E tipu e rea mo ngā rā o tō ao.

Grow up, o tender shoot, and thrive in the days destined for you.

Introduction

Children’s early years set the stage for their future development, in education and beyond (Poulton, Gluckman, Potter, McNaughton, & Lambie, 2018). In New Zealand, and internationally, many young children spend time in the education and care of other adults (Education Counts, 2019; National Survey of Early Care and Education Project Team, 2016). Given this, early childhood education and care (ECEC) is a potentially important influence for the development of children (Education Counts, 2019; McCoy et al., 2017) and the wellbeing of society (Heckman, 2011; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine [NASEM], 2019).

Initiatives in New Zealand (Kōrero Mātauranga, 2018a) and elsewhere (National Research Council, 2015) consider how to support ECEC in its delivery of high-quality early childhood experiences to all children. The settings of ECEC are diverse, including home-based as well as centre-based ECEC. Internationally, the majority of children are served in home-based ECEC (National Survey of Early Care and Education Project Team, 2016), and home-based ECEC is growing in New Zealand (Education Counts, 2019). Despite this, less research has investigated how to support teaching and learning in home-based ECEC relative to centre-based ECEC (Kōrero Mātauranga, 2018b; Smith, 2015; Tonyan, Paulsell, & Shivers, 2017).

Home-based ECEC includes several features that hold promise for fostering high-quality early learning experiences. The adult–child ratio, for example, in which one adult serves no more than four children under age 5, has the potential to allow for high-quality learning experiences that benefit young children’s learning (Bowne, Magnuson, Schindler, Duncan, & Yoshikawa, 2017). Moreover, families may select home-based ECEC settings that fit with their home culture, language, and values (Tonyan, Paulsell et al., 2017), factors that may promote important connections between parents and educators and continuities in learning for young children (Biddulph, Biddulph, & Biddulph, 2003; McWayne, 2015, Mundt, Gregory, Melzi, & McWayne, 2015). However, home-based ECEC also presents special challenges for supporting teaching and learning, given its unique setting—typically, one adult, working alone—and diverse workforce, with varied educational backgrounds, experiences, and resources (Bromer & Korfmacher, 2017; Davis et al., 2012; Smith, 2015). Recognising the unique context of home-based ECEC, the Ministry of Education conducted a specific review of home-based ECEC in 2018, which has resulted in proposals for professional education for educators[1] and supporting professional learning and development by strengthening the role of supervising teachers (Kōrero Mātauranga, n.d.).

Quality learning experiences in early childhood involve interactions between kaiako[2] and children (Pianta, Downer, & Hamre, 2016). Professional education, like adult–child ratio or classroom size, has been described as an aspect of structural quality in ECEC (Pianta et al., 2016; Slot, Bleses, Justice, Markussen-Brown, & Højen, 2018; Smith, 2015). All of these structural features are generally associated with quality learning experiences but they are not the same thing: structural features may make it more likely that quality learning experiences happen, but the actual interactions between kaiako and children are the real heart of learning experiences in ECEC (Pianta et al., 2016; Slot et al., 2018). Therefore, when thinking about supporting teaching and learning in ECEC, it is important to think about how to support teaching and learning interactions.[3]

In New Zealand, visiting teachers (co-ordinators) oversee home-based ECEC, providing professional leadership and support to educators and supervising the ECEC services provided to children (Kōrero Mātauranga, 2018b). Individualised, in-home supports are thought to be key to supporting home-based ECEC (Bromer & Korfmacher, 2017). Therefore, New Zealand’s organisational structure in which all educators in licensed home-based services have the support of a qualified registered early childhood teacher (the visiting teacher) is a particular strength of home-based ECEC here. In contrast, for example, only about a third of regulated home-based providers in the US receive some form of coaching (Bromer & Korfmacher, 2017). Our project built on this structure by partnering university researchers and visiting teachers to investigate application of a multi-component relational approach for supporting teaching and learning in home-based ECEC.

Background to our work: Why we did what we did

In developing our model, we considered three things: (a) children’s learning and development within a particular period; (b) learning experiences that support children’s learning and development; and (c) recommendations for practice-based research to support consolidating professional learning into practice within the home-based ECEC context.[4] As we present in the next section, we drew on these recommendations to develop, trial, and begin to evaluate a multi-component relation-based approach for supporting teaching and learning in homebased ECEC in two developmentally important learning areas (children’s oral language and approaches to learning) for educators of older preschool-age children (3½ to 5 years old).

Evaluating supports for teaching and learning in home-based ECEC: What were our research questions?

We wished to learn whether our approach was helpful for home-based ECEC, guided by the following research questions:

Question 1: Participation. How many educators participated with us and what was their experience of participation?

Question 2: Benefits for educators. Did participation add to participating educators’ practice kete, and their teaching and learning interactions with their children? Were there other benefits for educators, such as developing a greater sense of being part of a professional community?

Question 3: Benefits for children. Was participation associated with positive learning experiences and outcomes for children in areas of learning focused on in this trial?

Project description and evaluation design

Project development

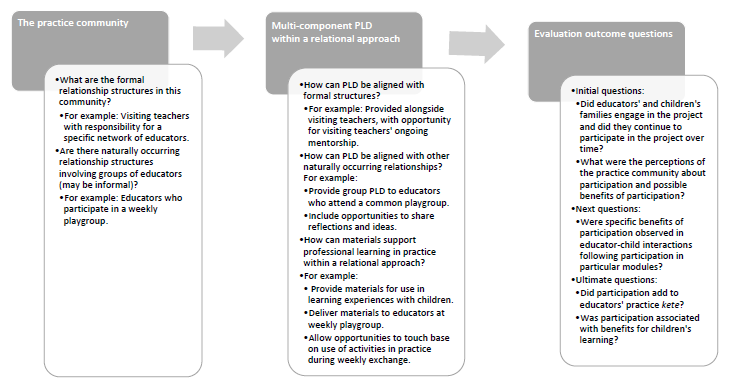

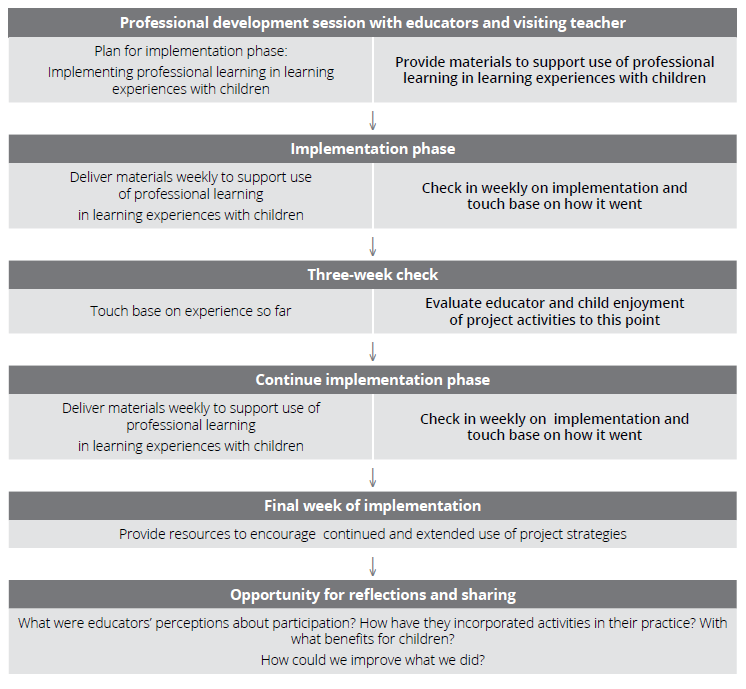

Building on recommendations for supporting teaching and learning in home-based ECEC (Bromer & Korfmacher, 2017), the general framework for our work is portrayed in Figure 1. Before determining how our project was going to be delivered and evaluated, we first needed to consider our specific home-based ECEC community and the naturally occurring relationships in our community (Atkins, Rusch, Mehta, & Lakind, 2016; Bromer & Korfmacher, 2017; Smith, 2015). This meant allowing time for necessary pre-planning—time in which university researchers and visiting teachers jointly considered how to design project activities in ways that fit with the home-based ECEC service.

FIGURE 1. Conceptual framework and guiding questions (adapted from Bromer & Kormacher, 2017).

Guiding questions describe general considerations when developing services to support teaching and learning in home-based ECEC. Examples illustrate responses to these questions in one home-based ECEC community; other communities may develop other responses when considering their specific practice communities.

