Introduction

Since 2013, one internally-assessed Social Studies achievement standard at each of the three levels of the National Certificate of Educational Achievement (NCEA) has required students to actively participate in a social action. Whilst these new personal social action[1] standards hold the potential to support transformative citizenship education, previous research suggests that taking social action can be viewed as ‘risky’ and time consuming. As a result, teachers stick to ‘safer’ and efficient versions of active citizenship (Taylor, 2008; Wood, Taylor, & Atkins, 2013). Our 2-year project sought to examine how these personal social action achievement standards were understood and enacted by both teachers and students and how more critical and transformative social action could be facilitated in a schooling context.

The following questions guided the research:

- What factors influence teachers’ decision to offer (or not offer) the personal social action achievement standards?

- What challenges and opportunities arise when implementing and assessing the personal social action achievement standards?

- What pedagogical approaches enable critical and transformative social actions?

- What do students understand the NCEA social action requirements to be and what are their views on the value of the personal social action standards?

The project aimed to provide: (i) research evidence of how teachers and students understand and enact ‘personal social action’; (ii) research evidence about the strategies and approaches that support students’ critical and transformative social action; and (iii) a citizenship framework to help evaluate the degree to which social action could be considered critical and transformative. We begin by presenting an outline of the critical and transformative citizenship framework which underpinned our study.

What is critical and transformative social action?

Notions of social action and ‘active’ citizenship are highly contested terms (Westheimer & Kahne, 2004). For our study, we take as a starting position that critical active citizenship education is founded on a critique of power and social injustice in society. As such, we see it as being oriented towards enhancing agency and participatory citizenship in keeping with the diverse contexts young people find themselves in as citizens (Zembylas & Bekerman, 2016). Our conception is underpinned by critical theory and critical pedagogy, as espoused by key authors (e.g. Freire, 1973; Giroux, 2009; Kincheloe, 2007). Paulo Freire’s ideas were especially fruitful when considering pedagogical approaches and ideas that could contribute to the criticality and transformative forms of social action. Freire developed the notion of praxis, a process of reflection and action by people upon the world in order to transform it. Through praxis and dialogue, students develop a critical consciousness (conscientization) in which they encounter “problems relating to themselves in the world and with the world” (Freire, 1973, p. 62). As a result, Freire (1973) argued gaining understandings about the ways society operates to perpetuate the dominance of some groups over others would lead students to “feel increasingly challenged and obliged to respond to that challenge” (p. 62).

While Freirean and critical pedagogy ideas have been most significant in our conceptualisation of critical and transformative social action, we also drew on a number of other traditions of active citizenship education. For example, the work of progressive educators, such as John Dewey, was also influential in how we viewed critical and transformative social action. These educators believed that authentic, ‘real world’ contexts for learning could transform students’ political orientations as well as encourage meaningful and community-inspired responses as democratic citizens (Dewey, 1916). We also explored recent learning theories that promote more ‘performative’ responses from learners in order to develop the deep complex relationships between knowledge, skills, personal qualities, and values that social actions encompass (Atkins & Rawlins, 2016; Hipkins, 2009).

In sum, we view ‘critical and transformative’ social actions as acts of citizenship that aim towards social transformation and the creation of a more just, equal, and inclusive society. These are necessarily value-laden acts that require the integration of the cognitive understandings with the creative and emotional moral task of caring (Lipman, 2003) in order to develop what Lindquist (2004) calls ‘strategic empathetic emotions’. Similarly, ‘transformative’ social action implies a commitment to work collectively against oppression in its many guises (such as those based on class, race, colonisation, gender) in order to create a more just and sustainable society (Freire, 1973; Johnson & Morris, 2010; Westheimer & Kahne, 2002). While these may sound like lofty goals for school-based social action, the focus on social change is a key feature of critical and transformative citizenship which generally involves actions taken to “shape the society we want to live in” (Vromen, 2003, p. 83). This definition aligns with the NCEA standards which define social action as “the ways that people participate in shaping society for the common good” (NZQA, 2013).

In order to adapt these ideas into educational contexts we drew on a number of prior models (e.g. Johnson & Morris, 2010; McLaughlin, 1992; Westheimer & Kahne, 2004). Broadly, these models suggest that there is a spectrum of conceptions of active citizenship that range from minimal approaches (such as obeying the law and being public spirited) to more maximal approaches which include a commitment to addressing systemic causes of injustice and inequality (Johnson & Morris, 2010; McLaughlin, 1992; Westheimer & Kahne, 2004). Whilst we found these models very useful for our understandings of critical and transformative citizenship, most held an adult bias (overlooking the restrictions many young people face in their democratic participation as a result of age and opportunity) and provided little detail about how to support such ideals within busy, assessmentfocused classrooms. Our research aimed to address this gap by providing evidence-based research on the practices, dispositions, and actions of teachers and students that supported critical and transformative social action.

Research methodology

To answer our research questions we developed a mixed methodology in order to ascertain what was happening at a national scale as well as within the micro-spaces of classroom practice (Table 1). The quantitative data collection included the dissemination of an electronic nationwide teacher survey on social action in Social Studies, and the analysis of NZQA data on the uptake and attainment of NCEA social action achievement standards (Table 1, RQ1). For the school-based data collection, a university-based researcher was partnered with each of the five teacher-researchers. A range of data collection methods was employed including:

discussions with teachers, together and individually; classroom observations; student focus groups; and student work analysis (Table 1, RQ2, 3, 4). Each teacher also conducted their own teaching inquiry in both years. Ethical permission was gained from Victoria University of Wellington (VUW) on 8 March 2015 [HEC21663].

| Research question | Year 1 | Year 2 |

|---|---|---|

|

Survey and analysis of NZ SST teachers n = 141[2] | Analysis of NCEA, NZQA national data 2014 and 2015

Participant teacher interviews |

|

Initial baseline reflections by participating teachers (Hui 1)

Individual discussions throughout research Classroom observations in schools Teacher discussions and own teaching inquiries (x5) Shared summary of findings of key themes Hui 2 (November) with full team |

