Part A: Development of an instrument to capture critical elements of teachers’ literacy practice, Years 1-8

Eleanor Hawe and Judy Parr The University of Auckland

with Claire Sinnema (The University of Auckland),

Maria Heron, Wendy Koefed, Wendy Foster, and staff from their respective schools

Introduction

To date, much of the information we have about classroom practice has come from teacher selfreporting with data gathered through surveys, logs, diaries, and/or interviews (Burstein, McDonnell, Van Winkle, Ormseth, Mirocha & Guitton, 1995). To a lesser extent, information has been gathered about teachers’ classroom practice through structured observation schedules, video and/or audio recordings of lessons, student interviews, and the collection of artefacts including teachers’ documentation and students’ work (see for example, Henk, Marinak, Moore, & Mallette, 2003; Hoffman, Sailors, Duffy, & Beretvas, 2004; Junker, Matsumura, Crosson, Wolf, Levison, Weisberg, & Resnick, 2004; Stigler, Gonzales, Kawanaka, Knoll, & Serrano, 1999). An ongoing issue in the field has been the lack of agreement between multiple data sources. Burstein et al. (1995) for example reported a lack of agreement among survey, log, and artefact data in measuring various aspects of the curriculum. In addition, with respect to gathering data about the frequency of instructional activities, it was found that while teacher survey responses and daily logs averaged around 60 percent agreement, this agreement ranged from 28 to 80 percent depending on the actual activity, and teacher logs and independent observer data agreement ranged from 55 to 98 percent (Stigler et al., 1999).

More specifically, there are in New Zealand few if any widely used and proven tools for gathering information about teachers’ literacy practice. In contrast, researchers and teachers in the United States have access to a number of such tools. The majority of these however either lack alignment with the New Zealand context and/or emphasise the measurement of instructional practice in order to evaluate large-scale teaching reforms (e.g., Junker, Matsumara, Crosson, Wolf, Levison, Weisberg, & Resnick, 2004; Sawada, Piburn, Judson, Turley, Falconer, Benford, & Bloom, 2002). Thus a central purpose of the current project was to develop a reliable and valid means of capturing the critical elements of New Zealand teachers’ literacy practice in Years 1–8. It was intended that the approach taken to capturing these elements would have research and practical value, enabling researchers to sample classroom practice and teachers to identify areas for professional learning.

Following analysis and evaluation of possible approaches to gathering data about the critical aspects of teachers’ practice, it was decided that the primary tool for data collection would be a structured observation instrument (Observation Guide). This approach was deemed to offer the most practical, systematic and efficient means for researchers and teachers to capture and document what was happening in literacy programmes, as it was happening[1]. Development of the Observation Guide occurred over two phases: phase one (2006) and phase two (2007).

Developing the Guide: Phase one (2006)

The partners involved in phase one were three researchers from the University of Auckland and five teachers from two Auckland schools: Newmarket and Mangere Central. Newmarket is an inner city, decile 9, contributing primary school (Years 1–6 students) with predominantly Asian (43%) and Pakeha (39%) students. Mangere Central is a decile 1, South Auckland full primary school (Years 1–8 students) with predominantly Pasifika (71%) and Maori (28%) students. Sometimes the three university researchers met together, at other times they met with teachers from one or both of the school partners. These latter meetings, held at regular intervals throughout 2006, focused on identifying and reaching agreement about the critical elements of best practice in literacy teaching, expressing these elements as observable indicators and incorporating the indicators into an instrument that facilitated reliable observation and valid interpretation of teachers’ literacy practice. Involvement of practitioners in such activities is critical in establishing the validity and credibility of both the development process and the instrument.

Identifying and reaching agreement about the critical elements of teachers’ literacy practice

The university partners started the process by carrying out a search of national and international literature for research evidence that highlighted elements of effective literacy practice (e.g., AltonLee, 2003; Farstup & Samuels, 2002; Wray & Medwell, 2001). Findings are included in Table 1.

| Elements of effective literacy practice | Literature and research evidence |

|---|---|

| Activation of students’ prior literacy experiences and knowledge | Alton–Lee & Nuthall (1992, 1998); Mayo (2000); Myhill (2006) |

| Sharing the goals of learning with students; coconstructing the goals with students; students setting their own goals | Clarke (2005); Crooks (1988); Marshall (2004); Sadler (1989) |

| Sharing expectations with students about what constitutes successful learning (verbal descriptions; exemplars) | Clarke (2005); Marshall (2004); Sadler (1989)

|

| Sharing success criteria with students; coconstructing s/c with students; students creating their own s/c | Clarke (2005); Marshall (2004); Sadler (1989)

|

| Teachers have an expectation that all students can and will learn to read and write | Bishop, Berryman, Tiakiwai, & Richardson (2003); Phillips, McNaughton, & McDonald (2001); |

| School-based alignment between curriculum, pedagogy and assessment | Luke, Matters, Herschell, Grace, Barrett, & Land (2000) |

| Curricular alignment: alignment between goals of learning, task design (teaching/learning activities), teaching and feedback | Alton-Lee (2003); Alton-Lee & Nuthall (1992); Biggs (1999) |

| Teachers set challenging literacy activities for students | Ministry of Education (2003, 2006) |

| Teacher uses “deliberate acts of literacy teaching”: modelling; explanations; questioning; prompting; feedback; telling; directing | Freedman & Daiute (2001); Mayo (2000); Ministry of Education (2003, 2006); Myhill & Warren (2005) |

Use of a range of appropriate approaches to the teaching of reading:

|

Eke & Lee (2004); Ministry of Education (2003, 2006) |

Use of a range of appropriate approaches to the teaching of writing:

|

Eke & Lee (2004); Ministry of Education (2003, 2006) |

| Scaffolded learning (through, for example, explicit prompts, activities, peer involvement, feedback, appropriate resources/texts) | Alton-Lee & Nuthall (1998); Bishop, Berryman, Tiakiwai, & Richardson (2003); Clay (1979); McDonald (1993); Mayo (2000); Myhill & Warren (2005); Phillips & Smith (1999) |

| Teacher provides sufficient opportunities for students to engage in authentic literacy activities (in student’s first language); with ample opportunities to practice and apply learning | Alton Lee & Nuthall (1990); Freedman & Daiute (2001); Nixon & Comber (2006); Squire (1999) |

| Opportunities are provided for students to engage in meaningful literacy-related conversations in English (where English is not their first language) | Met (1999); Nixon & Comber (2006) |

Opportunities are provided for differentiated learning through:

|

Eke & Lee (2004); Freedman & Daiute (2001); Nixon & Comber (2006) |

| Opportunities for peer interactions

Opportunities for co-operative learning Opportunities for reciprocal teaching |

Gillies (2002); Marzano, Pickering, & Pollock (2001); Nuthall (1997);

Palinscar & Brown (1989); Vaughan (2002) |

| Use of appropriate literacy exemplars, models, vignettes (these are aligned with learning goals . . . ) | Ministry of Education (2003, 2006) |

| Students are engaged with a range of appropriate texts (related to goals of learning and student learning needs) | Ministry of Education (2003, 2006) |

| Links between reading and writing are made explicit | Mayo (2000) |

| Provision of a text-rich environment

|

Farstup & Samuels (2002); Freedman & Daiute (2001); Mayo (2000); Ministry of Education (2003, 2006); Wray & Medwell (2001). |

| Quality interactions between teacher and student(s) | Myhill (2006); Quinn (2004); Ward & Dix (2001, 2004) |

| Teacher scaffolding of class discussions (use of prompts, using examples, contrasts, sustained wait time) | Alton-Lee, Diggins, Klenner, Vine, & Dalton (2001); Myhill (2006); Myhill & Warren (2005); Quinn (2004) |

| Teacher “opens up” interactions with students | Myhill (2006); Myhill & Warren (2005); Smith & Higgins (2006) |

