1. Introduction

The driver of this research arose from the findings from our earlier TLRI-funded research on academic literacy (see Emerson et al., 2015): that there was a significant disconnect between literacy expectations in the tertiary and secondary sectors, and that information literacy (IL) was a key to that transition. We perceived IL as a hidden aspect of the curriculum that, if addressed, could deepen student learning and enable effective transition. Further, we saw IL resources—primarily the librarian—as hidden and underutilised within the tertiary and secondary classrooms.

The importance of IL, described as the meta-competency or metaliteracy of the digital age (Lloyd, 2003; Mackey & Jacobson, 2011; Secker & Coonan, 2012), and IL instruction in education is long established (The Alexandria Proclamation, 2005; Head & Eisenberg, 2010; Jones-Jang et al. 2021). Yet international studies suggest secondary leavers and graduating tertiary students may not have the skills/knowledge to navigate the increasingly contested information landscape (Emery & Fancher, 2017; Leetaru, 2016; Wineburg et al., 2016). No comparable studies exist of New Zealand students’ capacity to engage critically and ethically with information.

And so, in this study, we brought the IL expertise of the librarians onto centre stage. How could we understand the role of the library in the senior secondary and tertiary sectors, and the barriers and enablers that impacted on the librarians’ capacity for classroom engagement? And how could we bring teachers and librarians into collaborative partnerships, based on mutual recognition of professional expertise and a deep shared understanding of IL, for the sake of disciplinary learning?

2. Aims, objectives, and research questions

The research questions that directed this study were:

- Are collaborative teacher–librarian partnerships effective as a method of integrating IL into the disciplines in the context of New Zealand senior secondary curriculum and the first year of higher education?

- What factors enable such partnerships in New Zealand secondary schools and institutions of higher education?

Within this context, the aim of this project was to integrate IL into the disciplines by enabling and resourcing collaborative teacher–librarian partnerships across the senior secondary sector (Years 11–13) and first year of higher education. We achieved this by partnering with teachers and librarians from four tertiary institutions and six secondary schools to investigate and transform the IL space(s). Together, we developed new collaborative relationships to design and implement instructional approaches and resources that prioritise the critical use of IL skills to learn disciplinary content knowledge. Our specific objectives were as follows:

Objective 1: To determine how the library and IL instruction are currently placed, resourced, and used, how they are perceived by teachers and librarians, and identify systemic and attitudinal barriers to, and enablers of, collaboration within the IL space.

Objective 2: Based on the findings from objective 1, to facilitate and resource sustained collaborative partnerships between librarians and teachers within the IL space in secondary and tertiary learning environments in the context of student learning.

Objective 3: In the context of objective 2, to collaboratively develop new teaching/learning strategies and resources to facilitate students’ IL competencies and learning.

Objective 4: To evaluate our IL strategies/resources/progressions in relation to shifts in participants’ attitudes, beliefs, professional identity, and practice, and whether we have been able to eliminate the barriers and harness the indicators for collaboration.

3. Framework for the research

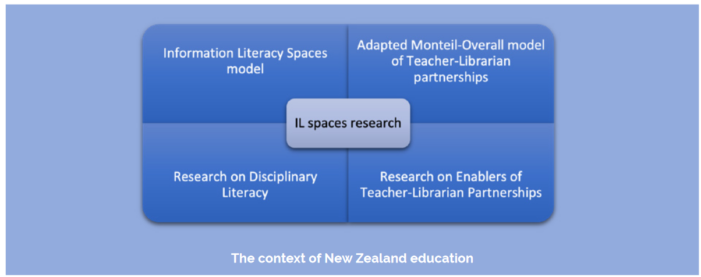

Five factors were used to guide our research (Figure 1) and are discussed below:

- The context of education in Aotearoa New Zealand.

- The IL Spaces model of information literacy.

- The literature on disciplinary literacy.

- A model of teacher–librarian partnership.

- The literature on enablers of and barriers to teacher–librarian partnerships.

FIGURE 1: Framework of the IL spaces research

3.1 The New Zealand context

The context of this research is important: factors within the educational environment can restrict or enable effective collaborative teacher–librarian partnerships and the positioning of IL within the curriculum. Two factors were particularly significant: the positioning of IL within the curriculum and the positioning of the library within formal learning environments.

Information literacy within the curriculum

Within the secondary sector, Aotearoa New Zealand’s 2007 Curriculum in English Medium Schools (The New Zealand Curriculum (NZC)—Ministry of Education, 2007) establishes the national instructional principles, key concepts, and progress monitoring systems for literacy instruction in primary and secondary schools where English is the dominant language of instruction. In the secondary years (Years 9–13 or Levels 4–8), the dominance of disciplinary content instruction remains a systemic feature of programme design, timetabling, and national assessment. This positions IL skills as an inferred presence across NZC’s learning areas, apart from the English Learning Area. The pre-eminence of disciplines makes content instruction the defining feature of classroom instruction as opposed to deliberately teaching the IL skills students need to make critical sense of the content they are receiving in their disciplinary studies.

Whereas general literacy instruction for Years 1–8 is well detailed, NZC includes little information to support secondary school teachers in designing teaching programmes that balance what students need to know with how they should learn it. The introductory commentaries and pedagogic sections of NZC do acknowledge the need for a critically informed citizenry, the economic benefits IL skills generate, and the opportunities for fulfilment and advancement they offer to the individual. It accurately identifies the rationale and imperative for an information literate society, but provides limited detail for teachers, especially in the secondary sector, on how that can be made real within its various discipline-focused teaching programmes.

Similarly, in the tertiary sector, IL remains largely a “hidden skill”, essential to learning but unlikely to be written into graduate outcomes or course prescriptions (Feekery, 2013; Feekery et al., 2016). International studies (e.g., Jastram et al., 2014) suggest that academic staff may make incorrect assumptions about students’ IL “readiness”, or fail to recognise the IL skills inherent in disciplinary learning and assessment tasks. In both the secondary and tertiary sectors, then, we see IL as inherent, but to some extent unrecognised or underrecognised within the curriculum.

The positioning of the library

The concept of libraries contributing to successful student outcomes is widely accepted globally; however, in the New Zealand context there are barriers to consistent levels of service across all secondary schools. A significant barrier is the lack of professional recognition of librarians employed in the school sector. While Australia and the United States provide pathways for teacher–librarian qualifications, such opportunities ceased in New Zealand decades ago. This is not to indicate that librarians without such qualifications are not able to meaningfully contribute to the learning in schools, but it does speak to the perceived value of school library staff and understanding of their contribution to learning.

The Ministry of Education and National Library of New Zealand (2002) published guidelines for the place of the school library in the information landscape. These guidelines included a section on IL and the role of the school library in the development of these skills. Three years later, the Education Review Office evaluated to what extent schools were supporting student learning in the information landscape. The resulting report found that IL was a particularly weak area with “few examples of a school-wide, integrated approach using an information process model” (Education Review Office, 2005, p. 2) and that less effective practice could be related to inadequate library staffing making meaningful links between library staff and teachers difficult (p. 36).

In the tertiary sector in recent years, we have seen considerable movement in the role of the library and librarians. The library is generally more central to these institutions (compared with school libraries), requiring a significant financial investment (Carlson, 2022). While there is a longer tradition of librarians engaging with and supporting academic staff, a conflict exists between older and more contemporary views (see Section 3.4) of the role of librarians (Dawes, 2019; Jastram et al., 2014). Librarians struggle to play a broader role within teaching and learning, beyond an occasional tutorial and links on course websites (Shields & Bennett, 2006). Feekery’s (2013) interviews with librarians at all eight New Zealand universities showed librarians believe that placing the library outside the context of disciplinary learning maintains IL development as remedial and/or adjacent to content instruction.

