He aha te mea nui?

He tangata, he tangata

What is the most important thing?

It is people, it is people

Introduction

This research project—a collaborative venture between two primary schools and Massey University—had its origins in the experience of the principal of one school She had developed and used integrated forms of curriculum delivery and associated pedagogies in other schools she had led. She believed that integrative curriculum designs positively influenced a number of key learning and teaching conditions, especially those connected with student engagement and community involvement, and that the use of integrative designs impacted positively on the achievement of students. James Beane (1997) describes the theory and practice of curriculum integration as “a curriculum design that is concerned with enhancing the possibilities for personal and social integration … [organising] curriculum around significant problems and issues, collaboratively identified by educators and young people, without regard for subject boundaries” (pp. x–xi).

In 2003, this principal worked with her staff to create and implement a vision of learning and teaching that was different from the ways in which the teachers had traditionally worked. She challenged them to examine what they did, how they did it, and why they did it that way. She also provided opportunities for them to reconstruct their thinking and practice, using the ideas around curriculum integration developed by Beane (1997). The principal of the other school (described in the findings as School One) worked with her as a professional learning partner. The two principals met regularly to share ideas and find solutions for issues that had importance for their schools and for themselves in their roles as school leaders. Their challenges and goals were very similar.

Both schools had a high proportion of Māori students (43.5 percent and 63 percent respectively). Student achievement data routinely gathered and analysed by the two schools during 2003 indicated that while some Māori students in both schools were achieving at expected levels, many were not. The engagement (or lack of engagement) in learning for some students was also of concern. Information collated by Group Special Education in 2003 suggested that students, whänau, and teachers had some negative views about the effects that behavioural issues were having on individual students and their engagement with learning. Parents’ perceptions about and expectations for their children’s learning reported to the schools by Group Special Education in 2003 also raised questions about each school’s partnerships with parents. Parental involvement in the schools was limited, being mainly attendance at parent interviews, or meetings to discuss the behaviour of their children. Anecdotal evidence suggested that parents and caregivers did not hold particularly high levels of expectation for the achievement of their children, and the students themselves did have high expectations of or belief in their own self-efficacy as learners. The principals were concerned that past attempts to change things had not resulted in improved outcomes for students, or more involvement by parents in the learning activities of their children. The overall aim of instituting change was therefore to:

- improve learning outcomes for all students, with a particular focus on the achievement of Māori students; and

- develop communities of practice within and between the two schools, to create a proactive and sustained focus on improving learning.

In 2003, both principals agreed that the changes to do with integrative curriculum design in the first school seemed to be having positive effects on teaching, learning, and community involvement. The principal implementing this change perceived a lessening of behavioural problems, increased engagement of students in the learning themes and topics studied, more whänau members turning out to school events, and changes in the ways teachers supported and worked with each other. As a result, the two principals, with the agreement of their respective staffs, decided to explore integrative curriculum designs and allied pedagogies in a collaborative, in-depth professional development initiative across the two schools during 2004. The expectation was that this professional development focus would provide ways of addressing concerns about student learning, increase the involvement of parents/whänau in their children’s learning, and also help develop professional learning communities within and between the two schools. The “lead” school aimed to further the changes it had already started, while working with and supporting the other school as it embarked on a change journey.

A detailed account of the actual professional development activities of the two schools is beyond the scope of this project, but a brief summary follows. The New Zealand Curriculum Framework (NZCF) (Ministry of Education, 1993) had prompted many teachers to take the view that pedagogical content knowledge is particular to each subject, and that student learning progresses through discrete levels of achievement. Their role as teachers was to provide sufficient coverage of each of the subjects as described in the NZCF and interpreted in the schools’ schemes of work. In both schools, therefore, most of the teaching done before the changes were implemented had used traditional approaches to curriculum design. Typically, 2–3-week units in timetabled subject blocks during the day, centred on achievement objectives from single subjects, used a transmission model of teaching (in which teaching is seen as information transmission—instruction—with teachers as subject experts and students as passive learners).

Teachers identified the application of knowledge to solve real-life issues and problems as a key reason for learning subject content. They also expressed beliefs about the need to develop in students the disposition to be life-long learners, able to engage, individually or with others, actively in learning to achieve their own goals. When they considered how these beliefs compared with what they actually did in terms of curriculum design, the teachers understood that transmission approaches in single-subject delivery modes did not necessarily support their students to develop these learning and thinking skills.

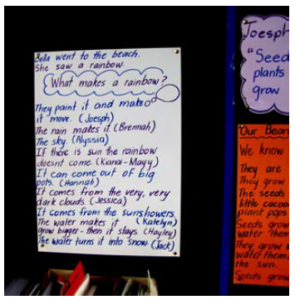

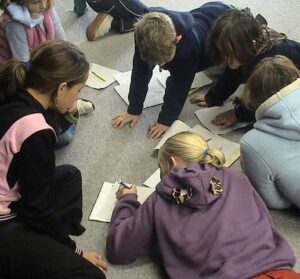

The two staffs then explored the theory and practice of curriculum integration as described by Beane (1997)—a view that begins from students’ viewpoint, questions, and concerns. Teachers in both schools tried different ways of gathering students’ questions—cross-age groups of students working together, and older students as focus groups—and then built learning themes and plans of work to investigate these questions or concerns. They planned collaboratively with each other (and sometimes with students), developing and using subject knowledge learning as required. Both schools tried different ways of involving parents and whänau more in their children’s learning. One school held school-wide open days at the end of each term to gather an audience for student work, when the students could explain their learning to those who attended. The other school tried similar activities to share student work, but generally on a class-by-class basis. Teachers also trialled pedagogical approaches that encouraged students to learn thinking skills (for example, undertaking investigations), skills of working with others (for example, co-operative skills, and working with whänau or cross-age-groupings), and techniques that encouraged them to take responsibility for their own learning (for example, goal setting).

By mid-2004, the principals and teachers wanted to find out more about the effects of the changes they were making. This research project, conceived as a partnership between the two schools and Massey University, sought to provide information for the two schools which would enable them to review their progress and plan ahead.

2. Aims and objectives of the research

The overall aim of the research project was to identify what shifts had occurred in the two schools after the period of curriculum and pedagogical innovation during 2004. The involvement of teachers in the research project provided a means of checking progress, as well as forums to identify problems and ways to solve them, all central activities of the implementation of change (Hopkins, Ainscow, & West, 1994). The project focused on learning about and describing:

- The extent and nature of any changes with respect to individual teacher practice, and the development of professional learning communities within and between the schools.

Recent research in New Zealand highlights the central importance of the influence of individual teachers working in their classrooms, as well as the degree to which they contribute to professional learning communities, as key factors in seeking to improve outcomes for students (Hattie, 2002; Timperley, 2004). The professional development during 2004 had aimed to support teachers in the two schools in reconstructing both their theories and practice in relation to curriculum design and their approaches to learning and teaching, in order to improve outcomes for students. It was important for the teachers to understand the extent and nature of the individual and collective changes they had made, as these shifts may have influenced other changes in both schools.

- The key factors influencing student engagement in learning.

