Introduction

Early childhood education has an important role in building strong learning foundations to enable young children to develop as competent and confident learners. The need for more work on how early childhood education can better support Māori and Pasifika children to reach their potential is highlighted in findings from the Education Review Office (ERO) report, Success for Māori Children in Early Childhood Services (ERO, 2010). This report argued that services lacked strategies that focused upon Māori children as learners and, despite often including statements about Māori values, beliefs, and intentions in their documentation, these were very rarely evident in practice. A nationwide review of Pasifika literature also identified a need for comprehensive evaluative research on Pasifika early childhood education to further achievement outcomes for children (Chu, Glasgow, Rimoni, Hodis, & Meyer, 2013).

There is a noticeable gap in the literature with regard to Māori and Pasifika theory and practice in early childhood provision. Despite a reasonably extensive array of literature on Māori and Pasifika images of the child, childrearing, and education, there is very little on infants and toddlers and even less that provides understanding, framings, and guidance for contemporary mainstream early childhood service provision. This project aimed to address this gap. It explored how early childhood services could better integrate culture into teaching practices by creating culturally located teaching and learning theory, and practice guidelines for early childhood services. The overall aim of the project was not only to support culturally embedded infant and toddler provision in Māori and Pasifika early childhood services, it was to provide culturally relevant theory and practice for all early childhood teachers and services.

While teachers want the best for their students, achieving this is a complex process. One of the reasons mainstream early childhood services fail to meet the needs of Māori and Pasifika children, according to Bevan-Brown (2003), is that teachers are unaware of the role culture plays in learning and therefore lack understanding of how to address culture within their teaching. Key to educational success for Māori and Pasifika children is the acknowledgement that Māori and Pasifika children are culturally located and the recognition that effective education must embrace culture. Being Māori, Samoan, Cook Island, or of any other Pasifika nation is a critical aspect of education.

This idea is congruent with Ka Hikitia—Managing for Success (Ministry of Education, 2009), which emphasises the importance of education that is responsive to the identity, language, and culture of Māori learners. The key message is that learners achieve more in education when the education provided builds on what they are familiar with and when it reflects and positively reinforces who they are, where they’re from, what they value, and what they already know. The Mid Term Review of Pasifika Education Plan 2009-2012 Ministry of Education, (2011) similarly acknowledges family, strong identities, multiple worlds, language, and culture as significant factors in ensuring successful outcomes for Pasifika learners. Success in education is about positively harnessing Māori and Pasifika worldviews within an enabling education system that works for children, their families, and communities. This is especially relevant when one recognises the increasing participation rates for Māori and Pasifika children, who make up nearly two-thirds of the increased numbers of children who were enrolled in early childhood services between 2010 and 2013 (Ministry of Education, 2014), and that the huge majority of these children attend mainstream services.

Research question

How can Māori and Pasifika cultural knowledge support the development of culturally responsive theory and practice for the care of infants and toddlers in contemporary early childhood settings?

Sub-questions

- What traditional Māori and Pasifika cultural knowledge can be reclaimed as a basis for contemporary infant and toddler practice?

- How can traditional Māori and Pasifika cultural knowledge be reframed to provide new theory and practice for contemporary infant and toddler education?

- What will reframed traditional Māori and Pasifika cultural knowledge look like when implemented (realising) with infants and toddlers in contemporary early childhood services?

Description of research

The research employed a qualitative, Kaupapa Māori, Pasifika research methodology that situated Māori and Pasifika understandings as central to the research design, process, analysis, and intended outcomes (Lee, Pihama, & Smith 2012). It promoted communities working together, sharing power, and affirmed the importance of relationships within the research process.

Grounded theory provided the theoretical frame for data gathering and analysis. Grounded theory involves simultaneous data gathering and analysis in an iterative process (Charmaz, 2005). It involves developing increasingly abstract ideas about the “participant’s meanings, actions, and worlds and seeking specific data to fill out, refine, and check the emerging conceptual categories” (Charmaz, 2005, p. 508). An important aspect of grounded theory is the emergence of themes (Mutch, 2005). Through thematic analysis it is possible to concentrate on identifying themes or patterns from the data in order to support meaning making and understanding (Welsh, 2002). A number of types of data were gathered during the research including: pūrākau; kaiako reflections and evaluations; kaiako focus group interviews; whānau feedback/comments; tamariki feedback; photos and children’s assessments.

A case study approach was utilised to support each of the six services—three Māori, one Samoan, Tokelau, and Cook Islands—to develop their own locally constructed understandings, theory, and practices of infant and toddler care and education. Each service worked through three phases of research:

1. Reclaiming traditional knowledge and understandings

This phase of the research involved each service gathering pūrākau/stories on traditional caregiving practices and understanding, rites, relationships, and teaching and learning for babies and young children, from their communities.

2. Reframing the reclaimed knowledge and understandings for contemporary contexts

The second phase involved analysing the pūrākau and identifying key themes, understanding, and beliefs to frame each service’s research question, interventions and strategies, data collection and analysis methods. An important understanding in this phase was that not all practices could be reframed; however, the values that underpinned practices may have significance for contemporary early childhood contexts.

3. Realising the reframed knowledge and understandings in local early childhood contexts

This phase involved each service utilising an action research cycle to plan, implement, and evaluate pedagogical interventions and strategies to answer their research questions.

Findings

Common themes that emerged from pūrākau across the services, in the first phase of the research, included:

- Communal caregiving: Communal childrearing responsibilities within extended families/whānau/aiga, was one of the major themes that emerged from all the services. Many kaikorero/interviewees recalled guidance from elders, aunties, uncles, grandparents, siblings, and cousins.

- Intergenerational caregiving: A large number of pūrākau described the role of grandparents in childrearing. Intergenerational caregiving was important to the transmission of knowledge, culture, and traditions to future generations.

- Tuākana/tēina: Another key caregiving practice identified across services was tuākana/tēina, with older siblings or cousins taking responsibility for feeding, bathing, nurturing, and sleeping with the infants. As a consequence, strong enduring relationships were forged between siblings.

- Tūrangawaewae/ahikāroa: The importance of maintaining iwi/hapū/rohe, nation connections so that young children developed a strong sense of belonging and identity, knowing who they were and where they came from was a recurring theme in pūrākau.

- Hikihiki pēpi: Many pūrākau included examples of carrying babies on the hip or back as adults and children went about their day. Carrying babies ensured the development of strong bonds with whānau.

- Religion and spirituality/karakia: The importance of spirituality, karakia, and religion was a major theme throughout all services’ pūrākau. Religious activities were woven into the fabric of daily family life, with spirituality, karakia/prayers, bible readings a daily occurrence, and church attendance, involving children from an early age.

- Waiata and song: Kaikōrero referred to being immersed in cultural practices, exposed to conversations, early morning waiata, oriori, mōteatea, and karakia, as well as traditional recitations in the process of waking and sleeping. This established roles and responsibilities, knowledge of whakapapa, tribal connections, and a strong sense of belonging and identity.

The case study services

The pūrākau from each of the participating services supported the identification of key themes, the defining of research questions, and findings.

