Dedication

This report is dedicated to the memory of Fred Kana, our dear friend and colleague. Moe mai rā, e hoa.

1. Contexts for the research

Whakawhanaungatanga, Tiriti-based partnership, and narrative methodologies

This project has extended upon knowledges gained from a previous Teaching and Learning Research Initiative (TLRI) research project, Whakawhanaungatanga—Partnerships in Bicultural Development in Early Childhood Care and Education (the Whakawhanaungatanga project) (Ritchie & Rau, 2006), which focused on identifying strategies used by early childhood educators, professional development providers, teacher educators, and an iwi education initiative. This kaupapa is consistent with the bicultural mandate contained within key regulatory and curriculum statements. These include the Ministry of Education’s Desirable Objectives and Practices (DOPs) (Ministry of Education, 1996a) requirement 10c, whereby management and educators are required to implement policies, objectives, and practices that “reflect the unique place of Māori as tangata whenua and the principle of partnership inherent in Te Tiriti o Waitangi”, and the national early childhood curriculum, Te Whāriki (Ministry of Education, 1996b), which states that “In early childhood settings, all children should be given the opportunity to develop knowledge and an understanding of the cultural heritages of both partners to Te Tiriti o Waitangi” (p. 9). Te Whāriki has been acknowledged as progressive in its sociocultural orientation (Nuttall, 2002, 2003) which emphasises the valuing of diverse identities (Grieshaber, Cannella, & Leavitt, 2001) and acknowledges a kaupapa based in the partnership that is signified in Te Tiriti o Waitangi (Ka’ai, Moorfield, Reilly, & Mosley, 2004).

Recent research has identified three general characteristics of effective partnerships in education settings:

- acknowledging the mana or expertise of each partner in the sense of the tino rangatiratanga that was guaranteed to Māori people in the Treaty of Waitangi

- working collaboratively with the partner in culturally competent ways that allows the partner to define what culture means to them.

- learning from the partner and changing one’s own behaviour accordingly (Bishop, Berryman, Tiakiwai, & Richardson, 2003, p. 202).

Current theorising in early childhood education and elsewhere has highlighted the importance of sociocultural approaches to pedagogical work (Anning, Cullen, & Fleer, 2004; Fleer, 2002; Rogoff, 2003), as well as the growing influence of narrative approaches to documentation (Carr, 2000b; Carr, Hatherly, Lee, & Ramsay, 2003; Dahlberg, Moss, & Pence, 2007; Ministry of Education, 2004; Rinaldi, 2006). Access to the narratives of others can offer alternative patterns for operating our lives (Richardson, 1997), with these transformative narratives functioning within the collective sociocultural domain and becoming “a part of the cultural heritage affecting future stories and future lives” (p. 33). Hence, narrative inquiry provides pathways whereby the transformative possibilities of collective storying can affect both educational cultures and the lived experiences of tamariki/children and whānau/families. Co-researchers in the current project, Te Puawaitanga, have explored and documented some ways in which the transformative potential (Cullen, 2003) of Te Whāriki is being realised.

This project, in enacting a Tiriti-based model throughout its design and implementation, also has resonance with kaupapa Māori, decolonising, and Indigenous research methodologies and theorising (Bishop, 2005; Colbung, Glover, Rau, & Ritchie, 2007; Jackson, 2007; Kaomea, 2004; Martin, 2007; Newhouse, 2004; G. H. Smith, 1997; L. T. Smith, 1999, 2005; Stairs, 2004).While early childhood educators are required to demonstrate that their programme delivery is consistent with Te Whāriki (Ministry of Education, 1996a, 1996b), there is evidence that many centres fall short in the depth to which they are able to deliver genuinely bicultural programmes. In 2004, an Education Review Office Education (ERO) evaluation reported that in relation to DOP 10c, whereby early childhood centres should “reflect the unique place of Māori as tangata whenua and the principle of partnership inherent in Te Tiriti o Waitangi”:

Responsiveness to “the principle of partnership inherent in Te Tiriti o Waitangi” suggests a broad view of the intent of this DOP. For example this could include explicit structures to give effect to a Māori voice within services. However this broad understanding of the Treaty is only patchily adopted and none of the reports used for this report provided information on such structures. (Education Review Office, 2004, p. 9)

The ERO evaluation concluded that “provision for diversity of cultures needs to move beyond tokenism to a deeper understanding of how service provision impacts on different cultures” (2004, p. 16). This situation has implications for teacher educators and professional development providers (Cherrington & Wansbrough, 2007; Ritchie, 2002). Research that articulates children’s and whānau voices has the potential to further extend educators’ understandings and implementation of ways of enacting Māori values and beliefs, enabling them to enhance the effectiveness of their education programmes, through an increased capacity to initiate and sustain responsive, respectful relationships with children, parents, and whānau. Warm, receptive, reciprocal relationships are fundamental to effective early childhood pedagogy (Ministry of Education, 1996b), and strategies which might enhance intercultural relationships are critical for effective teaching and learning in the Aotearoa/New Zealand context.

From the collaborative exploration of the narratives derived from the Whakawhanaungatanga project, the following findings emerged, serving as a framework for this second TLRI project, Te Puawaitanga:

- educators working in partnerships in which Māori were supportive of Pākehā who demonstrated a genuine receptivity and openness to multiple ways of being, knowing, and enactment of pedagogies

- bicultural development was enhanced by ongoing committed relationships instigated and sustained by educators sensitive to and reflective of Māori ways of being, knowing, and doing

- bicultural development was sustained when institutions and the individuals within them were committed to generating space for Māori leadership and visibility throughout the organisation

- experiences reflective of tikanga Māori enriched the early childhood programme for the benefit of all children and families involved, but were particularly significant in their affirmation of Māori children’s identity formation, and in engendering positive attitudes among non-Māori children towards Māori people and constructs

- there was evidence that early childhood educators’ fostering of a bicultural centre culture can have transformative potential beyond the early childhood centre and into the community

- there was a willingness within the early childhood community to embrace the Tiriti-based expectations of Te Whāriki, which can be nurtured with increased availability of resources to support these endeavours

- Māori engagement, participation, responsiveness, and contribution in early childhood settings was enhanced through programmes in which educators affirmed and enacted Māori values

- Māori educators and whānau preferred early childhood education programmes to reflect the tikanga appropriate to the local mana whenua

- early childhood education initiatives and models that were led by Māori reflected an inclusiveness towards non-Māori in keeping with Māori values of manaakitanga and the partnership inherent in Te Tiriti o Waitangi.

The teacher co-researchers who were our research partners in the Whakawhanaungatanga study (Ritchie & Rau, 2006) had participated integrally in both data collection and theorising and they were also involved in generating the proposal for the current project. During workshops and discussions following various presentations where we had reported on the cumulative progress of that first TLRI (Ritchie & Rau, 2004, 2005a, 2005b, 2005c), we were often approached by educators, Māori, Pākehā, and Tauiwi, from a range of rural and urban, and both teacher and parent-led centres (Playcentre, kindergarten, and childcare), for whom our work had resonance. Many expressed their interest in sharing a research journey focusing on bicultural development, which we are now terming as “Tiriti-based practice”. The current project has continued to build upon existing collaborative relationships. We consider relationships to be central not only to pedagogical processes (Dahlberg, Moss, & Pence, 2007), but also to research (Ritchie, 2002). This focus on the “centrality of relationships” (Elliot, 2007, p. 155) shapes this study, with its focus on documenting narratives of lived experiences of educators, children, and whānau within biculturally-committed early childhood centres.

This project employed narrative methodologies to provide rich, in-depth narrative accounts that give voice to key “stakeholders” within early childhood education, including children. Henry Giroux has quoted Ngugi Wa Thiong’O (n.d.):

Children are the future of any society. If you want to know the future of a society look at the eyes of the children. If you want to maim the future of any society, you simply maim the children. The struggle for the survival of our children is the struggle for the survival of our future. The quantity and quality of that survival is the measurement of the development of our society” (as cited in Henry Giroux, 2000, p.1).

