Introduction

Schools have a role to play in improving youth social emotional wellbeing (SEW) by supporting their development of social-emotional knowledge, skills, and capacities through social emotional learning (SEL). However, schools in Aotearoa New Zealand vary widely when responding to and promoting tamariki wellbeing (Education Review Office, 2015a, 2015b). More successful schools show a comprehensive approach, including more explicit curriculum connections (Boyd et al., 2017). Enhancing SEW and SEL practices in schools can play a part in mitigating the adverse effects that low rates of wellbeing have for tamariki, particularly for Māori, Pacific, and other underserved youth (Bishop et al., 2009).

SEL programmes are effective for fostering students’ wellbeing through social-emotional capability development, including decision making, stress management, problem solving, and reductions in conductrelated difficulties and emotional distress (Corcoran et al., 2018; Durlak et al., 2011; Taylor et al., 2017). However, they are often seen as a burdensome addition to an already full school curriculum, made more challenging due to the focus on strict adherence to fidelity in implementation (Green et al., 2018). These programmes have also been challenged for their tendency to ignore the role of culture in SEW and SEL, and for paying little heed to the specific socio-cultural contexts of communities (Reicher, 2010). These shortcomings mean that SEL programmes often fail to meet the diverse strengths and needs of learners. These concerns have led to calls for the development of SEL programmes that are culturally and linguistically responsive to, and grounded in, local socio-cultural perspectives of SEW (Barnes, 2019; Macfarlane et al., 2017).

Noting the synergies between Western models of SEL and Māori approaches, Macfarlane et al. (2017) argued that the “application of SEL programmes founded on Māori constructs is an antidote to Māori disparity” (p. 286). Such practices challenge the subjugation of Indigenous peoples and the notion that the cultural and linguistic practices of Indigenous groups are deficient or problematic, requiring remediation (Rogoff et al., 2017). Indigenous cultural practices are sources of SEW that can benefit all individuals (including dominant cultures) by expanding their repertoire of skills and practice (Rogoff et al., 2017).

These research-informed perspectives, and calls to action, were the impetus for our project. We sought to understand how schools could foster SEW in tamariki through the use of SEL practices that were culturally and linguistically responsive to the Aotearoa New Zealand context. Eight teachers and school leaders from a primary and a secondary school participated in the project. Three overarching aims, with aligned research questions, framed our work:

Aim 1: Develop a framework of SEW that is responsive to te Tiriti o Waitangi and the context of Aotearoa New Zealand.

- Research question 1: How do kaiako, tamariki, whānau, iwi, and hapū perceive SEW?

- Research question 2: How do these different perspectives inform the development of a culturally and linguistically sustaining construct of SEL?

Aim 2: Develop culturally and linguistically responsive pedagogical practices for SEL within the classroom context.

- Research question 3: What evidence-based, classroom-led, SEL-focused practices enhance the learning engagement of students of all ethnicities in the classroom and their self-perception of SEW at school?

Aim 3: Develop exemplars of practice to support the implementation of culturally and linguistically responsive SEW & SEL by schools.

- Research question 4: What research-informed concepts, processes, and procedures, that are mutually informed and supported by whānau, iwi, and hapū, support schools, and teachers, to enhance SEL and SEW in the classroom?

Research design

We are a team of Māori and non-Māori researchers. Our project was grounded in, and guided by, the relational and partnership components of te Tiriti o Waitangi (see O’Sullivan et al., 2021) and Kaupapa Māori research principles (Smith, 2012) that acknowledge the centrality and legitimacy of te reo Māori, tikanga Māori, rangatiratanga, and mātauranga Māori. This enabled culturally responsive practices to be developed and enacted across the project (Macfarlane et al., 2014).

We utilised design-based research incorporating iterative cycles of inquiry (The Design-Based Research Collective, 2003) to enable the development of new theories, methods, and practices within naturalistic contexts and inform other classrooms and schools (Barab, 2006). Support and guidance for the project were provided by members of Te Taumutu Rūnanga Education Committee. Ethical approval for the project was granted by the University of Canterbury Education Research Human Ethics Committee (2019/08/ERHEC).

Our research was carried out over a period of upheaval that included the 2019 Christchurch mosques terrorist attack and the global COVID-19 pandemic. These circumstances affected all aspects of the project, resulting in adjustments to the schedule of initial data collection and analysis, research hui, kaiako implementation of SEL practices, and the timeline of the project being extended through September 2021.

Collaborating kaiako and other participants

We partnered with Te Taumutu Rūnanga and two schools in their rohe that had recognised wellbeing as a priority for their tamariki. The first school was a contributing primary school with students from Years 0–6 and the second school was an English-medium secondary school with students from Years 7–13. A total of eight kaiako, Māori and non-Māori, participated as collaborators and co-researchers. Two kaiako were from the primary school; one taught in a Level 2 immersion te reo Māori context catering for ākonga from Years 4–6. Within this context, ākonga are taught in te reo Māori between 51%–80% of the time; and one taught Year 6 learners in an English-medium context. A third participant, who held a dual role as deputy principal and kaiako of Years 4–6 learners, was on leave during 2019. Five kaiako collaborated from the high school. One kaiako held a dual role as deputy principal and teacher. Three kaiako taught in Years 7 and 8, with one kaiako participating across the entire project, one leaving the school at the end of 2019, and one joining the project in 2020. Another kaiako, specialising in the English curriculum area joined the project in 2020. Across the project, a total of 100 primary and 115 secondary tamariki were involved. Families, whānau Māori and hapū who participated were those who held connections with these students. In this report, we refer to families and Māori whānau as whānau.

Project methods

We undertook three cycles of inquiry: each focused on one of the project aims and was guided by the associated research question(s). The cycles were iterative, meaning we looped back to prior cycles to ensure we continuously strengthened the alignment of theory, design, and practice across the project. We utilised six methods in an integrated approach.

Wānanga

Wānanga were used to gather kaiako and whānau understandings of SEW, and was our key method during the initial cycle of inquiry. Wānanga are gatherings that enable in-depth discussion and sharing of information amongst individuals to co-construct knowledge using joint meaning making; thus, the wānanga situated all participants as both learners and knowledge sharers (Mahuika & Mahuika, 2020). Wānanga are safe spaces for individuals to share cultural and linguistic knowledge in flexible and open-ended ways, with guiding questions that are adapted, revised, and used flexibly to enable participant views to be shared and support generative co-construction of knowledge and understandings.

We conducted five wānanga with whānau, and two with kaiako. Whānau were invited to participate in one of a series of 12 wānanga, offered at a variety of times. The wānanga were hosted at the collaborating schools following consultation with the rūnanga. A total of 11 whānau members participated in the wānanga, each lasting approximately 90 minutes. Whānau participants were asked to reflect on and respond to questions designed to elicit their understanding of what wellbeing meant for them and their tamariki, what fostered or disrupted wellbeing, and how they encouraged a return to wellbeing.

The two kaiako wānanga took place over a typical 6-hour workday. At these wānanga, kaiako shared their initial perceptions and understandings of wellbeing, and were guided to explore these further through engagement with a range of topics including: the role, function, and components of emotions; emotional literacy; Te Whare Tapa Wha (Durie, 1998) as a SEW framework and CASEL Social Emotional Learning domains (CASEL, 2020); the effect of colonisation on Māori emotions and emotional regulation, living as Māori, and Indigenous ways of learning and healing, and developing wellbeing through culturally responsive practices.