Teacher focus group discussions July 2016

Individual teaching inquiries—shared July 2016 Classroom observations in schools Collective development of critical transformative framework |

|

Classroom observations in schools (7 classrooms)

Focus group discussions with students in each school (n = 52) Some observations of social action in practice Document analysis of student work |

Classroom observations in schools (7 classrooms)

Focus group discussions with students in each school (n = 41) Some observations of social action in practice |

The project relied on a strong partnership model between the university research team and five participating teachers located within a diverse range of secondary schools. A reflective practitioner model (Cochran-Smith, Barnatt, Friedman, & Pine, 2009) underpinned all of the school-based research. Teachers actively contributed to the research and regularly shared their ideas, experiences, reflective inquiries, and questions with the entire team. Three hui (early Year 1, late Year 1 and mid-Year 2) provided opportunities for the teachers and university researchers to share their individual teaching inquiries, findings, and analysis of key readings. The team examined research-led data and patterns within and across the five schools in order to determine effective approaches and strategies. Key patterns and themes were synthesised by drawing on international research and classroom experience (Cohen, Manion, & Morrison, 2011). In the second year of the project, teachers drew on the research evidence to trial identified strategies further to confirm and validate initial findings.

Key findings

We have structured our key findings under four headings based on our research questions. The first section draws on an analysis of NZQA data and the quantitative data we collected through our online survey of Social Studies teachers in 2015 (Table 1). The other three sections draw predominantly on the in-school data.

Who is taking up personal social action achievement standards in New Zealand?

Our review of recent NCEA data revealed that between 2013 and 2015 there was a steady rise in the numbers of schools offering senior Social Studies NCEA standards—from 186 schools in 2013 to 222 in 2015. By 2015, 61% of New Zealand secondary schools were offering at least one Social Studies achievement standard. Of these schools, more than half (53.2% in 2015) had students completing at least one level of the personal social action (PSA) standards; however, only a handful of schools (11.3% in 2015) assessed students in the PSA standards at all three levels (Table 2).

| Percentages | |||||

| Year | Offered PSA at at least one level |

Offered PSA at all levels |

Offered PSA at Level 1 only |

Offered PSA at Level 2 only |

Offered PSA at Level 3 only |

| 2013 | 52.2 | 8.1 | 23.1 | 3.8 | 3.2 |

| 2014 | 58.3 | 10.8 | 21.6 | 3.4 | 6.4 |

| 2015 | 53.2 | 11.3 | 20.7 | 1.8 | 6.3 |

In 2015 a total of 22,797 students undertook senior Social Studies assessments at one or more of Levels 1–3 of NCEA. Of these, 4,718 (20.7%) were assessed for the PSA standards with Level 1 being the most commonly assessed standard. Of all the Social Studies standards taken at Level 1 in 2015, the internal AS91043 – Describe a social justice and human rights action was the most popular (65% of all Level 1 Social Studies standards), followed by AS91040 – Conduct a social inquiry (47.3%) and AS91042 – Report on personal involvement in a social justice and human rights action (39.7%). Both data sets indicated that more students complete internallyassessed achievement standards than externally-assessed ones.

Our analysis of NZQA data showed that a substantial gender gap exists in senior Social Studies, with males representing only 30% (6,878) of the 22,797 students in 2015. This gender pattern was also reflected in the PSA assessments with male participation being 33% in Level 1, 21% in Level 2, and 24% in Level 3. There was also a gender-related achievement gap, with males about twice as likely as females to receive grades of Not Achieved, and less than half as likely to attain grades of Excellence. The pattern for Māori achievement in AS91042 followed the same general distribution to boys, while European followed a similar distribution to girls. Pasifika students performed slightly better than Māori. Students from higher deciles schools also had higher attainment of Merit and Excellence than students from lower decile schools.

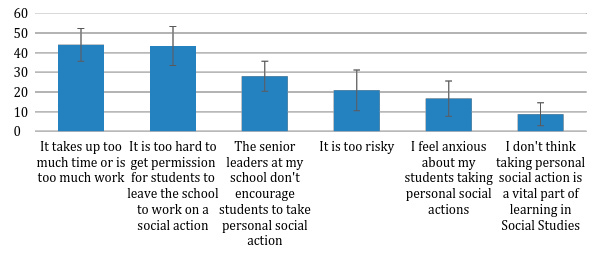

Our survey found that the PSA standards were most often offered by teachers who had been teaching Social Studies for between 3 to 5 years. This finding might reflect the timing of the progressive introduction of the standards (from 2011 to 2013) and greater focus on senior Social Studies within initial teacher education programmes. Of our survey respondents, 41% (n = 58) reported that they were offering or had offered a PSA standard. A small number (n = 28) provided reasons why they were not offering a PSA standard in 2015 (Figure

1). Their reasons were largely logistical while a few had anxieties about the ‘riskiness’ of the standards (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Percentages of respondents indicating reasons for not offering personal social action achievement standards

In our survey we trialled two clusters of ‘beliefs and values’ that Social Studies teachers held. One cluster centred on beliefs about democracy and how this linked to support of social action and the other cluster focused on beliefs about community and youth participation. While the mean level of endorsement for both viewpoints was greater for teachers who use the social action standards in their assessment programmes than for those who do not, neither difference was statistically significant. Even so, the sample was small and the possibility that such a difference exists deserves further investigation.

Undertaking and assessing personal social action

Students in our project identified some clear differences in the personal social action achievement standards to most other standards they had undertaken. Rather than ‘smashing out an internal in a couple of days’, they described how taking social action often involved weeks of planning and implementation as well as high levels of reflection throughout the process (see also Atkins, Taylor, & Wood, 2016). Taking social action involved a different set of skills, and these were ‘more hands on and practical [than] a lot of the stuff we learn in school’. Encounters with the public and community in particular meant students needed to develop a set of ‘real-life skills’, which included, for example, emailing and letter writing to newspapers and Members of Parliament, interviewing and surveying people, and meeting with community members.

