1. Introduction

This study began in the Spring of 2003, when we—the Canterbury Adult Basic Education Research Network (CABERN), an informal cross-sector network of local adult literacy researchers and practitioners—sent out a questionnaire. The questionnaire addressed potential respondents by asking: “Are you a tutor engaged in any aspect of adult literacy?” and the accompanying information sheet explained the main driver behind the research:

We began this particular project because we felt that, while there is a lot of talk currently on what adult literacy tutors should do, there is actually very little material available on what

they do do and why they do it; our project is an opportunity for tutors to tell their own stories. We want to continue the project on beyond this initial survey, and hope that anyone interested in further involvement in the research will let us know. (CABERN, 2003, Appendix 1)

Practitioners were interested, and the Teaching and Learning Research Initiative (TLRI) funding allowed us to extend the initial survey into a larger, exploratory project. We were interested in representing who adult literacy practitioners thought they were, not as they were defined by others.

2. Research aims and objectives

The research took place during a period of great change in the field. As part of the mainstreaming of adult literacy in Aotearoa New Zealand through the advent of the tertiary reforms, the “fragmented literacy sector” identified in 2000 (Johnson, 2000, p. 8) was (and still is) being actively reconstructed into a unified field of knowledge and practice, an endeavour occurring largely within government and its agencies or in response to its requirements.

The “talk” CABERN referred to in the initial information sheet quoted above was largely government discourse such as that signalled in the key policy statement of 2001, More Than Words: The New Zealand adult literacy strategy. Kei Tua Atu I te Kupu: Te mahere rautaki whiringa ako o Aotearoa (New Zealand Office of the Minister of Education, & Walker, 2001). The adult literacy strategy prioritised capability building among the adult literacy practitioner workforce, noting a necessary connection between increasing the professionalism, training, and support of tutors across the sector and improved learner outcomes.

But what was the baseline? “Real” practitioners were largely absent from More Than Words, and while a welcome flurry of adult literacy research and publication has occured since 2001 (e.g., Benseman, 2002; Benseman & Tobias, 2003; Doyle, Chandler, & Young, unpublished), until recently, little of this has revealed the adult literacy workforce. Much of the information we do have on practitioners has been focused on classroom practice or professional development and its impacts. In 2003, John Benseman was able to write that “Tutors are the cornerstones of the educational process and yet we still know very little about the people who teach in adult literacy programmes” (p. 9).

This project, then, was designed to fill a gap in knowledge. We anticipated that the project’s greatest strategic value in TLRI terms would be in its contribution to understanding the processes of teaching and learning in an underresearched field. We also felt it would be useful for discourse about practitioners—whether educational or political—to be grounded in evidence as researched by the nascent profession itself. Briefly we were interested in such things as the following: Who are adult literacy practitioners? What do they do? How and why do they do it? Would they like to do things differently, and if so what differences would they like to see?

Our research aims, in short, were to:

- understand more about the backgrounds, characteristics, motivations, and training of adult literacy practitioners

- understand more about the nature of their literacy practices in the various contexts

- understand more about their aspirations, their perceptions of positive and negative aspects of their practices and of the contexts within which they work

- explore the impact of such factors as class, gender and cultural background on the work of literacy practitioners

- contribute to the building of relevant research capacities in the field.

3. Research design

The CABERN project is a “basic interpretive and descriptive qualitative study” (Merriam, 2002, p. 6), its central concern to identify—and delineate the experiences of—self-defined adult literacy practitioners. The theoretical positioning of the researcher has been identified as a key area to cover when “aiming for credibility as generic qualitative research” (Caelli, Ray, & Mill, 2003). In CABERN’s case, the deliberately generic approach of the study has a pragmatic connection with the widely varying positions of the team members, allowing a diverse group to work together on the same project.

Although the majority of team members were practitioners and the research process encouraged self-reflection, the study was not primarily practice-oriented as is often expected of practitioner research. We would argue that there are other important approaches to research undertaken by practitioners, particularly in the context of professional change such as we found ourselves. Ivor Goodson (1999) has written that:

…we need to look at the full context in which teacher’s [sic] practice is negotiated, not just at interaction and implementation within the classroom. If we stay with the focus on practice

then our collaborative research is inevitably going to largely involve the implementation of initiatives which are generated elsewhere. That in itself is a form of political quietism.

By 2003 in Aotearoa New Zealand, a national qualification (ALEQ) was in development, a quality assurance standard (ALQM) in draft, and a professional body (ALPA) had just been established, all markers of the government engagement in “professionalisation”:

a direct attempt to (a) use education or training to improve the quality of practice, (b) standardize professional responses, (c) better define a collection of persons as representing a

field of endeavor, and (d) enhance communication within that field. (Shanahan, Meehan, & Mogge, 1994)

The timing of the CABERN survey, at this early stage in the professionalisation process, meant that practitioners might participate who would not necessarily “fit” within fully developed formulations of literacy practitioners and their practice, but who nonetheless understood themselves as belonging to this “collection of persons”. Rather than “better define” practitioners in an exclusive sense, the study was designed to present the range of their nonstandardised views on their “profession” and associated professionalism:

Practitioner A: I am not a tutor. I am a trained teacher with advanced specialised training.

Practitioner B: I like the fact that it’s a kind of line of work you can go into without necessarily being highly qualified and an expert at everything.

Participants

The survey was intended to reach as many practitioners as possible in as many different contexts as possible, including those currently located outside of existing networks.

The questionnaire was sent out to CABERN’s membership which included individuals (organisations could not join) from the local tertiary education institutions, or TEIs (Christchurch College of Education, University of Canterbury, Christchurch Polytechnic Institute of Technology), schools involved in adult literacy provision (Linwood College, Hagley Community College), local private training establishments, the Christchurch City Council, He Oranga Pounamu (mandated by Te Runanga o Ngai Tahu to develop health and social services for Mäori in the Ngai Tahu rohe), the Adult Reading Assistance Scheme (local member scheme—poupou— of Literacy Aotearoa), postgraduate students, a number of independent practitioners and researchers, and that also had links through its members with Literacy Aotearoa and the Adult Literacy Practitioners’ Association (ALPA).

Only one questionnaire respondent was from outside Christchurch, so we decided to focus on the local population. Using the questionnaire results, the CABERN directory of adult literacy providers (Boyd et al., 2002) and the Christchurch Library’s community database, as well as approaching Teachers of Promise (TOP) providers and other organisations, we initially estimated that, as at February 2004, there were 237 tutors involved in adult literacy in Christchurch, 197 of whom were currently practising. On this basis, our total 57 participants comprised almost a quarter of all tutors and 29 percent of those currently practising. In terms of workplaces, however, we had quickly discovered new locations for self-identified practitioners (such as the University of Canterbury) and we had not originally counted English Speakers of Other Languages (ESOL) tutors (five of whom chose to become involved at later stages in the project). We did not determine the extent of informal involvement such as that often occurring in Mäori organisations or on marae. Similarly, our survey did not include Te Reo Mäori tutors. These factors and others, the most important of which being that our population was indeterminate by design, and our sample self-determined, mean that we are unable to be

precise in establishing just how representative our sample was. Where other studies are available, however, similar trends can be discerned in a number of aspects (see following sections[1]), leading us to believe that with a few important provisos, our study produced a “snapshot” of those who identified as adult literacy practitioners in Christchurch in 2003–2004. What can be said from our rough attempt to determine the local population of practitioners is that the community sector was clearly underrepresented in our survey (24.56 percent of study participants practised in the community versus 82 percent of the population as estimated, and this latter percentage would be even greater if we had added in the Community ESOL tutors).

