Introduction

This project explored the role of early childhood education (ECE) and pedagogical strategies in supporting a sense of belonging and identity for refugee and immigrant children and families in Aotearoa New Zealand. We used a design-based research methodology in four culturally diverse ECE settings to develop and trial theories and strategies about how ECE can deliberately encourage refugee and immigrant children to connect with their home countries, sustain their cultural identity, and simultaneously live within and contribute to Aotearoa New Zealand. We analysed the affordances of drawing, storytelling and play, and of teacher engagement with children, parents, and whānau, for constructing pathways to belonging in Aotearoa New Zealand. The research focus was on the potential of early childhood services to be sites for social justice for refugee and immigrant children and families, laying a foundation for a confident transition to a bicultural Aotearoa, additional to their own culture. Through the research, we wanted to develop practice strategies and theories of bicultural belonging and participatory democracy that can be strengthened through early childhood education.

The global refugee crisis is affecting many young children (UNCHR, 2019). Refugee families face challenges of dealing with trauma and language barriers, and with different patterns of childrearing, gender roles, and social values (Broome & Kindon, 2008; Deng & Marlowe, 2013; McMillan & Gray, 2009; Mitchell & Ouko, 2012). The population of immigrant children coming to New Zealand is also fast growing, making Aotearoa New Zealand one of the most ethnically diverse countries in the OECD. Census 2018 found that 27% of New Zealanders were born overseas (Statistics New Zealand, 2019).

The society of Aotearoa New Zealand is ethnically diverse, but responsiveness to this diversity is often not evident in the education system. For example, Guo’s (2010) doctoral study of Chinese immigrant families concluded that a shift in teachers’ beliefs and practices was required for them to respond in visible and appropriate ways to the diverse beliefs and practices they encountered in the classroom (p. 262). Chan’s (2011) literature review around immigrant families in ECE identified stereotypical and universalist views that teachers often adopt towards individuals from particular ethnic groups. Chan (2011) argued that more culturally sensitive and responsive understandings were necessary in such situations. From the Aotearoa New Zealand perspective, Ritchie and Rau (2008) depicted education as a powerful mechanism that privileges a Pākehādominated pedagogy. These examples indicate that Aotearoa New Zealand still has work to do when it comes to exploring cultural and ethnic complexity and difference, particularly when it comes to meaningfully integrating these into educational settings.

Refugee and immigrant children and families are transitioning from their home country to a new country and culture. Brooker (2014, p. 32) has described children’s transitions as “a process in which a primary task is to develop a sense of belonging, of membership, of feeling suitable in the new space”. Te Whāriki’s unique bicultural framing emphasises the bicultural foundation of Aotearoa, New Zealand and references te ao Māori— the Māori world. It implies a society that recognises Māori as tangata whenua (people of the land), and assumes a shared obligation for protecting Māori language and culture. Belonging | Mana whenua is a strand of Te Whāriki, described as:

Belonging | Children know they belong and have a sense of connection to others and the environment

Mana whenua | Children’s relationship to Papatūānuku is based on whakapapa, respect and aroha

(Ministry of Education, 2017, p. 31)

Participation is a core idea in Te Whāriki’s portrayal of belonging—children “know that they are accepted for who they are and that they can make a difference” and “whānau feel welcome and able to participate in the day-today curriculum and to curriculum decision-making” (p. 31). However, there have only recently been attempts to theorise and analyse constructs of belonging and to make connections with identity and participation. Moreover, there is little research on how belonging can be supported through ECE, especially where different cultural beliefs require negotiation. Our research addresses these issues.

Research questions

For children from refugee and immigrant backgrounds, the overarching question was:

- How can the people, places, and practices in early childhood settings support a sense of bicultural belonging to Aotearoa New Zealand, and sustain children’s connections to homelands and people?

This question was explored through the following questions and associated sub-questions:

- How do drawing, storytelling, and play provide opportunities for:

- children to sustain connections with people and experiences from their home country?

- children to develop new connections in and sense of belonging with Aotearoa New Zealand?

- How do teachers engage with children, parents, and whānau to:

- enable a two-way exchange and mutual learning about culture?

- find out more about the knowledge and skills of children themselves?

Research design

We used a sociocultural–ecological paradigm that encompasses the holistic development of children and families at multiple interrelated levels—the individual, family, community, and civil society. The theoretical understanding underpinning the study was the idea of drawing on community and family “funds of knowledge”, described by Moll et al. (1992) as “historically accumulated and culturally developed bodies of knowledge and skills essential for household or individual functioning and wellbeing” (p. 133). The approach is especially valuable in overcoming stereotypical and deficit perspectives related to refugee and immigrant children because it enables appreciation of the resources, skills, and knowledge that families possess. These frames contributed to our development of the research questions, to the data-gathering methods, and to how the project was set up as a partnership with teachers as collaborators from the start.

In order to gather a depth of information about dimensions and processes of belonging and the teaching and learning strategies to support these, two cycles of data collection and analysis were undertaken in four ECE centres that included a high percentage of refugee and/or immigrant children. The research followed an iterative process used in design-based research, which “aims to develop theories of the process of learning and the means of supporting these processes” (Penuel, 2014, p. 99). Teaching and learning strategies were developed, trialled, and evaluated by teachers and researchers. Our understandings and strategies developed over the course of the study will be published as a resource package for teachers.

Methods

ECE centres and case study families

Four ECE centres were invited to participate in the study. They were Pakuranga Baptist Kindergarten in Auckland, and Iqra Educare, Crawshaw Kindergarten, and Hillcrest Kindergarten in Hamilton. Reflective of the ethnic diversity of ECE settings in Aotearoa New Zealand, the centres differed markedly in the ethnic composition of children and families.

Within each centre, four families and their children were invited to participate as case studies. They were chosen according to the age of the children (3 years, so they could be followed over time), and because they were of differing ethnicities, had come to Aotearoa New Zealand as refugees or immigrants, and were keen to be involved. An interpreter was employed to discuss the study, carry out interviews, and translate information for one family who requested this.

Initial whole-day workshop (March 2018)

The data gathering for the project began with a whole-day workshop on 14 March 2018. This workshop was held with all centres participating in the project, with two teachers from each of the four centres and the researchers attending. In this forum, the project design and initial plans for each setting were agreed on. The university researchers presented ideas on interculturalism and ideas from kaupapa Māori on bicultural belonging (Rameka, 2018), and these were discussed. Teachers presented information about their families and communities, their “philosophy”, their understandings, and their ideas about belonging, as well as the specific teaching and learning strategies they use. We ended the workshop with each setting having participated in designing their first cycle of design-based research. With many of the teachers new to research, and with the project in its early stages, the resulting research design and data-gathering methods were similar for each setting. The teacher workshop itself was audio-recorded, with the recording being used in the analysis to connect the philosophy and values of each centre with the data collected in that setting.

Design-based research cycle one (April to September 2018)

Within each centre, data gathering included:

- Video recordings of the case study children of approximately one hour during their free play. Children wore a wireless microphone so that their language could be recorded. Researchers made these recordings.

- Video recordings of curriculum events designed by teachers. Researchers and teachers made these recordings.

