Our study highlights how careful attention to, reflection on, and critical engagement with the dialogues of 2-year-olds in preschool ‘mixed-age’ settings can help teachers work more effectively with these learners.

The teachers in our study carried out in-depth coding of, and reflection on, comprehensive video footage of dialogues involving 2-year-olds in two preschool settings over 2 years. In-depth analysis of the video footage enabled teachers to see 2-year-olds as more competent and complex learners than they had previously realised. Teachers also saw the important role that older peers played in the 2-year-olds’ learning.

Our findings provide insights into how teachers can adjust their own dialogues to encourage 2-year-olds to become agentic learners alongside their older preschool peers.

Teachers in this project made significant shifts in their pedagogy, practice, and policy as a consequence of the discoveries they made through analysing the video footage of dialogues. They came to appreciate the multiple opportunities that exist for 2-year-olds to be leaders of their own learning in the preschool environment. These findings are important for teachers who work with 2-year-olds in mixed-age settings because they highlight previously overlooked, trivialised, or ignored dialogues as a central source of younger learners’ agency, and provide new ways of engaging with these dialogues effectively. These discoveries challenge teachers to view 2-year-olds as unique personalities and fully contributing members of the preschool learning community. The discoveries about dialogue should inform pedagogy, assessment, and the kinds of genre that are granted legitimacy in the preschool.

Introductory statement

During 2017 and 2018 researchers worked with 10 teachers in two early childhood education settings[1] that cater for 2-year-olds alongside their 3 and 4-year-old peers. Their central quest was to better understand the potential of dialogues to shape and orient learning, through generating and analysing video footage of 2-yearolds’ dialogues. This analysis generated significant pedagogical insights into the kind of dialogues that occur for 2-year-olds with people, places, and things, and the significance of these for learning. Re-visioning dialogue as learning meant that 2-year-olds were more appropriately “noticed, recognised, and responded to” through more inclusive, age-responsive pedagogies that impacted on all learners in the preschool.

Throughout this report several terms are employed that may be unfamiliar to the reader. These are based on dialogic approaches (dialogism). Predominant, traditional preschool pedagogies typically view dialogues with very young children as opportunities for the adult to provide a synthesis of meaning. Dialogic approaches provide a means of recognising dialogues’ potential for 2-year-olds’ learning beyond these traditional views. Dialogic approaches enabled teachers in the project to notice forms of language use that far exceeded verbal communication or adult agendas for learning. Teachers’ recognition of the legitimacy and potential of these alternative interpretations of dialogues led to significant pedagogical adjustment. For this reason this report does not shy away from using these terms throughout. Appendices 1 and 2 offer definitions and may be a useful reference source for readers, alongside the descriptions that are offered throughout the report itself.

The report is further supplemented by a video resource, which breathes life into the dialogues that are explored. Video examples and teachers’ narratives as they interrogate their pedagogies in relation to 2-yearolds’ dialogues supplement the conclusions presented here: see http://www.waikato.ac.nz/age-responsive/

Introducing the study

This study took place in 2017 and 2018 in Tauranga, New Zealand. The preschool contexts comprised one kindergarten and one Education and Care service in Tauranga, over 50 children, and 10 teachers. Video recording occurred over 6 days (2 days per setting in 2017 and 1 day per setting in 2018). The focus was on the different dialogues—as pedagogical interactions—involving 2-year-olds in mixed-age early childhood education (ECE) settings that are traditionally oriented to preschool (3- to 4-year-olds). Historically, kindergartens[2] or “preschools” have provided ECE environments for 3- to 4-year-olds in sessional models of delivery. This pedagogical approach was traditionally steeped in Piagetian discourse that asserted age-specific approaches to learning and an emphasis on activities. Combined with a strong push to gain status within the wider education sector, narrow interpretations of pedagogy perpetuated a discourse that positioned the preschool as a learning environment that was not suitable for 2-year-olds—even though the New Zealand early childhood curriculum, Te Whāriki, asserts their status as learners alongside their older peers.

In New Zealand ECE, 2- year-olds (as opposed to birth to 1-year-olds) are covered by the same ratio criteria as their older peers (Ministry of Education, 2008). This conveys a message that 2-year-olds’ educational needs are no different to their older peers. At the same time, 2-year-olds are excluded from the “20 Hours ECE” funding allocations, suggesting that their educational needs are less of a priority than those of 3–4-year-olds. Regardless, the rates of 2-year-old attendance in ECE continue to increase (White, Ranger, & Peter, 2016; Morton et al., 2014). The proportion of all New Zealand 2-year-olds attending early childhood education services in 2017 was 70%—compared to 60% in 2012 (Ministry of Education, 2018). The conflicting discourses that arise—one asserting that 2-year-olds do not need to be in educational spaces with their older “preschool” peers, and the other suggesting that 2-year-olds warrant the same degree of pedagogical attention as their older “preschool” peers—illuminate the impact of extant policy and attitudes on teachers’ pedagogical practice. Such unresolved tensions present a paradox concerning the educational status of those 2-year-olds now located within preschool settings that are traditionally oriented to older children. To date, little pedagogical attention has been directed to this specific age group or to this preschool context comprised of mostly older peers. This study set out to address this gap.

Why dialogues about dialogues?

While previous New Zealand research has explored teacher perceptions and beliefs about the presence of 2-year-olds in kindergarten (Duncan et al., 2006), it has not explicitly taken into account the centrality of dialogue to pedagogy for this age group, and what this dialogue might “look like”. When we use the term ‘dialogue’ from a dialogic standpoint we mean all forms of language communication—verbal and non-verbal—that occur ‘inbetween’ subjectivities. Dialogues are identified as important for 2-year-olds’ learning because they:

- allow for the expression of multiple ideas and perspectives (Chalmers, 2016; Papatheodorou, 2009).

- can lead to shared meaning-making—allowing teachers to see potential for learning (Ødegaard, 2006).

- offer opportunities for participants to learn by engaging in humour with their peer group (White, 2014).

- invite opportunities for better understanding of the role of the peer group in learning (Hayashi & Tobin, 2011).

This study set out to provide insights into what pedagogy “looks like” and therefore what is valued (or, conversely, overlooked) as significant for learning—by “dialoguing about dialogue” through analysing, reflecting on, and discussing 2-year-olds’ dialogues with their teachers and peers. This “dialogue about dialogue” is important because:

- understanding the day-to-day work of teachers is achieved through dialoguing with others in collaborative forums (Quiñones, Li, & Ridgway, 2018).

- gaining a greater awareness of what constitutes effective dialogues 2-year-olds and others leads to better learning (Ødegaard, 2006).

- inviting teacher awareness of the impact of their dialogues increases pedagogical attunement and therefore understanding and appreciation of young learners (Birigen et al., 2012; Elfer, 2014; Mathers, Eisenstadt, Sylva, Soukakou, & Ereky-Stevens, 2014; Recchia & Shin, 2012).

- recognising the embodied nature of dialogues with very young children can lead to improved pedagogical interactions (Xiao & Tobin, 2018). “Embodied” means the importance of the body as a central source of interaction (beyond verbal interactions only).

- it avoids the trap of generating “monologic narratives dominated by the voice of the researcher [or teacher]” (Rowe, 2016, p. 183, our emphasis).

It takes a special effort to bring the details of dialogues to mind while also contemplating their potential for learning (Benner, 1984). Our research set out to:

- make explicit the specialised practices required of ECE teachers—who have traditionally worked with 3- and 4-year-olds—in their pedagogical dialogues with, and about, the 2-year-olds who are increasingly attending their services; and

- identify, articulate, and ultimately improve the pedagogical experience for 2-year-olds in ECE settings that traditionally cater for older children, by making explicit the relationship between teacher interactions with and about 2-year-olds and the significance of these for learning.

Four main research questions guided our project (see below).

Research questions

- What do effective dialogues “look like” in preschool settings that are inclusive of 2-year-olds?

- What are the conditions (people, places, and things) that shape effective dialogue with 2-year-olds?

- How do teachers’ in-depth reflections on 2-year-olds’ dialogues contribute to their articulation of effective pedagogical practice for this age group within mixed-age settings?

- What is the impact of teacher reflections and shifts in pedagogical practice with and about 2-year-olds’ dialogues on the learning of 2-year-olds and their peers in mixed-age ECE settings?

Research methodology

The research employed dialogic methodology to construct the meanings generated when teachers scrutinised the dialogues of 2-year-olds in their interactons with people, places and things in the preschool learning environment. Dialogic methodology is based on the study of subjectivities in action (Sullivan, 2012). Emphasis is placed on the potential of dialogue “to shape selves and look at how selves can respond, in different ways, to this shaping” (p. 43). This means that the focus is both the dialogues themselves and how teachers notice, recognise, and respond to dialogues as a source of shared meaning (intersubjectivity) and/or disruption of meaning (alterity). These are described as a dialogic event:

| A dialogic event is a strategic interaction that seeks and often (but not always immediately) receives a response. It can alter meaning and/or contribute to shared meaning for some or all involved). |

Researchers and teachers interrogated in detail the videoed dialogue events involving 2-year-olds, in order to exploit the potential of dialogue to shape meaning. Their interrogation involved fine-tuned qualitative and quantitative analysis of spoken and unspoken videoed dialogues, and subsequent dialogue between teachers and with researchers as they sought to interpret their pedagogies. It required the capture of video data, interpretations of its significance through coding, and reflection on the data by those directly and indirectly involved in each event. This allowed the fullest appreciation of the data’s meaning and pedagogical significance.

Research design

The design of the study was based on the premise that combining multiple perspectives allows for greater understanding. The multiple perspectives approach operationalises the concept of “visual excess” (Bakhtin, 1986). It provides opportunities for input from multiple others who have visual access to the direct event and can interpret its significance from diverse “outsider” perspectives. Teachers and researchers interpreted the video footage of 2-year-olds’ dialogues at two points in the study—collaborating to discover what more could be learnt when multiple eyes were brought to bear on the video, to understand dialogue as a pedagogical event for 2-year-olds. In year 2 of the project teachers revised their approaches/strategies as a result of their insights, taking into account what they had learnt from the analysis at the end of Year 1.