3.2 Information Literacy Spaces model

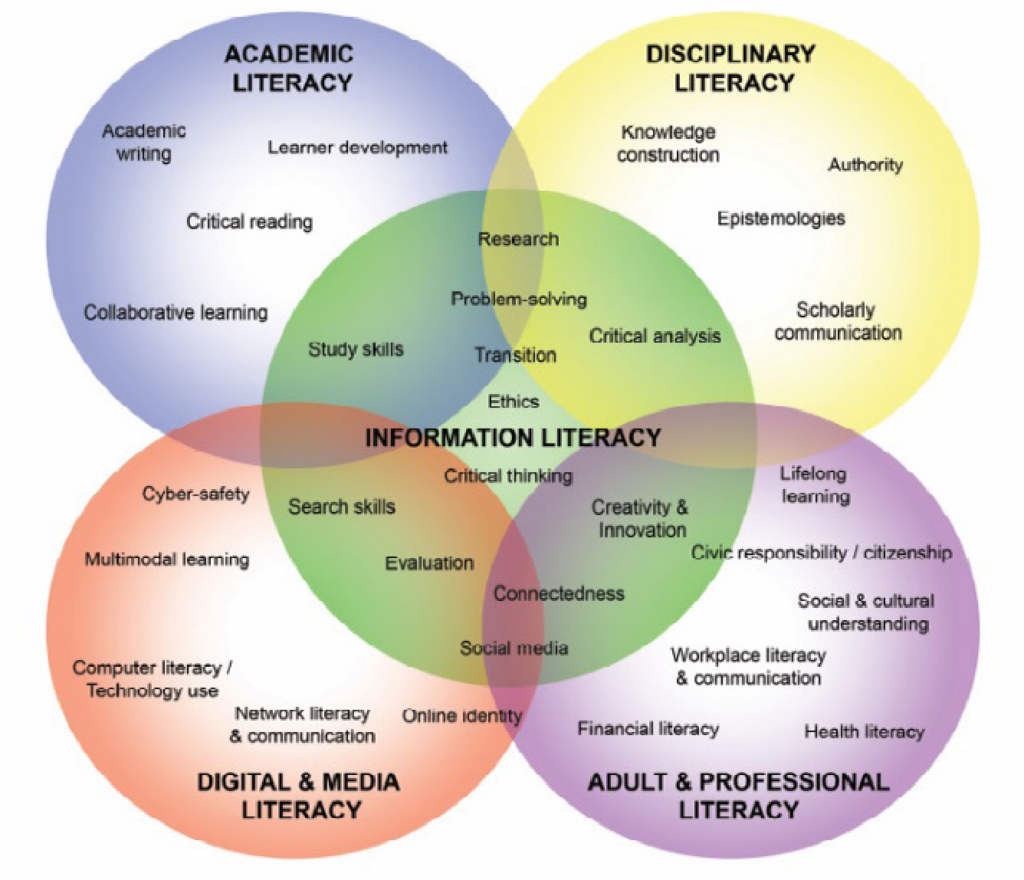

Traditionally, IL has been defined simply as the ability to find, evaluate, and use information (Association of College and Research Libraries, 2000). However, as Gilbert (2005) and Hipkins et al. (2014) argue, fundamental changes in the information landscape, the professional environment, and our understanding of the purposes of education, have led to educational contexts where we value meaning making rather than simple knowledge acquisition. Students’ interaction with information (audio, digital, visual, multimodal, or printed) must, therefore, be more engaged, fluid, and critical (Sandretto & Tilson, 2013). As students develop IL competencies, they need to think about, learn from, and create new information for a range of disciplinary and digital (and, in the future, professional and civic) purposes. Educators within and across sectors need to engage with “IL space(s)”; that is, those spaces in which multiple factors (libraries and librarians, disciplines and teachers, digital information ecosystems and tools, and institutional learning contexts) create capable, critical, information literate learners.

In this study, we adopted—in line with current IL models—a broad and holistic definition of IL as the centre of learning: that IL involves the processes, strategies, skills, competencies, expertise, and ways of thinking that enable individuals to engage with information to learn across a range of platforms to transform the known, and discover the unknown.

Figure 2, adapted from Secker and Coonan’s (2012) model of academic IL, illustrates the IL Spaces model we used in this study, a model that clearly establishes the centrality of IL within models of multiple literacies.

FIGURE 2: The IL Spaces model

3.3 Research on disciplinary literacy

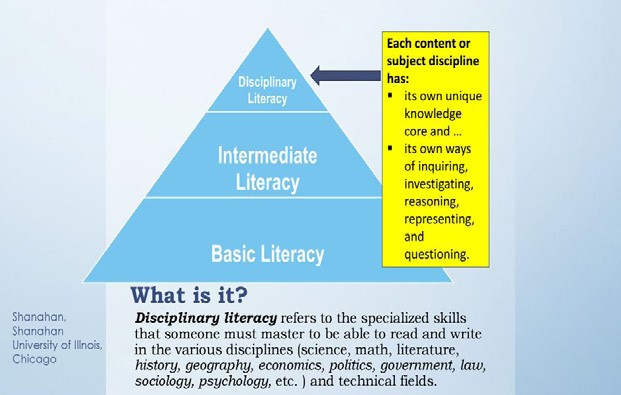

Adolescent literacy research investigates the role of the discipline in defining what being literate means for success in secondary and tertiary settings. It challenges educators to reconsider conventional models of literacy that have promoted generic comprehension and writing skills that students could deploy, regardless of text type or purpose (Ministry of Education, 2004). Using Shanahan and Shanahan’s (2008) literacy learning model (Figure 3), this project conceptualised literacy as a disciplinary construct that requires students to use more specialised skills, processes, and strategies to read, process, and communicate information from a variety of disciplinary texts, each of which reflects particular approaches to knowledge building and validation, and ways of inquiring, investigating, reasoning and presenting disciplinary knowledge. These are skills that advance and refine the generic approaches, as students are required to grapple with and learn from increasingly specialised and complex content area texts (Taylor & Kilpin, 2015.

Educators are shaped by these powerful subject conventions that they intuitively reproduce and reinforce in their own practice as they teach their students the content knowledge that will be communicated, often via assessment practices, to peer subject specialists. They commonly, and mistakenly, anticipate that students, upon entering senior secondary school, and later post-secondary learning, can, like themselves, actively learn from multiple forms of subject content texts that variously exemplify the epistemological processes disciplines use to shape, structure and organise, and communicate knowledge (Fang & Coatum, 2013; Kilpin et al., 2014; Shanahan & Shanahan, 2014; Wolsey & Faust, 2013).

FIGURE 3: Shanahan and Shanahan’s (2008) Literacy Learning model

Regardless of discipline area, students must be able to critically evaluate the quality, currency, and reliability of primary and secondary source information, as baseline skills. But the disciplinary context shapes how these attributes are understood and applied. Students in all content areas need to read, comprehend, and then write to process and communicate information—core IL skills—but the physicist, historian, and mathematician will each, in different ways, strategically read and write to comply with their accepted literacy norms (Moje, 2008). In other words, being disciplinary literate gives students the capability to access complex texts, navigate their structures, identify and select relevant information, process and shape it towards the task set, and be able to report their new learning in ways that comply with that discipline’s communication conventions (Whitehead & Murphy, 2014). Integrating IL into the curriculum as an aspect of disciplinary literacy was a central tenet of this research.