Research partnerships and collaborative process

CABERN entered the TLRI process as a pre-existing research partnership, formed in March 2000 as an informal local network of tutors, researchers, and other practitioners interested in adult literacy and coming from a wide variety of backgrounds and workplaces. The network functioned via a mailing list and a series of regular meetings.

Previous CABERN projects were undertaken by those who were able to participate, in effect a core subgroup within the larger network (Boyd & Canterbury Adult Basic Education Research Network, 2002; Boyd et al., 2002). The TLRI funding, however, required a legal entity with which to contract. Several of us were working within TEIs and it was suggested we could umbrella the project under an institution. This was in some ways an attractive option, allowing access to resources (the TLRI explicitly excluded equipment from its funding criteria), expertise, support, credibility, and time allocation as part of a job. To ally ourselves with an institution, however, would compromise CABERN’s status as an independent network and threatened to reinstitute the imbalance between practitioners and researchers that CABERN was founded in part to reject. The independence was precious and the product of constant tensions and negotiations; we all had affiliations to various institutions, philosophies, theories, and practices—within a fragmented field, it was paramount to maintain the group. We all constantly negotiated conflicts of interest. Our diversity was our strength, our raison d’être in many ways, but also our weakness.

The decision was made to formalise the network, and at the end of 2003 CABERN became an incorporated society. The move from an informal to formal group, a noninstitutionally affiliated group dealing with a formal structure, brought about its own challenges. The original intention was to have a research subgroup reporting back to the wider network. Perhaps

inevitably, we found the wider group got smaller. Most aspects of the project were undertaken within the core project team: project management, project support, design, and data collection, analysis, and writing up. Where work needed to be completed outside the team, our principle and process was to keep the work within the sector as much as possible; for

example, transcription of interviews was carried out by a business which provided literacy and numeracy tuition as part of their training arm (and whose literacy and numeracy tutor happened to be a participant in the research); one of the focus group facilitators was a committee member for a community literacy organisation; one interviewer had recently finished

her Master’s thesis, her topic in the adult literacy area. The research subgroup undertook different tasks according to interest, experience, and availability. For one researcher, for example, the focus on practice of the journal was especially attractive, in that it offered both the opportunity for self-reflection, and demonstrating to others the realities of working in adult literacy.

Research subgroup meetings and email communications formed an important part of the collaborative process, being the spaces where methods were discussed, tools designed and refined, and findings and research strategies considered. Findings from the initial questionnaire were fed back to all participants and an update and feedback session on preliminary findings was also held (Appendix 2).

Ethical considerations

Not being allied with an institution meant we had to develop our own ethics procedures and the associated documentation. Information sheets were provided to all participants prior to their involvement and consent forms were collected. No names have been used in the report but we were very mindful throughout the research process that we knew the identity of the participants and needed to be scrupulous with setting and maintaining boundaries. One of the project team, for example, was working for Skill NZ at the time and therefore restricted her involvement to activities not involving participants or their information. Although our policy was to allocate research roles that would not put people into inappropriate positions, for example an employer interviewing their employees, in a local survey anonymity cannot be guaranteed and some team members had to personally negotiate issues regarding confidentiality on an ongoing basis.

Data collection tools

Questionnaire

The project began with a brief questionnaire (Appendix 3) designed by the core team and finalised after feedback from members of the wider group. The questionnaire was designed to gather data on demographic details, nature of employment, length of involvement in the field, and training. Respondents were also asked to rank order a series of factors relating to

motivation for their entry into the field. An empty item was included here to allow respondents to identify their own priority factors. An open question designed to collect information on respondents’ definition of “literacy” used the government definition from More Than Words as a prompt.

The final version was distributed through the CABERN networks by email, post, and person, and was also available as a Web survey.

Focus groups

Four focus groups were scheduled at various locations and times intended to be accessible to practitioners.

The key questions for discussion were:

- What keeps you going as an adult literacy tutor?

- The positives and negatives of adult literacy work.

- What/how do you teach and where does the mandate for what/how you teach come from?

- What are the age, gender, background, culture factors for people with whom you work and how do you go about your work with people of a different age, gender, background, and culture to your own?

Invitations to attend a focus group were emailed or posted to questionnaire respondents who had indicated their interest in continuing involvement in the research and individuals and organisations identified in the baseline scoping exercise.

Potential participants were then sent information about the focus group purpose and process (Appendix 4). Participants who had not filled in the questionnaire were asked to provide background information. Each focus group was taped and notes taken by a note-taker. The facilitators were also asked to briefly document their reflections following the focus group

session (Appendix 5).

Interviews

In-depth semistructured interviews (see Appendix 6) were designed to collect detailed information relevant to our research aims that could be compared to other data already collected and yet to be collected (see next section). There were three main areas:

- “You (the interviewee) and your story as an adult literacy practitioner”, where interviewers were asked to encourage interviewees to construct their own narrative while also ensuring certain factors (such as entry into the field, training and experience, relationship to career and life goals, and gender, culture, and socioeconomic factors) were investigated.

- “Your conception of adult literacy”. For the purposes of comparison, this section again used the government definition as a prompt.

- “You and your practice”. This section used an adaptation of the Critical Incident technique (Brookfield, c. 1995) to structure reflection on recent practice.

Potential interviewees were identified from those who had already participated in earlier stages of the research and indicated their interest for continuing involvement and those identified in the baseline survey who had expressed interest but not yet been involved.

Potential interviewees were then sent information about the interview purpose and process. New participants were asked to provide background information. The interviews were recorded (Appendix 7) and interviewers took notes.

Practice journals

The practice journal (see Appendix 9) was a combination logbook—using a template to document the activities engaged in by the participants—and reflective journal, that used the Critical Incident technique already introduced in the interview. The journal-keepers were interviewees who had expressed interest in documenting their practice, and they did so for a fortnight. As we were interested in what tutors actually did, they were asked to include all activities, not just those in the classroom—including staff meetings and planning, for example.

Evaluation

In order to evaluate the extent to which our study contributed to building capacity and capability, members of the project team, and a small group of other participants, were surveyed by phone and email (Appendix 8).

4. Findings

As already indicated, the project had five aims. In the first place, we wanted to understand more about the backgrounds, characteristics, motivations, and training of adult literacy practitioners. Secondly, we wanted to understand more about the nature of adult literacy practices and how practitioners perceived these practices in the various contexts in which they worked. Thirdly, we wanted to understand more about practitioners’ aspirations, their perceptions of positive and negative aspects of their practice, and of the contexts within which they work. Fourthly, in the course of our investigations we hoped to explore the impact of such factors as class, gender, and cultural background on the work of literacy practitioners. Finally, since it was anticipated that practitioners would be involved at all stages of the study, we hoped that the project would contribute to building relevant research capacities in the field. The findings in relation to this aim are discussed in a later chapter (see “Contribution of project to building capabilities and capacities in the field of adult literacy”).

