

I te taenga mai o te tamaiti tuatahi, tere tana whakaatu mai i ngā pepa i te pupuri ia me tana harikoa mo āna mahi. Anei ko taku kitenga atu, kua pānui kē ahau. Mōhio tonu ahau he aha ngā kōrero e pā ana ki a ia i roto i aua pepa. No reira i mua tonu i te kuhunga atu ko tana mahi ko te whakaatu mai. I tuku pātai au “Ō, he mahi pāngarau tēnei nē? He aha ō koutou mahi?”, ērā momo kōrero…. I te hikaka kē ia ki te whakamārama mai i āna mahi, e hiahia ki te whakaputa i mua tonu i te uiui! |

I went to the kōhanga and sat with the kōhanga principal who explained Te Whatu Pōkeka, reports, and other aspects relating to the children. I focused on the children about to be interviewed … I selected some of their records. I read across the different records I saw, some about learning, reports, stories for each child … When the first child arrived he was quick to show me the papers he was holding, along with his enthusiasm for what it showed him doing. I had already read them. I knew the content related to him in those pages. This happened before we went inside [for the interview], he was showing what he had done. I asked “This is a maths activity, isn’t it? What are you doing?”. Those kinds of talk … He was eager to explain what he was doing, he wanted to get it out even before the interview started! |

Ensuring ongoing relationships

Whanaungatanga was evident in parents’ descriptions of their longstanding involvement across the kōhanga and kura. Whanaungatanga carries expectations that relationships, roles, and responsibilities parents undertake do not disappear when tamariki move from one setting to another. Parents described maintaining whanaungatanga with the kōhanga even after all their tamariki moved to kura; enacted, for example, through attending kōhanga events and celebrations as well as taking their tamariki to visit kōhanga.

I’m still involved with kōhanga stuff, still on the committee for [event] … Cos [the event] happens every year, we still will probably be involved in the kōhanga. (Mother)

During whakawhiti kōrero carried out by kaiako researchers, tamariki in the process of moving from the kōhanga to the kura focused on what they thought was or might be different at kura. Before starting kura, tamariki talked a lot about what they would be expected to do at kura, such as:

Me noho pai ki te whāriki, me whakarongo ki a Whaea Dorie.

[You] must sit properly on the mat, must listen to Whaea Dorie.

Ki te haere koe ki te kura, he mahi kāinga. Me mahi au he mahi kāinga ki tōku whare.

If you go to school, there is homework. I must do the homework at my house.

They also had conversations about their tuakana who had already moved to the kura; for example:

| Kotiro 1: Mōhio au tōna hoa [referring to Kotiro 2], ko E

Kotiro 2: Ko E toku hoa Tama: Ko T tōku hoa! Ko T! Kotiro 2: Ko T C? Kotiro 3: Kāre a T e taea te kai hēki Tama: If you, if you are T, kaua e kai hēki! |

I know her friend, E

E is my friend T is my friend! T! T C? T isn’t able to eat eggs If you are T, don’t eat eggs! |

Whakawhiti kōrero with tamariki who had been attending kura for at least 2 months also included conversations about how things were different in the kura; for example, “Ka taea te tākaro i te wā poto.” ([You] can only play for a little while). Interestingly, however, conversations also included concern about maintaining whanaungatanga with the kōhanga. In the following example a group of tamariki who had attended kura for over 2 months were talking with a kōhanga kaiako researcher about what it was like being at the kura. They then proceeded to ask her why she was at the kura and then took over the conversation to locate themselves as still very much part of the kōhanga.

| Kotiro 1: He aha ai kei konei koe?

Researcher: He kōrero tēnei hei tāpiri atu Tama: Kei te uiui [i] a mātou? Researcher: Āe Kotiro 1: Nō te mea kei te haere a mātou ki te kōhanga Researcher: Kāo, he tamariki kura koutou ināianei Kotiro 2: Ko Kuaka kē mātou Tama: (goes to bag hanging on rail) ko tēnei taku peke Researcher: Pai tō peke ki a koe? Tama: I, I hoatu koe tēnei mea ki a au Kotiro 1: (gets her bag) …tēnei mea. Tama: [showing his bag]…tēnei… Researcher: Āe, ko tō taonga Kuaka, hei tiaki i a koe, ka noho koe i te kura |

Why are you here?