- Drawing and talking with children. To gain children’s views about belonging, teachers prompted case study children to simultaneously draw pictures about important people in their family and their home experiences, and talk about their drawing. Teachers constructed their own questions to ask the children. The drawings were collected, and the narratives recorded by video or audio or written down by the teacher.

- Artefacts from home. Children were asked to bring an artefact from home that represented some connection or sense of belonging to their homeland. The case study children were specifically invited to participate in this activity, while a general invitation was made to all other children to ensure everybody had the opportunity to participate. The children had an opportunity to introduce the artefact in a group setting and talk about what it meant to them and their family. This sharing with the group was videorecorded by the researchers. Once the group setting had concluded, the children were able to use the artefact in the play setting as part of free play. This free play was videorecorded to see what the child and his/her peers’ interactions around or including the artefact might be.

- Learning stories within the case study children’s portfolios. These were analysed in relation to the strands of Te Whāriki, and their link to belonging. The learning outcomes within the updated curriculum were used as a reference, with an eye to locally constructed outcomes as well.

- Semi-structured interviews with the parents of the case study children in their family home or at the centre. Parents were asked to view selected episodes of their child’s video recording and to pick out valued learning stories in the child’s portfolio. These were used as catalysts for discussion about learning and interactions that are valued; their child’s strengths, interests and strategies as a learner; the funds of knowledge that families hold; and continuities between home and the ECE centre. A researcher, teacher, and an interpreter, where necessary, carried out the interviews.

- Focus group interviews with parents to find out about their funds of knowledge, what they see as “belonging” and narratives of their belonging in Aotearoa New Zealand, their aspirations for their child, and the practices and actions that the centre takes/could take to support these aspirations. The interview explored the values, culture, and history that families would like to be passed on. These interviews began with an invitation for participants to draw pictures related to themes of belonging in Aotearoa New Zealand and their home country. They then explained their pictures. Researchers, teachers, and an interpreter, where necessary, carried out the focus group interviews.

The relationship between the research questions and the data collection methods is summarised in Table 1, bearing in mind that all methods linked to the overall theme of belonging.

| Research questions | Data gathering method |

|---|---|

|

Video/audio recordings of the case study children, using a wireless microphone Video recordings of curriculum events designed by teachers Learning stories |

|

Video recordings of drawing and talking with children and teachers

Video recordings of curriculum events designed by teachers Learning stories |

|

Artefacts from home

Semi-structured interviews with parents Focus groups with parents |

Analysis was done with teachers from each setting (for their setting data), and by researchers in discussion with advisory group members (Margaret Carr and Bronwen Cowie).

Design-based research cycle two (November 2018 to May 2019)

Having previously provided the data from the first research cycle to each centre, the researchers met separately with teachers in each setting to discuss the previous research cycle and identify themes arising from the data. Teachers in each setting then identified their own focus for research in the second cycle. These built on the strengths teachers and researchers observed in the first research cycle related to aspects that teachers wanted to extend, and connected with one or more specific research questions.

- Iqra Educare. Role play to strengthen home, centre, and community linkages (research question 3); use of digital storytelling as a reflective tool to promote teacher pedagogical awareness on notions of belonging (including coming to belong) in Aotearoa New Zealand (research question 1).

- Pakuranga Baptist Kindergarten. Place-based education through walking and storying the land of the kindergarten context, and making comparisons and connections with homelands (research questions 1 and 3).

- Hillcrest Kindergarten. Extending storytelling through side-by-side reading with books in two languages; inviting parents to read in their home language and share stories from their own culture; and using props, drama, and puppet show in storytelling (research questions 2 and 3).

- Crawshaw Kindergarten. Support for bicultural and multicultural transitions to school that were respectful of the context for each particular child, and that established relationships across geographical boundaries (research question 1).

Most data was gathered by teachers in this phase, and included photographs, videorecordings, and portfolios. During this second phase, several meetings (2–3 hours) were held in each setting between teachers, the project leader, and another university researcher. The purpose was to discuss the main themes and points of interest emerging from the data gathered and to support the development of teacher theories and strategies.

Final workshop to plan and prepare dissemination (7 and 8 November 2019)

Our proposal for TLRI funding had outlined plans for dissemination that included presentations at conferences, writing for publication, and development of a resource package for dissemination to the wider early childhood sector that would encapsulate the theorising, pedagogical strategies, and tools used and provide a key practice value. In a 2-day workshop with teachers from each ECE setting, held 7 and 8 November 2019, we prepared the content of the teachers’ resource package. The workshop was facilitated by Andrea Soanes and Greta Dromgool, who have expertise in designing and preparing web-based resources with teachers for the Wilf Malcolm Institute of Educational Research’s Science Learning Hub. The package is a web-based resource that includes teacher and researcher interviews, teacher writing, and links to resources. It will be published on the Wilf Malcolm Institute of Educational Research, University of Waikato, website in 2020. Further publications planned at this workshop were articles for the NZCER journal Early Childhood Folio. Teachers from Iqra Educare, Pakuranga Baptist Kindergarten, and Hillcrest Kindergarten have written about aspects of their research, and their articles are highlighted in the Findings section below.

Data analysis

We used the idea of building stories of belonging in context through analysis of videotaped episodes, interview data, and documentation from the four multicultural centres. We examined pedagogical strategies and patterns over time, and contexts in which they occur in terms of the nature and affordances of those contexts. We built the stories using thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006; Creswell, 2013; Patton, 2002) to identify, analyse, and report themes within the data linked to each of our research questions.

Conversation analysis (Sacks et al., 1974) and membership categorisation analysis were undertaken by Amanda Bateman. This more detailed analysis afforded an insight into periods of time where teaching and learning experiences were promoted or hindered, and also revealed specific aspects that were significant to the participants themselves. Membership categorisation analysis was useful for detailing how children refer to their belonging in everyday conversations. In these conversations, membership to a person or group is observable through children’s use of words such as “we”, “us”, and “them”, and also by observing how they choose to gain membership with some people by interacting specifically with them. Feelings of inclusion and membership to a group are closely connected to a sense of belonging.

Ethical processes

Research ethics approval was gained from the Faculty of Education Research Ethics Committee, University of Waikato. Particular attention was paid to cultural aspects and informed consent. We worked in partnership with teachers from each centre. For example, any interviews with families were done with appropriate teaching staff and interpreters if necessary. Information sheets were translated and explained through interpreters, where appropriate, to ensure understanding. Particular care was taken to explain issues of confidentiality and anonymity for participants to enable them to make a thoroughly informed decision on whether to use their real names or pseudonyms. Participating parents were asked to give written consent for videorecording of their child; their own interview; and the gathering of learning stories, drawings, and talk of their child. Teachers explained the project to children and invited them to participate and to give their assent for videorecording and the use of their learning stories and drawings. Teachers were asked to give written consent for videorecording of curriculum episodes and their group interview and discussions, and the use of learning stories.

Selected findings

Our key findings have been derived from analysis of children’s interactions in relation to the teachers’ pedagogical practices, the ECE setting environments and resources, the engagement of families and communities, and teacher critical reflection. In combination, these can contribute to supporting a sense of bicultural belonging to Aotearoa New Zealand, and sustaining connections to homelands and people. In summary, the selected findings identified and explored here are as follows.