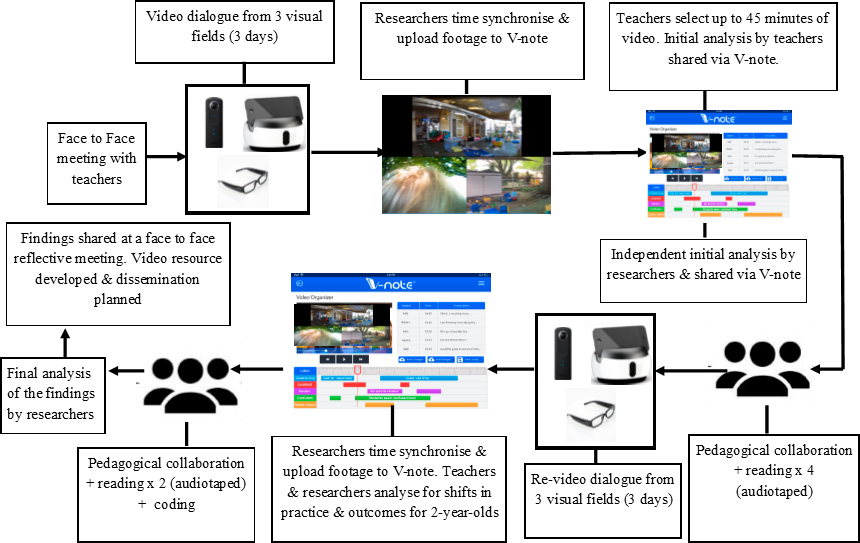

Figure 1 below shows the overall design of the research.

Figure 1: Research design

The three “visual fields” captured through video comprised:

- The visual field of teachers. Teachers used video-recorder glasses to record their pedagogical experience as they moved around in the preschool space.

- The movement field of one 2-year-old at a time. Swivel tracking video cameras with microphones followed children as they moved about in the preschool space.

- A 3600 view of the preschool space. A 3600 video camera captured the wider environment, including the positioning of 2-year-olds within the preschool space.

Video footage from the three different visual fields was time-synchronised using a polyphonic video approach (White, 2016). Teachers were then invited to select a series of effective dialogues, based on the definition of a dialogic event mentioned above:

Specifically, teachers looked for two key features of dialogue as follows:

- Language forms that were responded to—they were heard or seen, and responded to in some way (i.e. they were noticed, recognised and responded to by another person—teacher or peer), and

- Interactions where something was “produced” out of the dialogue. It did not have to be based on the agenda of the adult but the dialogue led to some sort of meaningful response.

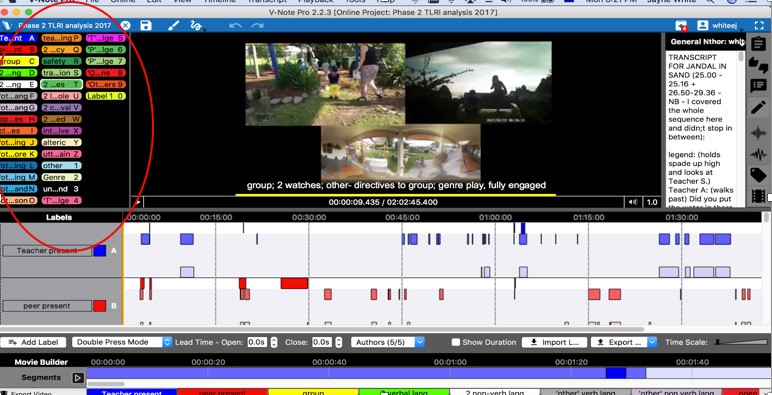

Based on these criteria, teachers selected 4 hours of video footage (over the two analysis phases of the project). This footage was uploaded into a software programme called V-note (n.d.), which facilitated analysis and coding (see Figure 2 below).

Figure 2: Screenshot of video analysis using codes in V-Note

Codes were generated based on a combination of language forms, their strategic use, and the interpreted meaning in relation to dialogic concepts (see Appendix 2). The coding was then converted into a series of graphs. These provided a central source for meaning-making discussions about the significance of the dialogues for 2-year-olds’ learning. Codes were clustered for further analysis into three categories:

- language of 2-year-old (verbal and nonverbal teacher and peer language responses)

- conditions (orienting strategies used by teacher and peer, and the genre in which effective dialogues took place)

- what was produced out of the dialogic event, concerning learning for 2-year-olds.

These three categories (or features of effective dialogue) provided a series of provocations for teachers concerning their practices with and about 2-year-olds. These culminated over two key phases—phase 1 at the end of the first year of analysis during pedagogical collaboration in November 2017, and phase 2 following the implementation of revised pedagogical strategies, re-coding and evaluation at the final reflective meeting in December 2018.

Key findings

The following section outlines our key findings in relation to each of our four research questions.

1. What do effective dialogues “look like” in preschool settings that are inclusive of 2-year-olds?

In order to answer this research question, teachers had first to understand how 2-year-olds engaged in dialogues within the preschool setting.

What do 2-year-olds say and do in preschool dialogues?

Coding of 2-year-olds’ dialogic events required teachers to “see” language as a series of bodily interactions, rather than as a verbal exchange. Similar to Nordic studies of 2-year-olds in early years settings (Løkken, 2000; Rutanen, 2014), teachers discovered that 2-year-olds learnt a great deal through movement in space, engaging in fleeting yet connecting ways rather than attending to traditional forms of “activities” or teacher-identified “interests”.

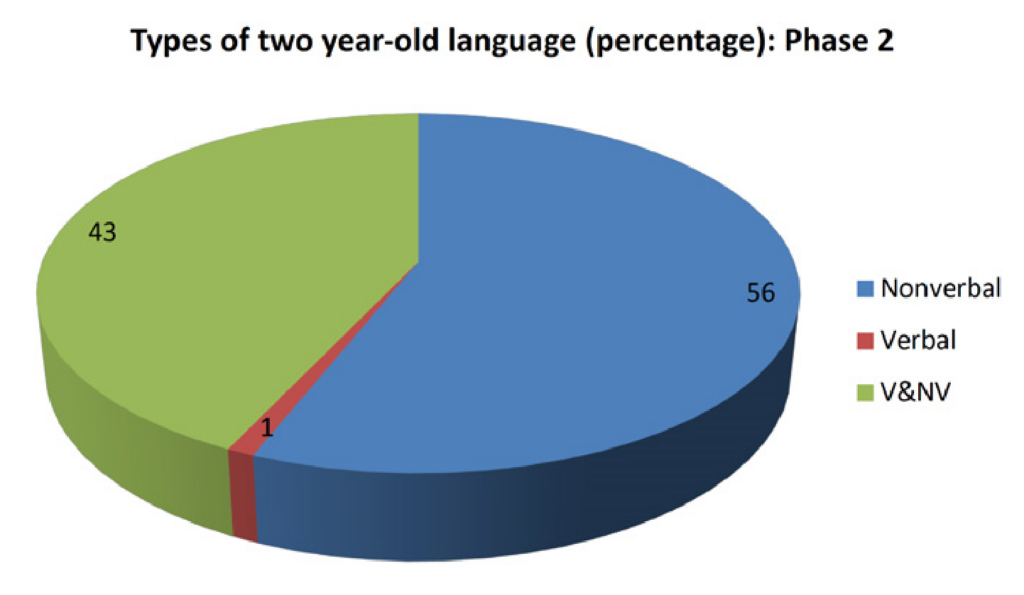

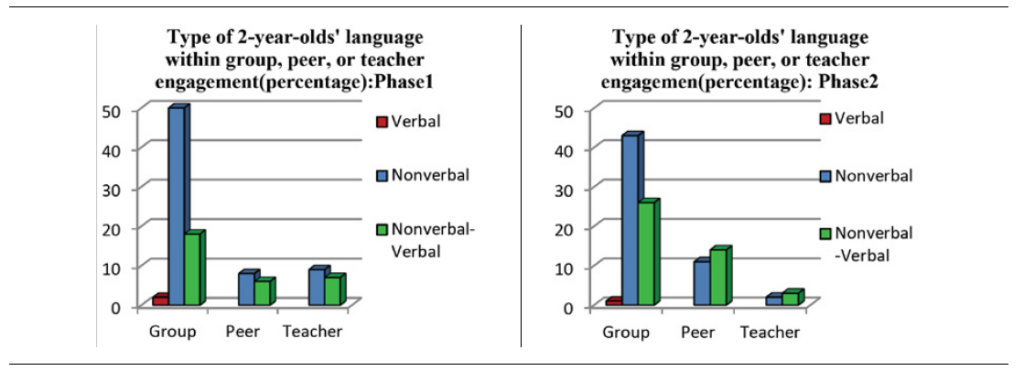

Figure 3 presents the different types of language that 2-year-olds employed, identified at phase 2: verbal, nonverbal, and a combination of these language types. The quantitative findings highlight nonverbal language as an important feature of 2-year-olds’ dialogue.

Figure 3: “Seeing” 2-year-olds’ verbal AND nonverbal language

Two-year-olds used nonverbal language more often than teachers had previously realised. Teachers described the significance of this finding for their practice:

We can clearly see that nonverbal language is as, if not more, important than verbal in 2-year-olds’ dialogues. When verbal is used it’s often in combination with nonverbal. Verbal for 2-year-olds is not just a word, it’s about the sounds, the shouts, the laughter, the tones and grunts and so on—they all give meaning to the dialogue. [Teacher, hui 5]