Both schools described indicators of student engagement in terms of motivation to learn, social norms that supported learning, and feedback from students showing that they “liked” or “enjoyed” school and school activities. All three indicators are found among characteristics of quality teaching for diverse students identified in the literature (Alton-Lee, 2003). The teachers needed to understand further what factors influenced student engagement in learning, and to explore whether the changes they had made to teaching and learning had influenced student engagement in the two schools.

- The extent and nature of any changes in community involvement and participation in student learning.

Alton-Lee (2003, p. 38) reports research evidence that shows particularly strong and sustained gains in student achievement when schools and families develop partnerships to support students’ achievement at school. The schools wanted to identify what kinds of partnerships developed after the changes, and how these partnerships may have influenced student learning.

- The relationship, if any, between the changes made by teachers through the development and use of integrative curriculum design and alternative pedagogical approaches, and the learning outcomes for students

The purpose of the professional development was to change teacher practice, improve student engagement in learning, and increase parent/whänau participation in ways that were expected to improve outcomes for students. The teachers wanted to optimise academic, social, and personal outcomes for all students, particularly Māori students. The intention was not to focus on Māori students as “others”, but to work from the notion that all learners are different, and what works for disadvantaged or “at risk” students is also what works to improve the achievement of all students (Alton-Lee, 2003). The research project gave the two schools an opportunity to explore the possible linkages between the changes that had been made and student outcomes.

The relationship of the project to the strategic priorities of the TLRI

Strategic value

The key strategic themes of the TLRI are: reducing inequalities; addressing diversity; understanding the processes of teaching and learning; and exploring future possibilities. This project aligned closely with these themes. Each theme was important to both schools. They both had diverse student populations, with varying levels of student engagement in learning, and evidence of unequal outcomes for different groups of students. The teachers had engaged in professional development activities to develop their understandings about alternative curriculum designs and pedagogical practices. They wanted to explore, both individually and collectively, the nature and extent of the changes that had resulted, and what the possibilities for future action might be.

Research value

The project expected to contribute to research as it linked into the four key goals of the Curriculum Marautanga Project (Ministry of Education, 2004). The first goal of the Curriculum Marautanga Project is to clarify and refine curriculum outcomes. This study reports the attempts of two schools to design and refine the concept of integrated curriculum in action. The focus of the schools was on quality teaching, strengthening school ownership of curriculum, and strengthening partnerships with parents and communities—the remaining goals of the Curriculum/Marautanga Project.

A second contribution of the study was to assist teachers, students, and their parents to understand and clarify the connection between practice and research. Teachers and students can view research as something that is done to them, or written about them, by outsiders. Teachers may not always see new knowledge generated by research as relevant to their daily work, especially when reported findings are hard for them to access and use in their practice. The design of this project incorporated research with and on participants. Teachers and students analysed and summarised data, and provided their ideas about what that data meant. Whänau were also involved. Discussions at meetings allowed them to develop knowledge about the data and they too provided their views about what the data meant. The project provided opportunities to link the activities of practice and research.

Practice value

The research project was a partnership between the principals, participant teachers, students, and parents/whänau from two schools, and the researcher. The joint inquiry into shifts and changes provided learning for all participants, who because of the collaboration were able to gain understanding of what the other participants were saying, doing, or thinking. The joint inquiry also provided opportunities for a greater alignment of collective perspectives on learning and teaching goals, learning and teaching designs, and learning and teaching practices within and across the two schools—characteristics identified by Alton-Lee (2003) as important and necessary for improving student outcomes.

The project also provided opportunities to develop the capabilities of teachers as practitionerresearchers. Robinson (2003, cited in Cardno, 2003) contends that strengthening the research capabilities of practitioners is important, since using approaches based on research strengthens the connection between quality teaching and the level and quality of student achievement, as teachers inquire into and learn how to create the conditions that will produce improved results. The research activities of this project required teachers to articulate their beliefs and theories and examine them in practice. As these activities were situated within the context of the teachers’ actual work, analysing the resulting data provided them with opportunities to improve their teaching practice through evidence-based decisions.

The project also provided value in terms of opportunities for community members to contribute to the practice of teachers. Whänau were able to discuss what counted in terms of learning, and what worked or did not work for their children. By involving community members in the collection of data and in discussion forums to consider what the data meant, the project team was able to acknowledge the value of, and respond to, the perspectives and knowledge community members could contribute to decisions about improving learning opportunities for their children.

Research design and methodology

Planning

The project team developed a plan and timeline for the research activities in December 2004. As the project funding was for one year (2005), it was important to plan around fixed school events (for example, school camps and holidays) to ensure completion of the project. However, unforeseen events (for example, a delay with ethical approvals and the resignation of one principal during the year) affected the progress of the project. Regular meetings to reschedule activities minimised the impact of these events.

Ethical considerations

Any research conducted and directed by Massey University is subject to the protocols and requirements of the Massey University Human Ethics Committee. Gaining ethical approval proved difficult.

According to Cullen (2005), much educational research can be located on an outsider–insider continuum. This research involved an outside researcher investigating aspects of learning and teaching, and insiders—the teachers and students and their whänau—in participant roles in their particular settings. Research that combines outsider and insider activity raises complex issues in relation to the ethics of research.

Thorough and extensive ethical principles guide the practice of researchers from tertiary institutions. The principlist paradigm assumes a universality of central principles: namely, respect for persons, beneficence, and justice based on the individual rights of participants (Cullen, 2005). Educational research using qualitative methodologies may challenge the universality of these principles. Educational research, such as this project, is often collaborative and co-constructed with participants. It requires attending to the relationships of participants and is context-bound (Cullen, 2005). Principlist and relational paradigms informed the ethical considerations for the project.

The public announcement of funding for the project named the two participating schools. Thus it was not possible to protect the absolute anonymity of teachers and students. A key concern, therefore, was to preserve confidentiality as much as possible and ensure that participant teachers, students, and whänau remained unidentifiable in any summaries of data. In actuality, the researcher, teachers, and students quickly realised that this would be difficult. The location of the research was known, and therefore the identity of some participants could be worked out relatively easily. A rigorous process of consultation ensured individual consent for the use of specific data when confidentiality could not be guaranteed. One of the conditions for the funding of the project was that the research team submit milestone reports to the TLRI Advisory Board. The participating schools were consulted on the content of each report before it was released.

The Massey University Human Ethics Committee granted ethical approval on the basis of the process developed by the project team to ensure the educated consent of all participants—first the Boards of Trustees of the two schools, and then the participating teachers, students, and whänau.

We have highlighted these issues because we believe they require substantive and ongoing debate in the educational community.

Research participants

There were three groups of participants: teachers, students and their whänau, and the project reference group.

Teachers

All full-time teachers in the two schools were invited to take part in the project. One teacher, who was not fully involved in the implementation of curriculum integration, declined to participate, and one teacher withdrew after the initial interviews. Two teachers left their schools after the initial interviews, and one principal took up a new position at the beginning of the third term.