3.4 Model of teacher–librarian partnerships

To form our teacher–librarian partnerships, and to gauge shifts in these partnerships, we adapted MontielOverall’s (2005) Teacher–Librarian model (see Figure 4). By developing this model, we were able to establish what interactions, or indicators, help develop a productive, professional collaboration, where disciplinary content learning and IL skills instruction are integrated to improve student achievement. Montiel-Overall characterises collaboration as:

a trusting, working relationship between two or more equal participants involved in shared thinking, shared planning, and shared creation of integrated instruction. Through a shared vision and shared objective, students’ learning opportunities are created that integrate subject content and information literacy by coplanning, co-implementing and co-evaluating … (2005, p. 32)

| Models of teacher–librarian working collaboration | |||

| Co-ordination | Collaborative | ||

| Type 1: Siloed Siloed, isolated, and distant |

Type 2: As needed Co-operative, but “as needed” |

Type 3: Shared Shared topic instruction |

Type 4: Integrated Shared curriculum instruction |

| Booking role and monitoring activities (meetings, small assemblies, clubs), responding to requests, book/resource borrowing. Safe place for students. Little instructional emphasis. Library is peripheral/ irrelevant to teacher’s practice. Teacher dominated. | Mutual acknowledgement of specific areas of expertise and what library and librarian offer, but role is confined to supplementing teacher’s role with short-term, but planned, instruction. Opportunistic, immediate, or “as needed” use. Teacher directed. | Content learning and relevant research/IL skills are woven together into instructional plans and course work. Teacher and librarian acknowledge each other’s expertise and use these to enhance students’ content learning and achievement. They negotiate topic objectives and share teaching and assessment roles. Shared responsibility but teacher led. | Teacher–librarian collaboration reconceived as long-term curriculum/ programme relationship. Transcends topic/task levels of interaction. Libraries are common sense sites for instruction, librarians participate in long-term curriculum and programme planning, and feature naturally in wider academic functions. Shared responsibility according to instructional need and participant expertise. |

We saw this as a realisable ideal, keeping in mind that this model had to work within assessment-dominant environments, where disciplines are largely siloed and finding opportunities for educators and librarians to negotiate collaborative partnerships is always challenging. We thus aimed to shift our teacher–librarian relationships from Co-ordinated (Type 1 or 2) to Collaborative (Type 3 or 4).

2.5 Factors that enable teacher–librarian partnerships

Finally, multiple studies in both sectors have endeavoured to classify the enablers and barriers to collaborative teacher–librarian partnerships. Mattesich and Johnson’s (2018) model of collaboration is especially helpful in identifying enablers and barriers, outlining a series of “critical factors” for collaboration around five main headings: environment; membership characteristics; process and structure; communication; and purpose.

In terms of enablers, the literature suggests multiple factors are important. First, a shared understanding of the role and value of librarians in IL instruction and pedagogical strategies is crucial in laying a foundation for sustainable collaborative development (D’Orio, 2019; Kammer et al., 2021; Kimmel, 2011; Schroeder & Fisher, 2015). While an expectation may exist that educators collaborate, the formation of these partnerships can vary greatly depending on how librarians are viewed and whether there is a sole librarian or a library team within an organisation (Kammer et al., 2021; Merga et al., 2021). Both Kammer et al., (2021) and Baker (2016) suggest that teacher recognition of the value of school librarian expertise leads to an environment of shared understanding and professional learning vision and shared planning (which deepens collaborative efforts). Second, teachers and librarians need a shared understanding that successful student achievement as a result of such collaboration rests on integrating instruction and curriculum (Baker, 2016; Kammer et al., 2021; Montiel-Overall, 2005). Finally, in learning environments where mindset and purpose are shared, and clear communication exists, the single biggest factor enabling successful, sustainable collaboration may be the principal or senior leadership team (D’Orio, 2019; Kimmel, 2011).

In terms of barriers, Baker (2016) identifies a lack of communication between educators and librarians as likely to impede effective collaboration. And even when the purpose of the collaboration is clear and the desired outcome of all partners, a lack of time or prioritising available time presents a barrier to acting on these (Kammer et al., 2021). It should be noted that time relates not only to the alignment of collaborative partner schedules but is also necessary to the establishment and deepening of trust within partnerships (Kammer et al., 2021).

In this research, we aimed to bring together the IL Spaces model of IL, the literature on disciplinary literacy, a modified version of Montiel-Overall’s model of teacher–librarian partnerships, and the literature that outlines the factors for effective teacher–librarian partnerships, within the educational context of Aotearoa New Zealand. Using this framework, we designed our approach to making change in the senior secondary and first-year tertiary environments.

4. Methods

Participatory action research (PAR) was the overall methodology used to guide the project. One of the strengths of PAR is that it can be used to ensure all participants are equally valued within the team and seen as contributing essential skills and knowledge to the team (Kemmis, 2009)—this was particularly important in our team which included a wide range of individuals differently positioned within the hierarchy of learning organisations. Our aim was that all would be empowered to both understand and change their environment, “not only to solve concrete problems but also to enable everybody involved to acquire the ability to investigate their situation in a systematic manner, to reflect self-critically and to act autonomously” (Stern, 2019, p. 435).

Within the PAR context, we used a mixed methods approach to our research, data collection, and analysis. Figure 5 provides a summary of data collection methods used in relation to the project’s objectives, and further detail is provided in the sections below. Further information and examples of the instruments we used can be found in Emerson et al, 2021

| PAR process | Research objectives | Practice | Data collection methods |

| Objective 1: Understanding the current situation (reconnaissance) |

To determine how the library and IL instruction are currently placed, resourced, and used, how they are perceived by teachers and librarians, and identify systemic and attitudinal barriers to, and enablers of, collaboration within the IL space. | Survey teachers (see Lamond et al., 021; Macaskill & Greenhow, 2021).

Establish a baseline of student skills. Establish wider policy environment. |

Four national surveys:

Surveys included quantitative and qualitative data. Are you ready? rubric—student data (secondary and some tertiary) Document collection re libraries in schools in New Zealand (policy documents, Education Review Office reports, research literature). |

| Objective 2: Collaborative partnerships (planning and action) |

To facilitate and resource sustained collaborative partnerships between librarians and teachers within the IL space in secondary and tertiary learning environments in the context of student learning. | Participatory action research project: Case studies.

Project plans established. Baseline data of secondary/ tertiary student IL skills. |

Start-up individual and focus group interviews with teachers and school/tertiary librarians in our participating institutions.

Are you ready? rubric—student data (secondary and some tertiary). |

| Objective 3: Resources (planning and action) |

To collaboratively develop new teaching/learning strategies and resources to facilitate students’ IL competencies and learning. | Participatory action research project: Teacher– Librarian–Researcher engagement in context. | Resource collection and evaluation. |

| Objective 4: Evaluation (reflection) |

To evaluate our IL strategies/ resources/progressions in relation to shifts in participants’ attitudes, beliefs, professional identity, and practice, and whether we have been able to eliminate the barriers and harness the indicators for collaboration. | Teacher– Librarian Collaborative Relationships model |

All of the above. Focus group interviews with students and individual interviews with librarians/teachers. Group reflection exercises prompted by our observations. |

Ethics approval was sought and obtained through Massey University’s Human Ethics Committee.

4.1 The surveys and rubric

The baseline study in year 1 of our research included four national surveys involving quantitative and qualitative data: two in the senior secondary sector (teachers and librarians) and two in higher education (teachers and librarians). The aim of the surveys was to determine how the library and IL instruction are currently placed, resourced, and used, how they are defined and perceived by teachers and librarians, and to identify systemic and attitudinal barriers to, and enablers of, collaboration within the IL space (objective 1). See Macaskill and Greenhow, 2021, and Lamond et al., 2021 for more detail about the surveys).

The secondary school surveys were sent to the office email address of all New Zealand schools on the Ministry of Education’s downloadable directory (https://www.educationcounts.govt.nz/data-services/ directories/list-of-nz-schools) with a request to forward the survey to all teachers and librarians in their school. Two reminders were sent, and the survey was also promoted through discipline-specific interest groups, School Library Association of New Zealand Aotearoa (SLANZA), and the school library list-serv. Eighty-five school librarians and 135 teachers completed the survey.

Tertiary surveys were distributed through academic librarian email list-servs and the research teams’ institutions (polytechnics and universities). Two hundred and one valid responses were received from 90 librarians and 111 teachers. Responding librarians had a range of roles, with the majority being active IL teachers or in a leadership role, and 92% holding a library studies qualification. In terms of levels, they were teaching into, teachers indicated a relatively even spread across year levels.

The surveys were analysed using statistical methods for the quantitative data (e.g., Independent-Samples Mann-Whitney U test, Bonferroni-corrected Chi-square tests, Spearman’s rank correlation). The qualitative data were analysed using hand coding to identify key themes, the responses in each category were quantified, and then further categorised into subthemes for further analysis.