The practice-based context for this project was a non-profit, non-government organisation that provides both centre-based and home-based ECEC. The home-based visiting teacher team consists of four visiting teachers who oversee three networks of home-based educators, mentor new educators into the organisation and profession, and support their professional development efforts. The organisation also provides for various group-based activities that home-based educators may choose to attend with their children. In particular, educators and their children often attend a weekly playgroup with others in their networks, with visiting teachers regularly calling in on their respective playgroups. Although some educators don’t attend playgroup or choose to attend one of the other playgroups, this presented a naturally occurring social structure of visiting teachers and playgroups on which to build our project (see Evaluation design, below).

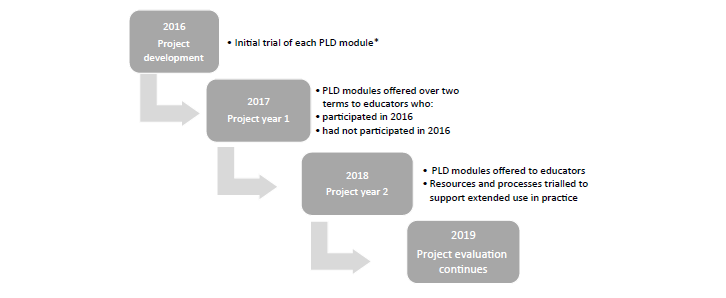

Collaborative project planning provided the opportunity for whakawhanaungatanga[5] between visiting teachers and university researchers, setting the stage for our developing research partnership. Some of the university researchers had engaged with the broader early childhood organisation in previous research. Yet the present project was their first research experience in home-based ECEC, and this was the first collaborative venture for our combined team. Figure 2 illustrates the timeline for our project. This 2-year Teaching and Learning Research Initiative (TLRI) project took place during 2017–18; however, as shown in Figure 2, planning for this project was underway by 2016, in response to requests from the early childhood organisation to consider developing our previous work for parents of preschool-age children into professional development for home-based ECEC (Schaughency, Riordan, Das, Carroll, & Reese, 2016).

FIGURE 2. Project timeline

The funding period for the TLRI was 2017–18. The 2016 pilot was supported by a grant from Westpac. Evaluation data were collected throughout 2016–18, with collation and analysis of evaluation data ongoing.

Project description

We developed three professional learning modules to support teaching and learning in home-based ECEC. Each module focused on a specific area of learning, identified from research on young children’s development and early years teaching, and provided examples of learning experiences to foster development in that area of learning. Although modules focused on different areas of learning, they were delivered using a common format as described below (see also Figure 1) and based on the educational principles of sensitively encouraging and scaffolding children’s active participation as learners in positive learning experiences. In this project, we wanted to provide educators with the opportunity to participate in all three learning modules for two reasons. First, each area of learning has its own developmental pathway (National Research Council, 2015), and our previous experience providing parent education to foster learning experiences to support young children’s development in these learning areas (see, for example, Healey & Healey, 2019; Schaughency, 2017) suggested each module potentially provided separate, but complementary, benefits for children’s learning and development (National Research Council, 2015). Second, because sustained involvement in professional learning is associated with enhanced learning experiences for children (Markussen-Brown et al., 2017), we wanted to provide educators with the opportunity to engage in professional learning over time.

Module delivery. The general sequence of project activities for each professional learning module is depicted in Figure 3. Each module began with a professional development session. The professional development session was followed by a 6-week period (called the implementation phase) that focused on providing learning experiences to children in the learning area.

FIGURE 3. Sequence of activities for each professional learning module

Each professional learning module began with a professional development session, followed by 6 weeks in which educators were provided with materials to support use of professional learning in learning experiences with children.

Professional development session. This session provided a rationale for the module’s focus—that is, an introduction to, and importance of, the learning area and links to the strands of Te Whāriki and key competencies in the New Zealand curriculum (Te Kete Ipurangi, 2014)—and strategies for scaffolding learning experiences in the learning area and materials to use with children. We encouraged educators to use materials in ways that were responsive to their children and that fit with their practice. The session closed with a plan for kicking off the implementation phase.

Implementation phase. We included an implementation phase for reasons related to our dual aims of supporting teaching and learning in home-based ECEC. Opportunities to practise developing skills are crucial for adults’ (Salas, Tannenbaum, Kraiger, & Smith-Jentsch, 2012) as well as children’s learning (see, for example, Justice, Jiang, & Strasser, 2018). Therefore, we included several features in this phase to support, and reduce barriers to, using skills in practice.

Visiting teachers attended and contributed to professional development sessions with educators. Building on this shared experience, visiting teachers could then incorporate observations of, and discussions about, educators’ use of project learning experiences and children’s learning in regular mentoring and supervision with participating educators.

We provided resources to support use of professional learning in learning experiences with children for each module to ensure that lack of access to resources was not a barrier to implementation (Graczyk, Domitrovich, Small, & Zins, 2006). Resources were designed so that they could be picked up and used with children, to reduce lack of confidence as a potential barrier to use. To support visiting teachers in mentoring educators, we also provided visiting teachers with relevant materials for each module.