A total of 15 teachers took part in the initial interviews, and 15 took part in the autophotography and photo elicitation interviews (although two of these teachers joined the project midway though the year). Tables 1 and 2 summarise demographic information about participant teachers, collected at the beginning of the project.

| GENDER OF TEACHERS | |

|---|---|

| Male | 3 |

| Female | 12 |

| Total | 15 |

| ETHNICITY OF TEACHERS | |

| New Zealand European | 5 |

| European | 4 |

| New Zealanders | 3 |

| European/Päkehä | 1 |

| Päkehä | 2 |

| Total | 15 |

These non-standard descriptors use the terminology of the teachers themselves. All teachers identified themselves as non-Māori, using varying descriptors.

| YEARS IN TEACHING (number of teachers) |

TIME AT PROJECT SCHOOL (number of teachers) |

|

|---|---|---|

| 1–5 years | 4 | 7 |

| 6–10 years | 1 | 3 |

| 11–15 years | 2 | 4 |

| 16–20 years | 3 | 1 |

| 21–25 years | 2 | |

| 26–30 years | 1 | |

| 30+ years | 2 | |

| Total | 15 | 15 |

At the time of the initial interviews, five teachers had been at one school for less than 5 years. All the other teachers interviewed had been at that school for more than 11 years. At the other school, two teachers had been there for less than 5 years, three teachers for more than 6 years, one for more than 11 years, and one for more than 16 years.

Four of the seven teachers who had taught for less than 5 years in a project school had also taught for a total of less than 5 years. Of these four, two were in their first 2 years of teaching. The other three who were relatively new to either school had taught for more than 10 years.

The four teachers who reported teaching for 1–5 years and the two who had been teaching for more than 30 years were all from one school. At the other school, all seven teachers participating in the study had taught for more than 9 years.

Students and their whänau

Concerns about some students’ underachievement or lack of engagement in learning provided a rationale for the selection of student participants. Teachers from each school identified a potential group of students (mainly from Years 4, 6, and 8) whom they judged to be underachieving or at risk of underachieving (that is, capable of achieving higher results than their school assessments indicated). Teachers screened the potential student participants to make certain that they and their caregivers had received accurate information about academic achievement.

The selected year groups represented different stages within a full primary school. By Year 4, students have completed their junior primary education and have usually “mastered” basic reading and writing. At Year 6, some students enter the intermediate system. The students at both project schools usually remain for Years 7 and 8. Year 8 students are in their last year before entering the secondary system. The project team anticipated that the perceptions of these students and their families would provide data on expectations, levels of engagement, and types and extent of family involvement for students of various ages.

The teachers also identified a second group of 18 middle- to high-achieving students. These students took part in the autophotography activities to ensure that participating students were not easily labelled by their peers. The photographs of this second group, however, did not form part of the data set.

Parents and caregivers gave permission for their children to take part in the study. The students themselves then provided consent. The consent process reduced the potential group of 20 students to 18 (9 in each school). Two students from each school were absent during the initial group interviews and did not take any further part in the project, further reducing the total to 16. Table 3 gives demographic information about the participating students, collected at the beginning of the individual interviews.

| STUDENT DEMOGRAPHIC PROFILE | |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 9 |

| Female | 7 |

| Total | 16 |

| Ethnicity | |

| English | 1 |

| Päkehä | 2 |

| Mäori/ Päkehä | 5 |

| Mäori/New Zealander | 3 |

| Mäori | 5 |

| Total | 16 |

| Year levels of participating students | |

| Year 3 | 1 |

| Year 4 | 4 |

| Year 5 | 2 |

| Year 6 | 5 |

| Year 7 | 1 |

| Year 8 | 3 |

| Total | 16 |

| Number of years students spent at project school | |

| Less than 1 year | 1 |

| More than 1 year and less than 2 years | 1 |

| More than 2 years and less than 3 years | 1 |

| More than 3 years and less than 4 years | 3 |

| More than 4 years and less than 5 years | 4 |

| More than 5 years and less than 6 years | 2 |

| More than 6 years and less than 7 years | 2 |

| More than 7 years and less than 8 years | 2 |

| Total | 16 |

Thirteen of the 16 students identified as Māori or part Māori.

All except two students at each school had been there for their entire schooling.

The project team planned to meet at least twice with parent/whänau groups from each school, to explore their experiences and opinions of the changes teachers were making, and their view of and involvement in the learning of their children at school. The first meeting was used to explain the project and obtain consent from parents/whänau for the involvement of their children. A second meeting at one school, attended by two parents, provided little data for the project. The difficulties of aligning times for the researcher and parents, many of whom worked shift hours, prevented a second meeting at the other school. The final feedback meetings held at both schools in November drew mixed attendance. At one school, the representation of parents/whänau was strong; at the other, it was not. Section 4, findings, discusses whänau and community participation in more detail.

Project reference group

The project examined how changes to curriculum design and delivery influenced learning outcomes for students. As the study had the potential to include a considerable number of Māori students in proportion to the total student sample, the research team decided to involve a reference group. The reference group participants, identified by the principals and their Boards of Trustees, included key people from the Māori communities of the two schools and provided advice and guidance about protocols and ways of working with Māori students and their parents/whänau. Two meetings provided opportunities for consultation about the research methodologies, and feedback about the progress and findings of the research.

Methodology

A mixed-method, case-study approach was used. Case studies can answer the question: “What is going on?” (Bouma, 1996, p. 89), can “appreciate and understand an innovation from the inside”, and can “convey this understanding to others” (McKernan, 1996, pp. 80–81).

Case studies typically employ a range of data sources and incorporate both formal and informal instruments. Table 4 (adapted from the work of van den Akker, Kuiper, & Hameyer, 2003) shows teaching and learning as a progression of outcomes, from intended to implemented to attained. It also shows the different sources of data used in the project. Collating data from different sources and/or different participants made it possible to compile descriptions of a range of teaching and learning representations that were significant in terms of the research questions.

Document analysis

Documents from each school were analysed to clarify the stated intentions of each school. They included school communications with the community and Board of Trustees (newsletters and open days); school charters; curriculum planning documentation; and records of student achievement. They provided a record of the intended vision and intentions of each school with respect to learning and teaching, and the changes teachers had made or were intending to make. They also indicated the kinds of information presented by the school to parents/whänau, and the kinds of participation invited. Table 4 shows how teaching and learning representations were described, and what sources of data these descriptions were derived from.

| TEACHING AND LEARNING REPRESENTATIONS | DATA SOURCES | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Intended | Ideal | Vision (rationale or basic philosophy underlying a curriculum) | Document analysis

Semistructured interviews with teachers |

| Formal and/or written | Intentions as specified in curriculum documents or materials | Document analysis | |

| Implemented | Perceived | Interpretations of teaching and learning | Semistructured interviews with teachers and students

Autophotography and photo |

| Actual | Actual processes of teaching and learning

(also: curriculum in action) |

Classroom observations

Autophotography and photo |

|

| Attained | Experiential | Learning experiences as perceived by learners | Semistructured interviews with teachers and students

Autophotography and photo |

| Learned | Resultant learning outcomes of learners | Autophotography and photo elicitationStudent achievement data |

|

Semistructured interviews with teachers and students

The aims of the teacher and student interviews conducted towards the end of Term 1, 2005, were to:

- find out:

- how teachers interpreted the purposes, rationale, and key features of integrative approaches to curriculum design;

- what changes had been made at individual and whole-school levels;

- teachers’ views about the changes;

- the values and expectations they held about children, learning, teaching, and teachers’ roles; and

- determine students’ views about teachers, learning, and aspects of school life they liked or disliked.

