Introduction

Background

Waitākiri School in Christchurch was formed in 2014 as part of the larger restructuring of Christchurch schools following the 2010–2011 earthquakes. The new school motto at the time, ‘creating a new community school together’, reflects the significant ongoing psychological and environmental challenges that learners, staff, and families have been facing, including ongoing effects of trauma, new ways of doing things, job insecurities, high staff absences, working across two sites, homes being rebuilt or repaired, and substantial road works.

Following the merger, teachers decided to focus their energies primarily on fostering well-being and rebuilding school community, rather than on education concerns. Daily singing was one of three activities (singing, physical activity, and laughter) that they believed would provide learners with enjoyable ‘brain breaks’ which would in turn prepare them for learning by supporting their focus and attention. Further, singing was a way for the community to be together, and to have fun. Coming together to sing in large groups in studio and whole school community settings ‘felt right’ to all involved.

Despite the significant challenges outlined above, well-being and engagement data indicate that learners continue to feel safe, valued, and supported. Our research examined the factors that enabled the singing programmes to be developed and sustained, and explored teacher and learner perception of the relationship between singing and well-being. Our aim was to maximise the positive impact of singing, and inform other schools about the process and perceived outcomes of daily singing in the classroom.

Our research questions

- What factors enable classroom singing for well-being in Waitākiri School to be successfully developed and sustained?

- How do members of the school community understand the relationship between classroom singing programmes and well-being in our school?

- How can we use our findings to continue to improve singing for well-being in our school?

- How can we use this information to help other schools to successfully develop and maintain singing for wellbeing programmes?

Relationships between well-being and learning

Nurturing school environments are significant contributors to the health and well-being of children and young people (Denny et al., 2011; Seldon, 2013; Viner et al., 2012). In turn, subjective well-being is known to be strongly linked to learning and academic success (Bird & Markle, 2012; Education Review Office, 2015b; Noble & Wyatt, 2008). When learners have high levels of well-being they are more likely to be motivated and engaged

(Christenson, Reschly, & Wylie, 2012; Curry, 2009; Kindekens et al., 2014; Mahatmya, Lohman, Matjasko, & Farb, 2012; Noble & Wyatt, 2008) and when they are anxious or emotionally or physiologically aroused, they are not able to think clearly, lack commitment to their studies and their potential to learn is reduced (Curry, 2009; Kindekens et al., 2014; Noble & Wyatt, 2008).

Learners are happy and flourish in an environment of care that focuses on relationships, and sense of belonging (Averill, 2009; Cavanagh, 2008; Fredrickson, 2009; Seldon, 2013). Teacher-learner and learnerpeer relationships have the greatest impact on learner achievement (Dziubinski, 2014; Swain-Campbell & Quinlan, 2009) and regardless of what is being taught, learners can fail to learn if relationships are not positive (Cavanagh, 2008; Swain-Campbell & Quinlan, 2009). Teachers therefore have a major responsibility to create a culture of care by building and maintaining positive relationships, promoting friendships, and generating happiness in schools (Cavanagh, 2008; Seldon, 2013).

The concept of well-being

Researchers have produced a large number of definitions, models, and measures of well-being (Goodman, Disabato, Kashdan, & Kauffman, 2017). Two broad perspectives have dominated, however. The first associates well-being with happiness or pleasure, while the other aligns it more with assets and meaning (Goodman et al., 2017; Olsson, McGee, Nada-Raja, & Williams, 2013). That is, some theories attempt to explain subjective well-being (‘SWB’) as a result not just of positive feelings about one’s life, but also as a result of the positive functioning of that life (Keyes, 2002; Ryff, 1989; Seligman, 2011).

Weninger and Holder (2013) argue that there is now general agreement that subjective well-being is associated with positive affect, appropriate levels of negative affect, and overall life satisfaction. Satisfaction in this context refers to the cognitive and global evaluation of one’s life circumstances relative to one’s own standard. Dodge et al. (2012) highlight this idea of individual ‘norm’ by proposing that a state of well-being occurs “when individuals have the psychological, social and physical resources they need to meet a particular psychological, social and/or physical challenges” (p. 230). While challenging life events can significantly impact children’s subjective well-being, the magnitude of the impact can be reduced if they have helpful resources to draw on (Furrer & Skiinner, 2003; Kloep, Hendry, & Saunders, 2009).

Three models of well-being

We drew on three models of well-being that have been developed with children in mind. Each of these models includes focuses on positive emotions, individual assets and strengths, and meaning and purpose in life albeit with varying emphases.

Durie (1994)

The New Zealand health and physical education curriculum is underpinned by Durie’s (1994) Te Whare Tapa Wha model of well-being. In this model spiritual, emotional, social, and physical well-being are represented as the four walls of a whare (house). Each of these four dimensions of hauora (health and well-being) influence and support the others, and if one part of the house (or one’s health) is not in order, other parts of the house will be affected. Taha wairua, or spiritual well-being, is about the values and beliefs that determine the way people live, the search for meaning and purpose in life, and personal identity and self-awareness. Taha hinengaro, or mental and emotional well-being, involves coherent thinking processes, acknowledging and expressing thoughts and feelings, and the ability to respond constructively. Taha whānau, social well-being, is about family relationships, friendships, and other interpersonal relationships; feelings of belonging, compassion, and caring; and social support. Finally, Taha tinana covers physical well-being, the physical body, its growth, development and ability to move, and ways of caring for it (Durie, 1994). Physical health, spiritual health, family health and mental health are all considered to be interconnected with individual well-being. All of these dimensions reflect the vision of the New Zealand Curriculum (Ministry of Education, 2007) and Te Marautanga o Aotearoa (Ministry of Education, 2008) that all young people will become “successful, confident, connected, actively involved, lifelong learners”.

Noble and McGrath (2016)

Drawing on the positive psychology and educational literature, Noble and McGrath (2016) have outlined the factors that they believe contribute to student well-being. Their framework includes seven pathways to learner well-being including encouraging ‘Positivity’, building ‘Relationships’, facilitating ‘Outcomes’, focusing on ‘Strengths’, fostering a sense of ‘Purpose’, enhancing ‘Engagement’, and teaching ‘Resilience’ (PROSPER). They suggest learners need to experience positive emotions at school, as well as feeling safe and having a sense of belonging (positivity); the community needs positive relationships (relationships); and learners need to feel as if they are capable and are making progress toward goals, and that if they work hard and are persistent they will achieve results (outcomes). They also suggest that learners need to understand their own strengths and abilities (strengths); that they need to view school activities as meaningful and valuable (purpose); and to feel absorbed, connected and interested in school learning and in school life (engagement). Finally they argue that learners need the capacity to ‘bounce back’ after setbacks, and the courage to deal with challenging situations (resilience).

Noble and McGrath predict that the more PROSPER components that a student is able to access at school, the better their education and the higher their level of well-being and achievement is likely to be.

Education Review Office

The Education Review Office (ERO) suggests subjective well-being is a sustainable state, characterised by predominantly positive feelings and attitudes, positive relationships at school, resilience, self-optimism and a high level of satisfaction with learning experiences. A student’s level of well-being at school is indicated by their satisfaction with life at school, their engagement with learning and their social-emotional behaviour (Education Review Office, 2015b, p. 6).

Extraction of well-being indicators

We extracted key indicators from the above models to create Table 1.

| Well-being indicators | |

| Positivity | Experiencing positive emotions

Feeling safe and cared for Having a sense of belonging Experiencing fun and amusement Feeling appreciative and grateful Feeling optimistic and hopeful |

| Relationships | Having positive relationships |

| Achievement-related outcomes | Feeling capable

Experiencing progress, achievement, mastery Working hard and persisting Feeling satisfied |

| Strengths | Having self-knowledge

Understanding and applying strengths |

| Purpose | Feeling connected to something greater than oneself

Believing school activity is valuable |

| Engagement | Feeling connected to, absorbed in and interested in activities |

| Resilience | Having courage in challenging situations

Bouncing back after setbacks and mistakes |

| Identity | Having positive identity |

| Physical | Being active

Feeling healthy |

Singing and well-being

The New Zealand government recognises that learning in, through, and about the arts “stimulates creative action and response by engaging and connecting thinking, imagination, senses, and feelings” and that “by participating in the arts, students’ personal well-being is enhanced” (Ministry of Education, 2015). Music leaders in New Zealand primary schools report benefits of musical participation in terms of “children’s developing identities as members of a community of musicians, strengthened relationships over time between children and teachers, individual children’s improved engagement with school and learning … and an enhanced school culture and community” (Boyack, 2011).

Researchers are showing increased interest in the social and cultural effects of group singing (Clift, Hancox, Staricoff, & Witmore, 2008; Mellor, 2013), and note that singing can lead to a sense of connectedness, strengthen communities, and contribute significantly to social capital building (Hinshaw, Clift, Hulbert, & Camic, 2015; Theorell & Kreutz, 2012). Typical populations have described group singing as a joyful activity that promotes well-being and is life enhancing for those involved (Judd & Pooley, 2014). Group singing can increase participants’ sense of self-worth, and support the development of social skills and wider social networks (Bailey & Davidson, 2002, 2005) which in turn lead to increased positive affect (Clift & Hancox, 2006).