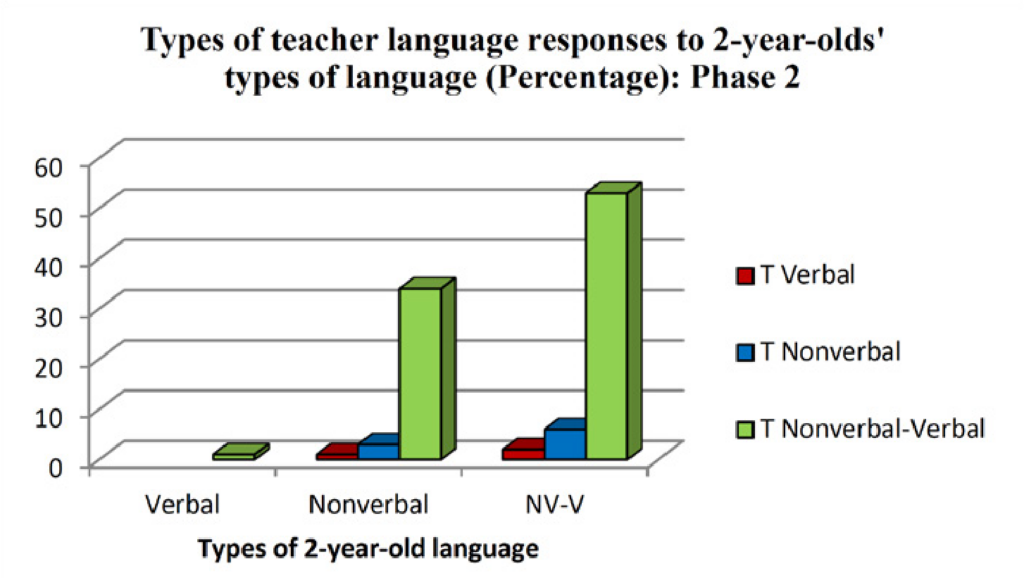

Teachers came to realise the communicative purposes of bodily gestures, movements, and sounds as language forms that had previously gone unnoticed. Teachers noticed 20% more nonverbal and verbal language combinations employed by 2-year-olds in dialogue than they had at phase 1. What this meant was that, by phase 2 of the study, teachers had altered the language they used to respond effectively to 2-year-olds, using less isolated verbal talk and more combinations of nonverbal–verbal language as illustrated in Figure 4:

Figure 4: “Seeing” the importance of nonverbal–verbal teacher response combinations

The discovery that embodied language, as well as nonverbal–verbal combinations, is central to the way 2-yearolds learn meant teachers slowed down their dialogues to pay attention to 2-year-olds’ language priorities. In doing so they respected the agency of the 2-year-olds, which is imperative for effective learning. Teachers took the time to understand and appreciate what was being offered in the dialogue before intervening or shutting it down. As a consequence, teachers altered their practice to ensure they gave 2-year-olds:

… more time to respond, make choices, to think things through, to revisit …

We realise that we used to talk too much before and now we are stepping back to allow that time …We are now using nonverbal–verbal combinations a lot more in our dialogues at the centre. The richness of the dialogue is more now as a consequence. [Teachers, hui 5]

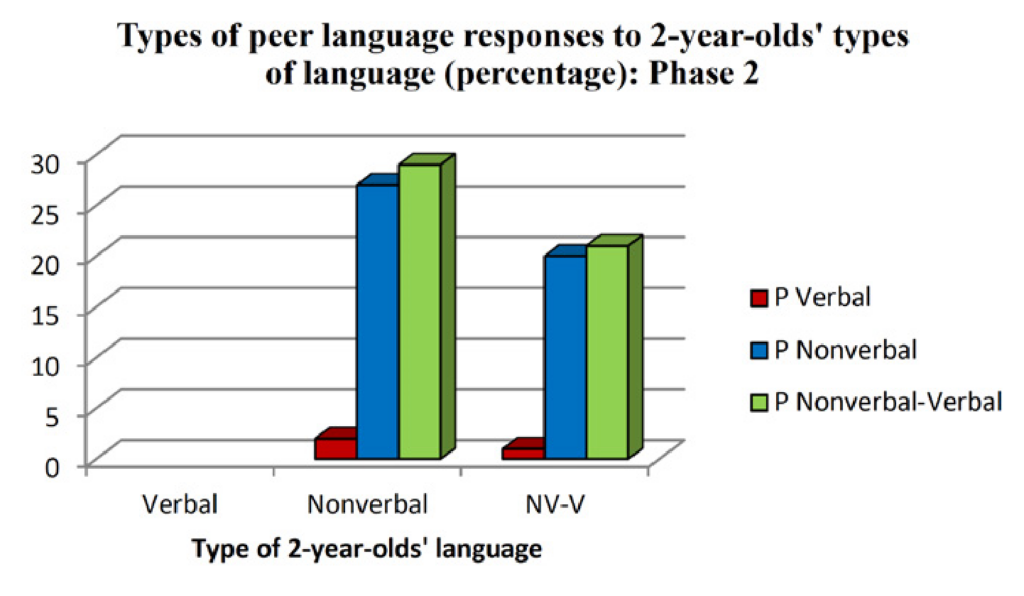

This new appreciation of verbal and nonverbal language combinations and their potential for 2-year-olds’ learning challenges dominant perspectives in the ECE field that privilege very young children’s verbal language interaction (Degotardi, Torr, & Han, 2018; Siraj-Blatchford, 2007). Teachers in the current study, at phase 2, noticed that older peers communicated effectively with 2-year-olds using heightened levels of nonverbal language (47%) or nonverbal–verbal language combinations (50%) as opposed to isolated forms of verbal language (3%) as demonstrated in Figure 5.

Figure 5: “Seeing” the importance of embodied peer language responses

This finding reinforces the importance of teachers recognising embodied language as a valued form of communication. This recognition will allow them to respond better to the priorities of 2-year-old learners in ways that include older peers.

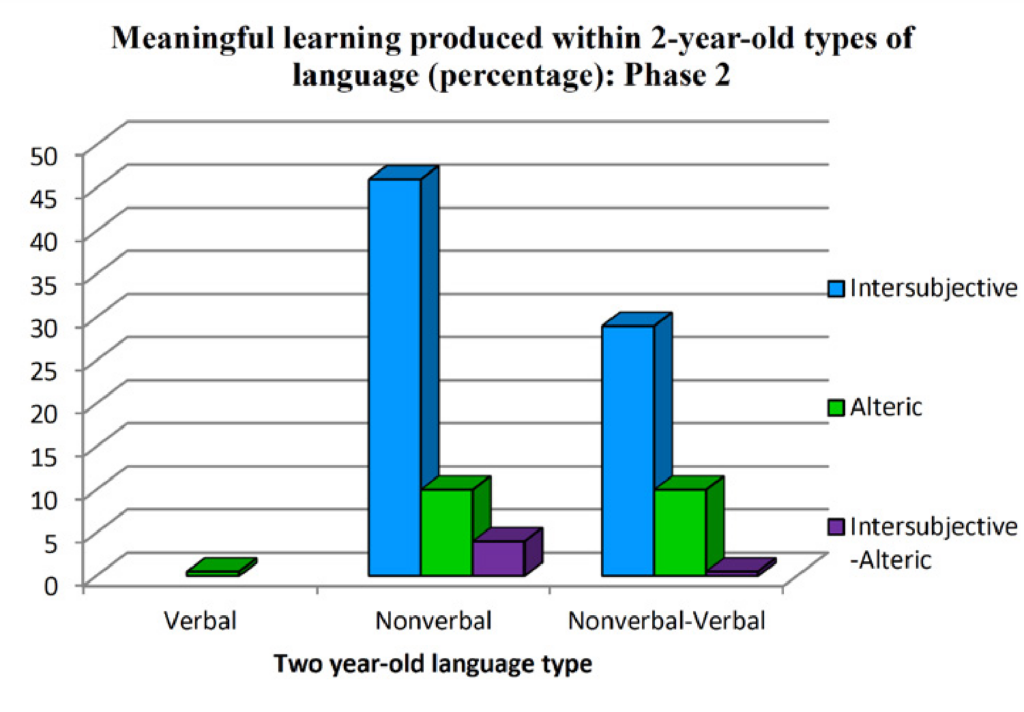

By phase 2 teachers had significantly increased their attention to 2-year-olds’ nonverbal language, particularly in combination with verbal language. This meant that they “placed more emphasis on relationships” [teacher, hui 5] with 2-year-olds. Their coding of intersubjective (where teachers felt there were shared meanings) and alteric (where teachers perceived a disruption or difference in meaning) was much greater when non-verbal (or combinations of verbal and non-verbal) forms of language were recognised as present (see Figure 6 below).

Figure 6: Meaningful learning (intersubjective, alteric, intersubjective–alteric) produced within 2-year-old types of language

Teachers noticed moments of full engagement and intersubjectivity where meanings were shared and there was often a consensus within the group. An example of intersubjective engagement is illustrated in image 1. Two-year-old Legend enacted agency by moving away from a sieving activity to engage with his teacher Shavaurn and his peers digging holes in the sandpit.

Image 1: Intersubjective learning engagement

Before entering this experience, Legend watched then used language expressed through the body to fully engage with Shavaurn and his peers. The rich learning that occurred for Legend in this dialogic event was supported by Shavaurn as she demonstrated how to use a spade safely and facilitated peer engagement. Tuning into Legend’s nonverbal cues, Shavaurn offered him a spade, problem posing (Reynolds, 2008) in order for him to find a solution with his older peers rather than solving the problem for him. Throughout this intersubjective experience, Shavaurn stepped in and out to enable Legend and his peers to lead and learn together. Shavaurn drew on a range of pedagogical strategies throughout this interaction, including instructing, suggesting, demonstrating, and nonverbal–verbal language. The intonation in her voice matched the instruction, “Legend, look, keep my spade down low. That’s up high. Down low [alters the tone from low to high]”. While Shavaurn drew upon verbal language, she used it repetitively in combination with nonverbal language as she demonstrated how to use a spade, and also used verbal intonation strategically to match her body movements.

Learning is also taking place for 2-year-olds in preschool settings when there is a mismatch in meaning. This occurs when meaning is altered or disrupted to take another direction. By tuning into the language of the 2-year-old, teachers became increasingly willing and able to appreciate alteric encounters, when 2-year-olds actively pulled away from shared meaning. Over time, teachers came to see these alteric dialogue encounters as an important source of agency for 2-year-olds as learners in the preschool space.

Two-year-old Zion was engaging in an intersubjective event with his peers at the water fountain. Noticing that Zion’s shoes and clothes were getting wet from a leak under the water fountain, his teacher Bev pointed this out and moved his leg back to stop him getting wet. Zion’s alterity was evident in the way he responded by stretching out his leg and assertively placing it under the drip. This alteric engagement—Bev pushing Zion’s leg back, Zion pushing his leg forward—continued until Bev, through the effort of trying to understand the provocation that arose from Zion’s alterity, stepped back “to let the [peer] play roll” (Bev’s words) rather than shutting it down through her intervention.

Image 2: Alteric learning engagement

Bev altered her practice to ensure she did not overlook Zion’s agentic contribution to his own learning and the learning that was taking place in the environment—for his peers and also for herself. In line with intersubjective events, these alteric encounters provided teachers with opportunities to be more aware of their role as dialogic partners.