- Drawing and storytelling provide opportunities for fostering discussion about events, places, and people that are significant to the child, and offer a way to open the teachers’ worlds to the worlds of families.

- Digital storytelling can be a powerful means for teachers to reflect on their own lives and foster pedagogical awareness on notions of belonging.

- Orchestration of a constellation of smell, sound, sight, touch, and taste experiences that echo aspects of children’s home countries and cultures is a commonly used and often unconscious strategy that assists children to feel they belong.

- Cultural artefacts and artworks can be used intentionally to facilitate cultural discussions and understandings.

- Walking and storying the land enables children to position themselves within the cultural and natural stories of a place, know the land, and come to belong. It can also be used to explore and compare children’s homelands.

In our conclusion, we discuss theoretical framings being developed through our study.

- Whanaungatanga is discussed as an aspect of being and belonging from a Māori perspective that has relevance for migrant and refugee children and families.

- Participatory democracy as a practice and value in education is linked to the idea of a democratic ECE community as a place where all participants are able to belong and make a contribution that makes a difference for learning, wellbeing, and belonging, and where they collectively create a world.

We end with discussions of implications for practice, policy, and research.

KEY FINDING 1: Drawing and storytelling provide opportunities for fostering discussion about events, places, and people that are significant to the child, and offer a way to open the teachers’ worlds to the worlds of families.

This key finding explores how drawing and storytelling, facilitated by careful prompting by the teacher, provide opportunities for children to communicate their new connections in and sense of belonging with Aotearoa New Zealand. Teacher prompts can also help children draw and talk about, and thereby sustain, their connections with people and experiences from their home country. This finding demonstrates how readily available resources such as art supplies provide a platform for children to identify the people, places, and things that are of significance to them in Aotearoa New Zealand. Although teacher prompts have been found to encourage children to elaborate on their tellings (Bateman & Carr, 2017), the examples here involve children restricting their stories to include only the characters they have drawn. The examples demonstrate that drawing is a unique resource, not directed by the teacher, which restricts possible unintentional teacher “hijacking” (Davis & Peters, 2008). As such, the drawings act as tangible resources that facilitate talk about an abstract concept such as belonging. These findings can inform early childhood practice by enhancing teacher awareness of the affordances of drawing and telling for supporting a sense of belonging for young refugee and immigrant children.

Example 1: Olivia (OLI), a teacher at Pakuranga Baptist Kindergarten, has initiated a discussion with three children about where their families are from, and their favourite place to be in New Zealand. She facilitates the discussion by asking the children to draw pictures of their favourite places. In this interaction, we see the drawing as a tangible support for telling about important people, places, and things in New Zealand. It is initiated by the teacher as she offers the opportunity for drawing, which is taken up by the child. Through the opportunity to draw, and the child being in control of the drawing, the identification of significant people and events associated with time spent in New Zealand can be revealed. A sense of belonging can be observed here, through Ella identifying connections to important people (sister and grandparents), important places she visits with them (the park), and important things (the swing).

| 01 OLI | Ella—where are you, Ella? Which one is you? |

| 02 | (Olivia looks at Ella’s drawing.) |

| 03 ELA | This is my sister. (Looks at drawing.) |

| 05 OLI | You and your sister? This is you (points to one |

| 06 | figure) and your sister? (Points to the |

| 07 | second figure then looks up to Ella.) |

| 08 ELA | (Nods her head.) |

| 09 OLI | So, what are you doing with her? |

| 12 | ELA: Playing on the swing. |

| 13 OLI | Playing on the swing! So, who’s that here? (Points to a |

| 14 | figure on the paper.) |

| 16 ELA | That’s my grandad! |

| 17 OLI | Your grandad wants to play with you guys! |

Example 2: Here we see one of our participating children, Faeza from Iqra Educare, drawing a picture. Her teacher, Sophia, is sitting next to her and asking about the figures she is drawing. In the beginning of the interaction (lines 01–09), we see Faeza drawing and telling her teacher about the people she has drawn, and the activity she has drawn them participating in (praying). Here, both Faeza and her teacher use the drawing as an artefact with which to focus their discussion. The drawing then offers opportunity for the discussion to develop, guided by Faeza, to reveal further insight into the importance Faeza places on her family engaging in praying together during their time in New Zealand. The drawing provides a tangible resource to facilitate talk between Faeza and her teacher about her drawn figures and the activities she articulates as key to her sense of belonging in her new country.

(Note: “Allāhu” is Arabic for “God”. “Musalla” refers to prayer mats.)

FIGURE 1. Faeza introduces her drawing topic

| 01 FAEZA: | This is Faeza and my dad praying Allāhu. |

| 02 TEACHER: | Aw. On your musalla? |

| 03 FAEZA: | Yeah. |

| 04 TEACHER: | Aw |

| 05 FAEZA: | I’ll draw it. (Chooses a different colour pen.) |

| 06 TEACHER: | You pick another colour to do your musalla. |

| 07 FAEZA: | Yeah. Just my little line. (Draws a line.) |

| 08 TEACHER: | That’s your Allāhu? So, where do you stay when you |

| 09 | pray, Faeza? |

| 10 FAEZA: | I do like this. (Lifts hands to head—see Figure 2, photo on left.) |

FIGURE 2. Faeza illustrates and further elaborates on her drawing

|

|

| 11 TEACHER: | Oh, you do like this? (Copies Faeza’s gesture.) |

| 12 FAEZA: | Yeah, even my dad do it.. |

| 13 TEACHER: | Oh Dad does it as well? |

| 14 FAEZA: | Yeah. |

| 15 TEACHER: | You all pray the same? |

| 16 FAEZA: | Yeah. |

| 17 TEACHER: | And do you all pray together? |

| 18 FAEZA: | Yeah. |

| 19 TEACHER: | With the family? |

| 20 FAEZA: | Yeah. |

| 21 TEACHER: | So Mummy and Daddy and I can’t see Fayda (Faeza’s |

| 22 | sister) there. |

| 23 FAEZA: | That is my sister. (Points to picture—see Figure 2, photo on right.) |

In both examples, drawing had particular properties that enabled conceptual ideas to be portrayed “at a glance”. Through telling about the drawing, the child could express meanings that were significant to them. In this way, teachers gained insight into the child’s world.

KEY FINDING 2: Digital storytelling can be a powerful means for teachers to reflect on their own lives and foster pedagogical awareness on notions of belonging.

Storytelling was also used with teachers from Iqra Educare as a reflective tool to foster their own pedagogical awareness on notions of belonging and coming to belong in Aotearoa New Zealand. All four teachers are of different nationalities and faith. Using the free online software WeVideo (WeVideo Inc., 2020), the teachers collaborated on the various stages of planning, developing, and producing individual stories of their own lives (key people, places, values, and who they are). The stories ranged from 4 to 6 minutes. Figure 3 below shows teachers planning their digital stories. Figure 4 shows examples of finished stories.