The wānanga incorporated mātauranga Māori and tikanga Māori, including karakia, waiata, and manaakitanga with the sharing of kai. The wānanga further embodied whakawhanaungatanga, supporting the development of relationships between individuals by connecting them to the whenua, whakapapa, and whānau. This included providing participants the opportunity to self-determine whether to engage in a form of pepeha at the beginning of the wānanga.

Wānanga data were collected by a member of the research team within field notes. The accuracy of the field notes was checked with participants throughout the wānanga, with all efforts made to record comments verbatim. No names or data/information that participants felt would identify them were captured in the field notes.

Student questionnaires

Three standardised questionnaires provided data on how tamariki perceived aspects of their SEW. The self-report scales reflected three aspects underpinning wellbeing: 1) Sense of Coherence: Orientation to Life Questionnaire (Antonovsky, 1987); 2) Self-Efficacy Questionnaire for Children (Muris, 2001); and 3) Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (Goodman, 1997). The purpose of gathering these data was not to definitively measure SEW but to follow Scott’s (2012) notion of measurement as a means to gain understanding of tamariki self-perceptions of SEW. This notion guided how we drew on these data in our Findings sections of this report.

During the initial inquiry cycle, we collected data from all ākonga in the classrooms of participating kaiako. The data from ākonga were analysed and a descriptive summary or class profile was shared with each kaiako. As co-researchers, the kaiako used these data to deepen their understanding of their ākonga and their pedagogical practices in their classroom. However, within this report, data are only presented for those tamariki whose parent/caregiver consented to it being used for these purposes (n = 74; 42 primary and 32 secondary). This dataset was analysed using SPSS (version 25) to provide descriptive statistics for the whole cohort of ākonga related to wellbeing to inform our findings and wider project aims. The complete analysis and discussion of this dataset is provided in the Appendix.

Intentional noticing

Our use of intentional noticing served as a means of supporting kaiako in bringing specific aspects of classroom practice to the forefront of their attention for the purposes of deconstruction and reconstruction of understandings. This method was introduced as we transitioned into the second inquiry cycle beginning in term three of 2019 and was utilised throughout the remainder of the project. We drew exclusively on Mason’s (2001) concept of “the discipline of noticing”; an agentic practice that enables individuals to deepen and broaden their understandings of aspects of their professional practice. Noticing requires an intentional stance beyond casual attention to the ordinary and habituated practices within one’s experiences, turning one’s

full attention to the moment, action, or activity occurring, and noting its salience and one’s personal internal response. This blending of reflective practice and action research fosters an inquiring stance toward practice, which enabled the kaiako to inform their understandings of SEW/SEL and guide future classroom actions and practices.

Research journals

Kaiako kept research journals where they recorded their intentional noticing, reflections, and other queries and insights throughout the project. They used whatever format worked best for them, including notebooks and online/digital formats. The journals focused on supporting kaiako in honestly and openly exploring their journey through the project. Kaiako chose how and when to share from their journal. Once shared with the collaborative team, this information was captured as data in field notes.

Collaborative research hui

Collaborative research hui formed the key project method through the remaining inquiry cycles. Six hui were held from mid-2019 through the end of the project in 2021, each representing a 6-hour workday for the kaiako. We used the principles of wānanga to guide these sessions, focusing on creating a safe space to foster shared learning, open dialogue, and generative co-construction of knowledge. These hui were distinguished from the initial wānanga, however, in that our focus was on shared analysis and sense making of project data.

For example, the first hui focused on analysing the wānanga data. Each team member independently reviewed the data making their own initial interpretations (Glaser & Strauss, 1967). The focus was on identifying broad commonalities, variations, and points of difference within and across the data. These points were then discussed collectively to identify initial categories, and then annotate and code the data (Strauss & Corbin, 1998). The collective coding was used to refine and identify the key themes related to SEW and attributes of SEL.

At subsequent hui we engaged in joint meaning making related to: student questionnaire data to support teachers’ understanding of their classroom data; discussion of kaiako vignettes of intentional noticing and insights from their journals; discussion of shared readings and research; and sharing SEL strategies they were trialling, including tamariki responses to the new or refined practices. These project-level data were captured as either collaboratively generated notes on the whiteboard, and then copied into research team field notes, or directly captured in the field notes by one of the research team. A key outcome from these hui was the co-construction of a set of Reflective Posters as a shared SEL pedagogical tool for use in the classroom with tamariki. The kaiako had identified the need for tamariki to have supported practice reflecting on their own emotional states and feelings, and the influence of situations and relationships on their emotions.

Researcher hui

The university-based researchers held regular hui throughout the project, with the focus being ensuring the iterative connection of our work across the cycles of inquiry. We routinely examined and synthesised our emerging data and findings in light of existing research on SEW/SEL to ensure the coherent development of new theoretical and practice-oriented insights. This was especially important given the limited number of kaiako and school settings we were working with, and the significant increase we noted in the scholarly work in this area across the project’s duration. Researcher hui also guided planning for subsequent work with the kaiako and guided our ongoing collaboration and engagement with Taumutu rūnanga.

Findings

RESEARCH AIM 1:

Develop a framework of SEW that is responsive to te Tiriti o Waitangi and the context of Aotearoa New Zealand

SEW is a complex concept to address because it is an ideal and not a fixed state of being (McLeod & Wright, 2015). It can be defined as relating to how individuals think and feel, not only about themselves (Manning & Fleming, 2019), which is influenced by historical, social, cultural, and psychological factors (Scott, 2012). SEW is fostered through the development of SEL. Rather than being universal, SEL attributes vary between social contexts and cannot be applied across different cultural contexts (Anziom et al., 2021). Informed by these understandings, our first aim was to develop a SEW framework pertinent to the unique social context of educational settings, with aligned SEL attributes that reflected our bicultural context. We began by gathering the perceptions of SEW and SEL held by kaiako, tamariki, and whānau.

Participant perceptions of SEW

Relationships: Relationships were the overarching and most fundamental aspect of SEW for all participants. Relationships were understood to be multidimensional, including one’s relationship with self, relationships with others, relationships with and understandings of culture and language, and relationships with learning. Positive relationships were viewed by whānau as being characterised by supporting one’s positive sense of self, affirming and appreciating you as a whole person, and creating a “safe space to be yourself”. In this way, relationships both served to help foster SEW, and also reflected how SEW is nurtured and manifested in actions.

The influence of socio-historical experiences in developing wellbeing was identified within the relationships that existed between whānau, communities, and schools. Whānau were clear around the importance of kaiako “know[ing] who whānau is” and that the development of SEW in tamariki was a “collaboration between school and home”. For whānau, kaiako need to understand the myriad of familial contexts present among their tamariki and to be responsive to culture, language, and identity and the role of societal forces in the development of genuine relationships that foster SEW. Whānau emphasised the importance of school, and the high aspirations they held for their tamariki, which contributed to SEW. These aspirations favoured holistic and collective aspects related to community and whānau over more individualistic aspects.

Another key SEW aspect had to do with tamariki peer relationships. Whānau noted that navigating peer relationships was a particular concern and influence on tamariki and that their emotional states were often heightened in these circumstances, affecting SEW. Kaiako also noted the challenges in peer relationships, particularly in the secondary context, commenting that tamariki often used emotive language with each other, which was often derogatory and laden with racial overtones. Both kaiako and whānau perceived that these aspects of peer relationships had become unconsciously normalised within some groups of tamariki. The importance of peer relationships was further supported by the student questionnaire data. These data showed that many tamariki, both primary and secondary, experienced difficulties in relating to their peers and perceived themselves as having low levels of prosocial skills that would support such relationships.