Children’s voices have previously often gone unheard in both research and policy making. Te Arikinui Dame Te Atairangikaahu has highlighted the need to listen to children (as cited in Kirkwood, 2001), and this insight is supported by “a growing body of research suggesting that the participation of children in genuine decision making in school and neighbourhood has many positive outcomes” (Prout, 2000, p. 312). In Aotearoa, we have seen the beginnings of efforts towards respectful inclusion of children’s perspectives (Carr, 2000a; Ministry of Social Development, 2004; A. B. Smith, Taylor, & Gollop, 2000). In Australia, Glenda MacNaughton’s work has led the way in terms of the inclusion of children’s voice in both research and policy making (MacNaughton, Rolfe, & Siraj-Blatchford, 2001; MacNaughton, Smith, & Lawrence, 2003). MacNaughton, Smith, and Lawrence (2003) have written that:

The recent increased interest in giving children a voice in decisions about them and services for them has accompanied the emergence of new images of the young child, increased interest in enacting children’s rights in the public sphere, and increased scientific knowledge about the importance of children’s early experiences for their future as competent citizens. (MacNaughton, Smith, & Lawrence, 2003, p. 14).

The United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child continues to highlight issues around children’s participation as “full actors” in their lives (Kiro, 2005). We clearly still have “much more to learn about how to make organisations better attuned to participation, how to engage children in serious dialogue” as we seek new approaches based in a recognition of the need to include children’s voices (Prout, 2000, p. 313) within both pedagogical and research practices. Power effects are insidious, requiring a conscious effort of a process of mindful revisibilisation in order to generate a discourse of inclusion of children’s voices. As Giroux (2000) suggests,

. . . the politics of culture provide the conceptual space in which childhood is constructed, experienced, and struggled over. Culture is the primary terrain in which adults exercise power over children both ideologically and institutionally. Only by questioning the specific cultural formations and contexts in which childhood is organized, learned, and lived can educators understand and challenge the ways in which cultural practices establish specific power relations that shape children’s experiences. (p. 4)

Yet the ominous challenge remains for researchers, in seeking to elicit and honour children’s voices, as to how we can find ways to understand children’s worlds through adult eyes.

A Ministry of Education best evidence synthesis, The Complexity of Community and Family Influences on Children’s Achievement in New Zealand (Biddulph, Biddulph, & Biddulph, 2003, p. 149) has reiterated that educational provision is “most effective when operated from a partnership and empowering or strengthening approach that is responsive to the particular people and contexts involved”. As Clandinin and Connelly (2000) have pointed out, context is central to narrative inquiry. We consider that narrative research is a powerful tool (Florio-Ruane, 2001) for modelling transformative understandings about issues of culture and identities, providing rich data illustrative of the shared journeys (Rau & Ritchie, 2005). While data collection in the current study, Te Puawaitanga, has focused on a diverse group of tamariki/children and whānau/families, it has simultaneously provided an avenue for the experiences and voices of Māori educators, tamariki, and whānau Māori to be prioritised. This is consistent with current government early childhood policy. The Ministry of Education’s (2002) strategic plan for early childhood contains “a focus on collaborative relationships for Māori”, which seeks to “create an environment where the wider needs of Māori children, their parents, and whānau(families) are recognised and acknowledged” (p. 16), where opportunities are generated for whānau, hapū, and iwi to work with early childhood services, and early childhood services are encouraged to become more responsive to the needs of Māori children (Ministry of Education, 2002).

Continuing this research spotlight on changing “mainstream” early childhood practice to be more reflective of diversity was particularly salient given that demographic projections indicate “that by 2040 the majority of children in our early childhood centres and primary schools will be Māori and Pasifika” (Biddulph, Biddulph, & Biddulph, 2003, p. 10). The project’s grounding in a whanaungatanga approach to bicultural development in early childhood provision (Ritchie, 2001, 2002; Ritchie & Rau, 2006), has provided a spotlight on ways in which bicultural approaches consistent with Te Whāriki may foster Māori involvement in early childhood services, through the visible affirmation and validation of Māori ways of being, knowing, and doing. The current study broadened its lens to enhance our understandings of the experiences of the wider early childhood centre collective, highlighting experiences of a diverse range of both Māori and other children and families. In doing so it has illuminated ways that experienced early childhood educators are implementing culturally focused programmes which enhance the cultural learnings and affirm the diverse identities of children and families. It has enabled the voices of these key “stakeholders”— the children and their families—to be heard. This has been achieved by working with the early childhood educators, children, and families to document, validate, and explore the narratives of a geographically and ethnically diverse group of participants.

Aims and objectives of the research

The aims and objectives of the research were to:

- document the narratives of a diverse group of children and families as they engage with early childhood education and care services committed to honouring the bicultural intent of the early childhood curriculum document Te Whāriki

- work collaboratively with colleagues and alongside tamariki/children and whānau/families to co-theorise bicultural pathways which are empowering for all participants within that service—Māori, Pākehā, and Tauiwi. This project not only continues a focus of our earlier work on tamariki/whānau Māori within early childhood, but also expands to highlight the experiences of educators, children, and families from a diverse range of ethnicities

- give voice to the perspectives of children, parents, and caregivers on their experiences of bicultural early childhood education.

Research questions

The research questions were:

- How can narrative methodologies enhance our reflective understandings as educators on a bicultural journey?

- How do the tamariki/children and whānau/families (Māori, Pākehā, and Tauiwi) experience and respond to the bicultural programmes within these early childhood settings?

- In what ways are Māori/Pākehā/Tauiwi educators committed to a Tiriti-based curriculum paradigm, enacting ways of being that are enabling of cross-cultural understandings and that embrace tamariki/children and whānau/families of different ethnicities from their own?

The research objectives and questions are consistent with the desired outcomes of the TLRI in that they build upon the cumulative body of knowledge that links the teaching and learning already achieved with the Whakawhanaungatanga project. Existing collaborative relationships between the co-directors and professional colleagues that had formed the backbone of the Whakawhanaungatanga project were further sustained and enhanced through the focus of the current Te Puawaitanga project. Furthermore, this project has explored the use of narrative methodologies consistent with, and that enhance, the existing focus on narrative pedagogies and assessment within education in Aotearoa/New Zealand (Carr, 2000a; Ministry of Education, 2004). Narrative pedagogy, assessment, and research methodologies reflect a commitment to collective processes, recognising that communities of learning are strengthened through the coconstruction and negotiation of shared meanings (Jordan, 2004).

Ngā hua rautaki/Strategic value of this project

Addressing issues of diversity and disparity

Current government policy recognises the importance of early childhood care and education, yet discrepancies in terms of participation for Māori are an ongoing concern (New Zealand Parliament, 2007a).

According to the latest government report into socioeconomic disparities, Māori continue to be “disproportionately represented in lower socioeconomic strata (for example, lower income, no qualifications, no car access)” and that there are “widening inequalities in socioeconomic resources between Māori and non-Māori” (Ministry of Health, 2006, p. xii). Māori early childhood education participation rates continue to sit below those of non-Māori, while the proportion of Māori children aged 0-4 years is expected to increase from 27 percent in 2001 to 30 percent in 2021 (Ministry of Education, 2005).