One teacher explains:

We can see that alterity is so important for 2-year-olds as agentic learners … asking ourselves, does it really matter if they break the rules? And even celebrating rule-breaking as alterity. [Teachers, hui 5]

Teachers came to value that 2-year-olds’ strategic use of diverse forms of language at times generated shared meanings with peers that were in direct opposition to their adult priorities. Interestingly, almost all (80%) of these intersubjective–alteric events took place in silence, when 2-year-olds employed nonverbal language. When recognised by teachers, these findings gave great insight into the learning priorities of 2-year-olds. These priorities were expressed through intersubjective and/or alteric encounters with others, including older peers who were now seen as pedagogical partners. By phase 2, teachers had realised the importance of these dialogic events. They recognised that forcing synthesis or allegiance to adult priorities alone led to pedagogical practices that did not always support effective dialogues with 2-year-olds, nor, by association, learning.

By paying attention to nonverbal forms of language, teachers also discovered how often 2- year-olds were watching others in the ECE context. Watching as a nonverbal feature of dialogue comprised 33% of all selected dialogic events. This study concurs with previous research that has emphasised the importance of watching as a means for very young children to learn how to be with older peers in the early years—often on the periphery of dialogue (Hayashi & Tobin, 2011). However, in the current study 2-year-olds were not merely watching in order to imitate actions or behaviours, as previous research has suggested (see Wittmer, 2012). They were watching on the periphery as a prerequisite for entry into a particular genre (30%), and more often within a genre (70%) prior to engaging with others as a communicative partner and negotiator of dialogue in their own right. The teachers described these discoveries as a pedagogical shift because:

… we now take the time to watch the 2-year-olds watching. We allow them that time to watch and this has been a huge shift for us. If you see them on the periphery watching we are more aware that that is what they are doing and that it is important … 2-year-olds watch their older peers very carefully and then utilise what they see to give them an “in” [into the group.] [Teacher, hui 5]

What do teachers say and do in dialogues with 2-year-olds?

As part of their analysis over time, teachers were able to see the different strategies they were using and the impact of these for 2-year-old learners. Coding at phase 1 showed teachers used combinations of questioning, instructing, suggesting, offering, narrating, or moderating. They used demonstrating as a pedagogical strategy less often. In the selected video dialogues at phase 2, teachers used multiple strategies, including demonstrating. This discovery reflects teachers’ greater awareness of their own nonverbal cues and the increased value they placed on demonstrating as an important strategy to apply in tandem with questioning, narrating, instructing, suggesting, or offering. Teachers explained their new insights in relation to effective dialogues with 2-year-olds meant they were

using questioning differently, and wrapping it up in other strategies. Talking less, watching more, checking our understandings … We do not need to ask them [2-year-olds] to use their words, but support them and others to see what they are conveying. It is our responsibility to tune in. [Teachers, hui 5]

Teachers also realised the importance of giving 2-year-olds time to communicate using verbal and nonverbal language. They also used increased verbal–nonverbal combinations themselves, and watched more:

We have also learnt to watch more ourselves and be more attuned to the goals and what the 2-year-olds are trying to tell us. Teachers need to have an “evaluative eye” in dialogic events so as not to only promote our own agenda onto the event that is taking place—watching, looking, to be able to see it through the child’s lens rather than our own. It is easy to put our own authoritative discourse and agenda to manipulate an encounter as we are always pressured to be seen to extend, support, and encourage learning around a predetermined set of goals. Usually these are not set by the child but [by] teachers and parents. [Teacher, hui 5]

Discoveries such as these led teachers to describe 2-year-olds’ learning as a “dialogic dance” that took place between 2-year-olds and teachers as well as between 2-year-olds and peers.

We have noticed that there are inside–outside dialogic dances taking place in this manner all the time for 2-year-olds as they work all this out. [Teacher, hui 5]

Teachers became less certain about their depictions of 2-year-olds as a consequence. They recognised increasing complexity in their dialogue accordingly:

We also know that after hours of coding we sometimes need to look at things over and over again to see new things. It is through the “effort of trying”, through dialogue with 2-year-olds, through dialogue with staff, through fine-grained coding and re-thinking, re-writing, reading, that our capacity to “see” more and see anew is altered each time we look. [Teacher, conference presentation, 2018]

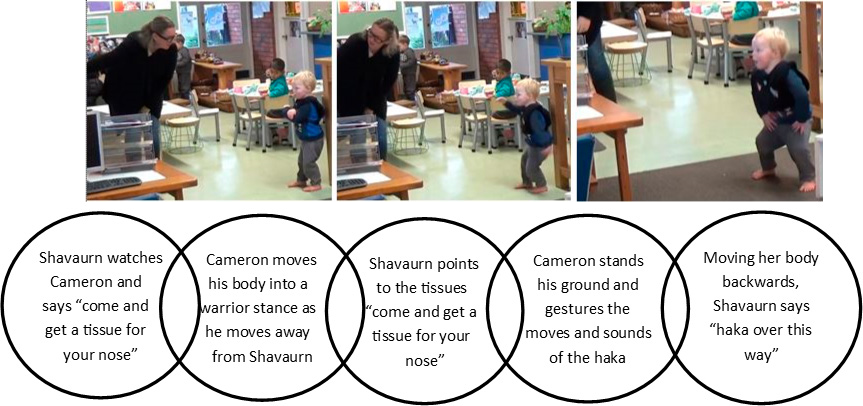

Teachers realised that 2-year-olds’ dialogues often took place in fleeting moments sustained over time, rather than in one sustained dialogue in the moment. Teachers recognised these events that linked to another later or beforehand, building on meaning, as utterance chains.

| Utterance chain: From a dialogic stance utterance can be understood as combinations of (verbal and nonverbal; spoken and unspoken) language forms that anticipate a response. When an utterance chain sparks meaning—a response—it has the potential to become an event of co-being because it generates an intersubjective interaction of mutual significance. (White & Redder, 2017, p. 82) |

When teachers started to link what had previously seemed like insignificant discrete language events over time, they began to recognise the increased meanings and learning potential of these events. In the following example (image 3), 2-year-old Cameron uses the haka for a variety of strategic purposes over the morning—first as a member of his peer group, next as an act of defiance to having his nose wiped by a teacher, and thirdly as a means of protecting his play space from others. These acts made up a chain of connected meanings (an utterance chain) that allowed his teachers to appreciate more about Cameron’s ways of learning in the preschool environment, and of Cameron as a unique personality with an important contribution to make in this space.

Image 3: Fleeting moments sustained over time that make up the utterance chain

Image 4: Cameron and Shauvaurn – an act of resistance

Cameron’s teachers, Shavaurn and Catherine, commented:

He’ll do that [haka] as an achievement, as a form of resistance and there are so many ways he can utilise this one language act—he’s still doing it now! [hui 5]

What do peers say and do in dialogues with 2-year-olds?

The role of older peers in these dialogues could not be overstated. Teachers were surprised at the extent to which peers were engaged in a variety of ways within the dialogues. Recognising that shared meanings are integral to relationship formation with people, teachers noted:

Before this research, based on what developmental literature told us, we used to think that children developed friendships in tandem with their developing verbal language. Well, that’s not what we are seeing here. They [2-year-olds] are highly capable of forging relationships with peers through their non-verbal language. [Teacher, hui 5]

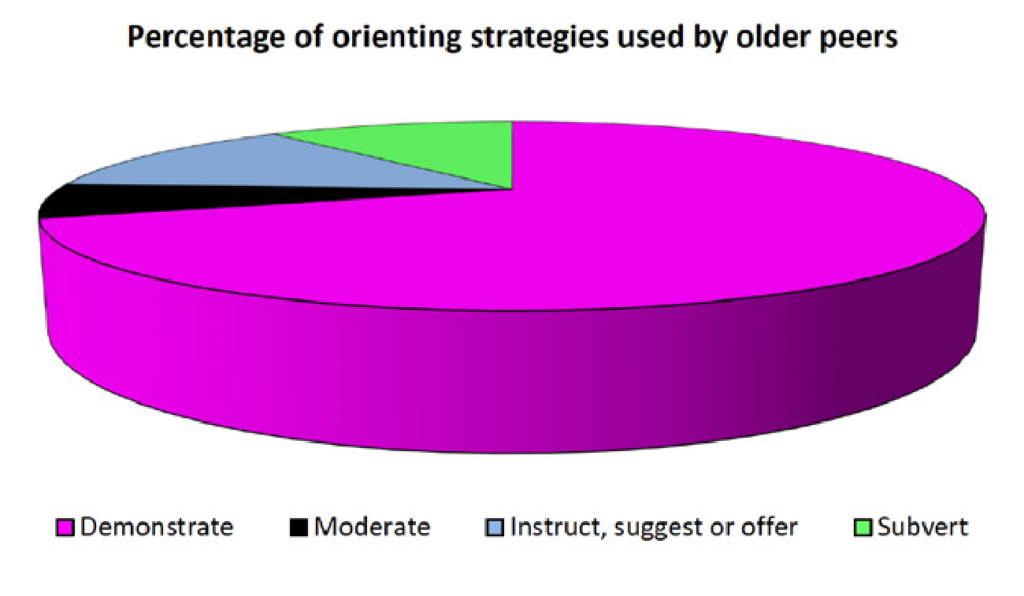

Over a total of 190 events, peers were present for 181. Indeed, peers were present in interactions with 2-year-olds more often than teachers (teachers were present for 142 events). Peers used a range of teaching strategies in dialogues with 2-year-olds, such as demonstrating, moderating, instructing, suggesting, offering, or subverting. Sixty percent of these strategies were carried out using nonverbal–verbal combinations, 35% using isolated nonverbal forms of language, and only 5% using isolated forms of verbal language. These findings reinforce the importance of embodied language and its use by older peers when engaging effectively with 2-year-olds. The following graph (Figure 7) highlights the varying strategies used by peers within 2-year-olds’ dialogues that were recognised by teachers by phase 2 of analysis.

Figure 7: Shifts in “seeing” peers as dialogue partners (and pedagogues)

Peers employed demonstrating as an orienting strategy more frequently than teachers in effective dialogues with 2-year-olds (peers 70% vs teachers 22%), highlighting the integral role peers play as pedagogues in these preschool spaces. Almost 50% of these peer demonstrating strategies comprised isolated forms of nonverbal language responses. When peers employed instruct, suggest, or offer (13%), they were more likely to use nonverbal–verbal combinations. An example of this type of peer engagement is illustrated in image 5.