Te Puna Whakatupu o Raroera Te Puawai. The place and use of wai/water within specific contexts, and importance of the Waikato river to the people of Waikato Tainui, were reoccurring themes from the service’s pūrākau. Analysis of the pūrākau resulted in a research question that asked how understandings of, and practices associated with, wai could be utilised to support the mana/strength and power of infants and toddlers, which was also a theme evident in the pūrākau. The research findings highlighted that the mana of infants and toddlers could be strengthened through the development of understandings and practices associated with wai and was demonstrated when infants and toddlers: used wai to self-regulate, to whakaāio/calm, and whakahohe/ energise; were able to physically and intellectually communicate their hononga wairua/spiritual connectedness, understanding of and whakapapa to wai, Waikato awa/river and the ua/rain; and when they engaged in wai experiences where they were able to affirm, support, and lead others.

Te Puna Whakatupu o Whare Amai. A key theme that emerged from the service pūrākau related to relationships with people and place. As stated earlier, the pūrākau highlighted tuākana/tēina relationships as a key caregiving practice, across all services, with many examples of this relationship in action. The service research question brought together these concepts and asked how the tuākana/tēina relationship could be enhanced through connectedness with mana whenua. Findings from the service emphasised that cultural practices, values, and understandings associated with mana whenua enhanced tuākana/tēina relationships when tamariki: were familiar with and took the lead in tikanga Māori, cultural practices, routines, and rituals related to mana whenua within the setting; took responsibility for themselves and others, showing manaakitanga, aroha, and tiaki; observed, copied, and felt empowered to have a go at activities, routines, and cultural practices such as pepeha, karakia, waiata; and were confident to ask for support, and understood they would receive it.

Te Puna Whakatupu o Ngā Kākano o te Mānuka. Pūrākau from the service’s community highlighted the use of traditional waiata, mōteatea, oriori, and karakia to help babies establish their identity, roles, and responsibilities. The research question asked how the rangatiratanga/leadership competencies of infants and toddlers could be embraced and enhanced through mōteatea. Research findings indicated that mōteatea could be used in a number of ways to enhance and embrace the rangatiratanga of infants and toddlers, including being: used as a waiata to soothe, calm, invigorate, and support; used as an assessment tool highlighting the aspirations of the mōteatea words; utilised as Reo Rotarota/sign language by kaiako, tuākana, and sometimes teina to support positive tuākana/teina behaviours; and being woven through all aspects of the service programme by kaiako and tamariki.

Te Punanga o Te Reo Kuki Airani. A strong theme that emerged from the pūrākau related to traditional caregiving practices and ways infants were connected to their culture and identity, including how pareu (wraps/lavalava) were utilised to nurture the child. The research question focused on how pareu could be used to support and enhance infants’ relationships with and sense of identity as Cook Islands Māori. Findings indicated that pareu was an important cultural artefact that could be used in multiple ways to reflect cultural identity and practices. These included being utilised: to settle, care for, and comfort children; across play activities, increasing sociodramatic and imaginary play; to implement traditional caregiving practices Ko’u ko’u/wrapping; and to support tuākana/tēina relationships, role modelling cultural care giving practices and knowledge.

Matiti Tokelau Akoga Kamata. The practice of sharing resources was a key theme that emerged from the pūrākau as was the importance of children developing a Tokelau identity and sense of belonging. The research question that was developed based on these ideas focused on how the Tokelauan valued practice of Inati (system of sharing and caring of all in the community) could be nurtured with infants and toddlers, using natural, language, and community resources. It was found that the implementation of Inati increased cultural practices for infants and toddlers through: increasing teachers’ confidence and enthusiasm for implementing and strengthening cultural practices, empowering teachers to reinforce Tokelauan values and ways of being; increasing community involvement and contributions has strengthened Tokelauan cultural values, practices, and created a rich cultural learning environment for children; children’s identities as Tokelauan have been reinforced, along with their sense of belonging as children of Tokelau; increasing the use of natural resources there with less likelihood of children fighting over resources as there are more to share; and replacing the plastic toys with natural resources has helped to create a calming environment for children and the centre team.

A’oga Amata Ekalesia Faapotopotoga Kerisiano Samoa (EFKS). Themes evident in the pūrākau included the pivotal role that aiga/family play in caring for infants and toddlers, intergenerational relationships with grandparents, and tuākana/tēina relationships and notions of alofa (love) and the cultural significance of this concept. The themes informed the research question which asked how expressions of alofa (love) and gagana (language) could demonstrate notions of Fa’a Samoa (Samoan ways) for fanau (extended family and community), aiga (family), and tamaiti (children). Findings from the research emphasised that expressions of alofa and gagana Samoa can be extended for children when: children recognise their own lullabies; children’s personal lullabies are used to soothe them when unsettled or to help them rest and sleep; aiga contribute their knowledge and provide input into the programme around lullabies; there is an increased use of lullabies with infants in their own homes; and language and picture charts strengthen cultural practices and language development.

Te Puna Whakatupu o Raroera Te Puāwai

Te Puna Whakatupu o Raroera Te Puāwai is situated on Te Wānanga o Aotearoa (TWoA) campus in Te Rapa, Hamilton. It caters for children of TWoA staff, students and the wider community. Te Puāwai can be translated as to ‘blossom’ which is an expression of the ways in which children learn and grow. The service’s vision statement ‘Kia rangatira te tū a ngā tamariki mokopuna’ focuses on children standing strong. The tikanga of Tainui and the Kīngitanga are integral to the puna operation.

Key themes from pūrākau

A number of themes emerged from the puna pūrākau. A particular theme that emerged from the puna rohe was that whānau/community related to the importance of wai/water in all its forms to the people of Waikato Tainui. Pūrākau highlighted:

- the significance of water in the education and development of pēpi and tēina. This was reflected in practices such as whakarite or spiritual and physical cleansing, and interactions with Ranginui/Sky Father

- the centrality of the Kīngitanga to Waikato/Tainui

- the need to recognise the Waikato awa/river as a tūpuna. Acknowledging its importance to the people of the rohe, and taking responsibility for its ongoing wellbeing.

Every time you go into the water, I knew I had to (whakarite) because Nana and Koro always did that … We do that because of the Kings … like a karakia or showing respect to those who have passed on. I really love that awa. It’s a tūpuna. It’s spiritual and physical, and there’s a lot of history along our awa, so, it’s always respected.

Action research question

How can understandings of and practices associated with wai koiora strengthen the mana of infants and toddlers?

Pedagogical strategies

A number of strategies were instigated to develop greater understanding of wai koiora, implement practices utilising wai koiora, and strengthen relationships with the Kingitanga/Waikato/Tainui. These included:

- Whakarite—the practice of whakarite, utilising water and karakia to physically, spiritually, and emotionally heal and support wellbeing, was a key strategy instigated by kaiako. It involved placing the ‘oko wai koiora’ or water bowl in a central place within the centre and encouraging toddlers to sprinkle water on themselves when feeling sad, lonely, or hurt

- Wai Māori—encouraging infants and toddlers to experience the ua/rain (tears of Ranginui), to support physical and spiritual connectedness with wai, thus strengthening their mana; retelling the creation story and making links to Ranginui and Papatūānuku

- Haerenga—taking small groups of toddlers on trips to Waikato awa; acknowledging tūpuna/ancestors, children’s whakapapa, and spiritual connections to it

- deeply embedding the Kīngitanga in the service through mōteatea, waiata, karakia, pūrākau, and pakiwaitara and pepehā to develop infants’ and toddlers’ understandings of the importance of the Kīngitanga to Waikato/Tainui and the community.