A recent Ministry of Education-funded review of its Promoting Participation in Early Childhood Education project found that “For all Māori families, having access to ECE environments that supported Māori cultural practices and language was a key factor in participation” (Dixon, Widdowson, Meagher-Lundberg, C. McMurchy-Pilkington, & A. McMurchy-Pilkington, 2007, p. 52). Meanwhile, there continues to be scrutiny of the low participation of Māori in early childhood education, as evidenced in the terms of reference of a current “wide-ranging and timeconsuming” (New Zealand Parliament, 2007a, p. 3) Māori Affairs Select Committee Inquiry into Māori Participation in Early Childhood Education; these terms of reference are to:

- examine economic and social factors, barriers, and family (whānau) influence affecting Māori participation rates in various education programmes

- examine the effectiveness of governance arrangements for publicly funded early childhood education initiatives, and their effects on Māori

- inquire into the appropriate interventions to increase and enhance Māori participation in early childhood education. (New Zealand Parliament, 2007b, p. 4)

The recent Ka Hikitia: Managing for Success: Māori Education Strategy, 2008-2012 (Ministry of Education, 2007, p. 11) considers that there are still “a number of challenges for Māori children in early childhood education, such as the level and frequency of participation and a lack of quality options” which are indicated in the statistics which show that only:

- 87 percent of Māori children who start school in decile 1–4 schools have participated in early childhood education, compared to 94.5 percent of children overall (more than two-thirds of Māori children start school in decile 1–4 schools

- the number of Kōhanga Reo has been decreasing, from 562 in 2001 to 486 in 2006. (Ministry of Education, 2007, p. 11)

The strategy considers that “continuing to increase participation by Māori children in high quality early childhood education remains a priority” (Ministry of Education, 2007, p. 11).

The Best Evidence Synthesis prepared for the Ministry of Education on Quality Teaching Early Foundations (Farquhar, 2003) emphasises “the importance of cultural match” between home and education setting and recognises that “Ensuring a match of cultures across socialisation settings is a complex characteristic of quality teaching for teachers to meet” (p.23). In research by Hohepa, Hinangaroa Smith, Tuhiwai Smith, and McNaughton (cited in Alton-Lee, 2003, p.35), an analysis of the integration of Māori cultural norms such as whanaungatanga demonstrated “the importance of making explicit and developing cultural norms that support students, not only in strong cultural identity and social development, but also in their achievement”. It is now recognised that “Māori children and students are more likely to achieve when they see themselves reflected in the teaching content, and are able to be ‘Māori’ in all learning contexts” (Ministry of Education, 2007, p. 21). The same notion is applicable in terms of attracting whānau Māori to involve their tamariki in early childhood education.

The kaupapa of the current project was consistent with the Ministry of Education (2002) strategic plan for early childhood, Pathways to the Future, that emphasises the following three specific goals for Māori:

- to enhance the relationship between the Crown and Māori

- to improve the appropriateness and effectiveness of early childhood education services for Māori

- to increase the participation of Māori children and their whānau.

Involvement with the current project provided a mechanism “for Māori parents and educators to influence teacher education, professional development and other programmes and initiatives that support ECE services to be more responsive to Māori children” (Ministry of Education, 2002, p.13). The project also contributes to knowledge regarding effective education for Māori children and whānau within early childhood education, as well as highlighting ways in which inclusive bicultural pedagogies validate and affirm diverse cultural identities.

Strengthening pedagogical practice

This current project contributes to understandings of bicultural development in early childhood care and education, and the ways it is experienced both by Māori and others. There are distinct possibilities that the implementation of culturally aware programmes with a bicultural development focus will contribute to a widening of cross-cultural understandings (RheddingJones, 2001), and an enhancement of the acceptance of the validity of multiple world views. The collaborative nature of this project enhances links between research and practice, and addresses the TLRI strategic value of recognition of the educational challenges of providing for diversity with the intended outcome of reducing inequalities through enhanced educational involvement and outcomes for tamariki Māori, building capacity for inter-institutional research capacity, and ongoing practitioner reflection and analysis.

Ngā hua rangahau/Research value

This research has drawn upon both international and New Zealand research and new research paradigms. Julie Kaomea (2003, 2004), an Indigenous Hawaiian education researcher, has developed innovative methodology for seeking children’s voices and giving voice to marginalised perspectives. She has also employed an eclectic range of theoretical tools in her data analysis. We have been interested in exploring the potential to adapt some of the methodological and theoretical ideas that Kaomea has described in our collaborative attempts to develop effective methodologies and to then explore multiple interpretations of the data. Decolonising research methodologies (Diaz Soto & Swadener, 2002; L. T. Smith, 1999) are a relatively new field. Early childhood education in Aotearoa/New Zealand has been at the cutting edge of implementing a curriculum that honours indigeneity (Ritchie, 2003a, 2005). It is important that research continues to examine and illuminate ways in which this curriculum is being enacted.

Strategic themes and addressing gaps in knowledge

In addition to building upon current early childhood research and knowledges as outlined earlier, the current project sits alongside the Kōtahitanga research under way in the secondary sector, led by Professor Russell Bishop (Bishop, Berryman, Tiakiwai, & Richardson, 2003). Both projects can be characterised as having a common strategic theme of addressing the historical legacy of colonisation, with its undercurrent of racism, which can be viewed as continuing to contribute to the current educational and other disparities. Well-intended government policies to increase the participation of Māori in early childhood education are unlikely to succeed until “quality, culturally validating early childhood services are locally available and affordable to these families” (Ritchie & Rau, 2007, p. 111). Moving beyond deficit, victim-blaming discourses enables the identification of strategies for addressing longstanding educational disparities which instead focus on the teachers’ role within the specific educational setting (Bishop, Berryman, Tiakiwai, & Richardson, 2003). Research that identifies ways that educators within early childhood services (other than Kōhanga Reo) can strengthen their delivery of programmes towards meeting Māori families aspirations for support of their language and cultural practices can be viewed as a strategic step in reversing the ongoing educational disparities for Māori.

Substantive and robust findings

The collaborative nature of the research design and, in particular, the theorising of the research findings will deliver a high degree of credibility when the research is made available to practitioners in the field of early childhood care and education. The methodology employed enables triangulation of perspectives from three key domains: early childhood educators, tamariki, and whānau. The involvement of the educators in the development of the methodological tools and in the theorising of the data strengthens the practical application of this research, ensuring that is relevant and accessible to the field.

Ngā hua ritenga/Practice value

Central role of teacher and building research capability

The nature of this research is a collaborative and reciprocal process, honouring the role and experiences of educators. Educators have served as the central conduit in liaising with children and whānau in order to ensure that their interpretations are legitimate representations of the data being gathered (Bishop & Glynn, 1999). Ongoing hui provided opportunities for co-theorising of the overall data that has been collected. Educators have been involved in deciding ways of disseminating findings to maximise their accessibility to the field.

Relevance to practitioners/transfer to learning environment

The recent publication of the work of the Early Childhood Learning and Exemplar Assessment Project, Kei Tua o te Pae (Ministry of Education, 2004), includes a strong focus on bicultural assessment, reflected in the booklet “Bicultural Assessment/He Aromatawai Ahurea Rua”, which states that “all centres are encouraged to continue to build understanding and practice” (p. 6), with the aim that all “children actively participate, competently and confidently, in both the Māori world and the Pākehā world and are able to move comfortably between the two” (p. 7). It further states that educators should aim to ensure that “Māori and Pākehā viewpoints about reciprocal and responsive relationships with people, places, and things are evident” (p. 7). The examples of assessment in this booklet provide some aspirational examples of programmes that validate Māori values, as well as stories that highlight some non-Māori teachers’ reflections about bicultural challenges. The current project, Te Puawaitanga, has built on such work and on the previous TLRI project, Whakawhanaungatanga—Partnerships in Bicultural Development in Early Childhood Care and Education (Ritchie & Rau, 2006), providing an in-depth contribution to the cumulative body of material that employs narrative models, and which speak to the needs of practitioners endeavouring to deliver quality early childhood programmes.

