1. Aims, objectives, and research questions

Background to the project: Two curriculum documents in Aotearoa New Zealand

The overarching aim of this research in the proposal was the following:

In a number of early childhood centres and early years school classrooms that have already begun to explore in this area, to investigate effective pedagogy designed to develop five learning competencies over time.

This project was developed in response to curriculum reform in Aotearoa New Zealand. When the project began, the Ministry of Education was undergoing a review of the school curriculum. This review began in 2001 with a Curriculum Stocktake Report (Ministry of Education, 2002) and continued throughout 2005 and 2006. The draft New Zealand curriculum was published in 2006 (Ministry of Education, 2006), and after further feedback the final document was published in November 2007 (Ministry of Education, 2007). Justine Rutherford (2005) and Sandra Cubitt (2006) provide an overview of this curriculum review process.

Background to the project: Learning competencies, key competencies, and learning dispositions

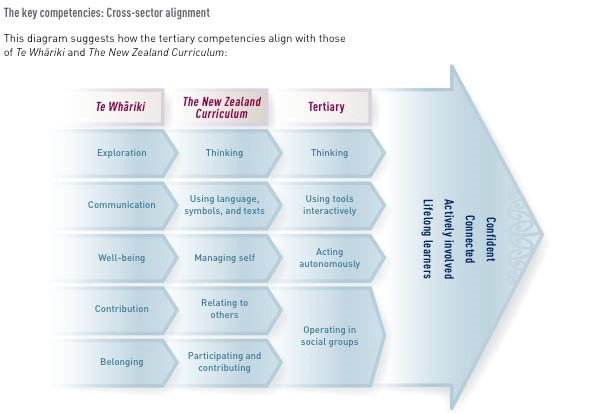

The school curriculum review included the development of five key competencies for the school curriculum. These were aligned with the five curriculum strands in the early childhood national curriculum, Te Whäriki (Ministry of Education, 1996) in a diagram on page 42 entitled The key competencies: Cross-sector alignment. It is reproduced here as Figure 1.

Learning competencies in the title of this project is a composite term for the key competencies in The New Zealand (school) Curriculum (Ministry of Education, 2007, pp. 12–13) and learning dispositions in Te Whäriki, the national early childhood curriculum (p. 44). In the discussion in this report all three terms will be used, depending on which term is most appropriate to the context. Key competencies is used when early-years schooling is discussed; learning dispositions is used when the context is early childhood education (settings for the under-fives), and learning competencies is used for generic situations covering both early-years schooling and early childhood education.

The Te Whäriki document summarises the learning outcomes in the early childhood curriculum as working theories and learning dispositions. It states that knowledge, skills, and attitudes combine together to form a child’s “working theory” and help the child develop dispositions that encourage learning. There are five named key competencies in the school document: thinking, using language, symbols and texts, managing self, relating to others, and participating and contributing. The five strands in Te Whäriki do not include five named learning dispositions: a range of learning dispositions is included in the indicative outcomes under the sections that elaborate on the strands of exploration, communication, well-being, contribution, and belonging. Early childhood teachers have been working with learning dispositions for some time, as the early childhood resource Kei tua o te pae (Ministry of Education, 2004, 2007, in press) illustrates.

Figure 1 The key competences. Cross-sector alignment (Ministry of Education, 2007, p. 42)

Key competencies and learning dispositions, as described in the two curriculum documents and as defined in this research project, include three aspects: sensitivity to occasion, inclination and ability (Perkins, Jay, & Tishman, 1993, used this triad to describe thinking dispositions)— sometimes called being ready, willing, and able (Carr, 2001). They are very similar categories of outcome, best illustrated by aligning quotes from the two documents (Table 1).

|

The New Zealand Curriculum (2007) |

Te Whäriki (1996) |

|---|---|

| The key competencies (pp. 12–13) |

Learning outcomes (pp. 44–45) |

| More complex than skills, the competencies draw also on knowledge, attitudes, and values in ways that lead to action . . . (p. 12)

|

In early childhood, holistic, active learning and the total process of learning are emphasised. Knowledge, skills, and attitudes are closely linked. These three aspects combine together to form a child’s “working theory” and help the child to develop dispositions that encourage learning. (p. 44) |

| As they develop the competencies, successful learners are also motivated to use them, recognising when and how to do so and why. (p. 12)

|

An example of a learning disposition is the disposition to be curious. It may be characterised by: an inclination to enjoy puzzling over events; the skills to ask questions about them in different ways; and an understanding of when is the most appropriate time to ask questions. (p. 44) |

| The competencies continue to develop over time, shaped by interactions with people, places, ideas and things. (p. 12) | Children learn through responsive and reciprocal relationships with people, places, and things. (p. 43) |

| They are not separate or stand-alone. They are the key to learning in every learning area. (p. 12) | Dispositions provide a framework for developing working theories and expertise about a range of topics, activities and materials that children and adults in each early childhood service engage with. (p. 45) |

| Opportunities to develop the key competencies occur in social contexts. People adopt and adapt practices that they see used and valued by those closest to them, and they make these practices part of their own identity and expertise. (p. 12) | Dispositions to learn develop when children are immersed in an environment that is characterised by well-being and trust, belonging and purposeful activity, contributing and collaborating, communicating and representing, and exploring and guided participation. (p. 45) |

Background to the project: Prior research by teachers

Early in the curriculum review process it became apparent that this alignment between the two sectors (early childhood and school) would be developed. Margaret Carr and Sally Peters were invited by the Ministry of Education to explore aspects of the alignment, and in 2004 a one-year research programme was carried out by teacher-researchers and university (Waikato and Canterbury) facilitators. Nine projects explored practice that would now enable teachers and communities to describe aligned learning pathways across the early childhood and school sectors (Carr & Peters, 2005; Peters, 2005). In those projects, the composite term “learning competencies” was introduced. Many of the teachers in this Final Report’s 2005-2007 project were also involved in the 2004 projects.

Many writers are researching or writing about dispositional aspects of learning from a number of perspectives—and using a number of names: intellectual habits (Sizer, 1992), mindsets (Dweck, 2006), patterns of strategic action (Pollard & Filer, 1999), habits of mind (Costa & Kallick, 2000), thinking dispositions (Perkins et al., 1993; Ritchhart, 2002), learning dispositions (Carr, 2001), and learning power (Claxton, 2002).

Aim one: A theoretical understanding of learning dispositions and key competencies

The first aim of this project was to contribute to a theoretical understanding of learning dispositions and key competencies. The texts in Table 1 indicate that they have been ecologically framed (a close connection between the individual and the environment): they include when, how, and why to use the skills or abilities associated with them; they are shaped by interactions with people, places, ideas, and things; they are integrated with the content in learning areas; and they are closely connected to social contexts. So theoretical ideas from writers like Urie Bronfenbrenner (1979) and Sasha Barab and Wolf-Michael Roth (2006) are relevant.

The term “key competencies” is borrowed from an OECD DeSeCo (Definition and Selection of Competencies) project (Rychen & Salganik, 2003) who also support this perspective. An ecological framing is summarised by Barab and Roth (2006) in terms of what it means to know: knowing is “participation in rich contexts where one gains an appreciation for both the content and the situations in which it has value” (p. 3). They state that what it means to know includes the following:

- knowing is an activity—not a thing

- knowing is always contextualized—not abstract

- knowing is reciprocally constructed in the individual–environment interaction—not objectively defined or subjectively created

- knowing is a functional stance on the interaction (connected to an intention)—not a “truth”.

The curriculum documents—and the literature—thus set out learning dispositions and key competencies as ecologically framed, situated (Lave, 1996) and distributed (Salomon, 1993).

The objectives for this aim were to contribute to the theoretical literature on key competencies and learning dispositions, and to delineate key features of learning competencies (learning dispositions and key competencies) in a range of settings.

During the school curriculum review process the names of the key competencies were changed by the curriculum writers. In the 2007 document the earlier “making meaning” was changed to using language, symbols and texts; and the earlier “participating” or “belonging” was changed to participating and contributing. As will become clear in the findings in this report, teacherresearchers in schools developed local interpretations of the key competencies from their experience in practice and in dialogue with students, colleagues and sometimes families. Similarly, the early childhood teacher-researchers continued to develop their understandings of learning dispositions in ways that broadly aligned them to the key competencies: thinking as recognising and constructing exploration of the world and responding positively to difficulty or failure along the way; using language, symbols and texts as (multi-modal) communicating; managing self as an holistic competency to do with well-being; relating to others as relating to others and making a contribution to the community; and participating and contributing as learning dispositions to do with belonging. In the early childhood curriculum, relating to others and making a contribution are combined in the curriculum strand, Contribution. Table 5 and the associated text illustrates the early childhood discussions around learning dispositions in one context. For the teacher-researchers in early childhood centres and in schools, these learning dispositions and key competencies intersect and intertwine.