Students also described how these standards gave a lot of ‘freedom in the sense that you got to choose what you wanted to do’. They described how this degree of freedom and choice meant that they found the standard more ‘fun’ and ‘interesting’ as they got to choose ‘something [they] were quite passionate about’ and in that way it was a ‘lot more personal’. They also articulated the hope that they might make some real difference for others was a significant motivation, and that the authenticity of ‘real-world’ issues enhanced their engagement, research, and knowledge:

… it’s really nice getting out into the community and it’s also that you’ve actually got that one-on-one contact with people and, say if someone tells you something, like their opinion of something, you can use that in your assessment as primary evidence.

In addition, students noted that a key attribute of the personal social action standards was that, even if their social action was unsuccessful, they could still achieve the standard based on the quality of their reflection on the process.

Teachers and students also reported that another key difference between personal social action assessments and other assessments was the need to establish a sense of personal and emotional engagement with the focus of their social action. In short, the students had to ‘care’ about their social issue and their social action if it was to be meaningful and authentic (Wood & Taylor, 2017, forthcoming). As one teacher explained:

… you just don’t go ‘Aw, I’m gonna have a social action just now’. It’s like a whole thing, the emotion that there’s an injustice or something that needs working on.

Metzger, Syvertsen, Oosterhoff, Babskie, & Wray-Lake (2016) suggest that an individual’s motivation, skills, and personal characteristics play a large role in their decisions to pursue specific forms of civic action. In our study we found that when it came to selecting a social issue, students’ sense of agency and engagement was significantly enhanced when faced with issues with which they had some level of personal experience, interest, and understanding and which they voluntarily selected. This served to heighten their interest and also reduced the need for teachers to compel students to select an issue that wasn’t their choice (McIntosh & Youniss, 2010; Wood & Taylor, 2017, forthcoming). Students described how, once they had identified a connection or attachment to a social issue, their emotional engagement inspired them to take action. For example, a 15-yearold female student described how a sense of empathy sparked a desire to take action:

When we saw … that some people are living in damp homes … it is just really horrible and I just couldn’t imagine living in that sort of place … it was really horrible. I just wanted to help them …

As this quote illustrates, the act of taking social action is in itself an intrinsic act that rests upon a set of values. For example, lobbying the Government to increase New Zealand’s refugee quota (an action that many students in our study took in 2015) rests on values that could include: a welcoming and inclusive disposition towards new migrants; a sense of responsibility for global world issues; and possibilities of providing support and care. Recognising these values meant students could articulate why they took the action they did.

Teachers used a variety of approaches in setting up social inquiry for social action (Ministry of Education, 2007). Drawing on Spronken-Smith and Walker’s (2010) typology for inquiry, we found teachers adopted a range of models from teacher-led at one end to student-led at the other, with a more middling position of teacher-guided in the centre (Figure 2). The conditions of structure or freedom for students’ social action had a significant impact on their experiences. Where there was less choice and freedom, students felt restricted and frustrated (see ‘Teacher-led’, Figure 2). For example, in one class where the teacher had pre-selected the social issue, students had high levels of knowledge but one student (17 years) felt it was ‘kind of imposed on us’ and as a result said, ‘I don’t feel as emotionally charged about it’. In contrast, without guidance, some student-led projects had high engagement but lacked coherency or depth and led to frustration.

| Teacher-led structured inquiry | Teacher-guided inquiry | Open student-led inquiry | |

| Knowledge |

|

|

|

| Engagement |

|

|

|

Teacher-guided social action inquiries involved teacher input throughout, but generally led to strong knowledge and engagement outcomes. We found that teacher-guided social action involved a delicate juggle between at times “letting go” (Zohar & Cohen, 2016, p. 94) of the decision making to enhance the learning experience, and at other times intervening to promote higher order thinking. The degree of teacher facilitation did vary at different stages of the social action process (see also Mutch, Perrau, Houliston, & Tatebe, 2016) and had consequences for student engagement and knowledge (Figure 2). Notably, most teachers in our study had adopted a teacher-guided approach by year two.

Pedagogical approaches that support more active and critical forms of social action

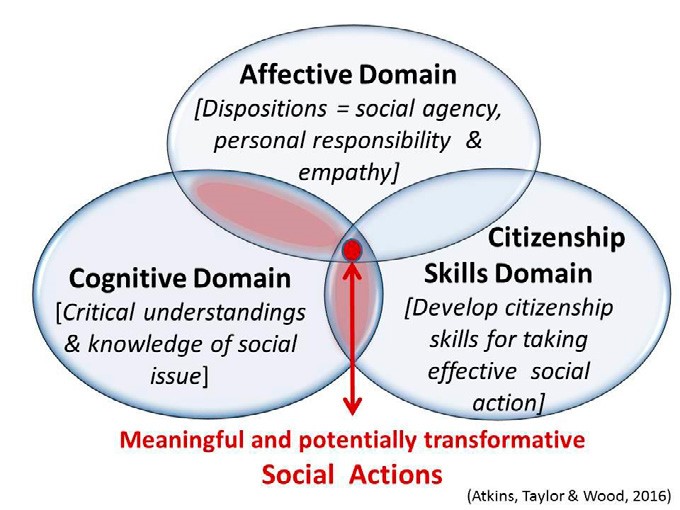

Our research found that teachers needed to be confident, skilled practitioners to navigate the unique challenges associated with taking social action as outlined above. Such challenges for teachers who were committed to promoting more critical and transformative forms of social action centred on:

- encouragement of students’ affective engagement if social actions were to be authentic and meaningful for students

- scaffolding in-depth cognitive and critical understanding of real-world social issues

- providing opportunities for the development of a suite of citizenship skills, values, and dispositions (Johnson & Morris, 2010).

These pedagogical strategies fit broadly within Brian Hill’s (1994) domains of learning in Social Studies (Figure 3) which we have also written about in greater depth (Atkins et al., 2016).