Image 5: Peer pedagogical strategies at play in effective 2-year-olds’ dialogue

Zion’s older peer instructs him to have a drink using a sequence of different nonverbal, then nonverbal–verbal, combinations of language forms. These included the affirmative nod of the head, extension of the arm, inward roll of fingers, gaze, smile, and “come”, subsequently demonstrating how to use the tap. This discovery highlights the vital role peers play as demonstrators and instructors within effective dialogue with 2-year-olds. This aligns with Hayashi and Tobin’s (2011) work in Japanese preschools, which highlighted that meaning is conveyed through embodied language. As the teachers in the current study explained:

Peers are very important for 2-year-olds’ learning. They are doing a lot more demonstrating than teachers are.

The play is sustained even though the teacher is not there, in some cases even because they are not there. [hui 5]

Like the teachers in Hayashi and Tobin’s (2011) study, these teachers found benefits when opportunities were made available for older peers to take on a leadership role with 2-year-olds—as pedagogue, rangatira, or tuakana as well as teina. An example of this is illustrated in image 6.

Image 6. Older peer as pedagogue, rangatira, tuakana

Legend’s older peer was engaging with him in the sandpit when it was announced that it was morning tea time. Utilising nonverbal-verbal forms of communication, Legend’s peer bends down to his level, makes eye contact, and informs Legend that it is “morning tea time”. He offers Legend a hand and they walk together to the bathroom to wash their hands. On the way, Legend’s peer notices Legend’s hat on the ground. He picks it up and helps Legend put it on. In the bathroom he instructs Legend on the handwashing routine and subsequently accompanies Legend to his bag, where he suggests where to place his lunchbox and drink bottle as well as where to sit.

Another peer strategy that was viewed as vitally important to 2-year-olds’ dialogue was subvert. Teachers had previously dismissed or overlooked this strategy, which they had previously viewed as a problem. However, it was a feature of 2-year-olds’ dialogue with peers, particularly when teachers were not looking. The 3600 camera often highlighted these dialogues where older peers would include 2-year-olds in play that did not meet with the teacher’s approval, such as spitting water into the sandpit or singing “rude” songs at the kai table. Teachers’ new insights meant that they recognised the importance of 2-year-olds going against the grain in order to gain entry into the peer group. In doing so, teachers celebrated 2-year-olds’ agency by recognising and embracing their acts of resistance as vitally important to effective dialogues.

Extending the work of Rameka, Glasgow, & Fitzgerald (2016), while 2-year-olds were without question operating as teina in a tuakana–teina relationship through observation and watching, they also played a leadership role in their own right. For example on several occasions 2-year-olds were observed directing their older peers into routine genre such as mat time or meal time—replicating the dialogues they had previously had with others in the preschool space:

Overall, we have been surprised that what we have learnt about 2-year-olds is also relevant for our work with older children. And we have realised that the culture we establish with older children plays an enormous role on the possibilities for 2-year-olds. [hui 5]

Teachers’ new insights in terms of effective dialogue with 2-year-olds meant that they began to notice strategies being employed by peers that they had previously not considered. For example, if 2-year-olds ignored a teacher’s request, the teacher drew upon support from the peer group. This sometimes resulted in peers interpreting the teacher’s meaning, such as nonverbally gesturing to have a drink or verbally stating “She wants you to wipe your nose.”

Group engagement with 2-year-olds’ dialogue

Two-year-olds’ total engagement in dialogues with others was fairly equal in both rounds of 2-hour coding (first round of coding 1 hour 42 minutes 27 seconds in total; second round of coding 1 hour 43 minutes 40 seconds in total). The combined total duration of 2-year-olds’ engagement in dialogue with others across both coding rounds was 3 hours 25 minutes 10 seconds.

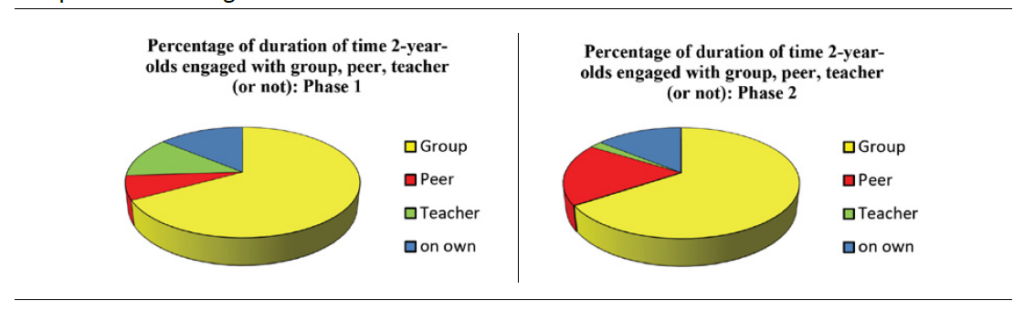

Across both phases of coding, 2- year-olds spent a similar amount of time in group situations with both teachers and peers. This finding moves away from the assumption identified previously by New Zealand teachers that 2-year-olds need individual one-on-one attention as opposed to group time (White et al., 2016). Teachers’ new insights in relation to the importance of the peer group (see previous section) are evident in Figure 8, which reveals increased levels of peer presence (before 7%; after 18%) and much less time spent engaging with 2-year-olds without peers present. Figure 8 highlights no changes in the amount of time 2-yearolds were on their own without engaging with teachers or peers.

Figure 8: Percentage of 2-year-old engagement with group, peer, teachers, or on own at phase 1 and phase 2 of coding

Phase 2 analysis also showed increased levels of verbal–nonverbal language combinations when 2-year-olds engaged within a group as opposed to with peers or teachers alone (see Figure 9).

Figure 9: Percentage of 2-year-olds’ language within group, peer, or teacher types of engagement

In addition, findings revealed increased levels of 2-year-olds’ language usage across the same overall duration of time (133 events in Phase 1; 190 events in Phase 2). These findings suggest that pedagogical practices that are more responsive to the importance of verbal–nonverbal language combinations and peer involvement with 2-year-olds in group learning may support more effective dialogues with 2-year-olds.

2. What are the conditions (people, places, and things) that shape effective dialogue with 2-year-olds?

In order to understand the different types of dialogue that took place for 2-year-olds in preschool settings, we operationalised the dialogic concept of “genre”.

Genre are clusters of language events that are characterised by certain ways of communicating, thus producing different combinations of dialogue for different strategic purposes (Rockwell, 2008; White, 2017b). Genre are the drive belts to meaning in dialogue (Bakhtin, 1986).

i) The people and places of genre

Attention to the different genre enabled a greater understanding of the different types of dialogues that were occurring for 2-year-olds within the preschool setting. Genre have special “rules of encounter” that must be applied to engage in certain (often sanctioned but not always by the adult) ways. These “rules of encounter” are traceable through distinct combinations of language forms. By phase 2 of the study teachers and researchers had identified several distinct genre in which dialogue events took place:

- Care routine genre: These dialogue events occurred during mealtime and toileting/changing routines where 2-year-olds were in close proximity with teachers. During these events teachers used language combinations of demonstrating + questioning + narrating + instructing/suggesting/offering = leading to moderate degrees of intersubjectivity or alterity.

- Transition genre: At times when 2-year-olds were moving between spaces such as moving from outdoor play to mat time or shifting from a mealtime to indoor play. These dialogic events were most commonly shared with teachers who used similar language combinations as those in care routines but which led to much higher degrees of alterity than intersubjectivity. Peers played a significant role in this genre—often demonstrating what to do next.

- Imaginative play genre: Comprised largely of role playing (e.g. Spiderman) typically thought to be beyond the developmental grasp of 2-year-olds, these language events largely occurred outside of the gaze of teachers. Two-year-olds were significantly more likely to be in close proximity to or watching peers, with a high proportion of subversion evident. These interactions led to higher degrees of alteric–intersubjective combinations (where there was more of a push and pull towards meaning with peers and often away from shared meaning with teachers).

- Construction genre: More likely in a group, with higher degrees of demonstrating + instructing by teachers and peers, and moderating by peers only. More often led to intersubjectivity than alterity.

- Sandpit play genre: Dialogic events in sandpit play featured heavily across all sites and was comprised of high degrees of peer AND group engagement (with teachers). Dialogues were comprised of a larger proportion of demonstrating used by peers and teachers, leading to intersubjectivity, alterity, and combinations of both.

Each genre was oriented differently by teachers or peers highlighting the variety of strategies and language combinations that were employed in their dialogues with two year-olds in the ‘preschool setting’. Two-year-olds became different kinds of dialogue partners in these diverse genre as different rules of encounter applied in each context. For example, in imaginative play genre dialogues most often took place with peers without the need for teachers, which meant the peer group typically determined the rules of encounter. Peer pedagogical strategies were a feature of this genre, alongside high levels of 2-year-olds’ agency. This illuminates how the imaginative play genre offered opportunities for 2-year-olds to contribute their ideas and take on a leadership role in the event. When teachers engaged in this genre the play typically altered dramatically or ceased altogether.

In other more traditional genre such as construction, the rules of encounter were primarily determined by teachers. Teachers drew upon an extensive range of pedagogical strategies, particularly instructing, suggesting, offering, questioning, narrating, and demonstrating to engage with 2-year-olds alongside the peer group. Increased levels of verbal language were a feature of this genre because of the skills required in these types of experiences, such as painting. The construction genre offered opportunities for the peer group to model ways of using resources and sometimes to moderate the behaviour of the 2-year-old—inviting very different but nonetheless important dialogues.

Within the care routine genre opportunities were offered for both teachers and peers to engage in one-to-one dialogues with 2-year-olds. Teachers observed that in these preschool spaces 2-year-olds would frequently seek out their older peers for support with washing hands or preparing to eat.

As agents of their own learning, 2- year-olds determined the rules of encounter in some genre more than others. This was especially evident in transition genre, which provided spaces for dialogues that comprised whole body movements, often running and moving in between contexts as a kind of link. Running was often observed and was spread throughout the day as 2-year-olds made choices about who to engage with—teachers, peers, or the group. Watching was a feature of transition genre, particularly on the periphery, as 2-year-olds waited to learn the social code before moving in to participate in the dialogue. These findings suggest alterity can be a powerful source of agency for 2-year-olds, and high levels of alteric learning were produced in transition genre.