The value of participating in group singing has also been highlighted in studies involving specific groups of people who are marginalised (Bailey & Davidson, 2005) homeless (Bailey & Davidson, 2002, 2005) or have experienced adverse events (Gao et al., 2012; von Lob, Carmic, & Clift, 2010). Singing is considered to be an important resource for people who have experienced trauma, to elicit positive emotions, energy, and feelings of safety; to restore hope and motivation; and to develop relationships (Cheong-Clinch, 2009; Gao et al., 2012). In addition to psychosocial benefits (Clark & Harding, 2012; Clift & Hancox, 2006; Judd & Pooley, 2014; Kirsh, van Leer, Phero, Xie, & Khosla, 2013; Livesay, Morrison, Clift, & Camic, 2012), singing has been shown to enhance immune functioning (Beck, Cesario, Yousefi, & Enamoto, 2000; Clift & Hancox, 2006) reduce stress and improve mood (Grape, Sandgren, Hansson, Ericson, & Theorell, 2003; Kreutz, Bongard, Rohrmann, Hodapp, & Grebe, 2004); and facilitate physical relaxation and enhance breathing and posture (Clift, Hancox, & Morrison, 2010).

Nevertheless links between school-based music and psychosocial benefits are complex, difficult to measure, and not yet well understood (Clark & Harding, 2012; Crooke, Smyth, & McFerran, 2016). The results of studies with professional, amateur, and community groups, and with participants across the age range, point to group process, the relationships between group leaders , and the relationship between group participants, as important variables (Mellor, 2013). It seems the potential for singing to improve health and well-being involves more than the act of singing itself. Health affordances are generated and mediated by relationships between singers, the songs they sing, and the ways the singing is facilitated.

RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

Action research

Ours was an Action Research (AR) project. Action research in education is systematic, oriented toward positive change in the school community, practitioner-driven, and participatory (Hine & Lavery, 2014; Mertler, 2010). Our core team of Daphne and Robert (Victoria University of Wellington) and Dianna (Deputy Principal at Waitākiri School), collaborated with 10 teachers and 20 learners through different phases of the research, sharing decision making and control, to ensure our work was relevant, was respectful of the school, classroom, and community culture, and that our findings could be readily incorporated into practice and have maximum impact on well-being. Individuals’ strengths were utilised as appropriate to identify the issue for investigation, refine the issue, plan the research methods, collect and interpret data, decide the action that needed to be taken, and the way the findings would be produced and disseminated (Israel, Eng, Schulz, & Parker, 2012).

We constantly evaluated the effects of our intervention through cycles of critical reflection and dialogue, leading to further or alternative action (Cardno, 2003). Each cycle involved planning (identifying and limiting the topic and gathering preliminary information), acting (implementing the plan, collecting data, and analysing the data), developing an action plan, and reflecting on and discussing the results (Mertler, 2010). Specifically we began to critically appraise and engage in more explicit reflection on our music initiatives. Over several cycles of learning we asked ‘what did we do?’, ‘how did the children respond?’, ‘so what?’/’what does this mean?’, and ‘what will we do next?’. (See Appendix 3: Action research cycles).

Methods

Data Gathering

Data were gathered from teachers’ journals (Google Docs); children’s artworks and videos; individual interviews and focus groups with teachers and children; and well-being surveys. One of our teachers designed a template (“this is me singing”) for all children in the participating learning studios to complete. The template invited them to draw a face, fill in a speech balloon, and give the picture an additional caption.

Five of our teacher researchers – one music specialist, two musically confident teachers, one less musically confident teacher, and our kapa haka tutor—participated in individual interviews.

Analysis

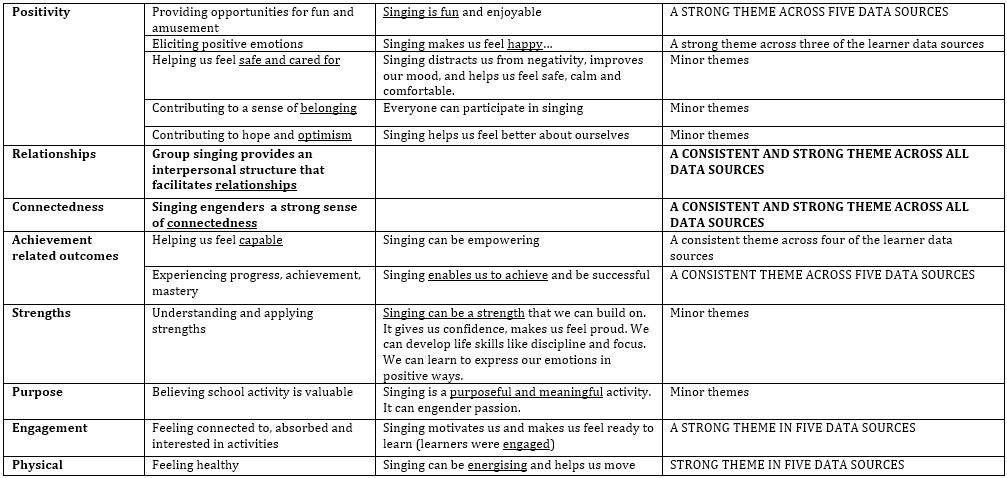

We used a constant comparison method of data analysis outlined by Mutch (2015). Inductive thematic analysis was applied independently to each set of data, after each cycle of learning. Codes, categories, and themes were allowed to emerge rather than searching for them according to a predetermined model. Themes from each cycle were then compared and contrasted to uncover central themes.

We also compared and contrasted three models of well-being outlined in the literature to extract key indicators (Durie, 1994; Education Review Office, 2015c; Noble & McGrath, 2016) (see Three models of well-being, p. 3) Then we engaged in deductive analysis, looking for the relationship between key indicators and our core themes (see Appendix 2: Themes).

Twenty learner researchers analysed the data from artworks, with adult support. All learners were invited to express interest in this task, parental consent was sought, and the first 10 learners from each studio who returned both parent and their own consents to their teacher were included. We made it clear that not everyone could take part, and that those who did agree to participate could pull out at any time prior to the focus group taking place, with any repercussions.

The procedure involved the 200 pieces of artwork being divided equally among four groups of five learners. Each group was supported by an adult experienced in interviewing children. The learners were asked to look at each piece of artwork and to talk about “what the pictures and stories about singing are telling us”. Adults encouraged children to take turns to contribute, making sure that different children were able to begin the conversation. Adults also helped learners to add to the conversation by asking them what they thought about what had been said, whether they agree, or whether they might have a different idea. Occasionally more specific prompts were necessary, such as “what do you think singing has to do with sport?” (see page 19). The learners sorted the data into self-determined predominantly binary categories (‘likes’/’doesn’t like’ singing), with some variation (e.g. ‘happy’, or ‘dancing’). The primary data came from the discussion which was recorded and subsequently thematically analysed. The following examples demonstrate the care they took with this task.

She’s playing hockey or golf and this, and she … she … she’s like the other person who really likes singing and is overjoyed and cheerful and always likes singing … I think we should put it … put it in the happy place ‘cos it shows the words and the pictures and her face looks like she’s all happy and she really likes singing.

Learner researcher, focus group

With this one it looks like the person does not like it. ‘Cos it says ‘I feel sad when I sing music because it is so loud’. And then there’s a picture of somebody blocking his ears saying ‘Stop it’. So I will put this in the ‘I do not like it’ pile.

Learner researcher, focus group

Child 1: (This one says) … ‘When I sing it, I feel happy’ … ‘But I don’t like any of the songs’. I think this means the person that did it, doesn’t really like to do singing.

Child 2: … um he doesn’t like it at all. He or she.

Child 1: Mm . People don’t like Brussels sprouts and it has a picture of a Brussels sprout.

Children discussing a peer’s picture

Findings

Section 1 of our findings describes the factors that have enabled singing to be developed and sustained in our school, what we learnt about facilitation, and how we improved our practice over the period of the research.

In Sections 2 and 3 we present the results of our well-being surveys, and outline the perceived relationship between group singing ‘brain breaks’ and well-being.

In Section 4 we present our model highlighting the links between singing and psychosocial well-being from the children and teachers’ perspectives. We have included examples of learner’s artefacts (‘this is me singing’) throughout, to illustrate the findings.

SECTION ONE:

Factors that have enabled the singing to be developed and sustained

Our initial focus group highlighted six themes about how to manage and sustain singing for well-being approaches. From there we recorded our observations and reflections in Google Docs to see how well we were really doing, and to find out what we might improve on. We explored the value of teacher or child song choice; repetition of songs; song difficulty/ease of access; and the value of live accompaniment (see Appendix 3: Action research cycles, p. 33). Teachers also focused their spirals of inquiry on singing, building on research discussions and activities.