Figure 3: Domains of learning for social action

The Affective Domain: Before social action could happen, our research showed that teachers needed to ensure that students: were emotionally engaged in the social issue of choice; had effective knowledge about the social issue; had a sense of efficacy or self-confidence to take personal action; and could justify taking their social action when challenged. We also found that this process for teachers involved the careful navigation of the affective dimension of taking social action (Wood, 2015; Wood & Taylor, 2017 forthcoming). In addition, in order for students to feel comfortable to express their views and to experiment with tentative ideas, the class atmosphere must feel inclusive and “safe” (Zohar & Cohen, 2016, p. 91) for young people to believe their participation is valuable.

A key challenge within the affective domain for teachers was the dilemma between encouraging students’ emotional engagement (in order to counter tokenistic, technocratic, and minimal social action for creditharvesting), yet avoiding emotional coercion. Teachers needed to be ‘critical design experts’ (Zembylas & Bekerman, 2016) to balance a commitment to the values of social justice and equality with a commitment to critical thinking, ethical action, and reflection about some of the world’s most complex issues.

The Cognitive Domain: Social action is founded upon strong levels of knowledge about the social world and also upon the identification of social—political, cultural, economic, environmental—issues that hold personal and social significance for them. Our research found that students who had a stronger cognitive knowledge about the focus of their social issue were able to design more effective and meaningful social action and justify this when challenged. This also enabled them to be more reflexive and critical of their own actions—a key component of the NCEA assessment standards, as this Year 13 student reflected:

I realised when we researched that there were a lot more limitations to what we were doing … with the statements that had been made and things like that. We realised that ‘Oh, what … maybe we could have done things a lot better than we did.’

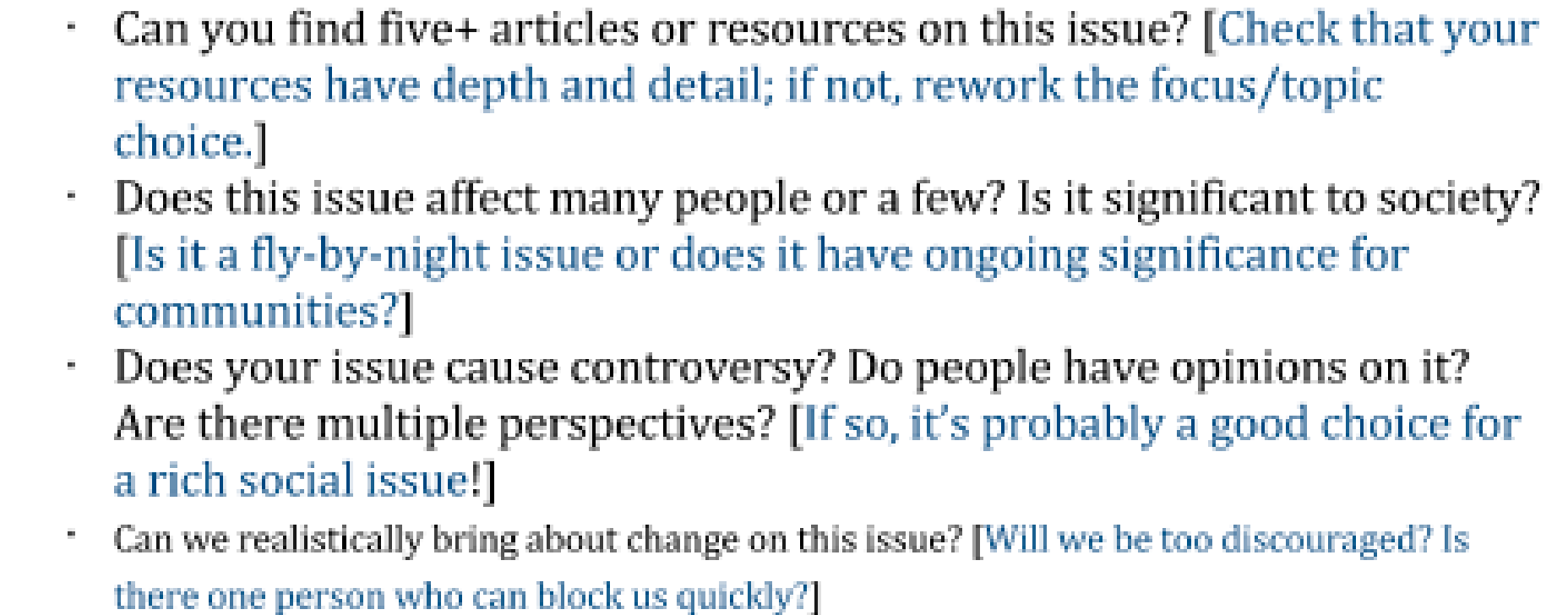

Teacher guidance was key to encouraging higher levels of criticality and reflection, and through prompting students to consider some of the limitations of their choice of social issues and actions (Figures 2 and 4).

Developing deeper cognitive levels also involved a critical approach to social issues learning which enabled students to critique their own and others’ assumptions and to encounter multiple perspectives about social knowledge. In classrooms, this involved wading into controversy based on an examination of the facts in order to develop rational, logical, and active responses to social issues, as well as gaining understandings of a range of alternative perspectives on an issue (Westheimer & Kahne, 2002). Our team co-constructed a planning checklist of prompt questions (Figure 4) for teachers to use with students to help them select meaningful issues and actions to explore and take.

Figure 4: Teacher prompt questions for selection of social issues to take action on

Citizenship Skills Domain: Developing skills for effective citizenship is regarded as one of the foundational twin goals of Social Studies (Barr, 1998). Johnson and Morris (2010) suggest that some of these skills include critical and structural social analysis, skills in dialogue and co-operation, interpretation of others’ viewpoints, and independent critical thinking. As Dewey (1916) argued, learning about a democracy requires a pedagogy that is experiential, involves real people and real places, and has meaning for the individuals involved. A significant number of students in our project talked about how the process of taking social action helped them to recognise that they themselves were political and knew how to make change to government policy now and in the future, and that this also enhanced their sense of agency and self-efficacy. One student reflected:

We don’t have to be someone big to make an influence. Like, just high school students can start an influence, or if you’re like determined we can bring about a change … [I now know that by] just emailing you can raise awareness and stuff.