FIGURE 3. Iqra teachers setting up and planning their digital stories

FIGURE 4. Screenshots of some of the teachers’ digital stories

|

|

Teachers played their stories to each other and to the researchers, and then at an evening for parents. In summary, the making and telling of stories was regarded as an affirmation for teachers that their own stories had been heard. Teachers linked the storytelling experience to fostering their own sense of belonging. For those who were immigrants, it helped foster their sense of coming to belong in Aotearoa New Zealand. Sophia reflected on this idea as she produced her digital story:

Because we know people who have come from their country, they have a story to tell. But who are they going to tell it to? Who will be asking them? If you hadn’t asked, I wouldn’t have told you … As an immigrant, sometimes you just bottle up your feelings; you don’t let it out. And because you feel like if you tell somebody they might understand you, they might not, they might not even bother. But now since we are doing it with a purpose, I know I have told my story, and that was my life, and I [can now] move on.

Teachers saw the potential for support staff and parents to be invited to participate in a similar process. Maria, head teacher, described how digital stories are valuable for connecting with whānau who may not be fluent in English:

It was very relevant for this centre because the written word is not that accessible for a lot of our whānau. I think seeing something like that on the screen with audio is impactful, better than something written down on a piece of paper.

Teachers considered this would be valuable for parents and children to get to know staff better and for staff to obtain insights into children’s cultural backgrounds, so they could develop more targeted belonging-based pedagogies.

Digital storytelling has potential to capture pivotal episodes for reflection and consideration of alternative practices to improve teaching (Barrett, 2005; Robin, 2008; Tendoro, 2006). Such creative, reflective methods are important to prompt and sustain alternative and novel ways for teachers to think about their profession (Gore, 2015) and expand the possibilities for teachers to represent, share, and discuss reflections on teaching (Cochran-Smith et al., 2015). In our example, through creating their own digital stories teachers came to think deeply about their own lives and notions of belonging. They opened aspects of their lives to each other and to the parent community. In turn, they realised the potential for inviting support staff and families to make and share digital stories as a way of facilitating two-way understanding.

KEY FINDING 3: Orchestration of a constellation of smell, sound, sight, touch, and taste experiences that echo aspects of children’s home countries and cultures is a commonly used and often unconscious strategy that assists children to feel they belong.

A striking theme running through all presentations held in the first workshop at the beginning of the project was the connections teachers made with smell, sound, sight, touch, and taste experiences to assist children to feel they belonged. Later, as we researched in the centres, we gathered further evidence of the centrality of sensory experiences in supporting belonging. This included experiences that were familiar to the children and made connections with their homelands, and new sensory experiences that children in Aotearoa New Zealand commonly experience. Teachers’ intentional focus went both ways. We assert that the sensory landscape of a place is a taken-for-granted and thus a largely overlooked aspect of early childhood pedagogy, worthy of direct theory and practice attention.

Data from the four centres presented at that first workshop is described below as representative of common practices and experiences that foregrounded and integrated sensory experiences from homelands and from Aotearoa New Zealand. These practices and experiences were already present in settings at the start of the project, but teachers had not always consciously identified them.

Smell and taste: Cooking foods from homelands and foods from Aotearoa New Zealand brought together senses of smell and taste. Cooking was a regular activity and not confined in a tokenistic way to special “cultural” occasions. In some settings, families were invited to cook with children using their own recipes from their home countries and cooking in traditional ways. Children tasted and smelled familiar and unfamiliar foods and made connections with each other in shared mealtimes. These mealtimes honoured cultural practices from children’s home countries and from Aotearoa New Zealand, and were occasions for discussion of practices such as fasting during Ramadan and the meaning and practice of karakia. Teachers created a welcoming environment in which food often played a part, and where families were seen to comfortably help themselves to coffee and tea.

Sight: Teachers deliberately created wall displays with images from home countries and families. Gail, the head teacher from Crawshaw Kindergarten, described the name tags created for every child. The children place their name tags on arrival each day next to their own photograph: “So, there’s their name, there’s their picture to create that sort of sense of belonging, this is their place.” All the ECE settings created a “print-saturated environment” (Wylie et al., 2006) that exposed children to the written word, and where print in English, te reo Māori, and home languages was highly visible. In our examples, the contribution to children’s learning was made meaningful by connecting home language with English and te reo Māori, and by making visible the written languages of all children.

Often teachers recognised their own limitations and need for language support. Louise, a teacher from Hillcrest Kindergarten, told of the kindergarten’s efforts to include alphabet scripts and write learning stories in home languages in relation to a child from Sri Lanka:

Mum and the child both speak Sinhala, and we had our student teacher come and help us. And she was Sri Lankan and spoke the language. And she wrote a learning story as part of her learning journey as a student. And then she translated it into their language and gave it to the parent. And this parent just looked at it and read it in her own language, and just burst into tears. It was so powerful, amazing.

Imagery: Two settings displayed atua panels created by local artists. Teachers regularly talked to children about what the atua represent, read stories, and sang waiata. Visibility was given to imagery from Aotearoa New Zealand and from families’ own countries in wall displays. Every setting displayed photographs of children and families. Such imagery provides a strong visual representation of significant cultural symbols from the new country of Aotearoa New Zealand and the children’s home countries. Atua panels are discussed further in the section Key Findings 3: Affordances of cultural artefacts and artworks.

Touch: Tactile experiences were provided through the texture of different foods, and the fabrics, wall hangings, and artefacts brought in by families.

Walking the land: Weekly walks in the local community created opportunities for children at Pakuranga Baptist Kindergarten to feel the textures of leaves, flowers, and tree bark, mud on feet, rain on the face, and so on—the landscape of their local community. For some children who come from other countries, feeling mud, earth, water, grass, and space in the outdoor environment is an unfamiliar experience. Emma’s mum remarked on how different outdoor exploring at the kindergarten was from the family’s life in Singapore. She noticed in Emma’s videorecording how much Emma was now:

… into the mud puddles … she was really excited. But I also noticed from how she has actually developed, through the different sessions of Outdoor Explorers. From the first time when she was really terrified of getting herself muddy and dirty. And after which she really—she gradually became more comfortable, stepping into the mud.

Sound: Music, songs and waiata from Aotearoa New Zealand and from home countries were heard every day: “We also invite whānau to bring songs and artefacts from their cultures and to share that with us all. … This video is a practice of us singing our waiata mihimihi, which is probably our children’s favourite song.” (Gail Megaffin, showing a video of Crawshaw Kindergarten children’s waiata practice and speaking at the initial workshop).

Multisensory experiences: These were deliberately interwoven. Teachers saw these multisensory experiences as having two-way repercussions, enriching for adults and children alike. What is new here is not that children learnt through their senses, which is well established, but that teachers intentionally developed and used sensory experiences to make interconnections with Aotearoa New Zealand and with homelands. While we researched these experiences from perspectives of teachers and families, we suggest that a next step is to explore how children themselves experience and understand belonging as a multisensory sense-making process.

KEY FINDING 4: Cultural artefacts and artworks can be used intentionally to facilitate cultural discussions and understandings,

More information about this key finding is provided in two articles (Treweek et al., 2020; Sammons et al., 2020) written by teacher researchers from Hillcrest Kindergarten and Iqra Educare respectively (see reference list for full details).