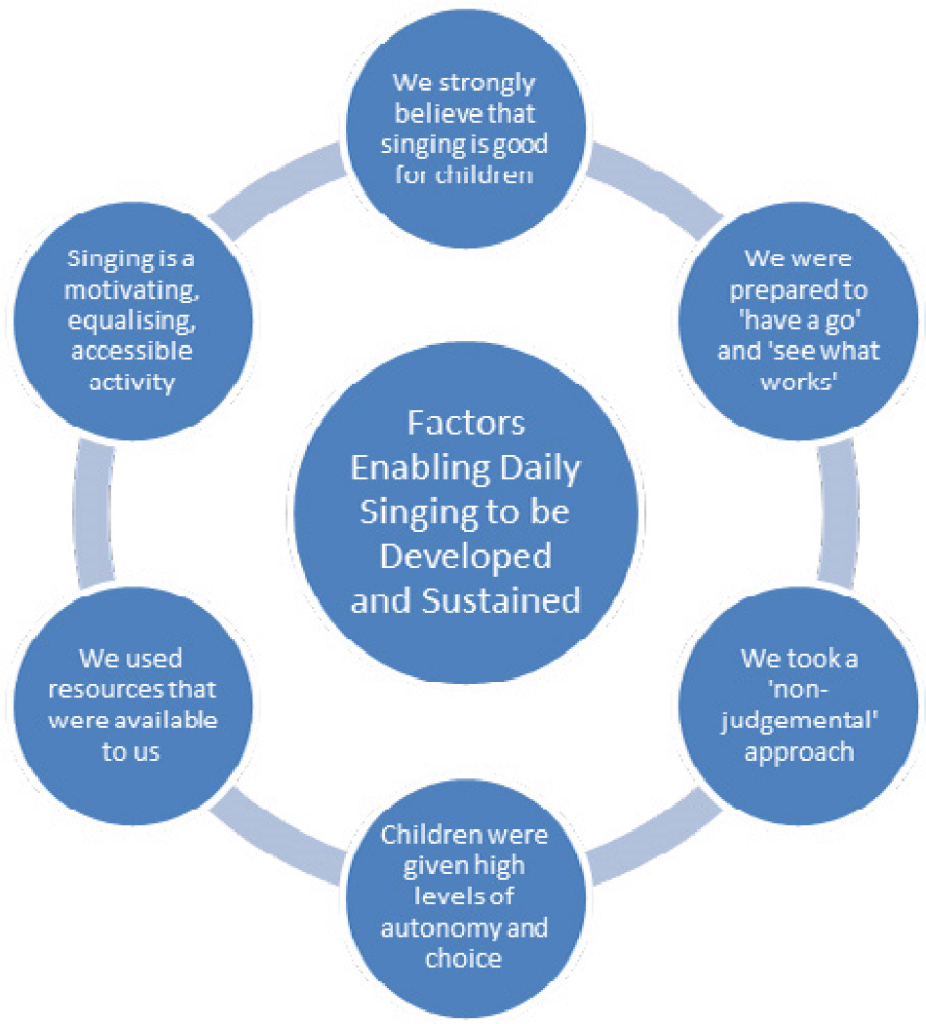

Figure 1: Factors enabling singing for well-being to be developed and sustained (initial findings)

In the beginning we uncovered six themes:

1.We strongly believed that singing would be good for our learners’

2. We were prepared to ‘have a go’ and to ‘see what works’’

3. Singing is a motivating, equalising, accessible activity’

The classroom-based singing ‘brain breaks’ “need to be quick and seamless”. The focus is on having fun—it is just “pure spontaneous enjoyment”. It was important to us to have an activity that everyone could participate in, and we recognised that singing was an activity that “anyone could do anywhere at any time”. Our kapa haka (Māori performing arts) tutor explained that for Māori and other cultural groups, singing is just part of life.

Singing has gone on for generations and generations. We go back to our pā scenario, our village scenarios, where we all have our community songs—when you go out into the wider world you have your own children and you keep those songs together by getting together with your iwi and people.

Kapa haka tutor, Interview

While we made sure we had daily ‘brain breaks’ when all children would sing together, we noticed that children were singing in a range of environments at a variety of times across the school day. Music had become a ‘natural’ part of our school environment with children singing spontaneously in the playground, and eagerly participating in the range of music activities that are on offer.

It’s fun, because they’re really good pieces of music, and it’s just like a rest for your brain.

Learner researchers’ focus group

4. We used the resources that were available to us

Our singing was mostly supported by YouTube clips with lyrics shown on a big screen, although one of our teachers sometimes accompanied with guitar and very occasionally we sung unaccompanied. One of our teachers also used a book of printed lyrics from time to time. Later we recognised that using live instead of recorded accompaniment could rejuvenate familiar music.

We recognised that our specialist music teacher and kapa haka tutor were crucial resources, because they were addressing children’s music learning needs giving us the flexibility to conceptualise singing for well-being another way. We value music education highly, but believe that singing for well-being needs to be facilitated differently (see theme 9).

5. Children were given high levels of autonomy and choice

We enabled children to choose the songs they would sing, and how they would participate. For example, sometimes children would listen or move while others were singing. We encouraged them to enter their favourite songs into Google Docs, and vetted them to ensure the lyrics were appropriate before producing a playlist.

During our ongoing cycles of learning we reflected on the children’s’ song choices to determine whether the lyrics were appropriate; the cultural relevance of their choices (e.g. was the song valued by family/s; a popular New Zealand song; considered to be ‘cool’ song); and how the children were managing the technical aspects of the song (e.g. was it fast, slow, high, low; was there a lot of repetition; were the lyrics easy to sing).

We observed that our learners appreciated being given the ‘reward’ of being able to choose a song. However, while we believed that allowing children to choose what they wanted to sing was important we recognised that they could only choose from songs they already knew, or had at least heard somewhere; and that the songs they chose were sometimes hard for them to sing.

Teachers therefore began to choose repertoire, putting together a bank of songs, which included well-known children’s songs as well as some of our favourite older songs. We noticed that it was helpful to include variety and surprise and that children can be enthusiastic about a wide variety of genres. The learners generally had a positive attitude towards engaging with new material, and enjoyed singing children’s songs and their teachers’ favourite songs, as well as popular modern material.

6. We took a non-judgemental approach

We emphasised the importance of being non-judgemental. We wanted singing to be a fun activity, where children felt no pressure to perform. However, when we began to look closely at our singing, we noticed that children responded well to opportunities to become familiar with most of the repertoire (i.e. to practice), and often seemed more focused when they knew the songs well. We decided to enable children to become more familiar with songs by focusing on just a few.

Subtheme: We practised and achieved success

While we recognised that singing for well-being needs to be fun, we also felt the need to practise and achieve success. We deliberately avoided putting too much overt emphasis on music ‘learning’ yet recognised that content can be challenging and that practising until the children knew the lyrics was important, at least some of the time. Learners will work hard to participate in singing because they are passionate about what they are being asked to engage with. Singing for well-being can bring feelings of success and achievement, and can lead singers to seek more formal singing (or other music learning) opportunities. We were also aware that our kapa haka programme challenged children to perform at a high level while still seeming to contribute significantly to their well-being.

It gets you focused on what you need to do. We go through trials and tribulations of practising for that long, in that way, to get to a stage of making mistakes, and then knowing that it’s ok to make mistakes. We can learn from those. And we teach (the tamariki/children) that that’s the reason why we practice and try to be focused like that so we can reach our goal. And the goal is to stand, have fun, sing and not make any mistakes.

Kapa haka tutor, Interview

We learnt that children don’t necessarily have a sense of being ‘judged’ even when they are involved in preparing for and performing in competitions. Rather, they focus more on the positive aspects of being part of a group. Direction or encouragement (from teacher and/or peers) can motivate children’s participation further.

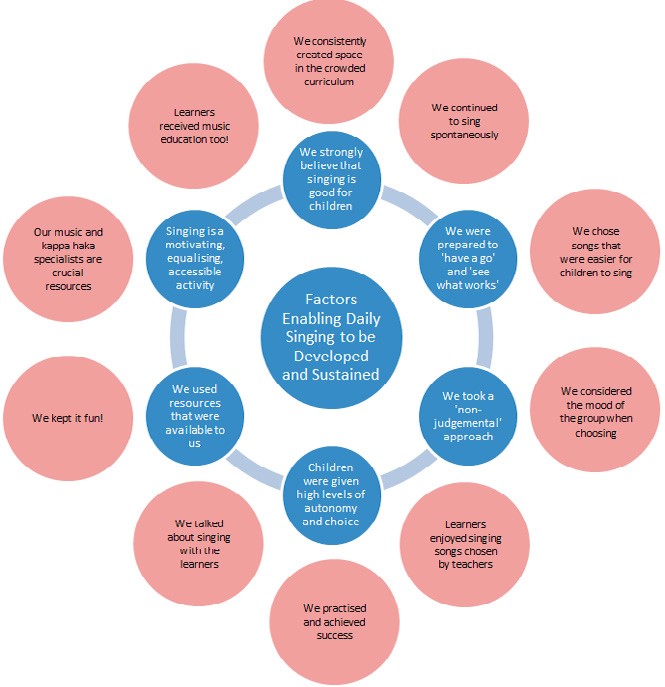

After examining our facilitation more closely…we uncovered further themes:

7. We fostered connection and a sense of belonging

We encouraged a sense of connection and belonging by acknowledging the relationships between the songs that learners chose, and other aspects of their lives. For example, we would ask them about where they had found the song, and whether other family and friends also liked it. We talked with them about the stories their

songs were telling and drew attention to the inspirational lyrics they brought. We helped them to acknowledge that their songs were recognised and appreciated by others, or alternatively to value their unique musical taste. All of these things helped us to understand each other better. We noticed that learners “owned” their music and were proud when others joined in with it. This helped them to develop their confidence, and sense of identity and belonging.