This is a conversation to follow on/ We are being interviewed/questioned? Yes Because we go to the kōhanga No, you are school children now We are actually kuaka This is my bag Do you like your bag? You gave this to me … and this … this … Yes, this is your kuaka treasure, to look after you at kura |

Kia mahitahi

The strands of Te Whāriki have been shown to align with the key competencies in the English medium New Zealand Curriculum. However, to date there has been little evidence about the degree of alignment between Te Whāriki and Te Marautanga o Aotearoa.

This project explored alignments and linkages between these two curricula and went a step further to trial this in action. This project revealed curriculum connections by focusing not just on “transition” between the two settings, but also on the possibilities of an innovative, culturally informed and culturally located blend of curriculum achieved through a shared commitment to kaupapa Māori education and whanaungatanga values and practices.

Teacher–researchers collaboratively developed and implemented kaupapa ako (units of learning) from a blend of Te Whāriki, Te Marautanga o Aotearoa and Te Marautanga-ā-Kura (the localised kura curriculum). Collaborative planning was carried out through face-to-face meetings and work-shopping, supplemented by Google docs. Collaborative planning provided opportunities to leverage off effective planning and teaching practices from both settings as well as “opportunities to discuss and throw ideas around” (kaiako researcher).

Collaborative teaching took place in either the new entrant kura setting where kaiako from the kōhanga and kura team-taught, or in both the kōhanga and kura settings where kaiako respectively implemented aspects of jointly developed kaupapa ako. The processes involved in planning and teaching together epitomised values and practices of whanaungatanga through mahitahi (working together).

Figure 1. Kaiako researchers discuss Te Whāriki and Te Marautanga o Aotearoa at research retreat

One of the associated research questions asked “How does the collaborative kaupapa of the akoranga whakawhiti integrate kura wahanga ako in ways that foster children’s emerging understandings?” Mahitahi provided opportunity for kōhanga and kura kaiako to collaboratively develop and implement kaupapa ako that had clear links to Te Whāriki and to wāhanga ako in Te Marautanga o Aotearoa.

For example, kōhanga and kura kaiako researchers collaboratively developed and implemented the akoranga whakawhiti, which spanned a number of weeks and focused on hangarua (recycling); this linked directly to the wāhanga ako Hangarau (Technology) and Pūtaiao (Science) in Te Marautanga o Aotearoa, and to the Mana Whenua and Mana Aotūroa strands in Te Whāriki with regard to the importance of relationships and responsibilities to the taiao (environment). Learning activities provided opportunities for tamariki to display their learning, skills, and understandings in a meaningful context, such as tuhituhi (writing) by writing their names on lunchboxes they created by recycling, and pāngarau (maths) by sequencing, grouping, and counting involved in preparing kai for their recycled lunchboxes.

Another associated question focused on opportunities tamariki are given to take responsibility for their own learning and assessment in the akoranga whakawhiti. What became very obvious from observations of tamariki during and after shared learning activities is that in kaupapa Māori education settings this can be enacted in ways that are underpinned by core Māori values and practices encapsulated in ako.

Taking responsibility for one’s own learning can involve taking responsibility for others’ learning, and tuakana– teina processes were evident in the ways that tuakana—that is, tamariki who had already started kura—worked with and supported their kōhanga teina as they learned together.

|

|

| Figure 2. Mahitahi: Kōhanga teina and kura tuakana learning about hangarua together |

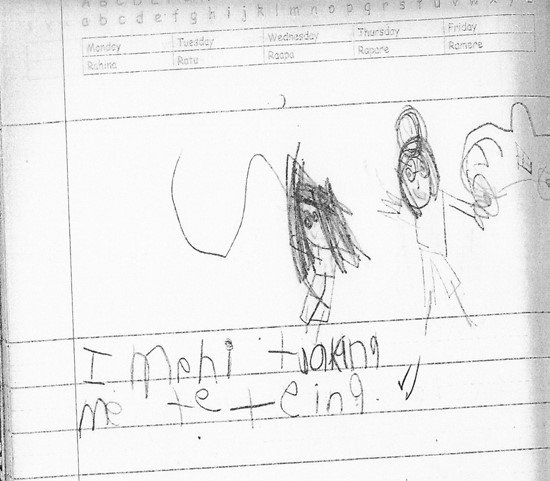

Figure 3. Kura tamaiti reflection on hangarua akoranga whakawhiti |

The importance of sharing one’s learning with others was also observed. Kōhanga reo tamariki were provided with formal opportunities to share their experiences and learning at akoranga whakawhiti with their teina, some of which were recorded. However, as described by one kōhanga researcher, sharing that was controlled by the tamariki turned out to be richer and deeper in terms of reflecting on and assessing their learning experiences:

| Ka mutu ana ngā mahi ki te Kura, arā ngā mahi hangarua, i hoki atu mātou ki te Kōhanga, i kuhu tōtika ki roto i te whare. Ko te mahi tuatahi o ngā tamariki, ko te ketekete, ko te kūkū, ko te koukou, ko te pīpī hoki, anō nei he kāhui manu e tautohetohe ana, e ketuketu ana, ka mutu, e whakahīhī ana i tō rātou haerenga ki te Kura. Ko te āhua o ngā kōrero, he mea whakatenatena i ngā tamariki i noho ki te kōhanga, kia tiro pae tawhiti ki ngā mahi a te kura … I whai wā hoki ngā tamariki i haere ki te Kura te kōrero ki mua i te whare katoa mō ngā mahi i mahia e rātou. Ki ōku whakaaro, he nui ake ngā kōrero i putaina i a rātou e kōrero ana ki ō rātou ake hoa i ō rātou ake wā. I te wā ka whakatū hei whai whakaaro, hei whakahoki kōrero, kāore rātou i tino kōrero mō ngā mahi. (Kōhanga kaiako researcher) | When we finished the hangarua activities at the kura and returned to kōhanga, the tamariki went straight into the whare. The first thing they did was to vigorously and spiritedly discuss and debate what happened at kura. The nature of the discussions was an encouragement to the kōhanga tamariki who were not yet transitioning to kura to look forward in anticipation to what they would do once at kura … Tamariki who went to the kura were given time to talk more formally to the [tamariki in their] whare about the things they had done. I think information they shared with their peers in their own time, on their own volition, was of far greater depth and quality, they didn’t really talk much at all about what they had done during that [formal] time. |

The final associated research question asked “In what ways does the akoranga whakawhiti support children’s learning and development by building on children’s existing working theories and interests?” Te Whāriki (Ministry of Education, 1996) describes working theories as forming out of “a combination of knowledge about the world, skills and strategies, attitudes and expectations” that help a tamaiti to “develop dispositions that encourage learning” (p. 44). What is evident from this project is that the kōhanga and kura purposefully create and construct opportunities for their tamariki to draw on “knowledge about the world” that is explicitly and unapologetically culturally located and that contribute to their working theories and interests as tamariki Māori who kōrero te reo Māori and who live in the Waikato-Tainui rohe.

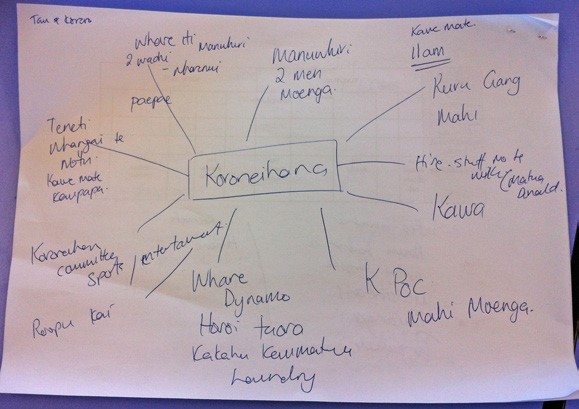

An example of building on children’s working theories as culturally located is a collaboratively developed koroneihana kaupapa ako (teaching unit). The koroneihana4 is a key annual event on the Waikato–Tainui calendar and the Māori calendar more widely. The event is held every year at Tūrangawaewae Marae in Ngaruawāhia to commemorate the coronation of King Tūheitia in 2006 and, before that, the coronation of his mother Te Arikinui Dame Te Atairangikaahu. The celebrations include cultural performances, sports competitions, educational displays and other festivities. In previous years the kōhanga and kura had planned and implemented separate koroneihana kaupapa ako or teaching units. As part of this project, kōhanga kaiako came together with the kura teina (junior syndicate) kaiako to plan and implement a collaborative kaupapa ako. Tamariki at the kōhanga and kura were involved in learning activities focused on the Kīngitanga and the koroneihana over a number of weeks.

Figure 4. Planning collaboratively: initial kaiako brainstorm for Koroneihana kaupapa ako

The kaupapa ako culminated in a re-enactment of “Rā Koroneihana”, involving tamariki, parents and whānau from the kōhanga, and the kura teina, and beginning with a pōwhiri followed by a hākari and kapa haka performances and ending with a series of games played by mixed groups of kōhanga and kura tamariki. Tamariki, along with parents, took on key roles and responsibilities throughout the day, from making korowai, preparing kai, and setting up rooms as marae and wharenui through to preparing and executing karanga, whaikōrero, and facilitating games.

Figure 5. Korowai made collectively by tamariki for Rā Koroneihana

Implications for practice

Understanding “transition” through kaupapa lenses

Findings from this project reinforce that what has been learned thus far from national and international research on transition in the early years has relevance to, and resonates with, similar journeys in kaupapa Māori education. However, movement between kaupapa Māori early childhood and primary settings brings with it unique educational, cultural and linguistic imperatives and aspirations. Rather than conceptualising the journey of tamariki and whānau from kōhanga to kura as “transition”, it might be better understood in terms of its significance to the ongoing growth, development, and evolution of a shared kaupapa.

[Re-]establishing shared knowledge and understandings of the kaupapa of Māori medium programmes and practices

This first phase of this project focusing on transition from kōhanga to kura underlined the importance of making time, place, and space for such settings to revisit together fundamental knowledge, values and practices that are the core of kaupapa Māori education, and to develop shared knowledge and understandings of each other’s teaching and learning programmes and practices. Supporting and strengthening kōhanga–kura transitions involves collaborative critical reflection through kaupapa Māori lenses.

Planning for an ongoing relationship

Particularly evident in this project are the longstanding relationships across the kōhanga and the kura that, together, initiated this project. Also evident are expectations that relationships and accompanying roles and responsibilities do not disappear when tamariki move from the kōhanga to the kura. The importance of pōwhiri is but one example of how ongoing relationships might be nurtured. How transition is approached in such settings affects how well the continuation of these relationships is supported.

Making the most of “Lucy” effects

Projects do not occur in a vacuum. Another development that undoubtedly put transition into the spotlight for some of the whānau during this project was the contract that involved working with early childhood centres and kōhanga across Hamilton. A person well-known to the kōhanga and kura helped to deliver the contract and some of the kōhanga whānau participated in the contract’s activities. The contract undoubtedly had a positive, reciprocal effect on this project; we dubbed this “the Lucy effect”.

Exploring further alignments and synergies between curricula

The project helped to highlight alignments and synergies between Te Whāriki and Te Marautanga o Aotearoa curricula. During the project, Te Marautanga o Te Aho Matua (Te Rūnanga Nui o Ngā Kura Kaupapa Māori o Aotearoa, 2015) was launched. Its launch and implementation provides potential opportunities to examine alignments and synergies between Te Whāriki principles and strands and the values underpinning Te Aho Matua.

The limitations of the project

It should be abundantly clear from above that this project involved a kōhanga and a kura with a strong, longstanding and ongoing relationship encompassing staff, whānau, tamariki, and supporters from the wider community. They are also situated in close proximity, literally on opposite sides of a gate. Generalising and applying findings from this project presents particular challenges to Māori medium early childhood and school settings who may have similarly close relationships but do not share such close physical proximity. While challenging, however, we do not see these issues as insurmountable, especially given the rising efficacy of social media and growing ability to connect and collaborate on planning and teaching and to share information in the digital space.

For Māori medium settings that have tamariki moving between them but have not developed, or are in the process of developing, strong ongoing relationships, there are arguably more questions regarding the applicability of our findings.

Conclusion

In the so-called global society, where knowledge is evermore internationalised, there are calls to support and maintain local knowledge, values and practices (Hohepa & Paki, 2017). Māori, along with other indigenous peoples, are devoting significant energy to ensuring cultural continuity and cultural regeneration. Education has become a key supportive site of Māori language and cultural regeneration. Kaupapa Māori education pathways, including kōhanga reo and kura kaupapa Māori, are a case in point, having te reo Māori, mātauranga Māori and tikanga Māori as cornerstones of their educational programmes.

Our position is that transition within kaupapa Māori pathways is best understood as a significant tool and a normal expected occurrence in an educational journey predicated on language and cultural survival and regeneration. This journey not only encompasses tamariki but also their whānau and kaiako. In this project, understanding and enhancing their journeys has centered on Māori knowledge, values, and practices. Positioning cultural values and practices as fundamental to successful transition in kaupapa Māori, and Māori medium education more widely, means that the relevance and applicability of transition research and theory in such settings can be critically engaged with and interrogated from within a Māori cultural-theoretical framework.

Ngā mihi maioha

E ngā tamariki mokopuna, e ngā kuaka e rere ana mai i te kōhanga ki te kura e kawea ana ngā moemoeā ā ō koutou whānau, e kore e mutu ngā mihi ki a koutou. E te whānau whānui o Ngā Kuaka, o Tōku Māpihi Maurea, ko koutou ngā ringaringa, ngā waewae o te mātauranga Kaupapa Māori, tēnā koutou.

Ngā mihi hoki ki ngā kaitautoko mai i te Rangahau Mātauranga o Aotearoa, e Alex Hotere-Barnes, Nicola Bright mā, tēnā koutou katoa. Tēnā hoki koutou e te kāhui mātanga mō ngā kupu āwhina. E te New Zealand Teaching and Learning Research Initiative, nā koutou te huruhuru i rere te manu nei.

Publications from this project

Book Chapter

Hohepa, M., & Paki, V. (2017). Māori medium education and transition to school. In N. Ballam, B. Perry & A. Garpelin (Eds.), Pedagogies of educational transitions: European and Antipodean research (pp.95-111). AG Switzerland: Springer.

National conference presentations

Hohepa, M., Paki, V., Oliver, D., Anderson, T., Hakaraia, T., Peters, S., Gilbert, T., Hawksworth, L. (2016). Te rerenga o ngā kuaka. Paper presented at Te Rito Maioha Early Childhood New Zealand Conference, Claudelands, Hamilton, New Zealand, 15-16 July. Paper presented by T. Gilbert and Laura Hawkesworth

Hohepa, M. K. & Hawksworth, L. (2015). Nau mai; Whakawhiti mai: Enhancing transitions from kōhanga to kura. Paper presented at He Manawa Whenua Indigenous Research Conference, Claudelands, Hamilton, NZ, 29 June–1 July.

Hohepa, M. K. (2014). Transitioning from kōhanga reo te kura. Paper presented at Te Kōhao o te Rangahau: Indigenous Research Conference. University of Waikato, Hamilton, New Zealand, 12-13 April.

International conference presentations:

Hohepa, M., Paki, V., Peters, S., Hawksworth, L., Olliver, D., Anderson, T., & Hakaraia, T. (2016). “From about the child to with the child”: Assessment and transitions in indigenous language education. Paper presented at the American Educational Research Association Conference, Washington DC, April 8-12. Paper presented by T. Hakaraia and M. Hohepa

Hohepa, M. & Hakaraia, T. (2016). Teachers Working Collaboratively to Support Transition in Māori Immersion Education Settings – Whanaungatanga in Action. Poster presentation at the Indigenous Peoples of the Americas & Indigenous Peoples of the Pacific American Educational Research Association Preconference, Thursday, April 7, 2016.

Hohepa, M., Anderson, T., & Olliver, D. (2015). Transitions and indigenous language settings. Paper presented at the American Education Research Association Conference, Chicago Ill, 16-20 April.

Hohepa, M. (2014). Transitions in indigenous education contexts. Symposium presentation: ‘Knowledge, identities and transitions’ at the 24th European Early Childhood Education Research Association (EECERA) Conference, Crete Greece, 7-10 September.

Hawksworth, L., & Gilbert, T. (2014). Tōku Reo, Tōku Ohooho, Toku Reo, Toku Mapihi Maurea, Tōku Reo, Tōku Whakakai Marihi. Workshop at The World Indigenous Peoples conference on Education, Honolulu, Hawai’i, 19–24 May.

References

Bishop, R., Ladwig, J., & Berryman, M. (2014). The centrality of relationships for pedagogy: The whanaungatanga thesis. American Educational Research Journal, 51(1), 184–214. doi:10.3102/0002831213510019

Bright, N., Barnes, A., & Hutchings, J. (2013). Ka whānau mai te reo: Honouring whānau: Upholding reo Māori. Wellington: New Zealand Council for Educational Research.

Bright, N., Barnes, A., & Hutchings, J. (2015). Ka whānau mai te reo—Kia rite! Getting ready to move, te reo Māori and transitions. Wellington: New Zealand Council for Educational Research.