Cultural artefacts: Artefacts and the stories told about them were found to be a powerful way of evoking memories and finding out what is significant to children and families, and why. These methods helped build relationships among children and the adult community (teachers, families, and community members), through finding shared interests and points of connection. Artefacts and their accompanying stories facilitated connections between home/community and the ECE setting. These connections allowed artefacts to work as a pedagogical tool, where invitations to share, the bringing of artefacts, and the telling of stories created a sense of belonging.

Roswell (2011) has found that artefacts and storytelling, as a research tool, enable access to “information that might not be possible through observation, document analysis, even interviews” (p. 332).

Treweek et al. (2020) have written of Hillcrest Kindergarten’s intentional use of artefacts through the project as a strategy for encouraging belonging. Sammons et al. (2020), from Iqra Educare, have described how a Somali grandmother regularly brought cultural artefacts to share with teachers and children. Here are two examples from these settings.

At Hillcrest Kindergarten, Nguyen brought a red Vietnamese flag with a white star in the centre, a map of Vietnam drawn by her father and with her hometown pinpointed (the map was rolled and tied with a white ribbon), and a traditional Vietnamese dress, including head dress, which pictured a family on the front. She described the figures on the dress as being mum, dad, baby, grandma, and grandad (see Figure 5). Many children were curious about the items and wanted to know more. Jo came to the front of the mat, sat beside

Nguyen, and said “Nguyen is my best friend.” Amelia, another child, asked, “Where did you get the dress from?” Nguyen answered, “On holiday.” Nguyen’s mother was impressed at Nguyen’s confidence in showing her treasures to her classmates: “She quite confident, even though she didn’t know much words to say, but she quite confident to get in front of the classmate and say something about her treasure box.” Later conversations between Nguyen and her peers made references to family connections and experiences from their homes.

FIGURE 5. Nguyen sharing her traditional Vietnamese dress

At Iqra Educare, the grandmother of Somali twins Sa’ad and Sundus regularly comes to the centre to share cultural artefacts from Somalia with children and teachers (see Figure 6). She wants the Somalian culture to be visible through the artefacts and she wants to broaden understanding, for all children, of Somalian culture:

I like to help the teachers when I come here. And I bring in some cultural things like drum[s], like camel picture. I like to share [with] teachers and children, our culture, my culture. That’s why I bring that items … And I help them [the centre children]. And I teach some of our culture. Yes, explain it. Even [for] other students, not only my grandchildren. If they want, I explain it. I teach them the Somali flag, and song, and other song. I teach them. But always they like it.

FIGURE 6. Cultural artefacts from Somalia

In a joint interview, the twins’ mother and grandmother spoke of how sharing these artefacts—showing how they worked in their culture, what they do and why they do it—fostered their own and the twins’ attachment and belonging to this new environment. The confidence of this whānau and the twins grew and supported the twins’ settling into the centre, from being shy initially to becoming more confident over time.

Artworks: Artworks can depict cultural stories and act as a catalyst for understanding. At Crawshaw Kindergarten, the kindergarten pou, created by a local artist, are strategically placed around the kindergarten playground. They represent Ranginui (sky father) and Papatūānuku (earth mother) and their children, the atua of the different domains. Teachers regularly talk to the children about the pou and what they represent. They also use a range of resources and practices to inform children about the atua. These include books that explain the domains of the atua and their importance to the world. Children are also encouraged to represent their ideas and perspectives about the pou through artwork, waiata, and discussions, and through making links with other artworks including the large mural outside.

Aspects that enhance children’s sense of bicultural belonging include the following.

- Children are able to develop whanaungatanga te Ao wairua—connectedness to the spiritual world, through connecting with ngā atua and explaining why caring for these aspects is important: for example, caring for Tane Mahuta, the atua of the forest, plants, animals. They are able to express the legends associated with ngā atua. The pou allow children to physically connect with representations of the atua (the spiritual), and what they represent.

- Children are able to develop whanaungatanga ki te whenua—connectedness with whenua and place, through connecting pou with the whenua—Papatūānuku and ngā atua. Children understand the stories of the atua, and their connections to the land. Children are then able to develop understandings and relationships with the land, sea, forests, food, earth, and sky around them.

- Children develop whanaungatanga ki te taiao—connectedness with the natural world, through learning the stories of the pou. Children are able to recite and represent these stories through art and song. These connections enhance their sense of knowing, being, and belonging, as they participate in activities that express the importance of ngā atua.

KEY FINDING 5: Walking and storying the land enables children to position themselves within the cultural and natural stories of a place, know the land, and come to belong. It can also be used to explore and compare children’s homelands.

More information about this key finding is provided in an article written by teacher researchers from Pakuranga Baptist Kindergarten (Lees & Ng, 2020).

Walking and storying the land has been embedded in indigenous ways of knowing for generations (Durie, 2004; Penetito, 2001, 2009). Durie (2004, p. 4) argues that “unity with the land” is a defining element of indigeneity, premised on “a long-standing relationship with land, forests, waterways, oceans and the air”. These features come together in place-based education, which aims to:

… develop in learners a love of their environment, of the place where they are living, of its social history, of the bio-diversity that exists there, and of the way people have responded and continue to respond to the natural and social environments. (Penetito, 2009, p. 16).

Penetito discusses the appeal of place-based education for children now and in the future as the blending of “science with imagination, technology with craft, and the secular with the magical” (p. 5). Likewise, Park (1996) used a blending metaphor when he wrote of coming to know the landscapes of Aotearoa New Zealand’s coastal plains through reading these landscapes, which he likened to “collage, interweaving the patterns of ecology and the fragments of history with footprints of the personal journey” (p. 16).

Walking and storying the land of Aotearoa New Zealand and the land of the home country of immigrant and refugee families is a powerful way to come to belong. Influenced by ideas from Wally Penetito, the Pakuranga Baptist Kindergarten teaching team looked at ways that place-based education could affirm children’s identity, enabling them to position themselves within the local environment and make connections to their places of birth, as well as to their new home in Aotearoa New Zealand. At this kindergarten, walking the land happens every week. Whatever the weather, two groups of the same ten children, called the “outdoor explorers”, are taken on a 1.5-hour walk under the road bridge and around the tidal estuary of Tamaki, or in another direction through the park to the secret garden, past backyards where children chat to neighbours over fences, to climb a tree and have a picnic. Jacqui Lees, the head teacher, described the walking excursions as “knowing the land through your body, and through your feet, and if you walk it you have a sense of connection to it and a relationship with it”. When you are involved in regularly walking in this way, not as a rare occurrence, you learn to read the landscape. These walking endeavours are always part of larger projects in the kindergarten that are sustained over time. They involve children in storytelling; learning about Māori history; taking responsibility for cleaning and planting; observation; scientific exploration of changes of seasons, patterns of tide, and growth; art; mathematics; and so on. They also help children develop relationships, as with 3-year-old Emma whose mum said, “When she started outdoor explorers she would ask to hold people’s hands. Now she will offer to hold other people’s hands.”