As teachers began to choose more of the repertoire, learners were facilitated to request, engage with and express appreciation for the ‘older’ music that their teachers enjoyed.

Sharing our music was a way of learning about and connecting teachers and learners, and the relationship between dyads was enhanced. We also highlighted the fact that we were able to all be together in one large group for singing. It was something everyone could do at the same time, and we were synchronised not only with our voices but also with our bodies as we danced to the singing. The livelier songs energised the learners and when they were singing they invented action sequences and followed each other’s’ movements in a synchronised way. We therefore noticed that we felt connected when we sang as one, even when we didn’t talk about the songs.

We modelled that singing is a social activity that teachers, learners, families and friends ‘just do’ together. We talked about how music helps us to celebrate, takes us on journeys, and brings back memories; and how we can be connected us through our shared memories, experiences or feelings.

8. We considered the mood of the group when choosing songs

It was not always easy to decide the ‘best’ song to introduce at any given time, but we learnt it was important to consider the mood of the group when choosing songs. We increasingly chose songs according to whether the general mood of the group was ‘up’ or ‘down’. We noticed that group mood could alter within very short time frames, and energy levels would increase or decrease in response to the music. Children seemed to sing and move more readily when ‘bouncier’ songs were introduced, for example.

I like (singing) because um … sometimes I’m sad when I go to school but it like, brightens my day if I’m sad. And also at the end of the day ‘cos I kind of feel sad when I’m leaving school, it makes me happier

Learner researchers’ focus group

Naturally, not all of the children liked all of the songs all of the time, and were less likely to sing songs that did not appeal to them. One of the dads shared that his son prefers not to sing songs that make him remember sad times. “That’s the way it works for him. The songs that he does choose, he loves to sing because they make him feel happy”. Naturally children can have different responses to music. A learner explained “Some songs make me emotional. Some songs make me happy. Some songs make me want to dance”. We even had a sense that boys and girls responded differently to various repertoire, but had no opportunity to explore this possibility in depth.

9. Our children receive music education, and this is different to singing for well-being

During our research process we recognised increasing tension between ‘just singing’ and ‘examining the process of singing’, and we began to question whether and how singing for well-being might align with music education. The following statement emerged following a collaborative focus group activity.

Singing for well-being is associated with high levels of choice and is less structured than music education programmes. People participate on their own terms with a positive attitude and gain confidence because there is no pressure and few expectations. It is the antithesis of specific, structured programmes which have targeted testable outcomes. It avoids engaging with the ‘science’ or ‘technical aspects’ of music; such as learning to read, understand, and critically analyse music, and developing a musical vocabulary. It is not concerned specifically with learning to sing; improving skills, progressing, producing and perfecting a musical product.

Teachers’ focus group

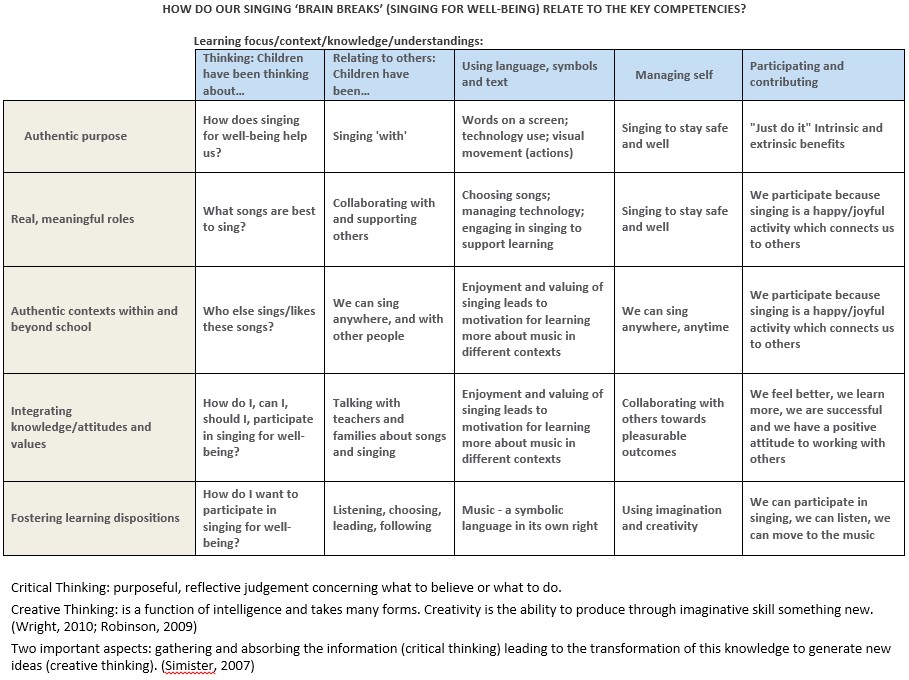

The overview of the New Zealand arts curriculum (online at TKI.org.nz) states that students will explore, refine, and communicate ideas as they connect thinking, imagination, senses, and feelings to create works and respond to the works of others. The music (strand of the Arts) curriculum emphasises the need for learners to actively develop their ideas and knowledge by identifying, describing, comparing, contrasting, investigating, researching, analysing, and evaluating music. They are encouraged to express what they have learnt by presenting, representing, or recording work they have prepared, developed, created, structured, interpreted, and/or refined. On the other hand the potential for them explore, express, create, and respond to music, and to consider and reflect on their music making, with less emphasis on measurable outcomes, is not so pronounced. Nevertheless, the way in which the singing ‘brain breaks’ were facilitated is likely to have contributed to learners’ abilities to describe and compare songs, and to develop more of an understanding about singing as a social resource. Moreover, we found important links between Singing for Well-being and the Key Competencies. During the singing brain-breaks learners were thinking, relating to others, using language, symbols and text, managing themselves, and participating and contributing (see Appendix 1: The relationships between Singing for Well-being and Key Competencies).

Our teachers strongly agreed that there is room for more structured and formal learning alongside creative and social music making. They acknowledged that it was important for the children to believe they could be successful at singing and to gain a sense of achievement which would in turn sustain their engagement in music. However, despite being committed to daily singing, six of our eight classroom teachers did not consider themselves to be musicians, were not confident singers, and did not believe they had the necessary knowledge and skills to teach music in the classroom. They maintained that all teachers have some subjects they are not so good at and “it’s easy to let them go, especially when the primary focus is on reading, writing, and maths”. To that end, they argued every primary school should have a specialist music teacher.

Adjusting to flexible learning spaces

The new school design comprised flexible learning spaces including large studio learning spaces. A literature review by Blackmore et al. (2011) found that on the whole teachers enjoy flexible learning spaces, yet the first few years after moving can be difficult (Sigurðardóttir & Hjartarson, 2016). Significant preparation is required for effective transition, and the potential exists for teachers to revert to ‘the way we used to do things’. Teachers can be worried about levels of noise and managing classroom behaviour and there can be dissonance between the ways teachers and learners anticipate and then experience these new spaces (Blackmore, Bateman, Loughlin, O’Mara, & Aranda, 2011). A significant shift in school culture in order to encourage exploration of innovative pedagogies and careful implementation of the change process are both necessary, to ensure members of the community share and commit to the new vision and have the resources they need to implement it (Sigurðardóttir & Hjartarson, 2016).

Staff at Waitākiri put a lot of time and energy into learning about and adjusting to the studio learning environment. The environment was new to teachers and children alike and we wondered if the setting was supporting or challenging the facilitation of singing. Only one of our teachers suggested that you “don’t get the same connection with 120 children” while three others felt the higher number of children in the studios was making a positive difference. It seemed it was easier to facilitate because children were more willing to sing out.

There is safety in a big group to express yourself without standing out … Everyone else is here with you.

Teacher, Individual interview

(Singing) makes me feel happy when I’m sad… It’s fun. And like … It’s fun with the whole class. Like … it’s like more fun when you’ve got more people and it’s not that fun when it’s just like 28 people in one class.

Learner, Focus Group 2

SUMMARY OF FINDINGS (Section 1)

We concluded that perceived separation of ‘singing for well-being’ and ‘music education’ can diminish the potential for music education to be acknowledged as a rich human experience which should be a fundamental entitlement for children. However, ‘singing for well-being’ needs to focus on the needs of the school community and the resources that are currently available. At Waitākiri School the daily singing was able to be developed and sustained because teachers strongly believed that singing would be good for learners, were prepared to ‘have a go’ and to ‘see what works’, and to use the resources that were available to them. The focus was on having fun rather than the development of singing skills and children were given high levels of autonomy and choice. Singing is a motivating, equalising, accessible activity. Following the earthquakes, singing was a way for the community to be together, to have fun, and to maintain and develop a sense of connection.