The individual interviews allowed teachers to express their views in confidence. Students contributed to group interviews, because these were less threatening for them than meeting with an adult (Drever, 1995).

The interviews incorporated sets of closed and open questions that were linked to the research questions of the project. These questions included possible prompts (encouraging broadly focused responses) and probes (developing in-depth understanding of the broad responses). Prompts, probes, and follow-up questions explored and clarified the responses of teachers and students and helped to maintain a similar focus through all interviews. Teacher interviews recorded perceptions and opinions about the nature and importance of integrative designs, teaching pedagogies, and changes made individually and at whole-school levels. They also explored teachers’ relationships with students and their parents/whänau. Group interviews with students recorded views and opinions related to things teachers or other students were doing that either supported or hindered learning; changes students had noticed about how teachers were working; their relationships with teachers; how their parents/whänau were involved in school activities; and things they liked and disliked about school generally. The time taken to conduct each teacher or student group interview ranged from just under one hour to an hour and a half.

All interviews were audiotaped to allow focus on the responses of the interviewees and to maintain an interactive discourse during the interview. The tapes were then transcribed. Teachers verified, amended and approved transcripts before analysis. Students did not verify transcripts, because of the length of the material. To maintain confidentiality, teachers saw only their own transcripts. However, summaries of teacher responses informed the design of the classroom observation tool (see below). The principals from the participating schools had access to student transcripts to assist with the analysis of the data.

Analysis required the identification of themes and categories of response. The number of like responses under each category was recorded. Single or outlying responses were recorded separately, providing the opportunity to check the accuracy of self-reporting across all interviews. Thus the number of responses reported later in each category does not necessarily equate to the number of teachers or students interviewed.

Limitations

While interviews have potential to provide large amounts of data, interview data can be difficult to analyse. In the group interviews with students, some students tended to dominate the discussion. Other students contributed little and, when directly asked, tended to agree with other students. Taking time to get to know student participants before a group interview may mitigate the difficulties encountered with varying levels of participation. Full transcription, while time consuming and costly, allows interviewees the opportunity to check their responses, while researchers can read and re-read them in order to gain in-depth understanding of the responses.

Autophotography and photo elicitation

This research tool required teachers and students to create visual images to conceptualise fundamental beliefs and values about learning and teaching (Taylor, 2002). Participant teachers and students took photos and took part in follow-up interviews during the second term of the school year. Students and teachers took up to two photographs in response to each question, and wrote notes as they did so. The notes assisted teachers and students to recall their thinking during the follow-up interviews. Notes were written after the interviews to explain the interpretation of each photograph from the perspective of the participant.

This methodology, developed from work described by Taylor (2002), was intended to:

- identify the real interests, concerns, and issues students had about their involvement in learning; and

- stimulate teachers to reflect on and further develop their conceptions of themselves as teachers, and their understanding of how students learn and might best be taught.

Reviewing and discussing an article by Taylor (2002) at a meeting of teachers from both schools gave the teachers an opportunity to shape and develop protocols and guidelines for taking part in autophotography and photo elicitation interviews. The follow-up interviews explored the beliefs and values underpinning the decisions made, and permitted “others to view the world from the view of the observed persons” (Ziller, 1999 in Taylor, 2002, p. 125). Teachers shaped four questions, with some adaptations for students, to guide their thinking and decisions about the images they created.

| Teacher autophotography and photo elicitation: interview questions | |

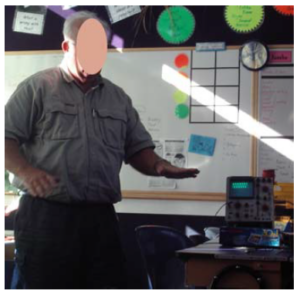

| • | When I think of what I do as a teacher to meet the diverse learning needs of my students what visual images come to mind? |

| • | When I think of student engagement, what visual images come to mind? |

| • | When I think about the community participation, what visual images come to mind? |

| • | When I think of about enablers for learners in this school, what visual images come to mind? |

| • | When I think of about barriers to learning in this school, what visual images come to mind? |

| Student autophotography and photo elicitation: interview questions | |

| • | When I think of what my teachers do to help me learn, what visual images come to mind? |

| • | When I think of what helps me to be really interested in learning, what visual images come to mind? |

| • | When I think about how my family joins in with school things, what visual images come to mind? |

| • | When I think about what I like about my school, what visual images come to mind? |

| • | When I think about what I don’t like about my school, what visual images come to mind? |

Teachers analysed the teacher and student responses from their own school by viewing all of the responses and categorising them under emerging themes. Teachers wrote summaries of the data, identifying trends, patterns, key similarities or differences for each question, and how the responses linked with the goals of their school. The teachers from each school also recorded recommendations for future action.

Students analysed their narratives in school groups, using a slightly different framework. They identified common messages and discussed the feedback they would like to provide to the teachers in their school, using three descriptors:

- things teachers should keep doing;

- things teachers should do less of; and

- things teachers should do more of.

Both teachers and students engaged fully with the autophotography and photo elicitation approach. In all cases, participants were able to fully explain the thinking that had prompted their choice of image. Students, in particular, revealed their thinking about their experience of school, teachers, and learning far more deeply than in the group interviews.

Teachers and students played an active role, both by taking the photographs and through their discussion during the interviews. Having the opportunity to describe their pictures, rather than leaving them for the researcher to interpret, was important. This observation is consistent with other research findings in connection with this research tool:

Research subjects are not treated (or refuse to act) merely as containers of information that is extracted by the research investigator and then analysed and assembled elsewhere. Rather, the introduction of photographs to interviews and conversations sets off a kind of agency, causing people to think of things they had forgotten or to see things they had always known in a new way … (Banks, 2001, reported in Taylor, 2005, p. 129)

Teacher and student analysis of the photographs and interview narratives enabled school groupings to understand the culture of their particular schools. Teachers, in particular, were pleased to find that their thinking was similar to that of others in their setting, or surprised that their views differed. The summaries provided information for forward planning for both schools. The process acknowledged the importance of students’ “voice”, and teachers undertook to include the student feedback in their planning.

Limitations

The use of autophotography and photo elicitation has limitations. Not knowing how to use a digital camera created initial barriers for some teachers. Many of the photographs carried sensitive messages or identified individuals in the schools. For these reasons, the research data did not include some photographs and interview responses. Some participants had difficulty in representing some topics visually, or found that making visual images limited their thinking. Some teachers and students discussed reasons for this, others simply declined to respond to some questions. Some teachers and older students created metaphoric images rather than “true” images, as this enabled them to portray complex thinking. Younger students found this kind of abstract thinking difficult.

Classroom observations

The aims of the classroom observations were to:

- develop teachers as researchers by observing each other’s classroom practice, using a collaboratively designed data collection tool;

- see the actual implementation of curriculum integration by focusing on the processes of teaching and learning; and

- explore the match between the intended (espoused) and implemented (actual) curriculum.