Aim two: Enhancing learning dispositions and key competencies

The second aim was to find out more about how teachers enhance learning dispositions and key competencies. Classroom research from New Zealand by Jane McChesney (2004) was relevant here. McChesney used a sociocultural approach to explore mathematics learning in secondary school classrooms. She described the learning of number sense as distributed across classroom interactions, social norms, and cognitive and technological tools, and she researched the role of the teacher in all of this. This is somewhat reminiscent of the principle in Te Whäriki that children learn through responsive and reciprocal relationships with people, places, and things and of the new school curriculum comment that, “The competencies continue to develop over time, shaped by interactions with people, places, ideas and things” (Table 1; Ministry of Education, 2007, p. 12). The literature names these people, places, ideas, and things as the “opportunities to learn” (Gee, 2003) or “affordance networks” (Barab & Roth, 2006). The objective for this aim was to investigate the opportunities to learn and the affordance networks that contribute to learning dispositions and key competencies. What do they look like in five diverse sites, and how do learners respond to them?

In a commentary on learning outcomes in curriculum, Hargreaves and Moore (2000) argued strongly for high discretion granted to teachers and local initiatives: “these possibilities include fostering stronger collegiality among teachers, and democratic inclusion of pupils and parents in the teaching and learning process” (p. 27). Therefore we were interested in this project as not only researching learning competencies in five sites, but also recognising and documenting the processes of collegiality and democracy in teaching and learning that are required as teachers make learning competencies their own. These discussions are included throughout, but especially in the Findings for Research Question Two.

Aim three: Continuity and progress of learning dispositions and key competencies

The third aim was to explore progress or continuity. How do learning competencies progress, improve, or develop over time? If key competencies are situated in local contexts, then what does it mean to say that they have progressed, improved, or developed when local contexts change?

The analysis of change over time, or “transformation” of participation (Rogoff, 2003), or trajectories of learning (Wenger, 1998), is not just a matter of observation; it will need a theoretical framework informed by research. Rogoff and Wenger do not give clear guidance on this. Nor do Rychen & Salganik (2003). There is an extensive literature on the transfer of learning, and we have not summarised it here. We were interested in the continuity and transfer of key competencies and learning dispositions. The objectives for this aim were to investigate case studies of the development of learning competencies over time and to develop a way of conceptualising their growth or increasing strength.

Research questions

In a range of schools and early childhood settings that have already displayed initiative in teaching learning dispositions and key competencies, what do the children do in these diverse contexts when they are apparently managing self, relating, making meaning, thinking, and participating in desirable ways? How do children interpret these actions?

How do teachers in a range of contexts enhance continuity and growth in five domains of learning competencies: managing self, relating, making meaning, thinking, and participating? How do they interpret these actions?

How do teachers enhance continuity in learning competencies over time, within and across settings? How do they interpret that continuity?

2. Research design and methodologies

Practitioner inquiry

(W)e use the term practitioner inquiry to refer to the array of educational research genres where the practitioner is the researcher, the professional context is the research site, and practice itself is the focus of study. (Cochran-Smith & Donnell, 2006 p. 503)

This was an action research project (Kemmis & McTaggart, 2000), one of this array of educational research genres. Action research is commonly used to describe collaborations among school-based teachers and other educators, university-based colleagues, and sometimes parents and community-based activists (p. 504). Action research can “connote any individual or joint effort to produce some kind of curricular or schooling change” (p. 504); it can also be critical and emancipatory. Reflexivity is characteristic of action research (p. 504).

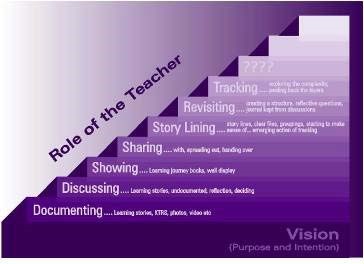

Frequently, action project designs are described in terms of a spiral of self-reflective cycles or steps, and one of the criteria of success is whether participants have developed a stronger and more authentic sense of understanding and development in their practices, and the situations in which they practice (Kemmis & McTaggart, 2000, p. 595). Many teachers teach intuitively, and an opportunity to reflect on their implicit practices is enlightening and helpful. However, practitioner research, in collaboration with university researchers (and, in this case, three coordinators who were also university researchers) also has a capacity to construct theory and to contribute to an understanding of knowing and learning that goes beyond the local. Our assumption was that “practitioners are among those who have the authority to construct Knowledge (with a capital K) about teaching and learning” (Cochran-Smith & Donnell, 2006 p. 508). In this project, for instance, teacher researchers developed a particularly powerful metaphor of teaching and learning, and a dynamic network of “big ideas” was developed from all of the work by the research team.

Marilyn Cochran-Smith and Kelly Donnell (2006) note that “serious challenges to the idea (of practitioner research) have been levelled by university-based researchers and others since at least the 1950s” (p. 504). They list: (a) the knowledge critique (practical knowledge or craft knowledge is different to formal or theoretical knowledge) (b) the methods critique (practitioners’ capacity to conduct research on their own professional contexts is challenged), (c) the science critique (scientifically based research is held to be the authority for educational policy: comparison among alternatives, cross-site analyses, controlling and testing for the effect of particular variables, standardised tests—the “effectiveness paradigm”), (d) the political critique (practitioner research ought to be always primarily about issues related to power, equity and access) and (e) the personal or professional development critique (practitioner research is conceptualised as a vehicle for personal or professional development rather than as a mode of knowledge generation or critical praxis). However, we agree with the authors that action research or practitioner inquiry can interrupt traditions and blur traditional boundaries. They ask whether it is possible or desirable to do research that privileges the role of neither practitioner nor researcher, but instead forges a new role out of their intersections.

Certainly, notions of validity in practitioner research tend to be different from the traditional. Anderson and Herr (1999; also taken up by Carr et al., 1999) write about criteria for the validity of practitioner inquiry as: democratic (finding ways to include a range of stake-holders and perspectives), outcome (resolving problems—or, in our case, dilemmas, and deepening their understanding of their practice), process (data collection and analysis methods), catalytic (keeping the practitioners interested and excited) and dialogic (critical and reflective discussion for analysing practice). All of these validity processes emerged in some way or another during this project. They are critical for developing tools of travel: ideas and resources that are useful for other teachers. These “tools of travel” include ways to listen to other perspectives and the value of doing so, collaborative pathways towards consensus about dilemmas that assist other practitioners to question their assumptions, data collection and analysis methods of value to teachers, ways in which even small action research projects can be “catalytic”, documented discussions about practice together with provocations and working theories as starting points, and artefacts that assist practitioners to find ways to include a range of stake-holders, to resolve problems and to keep teachers interested and excited.

Teacher learning

This research was primarily designed to develop ideas and examples that would be accessible and useful for other teachers in early childhood and school settings. This means we need to outline our assumptions about teacher learning. A useful background on the assumptions that underpin this project is provided by Peter Kelly (2006). He compares the literature on teacher knowledge and teacher knowing, and argues for “teacher knowing”. He says:

Lave and Wenger (1991), Wenger (1998) and Billett (2001) argue for a view of both coming to know and knowing-in-practice as processes which, rather than lying entirely with the individual, are distributed across all participants in professional practice (including in this case teachers and students) and which relate to both the conceptual and the physical resources available. (p. 509)

This view of teaching is consistent with the view of key competencies and learning dispositions as situated and distributed. Kelly includes ideas about teacher learning also being ecologically framed and he comments on the importance of “affordance networks” in the environment. He defines affordances in the context of school practices: “Affordances are the participants’ (often shared) expectations of the kind of things which can be said, thought or done during their engagement in particular social practices” (p. 510). He adds:

These ideas provide the basis for a more complex view of teacher learning and student learning as outcomes of a dynamic relationship between teachers’ and students’ conceptual resources, the physical resources available, and the affordances and constraints of the classroom. (p. 510)

He describes two alternative views of the relationship between research and teacher learning. In the first of these, an instrumental view:

Researchers and government inspectors survey expert teachers to discover good practice. These ideas are distilled and presented to other teachers to apply in their own classrooms, and expert teachers demonstrate how this might be done. (p. 512)

In the second view, which Kelly writes is based on problems and which we came to call in this project a “dilemma-based” view:

Decision-making is collective and inclusive and …. an important vehicle for school improvement is collaborative practitioner enquiry…. Expert teachers will be those who engage fully in reflective, discursive, collaborative and inclusive practices to improve their work with colleagues and students. Expert students will be those who become able to do the things which count through collaborative activity and discussion, and who can therefore engage in different ways of knowing.