Belonging and feeling connected: Whānau identified the importance of having “connections to home and belonging” to the wider cultural community as a fundamental aspect of SEW. Wider whānau and community, such as close friendship groups, local neighbourhoods, sporting and religious groups, and iwi and hapū organisations, were seen by whānau as a key social support system for tamariki and for them. Whānau sought out these connections for various reasons, including “feeling inspired” or “inspiring others” and “creating connections and opportunities for engagement—shared load”. These whānau and community relationships were integral for tamariki in developing a sense of self and identity grounded in their culture and language.

Belonging and connectedness also related to relationships with schools. Whānau reported that when these relationships were strong it “felt like all the boxes were ticked” and that they were “all on the same page”. Whānau reported that schools that fostered strong relationships “created connections and opportunities for engagement”, including through “shared cultural connections”, and an understanding of different familial contexts. They characterised these relationships as occurring when schools were responsive to culture, language, and identity, as well as societal forces. However, whānau also reported prior negative educational experiences that included overt racial assumptions and stereotyping, and verbal abuse and bullying. Whānau were clear that such experiences derived from assumptions around culture, language, and identity within the educational context and wider society. They highlighted how these negative experiences could disrupt the development of positive relationships and feelings of belonging.

Identity and sense of self: Both whānau and kaiako identified being understood, showing/being shown empathy, and “feeling connected” within relationships as contributing to one’s sense of self, and thus supported positive wellbeing. One whānau member spoke about this as teaching them “to be yourself, and not what or who other people think you are” and expressed how important one’s own sense of identity was to SEW. For whānau, identity was grounded in culture and place, and linked back to the sense of belonging. Kaiako spoke clearly to the role of identity in SEW, of tamariki “feeling strong” in who they are and knowing their strengths and interests. However, kaiako typically spoke in more general terms about the importance of knowing the cultural and linguistic backgrounds of tamariki and whānau. In fact, only one kaiako talked explicitly about the role of culture or language in SEW. That kaiako commented that “culture can affect one’s understandings”.

Whānau shared that tamariki with a strong sense of self “had a spark” or “a spirit” that reflected their selfassuredness or confidence. Tamariki were open to sharing about their experiences and communicating their interests and ideas with others with whom they held positive relationships. Kaiako similarly spoke of “sharing of self” and having a sense of self-efficacy. Supporting tamariki to develop confidence helped them “step outside their comfort zone” and learn from new experiences. Data from the student questionnaires provided further insights, indicating primary tamariki held more positive views of their ability to use skills to meet specific goals within academic, social, and emotional domains than secondary tamariki. Similarly, primary tamariki held more positive perceptions of their ability to cope with stressful situations. This included feeling better able to rationalise internal and external stimuli, manage stress in their lives, and problem solve through stressful experiences.

Whānau noted that their focus on relationships and engagements with their wider whānau and community were often related to the explicit desire to support tamariki in developing SEL-related skills. This included helping them become “more self-sufficient” and develop “planning and problem-solving skills”. They identified these relationships as ones that supported tamariki to develop a sense of autonomy and independence, as well as fostering interdependence or a sense of mutuality and responsibility to others. Whānau viewed these contexts as implicitly fostering SEW through working with a range of community members across generations and in different settings over time.

SEL attributes

Communication: Communication was viewed by all whānau and kaiako as critical to developing tamariki wellbeing. They consistently identified that communication skills and knowledge helped foster the necessary positive conditions for building and maintaining positive relationships, which underpinned SEW. Kaiako and whānau spoke of how they both implicitly and explicitly developed verbal communication skills in ākonga that fostered SEW. However, whānau were more likely than kaiako to emphasise the role of body language in communicating and understanding the current SEW of tamariki. Whānau talked about how tamariki body language shifted when wellbeing was compromised, with one whānau member describing this as “the stormy, changed attitudes and lack of eye contact”. Whānau also highlighted the relationship between verbal and body language and how it was related to culture, language, and identity. They noted how one expressed themselves was heavily embedded within cultural norms, including birth order and speaking rights, as well as intergenerational socio-historical and current experiences.

Kaiako noted that quality communication required both receptive (listening) and expressive (speaking) skills and that communicative knowledge and skills contributed to tamariki confidence. As one kaiako noted, confidence supported tamariki “being brave stepping out of their comfort zone” so they had opportunities to learn from new experiences. Whānau shared similar views in how being a strong communicator and orator was a reflection of confidence and related to holding a strong sense of one’s self and whānau. However, whānau identified differences in how ākonga used verbal language between whānau and school contexts, noting a lowered propensity to use verbal language to communicate effectively within the school context. This highlights the importance of understanding how context, both the setting and existing relationships, can influence a person’s actions and use, or non-use, of existing skills.

Understanding emotions and emotional states: Kaiako and whānau identified that understanding emotions was critical to communication in relationships. Understanding emotions and emotional states enabled a person to recognise and normalise feelings and associated behaviours in themselves and others, and to facilitate the necessary communication to maintain relationships. Whānau and kaiako participants all identified that developing social-emotional capacities extended beyond focusing on oneself.

Whānau emphasised the importance of tamariki developing the ability to recognise and verbalise emotions as a fundamental life skill. Having this sort of emotional vocabulary was seen as critical to recognising and managing different emotional states and they viewed it as a crucial skill for themselves and their tamariki to develop and use together as they responded to the different aspects of life. Some whānau recognised that their tamariki did not articulate emotions in words, “at school they don’t do this so well” and returned to the importance of being able to read body language as a key to identifying emotional states in others. Whānau felt positive that the development of knowledge and vocabulary related to emotions and emotional states, and the skills to communicate the understandings with others needed to happen through modelling and explicit SEL teaching at school.

Normalising and reframing social-emotional experiences: Understanding and normalising the emotional experiences that are integral for fostering and maintaining relationships was seen as fundamental for both whānau and kaiako. They noted that relationships were reciprocal and mutually reinforcing, and all those in the relationship needed to demonstrate shared concern for it. Whānau expressed the need to acknowledge that people bring their whole self to the relationship, including their social-cultural understandings, perspectives and prior experiences, understandings of their role and responsibilities, and social-emotional skills. Therefore, it was important to understand different perspectives and emotional states and learn to navigate and engage those differences.

One aspect of normalising experiences that whānau and kaiako highlighted was being “respectful of where they are at” and their current social-emotional knowledge and skills. This was coupled with offering support and guidance. Whānau spoke about “being good role models”, with whānau describing this as modelling how to verbalise and name their own emotional states and supporting their tamariki to do the same. Whānau talked about working with their tamariki to reframe problems “in a life skill kind of way, not a parent telling him what to do” way, which allowed them to work on solutions together.

This notion of reframing, coupled with perspective taking, was seen by whānau as a key social-emotional skill for tamariki. This included helping tamariki process challenging engagements with peers. For example, whānau shared a story of their tamariki coming home upset “when a friend didn’t play with me today”. Whānau used this as an opportunity to ask the tamariki to share how that felt, and also what the tamariki thought the friend might be feeling or needing that day, while also explaining “this was today and tomorrow can be different”. Another facet of reframing and perspective taking related to challenging assumptions. Whānau spoke about how people “have our own assumptions” influenced by “what we’ve been taught growing up”. They felt tamariki needed to understand such assumptions and be enabled to view interactions and contexts from perspectives different to their own, which provided “opportunities to change” and grow.