Quantitative data were collected from students using the Are you ready? rubric at the beginning of the school-based case studies and five of the tertiary case studies. The rubric was also used to shape decisions around pedagogy and student support. The rubric is a self-perception tool that asked students to rate their literacy skills on a 4-point scale (basic, emerging, proficient, and advanced) using descriptors. More detail about the rubric is provided in Section 7.2 and Feekery and Macaskill, 2021.

In addition to the quantitative data, we collected documents related to libraries in schools (policy documents, Education Review Office reports) and met with representatives of the National Library.

4.2 Collaborative partnerships

Within the larger cycle of PAR, we used PAR to develop our case studies (collaborative partnerships) and to align practice and research strategies over years 2 and 3 of the research.

One strength of action research is its flexibility in context (Kemmis et al., 2014; McNiff & Whitehead, 2011). Within the PAR framework, teachers and librarians formed collaborative partnerships and, together, developed and implemented IL strategies within their classroom/course(s) that met the specific requirements of the discipline and needs of the student group. The teams used the IL Spaces model to develop class-appropriate interventions, such as integrating IL into assessment, content, assigned readings, in-class activities, and/or online course content and activities, as deemed appropriate by the teacher/ librarian partnership (in consultation with, and supported by, the research team). Intervention project planning and implementation drew on the expertise of teachers and librarians, IL literature, and the support of the research team.

The teacher–librarian partnerships within schools were initiated by the teacher or librarian and were supported by a dedicated member of the research team who ran workshops on integrating IL into the curriculum and provided as needed support throughout the project. Each partnership developed a project plan that identified a problem (e.g., lack of depth in engaging with information) and an aim (e.g., deepening information engagement) and then worked together to achieve their aim by integrating IL instruction into their teaching. In many instances, this involved relocating classes to the library and shared instruction.

Data collection methods for this aspect of the project were primarily qualitative: individual and focus group interviews were carried out with teachers and librarians at the beginning and end of the project and written individual and group exercises were collected at critical points in the project interviews were transcribed, and all transcriptions and written reflections were hand coded for thematic analysis.

We collected data relating to students in three ways: the rubric; focus group interviews; and teacher perceptions. Our use of the rubric to measure changes was constrained by the school context: many schools were too busy to fit in a second completion of the rubric, and, where this was attempted, insufficient students gave permission for the findings to be included in our research. In most case studies, therefore, we relied on teachers/librarians reporting on the impact of the IL instruction work/partnerships on student outcomes: this was consistent with the research design, where teachers/librarians identified the problem and solution to be addressed.

4.2.1 Participants

In this research, we worked with teachers and librarians from six secondary schools and four tertiary institutions. There were 19 case studies in all. Individual case studies were as follows:

| Institution | Initiated by | Disciplines | Participants |

| Southland Boys’ High School | Librarian |

|

1 teacher 1 librarian |

| Aurora College | Teacher |

|

1 teacher* |

| Central Southland | Teachers and Librarian |

|

2 teachers 1 librarian |

| Whanganui City College | Teacher |

|

4 teachers 1 librarian |

| Waitara High School | Teacher |

|

2 teachers 1 librarian |

| Kerikeri High School | Teacher |

|

1 teacher 1 librarian |

| Whitireia/Weltec polytechnics |

Librarian |

|

5 teachers 3 librarians |

| Massey University | Teacher |

|

4 teachers 3 librarians |

| Victoria University of Wellington | Librarian Teacher |

|

3 teachers 2librarians |

* The librarian resigned very early in the project and her replacement did not start until much later. The Biology teacher did, however, shift his former pre-project siloed practice towards implementing one of the project’s aims—to improve students’ IL skills, especially research techniques and processing information from primary and secondary source subject content materials—with less library involvement than other schools (but including support from the librarians in the research team).

5. Results and discussion—Objective 1: Understanding the current situation

5.1. The national surveys of teachers and librarians

The findings of our surveys in relation to schools are reported in detail in Emerson et al. (2018, 2019, 2021) and in higher education in Lamond et al. (2021) but are summarised here to outline the cultural milieu into which this research was introduced.

The secondary sector

Our findings suggest libraries and librarians in schools are “under-recognised, under-used, and under-valued” (Emerson et al., 2018). Further, our surveys suggest a mismatch between the attitudes of teacher and librarian respondents to both definitions of IL and the role of the library/librarians:

Information literacy

- While there is considerable overlap in teacher and librarian definitions of IL, teachers tend towards a more traditional definition, while librarians are more likely to identify contemporary and indigenous aspects of IL.

- Teachers and librarians both view IL skills as of great importance for academic success in the senior high school and at tertiary level but showed less confidence that NCEA and NZC supported IL development.

- A significant group of the librarians (20%) showed limited knowledge of NZC or NCEA.

The role of the library

- Teachers view the library and the librarian positively but may lack awareness of the range of services the library offers.

- Teachers and librarians see the function of the library differently. Teachers tend to perceive the library and librarian as a support resource with the librarian undertaking traditional roles such as overseeing the collection of and issuing books. Librarians, by contrast, aspire to professional partnerships and to be an integral component of teaching and learning.

- Teacher and librarian attitudes to what constitutes a successful collaborative working environment are different: librarians focus on building effective relationships and finding opportunities for communication, while teachers focus on resources (the space, IT components, book collection) and the “helpfulness” of the librarian.

- Teacher and librarian attitudes concerning barriers to collaboration are different: teachers focus primarily on resources, while librarians see multiple obstacles to effective collaboration (limited perceptions of their role, lack of support from senior management, being shut out of planning meetings, lack of communication, the transience of professional relationships).

The tertiary sector

Information literacy

- As with the secondary sector, while there was overlap in teachers’ and librarians’ definitions of IL, librarians demonstrated a more contemporary understanding informed by indigenous approaches.

- Librarians and teachers saw IL as very important for life success, with some differences in priorities.

- But far fewer teachers and librarians saw their institution as prioritising IL. Fewer than 50% of academics and librarians considered that their institution prioritised “understanding primary sources” to any extent.

The role of the library

- Teachers showed some uncertainty about the services offered by their libraries, with only 32% being confident that the library provided help with planning teaching and the curriculum, suggesting a lack of awareness about the expertise librarians could bring to supporting academic progress and achievement may be a significant barrier to collaborative professional relationships.

- The key barriers to collaboration as identified by both groups were academics’ lack of time, and a reliance on personal relationships. Professional relationships were seen as both a strength and a weakness when it came to collaboration.

Overall, there was far more agreement between teachers and librarians in the tertiary sector than was evident in the secondary sector, but our key takeaways were academics’ lack of understanding of the potential of the library to support their teachers and the mismatch between both groups’ perceptions of the importance of IL compared with the way they saw their institution valued IL.

5.2 Student skills

Secondary sector

At the beginning of each of the schools’ case study, most students completed the Are you ready? rubric to establish a set of baseline skills. It is important to note that the rubric was used as both a data collection method and a learning tool. The composition of the rubric and how it was used as a learning tool is discussed in Section 7.2 and more detail is provided in Feekery and Macaskill. (2021).

Students’ responses remained stable through the 3 years of the project, indicating that the emerging patterns provide a reasonable guide to what to expect from incoming students in these schools in future years in terms of information strengths and weaknesses.

Students were more likely to identify their skills as basic or emerging on the following items:

- understanding what an in-text citation is and how to correctly create reference lists using referencing systems such as APA (widely used in New Zealand universities)

- awareness of Google books, Google scholar, online databases, and use of the library to find or access information

- willingness to reflect on the information skills they used to get information for a task before moving on to the next task

- thinking about who wrote information they found or why it was written

- understanding how to narrow and perform more efficient searches on Google.