As part of our research project, the outdoor explorers went further afield to explore the neighbouring volcanoes of Ohuiarangi and Maungarei. Teachers Jacqui Lees and Olivia Ng wrote about this work in their Early Childhood Folio article “Whenuatanga—Our places in the world” (Lees & Ng, 2020). Finding out about and visiting the local volcanoes of Ohuiarangi and Maungarei was a deliberate strategy to learn more about the local community. Wanting to know more about local history, teachers followed Penetito’s advice:

The Maori knowledge that gets into the learning institutions should be a selection from local whānau/ hapu/iwi sources … local whānau/hapu/iwi must decide what should be available and how it should be made accessible. (Penetito, 2001, p. 24)

Teachers built relationships with Tautoko Witika, a local kaumātua connected to Ngāti Whatua, Ngāi Tai ki Tāmaki, and Tainui, who told them stories of the area for retelling to children and families. In this way, teachers and children increased their knowledge of the maunga close to the kindergarten and became more respectful of it. “How we inhabit a place can be the most telling expression of how we sense its worth, our intention for it, and our connection with it” (Park, 1996, p. 31).

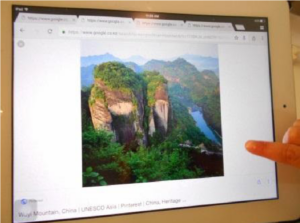

FIGURE 7. Children making connections between Maungarei/Mount Wellington and Wuyi Mountain in China

|

|

Teachers purposely made connections with mountains from children’s home countries that were significant to children’s families (see Figure 7). They found out about these mountains by inviting families to tell stories, bring photographs, and recollect memories. This process was facilitated by a teacher who spoke the child’s home language and communicated in a deep and meaningful way with families. Teachers worked with children using the internet to find out about and explore these mountains and surrounding landscapes, and encouraged children to express their ideas through art. They used deliberate questioning strategies to encourage children to think and theorise, including “wondering questions” such as why mountains have names, and whether mountains have stories to tell. Spinoffs included teachers themselves finding out more about the funds of knowledge residing in families and building closer connections with these families. They enabled children to sustain connections with people and experiences from their home country.

Penetito has noted that indigenous peoples already have a well-rehearsed and historical affinity to place-based education (PBE). However, “focusing on PBE is educationally and culturally significant for all students” (p. 24). Our research findings demonstrate the very real benefits from walking and storying the land for refugee and immigrant families.

Aspects that enhance children’s sense of bicultural belonging include:

- Children developing whanaungatanga ki te whenua—connectedness with whenua or place, through connecting and building relationships with the whenua, Papatūānuku—the earth mother. This involves developing a physical and spiritual relationship with the land, a sense of unity with and love of the land. This entails a responsibility to respect and care for the land and the natural environment.

- Children developing whanaungatanga ki te tangata—connectedness with people, including a local kaumatua, who tells the stories and history of the land, the people, and the local community. In this way children learn the connections to tangata whenua, iwi, and hāpū, the land, mountains, and the environment.

- Children developing whanaungatanga ki te taia, te aotūroa—connectedness with the environment and natural world, through learning the stories of the people and being able to retell them to children and families, learning about the of the biodiversity that exists there, and how to engage with the natural and social environments.

Conclusion

This conclusion discusses theoretical frames that we are developing over the course of the study that have relevance in explaining two-way processes for refugee and migrant families of coming to belong in Aotearoa New Zealand and sustaining belonging in homelands. It ends with final words and recommendations for research, policy, and practice.

Whanaungatanga as an aspect of being and belonging

Contemporary ideas of belonging and being stress increasingly diverse and complex positionings that require negotiation of different assumptions, behaviours, values, beliefs, and contexts. These include ideas about how worlds are constituted and ways of acting, being, and belonging within those worlds. Key to developing a sense of belonging for migrant and refugee families and children in Aotearoa New Zealand is whanaungatanga (kinship). Whanaungatanga involves the establishment of whānau (family) connections and acknowledgement of the responsibilities and obligations that whānau members have to each other. It also includes philosophies and practices that strengthen the physical and spiritual harmony and wellbeing of the group. Aspects of whanaungatanga that have relevance for migrant and refugee children and families include the following.

- Whanaungatanga ki te tangata (connectedness with people) relates to the close relationships developed and maintained between members of the whānau. It connects the individual to kin groups, providing a sense of belonging while strengthening the kin group as a whole.

- Whanaungatanga ki te whenua (connectedness with whenua or place) refers to both physical and spiritual relationships with the land. The physical relationship includes physical and geographical connectedness to important natural features such as a mountain, a river, or a place. The spiritual relationship involves the development of a deep bond to mountains, rivers, and Papatūānuku—the earth mother.

- Whanaungatanga ki te taiao (connectedness with the natural world) is about relationships to the natural world and acknowledging the natural order of the universe, including the living and the non-living. It is perceived in terms of the connectedness of all living things, rather than ownership or control of the natural world.

- Whanaungatanga ki te reo (connectedness with language) relates to the importance of language as both a communication tool and a transmitter of values and beliefs. Language is also a means of transmitting customs, valued beliefs, knowledge, and skills from one person to the next and from one generation to the next. It reflects the cultural environment and ways of viewing the world. It is therefore an important source of power and a vehicle for expressing identity.

- Whanaungatanga ki te ao wairua (connectedness with the spiritual world) relates to the relationship between the physical and the spiritual, and the wholeness of life. It is a perspective of the world where all things have a spiritual as well as physical body, including the earth, birds, and animals, and where maintaining balance is critical to the overall wellbeing of all.

Democracy

The ECE settings in our study were places where immigrant families and children could experience living in a democratic community. A democratic ECE community might be a place where all participants are able to belong and make a contribution that makes a difference for learning and wellbeing, and where they collectively create a world of possibilities (Bruner, 1998). Democracy is “a way of life controlled by a working faith in the possibilities of human nature … [and] faith in the capacity of human beings for intelligent judgment and action if proper conditions are furnished” (Dewey, 1976, p. 225). Moss (2014, p, 2) describes democracy as “a way of relating, an ethical, political and educational relationship that can and should pervade all aspects of life”. This concept of democracy implies maximising opportunities for sharing, exchanging, and negotiating perspectives and opinions. Contribution and empowerment, in the sense of personal control and influence, was a theme running through our interviews with all families who took up opportunities to contribute their skills and knowledge in the ECE setting, knowing these were welcomed.

Te Whāriki writes of the principle Empowerment/Whakamana, “This principle means that every child will experience an empowering curriculum that recognises and enhances their mana and supports them to enhance the mana of others” (Ministry of Education, 2017, p. 18). Wally Penetito (2009, p. 23) notes the “creative tension” between individualism and collectivism and that neither can be taken for granted: “Where one’s mana ake (unique individualism) is encouraged to develop, rangatiratanga (self-determination) for the collective identity is also facilitated.” They fully develop with each other in a “relational totality”. Important to our project, young children were conceptualised as “social actors, shaping as well as shaped by their circumstances” (James et al., 1998, p. 6). Children’s agency was enhanced through deliberate strategies by teachers to open up spaces and ways for children to explore what was significant and meaningful for them and their families, such as in the drawing episodes where children’s choices and explanations were not hijacked by teachers’ interpretations. Open-ended questions, such as Jacqui’s “wondering questions”, encouraged children to think for themselves. In the group sessions, where children shared their artefacts from home, each child had opportunity to contribute and was affirmed by the attentive interest displayed by other children and teachers. Similarly, finding out about mountains from children’s home countries was a tangible demonstration that the child’s homelands and family funds of knowledge were valued. In these ways, children’s confidence and sense of identity were enhanced and their understandings and appreciation of each other’s diverse home experiences and cultures developed. Thus, the curriculum could be seen as a source of hope in helping children to practise democracy (Broström, 2013).