Overall, we had little success with our fourth aim of exploring the impact of such factors as class, gender, and cultural background on the work of literacy practitioners. Our other aims, however, were achieved and this section of the report discusses the findings of the study in relation to each of these other aims. It draws mainly on data from the questionnaire survey undertaken in 2003 and from the focus groups, interviews, and practice journals completed in 2004 (Sections 1–3 below).

1. Background, characteristics, motivation, and training of adult literacy practitioners

In the first place, as stated above, we wanted to understand more about the gender, ethnicity, age, length of involvement, motivation, and training of adult literacy practitioners in the region. As participants entered the study, we collected demographic and career data. For greater detail, we drew on data from the original survey and the interviews with practitioners.

Gender, ethnicity, and age of practitioners

Gender

The overwhelming majority of practitioners (91 percent) were women. This finding is in keeping with Benseman, Sutton, and Lander’s national study (Benseman et al., 2006, p. 30).

Ethnicity

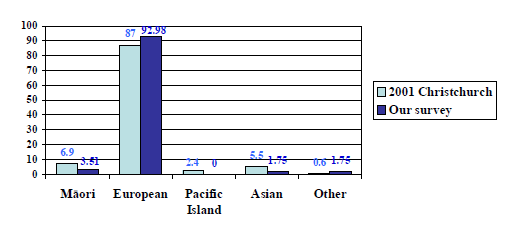

Ethnically or culturally the vast majority of practitioners identified themselves as Päkehä/European or “New Zealander”. The 2003 national study also found the (adult) literacy, numeracy, and language (LNL) workforce to be predominantly Päkehä or European (Benseman et al., 2006, p. 30). In Christchurch, 76 percent identified themselves as Päkehä/European, 7 percent as “New Zealander”, 2 percent as Mäori and, 2 percent as Mäori/Päkehä. Two percent did not state their ethnicity, while the remaining 11 percent identified themselves as Dutch, English, Filipino, and Irish.

As compared with the Mäori population of Christchurch at the 2001 Census, Mäori seem to have been significantly underrepresented among adult literacy practitioners. Moreover, there were no practitioners who identified themselves as Pasifika.

Figure 1 Ethnicity data

Rough comparison Christchurch City 2001 and survey data 2003-4

Age

The largest age group was 50 to 59 years of age (44 percent). Seventy-nine percent of practitioners were over 40 (in the ALAF trials this proportion was 65 percent (Benseman et al., 2006, p. 31)). Twelve percent were in the 30–39-year age group, 21 percent were 40–49, 12 percent were 60–69, and 2 percent were 70 and older (one participant). None was younger than 30.

The five men in the survey were aged between 40 and 59. Nine percent of practitioners did not state their age.

Length of involvement in adult literacy

Fourteen percent had been involved for less than one year and 9 percent had been involved for 15 years or more. The median period of involvement was between two and five years (23 percent of the total), while 16 percent had been involved for between one and two years and 35 percent for between six and 14 years. The proportions compare with the ALAF trials sample as

follows: approximately 30 percent had less than two years’ experience compared to approximately a quarter of the ALAF sample, 44 percent had been working for over six years compared to about a third, and 2 percent did not respond compared to 20 percent (Sutton, 2004, p. 35).

Motivation

Questionnaire: reasons for entry into the field

Questionnaire respondents were asked to rank order a series of options according to their importance as reasons for the practitioner’s entry into adult literacy work (1 = most important). An option for “other” was included so respondents could describe and rank their own reasons.

The four most commonly ranked reasons were: “I enjoy working with adults” (28 respondents, average ranking of 2.25); “It was/is something worthwhile which I can do” (26 respondents, average ranking of 2.65); “I enjoy working with young adults” (24 respondents, average ranking of 2.75); and “Adult literacy fascinates me” (20 respondents, average ranking of 2.85).

Fourteen respondents chose “I needed a job and a position in this field was offered to me”, with an average ranking of 3.64. Twelve respondents chose “I wanted to move from teaching children to teaching adults”, with an average ranking of 3.25. Ten respondents chose “By chance”, with an average ranking of 4.4, and nine chose “The part-time nature of the job”, with an average ranking of 3.66. Ten repondents also listed other reasons; these included two practitioners who entered the field due to family members with literacy needs and two with an interest in specific learning disabilities. Most comments glossed other rankings, for example: a practitioner who had chosen “chance” wrote that:

Over a year ago I went to a public meeting. I had no idea that that one meeting would change my life and I would be where I am today. But the manager of Christchurch Supergrans saw in me what I did not. She knew that the position that I hold now, would be perfect for me. I must say that this lady is right.

Another explained that: “I am an adult who needed extensive tutoring to help me gain confidence and ability in academics.”

The following sections draw on the interview data to outline some of the key themes. The interviews opened with a question focused on practitioners’ reasons for their involvement in adult literacy. Interviewees responded in a variety of ways and at a number of different levels and none of the interviewees attributed their involvement to a single factor.

Love of reading

Several people saw their own personal love of reading as leading them into adult literacy work. One interviewee said that she had become involved almost by chance. However, she goes on to say that she has always loved reading. In this respect she sees herself as:

…one of the lucky ones, English has always been my thing … that’s how I scraped through Bursary, on my English marks… I love teaching … reading and language … and things like that.

Other interviewees also expressed a love of reading. One expressed it in the following terms:

I just love to read all the time…. I love books and I just love the thrill of reading and what words do, and beautiful phrases and similes and metaphors and that, and the magic that

they produce I just love, and I can’t imagine not having that in my life.

And others said:

…. I love reading. As a child I could read before I went to school … and then I used to be such an obsessional reader… So I really liked reading, and … it sort of really upset me that

other people I knew at school, or had been to school with, they couldn’t read.

I enjoy reading myself. I’d hate to not be a reader … so I thought it’s not a bad way to help people.

Love of languages

Some people saw their involvement in adult literacy work as arising out of their love of languages. One interviewee said that he had always had a love of languages—at least from his intermediate school years when his interest in words and their origins led him to develop his own personal dictionary or notebook—a practice he maintains to this day:

When I taught at secondary schools they … laughed at me because I always had the reference dictionary from the library under my arm. At university I studied Latin and Greek… I’m

interested in the origin of language … and [now] I’m also studying Hebrew.

Love of learning

Some people saw their involvement in adult literacy work as arising out of their love of learning:

… just like a … thirst for learning … for knowledge and finding out things … and always reading and sort of thinking about things. Yeah, it’s that whole literacy for the family.

One of the practitioners said that what he enjoys about adult literacy is the fact that it is rich in the unexpected and the breadth of learning:

That’s what literacy is about. It’s about … participating in life I think. That’s what I enjoy about it because you can prepare, but you can’t prepare, you know. So from one day to the next you don’t know what’s coming up. And that’s what I like about it, really.

Love of working with and/or helping other people

Some interviewees saw their involvement in adult literacy work as arising out of their love of working with or helping other people:

It’s the love of working with people I think … and helping them along with whatever they want to learn really. So that was my main motivation and still is. It’s something that I really

wanted to do.

…it’s the love of working with people I think … and helping them along with whatever they want to learn really. So that was my main motivation and still is.