Examples of data gathered

The following reflections and comments exemplify the ways tamariki were encouraged to engage with ‘wai koiora’ and the growing understanding and recognition of the spiritual power of wai by kaiako, whānau, and tamariki.

Te Oko Wai Koiora

|

|

Our pēpi has been upset and crying. She is guided to the Oko Wai Koiora where a kaiako sat beside her. A few flicks of wai on her head and she has become settled. The kaiako steps back to observe her further as she continues to stroke her face with the wai before returning outside.

Ko Te Mana O Te Wai, Ki Te Whakamana Te Mokopuna

Hami, you have been having so much fun in the ua. Splashing in a puddle gave you so much joy. You came over to me; taking my hand you led me to the puddle encouraging me to splash with you. Ngā mihi ki a koe Hami.

|

|

You expressed feelings of peacefulness and seemed awestruck by nature’s influences. While also feeling happy and a sense of belonging in the world you are empowered and connected to your tīpuna using the space between Ranginui and Papa-tu-a-nuku.

A mother’s comment highlights whānau understanding of the importance of wai in connecting tamariki to their physical and spiritual environment.

When I heard the heavy downpour today and then the thunder and lightning … I imagined that you were all enjoying and making the most of the experience. Thank you for supporting our tamariki to have meaningful experiences with our environment—Atua Māori!

Kaiako reflections highlight the importance of recognising the connectedness of the physical and spiritual worlds.

The tēina are reacting in different ways depending on how wai is presented to them, very loud and active when out in the rain, but settled when it’s presented calmly. Tēina are gaining understandings and taking the lead in offering wai to others to remedy sadness and sickness. They are beginning to talk about Papatūānuku, Ranginui and the rain that falls. Tuākana are often taking the lead in providing guides for tēina in terms of behaviours, caring and sharing, and modelling. Whānau have made comments about their children talking about wai at home and their understandings of the power of wai. Some parents are carrying the practices on at home as there is growing understandings and recognition of the spiritual power of wai for the child. (Kaiako reflection)

What we found is that there’s a need to be a connection, a physical connection, a spiritual connection, between the child and the wai … physically they are going to get mākū/wet but there is more to it. And that’s what makes it powerful … the strength of wai, for tamariki. (Kaiako focus group reflection)

Service findings

Kaiako found that the understanding of and practices associated with wai koiora could strengthen the mana of infants and toddlers when tamariki were able to:

- use wai to self-regulate, to whakaāio/calm and whakahohe/energise

- physically and intellectually communicate their hononga wairua/spiritual connectedness, understanding of and whakapapa to wai, Waikato awa, and ua

- engage in wai experiences where they were able to affirm, support, and lead others.

This required that kaiako:

- step back and allow infants and toddlers the freedom to engage with wai, in their own way. It involved viewing infants and toddlers from a Māori perspective, treating them as capable and competent beings, and trusting in their inherent abilities, handed down from tīpuna/ancestors

- develop understandings the connectedness of the tamaiti Māori to the spiritual and physical worlds (Ira Atuatanga) and implement practices that supported this ongoing relationship

- develop understandings of the Māori worldview and implement practices that strengthen this in their practice.

Te Puna Whakatupu o Whare Amai

Te Puna Whakatupu o Whare Amai was established in 2012. It is situated on the TWoA campus, Whirikoka in Gisborne. The majority of children attending the puna have whakapapa connections to the many iwi of the rohe and the whānau of the children are predominantly students or past students of Te Wānanga o Aotearoa.

Key themes from pūrākau

Key themes that emerged from the puna pūrākau were particularly centred on relationships, or connectedness with rohe/place and people, more specifically tuākana/teina relationships. They highlighted:

- the importance of returning to tūrangawaewae/place to stand regularly to ensure the ahikāroa/home fires were not extinguished. This linked to te ‘hau kainga’ and cementing connections and birth rights

- the importance of relationships, more particularly tuākana/tēina relationships, roles, and responsibilities and the reciprocity of care and learning inherent within these relationships.

… my older brother … a toddler himself, was the one who had looked after me while my mother and father worked on my grandfather’s garden patches. He raised and cared for us younger siblings. He would feed, clothe, hold and carry me around and change my nappies. Tuākana tēina system, awhi atu awhi mai.

Action research question

How can we enhance tuākana/tēina (more knowledgeable or expert person/less knowledgeable or expert person) relationships through mana whenua?

Pedagogical strategies

After consultation with whānau, kaiako focused on implementing the following mana whenua strategies aimed at enhancing tuākana/tēina roles and relationships. These included:

- utilising regular events and routines such as wā whāriki/mat time to encourage support and normalise tuākana/ tēina relationships and responsibilities in authentic, meaningful ways

- ensuring that practices of tuākana/tēina relationships were underpinned by whānau/iwi/hapū specific karakia, waiata, pūrākau, and tikanga

- recognising the Māuī connections, and integrating Māuī pakiwaitara into the programme—art, waiata, storytelling, and drama—and enhancing whakapapa links to the rohe and iwi

- utilising preparation for the Tairawhiti Kapahaka Festival to further implement tuākana/tēina understandings in relation to mana whenua

- acknowledging, valuing, and further encouraging tuākana/tēina relationships and practices that occur naturally and normally in the service

- developing a framework to assess tuākana/tēina strategies.

Examples of data gathered

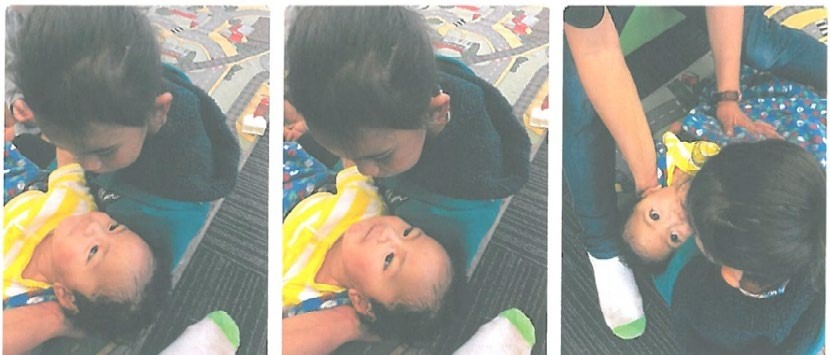

Some tuākana/tēina relationships and responsibilities being enacted in the service were planned teacherinitiated activities that aimed to embed tuākana/tēina practices in everyday routines. Here are three examples of this.

Horoi ō ringa

Time for afternoon tea. Each tuākana takes a pepi by the hand and leads them to the washbasin. TWT takes PK’s hand and walks him to the basin. TWT rolls up PK’s sleeves and feels the water to make sure that it is not too hot. She then places his hands under the tap and turns them over using the soap to make sure that they are clean. When that is done, she turns the tap off and gets two pieces of paper to dry his hands, placing them into the rubbish bin when she has finished. PK watches her intently, following her every move. TWT once again takes him by the hand and leads him to the table, making sure that he is seated properly.

The next story highlights ways that WMWS’s natural desire to show affection and love is fostered, valued and further supported by teachers and whānau.

WMWS Loves the Pepi

WMWS is so good with the babies of Whare Amai. He is so caring and very careful near and around all the babies. He really cares about our potiki, AT, he has to come and mihi to him and give him a kihi every day—ka nui te aroha ki aia WMWS! AT recognises you now and had a smile when you come close.