High proportion of literacy related talk:

|

Myhill (2006); Myhill & Warren (2005); Quinn (2004) Ward & Dix (2004) |

| Quality interactions between teacher and student(s) | Myhill (2006); Myhill & Warren (2005); Quinn (2004); |

| Teachers draw on their knowledge bases to inform their teaching/interactions: | |

|

Cowie & Bell (1999); Shulman (1987) |

|

Braunger & Lewis (1998); Indrisano & Squire (2000); Ministry of Education (2003, 2006); New London Group (1996) |

|

Black & Wiliam (1998); Cowie & Bell (1999); Phillips, McNaughton, & McDonald (2001) |

| Use of a range of procedures and tools to gather information about students’ literacy learning (assessment) | Ministry of Education (2003, 2006) |

| Feedback is related to learning goals/objectives | Black & Wiliam (1998); Hattie (1999); Marshall & Drummond (2006); Marzano, Pickering, & Pollock (2001) |

| Feedback identifies achievement | Black & Wiliam (1998); Tunstall & Gipps (1996) |

| Feedback identifies “next step” in learning (improvement) and how to take it | Bishop, Berryman, Tiakiwai, & Richardson (2003); Black & Wiliam (1998); Hawe, Dixon, & Watson (2008); Tunstall & Gipps (1996) |

| Students are involved in generating feedback, determining where to go next and the strategies to achieve the next step(s) | Hawe, Dixon, & Watson (2008); Sadler (1989); Tunstall & Gipps (1996) |

| Inclusion of peer assessment opportunities/action | Hawe, Dixon, & Watson (2008); Sadler (1987); Tunstall & Gipps (1996) |

| Inclusion of self-assessment opportunities/action | Hawe, Dixon, & Watson (2008); Tunstall & Gipps (1996) |

| Encouragement of student self-monitoring and selfregulation | Hawe, Dixon, & Watson (2008); Marshall & Drummond (2006); Palinscar & Brown (1989); Xiang (2004) |

| Use of assessment information to inform teaching: planned, interactive approaches | Black & Wiliam (1998); Cowie & Bell (1999) |

| Management practices facilitate learning | Alton-Lee & Nuthall (1992); Kounin (1970) |

| Class literacy time is spent on literacy-related activities | Brophy (2001) |

| Climate of respect | Brophy (2001); Myhill (2006) |

| Inclusive learning environment; development of a learning community | Alton-Lee (2003); Bossert (1979); Brophy (2001); Nuthall (1999) |

| Acknowledgement of diversity/diverse learners (linked to scaffolding) | Brophy (2001); Nuthall (1999) |

| Teacher responsiveness to student learning processes | Brophy (2001); Myhill (2006); Nuthall (1999) |

| Teacher responsiveness to diverse learners, based on knowledge of each student, the student’s pathway of progress, the student’s characteristics as a literacy learner . . . | Alton-Lee (2003); Freedman & Daiute (2001); Nuthall (1999) |

A list of elements based on those in Table 1 was sent to all partners for consideration prior to a meeting. In the main, discussion at the meeting centred on teasing out what each element entailed and the addition of elements identified by the teachers as integral to their literacy practice. Time was also spent grouping “like” elements together and assigning names to the overarching category. A revised list with categories and constituent elements was then compiled and circulated for further comment. Refinements were made in response to feedback and revisions circulated until all partners were satisfied that the critical elements of literacy practice had been identified. The next stage involved translation of the agreed-upon elements into statements of observable behaviour.

Translation of elements of effective literacy practice into behavioural indicators

Four key issues emerged as the elements of literacy practice were translated into statements of observable behaviour. In the first instance, the need to have indicators that were directly observable meant that categories such as teachers’ expectations and teachers’ knowledge of students were not considered for inclusion in the Observation Guide. It was decided these would be best explored through the peer conversations that followed a cycle of teaching, peer observation, and feedback.

Secondly, teachers from both partner schools requested that the academic language used for some elements be adjusted to make ideas more accessible. In addition, they asked for terms that were already part of teachers’ professional and literacy language to be incorporated into the behavioural statements.

Thirdly, it is noted in the literature that attempts to capture elements of teacher behaviour in statements of observable practice often result in overly technicist and prescriptive statements (Calderhead & Shorrock, 1997; Reynolds & Salters, 1995; Wolf, 1995) that trivialise and fragment practice. At the other extreme, statements of observable practice can be so nebulous they fall foul of Scriven’s (1996) “swamp of vagueness” and as a result can be interpreted in multiple ways. Sadler (1987) has argued, however, that verbal descriptions are always to some degree vague or fuzzy. Rather than attempting to make them sharper through the language used (a solution that may not be possible given the nature of language—see, for example, Marshall, 2004; Sadler, 1987) their fuzziness can be offset, to some degree, by the use of exemplars which illustrate key aspects of the behaviour in question. Moreover, descriptions of behaviour have their interpretation circumscribed, more or less adequately, over time, through usage-in-context (Sadler, 1987).

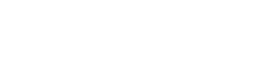

Once the verbal descriptions had been developed, attention turned to the layout of the Guide and how observations would be recorded, that is, the type(s) of scales to use. In some cases such as 1.3 (Figure 1) and 2.7 (Figure 2), a continuous descriptive rating scale (Linn & Gronlund, 1995) was created where each point on the scale was identified through a brief verbal statement.

Figure 1 Appropriateness of time spent

Figure 2 Degree of alignment

| 2.7 Degree of alignment between class activity and learning aim / success criteria | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| No alignment | Tenuous alignment | Reasonable alignment | Strong alignment |

In the majority of cases however the “rating scale” consisted of four or five points with each point defined by a set of brief statements or verbal descriptions. In several instances, as illustrated in 1.1 (Figure 3), although it was likely that the points on the scale were underpinned by an asymtopic continuum, the intention was to treat them as discrete entities.

Figure 3 Presence and quality of learning

| 1.1 Presence and quality of learning aim and success criteria | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1.1.1 No learning aim expressed |

1.1.2 Learning aim implicit in teaching / learning activities |

1.1.3 Learning aim expressed either: in general terms □ as a topic □ as a task □ |

1.1.4 Learning aim expressed as a specific cognitive process or skill |

In other instances, such as 3.2 (Figure 4), while the points on the “scale” had the appearance of being discrete, it was intended that more than one point could be “met” during an observation.

Figure 4 Quality of improvement

| 3.2 Quality of improvement related feedback | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3.2.1 Teacher provides feedback regarding aspects to improve but these are not related to the success criteria, learning aim or generic aspects of literacy learning | 3.2.2 Teacher’s feedback about areas for improvement refers in a general manner to:

|

3.2.3 Teacher tells the learner about what needs to be improved, with reference to:

|

3.2.4 Teacher tells the learner about how to improve their work, with reference to:

|

3.2.5 Learner and teacher discuss (with learner ‘taking the lead’) what needs improvement and how to go about this, with reference to:

|

Users of the Guide were to be alerted to these differences in scale and how to apply them, during training sessions. Provision was made for observers to record evidence related to their ratings in the right-hand side of the Guide sheet.

Developing exemplars of literacy practice

Once an initial draft of the Observation Guide was constructed, it was sent to the partner schools for feedback. During a meeting involving all partners, it was agreed that the development process and later training in the use of the Guide would be enhanced if those involved had access to instances of “typical” literacy practice in a concrete format, that is, in the form of exemplars. To this end, three of the teachers offered to be videoed, “fly-on-the-wall” style[2], as they taught a series of “typical” reading and written language lessons.

Video-taping of the teachers’ practice resulted in production of over 15 hours of unedited tapes. At this stage one of the teachers withdrew from the project and all data traceable to her including video-taped lessons of her junior class were removed. As a result valuable footage that had ensured coverage in terms of diversity of class level and teacher practice was lost. Permission had been given by the remaining two teachers for use of the videos (both the unedited and shorter versions) to train teachers in the use of the Guide and to establish inter-rater reliability when making practice-related judgements. These lessons were initially viewed in their entirety by the researchers to determine whether the critical teacher moves evident in these literacy lessons had been captured in the Guide. At the same time, extracts suitable for editing into shorter exemplars of practice (15–20 minutes each) were identified[3]. These exemplars highlighted a number of typical pedagogical and literacy-related practices such as the development of students’ understanding of learning intentions, the modelling of specific literacy skills, and making links to students’ prior literacy experiences.

Five exemplars were initially created and sent to teachers from the two schools who independently viewed the videos, then re-viewed them using the Guide to record their observations. The researchers undertook the same exercise. Meetings were then held with each partner school to discuss how the Guide had worked. Areas of strength and areas needing further development were identified. The researchers incorporated feedback from each school and from their own appraisal into a revised version of the Guide.