2. Research design and methodologies

The project was led by co-directors Dr Jenny Ritchie, Associate Professor Early Childhood Teacher Education, Unitec Institute of Technology, and Cheryl Rau, of the University of Waikato, Hamilton. Based on our previous experiences within the Whakawhanaungatanga project we were very mindful of our role as lead researchers in this project of the need to continue to foster a climate and conditions that encouraged the educator co-researchers to exercise their own independent expertise and knowledges but that also provided them with a responsive level of support. Central to maintaining this balance was to establish and maintain a climate of respect and availability, and a shared vision for the project. A key strategy here was the initial hui, attended by all partner researchers, kuia, kaumātua, and the Dunedin research facilitator. Scaffolding of their researcher capacity was integral from the outset, whereby, at this hui, we facilitated sessions sharing ideas around ethical considerations, the nature and philosophy of narrative methodology, and how this might be applied in terms of effective data collection strategies. Collaborative relationships fostered within the previous TLRI project were extended within the proposed research project, with for example, a Whakawhanaungatanga research colleague serving as a liaising researcher, facilitating the work of the Dunedin kindergarten co-researchers. Ongoing hui occurred with all colleagues discussing and sharing strategies for data collection and co-theorising this data.

Narrative research methodologies

The earlier Whakawhanaungatanga research (Ritchie & Rau, 2006) had highlighted the voices of educators, professional development providers, and teacher educators who shared and cotheorised their knowledges about ways of involving whānau Māori within childhood learning communities. The current project built upon this base, co-constructing with educators, tamariki, and whānau new narratives around culturally inclusive early childhood programmes. We have been enacting a model whereby educators are honoured as co-researchers of the world views of their participating tamariki/children and whānau/families, in an ongoing process of generating new narratives. For Indigenous people, languages represent the reservoir of their collective knowledges, founded in a sense of community and interdependence between people and nature (Gamlin, 2003). Oral traditions are an ongoing collective process of making sense (Newhouse, 2004), ensuring that key knowledges are retained, sustained, and evolved over the generations. Sharing narratives, storying our meanings, our histories, our values, our cultures generates and reinforces our connectedness. Narrative understandings of knowledge and context are linked to identity and values, providing stories to live by, and that are lived and shaped in places and through relationships (Clandinin & Huber, 2002, p. 161). Wally Penitito has written that “full personhood is itself defined in part by one’s authority to tell one’s own story” (1996, p. 10).

Narrative is a current strategy within early years pedagogy and assessment (Carr, 2000a; Carr, Hatherly, Lee, & Ramsay, 2003; Dahlberg, Moss, & Pence, 2007; Ministry of Education, 2004; Rinaldi, 2006) and research (Clandinin, 2007; Clandinin & Connelly, 2000; Clandinin et al., 2006; Hollingsworth & Dybdahl, 2007). Teachers, children, and whānau in many centres have been experimenting with various ways of documenting their narratives. Educators in this view are thoughtful researchers whose observations are no longer about measuring children’s achievements and development against supposedly “universal” and “objective” expectations. Instead, the creation of these narrative explorations are “a process of co-construction embedded in concrete and local situations” (Dahlberg, Moss, & Pence, 1999, p. 145). Narratives are a celebration of our humanity and collectivity, whereby shared meanings and understandings are negotiated and affirmed.

The research process has been characterised by strong, respectful, and supportive relationships between all co-researchers. The input of kuia, kaumātua, the research facilitator, and the educator co-researchers obtained through ongoing discussion was incorporated into the initial proposal and research design. At an initial collective hui, all the above researchers collaborated in sharing their experiences and preferred styles of narrative data gathering processes as well as workshopping of ethics protocols. The co-directors and research facilitator maintained ongoing communication with regional cluster groups and individual centres via email, website, phone, and visits. These visits were an opportunity to discuss the effectiveness of data gathering processes, for each centre’s data to be theorised, and also allowed data gathered from other centres to be shared and wider co-theorising to be undertaken. A final collective hui was an opportunity for all the coresearchers to regroup and present their experiences, as well as another opportunity for cotheorising of key findings across all partner researchers.

Research methods

An initial hui for educator co-researchers led by the liaison co-researchers, provided the opportunity for discussion and clarification regarding both research ethics and methodologies. Educators from each participating centre planned their research strategy and timeline. On their return to their centres, they identified potential children/tamariki/families/whānau who might be interested in becoming involved in the project. They were then invited to share their experiences over time, of their participation within the early childhood education setting, once initial ethical protocols were completed. Following discussion at that initial collective hui of possible approach questions for the first set of narrative interviews, summary notes were sent out to educator coresearchers which included ideas on interview approaches and questions.

Instead of approaching tamariki and whānau with the “bigger picture” research questions, the educator co-researchers needed to find ways of gently encouraging tamariki and whānau to open up and share their stories. For example, the hui discussed how poring over a portfolio of stories and photos, with a digital audio-recorder running alongside, might be a perfect way of eliciting some rich background about what the child or adult was feeling, thinking, or imagining.

Some suggested open questions included:

- Remembering back to when you first came to the centre, what did you notice about the way we did things here? Were there any things Māori that you recall noticing?

- Can you tell me about how you felt when you first came here? How has that feeling of … changed over the time that you have been coming?

- What is one of your favourite memories of your time here? Can you tell me about a highlight from your child’s experiences here?”

Another suggestion was for interviewers to focus on a particular recent experience such as a marae visit or hāngi.

Data collection was diverse, incorporating audiotaped and videotaped interviews and transcription, field notes, photographs, examples of children’s art, and centre pedagogical documentation. Liaison researchers facilitated the data collection by educator co-researchers, in collaboration with tamariki/whānau. We (Jenny Ritchie and Cheryl Rau), the research codirectors, maintained ongoing research co-theorising conversations with co-researchers, some of which were tape-recorded as data. At a typical co-theorising hui, we and Lee Blackie, the research facilitator in Dunedin, would visit the teachers at the centre, talking with them about how things were going, listening and looking at data that had been gathered, collaboratively discussing the teachers’ sense of what was emerging and what might be useful to reflect on further. Initially, the narratives generated were analysed at the individual centre level by the educator researchers, tamariki and whānau within each setting. Educators liaised with tamariki and whānau collaboratively, identifying what was salient for them within their personal narratives. As data became available, powerpoint presentations of some examples of data collected from across a range of centres, along with reflections and suggested directions for analysis and co-theorising, were discussed during co-theorising visits. Further collective co-theorising took place first at cluster hui and then at a final hui of the wider research collective.

We, the co-directors, oversaw the smooth functioning of the website forum, the data gathering analysis, the theorising, and finally the production and dissemination of the data sets. Their role was also to ensure that the methodological paradigm was sound and practical and within the constraints and objectives of the project as approved by the Teaching and Learning Research Initiative. Narrative inquiry is fluid and responsive (Craig & Huber, 2007), forming an entity of its own process within each particular study. “In fact, narrative inquiry cannot be reduced to a research design”, yet is composed of “a number of ‘tools’ that researchers and participants use as they collaboratively make sense of their unfolding experiences” (Craig & Huber, 2007, p. 269). The research processes that emerged within the various teaching teams were consistent with the collaborative research model described in depth by Bishop & Glynn (1999) and utilise a narrative approach to methodology and cultural analysis (Florio-Ruane, 2001).

Ethical considerations

Ethical considerations involved following protocols of ensuring that both tamariki and whānau were well informed about the research purpose and processes; taking care to ensure that permissions were granted for use of photographs; and checking as to whether participants were comfortable to have their names used or would prefer a pseudonym to be used. During the twoyear period of the project, some educators and families moved on, and it was necessary to make allowances for these changes. There was awareness that a relational research ethics, particularly when working amongst domains of cultural difference, entails a disposition towards ethical considerations as constant, ongoing, and never taken for granted (Craig & Huber, 2007). Ethical questions are “ongoing, constant considerations” (Harrison, 2001, p. 228) requiring mindful attentiveness and respectful dialogue. The final draft was circulated to all educator co-researchers with the request that they carefully check that they and the families were comfortable with all the ways that their data had been represented, and to re-check consent for the use of real names. Changes were made in accordance with this feedback.