This project was characterised by reflective and collaborative processes about a range of dilemmas or dissonances that these teacher researchers were interested in tackling. The project is therefore about the dilemmas, and about—in five sites—the constructing and reconstructing of teachers’ knowing through practitioner inquiry. It is not about identifying what expert teachers look like, although there are some findings about categories of expertise that were valued in particular settings. The project provided contexts and opportunities for teachers to discuss together (a) within sites, (b) with a co-ordinator, (c) with a university researcher, (d) across a research team of one or two key practitioners within one site, a co-ordinator and university researchers, and/or (e) across the entire research team.

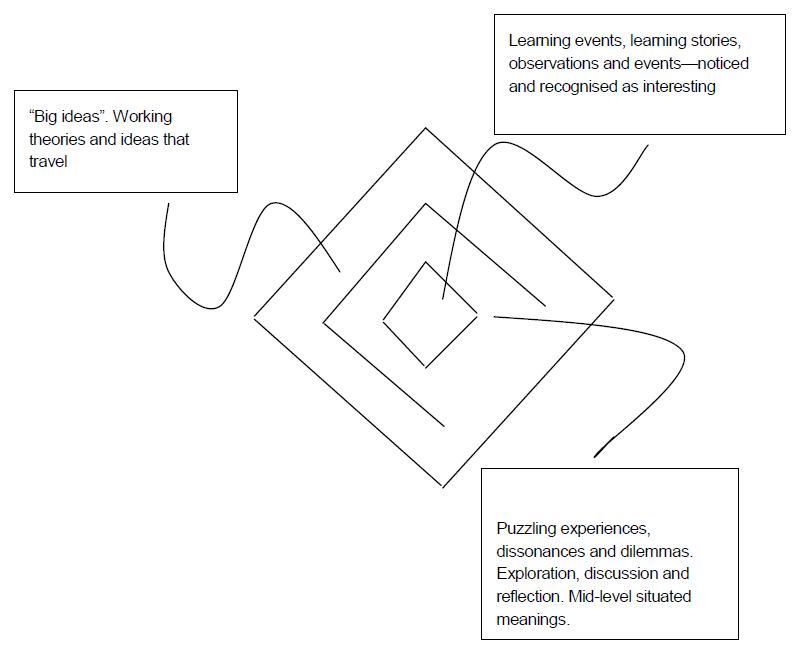

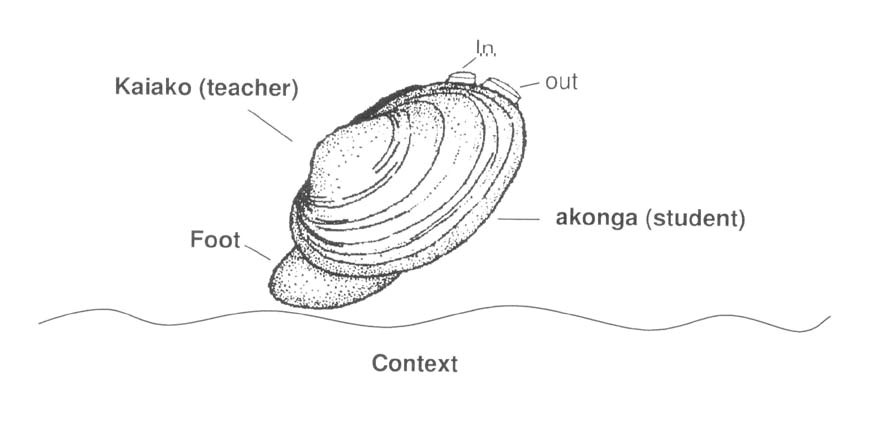

The design of the project

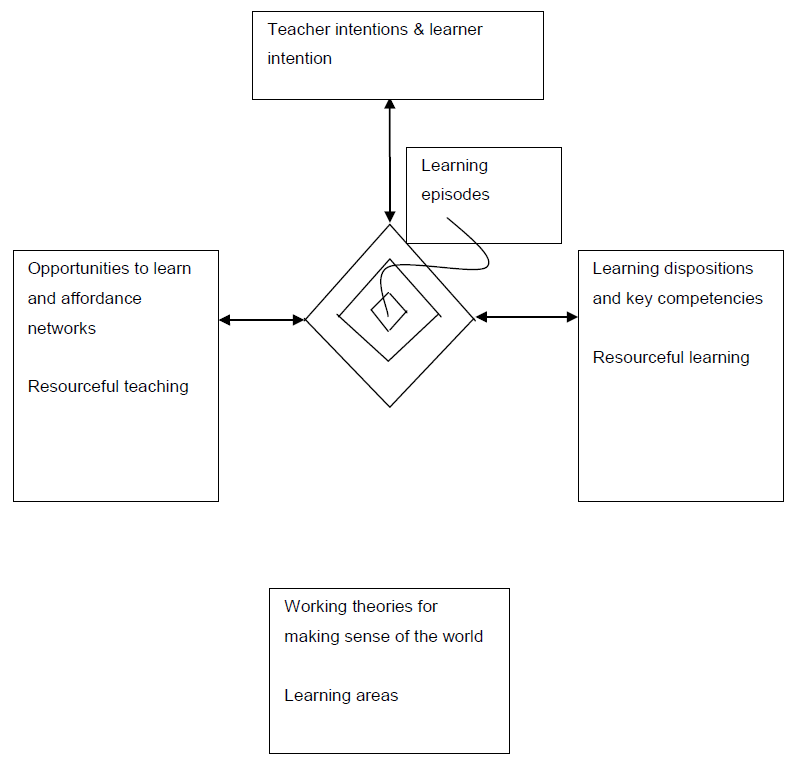

Figure 2 is the centrepiece of another diagram (Figure 9) that summarises the findings of this project (see chapter 6). It is also about the design of the project. In the centre are the moments and events of interest to teacher researchers (or brought to their attention by observing or participating researchers, or students, or families). Some of these raise dilemmas or dissonances that are puzzling enough to warrant some discussion and reflection, with the aim of resolving the dilemmas or improving the education at this site. The reflections develop what James Gee (1997) has called “mid-level situated meanings”. Mid-level situated meanings are discussed further in chapter 6. Some of these “mid-level” ideas can develop into working theories and “big ideas”. Lee Shulman and Judith Shulman (2004) comment that “As so often happens … theoretical work was stimulated by a specific set of puzzling experiences” (p. 258) and “A central conjecture of our model [of how and what teachers learn] is that reflection is the key to teacher learning and development” (p. 264). In our case this theoretical work developed in reciprocal and responsive interactions both in and beyond the teaching team in any one site, and in the writing of working papers. The working papers assisted in the articulation of ideas, and they provide a concrete resource for assisting the ideas to travel.[1]

Figure 2 The design of the project

Method

Research sites

The research was carried out in five sites: two childcare centres in Christchurch (Aratupu Preschool and Nursery and the New Brighton Community Preschool and Nursery Incorporated), early years classrooms in two schools in Christchurch (Parkview School and Discovery 1 School), and a primary school in Rotorua (Rotorua Primary School).

Aratupu Preschool and Nursery is a community-based early childhood centre situated in Papanui, Christchurch. The centre is one of several services offered by the Christchurch Methodist Mission alongside social work services, advocacy, budgeting and food bank services, and aged care. Aratupu provides education and care for children aged 0–6 years and aims to meet the needs of the local community, who are predominantly young single women-led families who rely on a benefit for their source of income. The roll at Aratupu comprises approximately 50–60 percent Māori children, with the remainder consisting of Pākehā, Asian, Samoan, and Cook Island children. The centre is licensed for 8 under-two and 31 over-two-year-olds.

New Brighton Community Preschool and Nursery Incorporated is a community-based early childhood centre, which has been operating since 1979 in a seaside community in Christchurch. The centre provides care and education for a lower socioeconomic community, which has a high transient population. The centre has both nursery and preschool areas with a maximum role of 9 infants and toddlers and 30 preschool-aged children attending at one time. Part-time enrolments mean they have about 95 children on their roll. Approximately 72 percent of the children are European/Pākehā and 20 percent are Māori.