Trial of the Guide with exemplars

Once the revised version was developed, two teachers from Newmarket School and one from Mangere Central agreed to participate in an exercise to determine levels of agreement between independent observers when using the Guide to observe two of the video-taped lessons. The exercise aimed to highlight areas of teachers’ literacy practice in the Guide where the teacherobservers readily reached agreement and those where there was a significant amount of disagreement. Overall, results showed 61 percent agreement among the three observers for the first lesson and 51 percent for the second lesson. Data were analysed according to each of the sub-categories on the Guide so specific areas of agreement or disagreement could be highlighted. Table 2 summarises the percentage of observer agreement over the three observations of two lessons, according to the sub-categories in the Guide.

Table 2 Observer agreement when using the Guide to record judgements while watching video exemplars of practice

1.1 Presence and quality of learning aim & success criteria913.1Quality of achievement-related feedback33

| Observation Guide categories and sub-categories | Percentage agreement |

|

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Learning aim and success criteria | |

| 1.2 | Developing students’ understanding of learning aim and success criteria | 100 |

| 1.3 | Appropriateness of time spent on learning aim/success criteria given significance | 50 |

| 2 | Learning/teaching activities | |

| 2.1 | Relationship between teacher modelling and learning aim/success criteria | 83 |

| 2.2 | Link(s) made to students’ prior knowledge/understanding to support current learning | 33 |

| 2.3 | Deliberate acts of teaching | 33 |

| 2.4 | Teacher interactions with students | 63 |

| 2.5 | Extent of teacher and student engagement in learning-related talk | 75 |

| 2.6 | Overall appropriateness of lesson pace | 100 |

| 2.7 | Degree of alignment between class activity and learning aim/success criteria | 66 |

| 2.8 | Degree of alignment between learning purpose and group activity | 8 |

| 2.9 | Evidence of differentiation | 50 |

| 2.10 | Overall appropriateness of lesson pace | 83 |

| 3 | Feedback about students’ productive activity during reading and/or writing | |

| 3.2 | Quality of improvement-related feedback | 50 |

| 3.3 | Self-regulating prompts | 83 |

| 3.4 | Opportunities for quality peer assessment | 33 |

| 3.5 | Opportunities for quality self-assessment | 66 |

The teachers involved in this exercise met with members from the university team to discuss the findings with particular attention given to areas where there was less than 70 percent observer agreement. Once again, feedback was incorporated into a further iteration of the Guide.

Feedback from experts

When the Observation Guide was near its final form, it was sent to three literacy experts for one last set of feedback. The basis for this feedback differed as each person was asked to review and/or trial the Guide and the short videoed exemplars with specific reference to their area(s) of expertise and experience. The first of these experts, an author of numerous literacy guides for teachers in New Zealand schools, gave feedback in relation to her use of the Guide to record observations drawn from the video-taped exemplars. The second expert, an experienced teacher and literacy facilitator, provided feedback in terms of how the categories and elements included in the Guide related to classroom settings she worked in. The third expert, an accomplished teacher and senior manager with school-wide responsibility for and expertise in literacy, first reacted to the Guide then provided information based on her “real-time” use of it when observing literacy lessons at her school. Feedback from these experts was incorporated into the eleventh version of the Guide (see Appendix 1). This version was used in phase two of the study.

Phase two (2007)

Phase two was conducted at Berkley Normal Middle School, a decile 9 state school in Hamilton. This phase involved all of the teachers at the school in a year-long trial of the Observation Guide under the guidance of the school’s literacy leader, Wendy Foster, in association with Judy Parr and Eleanor Hawe from the University of Auckland.

Using the Observation Guide to observe and make qualitative judgements about teachers’ literacy practice

Staff at Berkley Normal Middle School used the Guide from February to October as the focus for making qualitative judgements about teachers’ literacy practice during seven cycles of literacy teaching, peer observation, and feedback. The frailty of observers’ or appraisers’ qualitative judgements has been well documented in the literature with the majority of concerns centred on issues of reliability and bias (Koretz, Stecher, Klein, & McCaffrey, 1994; Linn, 1994; Mullis, 1984; Sadler, 1986). Such judgements can however be made more dependable when points of reference for making judgements are developed and disseminated in appropriate forms—in the case of this project, the Observation Guide—and when observers or appraisers are given relevant conceptual tools such as exemplars, and practical training (Sadler, 1987). The latter was provided through professional learning sessions (of 80–90 minutes’ duration) held with staff, prior to the beginning of each cycle. During these sessions staff members were introduced to the section of the Guide that was the focus of the upcoming cycle. In addition, video-based exemplars of practice were used where appropriate, and professional readings of relevance to the focus area provided. The aims of these sessions were to develop shared understandings regarding the verbal descriptions used in the Guide, become familiar with protocols for use, and address implementation issues.

To illustrate, the first of these training sessions centred on Section 1 of the Observation Guide (1.1; 1.2; 1.3) and on parts of Section 2 (2.1; 2.2; 2.3)—all of these were related to the use of literacy learning intentions and success criteria (see Appendix 1). As learning intentions and success criteria were an established part of teachers’ practice at this school, it was anticipated that staff members would have a reasonably sound and shared understanding about what these entailed and how they “played out” in a literacy context. Prior to the meeting, all teachers had been given a short extract to read about learning intentions and success criteria (Absolum, 2006). Each section of the Guide (1.1–2.3) was examined in turn at the meeting with reference to specific points raised in the extract. In addition, literacy-based examples were used to illustrate what each category “looked like” in practice. Interestingly, much time was spent discussing two of the statements included in 1.1: that the learning aim is “expressed as a specific cognitive process or skill” and that success criteria “include a standard or progressions/levels of achievement in relation to each element or property of the learning”. With reference to the first of these statements, staff members were unsure what was meant by “specific cognitive process or skill” and asked for examples related to their current literacy programme. This resulted in an impromptu appraisal of learning intentions in the current programme. Discussion regarding the second statement indicated that, in the main, teachers at the school broke each learning intention into a number of constituent elements and each of these elements had a single success criterion attached to it, often expressed in terms of presence or absence or number of instances (for discussion of this practice see Hawe, Dixon, & Watson, 2008). Teachers did not seem to be familiar with expressing success criteria as progressions/levels of achievement and the inclusion of an explicit standard, so some time was spent considering the rationale underlying these practices and providing illustrations.

Once the initial sections of the Guide had been introduced, staff watched one of the video exemplars where a teacher established with her class the learning intention and success criteria for a series of writing lessons. Rather than illustrating “best practice”, this exemplar depicted slippage in the alignment of the learning intention, success criteria, and what was modelled. As they watched the extract for a second time, staff used the Observation Guide (Sections 1.1; 1.2; 1.3; 2.1; 2.2) to make judgements about the teacher’s practice. These judgements were then discussed, firstly in small groups then together. Reported variations in observer judgements generated further discussion about the verbal descriptions in the Guide and the evidence observed in the video.

Additional training regarding Sections 1.1–2.2 occurred without input from the university personnel as the teachers used the Guide in “real time” during their peer observation and feedback sessions and as they discussed issues with colleagues. Remaining areas of the Guide were introduced to staff in a similar fashion prior to the commencement of each new cycle of peer observation and feedback.