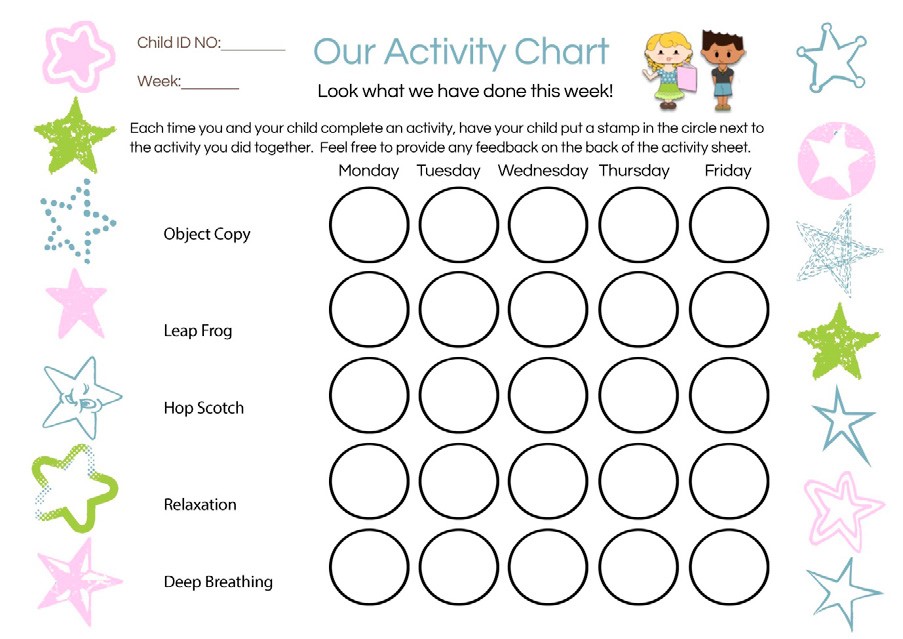

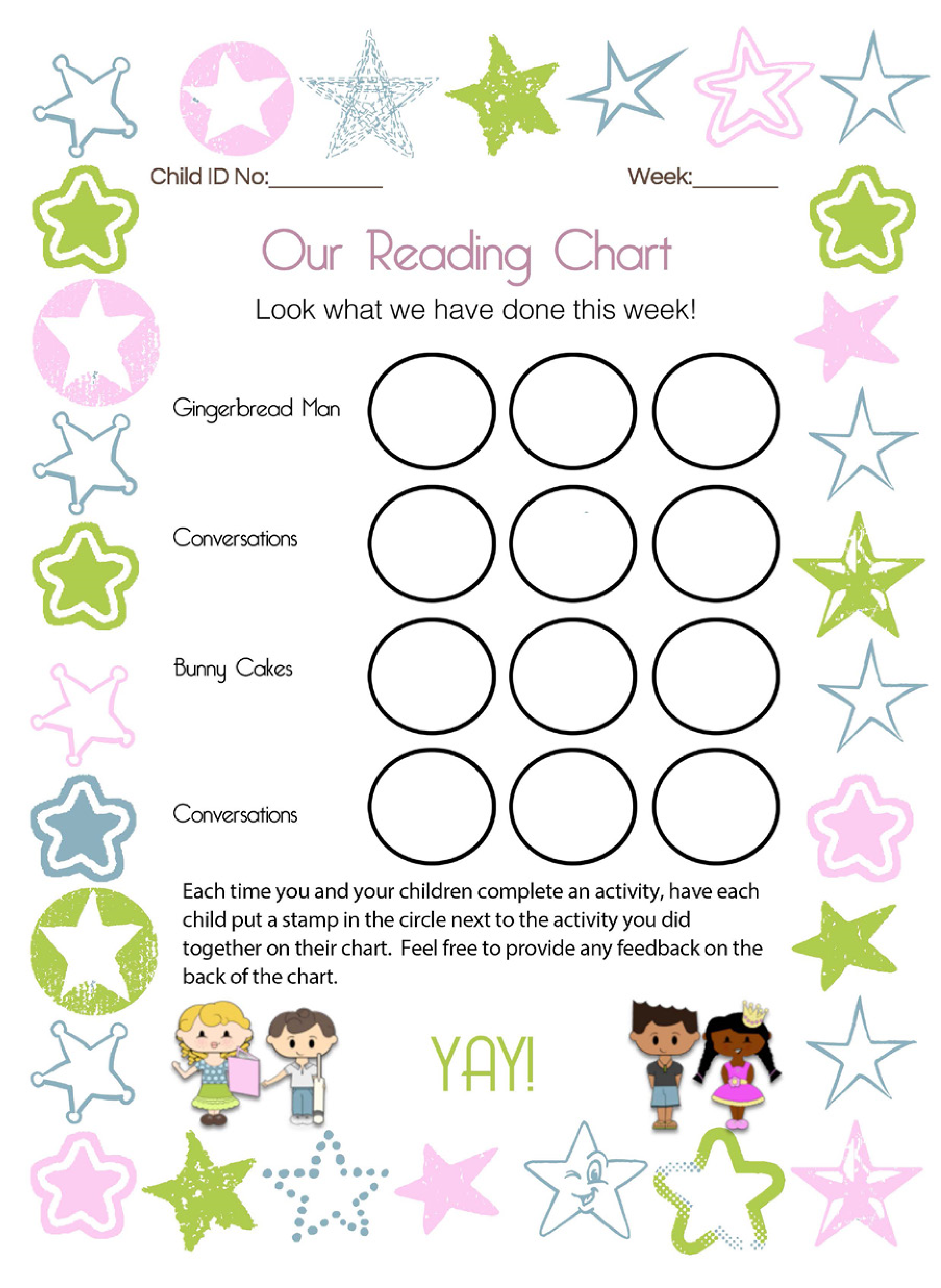

New materials were provided to educators as arranged at the professional development evening (e.g., at educators’ weekly playgroup; see Figure 3 and Evaluation design, below). This regular material exchange potentially facilitated educators’ implementation of project learning experiences in several ways. Participating children were excited about the delivery of new materials to their educators, and they asked adults to use materials with them (e.g., read them a book). We also gave educators weekly activity charts (see The professional learning modules and Evaluation methods, below), to be completed and returned along with any loaned materials from the previous week. Young children enjoy filling in stamp charts that document completion of activities (Schaughency et al., 2014), and we asked educators to have participating children place a stamp on their weekly chart each time they completed a project activity. This simple procedure may have also facilitated implementation: children’s enjoyment of this process may have further engaged educators. Some educators included copies of implementation charts in children’s portfolios to share children’s project-related experiences with their families, further reinforcing educators’ efforts to provide project learning experiences. Finally, we invited educators to provide comments on their experience on the back of the chart, and during material exchanges project team members briefly touched base with educators on their experience with the previous week’s activities, with activity charts serving as a tool for informal reflection and formative review.

We planned a 6-week implementation phase for two reasons. This time frame can yield benefits for learning experiences provided to young children and their development (Healey & Halperin, 2015; Mol, Bus, de Jong, & Smeets, 2008; Schaughency, 2017). This time frame also fits within a school term, relevant to many families’ routines. Educators’ weekly activity charts conveyed children’s varied schedules—some children attending home-based ECEC a few days each week, others every day. When children attended part time, we followed educators’ preferences for timing of materials’ exchanges. Some educators chose weekly exchanges, saying they felt this was a good pace for project activities; others shifted to fortnightly exchanges to provide more opportunities for project-related learning experiences for their children.

Providing opportunities for discussions and reflections about professional learning and its use on the job is another simple process that contributes to consolidation of professional learning in practice (Salas et al., 2012). In addition to regular, ongoing mentorship by visiting teachers and informally touching base when delivering new materials, we included two other opportunities for connecting with educators about their experience of participation, half-way through the implementation phase (the 3-week check) and following completion of each module (after participation reflections; see Figure 3). Although these procedures were included as part of our evaluation methods (see below), they may have also supported implementation.

The professional learning modules. Modules focused on specific areas of learning identified as important for developing competencies in the preschool years (Ministry of Education, 2017; National Research Council, 2015). Each module was originally developed and found to show promise with parents of preschool children (Healey & Halperin, 2015; Healey & Healey, 2019; Schaughency, 2017; Schaughency et al., 2014) but adapted for use in home-based ECEC. We piloted these adapted modules with educators in 2016, with educators participating in one of the three modules. In this project, we offered educators the opportunity to participate in all three modules, although, as we describe below, our design entailed educators participating in the modules in different orders (see Evaluation design).

Enhancing Neurobehavioural Gains through the Aid of Games and Exercise (ENGAGE; Healey & Halperin, 2015). Early years learning includes developing skills important to children’s wellbeing and success as learners (National Research Council, 2015; Poulton et al., 2018; Thompson, 2016). These learning-related skills are multifaceted and involve developing competencies connected to thinking (focusing attention; holding onto information), emotions (handling feelings), and behaviour (containing impulses; doing things carefully). In ENGAGE, adults provide intentional play-based learning experiences as opportunities for children to practise and adults to responsively scaffold these important skills.

As adapted for this project, each week for 5 weeks educators were given five cards, each suggesting an activity that provided learning experiences in one or more of these areas. To illustrate, Table 1 depicts activities used in the first week of ENGAGE in this project. Suggested learning experiences were common early childhood activities involving active (e.g., hopscotch) and quiet (e.g., making things with blocks) play that use these learningrelated competencies. Necessary materials for suggested activities are often available in homes and early childhood settings, although we provided some new play materials each week along with activity cards. For example, in the first week we provided soft blocks that could be used to make patterns and chalk that could be used to draw a hopscotch area on a footpath or patio.

TABLE 1. Week 1 ENGAGE activities offer opportunities to practise learning-related skills involving thinking, feeling, and doing

New activities suggested each week offer other opportunities to practise skills in each of these areas to support developing competencies important for successful approaches to learning.

| Activity | Description | Supports skills linked to: | ||

| Thinking | Feeling | Doing | ||

| Object copy | Educators and children use blocks to recreate and create patterns. | Children learn about patterns and to attend and remember them. | ||

| Relaxation | Educators guide children through a series of exercises that help children tense and relax muscles (e.g., marching around stiff and upright like a soldier; lying down quietly like a sleeping cat). | Children learn about different ways their bodies feel and that they can do things that make them feel differently, important foundations for confidently handling feelings. | ||

| Deep breathing | Educators help children learn how to practise deep breathing using imagery (e.g., breathing in through their nose to fill up their tummy like a balloon; breathing out slowly like they were blowing a big bubble). | Children learn to use deep breathing, which is another skill children can use to feel more calm and relaxed. | ||

| Leap frog | Traditional leap frog or adapted using pillows. | Children learn to jump with care and be calm and still as a rock. | ||

| Hopscotch | Traditional game that can be adapted and extended | Children develop skills involved in jumping, hopping, and balancing. | ||

Each week, educators were asked to introduce suggested activities and try to provide opportunities to do them daily (see Appendix A, Our activity chart). Educators were urged to use activities in ways that fit with their settings and routines and sensitively and responsively met the developmental needs of their children so they were positive, successful learning experiences for all children, which scaffolded and extended their learning over time. Accordingly, activities could be done at any time of day or place, and, depending on children’s developing skills, they could be made easier or more difficult (a simpler or more difficult hopscotch area, stepping or jumping with two feet or hopping on one foot; a simple pattern involving two blocks or more sophisticated pattern with multiple blocks).

After 5 weeks, educators had a set of cards suggesting 25 activities. In week 6, educators were asked to have their children choose activities from those previously learned.

Fostering oral language skills through language-rich interactions (Schaughency et al., 2014). Rich experiences with oral language are also important to early years learning (Education Review Office, 2017; National Research Council, 2015; Zauche, Thul, Mahoney, & Stapel-Wax, 2016). Children’s oral language development, like their learning-related skills, is multifaceted (Schaughency & Reese, 2010). Broadly speaking, oral language development includes the skill sets involved in understanding and expressing ideas (meaningrelated skills) and those involved in being tuned into and using the sounds of spoken language (sound-related skills). Adults can support children’s language development during a variety of everyday interactions with children, when sharing stories (Riordan, Reese, Rouse, & Schaughency, 2018), conversations (Reese, Leyva, Sparks, & Grolnick, 2010), or engaging in wordplay (Reese, Robertson, Divers, & Schaughency, 2015). However, research suggests these potential teaching and learning opportunities may not always be used to their fullest (Hindman, Wasik, & Bradley, 2019; Justice et al., 2018).