Teachers planned the format and procedure of these observations during the school holidays before the beginning of Term 3. They developed indicators of integrative practice using collated responses from the individual interviews. A guiding question was: “If this is what you say about …, then what could someone expect to see happening in classrooms?”

The observations recorded the activity of the teacher (for example, whole-class, group, or individual teaching) and three focus students (for example, engaged or not engaged) ten times at specified time intervals. The work of Te Kotahitanga (Bishop, Berryman, Tiakiwai, & Richardson, 2003) informed the design of the recording template. The teachers also designed a separate “environment check sheet” to provide opportunities for noting elements and artefacts not actually used during the observation. These items included drafts of work in progress, displays of theme-based work, visibly recorded learning intentions, inquiry planning, graphic organisers for higher order thinking, displays of children’s questions, and variable working spaces.

Each teacher paired with a teacher from the other school, setting times for observation and feedback to each other. The observed teacher was responsible for sending records of the observation notes and follow-up discussions to the researcher.

The implementation of classroom observations proved difficult after the principal of one school resigned to take a promotion. Although the principals and teachers were closely involved in the design of the recording formats and processes, tensions emerged after the first cross-school observations—an “uncomfortable” situation developed between the observer and the teacher observed. One school was experiencing instability of student behaviour at a time of change, and trust between the two schools was not at a high enough level to sustain the observation process. The principals agreed to continue with in-school rather than cross-school observations.

Limitations

The process required teachers to record key points from the discussions after the observations and to send these, with the observation sheets, to the researcher. The agreed protocols required the removal of any identifiers (for example, names, class levels, or school details). There was no way of knowing who completed the observations and who did not. Twelve sets of classroom observation notes were received out of a possible 15. None of the observation records were complete. The teachers and observers had not indicated the context of the lesson, they recorded only some of key elements of teacher/student activity during the observation, and/or did not include notes detailing the follow-up discussions. For these reasons, information gathered during classroom observations was not used in this report.

Teachers discussed ways of overcoming the difficulties associated with classroom observations. They reported that the method of data entry was complicated and they needed more practice observing and recording. They felt that their schools were too busy with other initiatives during a shorter-than-usual school term to do justice to the process. Despite these problems, teachers from both schools commented that they gained valuable knowledge about their practice from the discussions with the observer. The discussions judged most beneficial were those that immediately followed the observations. One school intends to use a modified form of classroom observations as a regular part of its appraisal system in 2006.

Student achievement data

In the absence of assessment tools directly related to the changes made to curriculum design and delivery, the project team decided to use the Supplementary Test of Achievement in Reading (STAR) as an indicator of raised student achievement, as literacy is a tool for thinking and learning across the curriculum.

Both schools administered the STAR in February and again in December, as part of their routine school-wide assessment programmes, and collated the results for the participating students. The use of the STAR provided an opportunity to use normative data to identify any shifts in the achievement of students and to compare these with national expectations.

Limitations

The STAR provided information about one aspect only of close reading. The quality of specific instruction in reading was more likely than other more implicit forms of literacy learning to influence changes in achievement.

The project team was not able to broaden the collection of student achievement data beyond the simple indicator provided by this one standardised achievement test. One school was developing an alternative assessment system, using portfolios of student work to track learning outcomes related to the changes they were trying to implement. The other school had not started to align its assessment systems with the implemented changes in learning and teaching. Both schools identified the development of assessment systems and processes in their action plans for 2006 and beyond.

4. Findings

The aim of the research project was to identify the shifts that occurred after a period of curriculum and pedagogical innovation during 2004 in two schools. The findings, structured by using the research questions, provide a picture of what was going on in each school.

School One

This section reports findings from document analysis and interviews, autophotography, and photo elicitation from eight teachers and eight students from one school in relation to each research question.[1]

1. What was the extent and nature of any changes with respect to individual teacher practice and the practice of professional learning communities within and between the schools?

Teacher responses

The core teaching belief espoused by the school in its charter (2004–2006) documentation identified “earning power” as a key outcome for students. Learning power included the foundation skills of literacy and numeracy and the skills and attitudes to become lifelong learners. The charter described a focus on the “best of traditional and innovative approaches to learning”. The excerpt from the charter reproduced below lists the ways in which teachers were expected to achieve the desired outcomes for students.

All staff will base their teaching on:

- The belief that all students can learn;

- The need to instil in students the need to think of the rights of others and develop a sense of self responsibility;

- The desire to help all students develop a positive self-image and identity;

- Ensuring that all students need to be competent in acquiring basic skills as well as learning ‘how to learn’;

- The traditional values of applying effort and perseverance; and

- Encouraging students to take a growing responsibility for their own quality learning.

Action goals identified as key mechanisms for achieving the vision included: establishing curriculum integration; reviewing curriculum delivery and implementation statements; encouraging staff and pupils to be reflective practitioners; and encouraging staff to refine and improve practice through professional development. Further, the charter identified the Board of Trustees, teachers, parents, caregivers, and students as having collective responsibility for achieving the vision.

The charter indicated a central intention to develop and refine the implementation of curriculum integration and alternative pedagogical approaches (for example, thinking skills). Responsibility for outcomes lay with the wider community of the school, and espoused beliefs focused on a wide interpretation of what constituted valued learning outcomes, including (but not limited to) academic outcomes.

During 2004 all teachers in the school engaged in professional development for implementing integrative curriculum designs and different pedagogical approaches, in line with the intended actions expressed in the charter documentation. They continued with this work during 2005. All teaching staff engaged in professional development that focused on action learning.

Responses from individual interviews with teachers provided information about what they conceived integrative curriculum designs to be. Their responses (n = 8) reported that curriculum integration meant deciding on a focus and linking all curriculum areas. Three responses further indicated that this should include all curriculum areas to a greater or lesser extent. Three responses focused on working from the needs or interests of students in authentic contexts, three responses identified pedagogies, one teacher talked about the need for community involvement in learning, and two teachers also mentioned teachers working together.

The implementation of integrative curriculum designs, as described by Beane (1997), required teachers to change their professional practice, both individually and collectively. When asked to describe the changes they had made, teachers reported change in a number of areas, and sometimes added evaluative comments about the nature of those changes.

Seven reported the introduction of school-wide changes to planning and reporting. Five explained that student interest now formed the basis for planning, but that teachers continued to decide on and plan the actual units of work:

Children are more involved in making choices about learning.

One teacher commented that they now made “taking action”—meaning that students used their new knowledge and skills to find solutions for identified problems or concerns—an integral part of the unit. While developing a whole-school approach to unit planning, teachers also reported that they focused more on the individual needs and interests of students (n = 5). Within the general unit frameworks, teachers allowed students to engage in learning activities in different ways and to “express their thinking in different ways”.