Changes to the Guide

No changes were made to the Observation Guide during the first four cycles as the teachers needed time to become familiar with it. Two requests for change emerged however during the introductory session for cycle five where the focus was on “Feedback about students’ productive activity during reading and/or writing”. In the first instance, teachers sought clarification regarding some of the verbal descriptions. The section related to self-regulating prompts, for instance, included four elements (Figure 5):

Figure 5 Self-regulating prompts

| 3.3 Self-regulating prompts | Oral □ | Written □ | N/A□ |

|---|---|---|---|

| The teacher reminds learners to evaluate / check their work | The teacher reminds learners to evaluate / check their work with reference to:

|

The teacher provides students with evaluative self-regulating prompts related to:

|

The teacher specifically refers students to evaluative selfregulating prompts related to:

|

During discussion, it emerged that teachers felt the distinctions between these four categories was somewhat “forced” and they made suggestions about how these could be reduced to three quite distinct categories, more reflective of practice (Figure 6):

Figure 6 More Self-regulating prompts

| 3.3 Self-regulating prompts | Oral □ | Written □ |

|---|---|---|

| 3.3.1 The teacher reminds learners to evaluate / check their work | 3.3.2 The teacher specifically provides learners with / refers learner(s) to, evaluative selfregulating prompts related to:

|

3.3.3 Learner(s) spontaneously refer to / use self-regulating prompts |

Secondly, it was suggested that a fifth element be included in both 3.1 and 3.2 to incorporate D2 types of feedback. D2 feedback that “constructs learning” and “constructs the way forward” (Tunstall & Gipps, 1996) has been identified in the literature as important in terms of supporting and enhancing students’ learning and developing “intelligent self-monitoring” (Sadler, 1989). Staff had been given a pre-publication copy of a New Zealand study (Hawe, Dixon, & Watson, 2008) regarding the use of different types of feedback in written language and, as a result, some argued strongly for the inclusion of D2 types of feedback in the Guide on the basis that it would encourage teachers to consider and incorporate such practices into their repertoire. As a consequence, the following were added to 3.1 and 3.2 (Figure 7):

Figure 7 Quality of achievement-related feedback and improvement-related feedback

| 3.1 Quality of achievement related feedback: 3.1.5 Learner and teacher discuss (with learner ‘taking the lead’) whether and how the work has met/has not met:

|

|

| 3.2 Quality of improvement related feedback 3.2.5 Learner and teacher discuss (with learner ‘taking the lead’) what needs improvement and how to go about this, with reference to:

|

A structural change was also made to Section 3 of the Guide, shifting the column for recording evidence in support of judgements from the right-hand side of the sheet to directly underneath each of the elements. This change was made because teachers reported it was often difficult to determine which category and/or elements the observer’s comments recorded down the right-hand side of the Guide related to. Staff decided that having space for recording evidence directly below each element would make the links more obvious. Figure 8 illustrates the change:

Figure 8 Quality of achievement-related feedback

| 3.1 Quality of achievement related feedback | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3.1.1 Teacher’s feedback is not directly related to achievement (rather it is approving, rewarding, disapproving of behaviour) | 3.1.2 Teacher’s feedback refers in a general manner to:

|

3.1.3 Teacher tells the learner about whether their work has met/has not met:

|

3.1.4 Teacher tells the learner about how their work has met/has not met:

|

3.1.5 Learner and teacher discuss (with learner’ taking the lead’) whether and how the work has met/has not met:

|

| Evidence: |

|

|||

The amended version of Section 3 (see Appendix 2) was e mailed to staff prior to commencement of the cycle.

Written exemplars

During introduction of the fifth cycle, teachers asked if they could have a written copy of the orally provided examples of feedback practice used to illustrate each of the elements. While staff found the video exemplars useful to help develop understanding of the elements, the written illustrations were more accessible and “transportable”—teachers could have these next to them as a point of reference when observing and/or engaging in learning conversations with their peer. These examples were added under each of the categories (see Appendix 3) and also emailed to staff.

Reliability of teachers’ qualitative judgements

Given that staff had used parts of the Guide for four cycles and they were becoming familiar with the process, and given that considerable time had been spent discussing feedback and the elements on the Guide, it was decided to carry out a short exercise to determine the reliability of teachers’ qualitative judgements using this section of the Guide. Following completion of cycle five, 17 of the teachers viewed a short video exemplar where a teacher and student were engaged in a writing conference and the class was guided through a short peer feedback session. A written transcript was made of the exemplar (to ensure all teacher–student dialogue was picked up) and on a second viewing of the video, staff were asked to refer to the Guide when making and recording judgements in the column provided about the teacher’s practice, using the feedback categories 3.1–3.5, with corresponding evidence highlighted or underlined or recorded on the transcript. Each teacher handed in their annotated transcript once they were satisfied with their judgements.

For the purpose of analysis, two experts divided the transcript into 15 segments and identified 22 instances of feedback, self-/peer assessment and/or self-regulation across these segments (not counting the instance filled in on the sheet to indicate how to annotate the transcript). Judgements made by the teachers were compared with the agreed-upon appraisals from the two experts. Overall, no teacher had more than 50 percent agreement with the experts. Agreement among the 17 teachers as a whole and the experts, on each of the 22 instances, ranged from 0 to 64 percent. In total there were 79 instances of agreement (out of a possible total of 374) between these two groups regarding the nature of the feedback, self-/peer assessment and/or self-regulation observed; 117 instances where teachers identified the occurrence of feedback, self-/peer assessment and/or self-regulation, but their categorisations did not match those of the experts; and 178 instances of feedback, self-/peer assessment and/or self-regulation that teachers missed. Close examination of the full data set and the annotations on the transcripts provided some insights into the 117 instances that were incorrectly categorised. In the majority of cases, these were classified within the same overall category on the Guide; for example, an instance categorised by the experts as 3.2.3 (The teacher tells the learner about what needs to be improved . . . ) was classified by teachers as either 3.2.2 or 3.2.4, indicating that either further familiarisation with the distinctions between these sub-categories was needed and/or the verbal descriptions needed to be revised. Failure to recognise instances of feedback, self-/peer assessment and/or self-regulation and the categorisation of non-examples indicated however that the teachers were not yet secure in their knowledge about the nature of these areas and pointed towards the need for further “serioustalk” (Feiman-Nemser, 2001) around these matters. Overall these findings suggested that recognising examples of feedback, self-/peer assessment and/or self-regulation is not as straightforward as it seems—these areas are acknowledged in the literature as complex and problematic (Black, Harrison, Lee, Marshall & Wiliam, 2003; Torrance & Pryor, 1998: Shepherd, 2000). Moreover, a recent study of New Zealand teachers’ conceptions and use of feedback found that although teachers believed they understood and were practising “feedback for learning”, there was a significant disjuncture between perception and reality (Dixon, 2008). This was alluded to during an interview with one of the Berkley staff when she commented, “We thought we understood about feedback but when it was actually presented to us with all of the readings around it . . . it’s like you keep learning . . . you-don’t-know-what you-don’t-know stuff . . .” (Sarah[4]).

Teachers’ perceptions of the Guide

Teachers’ perceptions regarding the Guide were gathered from a survey carried out near the end of the project and during individual semi-structured interviews with a purposive sample of six teachers.

Survey information

All teachers were asked at the end of October to complete a short survey (see Appendix B4) where they rated on a 6-point scale each of the 11 broad areas of practice on the Guide with reference to their importance (1 = very unimportant; 2 = unimportant; 3 = slightly important; 4 = moderately important; 5 = mostly important; 6 = very important) when observing and providing feedback about teaching practice. No area had a mean ranking below 4.50, indicating that, although some areas of the Guide were considered slightly more important than others, all areas were rated as moderately, mostly, or very important.

Three areas had a mean ranking of 5.40 or above. The degree of alignment between learning intentions, success criteria and class/group activities received the highest average rank (M=5.58) with 75 percent of the respondents rating it as a “very important” aspect of teaching practice to observe and provide feedback about. Quality of achievement- and improvement-related feedback received the second highest mean ranking (M=5.50) with 60 percent rating it as “very important”, while the links between teacher modelling and learning intentions/success criteria was third highest (M=5.40) with 50 percent rating it as “very important”. Observing and providing feedback about deliberate acts of teaching (M=5.35), the nature and quality of learning intentions and success criteria (M=5.30), and teacher/student engagement in learning-related talk (M=5.30) were the next highest ranked areas. Relatively speaking, the three areas of least importance when observing and providing feedback about teaching practice (although ranked on the whole as moderately to mostly important) were the overall appropriateness of lesson pace (M=4.50), the presence and student use of self-regulating prompts (M=4.60), and the inclusion of opportunities for peer and self-assessment (M=5.0).

The survey also asked teachers to rank on a scale of 1–100, the impact on their professional learning of nine areas, one of these areas being use of the Guide to inform observations and feedback. Use of the Guide was ranked seventh (M=40/100) with staff clearly split in their views. Half of the teachers perceived the Guide as having a reasonable impact on their professional learning (M=65/100) while the other half considered it as having relatively little impact (M=12/100). This is discussed further in Part B, Section 3.