While there may be agreement about values and goals in a democratic society, democracy in education leaves open space for experimentation, creativity, and new thinking (Moss, 2014). The teachers in our study were democratic professionals, willing to research, analyse, make judgements, and experiment. The willingness of teachers to act as teacher researchers and open their practice to collaborative analysis and discussion through this project offered a basis for democratic professionalism.

The values embedded in a concept of ECE as a democratic community represent a shift from economic and instrumental values that have been dominant in the ECE sector (e.g., Mitchell, 2019; Moss, 2019) and are present in the schooling sector (Thrupp et al., 2018). Democracy conveys a wider view of the purposes of education. Children are conceptualised as citizens and contributors, with rights and responsibilities, integrally embedded within family and whānau, and within conditions of childhood. Our concept of democracy incorporates an aim for children to develop as “citizens of the world” located within Aotearoa New Zealand as a country that aspires to uphold rights to indigeneity, and to be a bicultural society. In a culturally diverse society where immigrant and refugee families coming to Aotearoa New Zealand hold diverse beliefs about education and childrearing, our questions of bicultural belonging in Aotearoa New Zealand, and belonging in homelands are especially relevant.

Implications for practice, policy and research

Drawing from our key findings, we found the following themes.

All settings had a commitment to Te Tiriti o Waitangi and a bicultural curriculum, and were on different places in their pathways towards this aim. The framework of whanaungatanga as an aspect of being and belonging offers signposts for ECE settings as they work with immigrant and refugee families towards bicultural belonging.

Implications for practice

- All settings had a permeable curriculum, open to contribution from children, families, and community. Teachers acted as facilitators of participatory democracy through recognising and inviting families and children to contribute their “funds of knowledge” within curriculum. In this way, teachers became better informed about the sociocultural backgrounds of their families, and were able to use their understanding in their practice. Families from homes that maintained their cultural traditions and home language, and were open to sharing them, were a valuable resource for teachers and children. Teachers created a setting that was welcoming and that valued family contributions.

- Pedagogical strategies that facilitated participatory democracy and enabled contribution of funds of knowledge were trialled in this study.

-

- The use of drawing and storytelling around people and places that were significant to children opened a window on children’s feelings and understandings of belonging. The strategy of drawing and storytelling with children is used frequently within early childhood. Of particular interest here is the extended nature of these learning sequences, where the work is child-driven, with the child taking the position of expert as they explain about the world from their unique point of view. Expert, non-interrogative discussion with a teacher and peer group also provides opportunities for a rich, complex unpacking of ideas, and also for others in the group to be exposed to different ways of being and belonging.

- Invitations for families and children to bring artefacts from home for discussion and sharing with the ECE community created connections and understanding, and enabled integrated action between homes and ECE. Through this, belonging was supported for children and for their families. These invitations were more than tokenistic, and provided opportunities for genuine, valued contributions from children and families.

- Walking and storying the land in the community of the ECE setting, and comparing with homelands, offered affordances and possibilities for building connections between the place families were living in now, and places back home that were significant to each family. Connection with the land through shared experiences also provided opportunities for children, families, and teachers to connect with each other and with the local community. All of these daily practices supported learning across the outcomes of Te Whāriki, and were particularly relevant to enhancing belonging and identity.

- One of the most significant aspects of teachers’ work in this project was their willingness to learn and to try out new things. Digital storytelling was one method that enabled teachers to reflect on their identities as teachers and their notions of belonging and coming to belong in Aotearoa New Zealand. It was also a powerful mechanism for sharing their stories with family and community, and shifting to a more balanced relationship between teachers and families.

Implications for policy

Some key messages for policy emerge from this work. There is a need for teachers to “weave together the principles and strands [of Te Whāriki] in collaboration with children, parents, whānau and community to create a local curriculum for their setting” (Ministry of Education, 2017, p. 10). Our study shows that teachers are better able to do this when they are open to finding out and inviting the contributions of community, families, and children. Teachers can be supported through teacher education, professional development, and research partnerships to think and act critically with reference to family funds of knowledge, children, and society, and to experiment with teaching and learning practices in creating their local curriculum and a fairer world. Giroux (2020) writes of critical pedagogy:

I believe it is crucial for educators not only to connect classroom knowledge to the experiences, histories, and resources that students bring to the classroom but also to link such knowledge to the goal of furthering their capacities to be critical agents who are responsive to moral and political problems of their time and recognize the importance of organized collective struggle. (p. 5)

This is demanding emotional and intellectual work. One policy challenge is how to offer opportunities and access to resources for all teachers to develop as informed, critical professionals. The importance of a sociocultural curriculum framework that provides such a platform for centre-specific pedagogical practices that meet the needs of all participants is crucial here. Our research findings demonstrate how belonging can be and is enacted in everyday interactions in similar and different ways in each early childhood setting working under the guidance of Te Whāriki. Our hope is that these findings will offer guidance to more early childhood settings, informing future practices that facilitate bicultural belonging in Aotearoa and belonging in home countries of immigrant and refugee children and families.

Implications for research

In further research over the next year with refugee families in early childhood education, we plan to trial and refine our theoretical frameworks. Additional research could also address teacher assumptions about participatory democracy and about belonging.

Research team

Linda Mitchell, Amanda Bateman, Raella Kahuroa, Elaine Khoo, and Lesley Rameka (The University of Waikato)

Advisors:

Margaret Carr and Bronwen Cowie (The University of Waikato)

Teacher researchers:

Gail Megaffin (Crawshaw Kindergarten)

Amanda Cloke, Louise Treweek, Christine McKean, Rajam Walter, and Vicki Huang (Hillcrest Kindergarten)

Maria Sammons, Sophia Ali, Leena Noorzai, and Melanie Glover (Iqra Educare)

Jacqui Lees, Olivia Ng, Nilma Abeyratne, Andrea Du, and Terina Johns (Pakuranga Baptist Kindergarten)

Some of the TLRI team members: Dr Elaine Khoo, Dr Lesley Rameka, Professor Linda Mitchell, Raella Kahuroa, Professor Bronwen Cowie

References

Barrett, H. (2005). Digital storytelling research design. https://electronicportfolios.com/digistory/ResearchDesign.pdf

Bateman, A., & Carr, M. (2017). Pursuing a telling: Managing a multi-unit turn in children’s storytelling. In A.

Bateman & A. Church (Eds.), Children and knowledge: Studies in conversation analysis (pp. 91–110). Springer.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101.

Brooker, L. (2014). Making this my space: Infants’ and toddlers’ use of resources to make a day care setting their own. In J. Sumsion & L. J. Harrison (Eds.), Lived spaces of infant–toddler education and care (pp. 29–42). Springer.