…there’s kind of that desire to work with people on their learning… But to not actually be a (traditional) teacher…

Wish to do something about a social problem

Some practitioners said they became involved in adult literacy work in order to do something about a social problem which they saw as important or serious:

For many years I’ve been concerned at the number of Mäori men in prison and I thought if I could help them to read and write, maybe they wouldn’t end up in prison…

…I’m really quite passionate about empowering people and I think that these skills are so important to them being empowered.

Interest in other cultures and a wish to get to know people from other cultures

Some people said that they became involved in adult literacy work partly as a consequence of their interest in other cultures:

I really came into it through ESOL… At that time a lot of Somali people … first came into Christchurch, and I saw these people you know with a little piece of Africa here, and I thought,

how can I get to know these people?

Influences of family and particularly parents

Some practitioners attributed their involvement in adult literacy work to the influence of family and particularly their parents and caregivers. In some cases this was seen as influencing them to become involved in education or as teachers in general:

My family has a long tradition of involvement in education. In particular my father influenced me to become a teacher.

…my mother was a teacher. My father had big ambitions for all his daughters to be teachers but none of us became teachers—except one. He succeeded with one… No … I wouldn’t say I have any particular background.

In other cases the influence was more specifically focused on their involvement in adult literacy:

I think just my family background and discussions with my mum sort of helped me … my mum is very involved in the field of adult learning so it was kind of [natural]. I’ve just had so

many discussions with her in the past and … all the time about the issues, especially literacy… It all just … really inspiring.

Finally, there were other cases where the influence was both general and specific:

I come from a family who have a background of teaching. My father was the Director of the Reefton School of Mines, and part of his duty was to teach miners for the certificates they needed, and that really also involved literacy because many of them had very little schooling. It involved teaching from a very basic level, right up to university level… I also have an older sister who’s a teacher. I vowed and declared I’d never become a teacher, but that’s what happened. I trained as a secondary teacher, and I enjoyed my first year’s teaching.

Personal experience of reading difficulties or unhappiness at school as a young person

Some people saw their involvement in adult literacy work as arising out of their own personal experiences of failure and their negative experiences at school:

I was never a very good reader myself…

The other thing … is the fact that I never particularly enjoyed school myself. I think that’s probably why I have that sort of abhorrence of really controlling teachers.

Reading difficulties in one’s own family

Some practitioners attributed their involvement in adult literacy work to their direct experience of living with someone in their family who had reading difficulties. In some cases this was a parent:

My mother left school at Standard Five and went straight into a workroom, and I feel she always regretted that she didn’t have more schooling because she struggled… She always had a spelling book beside her. She wanted to be very correct, but she didn’t trust her own judgement … it was a struggle.

For others it was a sibling or husband or wife or a member of their partner’s family who had difficulties:

I had a sister who struggled with her reading… I thought it’s not a bad way to help people.

…my older sister who is, I would say, a slower learner … I think that there was a feeling of she was going to be my first student.

I had always been interested in how people learn and hence perhaps my background in psychology… [However] I married into a family that has a lot of learning disabilities in it, specific learning difficulties in it, and so of course I got more and more interested.

…my first husband couldn’t really read and write when I knew him. He used to get me to read a book and then tell him what was in it…

And for others it was a child or children of their own who had difficulties:

…after my children were born I helped them with their English and I sort of realised that this is what I enjoyed doing … then my third son had severe disability problems, dyslexia,

learning difficulties. So I got … very interested then, in how to help him and I started to look into people who need help with literacy, and then I went to ARAS and I started to meet people who were really intelligent but who weren’t reading, and it really interested me because this was also similar to my son, you know. I thought, ‘Hell, you know, I could see he’s

bright, very highly intelligent but he’s just not reading and the school was saying something different.’ That was the beginning of it, yeah.

…when my own children started to go through the educational system, I became aware that the three of them were very different. I became, I guess, aware that one size doesn’t fit all.

Experience as a migrant

Several interviewees said that it was their own experience as immigrants that had led them to become involved in adult literacy and particularly in ESOL work. They felt that they could identify with other people because they could understand what they were going through:

…because I’m a migrant I can relate and … feel how migrants have tried to survive and have tried to struggle to keep their identity. I wanted [them to keep] their identity but [also to be

able] to stand up and say, ‘Hey, I can speak English and I can understand you.’ So that was how I felt when I got involved and [that is how I feel today].

I think I can understand them very well because I know where they come from, and if they struggle with the language or with the culture, I’ve experienced it first hand too. So

sometimes you can use it as an excuse of course, but at least I can … explain language to them … and I can say to them, ‘Well this is the rule … this is how it works…’

Experience of teaching or working with young people struggling with literacy related difficulties

Some practitioners said they became involved after becoming aware of the reading difficulties faced by many young people. As we have already seen, this happened for one person when she became involved with her own children. For another it happened when she became chairperson at her daughter’s school:

I became interested in adult literacy … when I was Chairman of the Board of Trustees … at my daughter’s primary school. We did a bit of research on the kids that were having trouble reading. And what we found was that most of their parents had trouble reading too. After that I was talking to a friend who was a trained teacher and she did voluntary work with ARAS and she said to me, ‘Why don’t you go? If you feel like helping out and making a difference then why don’t you try that and go along to ARAS?’

Another respondent who was a secondary school teacher whose main teaching subject was French said that she became aware of literacy issues when she was called on to teach fifth form kids who were struggling to achieve anything academically:

I was teaching French … I had some of the top classes. [However] I [also] had [some of] the lower … Fifth Form English classes… They all wanted to sit School Certificate [but] weren’t

able to do so. They would ask me why they weren’t doing the same work as the higher classes, and in the end I had boys of 15 weeping on my shoulder because they couldn’t do anything. So I got out of teaching … and I thought I’d better find out more about that. I was already … doing a social work course, so I got a job and I qualified in social work. And

after I married I picked up again my skill at music teaching, and then I saw this SPELD course advertised. So I did that, but it was mainly directed towards small children sevens, eights, nine to eleven and I wasn’t working with these children. I found that I really preferred the older children who were at secondary school, and the adults who came along

because these people were more motivated.

Changes in career and/or personal circumstances

Some respondents were employed as adult literacy practitioners, while others were involved as volunteers and were not paid for their work. Changes in personal circumstances seem to have had an influence on practitioners in both situations.

For some people, voluntary work in adult literacy had led to paid employment and increasing levels of involvement:

Voluntary work led to an offer of a part-time (10 hours a week) paid job as a tutorial assistant at another agency and that led on to a full-time job.

Others became involved in voluntary adult literacy when they retired:

I’ve been teaching adults for the last 35–40 years as a Nurse Educator Administrator, but when I retired I thought, ‘Well I could do something with adults.’ I saw an advertisement for

training … so I rang up and enquired and started… It’s something I can do in my spare time… I’ve got quite involved. …as I say, I have always been teaching adults, and I enjoy working with adults [but literacy work was something new when I retired].

In the case of those in employment as adult literacy practitioners, one interviewee became involved in ESOL following a long career in primary school teaching leading eventually to burnout and a change of direction:

…I was a primary school teacher, and after 25 years of teaching and doing a lot with literacy because I taught mainly young children, I decided that the time was right for me to take a break, having suffered from burnout. So I then did some voluntary work, and helped in ESOL classes at the polytech. Then from there became a home tutor, where I was helping new migrants who didn’t have much literacy in English. Then I was asked to come and work for the home tutors, and so I started working as a trainer, teaching adults how to teach English to new migrants. From there, I did a diploma in TESOL (Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages) and now I’m the principal co-ordinator of the scheme here in Christchurch.