Figure 3: Factors enabling singing for well-being to be developed and sustained (expanded findings)

SECTION TWO:

Well-being measures

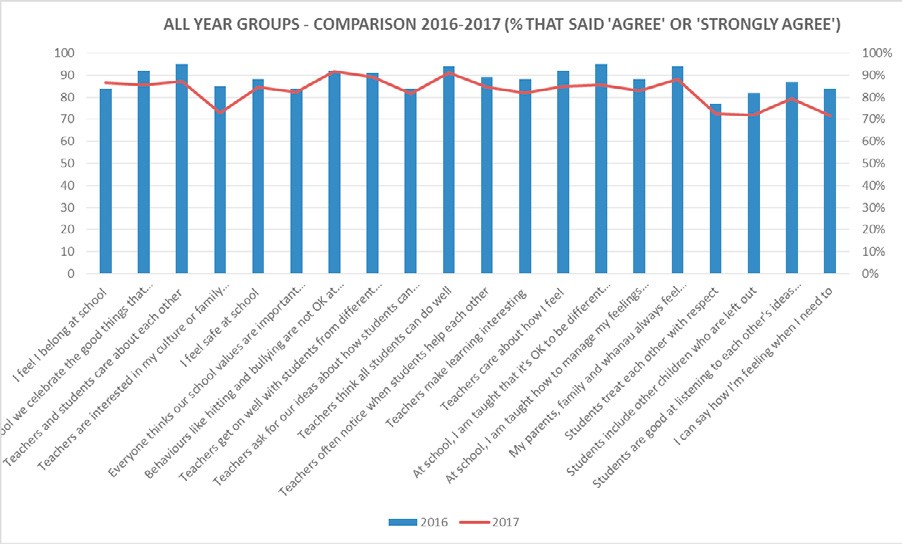

Well-being measures were taken from the Wellbeing@School toolkit. The purpose of these survey tools is to support schools to engage in evidence-based self-review, by helping them to determine the extent to which their various school practices promote a safe and caring school climate. It is important to note that the toolkit is primarily used to measure change in specific targeted areas for each school. Moreover, to gather meaningful comparative data, surveys need to be completed at the same time each year over periods of 3 to 5 years. For our study the survey was administered to all students at Waitākiri School in March 2016. A shortened version including key questions (see Appendix 3) was administered in Term 3, 2017). The graph below is presented as an indication of where well-being scores were during the period of the research.

Scores indicate the percentage of children who answered ‘agree’ or ‘strongly agree’ to the questions.

Figure 4: Well-being scores at March 2016

Overall, while there are things that the school can continue to work on, these results are encouraging. They suggest the school community is continuing to do well in terms of maintaining psychosocial well-being, especially given the ongoing challenges that staff and learners are facing.

Positive results amid ongoing challenges

At the end of 2016 we acknowledged that despite maintaining relative high levels of well-being, teachers and learners in our school community were still experiencing significant challenges in terms of the ongoing impact of earthquakes, and the move to a new school. Further, in 2017 we had a change of leadership within the school, which added to workloads and potentially compounded feelings of instability. While we did not specifically investigate teacher well-being at our school, findings from recent research focusing specifically on the Christchurch situation suggests that many teachers in this city will be continuing to experience emotional exhaustion and burnout (Kuntz, Naswall, & Bockett, 2013; Mutch, 2015).

SECTION THREE:

The perceived relationship between group singing brain breaks and well-being in our school (learners’ perspective)

Artefacts were produced by 196 children (170 indicated that singing had a positive influence on them, nine were negative, and 17 neutral)[1]. They used 46 different adjectives (278 in total) to describe how singing makes them feel.

Learners overwhelmingly communicated that when they were singing they experienced positive affect. ‘Happy’ was reported 99 times, ‘good’ 19, ‘joyful’ 16, ‘boosted’, ‘pumped, ‘energetic’ or ‘bouncy’ 13, ‘amazing’ 13, ‘excited’ 11, ‘fantastic’ 10, and ‘awesome’ 10. They shared that singing could help them to improve their mood, and to feel well.

Child 1: I know why music is good for you.

Interviewer: Tell us.

Child 1: When you’re singing you’re reading the songs, so it’s like you’re reading.

Child 2: Its fun singing.

Child 3: Singing’s good because with singing if you’re happy you’re able to learn more. … If you’re in a grumpy mood it’s going to be harder for you to learn and focus.

Learner researchers’ focus group

If you talk through the songs the teachers always get really mad and say we only did brain breaks so that we release the endorphins. And you can tell. Because when (children) are singing they seem happier than if we’re just talking.

Learner researchers’ focus group

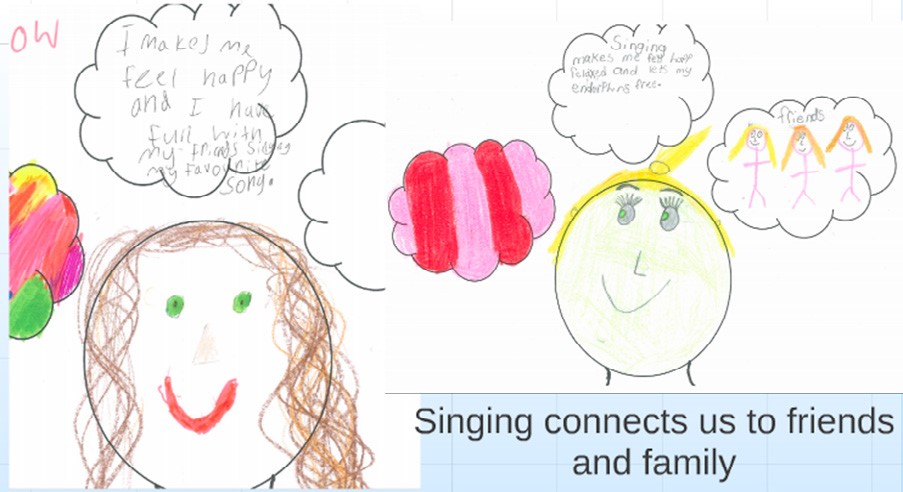

Learners recognised that singing connected them to teachers, friends and family, reporting that they had fun with their teachers during singing. Many of the girls’ drawings in particular depicted happy people singing together, and some explicitly explained that singing was better when they did it with friends.

It makes me happy and I have fun with my friends singing my favourite song

Artwork caption

And there’s one funky teacher that likes singing. Mrs A and Mr B …They, they both dance outside the room

Learner researchers’ focus group

Some learners reported that singing—and listening—helped them feel calm, safe, and comfortable, and “stopped (them) from feeling stressed out”. It provided a “rest for (their) brains” which helped them to learn. They also said singing can be exciting. It can affect their energy levels (usually energising), and often makes them feel like moving and dancing. They also reported that singing can make them feel proud. It can engender passion (make them want more), ambition (make them believe they can do more) and can be inspirational (encourage them to do more) and for some was considered empowering (they knew they could do more). Singing gave children a sense of achievement (“we did it!”).

Singing makes me happy because it makes you feel like you’re in your favourite place

Learner researchers’ focus group

I love singing lots and lots. It makes me feel safe

Artwork caption

Like it just … it gets my, it gets my brain … like it turns on my brain.

Learner researchers’ focus group

(Interviewer and children looking at one of many pictures that included reference to sport)

Interviewer: What do you think singing’s got to do with sport?

Child 1: It gives you energy to go out and run.

Child 2: It seems like (they are drawing) what they enjoy doing… so it might mean that they really enjoy music.

Learner researchers’ focus group

I feel happy because we do it every morning and it gets the day started. … ’Cos it gets me … ’cos singing gets me … um, excited

Learner researchers’ focus group

I think (this picture) means she’s super, super, really, really, very, very, super (breathe), overjoyed, likes, really likes singing … And she’s dreamed of being a singer and really loves it and sings it all day and night. Learner researchers’ focus group

It makes me feel positive and strong like I can do anything. It makes me feel happy and encourages me to do things that I can’t do yet.

SECTION FOUR:

Our model highlighting the links between singing and psychosocial well-being from the children and teachers’ perspectives

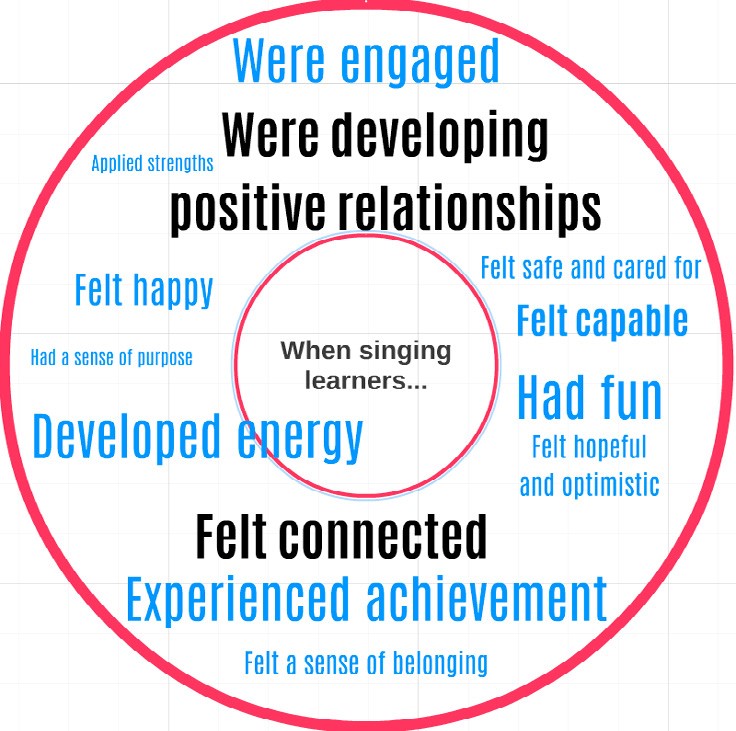

Our findings suggest that group singing is a fun and enjoyable activity that everyone can participate in. It elicits positive emotions and engenders a strong sense of connectedness. It is energising and helps us move. It can distract us from negativity, improve our mood and help us to feel safe, calm and comfortable. As a purposeful and meaningful activity it can be empowering. It helps us to feel better about ourselves, motivates us, and helps us feel ready to learn. It can be a strength that we can build on giving us confidence and feelings of pride.