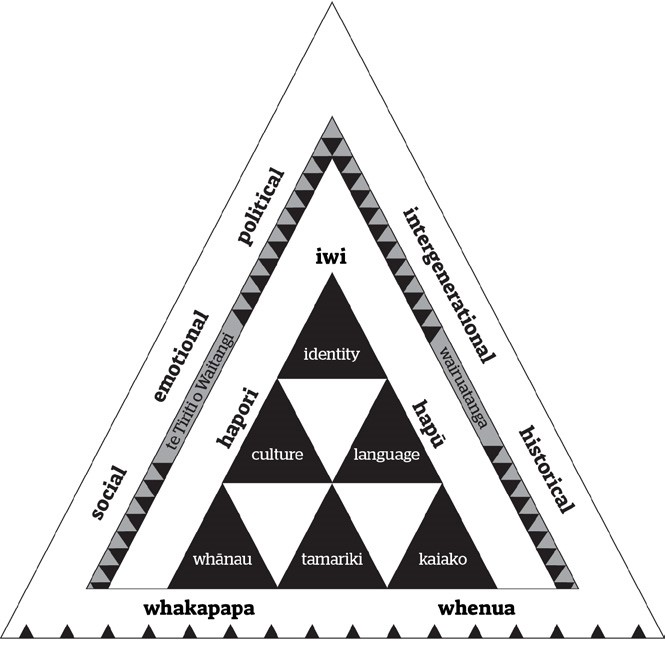

Drawing the threads: Mātauranga Oranga, a Te Tiriti-based, ako framework for SEW

The research team considered our findings in light of the SEW/SEL research base, with particular focus on Māori and Indigenous scholarship. Drawing these threads together, our Māori researchers developed Mātauranga Oranga, a Te Tiriti-based, ako framework for SEW (see Figure 1). Taumutu Education Advisory members provided their insights and recommendations on Māori concepts and language for the framework. Our holistic SEW framework with enabling SEL constructs has been developed specifically for the educational context and responds to Macfarlane et al.’s (2017) call for the development of SEL approaches founded on Māori constructs (p. 286).

FIGURE 1. Mātauranga Oranga

The name Mātauranga Oranga acknowledges the importance of Māori perspectives, knowledge, and understandings in fostering and sustaining wellbeing in tamariki, rangatahi, and kaiako in Aotearoa New Zealand. Mātauranga Oranga is represented through the aronui tāniko weaving pattern. The pattern reflects the understanding that whakawhanaungatanga, which is the process of developing and sustaining relationships with oneself and others, is the foundation of wellbeing. Whakawhanaungatanga is represented through whakapaka and whenua, and the interconnections between tamariki, whānau, and kaiako within the wider embrace of hapori (communities), hapū, and iwi. Wellbeing is influenced by and fostered through te taiao, the social, emotional, political, intergenerational, and historical aspects of the world we live in. Te Tiriti o Waitangi and wairuatanga run throughout the model, representing their centrality. The model reflects the depth, complexity, knowledge, and understanding required to promote and maintain te Tiriti o Waitangi partnerships and relationships within an educational context, and in doing so embraces all peoples.

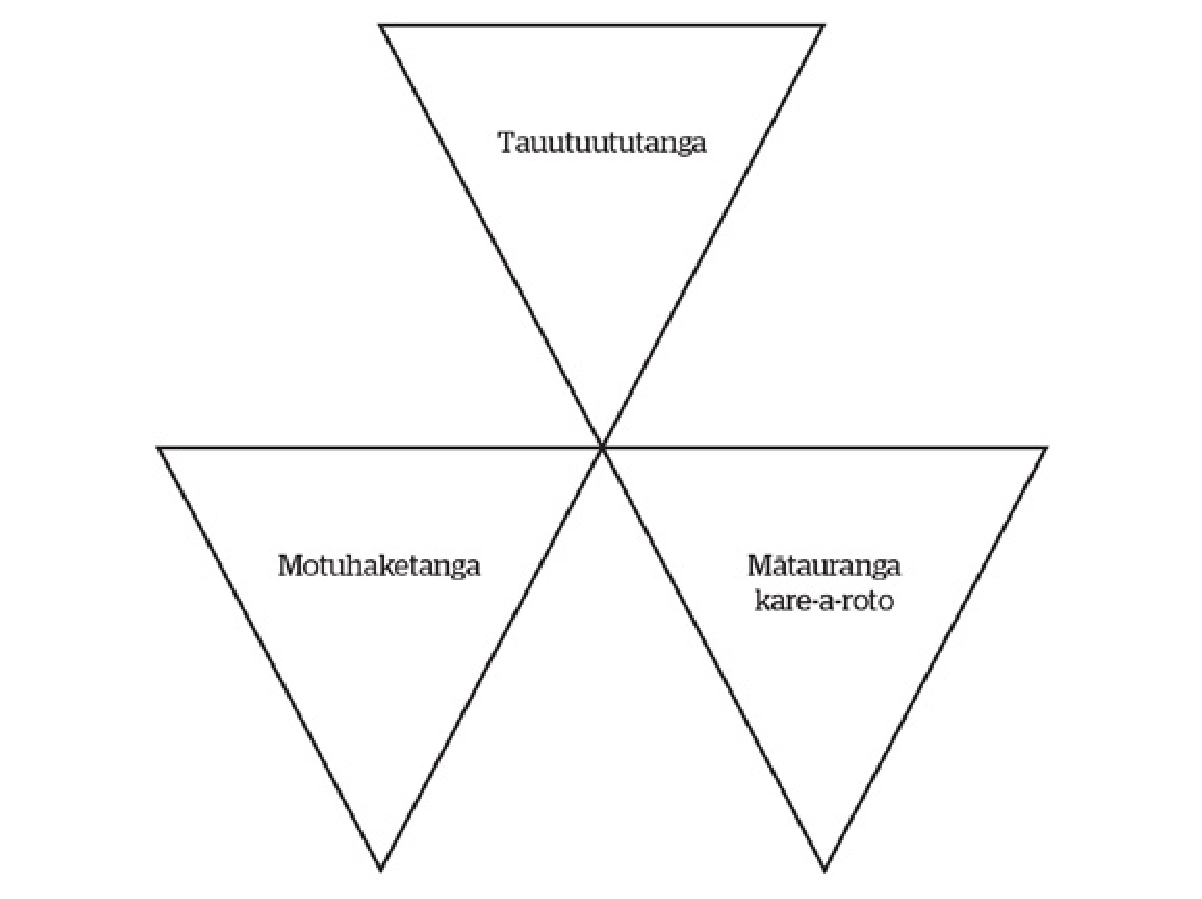

At the centre of the model is Ako Torowhānui, a culturally responsive and sustaining construct of SEL. It is comprised of three interrelated and mutually supporting attributes (Figure 2) that underpin and enable the development of SEL knowledge and skills.

FIGURE 2. Ako Torowhānui

Tauutuututanga reflects the importance of communication within relationships. It refers to and draws upon the tauutuutu system (as distinct from the pāeke system), which is used during pōwhiri in some regions, and involves alternating speakers between tangata whenua and manuhiri. In this way, tauutuututanga emphasises the Māori concept of reciprocity relating to the two voices of whaikōrero. Whaikōrero requires the skills of listening carefully to each other and speaking to the thoughts and ideas each brings. It captures the relational aspects of mutuality, empathy, and giving respect to different perspectives that are needed to foster and maintain positive relationships.