Other key learnings students reported included the importance of good research to underpin the social action, enhanced critical thinking, knowledge of government processes, increased awareness of community activities, and a range of life skills. A full suite of citizenship skills is not easy to pin down as social actions need to align with the focus social issue so the range of strategies employed may differ every time.

In summary, the pedagogies that supported critical and transformative social action required teachers to embrace a pedagogical agility and high degree of commitment to social justice. In Kath Murdoch’s (2004) words, “a great unit has a deft mix of the planned and spontaneous, of deliberate, guided tasks and more organic, responsive teaching arising out of the interactions we have with students” (p. 3).

Implementing potentially critical and transformative social actions

Our survey of New Zealand teachers (n = 141) revealed the prevailing forms of social action were:

- Creating awareness (72%)

- Fundraising (71%)

- Letter writing (57%)

- Advocating for in-school changes (55%).

Our school-based research found that students across our five schools actually selected a wider range of social actions than these four. Broadly, we classified their actions into four categories (Figure 5). We identified that most students utilised more than one of the strategies, with most (especially at NCEA Level 3) combining several strategies to design a ‘campaign’ of social action.

| Types of social action | Fundraising | Educating ourselves and others | Raising awareness | Advocacy and direct lobbying |

| Examples |

|

|

|

|

For example, students in Year 13 who were working to influence policies to increase the refugee quota and promote more supportive environments for refugees used a multi-pronged approach that included:

- Education: Students put up posters about refugees and the quota around their schools and in the community based on their research and interviewed staff members about their perspectives.

- Awareness: Students organised school-wide events to increase awareness about refugees. Two former refugees from the New Zealand Refugee Youth Council spoke about their experiences; MPs talked about Government policy on refugee quotas and a non-governmental organisation (NGO) shared what they did to support refugees.

- Advocacy: Students collected signatures for an open letter to support increasing the quota and sent this to the Select Committee.

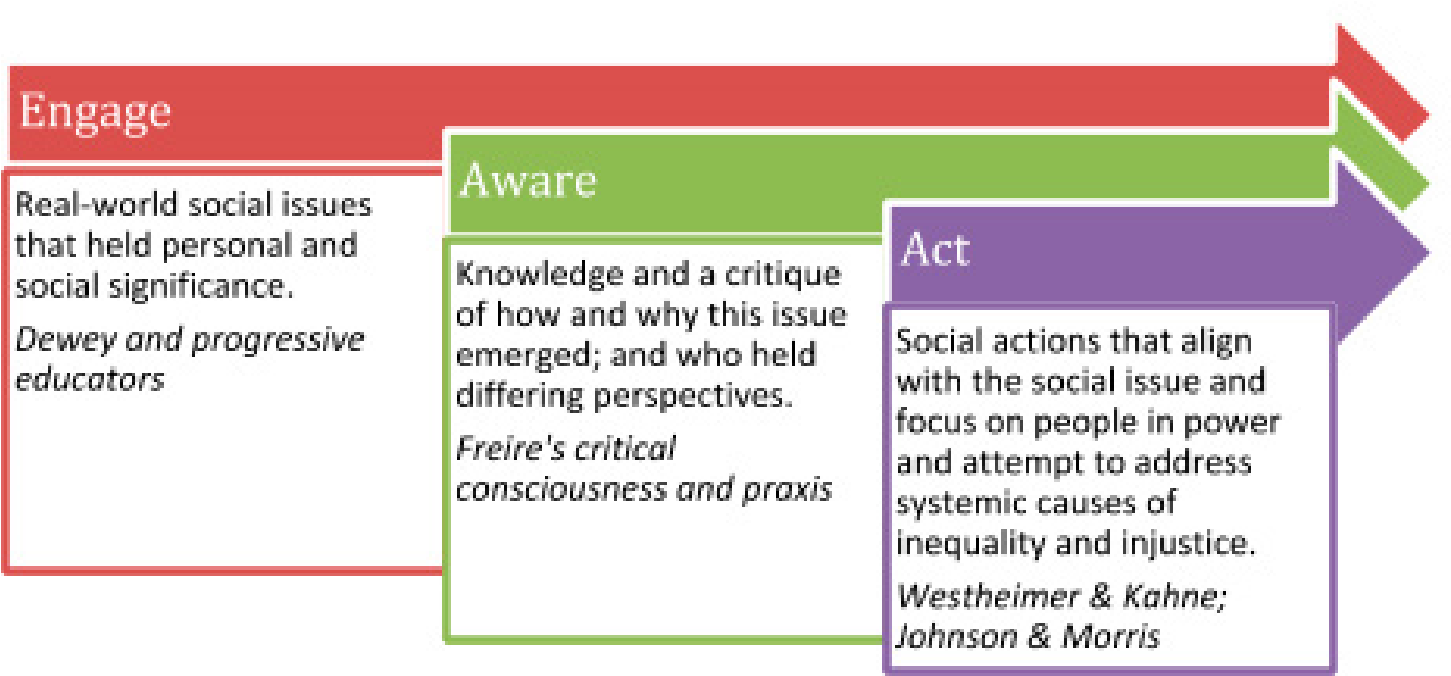

The NCEA standards do not stipulate that social actions must be critical and transformative. We found that to promote critical and transformative social action, students needed to be encouraged to think more critically about the kind of actions that could promote more sustainable social change. Some teachers found that by banning fundraising, students were encouraged to think more critically. The NCEA Level 3 requirement to ‘influence policy’ also encourages students to take a much greater critical consideration of systemic causes and solutions to social issues than Levels 1 and 2. Some students reported that the lack of immediate results was at times discouraging. We found that students’ actions held greater potential to be critical and transformative if they:

- were focused on issues of personal and social significance (these held greater meaning and authenticity for students)

- were underpinned by in-depth knowledge and a critique of how and why these issues emerged (evidencebased and informed by a wide range of perspectives)

- developed a social action strategy that matched the social issue and reached a range of interest groups— including those who held positions of power in order to inform future change.