Others became involved following family illness:

I really came into it through ESOL first, and how I got into that was, I used to work in the library, but anyway my oldest daughter got very sick and I had to leave work. So I was … thinking about a new career move…

…At the time [I first heard about literacy problems] I wasn’t working because … [my daughter] actually had leukaemia at the time, and my husband had just passed away… [Following a friend’s suggestion] I went along to ARAS, did their course and did some voluntary tutoring which I loved, and then saw a job for [an adult literacy tutor] advertised and I thought, ‘Oh well I could get paid for this maybe’, and I went along and did a bit of tutoring for them.

When I left school I trained as a primary teacher … and I’ve always worked in some way with children and reading and writing and speaking … got into the way of helping children who had reading problems. [Eventually because of family illness I took a job as a tutor in an employment programme.] …then after five years I applied for a job as a [literacy] tutor at a newly opening public programme, got a job as a tutor, and then after a year … became a coordinator. I’m now moving out of administration back into tutoring literacy with adults.

One interviewee emphasised the continuity between her previous work as a primary school teacher and her work in adult literacy:

I went back to teaching when my youngest son went to Intermediate; I did quite a lot of part-time work for a start, and as is the nature of part-time work, you get landed with a lot of classes who are not easy. And then I had another period of chopping and changing schools. And then I saw an advertisement for training leading to a diploma and a position working with students with learning difficulties in a private sector centre. I work largely with teenagers and adults, I work quite a lot with university students, polytech students and some business people who want to do further training.

Another person said they became involved in adult literacy after being made redundant:

…about eight years ago, after being made redundant … I was looking around for alternative work and spotted [an advertisement for an adult literacy job]. The idea of that type of work

and the short hours … really suited me.

Stimulated by personal studies as an adult

Some people saw their involvement in adult literacy work as arising in part out of their own experiences as adult students. One person explains this as arising because she found the experience—a long hard struggle over many years—so rewarding in the end that she became involved in helping other adults educationally:

[I did my 7th Form English and then] it took me 11½ years but I did a BA in English and graduated two years ago. So that was, once again, a continuation of the love of literature, the love of words. I didn’t know if I could do it. I lived from paper to paper, but your confidence builds as you do it, and I was doing a full-time job at the same time. So it was burning the midnight oil, doing assignments at 5 am in the morning and reading morning, noon and night and lunchtime and carrying your books to work and all of that, but paper by paper, I got it and it was such a rewarding experience.

Another interviewee said that her involvement arose out of a research project she did at varsity.

[I had no previous relevant work experience but] … I knew about ARAS because for one of my adult education papers I had to do a research project … [which involved finding out all the places in Christchurch that had all kinds of programmes and ringing them up and finding out their fees and how many people were teaching and what they taught and all that sort of thing … And I interviewed … and really enjoyed hearing about what she was doing and thought to myself, ‘Well when I’m free I will go back and do that.’ So I rang up and waited for the next course and got accepted … and then did the three months tutor training and started being a tutor over a year ago.

For another person:

…It kind of all started when I decided to go back to university to finish my degree, I [did a] paper on Adult Learning … and that got me really interested in … adult learning…

So that’s what inspired me about working with adults.

Personal contacts with an adult literacy tutor or co-ordinator

Some practitioners became involved in adult literacy partly as a consequence of informal personal contacts with others who were involved:

[As a migrant] I first heard about the ESOL Home Tutor Scheme from a friend—in fact from the mother of my daughter’s best friend. I then became involved with the scheme as a tutor.

I heard about it [the adult literacy tutor position] through my mum, and just sort of started there.

The woman who used to run a programme was a friend of mine and she asked me if I would be interested in being a tutorial assistant. [This led to a part-time job.]

After [being involved with some research on reading difficulties at my daughter’s school] … I was talking to a friend who was a trained teacher and she did voluntary work with ARAS and she said to me, ‘Why don’t you go? If you feel like helping out and making a difference then why don’t you try that and go along to ARAS?’

Flexibility and part-time nature of much adult literacy work suited some people

Some practitioners were attracted into adult literacy work at least partly because of the flexibility and part-time nature of much of the work. One participant said:

…the idea of that type of work and the short hours etc., etc., really suited me.

I … was still working on my degree … a four-hour-a-week part-time position [as a tutor in an adult literacy programme] came up and this was great… [Because I wanted to look after my small children] I wasn’t looking for a full-time job.

I started doing 10 hours, just helping people in vocational settings and I’m still doing that today … and I like the part-time nature of the work. It allows me time to spend with my family and do my other teaching.

Chance

Finally, chance played a part for some people. Some saw their involvement in adult literacy work as partly fortuitous. They had stumbled into their adult literacy involvement. Comments included the following:

I suppose I kind of drifted into it but…

I fell into it accidentally, relieving for [a colleague] in tutoring this course. …Before that I was a primary teacher.

I saw an ad … it just looked interesting.

Training for adult literacy practice

All participants entering the study were asked: “What training have you had that is relevant to your current tutoring position?” Responses for all practitioners can be accessed in Appendix 10. The most common responses are summarised here alongside the 2003 ALPA survey results for comparison (Benseman et al., 2006). Fifty-three percent held a compulsory sector

teaching qualification (this compares to 45 percent in the 2003 ALPA survey) and 30 percent percent had a qualification in adult teaching or had completed some study in this area (37 percent in the ALPA survey held a qualification in adult teaching). A quarter of participants had training in or held an ESOL qualification (under 6 percent qualified in the ALPA survey); 21 percent had an adult literacy teaching qualification or had studied in the area (just over half the ALPA respondents); and 21 percent were trained or qualified in the areas of Specific learning Disabilities (6 percent of ALPA respondents had completed SPELD training). A further 21 percent cited their teaching experience (compulsory or adult sector). Twenty-six percent held an undergraduate qualification and 16 percent either held a postgraduate qualification or had done some study toward one (approximately half of ALPA respondents held university degrees).

A more detailed picture was available through the interview data. Interviewees were asked how they had learnt their adult literacy practice. The value placed on formal initial teacher training, other forms of training for adult literacy practitioners, and on-the job experience varied widely. Many interviewees said that much of their learning had been on the job. However, this on-the-job learning was frequently complemented by nonformal learning, formal training, and a wide range of experiences in their families and in other work and voluntary situations. A number of interviewees said that they had trained as primary teachers and a number had trained as adult literacy tutors through ARAS.

The following summaries provide a picture of the variety of learning and training received by interviewees:

- No formal training, attended 3-month course for volunteers—also did an adult education paper as part of her BA.

- Trained as primary school teacher, worked as a volunteer, completed diploma of TESOL. y Volunteered as a home tutor, completed postgraduate diploma in TESOL. Feels disadvantaged because she doesn’t come from a teaching background. Because of this she states: “I’d had to make it up or learn it as I went along.”

- Has background in psychology—worked in psychiatric hospitals. Internal training programme in place where interviewee works.

- Did internal training with ARAS where interviewee initially trained. Has TESOL certificate. y Has “been involved for many years … was trained as an adult literacy tutor in the 1970s [and] has lots of experience”.