Interview information

Four key themes concerning teachers’ use of the Guide emerged from the interviews. The first and most dominant theme related to the role of the Guide in making teachers “more aware” (Katie) of specific aspects of their teaching practice. All teachers made mention of how as a result of using the Guide they gave more attention and thought to developing appropriate learning intentions and success criteria. Marilyn, for example, admitted that until she had seen the Guide she had “never thought of success criteria as . . . progressive levels”, while Cameron indicated that the Guide made him think about whether he provided sufficient opportunities for his students to engage in talk with their peers. Those interviewed noted that their awareness had also been raised about self-regulating prompts, deliberate acts of teaching (DATs) such as modelling, feedback, alignment between activities and learning intentions/success criteria, the provision of differentiated activities, and the promotion of interactions between students.

The second theme related to use of the Guide to focus observations. Claire commented that the Guide “makes it very clear what you are looking for” during peer observations. Without it “we’d be a mess . . . [we’d] wallow around . . . ” (Katie), and “[we] wouldn’t be looking for specific things like ‘deliberate acts of teaching’ . . . ” (Roger). All of those interviewed referred to how the Guide had provided them with a focal point for observation of their peer’s teaching and the provision of feedback.

The third theme related to the hierarchical way in which some of the statements on the Guide were organised. This organisation was interpreted by some as providing information about the gap between current and desired performance, giving them a goal to work towards:

. . . well I’m actually here and I need to be aiming for that and so it gives you feedback . . . where you are and where you should be aiming for and you could be aiming for and so its refined your teaching . . . (Katie)

Others however felt pressured to achieve at the top level and felt as though they had failed if they were not judged as having reached this level during their observed lesson.

. . . almost like a continuum, even though you never said that you need to be in the top box, everybody felt like they should be . . . I felt, ‘Oh gosh, that was bad because I didn’t get [the] top box. (Marilyn)

The final theme concerned the types of support needed to help teachers “make sense” of the Guide. Roger stated that:

If you just chucked us the entire schedule [Guide] and said, ‘Right, go and do an observation’, you’d probably have half or three-quarters of the staff going, ‘What on earth is going on? How do you do it?

Use of written illustrations of practice, video exemplars, and opportunities for teachers to discuss issues in teams or as a staff were considered critical to the success of the Guide. Half of those interviewed indicated that they would have liked to see more video-taped exemplars of practice (not necessarily “best practice”) and to have access to written illustrations of practice as a quick point of reference. Although using the Guide was acknowledged as at times “really hard” (Katie), it was noted that the “more you use it the easier it becomes” (Carol). Teachers observed that their understanding of categories included in the Guide and the protocols associated with use developed over time with practice. This was however a double-edged sword as the more the teachers used the Guide, the more they realised they had some quite significant “gaps” in their own knowledge about the elements of effective [literacy] teaching practice.

As she reflected on her experiences and those of her colleagues, Sarah recognised that “you need a lot of knowledge [about the elements of effective literacy practice] . . . [and] there [is still] a lot more learning . . . to do”. For Hakeem, working with the Guide to inform peer observation and feedback in written language made “ . . . us look critically at the way we’re teaching writing . . . it’s been a challenge, I can see benefits in my teaching”, while Mary indicated that “it was the fine tuning that’s going on with your practice and that’s what I take from it: What am I doing? Who am I doing this for? What are my next steps in moving them [students] forward?” The Observation Guide clearly made the teachers more aware of specific aspects of effective literacy teaching practice, gave them a point of reference when observing their peer’s teaching and providing feedback, and indicated the next step(s) to be taken in the development of their teaching practice.

Revision of the Observation Guide

On the basis of feedback generated during phase two of the project, the Observation Guide was reviewed and revised. The revised Guide (Appendix A4) contains four sections:

- literacy learning goals and expectations about what counts as successful achievement of these goals

- curricula alignment

- teacher interactions, and differentiation for learners and learning

- feedback about productive activity, peers and self feedback and self-regulation during literacy learning.

It is not intended that the revised Guide address every element of teachers’ literacy practice; rather, it includes those that were considered and/or emerged as central to successful practice. Each section contains no more than five areas for observation, enabling a more focused approach by the teacher being observed and the peer observer, and verbal descriptions have been refined so the distinctions between areas are more clear-cut. In addition, recording has been made more manageable by including spaces for the recording of evidence under or alongside each area and having only one or two pages for each section. Use of the Revised Guide will enable teachers to “gather rich descriptions of practice, attention to evidence, examination of alternative interpretations, and possibilities” and “over time . . . develop a stronger sense of themselves as practical intellectuals, contributing members of the profession, and participants in the improvement of teaching and learning” (Feiman-Nemser, 2001, p. 1043).

References (Part A)

Absolum, M. (2006). Clarity in the classroom: Using formative assessment: Building learning focused relationships. Auckland: Hodder Education.

Alton-Lee, A. (2003). Quality teaching for diverse students in schooling: Best evidence synthesis. Wellington: Ministry of Education.

Alton-Lee, A., Diggins, C., Klenner, L., Vine, E., & Dalton, N. (2001). Teacher management of the learning environment during a social studies discussion in a new-entrant classroom in New Zealand. The Elementary School Journal, 101(5), 549–566.

Alton-Lee, A, & Nuthall, G. (1990). Pupil experiences and pupil learning in the elementary school: An illustration of a generative methodology. Teaching and Teacher Education: An International Journal of Research & Studies, 6(1), 27–46.

Alton-Lee, A., & Nuthall, G. (1992). Students’ learning in classrooms: Curricular, instructional and socio-cultural processes influencing student interaction with classroom content. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Educational Research Association, San Francisco.

Alton-Lee, A., & Nuthall, G. (1998). Inclusive instructional design: Theoretical principles emerging from the Understanding Learning and Teaching Project: Report to the Ministry of Education. Wellington: Ministry of Education.

Biggs, J. (1999). What the student does: Teaching for enhanced learning. Higher Education Research and Development, 181, 57–75.

Bishop, R., Berryman, M., Tiakiwai, S., & Richardson, C. (2003). Te Kötahitanga: The experiences of year 9 and year 10 Maori students in mainstream classrooms. Wellington: Ministry of Education.

Black, P., Harrison, C., Lee, C., Marshall, B., & Wiliam, D. (2003). Assessment for learning: Putting it into practice. Maidenhead: Open University Press.

Black, P., & Wiliam, D. (1998). Assessment and classroom learning. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy and Practice, 5(1), 7–74.

Bossert, S. (1979). Tasks and social relationships in classrooms: A study of instructional organisation and its consequences. London: Cambridge University Press.

Braunger, J., & Lewis, J. P. (1998). Building a knowledge base in reading (2nd ed). Newark, DE.: International Reading Association.

Brophy, J. (2001). (Ed). Subject-specific instructional methods and activities. Advances in Research on Teaching, Vol. 8. New York: Elsevier.

Burstein, L., McDonnell, L. M., Van Winkle, J., Ormseth, T., Mirocha, J., & Guitton, G. (1995). Validating national curriculum indicators. Santa Monica, CA: RAND.

Calderhead, J., & Shorrock, S.B. (1997). Understanding teacher education. London: Falmer Press.

Clarke, S. (2005). Formative assessment in action: Weaving the elements together. London: Hodder Murray.

Clay, M. (1979). Reading: The patterning of complex behaviour. Auckland: Heinemann.

Cowie, B., & Bell, B. (1999). A model of formative assessment in science education. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 6(1), 101–116.

Crooks, T. J. (1988). The impact of classroom evaluation practices on students. Review of Educational Research, 58(4), 438–481.

Dixon, H. (2008). Feedback for learning: Deconstructing teachers’ conceptions and use of feedback. Unpublished doctoral thesis, University of Auckland.

Eke, R., & Lee, J. (2004). Pace and differentiation in the literacy hour: Some outcomes of an analysis of transcripts. The Curriculum Journal, 15(3), 219–231.

Farstup, A. E., & Samuels, S. J. (Eds) (2002). What research has to say about reading instruction (3rd ed). Newark, DE.: International Reading Association.

Feiman-Nemser, S. (2001). From preparation to practice: Designing a continuum to strengthen and sustain teaching. Teachers College Record, 103(6), 1013–1055.

Freedman, S. W., & Daiute, C. (2001). Instructional methods and learning activities in teaching writing. In J. Brophy (Ed). Subject-specific instructional methods and activities. Advances in Research on Teaching, Vol. 8. New York: Elsevier.

Gillies, R. M. (2002). The residual effects of co-operative learning experiences: A 2 year follow up. The Journal of Educational Research, 96(1), 15–20.

