Please also refer to the PDF version of this guide, which includes additional visual elements.

The text and key diagrams from the guide are reproduced here

Introduction

The purpose of this guide is to assist developers in tertiary institutions to build effective assessment policy.

The guide is based on a review of the international literature and research of best practice in tertiary assessment, a review of tertiary education institution assessment policy documents in New Zealand and Australia, surveys of academic staff and students at four New Zealand tertiary institutions, and interviews with senior academic managers at seven New Zealand tertiary institutions.

The findings[1] from these reviews support a set of considerations for assessment policy and practice guidelines in higher education. The guide does not specify how these should be addressed, as every institution, department, and programme will need to accommodate their own particular situations. Academic managers consistently recommend that overarching institutional policies should give guidance without being prescriptive, as different departments and even programmes will have differing requirements, challenges, and external regulating bodies (such as for architecture, medicine, teaching, law, engineering, and so on).

The guide emphasises the need to:

- align assessment with learning outcomes and the graduate profile

- have a strong focus on assessment to improve student learning

- support a variety of methods of assessment, including utilisation of the electronic tools currently available.

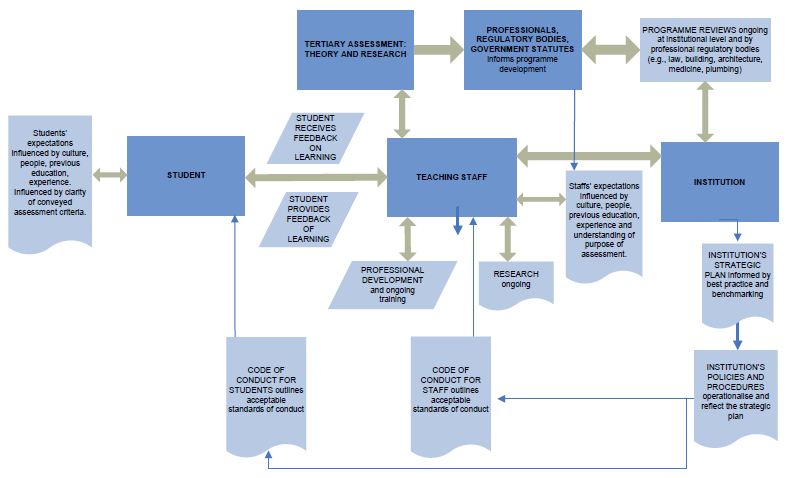

Diagram 1: Factors Informing the Assessment Process highlights the relationship between the four key stakeholders: the student; teaching staff; institutional management; and the professions, regulatory bodies and statutory law. The diagram indicates the responsibilities of each and how the process is ongoing with both international best practice and stakeholder expectations, actions, and responses being informed by one another.

[1] See also Tertiary Assessment and Higher Education Student Outcomes: Policy, Practice, and Research (Meyer, et al., 2009).

Diagram 1: Factors Informing the Assessment Process

Key Elements of Assessment Policies

The purposes of assessment

The first key research finding is that assessment policy must make explicit reference to the functions and purposes of assessment; principles should guide assessment policy. Three main purposes for assessment are discussed below and each merits attention in policy development:

- feedback on learning (students and teachers)

- selection and progression decisions (students, teachers and institutions)

- quality assurance and accountability (institution-wide responsibilities).

A. Assessment policies for providing feedback on learning

Existing institutional policy is largely silent on this issue, which is perhaps the one most valued by students and tertiary teachers. Policy should address:

- feedback to students. Timely feedback that students can use to improve their demonstrations of learning has been shown by research to enhance student learning. Who provides feedback (e.g., instructors versus outside markers), when, and how often should be considered. Some call this ‘formative assessment’, but whether or not marks are given, feedback during the learning process is essential

- using a range of assessment types, rather than being restricted to more traditional essays and exams

- training teachers/instructors in assessment, including use of different assessment types, validity and reliability issues, giving effective feedback, and so forth

- using assessment feedback to improve teaching. Assessments enhance student learning, but instructors should also use assessment information to identify misconceptions and misunderstandings as well as patterns in student learning to inform teaching approaches. Student evaluations can be a tool for instructors to review teaching practices.

B. Assessment policies to measure student learning for selection and progression decisions

This assessment purpose encompasses measures of what and how much students have learned. This is an obvious assessment purpose, yet is sometimes overlooked in tertiary policies. Policy should address:

- matching assessments to learning outcomes, not only within a course but within and across course levels and programmes

- ensuring assessments are valid and reliable. The validity of an assessment in measuring learning is often taken for granted, but may not be supported by the data. Instructors need training and support to do this

- making transparent assessment criteria available to students. Students cannot do their best if they do not know what they are working toward or what is expected of them

- having procedures for assessment moderation, including clear guidelines for and supervision of markers, especially if external markers are involved. What does moderation mean for your institution? How will it be addressed, and by whom?

- using a range of assessment types. In addition to exams, tests, and essays, there are many kinds of assessments which international and national research has shown to be effective, valid, and practical to use. Various types can help instructors deal with challenges such as large classes, difficult-to-measure learning, language issues, and giving feedback to students. Portfolio assessments can be particularly useful in professional programmes. How can your institution help to encourage instructors to find out about and try these?