Carr, W., & Kemmis, S. (1986). Becoming critical: Education, knowledge and action research. Lewes, U.K.: Falmer.

Dunlop, A.-W. (2017). Transitions as a tool for change. In N. Ballam, B. Perry, & A. Garpelin (Eds.), Pedagogies of educational transitions: European and Antipodean research (pp. 257–273). Switzerland: Springer.

Education Review Office. (2015). Continuity of learning: Education transitions from early childhood services to schools. Wellington: Author. Retrieved from http://www.ero.govt.nz/assets/Uploads/ERO-Continuity-of-Learning-FINAL.pdf

Hohepa, M., & Paki, V. (2017). Māori medium education and transition to school. In N. Ballam, B. Perry, & A. Garpelin (Eds.), Pedagogies of educational transitions: European and Antipodean research (pp. 95–111). Switzerland: Springer.

Hutchings, J., Barnes, A., Taupo, K., & Bright, N., with Pihama, L., & Lee, J. (2012). Kia puāwaitia ngā tūmanako: Critical issues for whānau in Māori education. Wellington: New Zealand Council for Educational Research.

McNatty, W., & Roa, T. (2002). Whanaungatanga: An illustration of the importance of cultural context. He Puna Kōrero: Journal of Maori and Pacific Development, 3(1), 88–96.

McNiff, J. (1988). Action research: Principles and practice. Basingstoke, U.K.: Macmillan.

Ministry of Education. (1996). Te whāriki: Early childhood curriculum. Wellington: Learning Media.

Ministry of Education. (2008). Te Marautanga o Aotearoa. Wellington: Learning Media.

Ministry of Education. (2009). Ka hikitia: Managing for success: The Māori education strategy 2008-2012. Wellington: Author. (Updated from 2008).

Ministry of Education. (2013). Ka hikitia: Accelerating success: The Māori education strategy 2003–2017. Wellington: Author.

Ministry of Education. (2016). Ngā Haeata Mātauranga: Annual report on Māori education 2015–2016. Wellington: Author. Retrieved from https://www.educationcounts.govt.nz/__data/assets/pdf_file/0016/172060/Nga-Haeata-Matauranga221116.pdf

Peters, S. (2004). “Crossing the border”: An interpretive study of children making the transition to school. Unpublished doctoral thesis. University of Waikato, Hamilton.

Pihama, L. (2010). Kaupapa Māori theory: Transforming theory in Aotearoa. He Pukenga Kōrero: A Journal of Māori Studies, 9(2), 5–14. Skerrett, M. (2010). Ngā whakawhitinga! The transitions of Māori learners project: Milestone 3. Unpublished report, University of Canterbury, Christchurch.

Smith, G. H. (1995). Whakaoho whānau: New formations of whānau as an innovative intervention into Māori cultural and educational crises. He Pukenga Kōrero, 1(1), 18–36.

Smith, L. (2012). Decolonizing methodologies: Research and indigenous peoples (2nd ed.). London, U.K.: Zed Books.

Te Rūnanga Nui o Ngā Kura Kaupapa Māori o Aotearoa. (2015). Te Marautanga o Te Aho Matua. Otaki, Aotearoa: Author.

Wesley, P. W., & Buysse, V. (2003). Making meaning of school readiness in schools and communities. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 18(3), 351–375. http://dx.doi.org.ezproxy.waikato.ac.nz/10.1016/S0885-2006(03)00044-9

Project team

Te Kōhanga Reo o Ngā Kuaka

Tirau Anderson

Tere Gilbert

Teina Hakaraia (2015)

Te Manu Pohatu (2014)

Tōku Māpihi Maurea Kura Kaupapa Māori

Laura Hawksworth

Dorie Olliver

Te Whare Wānanga o Waikato

Margie Hohepa

Vanessa Paki

Sally Peters

Contact information – margie.hohepa@waikato.ac.nz

Notes

- In 2015, Te Marautanga o Te Aho Matua was released by Te Rūnanga Nui o ngā Kura Kaupapa Māori o Aotearoa for kura kaupapa Māori adhering to Te Aho Matua.

- Image retrieved from http://www.rgbstock.com/photo/mjYARZw/Maori+carving+3

- We acknowledge issues of translation and that concise translations do not necessarily reflect the full meaning of a term or phrase.

- See http://koroneihana.com/