3. Findings

This chapter is framed around the study’s three research questions:

- How can narrative methodologies enhance our reflective understandings as educators on a bicultural journey?

- How do the tamariki/children and whānau/families (Māori, Pākehā, and Tauiwi) experience and respond to the bicultural programmes within these early childhood settings?

- In what ways are Māori, Pākehā, and Tauiwi educators committed to a Tiriti-based curriculum paradigm, enacting ways of being that are enabling of cross cultural understandings embracing of tamariki/children and whānau/families of different ethnicities from their own?

Narrative methodologies enhancing understandings

This section outlines some of the ways in which this project has used collaborative narrative research processes. The narrative methodology strategies employed included the gathering of raw interim narrative texts, including interview transcripts, photographs, notes of reflective conversations, emailed reflections, and other sources, which were later shaped into sets of narrative explorations through ongoing collaborative co-theorising.

Shared commitment, responsibility, and collaboration

Previous research has identified the benefits of having a shared team commitment to Tiriti-based kaupapa (Ritchie, 2000, 2002, 2003b). Many of the educator co-researchers within this study had been encouraged to participate by their head teacher, and these head teachers were sensitive to their role in supporting a collective process for their team. One co-researcher, Marion Dekker, explained that:

I have to say that I’ve probably coerced my team members into being part of this process and so like all of us we stepped onto the waka at different points and so as the team leader I felt responsible for ensuring that the team were comfortable in an area that they perhaps they were a little bit uncomfortable. So the process has been a really gentle one and yet I’m, as the team leader, feeling really delighted in the team’s progress and their acceptance and now their understanding, or their new insight as to what their practice looks like and why they do things a certain way and why in the past we’ve talked about being a bicultural society and that we as teachers have a fundamental responsibility to delivering that understanding to our children and our families, but actually how do we do that and actually who are we and how do we fit in that and if your background has been only Pākehā, middle-class Pākehā, then how does that all kind of mesh?

Marion’s comments, while demonstrating her successful steering of the “waka” during her team’s research journey, also indicate her awareness of the socio-political-historical context for our work in early childhood education in Aotearoa/New Zealand, in which early childhood educators have been progressive in acknowledging our colonial context and consequent responsibilities regarding Māori kaupapa within mainstream settings (Marshall, Coxon, Jenkins, & Jones, 2000; Helen May, 2001; Helen May, 2006; Meade, 1988; Ministry of Education, 1998; Ritchie, 2002). The following excerpts taken from Brooklands kindergarten indicate how some initial tensions within the team began to resolve over the period of time that the team collaborated on the research kaupapa. In an initial reflection, co-researcher Ramila Sadikeen articulated concerns that her colleagues had in terms of the extra work load that the commitment to the project would mean:

Today we sat down to talk about the research project and how and what is expected of the team in terms of their contribution and how it fits with all things related to the curriculum and the long term goals of the centre. I found this discussion interesting and enlightening in terms of the research participants perspective. There was focus on the research questions and how the centre is implied to be the place where the research took place. The feeling I got from this discussion is “how come you chose to do this without consultation and consent from us (team)?” I probably pre-empted the feelings of extended work load and how it could impact the work life balance. I went on to tell them that I did not envisage it to have any impact on them at all.

Evidence of the research process having been effectively shared by the team appears in a later reflection made in February, 2007, halfway through the study, on the ritual that her kindergarten enacts to farewell children who are leaving to attend school, she wrote that:

The team now thinks of this Tikanga that we follow as a ritual that is well and truly entrenched in the sum total of experiences and learning opportunities that we offer to our Tamariki and whānau. What was different from my perspective of leadership is that the team took the initiative to look at the amount of whānau that are new and also the amount of whānau that were leaving in terms of organising the date of this pōwhiri and poroporoaki and to have this ritual in the middle of the term rather than the end of the term as we have done in the past year. For the first time I felt that I did not initiate the organisation of this tikanga and that I made decisions jointly with my team as they initiated the discussion. Decision was made jointly and thereby giving ownership to the whole experience to all involved (evidence of shared leadership).

- The team is showing and taking note of the effective ways of ensuring how this ritual happens.

- They are looking at trends and thinking of the opportunities to maximize the meaningful links to the children’s learning.

- Kaiako Anne-Marie briefed the new whānau about their part in the Tikanga and the whānau were relaxed and reflected what to expect and able to take part in the ritual easily.

- Taking on leading the tamariki to say karakia before kai and ensuring that the teachers are giving clear instructions to tamariki about how much kai to take in consideration to those manuhiri who are in our presence was important. The shared leadership is evident in the way that as I stepped back, kaiako Jo stepped into this role for the children.

At the final collective hui, as the teaching teams shared stories of their research journeys, a theme emerged across the centres, of the research experience having strengthened their sense of being a team with a shared understanding. Their collaborative journey had begun at the outset of their involvement in the study, when the various teams sat down to talk about their new commitment to being part of the research, what this would mean for them, and how it might fit within their busy routines. Several of the teams used this as an opportunity to review what they were already doing in terms of bicultural implementation.

The team at Hawera outlined their process in a September 2006 progress report. Their first step had been “Informing Our Community” for which they had prepared a two-part newsletter for their kindergarten whānau which aimed to provide background about the research project, Te Puawaitanga, explaining who was involved and the aims and aspirations of the co-directors. The newsletter also explained how the teachers would participate and contribute to this research project, including the opportunity offered to two or three whānau to also be participants.

Their second step, “Informing Our Colleagues”, had included a presentation to the Kindergarten Association staff hui, at which they shared with teaching colleagues information about their involvement in Te Puawaitanga: how they came to be participants; who else was involved; their planning; the process for contributing through data collection and narratives; and an offer to provide their colleagues with updates on their progress.

The next stage, which they labelled, “Working with the Whānau”, included invitations to whānau to be involved which contained information about the project and how whānau could contribute, as well as explaining how they, the teachers, would “use” their contributions in term of sharing with the Te Puawaitanga whānau whānui. The team emphasised that this required “building respectful relationships”; sharing with them and their child profile stories, encouraging them to contribute their stories through “Parent/whānau voice”; and ongoing “listening, responding, and sharing”. The team were instinctively enacting their awareness that “Relationship is the heart of living alongside in narrative inquiry—indeed, relationships form the nexus of this kind of inquiry space” (Pinnegar, 2007, p. 249), and that “conversation is primarily an act of listening (Hollingsworth & Dybdahl, 2007, p. 170).

The team explained their understanding of their role and process as collaborative narrative researchers as requiring a strong focus on “Team Hui Time”, to:

- discuss our observations of the children, their whānau and their engagement with the programme and life of the kindergarten

- check on the progress of our plan including reviewing of strategies and adjusting timeframes and approaches

- discuss our personal perspectives

- share anecdotal data gathered from informal conversations with the whānau

- record discussion from our hui.

Hawera later reflected on their first steps within this study:

In the beginning we were…

- developing policy and procedures around the teaching team’s commitment to te reo me ōna tikanga Māori. We were beginning to explore and question ‘Is what we say we do (in policy and procedures) actually happening in practice and having positive outcomes for children, whānau and teachers here?’

- intent on reflecting Te Whāriki—its principles and strands. We desired that the children and whānau felt a strong sense of well-being and belonging here though clearly not in isolation of the strands Communication, Contribution and Exploration

- implementing Desirable Objectives and Practices, as a service requirement, and included developing and sustaining practices for on-going centre self-review

- continuing to develop as a team, which included bedding down our personal and team philosophies, our individual and team practices. We were also responding to internal and external changes occurring in the association and in our personal and professional lives.

At the end of the project, the Hawera Kindergarten team reflected on their experiences of “becoming researchers”:

What did becoming researchers mean for us?

