1. Introduction

This report documents the research activities and findings of the TLRI-funded project entitled A School for the 21st Century: Researching the impact of changing teaching practice on student learning.

The project was a two-year long collaboration between key members of the teaching staff at Alfriston College and an experienced researcher from NZCER (collectively called the Professional Learning Group or PLG throughout this report). Together the PLG investigated ways teachers understood and responded to innovative approaches to scheduling time for teaching and learning, and sought evidence that the innovations had a significant effect on student learning. At the outset the PLG team hoped to be able to identify the best teaching practices to use when the learning session covers an extended period of time, such as over a three-day period or an extended lesson of 100 minutes, but we also wanted to widen discussion about the nature of “evidence” of student learning.

With these high level objectives in mind, the research questions were:

- How are extended periods of learning time (100-minute lessons and three-day learning episodes) being used to support learning?

- What are the characteristics of successful three-day episodes, as seen by students and teachers?

- What is the nature of evidence of successful learning in three-day episodes?

The first year of the project focused largely on the first of these questions. The findings, already published elsewhere, are summarised in Section 3. By the end of the first year, the main focus had switched to what were now seen as the more fruitful second and third questions. They are the main focus of this final report.

From the outset the research ran alongside, and was intertwined with, the ongoing planned programme of professional learning at the school. As will be evident later in the report, getting an appropriate balance between research and professional development was something we needed to keep watching as the project evolved in response to what we were finding. As a general rule of process, the TLRI funding supported the external researcher to visit and work with the teacherresearchers of the PLG team, and allowed them to be fully released during those times. The whole-staff work was funded from the school’s own professional learning budget allocation.

The school in context

Alfriston is a modern architecturally designed school set in a rapidly growing suburban area of South Auckland, in Manukau City. At the time of the research, the school had a decile three rating[1] which meant it served a mid-to-low socioeconomic community. As in most South Auckland schools, the student body is a rich mix of cultures, with Mäori, Pacific Islands, and various Asian cultures well represented.

In response to population pressure on existing schools, the school began with one cohort of Year 9 students. The following year it took in another Year 9 cohort and the “foundation students” moved on to Year 10. At this stage parts of the school were still being built and it continued in this manner until a full Year 9–13 school was established after five years. The so-called foundation students left school at the end of 2008, which was also the end of the second year of this research project. By that time a small number of foundation staff remained, most of them involved in this research project in some way, but many new teachers had come into the school as the roll grew and staff turnover occurred.

Setting up a new school provided opportunities for the founding staff of Alfriston to try out new ideas. From its inception Alfriston College has sought to try and put into practice various recommendations for changing established teaching practice to transform student learning for a new century. Adapting the traditional timetable structure to make space for deeper learning was part of this “21st-century vision” (Locke, 2006; Locke, 2008) and the school was keen to research the effect of the initiatives in place. These included the use of 100-minute lessons and the inclusion of one three-day learning episode each term, when the timetable for all students is suspended while students work on extended projects in mixed year-level groups. Informal feedback suggested that these initiatives were supported by teachers and students but we wanted to gather more empirical evidence about the nature of the learning occurring in both forms of these extended periods of learning time.

The school has a focus on fostering independence in learning. Ten Independent Learner Qualities are displayed in every classroom and widely discussed and modelled. They are: caring, creative, collaborative, curious, enterprising, joyful, persevering, resilient, thinking, wise. These preceded, but broadly align with the intent of, the five key competencies identified for the New Zealand Curriculum: managing self, relating to others, thinking, using language symbols and texts, and participating and contributing.

2. A summary of our research methods

This section outlines all the research activities undertaken, in more or less chronological order. As can happen in an evolving, organic research project, there has been a certain amount of tidying up after the fact because we were often so busy “doing” that some process details did not get adequately recorded at the time.

Activity in the first year

Literature review

The work in the first year (2007) was informed by a review of literature related to the use of extended learning time within a traditional timetable structure. At Alfriston this takes the form of 100-minute lessons. Much of the literature we found originated in the United States, where the practice is called Block Scheduling. Given recent interest in this practice in New Zealand secondary schools,[2] a short synthesis of the findings was published as a stand-alone research output (Hipkins, 2008). However our primary reason for conducting the review was to inform the analysis of the staff and student surveys that were carried over the same time period. The review highlighted the mixed and equivocal nature of messages from existing research and alerted us to the need to try and understand not just what teachers were doing during the extended time but why they responded as they did.

Staff and student surveys

The PLG team designed a teacher survey composed of Likert-scale items that invited respondents to contrast aspects of practice in 50- and 100-minute lessons, and between either of these and three-day episodes. The items were designed to allow teachers to express their views about what, specifically, the longer periods of learning time enabled them to do differently. During that first year the timetable still consisted of a mix of 50- and 100-minute periods[3] and the survey invited teachers to compare the learning opportunities these presented. The survey items are included as Appendix A. Forty-four teachers (71 percent of the staff at the time) responded to this survey. Participation was voluntary but the survey was completed during after-school staff meeting time to enhance the likelihood that busy teachers would take part.

A shorter student survey also contrasted aspects of practice in 50- and 100-minute lessons. This survey used identical or slightly adapted items from the teacher survey, as relevant. The purpose of the project was explained during a student assembly and data was collected during tutor time, after it had been explained that participation was voluntary and anonymous. This process elicited 312 responses from Year 10 and 12 students. Somewhat more respondents (58 percent) were in Year 10, and these students represented 68 percent of the whole Year 10 cohort. Forty percent of respondents were in Year 12 (71 percent of that year cohort). Slightly more female (54 percent) than male (44 percent) students responded.

Focus groups

One of the PLG teachers was on study-leave during the first year of the project. With the support of her university tutor she designed and undertook four focus groups with students, two groups at Year 10 and two at Year 12 (the latter were the foundation pupils of the school as the Year 9 cohort of 2004). These conversations were designed to elaborate on the patterns of student responses to the surveys. This teacher-researcher also conducted individual interviews with the foundation senior managers of the school, in order to document their understandings of the original intent of the innovations. The findings of these discrete activities are reported in her master’s thesis (Shanks, 2007) but they also informed the whole PLG team’s conversations when the survey results were reported back to the staff for discussion.

Professional learning conversations

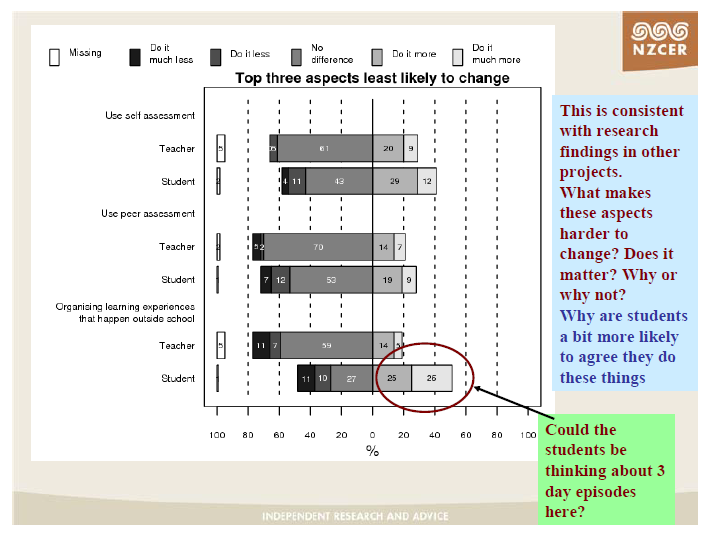

After the survey responses had been collated and discussed by the PLG team, the teacherresearchers provided leadership at a staff meeting where the preliminary findings were discussed. These were compiled into a PowerPoint presentation, with questions that the data patterns raised added by the team. Figure 1 shows a typical example.

Following the staff meeting, printouts of the individual PowerPoint slides were displayed in the staffroom, with sticky post-its for staff to write and post comments in response to the issues raised. These responses were subsequently collated by the PLG team and informed the overall analysis of the first survey results, and the publication of these (Hipkins, with Shanks, and Denny, 2008). An overview of results from the first year is included in this report as Section 3.