Students tended to rely on their teachers or friends for help. Both librarians and the library were largely untapped resources; a majority of the students (62%) never asked their librarian for help. Key strengths were:

- willingness to change their search terms in Google

- using Wikipedia only as a start from which to find additional sources

- recording where information comes from

- understanding what plagiarism is

- capacity to judge whether information is relevant to a specific task

- knowing when they have enough relevant information.

Items from the Academic Literacy key competency featured more prominently in strengths than in weaknesses. Many students spent time editing their work, considering grammar, spelling, and punctuation as well as content and structure. This is good news as it suggests that, despite earlier research suggesting students dislike and resist disciplinary writing for learning (Emerson et al., 2015; Shanahan & Shanahan, 2014), students seem to have a positive predisposition to writing and place value on doing this well.

Tertiary sector

In the tertiary section of our study, while the survey was used in three polytechnic case studies and two university case studies, a much smaller group of students gave permission for their data to be used for research purposes. Only one class provided sufficient data for us to complete some analysis.

While, on the whole, the tertiary students were more confident in their skills than the secondary students, there was a significant group who perceived their skills to be basic or emergent in key issues related to information:

- 45% have limited search skills using Google

- 58% had never used Google Books or Google Scholar or online databases (beyond Google)

- 41% do not think about the origins of the information they’re using and 35% don’t know how to assess whether information is trustworthy

- scores for recording information, understanding how to use an inline citation, and writing an APA reference list were also low.

This is important information for teachers of first-year students: these skills cannot be assumed.

As with the secondary students, most students did not commonly seek help from the library or librarians.

In terms of strengths, students perceived strengths related to staying on topic when they’re writing, connecting ideas in their writing, thinking about content and structure, editing their work, and understanding plagiarism. The latter, however, is an interesting finding in relation to some of the students’ perceived strengths: it is difficult to align poor scores on recording information and using referencing conventions with a strong understanding of plagiarism.

6. Results and discussion—Objective 2: Collaborative partnerships

6.1 Secondary sector

Details of the partnerships are provided in more depth in Chapters 9–11 of Emerson et al., 2021, but here we observe our broad findings.

The first observation is to note that all the partnerships fully or partially achieved their aim and/or discovered another benefit of the partnership. For example, in one case study (see Emerson et al., 2021, pp. 157–158) the primary problem identified by the teacher was student engagement, with the teacher struggling to understand why there was a lack of engagement and how to address it. The outcome of the partnership was improved student engagement but also improved grades, and—perhaps most importantly for the teacher— the teacher’s improvement in his own IL skills and an understanding of why relocating to the library was important for student outcomes.

Second, all case studies within the school sector changed the relationship between the teacher and librarian to a more advanced collaborative relationship (see Figure 7), using Montiel-Overall’s (2005) model of teacher–librarian relationships. In some case studies, the shift was substantial (i.e., from siloed to integrated).

| Initiated by | Disciplines | Initial type | Final type | |

| Southland Boys’ High School | Librarian | Science | Siloed | Shared |

| Aurora College | Teacher | Biology | Siloed | n/a |

| Central Southland College | Teachers and Librarian | English Biology |

As needed As needed |

Shared Shared |

| Whanganui City College | Teacher | Biology Māori Performing Arts History Physical Education |

Siloed Siloed Shared Siloed |

Shared Shared Integrated Shared |

| Waitara High School | Teacher | English Chemistry |

Siloed Siloed |

Shared Shared |

| Kerikeri High School | Teacher | English | As needed | Shared |

This shift in the relationship had multiple benefits including changes in understandings, attitudes, practices, and skills. These are discussed in depth in Section 8 of this report.

6.2 Tertiary sector

In the tertiary sector, like the secondary case studies, each case study was distinctive in terms of being specifically designed for the context (e.g., university or polytechnic, previous relationship of the librarian with the teacher, the way the library is positioned within the institution) and discipline. Creating a space for change was challenging in the universities, in particular where changes to assessment or course content may take a long time to change due to the institution’s institutional quality assurance processes.

The case studies were located in a range of disciplines and were not managed by a single member of the research team, as was the case in the secondary section of the research; instead, most cases were managed by a separate member of the research team who was already engaged with the specific institution, and some were managed by the academic within the discipline. This may have contributed to some of the differences in outcomes: specifically, the interventions in the polytechnics were led by librarians on the research team, whereas those in the universities were mostly led by academics on the research team or course coordinators, which may have had an impact on the way the collaborative teams were formed and managed.

All the projects within the tertiary sector included collaboration between the teacher(s) and librarian(s) and the intentional integration of IL into the curriculum in terms of pedagogy, curriculum, and assessment. Most of the tertiary projects lasted for 2 years to allow for innovation through two PAR cycles, which made it possible to trial an intervention, assess it, and revise the IL strategy.

Detailed descriptions of individual case studies are found in Section 5 of Emerson et al. (2021), but broad observations from the tertiary case studies are noted here.

| Whitireia/Weltec polytechnics | Librarian | Nursing Music Hospitality |

Shared As needed As needed |

Integrated Integrated Integrated |

| Massey University | Educational developer

Teacher |

Nursing

Management |

As needed

As needed |

Integrated

Shared |

| Victoria University of Wellington | Teacher | Architecture Psychology |

As needed As needed |

Shared Shared |

First, on the whole, the position of the librarian in relation to teaching staff began at a more advanced level than that of most of the schools (i.e., they began at the “co-operative, as needed” level from Montiel-Overall’s (2005) model rather than the “siloed” level (see Figure 8)). This is perhaps to be expected: in the universities, in particular, the library is seen as an essential part of a research-based institution and is a significant budget item. Teaching staff demonstrated respect for the role of the librarians and their expertise, but initially perceived that expertise quite narrowly (e.g., in terms of inviting library staff to run workshops on information searching).

Second, most projects moved on Montiel-Overall’s model to the level of shared topic instruction, with some elements of shared curriculum instruction (e.g., there was indication of a long-term integrated engagement, with teachers and librarians sharing the IL instruction, and librarians being engaged to some extent in assessment design).

One unexpected outcome was that we saw more movement in the polytechnic collaborations than we did in the universities. The collaborations in the polytechnics were generally more integrated, included more librarian engagement within the classroom and more librarian engagement in the planning stages (including problem and aim identification), and demonstrated a clearer shift in teacher attitudes to the librarians as well as a closer relationship between the teacher and the librarian. The reasons for this remain speculative, but part of the difference may be attributed to the fact the librarians initiated the projects in the polytechnics, while the university projects were mostly initiated by academic staff and/or a member of the research team. As well as this, we may point to the fact there is no requirement or tradition of continued professional development in relation to teaching and learning in universities, and that teachers at universities traditionally have greater autonomy over course design than in the polytechnics. It would be useful to trial librarianinitiated IL projects within the universities to investigate this further.

7. Results and discussion—Objective 3: Development of resources

The teacher–librarian partnerships were supported through professional development opportunities on the disciplinary nature of IL and the research on the impact of teacher–librarian partnerships and the attributes of such partnerships. Within this context, teachers and librarians (sometimes together but sometimes apart) developed their own resources, sometimes (but not always) with assistance from the research team. As well as this, the research team developed resources to support the partnerships as the research progressed and we saw a need.

Within each case study, both teachers and librarians developed resources to meet the IL skills needs of their student cohort. For example, Senga White (White, 2021, p. 103, a librarian from Southland Boy’s High School throughout the project, developed an IL skills framework for Years 7–13 and a series of infographics to support her teachers and students, while Anais Jousserand-Shirley et al. (2021) developed a series of online learning objects to support students in the first-year architecture programme at Victoria University of Wellington. Similarly, teachers in both sectors created resources to support their classes’ IL development (e.g., a scaffolding “living document” by a secondary biology teacher (see Cross et al., 2021, p. 139) and tutorial exercises in a first-year university management course (see Barney, 2021, p. 206). They also discovered and used existing resources in new ways: of particular significance for the secondary teachers was their introduction to specific online databases (e.g., Carrot) which they either were not aware of or did not know they could access from school.

Beyond this, two key resources were developed or refined by the team and used broadly in the project: the Rauru Whakarare Evaluation Framework and the Are you ready? rubric.

7.1 The Rauru Whakarare Evaluation Framework

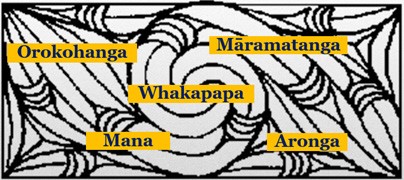

FIGURE 9: The Rauru Whakarare pattern

The Rauru Whakarare Evaluation Framework (RWEF) developed out of one of the librarian–academic partnerships in our project, a first-year university business communication course, instigated by the teacher who was also a member of the research team. The aim was to support students to engage in deeper evaluation practices, in a way that would be meaningful to business students, and also to create a model that would be informed by Māori principles. One of the challenges was to align the English evaluation criteria words of standard evaluation tools (Feekery & Jeffrey, 2019) such as CARS (Credibility, Accuracy, Reasonableness, Support) and CRAP (Currency, Reliability, Authority, Purpose) with Māori terms to engage Māori students while capturing a complex, non-linear understanding of evaluation that fitted with our holistic views of IL.

The RWEF combines key Māori concepts and existing evaluation criteria as a tool to help students to think in new ways about information evaluation. By taking a holistic approach to source evaluation informed by the Māori concepts of Whakapapa (background), Orokohanga (origins), Mana (authority), Māramatanga (content), and Aronga (perspective), the framework creates a meaningful approach to the information evaluation process that is deeper than Western concepts and unique to Aotearoa New Zealand. The embedded depth and connectedness of Māori terminology is difficult, if not impossible, to capture in an English translation. Thus, the framework encourages students to consider a range of interconnected evaluation factors as they find, select, and evaluate information.

After its successful use in the business communication course, we introduced the framework to our schools, where it was seen as providing a model of IL that could be integrated across the whole curriculum, Years 9–13. Our hope is that this framework may prove useful across the school and university curricula and provide a deeper model to engage students in the complexity of evaluating source material. Indeed, we are aware, as our research ends, that several schools outside of the research are using the model after locating it on our website, and librarians at both Massey University and Victoria University of Wellington are actively promoting the framework in a range of discipline areas.

More information about the framework and how it was developed can be found in Feekery and Jeffrey (2019) and on our website:

https://informationliteracyspaces.wordpress.com/rauru-whakarere-evaluation-framework/

7.2 The information literacy rubric

The Are you ready? rubric: An Academic Literacy Self-Assessment Tool to Help you Transition into Tertiary Learning (hereafter, “the rubric”) was first developed by our research team in 2014 and refined through this project by the research team on the basis of student and educator feedback. Key changes included having more concise descriptors and simplifying concepts.

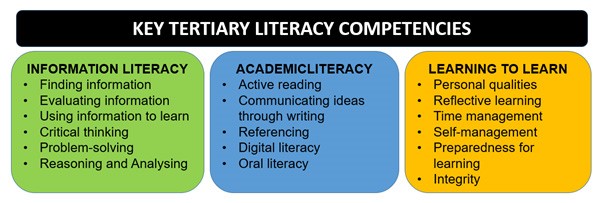

FIGURE 10: Key tertiary literacy competencies

Structured around the three key literacy competencies (IL, Academic Literacy, and Learning to Learn—see Figure 10), the rubric provides a list of 52 items that the students use to self-assess their skill level on a 4-part competency scale (basic, emerging, proficient, and advanced). The proficient and advanced levels identify skills, competencies, and behaviours we determined are required for tertiary study, informed by a combination of approaches to IL such as the ANCIL framework (Secker & Coonan, 2011) and our reflection on our own professional practice with students. In Year 13, therefore, students should be working towards proficient levels of understanding and application, with most advanced skills, particularly for cognitively demanding tasks (i.e., those that provide opportunities for critical thinking and require students to make connections), being developed throughout the first year of tertiary study.

The rubric is a self-assessment measure: that is, it measures students’ own perceptions of their skills level rather than providing an objective assessment of those skills. However, it is more than this: our teachers found the rubric to be an effective learning tool, providing them with an assessment that enabled them to scaffold their literacy learning activities to the needs of their class. One of our teachers discusses how he used the rubric as a pedagogical tool to deepen students’ learning:

The second seminal moment came when I began to use the Are You Ready? information literacy self assessment rubric as the core of metacognitive conversations with students. I began to use it with every aspect [of ]my programme, whereas previously it had mostly been a ‘before and after’ measurement tool. This created a mindshift away from packaged and processed content learning to ‘learning how to learn’, that was tranformative for me and for my students. (Johnstone et al., 2021, p.120)

To sum up, teachers and librarians within the project developed new learning resources and used existing resources (often in new ways—e.g., using the rubric as a teaching tool) aimed to promote students’ IL skills. While these resources were designed and used with a specific context and disciplinary focus in mind, many

teachers reported that students were transferring the skills learnt through these resources to other discipline areas. More broadly, the research team developed two key pedagogical resources that are designed to be used in a wide range of discipline areas, and that could potentially form the basis of an institution-wide approach to IL development.

8. Results and discussion—Objective 4: Evaluation

8.1 Teachers and librarians

Secondary sector

Across the participating teachers, a number of themes emerged which may be summarised as follows:

De-siloising practice: In all cases, the collaborative framework underpinning this research supported teachers to allow their librarian into the instructional role they had hitherto solely occupied. Teachers welcomed their librarian colleagues into their teaching plans and practice and, in working in partnership with the librarians, grew to recognise the professional attributes these colleagues possessed, and their inherent value for students’ learning and achievement. The enthusiasm with which teachers and librarians embraced these possibilities was heartening. Their readiness to co-operate also signalled that involving others in your own practice does not place student achievement, nor teachers’ own professional standing, at risk. Instead, the evidence confirmed the substantial benefits of this work to teachers’ skills and knowledge, of librarians’ being more directly involved in students’ academic experience, and for students’ opportunities to learn relevant skills and knowledge more deeply.

Most notable was the fact that all students worked on the unit to the end—completion rates increased! They became more confident meeting the academic requirements of the standard, which meant they were able to put more theoretical content into their practical work. [The librarian’s] work improved their basic research skills which in turn improved the quality of the assignments’ content … they had no problem accepting her as a teacher of information literacy skills. (Physical education teacher)

More widely, de-siloising teacher practice prompted participants to consider what professional expertise means and how current systems of secondary and tertiary education make less visible what colleagues can truly offer the instructional environment.

An interesting observation regarding de-siloising relates to the need to shift students’ expectations of roles and responsibilities. Several of the teachers reported that students doubted that a librarian could have a role to play in teaching for an NCEA assessment (e.g., “Students doubted whether she was teaching them but as time went by, they became less resistant to the idea of her as an expert” (Kean et al., 2021, p.157)).

Passive to active instruction: Teacher instruction was reported by participants to have shifted/moved from a traditional transmission model of teaching. Many participants noted that various modes of transmission teaching, where the teacher does much of the cognitive heavy lifting, which is then packaged and presented to students, were directly challenged by the student-centred pedagogical and relational positions implicit in the research’s aims, methodology, and implementation. Teachers and librarians were encouraged to create tasks that required students to actively undertake scaffolded authentic research tasks from which, again with guidance, they practised how to process information, link it to prior knowledge, use it to build further knowledge, and then shape and communicate it. An example is given in this discussion by a Year 13 history teacher who comments that initially his teaching promoted “surface-level teaching and learning at best. I now realise that students who did well did so more in spite of me, rather than because of me.” His intentional scaffolding of learning opportunities that would, in his words, make “a real difference to students’ independence and agentic behaviour” led to this:

A recent refinement was the student reflection at the end of each topic, based on the focus and rationale they set in place at the beginning. While the marking and feedback conversation was an important and enriching conversation, the student-led learning-to-learn conversations quickly became a better one—more satisfying and importantly more authentic.