- Can we do this? We asked ourselves questions such as “Would this mahi required of us as participants ‘fit’ within an already busy work programme?”, “Did we have anything to contribute?”, “Are we researchers?” Our first hui with all the participants answered our questions, and gave us the motivation to find our own answers!

- Finding out more about ourselves, the impact of our practices and programme, on children and whānau. The opportunity to “face ourselves in the mirror” had to be taken. We deserved to be reaffirmed about what we did well and to avail ourselves of experiences and people that would gives us the “positives” about aspects in our programme that had room for change and /or improvement.

- Commitment to doing this together, drawing on what we already know and being open to what we are yet to learn!! It was a long term project that involved, observations, documentation, hui, kōrero, implementation—above and beyond the daily programme. The team still thought it would be worth being participants!

- Exploring the processes and tools for gathering data, and presenting to others. We knew we would draw on tools for assessment, planning and evaluation that we currently used and were certain we would discover whether those tools—as well as other processes suggested trough the project—would truly capture the tamaiti and whānau voices. What would the outcomes reveal? We also knew that “sharing” with our colleagues (progress updates, stories, observations, etc) would be great learning and experience for the three of us!

Pat Leyland from Belmont–Te Kupenga summed up the importance of shared commitment within the teams at the final co-theorising hui:

You can’t do it by yourself in a centre, you actually have to have everyone else in the team on board. And I think that’s the strongest thing that has been here today, the unity of the teams, and that’s whanaungatanga.

Reviewing and reflecting

Educator teams began their involvement in the study with a focused self-review (Bevan-Brown, 2003; Ministry of Education, 2006), calling themselves to account in terms of their professional responsibilities and adherence to specific Ministry of Education expectations in relation to Tiriti-based practice. Part of the review process undertaken by various teams at the outset of their participation in this study included consideration of their kindergarten environment.

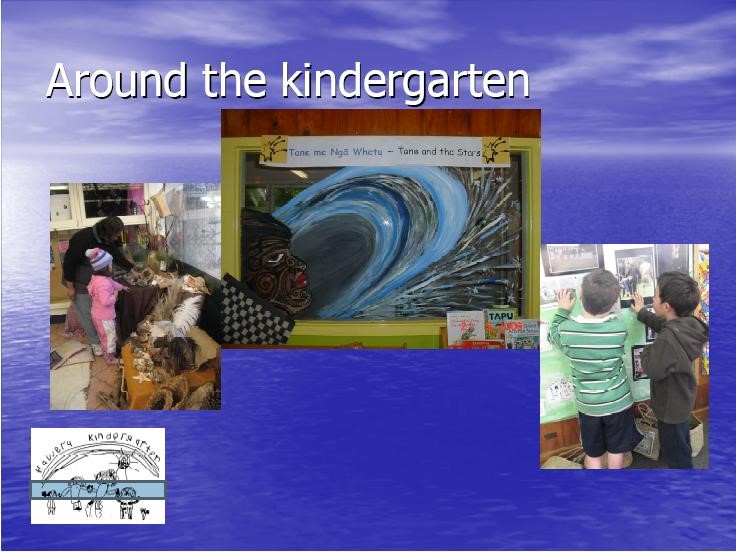

During this process, the Hawera team took a critical look at the physical layout, visuals, and presentations, with particular consideration given towards the impressions that these would have on visiting whānau (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Around the kindergarten

They noted in particular their welcoming entrance way, with the signage “Naumai, haere mai” (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Entrance way to Hawera Kindergarten

Visual narrative methodology

Photos in themselves are a rich source of data. Stefinee Pinnegar writes of the power of visual narratives to elucidate dimensions of place and representations of space:

Think of the living quality not then just of this single photo and its multiple tellings and retellings, but think of the photos in relation to others taken and untaken, told and untold, present and absent. Thus, coming to understand making meaning in a visual narrative inquiry captures the complexity of making meaning in living alongside and supporting the living and meaning making of others. (Pinnegar, 2007, p. 248)

Hawera’s first progress report also noted their inclusive focus on the “Natural Environment” within their kindergarten surrounds (Figure 3).

Figure 3 Around the Hawera Kindergarten. To look at, handle, explore, care for—from our world around us

With regard to reviewing their current practices, the team posed for themselves the following reflective questions:

- What works well for us already in terms of developing relationships with tamariki and their whānau?

- What practices have we developed to support this?

- What practices could we develop to further support?

Papamoa Kindergarten undertook a similar review as they began their participation in the project. Their first project progress report also included a number of photographs of their kindergarten environment (Figure 4).

Figure 4 Images from Papamoa Kindergarten

These visual images serve as a source of shared focus, enabling the team to revisit their everyday lived experience from a slightly objective stance. “Experience is the organic intertwining of living human beings and their natural and built environment” (Bach, 2007, p. 283). These images, “positioned within the process” of our relational narrative enquiry, “become more than photographs” reflecting the “intentionality, the negotiated, and the recursive nature” (Bach, 2007, p. 283) of the effect of the visual in contributing a “three dimensional narrative inquiry space” (Clandinin & Connelly, 2000, p. 50, as cited in Bach, 2007, p. 283) resonant of “networks of cultural meanings” (Walker, 2005, p. 24, as cited in Bach, 2007). In reflecting on their current bicultural practices, the Papamoa team listed some of these as follows:

Bicultural practices in action (July, 2006)

- Shared kai

- Washing hands before food

- No sitting on tables

- Tuakana/teina with school children coming over

- Karakia before food

- Te reo/waiata/legends/signs in English and Māori

- Greetings

- Kindergarten logo is based on the local story of the three whales.

Educator co-researchers thus grounded their entry into the formal research process in a reflective review of their current philosophy and enactment around honouring Māori knowledges and values within their everyday practice.

Choosing families

One of the first decisions for the educator co-researcher teams was to decide upon which families they might invite to participate in terms of gathering narrative data. The teachers carefully chose a range of families, including Māori, Pākehā, and Tauiwi families such as recent immigrants. They often identified families with whom they already had a longstanding relationship:

One family, we interviewed the Mum and the Dad, because they’d already had two children through the kindergarten, they had their third one here and the fourth one was going to be with us not too far away. So I felt that they knew us really well and I was interested in why they came to our kindergarten and why do they keep coming back. And the things that they shared validated what we gave to them and that was really important. (Pat, Belmont–Te Kupenga Kindergarten)

The whānau we asked to be involved in the research were ones we had very good relationships with. Only one family had had a previous sibling with us. All of the whānau involved had a good awareness of and a genuine respect for the programme we run. Sheryl (Spiro’s Mum) could see the growth in our practice from when her older child was with us about three years previously. (Richard Hudson Kindergarten)

We chose to use families that we had a strong relationship with, ones that we had had discussions with before and families that had a history with us. We also thought it was important to include our kindergarten whānau, Nana Sue and Lynette as they had continued to stay and help out. With this form of questioning we wanted to identify them as the taonga that they are and show the manaakitanga that exists in the kindergarten. (Carolyn, Papamoa Kindergarten)

The teachers shared the difficulty they had experienced in narrowing down their choice of focus families, as they would have enjoyed working closely with more than three families, but realised that time constraints made this unworkable:

It’s like who do you ask because you really want to put it up on the noticeboard and go “Oh come and you know, come and talk…” and you know you’d like everybody too but the reality of that and the busy-ness of our work is too big, so we had to limit it and so we chose to ask a family that had immigrated from England about five years ago, so new to New Zealand, and we were thinking that it could be interesting to hear how they found living in New Zealand and a bicultural society, and so we chose them for those reasons. We chose a Pākehā family and a Māori family. (Marion, Maungatapu)

Interviewing

Most of the educators transcribed their own interviews, though some were also sent through to the co-directors for transcribing. As they worked through their data, this was co-theorised with colleagues the team, with the families, and also within the wider research whānau. Discussion arose around strategies for interviewing children, as some of the teachers had found this to be challenging in terms of their ability to draw out extended dialogue, focusing on the research kaupapa. When interviewing young children, previous research has suggested that group interviews (pairs or more of children) are more likely to allow children the freedom and safety to choose whether and how to answer (Carr, 2000a; Graue & Walsh, 1995).As Vicki Stuart, from Morrinsville Early Learning Centre wrote, “I must say that I am finding it hard to get tamariki to share their thoughts with me as when you talk to them they often don’t go quite the way you want them to. The conversations seem to be going other ways at the moment”.