Figure 1 An example of the format in which survey findings were presented to staff

Note that the visual summaries collated the “no difference” responses with “do it less” and “do it much less” (in 100 minutes compared to 50 minutes). While the more usual reporting format would be to draw the centre line through the middle of the centre grouping (no difference) the PLG team chose to report to the staff in a manner that highlighted the extent of positive change (or not—as in the case being discussed in Figure 1). The more conventional format is used in Section 3 of this report.

Activity in the second year

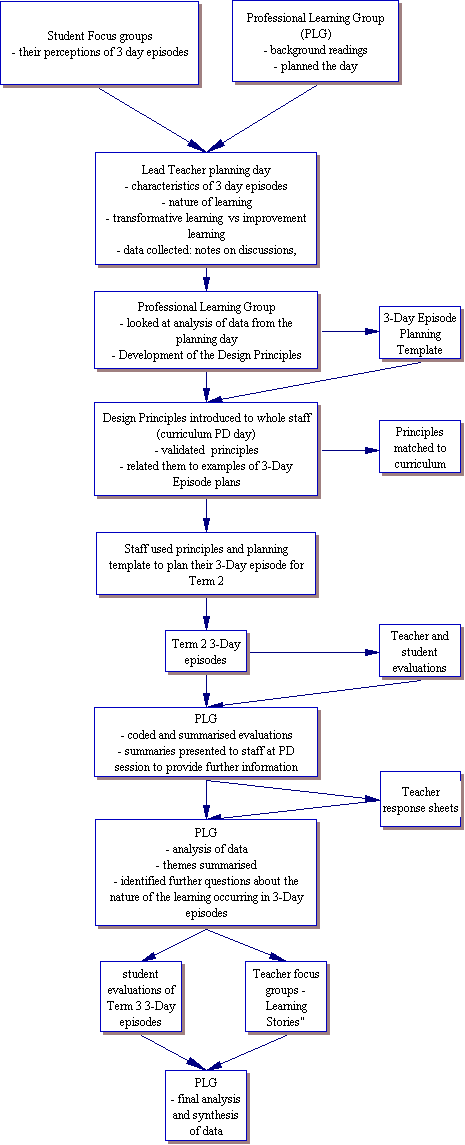

The project changed direction in the second year to focus specifically on three-day learning episodes. In 2008, the balance between research and professional learning became even more of a challenge to achieve than it had been in the first year. Despite the perceived benefits of three-day learning episodes, there was some disquiet amongst longer-serving staff that these episodes had begun to drift somewhat. While staff who had been part of the school from its first or second year were aware of the intent of the episodes, and had experienced some highly successful episodes, staff who were newer to the school were not as clear about their purpose. As the school got bigger, it was necessary to introduce a greater variety of episodes each term but there were perceptions that the quality of learning experiences offered in some episodes had begun to suffer. We saw an opportunity to address these issues via staff professional learning while at the same time learning more about the dynamics of three-day episodes and how their outcomes might be able to be assessed (the second and third research questions). Figure 2 summarises the running relationships between research and professional learning in the second year.

A design workshop in the April school break

The PLG team met early in the year to review progress and reset directions. The first formal research activity was planned for the April school break. Eighteen teachers volunteered to take part in a day-long workshop, attended by two researchers from NZCER. One researcher facilitated the day’s activities and the other took notes. All the teacher volunteers were familiar with threeday episodes and interested in consolidating their place in the curriculum of the school. All members of the PLG team were present, as was the school’s principal.[4]

The day was designed to generate material that could inform the development of a set of design principles that could make the intent of the three-day episodes more transparent and to ensure high quality planning for all episodes, regardless of their context or focus. The process used is briefly outlined in Section 4 of this report, where the principles arrived at are also introduced.

The PLG team met for a full day shortly after this session. The team reviewed the different sets of principles developed by the various small groups, looking for common themes. These were distilled to produce the principles shown in Table 2 (Section 4).

Tracking the principles in action

After the design workshop, the principal agreed to let the PLG team design and lead an upcoming teacher-only day. Several such days were provided to all schools in 2008, to allow them to undertake professional learning related to the implementation of the New Zealand Curriculum (Ministry of Education, 2007). The PLG team planned a process that would allow staff to explore links between the draft three-day learning episode principles and the high level intent of the New Zealand Curriculum, thus directly addressing the first-year survey findings that some staff saw three-day episodes as somehow separate from the curriculum rather than part of its wider implementation (Hipkins et al., 2008).

The strong parallels between the intent of the New Zealand Curriculum and the directions suggested by the design principles were evident to most participants. The staff readily agreed to use the new principles to plan their next three-day episodes. These plans were collected and reviewed by the PLG team before being put into action. Where it was felt that the principles may not have been fully understood, additional support was provided by PLG members to help other teachers sharpen their plans to better reflect the intent of the principles. The research team tracked the manner in which the principles on paper translated into actual practice during the three-day episodes in several ways.

Figure 2 Activity in the second year

Student self-evaluation

Students were invited to complete a short written evaluation at the end of the first three-day episode; the evaluation was planned with the principles in mind. The students were asked:

- What did you learn in this three-day episode?

- What are you thinking about differently as a result of this three-day episode?

- What particular things did you do during the three-day episode that made you think differently?

- Which Independent Learning Qualities did you develop or improve on during the three days? [The full list was provided so they could circle responses.]

- Choose three of these qualities and give examples from your three-day episode showing how you used each ILQ. (A table with three rows was provided for this.)

Teachers running each episode collected the completed evaluations and handed these to the PLG team. The team reviewed the responses and devised a simple coding schedule that differentiated between concrete descriptions of a specific instance of learning, more generalisable comments, and responses that gave indications of reflective rethinking of an idea, issue, or self-insight. (We thought of these as the “new eyes” comments and, although not very numerous, they were a powerful motivator for the team.) All responses were then captured in an Excel file.

In total, almost 1000 responses were collated. With the exception of Year 12, numbers decreased as the year level increased. The dramatic drop in numbers at Year 13 highlights the challenges teachers had in sustaining the participation of this final year cohort.

| Year level | Number of responses | Responses as % of year cohort |

|---|---|---|

| Year 9 | 255 | 89 |

| Year 10 | 228 | 84 |

| Year 11 | 191 | 77 |

| Year 12 | 153 | 94 |

| Year 13 | 64 | 50 |

Insights from these student self-assessments are discussed in Section 6.

Staff evaluation

The analysis of student responses was reported back to the staff, and followed by discussion of the patterns we found. In small groups, staff reflected on their own learning from the episodes and captured these thoughts as a group record. These records were collected by the PLG team for subsequent collation.

Later, staff revised their plans, or created new plans in some cases, for implementation in the next school term, with evaluation as before. The formal evaluation process was not repeated, but designers of episodes that stood out were invited to take part in one final formal data gathering activity.

Teacher focus groups

Two focus group discussions took place near the end of the 2008 school year. Participants included members of the PLG team and some other teachers whom their peers considered had implemented highly successful episodes, or who had made significant strides with their planning as a consequence of needing to address the principles.

The external researcher conducted these focus groups and took notes as the lively discussions unfolded. The questions to which participants responded were:

- This project started out with a focus on how extended learning time is used. What do you see as the good and not so good things of using three days per term in this way?

- How did the design principles work out in practice?

- Would you change anything about them with the benefit of hindsight?

- Do you think students were aware of the planned learning intentions? Why or why not?

- Has this experience made you think differently about what evidence of learning could look like?

- When we debriefed we noticed that some evidence of learning was in the form of anecdotes about things that happened later on. Was this your experience also? Is that OK?

- We also wondered to what extent students’ sense of ownership over what they made or did influenced the success of the episode. What are your views on that?

- Do you think the staff who were not involved in the workshop advanced their thinking about the structure and purpose of three-day episodes? Why or why not?

Analysis and synthesis activities

Much of the analysis took place in PLG group sessions as the relevant data was gathered, and was used to inform next steps, as outlined above. The following sections of the report discuss these “working” findings in more detail. The final focus groups were an exception because most of the PLG team members were involved as participants. The external researcher searched this data for emergent themes and wrote these up for discussion amongst the whole PLG team. At the same time, she synthesised data from the various different sources to create three “case studies” that illustrated the complexities of different three-day episodes in action. These cases are included here as Section 5. Each one was returned to the teachers who designed and facilitated the episode, and small changes in detail were made in response to their comments and clarifications.