Hattie, J. (1999, April). Influences on student learning. Inaugural lecture, University of Auckland.

Hawe, E., Dixon, H., & Watson, E. (2008). Oral feedback in the context of written language. Australian Journal of Language and Literacy, 31(1), 43–58.

Henk, W., Marinak, B. A., Moore, J. C., & Mallette, M. H. (2003). The writing observation framework: A guide for refining and validating writing instruction. The Reading Teacher, 57(4), 322–333.

Hoffman, J. V., Sailors, M., Duffy, G. R., & Beretvas, S. N. (2004). The effective elementary classroom literacy environment: Examining the validity of the TEX-IN3 observation system. Journal of Literacy Research, 36(3), 303–334.

Indrisano, R., & Squire, J. R. (Eds). (2000). Perspectives on writing: Research, theory and practice. Newark, DE.: International Reading Association.

Junker, B., Matsumara, L., Crosson, A., Wolf, M., Levison, A., Weisberg, Y., & Resnick, L. (2004, April). Overview of the instructional quality assessment. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Educational Research Association, San Diego.

Koretz, D., Stecher, B. M., Klein, S. P., & McCaffrey, D. (1994). The Vermont portfolio assessment program: Findings and implications. Educational Measurement: Issues & Practice, 13, 5–16.

Kounin, J. S. (1970). Discipline and group management in classrooms. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston.

Linn, R. L. (1994). Performance assessment: Policy promises and technical measurement standards. Educational Researcher, 23, 4–14.

Linn, R. L., & Gronlund, N. E. (1995). Measurement and assessment in teaching (8th ed.). New Jersey: Prentice Hall.

Luke, A., Matters, G., Herschell, P., Grace, N., Barrett, R., & Land, R. (2000). New Basics project: Technical Paper. Queensland: Educational Queensland.

Marshall, B. (2004). Goals or horizons – the conundrum of progression in English: Or a possible way of understanding formative assessment in English. The Curriculum Journal, 15(2), 101–113.

Marshall, B., & Drummond, M. J. (2006). How teachers engage with Assessment for Learning: Lessons from the classroom. Research Papers in Education, 21(2), 133–150.

Marzano, R., Pickering, D., & Pollock, J. (2001). Classroom instruction that works: Research-based strategies for increasing student achievement. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Mayo, L. (2000). Making the connection: Reading and writing together. English Journal, 89(4), 74–77.

McDonald, G. (1993). Learning to be intelligent or Oh good, that was clever!: Teaching how to think. set: Research Information for Teachers, 2, item 2..

Met, M. (1999). Foreign language. In G. Cawelti (Ed). Handbook on research on improving student achievement (2nd ed.). Arlington, VA: Educational Research Services.

Ministry of Education (2003). Effective literacy practice in years 1 to 4. Wellington: Learning Media.

Ministry of Education (2006). Effective literacy practice in years 5 to 8. Wellington: Learning Media.

Mullis, I. V. S. (1984). Scoring direct writing assessment: What are the alternatives? Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice, 3, 16–18.

Myhill, D. (2006). Talk, talk, talk: Teaching and learning in whole class discourse. Research Papers in Education, 21(1), 19–41.

Myhill, D., & Warren, P. (2005). Scaffolds or straightjackets? Critical moments in classroom discourse. Educational Review, 57(1), 55–69.

New London Group (1996). A pedagogy of multiliteracies: Designing social futures. Harvard Education Review, 66(1), 60–92.

Nixon, H., & Comber, B. (2006). Differential recognition of children’s cultural practices in middle primary literacy classrooms. Literacy, 40(3), 127–136.

Nuthall, G. (1997). Understanding student thinking and learning in the classroom. In B. Biddle, T. Good & I. Goodson (Eds). International handbook of teachers and teaching, Vol.2, 681–768.

Nuthall, G. (1999). Learning how to learn. The evolution of students’ minds through the social processes and culture of the classroom. International Journal of Educational Research, 31(3), 139256.

Palinscar, A. S., & Brown, A. L. (1989). Classroom dialogue to promote self-regulated comprehension. In J. Brophy (Ed). Advances in Research on Teaching, Vol.1, 35–71.

Phillips, G., & Smith, P. (1999). Achieving literacy for the hardest-to-teach: A third chance to learn. set: Research Information for Teachers, 1, item 11.

Phillips, G., McNaughton, S., & McDonald, S. (2001). Picking up the pace: Effective literacy intervention for accelerated progress over the transition into decile 1 schools: Final Report to the Ministry of Education. Auckland: The Child Literacy Foundation and the Woolf Fisher Research Centre.

Quinn, M. (2004). Talking with Jess: Looking at how meta-language assisted explanation writing in the middle years. Australian Journal of Language and Literacy, 27(3), 245–261.

Reynolds, M., & Salters, M. (1995). Models of competence and teacher training. Cambridge Journal of Education, 25, 349–359.

Sadler, R. D. (1986). Subjectivity, objectivity and teachers’ qualitative judgements. Assessment Unit Discussions Paper 5. Brisbane: Board of Secondary School Studies.

Sadler, D. R. (1987). Specifying and promulgating achievement standards. Oxford Review of Education, 13, 191–209.

Sadler, D.R. (1989). Formative assessment and the design of instructional systems. Instructional Science, 18, 119–144.

Sawada, D., Piburn, M. D., Judson, E., Turley, J., Falconer, K., Benford, R., & Bloom, I. (2002). Measuring reform practices in science and mathematics: The reformed teaching observation protocol. School Science and Mathematics, 102, 245–253.

Scriven, M. (1996). Assessment in teacher education: Getting clear on the concept. An essay review. Teaching and Teacher Education, 12, 443–450.

Shepherd, L. (2000). The role of assessment in a learning culture. Educational Researcher, 29(7), 4–14.

Shulman, L. (1987). Knowledge and teaching: Foundations of the new reform. Harvard Educational Review, 57, 1–22.

Smith, H., & Higgins, S. (2006). Opening classroom interaction: The importance of feedback. Cambridge Journal of Education, 36(4), 485–502.

Squire, J. R. (1999). Language arts. In G. Cawelti (Ed). Handbook on research on improving student achievement (2nd ed.). Arlington, VA: Educational Research Services.

Stigler, J. W., Gonzales, P., Kawanaka, T., Knoll, S., & Serrano, A. (1999). The TIMMS videotape classroom study: Methods and findings from an exploratory research project on eighth-grade mathematics instruction in Germany, Japan, and the United States. A Research and Development Report. Washington, DC: United States Office of Educational Research and Improvement, Department of Education.

Torrance, H., & Pryor, J. (1998). Investigating formative assessment: Teaching, learning and assessment in the classroom. Buckingham: Open University Press.

Tunstall, P., & Gipps, C. (1996). Teacher feedback to young children in formative assessment: A typology. British Educational Research Journal, 22(4), 389–404.

Vaughan, W. (2002). Effects of co-operative learning on achievement and attitude among students of colour. The Journal of Educational Research, 25(6), 359–364.

Walberg, H. (1999). Generic practices. In G. Cawelti (Ed). Handbook on research on improving student achievement (2nd ed.). Arlington, VA: Educational Research Services.

Ward, R., & Dix, S. (2001). Support for the reluctant writer. Teachers and Curriculum, 5, 68–71.

Ward, R., & Dix, S. (2004). Highlighting children’s awareness of their texts through talk. set: Research Information for Teachers, 1, 7–11.

Wolf, A. (1995). Competence-based assessment. Buckingham: Open University Press.

Wray, D. & Medwell, J. (2001). Teaching literacy effectively: Contexts and connections. London: Routledge Falmer

Xiang, W. (2004). Encouraging self-monitoring in writing by Chinese students. ELT Journal, 58(3), 238–246.

Part B: Reciprocal peer observation and discussion as a form of professional learning

Judy Parr and Eleanor Hawe

The University of Auckland

with Wendy Foster and her colleagues from Berkley Normal Middle School, Hamilton

1. Placing the peer observation and discussion study in context

With an increasing focus internationally on enhancing the quality of teaching in order to raise student achievement, the ongoing professional learning of teachers is a significant topic. Teacher learning can be seen as the “construction of cognition by individual teachers in response to their participation in the experiences provided by the professional development trajectory and through their participation in the classroom (Clarke & Hollingsworth, 2002, p. 995). Professional growth is complex; there are multiple patterns of learning and learning is ongoing, and the need is to understand the complex processes by which learning is created and shared (Gravani, 2007).