In Figure 6 we link these three components to key theorists (as discussed earlier) to describe a process of engagement (which goes deeper than just an emotional state, to one of active involvement (Fletcher, 2008)), awareness, and action as students take social action.

Figure 6: The process of social action and theoretical underpinnings

Changing the world one person at a time? Students who undertook social action at Level 3 did not generally achieve policy change—at least not alone. Students did gain great satisfaction from being part of, for example, the policy change that increased the refugee quota for New Zealand in 2015. However, we believe it would be helpful if the ‘personal’ social action standards recognised the collective and often slow nature of social change and the significance of “small, strategic steps towards change” (Zembylas & Bekerman, 2016, p. 277). The focus on performed social actions for assessment can also overlook the small and everyday ways young people already take actions as citizens (Wood, 2014). In the words of one Year 13 student:

You could change like one person’s perspective and that’s enough because you have actually done something, you have actually changed something even if it is not something massive it is still something.

In this final section we outline three vignettes from our study to show the diverse ways that critical and transformative social action was undertaken in schools. The first vignette is a teaching inquiry that illustrates how a teacher attempted to ‘lift’ the democratic vision and citizenship skills of her students to empower them to engage with real-world issues and political processes in New Zealand.[3]

| Teaching vignette: Experiencing the democratic process as young citizens

A TLRI teacher-researcher from outside Wellington wanted her students to experience what it means to participate as citizens in a democracy. This is especially important at Level 3 where students need to ‘influence policy’. She reasoned: Why not go to where national policy change is constructed so the students get an authentic experience? So she started her unit by integrating a visit to Parliament into her Level 3 Social Studies programme and included a visit to National Archives where the students were able to see major legislation, such as the Women’s Suffrage Act 1893. Her Level 3 class had already chosen their social policy issues and in groups had undertaken research and begun to plan a campaign of social actions. Going to Parliament helped them to gain further knowledge about how to work towards policy change in a democracy: … the ability to ask our MP questions was the best way for me to understand and gain comprehensive knowledge about policy change. It was so cool to actually see it in person, rather than be told by a teacher in a classroom… Getting to see what happens in Parliament gave me a useful knowledge base for my internal about creating policy change. Students commented that the trip to Parliament helped them significantly in feeling like they were active members of society and that Parliament was also ‘their place’ (as they were told by their guide on the tour). After this trip students said that setting up a meeting and interviewing their local MPs was easy: ‘We were quite comfortable about it, yeah, he was quite approachable. There was something kind of nice about it because we were sitting around and it was kind of this discussion rather than awkward questions…’ Visiting Parliament is not a ‘magic bullet’. Some students still had lingering doubts about their agency due to people perceiving them as school students and one group wished they had had the courage and organisational skills to submit on a current Bill. While we cannot examine the future impact of these experiences, one student commented: What I gained from the trip is also useful for my life in general because learning how New Zealand is governed is something high school students should know about. |

Analysis: This example illustrates how this teacher’s planning enabled her Level 3 students to gain greater knowledge about policy change in a democracy and shows many of the characteristics of critical and transformative social action. First, the students had the freedom to select and to inquire deeply into a policy that addressed a social issue. Second, the teacher prepared her students well for the visit so that they were confident in responding to the guide’s questions and asked their own questions of guides and politicians. One guide commented on how knowledgeable the students were about parliamentary processes. Third, even though students would have already learned about systems of government during their Year 9–10 Social Studies, the authentic experience of visiting Parliament affirmed this learning and made it much more meaningful and personally significant. Finally, as these young people are transitioning to adulthood, their selfefficacy beliefs about their ability to engage with social issues, policies, and actions should augur well for their continued involvement in civic life.

The following vignettes of Year 13 students’ social action illustrate the process outlined in Figure 6 of forms of critical and transformative social action.[4]

| Student learning vignette 1: Seeking to promote Māori success in schools

Ana is a Year 13 student who identified as Māori and was a member of a Māori whānau support group that sought to support Māori student success in the school. For her social action, Ana examined the Ministry of Education’s Māori Education Strategy, Ka Hikitia—Accelerating Success (2013–2017), a strategy document that outlines policies and practices aimed to enhance the success of Māori students. Her focus was for her school to work towards more effective implementation of this strategy. While the school had endorsed Ka Hikitia, its implementation was still somewhat patchy. Ana obtained research from the Māori support group which showed that students who affiliated with the group achieved better results than Māori who didn’t join the group. She also interviewed senior members of the school to hear their views on Ka Hikitia and uploaded a survey on Facebook to ascertain the support people had towards making the strategy compulsory. She then wrote to the Minister of Education, Hon Hekia Parata, to communicate her findings from the interviews, survey, and data analysis to argue that Ka Hikitia should become compulsory in schools. Ana received a letter back from Minister Parata which congratulated her on her initiative but said that there wouldn’t be any changes to make Ka Hikitia compulsory in New Zealand schools. Ana felt pleased with the support offered to her initiative within the school but disappointed that the Government ‘just said they basically can’t make it compulsory’. |

Analysis: This example of Ana’s social action shows many of the characteristics of critical and transformative social action. First, she selected a social justice issue that had meaning and significance for herself and others with the goal of gaining greater recognition and equity for Māori in her school. Second, she then critiqued and analysed school data to explore how successful Māori students were. She gained further knowledge by interviewing strategic people in the school and undertaking a survey. Third, she then included these understandings and perspectives in her letter to the Minister of Education. Whilst her social action did not lead to policy change, she was confident that it had raised the profile of the Ka Hikitia strategy and awareness in the school. Her experience of the social action standard was that it was highly engaging ‘because I could choose what I wanted to do and I was really passionate about my topic so I was keen to do it’. Her future plans included studying Te Reo and Pacific languages to support the growth of these in schools.