3. The first year in summary

The first year of the project compared the use of learning time in 100-minute and 50-minute lessons and compared both of these with use of learning time in three-day episodes. The results presented in this section address research question one: How are extended periods of learning time (100-minute lessons, three-day episodes) being used to support learning?

The majority of teachers (82 percent) but under half the students (43 percent) agreed or strongly agreed that 100-minute periods were better for student learning. A considerable number of students (22 percent) were unsure, compared to just 7 percent of teachers. Likely reasons for these views can be seen in the data patterns reported next.

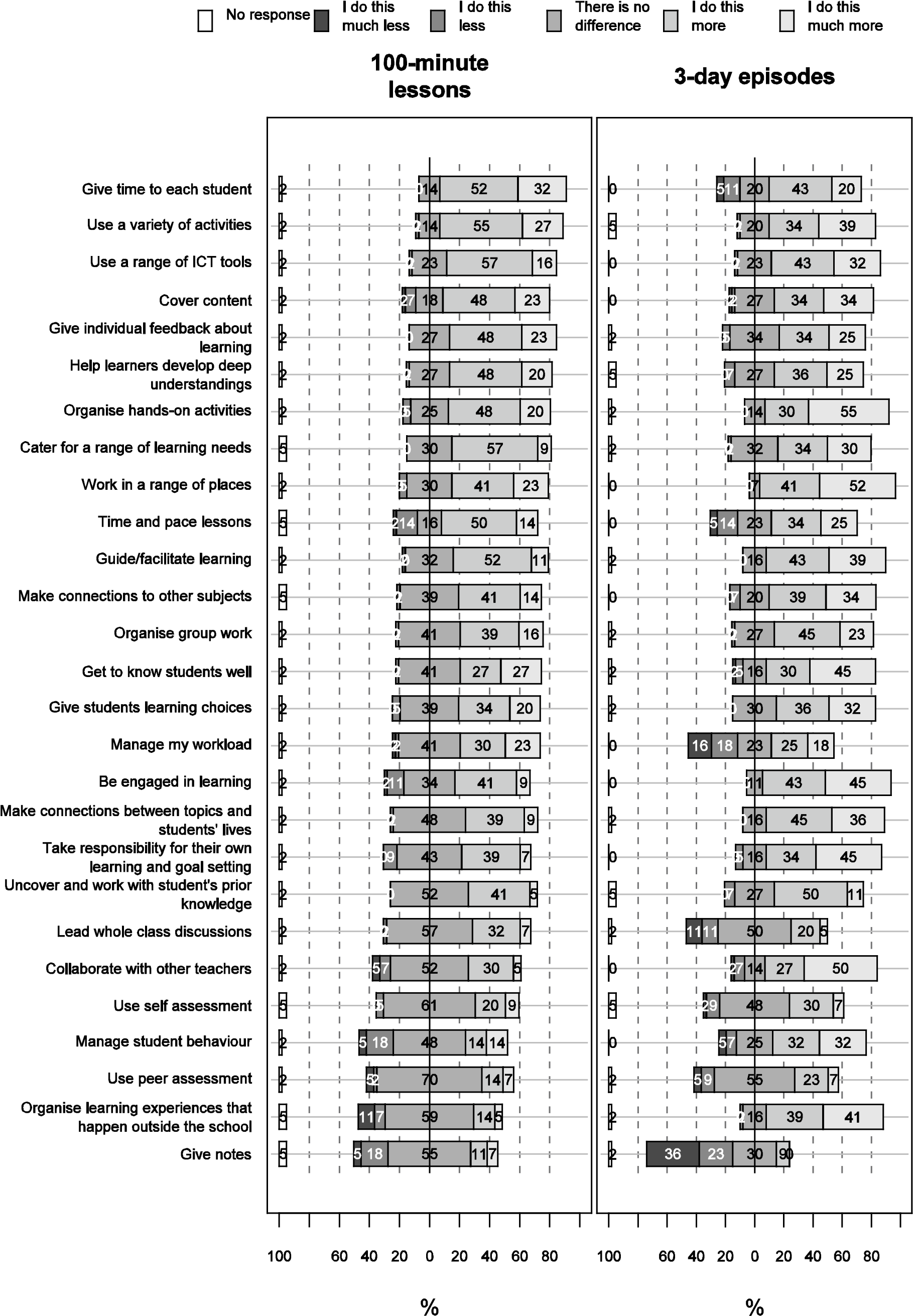

The teacher survey results

Figure 3 shows the aggregated results from the staff survey, ordered by frequency of perceptions of positive changes to lessons in 100 minutes compared to 50 minutes. Two patterns stand out in the left-hand graph (100-minute lessons).

What changes in 100-minute lessons?

The top-rated 12 or so items show that a clear majority of teachers perceived that they took advantage of the extended learning time to vary lessons and cater for a range of learning needs. For almost all items, perceptions of positive change outweighed perceptions that the longer periods impeded the practices described. (The exception was note taking which was in any case a reversed item—i.e., a practice we might hope to see happening less often.)

What does “no difference” really mean?

As frequencies drop in the “do it more/do it much more” categories, it is the “no difference” response that increases, rather than the negative responses. Towards the bottom of the rankings, more than half the teachers responded in this way. However this raises the question of whether those who perceived “no difference” use the practice in question at all, or whether they do this thing regardless of the length of the learning period. The PLG team discussed this ambiguity at length. The teachers in the team felt that one interpretation was likely to hold for some teachers, and the opposite interpretation for others. While frustrating at the time, this discussion ultimately led to the important shared realisation of the difference between seeking transformative change and improvement in traditional practice. This idea is further discussed below and in the final section.

Figure 3 Summary of results from the teacher survey

Comparing daily lessons with three-day episodes

The third pattern that stands out in Figure 3 is the marked skew to the positive change side of the graph in the responses to three-day learning episodes, when compared with either 50- or 100minute lessons. What changes most dramatically is the “no difference” category, and it changes in two ways. Nearer the top of the graph it sometimes grows somewhat bigger. We take this to mean that some teachers who use a specific practice in normal lessons keep using it during three-day episodes. With a few exceptions, the “no difference” category shrinks nearer the bottom of the right-hand graph—in some cases quite dramatically. Note taking would seem to be out of place in the spirit of three-day episodes, congruent with the increase in “do it less” responses for that item. Overall, the pattern suggests that three-day episodes enable more innovative practice, especially for those teachers who for whatever reason feel they cannot make these changes in 100-minute lessons.