Parkview School is a Years 0–8, decile 4 school in Parklands, Christchurch. The school community is varied both ethnically and socioeconomically. The school roll is around 280, with approximately 78 percent New Zealand European/Pākehā and 14 percent Māori.

Discovery 1 School is a Years 0–8 decile 6 school situated in the heart of the Central Business District of Christchurch. The school roll is about 175. Approximately 82 percent of children identify as European/Pākehā and 9 percent as Māori.

Rotorua Primary is a co-educational state primary school that caters for Year 0–8 students. The school is located in the heart of the Rotorua central business district in close proximity to Lake Rotorua. The school roll is about 260, with 97 percent of the children at the school identifying as Māori. Seven Māori bilingual classrooms and five English-medium classrooms operate in the school. The school is built on tribal land that was gifted by Ngati Whakaue chief Rotohiko Haupapa for the expressed purposes of education.

Participants

Teacher researchers from the three schools and two early childhood centres in Christchurch and Rotorua worked in partnership with Margaret Carr and Sally Peters, from the University of Waikato, who, as the project directors, provided research assistance and advice. Three research co-ordinators (from University of Canterbury and University of Waikato) who already had a relationship with the teachers were invited to participate because of geography and cultural connection (Keryn Davis, Sue Molloy, and Tina Williams). They provided ongoing support for the teacher researchers.

Teacher researchers gained consent from teaching colleagues, children, and their families to include them as participants in the project.

Mixed methods and multiple perspectives

The methods of collecting and analysing the data were diverse, depending on the context and the specific purpose (Sammons et al., 2005).

Teachers at each site recorded episodes of their teaching in a range of ways. In some sites this included continuous narrative recording and event recording (by a co-ordinator or by the teacher researcher observing children and colleagues) to document classroom practice, and identify examples of learning episodes that appeared to illustrate the key competencies.

Semi-structured interviews were used to gather data from teacher researchers, teaching colleagues, other schools’ staff, children, and families. Later in the project the co-ordinators were also interviewed about their role.

Teacher researchers wrote or recorded discussions of key episodes or sequences of learning episodes with other teachers. In some cases staff meetings and other discussions were taperecorded.

Teachers developed portfolios or profiles of children over time and reflected with each other and with co-ordinators and university researchers about the strengthening of the children’s capabilities, the match or mismatch with what teachers “knew” about the children, and the relevance of the cues or indicators[2] that were used (leading to changes in cues or indicators). The children’s perspectives were included in these portfolios, as well as documented in wall displays about the key competencies.

Strategies for developing effective relationships and partnerships

A number of strategies were employed that may have been helpful in developing strong relationships and partnerships.

Time: The length of the project (three years) was probably of significance for the teacher researchers to take on the research as their own. To use Carol Dweck’s (2006) categories about learners (linked to attribution theory), they began with “performance goals” (with external evaluators—Sally and Margaret—as reference points) and shifted towards “learning goals” (their own interests and contexts—in discussion with the outsiders—as reference points). As the project progressed, however, after a team meeting in February 2007 where the university researchers presented some ideas that attempted a distillation of the interesting dilemmas that were emerging, a collective reference point appeared to also develop. The commitment to “collective goals” may only have developed when the teacher researchers at each site were confident—and continued to be confident—about the value of their own contributions.

An earlier short project: The first strategy for the development of strong relationships and partnerships was an earlier short project completed before the TLRI proposal. This established a relationship between the university researchers and a cohort of teachers who became interested in research (Carr & Peters, 2005):

I went back and spoke to our staff about the key competencies and what I had learnt from that initial mini-research that we did and they were excited way back then because they could also see what I had seen that it was holistic, that it was what we were doing at Rotorua Primary School. In fact, after all these years of doing it in Rotorua Primary School, we had a hanger to hang it on, meaning the name “Key Competencies”. (Interview with Mere, 3 Dec 2007)

Co-ordinators: The second strategy was using co-ordinators who already had a relationship with the teachers. Two of these co-ordinators were university-based professional development providers in Christchurch; the third was a university-based co-ordinator with iwi connections to, and a strong relationship with, the teacher researcher who led the project at the Rotorua School. Two co-ordinators, Tina Williams and Keryn Davis, talked about their roles as follows:

Really working in the school, trying to maintain the links with the school and establish a relationship and rapport with everyone in there so I tried to become, especially when it came to the observations, part of the furniture so they didn’t see me as an outsider … That’s a definite role in giving back something to the school like designing the website was a big thing for us because it was a chance to show that we were giving something back … to the school as a whole because they were giving us so much in terms of the information and that access …

An important role of co-ordinator is to make those relationships between the school and to bridge … not a gap, but bridge the distance sometimes between what we do at university and all the academic work … one of the characteristics we talked about was that it was important to become multi-lingual when you’re doing a project such as this, and we weren’t referring to Māori and English. We were referring to those, plus the academic language, plus the classroom and curriculum language, and the language of the children as well, so you had to be quite skilled in what you are doing. I think that’s the key role of the co-ordinator, and trying to keep the relationship with the person you’re working with really, really strong and yet push them so that they’re actually reaching it. (Interview with Tina, Dec 2007, p. 4)

… in this project [compared to an earlier study] I was still an outsider, but much less so. The teachers knew me and I knew them, and though it was their project and their interests being explored I was closer to the action. I guess I liked the support/facilitation role, rather than being the one who held most of the control over what was included, or, I don’t know, even the starting point, it just wasn’t my project I guess and so it has a different feel to it. While it [the project] was collaborative, they [the teachers] retained the majority share if you like. They talk about it as theirs but also as ours. The “our” being the wider research team. I do the same. It’s theirs but at the same time it is ours. There’s acknowledgement and respect for what each person has brought to the mix. I guess they have individual identities within the whole. They have retained their identity and ideas throughout the project, while still being part of a bigger thing.

I think that’s a strength of this type of research, the participants have ownership over their own ideas and work, and I think that’s something I feel comfortable with ethically. There’s tensions, or risks in there though of course, but I think the teachers made decisions about those things, they were weighed up at the time and they did what they felt comfortable with. They were committed to idea that their work was something to learn from, for themselves and for other teachers out there. (Notes from Keryn, January, 2008).

Team meetings: Another strategy was team meetings. Because of the distance, the Christchurch and Rotorua teams met independently from each other more frequently than the whole team, but it was valuable to come together twice a year. Relationships developed across the sites that appeared to be both personal and professional. Three babies were born, and these personal events were celebrated by us all. At meetings the baby-whispering was distributed across the entire team.

Working papers: A key aspect of the design was the writing of working papers by the teacher researchers, often in collaboration with the co-ordinators. The university researchers wrote two papers during the project, and are preparing others. One teacher commented that the papers she had co-authored were just the kind of papers that she liked to read: short, accessible, and with clear examples. At the same time, writing their ideas down clarified and deepened their ideas, (and the ideas of the university researchers). The writing of working papers contributed not only to the outputs of the project, but also, in the view of the university researchers, to a sense of ownership of the project by the teacher researchers. They distributed the ownership and authority, and research indicates that this is a feature of teacher learning (Clarkin-Phillips, 2007 p. 7). It has meant that when anyone in the team wants to cite the work of the project, appropriate referencing and acknowledgement can be made to the teacher researchers by quoting them as authors. The first working papers were a bit of a struggle, and the university researchers decided to discourage the writing of working papers during the second year because of the time it took away from gathering data. This appeared to be a wise decision. Then, perhaps because a model had been established in that first year, 10 further working papers had been written in first draft by early December in the final year. Some teachers and co-ordinators plan to write further papers from their data, so the work of the project has a pathway for continuing into the year after the official project is completed.

Barriers

From the university researchers’ perspective, one of the barriers was probably distance. The university researchers visited Christchurch regularly, and the teacher researcher from Rotorua visited the University of Waikato on a regular basis. The university researchers also maintained contact by email and telephone between face-to-face meetings. However, the majority of betweenvisits contact was with the co-ordinators. The role of the co-ordinators was therefore that of an enabler but also it was also a potential barrier because the co-ordinators were closer to the “engine-rooms” of early childhood setting and classroom practice than the project directors.

Without close communication and trust this could have been problematic. However, in practice we found that the strength of the relationships and the shared history prior to the project, between the university researchers and the co-ordinators and between the co-ordinators and the teacher researchers allowed this design to work.

In a three-year project teacher researchers were able to develop their understanding of research methods over time. A dilemma for university researchers was the extent to which time should be devoted to this at the beginning of the project, as not being too directive did allow for teacher ownership of the research.