This social constructivist model positioned the teacher as a facilitator of knowledge and skills learning, wherein students were supported to apply IL skills to content topics, such as nuclear reactions in Year 12 chemistry, or deep-sea species survival in biology, then guided to build their own accurate knowledge base, and the skills to report what they had learnt. We would argue that the presence of the skilled librarian was a key factor in teachers’ confidence to shift their practice towards this student-centred approach, as they had the skills to support the research process teachers were asking students to use for learning.

The role of metacognition: Related to this was teachers’ emerging understanding of what IL skills were in the context of their disciplinary instruction. Metacognitive reflection began to lead teachers to understand themselves as successful disciplinary learners and to identify what skills, processes, and strategies they intuitively reach for to complete the types of tasks they expect of their students. For example, one of the science teachers in our study discusses realising that her students didn’t use a simple information search strategy she took for granted:

The first workshop went over tricks and tips and hacks to find information from a set of books we used. It was eye-opening for me to see that many students thought they should read the whole book rather than look specifically for the information they needed using the title, the contents page, index, etc.

A second aspect was pedagogical, wherein teachers were asked to transform intuitive taken-for-granted skills into objects of instruction delivered through well-planned learning tasks. The inclusion of the librarian was pivotal. Librarian colleagues provided teachers with a professional reference point to which they could look for assurance their reflections were “on the right path”. A number of teachers commented that they learnt as much from their librarians as the students had. For example, one of our English teachers commented:

Personally it was useful for me having [the librarian’s] assistance with databases. She checked over other IL resources that I have put together for other year levels. It was worthwhile having another set of eyes and feedback about the IL skills content of the resources I use.

Another English teacher saw the possibilities right away:

I could see straight away the potential for her to help out in areas where I am not strong; for example, using databases … We both wanted to be there for all the classes. This would allow [the librarian] and me to divide our labour, each of us specialising and sharing our expertise with the students.

Furthermore, growing metacognitive awareness of their IL skills catalysed their confidence to alter and align their own practice to their librarian’s skill set. This essentially foregrounded IL learning, bringing into explicit view teachers’ skills that would otherwise have remained anonymous and invisible.

Shifting librarian practice: In all our schools, the role of the librarian was reported to have shifted significantly, becoming far more integrated into classroom instruction. Librarians who had never taught a class before were now developing their wings as teachers! In addition, they learnt more about NCEA and its modes of instruction, and built new relationships with teachers and students:

I could not have anticipated the strength of relationships this experience has built with the students, the teachers and me—the support staffer in the library! Workdays now seem more purposeful and urgent. My awareness of the intricacies of classroom practice and lesson structures is developing and I am no longer on the outside looking in.

Tertiary sector

In most cases, the collaborative model led to learning on both sides of the teacher–librarian partnership. Teaching staff made room for librarians to investigate and innovate within their own practice. As one librarian commented:

This project has been a powerful opportunity that has pushed me beyond my boundaries. (Librarian, nursing, polytechnic)

One of the challenges was for librarians to re-think themselves as teachers:

The experiences I gained through my involvement in this project allowed me to reflect on what teaching and learning meant to me. I learnt to be student-focused and value reflective practice in my teaching. One key insight was the importance of putting students at the centre of my focus when teaching IL. I began to think about how to convey core concepts in a way that made sense to the students, and helped encourage interactions and engagement with the topic in a safe environment. (Librarian, hospitality management course, polytechnic)

Teaching staff also experienced the partnership as a learning opportunity, as evidenced by this comment from a polytechnic nursing tutor, discussing how she and the librarian problem solved through their two different approaches:

In our first planning session I discovered that even though [the librarian] and I had been working together for many years, we each had a different understanding of what was needed to search databases. We spoke a different language. I wanted the students to understand database research to inform best practice. Unlike other academic courses, research skills do not just support students’ academic assignment writing. Nurses’ professional requirements and ongoing competencies require them to evidence best practice, so it is important that they know how independently, in the workplace, to find and evaluate the quality of information. We made a conscious decision therefore that going forward we would change our language from ‘research’ and refer to skills required to maintain ‘best practice’ standards. (Nursing tutor, polytechnic)

8.2 Students

Secondary sector

In one school, students completed the rubric at the beginning and end of the school year. While the number of responses was small, they did show the impact of a year’s engagement with IL learning (see Figure 11) on this small group.

| Question | Yes | No | Total | ||

| Do you remember what were identified as your strengths and weaknesses when you completed the rubric earlier this year? | 27.27% | 6 | 72.73% | 16 | 22 |

| Did your teacher discuss your rubric results with you? | 22.73% | 5 | 77.27% | 17 | 22 |

| Do you feel that your skills at finding information have improved this year? | 75.68% | 28 | 24.32% | 9 | 37 |

| Do you feel that your skills at evaluating information have improved this year? | 62.16% | 23 | 37.84% | 14 | 37 |

| Do you feel that your skills at acknowledging sources have improved this year? | 61.11% | 22 | 38.89% | 14 | 36 |

| Do you feel that your skills at using and organising information have improved this year? | 59.46% | 22 | 40.54% | 15 | 37 |

| Do you feel that your skills at reading and writing process have improved this year? | 67.57% | 25 | 32.43% | 12 | 37 |

Two open questions focused specifically on the impact of the Are you ready? rubric. In response to the open question How did you use the feedback report that was emailed to you after you completed the rubric?, only six students responded but only three expanded on their thoughts to indicate whether the rubric had been a useful learning tool:

[I] looked more into where my sources came from and applied this to my English and biology internals. In internals where we had to evaluate our sources, I would spend more time researching authors and establishing what their qualifications were, were they biased or not etc.

[I] looked at my weaknesses and focused on them to help me become better at research findings and things.

I read it and have gone back to it several times while doing work throughout the year. I have used it to improve my skills at school.

Eleven students commented on the open question How did completing the rubric affect how you think about your own information skills? Two students reflected negatively: it didn’t help them. But other comments indicated a positive impact. Some examples are provided below:

- It made me realise to what extent I needed to improve.

- It made me want to do better at collecting information and showing where I got it from and I think that throughout the year I have improved in doing so.

- It made me realise I need to keep bettering my information skills so I can reach a level where I instantly recognise things like what ideas are coming from an article and how to show conflicting ideas in my writing.

- [It] made me realise that my research skills were not actually that great but since completing the rubric I have practised some more and have gotten much better at it.

- I have been conscious about my learning skills and how I retain information.

Teachers also reported positive impacts on students of the IL learning facilitated by teacher–librarian. As we noted in Section 6.1, all teachers reported positive impacts in terms of their aims, but many also reported outcomes they had not expected. Most were initially concerned primarily with grades or engagement and saw positive outcomes in these terms (see Emerson et al., 2021, pp. 132, 140, 144, 156, 158). However, teachers also noted positive impacts in terms of independent learning, depth of research, improved outcomes for male students, higher completion rates, increased confidence, and transferability of knowledge to other disciplines and in the year following the project:

I think the success of [this school’s] involvement in this project will continue to be seen in the years to come. Already I have noticed an improvement of information literacy skills in my Level 3 English class, especially in students who were involved in this study during their Level 2 history class last year. (English teacher)

In previous years, students had often come up with great topics and then struggled to find the relevant information. Consequently they had to dumb down their topics to access relevant information and their engagement dissolved. This … cohort was able to access the information. Their topics were a lot wider and the research was a lot deeper. (English teacher)

When students who had already experienced this learning [in the biology class] came to me, I was surprised at how much they had remembered. They were able to identify the skills they used in the biology context and confidently went about their research with very little prompting or revision. (Chemistry teacher)

One finding of this research, though, showed mixed results in relation to changing student perceptions of the role of the librarian. Several of our teachers commented on student perceptions that the role of the librarian was not to teach but to engage in more basic functions like issuing books and that this changed throughout the project:

Initially, students doubted [the librarian’s] role—they were reluctant to trust her and questioned why their teacher should be sharing the floor with the school librarian whose perceived job was to sort and issue library books. Given this perception, I realised from the outset that, for this approach to work, I would have to support [the librarian] wholeheartedly in her teaching role. As we anticipated, it didn’t take long for the students to trust [the librarian] and then later openly acknowledge that her teaching was indeed useful for them—not just for this assessment in English, but across the broad range of their subjects. (English teacher)

Some students, too, reported a change in their perception of the librarian’s role:

I think that the role of the librarian sort of changes as you get older too. When you start at Year 7–8 they’re more just telling you what books to maybe read or something like that, when your Standards don’t require so much information or whatever, you’re doing just what you learn in class. But I think making boys aware of how a librarian can actually help with research and all that and their expertise in that area is quite important. So, sort of making, maybe younger boys aware of databases and stuff like that, things they know about to like improve their study and learning is quite beneficial, so it sort of changes … (Year 12 student)

However, it was notable that the language most students used in focus groups relating to the librarian indicated that, while they saw her as having useful skills, they continued to see her primarily in the role of “helper”. Given that no students used this noun to describe their teacher’s role in facilitating their learning, this suggests that they still perceive the librarian as having less professional standing than their teachers. So, while the teachers did report that students became more likely to engage proactively with the librarian, it seems that their attitudes to her role had not fundamentally developed.

Tertiary sector

Within the tertiary case studies, student data primarily drew on staff perceptions, as well as focus group interviews with students.

All our teachers commented on the impact of these collaborations on student outcomes and attitudes:

We observed quite a change from previous cohorts who had also done the same assignment. This time, the assignments actually took more time to mark because the students were citing material and journals that I was not familiar with which meant that I needed to go to source material to check their authenticity … I also noticed a change in the students within clinical practice. When they were out on placement, they would discuss what they had learnt in their conversations about best practice. When I asked them what they knew was ‘best practice’ they would often discuss a journal article they had found. This was very important to me as I could see the students had made the link from theory to evidence-based practice and had then transferred the IL skills into the workplace. (Nursing tutor, polytechnic)

Students have even reported in … course evaluations that they discovered the value of the library for the first time, expressing surprise about the resources that it has to offer. (Architecture lecturer, university)

Some of the focus group interviews also pointed to students seeing the value of IL instruction:

Yeah, so the whole referencing thing, it was quite useful, but the whole credibility of resources was probably something that I was sort of conscious of but hadn’t really thought about it as in depth as [the lecturer] took us through. Which I think was really really valuable. (Management student, university)

In a focus group for the university nursing course, students also focused on the credibility of resources as a key aspect of their learning—and also indicated they had more confidence finding quality information on their own and engaging with purpose-focused reading skills.

However, students were not always positive about the integration of IL into content courses. In some of the university courses, while many students commented on the valuable skills they had learnt, some students through course evaluations and focus group interviews expressed a view that IL learning should not be integrated into a discipline course because it took time away from the discipline (which was their primary interest):

The structure and focus [of the course] need to be adjusted. The assignments feel more like research and writing skills-based than knowledge and application of management skills … I think course should be modified to support learning management more … this is a management course not a writing skills course … More about actual management, less about theories, essays etc. … (Student, business management course, university)

Similarly, focus group interviews showed some student resistance in the university nursing programme, where students questioned the extent to which IL was prioritised in the curriculum.

At least in part, this may be attributed to an issue several teachers commented on: the difficulty of integrating IL into the curriculum in the face of large and diverse classes, where some students had few IL skills while others were well-prepared. It may also reflect a tendency of students to focus on disciplinary knowledge, without understanding the significance of IL development to their futures. But another factor also emerged from the interviews: students sometimes struggled to see the real-world application within their professional programme. This was despite staff working hard to make connections between IL and professional application. In the end, the criticism from students came down to assessment—both the nursing and management courses primarily assessed knowledge using traditional methods: essays, academic reports, and tests. This contrasted with the polytechnic nursing programme where assessment was more authentic to professional learning.

Changes in practice, attitudes, beliefs, and capabilities are discussed at length by teacher and librarian participants in Emerson et al. (2021) (School participants, Chapters 9–11; Tertiary participants, Chapters 13–18). We also asked participants to write about their experiences and changes in beliefs, attitudes, and practices on our blog.[1]

9. Conclusions

We return, then, to our two defining research questions.

First, are collaborative teacher–librarian partnerships effective as a method of integrating information literacy into the disciplines in the context of New Zealand senior secondary curriculum and the first year of higher education? Our research showed that collaborative partnerships had benefits for teachers, librarians, and their students within a New Zealand educational context. Our secondary teachers reported a move to more active learning strategies, improved confidence in integrating IL into the curriculum, a deepening of their understanding of IL, and a changed view of the librarian’s role as an educator. Our tertiary teachers, too, reported more confidence integrating IL into the curriculum and most reported a broader view of the librarian’s role. In moving into a more collaborative, co-constructed space (Montiel-Overall, 2005), the librarians in our study in both sectors also reported more confidence in the classroom, a greater sense of personal fulfilment in their job, and a deeper understanding of the curriculum/discipline and its corresponding assessment requirements. For students, we noted stronger academic achievement, deeper IL skills, and a greater willingness to engage with the library.

We turn, then, to our second question: What factors enable such partnerships in New Zealand secondary schools and institutions of higher education? In our research, we factored in all the elements identified as enablers in the literature (see Section 3.5): shared understanding of the role of the librarians; a focus on integrating IL into the curriculum through appropriate pedagogies; the support of senior leadership; and effective communication. These clearly contributed to effective partnerships.

However, two other factors may have been equally important in making our partnerships more collaborative, with their consequent positive outcomes. First, a key aspect of the collaborative partnerships in this research is that they were resourced. Especially in the schools, we grounded these partnerships in professional development opportunities related to information literacy and disciplinary literacy. This deeper understanding of disciplinary literacy and its associated pedagogies helped cement partnerships, filling in knowledge gaps (e.g., librarians’ understanding of NCEA and NZC and teachers’ awareness of IL resources available to them through their school), and opening up a space for co-teaching. A shared understanding of disciplinary literacy provided a shared language, further facilitating communication and making it easier for the partnerships to articulate problems and commit to aims. Other resourcing such as RWEF and the rubric, may have also been helpful in providing pedagogical tools and shared language.

Second, we provided a process that required the co-construction of aims through the project plans and monitoring of outcomes. While this PAR approach is consistent with the professional inquiry model promoted through NZC (see https://nzcurriculum.tki.org.nz/Teaching-as-inquiry), its use in teacher–librarian collaborative partnerships, in both sectors, is new and provides a model of such partnerships going forward.

It is our hope that future research will explore our findings further. In particular, as our RWEF is used widely in both the secondary and tertiary sectors, we see opportunities for further research into its effectiveness as a learning tool. But our greatest hope, as we conclude this research, is that educational institutions in this country will see the resource “hidden in plain sight” in their libraries. We have written elsewhere (Emerson et al., 2018, 2019) of the marginalisation, vulnerability, and missed opportunity represented by librarians. This study has shown that, when librarians are brought into the classroom, supported through collaborative partnerships to share their IL expertise as part of classroom instruction, and appropriately resourced, there are benefits to teachers, librarians, and students alike. Information literacy has never been more important: we need to value and utilise the IL expertise in our midst.

Footnote

- Examples can be found at: https://informationliteracyspaces.wordpress.com/2019/07/22/of-mice-librarians-and-geographyteachers/#more-1960 and https://informationliteracyspaces.wordpress.com/2019/10/07/that-was-then/#more-2038 ↑

References

Alexandria Proclamation. (2005). Beacons of the information society: The Alexandria Proclamation on information literacy and lifelong learning. In IFLA, UNESCO, National forum on information literacy (Vol. 9).

Association of College and Research Libraries. (2000). Information literacy competency standards of higher education. American Library Association.

Baker, S. (2016). From teacher to school librarian leader and instructional partner: A proposed transformation framework for educators of preservice school librarians. School Libraries Worldwide, 22(1), 143–159.