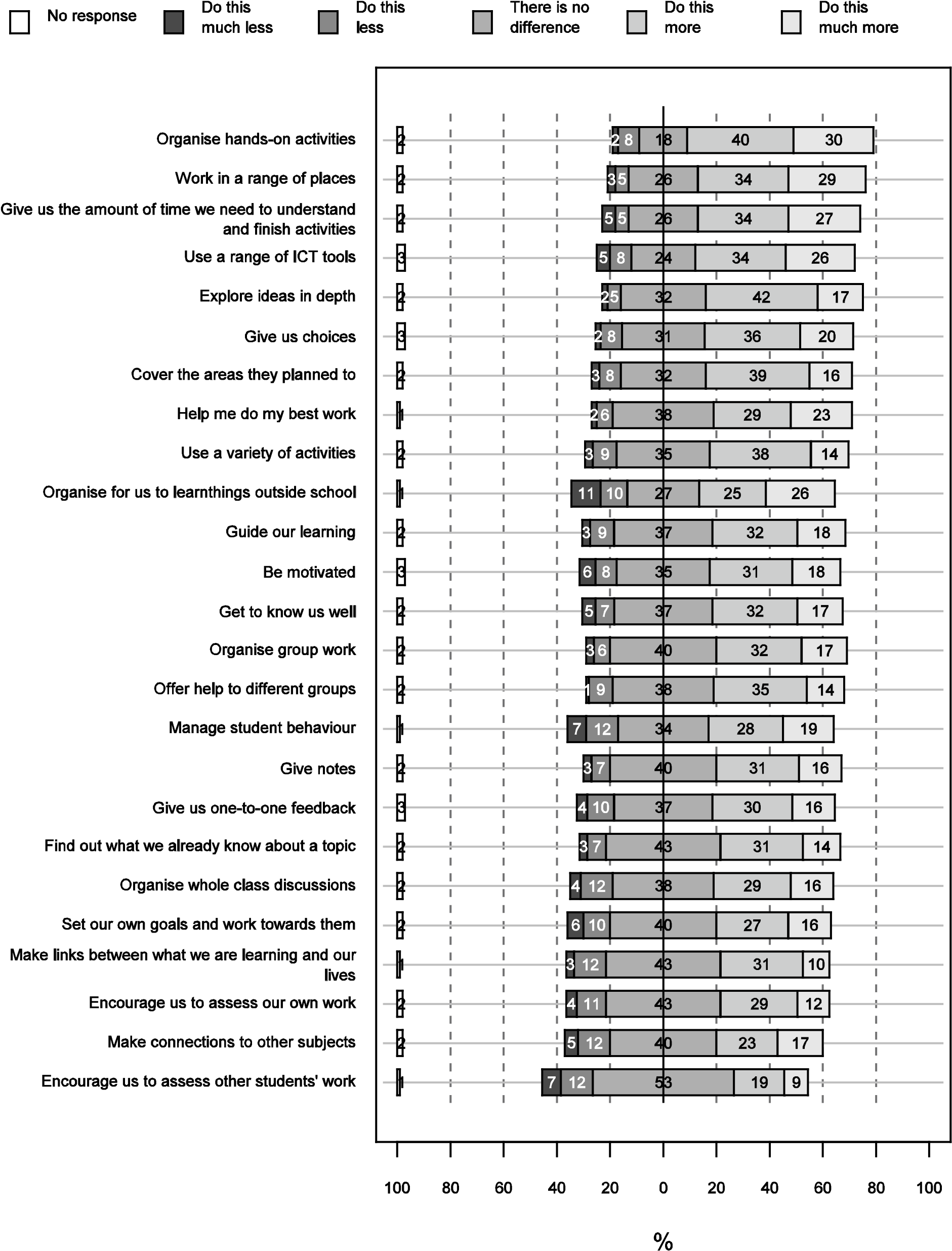

The student survey results

Figure 4 shows responses to student survey. Students were not asked to comment on differences between lessons and three-day episodes, so there is only one graph.

Note the similarity of the pattern of responses in the “no difference” category to those in the teacher graph for 50- and 100-minute lessons. Again, as for the teachers, student responses that register actual differences are skewed to the positive side of change—those differences they do perceive are much more likely to be of an opening up of opportunities during 100-minute lessons, with indications of a different quality of engagement with learning (more hands-on, deeper thinking, greater choice, and so on).

Figure 4 Summary of results from the student survey

Implications of the overall findings from the first year

The teacher data shows that greater differences were found when 50- and 100-minute lessons were compared with learning that took place in the three-day learning episodes. Both teachers and students perceived greater engagement and more opportunities to foster students’ Independent Learner Qualities during three-day learning.

During the debriefing sessions at which the results were reported and discussed, many teachers said this was because they did not have to concern themselves with either curriculum or assessment (Hipkins et al., 2008). This seemed problematic to the research team because ILQs do align very strongly with the key competencies of the New Zealand Curriculum (Ministry of Education, 2007) even when the “content” of an episode is somewhat non-traditional. Anecdotally, most teachers could differentiate between effective and less effective learning episodes, which suggested an element of assessment/evaluation was also present. Again this was likely to be non-traditional and what teachers really meant, as we confirmed when we presented back the results from the first year surveys, was that the three-day learning times did not conclude with pen and paper tests.

The survey results, in combination with the PLG and whole staff conversations that followed the presentation of the results, suggested that longer traditional learning periods are likely to operate within an improvement paradigm of school change. In such a paradigm, present structures and ways of working are made better, but underpinning assumptions may not be examined closely. This timetable model may indeed lead to considerable improvements in relatively traditional teaching and learning activities and responsibilities—without necessarily questioning either the nature of learning or the nature of the outcomes sought. Such improvement per se will not necessarily help students to meet the ongoing learning challenges they will doubtless face in the 21st century.

These findings from the first year gave indications that transformative curriculum change could be more likely to happen if teachers are supported to rethink and reflect on their experiences when planning and leading three-day learning episodes. However the survey results and associated conversations also suggested that some staff at Alfriston College, notwithstanding the clear benefits they could identify for three-day episodes, harboured suspicions that these are really a pleasant diversion from the main learning agenda, which remains firmly traditional. Accordingly other types of evidence of learning, and indeed the legitimacy of more informal or distributed learning as valued school learning, became the focus for in the second year of the project.

4. Developing the design principles

This section describes the process and outcomes of the teacher workshop held early in the second year of the project. It mainly addresses the second of the three research questions: What are the characteristics of successful three-day episodes, as seen by students and teachers?

The day-long workshop was designed with the intent of creating conditions for “psychologically spacious” professional learning (Garvey Berger, 2004) where teachers could be supported to draw on their tacit understandings at the same time as their professional expertise was seen to be valued. All were experienced in designing and running three-day episodes and had volunteered to give up a day of their holidays to take part. The venue was an old house in pleasant park-like surroundings, used for public meetings. Being away from school, with nice food for lunch, was seen as one way of thanking staff for their help and expertise so freely given.

The teachers were invited to begin by exploring the question of what makes some three-day episodes more enjoyable than others, and responding to a question about what puzzled or intrigued them about three-day episodes. They wrote initial thoughts, then shared these in pairs and with the group. Subsequent analysis showed that these teachers associated the more successful three-day episodes with the following characteristics:

- the nature of the learning (practical, experiential, tangible outcomes, no wasted time, variety, choice)

- co-construction/shared ownership of learning

- learner and teacher enthusiasm and interest generated

- relevance/authenticity (involvement in and of community, not in traditional subject areas, connections to outside world)

- different types of outcomes (informal, learning for sake of learning, seeing different skills emerge)

- opportunities to build good relationships, working with different groups of students and other teachers from normal class work.

As will be evident in the following sections, these themes continued to permeate the research right through the second year.

Following the initial thinking exercise one of the PLG team shared her “student voice” findings from her thesis research that had complemented the TLRI research with the teachers in the first year (Shanks, 2007). This was a prelude to encouraging the participants to write down the bare outline of one design principle before a morning tea break.

After teachers shared their initial thinking about principles, the next session provided input from a research perspective, with a facilitated discussion of the nature of learning, purposes for learning, and the contrast between learning for improvement and learning for transformation, which had emerged as important themes in the first year of the research (Hipkins et al., 2008). (The teachers in the PLG team were keen to draw their colleagues into the discussion of these challenging ideas.) The initial thinking about principles was a reference point as the conversation evolved. The principles were reworked, aligned with the school’s Independent Learner Qualities and matched to the key messages about learning in the new national curriculum. Each small group broke for lunch with a draft set of design principles ready to share.

After lunch groups compared ideas and also compared their own thinking with the design principles for the Northern Ireland “enriched curriculum” study (McGuinness, Gallagher, & Hipkins, 2009). (They had not seen these in the morning.) After revision of their work, a series of reflection activities rounded out the day. These focused on changes in each person’s thinking and on the manner in which the day’s activities had supported their personal learning, or not. Thus the focus at this point was on teachers as learners, and the implications for three-day episodes.

The PLG team met after this session to review the sets of principles developed by the various small groups, looking for common themes. In an intense one-day meeting these were distilled to produce the final set of principles shown in Table 2. The completed set was then introduced to the staff, and has continued to evolve, with minor changes made in the year after the project had been completed.

| Design Principle | Potential Indicators | |

|---|---|---|

| Nature of Learning The planned learning should provide opportunities to strengthen learners’ capabilities, including “learning to learn” dimensions and provide for engaging, interactive learning experiences |

Does the learning provide….?

A range of experiences Opportunities for learners to demonstrate autonomy Opportunities for learners to reflect on their progress |

Opportunities for learners to take risks and push personal boundaries

Challenges (intellectual, physical, ethical, cultural, social, practical, and/or creative) Opportunities to build relationships (learner/learner, learner/teacher, learner/wider community) |

| Ownership

The planned learning should foster autonomy by providing choice and flexibility within a supportive framework |

Choice (context, process, outcome, and/or

indicators of successful learning) Opportunities for co-construction |

For the possibility of divergent pathways to emerge |

| Connectedness, Authenticity. Relevance

The planned learning should help learners’ make authentic and relevant connections between their learning experiences and the world they live in, in ways that expand their horizons |

Is the learning….?