The extent to which each genre produced intersubjective and/or alteric encounters differed. This was evident in the diverse language combinations used within each respective genre, which called for different and orienting strategies. For example, the sandpit genre offered opportunities for alteric and intersubjective encounters through the negotiation of meanings with people, places, and things, particularly in a group situation or with peers. Often 2-year-olds were observed pausing within this genre to work things out before engaging. Dialogues in the sandpit genre were characterised by demonstrating, instructing, suggesting, narrating, or questioning. Greater degrees of alterity were discoverable in mealtime genre where 2-year-olds often collaborated with peers to share food or engage in humour that was in resistance to teacher priorities for the dialogue. These events were often characterised by non-verbal language, in groups and outside the presence of the teacher, with much watching taking place.

What is interesting about these findings is that all the different genres—regardless of teacher or peer presence—produced meaningful learning for 2-year-olds. Meaning-making therefore can and does take place across multiple genres, regardless of learning context within the preschool space. The one exception was mat time, which produced the lowest levels of meaningful dialogue, and was characterised by lower levels of peer engagement and 2-year-olds’ agency. Yet mat times offered different types of dialogues. For instance, this genre offered 2-year-olds a chance to stop and rest, and became a punctuation marker for what was to follow. Mat time genre involved a lot demonstrating by teachers and peers in a group situation—giving 2-year-olds opportunities to watch and learn some important rituals for being in the preschool. As a consequence of these discoveries, teachers started to involve older peers more in demonstrating roles at mat times:

Rangatira or tuakana to come up the front frequently and role-model actions. Often 2-year-olds will come up of their own accord. This is like an apprenticeship into becoming a rangitira. Two years ago the 2-year-olds would have been told to sit back down. Two years ago we weren’t using rangatira as much.

Teachers gained a greater understanding in relation to the provision of more traditional genres such as mat time and construction play for 2-year-olds in preschools, inviting very different but important dialogues. They also became more aware of the significance of learning for the 2-year-old in imaginative play, care routines, meal time, transitions, and sandpit play genres in preschool spaces.

ii) The “things” of dialogue

Open or closed (or both) resources were a feature of some genre more than others. For example, objects played an important role in imaginative play genre, providing opportunities for higher degrees of 2-year-olds’ nonverbal and nonverbal–verbal language combinations. Increased levels of intersubjectivity were identified in imaginative play genre alongside orienting strategies used by peers such as subvert or demonstrating—the latter used also by teachers during intersubjective events such as construction play or in the sandpit. Increased levels of intersubjectivity were characteristic of care routines, where 2-year-olds played a teina role and pedagogical strategies used by teachers or peers most often comprised instructions, suggestions, or offers.

In the construction play genre, closed resources were a feature in the form of paintbrushes or paper. However, teachers discovered that 2-year-olds were adept at employing strategies to engage in open-ended ways with closed resources. The following image shows Harry skilfully placing the lids from the felt-tip pens on his fingers. His teacher was able to respond to this action as a result of her increased attention to his priorities in the genre, rather than demanding a more conventional use of the pens.

Image 7: Construction play genre

Important to these discoveries were that “things” did not create dialogues in themselves but provided important cues for 2-year-olds to orient themselves in the dialogue:

Objects have turned out to be an important source of intersubjectivity and often agency for 2-year-olds. They help them to “be” in dialogue. Sometimes we put less out now to facilitate this. We don’t see this as negatively impacting on older peers either, because they are learning to work together within their space, orienting more towards dialogues around objects than the objects themselves. [Teacher, hui 5]

iii) Carnivalesque in dialogue

An important insight for teachers was the recognition that learning often took place for 2-year-olds that teachers had not predicted or planned for. Teachers realised that different kinds of dialogues took place when 2-year-olds and their peers were outside teachers’ visual fields, and that these were of equal, if not more, significance than those they were directly involved in. Teachers began to recognise the importance of the dialogic notion of carnivalesque. This gave them permission to accept subversive and humour-rich events between peers and 2-year-olds as celebrating their creativity and agency, rather than seeing such events as problems to be tamed.

| Carnivalesque: A type of humour that resides underneath solemnity and emerges out of it and because of it (White, 2014, p. 899). |

The following image is of Katie who is playing a leadership role as she playfully (and surreptitiously!) shares food and a joke with her peer group.

Image 8: Meal-time genre

In this meal-time genre, Katie is experimenting with ideas that the teachers don’t necessarily approve of. Here the teacher has already asked the children not to share their food. However, by phase 2 of analysis teachers had come to recognise that 2-year-olds were often negotiating competing demands of teachers and peers. They recognised that these kinds of “rule-breaking” subversions occurred more frequently when expectations were imposed by adults. They realised that 2-year-olds’ responses were important as they gave 2-year-olds entry into peer group dialogues as a central source of learning through participation. The following comment was shared by teachers:

We are now more comfortable with the uncomfortable … This involves risk-taking in terms of how far we will allow things to go. We have developed a greater tolerance for a lack of structure and rules. We now let behaviours such as feet stamping at the kai table go on for a lot longer than before. Two years ago I would have shut that down in a heartbeat, but now I let it go as much as I can because I recognise its value to 2-yearolds as a way into the genre and what is learnt as a consequence of that. [Teacher, hui 5]

3. How do teachers’ in-depth reflections on 2-year-olds’ dialogues contribute to their articulation of effective pedagogical practice for this age group within mixed-age settings?

Through critical reflection in collaborative forums based on fine-tuned coding of the video footage, the teachers were able to think deeply about what it means “to see” 2-year-olds through a dialogic lens. This meant not defending or justifying one’s own practice, but allowing what was “seen” to inform and disrupt prior knowledge in order to see the nuances of dialogues. Teachers realised how often they had previously been describing and asserting 2-year-olds’ learning based on monologic narratives. The most important shifts identified for teachers concerned their pedagogical practices with 2-year-olds. Most importantly, they became more aware of the ways they were implicated in 2-year-olds’ dialogues—even when the 2-year-olds were out of sight. The impact of their reflections was felt in terms of their moment-by-moment interactions with 2-year-olds, their policies and practices surrounding 2-year-olds, and the way they spoke about 2-year-olds in assessment. Ironically, teachers became less certain of their knowledge of 2-year-olds and more oriented to the meanings generated in dialogues as unique events with 2-year-olds themselves. As one teacher explained:

When we went to do the final phase of coding we thought that it would be easier because we had done it before, we’d developed more understandings of what we were supposed to be doing—what the meanings of our codes were and what they might look like. We expected it to be more black and white but instead there were more shades of grey because we had more understanding and it made it more complex … and there was a lot more discussion between us and so now we look at it from that lens rather than having to fit into what we had received. We now see it as a source of dialogue rather than a solution. [Teacher, hui 5]

The following table summarises the key shifts that took place for teachers over the 2 years of this study.

| From seeing 2-year-olds as … | To seeing 2-year-olds as … |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| From seeing their pedagogical role as … | To seeing their pedagogical role as … |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

When asked what contributed most to their shifts, teachers responded:

The readings that we did prior to our discussions were instrumental in being open to new ideas and ways of thinking. This was then further enhanced by the dialogues about dialogues at the hui … listening to others and being challenged on our own thinking also combined to make the shifts more real … Plus coding also helped us see more … This all took time and commitment from all parties and the understanding that none of it was personal—it was for the betterment of the tamariki. [Teacher, post hui 5]

4. What is the impact of teacher reflections and shifts in pedagogical practice with and about 2-year-olds’ dialogues on the learning of 2-year-olds and their peers in mixed-age ECE settings?

As a consequence of their careful examination from a dialogic standpoint, teachers came to recognise that dialogue is learning. What this meant for them in their articulation of 2-year-olds as learners was an appreciation of 2-year-olds’ agency, and the potential for teachers to shut this down when dialogues were not appreciated. Teachers were increasingly able to recognise and respond to 2-year-olds as learners through intersubjective events that were characterised by attuned dialogues. These events were made up of increased levels of verbal–nonverbal language combinations, slowing down, pausing, positioning of body at the 2-yearolds’ level, recognising non-verbal cues, and using a variety of different strategies across different genres. The following image is of Harry and his teacher Catherine as they engage in an intersubjective event. Catherine is earnestly trying to understand Harry’s meaning.

Image 9: Responding to the 2-year-old as a learner through an intersubjective event

Initially, Catherine pursued one line of enquiry in this dialogue. She then realised that Harry was not interested in the blocks but rather in the telescope that he had made earlier with Shavaurn and his peers. Noticing this utterance chain, Catherine responded by altering her initial line of inquiry (and sight) to follow Harry’s learning trajectory. She explained:

Levels of intersubjectivity have definitely increased in our practice, and these have been increasingly combined with a series of strategies that we now use to engage in dialogues. [Teacher, hui 5]

Importantly, teachers also came to see the importance of alterity. This dialogic concept has given teachers licence to embrace and celebrate 2-year-olds’ ways of being that had traditionally been viewed as deficit. Through an appreciation of 2-year-olds’ alterity, teachers found a way of re-visioning what might be otherwise seen as problematic behaviours (which teachers often ascribe to 2-year-olds) to a stance of assertion, with links to agency and empowerment for one’s own learning. Alteric dialogue events represented a point of negotiation and also of increased levels of tolerance for different ways of working with people, places, and things which began to characterise teachers’ pedagogy.

We can see that alterity is so important for 2-year-olds as agentic learners. We can see how the same act can have so many different meanings and that we need to try to understand these. Sometimes this leads to intersubjectivity and sometimes it doesn’t, but it’s the effort of trying that we are focusing on now, and we do this in partnership with families who can help us fill in the gaps. [Teacher, hui 5]

To support these kinds of dialogues, teachers made specific changes to policies:

Revising our expectations in practice and policy… We have developed a greater tolerance for a lack of structure or rules; we have altered our practices to respect 2-year-olds’ preferences, for example who they want to be with.