Here is an excerpt from Carolyn O’Connor (Papamoa Kindergarten) from her first round of data collection, of a conversation with a small group of children. In this first stage of the research process, her aim had been “to ascertain what the children understood as Māori, the things we do everyday waiata and karakia, whether children recognised things as Māori”.

| Teacher: | Do you know any Māori songs? | |

| Child: | No. | |

| Teacher: | Do you know the haka? | |

| Child: | Yes. | |

| Teacher: | Is that a Māori dance? | |

| Child: | No you go (pokes his tongue and rolls his eyes) | |

| Teacher: | Why do you do that with your tongue? | |

| Child: | Because I saw a picture. | |

| Teacher: | Do you know any Māori songs? We sing some in the morning? | |

| Child: | Morena | |

| Teacher: | Is that a Māori word? | |

| Child: | No | |

| Child: | Morena kaiako. | |

| Teacher: | What does that mean? | |

| Child: | To the teachers. |

Carolyn commented that “One of the things I found hard was interviewing children—it was kind of a struggle sometimes to get that understanding”. In adopting this adult-led style of interviewing process, the teachers felt a sense of inherent contradiction between their role as early childhood educators with our disposition of responding to children’s interests rather than formally steering conversations derived from adult agendas. As Graue and Hawkins (2005, p. 51) have pointed out in relation to their research with child participants, “interview responses are not in and of themselves indicators of any particular knowledge on the part of participants”, since they are inevitably “contingent on our invitations”. One interpretation is that the teachers, in assuming the role of “researcher” may have felt and appeared stilted in their conversations, to a certain extent unintentionally stifling the natural flow, and impeding their conversational process in terms of the vital role of being a listener (Hollingsworth & Dybdahl, 2007). Teachers as researchers “authored our interactions with particular knowledge, purposes, and intentions” (Graue & Hawkins, 2005, p. 53), the children attempting to supply the “right answers” to satisfy their interpretation of the adult’s agenda. In interpreting their role as researchers as one of asking children to respond to their questions, the teachers were somehow missing opportunities to elicit the children’s narratives as narrators of their own lived experiences (Lincoln & Denzin, 2003). As Hedy Bach (2007, p. 292) has noted, “Listening is hard work. Being available, being ‘present’, having an open heart to participants matters”. There is a very pronounced difference “between an obligatory chronicle and an animated story of the day’s events” (Lincoln & Denzin, 2003, p. 274). Power effects within the relationship between adult and child (Hollingsworth & Dybdahl,2007; Limerick, Burgess-Limerick, & Grace, 1996; Scheurich, 1995) may subvert the good intentions of the interviewer, through inadvertent disempowerment of the interviewee.

MacNaughton, Smith, and Lawrence (2003) have written about strategies that enable researchers to listen carefully to children, linking these to effective pedagogical practice. They note that it is challenging for educators to address entrenched imbalances whereby both adults and children are accustomed to children being expected to listen to adults a great deal of the time. A key strategy is for educators to “find time to listen to the children, so that the children see that staff are interested in their perspectives and feel that they can direct the conversation”, allow for respectful pauses and silences in which children feel that they have the space to gather their thoughts, and respond carefully in ways that affirm children’s offerings (MacNaughton, Smith, & Lawrence, 2003, p. 18). They also suggest that adults offer children different media for sharing their understandings, such as images, voice and text. Research facilitators in the current study suggested that educators use photos of the children engaged in activities as a focus for conversations that might draw out children’s views of what this engagement had meant for them.

As a result of their dissatisfaction with the didactic nature of some of their initial attempts at gathering data from children, we, the co-directors, discussed with the teachers various alternative approaches, also sharing written material that might provide further insight (Brooker, 2001). Teachers experimented with a range of different strategies, such as recording discussions after reading the legend of Maui and Ranginui, interviewing children in pairs or small groups, and focusing on children’s relationships with persona dolls (MacNaughton, Smith, & Lawrence, 2003).

A significant finding from this study is the discovery by Carolyn at Papamoa Kindergarten, that she gained much richer data on her second round of interviews, when parents and children with both present. Here is an excerpt from a transcript from one of these shared interviews, when Carolyn talks with both Kathryn, and Sky, Kathryn’s daughter:

| Carolyn: | What bicultural experiences do you notice your child has at kindergarten? | |

| Kathryn: | I know they have been studying Maui and the sun, just basic stuff like counting .That s about it. | |

| Carolyn: | What bicultural experiences has your child had at home that we may be able to use to find out how they feel about biculturalism in the centre? | |

| Kathryn: | We used to spend time at the marae—my partner’s marae— but not since we have been over here. We haven’t been back there for a long time now. | |

| Carolyn: | You have an extended whānau living at home. Do you speak te reo at home? | |

| Kathryn: | A little bit, not as much as I would like to. Sky was saying to me “I know the Māori word for hat. It’s Potae” | |

| Carolyn: | Where would she have got that from? | |

| Kathryn: | I don’t know. | |

| (Sky comes over) | ||

| Carolyn (to Sky): | Can you tell me any Māori words that you know? | |

| (Sky cuddles Mum) | ||

| Kathryn to Sky: | What is the Māori word for hat? | |

| Sky: | Potae. | |

| Carolyn: | Where did you learn that Māori word? | |

| Sky: | From myself | |

| Carolyn: | Do you know any other Māori words? | |

| Kathryn: | What’s this thing here? | |

| (Kathryn tickles Sky’s tummy) | ||

| Sky: | Puku! (she laughs) | |

| Carolyn: | Do you know any Māori songs? Does Mum sing to you? | |

| Sky: | Yes. Mummy knows it. | |

| Carolyn: | What parts do you know? | |

| Kathryn: | What words has it got in it ? (Kathryn points to parts) | |

| Sky: | Puku, head, shoulders.(Then Kathryn and Sky sing the song together. Beautiful to listen to says Carolyn). | |

Carolyn reported that from this new approach of sharing the discussion with children and their parents she gained much more insight into the context of her children and their families, demonstrating the centrality of context to narrative inquiry (Clandinin & Connelly, 2000):

I went into the second set of data gathering with a sense of frustration so this time I interviewed the children and the parents together. The conversation was so much more valuable I found, and I found out a lot of things, like one family speak a lot of Māori together in the home. We’ve got a lot of families that don’t go to their marae because it’s quite far away. I thought that was kind of sad for those families because they were more isolated I guess.

I had much more fun and got more valuable information from this set of interviews as I saw the value of context being important. The parents being with the children during interviews added a whole new dimension to questioning and understanding how children had experienced and consolidated learning (ako). It was beautiful also seeing that family sharing of experiences, parents enjoyed it too, children revisiting and for me seeing that cultural connection.

Later, Carolyn from Papamoa Kindergarten reflected on her overall interview process:

This indeed has been a significant learning curve as in how to obtain information by interviewing. How do you find out how children respond to the bicultural programme by interviewing and questioning them? After a few attempts and getting used to working the dictaphone (which was a necessity in the interview process) I felt that to develop clearer understandings of a child you needed to know the context in which they were talking. This was okay with interviews that were about experiences at kindergarten, but what knowledge and understanding did children bring from home or transfer between home and kindergarten? It was about seeing a child’s perspective of their life. Therefore by interviewing both child and parent it gave a richer perspective and depth of understanding of their world. Questioning became more relevant to their experiences and knowledge.