Framed by a clearly defined big picture idea Related to a future focused theme |

Expansive (ideas, contexts, personal skills, connections, types of thinking)

Relevant to learners’ lives now or in the future |

| Outcomes

The planned learning should conclude with an evaluation of the anticipated goals so that achievements can be celebrated |

Which types of learning outcomes are anticipated and what might the evidence look like? | |

| Strengthening the independent learner attributes | Production of an artefact | |

| Positive relationships | A dispositional change | |

| Mastery of a process | ||

| How and by whom will the learning be evaluated and celebrated? | ||

5. Putting the principles into action

As noted in Section 2, all the school’s teachers were introduced to the new design principles and explored them in the context of the newly released national curriculum. They were asked to use them to plan for the upcoming three-day episode. Most teachers were positive about the direction and support the principles provided, although some needed additional help to redesign their first attempts to better reflect the principles. The first results were reviewed after the planned episodes had been carried out, then the principles were used again for the one remaining three-day episode in the second year of the research. On this second occasion, many teachers took the opportunity to revise an episode they had already delivered, and some designed completely new learning experiences

Case studies of different three-day episodes

The rest of this section provides something of the “flavour” of three different episodes. These three “cases” combine data from a range of sources (see Section 2) and in two cases cover two sequential episodes, to capture the intent of revisions made after the first use of the principles. The first pair of episodes was designed by a teacher who took part in the day-long workshop described in Section 2. The teachers who designed the episodes discussed in cases two and three were not involved in the workshop and met the principles for the first time on the teacher-only curriculum day. All three teachers were involved in the final focus groups and their comments on the success of their own episodes informed the descriptions.

Case study one: From Shakespeare to comic

Students in this episode began by studying The Tempest. They then turned a part of the play into a contemporary comic format suitable for publication. The designer of this episode anticipated that this task could create a range of intellectual, physical, ethical, cultural, social, practical and/or creative challenges. In the following term, the teacher revised his idea to have students focus on converting a self-selected song into a two-page comic. He wanted to increase learners’ ownership of their projects and encourage them to be involved in the entire process from idea to publication.

After this second episode, the students continued to meet on a Friday after school. The teacher helped them organise visits from guest cartoonists at these times. He noted that students forged ahead with ownership of their own learning. They had shown him how to use drawing tablets and he described this as an illustration of “the reality of the espoused benefits” of independent learning.

Many of the students who chose the second three-day episode were repeating the experience. The teacher contrasted the “nice, calm, different world” of the learning environment he set up for them with the “hurly burly” of normal classes. He noted that students who wanted to be more “physical’ had chosen different types of episodes, and that the tranquillity was one of the features appreciated by the students who chose cartooning.

One challenge that arose was that the teacher effectively had two groups with very different learning needs. Those who had come back for a repeat experience of cartooning “just got started” of their own volition. The teacher noted that this was experienced as intimidating by some of the beginner cartoonists. While he had hoped they might be able to learn from their more experienced peers, the reality was that they lost what little confidence they had. He was not sure what he would do about this another time, but noted that he valued the opportunity to get a different perspective on “intractable issues” such as this.

The students were most likely to associate this learning episode with the development of their creative, perseverance and curiosity Independent Learner Qualities.

Case study two: King of kings/Sons of the Pacific

During 2008, one teacher constructed two different learning episodes with a focus on encouraging male students from Pacific Island backgrounds to value their own and other Pacific cultures and to stand tall as learners in the New Zealand school system. She wanted these students, some of whom were typically considered “problem” students, to experience successful learning as Pacific students and to gain a sense of the value their cultural resources could provide to them as learners in general. When the focus group interviews were conducted at the end of that year she had already designed a third episode that focused on similar outcomes, but entailed quite different types of activity. The teacher was invited to participate in the focus group because of the range of interesting and insightful self-reflection comments made by the students, and because there was a general perception amongst the staff that these had been outstandingly successful episodes, with demonstrable changes in the attitudes of some participants to their subsequent learning, and with very positive feedback from parents who attended the final performances.

The first episode, called “King of Kings”, was designed for boys whose families originated from the island of Niue, thus sharing the teacher’s cultural background. The second three-day episode, “Sons of the Pacific”, was open to all Pacific boys. Both episodes challenged students to draw on common and differing elements in their cultural backgrounds to devise and deliver a performance for an audience that could include their relatives as well as other students. This took place on the afternoon of the third day. The third three-day episode was going to focus on the diversity of games Pacific Island groups might play at community events and some of the students who left school at the end of the previous year were planning on coming back to support and take part during the three days. Each episode provided space for every student to demonstrate leadership at some point, with the teacher “pulling strings from the back” if they needed support.

These episodes clearly fulfilled the design principles—they had clear learning intentions and the teacher noted that she frequently drew the students’ attention back to these—“what are we here for? What’s our aim?” She was in only her second year of teaching at the time, and said that understanding the principles had initially been a challenge—“I had to go and sit in a corner and think about them”. Once she “got” them however, the design and delivery of the episodes came much more easily. Asked how she had encouraged such perceptive written reflection from students not known for their writing fluency, the teacher described a practice along the lines of a poroporoaki.[5] Gathered in a discussion circle over a shared lunch on the third day, students spoke one at a time about what the learning had meant for them. As they heard others speak, each was free to mentally shape and expand their own ideas, so that when it came time to write, they had already rehearsed what they might want to say.

The students were most likely to associate this learning episode with the development of their joyful, creative and collaborative Independent Learner Qualities.

Case study three: Knit for the new and needy

The teacher who designed this episode loves to teach students the skills of hand-knitting. She had delivered three-day episodes with this goal in previous years but admitted that the design principles in place for 2008 had given her “a lot to think about”. This time, she set the episode in the context of caring for premature babies. Students knitted tiny garments and a visit to the neonatal unit at a nearby hospital gave them a vivid contextual experience of the need for these. Some students were repeat participants in this three-day episode “for the simple enjoyment” of knitting together.

In common with the two other case studies described here, the students in this episode produced interesting reflections on what they had learned:

I made beanies and booties for premature babies, this made me think differently as it’s such a great cause to be helping and I want to help others with knitting. Also I just want to volunteer for other causes because it made me feel good to be helping someone else.

The teacher noted that the “relaxed mode” of knitting was conducive to reflective conversations, and this probably helped students to complete the evaluation thoughtfully. The students were most likely to associate this learning episode with the development of their caring, joyful, creative and persevering Independent Learning Qualities.

6. Learning from student reflections

The PLG team planned to capture the students’ thoughts about the effect of the three-day episodes as one way to gather data that could potentially inform the question of what evidence of learning could look like when non-traditional outcomes are envisaged (research question three). This section reports on patterns in the responses received after the first of the episodes in which the principles were used. The PLG team was particularly interested in responses to the open questions about learning (see Section 2), although many of the nearly 1000 responding students completed only the closed format questions such as circling the three Independent Learning Qualities they thought they had used the most.

The nature of the open responses

The examples that follow have been chosen to illustrate the variety of learning experiences on offer, and to demonstrate differences in the qualities of the responses the questions elicited. The majority of the open responses were direct statements about some concrete aspect of learning. “I learnt about ….”, as in the following examples.

Facts about the Treaty of Waitangi—what was the importance of the Treaty of Waitangi and why was the treaty brought or why it was made in the first place. (Year 9)

How long and complicated the process of law in a court is. (Year 10)

I learned about the Indian culture how interesting and respectful they are. And their food is delicious ‘nd spicy. (Year 10)

Self defence is more mental and spiritual over physicalness and power. (Year 11)

It is important to eat healthily and look after yourself when you are young so that you stay healthy when you are older. Exercising is easier when you’re with your friends. (Year 11)

I learned about body image and how the media influences people’s image of a healthy person. (Year 13)

A few of the older students wrote longer responses that combined direct statements about what they had learned with more explicit statements of the value of the learning for them personally:

I learnt that Sikhism and Buddhism have something in common, they both want us to be better people and to see what it is that life has to offer. I am thinking that both religions teach us about life and how to overcome what it is that we have faced. By making the poster for Buddhism and I realised that to go through life, you have to suffer, no matter what the outcome is, we always suffer (Year 13).

