1. Introduction

This study represents a systematic replication of a previous intervention which took place in schools in Mangere from 2003 to 2005. (McNaughton, MacDonald, Maituanai-Toloa, Lai, & Farry, 2006). The contexts and theoretical rationale are the same for the present study as those for the original Mangere study. We have repeated that historical and social context and theoretical framework here. In this first section, however, we briefly summarise the original study and also outline the form and the role of replication in the science represented here.

Replication

Our previous study

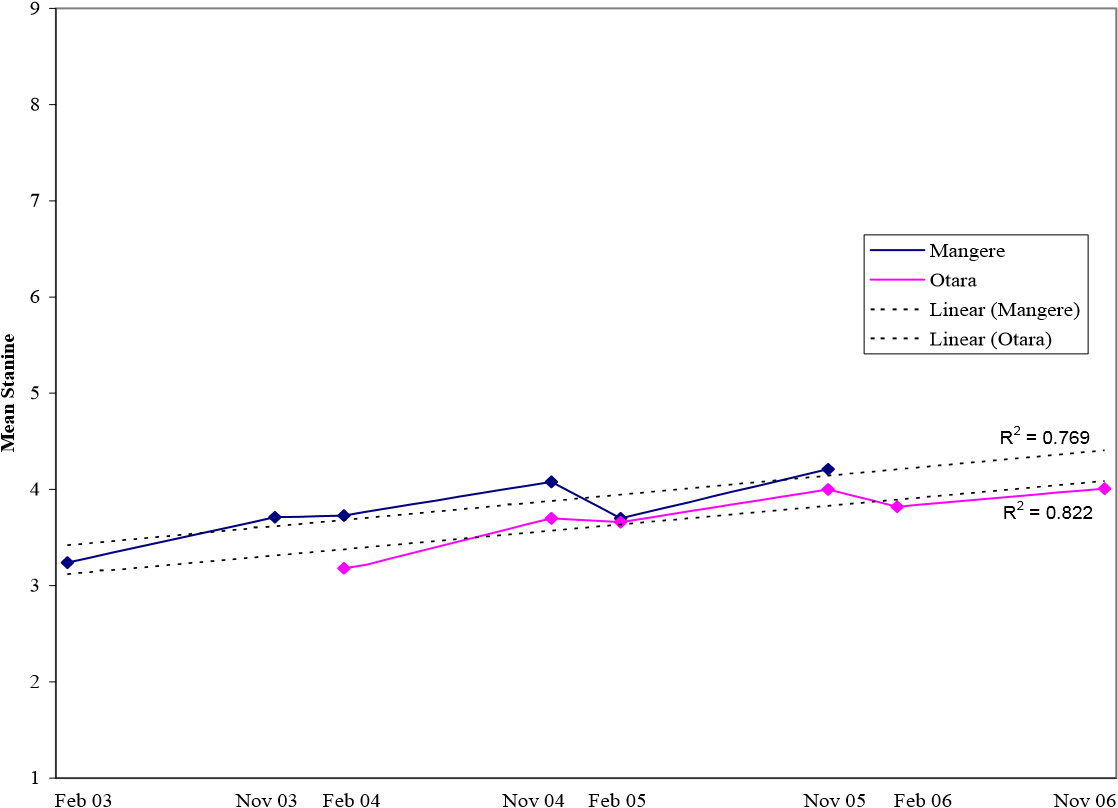

In previous quasiexperimental research with a cluster of similar schools in Mangere in South Auckland we have shown that it is possible to teach reading comprehension more effectively and raise achievement levels significantly higher than existing levels, in that study by 0.97 stanine[1] over three years with an overall effect size for gains in stanines of 0.62 (McNaughton et al., 2006). Given that stanine scores are age adjusted, the overall gain of 0.97 stanine indicates that the intervention advanced student achievement across all cohorts by almost a whole school year in addition to the expected national advancements made over three years. In addition, at each year level, achievement was raised significantly higher than the baseline forecast for that year level by up to 1.03 of a stanine.

Moreover, we showed that the intervention required a context-specific analysis of teaching and learning needs (Lai, McNaughton, MacDonald, & Farry, 2004; McNaughton, Lai, MacDonald, & Farry, 2004). That is, specific aspects of comprehension and competing hypotheses about the sources of low levels of comprehension needed to be checked. For example, it was found that accuracy of decoding was not a widespread impediment to comprehension (Lai et al., 2004). Knowing the profile of learning for children led to a planned research and development programme that catered for the specific needs of these particular children.

The evidence from the quasiexperimental design used with the first cluster of schools in Mangere was that an initial phase of cluster-wide and school-based analysis and critical discussion of evidence about teaching and learning was a major component of the intervention, initially contributing up to 0.5 of the shift in the average stanine, although this was in the context of a fixed sequence of phases. That is, when comparing two phases of professional development in sequence starting with critical analysis and then adding professional development focused on developing teachers’ instructional practice, the critical analysis phase was associated with marked acceleration in achievement (with continuing although smaller gains when the second phase of intervention targets was added), and that this phase on average produced greater accelerations in achievement than the second phase for the cluster (Lai et al., 2004).

The explanation for the effect of the first phase is that the evidence-based problem-solving process, which involved a professional learning community of teachers, researchers, and policymakers, enabled teachers to fine-tune their teaching practices in specific areas identified by the process. In other words, teachers became inquirers of their own practice, using evidence from student achievement and observations of current instruction to address the identified teaching and learning challenges to raise achievement. Indeed, evidence from classroom observations showed change occurred in the specific areas targeted through the problem-solving process (McNaughton et al., 2006).

This problem-solving approach to professional development has been implicated in other local and international interventions designed to raise student achievement (e.g., Alton-Lee, 2003; Thomas & Tagg, 2005; Timperley, Phillips, & Wiseman, 2003). For example, Timperley et al. (2003) found that schools that engaged more strongly in problem solving around student data had higher student achievement in literacy than schools that did not. This approach has also been proposed as a more effective form of professional development. In their literature review on effective professional development, Hawley and Valli (1999) identified evidence-based problemsolving as an effective form of professional development, perhaps more effective than traditional workshop models. This was confirmed by a recent synthesis which claimed that analysis of data is effective professional development that can be linked to enhanced student learning (Mitchell & Cubey, 2003).

In addition, the success of the intervention appeared to be related to the development and maintenance of professional learning communities, and we found some evidence, especially in a second year, that school-level effects such as leadership and the presence of ongoing participation became important determinants (Lai et al., 2006). This is consistent with research where instructional leadership and the development of professional learning communities as sites for discussing evidence about teaching and learning are implicated in the intervention’s success (e.g., Newman, Smith, Allensworth, & Bryk, 2001; Taylor, Pearson, Peterson, & Rodriguez, 2005). Coburn (2003) even suggests that sustainability of an intervention requires support from multiple levels of the system, including communities of teachers and school leaders discussing practice within and across schools. This is consistent with the results of the first (Mangere) intervention. The research–practice collaboration is part of the wider strategy for sustainability in local initiatives, where schools form strategic partnerships, in this case with research institutions, to create sustainable area-wide interventions to raise student achievement.

In the second year a professional development programme, focused on specific aspects of the teaching of reading comprehension, was added to continued problem solving by the communities. Unlike some other interventions, the specific practices were highly contextualised, developed directly from the profiles of teaching and learning identified in the first phase. Observations conducted in classrooms in the second phase showed that targeted aspects of instruction, such as increasing the focus on vocabulary teaching, instruction aimed at increasing paragraph-level comprehension, and developing students’ awareness of tasks and strategies were taking place. The overall gain in the second phase was 0.35 stanine.

The explanation for gains in the second phase was that professional development aimed at identifying and fine-tuning specific practices was needed in addition to the processes implemented in the first phase. Despite the substantial gains in the first phase (0.47 stanine), they were not sufficient to achieve the goal which the school communities had set of parity with national distributions. Moreover, there were cohorts which made the same or even higher gains in the second phase and were only then approaching national levels in their classrooms. Despite greater variability in the second phase, and lower overall gains, it did not appear that the professional development focused on specific instructional practices was of lesser significance per se. One interpretation of the results was that gains following or in addition to analysis are harder to achieve.

Phase Three continued the critical discussion of Phase One and the teaching targeted in Phase Two. Further professional development did not occur, but further components designed to build the critical discussion around evidence through the professional learning communities within and across schools were added. The indicators for these attributes in the third phase included the continued involvement of schools in the process of critical discussion and the designing, implementing, and collectively reporting of classroom-based projects in a teacher-led conference. In general, there was a high rate of engagement by teachers as well as leaders in the conference. The topics for projects were theoretically based, the teachers gathered and reported on evidence, they adopted an analytic stance to that evidence and they related their analyses to the patterns of student learning and teaching in their classrooms. The evidence from the achievement data was that the intervention was sustained in the third year. The rate of gain increased in the third phase (0.51 stanine) compared with the second.

Good science requires replications

In quasiexperimental research the need to systematically replicate effects and processes is heightened because of the reduced experimental control within the design. This need is specifically identified in discussion about alternatives to experimental randomised designs (Borko, 2004; Chatterji, 2005; Raudenbusch, 2005). For example, McCall and Green (2004) argue that in applied developmental contexts, evaluation of programme effects requires a variety of designs including quasiexperimental, but our knowledge is dependent on systematic replication across site analyses. Replication across sites can add to our evaluation of programme effects, particularly when it is inappropriate or premature to conduct experimental randomised designs. Such systematic replication is also needed to determine issues of sustainability (Coburn, 2003). Coburn argues that the distribution and adoption of an innovation are only significant if its use can be sustained in original and subsequent schools.

There is debate within New Zealand about how influential school-based interventions focused on teaching practices can be in raising achievement (Nash & Prochnow, 2004; Tunmer, Chapman, & Prochnow, 2004). Given the significance of these counter-arguments to policy directions, it is important to add to the evidence of teacher effectiveness (Alton-Lee, 2003). Therefore, whilst results from the collaboration with the Mangere cluster of schools suggested the significance of the three-phase intervention, with statistically significant improvements in student achievement across all year levels and schools (McNaughton et al., 2004), it is important that these results be replicated to provide further evidence of the impact of the intervention.

In the research with the Mangere cluster of schools, there were inbuilt replications across age levels and across the cluster of schools within the quasiexperimental design format (McNaughton et al., 2004). However, there are possible competing explanations for the conclusions of the cluster-wide results which are difficult to counter with the quasiexperimental design. One is that the immediate historical, cultural, and social context for these schools and this particular cluster meant that an unknown combination of factors unique to this cluster and these schools determined the outcomes. For example, it might be that the nature of students changed in ways that were not captured by the general descriptions of families and students. Or, given that the immediate history included a number of initiatives such as ECPL (Early Childhood Primary Links) and AUSAD (Analysis and Use of Student Achievement Data) (Annan, 1999), the schools were developing more effective ways of teaching anyway.

In this report we describe a systematic replication in a second cluster of schools, in Otara, in South Auckland. The Otara cluster of schools shared significant similarities with the Mangere cluster in terms of geographical location and school and student characteristics. A similar number of schools were involved, they were from neighbouring suburbs, and they had similar proportions of ethnic groups and a similar history of interventions, in that both clusters had been involved in similar government schooling-improvement initiatives in the years leading up to the research. The research–practice collaboration, as was the case in the original research intervention, involved a three-phase research and development sequence designed to improve the teaching of reading comprehension in the middle school years to raise student achievement. The collaboration involved researchers working with teachers and school leaders of urban schools with the lowest employment and income levels in New Zealand, serving largely Māori and Pacific communities. The replicated process was collaborative, staged, analytic, theoretically intense, and culturally located (see McNaughton et al., 2004, for details).

Yesterday was too late?

In 1981, Peter Ramsay (Ramsey, Sneddon, Grenfell, & Ford, 1981) and his colleagues at the University of Waikato completed a study of the schools in South Auckland. The title of their report was Tomorrow may be too late. They argued that there was an impending crisis created by “educational disadvantage suffered by most school-aged students in Mangere and Otara” who were “achieving well below their chronological age” (p. 41). They concluded with “a plea for urgency as the needs of the children of Mangere and Otara are very pressing. Tomorrow may be too late!” (p. v).

The gap in achievement between Māori and non-Māori children in mainstream schools is not a recent phenomenon. Earlier reports, such as the Currie (1962) and Hunn (1961) reports on education in the 1950s, had identified this difference as important and as urgently in need of a solution (see also Openshaw, Lee, & Lee, 1993). The long-standing issue on the “problem” for Māori students is important to note, because some commentaries suggest it is relatively recent and can be linked to changes in methods of teaching reading and writing which began in the 1960s (Awatere-Huata, 2002; Nicholson, 2000).

Yet the historical picture is not entirely bleak. There is evidence that in the colonial period, there were times when Māori children outperformed other children in some schools. Some evidence for this can be found in the Survey of Native Schools for 1930 (Education Gazette, 1930; see also McNaughton, 2000).

The sense of crisis that Ramsay expressed for the sake of children, communities, and families is also present in reports from other countries (Snow, Burns, & Griffen, 1998). The need is identified for communities who have, relative to the mainstream communities, less economic and political power, whose children are considered to be “minorities”. But there has been little evidence that the crisis is able to be solved in schools. In the United States, Borman (2005) shows that national reforms to boost the achievement of children in low-performing schools serving the poorest communities have produced small gains in the short term (of the order of effect sizes of less than 0.20), but that after seven years, in those few schools that sustain reforms over a long period, the effects increase (estimated to be around effect sizes of 0.50). When considered across the country, while some achievement gains have occurred, they have typically been low and need to be accumulated over long periods of time.