- having policies for self-assessment and for the assessment of group work. Group work can be a valuable learning tool, but must be carefully managed by linking to learning objectives, ensuring assessment and expectations are fair, and monitored effectively. Self-assessment prepares lifelong learners

- measures of attainment of the Graduate Profile for programmes and degree qualifications.

C. Assessment policies for quality assurance and accountability

The survey found that students most often perceived this as the major purpose of assessment, so they perceived assessment as less meaningful to them. Indeed, most policy documentation examined emphasised accountability issues, while instructors were more focused on the first two purposes of assessment described above. There are risks for institutions that attend only to rules and regulations for quality assurance and accountability, including a negative impact on the quality and integrity of teaching, resulting in reputation consequences nationally and internationally. The focus of assessment purposes will guide policy development, so it is important for institutions to consider all assessment purposes.

Many policies for enhancing student learning and measuring learning can also apply to institutional accountability. For example, demonstrating instructor training and knowledge of using valid and reliable assessments can lead to improved student learning, more valid and reliable measurement of student learning and progress in a programme, as well as provide evidence of high standards and accountability to external regulators.

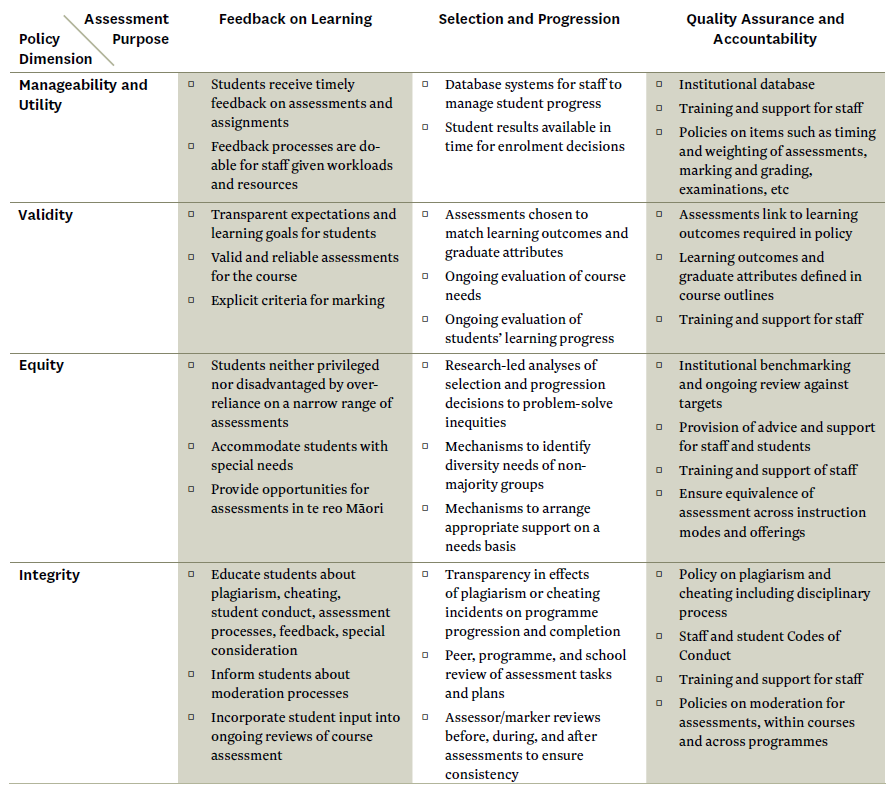

The Tertiary Assessment Grid

The Tertiary Assessment Grid (TAG) for assessment policy (see page 11) was developed to provide a mechanism for an institutional overview of assessment policy issues to address each of the three assessment purposes. The TAG allows a check for the three “purposes of assessment” abbreviated here as: Feedback on Learning, Selection and Progression, and Quality Assurance and Accountability.

The “Policy Aspects” highlighted in the TAG are:

- Manageability and Utility – the ‘nuts and bolts’ of assessment, including timing, managing feedback to students, tracking student progress, and so on

- Validity – ensuring that assessments are valid and reliable, and actually measuring what they are intended to measure

- Equity – ensuring students are treated fairly and equitably across mode of instruction, campuses and programmes, with appropriate consideration for issues of culture, language, disability and so on ▫ Integrity – preventing and managing plagiarism or cheating; moderation issues.

The three other overarching principles that should run through all of the assessment policy aspects and purposes are:

- ongoing institutional reflection

- teaching staff development

- engaging students in the assessment process. Tertiary Education Institution (TEI) policy should reflect these principles in how specific practices are put into place.

A. Ongoing institutional reflection on assessment policy

TEIs must continually review how policies are working and what improvements are needed to ensure quality, relevance, and currency in programme offerings. Reflection should be ongoing and undertaken at all levels of the institution, from the management level in relation to programme reviews to the individual teaching staff level. This ensures that assessment policies are responsive to the concerns and needs of students, staff, the subject fields/industries (e.g., law, engineering, architecture, hairdressing, plumbing, building, and so on) and are informed by current research findings.