Teachers discussed a number of ideas that indicated shifts in their actual teaching practice. They also reported an increase in the direct teaching of learning skills and strategies. Comments included:

Teaching about learning and thinking is more important than information about things. (n = 2)

We are using more co-operative activities. (n = 3)

Teachers teach children to plan their own work at their own pace. (n = 2)

| Teacher response | |

|

Co-operative learning actively supports the diverse learning needs of children. Children are grouped according to the nature of the task and the level of support that individuals require. Co-operative grouping enables children to participate in ways that all can achieve the goals of the task. By working together, they can share ideas and expertise and teach other. |

Four responses noted that changes which included a more direct focus on direct skill teaching required “very structured teaching”. Teachers recognised the need for explicit teaching for students to be able to learn about and practise the skills during learning activities.

All participating teachers (n = 8) reported that how they worked together as a staff had changed as they implemented integrative curriculum designs. They reported more joint planning and constructive talk about teaching (n = 4), and providing feedback to each other about their teaching (n = 3). Teachers reported that working together provided opportunities for personal and professional support, focused on improving learning for their students.

| Teacher response | |

|

Teachers are the most important enablers of learning. They guide, support, praise encourage and provide feedback to challenge children as far as they can go. The teachers are committed to supporting each other and the children. They strive to keep professionally informed because they are passionate about improving learning for kids. |

| Teacher response | |

|

Celebrations are in balance at our school. Teachers push themselves but not too far or too fast. Collegial support at both personal and professional levels is strong. |

Five responses also indicated concerns about the increased amount of collaborative work. One teacher of this group did not support the increase in joint planning: “I can’t do what I want to do”. Another thought that joint planning of units was not very successful: “Our units seem to go belly-up half way through”. Another teacher commented that it was “a challenge to get enough opportunities for in-depth learning” included in the unit planning.

Involvement in whole-school professional development initiatives also increased the joint work resulting from planning term-long, whole-school units. All of the participant teachers undertook professional development related to action learning during 2005. Participation in shared and “much more focused” professional development provided opportunities for teachers, both individually and collectively, to inquire into their practice and to share their strengths. One teacher remarked, “Combining ideas and getting different perspectives has been awesome”. Another noted that involvement in professional development caused individual teachers to focus on their own practice as a way of improving outcomes for students.

| Teacher response | |

|

Professional development improves my knowledge of pedagogy to meet diverse needs. I actively seek knowledge, to increase my understanding and then seek to apply the ideas in a practical way. I have moved from trying to shift children to shifting myself. I ask questions of my practice- “What do I need to do?” How can I change what I am doing to help children learn?” What other approaches can I use?” |

The changes reported by teachers went beyond the organisation, management and content of learning and teaching in the school. As teachers developed ways to teach thinking and learning skills explicitly within their units of work, three teachers reported shifts in their beliefs about what students could do and achieve:

Teachers believe that students can do more now.

Teachers are allowing students to be more creative.

Our expectations are probably too high now—we expect students to be able to do things without teaching them like research skills.

Another teacher said that expectations “probably haven’t changed”.

To some degree teachers supported changes they had made as a school to curriculum design and teaching focuses; five reported that everyone was committed to the vision of the school, with one teacher commenting, “We are all at different stages but all facing the same way”.

Five teachers said that change would continue only if there were not too many changes in staff. Teachers also identified a second difficulty in relation to the changes they were implementing: documentation required by the school, described as “paper work”, had not yet developed in line with the practices teachers used. Five teachers noted that assessment, in particular, required further work. While teachers reported a shift in their assessment practices to focus more on the assessment of learning skills and strategies, school documentation continued to concentrate on recording the progress of student learning in terms of the achievement levels described in individual curriculum statements.

| Teacher response | |

|

The paper work gets in the way. Some of what we do hasn’t kept up with the changes we have made to our curriculum delivery. This is being addressed but some of the traditional things (i.e. the checklists) don’t match with our new approaches such as formative approaches to assessment. |

Student responses

Student responses in the group interviews indicated that they had not noticed a great deal of change in what teachers were doing. One group of students identified changes to timetabling in classroom programmes. Other group responses discussed new buildings and that things at school were “OK”.

2. What key factors influenced student engagement in learning?

Teachers’ responses

Teachers wanted to know whether the changes made in curriculum design and teaching methods had improved the engagement of students in learning.

Teachers believed that integrative curriculum designs had potential to influence student engagement in learning positively. Beane (1997) describes curriculum as integrative when the approaches used seek to organise learning around personal and social issues, problems, and concerns identified in or developed from the lives of learners in the world in which they live. Teachers reported that they planned units based on students’ interests, issues, or concerns (n = 4), involved students in planning for learning (n = 1), and ensured that learning was relevant to their lives (n = 1). Two teachers commented that, while they wanted to work in these ways, they were “not quite at that stage yet”. Teachers wanted students to learn in an environment that created links between school and the other aspects of their lives.

| Teacher response | |

|

Integrated curriculum is based on teachers’ knowledge of their children’s interests. Working as a team on activities builds an environment of interest, focus, captivation and perseverance. Ownership and choice are key components but it’s hard to incorporate this into the class learning programme. |

Teachers identified what they thought they had achieved. They reported an emphasis on building supportive classroom environments (n = 7), building peer support through co-operative learning (n = 4), and increasing student ownership of learning by creating clear learning outcomes with students (n = 3).

| Teacher response | |

|

Cooperative learning engages those children who don’t normally get involved. It’s fun. Children are focused, they know what the learning outcomes should be, they plan to achieve these while learning and supporting each other. Children are more likely to be on task longer, more likely to problem solve, more likely to be creative as they listen, share and work in groups or pairs. |

However, when asked to evaluate the effectiveness of links made with the cultural contexts of student lives, teachers reported mixed views and mixed understandings. Three responses reported that the content of units made such links. The following comment exemplifies this view:

They are doing recreation, I’ve got lots of Māori students in my class, we are going to be looking at Kapa haka …

Two teachers assumed that students would recognise inherent cultural links in unit work without needing them to be made explicit:

… looked at the cultural perspective—cultural identify—who am I? I tried bringing in New Zealand history but that didn’t work—I thought that’s what they need …s o that was learning for me …

I thought they’d make the connection, but they didn’t.

Other teachers (n = 3) thought that creating links with the cultural contexts of the students was important, but were unsure how to proceed. They commented that parents/whänau needed to be involved more, without saying how this might be achieved:

It would have been nice to have some of the other families in. (

Not a lot of iwi support for the school.

Six teachers talked about changes they had noticed with student engagement in learning. Three responses noted positive changes in relation to motivation—“Children are excited about learning”— and the social norms prevalent in the school:

Seniors work well with junior children.

Children are learning more from each other like ways of presenting information.

Three teacher responses noted ongoing behavioural challenges that influenced student engagement in learning:

| Student response | |

|

I like doing art work. You can take it home and show your parents. (year 4)I like art work. Art is easier although what our teachers expect is higher now. (year 6)I like doing art a lot. It’s fun. When I was little I wanted to be an artist. I’m good at art -it’s easy. (year 6)I like drawing. It gets me thinking about stuff and it’s easier to draw what we know. It gives your brain a rest. (year 8) |

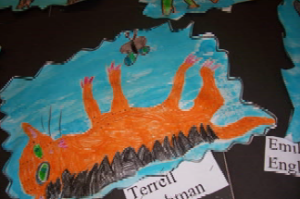

During group interviews students discussed things they liked or disliked during “topic time”, the time allocated in classroom programmes for integrative units of work. Students could name the topics completed and identified some they enjoyed (for example, the themes about “Friends” and “My place”—mentioned in relation to the amount of art completed).