To support adults in fostering children’s language development in these contexts, Schaughency et al. (2014) developed two modules—one focused on meaning-related skills and the other on sound-related skills, that used a similar format to incorporate oral language interactions during and outside of shared reading. The professional development sessions for these modules introduced strategies for encouraging children’s active involvement in these interactions and scaffolding their participation and learning. During the implementation phase, both modules lent educators two books per week to read with their children each week for 6 weeks. Books were all published children’s books containing a story consisting of characters with a problem to be solved, and were a mix of old and new stories, by New Zealand and international authors, that did and did not include sound-related features such as rhyme and alliteration. The books lent to educators included specific resources to support project-related learning experiences as described below. Since these books were only loaned to educators, we also gave educators copies of their two favourite books (identified at the 3-week check and after module reflections) from each of the oral language modules.

Because children often like to hear the same story again, and re-reading affords opportunities to deepen their learning (Aram, Fine, & Ziv, 2013; Flack, Field, & Horst, 2018), educators were asked to try to read each book three times over the course of the week. Simply asking adults to re-read stories may not be sufficient to encourage scaffolding more developmentally sophisticated skills (Aram et al., 2013). Therefore, educators were provided with resources to support their use of repeated readings to extend learning. In addition, educators were provided with suggestions for expanding learning experiences to interactions outside of reading for each reading of the story, an approach that can increase benefits from shared reading (Toub et al., 2018). As with ENGAGE, educators were urged to do shared reading and other oral language experiences at times and in ways that were responsive to their children and that fit their settings. For example, although oral language activities that built on learning experiences during shared reading were suggested, educators were told these interactions could happen anywhere and at any time (e.g., in the car, or on a walk), not necessarily in the same sitting as the story.

Rich Reading and Reminiscing (RRR). RRR focused on learning experiences that fostered children’s language skills involved in understanding and expressing ideas. These meaning-related skills include, but are not limited to, vocabulary; that is, knowing words and their meanings (Reese, Suggate, Long, & Schaughency, 2010; Schaughency, Suggate, & Reese, 2017). To foster meaning-related skills during shared reading, each book contained prompts for conversational comments during story reading. To scaffold more developmentally sophisticated conversations across readings, comments progressed from those likely to be more familiar to educators and children in the first reading (talking about story content and pictures), with relatively few questions posed to children (three questions out of 10 comments), to relatively more questions to encourage children’s involvement as active conversational partners (seven questions out of 10 comments), and more sophisticated questions, to extend children’s learning, in later readings (see Reese & Cox, 1999; Table 2).

TABLE 2. Rich Reading and Reminiscing scaffolds oral language skills related to understanding and expressing ideas through repeated interactive reading.

In addition to supporting interactive shared reading, Rich Reading and Reminiscing also encourages educators to have conversations with children outside of reading linking story themes to children’s experiences.

| Across repeated readings, educators … | |||

| Ask more questions over time active contributors; for example: | Make comments that extend to invite children to become children’s learning over time |

Examples | |

| First reading | Ask three questions out of 10 comments | Make comments to help children become familiar with the story |

|

| Second reading | Ask five questions out of 10 comments. | Make comments and ask simple questions building on ideas introduced in previous reading. |

|

| Third reading | Ask seven questions out of 10 comments | Include sophisticated comments and questions, involving:

|

|

Engaging children in conversations about their personal experiences can be an effective strategy for fostering children’s language development (Reese, Leyva et al., 2010).To foster meaning-related language skills outside of reading, at the end of the story prompts were included for each reading that suggested types of conversations educators could have with children linking children’s experiences to story content (see Appendix B, Our reading chart). At the end of the first reading, prompts suggested conversations about a positive experience that children have had with educators that related to the story in some way; at the end of the second, a time when children experienced something “not-so-nice” related to the book, such as experiencing a similar emotion or challenge as the story character and how they resolved it, and, following the third, another positive experience that related to the book. Although educators and children may more readily discuss positive experiences than negative ones, talking about negative experiences as well as positive ones may contribute to children’s developing socio-emotional learning and wellbeing (Salmon & Reese, 2016).

Strengthening Sensitivity to Sound (SSS). Children’s understanding that spoken language is made up of sounds (phonological awareness) develops during the early years and sets the stage for reading acquisition in school (National Research Council, 2015). SSS focused on helping children tune into sounds within words through repeated interactive shared reading and wordplay. Prompts encouraged educators to use features such as repetition, rhyme, and alliteration in children’s stories as vehicles for scaffolding children’s developing phonological awareness. Children often become aware of bigger units of language sounds (that is, words or large chunks of words; for example, being aware that compound words are made up of the smaller words or that some words rhyme) before tuning into individual sounds of words (Anthony & Francis, 2005). Prompts for the first reading, therefore, focused on earlier developing large phonological units featured in stories (such as repeating words, compound words, or rhyme), scaffolding to individual sounds across successive readings. Table 3 provides an example of this approach for a classic children’s story that includes rhyme and alliteration (words beginning with the same sound), The Gingerbread Man.

TABLE 3. Strengthening Sound Sensitivity helps children tune into language sounds through interactive repeated reading emphasising sound features in books

In addition to supporting interactive shared reading, Strengthening Sound Sensitivity also encourages educators to extend learning about language sounds outside of reading through wordplay and other activities (e.g., children’s songs) that link to story themes.

| Across repeated readings, educators… | |||

| Encourage children’s language sounds over time | Help children develop active involvement over more awareness of time |

Examples | |

| First reading | Provide 3 opportunities for children’s active participation | Emphasise story features such as repetition or rhyme to draw children’s attention to sounds in words; playfully encourage children to join in on repeating words they can anticipate | …“I’ll run and run as fast as I can. You can’t catch me, I’m the Gingerbread Man.”… …“I’ll run and run as fast as I can. You can’t catch me, I’m the Gingerbread _______” |

| Second reading | Provide 5 opportunities for children’s active participation |

Build on experiences from the first story to introduce individual sounds, such as emphasising the first sound of rhyming words and pausing after first sounds of repeating rhyming words to playfully encourage children to join in | …“I’ll run and run as fast as I can. You can’t catch me, I’m the Gingerbread Man.”… …“I’ll run and run as fast as I can. You can’t catch me, I’m the Gingerbread M….” |

| Third reading | Provide 7 opportunities for children’s active participation |

Build on the learning experiences in the second reading, for example, by drawing attention to words beginning with the first sound. | …“I’ll run and run as fast as I can. You can’t catch me, I’m the Gingerbread Man.”… …“I’ll run and run as fast as I can. You c… c… me, I’m the Gingerbread M….” |

In SSS, prompts at the end of books suggested wordplay activities that built on phonological concepts introduced during each reading (Appendix C). Children’s developing phonological skills may also be supported through nursery rhymes (Dunst, Meter, & Hamby, 2011) or other incidental playful teaching parent–child interactions (Reese et al., 2015), and prompts suggested variations on games and songs as well as other ideas for sound play that related to story themes in daily life, such as outings or around the house.

Evaluation design

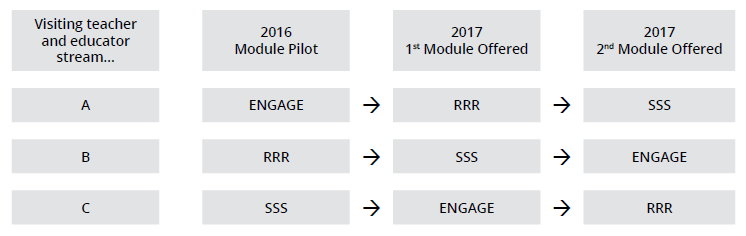

Our design was informed by recommendations for practice-based research (Kratochwill et al., 2012). It is important to consider relationships when planning supports for home-based ECEC (Bromer & Korfmacher, 2017; Smith, 2015); therefore, to the extent possible, educators participated with visiting teachers and other educators (e.g., those attending a common playgroup) in naturally occurring groups. Relationships between researchers and practitioners are also important (Schaughency et al., 2016), and university researchers partnered with specific visiting teachers and participating educator groups during the course of the project. To evaluate the project, the three modules were offered to these visiting teacher and educator groups in differing orders. Although orders were randomly determined and assigned to streams as recommended (see Kratochwill & Levin, 2014), the orders selected allowed different modules to be delivered across the project, as illustrated in Figure 4.

FIGURE 4. Evaluation design

Educators participated with visiting teachers and other educators (referred to here as streams). As illustrated in the figure, educators who began participation with our pilot in 2016 were provided the opportunity to participate in all of the modules, but participated in different orders. Educators who joined the project in 2017 joined one of the above streams and were provided the opportunity to participate in remaining modules in 2018.

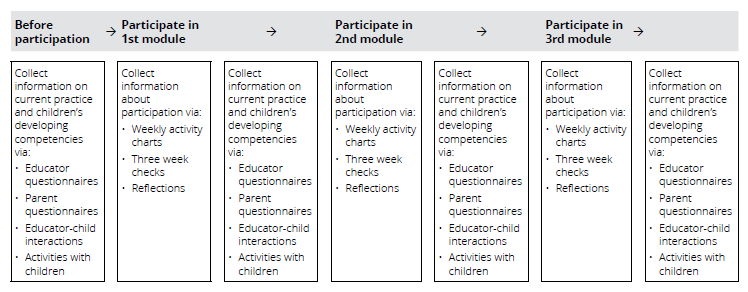

Evaluation methods

A variety of information sources speak to our research questions. Potential methods and measures were reviewed by the combined team prior to use. Methods included asking participants’ perspectives on participation and benefits for practice via questionnaires as well as face-to-face conversations, reflections, and other methods described above. Visiting teachers reviewed learning stories prepared by educators in the context of ongoing supervision. To further understand benefits for teaching and learning, we video-recorded teaching and learning interactions (shared book reading and conversations). To assess benefits for children’s learning, we collected educators’ and parents’ ratings of children’s developing oral language and learningrelated skills and conducted tasks using these skills with children over the course of the project and we are following children after their first year of primary school (this follow-up collection began in 2018 and is ongoing).

Activities involving children (educator–child interactions and child activities) were done in educators’ homes, by arrangement with educators. To enhance objectivity in assessment, child activities were carried out by research students who were uninformed of the module that educators had participated in. However, acknowledging relationship considerations in research, these students were introduced to educators and children prior to the initial assessment (e.g., at playgroup), and, when possible, the same student carried out activities with children over time.

Because limited research has studied what quality looks like in home-based ECEC (Tonyan, Paulsell et al., 2017), we needed to collect information on what educators were already doing to evaluate whether our approach to professional development added to their professional kete. Similarly, to assess the separate and combined benefits of each module, we needed to collect this information after participation in each module. This datacollection timeline is depicted in Figure 5. To acknowledge participants’ contributions to these data-collection activities, educators and parents were given book vouchers and children were given small stationery items as thank you gifts at each wave of data collection.

FIGURE 5. Evaluation methods and timeline across participation

To further evaluate benefits for learning, children are also followed after they have been in primary school for one year (this data collection is ongoing).

Approach to analyses

The above methods yield rich information for better understanding the home-based ECEC context and evaluating our work. For example, each educator–child shared book reading interaction and oral language conversation is transcribed and coded for analysis using specialised software to capture oral language and other aspects of adult–child interactions. Before moving to later evaluation questions such as benefits of participation for children’s learning (see Figure 1), our analysis first considers description of interactions in home-based ECEC before participation, given the limited research in this area (Tonyan, Paulsell et al., 2017) and what participation in our project looked like (who participated with us and how it went; Bromer & Korfmacher, 2017).

Key findings from this project

Who participated with us?

We used a two-stage procedure to invite participation. Visiting teachers, who had relationships with educators, provided project information and consent materials to educators of 3½- to 5-year-old children. To begin the process of whakawhanaungatanga between university researchers and educators, university researchers attended playgroups for the stream with which they would be engaging along with visiting teachers. This visit provided opportunities for introductions, sharing information about the project, and answering questions from prospective participating educators. After an educator provided consent for participation, information and consent materials were provided to parents/guardians of 3½- to 5-year-old children in the educator’s ECEC. When parents provided consent for their child’s participation, information about the project was provided to the educator to share with parents of other children in the educators’ ECEC.

Twenty-five educators participated with more than 55 children in one or more modules over the course of the project. Because educators typically provided education and care for more children than those who directly participated, additional children indirectly participated alongside participating educators and children, and educators continue to share project-related learning experiences with new children.

There were a few educators who did not choose to participate. There were also two educators who indicated a desire to participate, but whose children’s parents did not provide consent for their children’s participation, and, as a result, did not participate. Educators who participated with us provided information about themselves on a questionnaire at the start of the project. Their responses suggested they were women with a range of educational backgrounds, qualifications, and years of experience working in home-based ECEC. Twenty-two identified as NZ European, two as Māori, and one as European; all reported speaking English, with one also endorsing te reo Māori at the start of the project.

Parents provided information about their children. Approximately half of participating children were identified as boys (51%; girls 49%). The majority (87%; n = 48) were identified as NZ European, with five (9%) identified as NZ Māori, four (7%) identified as of Pacific Island heritage, four (7%) of Asian descent, and two (2%) other European or American. All participating children were reported to speak English, with five children identified to speak additional languages (two te reo Māori; three Asian languages; and one some Samoan).

In general, once educators started participating with us, they continued to participate, as long as they had children in the target age range. Most participating educators (n = 18; 72%) took part in all three modules, with the remainder participating in one or two modules (see Table 4). For children, the pattern of participation was more varied. In all cases, the reason children discontinued participation was that they were shifting out of home-based ECEC. This was mostly because children were turning 5, and transitioning to primary school, although, on a couple of occasions, this was due to children changing ECEC arrangements (e.g., shifting to centre-based ECEC).

TABLE 4. Educators’ and children’s participation in three learning modules

Participating children refers to children in the identified age range who participated with their educator during implementation and engaged in evaluation activities, with parental permission. These children may have informally participated with their educators in other modules when they were younger, along with other children in their educators’ ECEC. The main reason for discontinuing participation was children transitioning out of home-based ECEC, typically to primary school learning environments.

| How many participants … | participated in all three modules? n (%) |

participated in two modules? n (%) |

participated in one module? n (%) |

| Educators (N = 25) | 18 (72%) | 2 (8%) | 5 (20%) |

| Children (N = 55*) | 12 (22%) | 19 (35%) | 24 (44%) |

What were stakeholders’ perceptions of participation?

Conversations during participation between educators, visiting teachers, and university researchers, educators’ comments and enjoyment ratings on the 3-week check, and educators’ questionnaires and reflections after participation converged to suggest that, overall, participation was viewed as a positive experience for participating educators and children. For example, when asked to rate how much they were enjoying participating on a 10-point scale, most educators rated their enjoyment of participating in each module highly during (means > 7.97) and after participation (means > 8.45), with similar results for their children during (means > 7.93) and after participation (means > 8.23) (see Table 5). Moreover, when educators and children participated in more than one module, enjoyment ratings tended to remain high across modules over time, with educators’ ratings of children’s enjoyment increasing from participation in the first (M = 8.13; SD = 1.85) to second (M = 8.79, SD = 1.24) module, irrespective of module order, t(28) = –2.29, p = .03.

TABLE 5. Ratings of how much educators and children enjoyed participating in each module

During and after participating in each module, educators rated how much they enjoyed participating and how much they thought their children enjoyed participating in activities with them. Ratings were made on a scale from 0 = really did not enjoy to 10 enjoyed very much. During participation, ratings were collected at the brief interview half-way through each module (3-week check); after participation, ratings were collected on questionnaires completed by educators. Overall, 25 educators and 55 children participated in one or more modules, with participant numbers varying across conditions.

| ENGAGE | Rich Reading and Reminiscing |

Strengthening Sound Sensitivity |

||||

| Perceived enjoyment by … |

During M (SD) |

After M (SD) |

During M (SD) |

After M (SD) |

During M (SD) |

After M (SD) |

| Educators | 9.00 (1.18) | 8.45 (1.43) | 9.39 (0.76) | 9.56 (0.70) | 7.76 (1.80) | 8.78 (1.99) |

| Children | 7.93 (1.81) | 8.23 (1.92) | 9.07 (1.15) | 8.60 (1.63) | 8.37 (1.66) | 8.63 (1.56) |

Ongoing conversations and the review at the 3-week check provided important opportunities to address educators’ questions or challenges with project activities (if any) early in the implementation phase. Discussions when collecting these data illuminated the interplay between children’s temperament and interests and their engagement in learning experiences. Educators described and rated many children’s engagement and enjoyment very highly (e.g., ratings of 10/10), whereas, for other children, for example, children educators described as more hesitant to try things that were new or they didn’t perceive they could readily do well, required a bit more thoughtful adaptation by educators to successfully engage in project-related learning experiences. In these instances, educators still tended to rate children’s enjoyment positively (only one rating < 5.00), and importantly, as elaborated below, used their knowledge of their children to adapt activities and provide positive learning experiences for them. To some extent, educators’ enjoyment ratings seemed to be linked with their enjoyment ratings for their children—when children’s enjoyment ratings were high, educators’ enjoyment ratings appeared to be high as well. Moreover, as children experienced success, educators expressed satisfaction in observing their children’s development over time.

| Each time we did the games I could see improvement in all the children. From doing Hop Scotch with two feet together and by the end of the week hopping on one foot. It was great to hear Jan at gym and mention that the children were very good at hopping—we had been practising this when we played Hop Scotch.

–Excerpt from an ENGAGE Learning Story |

| It’s so rewarding for me as a teacher doing this research with [Child’s name]. She loves reading stories, her attention span to stay focused is awesome and has amazing language skills and readily able to articulate exactly what she wants to say while adding to her vocabulary on a daily basis. Kapai!

–Excerpt from RRR Learning Story |

| Rhyming—[Child’s name] had trouble at the start so was awesome watching them develop. Kids really enjoyed finding words which rhymed.

–Excerpt from SSS Educator Questionnaire |

To gain further insight into educators’ perceptions of their experiences, after each module, we asked educators to nominate specific practices they enjoyed doing—or did not enjoy doing—with their children, and provide qualitative comments about their experiences. These results are discussed in the following sections.

Did participation provide benefits for educators and their practice?

In addition to stakeholders’ perspectives, video-recordings of educator–child interactions also provided information about benefits of participation. By collecting information before and after participation, we can examine changes associated with participation. However, given limited research in home-based ECEC (Tonyan, Paulsell et al., 2017), it was important to first describe what educators were already doing before participation, to better understand practice in home-based ECEC and inform our evaluation.

Educator–child interactions. Led by PhD student Sarah [Rouse] Timperley, analyses of observations of educators’ reading with their children before participation highlighted that educators take advantage of naturally occurring opportunities provided by different books, such as engaging in more conversations with children about their personal experiences when reading a story set in New Zealand and featuring New Zealand birds as characters (Rouse, McDonald, Reese, & Schaughency, 2017). Coding and analyses of the remaining 63 transcripts of shared reading interactions obtained across the study are still underway, but analyses comparing educator–child interactions before and after participation in their first module illustrate the rich information about learning experiences provided by these observations. After participating in the module that specifically aimed to promote oral language-enhancing interactions during shared reading (RRR), educators made more conversational overtures with children during shared reading (Timperley, Schaughency, Crawford et al., 2019). These findings for RRR are promising, especially considering that not all oral language professional development initiatives for early childhood educators are found to result in benefits for practice (see, for example, Markussen-Brown et al., 2017). This software, however, does not measure other aspects of interactions, such as talk about emotions and sounds that are important for assessing benefits of RRR and SSS (see, for example, Timperley, Schaughency, Riordan et al., 2019). Future analyses will incorporate coding designed to capture the complementary benefits of these two oral language approaches.

Educator–child interactions outside of shared reading are also associated with children’s oral language development (Goble & Pianta, 2017; Justice et al., 2018; King & La Paro, 2015). Therefore, we also videorecorded educators engaged in conversations with their children. Coding of these conversations was led by PhD student Amanda Clifford. As she transcribed interactions collected before participation, Amanda realised that we should adapt our coding to capture these educator–child interactions (Clifford, 2017; Clifford, Schaughency, Dovenberg, & Reese, 2017). For example, Amanda observed that, at baseline, educators talked with children about their experiences with their whānau. Such talk may foster greater connections between home and ECE as well as benefit children’s language learning and development (Reese & Brown, 2000; Veneziano & Nicolopoulou, 2019). Therefore, Amanda wanted to capture this potentially important talk. Analyses of these educator–child interactions are currently underway (Clifford, Schaughency, & Reese, 2019). The inset below provides an example of a Learning Story prepared by an educator participating in RRR that illustrates both the linking of story content in a New Zealand book to children’s experiences (Rouse et al., 2017) and conversations about family experiences (Clifford et al., 2019). Future analyses will explore benefits of project participation for educator–child conversations outside of shared book reading.

| “Emily the Kiwi”—During the story [Child’s name] told me that kiwis come out at night because they are nocturnal. During our conversation [she] told me that she saw a tui while she was on a nature walk with her dad and that while she was at the zoo in Chch [sic: Christchurch] she went into the dark kiwi house but couldn’t see one. We also talked about how we have seen lots of fantails on our outings at Ross Creek and that sparked a memory about how one flew into our house one day while we were reading stories.

–Excerpt from an RRR Learning Story |

Stakeholders’ perspectives. Conversations with educators during participation suggested ways that project activities and materials supported educators’ scaffolding of learning experiences for their children. Educators described a process in which trying out project materials with children prompted them to notice how children responded to these project-related learning experiences. These observations, in turn, led educators to adapt activities or incorporate strategies to effectively engage and scaffold learning experiences for their children. For example, educators with several participating children sometimes observed that one child readily responded to questions, whereas another child infrequently did. In these cases, educators described how they incorporated strategies such as intentionally directing questions to individual children to provide opportunities for all children to be actively engaged. On occasion, educators described fine-tuning of scaffolding to take a few weeks with particular children, but in such instances educators also spoke of observing when things “clicked” and described children’s growth and development as learners. Importantly, implementation took place in the context of ongoing mentorship and supervision by visiting teachers: visiting teachers encouraged educators’ reflections on children’s responses to learning experiences and supported educators in their efforts to responsively scaffold positive learning experiences for their children.

Visiting teachers commented they felt that their practice also benefited from involvement in the project. During the project, they incorporated project-related professional learning and development into internal evaluation processes, with perceived benefits for their use of the cycle of inquiry in their quality improvement activities. In turn, they described benefits for their supervision and mentoring of educators, as they engaged in deeper conversations with educators about scaffolding children’s learning during implementation.

After participation, both educators and visiting teachers described perceived benefits for practice and reported continued use of project-related strategies in practice. Educators’ ratings, shown in Table 6, suggested they perceived learning new information and developing new skills in each of the modules. Moreover, nearly all participating educators indicated that they planned to continue to incorporate strategies from each of the modules in their practice. Finally, educators who participated with us shared examples of learning opportunities they later provided that integrated across modules and extended into new areas of learning (incorporating te reo Māori). These educators reflected they were now putting thought into planning intentional learning experiences for their children—a process, they felt had benefited their practice. The inset below contains examples of continued use of strategies from each module.

| We do all of the above [ENGAGE learning areas] and incorporate into our everyday activities.

ENGAGE |

| We use all these techniques while reading any book now. I have found that the boys initiate this.

RRR |

| We use the playing with [language sounds] everywhere, in books, excursions, songs, silly ditties.

SSS |

Visiting teachers observed educators who participated in the oral language modules thoughtfully and intentionally selecting books to share with their children, whether borrowed from the library or added to their home libraries. Although we did not specifically address book selection in our modules, modules provided educators experience with a variety of books and learning experiences potentially provided by books. Moreover, visiting teachers noticed educators engaging with children in ways that encourage children’s involvement as active conversational partners.

TABLE 6. Educators’ evaluation of participation in each professional development module

Overall, 25 educators participated in one or more modules, with participant numbers varying across conditions. Statements 1–5 were rated on a 5-point scale: 1 = Strongly disagree; 2 = Disagree; 3 = Neither agree nor disagree; 4 = Agree; 5 = Strongly agree.

| ENGAGE n = 20 M (SD) |

Rich Reading and Reminiscing n = 20 M (SD) |

Strengthening Sound Sensitivity n = 18 M (SD) |

|

| 1. I learnt new information | 4.15 (0.75) | 4.20 (0.34) | 4.11 (0.68) |

| 2. I developed new skills | 4.00 (0.80) | 4.15 (0.81) | 4.28 (0.67) |

| 3. I noticed my child/ren are developing new skills | 4.35 (0.58) | 4.25 (0.64) | 4.14 (0.68) |

| 4. I enjoyed taking part | 4.40 (0.60) | 4.55 (0.51) | 4.22 (0.88) |

| 5. I would recommend Tender Shoots to other educators | 4.65 (0.49) | 4.50 (0.67) | 4.39 (0.78) |

| Number of nominations n (%) |

Number of nominations n (%) |

Number of nominations n (%) |

|

| Do you plan to continue using [practices from this module]? | 18/19* (95%) | 20 (100%) | 18 (100%) |

*Calculated based on number of available responses to this question.

Participation may have yielded other benefits for educators’ professional development. There were participating educators who did not participate in playgroup at the start of the project, but who began to attend playgroup with other educators during participation. There were others who went on to complete early childhood studies over the project period, and educators who continued to study, enrolling together in coursework in te reo Māori. Finally, last year an educator participated with us at the national home-based association conference; this year, she plans to attend again, and has successfully encouraged other educators to attend as well. Thus, participation may have contributed to educators’ growing sense of being part of a professional community, engaged with professional learning and development.

Did participation provide benefits for children’s learning and development?

Multiple sources of information are available to explore benefits for children’s learning and development, with data collection after the transition to school still ongoing. A primary focus of our evaluation to date has been educator–child interactions during shared reading and oral language interactions to better understand learning interactions in home-based ECEC. Analyses highlight the interactions between educators and children, before and after participation (Rouse et al., 2017; Timperley, Schaughency, Crawford et al., 2019). Importantly, comparisons of observations of educators’ reading with their children before and after participation in RRR point to benefits for children’s learning experiences, reflecting changes observed in educators’ teaching practices: children who participated in RRR with their educators talked more, were more responsive to educators’ questions after participation, and displayed greater independently assessed story comprehension (Timperley, Schaughency, Crawford et al., 2019). Future analyses will more closely examine educator–child interactions during and outside of shared reading and explore multiple indicators of children’s developing competencies over the course of participation in each module.

Overall, educators’ ratings indicated they perceived their children to develop new skills from participating in each of the modules (Table 6). Likewise, educators, visiting teachers, and research students have reported noticing children’s use of project-related learning from each of the modules. For instance, an educator described a child using the deep breathing she had learned in ENGAGE to successfully approach a giant stuffed moa she was frightened of on a museum visit. Another educator described a child who was previously difficult to console using strategies from ENGAGE to help get over upsets. After participating in oral language modules, educators described children displaying an increased interest in shared reading. They also described specific benefits related to each oral language module. For example, after participating in RRR, an educator relayed that, after reading a story featuring a cat that lived in two homes, a child whose parents had separated talked for the first time about his experience of living in two homes. Finally, visiting teachers and research students alike described children who had participated in SSS engaging in word play and sharing their developing awareness of language sounds.

We also heard instances of children using project-related learning outside of the home-based setting, which was likely fostered by communication between educators and parents about project activities. For example, a father relayed that after his daughter’s educator told him about the deep breathing they were doing as part of ENGAGE, deep breathing was successfully incorporated into falling asleep at bedtime. After hearing such stories, we added an open-ended question to the parent questionnaire asking for observations of projectrelated learning at home. Parents’ comments suggest perceived benefits for learning (a parent described her son as more inquisitive), examples from other learning modules (his interest in playing with language sounds and rhyme), with extension into other learning areas (emergent literacy). Finally, a former educator and participant, now working at a primary school, reflected on benefits she perceives for participating children’s successful transition to school.

Educators and visiting teachers also shared examples of communication between educators and parents. Educators spoke of talking more with parents, both to share project-related experiences with parents and to learn more about children’s experiences outside of home-based ECEC to get “ideas of things to talk about with children”. This two-way communication may serve to strengthen connections between home and ECEC, for parents and children, in turn yielding additional benefits for children’s learning and development (Diamond, Justice, Siegler, & Snyder, 2013).

Summary

Our evaluation of this 2-year project is still ongoing. We are continuing to follow children after their first year of school and to code and analyse data speaking to the benefits of participation over time and across modules. Analyses to date suggest:

- participation was a positive experience for educators and children, with the majority (72%) of educators participating in all three modules

- educators used resources as tools to tune into and scaffold children’s learning in areas covered in each module, supported by visiting teachers

- educators grew as reflective and intentional practitioners as they developed their professional kete over the course of participation and continue to incorporate strategies learned in their practice, with examples of use with other children and other areas of learning

- children displayed examples of learning associated with each of the modules

- observations of oral language interactions highlight inter-relations between educators’ and children’s language use. Future analyses will evaluate whether participation was associated with benefits for other indicators of children’s learning and development.

Implications for practice

This TLRI project sought to trial and evaluate an approach for supporting teaching and learning in the underresearched but important service-delivery sector of home-based ECEC. This report focused on initial evaluation questions involving educators’ uptake and experience of participating in this trial and begins to explore benefits of participation for educators, their practice, and positive learning outcomes for children. Although our evaluation is still underway, evaluation so far suggests the following implications for practice.

Recommendations for providers of professional learning and development (PLD) in home-based ECEC

PLD in home-based ECEC should include content about children’s development within areas of learning and resources to support translation of professional learning into educators’ practice with children. When educators understand development within areas of learning, they are more likely to provide learning experiences that foster learning within that domain (e.g., Piasta, Park, Farley, Justice, & Connell, in press). We focused on areas of learning that are associated with successful transitions from early childhood to school learning environments and experiences that support learning in these areas with educators serving 3½- to 5-year-old children. Recognising the diversity of the home-based ECEC sector, those designing PLD for home-based ECEC should consider what is important to the educators for whom they will be providing PLD and children in their settings and be informed by the relevant developmental research (Bromer & Korfmacher, 2017; Tonyan, Nuttell, Torres, & Bridgewater, 2017).

We also provided educators with resources to support learning experiences with children in each PLD module. Educators indicated they appreciated being provided with resources to use in practice with children. By providing resources, we aimed to facilitate educators’ use of strategies in practice with children, and, with repeated use, consolidation of skills in practice. Although resources were scripted to some extent to enhance ease of use (e.g., suggesting talk during reading or activities for ENGAGE), we encouraged educators to responsively use strategies to adapt learning experiences to scaffold children’s learning. Providing materials to support educators’ translation of professional learning to practice may effectively encourage provision of learning experiences. Importantly, educators seemed to use suggested learning experiences as opportunities to observe children’s responses, helping educators tune in to where children were in their developmental journey in an area of learning and consider how to scaffold children’s learning, in the context of educators’ holistic appreciation of their children as learners. Thus, resources may also have supported educators’ provision of high-quality and responsive learning experiences.

PLD in home-based ECEC should build on naturally occurring formal and informal social structures of home-based ECEC networks as contexts for situating professional learning. Material supports may have been helpful, but we didn’t provide them in isolation. Recognising the potentially central role of socially-mediated and relationship-based support for teaching and learning in home-based ECEC (Bromer & Korfmacher, 2017; Smith, 2015), we designed PLD to be delivered within networks with supervising teacherqualified co-ordinators (visiting teachers), consistent with the structure of home-based ECEC networks in New Zealand. By participating in PLD alongside educators, visiting teachers could support educators’ PLD by engaging in reflective dialogue about children’s responses to project-related learning experiences during their regular ongoing interactions. We also considered naturally occurring interactions between educators, leading to the identification of weekly playgroups as a potential touchpoint for fostering a learning community of participating educators in our home-based ECEC service. Those designing PLD for other home-based ECEC services should consider the social contexts in their communities that could be utilised or fostered to support teaching and learning in home-based ECEC.

PLD in home-based ECEC should be provided, and supported, over time. Professional learning and skill development are processes that develop with practice, over time. Therefore, PLD should be supported over time to facilitate translation to practice, with adaptation as needed to meet children’s and educators’ learning needs. Each of our modules included a 6-week implementation phase, and preliminary results suggest modulespecific benefits for practice (e.g., Timperley, Schaughency, Crawford et al., 2019) that may be sustained over time (Halperin et al., 2013; Timperley, Schaughency, Riordan et al., 2019). Some educators may not need the degree of support that we provided in each of our modules, whereas other educators may need additional support, over longer periods of time, for example, to meet the needs of children requiring greater learning or behavioural supports.

Because engaging in professional learning over time is associated with enhanced learning experiences for children (e.g., Markussen-Brown et al., 2017), we provided a series of PLD modules in which educators could participate over the course of the project. Ongoing engagement between educators, visiting teachers, and university researchers afforded opportunities for collaborative relationships to develop, acknowledged as important to supporting practice in home-based ECEC (Bromer & Korfmacher, 2017), and deepened researcher/ PLD provider understanding of the home-based ECEC practice context (Farley-Ripple, May, Karpyn, Tilley, & McDonough, 2018). Although our partnership has grown (Schaughency et al., 2016), with educators asking “What next?” and offering suggestions for possible directions, mechanisms are needed to support sustained research– practice partnerships to extend the practice-embedded work we have begun together (Snow, 2015).

Recommendations for home-based educators

Warm and encouraging relationships with adults are foundational to positive early learning environments for young children (Ministry of Education, 2017; Thompson, 2016). Building on this foundation, kaiako can support children’s learning through sensitive and responsive interactions that provide opportunities to actively practise developing skills and scaffold children’s learning (National Research Council, 2015; Pianta et al., 2016). The imagery of the whāriki, or woven mat, in Te Whāriki depicts the inter-woven complexity of children’s learning and development and acknowledges early childhood education as the start of young children’s educational journeys (Ministry of Education, 2017). Development in one learning area supports learning in other areas but each area has its own developing path (National Research Council, 2015). In this project, we provided PLD on three learning areas that develop during the preschool years—skills related to how children approach learning and oral language competencies related to meaning and sound. General recommendations to support learning in these areas are:

Provide play experiences that give children opportunities to practise developing learning-related skills. Learning-related skills are multifaceted and involve thinking (e.g., paying attention to and remembering details), feeling (e.g., modulating excitement or frustration), and doing (e.g., waiting for a turn and doing things carefully). A variety of play experiences present opportunities to practise these developing skills (see Table 1). Doing puzzles, playing card games involving matching, and making and copying patterns with play materials like blocks or beads all provide opportunities for children to practise developing thinking skills of attention and memory. Traditional children’s games like Simon Says provide opportunities for paying attention and waiting until Simon says. Learning to do new things involving motor skills (ball skills, Hop Scotch) provide opportunities for children to practise learning to learn, and, in so doing, children gain experience with the feelings that may accompany learning (uncertainty, excitement). However, some children also benefit from intentional introduction to the idea that there are things that they can do that affect how they feel, such as learning the difference in how they feel when they tense or relax their muscles.

Beyond suggesting what play activities educators can offer to give children opportunities to practise learningrelated skills, our experience points to the important roles that kaiako play in how play activities are delivered that results in positive learning experiences for children. This includes their considerations of when to introduce activities to best fit their settings and their children’s learning and how to adapt and scaffold activities so that they are fun and successful experiences for their children. Educators’ comments suggested introducing new skills to children can be challenging but many also shared sensitive and creative ways that they scaled tasks back for initial success and built from there. Similarly, although activities related to yoga and relaxation were less preferred by some educators for their children, others commented they incorporated these activities in their daily routines to help their children with transitions (e.g., to start the day or transition to quiet time).

Encourage children to talk. Children’s developing oral language competencies support their learning, personal wellbeing, and interactions with others. Findings from this project highlight the important part kaiako play in fostering children’s oral language development. Opportunities for nurturing children’s oral language include shared reading and everyday conversations with children. Storybooks expose children to new learning experiences, such as introducing words they may not have heard before. In addition, storybooks provide the chance to deepen thinking skills and socio-emotional learning when kaiako engage children in conversations about what they think might happen or how the character is feeling. Books with settings or themes familiar to children can spark conversations about children’s experiences. Re-reading the same stories allows kaiako to scaffold children’s learning through conversations during story reading.

Kaiako also foster children’s language when they engage children in conversations outside of shared reading. Talking together about children’s past experiences provides opportunities for inviting children to talk and share their experience. Kaiako can revisit children’s Learning Stories to prompt conversations with children about their experiences in ECEC (Reese, Gunn, Bateman, & Carr, 2019). In addition, they can talk with children’s parents to learn about things children have done with their whānau outside of ECEC for ideas for conversations with children about their experiences outside of ECEC. Kaiako can likewise bring the shared experience of story reading to conversations with children outside of reading. For example, when kaiako use words that were introduced during story reading at a later time, such as during informal play with children, it deepens children’s understanding of those words (Toub et al., 2018). Similarly, kaiako can use stories as prompts for conversations about related situations that children have experienced, both positive and negative. Educators who participated with us commented on the potential benefits of these conversations. They said that children often readily engaged in conversations about positive experiences and emotions, which educators saw as supporting children’s sense of wellbeing. Their comments suggested that talking about negative experiences and emotions with children was sometimes more challenging than talking about positive experiences, but that it helped provide children with ways to talk about negative emotions they experienced in their daily lives.

Provide opportunities for children to actively play with language sounds. Being tuned in to the sounds of a language supports children’s language- and literacy-related learning (Shanahan & Lonigan, 2010). Reading sound-rich books is one way educators can help children tune into language sounds. Sound-rich books are those that use literary devices such as repeating words or phrases, rhyme, or alliteration that help call children’s attention to the sounds of language. Importantly, our research suggests that when adults read sound-rich books with children, they are also more likely to interact with children about language sounds, deepening opportunities for children’s learning (Riordan et al., 2018; Rouse et al., 2017). Finally, the combination of repetition within stories and repeated readings over time helps children anticipate what comes next and can set the stage for playful interactions in which children are invited to actively participate and join in during story reading, providing opportunities to practise developing skills. The key, one educator commented, is to remember to have fun.

Kaiako can also help children tune into, and play with, language sounds outside of shared reading—through singing or reciting nursery rhymes or silly songs that play with language sounds or engaging in wordplay involving language sounds with children. These activities can be done anywhere, such as on a walk or in the car or bus when travelling to activities with children, with participating educators describing such activities becoming something they regularly do with their children when they are on the way somewhere.

Concluding comments

Kaiako play important roles in fostering children’s learning and development. By incorporating learning experiences into everyday activities, kaiako provide opportunities for children to practise developing skills that kaiako can support and scaffold. Kaiako can use their observations of children’s developing skills within learning areas, along with their holistic knowledge of their children, to effectively extend children’s learning over time. Ideas described in this project were developed with specific areas of learning in mind. Other learning experiences can support learning in other areas. Mentoring visiting teachers and early childhood professionals can support kaiako in home-based ECEC through provision of resources and engaging in reflective practice on how best to meet children’s and kaiako learning needs.

Footnotes

- Consistent with the approach taken by the Ministry of Education (Kōrero Mātauranga, 2018b), we use the term “educators” to refer to kaiako providing home-based ECEC. ↑

- Consistent with the approach taken by the Ministry of Education (Ministry of Education, 2017), we use the term “kaiako” to broadly refer to adults who are engaged in ECEC. ↑

- In discussions of quality in early childhood education (ECE), the quality of interactions directly experienced by children and families are sometimes referred to as process quality to distinguish this aspect of quality from structural features such as adult–child ratio (Slot et al., 2018; Smith, 2015). ↑

- This rationale has been updated to incorporate developments since the time of our initial proposal. These developments include, but are not limited to, the revision of Te Whāriki (Ministry of Education, 2017), the review of home-based ECEC in New Zealand (Kōrero Mātauranga, 2018b), and a special issue of an early childhood journal devoted to home-based ECEC (Early Education and Development, 2017, 28(6)). ↑

- The process of establishing links and connections with others. ↑

References

Anthony, J. L., & Francis, D. J. (2005). Development of phonological awareness. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 14(5), 255– 259.

Aram, D., Fine, Y., & Ziv, M. (2013). Enhancing parent–child shared book reading interactions: Promoting references to the book’s plot and socio-cognitive themes. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 28, 111–122. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2012.03.005

Atkins, M. S., Rusch, D., Mehta, T. G., & Lakind, D. (2016). Future directions for dissemination and implementation science: Aligning ecological theory and public health to close the research to practice gap. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 45(2), 215–226. doi:10.1080/15374416.2015.1050724

Biddulph, F., Biddulph, J., & Biddulph, C. (2003). The complexity of community and family influences on children’s achievement in New Zealand: Best evidence synthesis. Wellington: Ministry of Education.

Bowne, J. B., Magnuson, K. A., Schindler, H. S., Duncan, G. J., & Yoshikawa, H. (2017). A meta-analysis of class sizes and ratios in early childhood education programs: Are thresholds of quality associated with greater impacts on cognitive, achievement, and socioemotional outcomes? Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 39(3), 407–428.

Bromer, J., & Korfmacher, J. (2017). Providing high-quality support services to home-based child care: A conceptual model and literature review. Early Education and Development, 28(6), 745–772.

Clifford, A. (2017, November). Te kete kōrerorero: Understanding how educators kōrerorero with tamariki in home-based early childhood education. Paper presented at the Māori and Indigenous Doctoral Students Conference, Te Pūtahi-a-Toi, Massey University, Palmerston North.