So I went in completely and utterly blind, having no idea what was going to be expected … Never did I imagine we’d be at this point … I always saw research as being (a) way too academic for me, but (b) a sort of separate project that went alongside something that wasn’t … that wouldn’t have given us this much value to this place. So, I didn’t understand how much we would own it … (Interview with Andrea, August 2007)

Ethical issues

Approval for this research was gained from the School of Education Ethics Committee at the University of Waikato. There were no unforeseen ethical issues.

3. Findings

The findings are presented in four main sections, with each section relating to one or more of the research questions. The first and second sections discuss findings for the first and second research questions respectively, namely what learning competencies look like for learners and what teachers do to enhance them. The third section looks at aspects of the first and second questions combined, and the final section discusses findings in relation to the third research question, namely how teachers enhance continuity of learning competencies over time. The discussion variously refers to learning competencies (a composite term for key competencies and learning dispositions, applicable to early years schooling and early childhood education), key competencies, and learning dispositions, depending on which term is most appropriate to the context; for example, key competencies is used when early years schooling is discussed, learning dispositions for early childhood education, and the learning competencies for generic situations covering both early years and early childhood educaton.

As noted in chapter 1, the research questions were formulated before the key competencies in the new school curriculum were finalised, and thus use the terminology of the draft key competencies. In 2007, the Ministry replaced “making meaning” as a title with “using language, symbols, and texts” and “participating” (which has had a chequered career of name change) became “participating and contributing”. Also, the research team replaced “children” with “learners”.

Learning competencies and learners—research question 1

This section discusses findings in relation to the first research question, which asked: “In a range of schools and early childhood settings that have already displayed initiative in this area, what do the learners do in these diverse contexts when they are apparently managing self, relating, making meaning, thinking, and participating in desirable ways? How do learners interpret these actions?” The findings draw from data in different sites, and discuss:

- the difference between children’s and teacher perspectives

- the ways in which key competencies can be integrated with the learning areas of the curriculum

- the significance of context

− a critique of key competencies in the particular context of a school where Māori immersion and English-medium classes work side by side

− a critique of learning dispositions in the particular context of a setting for infants and toddlers

- a reflexive investigation of one disposition and its parallel key competency (relating) in one setting.

The difference between children’s and teachers’ perspectives

At the Discovery 1 School site, the teachers in the composite new entrant/Year 1/Year 2 homebase (the word used for a classroom space at this school) were exploring the definition of key competencies in three ways: developing a range of indicators for documentation; talking and developing ideas about a different key competency each term; and reflecting on teaching that was designed to enhance key competencies. All three of these strategies changed their ideas. This section summarises the findings for the first two of these (the third is summarised in the next section which discusses findings related to the second research question). Nikki O’Connor, one of the teachers in this homebase, commented as follows:

When I was developing the indicators that might help us at Discovery to recognise the key competencies, I was able to carefully consider the values that I hold as an educator. Although I work at an alternative school and have always been conscious of my developing pedagogy, I found the process of choosing indicators to be a valuable tool for studying my practice and beliefs. As I began to write Learning Stories using the new indicators, I became aware that the stories that really excited me were generally stories that illustrated one or more of the indicators. The significance of this is the fact that I am discovering more about myself as an educator, about the connection between what I value, what I teach, and what I recognise as meaningful learning. The implications of this are twofold. Firstly, this process can empower us as educators. It allows us to explore our own values, attitudes and beliefs and to examine our practice, critiquing its elements and understanding whether or not what we are doing complements our values. This in turn, allows us to shape our practice. This process also allows us to see directly the links between how we function as teachers and the influence this has on our tamariki. (Working paper D1)[3]

The “Learning Story”[4] of Lucas in Discovery 1 School’s first working paper demonstrates this point by detailing a situation in which Lucas’s actions had been directly influenced by the culture of the homebase, or class space. It reflects attitudes, values, and a disposition that Nikki aims to model to the children, and the following indicators are checked: choosing the right strategy for situation and self (thinking), exploring and expressing, and interpreting and understanding (using language symbols and texts), honouring and respecting Te Tiriti o Waitangi and honouring and respecting others (relating to others), and acting within the bigger picture or wider context (participating and contributing).[5] (See Appendix 1: Lucas’s Learning Story.) Nikki comments:

I went on to develop these indicators with the support of other educators, a process I found very useful. If the team of teachers at each school were to develop their own indicators that reflected the values of the school (in consultation with their community), the values of the teachers and the values of the tamariki, imagine how powerful an exercise this could be.

I shifted “caring for the environment” from the competency [of] managing self to belonging, participating, and contributing. This was after feedback from several people that this could be a more appropriate place for this indicator. I also changed the wording of “relationships” to “relating” to keep in line with the other key competencies.

By 2007, the teachers had begun to invite the children to brainstorm their ideas. These ideas were added to a focus board, together with stories about children learning, using the children’s words. Examples for three of these key competencies—“managing self”; “relating to others”; and “belonging, contributing, and participating”—are shown in Table 2.

After completing some activities where they tried something new (for example, some of the girls tried a Lego activity that they had not tried before; some of the boys tried dancing when they had not participated in this before), the children were asked what it looked like and what it felt like (Table 3).

Table 2 Indicators (or cues) for key competencies: Discovery 1 School

| Managing self Teachers 2005 |

Managing self Teachers 2007 |

Managing self Children 2007 |

| Experimentation Persisting Risk-taking Knowing self as learner Taking responsibility for learning Planning |

Perseverance Attempting new experiences/ taking risks Self motivation/taking responsibility Planning/establishing intentions and avenues for learning Commitment to plans, intentions, ideas/following through/integrity Identity/knowing self as an individual and as a learner Awareness of the effects own actions have on others |

Managing yourself and not hurting other people Not need for teachers to boss you around … so, like, teachers don’t have to do anything Being sensible so other people don’t get hurt feelings Try to listen to people Don’t say any swear words Don’t run around in the school Don’t punch people on the noses Don’t push people down the stairs You should listen to other kids if they say “Stop it, I don’t like it” |

| Relating* Teachers 2005 |

Relating to others Teachers 2007 |

Relating to others Children 2007 |

| Honouring and respecting self as a unique individual Honouring and respecting Te Tiriti o Waitangi Honouring and respecting others |

Interacting co-operatively and constructively Negotiating/managing and resolving conflict Open to learn from others/development through interaction Accepting of diversity/ recognising different points of view Respect for self as a unique individual Considering others/sensitive to the emotional well-being of others Honouring Te Tiriti o Waitangi |

Treating others as you would like to be treated Letting people join in Thanking people that help you Sit next to someone new Listening to people Show new people around the school |

| Belonging, participating, and contributing* Teachers 2005 |

Participating and contributing Teachers 2007 |

Participating and contributing Children 2007 |

| Recognising and sharing uniqueness in self and others Trusting (self, others, place and process) Acting within the bigger picture / wider context Caring for environment |

Contributing to quality and sustainable physical and social environments Connecting and engaging with people, communities, places and things Being resourceful/sharing Participating and contributing activity in new and existing roles Having a sense of place and belonging Acting within bigger picture/wider context Trusting self, others, place and process |

Doing something you haven’t done before Joining in Caring for other people Persisting Doing things with other people Trying and trying and feeling good in the end Giving things a go |

| What does participation look like?

Girls and boys doing anything together Joining in Girls and boys dancing Discussing Working together and co-operating Helping each other People persisting Sharing Cleaning up

|

What does it feel like to participate?

Great and good It feels cool Good to do something different Super good Excellent Powerful Liked it A bit nervous It feels super duper … great A bit embarrassing |

The value of listening to the children’s perspectives was highlighted in these discussions. In the discussion on managing self, the teachers introduced planning and “knowing yourself” as ideas. The children were puzzled by the adult’s idea of “knowing yourself”, and they searched for meaning:

Because someone might say “What’s your name” and then just like I said “Um I don’t know”

Because you need a name or nobody knows you.

It means that you don’t have a name.

If someone’s new they might be feeling shy.

Or if you include somebody else and they’re new and if you include everybody that wants to play the game and you know there’s no more balls you could just grab a ball from another game and have that one and then you’ll all be included.

The teachers adopted the children’s words, and they also used stories to illustrate their own ideas and cues. For instance, they used a story called “Keep Trying” (by Jane Buxton) in a discussion about persisting. During the reading of the book the children contributed their own examples: “And Nikki, that’s what I did. I couldn’t ride on my roller skates but now I can.” (And did you keep persisting with it? “Yep”). The teacher notes how, in the book, the children are supported to keep trying.

| Nikki: | … and you can see Dad’s here supporting him when he’s learning to ride. It’s always good to have someone helping you when you’re learning new things and guiding you through. |

| Child: | That’s what I needed in my Highland dancing because Highland dancing is really hard. If you ask me, the teachers keep supporting me in my Highland dancing and soon I’ll be able to get up on stage at school maybe and show you the Highland Fling. |

Later work in Discovery 1 School and in other settings on a balance between teacher intentions and learner intentions (see especially the discussion in the third section, on the first and second research questions combine) was mirrored in the way in which there was, here, a negotiation between the teachers’ conceptual understandings and the children’s conceptual understandings. This allowed them to move forward together with a recognition of each other’s perspectives about what key competencies or learning dispositions look like here. Teacher researchers trialled and documented ways to surface the children’s understandings (brainstorming, developing targeted activities and discussing them, asking for an interpretation of an adult word phrase (for example, “knowing yourself”)). They also documented the ways children expressed their interpretations— using concrete examples and analogies. They trialled ways to teach their own understandings: reading stories with a “dispositional” message, and suggested their own analogies from their knowledge of the children’s prior learning episodes. As we shall see later in this chapter, the teacher researchers themselves used metaphors and analogies as they attempted to make sense of the research findings. These processes began to point the way towards some strategies for constructing an understanding of the teaching and learning of dispositions and key competencies (see especially the third section discussing findings relating to the first and second research questions combined).

School improvement … is not merely a matter of “rapid response to changing market forces through a trivialised curriculum”, but a question of dealing with the deep structures of school and the habits of thought and values they embody. To manage school improvement we need to look at schools from the pupils’ perspective and that means tuning in to their experience and views and creating a new order of experience for them as active participants. (Ruddick & Flutter, 2000, p. 75)

This research links to New Zealand literature on seeking the pupils’ perspective or the child’s voice (for example, Smith, Taylor, & Gollop, 2000). It also suggests the value of analogy and analogical thinking (Holyoak & Thagard, 1996) for these complex dispositional outcomes. Araceli Valle and Maureen Callanan (2006) reported on two studies of parents mapping analogical relations for children; parents are particularly adept at this because they notice and recognise the opportunities for analogy in children’s relevant prior experiences. As this research indicates, teachers can become adept in this area, enhancing children’s conceptual understanding of key competencies and learning dispositions (as well as other understandings, for instance in science: Inagaki & Hatano, 1987)—especially if they know the children well.

Integrating key competencies with school curriculum learning areas

The research at Parkview School was introduced by the teacher, Yvonne Smith, in an early working paper (P1):

I decided to explore how the draft Key Competencies could be integrated into the daily programme, and assessed, without creating extra workload for teachers already struggling with an overloaded curriculum. Literacy and numeracy are the main thrusts in the Junior classes so I decided to start with these curriculum areas, hence the research question “How can the draft key competencies be integrated into literacy and numeracy?” (Working paper, p. 1, p. 3)

Ten Learning Stories in that working paper illustrated the way in which this integration was implemented—and documented. These stories include the children learning in pairs and in groups, providing opportunities for an analysis of “relating to others” and “participating and contributing”. They illustrated the way in which the pedagogy smoothly integrated learning areas and key competencies. Table 4 includes four examples.

| Learning Story | The integration | Key competencies |

|---|---|---|

| “Reuben’s Mask” | The specific learning intentions here were speaking clearly, listening, and asking questions. Reuben gave clear instructions and explanations to the other children on how to make a mask. The teacher comments that “When children asked me for help I referred them to Reuben”. And “They helped each other with ideas and encouragement” | Thinking (explaining ideas)

Relating (assisting each other) Participating and contributing (leadership in the class community |

| “Ella’s Worm Hotel” | The teacher gives Ella a reading book about building a worm farm. She talks at news telling time about the worm hotel she has made at home. She describes the process and answers the children’s questions. | Participating and contributing (deep involvement). Managing self (setting a task and completing it). Thinking creatively (a worm hotel) and logically (describing the process). Using language etc. (the book as a source) |

| “Pacey is Teacher” | Pacey leads a shared reading lesson, demonstrating extensive book knowledge and a bank of sight words. Teacher hears her own voice as he says “Reuben, can you find ‘said’?”, “Chloe, come and find a full stop”…. | Participating and contributing (Pacey takes initiative, and does not often take a leadership role) |

| “The Big Toe” | Teacher and children read the book “The Big Toe” together, and children are invited to change the text by thinking of words they could use instead of “big”. They begin with “giant” and “small” and the teacher provokes them to go beyond size words by suggesting “squashed”. They read through the story substituting “frozen” for big. Children returned to read the big book independently. | Participating and contributing (taking risks to share their ideas)

Thinking creativey and critically |

This narrative method of documenting learning in portfolios was of interest to the families, inviting another perspective on these unfamiliar dispositional outcomes. It introduced families to the key competencies, and some families added stories from home. One of the project coordinators, Sue Molloy, interviewed six parents in June 2007:

I think with the explanation of the Key Competencies, Mrs Smith seems to use key kind of words throughout all of them, so it’s easier for me to link them back to previous ones that are about the same kind of thing, to see the growth … because the wording is really clear on what competency it’s dealing with. (ZH)

I actually did [write stories] for Lily. I took some photos of her when she was learning to ride her bike, which she mastered a couple of weekends ago, and got Lily to write a story about riding her bike. And we did it at home and we brought it in to show Mrs Smith, and that went into her portfolio. So it’s not even stuff that you write, it can be … get the kids to do something outside of school and that can still go in as well. It’s Lily’s words. I typed it up for her and we put the photos on and it came to school. (WE)

There is evidence from parent interviews that some of the children were taking an interest in the documentation at home and seeing connections in the learning over time.

Actually this time around K has had a lot more to say about what’s in the book. The first time it was like “Oh, can’t remember, can’t remember” and even though there were pictures he’s still be, like, “Oh I don’t know” and didn’t really want to talk about it. But this time he has actually wanted to talk about everything that has been in it. (LT)

I think the pictures [photos in the portfolio] are great because you can sit down with your kids and they can explain what they were doing and it’s just so nice. And when people come around you’ve got your portfolio to show them and you keep them. It’s great. (LW)

In this research, the portfolios have provided opportunities for children to gain—and express—an understanding of their learning, mediated by teachers and families. These processes can begin as research methods, where the consequences are carefully documented, and then translate into pedagogical strategies.

The significance of context—Māori immersion and English-medium classes

This section presents a critique of key competencies in the particular context of a school where Māori-immersion and English-medium classes work side by side.

Mere Simpson, the teacher researcher at Rotorua Primary School, presented a 30-minute session on the key competencies at a staff meeting in August 2005 and at this meeting an invitation was extended to all the teaching staff and the management to become involved in the research. Eleven research participants agreed to take part (two members of the senior management team, five Māori medium classroom teachers, three English medium classroom teachers, and one teacher education student), and all eleven were interviewed by Mere between September and November that year to find out their views on key competencies at this school.

One of the statements to emerge from the initial conversations at Rotorua Primary was the following comment made by John:

One box does not fit all, what is important to some schools may not be important to other schools … You have got to look at what is important to your school and what is going to be effective in your school.

The researchers at Rotorua primary (Mere and Tina) commented later as follows:

John’s statement really made us think carefully about the special nature of Rotorua Primary School. In what ways, if any, would this context influence the interpretation and expression of the key competencies?

What would the competencies of relating to others, managing self, thinking, using language symbols and text and participating and contributing look like here? It wasn’t long before we recognised that the key competencies would take different forms in different contexts , including different cultural contexts.

It all connects

Although many of the teachers had little knowledge of the new curriculum at this point, there was considerable agreement that the competencies all connected. Metaphors were used to describe this connection: whiri (plait), flow, well made bread.

That’s another thing, whaea, I’m looking at it all, whiri, whiri, it all connects you know. (Judy)

People do not just use one competency at a time. They use a combination of key competencies. (Trevor)

They really do flow into each other. They are already in process. It is just when you look at them separately, okay they have their own story but when you look at them together it is like a well made bread, like your mixture of pudding or something, once they are out together you just can’t separate them. They are just wonderful together—binding. (MISSMT)

The importance of belonging (participating and contributing), managing self, and relating to others

The three key competencies of “belonging” (participating and contributing), “managing self” and “relating to others” were seen to be central:

So, all those key competencies that are down there, you have to have a balance of the lot, especially the first three. If the first three have got that balance then it makes it easier to do the last two. (John).

So to me, those two—pursuing knowledge and using language symbols and texts—as a teacher from an academic point of view, I would really like to see my children become really, really skilled at that. But that is not to neglect the belonging, managing self and relating to others because without those, if you can not behave yourself and you can not work with others and you can not belong to a group in a classroom, then you are not going to be able to sit still long enough to listen and learn. You know you are going to miss out if you can not learn those others. So I think those competencies belonging, relating to others, managing self, without those, the child will have more difficulty pursuing knowledge and using the language, symbols and texts. (Puawai)

I think it is really important that they do realise that they have a place here and I think if you have got the belonging part instilled in them, then the rest of these: Managing self, relating to others sort of fall into place. (Frances)

Judy mentioned that belonging was especially important in the Māori-medium context that she worked in. Establishing connections with whānau was viewed as vitally important:

Probably, the belonging. That’s the one in our school itself, it’s deep, hōhonu. I believe that if the child knows that they belong in some way, whether it be just their little toe, or whether they belong in that kura, they’ll just thrive, you know. Like most of the children in my class, I know their parents. So that sense of belonging and they know that if they play up I could just see Mum or Dad. That’s that whānau, that sense of belonging. (Judy)

For Auntie, belonging was important especially for someone who was not a member of the majority group (which in this particular school is Māori). She claims that:

Belonging is something that is very important and I feel I belong here, even though I am from a different culture. It is the belonging thing, to be part of a cultural institution, that is really, really important. (Auntie)

The holistic nature of the key competencies

At the end of the project Mere carried out a second round of interviews with the staff. The holistic nature of the key competencies sat comfortably with the philosophy of these teachers.

I think in this draft curriculum document they’re a good set of key competencies and it’s really good because it relates to just about everything you do within your classroom and school environment, especially amongst our school participating and contributing and I did hear that belonging’s added into this part of the key competencies so I think the really important part for my class making sure that all the kids feel as though they’re participating and contributing to the classroom environment which in turn makes them feel as though they belong in the whole school wide area as well. I think they’ve very good, very compact and easy to understand and I think as a teacher easy to incorporate into the things we do in the classroom. (Frances, Interview 2, p. 1)

The benefits I think … is that it does come down to being more personal and they [key competencies] inter-link with everything we do. Part of the school culture, part of our own personal culture and it just adds more value to our student’s learning and to our way of teaching as well … It all inter-relates to our planning. When we plan our units, even if its maths, it all inter-relates. As I said before, personal … learning how to manage themselves, getting themselves prepared and its all building on their own personal self-worth and so once they know what they’re doing they participate and contribute better and when they contribute it spurs others on …. The communication one and the managing self and the relating to others. I think that’s the key in any classroom because if you don’t have those, you need to build a bond between the children themselves and other children within the school so I think they really play a really key role. (MISSMT, Interview 2, p. 1)

School values are central

The descriptions of the key competencies in the New Zealand Curriculum are generic—leaving room for local interpretation. This is a very significant feature.

… it depends on the community … I think a Māori community, I mean we talk about communication and things like that, I mean if you’re looking at maybe the different communication skills that are used on the marae and the ones we use for jobs, we need to look at the variations and how they are going to help everybody. (John, Interview 2, p. 1)

Mere and Tina comment in a presentation to the New Zealand Association for Research in Education conference in 2007 as follows:

Māori culture, history, language, and values are a fundamental feature of the philosophy, practices and processes at this school. The school values are: tapu (sacredness), kawa (customs), whanaungatanga (relationships), aroha (love) and manaakitanga (caring). It is not surprising therefore that the nature of the key competency, relating to others, would reflect a Māori orientation.

In the second phase of the research in this school, the researchers set about identifying and recording features of pedagogy and school practice that strengthened the learning competencies. After they had completed all of their observations, they looked at the data and found that most of the episodes revolved around the key competency of relating to others (see Appendix 2 for examples).

Dominique Rychen and Laura Salganik (2003, p. 105), writing about key competencies, propose the notion of constellation “to represent the interrelated nature of key competencies and their contextual specificity”. They suggest that the specific contextual nature and the relative weight attributed to key competencies within a constellation may be influenced, for instance, by cultural norms. Rose Hipkins (2006, p. 6) refers to this aspect of the DeSeCo key competencies. The researchers at Rotorua Primary School conclude as follows (in working paper R2).

Research data that we have gathered appears to support this claim. More weight may be given to a specific competency because it aligns well with the cultural context. In our case, we found that the majority of the episodes that were recorded were based on the competency of relating to others. This is hardly surprising when Whanaungatanga is identified as a key value in the school and is also a fundamental feature of Māori culture itself.

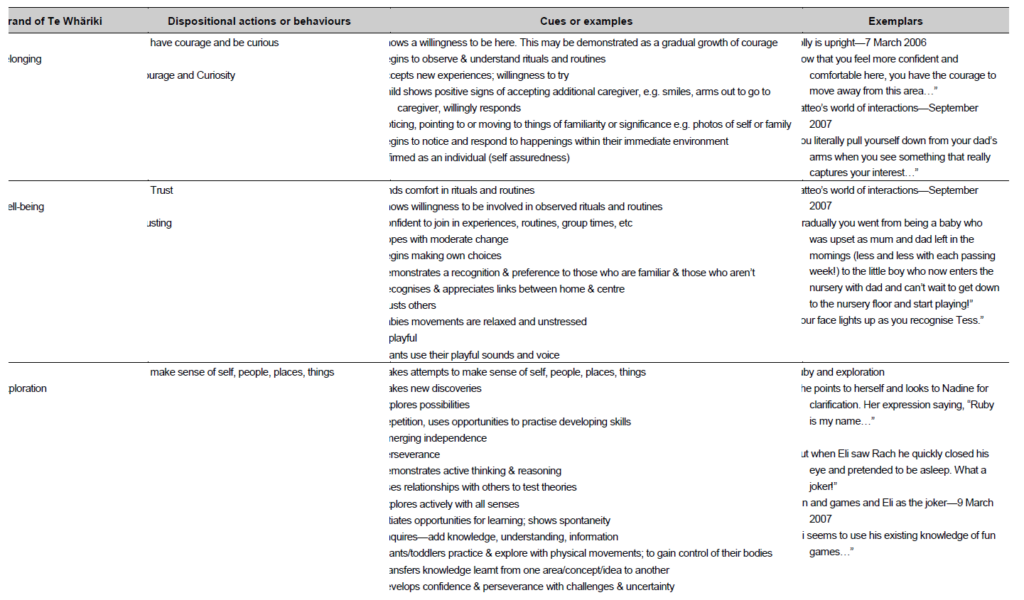

The significance of context—infants and toddlers

This discussion presents a critique of learning dispositions in the particular context of a setting for infants and toddlers.

A dispositional framework, aligned to the curriculum strands of Te Whāriki, has provided the basis for Learning Stories in a number of settings in the early childhood sector for some years. The strands of Te Whāriki, in turn, correspond to the key competencies identified in the new school curriculum (Ministry of Education, 2007, p. 42). Two of the teachers in the infants and toddlers programme at New Brighton Community Preschool and Nursery, Claire and Nadine, had begun to think about whether this particular framework of learning dispositions that they had been using, from the Learning Story framework set out in Carr (2001) needed some alterations to align more with the actions, behaviours and special characteristics of infants and toddlers. Their dilemma and discussions are outlined in a 2007 working paper (NB4). They noted that

It wasn’t the notion of dispositions we had a problem with, rather it was the language of the framework that didn’t seem to correspond to the learning we wanted to describe, but neither of us felt we were qualified to alter the framework to make it fit …

Keryn (one of the co-ordinators of the project) had suggested that we talk through our ideas at [a meeting with the university researchers, Sally and Margaret]. We took some persuading, as the thought of us suggesting the idea that the framework didn’t work very well for us was too bold a move. Despite this we shared Ruby’s story and hesitantly touched on the idea of wanting and needing to change the language of the framework.

Sally and Margaret invited us to draft our thoughts and ideas into a new framework. Excited at the chance to get some infant and toddler relevant language we gladly accepted the challenge. With a great sense of anticipation, but a high level of motivation, it was time to start gathering and formulating our ideas. (pp. 1–3)

They returned to Te Whāriki, and after “many, many hours of discussion”, often linking their ideas back to the children for whom they had been writing stories, they developed some cues and examples that better recognised the dispositions in their setting.

On the advice of Magaret and Sally we read through old Learning Stories we had written and considered if and how these stories sat with our framework. Through this exercise we discovered even more cues and examples to add to our draft framework. By using “our” stories and “our” children we could be sure it was relevant and authentic to our context. (p. 7)

Table 5 was developed by Claire and Nadine to illustrate their revised learning dispositions framework.

Table 5 Dispositions in the nursery: New Brighton Community Preschool and Nursery

Ed note – this table appears as per the source material on file

In an interview, Claire and Nadine comment that this project provided them with the opportunity to “stray a little from the norm, well, from what has always been done. And think outside the square for a bit” (interview, 21 August 2007). They also said that as a result of all the discussions about the language of dispositions, they were noticing things differently. One of the teachers commented that “now I have a much wider realm of things that I notice and therefore respond to”.

A reflexive investigation of one disposition (relating)

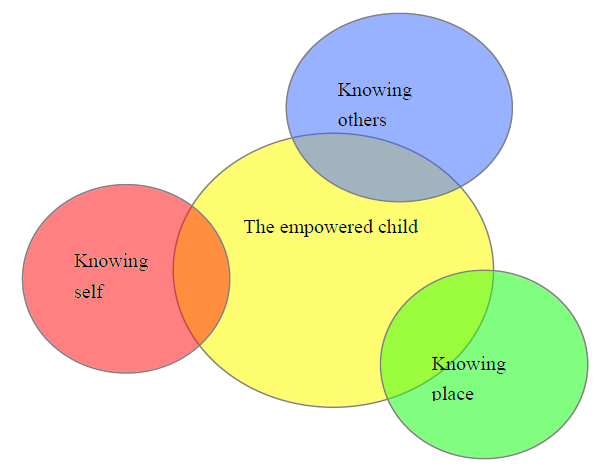

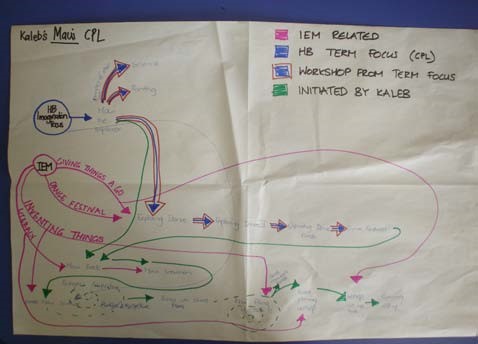

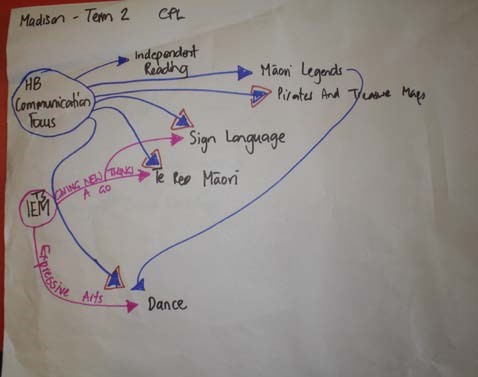

At Aratupu Preschool and Nursery, the main research question was “what does relating look like for children here?” Three domains of competent “relating” (with place, others, and self) were combined to describe “the empowered child”, and close analysis of the centre’s Learning Stories led to the conclusion that all stories were about relating in one or more of these three domains. The teachers linked “knowing” and “relating to” very closely (knowing self, others, and place, are explained in Appendix 3). Andrea coined the term “bomb” stories for stories that include strengths in each domain. Andrea writes about “Welcoming”, the first story recorded in Table 6:

To me this story encompasses everything we want for every child here. It’s the dream. It takes us back to what we said in the beginning about children being able to leave the centre knowing who they are and being confident. We know she’s going to leave here with what it takes. I just know that Kailey is going to make it. (Andrea)

The three domains of “relating” might be seen to parallel the three key competencies of managing self (relating to self), relating to others (relating to others), and participating and contributing (relating to place).

| Welcoming

This is a “bomb” story. This is so because it shows Kailey being responsible and taking an interest in what is going on. This also shows she knew what was acceptable to do here and what was expected, i.e., the protocol of welcoming. She knew what to do in this situation and knew it was OK to take the lead, and that her contribution would be valued. Not only this, Kailey knew she was capable of meeting the needs of the others in this situation. This story was written by Jane (teacher) and though at first this story was a snippet of the girl’s first day it actually turned into a story for Kailey: Kailey took each girl by the hand to the family corner, “ This is where we play dolls.” It was as if Kailey recognised that dolls could be a thing the new girls might be interested in – that playing with the dolls was something that might help settle them, so this was the first thing she took them to. Kailey knew enough about other children to know what works, maybe drawing on her own experience. |

Where the Wild Things Are

This is a group story about knowing this place. This is about taking us to our roots, the whakapapa of the community. The children may have experienced some of this before because this is an exploration of our local wider community. The children were able to make links here to Tane, Mahuta and Papatunuku and knew how to respond to the environment around them. The older children role modelled care toward the environment to the younger children, transferring skills from one environment, the centre, to another, the reserve. The children showed us they had a sense of belonging to this place through their actions and responses to what they saw and talked about with us. They knew what was OK to do, and what wasn’t, and showed us they could really relate to this environment. We hope they will remember and retell this experience in the other settings they are involved in. |

| Happy Now

This is a story of knowing self, others and this place. Libby showed interest in someone else’s feelings and with the support of an adult (Katie) was able to empathise. She was able to recognise her own feelings and emotions, and relate them to how someone else was feeling, and she knew that it was OK to take on the support role for her friend. She also knew that timing is everything. She read the situation well and knew Tyler might not be ready to play just yet, but maybe later he might feel ready. This is also a story about liking yourself and knowing you have made a valued contribution, and being able to express this. |

Thanks for Your Help—Chaye-Tia

This is a story about knowing self and knowing this place. It’s about Chaye-Tia knowing which roles she can take on, and that she can assume that this will be OK. She did not hesitate to ask if she could join in; she had the confidence to ask to be included, and knew that her contribution would be valued. She was fully undertaking the job here and she knew she would really get to do this. It would not be a token input, rather, she would have an equal role in the job at hand. The fact that she was free to sign her name on the “outside sheet,” just as Gaynor the teacher had, shows this. Chaye-Tia could list what needed to be written down and this information was treated as reliable. She was really confident about her knowledge. |

| Great Mates

This is a knowing others, knowing self story for both Cory and Tyler. For Tyler it was knowing in himself that he had the ability to transfer his skills from one relationship to the next one. He knew, as Dylan’s younger brother, that Cory was likely to need more guidance and support in this new friendship. Previously, in Tyler’s relationship with Dylan, he had been the follower and Dylan the leader; now Tyler took the leader’s role. He knew that that was what was required of him. … For Cory this story was about knowing that he could step into his brother’s shoes. He could see Tyler was offering him a friendship and he was going to take it. He has seen his brother as a friend of Tyler and knows he can step up to be a friend too. Cory hasn’t had an established friendship before. He has two older brothers and he was always in their shadow when they were at the centre. Cory seemed to know he could trust Tyler, and that this friendship was a safe thing to get involved in. Tyler would respect and understand him. Cory knew that Tyler understood what he needed, that he knew him well. There was a familiarity that was present here, and it came through family connection or history; without this familiarity this friendship may not have developed in this way with such ease. |

Hanging Out

This is a knowing self and knowing place story. Anaru was away from an adult with the older children in the sandpit. He knew that these children would take care of him while Katie, a teacher, looked on. He had the freedom to explore at his own pace and he wasn’t directed by anyone. This was one of the first times Anaru had been “on his own” in the sandpit with the older children, with no other babies present. He felt safe to explore fully the properties of the sand. He trusted this situation on every level. |

Through the analysis and later discussions with the wider project team, the researchers at Aratupu came to realise that the learning of children around knowing self, knowing others, and knowing this place related closely to the teachers’ pedagogy. There are a number of specific strategies used by the teachers at Aratupu to encourage learning for children around these ways of knowing, and children are in effect immersed in these strategies. This is the topic of the next section, on the second research question.

Summary and implications

This research was an example of “telescoping” into learning episodes (Halverson, 2005 p. 21), and “telescoping out” to develop and illuminate a conceptual framework, designed to make sense of key competencies and learning dispositions in a way that would be helpful to teachers. It is usually teacher researchers who can most effectively “telescope in” (because they know the children and the context well), and it is the wider research team that can often most effectively “telescope out” to a wider perspective. It is the shift from one level of focus and back to the other that was necessary for analysing the picture.