Motuhaketanga reflects the Māori concept of the interconnection of autonomy, independence, and selfguidance. These SEL attributes were reflected in participants’ perceptions of SEW as encompassing a positive sense of identity, sense of self, and self-efficacy.

Mātauranga kare-a-roto encompasses the knowledge, understanding, and skills of emotions and the cultivation of emotional awareness. This constellation of SEL knowledge and skills was identified by all participants as being critical in understanding oneself and fostering relationships that enable positive SEW.

RESEARCH AIM 2:

Develop culturally and linguistically responsive pedagogical practices for SEL within the classroom context

Teachers play an instrumental role in developing SEW in tamariki, both through SEL practices (Durlak et al., 2011; Zembylas, 2007) and the teacher–student relationships they foster (Sabol & Pianta, 2012). This understanding informed our second project aim, enabling kaiako to enhance classroom SEL practices in response to their local school and socio-cultural contexts. We were guided by the concepts underpinning Mātauranga Oranga: A te Tiriti-based ako framework for SEW, in particular Ako Torowhānaui as the enabling culturally responsive and sustaining construct of SEL. We focused on strengthening existing practices and adding new practices responsive to tamariki existing knowledge, skill, and learning needs. We found that SEL can be embedded into classroom practices without the need for structured programmes. Through shared discussion and collaborative analysis of kaiako practices we identified three overarching SEL-focused pedagogical principles that support this implementation.

Use reflective tools and protocols to develop emotional awareness

Two reflective tools were used by kaiako that were salient to both their tamariki development of SEL knowledge and skills, and their own learning. These were the co-designed Reflective Posters and the kaiako use of intentional noticing protocol, as previously described. Taken together, these reflective tools supported tamariki and kaiako to strengthen their relationships with and among each other while developing their respective SEL knowledge and skills.

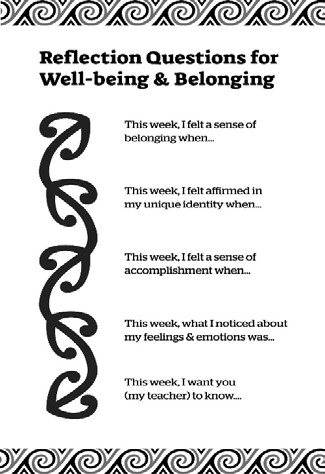

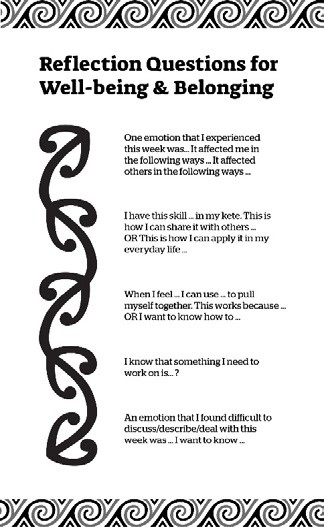

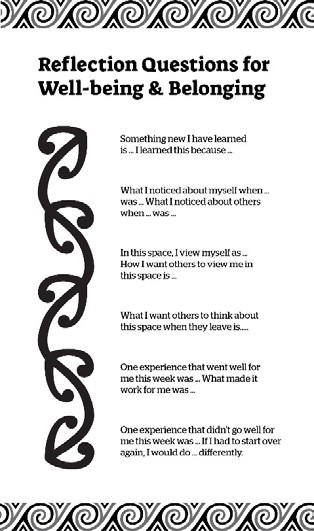

The Reflective Poster 2019 (Figure 3) focused on four aspects that included belonging, identity, self-efficacy, and emotions. A second set of Reflective Posters (Figure 4) was developed in 2020 in response to teachers’ noticing the need to refine and deepen tamariki reflections toward recognising their SEL skills in relationships and contexts.

FIGURE 3. Reflective Poster (2019)

FIGURE 4. Reflective Posters 2020

|

|

Tamariki were asked to engage in this reflective process once a week. Kaiako encouraged student agency through self-selection of a focus question and their choice of method for reflection (i.e., hard copy or online). They were able to share their reflections with their kaiako at their own choosing. Kaiako noted these reflections provided them with a “snapshot of individual kids” that enabled them to ask “What does this mean that I need to bring into the conversations I have with the kids?”

Kaiako found that the Reflective Posters supported them in fostering holistic and reciprocal relationships between themselves and their tamariki, and among their tamariki. The focus on reflection provided a specific learning context within which they could foster a repertoire of emotional vocabulary for understanding emotions and emotional states. Through intentional noticing, kaiako were able to more closely attend to tamariki language and actions in the classroom, looking closely at how and to what extent tamariki were developing understandings of emotions and emotional states. Kaiako shifted their language to talk with tamariki about “what I am noticing is …, what are you noticing” to open more dialogic and inquiry-focused conversations. Over time, kaiako noted tamariki were able to better “understand and verbalise their own feelings” and respond to classroom situations. This shifted the conversations away from evaluating or judging emotions or feelings toward reframing or considering “what they are telling me”. Kaiako noted how this knowledge and skill contributed to increased confidence allowing tamariki and kaiako to move out of their respective comfort zones to further develop their repertoire of socio-emotional skills. One kaiako captured how the classroom had become a space for tamariki “to feel safe in order to practise expressing their feelings and emotions and know whatever they say will be supported and not judged”.

Explicitly coach SEL knowledge and skills

Through the tamariki reflections, and their own noticing, kaiako identified aspects of SEL that were being implicitly engaged through modelling. They determined the need to shift to a more intentional approach, and reframed toward an explicit coaching model. This included foregrounding key knowledge to provide support and scaffolding as they deconstructed classroom learning experiences with tamariki. One kaiako framed this as “setting up the teachable moment” to better enable tamariki learning to reframe and reconstruct understandings. This shift reflected a learner-focused response to explicit skill building based on tamariki-demonstrated strengths and learning needs. With guidance, SEL knowledge and skills became a core practice and “an embodied way of doing things” for tamariki.

Kaiako used a variety of individually developed pedagogical practices to support this explicit teaching. These included daily check-in charts or journals where tamariki shared how they were feeling, reflection circles, circle time, Māori cultural narratives and literature from a range of cultural groups, role-playing, engaging with the maramataka and kupu Māori for and perspectives on emotions, and karakia and waiata to develop wairuatanga. Primarily, the strategies targeted relationships and the development of interpersonal skills and expanding emotional literacy and vocabulary in ways that reflected the multilingual nature of the classroom. The focus was on fostering in tamariki the ability to understand their peers’ different perspectives and to navigate those in positive relational ways. As one approach, a kaiako worked with tamariki to develop and use “strengths-based compliments” as a way of normalising engaging in ways that focused them on listening to or noticing the other person, and giving affirmation of their knowledge, skills, or actions. Kaiako used role play and scenarios as opportunities for tamariki to practise dealing with peers or other emotionally fraught situations. For example, one kaiako had tamariki identify challenging peer situations to deconstruct and reconstruct as a way of practising together different ways of understanding and dealing with these sorts of experiences. The tamariki worked collaboratively to plan their “part” in the role play, with the kaiako providing multiple examples of sentence starters tamariki could draw on, including use of “I statements”. The kaiako encouraged them to think about and incorporate non-verbal cues and body language. The class would go through multiple rounds playing out the scenario in different ways, so tamariki could try different approaches or “take another go”.