To do this, institutions should evaluate policy and procedures by collecting evidence across all of the matrix fields, e.g., information from staff feedback, course and teaching evaluations by students, student achievement, student attrition, student completions, and awards and peer recognition at both national and international levels.

B. Teaching staff development

Teaching staff training is required for all aspects of assessment addressed in the TAG. Staff will have differing amounts of knowledge about these areas, so institutions will need to provide professional development, ongoing support, and resources. Additional tools that staff can use to inform their teaching are: current research in their field; student course evaluations; student attrition rates; student progression and completions; and student awards for achievement.

C. Engaging students in the assessment process

While research indicates that student learning is often driven by course assessments, students also often view assessment as obstacles or hurdles to overcome. Institutional processes surrounding assessment and accountability should be revisited to ensure these are viewed as transparent and fair by students. Students must be assured that engaging with the process is worthwhile, otherwise efforts by staff will have limited impact. Additionally, students (and staff) benefit from explicit emphasis on how assessments can be a tool for improving learning.

Tertiary Assessment Grid (TAG) for Assessment Policy with Examples

Steps to Policy Development

- Review best exemplars of current theory and research. See Appendix for a selection.

- Establish institution purposes of assessment:

-

- Identify the accountability requirements from external regulators and internal belief.

- Identify the institution’s learning intentions with regard to the graduate profile and consider how these apply to programmes.

- Establish institution principles of assessment:

-

- There are many taxonomies of principles; each institution may consider which principles best reflect their institution’s commitments, communities and workplace destinations.

- Identify capability issues:

-

- Effective assessment depends significantly on the knowledge and skills of lecturers; therefore, effective policy development will include institution level requirements for lecturer education and support for professional development.

- Map the internal systems that will engage with policy implementation:

-

- The disconnection between policy and practice is well noted. When policy is being developed is the time to identify lines of accountability and ensure that there are no loose ends.

- Policy evaluation:

-

- Include an evaluation process in the policy to ensure that the policy and its implementation are evaluated regularly to ensure continuous improvement.

- Write a draft document for wide consultation.

- Revise the document with consultation input.

- Circulate revised document for final review and approval.

Appendix: Useful Resources

Websites

(Ed – The original guide (2009) had a larger list of websites. This page has a partial list, compiled in 2024, which includes the functioning links – but excludes those that have expired.)

http://www.cshe.unimelb.edu.au/

The Centre for Study in Higher Education at Melbourne University has a website with a wealth of evidence-based information on a variety of assessment practices.

http://www.uq.edu.au/teaching-learning/index.html?page=63831

University of Queensland’s Excellence in Teaching and Learning. This website provides comprehensive advice focusing on quality teaching, resources and tools, staff development and progression, teaching and learning initiatives, and awards.

American Association for Higher Education & Accreditation (AAHE) http://www.polyu.edu.hk/obe/08_4_2.php

Massey University Assessment and Examination Regulations

Moderation

Moderation is used to ensure consistency and accuracy, particularly in the marking of student assignments. Moderation can be used in other contexts such as reviewing examination scripts before they are used to ensure that the assessment is matching course learning objectives, is appropriate for the level of the students, and the time available, etc. Moderation across various assessment elements in a course ensures that there is no unnecessary duplication of assessment.

Resources available relevant to moderation, see discussion papers: http://www.tedi.uq.edu.au/teaching/assessment/downloads.html

Moderation across one assignment:

http://www.auqa.edu.au/gp/search/detail.php?gp_id=2552

Moderation within a course, across courses, within schools, and institution-wide:

http://www.auqa.edu.au/gp/search/detail.php?gp_id=2967

AUQA Audit Manual:

http://www.auqa.edu.au/qualityaudit/auditmanuals/

Other useful assessment references

Biggs, J., & Tang, C. (2007). Teaching for quality learning at university (3rd ed.). Philidelphia: Open University Press.

Carless, D., Joughin, G., & Liu, N. (2006). How assessment supports learning: Learning-orientated assessment in action. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press.

Davidson, S., & McKenzie, L. (2009). Tertiary assessment and higher education student outcomes: Policy, practice, and research: Summary document. Wellington: Ako Aotearoa and Victoria University.

Maki, P. L. (2004). Assessing for learning: Building a sustainable commitment across the institution. Sterling, VA: American Association for Higher Education.

Meyer, L. H., Davidson, S., Anderson, H., Fletcher, R., Johnston, P. M., & Rees, M. (Eds.). (2009). Tertiary assessment and higher education student outcomes: Policy, practice, and research. Wellington: Ako Aotearoa.

Acknowledgements

This guide was supported in part by the Teaching and Learning Research Initiative, TLRI contract 9233 awarded to Victoria University with sub-contracts to Massey University, the Manukau Institute of Technology, and Te Whare Wānanga o Awanuiārangi, funded through Vote Education and administered by the New Zealand Council for Educational Research. Communications regarding this guide should be directed to Luanna Meyer at luanna.meyer@vuw.ac.nz

July 2009

© Victoria University of Wellington