A comment from WMWS’s mother emphasises the value his whānau place on manaakitanga and tuakana/teina practices.

Wow my baby! You always show a caring heart to the babies. That is the role of the tuākana. Well done my baby! (translated)

Māui and the Stingray

|

|

WS made a stingray and drew stingray on the concrete to play Māui fishing up the North Island. He then told the other children about the story of Maui, his waka and the stingray. This pakiwaitara has significance for Ngāti Porou as they descended from Māui. Through telling the pakiwaitara to the teina, WS shares his understandings about living, walking and standing on the stingray, on Māuis stingray, with his peers and teina. The shared understanding of this further builds collective identity.

Children are becoming more knowledgeable about the Māui pakiwaitara, and the links to Te Tairawhiti and Ngāti Porou. They talk about Māui and his achievements throughout the day in different activities. Tuākana are also becoming more aware of their roles in supporting tēina participation in activities, and are reflecting these roles and responsibilities in their interactions with tēina. Parent feedback has been very supportive with information being shared by parents on their connections and knowledge of the pepeha and pakiwaitara. (Kaiako reflection)

Service findings

Kaiako found that tuākana/tēina relationships were enhanced through mana whenua when tamariki:

- took responsibility for themselves and others, showing manaakitanga, aroha, and tiaki

- were familiar with and took the lead in tikanga Māori, cultural practices, routines, and rituals from mana whenua within the setting

- took the lead to guide, support, care for, and show love to others

- observed, copied, and felt empowered to have a go at activities, routines, and cultural practices such as pepeha, karakia, waiata

- were confident to ask for support and understood they would receive it.

In order for these tuākana/tēina activities to occur, kaiako were required to:

- reclaim Māori worldviews through reinterpreting/deepening their teaching practice, including understandings about how to best support tuākana/tēina, mana whenua, and cultural practices

- recognise, value, and support the capacity of tuākana/tēina to care, nurture, and to take the lead

- establish routines and regular occasions where tuākana/tēina practices, relationships, and learning were discussed, encouraged, and normalised

- recognise that the learning in this relationship is collective, reciprocal, and ongoing.

Puna Whakatupu o Ngā Kakano o Te Manuka

Situated next to TWoA, Manukau campus in Mangere, Auckland, Te Puna Whakatupu o Ngā Kakano o Te Manuka caters for children from the local community as well as from the students and staff of TWoA.

Key themes from pūrākau

A key theme that emerged from the puna pūrākau related to the fact that many of the puna whānau/ community did not whakapapa to the mana whenua of the rohe and the importance of tamariki developing a sense of iwi connectedness, identity, and belonging. Pūrākau highlighted:

- the importance of tribal connections and the need for children to learn who they are and where they are from. This is especially relevant in Auckland where most people do not have whakapapa connections to mana whenua

- utilising waiata—mōteatea, oriori, and karakia—with babies to help establish their identity, roles, and responsibilities, as well as their tribal connections and sense of belonging as ngā hau e wha/people of the four winds.

It is through waiata that I have been able to teach my children about who and where they come from. It is through waiata and haka I have been able to establish confidence in them, all at the same time having fun.

Action research question

How can the rangatiratanga/leadership competencies of pēpi/tēina be embraced and enhanced through mōteatea?

Pedagogical strategies

A range of strategies were utilised to embrace and enhance rangatiratanga competencies utilising mōteatea, including:

- creating āhurutanga/warm/caring relationships with whānau/tamariki, supporting whānau/tamariki in linking with mana whenua at the puna

- composing a puna mōteatea that focused on acknowledging and supporting leaderful dispositions such as those that were displayed by chiefly tūpuna of the mana whenua

- translating mōteatea into te reo rotarota (sign language) for all children to learn and use

- utilising the mōteatea daily for a range of purposes, including to: calm, support relaxation and comfort; settle at wā moe/sleep time; aid daily transitioning; transition new children into service; energise and invigorate the tamariki, utilising poi and haka.

Examples of data gathered

Although the mōteatea was utilised in a number of ways, one of the most beneficial for tamariki was as a soothing, calming, or resting approach. This was sometimes initiated by kaiako but often by tamariki as demonstrated in the example below.

AT

|

|

Today after lunch, you were keen to go outside and enjoy the sunshine. However, after a few minutes you looked tired. You stood in front of me rubbing your eyes, so I cuddled you and chanted our Mōteatea in a soft gentle voice. As you heard the Mōteatea you lay down on my lap quietly, head on my chest and you held my hands tightly while watching other tamariki playing. The Mōteatea is a source of comfort and soothing for AT when he’s tired. As he heard the Mōteatea he found rangimarie (peacefulness) on his tinana (body), wairua (spirit), and hinengaro and lots of AROHA.

Ko Te Mōteatea: In Action

Kaiako reflections on ‘what’s happening here’ highlight the role of kaiako, to bring the mōteatea to life with and for tamariki.

A kaiako sits with a small group of pēpi engaging with them and offering help when required. All the while, she chants the mōteatea to the tamariki. Slowly, weaving an invisible thread of trust around them. Reassuring them of her nearness and of knowing that they are safe in this space. The mōteatea supports the tamariki to make connections. This is where they begin to hear the pulsating beat of ‘te Ao Māori’. (Kaiako reflection)

Kaiako reflections also emphasise tamariki learning of and from the mōteatea.

Tēina are becoming more familiar with the mōteatea and what is expected of them when the mōteatea is chanted. Tēina are beginning to sing the mōteatea, sway when it is being sung, and have growing sense of ‘ownership’ of the mōteatea. Tuākana have also become familiar with the mōteatea and are joining in or initiating the mōteatea, supporting tēina when needed, correcting wording, providing correct signing and modelling appropriate behaviours. Feedback from whānau has been hugely positive with whānau loving what is happening for their tamariki in the service. (Kaiako reflections)

Tēina are role-modelling mahi a ringa/sign language for the mōteatea. Children respond by swaying to chanting, humming, and being comforted by the mōteatea. They also recognise that the mōteatea may cue the tēina about times for sleep or rest or can support them when upset and tired. The importance of mōteatea as an assessment tool in the service is continually evident and continues to evolve. There has been a strong emphasis put on tuākana/tēina discussing and reflecting on each line of the mōteatea, what the lines mean and the implications for the research and teaching practice. (Kaiako reflections)

Service findings

Kaiako found that mōteatea could be used in a number of different ways to enhance and embrace the rangatiratanga of tamariki, such as through being:

- used as a waiata by kaiako, tuākana, and sometimes tēina to soothe, calm, invigorate, and support

- an assessment tool that kaiako can utilise to ascertain tēina learnings and development as rangatira, highlighting the aspirations of the mōteatea words

- utilised as Reo Rotarota by kaiako, tuākana, and sometimes tēina to support positive tuākana/tēina behaviours

- woven through all aspects of the service programme by kaiako and tamariki. Each line of the mōteatea has been discussed and examined in relation to what it means for tamariki and how the meanings of the words are being reflected in practice.

Te Punanga o Te Reo Kuki Airani

Te Punanga o Te Reo Kuki Airani is located in Newtown, Wellington. The children and family in the centre are drawn from a diverse range of cultures and backgrounds that comprise the local community. The Punanga opened in 1983 as the first Cook Islands Māori language nest in New Zealand. It promotes Cook Islands Māori language, culture, and identity.