Another aspect of explicit teaching arose from kaiako noticing that tamariki experienced particularly challenging emotional situations with transitioning to a new school, classroom, or year level. They identified that tamariki “didn’t know how to be competent here [in a] new place and space”. This lowered tamariki feelings of competence and confidence, and the increased vulnerability led to a noticeable loss of their sense of identity for some. In response, kaiako became more explicit in establishing with tamariki their “rituals of relationships and routines” within the classroom. As one kaiako explained, this provided the opportunity to practise “in a low-stakes setting”, and then explicitly “debrief concerns, processes, and expectations” to build a shared understanding and agreement. Kaiako believed these strategies were opportunities to practise ways of being that were contextually situated to the educational setting, rather than assuming tamariki “just know what to do” when they come from so many different backgrounds and prior educational and whānau experiences.

Kaiako became more explicit in teaching the vocabulary of emotions. They recognised they had emotions that were subsumed into the unconscious patterns of interactions within the classroom. Thus, kaiako explicitly brought the language of emotion to the foreground. This included the introduction of Māori perspectives and kupu Māori for emotions to help give context to the cultural dimension of emotions and create an invitational space for tamariki to bring their home language(s) into the learning context. One kaiako used a visual of concentric circles of feelings moving from more basic language at the centre, toward more precise and nuanced vocabulary in the outer rings. Using this as a coaching tool, the kaiako would describe their own emotions linked to personal scenarios, including making explicit their metacognitive processing by describing their approach to self-regulating the emotions in that context. Tamariki could use this wheel for their reflections, helping deepen their understandings and expression of emotions. The kaiako explicitly linked expanding their English vocabulary from the wheel with support for using their other languages to express themselves.

In using these emotional literacy strategies all kaiako noted a shift in tamariki expressions of emotions, from more generalised expressions toward increasing use of a wider emotional register. Tamariki began to express specific emotions to convey feelings that underpinned anger, including hurt, belittlement, disrespect, or disappointment. The use of specific emotional vocabulary was more noticeable in peer interactions during break and lunchtimes. Kaiako noticed that increasing visibility and acceptance of emotions, that included te reo Māori, Māori values, and practices, positively influenced the development of relationships and increased use of multiple languages that supported positive sense of identity for all tamariki.

Develop an ako approach among tamariki and kaiako

We found that a spirit of ako was cultivated in the classrooms, where both kaiako and tamariki held roles as learners and teachers in developing SEL. The interchangeability of roles empowered kaiako and tamariki because it challenged and repositioned traditional roles and power dynamics of relationships within the classroom. One kaiako noticed that it provided tamariki with opportunities to say “that didn’t work, let me try it again” within a safe space. For kaiako, it provided them with the ability to reflect and learn as they encountered implementation dips and the need to “adjust, adjust, adjust” in response to enacting SEL practices. Developing knowledge around emotions and emotional states contributed to tamariki and kaiako developing trust and confidence, both within themselves and each other. Kaiako described this as supporting tamariki in “moving out of their existing comfort zones”.

Kaiako noticed improvements in interpersonal listening during interactions with and between tamariki. Tamariki became increasingly likely to address negative interactions with peers and diffused such interactions. They became “more honest and authentic” and showed enhanced understandings of “seeing things from someone else’s perspective”. One kaiako focused explicitly on developing ako among tamariki by supporting them to develop skills at rebuilding their peer relationships when they had been disrupted. Rather than “running to the rescue” or continuing to have tamariki turn to them to manage these relationships, the kaiako believed it was important for them to “take the lead”. To support them, kaiako “promot[ed] selfreflection” so they could identify if they needed to “tidy up the relationship”. Such experiences provided tamariki and kaiako with opportunities to develop their kete of socio-emotional skills that were responsive to culture, language, and identity.

The kaiako identified that they listened more to tamariki to “see things from their point of view; the story behind what happens”, reflecting their growing understanding that context matters when considering socialemotional issues. Kaiako found that sharing aspects of themselves within their SEL practices, including aspects of their whānau upbringing and lived experiences, contributed to strengthening relationships with both tamariki and colleagues within the school community. This spirit of ako was encapsulated in a vignette within which a kaiako decided to share their feelings around task anxiety and failure with tamariki. This kaiako found that tamariki became more likely “to check in with me on their progress” toward their goals. Another kaiako reflected on the power of taking an ako approach saying, it “contributed to normalising the learning pit”, resulting in “changes that were immediate, so powerful [that] everybody was empowered to give it a go”.

RESEARCH AIM 3:

Develop exemplars of practice to support the implementation of culturally and linguistically responsive SEW and SEL by schools

Externally developed SEL programmes generally require strict implementation for fidelity purposes (Green et al., 2018) and can seem a burdensome addition to an already full school curriculum. Moreover, such programmes have been critiqued for lacking responsiveness to the local educational context and existing learner needs (Reicher, 2010). Our findings illuminate how SEW/SEL can be locally developed and woven into the curriculum in ways that are responsive to culture, language, and identity of ākonga, whānau, and kaiako, without the need to use externally designed or rigidly implemented programmes. Our final aim was to draw the lessons learnt from our project to provide implementation guidance for schools. We identified three implementation principles that supported our contextually grounded approach.

Engage whānau as knowledgeable and interested partners

Student wellbeing is “enhanced when evidence-informed practices are adopted by schools in partnership with families and community” (Education Review Office, 2016, p. 4). Our findings have shown that whānau support schools in focusing on SEW/SEL and have valuable perspectives and insights that contribute to educational practices. While only 11 whānau members formally participated in the wānanga, kaiako noted that other whānau with tamariki in their classroom followed up to ask how the focus on SEL in the classroom was going. This led kaiako to be more proactive in engaging whānau in conversation on their perspectives about their tamariki SEW and SEL knowledge and skills at home and in community contexts. Kaiako found the language of noticing, “this is what I notice … what are you noticing?” elicited more engagement with whānau. It supported them in developing a sense of mutual support for tamariki learning, and they became resources for each other. Moreover, kaiako felt the non-judgemental approach of sharing noticings fostered a sense of belonging and affirmation of identity for tamariki and whānau.

Expand kaiako knowledge and skills in SEW/SEL

Teachers need to hold interpersonal skills that enable them to notice and be responsive to students in order to enact SEL (Sabol & Pianta, 2012). Intentional noticing was a means by which kaiako focused on their own and their students’ SEW within their professional practice, moving it from an unconscious to a conscious act. As they learnt more about SEW and SEL, kaiako became more aware of their assumptions and beliefs and their various emotional states within the educational space. Kaiako became more proactive in anticipating or negotiating the range of emotions that arise in practice. One kaiako called it “the prickly zone of learning”. Reflecting on their learning process, one kaiako shared it felt like they were “trying to become a different teacher”.

Anticipate teacher vulnerability and provide support

Teacher vulnerability, the willingness to share their own stories, emotions, and learning journeys, supports the development of trust and rapport with students fundamental to a relational approach in the classroom (Romney & Holland, 2020). For kaiako in our project, vulnerability was heightened as they explicitly engaged tamariki in SEL through an ako approach and incorporated new practices and ways of enacting their role. One kaiako described the journey as “scary” because “we will make mistakes”. Kaiako noted that these feelings of vulnerability related to their own and others’ assumptions around being viewed as competent, and that ingrained sense of identity around being “seen to be in control”. As one participant explained, kaiako “don’t want to be seen as vulnerable because they don’t want colleagues to see it”. Supporting each other became key for the kaiako in this project, with collegial trust being key. “Being vulnerable with each other [meant] being honest, being open [and] verbalising how to ask for help”, which enabled them to make changes in their practice.