Although the design principles emphasise the importance of being clear about the “big ideas” the learning is intended to address, very few students described a more abstract idea or insight. Both these examples are reflections students made about the “King of Kings” episode, supporting the teacher’s comment that she reminded the students regularly about the bigger picture of why they were undertaking the planned activities (see the case study in the previous section):

That all cultures aren’t the same there is a background (history) behind each culture. (Year 9)

Just learning about every culture dancing showed how different we are but still we are alike. (Year 11)

Some students cited specific experiences that made them think differently, about some aspect of life, or about themselves. These descriptions of what they now saw with “new eyes” as a result of their experiences during the three day episodes give glimpses of range of different types of learning outcomes:

I’m thinking about treating my animals with the same respect as I would give to myself. (Year 9)

[When] I’m making my day to day decisions, I now begin to consider whether my choices are environmentally friendly. After visiting Eco village, I compared their lifestyle to mine and ever since, I have began thinking differently. (Year 10)

How lucky I am to not live in the times of those past especially Minnie Dean’s time. (Year 11)

After this 3 day episode I think differently about how I interact with other people. It was a lot easier to get to know them at camp than at school. (Year 12)

I am now thinking about implications that could arise from humans travelling to Mars. (Year 12)

It is really important that New Zealanders especially Pacific Islanders are self aware about diabetes and the ways they can prevent it from occurring even with just little lifestyle changes. (Year 13)

A number of students (18 percent) wrote open reflections on themselves as learners now or in relation to possible future learning and work. These were additional to the Independent Learning Qualities they identified:

I think differently about being an astronaut as I wouldn’t have minded being one but now I know more I think that I will never consider being one. Because of all the training and problems they face in space. (Year 9)

I am thinking more differently about my life and how to live it. I’m going to get out there and try new things. (Year 10)

I think that I’m not a lousy memoriser now. I started to learn differently. (Year 11)

The knitting helped my concentration and my co-ordination. (Year 11)

I used to always want to work independently but I’ve found it easy and nice to work with a group also. (Year 12)

It is a lot harder than I expected and I also realised this industry wouldn’t suit me. What I could possibly do in my future, instead of hospitality. (Year 12)

Sports is soo much fun!! I wish I knew that before!! I would have joined a team. I should have done sport. (Year 13)

That persevering is a good thing to do—and you can learn from your mistakes and we had fun completing a task. (Year 13)

As the case studies in Section 4 illustrate, the most frequently cited Independent Learning Qualities were those that might be anticipated as relevant to the type of task, and varied from episode to episode.

What the teachers thought about the student reflections

The brief feedback from many students provided scant evidence that they were aware of, or perhaps willing to comment on, the teachers’ planned learning intentions, even though the design principles had supported a planning process to allow these to be more clearly articulated than in the past. During their professional learning time, teachers reviewed the results and reflected on why so many students struggled to give more than superficial comments.

The following four broad themes are based on the 12 summaries of group discussions that were returned at the end of the debriefing process. The group discussions provide a useful snapshot of the complex mix of potential influences on student self-assessment. The researcher took the large sheets on which the discussions were captured and read them all for emergent themes. Once it was apparent that there were four types of comments, those related to each theme were collated and a short analysis commentary prepared by the researcher. This analysis was returned to the PLG team, with the original sheets, for discussion and conformation. The themes are as follows.

What students bring to self-assessment as reflection

Half the ideas expressed (18/33) pertained to deficits or disinclination on the part of the students. Lack of thought was the most common response, with students seen as taking “the easy way” or perceiving there was “nothing in it for them”. The next most common type of teacher comment related to the need for more guidance for students so they knew how to reflect. Some groups thought the open-ended questions did not work and students needed more scaffolding. Others realised the skills needed to reflect had to be taught. (These types of comment were also counted in the next theme.) A few groups saw a lack of writing skills as a barrier to reflection. Students who struggle to express themselves in writing “like to keep it short”. Rather than assisting students to improve this skill, at least one group saw a verbal debriefing as the solution. Of course it is also possible that keeping it short is linked to the perception that the task is not worthy of greater effort.

How teachers support reflection (or not)

The most common comment in this category related to the need to model reflection skills, as outlined above. However, a set of more prosaic observations was almost as common. From this perspective teachers did not allow sufficient time for reflection, or positioned all of it at the end of the third day when “everyone was tired”. Half of the groups (6/12) noted a need to “build in time for reflections as you go”. Four groups pondered whether they had communicated their intentions with sufficient clarity. They noted a need to link the unfolding learning to the “big picture” at regular intervals during the three days, and to be very clear about what this big picture could be right from the planning stage. One group noted that teachers often prompt by asking students what has been learned, so that this becomes an habitual way of thinking about learning.

The nature of the learning

Three comments pertained to the more concrete nature of the intended learning in some episodes or noted that each episode is “only a taster”. It seemed that these teachers thought there was little to actually reflect on in more practical episodes! The data from the student reflections does not bear this out, as illustrated in the comments above. Nor do comments from the teacher focus groups, reported in the next section.

Other ways to heighten students’ awareness of their personal learning

Several groups reflected on the need to actively support students to see how the intended learning might link to their everyday lives, or carry over into their timetabled lessons. One group suggested swopping roles:

Ask them “if you were the teacher of this three day episode, what would you do differently to achieve these goals?”

Another group suggested giving more frequent and immediate feedback in the form of commendations when learning qualities were exhibited by students, to heighten their awareness of these. Pondering why so few students indentified being enterprising as a learner quality, one group asked:

Why doesn’t enterprising feature more often when so many episodes involve planning, problem solving and design principles. Do learners not know what enterprising means or are they not feeling enterprising?

This group suggested that an episode could begin with a discussion of what being enterprising can look like, if this was a learner quality the teacher hoped to foster. Several other groups also mentioned a need to focus the intended learning much more clearly at the outset, accompanied by the gathering of some data on where students were at in relation to the intended learning, so that comparisons could be made as the three days unfolded.

7. Characteristics of successful three-day episodes

This section draws mainly on the focus group conversations held near the end of the second year of the project (see Section 2). As with the teacher reflection data, the researcher took away the notes from the focus groups, searched these for emergent themes, and then documented those for discussion by the PLG team. Several clear themes emerged from this analysis of the two focus group conversations. Five of these, outlined next, relate to the second research question: What are the characteristics of successful three-day episodes, as seen by students and teachers? A final theme has been held over for the final section of the report because it directly addresses the nature of evidence of successful learning in three-day episodes, which is the third research question.

What makes for a successful three-day episode

Four broad clusters of characteristics emerged in the focus group conversations. These are described next. Some characteristics align to other research of which the teachers were likely to be aware. For example the discussion of learning relationships aligns to the underpinning principles of the Te Kotahitanga programme[6] (Bishop & Berryman, 2009). However, other parts of the discussion, such as both teacher and student anticipation, ownership of and ongoing involvement in learning, seem aligned with parts of the school’s vision that are not necessarily as evident in other more traditional school settings. At the end of this section a short discussion links the described characteristics to data from the teacher professional conversations reported in the previous section.

Characteristic one: Clarity of purpose

The focus group participants said the design principles were valuable because they made teachers “sit and think”. They provided a vehicle for re-examining the premises of the three-day episodes whilst setting out “base-line expectations”. One teacher noted that planning for her small group of teachers was a richer experience because the principles gave them a structure for a dialogue that changed their whole perception of, and justification for, the episode they were in the process of designing. Another teacher noted that the design principles “help you focus on the big idea way more”. She noted that once this high-level intent had been clarified it informed the goals, the planning, the actual doing and the reflection after the episode. Yet another teacher noted that the design principles had made her think in a future-focused frame about “learning for life”. Later she noted that “the design principles have transformed our practice”.