Key themes from pūrākau

A strong theme that emerged from the pūrākau related to traditional caregiving practices and ways infants were connected to their culture and identity. Pūrākau described:

- traditional healing practices such as ‘Maoro’ (massage), connections to the enua (land), oral storytelling, and naming of infants, tuākana/tēina as caregiving practice

- swaddling the child with a pareu (wrap), and the practice of ko’uko’u to nurture the child

- oral storytelling and naming of infants, tuākana/tēina as caregiving practice.

Through swaddling the child and holding them close we surround our children with nurturing care and love.

Research question

How can Pareu (wrap/lavalava) be utilised to support and enhance infants’ relationships with and sense of identity as Cook Islands Māori?

Pedagogical strategies

Strategies utilised by kaiako to strengthen infants’ abilities to relate to and develop a sense of being Cook Islands Māori focused on pareu. Strategies included:

- creating pareu for each child to support identity and relationships

- encouraging and strengthening tuākana/tēina relationships to encourage children to identify with the pareu, through using in play and to comfort the younger children

- using pareu to comfort and settle, and to wrap the infants before sleep

- using pareu in a range of ways in the curriculum to support social and creative learning

- using pareu as a connecting link to strengthen relationships with parents and families

- developing posters of pareu and pareu making in the service

- encouraging fanau to use the pareu at home.

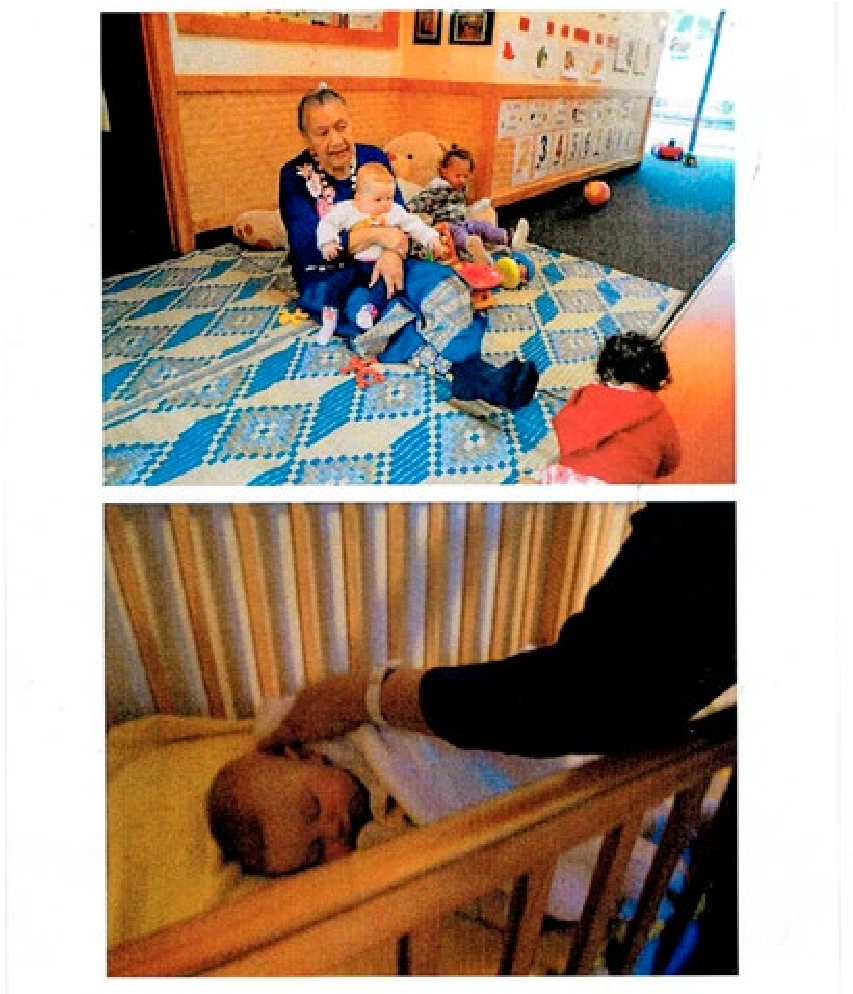

Examples of data gathered

Kaiako focused on the ways cultural artefacts such as pareu could be utilised authentically and meaningfully within the service to connect to traditional practices and values.

Moe, Moe, Leila

This morning I wrapped you snuggly in your pareu. You had been a bit unsettled and I gently gathered you up and gently rocked you, singing ‘Moe, moe pepe …’. You slowly closed your eyes and settled down to sleep in my lap. You looked so peaceful, sleeping there on my lap.

|

|

The children have been provided role modelling of wrapping and rocking babies to sleep. In the family corner, I notice Tiana has her doll wrapped in her pareu blanket and is gently rocking her off to sleep. She notices the patterns on the pareu material while holding and rocking the doll just as she has seen the Mamas do when putting babies to sleep.

Creating Pareu

We draped long lengths of cotton fabric around the tables outside. The children chose their colours and designs on the fabric, making their individual pareu. Some were painted. When they were finished we hung them out to dry.

|

|

Using the individual pareu has helped in settling the children. The older ones, the tuākana, know the pareu of the younger children and offer these to the tēina to settle them. It has affirmed the Cook Islands practice, to know that this traditional practice is used with our pepe. Taking it into the play context with dolls and further strengthening and normalising the cultural aspect. (Kaiako reflections)

Service findings

Pareu can be utilised to support and enhance infants’ relationships with and sense of identity as Cook Islands Māori when:

- kaiako and tuākana utilise the pareu to settle, care for, and comfort children

- children make and can identify with their own individual pareu in the centre and at home

- children can use pareu across play activities, increasing socio-dramatic and imaginary play

- tuākana/tēina relationships are developed with children role modelling caring for each other

- whānau cultural practices and knowledge are affirmed by implementing traditional caregiving practices (Ko’u ko’u).

Matiti Tokelau Akoga Kamata

Situated in the Hutt Valley, Matiti Tokelau Akoga Kamata is a Tokelauan language nest that caters for Tokelauan children and families as well as families from the wider community. It is located on the grounds of the local Catholic school and Catholic Church in Naenae, Wellington. The akoga was established by Tokelau community members to maintain children’s Tokelau language and cultural identity. Children attending the akoga are mainly from the Tokelau communities in Naenae and Lower Hutt.

Key themes from pūrākau

Themes that emerged from the pūrākau highlighted the importance of sharing resources and the importance of developing a Tokelau identity and sense of belonging:

- the use of Tokelauan natural resources in the environment to support and enhance cultural connectedness, belonging, and identity to Tokelau Islands

- the involvement of the wider Tokelauan community in Aotearoa and Tokelau

- the cultural practices of ‘Inati’ (sharing). Upon birth the child’s inati, or share, is given to an elder, such as a grandparent to help care for the wellbeing of the elder.

In our beliefs and culture we nurture our little ones as a family, we are all responsible, and share in their caring…

Research question

How can we nurture the Tokelauan valued practice of Inati (system of sharing and caring of all in the community) with our infants and toddlers, using natural, language, and community resources?