There is limited evidence that traditional delivery models of professional development have a positive impact on teaching quality or student learning (Timperley & Alton-Lee, 2008). Delivery models fail to bridge the theory–practice divide for the participating teachers and have been shown to create a climate unfavourable to professional learning (Gravani, 2007). A model more linked to classroom practice is one where particular teaching practices, established from research into teaching and learning to be effective in enhancing student learning and achievement, are prescribed. A professional developer takes the key skills implicated in these practices, teaches them to the teachers, and ensures their implementation. Initiatives using such a model report relatively small effects on student achievement (Borman et al., 2005; Kerman et al., 1980; Rowan & Miller, 2007). Any gains are often not sustained once the professional developers leave (Datnow, Borman, Stringfield, Overman, & Castellano, 2003; Robbins & Wolfe, 1987; Stallings & Krasavage, 1986). This varied and limited impact, together with the lack of sustainability, is not surprising given the deprofessionalising nature of this type of approach (Timperley & Parr, 2008).

Alternative approaches to teacher professional learning focus on facilitating the development of teacher reflection and collaborative inquiry (e.g., Butler, Lauscher, Jarvis-Selinger, & Beckingham, 2004; Doyle, 1990; Kohler, Ezell, & Paluselli, 1999). Models of improving professional learning and practice like that of Glazer and Hannafin (2006) cultivate reciprocity within teaching communities situated in school environments. Their model draws on a rich theoretical base of collaboration and situated professional learning and an extensive literature about reciprocal interactions among teachers within communities, together with an analysis of phases and roles demonstrated to promote collaboration. The role of the professional developer/facilitator/coach in these situations is to promote reflection. The link to improvement in outcomes for students, however, is weak. In other literature, including both detailed case descriptions (e.g. Lipman, 1997; Morton, 2005; Rousseau, 2004; Saxe, Gearhart, & Nasir, 2001) and a recent meta-analysis by Rowan & Miller (2007), changes in practice that relate to improved student outcomes, resulting from participating in such communities, are not often evident.

The current study draws on the notion of cultivating reciprocity. Professional learning is situated within the professional development trajectory often broadly termed peer coaching, a type of professional development where teachers work together, engaging in guided activities to support each other’s professional growth (Ackland, 1991; Joyce & Showers, 1995). This model of professional development employing coaching and peers was partly a response to the widespread finding that few teachers implemented what they had learnt from the traditional delivery model of professional development that focused on teaching strategies and curriculum (Showers & Joyce, 1996). In a series of studies, Showers and Joyce showed that regular seminars or coaching sessions, focused on classroom implementation and the analysis of teaching (especially of student response), enabled teachers to practice and implement the content they were learning and implementation rose dramatically. Their approach involved modelling, practice under simulated conditions, and practice in the classrooms. The coaching followed initial training to assist in the transfer of the skill. The coach, in this case, was an outside consultant or a more expert peer (Joyce & Showers, 1980; Showers, 1982, 1984). However, a significant finding was that teachers, introduced to new models in terms of teaching strategies, could coach one another provided they received follow-up in training settings.

There are various forms of peer coaching; they tend to fall into three general categories, according to Wong and Nicotera (2003). Technical and team coaching focus on providing support to implement innovations in curriculum and instruction, while collegial and cognitive coaching aim at improving existing practice through developing collegiality, increasing professional dialogue and assisting teachers to reflect on their teaching (Ackland, 1991; Joyce & Showers, 2002). The third category is challenge coaching which is employed in the context of identifying and treating a specific problem. The strategies differ across categories but all intend that peers help one another improve the teaching and learning process.

Facilitated collegial interaction, such as in the form of peer coaching, provides teachers with the opportunity to engage in experimentation, observation, reflection, exchange of professional ideas and shared problem solving in an integrated form (Zwart, Wubbels, Bergen, & Bolhuis, 2007). Peer coaching centrally involves observation of practice. Observing teachers’ classroom practice, analysing the lesson, and providing feedback is often cited as a central feature of promoting professional learning that results in improved learning for students (e.g., Adey, 2004; Veenman, Denessen, Gerrits, & Kenter, 2001). The particular advantage of observing classroom practice and providing feedback is the direct embedding of the interactions in the context of teachers’ daily work, a key tenet of effective professional development. Peer coaching takes place in the workplace where there are numerous opportunities for learning—some are planned, but other opportunities happen spontaneously.

In this study of reciprocal peer observation and discussion, where teachers in a dyad each take turns in the roles of observed and observer, observations by a peer with accompanying discussions were a planned professional learning activity. The observations were guided and the subsequent discussion process facilitated by training. The strength of this type of peer observation with focused feedback is that “the purpose is mutual professional development and not an examination of professional competence” (Smith, 2003, p. 213).

Opportunities to learn potentially could arise from seeing, for example, a colleague perform a skill that the observer may find to be difficult or threatening, with the result that the observer may be more likely to believe that s/he can do it (Licklider, 1995) or from watching one another work with students and thinking together about the impact of teacher behaviours on student learning (Joyce & Showers, 1995). Opportunities to learn could come from both providing and receiving feedback about observed lessons (Pressick-Kilborn & te Riele, 2008). Although feedback would seem to be central to a coaching process, there is some debate about the role of feedback. Some maintain feedback in peer coaching is too like supervision and that it weakens collaboration (Showers & Joyce, 1996) and that the focus should be on planning and developing instruction. Sustained professional learning is seen to require ongoing participation in professional conversations (e.g., Feiman-Nemser, 2001), typically associated with communities of practice (Wenger, 1998).

Such conversations assist teachers and similar professionals negotiate their understandings of practice. Understandings may arise through the process of reflection (Bullough & Pinnegar, 2001). Some advocates emphasise the fact that the conversations are “cognitively and emotionally nourishing for our practice as well as being significant personally and professionally” (Schuck, Aubusson, & Buchanan, 2008, p. 216) and emphasise the notion of reflective self-study supported by critical friends (e.g., Loughran, 2002). Others emphasise the potential of such conversations for learning through dissonance and challenge in order to promote change towards more effective practice (Annan, Robinson, & Lai, 2003; Timperley, 2003).

In professional interchanges there are a number of features that may support the interchange, including mutual respect, a climate of risk taking, and a shared desire to improve (Bereiter & Scardamalia, 1993; Wenger, 1998). Peer observation, as a means of breaking down the isolation of the act of teaching, may be associated with the openness and shared sense of responsibility required for a true professional community to operate. In peer observation, issues of shared (or separate) understandings can arise (Schuck & Russell, 2005; Schuck & Segal, 2002). Particularly important to address is obtaining a shared understanding of what constitutes quality practice.

There are particular considerations in setting up peer observation and discussion given that it is likely that teachers hold different views of what comprises an effective teaching style. Studies show that practices consistent with what the peer (reviewer in this case) did or would do were evaluated positively and those which the peer reviewer would not engage in were typically evaluated negatively (Quinlan, 2002). One’s perspectives on teaching form the basis for normative roles and expectations regarding acceptable forms of teaching (Pratt & Associates, 1998) and these, for example, may operate in peer observations. Both focused formats to use to review practice in whatever setting is being observed, and the notion of knowing, being aware of one’s own perspective on teaching, are seen as means to counter preconceived notions of teaching effectiveness (Courneya, Pratt, & Collins, 2008).

In setting up peer observation and peer coaching, it is important, according to Kohler, McCulloch Crilley, Shearer, and Good (1997), to develop procedures that are both feasible and effective for teachers to use. In reviewing the peer coaching literature, Becker (1996), aside from reiterating the importance of trust among participants, mentions logistical planning and provision of resources and support.

In the current study, a major form of support in terms of the observations and discussions was the tool that we had developed (see Part A) to guide the observations of literacy practice. The tool served as an indicator of effective practice as defined in the research literature to help develop shared understandings. Spillane and colleagues (2002) defined tools as being externalised representations of ideas that people use in their practice. If the ideas represented in the tool are valid (in this case are valid dimensions of effective literacy practice) and if these ideas are represented in a quality way, in this case a way that allows them to serve as indicators of the nature of such practice, then the tool may qualify as what Robinson, Hohepa, and Lloyd (in press) refer to as “smart tools”. In terms of the quality of the ideas the tool represents, these authors suggest that smart tools incorporate sound theory about how to achieve the purpose of the task in question. In most instances, it is not the tool itself that promotes the learning; rather, it is how the tool is integrated into the routines of practice. In this study the tool is integrated into the practice of peer observation of classroom practice and the subsequent professional learning discussions.