Students also reported that they liked “thinking”, “trying to achieve their goals”, “teachers letting us do our own thing”, “ working more in groups”, and “working more with younger children and being role models”. These ideas were reflected by teachers when they described what they thought they had achieved in terms of improving student engagement in learning.

Students did not focus on the same aspects when they participated in autophotography and photo elicitation interviews. Here, when students were asked to think about what they liked or disliked about school, their responses focused on friends, doing physical education, and receiving awards.

| Student response | |

|

I like working on the computer. It does not take as long, it’s not so much hassle and you can do things more easily. (year 4)

We enjoy using the computer-it’s faster and it’s fun. You can change words, look things up and play games. (year 6) |

| Student response | |

|

I like the playground. My group plays here and we don’t get bored.(year 6) I like playing on the playground. It’s fun to jump all over the place. I usually play there with my friends. Friends are important. They are cool and funny. (year 8) |

All three groups of students in their interview responses identified the behaviour of other students as getting in the way of doing well at school.

3. What was the extent and nature of community involvement and participation in student learning?

The school wanted to identify the extent and nature of the involvement and participation of parents/whänau, because research has shown that strong and sustained gains in student achievement are possible when schools and families develop learning partnerships to support students’ achievement at school (Alton-Lee, 2003). Teachers anticipated that the development of integrative approaches would provide a vehicle for strengthening existing participation, because they organised more opportunities for parents/whänau involvement as part of their unit planning. An example was “Pure Day”—the name given to a day organised as part of a unit when community members and parents contributed their knowledge and expertise to support students to try a range of leisure and sporting activities.

Teachers’ responses

Teachers identified the kinds of involvement parents were having in the school. Five responses identified the three dominant forms of involvement: parenting (helping families establish home environments to support children as students); communicating (designing effective forms of schoolto-home and home-to-school communications about school programmes); and volunteering (recruiting and organising parent help and support) (Alton-Lee, 2003).

There’s a lot more in-your-face focus with the newsletters.

Teachers were aware of the need to involve parents/whänau more closely in the learning of their children. They saw the “open door” policy of the school (n = 5) and planned sporting events (n = 1) as possible ways to encourage parents to come into the school:

[Parents] will meet us out on the touch field and they will play a game with us. From there you have kind of got them …

| Teacher response | |

|

Parental involvement and participation with their children enhances community participation in learning activities at school. Sport provides a known territory for parents unlike the unknown territory of teacher talk. Childrens’eyes light up when parents unexpectantlyturn up. Participation in other ways then builds-one parent is now coaching the school’s sevens team. Relationship building is the key. Parents need to feel appreciated. |

Another teacher indicated the need for students to be part of this process. This teacher and the students in the teacher’s class invited parents/whänau to view and discuss their children’s work at the conclusion of a unit about whakapapa/family histories. The teacher and principal both commented that parents came along whom they had never seen before. The teacher discussed the potential quality learning experiences at school could have:

It needs kids to be really excited about sharing. You have to get the kids saying ‘Mum, Dad, you have to come’.

While the school attempted to increase parent/whänau participation in the learning of students at school, this had not yet happened to any great degree. Two teachers identified that parents/whänau probably did not know what was going on at school, and commented: “We just assume the kids go home and tell them, but maybe they don’t”.

Teachers also identified a number of factors beyond the school’s control as reasons why they had not been more successful at involving parents/whänau in the learning of their children at school. These views closely aligned with barriers to learning identified in seven out of the 15 teacher autophotography and photo elicitation responses. Teachers perceived that it was primarily family factors, not school factors, that prevented the greater involvement of parents/whänau and improvement in learning for students. The teacher autophotography and photo elicitation response below provides an example of this kind of response, along with an explanation of what the school was trying to do to address these issues.

| Teacher response | |

|

Sleepy tired and hungry children are not able to connect with learning. We have two breaks at school to encourage healthy eating. The teachers sit with the children for 10 minutes to ensure that the children eat their food. This results in better playground behaviour too. |

Student Responses

Students mentioned a different form of parent/whänau involvement from the three identified by the teachers. One student group response reported that parents helped with homework. The autophotography and photo elicitation responses echoed this, as three student responses identified homework as a key conduit between home and school.

They also identified different reasons for their parents/whänau not being involved with school. Their interview responses indicated that work commitments prevented parents/whänau from coming to school for planned events, or becoming involved in school activities.

| Student response | |

|

My family helps me with my homework, especially spelling. (year 4)

My family helps me if I have trouble with homework. Dad likes helping me- it helps him learn too. (year 8) Mum and Dad always help me with my homework, even when I don’t ask. They try to help me read properly and do more of it. Sometimes they read to me and I read to them when they ask. They are quite interested because they want to help me learn. (year 8). |

3. What relationship, if any, was there between the changes made by teachers with the development and use of integrative designs and alternative pedagogical approaches, and learning outcomes for students?

The aims of the professional development undertaken in 2004 were to change teacher practice, improve student engagement in learning, and increase parent/whänau participation in ways that would improve outcomes for students. The research project was intended to enable the school to explore the possible linkages between the changes and student outcomes.

Teachers’ responses

At the beginning of the project, the majority of teachers (n = 6) believed that positive learning outcomes were possible through their efforts to develop integrative curriculum designs, combined with the use of different pedagogical approaches. Three responses in the initial interviews qualified this view, and indicated indecision, or the possibility of variable outcomes:

Some kids possibly, if they come from a home and everything is being done for them, they may not want to take that step and become self-motivated learners.

I think there are occasions where basic skills, basic things they are going to need really do need to be taught and if you can do that through integration, thank goodness. If you can’t, you need to follow other structures.

There is room for traditional approaches … I think there has to be a balance.

Teachers (n = 7) perceived that the changes they had made to their learning and teaching (for example, units based on the interests of students, and explicit teaching of learning skills and strategies) positively influenced the learning behaviours of students. They described a range of indicators to support their views:

More precise talk about learning.

[I’m not sure] whether they have a deep understanding—at least the fact they are verbalising, we can start to build their understanding.

Learning to be more independent/take more responsibility. (n = 3)

Becoming more active learners.

More interested in the others in the class.

More risk taking.

Awareness of co-operation.

Two teachers reported improved behaviour a result of the school’s focus on behaviour management.

Teachers’ perceptions (n = 7) about the benefits of the implemented changes for students were at best guarded, with two teachers reporting that the changes were not positive for all children, and one was not willing to judge:

Not positive for all children. (n = 2)

Positive, but attributes of children affect outcomes. (n = 2)

Positive, but not consolidated outside of school gates. (n = 2)

CI shows potential to engage children but still a lot of work to go. (n = 2)

Don’t know about impacts.