Broome, A., & Kindon, S. (2008). New kiwis, diverse families. Migrant and former refugee families talk about their early childhood care and education needs. Families Commission.

Broström, S. (2013). Understanding Te Whāriki from a Danish perspective. In J. Nuttall (Ed.), Weaving Te Whāriki: Aotearoa New Zealand’s early childhood curriculum document in theory and practice (2nd ed., pp. 239–257). NZCER.

Bruner, J. (1998). Each place has its own spirit and its own aspirations. RE Child, 3(January), 6.

Chan, A. (2011). Critical multiculturalism: Supporting early childhood teachers to work with diverse immigrant families. International Research in Early Childhood Education, 2(1), 63–75. http://hdl.handle.net/10652/2249

Cochran-Smith, M., Villegas, A. M., Abrams, L., Chavez-Moreno, L., Mills, T., & Stern, R. (2015). Critiquing teacher preparation research: An overview of the field, part II. Journal of Teacher Education, 66(2), 109–121. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487114558268

Creswell, J. W. (2013). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches. Sage.

Davis, K., & Peters, S. (2008). Moments of wonder, everyday events: How are young children theorising and making sense of their world? NZCER.

Deng, S. A., & Marlowe, J. M. (2013). Refugee resettlement and parenting in a different context. Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies, 11(4), 416–430. https://doi.org/10.1080/15562948.2013.793441

Dewey, J. (1976). Creative democracy: The task before us. In J. Boydston (Ed.), John Dewey: The later works, 1925–1953, volume 14 (pp. 224–230). Southern Illinois University Press. (Original work published 1939.)

Durie, M. (2004). Exploring the interface between science and indigenous knowledge. Paper presented at the 5th APEC Research and Development Leaders Forum. Capturing value from science. www.researchgate.net/publication/253919807.

Giroux, H. (2020). On critical pedagogy (2nd ed.). Bloomsbury Academic.

Gore, J. M. (2015). Effective and reflective teaching practice. In N. Weatherby-Fell (Ed.), Learning to teach in the secondary school (pp. 68–85). Cambridge University Press.

Guo, K. (2010). Chinese immigrant children in New Zealand early childhood centres [Doctoral dissertation, Victoria University of Wellington].https://core.ac.uk/reader/41339035

James, A., Jenks, C., & Prout, A. (1998). Theorizing childhood. Polity Press.

Lees, J., & Ng, O. (2020). Whenuatanga—Our places in the world. Early Childhood Folio, 24(1), 21–25.

McMillan, N., & Gray, A. (2009). Long-term resettlement of refugees: An annotated bibliography of New Zealand and international literature (Quota Refugees Ten Years on Series). https://web.archive.org/web/20150125125849/http://www.dol.govt.nz/publications/ research/abltsr/abltsr.pdf

Ministry of Education. (2017). Te whāriki. He whāriki mātauranga mō ngā mokopuna o Aotearoa. Early childhood curriculum. Author.

Mitchell, L. (2019). Turning the tide on private profit-focused provision in early childhood education. New Zealand Annual Review of Education, 24, 78–91. https://doi.org/10.26686/nzaroe.v24i0.6330

Mitchell, L., & Ouko, A. (2012). Experiences of Congolese refugee parents in New Zealand: Challenges and possibilities for early childhood provision. Australasian Journal of Early Childhood, 37(1), 99–107. https://doi.org/10.1177/183693911203700112

Moll, L., Amanti, C., Neff, D., & Gonzalez, N. (1992). Funds of knowledge for teaching: Using a qualitative approach to connect homes and classrooms. Theory into Practice, 31(2), 132–141.

Moss, P. (2014). Transformative change and real utopias in early childhood education. A story of democracy, experimentation and potentiality. Routledge.

Park, G. (1996). Ngā Uruora: The groves of life: Ecology and history in a New Zealand landscape. Victoria University Press.

Patton, M. Q. (2002). Qualitative research and evaluation methods. Sage.

Penetito, W. (2001). If only we knew … Contextualising Māori knowledge. In B. Webber & L. Mitchell (Eds.), Early childhood education for a democratic society. Conference proceedings October 2001 (pp. 17–25). New Zealand Council for Educational Research. http://www.nzcer.org.nz/system/files/ece-democratic-society.pdf

Penetito, W. (2009). Place-based education: Catering for curriculum, culture and community. The New Zealand Annual Review of Education, 18, 5–29. https://doi.org/10.26686/nzaroe.v0i18.1544

Penuel, W. R. (2014). Emerging forms of formative intervention research in education. Mind, Culture, and Activity, 21(2), 97–117. https://doi.org/10.1080/10749039.2014.884137

Rameka, L. (2018). A Māori perspective of being and belonging. Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood, 19(4), 367–378. https://doiorg/10.1177/1463949118808099

Ritchie, J., & Rau, C. (2008). Whakawhanaungatanga—Partnerships in bicultural development in early childhood care and education. http://www.tlri.org.nz/tlri-research/research-completed/ece-sector/whakawhanaungatanga%E2%80%94-partnerships-biculturaldevelopment

Robin, B. R. (2008). Digital storytelling: A powerful technology tool for the 21st century classroom. Theory Into Practice, 47(3), 220–228. https://doi.org/10.1080/00405840802153916

Roswell, J. (2011). Carrying my family with me: Artifacts as emic perspectives. Qualitative Research, 11(3), 331–346. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794111399841

Sacks, H., Schegloff, E. A., & Jefferson, G. (1974). A simplest systematics for the organization of turn-taking for conversation. Language, 50(4), 696–735.

Sammons, M., Ali, S., Noorzai, L., Glover, M., & Khoo, E. (2020). Fostering belonging through cultural connections: Perspectives from parents. Early Childhood Folio, 24(1), 31–36.

Statistics New Zealand. (2019). New Zealand as a village of 100 people: Our population. https://www.stats.govt.nz/infographics/newzealand-as-a-village-of-100-people-2018-census-data

Tendoro, A. (2006). Facing versions of the self: The effects of digital storytelling on English education. Contemporary issues in Technology and Teacher Education, 6(2), 174–194. https://citejournal.org/volume-6/issue-2-06/english-language-arts/facing-versionsof-the-self-the-effects-of-digital-storytelling-on-english-education

Thrupp, M., with Lingard, B., Maguire, M., & Hursh, D. (2018). The search for better educational standards: A cautionary tale. Springer. Treweek, L., Cloke, A., McKean, C., Walter, R., & Huang, V. (2020). Treasure boxes: A strategy for encouraging belonging. Early Childhood Folio, 24(1), 26–30.

UNCHR. (2019). Global trends. Forced displacement in 2018. https://www.unhcr.org/5d08d7ee7.pdf

WeVideo Inc. (2020). The online video editor for all of us. https://www.wevideo.com/

Wylie, C., Hodgen, E., Ferral, H., & Thompson, J. (2006). Contributions of early childhood education to age-14 performance: Evidence from the Competent Children, Competent Learners project. Ministry of Education.https://www.educationcounts.govt.nz/publications/ECE/2567/5979