- Her “initial teacher training in the Philippines was important” to her. There she learnt to work with all age groups. Her experiences as an immigrant taught her a lot about working with other migrants.

- She “learned about the job as I went along”. Her “family, and specially my mum have been very influential, with frequent conversations and discussions”. From family had “gained a passion and thirst for

learning [and] also empathy for others”. —“I think having empathy with people and not wanting to impose. I think that that’s a really important skill to have with adult learners, to find out where they’re at, where they want to go.” She feels that failure or unhappiness in initial schooling may help some practitioners to empathise with people struggling. - Other than initial training as a volunteer tutor, “I’ve had no training, it’s all been on the job.” Previously employed for about six years as a receptionist at a polytechnic, where she had “lots of experience in working with [a variety of] different people”—“I had a lot of experience with people [including] people with all sorts of disabilities, as well as working with second language people—I’d had a lot of experience working with people and that’s what has pulled me through my inexperience in the lack of curriculum knowledge. And so sort of seeing where somebody might be needing assistance, not actually knowing what to do, but having an instinct about what would…”

- “On the job, thrown in the deep end”—had previously worked as a primary school teacher and received primary teacher training, currently studying for Graduate Diploma in Literacy Education through Massey.

- Did internal training programme for volunteer tutors run by ARAS, “then, yes. That was the start.”

- Started national literacy training programme provided by Literacy Aotearoa but did not complete. Did the internal training programme with ARAS—has also worked as a nursing educator for 35–40 years. While completing PhD, helped foreign students with their English.

- On the job—“I have to say that I’ve learnt the most at the coalface.” “Formally, I’ve done a Certificate in Adult Teaching at the College of Education.” Has also had training in other related fields, e.g. counselling—“I did quite a lot of counselling courses over the years that I was first here because I believe it should be dealt with holistically… In my experience once you start dealing with reading and writing and maths problems, then other things start to surface.”

- Has had formal training at the centre where she works. It has a programme to train their tutors—“They work with children, young people and adults with specific learning difficulties. They’re in the process of redefining their qualifications at the moment, going through NZQA.” Important informal learning going back many years from prior contact with young people including her own young children, each of whom was very different. She says that formal training has reinforced her belief in “the importance of trying to understand the specific difficulties experienced by people and the ways in which these impact on their lives, and then designing programmes to address these difficulties”.

- Trained as a teacher in the Netherlands. However, most important learning had been on the job. Previously worked at an alternative high school where he dealt with kids from very different backgrounds—“We worked in groups all the time … we didn’t have individual programmes … [our] programmes were for groups of five students within a 25-group setting. So you really had to be on the ball as to how all the groups were working. They were working on the same topic but were doing different things. So that’s where you learn a lot about how to work with different backgrounds, different levels and different needs all the time… It was good, you know, I’ve learnt all the tricks I know now I think. Most of the tricks I learned there. Because you had to deal with kids on the spot… Yeah, a bit of a challenge, but hard work. Yeah, but I mean you learn a lot about yourself as well … you were thrown in the deep end, but we worked in a team as well… And that’s the same here. So I’ve [done] literacy [work] from one to one, to small groups and to bigger groups. That’s basically one of the things I have done over the years because the organisation I was working for worked one on one, you know, when I started off.”

2. Adult literacy practice

As noted above, we wanted to understand more about the nature of adult literacy practices as they were perceived by practitioners in the various contexts in which they worked.

Following a brief description of the contexts within which the practitioners in our study worked, this section describes in some detail adult literacy practitioners’ perceptions of their learners and the nature of the tasks which they perform. It also provides a detailed description and analysis of adult literacy practice together with descriptions and reflections by practitioners on selected teaching sessions and some reflections on adult literacy as paid and unpaid work.

For this purpose we have drawn on data from the survey as well as from the practice journals, focus groups, and interviews.

Contexts of adult literacy practice

As participants entered the research, data were collected on the kinds of workplaces, types of involvement, and the types of employment of the adult literacy practitioners. (Percentages have been rounded.)

Workplaces

Almost a third of the practitioners worked in private training establishments (PTEs). Twenty-eight percent of PTEs were school-based, 9 percent of the total. Seventeen percent of PTEs were maraebased, 5 percent of the total. Nearly a quarter of the practitioners worked in the community (nearly 29 percent of whom worked in ESOL). Fourteen percent of the practitioners worked in TEIs, and another 14 percent for specialist adult and child literacy providers. One respondent worked in a corrections facility. Nine percent combined more than one workplace type. Nineteen percent did not state their workplace.

Types of engagement

Eighty-one percent engaged in one-to-one tutoring, 56 percent in group work, 34 percent in literacy within the context of another subject, 12 percent in workplace literacy, 10 percent as an administrator/manager, and 5 percent as “other”. Just over half of the participants (54 percent) had multiple engagements. The two most common forms were combining group and one-to-one tutoring (16 percent) and group, one-to-one, and teaching literacy within the context of another subject (12 percent).

Employment type

Twenty-eight percent of our respondents were full-time tutors, 60 percent were part-time paid tutors, 9 percent were self-employed (60 percent of whom were part-time), 21 percent were voluntary and unpaid tutors, however half of these also had full-time (1) or part-time paid work as tutors, and one more adding “other”. Seven percent in total gave their employment type

as “other”; this included those who were administrators or managers. Ninety-one percent of our participants received some form of remuneration for at least some of their work.

Who were the learners?

Here we draw on data from the practice journals. Practitioners were asked to describe the learners with whom they were working. These varied from centre to centre.

At one centre the practitioner reported that there were 15 learners whose skills ranged from middle primary to NCEA Level 2. She then provided information on four learners with whom she had worked over the period. The first of these was H who was female, 35 years old and European. She wrote: “I believe H is quite capable of reaching higher levels of competence than

she has been led to believe in the past. H’s written work had indicated she was ready to move on—her spelling was good, her ideas were coming more developed and she was interested in writing.” The second person, M, was male, 17, and European. The practitioner writes: “M has been 6 months on this programme, having moved from mainstream because of non-attendance due to bullying. He has difficulty concentrating for any length of time. Has been diagnosed with ADHD and Dystrophic and has been on Ritalin in the past.” The third person on which background information is given was S, also male, 22, and European. S is described as “studying NCEA Level 2 maths and Level 1 English through The Correspondence School. The maths is

fine—it is internally assessed and he is focused and returns his assignments regularly. English is a different matter—S has been assessed by SPELD and diagnosed as having a Learning Disability. His verbal communication and appearance indicate no such thing. He is articulate and well presented and can become a part of a conversation on almost any subject.”

At a second centre, the learners were described as generally young adults in their twenties. However, some were in their late teens, a few were under 18, and a few were in their thirties. There were more men than women and they included both Mäori and Päkehä as well as a few Samoans and Cook Island Mäori, and one Egyptian. It was noted that several students had

intellectual disabilities. At a third and fourth centre, the practitioners reported that the learners were adults and young adults 15 to 60 years of age, both male and female, New Zealanders, and various other nationalities (including Chinese, Afghan, Samoan, Filipino, and Russian).