Figure 5 captures keywords from our themes that have also been identified as indicators of well-being. The text size is varied to provide an indication of the strength of each theme (see Appendix 2), but is not a statistical representation.

Figure 5: The perceived relationship between singing and well-being

DISCUSSION

LIMITATIONS OF THE STUDY

Our research is focused on the experiences of just one school community, and we were confronted with unique circumstances. Therefore, our findings cannot be generalised to other schools.

Moreover, we cannot claim that the high levels of well-being experienced by learners at Waitākiri School is solely due to singing. Our baseline measures of well-being were already positive, and this may have been due to the resilience that was already being afforded by well-being initiatives (including singing) that the school had in place. Children who demonstrate significant symptoms of trauma are likely to experience a higher magnitude of benefits than those who already have reasonable levels of psychosocial well-being (Hinshaw et al., 2015b).

Our indicators of well-being were generated from descriptions of three existing models, and we acknowledge that other models may have different emphases. Further, the well-being data we collected does not allow us to compare changes over time. Nevertheless, by analysing data from several diverse sources, we have been able to provide a rich description of practice and to demonstrate important links between singing and indicators of well-being.

IMPLICATIONS FOR PRACTICE

Implications for practice in ‘typical’ schools

There is an urgent need for mental and emotional well-being support in New Zealand schools, especially for students with mental health issues (Boyd, Bonne, & Berg, 2017). Our findings demonstrate important links between classroom singing and well-being, suggesting all primary school teachers should have the resolution to ‘just do it’.

The National Administration Guidelines for schools reflect the general consensus that providing a caring, safe and respectful school climate in which learning can flourish should be a key priority for New Zealand educators (Cavanagh, 2008; Education Review Office, 2015a; Seldon, 2013; Viner et al., 2012). Singing in the classroom can be adopted as a proactive approach to well-being, strengthening protective factors that act to “enhance the likelihood of positive outcomes and lessen the likelihood of negative consequences from exposure to risk” (Boyd et al., 2017). Further, the potential for singing to support learners’ development of Key Competencies should provide additional impetus for primary schools to introduce daily singing in the classroom.

Singing is one of the most accessible ways for a teacher to conduct a music programme (Heyning, 2011), yet daily singing is rarely reported in New Zealand primary schools. Like our teachers, many others believe they cannot sing; or that can’t sing well enough to introduce classroom singing (Heyning, 2011; Pascale, 2013; Rogers, Hallam, Creech, & Preti, 2008). While music specialists are important, it seems crucial to ensure that generalist classroom teachers are able to engage learners in regular, if not daily, singing. Our findings suggest that even with poor self-efficacy, teachers are able to engage learners in singing by taking the focus away from music learning—and that this practise can have positive outcomes.

The practice of ‘non-formal’ music education in the classroom might support the development of lifelong musical learning (Higgins, 2015), as well as school well-being. While there is currently little evidence regarding the impact of formal classroom music education on psychological subjective well-being (Crooke & McFerran, 2014; Rickard, Bambrick, & Anneliese, 2012), more convincing evidence can be obtained from programmes which focus specifically on therapeutic benefits as ours did. This focus is not easily accommodated by formal music education programmes. Rickard, Bambrick & Anneliese (Rickard et al., 2012), reinforce our teachers’ argument that disconnection from a curriculum context may be necessary to facilitate sufficient engagement. We agree with researchers who suggest the potential for positive outcomes is mediated by competitive environments (Gembris, 2012; Grape et al., 2003; T. Hinshaw, S. Clift, S. Hulbert, & P. M. Camic, 2015; Hylton, 1981; Kirsh et al., 2013). Singing is more likely to have positive effects on health if it is not practised under the permanent pressure to bring about musical excellence (Gembris, 2012).

Implications for schools responding to traumatic events

Following the Christchurch earthquakes schools clearly needed to adapt their services and curriculum to respond to the emotional and learning needs of their learners (Education Review Office, 2013). Waitākiri School made a concerted effort to ensure their programmes were designed and delivered specifically to target wellbeing. Our teachers insisted the focus should be on being together and having fun, rather than on music education. This intuitive response was critical, since Crooke and McFerran (2014) argue that when aiming for psychosocial well-being benefits, activities which focus on musical ability (such as perfecting singing for performance) should be avoided unless specifically requested by participants. Skill-based music activity may even lead to increased anxiety and limited psychosocial benefits with vulnerable populations (McFerran, 2010). In contrast, activities that focus on expression and fun should be encouraged to enable learners to experience music as engaging, enjoyable and useful in terms of communicating feelings (Crooke & McFerran, 2014).

Other conditions that Crooke and McFerran (2014) refer to, include the need to consult with school communities when planning, to identify existing commitments and needs, as well any resources or school structures which may impede or support a project. These authors’ situate their writing primarily in the context of schools that have asked for support with music programmes to address specific well-being concerns— programmes that might be facilitated by music therapists. In our situation, our whole school community was affected by earthquakes, all agreed that singing was something that was likely to help, and agreed to ‘give it a go’. Learners, teachers, administrators and the wider community were well aware of the issues that they were all facing, and the limited emotional resources that were available to them. Focusing their energies on fostering well-being and rebuilding school community by coming together to sing ‘felt right’ to all involved.

When communities are vulnerable over an extended time frame, they experience stress collectively, appraise collectively, and respond collectively (Ebersohn, 2012, p. 30). Instead of a fight, flight, or freeze response, they might ‘flock’; connecting to access, share, mobilise and sustain use of resources. This solidarity can counter ongoing risk and support positive adjustment; that is, resilience can occur as a transactional-ecological process (Ebersohn, 2012, p. 29). In challenging contexts such as our post-Christchurch earthquake environment, it is important for communities to feel as if they have some control; that they can see the risks, make collective decisions on how to respond, and take action, rather than feeling passive and overwhelmed. In our situation singing provided the opportunity for a positive collective relational response.

Well-being in schools is enhanced when leaders have a clear vision of what student well-being means in their context, and can cultivate a positive school climate based on values determined, understood, and shared by the community (Education Review Office, 2016a, 2016b). Following the earthquakes, Waitākiri School staff and learners were completely focused on their shared vision of ‘building a new community together’. Together they learnt about the potential for singing, humour and physical activity to enhance well-being; and together they planned and implemented the singing programmes. Boyd, Bonne & Berg (2017) present data that suggest few New Zealand primary and intermediate schools consult students about new ways to foster well-being, or seek their input when developing approaches to well-being. Our singing programmes were strongly underpinned by mutual purpose, and had a significant focus on student autonomy and choice. The opportunities students had to ‘lead’ the singing programme would have contributed to their sense of belonging, and to their emerging competencies to contribute to others’ well-being (Boyd et al., 2017).

Conclusion

The Waitākiri School community has been able to develop and maintain daily singing programmes when conditions for well-being have been severely compromised. The community continues to experience significant stressors and while well-being can fluctuate, overall scores have remained relatively high. Many things are likely to have contributed to the sustained well-being that learners experienced. However, given the encouraging reports from children, particularly with regard to affect, energy, and connectedness, it seems highly likely that singing had a positive impact on well-being. This success has a powerful message for wider education communities facing similar long-term challenges. Classroom singing, as an activity that can occur naturally in the classroom as both curriculum and therapeutic practice, can be a pragmatic way to address well-being in schools.

Moreover, music making which is not necessarily undertaken for the purpose of music education as it is traditionally understood, can be used to support and nurture the social, physical, and mental well-being of young people who are vulnerable and at-risk (Cheong-Clinch, 2009). In challenging contexts such as our postChristchurch earthquake environment, singing provides opportunities for communities to engage in a positive, collective, relational response. Developing a culture of music in the schools, and tailoring music programmes to meet the needs of school communities, may be key to improving or maintaining learner well-being, especially in times of crisis (Rickson & McFerran, 2014).

Footnote

- Unfortunately the artworks were submitted anonymously, so possibilities of exploring strategies to assist learners who held negative views were limited. One learner who indicated his ‘ears hurt’ during singing was more easily identified and was provided with noise reducing headphones to support his participation in singing. ↑

The team

Dianna Reynolds is Deputy Principal and music specialist and coordinator at Waitākiri School. Dr Daphne Rickson (New Zealand School of Music, Victoria University of Wellington) is university lecturer, researcher, and music therapist. Dr Robert Legg (Victoria University of Wellington) is a university lecturer, researcher, and music educator.

Publications

Journal Articles

Rickson, D., Atkinson, D., Reynolds, D., & Legg, R. (2019). “Let the people sing!” Action research exploring teachers’ musical confidence when engaging learners in ‘singing for wellbeing’. Journal of Teachers Action Research, 6(1), 44-62., Accepted May 2018.