Pedagogical strategies

A wide range of strategies were implemented to nurture Inati with infants and toddlers. Most involved the support and involvement of the community, and included:

- utilising the range of resources—language resources of the teachers, cultural and natural resources donated by parents, teachers, and families

- developing the physical environment to represent Tokelauan practices—mats on floors and use of natural materials for children

- extensive community involvement in gifting resources such as tapa cloth, and shells, and providing support to develop the environment—painting, gardening, and sharing their time with the children

- developing a fanau board displaying children’s ancestors, placed prominently in the entranceway of tīpuna bringing in the spiritual element of Inati

- inviting parents to spend time to share their expertise

- sharing songs and stories of Tokelau.

Examples of data gathered

Much of the data gathered focused on the sharing of time and resources.

Falai Elegi with Soko (Fried Mackerel with Chokos)—Inati in Action

One of the parents made a gift of chokos to the centre, from a friend’s garden. Mele decided to use some of the choko to make a Tokelauan dish. Staff contributed other ingredients for the dish—two tins of mackerel fish and an onion. All of the children joined in cutting up the chokos. The dish was served with rice and shared among all the children and staff at the centre for lunch. A lotu was done to bless the food and those who prepared it.

The image below shows a father sharing his knowledge and time in the service.

Antoni, a young father, feels strongly that children should be encouraged to learn the traditional values of respect, trust and love. He demonstrates sharing his knowledge reading stories and storytelling to help them to learn the Tokelau language, and to build confidence to speak and communicate in Tokelauan.

This morning the toddlers gathered together on the new woven mat that had been placed on the floor. We replaced the high chairs and tables with hand woven Tokelau mats for our children’s mealtime, playtime and sharing time (akoakoga). We encourage our infants and toddlers to eat together on the mat with the teacher. It is a traditional practice of ‘Inati’, sharing our meal together, passing the plate and caring for each other.

Eleni and Pani were enjoying exploring the new resources. They first tried the round cones (pate, or whau) on their heads. They walked around with these on their heads making funny noises and laughing and smiling at each other. Eleni picked up a whau and placed it on Pani’s head. She started to laugh.

Later they moved to the low shelf which had a lot of shells and natural materials such as drift wood parents had brought in. Eleni picks up the driftwood and shakes it around with Pani watching from the floor. Eleni bends down and passes the driftwood to Pani—great sharing Eleni—you are showing your alowha (love) and kindness to Pani.

Strengthening our Tokelauan culture has been such a good thing for us. It has made us proud and the community are very pleased to share their Inati. Even the priest has given us shells from Tokelau for our centre. (Teacher reflection)

Service findings

The implementation of Inati has increased cultural practices for infants and toddlers through:

- teachers’ increased confidence and enthusiasm for implementing and strengthening cultural practices. They have been empowered to reinforce Tokelauan values and ways of being

- increased community involvement and contributions have strengthened Tokelauan cultural values, practices, and created a rich cultural learning environment for children

- children’s identities as Tokelauan have been reinforced, along with their sense of belonging as children of Tokelau

- increasing the use of natural resources there with less likelihood of children fighting over resources as there are more to share

- replacing the plastic toys with natural resources has helped to create a calming environment for children and the centre team.

A’oga Amata Ekalesia Faapotopotoga Kerisiano Samoa (EFKS)

A’oga Amata Ekalesia Faapotopotoga Kerisiano Samoa Newtown Early Childhood Service is a Samoan bilingual centre, located in Newtown in Wellington. It is situated on EFKS church grounds and has a strong connection to the church. It provides a bilingual Samoan English programme to a diverse cultural community group. Children are immersed in a welcoming gagana Samoa context.

Key themes from pūrākau

- The pivotal role that Aiga play in caring for infants and toddlers, intergenerational relationships with grandparents, and tuākana/tēina relationships are significant.

- Notions of alofa (love) and the cultural significance of this concept emerged strongly.

These themes informed the research question which is:

How can expressions of alofa (love) and gagana (language) demonstrate notions of Fa’a Samoa (Samoan ways) for fanau (extended family and community), aiga (family), and tamaiti (children)?

Pedagogical strategies

Strategies enacted to answer the service questions included:

- expressing alofa through carefully chosen lullabies, to demonstrate care and consideration for each infant and toddler

- giving time and showing care to the child in an unhurried way to support emotional wellbeing

- cradling and singing softly to each child to sooth them to sleep

- introducing infants to traditional lullabies that may allude to Siapo (cultural items) and cultural perspectives on life

- learning rhythm and expression in singing through lullabies and the cadences of Samoan language. In this way, the child learns now words and phrases and ways to respond appropriately • personalising lullabies to develop and create language experiences

- developing language resources of lullabies in a large chart/booklet.

Examples of data gathered

The examples of data gathered below highlight the role of singing and lullabies to express love and strengthen the Samoan language.

Teresa carefully holds Pepe on her lap quietly singing his lullaby. Pepe is very relaxed even though it is time for his sleep. -Teresa continues to hold and rock Pepe whilst singing the lullaby. Slowly he nods off to sleep and Teresa places him to bed in his cot, all the while singing his lullaby to soothe as he settles himself to sleep in his cot. Another two infants sitting close by listen in to this calming episode.

On the ‘Samoan language’ mat there are baby dolls, clothing, bibs, baskets, and toys.

Teresa (teacher) joins the group. She begins to converse with the children and encourage them to engage in the lullaby singing. In the process, she is also weaving Gagana (Samoan language) into the learning episode.

O le a toe fai le tatou pese pese? (Shall we practise our lullaby?) Tasi, smiling happily and sitting down with her doll, ‘yes, yes’.

Teresa asks the group. ‘Tou te manatua le tatou pese fou sa a’o I le vaiaso ua te’a? Fa’alogo mai outou failele.’ ‘Do you remember our new lullaby ‘listen new mothers’? We practised it last week.’ Tasi ‘Falaogo.’ Smiling to herself.

Teresa Va’ai ‘upu ia, ma mulimuli mai ia te a’u. (Look at the first line and follow me.) Mara holds the charts.

Teresa leads with ‘Fa’alogo mai. Your turn.’

Children repeat ‘Fa’alogo mai.’

Teresa ‘Outou failele.’

Children ‘Outou failele.’

Teresa ‘E fa’apenei ona tausi le pepe.’

Children ‘E fa’apenei ona tausi le pepe.’

Teresa sings ‘La lelei, tou te fia usu i le moe, ‘oe pepe.’

Service findings

The expressions of alofa and gagana Samoa have been extended for children when:

- children recognise their own lullabies

- children’s personal lullabies are used to soothe them when unsettled or to help them rest and sleep

- aiga contribute their knowledge and provide input into the programme around lullabies

- there is an increased use of lullabies with infants in their own homes

- language and picture charts strengthen cultural practices and language development.

Key findings from the research

While there is no intention to develop a ‘one size fits all’ theory and practice framework to represent the perspectives/findings of all the services, a number of commonalities have emerged from the services that address the research questions.

Research question/s

- How can Māori and Pasifika cultural knowledge support the development of culturally responsive theory and practice for the care of infants and toddlers in contemporary early childhood settings?

Māori and Pasifika cultural knowledge can support the development of culturally responsive theory and practice through connecting with, and deepening understandings of, Māori and Pasifika worldviews, constructs of the child, and their whānau/communities.

- What traditional Māori and Pasifika cultural knowledge can be reclaimed as a basis for contemporary infant and toddler practice?