Both ECE settings in the project used their insights in revised Social Competence Policies:

| While group activities are offered there are opportunities and places for children to watch activities or to be ‘out-of-the group’, on their own; particularly 2 year olds. Teachers will support them into an activity when they are ready. [Positive Guidance and Social Competence Policy] |

| 2 year olds are recognised as unique and with this we will allow them to show agency, intersubjectivity and have time to watch. We also acknowledge this age’s ability to show carnivalesque and or go underground. Teachers will have an understanding of these terms and allow use of strategies to identify and respond appropriately. [Positive Guidance and Social Competence Policy] |

| We understand and value alterity and agency especially with our 2-year-olds. Behaviours that are often viewed as problematic need to be considered carefully first. These moments are seen as significant learning moments for children. [Social Competence Policy] |

One ECE service also altered their key teacher policy in consideration of 2-year-olds, as highlighted in the following policy excerpt:

| Where a child chooses to be nearby a particular teacher, if they are younger, this will not be discouraged, but viewed as a platform to build a strong relationship with one teacher so they can then catapult themselves into the life of the kindergarten and form relationships with others. Initially a key teacher supports the child, however this is constantly evaluated as the child’s preferences are considered. [Transitions Policy] |

Teachers also began to integrate utterance chains as a central provocation in writing learning stories:

We’ve begun to re-think interests as utterance chains for 2-year-olds. Their dialogues don’t happen in one moment but are connected over time. Our recognition of them is not so much to come up with some sort of endpoint learning, but as a way of entering into dialogues of meaning-making. [Teacher, hui 5]

Teachers also started to write themselves into the stories as they recognised their role as dialogic partners:

Learning often goes beyond “interests” and “curriculum areas”, such as negotiating rules for our 2-year-olds. As such we have shifted our focus away from interests to more focus on the relational encounter. [Teacher, conference presentation]

Image 10: Shift in writing learning stories

For other examples of learning stories please see the website resource https://www.waikato.ac.nz/age-responsive/

Interestingly, teachers did not see that larger changes to the physical preschool environment were needed. This view sits in contrast to the Duncan et al. (2006) study, which emphasised the environment. The teachers in the Duncan et al. (2006) TLRI project discussed removing challenges in the environment in response to their perceptions of 2-year-olds’ incompetence. For the teachers in the present study, where they had previously seen expansive spaces and challenging equipment as a problem, they now recognised that 2-year-olds were capable of making choices themselves. If they needed help, they would find ways of asking either teachers or peers—often through non-verbal strategies. This study also foregrounds the environment as being integral to facilitating 2-year-olds’ movement in space, aligning with Georgeson, Campbell-Barr, Mathers, Boag-Munroe, Parker-Rees & Caruso’s (2014) call for research efforts that provide a heightened awareness of the importance of movement for 2-year-olds. As a consequence, teachers focussed less on changing the environment and more on “seeing” 2-year-olds and appreciating their dialogues.

Two year-olds definitely have their own ways of being in our environments, and in recognising this, we give them and ourselves permission to celebrate their learning—based on their priorities, not ours. [Teacher, hui 5]

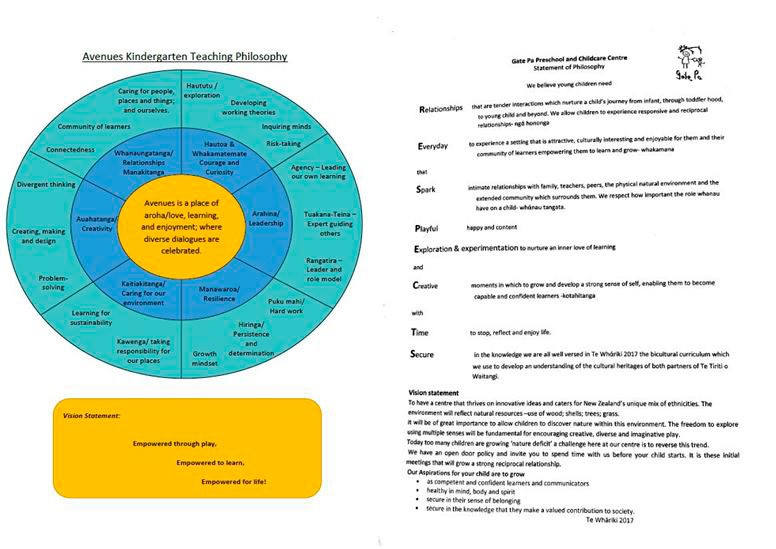

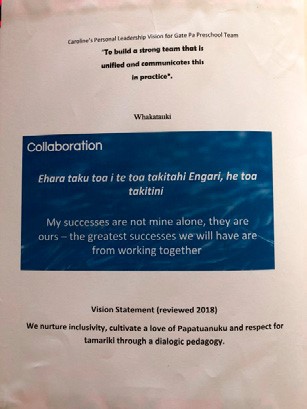

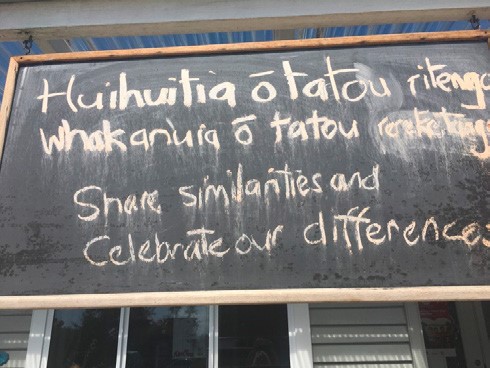

Teachers reviewed their new philosophies to place dialogues at the centre of curriculum.

Image 11: ECE services’ philosophies

Image 12: Vision statement

Conclusion

This project addressed residual gaps in New Zealand ECE research and practice by demonstrating how dialogues with and about 2-year-olds actively contributed to a deeper understanding of learners in preschool settings. It also highlighted a series of effective pedagogies in these spaces. The intention was to investigate the different interpretations offered to understandings of ECE pedagogy when the dialogic efforts of teachers and 2-year-olds are held up for scrutiny. The insights generated from this project support teachers to re-vision their pedagogy in ways that are not only inclusive of the specialised needs of this younger age group but also support teachers to appreciate the unique contributions of 2-year-olds to the learning of older peers. As a result, teachers have built more effective mixed-age ECE contexts for all learners, and understand their central role as dialogic partners in these spaces.

This work highlights the importance of bringing together multiple polyphonic perspectives/voices in understanding young children. It illuminates the important shifts teachers can make when they are invited to “see” and examine their practice through critical, collaborative, visually inspired dialogues about dialogues. The findings offer significant challenges to existing assessment practices that seek to interpret learners based on limited “seeing”; on assertions on their behalf concerning interests; and on narrow visual and theoretical fields. The findings also challenge assessment practices that orient to older age groups and give primacy to certain dialogues over others, often at the expense of 2-year-olds’ learning. Importantly, these findings act as a provocation to all teachers who claim to know 2-year-olds, or any other learner for that matter, without paying careful consideration to their priorities as learners. Implicit within these discoveries lie the provocative nascent dialogues that take place beyond the “eye” of teachers in the dialogue. Seen or unseen, these play a vital role in learning and are heavily implicated in the preschool space for their central role in learning for 2-year-olds alongside their older peers.

Limitations of the research

- Highlighting phase 2 findings does not give full justice to the earlier, iterative phases of this research that led to the outcomes in this report. The many hours spent by teachers in understanding their 2-year-olds required a deep commitment and extensive funded non-contact time for teams (as opposed to individual teachers).

- Due to the small number of 2-year-olds and ECE “preschools” under scrutiny, we do not claim that what was discovered holds true for all 2-year-olds (although we suspect that there are likely to be similarities for children at a similar developmental period of their lives).

- Due to constraints in time and space we are aware that we have only looked at frequencies within dialogic events and not durations. We intend to publish on durations separately, as they add to the picture.

- The video equipment at our disposal meant we couldn’t always access certain spaces simultaneously. Even if we had managed to capture every visual field across all three cameras, it is naïve to suggest that what was “seen” can ever represent truth. A central premise of this study has always been that there are not only limits to seeing, but that seeing is a visual encounter with what is and can be seen. “Seeing” is deeply connected with the work of the subjective “I”. What we do claim, therefore, is that when insights from seeing are shared and carefully scrutinised, these have the potential to radically alter practice.

- Staffing changes across both sites in the first year of this study caused some instability; however, this was resolved once a more stable team was in place, reinforcing the importance of structural features of quality ECE for effective learning dialogues.

Footnotes

- These settings traditionally provided for 3- and 4-year-old learners only—hence the term “preschool”, which is used throughout this report. ↑

- Even though their licenses did not preclude the enrolment of 2-year-olds, kindergartens have typically tended towards single-age provision with 3–4-year-old “pre-schoolers” on the basis that children of the same age can be more educationally challenged by their same-age peers. ↑

Acknowledgements

The researchers would like to thank the University of Waikato and the Wilf Malcolm Institute of Educational Research for supporting this project, and the Teaching and Learning Research Initiative for funding it. Most importantly we would like to thank the 2-year-olds, their families, and the teaching teams from both ECE services (including teachers no longer present who played a role). Thanks to RMIT University, Melbourne, who generously provided the necessary time for the lead researcher to complete this study while in Australia (and travelling back and forth) during the last 8 months of the project.

References

Bakhtin, M. M. (1986). Speech genres & other late essays (No. 8; V. W. McGee, Trans.). Austin, TX: University of Texas.

Bandlamudi, L. (1999). Developmental discourse as an author/hero relationship. Culture & Psychology, 5(1), 45–65.

Benner, P.E. (1984). From Novice to Expert: Excellence and power in clinical nursing practice. Menlo Park, California: Addison Wesley.

Birigen, Z., Altenhofen, S., Aberle, J., Baker, M., Brosal, A., Bennett, S. & Swaim, R. (2012). Emotional availability, attachment and intervention in center-based child care for infants and toddlers. Development & Psychopathology, 24, 23–34.

Chalmers, D. (2016). Communicating with children from birth to four years. Oxon, England and New York, NY: Routledge.

Degotardi, S., Torr, J., & Han, F. (2018). Infant educators’ use of pedagogical questioning: Relationships with the context of interaction and educators’ qualifications. Early Education and Development, 29(8), 1004–1018.

Duncan, J., Dalli, C., Becker, R., Butcher, M., Foster, K., Lake-Ryan, S., Mackie, B., Montgomery, H., McCormack, P., Muller, R., Sherbund, R., Taita, J., & Walker, W. (2006). Under three-year-olds in kindergarten: Children’s experiences and teacher’s practices. Report prepared for the Teaching and Learning Research Initiative, New Zealand Council for Educational Research, August 2006.