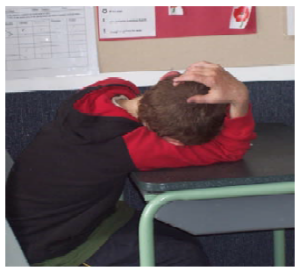

Autophotography and photo elicitation responses revealed what teachers perceived as barriers to improving learning outcomes for students. Of the 15 follow-up interviews, six responses focused on children’s disengaged attitudes, or their lack of ability to form productive working relationships.

| Teacher response | |

|

Disengaged attitudes and withdrawal from social situations interrupt learning. Some children find it hard. Teachers need to spend more time to engage these children. |

The student posed for this photo.

| Teacher response | |

|

Relationship skills or the lack of them can be barriers for some children. Angry children sometimes do not have the skills to get over issues, so cooperative learning skills are a teaching focus. |

Student responses

The students’ view of what teachers were doing to help them learn demonstrated a beginning ability to “talk about learning”. Three responses in the photos and follow-up interviews identified the support teachers provided. These are shown below.

| Student response | |

|

Teachers tell you what to do and give clear instructions-that makes learning easy. She does not growl-only if it is really noisy. (year 4)

My teacher explains things well and helps me to work it out. Sometimes she lets me work with others-they help me a lot too. (year 6) Teachers help us to do the work. They talk to us. Sometimes when I don’t know what to do, she helps me by helping me to work it out. (year 6) |

While students generally identified positive things, one child remarked:

Teachers encourage us, but they don’t really believe you can do things.

Data from STAR assessment

Teachers recorded results from the Supplementary Test of Achievement in Reading (STAR), administered as part of the school’s regular assessment programme for the participating students. The STAR results in Table 5 show variable shifts in stanine scores over the year, and in one case a regression.

| RAW SCORE | STANINE SCORE | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Students (n = 8) | February | December | February | December |

| Year 4 | 10 | 19 | 2 | 3 |

| Year 4 | 15 | 21 | 3 | 3 |

| Year 4 | 16 | 25 | 3 | 4 |

| Year 6 | 25 | 32 | 3 | 4 |

| Year 6 | 22 | 29 | 3 | 3 |

| Year 6 | 26 | 38 | 3 | 5 |

| Year 8 | 36 | 57 | 3 | 5 |

| Year 8 | 25 | 28 | 2 | 1 |

Of the eight students, one scored well below average, three scored below average, and four were within average scores for their age (although two of these are at the lower end of the range). A judgement of significant improvement occurs only when there is a gain of two or more stanines. Two students made gains of two stanines, three made gains of one stanine, two students maintained their stanine level, and one student went back a stanine.

As previously discussed, these results provide information about only some aspects of reading. The teachers acknowledged the inadequacy of using STAR test results as an achievement measure, because it did not provide evidence of the broad range of learning outcomes they were seeking to achieve. The school identified the need to review and refine its assessment systems and processes to be able to track student achievement in areas related to social and personal development and academic learning in integrative contexts.

Summary

The aim of the research project was to learn about and describe changes after a period of curriculum innovation in 2004 with respect to the practice of individual teachers, the development of professional learning communities, student engagement in learning, community involvement and participation in children’s learning, and learning outcomes for students. Involvement in the research project gave teachers a means of checking progress, and also provided forums to identify problems and find ways to solve them—all central activities of the implementation of change (Hopkins et al., 1994).

The qualitative evidence suggests strong connections between the formal intentions of the school to implement integrative designs and alternative pedagogies, and the espoused views of the teachers. Clear links were evident between the charter documents, the philosophical beliefs held by teachers, and the changes the teachers were trying to implement.

However, the evidence also suggests that the initial changes the school had made to teaching and learning programmes were largely organisational and managerial. Teachers planned longer units and themes as a team, and in doing so developed further their culture of collegial work. Teachers explored a range of pedagogical approaches (including explicit goal setting, co-operative learning, and explicit teaching of research skills using an action learning framework) and developed some confidence in using them. Early indications of enhanced student learning (for example, improved general behaviour, greater engagement of students, glimpses of abilities not previously noticed) rewarded teachers’ efforts, and to some extent mitigated the negative feeling about inappropriate “paper systems” in the school. Teachers increased their sense of agency in relation to outcomes for students. Perceived barriers were increasingly seen as problems to address, rather than reasons for taking only limited action.

No links were evident between the school’s expressions of collective responsibility for learning, as expressed in the charter, and the practice of teachers. Teachers had not yet identified how to connect strongly with the cultural backgrounds of their students. Students viewed cultural connection as occurring in activities outside classroom programmes. Some teachers also believed that their ability to influence outcomes for students was limited because of familial or societal factors beyond their control. There was a sense that whänau did not want to be participants in their children’s learning. The analysis of interview and photo interview responses about barriers to learning and whänau participation proved uncomfortable for teachers when they confronted the data, and this activity highlighted the need for them to talk openly about such issues. To their credit, the teachers did just that, without any outside prompting.

Teachers’ recommendations

The teachers developed their own set of recommendations as outcomes of the research activities. These are listed below. The school intends to incorporate these recommendations in their planning for 2006.

- Develop ways of planning more with students, to include their interests and concerns. Planning in this way has potential to increase student ownership and engagement with learning.

- Engage in professional learning that directly improves practice by focusing on making changes in relation to student learning needs, rather than just implementing new activities.

- Develop a stronger culture of “no excuses”. Hold high expectations and then work to achieve them with students.

- Continue to scaffold student learning by providing explicit teaching and learning of new skills and processes, and giving students feedback on these.

Students identified clear instructions and clear learning goals as important. Teachers acknowledged that, while students were not yet able to articulate clearly factors that helped them to learn, their ability to identify learning activities they liked improved during the year (for example, co-operative groupings).

- Continue to build the focus on the total wellbeing of students by promoting healthy lifestyles and teaching social skills.

- Plan opportunities with whänau to move from partnerships based almost exclusively on parenting, communicating, and volunteering to learning, decision making, and collaborating (Epstein, 2001, in Alton-Lee, 2003).

Teachers acknowledged that they needed to be more proactive in ensuring that parents/whänau were able to participate. Suggestions included varying the time of invitations to school, to enable working parents to attend.

- Review and develop assessment systems and processes to enable teachers, students, and whänau to identify and celebrate progress across a range of desired outcomes (academic, social, and personal).

- Move collegial working relationships to more collaborative, reflective practice grounded in evidence-based decision making.

Teachers acknowledged that the research activities had provided information they had not previously considered.

Students’ recommendations

Teachers also took on board the feedback from students. Students’ recommendations included:

- More explicit teaching of learning strategies.

Students identified some aspects that supported their learning (for example, clear instructions) and they wanted teachers to do more to support these aspects.

- The importance of continuing with homework, to provide opportunities for parents to be involved with their learning.

The teachers discussed this at length and agreed to continue with homework, while also seeking to shift the dominant perception of students that their parents were too busy to support learning in other ways and at other times.

- More use of ICT, art, and out-of-class experiences.

The students identified these areas as things they liked about school, as they were “fun”. Teachers agreed to incorporate these elements more in learning experiences as ways for students to develop and explain their thinking.

School Two

This section reports findings from document analysis and interviews, autophotography, and photo elicitation from seven teachers and eight students from the second project school in relation to each research question.