Rickson, D., Legg, R., & Reynolds, D. (2018). Daily singing in a school severely affected by earthquakes: Potentially contributing to both wellbeing and music education agendas? New Zealand Journal of Teachers’ Work, 15(1), 63-84. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.24135/teacherswork.v15i1.243

Rickson, D., Reynolds, D., & Legg, R. (2018). Learners’ perceptions of daily singing in a school community severely affected by earthquakes: Links to subjective wellbeing. Journal of Applied Arts and Health, 9(3), 367-384. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1386/jaah.9.3.367_1

Conference Presentations

Rickson, D., Legg, R., & Reynolds, D. (2016). Singing for Well-being in a New Zealand School. Paper presented at the 38th Conference of the Australia and New Zealand Association for Research in Music Education (ANZARME), The University of Auckland. 22-25 September 2016.

Rickson, D., Legg, R., & Reynolds, D. (2018). Singing for wellbeing: Action research with a New Zealand primary school community severely affected by earthquake. Paper presented at the British Association for Music Therapy conference, ‘Music, Diversity and Wholeness’ London. 15-18 February, 2018.

Rickson, D., Legg, R., Reynolds, D., & Atkinson, J. (2017). Teachers’ experiences of singing for wellbeing: A case study. Paper presented at the Music Therapy New Zealand Symposium: Finding your voice, Wellington, NZ. 12-13 August, 2017.

Rickson, D., Legg, R., & Reynolds, D. (2017). Singing for wellbeing in a New Zealand school severely affected by earthquakes. Paper presented at the 15th World Congress of Music Therapy: Moving forward with music therapy, inspiring the next generation, Tsukuba, Japan. July, 2017.

Rickson, D., Legg, R., & Reynolds, D. (2016). Singing for well-being: an exploration of the relationship between participation in singing programmes and learner well-being in a Christchurch primary school. Poster presented at the Victoria University of Wellington: Wellbeing Week; Music for Health & Wellbeing. May, 2016.

Other

Lecture organised by Associate Professor Hiroko Kimura, Kumamoto University, Kumamoto City, Japan, March 2018. Hauora in Schools, Monthly Features: Our published report will be linked to https://www.cph.co.nz/your-health/hauora-in-schools/hauora-in-schools-mo…

References

Averill, R. (2009). Teacher-student relationships in diverse New Zealand year 10 mathematics classrooms. In M. Clark (Ed.), Teacher Care. Wellington: Victoria University of Wellington.

Bailey, B. A., & Davidson, J. W. (2002). Adaptive characteristics of group singing: perceptions from members of a choir for homeless men. Musicae Scientiae, 6, 221–256.

Bailey, B. A., & Davidson, J. W. (2005). Effects of group singing and performance for marginalized and middle-class singers. Psychology of Music, 33, 269–303.

Beck, R. J., Cesario, T. C., Yousefi, A., & Enamoto, H. (2000). Choral singing, performance perception, and immune system changes in salivary immunoglobulin A and cortisol. Music Perception, 18, 87–106.

Bird, J. M., & Markle, R. S. (2012). Subjective well-being in school environments: Promoting positive youth development through evidence-based assessment and intervention. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 82(1), 61–66. doi:10.1111/j.19390025.2011.01127.x

Blackmore, J., Bateman, D., Loughlin, J., O’Mara, J., & Aranda, G. (2011). Research into the connections between built learning spaces and student learning outcomes: A literature review. Melbourne, VIC: State of Victoria.

Boyack, J. E. (2011). Singing a joyful song: An exploratory study of primary school music leaders in Aotearoa New Zealand. Unpublished docytoral thesis, Massey University, Palmerston North.

Boyd, S., Bonne, L., & Berg, M. (2017). Finding a balance—fostering student wellbeing, positive behaviour, and learning: Findings from the NZCER national survey of primary and intermediate schools 2016. Retrieved from http://www.nzcer.org.nz/research/publications/ finding-balance-fostering-student-wellbeing

Cardno, C. (2003). Action research: A developmental approach. Wellington: New Zealand Council for Educational Research.

Cavanagh, T. (2008). Schooling for happiness: Rethinking the aims of education. Kairaranga, 9(1), 20-23. Retrieved from http:// ezproxy.massey.ac.nz/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=eric&AN=EJ908171&site=edslive&scope=site

Cheong-Clinch, C. (2009). Music for engaging young people in education. Youth Studies Australia, 28(2), 50–57. Retrieved from <Go to ISI>://CABI:20093168880

Christenson, S. L., Reschly, A. L., & Wylie, C. (2012). Preface. In S. L. Christenson, A. L. Reschly, & C. Wylie (Eds.), Handbook of Research on Student Engagement. Boston, MA.: Springer.

Clark, I., & Harding, K. (2012). Psychosocial outcomes of active singing interventions for therapeutic purposes: a systematic review of the literature. Nordic Journal of Music Therapy, 21(1), 80–98. doi:10.1080/08098131.2010.545136

Clift, S. M., & Hancox, G. (2006). Music and wellbeing . In W. Greenstreet (Ed.), Integrating Spirituality in Health and Social Care (pp. 151–165). Oxford, UK: Radcliffe Publishing.

Clift, S. M., Hancox, G., & Morrison, I. (2010 ). Choral singing and psychological wellbeing: Quantitative and qualitative findings from English choirs in a cross-national survey. Journal of Applied Arts and Health, 1(1), 19–34.

Clift, S. M., Hancox, G., Staricoff, R., & Witmore, C. (2008). Singing and health: A systematic mapping and review of non-clinical research. Canterbury, UK: Canterbury Christ Church University.

Crooke, A. H. D., & McFerran, K. S. (2014). Recommendations for the investigation and delivery of music programs aimed at achieving psychosocial wellbeing benefits in mainstream schools. Australian Journal of Music Education, 1, 15–37.

Crooke, A. H. D., Smyth, P., & McFerran, K. (2016). The psychosocial benefits of school music: reviewing policy claims. Journal of Music Research Online, 1, 1–15.

Curry, P. (2009). Why educating learners in health and wellbeing is so important. Education and Health, 28(1), 16–17.

Denny, S. J., Grant, S., Utter, J., Robinson, E. M., Fleming, T. M., Milfont, T. L., . . . Watson, P. (2011). Health and well-being of young people who attend secondary school in Aotearoa, New Zealand: What has changed from 2001 to 2007? Journal of Paediatrics & Child Health, 47(4), 191–197. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1754.2010.01945.x

Dodge, R., Daly, A., Huyton, J., & Sanders, L. (2012). The challenge of defining wellbeing. International Journal of Wellbeing, 2(3), 222– 235.

Durie, M. (1994). Whaiora: Māori health development. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Dziubinski, J. P. (2014). Does feeling part of a learning community help students to do well in their A-levels? exploring teacher-student relationships. Research in Post-Compulsory Education, 19(4), 468–480.

Ebersohn, L. (2012). Adding ‘flock to ‘fight and flight’: A honeycomb of resilience where supply of relationships meets demand for support. Journal of Psychology in Africa, 27(2), 29–42.

Education Review Office. (2013). Stories of Resilience and Innovation in Schools and Early Childhood Services: Canterbury Earthquakes 2010–2012 Wellington: Education Review Office.

Education Review Office. (2015a). Bullying prevention and response guide: Schools’ awareness and use. Wellington: Author.

Education Review Office. (2015b). Wellbeing for children’s success at primary school. Wellington: Author.

Education Review Office. (2015c). Wellbeing for Children’s Success at Primary School. Wellington: Author.

Education Review Office. (2016a). Wellbeing for children’s success: A resource for schools. Wellington: Author.

Education Review Office. (2016b). Wellbeing for children’s success: Effective practice. Wellington: Author.

Fredrickson, B. L. (2009). Positivity: Ground breaking research reveals how to embrace the hidden strength of positive emotions, overcome negativity, and thrive. New York, NY: Crown.

Furrer, C., & Skiinner, E. (2003). Sense of relatedness as a factor in children’s academic engagement and performance. Journal of Educational Psychology, 95(1), 148–162.

Gao, T., O’Callaghan, C., Magill, L., Lin, S., Zhang, J., Zhang, J., . . . Shi, X. (2012). A music therapy educator and undergraduate students’ perceptions of their music project’s relevance for Sichuan earthquake survivors. Nordic Journal of Music Therapy, 22(2), 107–130. do i:10.1080/08098131.2012.691106

Gembris, H. (2012). Chapter 25: Music-making as a lifelong development and resource for health. In R. A. MacDonald, G. Kreutz, & L. Mitchell (Eds.), Music, health, and wellbeing. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Goodman, F. R., Disabato, D. J., Kashdan, T. B., & Kauffman, S. B. (2017). Measuring well-being: A comparison of subjective well-being and PERMA. The Journal of Positive Psychology, Published online 10 Oct 2017. doi:10.1080/17439760.2017.1388434

Grape, C., Sandgren, M., Hansson, L.-O., Ericson, M., & Theorell, T. (2003). Does singing promote well-being? An empirical study of professional and amateur singers during a singing lesson. Integrative Physiological and Behavioral Science, 38 65-74.

Heyning, L. (2011). “I can’t sing!” The concept of teacher confidencee in singing and the use within their classroom. International Journal of Education and the Arts, 12(13).

Higgins, L. (2015). My voice is important too: Non-formal music experiences and young people. In G. E. McPherson (Ed.), The Child as Musician: A handbook of musical development: Oxford, UK:Oxford Scholarship Online.

Hine, G. S., & Lavery, S. D. (2014). Action research: Informing professional practice within schools. Issues in Educational Research, 24(2), 162–173.