Implications for practice

- The development of SEL practices to support the development of SEW needs to be responsive to language, culture, and identity. However, the development of such practices does not need to be restricted to the implementation of established programmes to foster either SEL or SEW.

- The development of SEL practices that reflect culture, language, and identity requires that teachers are provided with support to gain understandings around culturally grounded perspectives of SEW and related SEL knowledge and capabilities. Teachers need support to understand how these practices can be implemented within the educational context.

- SEW in tamariki is fostered through a relational approach where communication is key to relationship building. Tamariki and kaiako require support to develop related emotional literacy; emotional vocabulary, emotive language, and emotional states, including verbal and non-verbal behaviours; and supporting metacognitive and reframing skills.

- A focus on SEL practices creates vulnerability for kaiako and their wellbeing and identity. Support for SEL practices can be achieved through communities of practice that provide safe spaces.

- A focus on SEW underpinned by a holistic approach is a worthy investment for schools, including for tamariki, kaiako, and whānau. This requires school leadership to join alongside teachers in engaging with culturally and linguistically responsive SEL to foster SEW.

Conclusion

Our project responds to the call to action to develop approaches to SEL that take culture seriously, and enable the development and implementation of practices that are culturally and linguistically responsive to, and grounded in, local socio-cultural perspectives of SEW pertinent to the education context. When guided by such an educationally focused framework and aligned construct of SEL informed by Māori constructs, teachers are able to refine and adapt existing practices. With deeper understandings of SEW/ SEL, they become adept at identifying new practices to integrate into their classroom repertoires, routines, and curriculum in ways that affirm the identity, culture, and languages of their tamariki. Through the project we have illuminated how schools can be guided by key principles of practice to develop local curriculum to address SEW/SEL. Over the course of the project, it became increasingly evident that developing SEW in ākonga also required SEW to be developed in teachers, suggesting that SEL should not be focused on ākonga alone.

Acknowledgements

This project occurred over 2019–2021, during a time of great sadness, shock, uncertainty, and disruption. We extend our thanks to everyone—tamariki, whānau, and kaiako—who engaged on this journey through these times. The willingness and openness of the kaiako are a testament to their dedication to their tamariki, whānau, and communities.

Hornby High School—Simon Scott, Raewyn Davis, Marina Shehata, Terry Mitchell, and Chris McLaren. Hornby Primary School—Kate Mclachlan, Heather Matthews, and Alethea Dejong.

We wish to acknowledge Te Taumutu Rūnanga Education Committee, and their Chair Liz Brown, who supported and provided insights to guide this project.

Finally, thank you to Dr Seema Gautam (Senior Research Assistant) and Hannah Bennett (Research Assistant).

Project team

Professor Emeritus Letitia Fickel was Founding Executive Dean of the Faculty of Education, University of Canterbury. Her scholarly interest is related to teacher learning and practice for equity and social justice.

Dr Amanda Denston was Senior Research Fellow at the University of Canterbury during the project, and is now Senior Lecturer at the Institute of Education, Massey University. Her whakapapa affiliates with Waitaha, Kāti Mamoe, and Ngāi Tahu iwi. Amanda’s research interests include the relationship between literacy and psychosocial development and student wellbeing.

Dr Rachel Martin is Senior Lecturer at the College of Education, University of Otago. She affiliates with Ngāi Tahu, Waitaha, Kāti Mamoe iwi. Rachel’s research interests include culturally and linguistically sustaining Te Tiriti-based frameworks for education.

Dr Veronica O’Toole is Senior Lecturer in the Faculty of Education, University of Canterbury. Her research interests are emotions, emotional regulation, and social emotional wellbeing of teachers and students.

References

Antonovsky, A. (1987). Sense of coherence: Orientation to life questionnaire. Jossey-Bass.

Anziom, B., Strader, S., Simeon Sanou, A., & Chew, P. (2021). Without assumptions: Development of a socio-emotional learning framework that reflects community values in Cameroon. Frontiers in Public Health, 9, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.3389/ fpubh.2021.602546

Barab, S. (2006). Design-based research: A methodological toolkit for the learning scientist. In R. K. Sawyer (Ed.), The Cambridge handbook of the learning sciences (pp. 153–169). Cambridge University Press.

Barnes, T. N. (2019). Changing the landscape of social emotional learning in urban schools: What are we currently focusing on and where do we go from here? Urban Review: Issues and Ideas in Public Education, 51(4), 599–637. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11256019-00534-1

Bishop, R., Berryman, M., Cavanagh, T., & Teddy, L. (2009). Te kotahitanga: Addressing educational disparities facing Māori students in New Zealand. Teaching and Teacher Education, 25(5), 734–742. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2009.01.009

Boyd, S., Bonne, L., & Berg, M. (2017). Finding a balance—fostering student wellbeing, positive behaviour, and learning: Findings from the NZCER national survey of primary and intermediate schools 2016. New Zealand Council for Educational Research. https://www.nzcer.org.nz/system/files/National%20Survey_Wellbeing_for%20publication_0.pdf

Collaborate for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL). (2020). What is SEL? https://casel.org/what-is-sel/

Corcoran, R., Cheung, A., Kim, E., & Chen, X. (2018). Effective universal school-based social and emotional learning programs for improving academic achievement: A systematic review and meta-analysis of 50 years of research. Educational Research Review, 25, 56–72. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2017.12.001

Durie, M. (1998). Whaiora: Maori health development. Oxford University Press.

Durlak, J. A., Weissberg, R. P., Dymnicki, A. B., Taylor, R. D., & Schellinger, K. B. (2011). The impact of enhancing students’ social and emotional learning: A meta-analysis of school-based universal interventions. Child Development, 82(1), 405–432. https://doi. org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01564.x

Education Review Office. (2015a). A wellbeing for success resource for primary schools. http://www.ero.govt.nz/publications/ wellbeing-for-childrens-success-at-primary-school/

Education Review Office. (2015b). A wellbeing for success resource for secondary schools. https://www.ero.govt.nz/publications/ wellbeing-for-young-peoples-success-at-secondary-school/

Education Review Office. (2016). Wellbeing for success: A resource for schools. Stories of resilience and innovation in schools and early childhood services. http://www.ero.govt.nz/publications/wellbeing-for-success-a-resource-for-schools/

Glaser, B., & Strauss, A. L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory. Aldine.

Goodman, R. (1997). The strengths and difficulties questionnaire: A research note. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 38(5), 581–586. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.1997.tb01545.x

Green, J. H., Passarelli, R. E., Smith‐Millman, M. K., Wagers, K., Kalomiris, A. E., & Scott, M. N. (2018). A study of an adapted social– emotional learning: Small group curriculum in a school setting. Psychology in the Schools, 56(1), 109–125. http://doi.org/10.1002/ pits.22180

Macfarlane, A. H., Macfarlane, S., Graham, J., & Clarke, T. H. (2017). Social and emotional learning and indigenous ideologies in Aotearoa New Zealand: A biaxial blend. In E. Frydenberg, A. J. Martin, R. J. Collie, E. Frydenberg, A. J. Martin, & R. J. Collie (Eds.), Social and emotional learning in Australia and the Asia–Pacific: Perspectives, programs and approaches (pp. 273–289). Springer.

Macfarlane, A. H., Webber, M., Cookson-Cox, C., & McRae, H. (2014). Ka awatea: An iwi case study of Māori students’ success. Ngā Pae o te Māramatanga.