| Student learning vignette 2: Contributing youth voice to climate change policy

A group of three Year 13 students selected climate change as their social issue of focus following a series of flooding incidents in their town. They examined the Greater Wellington Region’s Draft Climate Change policy, and in particular what it said about what people could do to help address the problems caused by climate change as ‘many believe that they can’t make any difference to it’. After some initial research they became aware that the consultation document had not included children and young people, as one student articulated: We believe the Greater Wellington Regional Council’s Draft Climate Change Strategy does not sufficiently take into account the youth in our region. By finding out what young people know about climate change and developing ideas about how they can take small actions, we are helping to strengthen the policy. For their social action they held a workshop with children at a local primary school to hear their perspectives on climate change and also what they felt they could do to make a difference. They collected the children’s feedback and collated it in into a submission to the Greater Wellington Regional Council. They found children were keen to be consulted and involved and had worked out many everyday ways to reduce the potential for increased climate change (such as riding their scooters and bikes, recycling, and using public transport). They argued that: This is the generation that we should be educating and getting involved in climate change efforts as the youth of our community now are going to be crucial in combating climate change in the future … including these views in your draft strategy will enable their voices to be heard. |

Analysis: In this case study the students had gained knowledge and awareness through prior teaching about climate change, how people had worked to address concerns, and how policies could shape current and future responses. A recent flooding event had highlighted this to them further. The issue was therefore both personally and socially significant to their community and the nation. Their critique was that, to date, the Regional Council had not consulted children and young people well. They used a community-based, collaborative approach to gather children’s perspectives (the children drew posters and discussed ideas in focus groups) to develop a submission to the Greater Wellington Regional Council that reflected the views of approximately 30 children. Their submission held potential to contribute to future planning and highlighted the significance of small actions of young citizens.

Limitations of the study

- This is a relatively small-scale study that involved five strong teacher-researchers who were advocates of social action in schools where Social Studies was generally well established. Further research with a broader range of schools across New Zealand and international comparisons could serve to confirm and critique the findings further.

- We believe that sustainability is a key attribute of critical and transformative social action (Kahne & Westheimer, 2006). However, due to the 2-year focus of our study we were unable to examine this in great depth. Future longitudinal research into the impact of school-based social action on future behaviours and dispositions would be beneficial (Wood, 2017).

Implications for practice

- Taking critical and transformative social action in schooling contexts can be challenging but if students focus on issues of personal and social significance, critique and acquire in-depth knowledge about social issues, and develop strategies that focus on addressing deeper levels of injustice/inequality then their actions are more likely to be transformative (Figure 6).

- As social action rests upon personal values and intrinsic motivation, teachers need to navigate the affective dimensions of the personal social action achievement standards carefully to enable students to ‘opt into’ social action and to provide support for students to plan and develop their social action with high levels of reflection.

- Students who did not have a meaningful social action experience were less enthusiastic about their future participation as citizens. The stakes are therefore high to ensure that school-based experiences of social action are meaningful and empowering.

- Encouraging students to consider social action beyond fundraising also led to higher levels of criticality and potential social change but also at times to lower levels of immediate satisfaction. The requirement to ‘influence policy’ at Level 3 led to much greater critical consideration of systemic causes and solutions to social issues as this involved engagement with national or regional-level policies.

- In order to empower young people as political actors, it is important that students gain an understanding of the opportunities and limitations of NCEA social action assessment. Real change generally requires collective action and initiatives from other bodies, including the state (Biesta, 2011).

Conclusion

The inclusion of personal social action achievement standards in Social Studies provides a unique and valuable opportunity for New Zealand students to examine social issues, design and implement a plan for action, and reflect upon this. Almost all of the 91 students we interviewed described ways that the process of taking social action had enhanced their learning about social issues, citizenship processes, and given them a range of life skills for engaging in communities and society. We summarise some key lessons and challenges identified during our research with these students and their teachers in Figure 7.

Figure 7: New understandings developed about guiding students through the personal social action standards

Key lessons

Key challenges

|

Footnotes

- The NCEA achievement standards use the term ‘personal social action’ in relation to participatory social action. We revert to ‘social action’ when referring to the enacted process and use this interchangeably with ‘active citizenship’ which is a term used widely internationally. ↑

- The survey link was shared with over 400 teachers via notifications posted on two private Facebook pages for NZ Social Studies teachers and an email circulated by the Core National Coordinator of Social Science Education in 2015. We chose to send the survey to teachers of Years 9–13 Social Studies, rather than just senior Social Studies (Years 11–13), as we recognised that some teachers may have previously offered NCEA standards and we wanted to know why they were not offering them now. ↑

- This was the focus of the teacher’s inquiry. ↑

- See also Case Studies in Atkins, Taylor, and Wood, 2016, pp. 18–21. ↑

The team

This report reflects the collective work of the university researchers: Dr Bronwyn Wood and Dr Michael Johnston (Victoria University of Wellington), and Dr Rowena Taylor and Rose Atkins (Massey University); and the teacher-researchers Joanne Wilson (Palmerston North Girls’ High School), Mary Greenland (Nayland College), Kathy Grey (Horowhenua College), Amy Perkins (Bishop Viard College), and Caroline Wallis (Paraparaumu College).

References

Atkins, R., & Rawlins, P. (2016). How to use assessment to enhance learning in social studies. In M. Harcourt, A. Milligan, & B. E. Wood (Eds.), Teaching social studies for critical, active citizenship in Aotearoa New Zealand (pp. 134-151). Wellington: NZCER Press.

Atkins, R., Taylor, R., & Wood, B. E. (2016). Planning for critically informed, active citizenship: Lessons from social-studies classrooms. SET: Research Information for Teachers, 3, 15–22. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.18296/set.0052

Barr, H. (1998). The nature of social studies. In P. Benson & R. Openshaw (Eds.), New horizons for New Zealand social studies (103-120). Palmerston North: ERDC Press, Massey University.