Hinshaw, T., Clift, S., Hulbert, S., & Camic, P. M. (2015). Group singing and young people’s psychological well-being. International Journal of Mental Health Promotion, 17(1), 46–63. doi:10.1080/14623730.2014.999454

Hinshaw, T., Clift, S. M., Hulbert, S., & Camic, P. M. (2015). Group singing and young people’s psychological well-being. International Journal of Mental Health Promotion, 17(1), 46–63. doi:10.1080/14623730.2014.999454

Hylton, J. B. (1981). Dimensionality in high school student participants’ perceptions of the meaning of choral singing experience. Journal of Research in Music Education, 29, 287–296.

Israel, B. A., Eng, E., Schulz, A. J., & Parker, E. A. (2012). Methods for Community-Based Participatory Research for Health Retrieved from http://VUW.eblib.com/patron/FullRecord.aspx?p=918182

Judd, M., & Pooley, J. A. (2014). The psychological benefits of participating in group singing for members of the general public. Psychology of Music, 42(2), 269–283.

Keyes, C. L. M. (2002). The mental health continuum: From languishing to flourishing in life. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 43(2), 207-222. doi:10.2307/3090197

Kindekens, A., Reina, V. R., Backer, F., Peeters, J., Buffel, T., & Lombaerts, K. (2014). Enhancing student wellbeing in secondary education by combining self-regulated learning and arts education. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 116, 1982–1987.

Kirsh, E., van Leer, E., Phero, H., Xie, C., & Khosla, S. (2013). Factors associated with singers’ perceptions of choral singing well-being. Journal of Voice, 27(6), 786.

Kloep, M., Hendry, L., & Saunders, D. (2009). A new perspective on human development. Conference of the International Journal of Arts and Sciences, 1(6), 332–343.

Kreutz, G., Bongard, S., Rohrmann, S., Hodapp, V., & Grebe, D. (2004). Effects of choir singing or listening on secretory immunoglobulin A, cortisol, and emotional state. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 27, 623–635.

Kuntz, J. R. C., Naswall, K., & Bockett, A. (2013). Keep calm and carry on? An investigation of teacher burnout in a post-disaster context. New Zealand Journal of Psychology, 42(2), 83–94.

Livesay, L., Morrison, I., Clift, S. M., & Camic, P. M. (2012). Benefits of choral singing for social and mental wellbeing: Qualitative findings from a cross-national survey of choir members. Journal of Public Mental Health, 11, 10–27.

Mahatmya, D., Lohman, B. J., Matjasko, J. L., & Farb, A. F. (2012). Engagement Across Developmental Periods. In S. L. Christenson, A. L. Reschly, & C. Wylie (Eds.), Handbook of Research on Student Engagement. Springer: Boston, MA.

McFerran, K. S. (2010). Adolescents, music and music therapy. London, UK: Jessica Kingley Publishing.

Mellor, L. (2013). An investigation of singing, health and well-being as a group process. British Journal of Music Education, 30(2), 177– 205.

Mertler, C. A. (2010). Action Research: Improving schools and empowering educators. Kindle Edition: SAGE Publications. Ministry of Education. (2007). The New Zealand curriculum. Wellington: Learning Media.

Ministry of Education. (2008). Te marautanga o Aotearoa. Wellington: Ministry of Education.

Ministry of Education. (2015). Why study the arts. Retrieved from http://nzcurriculum.tki.org.nz/The-New-Zealand-Curriculum/ Learning-areas/The-arts/Why-study-the-arts.

Mutch, C. (2015). Quiet heroes: Teachers and the Canterbury, New Zealand, earthquakes. Australasian Journal of Disaster and Trauma Studies, 19(2), 77–86.

Noble, T., & McGrath, H. (2016). The prosper framework for student wellbeing. The PROSPER School Pathways for Student Wellbeing. SpringerBriefs in Well-Being and Quality of Life Research. Cham: Springer.

Noble, T., & Wyatt, T. (2008). Scoping study into approaches to student wellbeing. Final report. . Canberra, ACT: Australian Catholic University and Erebus International.

Olsson, C., McGee, R., Nada-Raja, S., & Williams, S. (2013). A 32-year longitudinal study of child and adolescent pathways to well-being in adulthood. Journal of Happiness Studies, 14(3), 1069–1083.

Pascale, L. M. (2013). The power of simply singing together in the classroom. The Phenomenon of Singing, 2, 177–183.

Rickard, N. S., Bambrick, C. J., & Anneliese, G. (2012). Absence of widespread psychosocial and cognitive effects of school-based music instruction in 10-13-year-old students. International Journal of Music Education, 30(1), 57-78.

Rickson, D. J., & McFerran, K. S. (2014). Creating music cultures in the schools: A perspective from community music therapy. University Park, IL: Barcelona Publishers.

Rogers, L., Hallam, S., Creech, A., & Preti, C. (2008). Learning about what constitutes effective training from a pilot programme to improve music education in primary schools. Music Education Research, 10(4), 485–497. doi:10.1080/14613800802547748

Ryff, C. D. (1989). Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57(6), 1069–1081. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.57.6.1069

Seldon, A. (2013). Foreword. In C. Proctor & P. A. Linley (Eds.), Research, applications, and interventions for children and adolescents (pp. vii–viii). Heidelberg, Germany: Springer Dordrecht.

Seligman, M. (2011). Flourish: A new understanding of happiness,well-being-and how to achieve them: Nicholas Brealey

Sigurðardóttir, A. K., & Hjartarson, T. (2016). The idea and reality of an innovative school: From inventive design to established practice in a new school building. Improving Schools, 19(1), 62–79. doi:10.1177/1365480215612173

Swain-Campbell, N., & Quinlan, D. (2009). Children’s school, classroom, social well-being and health in New Zealand mid to low decile primary schools. New Zealand Journal of Education Studies, 44(2), 79–92.

Theorell, T., & Kreutz, G. (2012). Chapter 28: Epidemiological studies of the relationship between musical experiences and public health. In R. MacDonald, G. Kreutz, & L. Mitchell (Eds.), Music, health, and wellbeing. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Viner, R. M., Ozer, E. M., Denny, S., Marmot, M., Resnick, M., & Fatusi, A. (2012). Adolescence and the social determinants of health. The Lancet, 379(9825), 1641-1652. von Lob, G., Carmic, P., & Clift, S. M. (2010). The use of singing in a group as a response to adverse life events. International Journal of Mental Health Promotion, 12(3), 45–53. Retrieved from http://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/cbf/ijmhp

Weninger, R. L., & Holder, M. D. (2013). Extraversion and subjective well-being. International Journal of Psychology Research, 8(3), 141–172.

Research team

Dr Daphne Rickson, Victoria University of Wellington (PI) contact: daphne.rickson@vuw.ac.nz

Dianna Reynolds, Deputy Principal, Waitākiri School

Dr Robert Legg, Victoria University of Wellington

Appendix 1: The relationships between singing for well-being and Key Competencies

Appendix 2: indicators of well-being—our themes

Drawn from teachers’ journals (google docs); children’s artworks and videos; individual interviews and focus groups with teachers; individual interviews and focus groups with children; well-being surveys.

Appendix 3: Action research cycles

| Questions | Action | Where did we get to? |

| How is the singing facilitated? | Teacher focus group | We could describe how the singing developed and is facilitated.

We agreed to examine the ‘singability’ of the material that was introduced. |

| Are we using the most appropriate repertoire? | Observe, reflect, plan & act

Use google docs to document |

Some songs are easier to sing than others.

We agreed to introduce songs specifically written for children. |

| What do the learners think about singing? | Learners captioned artworks

Learner focus groups Learner interviews |

Learners are extremely positive about singing and describe a wide range of perceived benefits.

They enjoy a wide repertoire of songs. Why do teachers need to examine their facilitation of singing for wellbeing? |

| Do teachers need to know more about how to facilitate singing? | Teacher focus group | Singing for well-being is different to music education.

Teachers are not confident to teach music. |

| How/why is singing for well-being different to music education? | Teacher focus group

Learner focus group Literature review Review curriculum docs |

Singing for well-being is for fun, learner-led. Children are learning and achieving as part of this experience. Music education has targeted testable outcomes. |

| Could music education also have intrinsically benefits that link to wellbeing? | Individual teacher interviews

Literature review Review Key Competencies |

Music education activities do not automatically lead to well-being benefits. Singing was an activity that supported the well-being of our community because it met our specific needs for collective expressive activity. |

Appendix 4: Survey questions

Survey questions

- I feel I belong at school

- At school we celebrate the good things that students do

- Teachers and students care about each other

- Teachers are interested in my culture or family background

- I feel safe at school

- Everyone thinks our school values are important (like respect for others)

- Behaviours like hitting and bullying are not OK at school

- Teachers get on well with students from different cultures and backgrounds

- Teachers ask for our ideas about how students can get on better with each other

- Teachers think all students can do well

- Teachers often notice when students help each other

- Teachers make learning interesting

- Teachers care about how I feel

- At school, I am taught that it’s OK to be different from other children

- At school, I am taught how to manage my feelings (like if I get angry)

- My parents, family and whanau always feel welcome at school

- Students treat each other with respect

- Students include other children who are left out

- Students are good at listening to each other’s ideas and views

- I can say how I’m feeling when I need to