As the case studies show, teachers enjoy being able to introduce students to a personal passion during three-day episodes. One teacher noted that the principles, with their focus on purpose and outcomes, “distance you from that initial enthusiasm” so that you can take an interesting idea and focus on its educative potential. In a similar vein, another teacher noted that it is probably easier to start at the “fun” part of the idea (i.e., personal passion), and then determine the big ideas that could underpin the learning, rather than vice versa.

Two of the case studies above began with a strong personal interest which the teachers then linked to Independent Learning Qualities and relevant big idea(s), but the “Sons of the Pacific” three-day episode was designed the other way around. Starting with the big idea had given the teacher ideas for further episodes that could look quite different on the surface while working towards essentially the same important outcomes for students from Pacific backgrounds. Notwithstanding their different starting points and planning processes, the underlying message was the same— successful episodes have a clarity of purpose that guides decision-making and action for both teachers and students.

Characteristic two: Learning benefits are evident and able to be anticipated

When students, or in some cases parents, do not perceive the learning value in three-day learning episodes, they may not support them (e.g., students may be allowed to stay away). However the conversation that unfolded between the teachers indicated that this is not necessarily a straightforward case of not understanding the 21st century ideals that underpin the episodes. Some of the best supported episodes have had a focus that was “right away from traditional learning” and the subject-related episodes have not necessarily been better supported than others. The teachers perceived a need to design personalised, authentic and relevant learning and then to “sell” the designed episode in a manner that would engage students’ attention and encourage anticipation of the learning to come.

Teachers in one of the focus groups noted the importance of the anticipation that could be generated by pre-meetings held once students had selected options. Initially designed for administrative purposes, the pre-meetings evolved beyond this narrow focus once teachers realised discussion of the likely learning experiences whet the students’ appetites for more to come, and helped them “mentally prepare” for the challenges they would face. One teacher described it as “laying down the [welcome] mat”. This was the teachers’ first opportunity to show the students the broader learning intentions they had planned in response to the principles, and to prime them for keeping a focus on these as the actual learning unfolded. As one noted, knowing the rationale ahead of time helped students see how “all the bits fitted together” as they happened. They reflected on the difference between this more leisurely introduction to prospective learning and the immediacy of traditional lessons, when anticipation, delivery and evaluation must all be completed within the 100 minutes allotted by the timetable.

Characteristic three: Learning relationships are strengthened

Some teachers also noted that pre-meetings gave the opportunity to establish good relationships with the students before the learning episode got under way. As one teacher said this then allowed the group to “hit the ground running”. Students too could see who was in the group and begin to establish productive learning relationships, or change to another group if they did not feel comfortable. They could ask questions and ensure they were “ready to go”. They could go away and share with friends, comparing the learning they anticipated, thus building a “buzz” of positive expectations. This thread of the conversation reached the conclusion that, given their evidently pivotal role, the 15-minute meetings should be planned for as carefully as the actual episode.

Several teachers noted that the extended engagement with students over the course of the three days fostered a “deeper, stronger” relationship with students, even when they already taught them in traditional subjects. One noted that “for the first time, I’ve lived the life of a primary school teacher” and it had changed his relationship with the students. This teacher also noted that when the timetable is suspended, the group can take breaks when they need them, and are usually “waiting to get back to it” afterwards.

One teacher noted her improved relationship with a student who had previously been “very difficult”, saying the three-day episode gave the student a chance to see her “in a different light” as well. Another teacher noted that when two teachers work together on a three-day episode they can take it in turns to “play” a little with the students, which can involve “letting your guard down” safely because the other person is still “in the teacher role”.

These benefits also extended outside the classroom to the wider school, for example they can include friendlier interactions with students while on grounds duty: “the relationships go on”. One teacher noted that the school’s restorative justice processes were easier to implement when episodes did happen in the playground.

Another teacher described taking note of what students enjoyed eating so that she could use these foods, rather than her own preferences, as examples for discussing economic concepts in class.

Characteristic four: Students and teachers alike take ownership of their learning

The focus group participants saw exercising ownership over their own learning as crucial to students’ success. As one teacher noted, students “come for different reasons” and the structure of three-day episodes allows them to set their own goals and “follow that path”. The teacher who organised the comic drawing episode said the students were teaching him how to use drawing tablets. He saw this as a demonstration of Independent Learning Qualities in action. It was he said “the reality of the espoused” vision of the school.

Ownership of personal learning was seen as important for teachers too. The teacher who designed and facilitated the Pacific performance groups noted that, once she understood the design principles, ownership of her episode became very important to her success. Illustrating the power of making space for personal difference, she noted that her own schooling had “indoctrinated’ her into thinking about girls as performers, and working with boys had given her the opportunity to open up her own repertoire of teaching experiences and think about herself in a different way.

A challenging aspect of ownership is learning to take responsibility for failures as well as successes. One teacher noted that the non-judgemental nature of debriefing processes made it easier for students to “admit and take ownership of mistakes” and to see feedback as helpful and well intentioned. In response to this reflective comment another teacher asked “how can you measure that?”

Not all episodes were seen as meeting the ownership condition, however. There was a view that some teachers needed to “check what kids want to be doing” and their episodes tended to become default options for students who prevaricated while popular choices filled up.

Ownership issues: Drawing together different threads

Most three-day episodes generate a product of some kind. During one all-day meeting near the end of the project, the PLG group compared different episodes which were intended to generate a product, informal student comments about these, and anecdotal teacher conversations and observations about both the episodes and the actual products. With the ownership theme in mind, the group identified two qualities for the “ideal” type of product, both of which seem to be important for engaging students in meaningful sustained learning:

- The product is personalised—students bring their creative and critical energy to bear on the form that it takes.

- There is something at stake—the product matters for more than simply being produced.

Further discussion between the PLG team identified a broad continuum of possibilities for each of these qualities.

- Stakes are high when there is a public performance of some sort or there is competition involved. In both cases these is a critical audience awaiting and the performance, publication or etc needs to measure up to expectations.

- Stakes are medium when the product is intended for use beyond the personal, so must be of an acceptable quality (for example the knitted baby garments).

- Stakes are low when the product is for private use or pleasure only.

- Ownership is high when the product cannot be produced without both critical and creative input from the student.

- Ownership is medium when there is space for creative input within predetermined parameters.

- Ownership is low when the task can be completed by following instructions or copying.

The PLG team then discussed how these dimensions might interact, again drawing on anecdotal accounts of students’ learning and teachers’ reflections on this learning. Juxtaposing these two dimensions, we arrived at a pattern that looks like this:

| High stakes | Low stakes | |

|---|---|---|

| High ownership | Most engaging Potentially transformative |

Can be of high value to student (e.g., when making something they want for themselves) |

| Low ownership | Both of these are more likely to be disengaging | |

This analysis led us to conclude that, depending on the personality of the student, the stakes might not be as critical to engagement as the ownership quality of the episode. Students for whom ownership generated a high level of intrinsic motivation did not necessarily need the outcomes of their learning to be seen as high stakes by anyone else. This was especially so for female students who made items for their personal use. What matters to such students is that they value what they are doing.

Rather more of the students, by contrast, appeared to relish the extrinsic motivation of a competitive performance of the outcomes they sought. Of course, this is not a simple either/or dichotomy. A public performance of one’s own goals still has to be underpinned by a selfgenerated motivation to put in the necessary effort and practice to reach the intended outcomes. Both social and personal factors are likely to be in play here.

Reflections on what does not work

As will be evident from the above discussion, the teachers of this school are comfortable reflecting together. It is part of the culture of the school, and focuses on both successes and things that did not go so well, from which the teachers need to learn. One focus group teacher noted that they needed to learn from experiments that had not worked well in the past. An example was making an episode “semi-compulsory” to meet a specific curriculum need for a group of students. Some students defied teachers by choosing elsewhere. This process could also send mixed messages if more “academic” episodes were expected to be less enjoyable by those who rejected them, despite being enjoyed by those who acquiesced and took them. This tended to reinforce views that three-day episodes were about “having fun” and, by implication, not about learning.

The focus group conversations were also qualified by the caution that three-day episodes are not a miracle cure for disengagement. Some alienated students simply find yet more ways to “slip through the cracks”, or band together to choose an episode that they think will tax them the least. Students may experience even further reductions in self-esteem if “they bomb out here too”. The teachers worried that this could exacerbate differences between disengaged students and others.