Mahuika, N., & Mahuika, R. (2020). Wānanga as a research methodology. AlterNative, 16(4), 369–377. https://doi.org/10.1177/1177180120968580

Manning, M., & Fleming, C. (2019). The complexity of measuring indigenous wellbeing. In C. Fleming & M. Manning (Eds.), Routledge handbook of indigenous wellbeing (pp. 1–2). Routledge.

Mason, J. (2001). Researching your own practice: The discipline of noticing. Routledge.

McLeod, J., & Wright, K. (2015). Inventing youth wellbeing. In J. McLeod & K. Wright (Eds.), Rethinking youth wellbeing (pp. 1–10). Springer.

Muris, P. (2001). A brief questionnaire for measuring self-efficacy in youths. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 23(3), 145–149. http://doi.org/10.1023/A:1010961119608

O’Sullivan, D., Came, H., McCreanor, T., & Kidd, J. (2021). A critical review of the Cabinet Circular on Te Tiriti o Waitangi and the Treaty of Waitangi advice to members. Ethnicities, 21(6), 1093–1112. https://doi.org/10.1177/14687968211047902

Reicher, H. (2010). Building inclusive education on social and emotional learning: Challenges and perspectives—a review. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 14(3), 213–246. http://doi.org/10.1080/13603110802504218

Rogoff, B., Coppens, A., Alcalá, L., Aceves-Azuara, I., Ruvalcaba, O., López, A., & Dayton, A. (2017). Noticing learners’ strengths through cultural research. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 12(5), 876–888. http://doi.org/10.1007/s10857-020-09464-2

Romney, A. C., & Holland, D. V. (2020). The vulnerability paradox: Strengthening trust in the classroom. Management Teaching Review, 8(1), 84-90. https://doi.org/10.1177/2379298120978362

Sabol, T., & Pianta, R. (2012) Recent trends in research on teacher–child relationships. Attachment & Human Development, 14(3), 213–231. http://doi.org/10.1080/14616734.2012.672262

Scott, K. (2012). Measuring wellbeing: Towards sustainability? Routledge.

Smith, L. T. (2012). Decolonising methodologies: Research and indigenous peoples (2nd ed.). Palgrave Macmillan.

Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1998). Basics of qualitative research: Grounded theory approaches and techniques (2nd ed.). Sage.

Taylor, R. D., Oberle, E., Durlak, J. A., & Weissberg, R. P. (2017). Promoting positive youth development through school-based social and emotional learning interventions: A meta-analysis of follow-up effects. Child Development, 88(4), 1156–1171. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12864

The Design-Based Research Collective. (2003). Design-based research: An emerging paradigm for educational inquiry. Educational Researcher, 32(1), 5–8. http://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X032001005

Zembylas, M. (2007). Emotional ecology: The intersection of emotional knowledge and pedagogical content knowledge in teaching. Teaching and Teacher Education, 23(4), 355–367. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2006.12.002

APPENDIX

2019 questionnaire data and discussion

As noted in the body of this report, descriptive statistics were discussed at research hui to support building on the tentative themes identified from wānanga. Subsequent analyses using independent-samples t-tests were performed to compare the influence of age, using educational context (primary, secondary) as a proxy, on the sense of coherence, self-efficacy, and SDQ measures. Such an analysis offers insight into possible developmental and contextual considerations of SEW that can inform teacher practices. Effect sizes utilised Cohen’s 1988 criteria of .01 (small), .06 (moderate), and .14 (large). These data are presented in Table 1 below.

Descriptive data indicated that, in 2019, groups reported scores on the Sense of Coherence measure within the average range, with primary demonstrating a mean score of 146.05 and secondary demonstrating a mean score of 126.37. The lowest scores were identified for both groups in the meaningfulness subscale, with mean scores of 45.74 (primary) and 36.19 (secondary). Data indicated that primary tamariki held more positive self-perceptions regarding their ability to cope with stressful situations than secondary tamariki. Primary-aged tamariki were better able to rationalise internal and external stimuli (Comprehensibility), manage stress within their lives (Manageability), and problem solve through stressful experiences (Manageability) than secondaryaged tamariki. Although both sets of scores fell within the average range (Primary, M = 146.05; Secondary, M = 126.37), independent t-tests indicated a significant difference between the groups (t = 3.606, p = .000) with a large effect size (‐η2 = .15).

For the self-efficacy scale, primary ākonga demonstrated an overall score within the high range (98–144) with a mean of 107.82, while secondary ākonga fell within the average range (49–97) with a mean score of 95.12. For the secondary ākonga, all subscale scores were within the medium range, with the lowest mean score identified for the emotional subscale (M = 30.66). For primary ākonga, the academic and social subscales fell within the high range, and the emotional subscale fell within the average range (M = 35.51).

For the SDQ, we found that primary tamariki perceived they held low levels of prosocial skills with mean scores significantly lower than secondary tamariki (Primary, M = 1.91; Secondary, M = 2.86; t = -1.992, p = .050; ‐η2 = .05). We also found that secondary tamariki perceived they held greater difficulties in relating with peers (Primary, M = 12.96; Secondary, M = 14.05; t = -.820, p = .415), with mean scores for both groups falling within the slightly raised range.

| 2019 | |||||||||

| Primary | Secondary | t | p | η2 | |||||

| Subscale | N | Mean | SD | N | Mean | SD | |||

| SOC-Total | 42 | 146.05 | 25.60 | 32 | 126.37 | 24.24 | 3.606 | .000** | 0.15 |

|

SOC-C

|

42 | 50.93 | 10.41 | 32 | 45.77 | 9.33 | 2.285 | .025* | 0.07 |

|

SOC-Mg

|

42 | 49.38 | 9.83 | 32 | 44.42 | 9.13 | 2.491 | .015* | 0.08 |

|

SOC-Me

|

42 | 45.74 | 9.25 | 32 | 36.19 | 7.91 | 5.221 | .000** | 0.27 |

| SDQ-Total | 42 | 12.96 | 6.28 | 32 | 14.05 | 5.25 | -.820 | .415 | 0.01 |

|

SDQ-Pro

|

42 | 1.91 | 2.13 | 32 | 2.86 | 2.52 | -1.992 | .050* | 0.05 |

|

SDQ-H

|

42 | 4.24 | 2.10 | 32 | 4.45 | 2.27 | |||

|

SDQ-C

|

42 | 1.79 | 2.13 | 32 | 2.31 | 1.62 | |||

|

SDQ-E

|

42 | 3.90 | 2.11 | 32 | 3.91 | 2.10 | |||

|

SDQ-P

|

42 | 3.05 | 1.81 | 32 | 3.91 | 1.52 | |||

| SE-Total | 42 | 107.82 | 19.84 | 32 | 95.12 | 18.21 | 3.075 | .003* | 0.12 |

|

SE-A

|

42 | 36.31 | 8.52 | 32 | 32.31 | 6.95 | 2.450 | .017* | 0.08 |

|

SE-S

|

42 | 36.00 | 6.90 | 32 | 32.16 | 8.45 | 2.239 | .028* | 0.07 |

|

SE-E

|

42 | 35.51 | 7.33 | 32 | 30.66 | 8.02 | 2.742 | .008* | 0.09 |

Note: SOC- Sense of Coherence; C- Comprehensibility, Mg- Manageability and Me- Meaningful;

SDQ- Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire, H- Hyperactivity, C- Conduct, P- Peer Problems and Pro- Prosocial; SE- Self-Efficacy; A- Academic, S- Social, and E- Emotional.

*p < .05, **p < .001.

η2 = .01(small), .06 (medium), .14 (large)