Traditional Māori and Pasifika cultural knowledge that can be reclaimed includes the cultural values, understandings, beliefs, and practices that reflect Māori/Pasifika worldviews. All the case study services identified the need to embed and normalise Māori/Pasifika worldviews within practice. This created a context whereby iwi/hapū/tīpuna/aiga, rohe/whenua/communities, and island/homeland connections could be maintained, enabling infants and toddlers to develop a strong sense of themselves, who they are culturally, and where and how they belong. This supported the establishment of roles and responsibilities, knowledge of whakapapa, tribal/nation/island connections, and a strong sense of belonging and identity.

- How can traditional Māori and Pasifika cultural knowledge be reframed to provide new theory and practice for contemporary infant and toddler education?

The services utilised a range of cultural tools/practices/artefacts to reframe cultural knowledge for contemporary infant and toddler education. This involved immersing infants and toddlers within environments where connections and relationships, inherent in whakapapa, shared intergenerational caregiving, and tuākana/ tēina partnership were embedded. Cultural practices such as waiata, oriori, mōteatea, and karakia were an important part of this process as was the integration of a range of culturally valued tools and artefacts such as pakiwaitara and pareu. Recognising and further supporting culturally valued traits, competencies, behavioural aspirations, and norms such as the expressing of alofa, mana, and rangatiratanga were important aspects of these environments.

- What will reframed traditional Māori and Pasifika cultural knowledge look like when implemented (realising) with infants and toddlers in contemporary early childhood services?

Reframed traditional Māori and Pasifika cultural knowledge will: reflect teachers’ connectedness to, relationships with, and understanding of learning valued by cultural communities within local contexts; be underpinned by elements of identity and belong within Māori/Pasifika communities; highlight Māori and Pasifika cultural tools, practices, and artefacts; and make a difference for Māori and Pasifika infants and toddlers. Whānau/kaiako/ tamariki experience an environment where:

- Māori and Pasifika culture and cultural knowledge/values/practices/beliefs are a taken for granted and are embedded within service provision

- connections with culture, families/whānau/aiga, and iwi/hapū/rohe, mana whenua/nation/tūrangawaewae are maintained and continually strengthened throughout the operation of the service

- infants and toddlers are supported to develop a strong sense of who they are and where they come from and where they belong within contemporary contexts.

Major implications for practice that derive from the findings

A major implication derived from the findings is that culturally responsive theory and practice entails early childhood teachers and professionals developing connections and relationships with, and understandings of, Māori and Pasifika worlds, families, communities, and children.

Most Māori and Pasifika infants and toddlers are in early childhood services where they are cared for by teachers who utilise predominantly Western principled lenses or frameworks of values, beliefs, and understandings of the world. Presently, Māori and Pasifika cultural values, understandings, and beliefs tend to be more a cultural overlay, a ‘veneer’, or ‘nice-to-have’ gloss, rather than integral to early childhood provision. In order to move beyond the veneer, changes in the lenses utilised by early childhood teachers, organisations, and institutions are necessary. These changes require that:

- Māori/Pasifika cultural knowledge and competencies be foregrounded in Initial Teacher Education, with a particular emphasis on cultural ways of viewing the world, values, and practices

- Māori/Pasifika cultural tools, practices, and artefacts be authentically and meaningfully implemented in early childhood services. This will require a deepening of teachers’ understanding and cultural knowledge, and respectful integration and implementation of strategies

- Māori/Pasifika culturally valued knowledge, beliefs, and traits be recognised as valid, valuable, and relevant, and be authentically integrated into programmes

- cultural practices and behavioural norms and expectations be recognised as inseparable elements of Māori and Pasifika worlds, to be modelled, encouraged, and valued

- cultural learning be acknowledged as an ongoing process of inculcation. It is therefore critical to create the appropriate context for cultural learning to occur.

Traditional Māori and Pasifika caregiving practices and beliefs around caring for infants and toddlers offer an important alternative to the dominant Western theory and practice that is prevalent in current early childhood regulations and provision. Māori and Pasifika whānau/communities are the storehouses of cultural knowledge and practices—the keepers of the history of the people. In order to access these practices and beliefs, early childhood teachers must recognise that:

- cultural worldviews are located within specific community contexts and the connections to whānau/ community and the land on which the service is located is critical

- whānau/community contributions are fundamental to the development of culturally located infant and toddler practices in early childhood

- kaiako must seek cultural expertise from those in the community to enable culturally located skills to be developed and embedded in practice.

Māori and Pasifika constructs of infants and toddlers differ in kind and emphasis from the Western constructs espoused and normalised in early childhood theory and practice. Key to providing culturally responsive early childhood provision for Māori and Pasifika infants and toddlers is the need for practices and pedagogies to be reflective of the children’s cultural worldviews, identities, protocols, and behavioural expectations. Key implications include recognition that:

- cultural traits, values, and competencies such as mana, rangatiratanga, and alofa are examples of valued learnings, skills, and attitudes for Māori and Pasifika infants and toddlers

- infants and toddlers are competent no matter their age, with inherent traits and characteristics inherited from ancestors

- culture is critical to Māori and Pasifika infants and toddlers’ identity development, sense of belonging, and their lifelong learning

- tuākana/tēina caregiving is a means of integrating a more collaborative approach to infant and toddler care and education, and is therefore a culturally responsive pedagogical approach

- tuākana/tēina caregiving is essential for optimal tēina and tuākana learning in early childhood services. Mixed-age early childhood settings encourage and are compatible with traditional/ tuākana/tēina caregiving practices

- kaiako foster tuākana/tēina relationships and abilities, by planning activities and events that promote its expression in the service, and stepping back and allowing the development of enduring bonds to develop. We argue that the role of the teacher needs to be reviewed and de-centred to allow a more collective caregiving regime.

Limitations of the project

The major limitation of the project is its generality. It provides a general overview of the six services’ work and their respective cultural worldviews. However, reporting on the services’ findings could not be deeply reviewed and reported upon. Most of the concepts and terms discussed in the research have deeper meanings and ramifications, which could not be articulated further in this report. More work is required to articulate each of the service’s findings in depth.

Conclusion

This research has revealed strong, interlinking connections to a common set of Polynesian values, knowledge, and practices for the Māori, Cook Island, Samoan, and Tokelauan communities participating in the study. Whilst the practices may differ according to context, there is a set of Polynesian principles that are clearly evident, embraced, and embedded in practice. These connections are recognised and strongly cherished by the respective communities in this study. In turn, this has served to further strengthen and affirm these important links to each other as Polynesian peoples, in Aotearoa and within Oceania.

Presentations and publications arising from the research

Publications

Glasgow, A., & Rameka, L. (2016). Māori and Pacific traditional caregiving practices: Voices from the community. In R. Toumua, K. Sanga, & S. Johanssen Fua (Eds.), Weaving education: Theory and practice in Oceania: Selected papers from the second Vaka Pasifiki Education Conference. (pp. 74-85) Suva, Fiji: University of the South Pacific.

Glasgow, A., & Rameka, L. (2017). Māori and Pacific pedagogy: Reclaiming cultural practices and countering Western bias. ICCPS Journal, 6(1), 80–95.

Rameka, L., & Glasgow, A. (2015). A Māori and Pacific lens on infant and toddler provision in early childhood education. MAI, 4(2), 134–150.

Rameka, L., & Glasgow, A. (2016). Our voices: Culturally responsive, contextually located infant and toddler caregiving. Early Childhood Folio, 20(2), 3–9

Rameka, L. K., & Glasgow, A. H. (2017). Tuakana Teina culturally located teaching in early childhood education. Early Childhood Folio, 21(1), 27–32.

Presentations and keynote addresses

Burgess, F., & Fiti, S. (2015, April). Using stories of traditional infant and toddler child rearing practices in order to direct observations of caring behaviour in a Wellington A’oga Amata. Paper presented at the 25th FAGASA conference, Apia, Samoa.

Glasgow, A., & Rameka, L. (2015). Māori and Pacific infant and toddler education: Community voices. [TLRI research]. Paper presented at RECE Reconceptualising Early Childhood Education, Dublin, Ireland.

Rameka, L., & Glasgow, A. (2015, May). Polynesian perspectives of infant and toddler care and education in early childhood education. Keynote address to the Autumn Research Seminar, Victoria University of Wellington, Wellington, New Zealand.

Rameka, L., Glasgow, A., Kauraka, B., Burgess, F., Fiti, S., Mansell, T. … Tuheke, A. (2015, May). Te whatu kete mātauranga: Weaving Māori and Pasifika infant and toddler theory and practice in early childhood education. Paper presented at the Early Childhood convention, Rotorua, New Zealand.

Glasgow. A. (2016, May). Beacons of light: The Pacific language nest. Paper presented at the Autumn Research seminar, Victoria University of Wellington, Wellington, New Zealand.

Tuheke, A. (2016, September). Understandings of and practices of wai koiora to strengthen the mana of infants and toddlers. Paper presented at the TWoA Te Waenga symposium.

Wills, C. (2016, September). Enhancing tuakana/teina relationships through pepeha and pakiwaitara and mana whenua. Paper presented at the TWoA: Takiwai Te Waenga, Rotorua, New Zealand.

Burgess, F., & Fiti, S. (2016, October). How expressions of Alofa and Gagana demonstrate notions of Fa’a Samoan for fanau, aiga and tamaiti. Paper presented at the Cultural Diversity Day, EFKS, Wellington, New Zealand.

Fiti, S., Iosefo-Perez, R., Perez, M., & Pereira, K. (2016, November). Case study presentations. Paper presented at the WPEC Wellington Pacific Early Childhood Education conference, Porirua, Wellington, New Zealand.

Glasgow, A. (2016, November). Te whatu mātauranga: Pacific case study action research. Paper presented at WPEC: Wellington Pacific Early Childhood conference, Porirua, Wellington, New Zealand.

Rameka, L., Glasgow, A. H., Fiti, S., Burgess, F., Kauraka, B., Howarth, P., Wills, C., Tuheke, A., & Maunsell, T. (2016, November). Te whatu kete mātauranga. Paper presented at the Reconceptualising Early Childhood Education (RECE) conference, Taupo, New Zealand.

Glasgow, A. (2016). The Pacific language nest: Preserving and maintaining language and culture. Paper presented at the Pacific Early Childhood Education conference, University of Auckland, Epsom Campus, Auckland, New Zealand.

Howarth, P. (2016). How can the rangatira of pepi/teina be embraced and enhanced through moteatea? Paper presented at the TWoA, Te Ihu symposium, Auckland, New Zealand.

Howarth, P. (2016). How can the rangatira of pepi/teina be embraced and enhanced through moteatea. Paper presented at the Tuia Te Ako conference (Ako Aotearoa) TWoA campus, Auckland, New Zealand.

Iosefo-Perez, R., Pereira, K., Perez, D. L., Anae, S., Kauone, M., Mavaega, P., & Glasgow, A. (2017, May). Tokelauan practice of Inati Matiti Akoga Amata. Paper presented to the Tokelauan community, Naenae, Wellington, New Zealand.

References

Bevan-Brown, J. (2003). The cultural self-review: Providing culturally effective, inclusive, education for Māori learners. Wellington: New Zealand Council for Educational Research.

Charmaz, K. (2005.) Grounded theory in the 21st century: Applications for advancing social justice studies. In N. Denzin & Y. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (4th ed., pp. 507–536). London: Sage.

Chu, C., Glasgow, A., Rimoni, F., Hodis, M., & Meyer, L, (2013). An analysis of recent Pasifika education research literature to inform improved outcomes for Pasifika learners. A report conducted for the Ministry of Education. Wellington: Jessie Hetherington Centre for Educational Research, Victoria University of Wellington.

Education Review Office. (2010). Success for Māori Children in Early Childhood Services. Wellington: Author. Retrieved from http://www.ero. govt.nz/publications/success-for-maori-children-in-early-childhood-services/

Lee, J., Pihama, L., & Smith, L. (2012). Marae-a-kura: Teaching, learning and living as Māori. Wellington: Teaching and Learning Research Initiative (TLRI). Retrieved from http://webcache.googleusercontent.com/search?q=cache:uEfltfwEE1EJ:www.tlri.org.nz/sites/default/files/projects/9283_summaryreport.pdf+&cd=1&hl=en&ct=clnk&gl=nz&client=firefox-b

Ministry of Education. (2009). Ka hikitia—managing for success. Wellington: Author. Retrieved from https://education.govt.nz/assets/Documents/Ministry/Strategies-and-policies/Ka-Hikitia/KaHikitia2009PartOne.pdf

Ministry of Education. (2011). Mid term review of Pasifika education plan 2009-2012 Wellington: Author.

Ministry of Education. (2014). Participation in early childhood education. Wellington: Author. Retrieved from http://www. educationcounts.govt.nz/statistics/ece2/ece-indicators/1923

Mutch, C. (2005). Doing educational research: A practitioner’s guide to getting started. Wellington: NZCER Press.

Welsh, E. (2002). Dealing with data: Using NVivo in the qualitative data analysis process. Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 3(2), Article 26. Retrieved from http://www.qualitative-research.net/fqs/</p

Research Team

|

Dr Lesley Rameka Principal Investigator lesley.rameka@waikato.ac.nz Ko Tararua te maunga, Ko Ohau te awa, Ko Tainui te waka, Ko Ngāti Tukorehe me Ngāti Raukawa ngā iwi. Lesley is a Senior Lecturer at the Faculty of Education, University of Waikato in Hamilton, New Zealand where she teaches in the early childhood and Māori education programmes. Lesley has worked in early childhood education for over 30 years, beginning her journey in te kohanga reo, and working in a number of professional development and tertiary education providers. Her research interests include Māori early childhood education, kaupapa Māori assessment in early childhood, curriculum development in Māori early childhood services, Māori pedagogies and Māori perspectives of infant and toddler care and education in early childhood. |

|

Ali Glasgow Associate Investigator ali.glasgow@vuw.ac.nz Ali is of Cook Islands and Tahitian descent. She is a lecturer in the School of Education, Ako Pai, at the Faculty of Education Victoria University of Wellington. Her previous role as an early childhood teacher practitioner spanned more than 25 years. Ali has a strong research interest in Pacific, Maori and Indigenous Early Childhood Education. She has been involved in ECE provision in the wider Pacific region including the Cook Islands, the Solomon Islands, Timor Leste and Eastern Indonesia. She is currently researching the role of the Pacific language nest in Aotearoa New Zealand in maintaining language, culture, and traditions for the nations of the Cook Islands, Niue, and Tokelau Islands. |