Biesta, G. (2011). Learning democracy in school and society: Education, lifelong learning, and the politics of citizenship. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

Cochran-Smith, M., Barnatt, J., Friedman, A., & Pine, G. (2009). Inquiry on inquiry: Practitioner research and student learning. Action in Teacher Education, 31(2), 17–32. doi:10.1080/01626620.2009.10463515

Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2011). Research methods in education. New York: Routledge.

Dewey, J. (1916). Democracy and education. New York: Macmillan.

Fletcher, A. (2008). The architechture of ownership. Educational Leadership, 66(3), Available at http://www.ascd.org/publications/ educational-leadership/nov08/vol66/num03/The-Architecture-of-Ownership.aspx.

Freire, P. (1973). Pedagogy of the oppressed. London, UK: Penguin Books.

Giroux, H. (2009). Introduction: Democracy, education and the politics of critical pedagogy. In P. Mclaren & J. Kincheloe (Eds.), Critical pedagogy: Where are we now? (1-5) New York, NY: Peter Lang.

Hill, B. (1994). Teaching secondary social studies in a multicultural society. Melbourne, VIC: Longman Cheshire.

Hipkins, R. (2009). Determining meaning for key competencies via assessment practices. Assessment Matters, 1, 4–19.

Johnson, L., & Morris, P. (2010). Towards a framework for critical citizenship. Curriculum Journal, 21(1), 77–96.

Kahne, J., & Westheimer, J. (2006). The limits of political efficacy: Educating citizens for a democratic society. PSOnline, April 2006, 289–296.

Kincheloe, J. (2007). Critical pedagogy in the twenty-first century: Evolution for survival. In P. Mclaren & J. Kincheloe (Eds.), Critical pedagogy: Where are we now? (pp. 9–42). New York, NY: Peter Lang.

Lindquist, J. (2004). Class affects, classroom affectations: Working through the paradoxes of strategic empathy. College English, 67(2), 187–209.

Lipman, M. (2003). Thinking in education (2nd ed.). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

McIntosh, H., & Youniss, J. (2010). Towards a political theory of political socialisation of youth. In L. Sherrod, J. Torney-Purta, & C.

Flanagan (Eds.), Handbook of research in civic engagement in youth (pp. 23–41). Hoboken: John Wiley and Sons.

McLaughlin, T. (1992). Citizenship, diversity and education: A philosophical perspective. Journal of Moral Education, 21(3), 235–250.

Metzger, A., Syvertsen, A. K., Oosterhoff, B., Babskie, E., & Wray-Lake, L. (2016). How children understand civic actions. Journal of Adolescent Research, 31(5), 507–535. doi:10.1177/0743558415610002

Ministry of Education. (2007). The New Zealand curriculum. Wellington: Learning Media.

Ministry of Education. (2013). Kahikitia: Accelerating success 2013-2017. Wellington: Author.

Murdoch, K. (2004). What makes a good inquiry unit? (1-4) Education Quarterly Australia: Talking English, Autumn.

Mutch, C., Perrau, M., Houliston, B., & Tatebe, J. (2016). Teaching social sudies for social justice: Social action is more than ‘doing stuff’. In M. Harcourt, A. Milligan, & B. E. Wood (Eds.), Teaching social studies for critical, active citizenship in Aotearoa New Zealand (pp. 82–101). Wellington: NZCER Press.

NZQA. (2013). Social studies subject resources. Retrieved from http://www.nzqa.govt.nz/qualifications-standards/qualifications/ncea/ subjects/social-studies/levels/

Spronken-Smith, R., & Walker, R. (2010). Can inquiry-based learning strengthen the links between teaching and disciplinary research? Studies in Higher Education, 35(6), 723–740.

Taylor, R. (2008). Teachers’ conflicting responses to change: An evaluation of the implementation of senior social studies for the NCEA 2002– 2006. Doctor of Education thesis, Massey University, Palmerston North.

Vromen, A. (2003). ‘People try to put us down…’: Participatory citizenship of ‘Generation X’. Australian Journal of Political Science, 38(1), 79–99.

Westheimer, J., & Kahne, J. (2002). Education for action: Preparing youth for participatory democracy. In R. Hayduk & K. Mattson (Eds.), Democracy’s moment: Reforming the American political system for the 21st century. New York, NY: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Westheimer, J., & Kahne, J. (2004). What kind of citizen?: The politics of educating for democracy. American Educational Research Journal, 41(2), 237–269.

Wood, B. E. (2014). Researching the everyday: Young people’s experiences and expressions of citizenship. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 27(2), 214–232. doi:10.1080/09518398.2012.737047

Wood, B. E. (2015). Freedom or coercion? Citizenship education policies and the politics of affect. In P. Kraftl & M. Blazek (Eds.), Children’s emotions in policy and practice: Mapping and making spaces of childhood (pp. 259–273). London, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Wood, B. E. (2017). Youth studies, citizenship and transitions: Towards a new research agenda. Journal of Youth Studies, 1–15. doi:10.1 080/13676261.2017.1316363

Wood, B. E., & Taylor, R. (2017 forthcoming). Caring citizens: Emotional engagement and social action in educational settings in New Zealand. In J. Horton & M. Pyer (Eds.), Children, young people and care. New York, NY: Routledge.

Wood, B. E., Taylor, R., & Atkins, R. (2013). Fostering active citizenship in social studies: Teachers’ perceptions and practices of social action. New Zealand Journal of Educational Studies, 48(2), 84–98.

Zembylas, M., & Bekerman, Z. (2016). Key issues in peace education theory and pedagogical praxis: Implications for social justice and citizenship education. In A. Peterson, R. Hattam, M. Zembylas, & J. Arthur (Eds.), The Palgrave international handbook of education for citizenship and social justice (pp. 265-284). London, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Zohar, A., & Cohen, A. (2016). Large scale implementation of higher order thinking (HOT) in civic education: The interplay of policy, politics, pedagogical leadership and detailed pedagogical planning. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 21, 85–96. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2016.05.003

;