Near the end of the conversation, one group asked that, if the benefits they had discussed were so evident, why they did not use the same processes in regular classes. However, echoing themes from the first year of the research, they concluded that, even with 100-minute lessons, there was “not really the time”.

8. What constitutes evidence of successful learning?

What does success look like when learning is framed as being more holistic and participatory, and how can these news ways of thinking about success be documented? This third research question (what constitutes evidence of successful learning in three-day episodes) exercised the research team throughout this project and was a specific question for the two focus groups carried out at the end of the second year. This section documents that discussion under three broad themes:

- participation and engagement

- continuing demonstrations of competency

- learning to learn.

The teacher focus group comments are followed by a discussion of the assessment implications if these types of evidence are to be taken seriously and documented. The section ends with a brief discussion of the possibility of gathering data about the opportunities to learn that teachers create, if accountability is the fore-grounded purpose for the assessment activity.

This section takes for granted that rich three-day episodes will expand students’ and teachers’ repertoires of knowledge and skills. This does not mean that these are not seen as important, but rather that evidence of learning in these areas already has a strong assessment tradition, to which this project has little to add.

Participation and engagement as evidence of learning

One teacher commented that too many of his peers still think of assessment as “some physical thing you can mark”. For him the learning process was more important. Responding to this theme, another teacher noted that it was much easier for students to show their Independent Learner Qualities as combinations in action during three-day episodes. The design principles pushed teachers to anticipate what these combinations could look like, so that they were more alert to any dispositional evidence that presented. She noted that the Independent Learner Qualities did not tend to be integrated into traditional planning in the same way, and hence were less likely to be a focus in conventional lessons.

Making links between school learning and wider contexts

Using understandings from one context when thinking in a quite different context could be seen as evidence of engagement, although such evidence might not be immediately apparent. For example, a science teacher noted that some students were more willing to critically question what they saw on television after taking part in a three-day episode related to forensic science. She said they were more analytical, questioning “the logic of proof” and noting that going straight to the “thing that works first off” was not a realistic representation of the reasoning processes scientists would need to follow.

Demonstrating learning to others

The previous section discussed learning episodes that culminated with a public performance as visible evidence of the learning that had taken place. The “Sons of the Pacific” case study is an example. One teacher noted that all the original three-day episodes had included a celebration of learning at the end. Now, with a wider range of types of episodes, this was not always seen as appropriate.

Extending this discussion, the group contemplated processes for demonstrating learning throughout the episode, not just at the end. For example, one possibility is that visitors are allowed to come to a group at certain times, when students can demonstrate what they have been learning and doing. One teacher noted that visitors to one of her episodes had opted to take this episode in the following term. At the moment visiting happens “by word of mouth” but if this was seen to have learning-to-learn benefits it might be possible to create a process to allow it to happen in a manageable fashion.

Learning about yourself as a learner

Much of the “evidence” of learning discussed in the focus groups was supported by anecdotal evidence of changes in students’ attitudes towards themselves as learners. Wider benefits were seen to accrue when students had more positive experiences of their learning capabilities and potential. For example, one teacher commented that, for some, the key learning in a successful three-day episode had been that they were “not really dumb”. Some of the student comments reported in Section 6 support the claim that this could be a change which a student was aware of, and feeling positive about. However, it seems there is still work for teachers to do. Another teacher noted that while students do indeed see themselves in a different light, they tend to experience this as “freedom and permission”, without necessarily being able to articulate the wider learning connections that the teacher can see: “that comes after reflection”.

Learning about learning as a main outcome

Illustrating what could be done differently, one episode was designed with the experience of being a learner as its direct focus. This demanding but greatly enjoyed episode simulated the learning demands experienced by a professional athlete. On the first day all the students had to learn to skate backwards. The focus was not so much on being successful (although that obviously gave satisfaction) but on what it felt like to have to persevere to learn a really hard, unfamiliar skill.

The teacher noted that the students were “physically shattered” but all came back the next day very motivated to keep going. She described how one of these students had “turned around” and was now working well in her subject class. She pondered whether this was a result of being more focused on personal goals and feedback about these, or because of the student’s improved relationship with her as his teacher.

Teachers and students learning together

One teacher noted that they are often “learning alongside” students in three-day episodes, so it is much easier to model good learning approaches and to show how teachers too can improve their learning with practice. Another teacher noted that this type of learning space cannot be mapped out in advance, which is “scary in case it goes wrong but you have to let go” of control. A more structured learning episode was raised as a counter-argument, but the designer of that episode noted that students still had to negotiate a personal path through the overall structure.

Increased self-confidence/self-esteem

Seeing yourself as a learner is a dispositional change, rather than an easier-to-document case of “knowing that…, or “knowing how…” An increase in self-confidence to be a different person around school in general, or to take risks with more public demonstrations of learning, was a theme threaded through both focus groups.

One teacher (not the leader of the Pacific group) noted the emergence of a group of Pacific Island students as a “cultural and leadership force” in the school. He attributed this to the increase in their self-esteem and noted that such a development would not usually be connected to improved work in a subject area (although the teachers in the focus group clearly saw this possibility). Another teacher noted that junior and senior students mixed better in the grounds after working together in three-day episodes.

A Year 13 (final year) student addressed the school prize-giving so movingly that teachers were overwhelmed and “some kids cried too”. Pondering this, the teacher who described the incident asked “how do you measure the people we’ve become”? The group’s attention then turned to another moving reaction from the mother of three brothers who took part in “Sons of the Pacific”, teaching and leading other students in the performance of a Tokelauan action song. This was an event the boys’ mother had never expected to see and her pride and joy was evident to all who witnessed the event.

Continuing to strengthen competencies

One of the aspects raised in the focus group discussion was the time frame within which evidence is gathered. Demonstrations of competency include dimensions of agency, resourcefulness, and breadth and depth of application. If these are genuinely valued as learning outcomes, then evidence of their strengthening over time ought to be a valued indicator of learning progress (Carr, 2008). Such evidence will be missed when learning gains are only documented during or at the immediate conclusion of learning, regardless of whether or not they focus only on products of learning.

In both focus groups, there was discussion of anecdotal evidence of engagement and learning benefits well beyond the actual three-day episode. For example, a number of students who had learned to knit came back to ask for more wool and brought back the products of their efforts. Some of this group moved on to more ambitious knitting projects, and one taught her mother this complex set of skills. The comic students organised a regular after-school session on Fridays where they could draw together. With the help of the teacher, invited guest comic artists sometimes came to these sessions. More recently one student from this group has formed a successful company to design and screen print tee shirts for local sales.[7]

Assessment issues when non-traditional evidence of learning is sought

Traditionally learning has been framed in acquisitive terms. Students are deemed to have achieved learning success when they demonstrate possession of knowledge and/or skills that they did not previously appear to own. Improvements in teaching are directed to making the processes involved in acquisition more efficient and durable, and the act of learning is typically perceived in behavioural or cognitive theoretical framings.

Transformative goals do not so much replace improvement goals as add powerful new dimensions to them, and they shift the broader theoretical frame of reference outwards to a sociocultural view of learning. As well as acquiring new knowledge students are challenged to show they can use it in meaningful ways. Products, processes, contexts, and supports all matter, and there is a new focus on dispositional components, including the long term goal of being ready, willing and able to continuing to learning throughout and beyond the school years (Carr, 2008). Thus, learning entails participation in knowledge-building, not just acquisition of knowledge (Sfard, 1998).

The teachers did draw on a sociocultural view of learning throughout the focus group conversations, whether they consciously realised this or not. A sociocultural perspective appears to be embedded in certain “ways of being” in the school. An emphasis on relationships and their effect on learning was threaded right through both focus group conversations, as were references to scaffolding and modelling learning, and the powerful effect of ownership and authenticity of learning tasks. These teachers were comfortable with the idea that evidence of learning need not continue to be framed in terms of traditional outcomes. Nevertheless most of the alternative “evidence” they cited was anecdotal, and would not have been gathered systematically had the focus group and PLG team conversations not taken place. Why not, when this was an issue the design principles asked teachers to explicitly address? Looking back over the discussion above, several practical assessment issues can be identified as barriers that need to be addressed if more systematic changes in assessment practice are to be achieved.

Building new expertise in group assessment