Elfer, P. (2014). Facilitating intimate and thoughtful attention to infants and toddlers in nursery. In J. Sumsion & L. Harrison (Eds.), Lived spaces of infant-toddler education and care: Exploring diverse perspectives on theory, research, practice and policy. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer.

Hayashi, A., & Tobin, J. (2011). The Japanese preschool’s pedagogy of peripheral participation. Journal of the Society for Psychological Anthropology, 39(2), 139–164.

Georgeson, J., Campbell-Barr, V., Mathers, S., Boag-Munroe, G., Parker-Rees, R., & Caruso, F. (2014). Two-year-olds in England: An exploratory study. Retrieved from http://tactyc.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/TACTYC_2_year_olds_Report_2014.pdf Løkken, G. (2000). Tracing the social style of toddler peers. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 44(2), 163–176.

Mathers, S., Eisenstadt, N., Sylva, K., Soukakou, E., & Ereky-Stevens, K. (2014). Sound foundations: A review of the research evidence on quality early childhood education and care for children under 3. Implications for practice. Oxford, England: The Sutton Trust: University of Oxford.

Ministry of Education. (2008). ECE regulations. Retrieved from http://www.legislation.govt.nz/regulation/public/2008/0204/latest/ DLM1412637.html

Ministry of Education. (2018). 2017 early childhood education census. Retrieved from https://www.educationcounts.govt.nz/statistics/ early-childhood-education/participation

Morton, S., Carr, P., Grant, C., Berry, S., Bandara, D., Mohal, J., Tricker, P., Ivory, V. C., Kingi, T. R., Liang, R., Perese, L. M., Peterson, E., Pryor, J. E., Reese, J. E., Waldie, K. E., & Wall, C. R. (2014). Growing up in New Zealand: A longitudinal study of New Zealand children and their families. Now we are two: Describing our first 1000 days. Auckland: Growing up in New Zealand.

Ødegaard, E. E. (2006). What’s worth talking about? Meaning-making in toddler initiated co-narratives in preschool. Early Years: Journal of International Research & Development, 26(1), 79–92.

Papatheodorou, T. (2009). Exploring relational pedagogy. In T. Papatheodorou & J. Moyles (Eds.), Learning together in the early years: Exploring relational pedagogy. Oxon, England: Routledge.

Quiñones, G., Li, L., & Ridgway, A. (2018). Collaborative forum: An affective space for infant-toddler educators’ collective reflections. Australasian Journal of Early Childhood, 43(3), 25–33.

Rameka, L., Glasgow, A., & Fitzgerald, M. (2016). Our voices, culturally responsive, contextually located infant and toddler caregiving. Early Childhood Folio, 20(2), 3–9.

Recchia, S. L., & Shin, M. (2012). In and out of synch: Infant childcare teachers’ adaptations to infants’ developmental changes. Early Child Development and Care, 182(12), 1545–1562. doi:10.1080/03004430.2011.630075

Reynolds, E. (2008). Guiding young children: A problem-solving approach (4th ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Rockwell, E. (2008). Teaching genres: A Bakhtinian approach. Anthropology & Education Quarterly, 31(3), 260–282.

Rowe, S. M. (2016). Re-authoring research conversations: beyond epistemological differences and towards transformative experience for teachers and researchers. Cultural Studies of Science Education, 11, 183–193.

Rutanen, N. (2014). Lived spaces in a toddler group: application of Lefebvre’s spatial triad. In L. Harrison & J. Sumsion (Eds.), Lived spaces of infant-toddler education and care: Exploring diverse perspectives on theory, research and practice, (pp. 17–28). Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer.

Siraj-Blatchford. I. (2007). Creativity, communication and collaboration: The identification of pedagogic progression in sustained shared thinking. Asia-Pacific Journal of Research in Early Childhood Education, 3-23. Retrieved from http://scholar.dkyobobook.co.kr/ searchDetail.laf?barcode=4050025429632

Sullivan, P. (2012). Qualitative analysis using a dialogical approach. London, England: Sage.

V-note. (n.d.). V-note: Software for video annotation, markups, organization, collaboration, and sharing. Retrieved from https://v-note.org/ research

White, E. J. (2014). ‘Are you ‘avin a laff?’: A pedagogical response to Bakhtinian carnivalesque in early childhood education. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 46(8), 898–913.

White, E. J. (2016). More than meets the “I”: A polyphonic approach to video as dialogic meaning-making. Video Journal of Education & Pedagogy. Retrieved from https://videoeducationjournal.springeropen.com/articles/10.1186/s40990-016-0002-3

White, E. J. (2017a). Introducing dialogic pedagogy: Provocations for the early years. London, England: Routledge.

White, E. J. (2017b). Mikhail Bakhtin: Dialogic language and the early years. In L. E. Cohen & S. Waite-Stupiansky (Eds.), Theories of Early Childhood Education: Developmental, Behaviorist, and Critical (pp. 131–148). New York, NY: Routledge.

White, E. J., Ranger, G., & Peter, M. (2016). Two year-olds in ECE: A policy issue?. Early Childhood Folio, 20(2) 10–15.

White, E. J., & Redder, B. (2017). A dialogic approach to understanding infant interactions. In A. C. Gunn & C. A. Hruska (Eds.), Interactions in early childhood education (pp. 81–98). Singapore: Springer.

Wittmer, D. (2012). The wonder and complexity of infant and toddler peer relationships. Young Children, 67(4), 16–24.

Xiao, B. & Tobin, J. (2018). The use of video as a tool for reflection with preservice teachers. Journal of Early Childhood Teacher Education, 39(4), 328–345.

Research project team

Lead researcher E. Jayne White

Emerging researcher Bridgette Redder

Teacher partners

Shavaurn Bennett

Bev De Manser

Catherine Geddes

Caroline Hjorth Annette Rogers

Appendix 1

| 2-year-old’s verbal language | Verbal language used by 2-year-old, e.g., laughter, sounds, singing, words |

| 2-year-old’s nonverbal language | Nonverbal language form used by 2-year-old. Body movement, eye movement, pointing etc |

| Watch by 2-year-old | 2-year-old watches others inside or outside of the dialogic event |

| Teacher verbal language | Verbal language form used by teacher in response or as an initiation to 2-year-old |

| Teacher nonverbal language | Non-verbal language form used by “other” teacher in response or as an initiation to 2-year-old—body movement, eye movement, pointing, etc. |

| Peer verbal language | Verbal language form used by peer |

| Peer nonverbal language | Non-verbal language form used by “other” peer in response or as an initiation to 2-year-old—body movement, eye movement, pointing, etc. |

| Teacher demonstrate | Teacher actively shows 2-year-old what to do (includes role-model, defined as teacher/peer says or does something that can be copied by 2-year-old, e.g., showing them how to do something as opposed to instructing) |

| Teacher ignore or reprimand | Teacher notices what 2-year-old is doing and does not intervene or respond deliberately or teacher/peer tells 2- year-old off and/or redirects |

| Teacher narrate | Teacher verbalises what the 2-year-old is doing |

| Teacher talks of 2-year-old in third person | Teacher talks to 2-year-old either as if they are not there or indirectly, e.g., uses their name in address such as “Jayne will wipe Bridgette’s face” when Bridgette is standing right there |

| Teacher question | Teacher asks 2-year-old a question |

| Teacher instruct or suggest or offer | Teacher tells 2-year-old what to do. This may be one instruction or a series of instructions, including “use your words” and “listen to my words”, or teacher suggests an lternative or way forward—body often as a provocation |

| Teacher interpret for peer | Teacher interprets the meaning for child (peer), e.g., “Patrick (2-year-old) wants you to open it.” |

| Teacher interpret for teacher | Teacher interprets the meaning for another teacher |

| Teacher interpret for 2-year-old | Teacher interprets the meaning for 2-year-old |

| Peer demonstrate | Peer actively shows 2-year-old what to do (includes role-model defined as peer says or does something that can be copied by 2-year-old, e.g., showing them how to do something as opposed to instructing) |

| Peer ignore or reprimand | Peer notices what 2-year-old is doing and does not intervene or respond deliberately or peer tells 2-year-old off and/or re-directs |

| Peer narrate | Peer verbalises what the 2-year-old is doing |

| Peer talks of 2-year-old in third person | Peer talks to 2-year-old either as if they are not there or indirectly, e.g., uses their name in address such as “Jayne will wipe Bridgette’s face” when Bridgette is standing right there |

| Peer asks 2-year-old a question | Peer asks 2-year-old a question |

| Peer instruct or suggest or offer | Peer tells 2-year-old what to do. This may be one instruction or a series of instructions. Will include “use your words” and “listen to my words” or peer suggests an alternative or way forward—often as a provocation |

| Peer interpret for peer | Peer interprets the meaning for another peer, e.g., “Patrick wants you to open it.” |

| Peer interpret for teacher | Peer interprets the meaning for teacher e.g., “Shavaurn wants you to open it.” |

| Peer interpret for 2-year-old | Peer interprets the meaning for 2-year-old |

| Subvert | Challenge or overthrow rules that demand they be obediently adhered to. |

| Agency | The 2-year-old exercises agency by taking control of the event and their own learning/or a leadership role in the event |

| Loophole | The 2-year-old deliberately alters the finalised meaning of their own prior words/actions as interpreted with other |

| Underground | The 2-year-old does or says something that is not necessarily approved of by teachers in the official discourse |

| Carnivalesque | The 2-year-old (with peers or on their own) mocks or de-thrones authority in some way |

| Intersubjective | The dialogue pulls towards shared meaning and consensus. The outcome will be based on “common ground” |

| Alteric | The dialogue pulls away from shared meaning and consensus. There is some form of “mismatch” (dissensus) between those involved. The outcome may be altered for either 2-year-old, peers, or adults as a consequence |

| Utterance chain | The event links to another event later or beforehand which gives it more meaning. |

| Open resource | Any resource that does not have a specific end-point—e.g., sand, playdough |

| Closed resource | Any resource that has a specific end-point or has to be used in a specific manner—e.g., brush-painting, books, food, felt pens. The 2-year-old may use a resource in a way that it is not intended to be used |

| Teacher only present | Only teacher in the event, no peers |

| Peer only present | Only peers in the event, no teachers |

| Group where teacher and peer are both present | Teacher(s) and peers(s) both in the event |

| Safety | Teacher intervention in an event for reasons of safety |