At a fifth centre, the learners were described in the following terms: In one group, two Kurdish women aged in their forties (not literate in own languages, early development of literacy in English); two Afghan women aged in their twenties (not literate in own languages, early development of literacy in English); one Ethiopian woman aged about 40 (not literate, has little concept of literacy yet, very new to the country and in culture shock, malnourished but this is improving)—can copy words and letters with help; two Ethiopian men—one new to country and in late forties; has L1 (first language) literacy. The other, in his sixties, has been in New Zealand for 4+ years (has no literacy—is struggling but has good skills in oral communication) (very broken English but gets it across); one Somali woman in twenties (not literate in own languages, but very bright and learning fast). In a second group, four Afghan women (all in their

twenties with preschoolers who have not yet separated so must have lessons in crèche and all very new to the country) (seem to have a concept of what reading and writing is all about and seem to be learning fast); and one Kurdish woman (probably in her early thirties, has been in New Zealand maybe 2 or 3 years, recently shifted house which has unsettled her preschooler).

Finally, the ARAS learner was reported as being female, between 50 and 60 years old, married, with children and grandchildren, of Dutch origin but has been living in New Zealand for almost 50 years.

Reflecting on the tasks of adult literacy practitioners

In this section we look at the ways in which focus group participants described their own adult literacy practice and the kinds of things required of them and their colleagues as literacy practitioners.

Adult literacy work is not so much a technical task as a social one

Adult literacy work requires practitioners to be aware of the tensions that arise between teaching the basics of language and literacy and providing support for the whole person. The effective teacher requires both. There is a “technical” aspect of literacy teaching, but it is much more than that. One participant pointed out that:

…even though the people [you’re working with] can seem very different from you … there’s always quite a lot of things you have in common.

It is important to find and build on these common elements. Another person pointed out that practitioners need “patience … you’ve … got to be interested in their point of view”, and you have to have a sense of humour. One participant said:

…if all else fails just burst out laughing and say, ‘But we can’t understand what you’re saying.’ And that sort of breaks the tension, yeah.

It was also pointed out that it is necessary to provide time and space for people to talk among themselves about personal issues without themselves becoming “social workers”:

I think my job is more or less just trying to help people kind of open up and function effectively… It’s different from only teaching ESOL for sure.

I think it’s quite important that [people] do have somewhere [to talk about personal issues] and it’s good that they talk amongst themselves, to air those personal issues, because quite often they’re a barrier to learning … they come in with real [problems, and] they can’t learn anything unless they—you know, until they get rid of this.

I absolutely agree but I also don’t see my role as a social worker. I know there’s a fine line.

What I say to our tutors here is … if you sense the situation [warrants it] give them five or ten minutes and then talk about your role and what they’re here for … it’s amazing how many

people have … baggage which stops them learning.

Empathy and sensitivity were, therefore, seen by participants as critical aspects of effective practice.

Adult literacy work involves working with diverse people with a variety of skill levels and experiences

As we have already noted above, practitioners highlighted the fact that literacy learners varied widely in terms of their interests, expectations, and reasons for attending the programmes as well as in terms of their skills and abilities and background knowledge. This required tutors to address the needs and interests of each learner in a unique way. A wide range of resources to suit the interests of individuals was needed, and each individual had to be taught at their own level:

One of the main points in our philosophy is to tutor according to the need of the students … You have to sit down with a student, get a good rapport, and find out what that person needs, and then find out if some of the things you know about, work for that student. So, the mandate [really] comes from the student I suppose.

[We try to teach] every student on their own level … some of them can’t even speak a word of, [some have] never held a pen, [others] have finished school and have quite a bit of English. So we’re trying to teach everybody on their own level … within a group … it’s topic-based [teaching] but it’s called a literacy programme … and most people say they want to learn to read and write, quite a few of them speak English quite well … but some of them have waited 60 years to get in the situation where they can learn to read and write … it’s their mandate, ‘I want to learn to read and write’.

Adult literacy work requires practitioners to draw on learners’ experiences and their stories. But not always!

Adult literacy practitioners cannot merely draw on their own experience or on predetermined sets of exercises and tasks. They may well be able to use some of these, but they will have to be used flexibly and in such a way that they make sense to the learners. Participants pointed out again and again how important it was that practitioners draw fully on learners’ own experiences and their stories. However, they also pointed out that it was vital they go beyond these stories and that learners are challenged to go beyond the limits of their previous experience. They also pointed out that there were variations in the extent to which one can usefully and appropriately use learners’ experiences in teaching. One person said:

Well it depends how much language they have, because quite often they can’t talk much (in English) anyway. And quite often they don’t even … want to talk about … the past. They don’t want to be reminded over and over and over again about the horrors that—you know. You’ve just got to work from where they want to take it, if they don’t want to talk about it then you don’t talk about it. If they do want to talk about it then you talk about it, or write about it. And you know, you’ve got to respect their customs up to a point but then you’ve got to respect your customs too…

To achieve an appropriate balance, group work and a wide range of resources are essential:

Yeah, well and the topics come from either what the learners say they want to focus on or we can—because there are some people that have been there before and some new, sometimes we have to be a little bit autocratic, but we choose topics that are going to be relevant and useful and most urgently needed by the learners.

We teach individually and in a group… The basics, like vowels and that, we teach as a group cause we kind of think it’s good for everybody, even the more advanced people, to go back to the basics… Some of them were away [on the day a particular topic was taught] or whatever, and they missed out on it. Then each morning we have an individual session with each of our students, and the lower readers … get to read every day or, like, we’ve got someone doing an academic essay so there’s a wide spectrum that we [cater for].

There is therefore not any single right way or right approach to teaching and learning:

I think we … use as wide a range of approaches as possible. We try to be fairly kinaesthetic too. We use anything that works. We also [think] a lot about how to help people relax

and de-stress things so they’re, you know, not worried about whether they perform well or not, just to get them doing.

…we’re not into [any single approach to teaching reading and writing]; whatever is right is right.

Adult literacy and numeracy work is closely linked

Focus group participants referred at various points to the breadth of the adult literacy curriculum. In particular, several people highlighted the close and interdependent relationship between literacy and numeracy:

I probably came into literacy because I’m also very interested in numeracy and that’s been my field … but the more I learn the more I realise that they are very interrelated and we need the skills, we need the literacy rules I need for numeracy and the other way around and I guess this is another area that I’m interested in and the same kind of things happen. With the literacy, the confidence and working with people and learning more.

I’ve taught quite a bit of numeracy over the years with students and I’ve actually found that if they’re able to achieve something in maths, their self-esteem and self-confidence

[increase enormously]… It’s incredible, suddenly they find themselves better at spelling, better able to write. I think maths is a very powerful tool.

Adult literacy work requires practitioners to have the capacity to move beyond the tasks of teaching literacy and numeracy

We have already referred to the fact that literacy teaching must go beyond the narrow “technical” tasks of teaching reading and writing, that it may well include aspects of maths, and that it involves working with the whole person. Practitioners also called attention to the fact that the curriculum must go beyond reading, writing, numeracy, and so on, and that it must also include a wide range of social issues:

I find that we’re not just teaching literacy and numeracy; there are things outside of those boundaries that you always end up being involved with. Like, I know one of my students was having problems with WINZ…Though it had nothing to do with literacy… I knew a WINZ worker so we went at it together. So yeah, … it’s just a great big benefit for my students.

What do adult literacy practitioners do?

The descriptions of adult literacy practice provided in the focus groups and discussed in the previous section were elaborated on by those writing the practice journals.

The work of practitioners described in these journals consisted of two broad categories of activity: (a) teaching activities; and (b) other kinds of work. In both cases this includes some activities which took place regularly (i.e., on a daily or weekly basis) and some which took place occasionally or spasmodically.

Teaching activities

One-to-one teaching

Many activities took place on a one-to-one basis as tutors worked with students on their individual learning programmes.

One voluntary tutor worked exclusively in a one-to-one relationship with her student. This was for two hours a week. A second tutor said that she worked regularly on a one-to-one basis for periods of 15–20 minutes with individual students to provide help with each student’s personal needs. This could relate to spelling, reading, maths, writing, and so on. For about 50 percent of these periods the tutor said that she directed activity choice while students themselves made the key decisions in the remaining 50 percent of instances. While she was spending time with

individuals the other students in the group undertook their own independent learning as individuals or in groups. A third stated that she worked regularly for about seven hours a week with students on their individual learning programmes.

A fourth tutor provided a number of examples of work on a one-to-one basis. These included conversational English (grammar and pronunciation) with student doing clerical/computer course, maths re foreign currency calculations, metric system (area calculations) with student doing basic course in welding, learning styles, brain research findings, psychology, and career planning— addressing immediate needs/interests of a student and tying these in with learning and the outside world, form filling and drivers’ licence test, learning strategies for computer theory with one student doing clerical course—addressing individual need/interest in wanting to gain certification as a computer technician. “We analysed part of a chapter, listed main points and analysed the summary”, study skills, learning strategies, and looking at IQ test samples as used by army and police—demystifying the use and analysis of IQ tests as well as critically analysing the structure and content of the tests.

Small groups

Small groups were also used extensively for a multitude of purposes. One tutor described how she spent time regularly tutoring small groups (two to six) in such aspects as maths (Units 8489, 8490, 8401, and 8491) “for example, working on +-*÷ problems with words, reading tables and graphs, goal-setting, preparing and writing CVs and job application letters”. Small groups were also used by another tutor to work together with students on such things as spelling and phonics. A third tutor described various forms of work with small groups. These included: doing regular work in basic English grammar with three students in Life Skills course; driver’s licence theory with five students doing a computing course in response to individual requests; various maths unit standards and driver’s licence work with five students doing electronics as a response to individual needs/requests; etc.

Whole-group teaching

Whole-group teaching was also used in various ways and for a variety of purposes. On some occasions, the literacy tutor was in a classroom assisting another tutor with those students who were having some difficulties. One tutor described how he assisted students at theory sessions in an accountancy course taught by another tutor. He sat in on the sessions helping students with terminology, asking the tutor to explain certain things again, and helping some students with notetaking and explaining the meaning of some things himself. In other cases, tutors were on their own with the whole class. Finally, in other cases, tutors were part of a team or group who jointly taught particular sessions. Examples of these activities included a daily “getting started” activity at one centre, lectures, presentations and demonstrations on such topics as using a thesaurus on a computer and in a book, brainstorming sessions, exercises, quizzes and games (e.g., spelling and number games), meetings and social activities (e.g., ten pin bowling).

Note: Of course there was inevitably overlap between the various kinds of activities described above. More importantly perhaps, in many instances there was a high degree of integration between different kinds of activities. Not every activity could be identified exclusively within any single category and many activities formed an essential element within a wider framework. At one level tutors often designed activities of various kinds with the intention that learners would be able to move from one to another as seamlessly as possible. At another level it is of course the learners themselves who engage with their environments and the available resources including other learners and the tutor/s in the various one-to-one, small-group, and whole-group learning contexts.

Nonteaching activities

The nonteaching activities referred to were also wide-ranging. They included such things as the following.

Planning and resource development

This included planning, preparation, and resource development for teaching programmes on their own and/or with colleagues/students (e.g., meetings with other tutors, discussing plans with individual students, photocopying resources, writing quiz, updating workbooks, and so on).

Assessment and providing feedback on learners’ work

This included marking, proofreading of student work (including real letters applying for jobs and students’ CVs), assessment moderation, sorting/gathering/publishing student writing for end-of-year booklet.

Counselling and support of learners

This included contacting absent students (mainly by phone), planning with student/s, regular interviews with learners to ask them how it’s going regarding learning, other people, and so on, and what they’re thinking of doing next term/year.

Administration and liaison

This included general administration, record keeping and work on budget, dealing with emails and correspondence, writing reports and references for students, staff meetings, contact with, and receiving reports from, other relevant agencies, help with planning and organising the Open Day, planning use of tutor hours, interviewing applicants for part-time tutor position, checking unit standards and student evaluations, support, and supervise colleagues, fortnightly meetings with manager.

Descriptions and reflections on selected sessions

This section draws on the practice journals. It presents practitioners’ descriptions and reflections on one or two specific sessions that had taken place during the period. Participants were asked to select a couple of sessions on which to provide detailed and in-depth reflections.

What were the aims of sessions?

Many of the aims of the sessions were highly instrumental. They varied from the general to the highly specific. One practitioner wrote that the aim included “preparing students to gain various unit standards (mainly in maths but also in writing, e.g., sentence structure and spelling), helping students to complete CVs and letters of application for jobs, helping students to understand such things as pie charts, graphs, etc…”

Another practitioner identified the aims of four sessions, each with a different student, as follows:

The aims of [one] session were to introduce [the student] to the concept of paragraphing. I believe H is quite capable of reaching higher levels of competence than she has been led to believe in the past.

The aim of [a second] session [with a different student] was to assist the learner to become more focused and to complete something.

The aim of [a third] session [with two students] was to complete the assessment for US 8292— Use standard units of measurement. This is a very interactive and kinaesthetic assessment and I enjoy doing it. Although the assessments were carried out separately they were given on the same day and there were some interesting comparisons.

A third practitioner referred to two or three sessions, the aims of which were to review previous learning and to increase knowledge of the New Zealand health system and learn a number of relevant and useful words. In particular she wrote that:

My teaching was focused on the kind of words we would read on medicine labels (i.e., take, apply, dose). The aim is … to recognise (read) these words. Today was familiarisation with the words and what they mean. We also looked at words for medical treatments done in doctors’ surgeries and hospitals such as scan, blood pressure test, etc. They need to know these words and what they mean.

And a fourth practitioner identified the following highly specific cognitive aims for her learners for two sessions:

To recognise when to use an apostrophe to show ownership (singular and plural).

To learn a technique (practised by most of class at least once before) for deciding where to place the apostrophe.

To insert apostrophes for ownership into given sentences.

To write a paragraph for an essay, defining assertiveness.

Finally, one practitioner emphasised that the aims of all her sessions were framed in terms of the student’s primary aim which was “to be able to write concise, accurate and error free Incident Reports in the Day Book at her place of work”.

How were decisions made on content/curriculum?

All of the practitioners stressed the key role in decision making played by the learners. They were in general at pains to make the point that they did not attempt to impose their own ideas on the learners. Thus one practitioner wrote: “Our role as literacy tutors is to support individual and group learning for students and tutors alike.” And another wrote:

Decisions on what to do in each session are the choice of the student and always aimed at their primary goal. In the case of J this can include her own homework prose, reading aloud to improve pronunciation and expand vocabulary, spelling, dictionary use, work sheets, word games, etc.