The next section details the way the current study was conducted. Researchers examining the outcomes from peer coaching programmes have examined reported changes or improvements in teachers’ pedagogy, in terms of strategies or activities (e.g., Williamson & Russell, 1990) or reports of their satisfaction (Kohler, McCullough, & Buchan, 1995). In cases where within peer coaching teachers were encouraged to experiment with new methods of teaching, they report a greater likelihood of trying new practices (Munro & Elliot, 1987). Few studies, however, have examined classroom practice or student achievement outcomes, or both simultaneously, to evaluate the programs (Kohler et al., 1997).

References (Part B 1)

Ackland, R. (1991). A review of the peer coaching literature. Journal of Staff Development, 12, 22–26.

Adey, P. (2004). The professional development of teachers: Practice and theory. London: Kluwer.

Annan, B., Robinson, V. M. J., & Lai, M. (2003). Teacher talk to improve teaching practices. set:

Research Information for Teachers, 1, 31–35.

Becker, J. M. (1996). Peer coaching for improvement of teaching and learning. Teachers Network. Retrieved 10 February 2006 from http://www.teachnet.org/TNPI/research/growth/becker

Bereiter, C., & Scardamalia, M. (1993). Surpassing ourselves: An enquiry into the nature and implications of expertise. Chicago: Open Court.

Borman, G. D., Slavin, R. E., Cheung, A., Chamberlain, A. M., Madden, N. A., & Chambers, B. (2005). Success for all: First-year results from the national randomized field trial. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 27(1), 1–22.

Bullough, R., & Pinnegar, S. (2001). Guidelines for quality in autobiographical forms of self-study research. Educational Researcher, 30, 13–21.

Butler, D. L., Lauscher, H. N., Jarvis-Selinger, S., & Beckingham, B. (2004). Collaboration and selfregulation in teachers’ professional development. Teaching and Teacher Education, 20(5), 435– 455.

Clarke, D. J., & Hollingsworth, H. (2002). Elaborating a model of teacher professional growth. Teacher and Teacher Education, 18, 947–967.

Courneya, C., Pratt, D. D., & Collins, J. (2008). Through what perspective do we judge the teaching of peers? Teaching and Teacher Education, 24, 69–79.

Datnow, A., Borman, G., Stringfield, S., Overman, L. T., & Castellano, M. (2003). Comprehensive school reform in culturally and linguistically diverse contexts: Implementation and outcomes from a four-year study. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 25(2), 143–170.

Doyle, W. (1990). Themes in teacher education research. In W. Houston (Ed.), Handbook of research on teacher education (pp. 3–23). New York: McMillan.

Feiman-Nemser, S. (2001). From preparation to practice: Designing a continuum to strengthen and sustain teaching. Teachers College Record, 103, 1013–1055.

Glazer, E. M., and Hannafin, M. J. (2006) The collaborative apprenticeship model: Situated professional development within school settings. Teaching and Teacher Education, 22(2), 179– 193.

Gravani, M. N. (2007). Unveiling of professional learning: Shifting from the delivery of courses to an understanding of the processes. Teaching and Teacher Education, 32(5), 688–704.

Joyce, B., & Showers, B. (1995). Student achievement through staff development: Fundamentals of school renewal (2nd ed.). White Plains, NY: Longman.

Joyce, B., & Showers, B. (1980). Improving inservice training: The messages of research. Educational Leadership, 37, 379–385.

Kerman, S., Kimball, T., & Martin, M. (1980). Teacher expectations and student achievement: Coordinator manual. Bloomington, IN: Phi Delta Kappan.

Kohler, F. W., Ezell, H. K., & Paluselli, M. (1999). Promoting changes in teachers’ conduct of student pair activities: An examination of reciprocal peer coaching. Journal of Special Education, 33(3), 154–165.

Kohler, F. W., McCullough, K. M., & Buchan, K. A. (1995). Using peer coaching to enhance preservice teachers’ development and refinement of classroom activities. Early Education and Development, 6(3), 215–239.

Kohler, F. W., McCullough Crilley, K. M, Shearer, D. D., & Good, G. (1997). Effects of peer coaching on teacher and student outcomes. Journal of Educational Research, 90(4), 240–250.

Licklider, B. L. (1995). The effects of peer coaching cycles on teacher use of complex teaching skill and teacher’s sense of efficacy. Journal of Personnel Evaluation in Education, 9, 55–68.

Lipman, P. (1997). Restructuring in context: A case study of teacher participation and the dynamics of ideology, race and power. American Educational Research Journal, 34(1), 3–37

Loughran, J. (2002). Understanding self-study of teacher education practices. In J. Loughran and T. Russell (Eds.), Improving teacher education practices through self-study (pp. 239–248). London: Routledge.

Morton, M. L. (2005). Practicing praxis: Mentoring teachers in a low-income school through collaborative action research and transformative pedagogy. Mentoring and Tutoring, 13(1), 53–72.

Munro, P., & Elliot. J, (1987). Instructional growth through peer coaching. Journal of Staff Development, 8, 25–28.

Pratt, D. D. & Associates (1998). Five perspectives on teaching in adult and higher education. Malabar, FL: Krieger.

Pressick-Kilborn, K., & te Riele, K. (2008). Learning from reciprocal peer observation: A collaborative self-study. Studying Teacher Education, 4(1), 61–75.

Quinlan, K. M. (2002). Inside the peer review process: How academics review a colleague’s teaching portfolio. Teaching and Teacher Education, 18, 1035–1049.

Robbins, P., & Wolfe, P. (1987). Reflections on a Hunter-based staff development project. Educational Leadership, 44(5), 56–61.

Robinson, V., Hohepa, M., & Lloyd, C. (in press). Educational leadership making a difference to student outcomes: A best evidence synthesis. Wellington: Ministry of Education.

Rousseau, C. K. (2004). Shared beliefs, conflict, and a retreat from reform: The story of a professional community of high school mathematics teachers. Teaching and Teacher Education, 20(8), 783–796. Rowan, B., & Miller, R. (2007). Organizational strategies for promoting instructional change: Implementation dynamics in schools working with comprehensive school reform providers. American Educational Research Journal, 44(2), 252–297.

Saxe, G. B., Gearhart, M., & Nasir, N. (2001). Enhancing students’ understanding of mathematics: A study of three contrasting approaches to professional support. Journal of Mathematics Teacher Education, 4, 55–79.

Schuck, S., Aubusson, P., & Buchanan, J. (2008). Enhancing teacher education practice through professional learning conversations. European Journal of Teacher Education, 31, 215–227.

Schuck, S., & Russell, T. (2005). Self-study, critical friendship and the complexities of teacher education. Studying Teacher Education, 1, 107–121.

Schuck, S., & Segal, G. (2002). Learning about our teaching from our graduates, learning about learning with critical friends. In J. Loughran and T. Russell (Eds.), Improving teacher education practices through self-study (pp. 88–101). London: Routledge.

Showers, B. (1982). Transfer of training: The contribution of coaching. Eugene, OR: Centre for Educational Policy and Management.

Showers, B. (1984). Peer coaching: A strategy for facilitating transfer of training. Eugene, OR: Centre for Educational Policy and Management.

Showers, B., & Joyce, B. (1996). The evolution of peer coaching. Educational Leadership, 53, 12–16.

Smith, K. (2003). So, what about professional development of teacher educators? European Journal of Teacher Education, 26, 201–215.

Spillane, J. P., Reiser, B. J., & Reimer, T. (2002). Policy implementation and cognition: Reframing and refocusing implementation research. Review of Educational Research, 72(3), 387–431.

Stallings, J., & Krasavage, E. M. (1986). Program implementation and student achievement in a fouryear Madeline Hunter follow-through project. Elementary School Journal, 87(2), 117–137.

Timperley, H. (2003). Mentoring conversations designed to promote student teacher learning. AsiaPacific Journal of Teacher Education, 29, 111–123.