At a more specific level, some studies from the United States have shown that clusters of schools serving “minority” children have been able to make a substantial difference to the achievement of children. In one set of studies (Taylor, Pearson, Peterson, & Rodriguez, 2005), researchers who intervened in high-poverty schools with carefully designed professional development research and development found small cumulative gains across two years too. This study and others pointed to important school-level factors that must be in place in order for all children to achieve at high levels in reading. Summarising these, Taylor et al. (2005) noted six key elements: improved student learning, strong leadership building, strong staff collaboration, ongoing professional development, sharing student assessment data, and reaching out to parents. In these studies there is evidence that achievement can be effected, and in the case of studies such as Taylor et al. (2005), that small gains over two years could be attributed to these characteristics.

The days after Ramsay’s tomorrow

Where does such offshore evidence leave the schools of South Auckland, which, according to Ramsay, had already received substantial additional resources by the early 1980s? There is little evidence that Ramsay’s concern led to immediate changes. The evidence from both national and international comparisons suggests that by the beginning of the 1990s, the children in decile 1 schools, and more generally children who were Māori and Pasifika, were still not achieving as well as non-Māori and non-Pasifika children in reading comprehension. The reading comprehension comparisons across 32 countries in the International Association for Evaluation of Educational Achievement study (IEA, 1992) provided stark evidence of what came to be called a “long tail” in the distribution of achievement. The problem was that while in general New Zealand continued to have high average achievement, and the best students in New Zealand were superior to other students in the world, Māori and Pasifika children were over-represented in the “long tail” (Elley, 1992; Wagemaker, 1992).

In New Zealand the recognition of the distribution problem, as well as other research developments, has had an effect. Reports by a Literacy Task Force (1999) and a Literacy Experts Group (1999) contributed to a national policy shift, which was implemented in the National Literacy and Numeracy strategy. The policy shift promoted concerted professional development and research practice development which was focused on Years 1–4 and Māori and Pasifika children, especially those in decile 1 schools.

Associated with this policy and practice shift, there is now evidence from the national educational monitoring project (NEMP) and renorming exercises that changes in the targeted areas have occurred (Elley, 2005). The news is positive for the early stages of literacy instruction. From NEMP, the one area in literacy achievement where there are clear changes is in reading decoding, both accuracy and fluency (Flockton & Crooks, 2001). Their second cycle of assessments of reading showed that the percentages of children reading below age level in reading accuracy at Year 4 had reduced markedly from 1996 to 2000, from around 20 percent to around 13 percent. Little improvement occurred for Year 8 children in oral reading (Flockton & Crooks, 2001). A recent renorming of standardised assessments at Year 1 (6 years) conducted in 2000 also suggests that knowledge of letters and sounds has improved (Clay, 2002).

These increases in oral reading accuracy were found to have been maintained in the third (2004) cycle of assessments at Year 4. Further notable increases in accuracy were found for the Year 8 children, with only around 11 percent at both year levels now reading below age level (Crooks & Flockton, 2005). The breakdown of gains in 2000 and 2004 suggest that reading accuracy had improved at similar rates at Year 4 for both Māori and Päkehä children (Flockton, 2003). But by 2004, the analyses showed substantial reduction at Year 4 in the gap between Päkehä and Māori students (see further comment at nemp.otago.ac.nz/forum_comment/ 2004).

Research-based interventions using experimental designs have shown that the gaps at this early stage can be reduced considerably. We also know many of the characteristics of effective teaching at that early stage. For example, in the Picking up the Pace research with Māori and Pasifika children in decile 1 schools in Mangere and Otara, their typical achievement was two stanines below average levels in areas of decoding after a year at school (Phillips, McNaughton, & MacDonald, 2004). A research-based intervention used professional development with teachers and teacher leaders to increase effectiveness in areas of reading and writing, including specific phonics instruction. Where teaching approaches were fine-tuned to solve children’s confusions and to make the purpose of classroom activities more obvious, and higher expectations about achievement were developed through evidence-based analyses of progress, the children’s achievement was raised to close to the national distribution (see Phillips et al., 2004). In some areas, such as alphabet knowledge, their progress was as good as or better than typical progress; in others, for example, progress through text levels, they closely approximated typical progress; but in one area, generalised word recognition, they were still noticeably below average levels.

“Tomorrow” is still the same for reading comprehension

These indicators of progress are cause for some celebration, given the urgency signalled in Ramsay’s report, and the seemingly intractable nature of the teaching difficulty over decades. But the news has not all been good. For reading comprehension, little appeared to have changed for Māori and Pasifika children in low-decile schools over the period in which the decoding changes occurred, as we will show below. The NEMP data indicate increases in levels of comprehension in Year 4 from 1996–2000, but the breakdown of the achievement patterns suggests a substantially wider disparity between Māori and non-Māori in comprehension both at Year 4 and at Year 8. Furthermore, for children in low-decile schools, gaps in comprehension increased both at Year 4 and at Year 8 (Flockton, 2003).

In 2004 the gains in oral-reading accuracy which were maintained in the third cycle of assessments were not, however, matched by similar gains in reading comprehension for the total group of students at either Year 4 or Year 8. The detailed comparisons suggest that the gaps in oral reading accuracy between Māori and Pasifika students and Päkehä students which had closed between 1996 and 2000 reduced further in 2006. But this was not matched in comprehension (Crooks & Flockton, 2005). Commentaries on this 2004 report note that Māori children performed well in decoding, but there were large differences in favour of Päkehä in aspects of comprehension (NEMP, 2004). These differences were apparent for Pasifika children too, and they were apparent for decile 1–3 schools when compared with other decile groups (Crooks & Flockton, 2005).

This is true also of at least some of the schools in South Auckland. When we completed a baseline profile of a cluster of schools in Mangere (as described earlier in the introduction), we found that across schools and year levels, achievement in reading comprehension was relatively flat at around stanine 3, and something like two years below what would be expected as average progress nationally (Lai et al., 2004). This was also found in a baseline profile for the present similar cluster of schools in Otara as described further in this report. They too were, on average, around stanine 3 across year levels and across schools (see Lai et al., 2006 for full details).

What we now know is that even if we achieve a dramatic change in teaching early reading, it does not necessarily mean that the gap reduces further on up the system. Experimental demonstrations specifically targeting the teaching of phonics also tend to show very limited transfer to comprehension (Paris, 2005). Recent national data from the Assessment Tools for Teaching and Learning (AsTTle) project across multiple dimensions of reading comprehension confirm the NEMP picture of large differences between Māori and Pasifika children and other children which are stable across decile levels, despite significant trends of higher achievement from lower to higher decile-level schools (Hattie, 2002).

These comparisons need to be treated with an important qualification. The broad description of these disparities can mask important aspects of the literacy development and achievement of children in so-called “minority” groups. The conventional indicators of school literacy represent some of what children learn about literacy. But children who are in communities which have low employment, low incomes, and minority cultural and language status have engaged in a range of literacy and language activities, some of which might be quite different from mainstream children. Their knowledge, therefore, may not be well represented in tests of conventional literacy practices, especially at the beginning of schooling (McNaughton, 1999; Snow et al., 1998) and as they move into the middle school levels.

Here, it is important to note that there is an urgent challenge which has strategic importance to all of New Zealand. Students now need greater ranges and levels of knowledge and skills for postsecondary school study and for employment than ever before. Education is increasingly important to the success of both individuals and nations (Darling-Hammond & Bransford, 2005). Overrepresentation of particular groups in low achievement bands is not acceptable at individual, community, or national levels, no matter what the proportion of the population. It is a pressing matter of cultural, political, constitutional (Treaty of Waitangi), ethical, economic, and educational significance that we develop more effective forms of instruction for these students. It is worth noting that by 2021, Māori children will comprise 28 percent and Pasifika children 11 percent of all the under-15-year-olds in New Zealand (Statistics New Zealand, 2002). In Mangere and Otara schools, children from these communities already make up over 90 percent of many school rolls.

There is an additional dimension to that challenge. Many of the children in the South Auckland schools have a language other than English as their home language. Yet language development for these children is not well understood. In the context of bilingual instruction, for example, and the relationships between development in two languages and two systems of literacy, little is known about biliteracy development and relationships with literacy and literacy instruction (Sweet & Snow, 2003).

Twenty-five years after the Ramsay report, we can report in this study important gains in reading comprehension in Year 4–8 students in decile 1 schools in Otara. This report describes the science of these changes and documents the research and development programme that had taken place. However, the science is closely bound up with a policy context of associated changes in practices. It is likely that without the policy context, the science involved in developing more effective instruction would have achieved less. The results reported here need to be considered with this policy context in mind (Annan & Robinson, 2005).

In addition, the research is located in a particular historical context of school-based interventions. One is the landmark study Picking up the Pace (Phillips, McNaughton, & MacDonald, 2001). As noted above, this focused on instruction in the first year, and set out to examine the separate and combined effects on children’s achievement of providing co-ordinated professional development to teachers in early childhood settings, and to teachers of children in their first year of schooling. Since the success of that project, which was completed in 2001, further professional development for Year 1 teachers has occurred, based on the practices identified in the research, and the programme in some schools has been extended through to Year 3.

That study and its further development were part of a much broader project initiative, Strengthening Education in Mangere and Otara (SEMO), which aimed to raise the achievement levels of children in these two areas. SEMO’s general aim was to strengthen schools in the area and to enhance children’s learning opportunities, particularly in literacy, by enhancing the work of early childhood and primary teachers who were providing literacy programmes. SEMO was succeeded by a further policy and practice development in Mangere and Otara, Analysis and Use of Student Achievement Data (AUSAD). This project is located within that government-funded school improvement initiative. The goal of AUSAD is to offer high-quality learning environments to raise achievement. This is done by using student achievement information to inquire into the nature of the underachievement, to test competing explanations of its cause, and to monitor the impact of teachers’ decisions about how to intervene. In short, the focus is on developing the inquiry skills of teachers to improve school practices and student learning outcomes. The initiative comprises a number of interventions focusing on improving literacy and numeracy achievement (e.g., the Third Chance programme aimed at improving literacy in Years 1–3).

Reading comprehension

Recent commentaries identify a major theoretical challenge facing literacy instruction. Now that some of the pressing issues in beginning reading instruction (but by no means all) have been resolved, the challenge concerns the teaching of reading comprehension. Higher levels of reading comprehension and related areas of critical thinking are central to the purposes of contemporary schooling, and are part of the education priorities and key competencies that have been set for New Zealand education (Ministry of Education, 2005). But there is a critical need for research into instruction that enhances comprehension, and into interventions that enable schools to teach comprehension effectively. The most recent reviews of relationships between research and practice note that overall evidence of teacher effectiveness is limited, and that research has not impacted greatly on effective comprehension instruction (see Block & Pressley, 2002). Similarly, the RAND (Research and Development) reading study group, which was set up in 1999 by the US Department of Education’s Office of Educational Research and Improvement to identify the most pressing needs for research in teaching reading, has concluded:

We have made enormous progress over the last 25 years in understanding how to teach aspects of reading. We know about the role of phonological awareness in cracking the alphabetic code, the value of explicit instruction in sound–letter relationships, and the importance of reading practice in producing fluency.… The fruits of that progress will be lost unless we also attend to issues of comprehension. Comprehension is, after all, the point of reading. (Sweet & Snow, 2003, p. xii)

The challenges to teaching effectively have been identified (Pressley, 2002; Sweet & Snow, 2003). One is the need to build on the gains made in research about instructional practices for beginning literacy. A second is to do with knowledge transfer, a failure to turn all that we know about comprehension and comprehension instruction into generally more effective teaching. These needs are particularly significant for schools serving culturally and linguistically diverse populations in low-income areas (Garcia, 2003).

As noted above, on average, students in the middle years of school in New Zealand have high levels of reading comprehension, judged by international comparisons; however, there are large disparities within the distribution of achievement. These are between children from both Māori and Pasifika communities in urban schools with the lowest employment and income levels, and other children (Alton-Lee, 2004). These findings highlight the need for instructional approaches that enable teachers to develop, use, and sustain effective teaching of reading comprehension with culturally and linguistically diverse students. For Pressley (2002), this challenge represents an application problem.

We know a lot about what students need to be able to do, which includes such things as regulating strategy use, and we know a lot about specific instructional effects, such as the need for explicit strategy instruction. What he claims we have failed to do is translate that knowledge into widespread usage with known effects. While Sweet and Snow (2003) echo this claim in their RAND summary of reading comprehension instruction, they also argue that there is yet more to be known about specific teaching and learning relationships, especially in the context of diverse readers, diverse text types, and diverse instructional contexts.

Generally, there is considerable consensus around what students need to learn, and what effective teaching looks like. In order to comprehend written text, a reader needs to be able to decode accurately and fluently, and to have a wide and appropriate vocabulary, as well as appropriate and expanding topic and world knowledge, active comprehension strategies, and active monitoring and fix-up strategies (Block & Pressley, 2002; Pressley, 2002). So it follows that children who are making relatively low progress may have difficulties in one or more of these areas. The consensus around teaching effectively identifies attributes of both content (curriculum) and process (Taylor et al., 2005). For the middle grades, these include instructional processes in which goals are made clear, and which involve both coaching and inquiry styles that engage students in higher level thinking skills. Effective instruction also provides direct and explicit instruction for skills and strategies for comprehension. Effective teaching actively engages students in a great deal of actual reading and writing, and instructs in ways which enable expertise to be generalisable and through which students come to be able to self-regulate independently.

In addition, researchers have also identified the teacher’s role in building students’ sense of selfefficacy and, more generally, motivation (Guthrie & Wigfield, 2000). Quantitative and qualitative aspects of teaching convey expectations about students’ ability which affect their levels of engagement and sense of being in control. These include such things as text selection. Culturally and linguistically diverse students seem to be especially likely to encounter teaching which conveys low expectations (Dyson, 1999). There are a number of studies in schooling improvement which have shown how these can be changed. In general, changes to beliefs about students and more evidence-based decisions about instruction are both implicated, often in the context of school-wide or even cluster-wide initiatives (Bishop, 2004; Phillips et al., 2004; Taylor et al., 2005).

Just as with the components of reading comprehension, it follows that low progress could be associated with teaching needs in one or more of these areas. Out of this array of teaching and learning needs, those for students and teachers in any particular instructional context will have a context-specific profile. While our research-based knowledge shows that there are wellestablished relationships, the patterns of these relationships in specific contexts may vary. A simple example might be whether the groups of students who make relatively low progress in a particular context, such as a cluster of similar schools serving similar communities, have difficulties associated with decoding, or with use of strategies, or both, and how the teaching that occurs in those schools is related to those difficulties.

Several hypotheses are possible for the low levels of reading comprehension which are tested in the following research. One is that children’s comprehension levels are low because of low levels of accurate and fluent decoding (Tan & Nicholson, 1997). A second is that children may have learned a limited set of strategies; for example, they may be able to recall well, but are weaker in more complex strategies for drawing inferences, synthesising and evaluation; or they may not have been taught well enough to control and regulate the use of strategies (Pressley, 2002). Other possible contributing reasons might be more to do with language: that is, children’s vocabulary may be insufficient for the texts used in classroom tasks (Biemiller, 1999); or they may be less familiar with text genres. Well-known patterns of “Matthew effects” may be present in classrooms, where culturally and linguistically diverse children receive more fragmented instruction focused on decoding or relatively simple forms of comprehending, or receive relatively less dense instruction, all of which compounds low progress (McNaughton, 2002; Stanovich, West, Cunningham, Cipielewski, & Siddiqui, 1996). There is also a set of possible hypotheses around whether the texts, instructional activities, and the pedagogy of the classroom enable cultural and linguistic expertise to be incorporated into and built on in classrooms (Lee, 2000; McNaughton, 2002). But each of these needs to be checked against the patterns of instruction in the classrooms in order for the relationships to be tested.

This approach focuses on the need to understand specific profiles. Rather than test in an ad hoc way the significance of certain teaching and learning relationships, what we did in the study was to test a package of targeted relationships. These are relationships initially identified through a process of profiling both learning needs and patterns of existing instruction. The analysis is aimed at adding further to our research-based knowledge of relationships between teaching and learning in specific contexts, and thereby contributing to the research and application challenges signalled by Pressley (2002) and Sweet and Snow (2003).

We assume in this profiling that while much is known, there are still some areas where we need more knowledge and analysis. This need is pressing in the context of cultural and linguistic diversity. An example in our contexts is the role of activation and deployment of background knowledge. A theoretical argument is often made that instruction needs to incorporate more of the cultural and linguistic resources that minority children bring to classrooms (McNaughton, 2002). But complementing this is another argument: that students need to develop more awareness of the requirements of classroom activities, including the relationships between current resources and classroom activities (McNaughton, 2002). While the general hypothesis of the significance of background knowledge is well demonstrated in controlled studies of reading comprehension (Pressley, 2002), the particular idea of teachers being able to incorporate this, and balancing it with enhancing awareness of classroom requirements, has not been well tested.

In the following study we draw on known properties of effective comprehension and on known relationships between types of instruction and learning outcomes. But we apply this knowledge in an intervention context. Within that context, we test the significance of the assumed relationships and features of teaching and learning. Because the context includes substantial numbers of children for whom English is a second language and who come from diverse cultural backgrounds, this is also a context for discovering new learning needs and new relationships between teaching and learning.

Professional learning communities and critical analysis of evidence

A previous study, focused on literacy achievement over the transition to school, demonstrated substantial gains across a cluster of 12 decile 1 urban schools with primarily Māori and Pasifika students (Phillips et al., 2001). Among other things, the programme involved intensive collection and analysis of achievement data within schools and across a group of schools. Instructional approaches were modified to impact more strongly on increasing student engagement and teaching effectiveness around agreed goals. Team leaders within schools led professional communities. While the initial development took place within schools over six months, the programme has now been in place in schools for several years. Follow-up research has indicated that those schools which maintained and built on these processes, through a professional learning community focused on teaching and learning, have increased student achievement over time (Timperley et al., 2003).

The features of these learning communities appear similar to those described by Newman et al. (2001). They identify high “instructional programme coherence”, a necessary condition for improvements in student achievement that are more likely to be sustained over time. These authors define high instruction coherence as “a set of interrelated programmes for students and staff that are guided by a common framework for curriculum, instruction, assessment, and learning climate and that are pursued over a sustained period” (p. 229). The elements suggested which are crucial to high instructional programme coherence can be identified in the Phillips et al. (2004) programme. They include a common instructional framework for teaching literacy across all schools involved in the programme; teachers working together to implement the common programme over a sustained period of time; and assessments which are common across time. Both the New Zealand programme and the high-programme-coherence schools in the USA rely on long-term partnerships between schools and external support organisations; the development of a common framework for literacy diagnosis which every teacher has to implement; expected collaboration between teachers; joint decision-making around assessments to use; and similar factors.

Underlying many of the features of schools with high programme coherence is the use of evidence to guide and evaluate teaching practices. For example, the aim of AUSAD was for practitioners to use student achievement data to inform practice. This has led directly to planning how to design classroom programmes that specifically meet the needs of students in these diverse urban schools. The research-schools partnership in this present study has responded to the increasing calls for greater understanding of the teaching and learning of comprehension to inform practice in New Zealand (e.g., Literacy Task Force, 1999; Learning Media, 2003) and internationally (Pressley, 2002).

Similarly, critical analysis of student data is identified as significant in school and teaching effectiveness research (e.g., Hawley & Valli, 1999; Robinson & Lai, 2006). In their literature review on effective professional development, Hawley and Valli (1999) identify critical analysis as a more effective form of professional development than traditional workshop models. The collection, analysis, and discussion of evidence were present in the schools maintaining gains in the Phillips et al. (2004) programme (Timperley et al., 2003).

A general question that arises is how much the critical analysis process contributes to the student changes in successful programmes. In the research and development programme reported here, the question concerns its contribution to the development of more effective teaching of reading comprehension in schools serving culturally and linguistically diverse students in low-income communities. The collection, analysis, and discussion process took place in the context of collective analytic and problem-solving skills, where teachers collaborated with researchers and professional developers to co-construct the professional development. It is important to note here our assumption that professional expertise was distributed within and across schools, and that teachers would be able to contribute as coparticipants in a research-based collaboration (McNaughton, 2002). The issue of how teachers are viewed is particularly salient in the New Zealand context, as recent research syntheses show that school effects are consistently smaller than teacher or class-level effects. These latter effects can account for up to 60 percent of the variance in student achievement, depending on the subject areas, level of schooling, and outcome of interest, as estimated by Alton-Lee (2004).

This sort of collective problem solving represents one way of balancing two tensions identified in effective educational interventions (Coburn, 2003; Newman et al., 2001). One tension is around the issue of guaranteeing fidelity by adhering to a set of instructional procedures used in wellresearched interventions, versus developing procedures which are derived from context-specific problem solving, but may have a less-well-known research-intervention base. A related tension is between importing a set of procedures, in a way which risks undermining local autonomy and efficacy, and a more collaborative development of common procedures, which risks losing instructional coherence. It seems to us that it is possible to construct fidelity to a common programme which has been strongly contextualised by developing a highly focused collaborative context. There is research evidence that suggests approaches in which professional development focuses on joint problem solving around agreed evidence, such as student achievement outcomes, is more likely than predetermined programmes to result in sustainable improvements in student achievement, particularly in reading comprehension (Coburn, 2003; Hawley & Valli, 1999; Timperley et al., 2003).

Evidence is critical to the processes of developing a professional learning community capable of solving the instructional problems associated with more effective teaching. Systematic assessment for formative and diagnostic purposes is essential in order to avoid the problems we have found before, where educators assume that children need a particular programme or approach, but close inspection of the children’s profiles shows that they already have the skills targeted in those approaches (McNaughton, Phillips, & MacDonald, 2003). The significance of collecting and analysing data, rather than making assumptions about what children need (and what instruction should look like), was recently underscored by Buly and Valencia (2002). Policymakers in the State of Washington had mandated programmes without actually analysing profiles of lowprogress students, identified by test scores from fourth grade National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) scores. The assumption underlying policies and interventions was that poor performance reflected students’ difficulties with more basic decoding abilities. Yet there was little data about this assumption, and little evidence to show that focusing on such skills would improve comprehension at fourth grade.

Using a broad band of measures, Buly and Valencia identified five groups of low-progress readers, some of whom did indeed have limited fluency and accuracy in decoding. However, mandating phonics instruction for all students who fell below the proficiency levels had missed the needs of the majority of students, whose decoding was strong, but who struggled with comprehension or language requirements for the tests. This finding highlights the need for research-based applications of best practice, based on analyses of student needs. One particular need that has been identified in other countries is for more effective teaching of reading comprehension than has typically been the case (Sweet & Snow, 2003).

The issue of sustainability

Developmental sustainability

A major challenge has been created by the advances made in schooling improvement and increasing instructional effectiveness through professional development. This is the issue of sustainability (Coburn, 2003). For the following research and development programme, sustainability has two meanings. The immediate concern facing the schools in South Auckland has been the need to build further progress in literacy, adding to the more effective instruction in the early years. This inevitably means considering the quality of the teaching and learning of comprehension (Sweet & Snow, 2003).

The issue in the decile 1 schools is that the subsequent instructional conditions set channels for further development, and if the channels are constructed for relatively “low” gradients of progress, this creates a need for further intervention. Unfortunately, as we have already noted and describe further below, the available evidence shows that despite the gains in decoding, there were still wide and possibly increasing disparities in achievement on comprehension tasks for Māori and Pasifika children, particularly in low-decile schools (Flockton & Crooks, 2001; Hattie, 2002; Lai et al., 2004).

The reason for needing to deliberately build this sustainability resides in the developmental relationships between decoding and comprehension. Logically, there are relationships such as the one identified by Tan and Nicholson (1997), who showed that poor decoding was associated with poor comprehension. It makes perfect sense that if you can’t get the words off the page, you can’t comprehend. The problem is that the corollary doesn’t apply—decoding may be a necessary condition, but it is not a sufficient condition. So being a better decoder does not automatically make you a better comprehender.

The developmental reason for this can be found in Paris’s (2005) multiple-components model of literacy development, or Whitehurst and Lonnigan’s (2001) “inside outside” model of the strands of literacy development. Each of these explains that there are different developmental patterns associated with acquisition for components such as items, and for language meaning and uses, and they are somewhat independent. This accounts for the phenomenon of rapid, accurate decoders who are not able to comprehend, which is described by professional educators and researchers (McNaughton et al., 2004). There is another developmental reason. Inoculation models do not apply to most phenomena in teaching and learning; just because you know and can do some stuff this year doesn’t mean that you automatically make further gains next year. It depends at least in part on whether the teacher you meet effectively enables you to build on to and extend your learning. Fluent, accurate decoding is a necessary but not a sufficient condition for developing further comprehension skills (Block & Pressley, 2002; Sweet & Snow, 2003).

Sustainability of an effective professional learning community

There is a second meaning for sustainability. We now need to know which properties of teaching practices in schools enable success to be sustained with new cohorts of students and new groups of teachers joining schools (Timperley, 2003). Although effective practices may be able to be identified, this is an additional challenge. Sustaining high-quality intervention, it now seems, is dependent on the degree to which a professional learning community is able to develop (Coburn, 2003; Toole & Seashore, 2002). Such a community can effectively change teacher beliefs and practices (Annan, Lai, & Robinson, 2003; Hawley & Valli, 1999; Timperley & Robinson, 2001).

Several critical features of a collaboration between teachers and researchers are predicted to contribute to such a community developing (Coburn, 2003; Toole & Seashore, 2002; Robinson & Lai, 2006). One is the need for the community’s shared ideas, beliefs, and goals to be theoretically rich. This shared knowledge is about the target domain (in this case, comprehension); but it also entails detailed understanding of the nature of teaching and learning related to that domain (Coburn, 2003). Yet a further area of belief that has emerged as very significant in the achievement of linguistically and culturally diverse students in general, and indigenous and minority children in particular, is the expectations that teachers have about children and their learning (Bishop, 2004; Delpit, 2003; Timperley, 2003).

Being theoretically rich requires consideration not only of researchers’ theories, but also of practitioners’ theories, and of adjudication between them. Robinson & Lai (2006) provide a framework by which different theories can be negotiated, using four standards of theory evaluation. These standards are accuracy (empirical claims about practice are well founded in evidence); effectiveness (theories meet the goals and values of those who hold them); coherence (competing theories from outside perspectives are considered); and improvability (theories and solutions can be adapted to meet changing needs, or to incorporate new goals, values, and contextual constraints).

This means that a second feature of an effective learning community, already identified above, is that their goals and practices for an intervention are based on evidence. That evidence should draw on close descriptions of children’s learning as well as descriptions of patterns of teaching. Systematic data on both learning and teaching would need to be collected and analysed together. This assessment data would need to be broad based, in order to understand the children’s patterns of strengths and weaknesses, to provide a basis for informed decisions about teaching, and to clarify and test hypotheses about how to develop effective and sustainable practices (McNaughton et al., 2006). This means that the evidence needs to include information about instruction and teaching practices.

However, what is also crucial is the validity of the inferences drawn, or claims made, about that evidence (Robinson & Lai, 2006). The case reported in Buly & Valencia (2002), for example, shows how inappropriate inferences drawn from the data can result in interventions that are mismatched to students’ learning needs. Robinson & Lai (2006) suggest that all inferences be treated as competing theories and evaluated.

So a further required feature is an analytic attitude to the collection and use of evidence. One part of this is that a research framework needs to be designed to show whether and how planned interventions do in fact impact on teaching and learning, enabling the community to know how effective interventions are in meeting its goals. The research framework adopted by the community needs therefore to be staged so that the effect of interventions can be determined. The design part of this is by no means simple, especially when considered in the context of recent debates about what counts as appropriate research evidence (McCall & Green, 2004; McNaughton & MacDonald, 2004).

Another part of the analytic attitude is critical reflection on practice, rather than a comfortable collaboration in which ideas are simply shared (Annan et al., 2003; Ball & Cohen, 1999; Toole & Seashore, 2002). Recent New Zealand research indicates that collaborations which incorporate critical reflection have been linked to improved student achievement (Phillips et al., 2004; Timperley, 2003) and to changed teacher perceptions (Timperley & Robinson, 2001).

A final feature is that the researchers’ and teachers’ ideas and practices need to be culturally located. We mean by this that the ideas and practices that are developed and tested need to entail an understanding of children’s language and literacy practices, as these reflect children’s local and global cultural identities. Importantly, this means knowing how these practices relate (or do not relate) to classroom practices (New London Group, 1996).

The main research project

This project is a result of a three-year research and development partnership between schools in the Otara: The Learning Community School Improvement Initiative, the initiative leaders and School Achievement Facilitators, the Woolf Fisher Research Centre at The University of Auckland, and Ministry of Education representatives. The representatives from an original group of eight schools formed an assessment team to work with researchers, the Ministry of Education and the initiative leaders on developing an intervention to raise student achievement.

The collaboration involved a replication of an innovative approach to research–practice partnerships. The purpose was to determine the extent of the challenges for effective teaching of comprehension, and to create better teaching methods to meet those challenges. As part of this, a cluster-wide intervention for all teachers teaching classes at Years 5–8 in the eight schools took place. This required extensive school-based professional development, as well as systematic collection of achievement data and classroom observations within a rigorous research design. The present research-based intervention was designed to test and replicate both the discrete components of effective teaching in school-wide implementation, and the model developed for a research–school practice partnership.

Research questions

This study: aims and research questions

This present study (“the Otara study”) is a replication of a previously reported three-year research and development partnership to raise student achievement in reading comprehension (“the Mangere study”’). It aims to experimentally test hypotheses about how to raise the achievement in reading comprehension of students in a cluster of Otara schools, through a planned and sequenced research-based collaboration. The study addresses several areas of strategic importance to New Zealand, as previously noted.

The study also addresses specific theoretical questions. These are to do with the development of reading comprehension; effective instruction for reading comprehension; the development and role of professional learning communities; the role of (contextualised) evidence in planned interventions; and the nature of effective research collaborations with schools and the nature of replications. The specific research questions were:

- can the process and outcome of the previous intervention be replicated?

- can features of teaching and learning be identified for effective instructional activities that are able to be used by teachers to enhance the teaching of comprehension for Māori and Pasifika children in Years 5–8 in decile 1 schools in Otara?

- in what respect are they the same or different from a previous cluster of decile 1 schools in Mangere?

- can a research–practice collaboration develop a cluster-wide professional development programme that has a powerful educationally significant impact on Māori and Pasifika children’s comprehension at Years 5–8 in decile 1 schools in Otara?

A general hypothesis derived from these areas is that instructional approaches to reading comprehension present in the cluster of schools could be fine-tuned to be more effective in enhancing achievement through a research–practice collaboration, and the development of professional learning communities, using contextualised evidence of teaching and learning.

The research base for each of these areas is outlined in the following sections.

What this report covers

This report describes the results of the research and development programme in action, as researchers and practitioners developed communities to meet the challenge of building more effective instruction for reading comprehension in linguistically and culturally diverse urban schools. The design methodology and frameworks for the interventions are described in Section Two. Section Three describes the results of these interventions for the overall three-year research and development partnership between schools and researchers. In the final section, results are summarised and discussed.

2. Methods

The overall partnership involved schools in the Ministry of Education, Otara: The Learning Community School Improvement Initiative, the initiative leaders, the Woolf Fisher Research Centre at The University of Auckland, and Ministry of Education representatives.

Main study participants

Schools

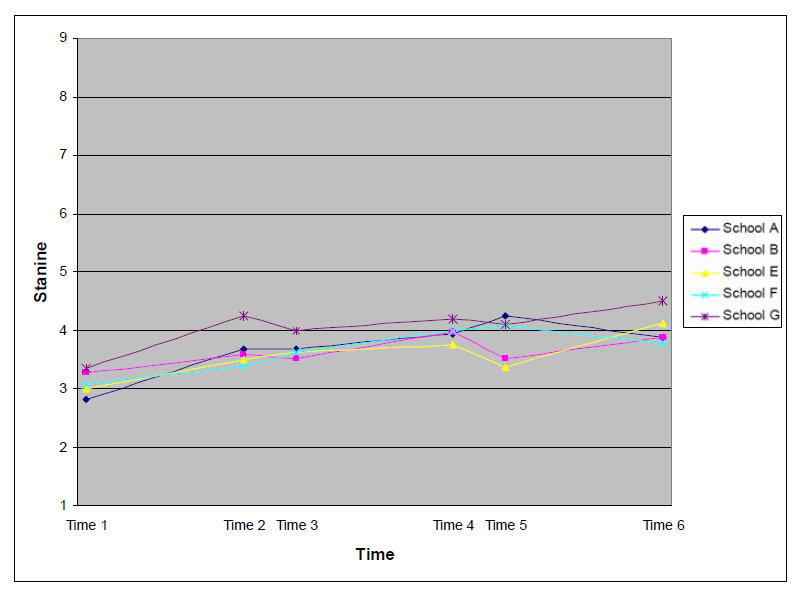

The Otara study originally involved eight decile 1 Otara schools. Six of these schools were contributing schools (Year 1–Year 6), one was an intermediate school (Year 7–Year 8), and one was a middle school (Year 7–Year 9). The schools ranged in size from 62 students to 470 students. One of the schools participated in only the first round of data collection; hence the analyses of gains are for seven schools, while the baseline profiles include eight schools.

Students

We report on several overlapping groups of students. The first group consists of all the students present at the beginning of the three-year study (Baseline sample). The second consists of one cohort of students who were followed longitudinally, starting from Year 4. The third group consists of all students who were present at the beginning and at the end of each year. The fourth group was all students present at any one time point.

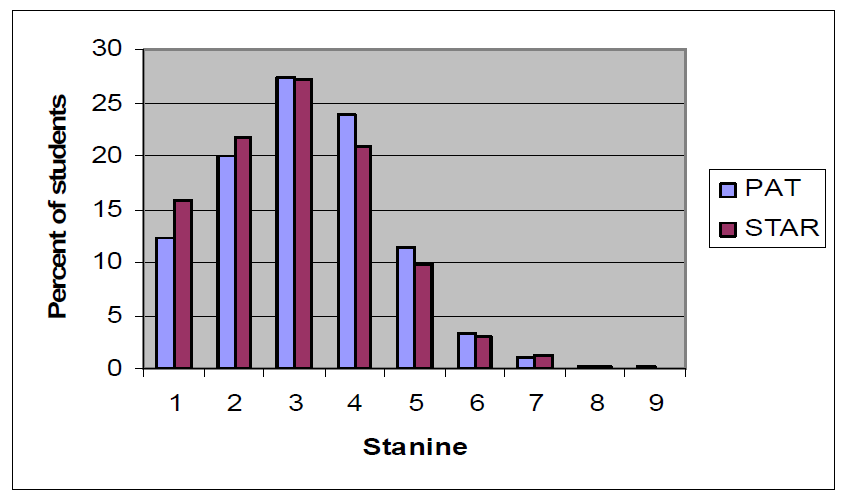

Overall baseline samples

Baseline data using STAR and PAT (February 2004) were collected from 1646 students in eight schools. Different combinations of students sat the STAR and PAT tests for various reasons (e.g. being absent when the STAR test was administered but present when the PAT was administered). In addition, one school was unable to participate in the first round of STAR data collection.

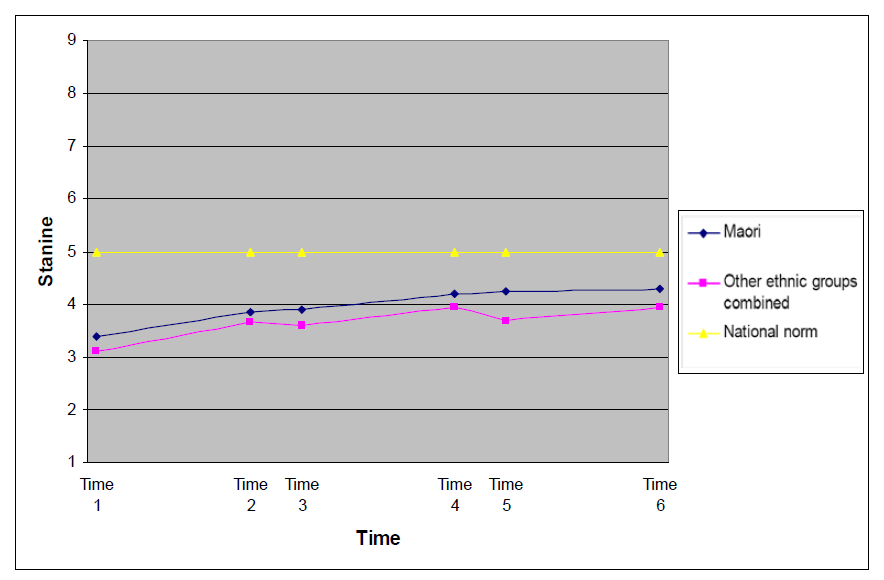

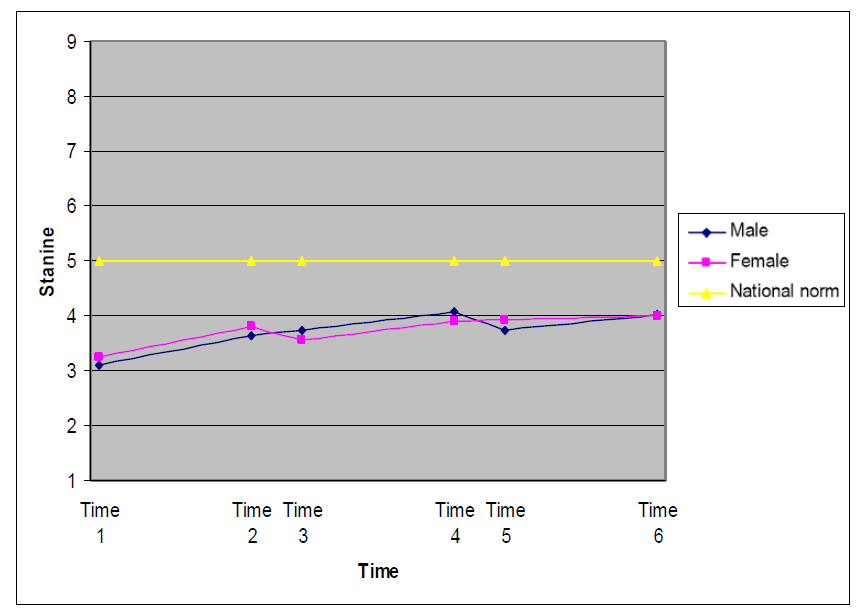

The numbers of students at each year level were: Year 4 (mean age 8 years) n = 298; Year 5 (mean age 9 years) n = 311; Year 6 (mean age 10 years) n = 339; Year 7 (mean age 11 years) n = 370; and Year 8 (mean age 12 years) n = 328. The total group consisted of almost equal proportions of males and females (53% and 47% respectively) from 14 ethnic groups. Four main ethnic groups made up 93 percent of the sample. These groups were Samoan (37%), Māori (22%), Cook Island (19%), and Tongan (15%). Approximately half the children had a home language other than English.

Longitudinal cohorts

One cohort of students was followed longitudinally from Time 1 to Time 6; these were those students who were Year 4 at Time 1 and who were present at all six time points, a total of 98 students. This cohort was labelled Cohort 1. (We could only follow one cohort of students over three years because schools in the sample were either contributing primaries (Years 1–6) or were intermediate and middle schools.) These students were a subset of the students included in the baseline sample.

Overall group year by year

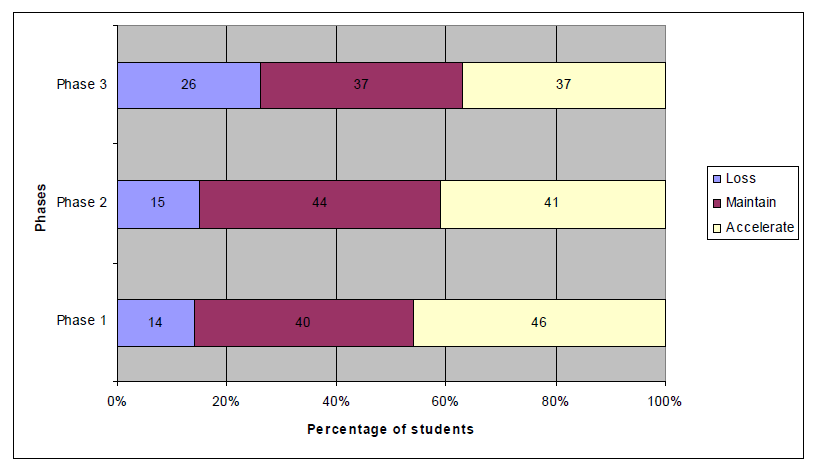

A third group of students were those present at the beginning and end of each year. In Year 1 (Phase One, 2004) there were n = 973; in Year 2 (Phase Two, 2005) there were n = 924; and in Year 3 (Phase Three, 2006) there were n = 663. All of the students who were in the longitudinal cohort group were part of these groups, but these groups also included students who were present for only a single year, including Year 7 and Year 8 students, new Year 4 students (in the second and third year), new students arriving at the school and staying at least a year, and students who were present for a year only. These data do not include one school that pulled out after participating in the baseline sample. Phase Three does not include one school which pulled out after Phase Two.

Total school population

A fourth group of students were all the students present at each time point and so included new students and students who subsequently left the school. The number varied from 1374 (Time 1) to 814 students (Time 6).

Teachers

Around 50 teachers were involved in each year of the project, including literacy leaders. Characteristics of the teachers varied somewhat from year to year, but in general around twothirds had five or more years of experience, and 10 percent were beginning teachers. In the second year, 25 percent of the teachers were Pasifika or Māori.

School reading comprehension lessons

Observations were carried out early in the intervention (see below), and they provided a general description of the programmes across phases through which the intervention was delivered. Generally the programme was similar across classes and schools, and similar to the general descriptions of New Zealand teaching in the middle grades (Ministry of Education, 2006a; Smith & Elley, 1994).

The general structure of the reading programme comprised a daily session for 60 to 90 minutes starting with a whole-class activity, typically reading to children or shared reading, followed by small-group work. Children were grouped by achievement levels (using reading ages from assessments of decoding and comprehension) into between three and five groups. The teacher typically worked with one or two groups per day, usually using a guided-reading approach or a text/task study. They often used the same text for a week, which might be linked to topic study (in social studies or science) or a genre focus. Most classes observed (n = 10) had Sustained Silent Reading (SSR) for 10–15 minutes and forms of Buddy reading or Reciprocal Reading/teaching. When working independently, groups completed worksheets on text-related tasks such as identifying main themes or doing a text reconstruction, answering comprehension questions, preparing book reviews, or word study. In some classrooms, deliberate discussion, analysis, and practice with test formats occurred in which the skills required by tests such as cloze tests were highlighted.

A noticeable feature in classrooms was the use and explication of technical terms relating to written language and comprehension: for example, explicit identification and discussion of strategies (such as reciprocal reading, finding the main ideas, predicting), types of texts (such as story/article, genre); properties of types of texts (plot, setting, problem) or language unit types (such as synonyms, adjectives, “wh” questions, opinion, and even “contextual clues”).

There was some variation in this generalised description. For example, with older classes or special timetabling arrangements, a lower frequency of class reading sessions occurred. Four of the classrooms varied in frequency of shared reading (conducted weekly), and in two classrooms the guided and shared reading session occurred once a week. A noticeable and typical feature of the lessons was the high levels of engagement which was maintained for up to ninety minutes, both by the teacher-led groups and the independent groups. Teacher aides were present in several classrooms, often working with the lowest-achievement group.

Design

Rationale for the quasiexperimental design

At the core of the following analyses is a quasiexperimental design from which qualified judgements about possible causal relationships are made. While it has been argued that the gold standard for research into schooling improvement is a full experimental design, preferably involving randomised control and experimental groups over trials (McCall & Green, 2004), a quasiexperimental design was adopted for two major reasons. The first is the inapplicability of a randomised control-group design for the particular circumstances of this project. The second is the usefulness of the quasiexperimental design format, given the applied circumstances.

Schools are open and dynamic systems. Day to day events change the properties of teaching and learning and the conditions for teaching and learning effectively. For example, in any one year teachers come and go, principals may change, the formula for funding might be altered, and new curriculum resources can be created. More directly, teachers and schools constantly share ideas, participation in professional conferences and seminars adds to the shared information, and new teachers bring new knowledge and experiences. Such inherent features of schools are compounded when the unit of analysis might be a cluster of schools who deliberately share resources, ideas, and practices.

This “messiness” poses tensions in a randomised experimental and control-group design. On the one hand, the internal validity need is to control these sources of influence so that unknown effects do not eventuate which may bias or confound the demonstration of experimental effects. On the other hand, if schools are changed to reduce these influences so that, for example, there is no turnover in teaching staff, external validity is severely undermined because these conditions may now not be typical of schools in general.

It is of course possible to conceive of selecting sufficiently large numbers of teachers or schools to randomly assign. Then one assumes that the messiness is distributed randomly. If the teachers and the schools in the total set are “the same”, then the error variance associated with this messiness is distributed evenly across experimental and control classrooms and schools. Leaving aside the challenges which large numbers of schools pose, a problem here is the assumption that we know what makes teachers and schools similar, and hence are able to be sure about the randomisation process. This is a questionable assumption to make. For example, in our previous study with a similar cluster of schools (McNaughton et al., 2006) the presence of bilingual classrooms in some schools, with different forms of bilingual provision, created difficulties for random assignment as well as for comparability across teachers, let alone across schools. So what counts as an appropriate control is not necessarily known. There may also be insufficient instances of different types of classrooms or schools even to attempt random assignment.

There is another difficulty: that of withholding treatment from the control group of schools. Just about any well-resourced, planned intervention is likely to have an effect in education (Hattie, 1999). The act of deliberately withholding treatment, as required in control-group designs, raises ethical concerns. Some researcher groups in the United States, also concerned with educational enhancement for schools serving poor and diverse communities, have deliberately adopted alternatives to randomised experimental and control-group designs because of ethical concerns for those settings not gaining access to the intervention (Pogrow, 1998; Taylor et al., 2001). Hattie (1999) proposed that the ethical difficulty could be overcome by comparing different interventions, thus not withholding potential benefits from any group. This is not always a workable solution, for example when the theoretical question is about the effects of a complex, multicomponent intervention that reformats existing teaching in a curriculum area, such as literacy instruction. Here there is no appropriate alternative intervention other than existing conditions. The American Psychological Association has detailed guidelines for conditions under which withholding treatment is justified. For example, if an intervention is shown to be effective, then it should be implemented in the control group. This route has similarities with the design proposed below.

The most problematic aspect however, is the underlying logic of experimental and control-group designs. In these designs, the variation within each group (given the simple case of an experimental and a control group) is conceived as error variance and, when substantially present, is seen as problematic. The alternative design adopted below is based on a view of variability as inherent to human behaviour generally (see Sidman, 1960), and specifically present in applied settings (Risley & Wolf, 1973). It deliberately incorporates variability and the sources of that variability into the design. Questions about the characteristics and sources of variability are central to knowing about effective teaching and learning, and can be explored within the design. Such a design is more appropriate to the circumstances of building effectiveness over a period of time, given that the variability is an important property (Raudenbusch, 2005). Similarly, such designs are useful in the case of planning for sustainability with ongoing partnerships. In fact, longitudinal designs are recommended in which sources of variability are closely monitored and related to achievement data, such as levels of implementation, the establishment of professional learning communities, coherence of programme adherence, and consistency of leadership and programme focus over time (Coburn, 2003). These are all matters of concern in the research reported here.

Repeated measures of children’s achievement were collected in February 2004 (Time 1), November 2004 (Time 2), February 2005 (Time 3), November 2005 (Time 4), February 2006 (Time 5), and November 2006 (Time 6) as part of the quasiexperimental design (Phillips et al., 2004). The design uses single case logic within a developmental framework of cross-sectional and longitudinal data. The measures at Time 1 generated a cross section of achievement across year levels (Years 4–8), which provided a baseline forecast of what the expected trajectory of development would be if planned interventions had not occurred (Risley & Wolf, 1973). Successive stages of the intervention could then be compared with the baseline forecast. The first of these planned interventions was the analysis and discussion of data. The second was the development of instructional practices. The third was a phase in which sustainability was promoted. This design, which includes replication across cohorts, provides a high degree of both internal and external validity. The internal validity comes from the in-built testing of treatment effects described further below; the external validity comes from the systematic analysis across schools within the cluster.

The cross-sectional baseline was established at Time 1 (February 2004). Students from that initial cross section were then followed longitudinally and were retested at Times 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6, providing repeated measures over three school years. Two sorts of general analyses using repeated measures are possible. Analyses can be conducted within each year. These are essentially before and after measures. But because they are able to be corrected for age through transformation into stanine scores (Elley, 2001), they provide an indicator of the impact of the three phases against national distributions at similar times of the school year. However, a more robust analysis of relationships with achievement is provided using the repeated measures within the quasiexperimental design format. They show change over repeated intervals.

As argued in the introduction chapter, good science requires replications (Sidman, 1960). In quasiexperimental research, the need to systematically replicate effects and processes is heightened because of the reduced experimental control gained with the design. In the design used with the present cluster of schools, there were inbuilt replications across age levels and across schools within the quasiexperimental design format. These provide a series of tests of possible causal relationships. However, there are possible competing explanations for the conclusions of the cluster-wide results that are difficult to counter with the quasiexperimental design. These are the well-known threats to internal validity, two of which are particularly threatening in the design adopted here.[2]

The first is that the immediate historical, cultural, and social context for these schools and this particular cluster meant that an unknown combination of factors unique to this cluster and these schools determined the outcomes. Technically, this is partly an issue of “ambiguous temporal precedence”, and partly an issue of history and maturation effects (Shadish, Campbell, & Cook, 2002).

A second is that the students who are followed longitudinally and were continuously present over several data points were different in achievement terms from those students who were present only in the baseline, and subsequently left. It might be, for example, that the comparison groups contain students who were more transient and had lower achievement scores. Hence over time, as the cohort followed longitudinally is made up of just those students who are continuously and consistently at school, scores rise. Researchers such as Bruno & Isken (1996) report lower levels of achievement for some types of transient students. This is partly an issue of potential selection bias, and partly an issue of attrition (Shaddish et al., 2002). As the projected baseline is based on the assumption that the students at baseline are similar to the cohort students, having a lower projected baseline may result in finding large improvements due to the design of the study, rather than to any real effects.

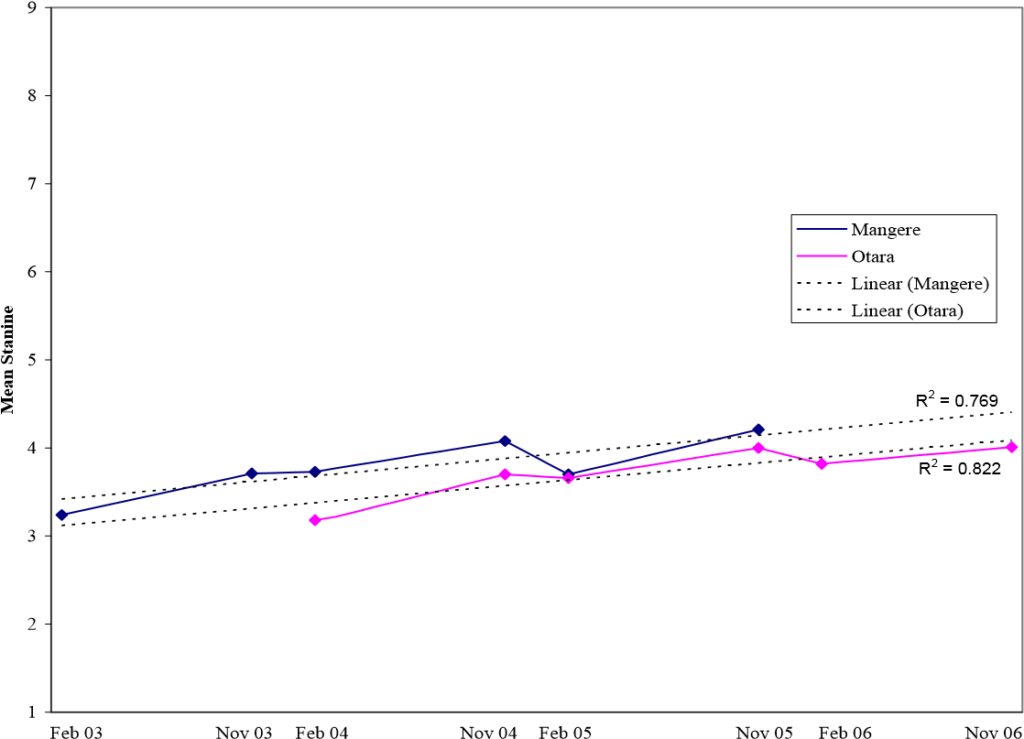

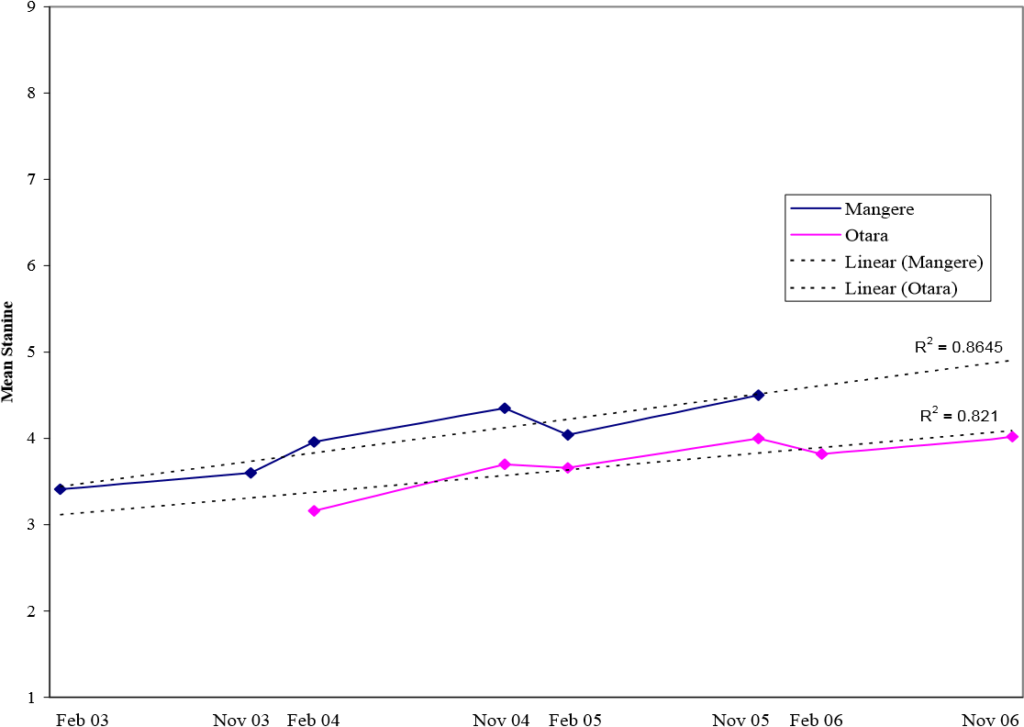

There are three ways of adding to the robustness of the design, in addition to the inbuilt replications, which meet the major threats. The first is to use as a comparison a similar cluster of schools that received the intervention at a different time. The first study with Mangere has that function as it started a year before the intervention in the Otara cluster of schools. It was possible to identify and examine the baseline levels in the Otara cluster of schools after a year of intervention in the Mangere cluster, to check whether levels in the Otara cluster had changed significantly associated with the intervention starting in the Mangere cluster. If that happened the judgement of causality would be severely undermined. The Mangere and Otara clusters of schools were similar in geographical location (neighbouring suburbs); in type (all decile 1 schools); in number of schools (n = 7–8); in number of students (n = approximately 1400–1700); in ethnic and gender mix (almost equal proportions of males and females from about 14 ethnic groups, the major groups being Samoan, Māori, Cook Island, and Tongan); in starting levels of achievement; and in prior history of interventions. The Otara cluster was measured exactly one year after the baseline was established in the Mangere cluster, reported in Lai et al. (2006).

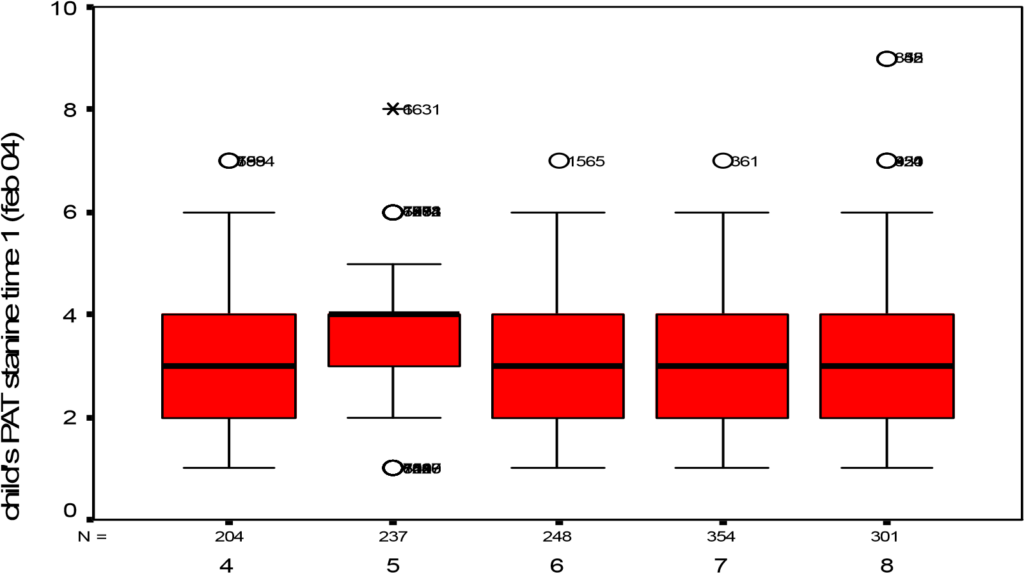

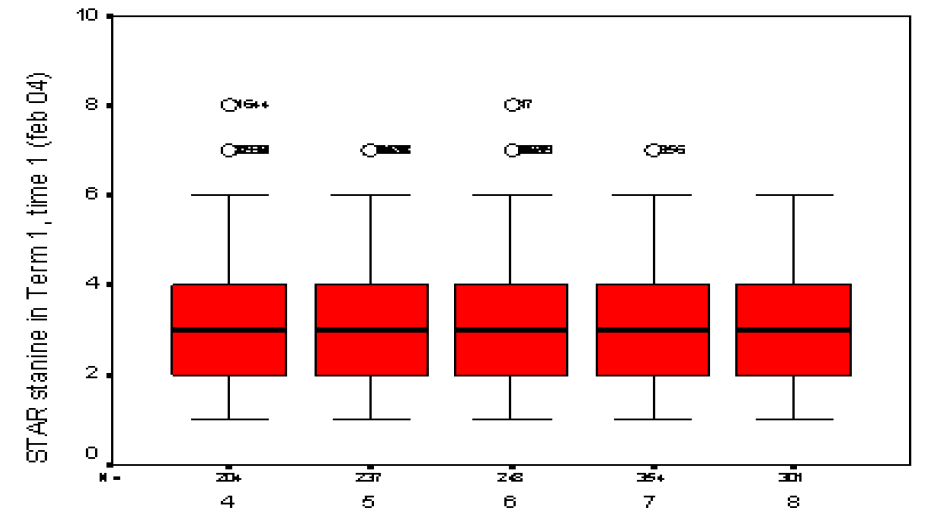

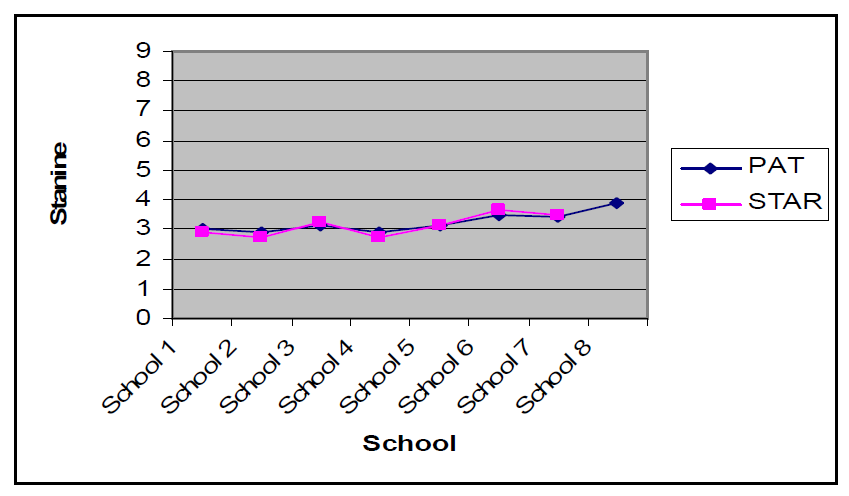

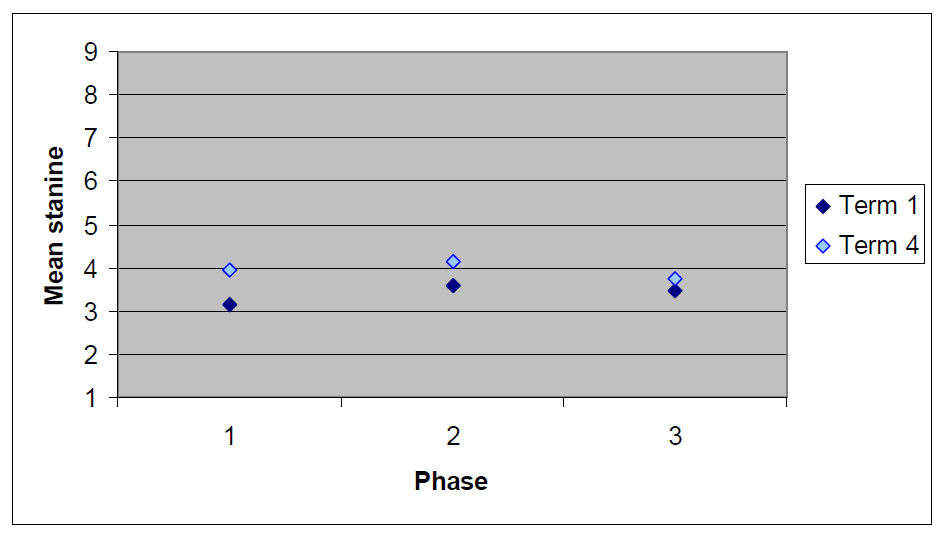

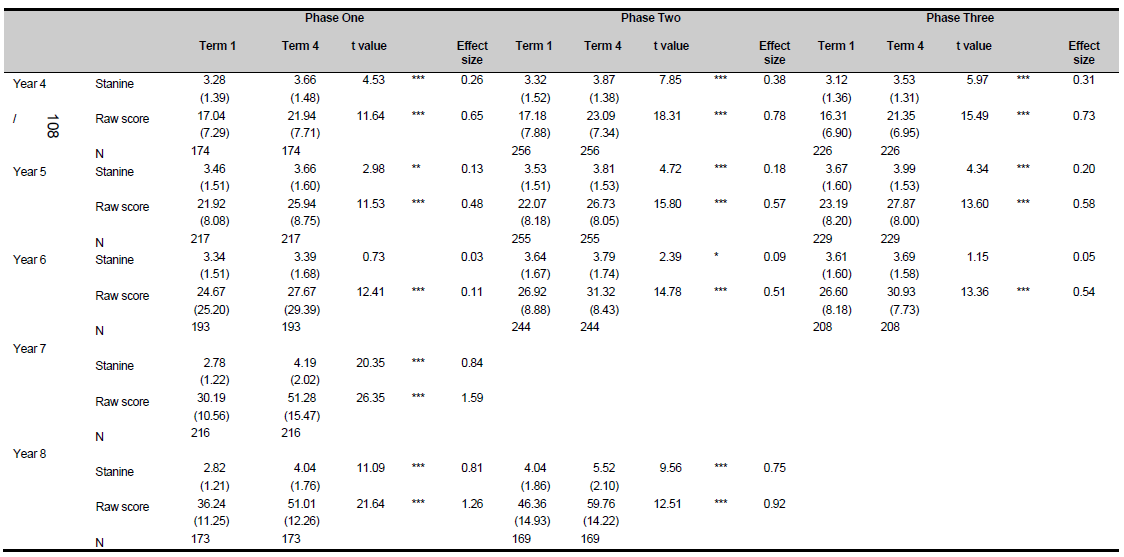

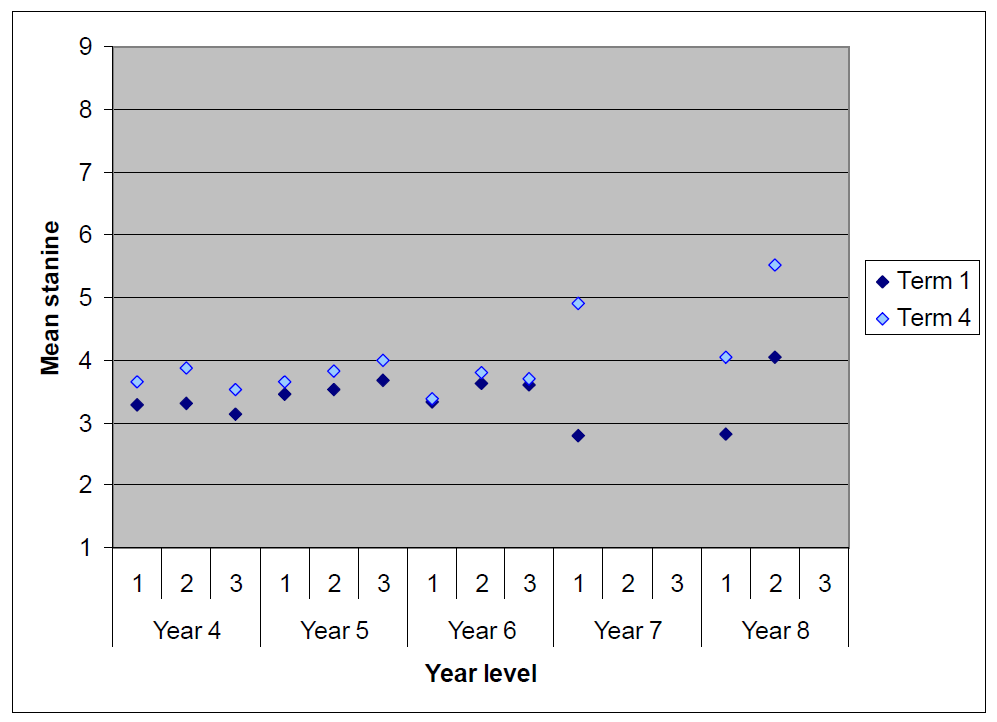

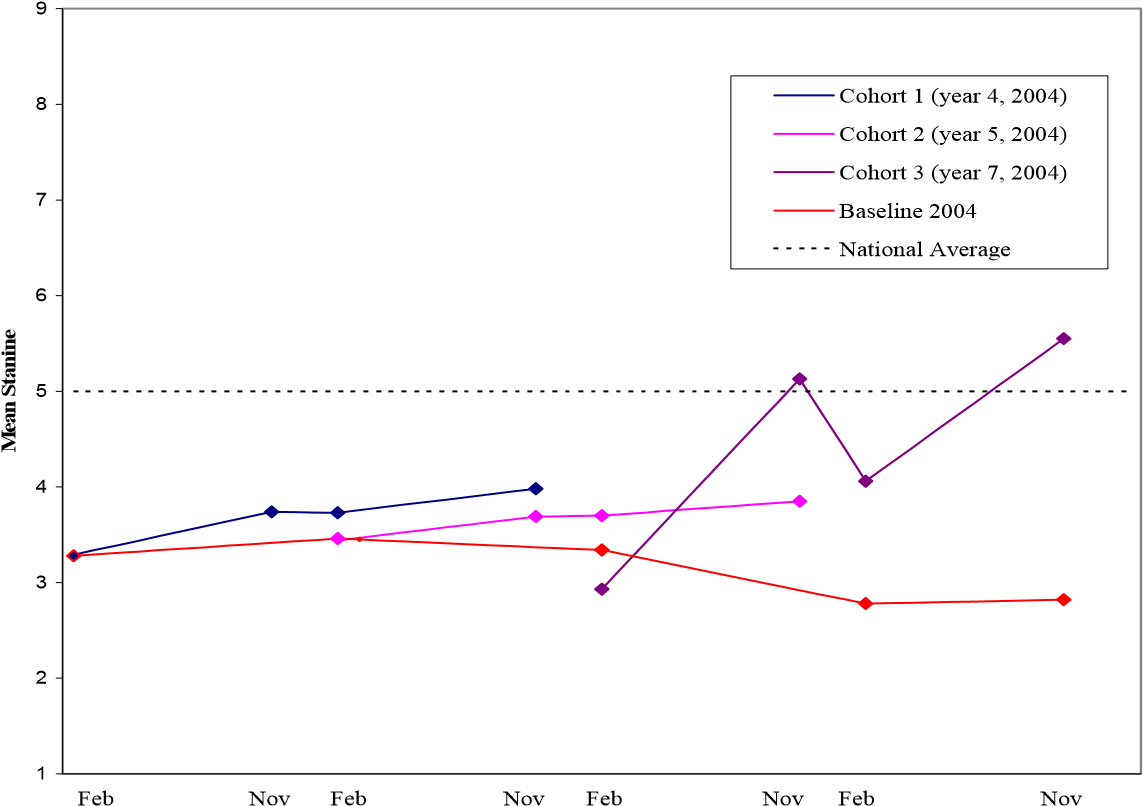

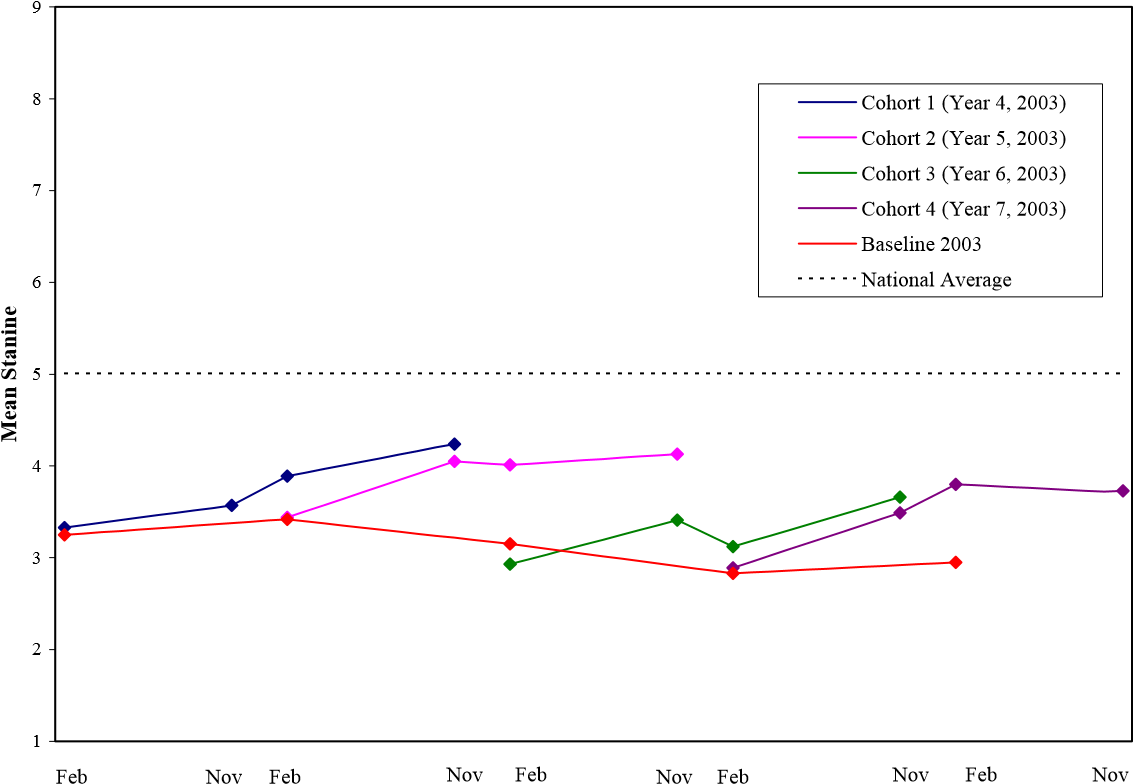

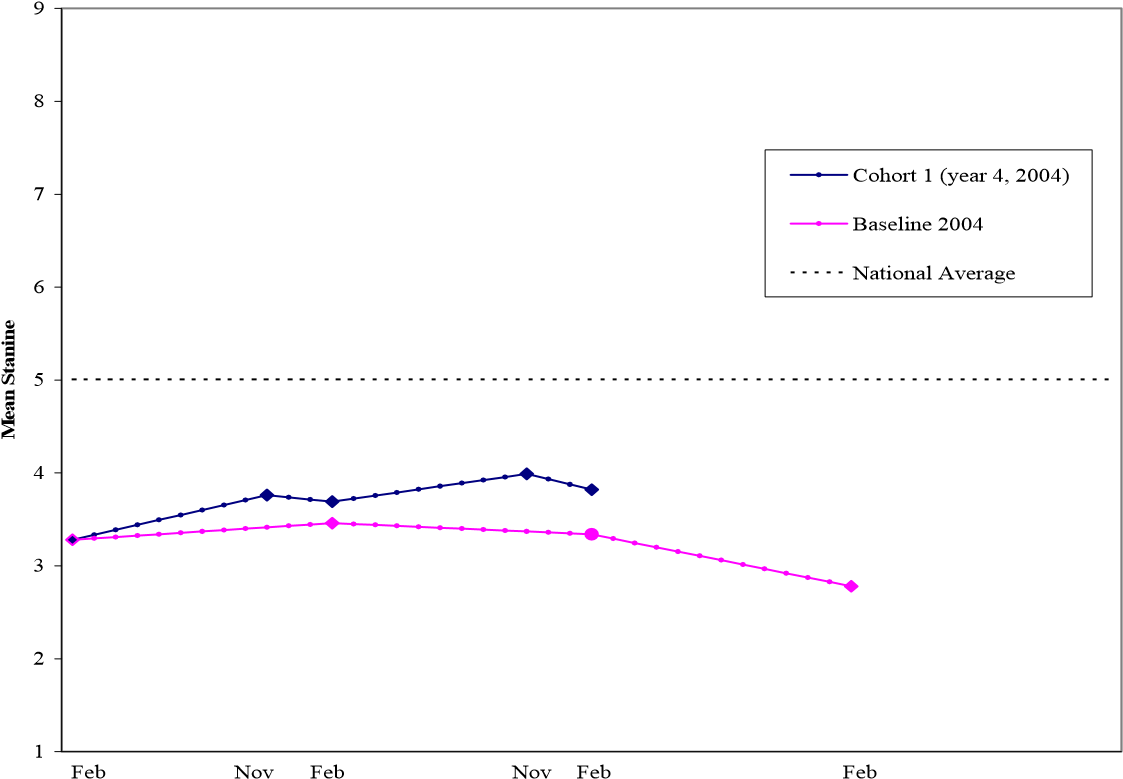

The two baselines are shown in Figure 1 and Figure 2. The comparison shows that before the intervention, the second cluster of schools had similar levels of achievement to the Mangere cluster of schools. This was so even though there was a delay of a year; and after an intervention had been in place for a year in the Mangere cluster of schools. As we reported earlier, achievement levels had risen in those schools in the year prior to the present study. This comparison adds weight to our previous conclusions by establishing that there was no general impact on similar neighbouring area decile 1 schools operating over the time period of the intervention in the Mangere cluster of schools.

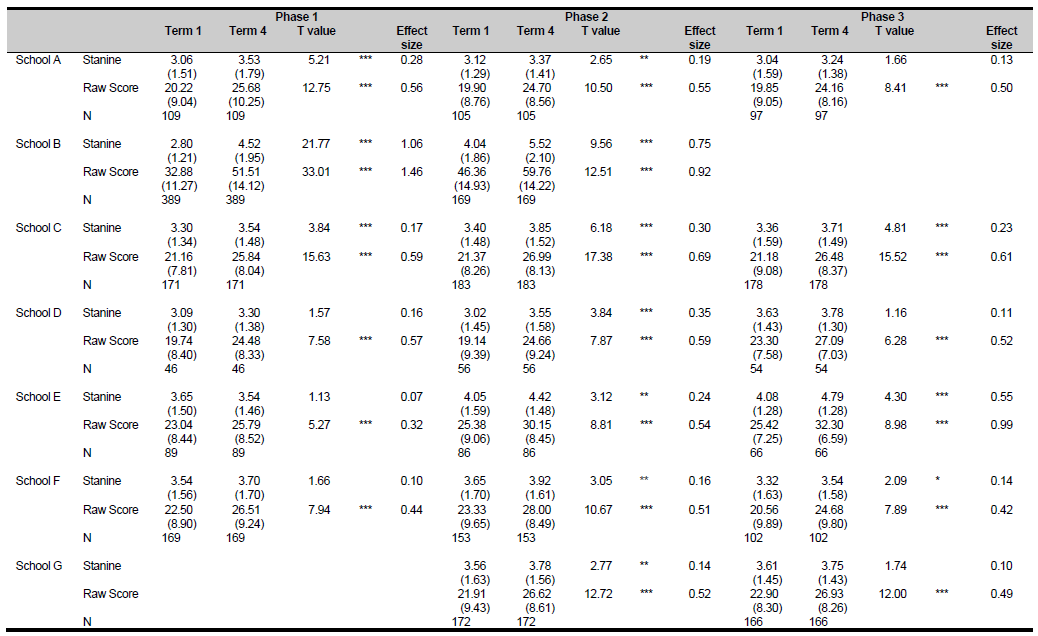

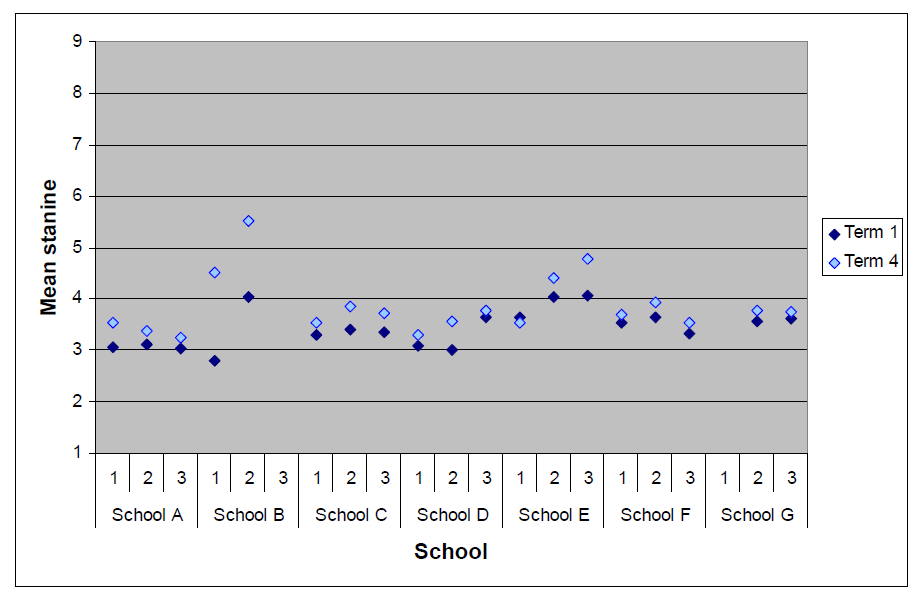

| Figure 1 Baseline (at Time 1) student achievement by Year level for Cluster 1 (Mangere) |

Figure 2 Baseline (at Time 1) student achievement by Year level for Cluster 2 (Otara) |

|

|

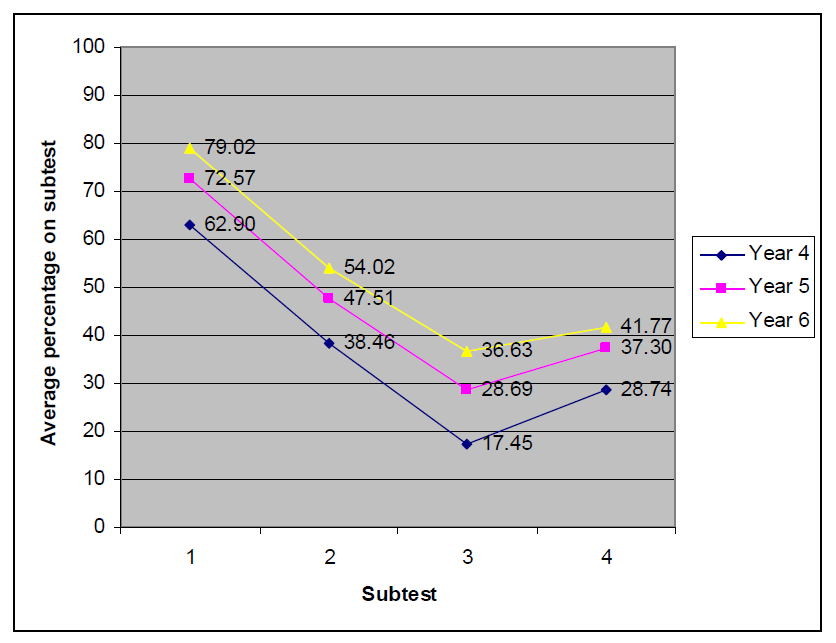

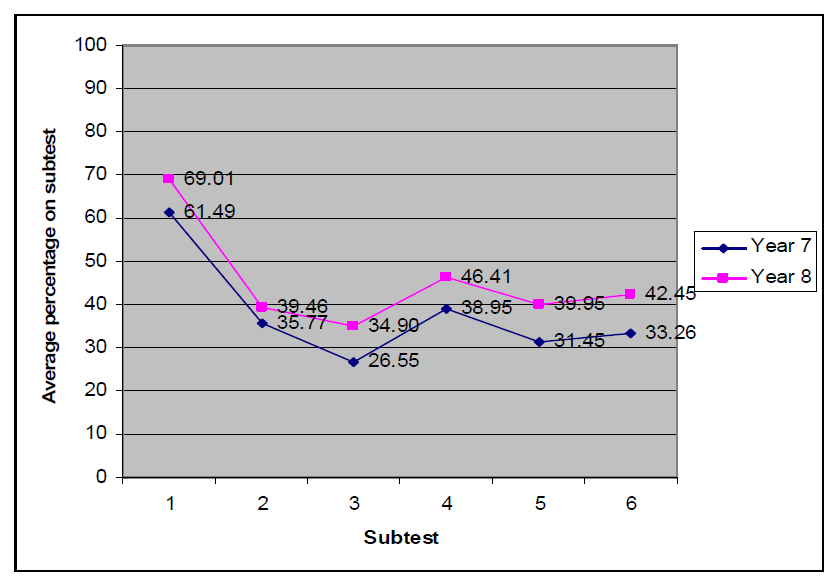

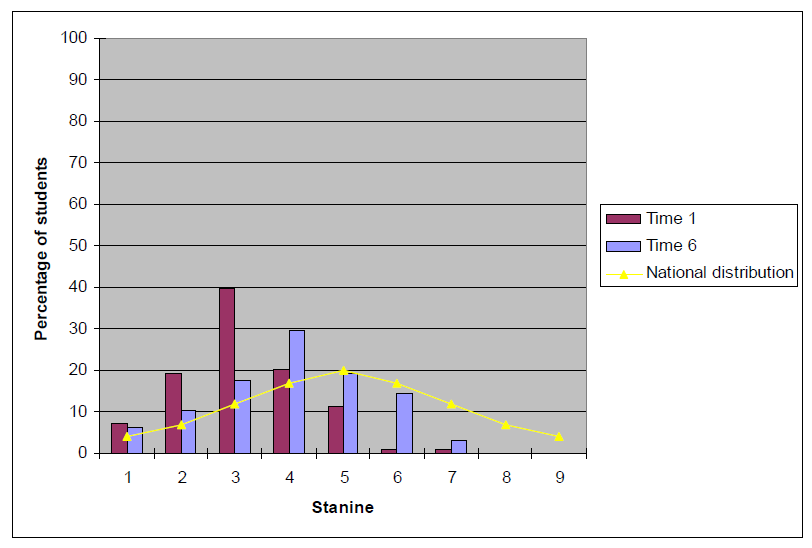

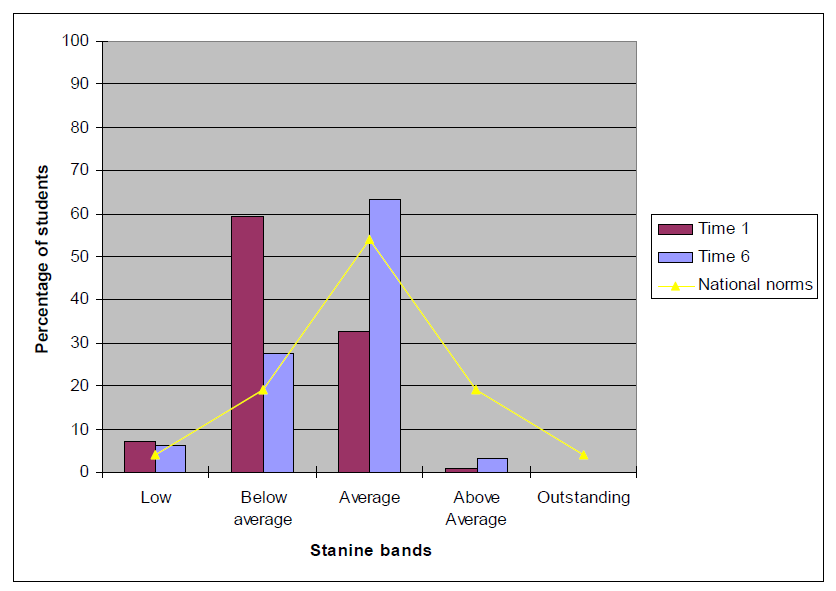

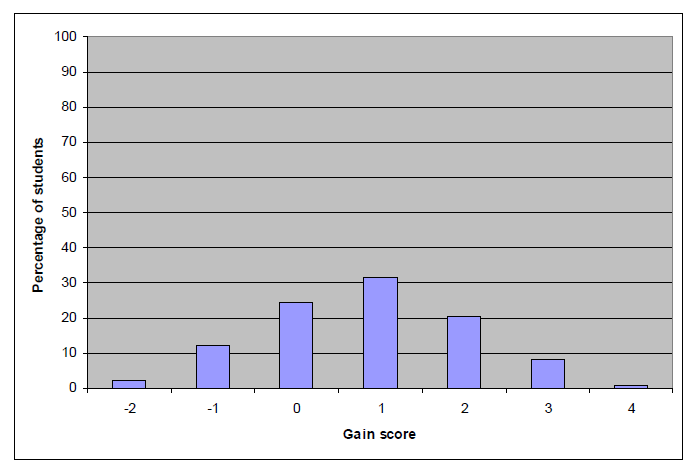

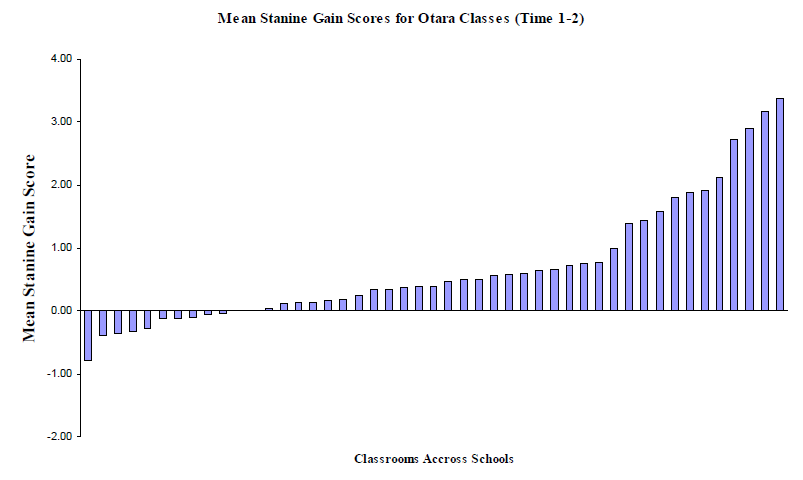

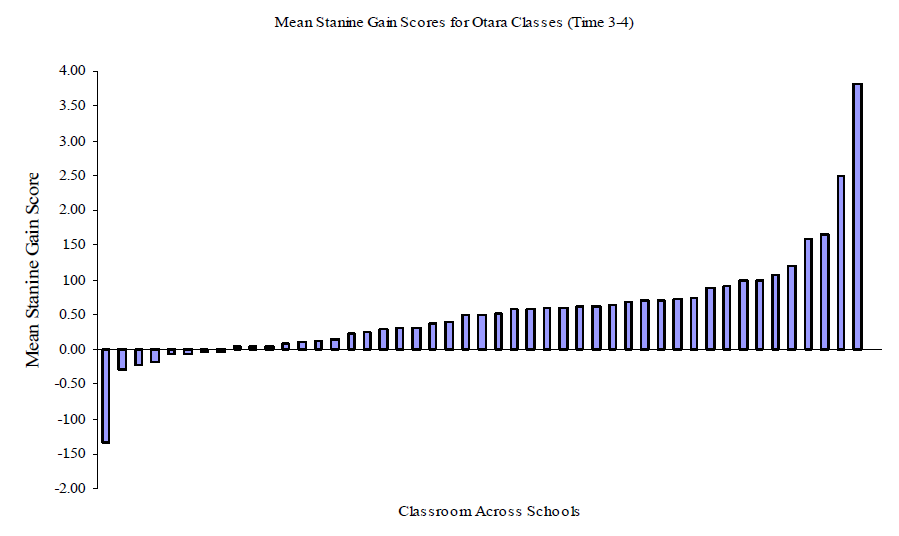

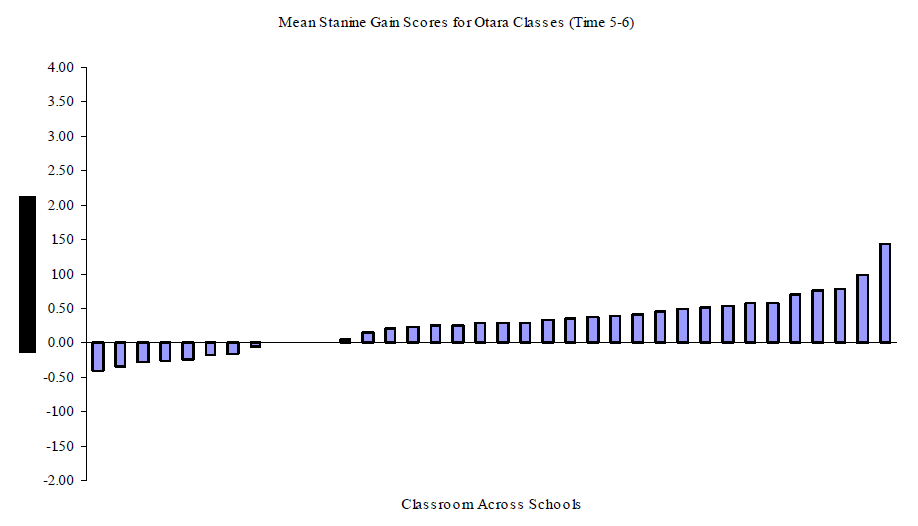

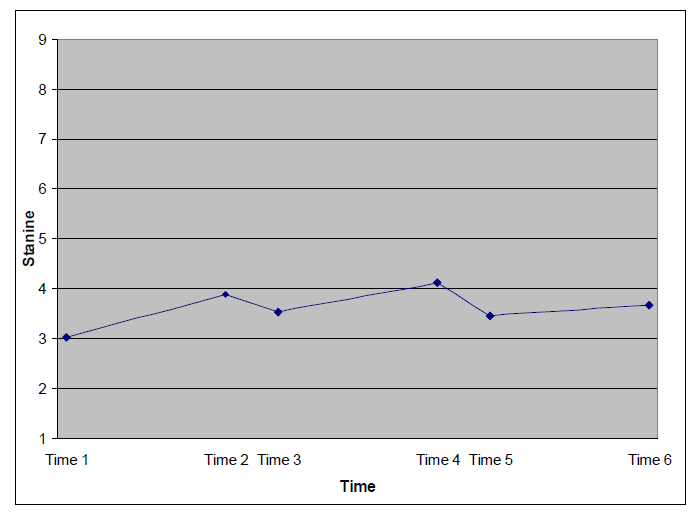

Figure 3 shows student achievement over the three years of the intervention in the Mangere cluster of schools, summarised by years, and the student achievement scores over the three years of the intervention in the Otara cluster of schools, summarised by years (these findings are repeated in detail below). What the figure shows is that the changes in student achievement did not happen at the same time. That is, in each cluster of schools the changes in student achievement took place during the intervention and not before, thereby adding to the robustness of the design and indicating that the changes were unique to the intervention in the particular cluster of schools at that particular time.

Figure 3 Cluster 1 (Mangere) and Cluster 2 (Otara) intervention summarised by years