In her quest for rich sources of data and research insight, Carolyn went on to experiment with video interviewing, which proved to be a useful process of making visible the taken-for-granted.

Our next step was using the video once again how to capture the essence of children’s perceptions without running the video for the whole session. We had a wonderful parent interview that came out of asking for permission to film her child, she said “What about me? I have things to say!!!!” I feel that by using the narrative form in the last set was much more useful and again contextual.

At the end of the study, Carolyn reflected that, “Revisiting the videos we took of the children, we saw once again the integration throughout the programme. Children have these experiences every day”. This richness is in accordance with the work of Lourdes Diaz Soto (2005, p. 10), who has written that “Narrative inquiry offers a contextualized experience developed as a means of understanding events and processes across linguistic, cultural, visual, historical, and social boundaries”. Uncovering contextual factors such as temporal, spatial, and personal dynamics provides the background necessary for making sense of people’s narratives and motivations (Clandinin & Connelly, 2000). Carolyn has also responded to the “multiple story lines shaping participants’ lives” (Clandinin et al., 2006, p. 25), gaining new insights into the discontinuities that surround families aspirations to provide Māori identities for their children. Narrative data gathered in our current study involved more than interviews. Other sources of data including field notes, photographs, and centre pedagogical documentation provided a rich landscape. As Clandinin and Connelly note (2000, p. 79), the overall narrative portrait is generated from the composition of documented “actions, doings, and happenings, all of which are narrative expressions”.

Whānau involvement in co-theorising

For many of the co-researcher educator teams, the shared storying, or co-theorising, progressed to include whānau in the discussions pertaining to the research findings and process. Since the “meaning of the narratives comes from analyses or interpretations of the conversations” (Hollingsworth & Dybdahl, 2007, p. 153) in which the most important focus for the researcher should be to engage in the act of “listening well” (Chase, 2003 as cited in Bach, 2007, p. 292), this input from whānau provided invaluable understandings for the project. Marion Dekker’s team at Maungatapu Kindergarten found that responding to a research-generated discussion with parents led them to clarify and deepen shared understandings of their bicultural commitment, and further, to identify a focus for enactment of this:

So we set up the process that we’d been advised to, as competent women here, and then we embarked on some interviews and I guess the thing about the interviews were that in those group discussions it would spark a response from our teaching team and it was a bouncing of ideas really and so they were really, really great, and we got some good sort of responses. One family that have recently immigrated, we spoke with the mother and it was interesting because she absolutely, was eager to embrace bicultural thinking. She just had a really open, warm heart to people, and yet actually underpinning some of her thinking was also very strongly a multicultural thinking, and so we found that reasonably interesting to try and unpack a bit, that actually her background was very much influenced by a range of different multicultural experiences through her childhood as we found out through her stories. And so although she wanted to embrace biculturalism, and she was really excited about what she was seeing in the kindergarten, she still had a really strong feeling and value that actually we as people live in a very multicultural world and so how does that fit? So that was good for us to be able to unpack that a little bit more and talk about first and foremost that living here in Aotearoa is about living in a bicultural world. We were able to really sort of talk through some of that with her and again that was really good for the rest of the team because it helped us to then focus on what we were delivering in our programme. It was about being able to focus on what it is that we were wanting to really see being represented and really see strongly there, which brought us to wanting to have more emphasis in the environment. So we went on a journey of creating a wharenui in the kindergarten and with the support of one of our other parents, Josie, we went on this journey . . .

At the final co-theorising hui, Marion had shared her team’s process with the other project coresearchers, reflecting on how their curiosity as to what constituted “Māori” aspects within their programme had been stimulated, to the point that they sought clarification from whānau:

So I guess, you know from the outset, as a team we’ve had lots of discussions about that and we’ve been really fortunate to have a number of different whānau come in and just kind of talk along side us and help the team to identify with some of the things that we do that are Māori.

The following exchange is an example of the depth of this collaborative dialogue as the teacher (T) and Pākehā mother (M) discuss their understandings around the bicultural nature of the programme at Maungatapu Kindergarten, beginning by reflecting on how their personal perspectives have evolved over time:

So it’s interesting to think about actually what is it about culture that living in New Zealand in a bicultural environment that you are going to feel comfortable exposing your children to, be it through this environment and ongoing?

| M: | When we were growing up we … were all friends we didn’t have any issues so how come today we do? I thought it worked back then. There must have been a respect for each other but lack of understanding do you think? | |

| T: | I think you might have hit the nail on the head there. Did we actually acknowledge there was two cultures there? | |

| M: | Right. Not at all and we didn’t, did we? All of us just conformed to it. | |

| T: | “Conform”—that’s a really interesting word that you use, because it was about conforming really, wasn’t it? And so whose culture were we conforming to?” | |

| M: | English of course. | |

| T: | So it’s interesting to think about actually what is it about culture that living in New Zealand in a bicultural environment that you are going to feel comfortable exposing your children to, be it through this environment and ongoing? | |

| M: | Obviously there is a blend here already and it’s been enhanced. You’re doing a good job, girls. Do you think the feelings thing of being happy and warm comes from the Māori culture? | |

| T: | Being happy and warm? | |

| M: | The feeling here of that warmth and that acceptance of people, you know how some people can accept whoever, whatever and love? Now not everybody has that skill to do that. Now do you think that is from the blending of biculturalism or is that you guys’ personality?” | |

| T: | I would say it’s a combination but I think it is enhanced when one can acknowledge that they are dealing with two cultures and so there is difference and an acknowledgement of that and then some things are valued at different points. I think we try really hard to emphasise and value relationships so it might appear that we are saying “Oh the coffee’s hot! Come and have a coffee”, but actually in a Māori sense that is very much about making sure that when people come into our place they feel at home . . . | |

| M: | Exactly so by incorporating those two models . . . And I was wondering whether that feeling is because of that? | |

| T: | I think it’s an ongoing awareness isn’t it? We are all teachers that have been brought up in a Pākehā society so it’s a learning curve for us. . . | |

| M: | For everybody. | |

| T: | Yeah, everybody. Everybody within the environment. The more you learn, the more comfortable you feel. | |

| M: | Oh, absolutely because the fear is taken away. | |

| T: | Yeah, and it’s also permission to speak the language and to be adapting some aspects of their culture in this environment. You don’t feel like you are overstepping the mark or being fake about it or it’s tokenism. I don’t want to seem like I am trying to be in their culture I don’t want it to seem like it’s a token gesture. | |

| M: | You couldn’t always feel like you could do that because they might look at you like. . . | |

| T: | You didn’t want to offend anyone. | |

| M: | Whereas now you can do that and no-one feels. . . | |

| T: | The cultures have blended more. I feel that’s a part of my culture now and who I am, I am a New Zealander, you are immersed in it and it comes more naturally now. | |

| M: | Yes I would agree with that. | |

| T: | It’s really neat work you are doing with your boys and that you are allowing them to be exposed to biculturalism in a really positive way and I guess the flip side of that is for parents I think it’s really useful to acknowledge that there is difference. We blend it together but we don’t all actually want to be in the same melting pot. It’s okay to be different and that’s what’s so unique about New Zealand so it’s wonderful that we have an acceptance and a level of understanding and that we can live in harmony but actually it is the partnership of two cultures working beside each other and occasionally we cross but we don’t have to cross. | |

| M: | But we have to understand and respect each other. | |

| T: | Sometimes it’s about acknowledging that to the children and it feels a little bit awkward like you are making a point but otherwise it’s just assimilated in them. You want them to be able identify difference. . . but at the same time you still need to be treated equally. I think the biggest thing is there is difference and that needs to be embraced. | |

| M: | I agree. |

Marion also valued the input from children to generating understandings of their experiences: