1. Introduction

This report discusses findings from a two-year Teaching and Learning Research Initiative (TLRI)funded project entitled A collaborative self-study into the development and integration of critical literacy practices. During this time, 2006–7, four Dunedin primary schools and one secondary school, involving a total of 16 teachers, took part in the project. The participating teachers became familiar with the literature on the theory and practice of critical literacy and developed, implemented, and evaluated critical literacy strategies in their regular classroom programmes.

Critical literacy has a long history and a number of different theoretical influences (Larson & Marsh, 2005). We use the term “critical literacy” to describe ways in which teachers and students can deconstruct texts (Lankshear, 1994).

The findings of our 2005 research (Sandretto et al., 2006) led us to believe that critical literacy for classroom practice involves supporting students to become aware that:

- texts[1] are social constructions

- texts are not neutral

- authors draw upon particular discourses[2] (often majority discourses) and assume that readers will be able to draw upon them as well

- authors make certain conscious and unconscious choices when constructing texts

- all texts have gaps, or silences, and particular representations within them

- texts have consequences for how we make sense of ourselves, others and the world.

Another important aspect of critical literacy for us is supporting students in making connections between texts and their lived experiences.

Teachers and students have particular roles when engaging in the classroom practice of critical literacy. Teachers are responsible for setting up and maintaining a caring and supportive environment where students respect each other’s responses and experiences, and can develop greater empathy for others. Teachers are also responsible for modelling a questioning stance towards texts. Students are responsible for contributing to discussions with the understanding that ideas are under consideration, but that critical literacy is not about critiquing people. Teachers are responsible for assisting students to consider multiple interpretations and readings of texts, rather than to search for the one ‘right’ reading. And finally, teachers are responsible for co-constructing understandings with students by supporting students to develop a meta-language of critical literacy, or a language to talk about critical literacy. (Sandretto & Critical Literacy Research Team, 2006a, pp. 23–24)

The Critical Literacy Research Team argues that critical literacy forms an important part of a multiple literacies, or multiliteracies, view of literacy and literacy teaching. Multiliteracies position reading as “a social practice” (Luke, 1995, p. 97), rather than “simply the ability to read and write” (Walter, 1999, p. 31). A number of educationalists have highlighted the “new times” we are preparing students for (Gee, 2000). We believe that in order to be successful global citizens in our rapidly changing world, students will need to develop a “repertoire of practices” (Luke & Freebody, 1999, p. 3) to engage with texts. The Four Resources Model by Luke and Freebody (1999) provides a framework for the “repertoire of practices” that students need to develop. This model suggests that the repertoire of practices that students need to acquire includes: code breaker, text participant or meaning maker, text user and text analyst (Anstey & Bull, 2006; Education Queensland, 2000; Luke & Freebody, 1999). Code breaker refers to the practices readers use to break the codes and systems of written, spoken, visual and multimodal texts. Text participant relates to the ability of readers to make meaning from texts. Text user represents the practices of using texts effectively in everyday situations. And, lastly, text analyst emphasises that texts are not neutral and signifies the practices of analysing texts.

Making meaning, or reading comprehension, in its most general sense can be described as the construction of meaning through purposeful interactions between readers and texts (Caygill & Chamberlain, 2004; National Reading Panel, 2000). Reading comprehension involves multiple processes including the retrieval of information, making inferences, the interpretation and integration of ideas and information, and the examination and evaluation of various elements of texts (Caygill & Chamberlain, 2004).

In developing critical literacy strategies, this research project focused on the fourth process of reading comprehension: “The process of examining and evaluating content, language and textual elements requires the students to move from constructing meaning to critically considering the text itself” (Caygill & Chamberlain, 2004, p. 5, emphasis added). Thinking critically “involves reading and writing beyond a literal, factual level. It involves analysing meanings, responding critically to texts when reading . . . It also involves responding to texts at a personal level” (Ministry of Education, 2003, p. 24). This process of reading comprehension also requires that students “use their own background knowledge and experience to critically evaluate the text” (Caygill & Chamberlain, 2004, p. 5), an important aspect of the research team’s definition of critical literacy (see below for full description). Ministry of Education documents also call for students to “reflect on the different social assumptions, judgements, and beliefs which are embedded in texts” ((1994, p. 12), an important aspect of examining and evaluating texts.

Although these descriptions encourage teachers to move students beyond literal and factual levels, teachers have been given little guidance on how to engage students critically with texts and how to move them beyond conventional practices that have failed many students (Comber & Kamler, 2004). This research project sought to address this gap between theory and practice.

2. Aims and objectives of the research

During the course of the research project, the participating teachers developed and implemented critical literacy strategies for guided reading (Phase 1 [P1], 2006, primary), integrated curriculum (Phase 2 [P2], 2006 and 2007, primary) and the secondary English classroom (P1, 2007).

Both the participating primary and secondary teachers sought to weave critical literacy strategies into their regular classroom practice, rather than to develop special critical literacy units of work. In this way the teachers and students became more adept at working with the strategies, as well as seeing the application of the strategies across curricular areas and texts (see Findings).

The research sought to:

- enhance the understandings and practices of critical literacy for the participating teachers

- support students in selected classes across four primary schools (and one secondary) to develop multiple strategies of accessing and interpreting texts

- document the implementation of critical literacy strategies into regular guided reading lessons (P1) and across the curriculum through curriculum integration (P2) (Beane, 1997)

- involve focus groups of students in stimulated recall interviews (SRIs) commenting on a lesson using critical literacy strategies

- collect data to chart growth of reading comprehension and reading achievement in relevant curricular areas

- produce collaboratively theorised reports of the research process and findings to share with audiences of both researchers and teachers

- inform the Bachelor of Teaching (Primary) programme at the University of Otago

- elaborate on future research directions.

Research questions

This project investigated the following research questions with regard to the development and implementation of critical literacy strategies, changes in students’ reading achievement (more broadly) and reading comprehension (more specifically), and the research process.

- What critical literacy strategies can be most effectively integrated within guided reading lessons and across curriculum areas in the New Zealand context?

- What changes were evident in students’ comprehension of texts?

- In what ways was the reading achievement of students enhanced?

- What forms of assessment enabled the team to chart student growth of critical literacy skills?

- What changes were found in students’ ability to relate texts to their lives?

- How did the research process support teachers to become more effective in implementing critical literacy strategies?

- In what ways are the research capabilities of the participating teachers enhanced?

3. Research design

Overview

The research design for this project was based on the design of the 2005 pilot project (Sandretto et al., 2006). Both the pilot project and the research reported here consisted of a supported, collaborative self-study utilising a range of qualitative data collection protocols (Loughran, Hamilton, LaBoskey, & Russell, 2004). As detailed in Tables 1–3, the research design involves collaborative working sessions and a range of data gathering methods.

Collaborative working sessions

Teacher release time allowed for the development and implementation of selected critical literacy strategies and collaborative data analysis, theorising and writing. As demonstrated in the 2005 project, we found that the working days were an integral component of the research design. The largest budget item funded teacher release days that allowed the teachers to engage in collaborative:

- discussions of critical literacy strategies and the research literature

- data analysis, using a theoretical framework developed by the research team, of the videotaped lessons and audiotaped stimulated recall interviews (SRIs) (Wear & Harris, 1994)

- examinations of pre- and post-intervention data collected on student comprehension

- theorising of results

- drafting of reports and conference presentations.

At the end of the project the teachers evaluated the research process and design, made recommendations for future research, and chronicled the benefits and challenges of participation in teacher research (see Findings).

A range of data gathering methods

The range of data gathering methods documented the research process and provided evidence of the outcomes of the research (Table 3). These included videotaped teaching episodes, stimulated recall interviews with student focus groups, audiotaped interviews with teachers, and resources to gather information on student comprehension and academic achievement. The multiple data sources across time enhanced the trustworthiness of the findings.

Phase 1: Pre-intervention data was collected from all students through methods the teachers commonly used to gauge reading comprehension—for junior primary students this consisted of running records data; for senior primary students this consisted of STAR data, and for secondary students this consisted of asTTle (Assessment Tools for Teaching and Learning) data. For the Phase 1 primary teachers, the same small group from each teacher was observed and videotaped due to the size of the project, although the teacher implemented critical literacy strategies with all students. For the Phase 1 secondary teachers, whole-class lessons were videotaped. Four lessons per teacher were videotaped during the course of the research (Table 1). In 2006, one lesson was followed by an audiotaped SRI which gives students an opportunity to comment on ways in which particular critical literacy strategies helped them engage with the texts in more personal and questioning ways, as well as indicate which strategies helped them better understand the texts, and make suggestions on ways that the teachers could further enhance their learning. The use of SRIs with student focus groups represented an innovative method in literacy research (Knobel & Lankshear, 1999). After reviewing this practice at the end of 2006, the research team decided to conduct an SRI after each lesson in 2007. Transcripts of the lessons and SRIs were produced (see Appendices 1–3 for lists of the transcripts).

Post-intervention data was collected to document the reading comprehension of all students following the methods used at the onset of the project.

Phase 2: Three integrated lessons per teacher were videotaped during the course of the research

(Table 2). Each videotaped lesson was followed with an audiotaped focus-group SRI. Transcripts of these lessons and SRIs were produced (see Appendices 1–3 for lists of the transcripts).

| Term One | Term Two | Term Three | Term Four |

|---|---|---|---|

| Two-day working session for:

individual interviews with teachers engagement with literature development of teaching strategies |

Teachers begin to implement critical literacy (CL) strategies within guided reading lessons (primary) with all students | Teachers released for two days to:

collaboratively analyse Term Two videos examine preimplementation data on student comprehension finalise data collection for remainder of research |

Teachers released for four days to:

complete analysis of Term Three videos examine pre- and postimplementation data on student comprehension theorise results draft reports of results |

| Pre-implementation data collected on all students’reading comprehension | Researcher visits support implementation of CL practices | Researcher visits support implementation of CL practices | Teachers released for one day to:

discuss research process and product |

| 1 videotaped guided reading lesson per teacher with focus group | 1 videotaped guided reading lesson with CL strand per teacher with focus group | 2 videotaped guided reading lessons with CL strand per teacher with focus groups | |

| Student focus groups complete stimulated recall interviews (2007 after each lesson) | Student focus groups complete stimulated recall interviews | Student focus groups complete stimulated recall interviews | |

| Two-day working session for:

analysis of lessons selection of teaching strategies integration into long-term planning |

Two-day session consisting of:

analysis of lessons selection of teaching strategies integration into long-term planning |

Post-implementation data collected on all students’ reading comprehension |

| Term One | Term Two | Term Three | Term Four |

|---|---|---|---|

Two-day working session for:

|

Teachers implement CL strategies through one integrated unit

Researchers visit participating teachers regularly to assist with implementation of CL practices |

Teachers implement CL strategies through one integrated unit

Researchers visit participating teachers regularly to assist with implementation of CL practices |

Four release days to:

|

| 1 videotaped social studies lesson–whole class | 1 videotaped lesson– whole class | 1 videotaped lesson– whole class | |

| 1 audiotaped student focus group stimulated recall interview | 1 audiotaped student focus group stimulated recall interview | 1 audiotaped student focus group stimulated recall interview | |

Two-day session to:

|

Two-day session to:

|

| Research question | Data source |

|---|---|

| 1. What critical literacy strategies can be most effectively integrated within guided reading lessons and across curriculum areas in the New Zealand context? | Scrapbooks/learning logs

Videotaped lessons (transcripts) Researcher journals Audiotaped discussions of research team working days |

| 2. What changes were evident in students’ comprehension of texts | Pre- and post-intervention measures of reading comprehension

(Running records, STAR, asTTle) Scrapbooks/learning logs Videotaped lessons Stimulated recall interviews (?) |

| 3. In what ways was the reading achievement of students enhanced? | Pre- and post-intervention measures of reading comprehension

Scrapbooks/learning logs Videotaped lessons Stimulated recall interviews |

| 4. What forms of assessment enabled the team to chart student growth of critical literacy skills? | Audiotaped discussions of research team working days

Outcome: Draft critical literacy rubric |

| 5. What changes were found in students’ ability to relate texts to their lives? | Pre- and post-intervention measures of reading comprehension

(Running records, STAR, asTTle) Scrapbooks/learning logs Videotaped lessons Stimulated recall interviews |

| 6. How did the research process support teachers to become more effective in implementing critical literacy strategies? | Initial and final peer interviews (participating teachers)

Audiotaped discussions of research team working days |

| 7. In what ways are the research capabilities of the participating teachers enhanced? | Initial and final peer interviews (participating teachers)

Audiotaped discussions of research team working days |

Relationship development

This project used the same methods to build and maintain relationships as the 2005 pilot project (see Sandretto, 2006; Sandretto et al., 2006). In addition, the two schools and three of the four participating teachers from the pilot project were involved in this project, so we were able to build upon the solid relationships that were established in 2005.

Parent information meetings were held at each school early in Term One. While these meetings were primarily part of the ethical consent process for the project, they also served an important function in establishing relationships with parents and whanau/family at each school. A babysitter was provided free of charge to look after children so that more parents might be supported to attend. While few parents elected to use this service, the research team has continued the practice each year. In addition, we provided light snacks. The parent information evenings provided a venue for parents to come and meet the researchers, find out about their child’s potential involvement in the project, and ask questions. An average of nine parents attended each meeting.

An important aspect of the research design, which also enhanced the development and maintenance of relationships, were the research team working days. Typically these days were held in a seminar room close to the university. The project provided morning tea and lunch. The seminar room was comfortable and held all the equipment that the research team needed to do the work together. The food was delicious and the coffee plentiful. These creature comforts contributed to create an atmosphere conducive to focusing on the work.

Ethical issues

Following the ethical procedures used in the 2005 research, the researcher sought ethical approval through a comprehensive approval process from the University of Otago Human Ethics Committee. We received ethical approval in November of 2005 (reference number 05/182). One advantage of having notice of the award of the TLRI before the end of 2005 was that we could complete the University’s ethical approval process before the onset of the project in January 2006 and be ready to begin the research at the beginning of the school year.

A paramount concern in conducting practitioner research is the protection of the rights of the participating teachers, their students, and the students’ families. These rights include issues of respect, confidentiality, and the right to withdraw from the research at any time. This research seeks to attend to these issues by implementing a “graduated process” (Clayton [Missouri] Research Review Team et al., 2001, p. 53) of informed consent for all involved to provide multiple opportunities for all participants to ask questions and clarify the roles, purposes and outcomes of the research. We initiated the research project by gaining informed consent from the participating teachers. To complement the informed consent process, the participating teachers have signed a Partnership Agreement (Appendix D) which further outlined their roles as both teachers who are submitting their professional practice to examination, and as co-researchers who are analysing that practice and disseminating the results. It is important in any practitioner research project to have regular and explicit discussions about everyone’s roles and responsibilities.

A parent information night was held at each school where the researchers and participating teachers described the project and invited discussion and questions. These information nights provided an opportunity for the researcher to initiate the development of relationships with the students and their parent(s) or guardians who would be involved in the research (see previous section). Free babysitting services were offered to support greater attendance.

After the parent information night, the participating teachers spoke with their students, provided them with the student information and consent forms, described the project, and provided them with opportunities to ask questions and discuss the project (David, Edwards, & Alldred, 2001). Students and their parent(s) or guardians (Valentine, 1999) would be asked to give informed consent for:

- general participation in the project where the students will participate in lessons using a critical literacy focus and provide pre and post-intervention data on reading comprehension (P1)

- general participation in the project where students will be videotaped in whole class lessons involving a critical literacy focus and provide data on academic achievement (P2 primary and P1 secondary)

- specific participation in the project where small groups of students will be videotaped during guided reading lessons, and will complete an audiotaped stimulated recall interview commenting on one guided reading lesson with a critical literacy focus (P1); or, participate in focus-group, audiotaped, stimulated recall interviews following whole-class videotaped lessons (P2); only the research team will have access to the videotaped lessons.

During the preparation of findings for subsequent conference presentation and publication the research team will take into consideration issues of confidentiality. We are aware that due to the co-authoring of results, it will be difficult to ensure the confidentiality of participating students. Therefore the team will be particularly attentive to issues of representation (see Bishop, 1996). Copies of all research outputs have been made available to participating schools, students, and families.

4. Findings

Introduction: Student understandings of critical literacy

Building on the findings from the 2005 project, we began by revising our understanding of critical literacy. While we have not changed the adult “definition”[3] of critical literacy (see Introduction), we have altered the student poster used for teaching (see Figure 1). This adjustment was constructed via negotiated dialogue between the Phase 1 and Phase 2 groups during working days and as a result of their experiences of working with the 2005 definition, as well as the discussions surrounding working day readings and video analysis.

We sought to enhance student understandings of critical literacy by more explicit teaching of the metalanguage of critical literacy, an important finding of the 2005 project. We found the SRIs useful in illuminating students’ understandings of critical literacy. In the stimulated recall interviews students increasingly were able to articulate their understandings of the aims and objectives of critical literacy.

A number of students demonstrated the understanding that critical literacy was about stating and supporting their opinion:

Student: Everyone comes in with their own opinion, so everyone looks at it in a different way . . .

Student: All you have to do is justify, and state your opinion and it’s not right or wrong until you’ve justified it. (StimRecall_P_22_05_07, pp. 4–5)

Students also stated that by expressing their own opinion and listening to the opinion of their classmates they were able to broaden their thinking:

Student: It helps to see different views of the same thing. Like different people see one thing in a different light.

Student: . . .you know the other ways that the other people see it so you . . . understand the other ways of seeing something. (StimRecall_W_11_09_07, p. 2)

Figure 1 Student Poster

Student: We were thinking about different points of view from Mrs Rennie’s idea and the other people’s ideas and we made up our other ideas. (StimRecall_E_ 1_05_07, p. 4)

Student: We were thinking about different points of view from Mrs Rennie’s idea and the other people’s ideas and we made up our other ideas. (StimRecall_E_ 1_05_07, p. 4)

Student: ’cause some people might have like thousands of answers to thinking what this text means. Some people have like different opinions, different answers, different viewpoints. (StimRecall_H_23_07_07, p. 6)

Student: But if you’re looking at it closer, you can kind of get opinions and new ideas of the book and things that you’d never really notice, because of critical literacy. (StimRecall_T_20_09_07, p. 3)

Students noted that the critical literacy lessons enabled them to focus on representation in texts:

Student: You see how people are represented. (StimRecall_T_26_07_07, p. 1)

Student: Yeah, or like people are represented, like if a brown person read about that Maori were badly represented, you might see the stereotype. (StimRecall_R_30_03_06, p. 3)

In other stimulated recall interviews the student focus groups highlighted a number of features of the poster, that is, the role of the author in constructing texts, what the reader brings to texts, and how s/he makes meaning from it:

Researcher: So what does critical literacy mean to you?

Student: I think it’s like not just reading the text but understanding the text.

Student: Same. Yeah, just understanding the text a bit more and going a bit deeper than just what we read. Thinking about it and stuff . . .

Student: Something that portrays an idea or an opinion or . . . inform someone maybe . . .

Student: . . . so we can think more about the text and see what we bring to the text . . . what we know about . . . what the text is about and stuff . . .

Student: Learning to go further than just reading a book or something. Like other parts of it, going deeper . . .

Student: It gives you a better understanding of the text . . .

Student: . . .You could use it to understand the characters a bit more . . . (StimRecall_T_26_07_07, pp. 2–4)

Student: I was just going to say [that critical literacy] sort of want[s] us to think about why the author’s done what they’ve done and why they could have maybe done it another way, but they didn’t. (StimRecall_P_22_05_07, p. 1)

Student: Something that you can relate to yourself . . .

Student: And if it’s influenced you and your thoughts. (StimRecall_P_24_08_06, p. 3)

Student: When you like, think about the text and how it’s constructed and who’s included and excluded . . .

Student: To expand our thinking . . . our thoughts about the text. (StimRecall_R_25_08_06, p. 2)

Other students emphasised the value of the critical literacy lessons in encouraging them to (re)consider texts and not take them at face value:

Student: . . . to like . . . question things. Like not just take things for face value. Just to question deeper. (StimRecall_P_20_03_07, p. 2)

Student 1: To be able to analyse . . .

Student 2: Um, just going deeper than just reading . . . (StimRecall_T_7_06_07, p. 1)

Researcher: What do you think critical literacy is at the moment?

Student: I think it’s going to be digging a bit deeper into the text you’re reading and trying to interpret it more that you usually would. (StimRecall_T_15_03_07, p.2)

Researcher: Why do you think we’re doing critical literacy?

Student: To see what sort of ideas we come up with when we like have to really think about what we’re reading and not just kind of take it at face value. (StimRecall_T_15_03_07, p. 2)

In the final SRIs we asked students about the value of critical literacy:

Researcher: Do you think the project should be continued?

Students: Yeah.

Researcher: Why?

Student 1: Well it helps you understand more about texts, like every text or yeah, texts in general and stuff.

Student 2: You usually just read the book, and go “Oh, that’s a pretty good book, yeah I enjoyed that.” But if you’re looking at it closer, you can kind of get opinions and new ideas of the book and things that you’d never really notice, because of critical literacy. (StimRecall_T_20_09_07, p. 3)

The research questions

1. What critical literacy strategies can be most effectively integrated within guided reading lessons and across curriculum areas in the New Zealand context?

Over the two years of the project the research team members used critical literacy strategies in guided reading lessons and across curricular areas. Guided reading is an important component of reading programmes (Ministry of Education, 2002, 2003, 2005). It consists of teachers working with small groups of students to provide focused instruction in “decoding, making meaning, and thinking critically” (Ministry of Education, 2003, p. 96). Teachers in the project found that guided reading provided an excellent opportunity to support small groups of students to focus on texts: “Only in small-group discussions do students have the opportunity both to engage in extended conversation about complex ideas and to have their understandings deepened by the ideas of their peers” (Au, Mason & Scheu, 1995, cited in Ministry of Education, 2005, p. 7).

The Critical Literacy Research Team, informed by the literature and professional development initiatives in their schools, used a description of curriculum integration called “inquiry-based curriculum integration” (Bartlett, 2005a, 2005b). Although the exact flow of events varied from school to school, typically each inquiry unit began with whole-school or syndicate planning. In these meetings the teachers would select the “Big Idea” (Wilson & Jan, 2003). The Big Idea needs to hook students in and capture their interest. The Big Idea would be something like, “The decisions of human beings influence the survival of other living things”, rather than a theme such as, “Who or what needs water?” This would allow for the opening up of possibilities.

This would be followed by an introduction of the topic to the class where the teacher would gauge what students already know. At this stage students would assist teachers with planning the unit. Students would brainstorm on the wonderings wall or use a Know-Want-Learn (KWL) to articulate what they were interested in exploring (Murdoch & Wilson, 2004). Students would participate in activities and the teacher and individual students would reflect on the learning throughout the unit, not just at the end. Assessment of student learning would also take place throughout the unit and the teacher and students could grow a class list of ways they have to “show” their learning. At the end of the unit the process would be evaluated. The underpinning philosophies of inquiry-based curriculum integration are (ideally) to:

- share curriculum and other decision making with young people

- involve teachers in decision making, rather than being driven from curriculum documents or administration

- focus more on the skills of inquiry rather than on pre-determined scope-and-sequence content guides

- take on questions that you (the teacher) do not know the answer to and that you learn alongside the students

- demonstrate relevance between school learning and wider world

- discover and strengthen links between students’ lived experiences and education

The Phase 2 Critical Literacy Research Team members from 2006 and 2007 found that critical literacy was an excellent critical thinking tool that could be applied to support students to examine any text in any subject area.

The remainder of this section discusses the critical literacy strategies used by the research team including a focus on metalanguage, use of the poster, a balance between explicit and exploratory teaching, the importance of text selection, and a focus on questioning.

Metalanguage

The Phase 1 2007 teachers from the secondary setting found that providing students with a copy of the poster for their folders, then providing explicit instruction in the metalanguage of critical literacy, enabled the students to develop greater understanding of critical literacy. This foundation of terms was built upon in subsequent lessons (see Appendix F for a metalanguage word bank).

Further, students benefited from guidance in increasing their understanding and use of metalanguage. Frequently, this might involve the teacher unpacking the poster and, at that point and throughout the lesson—depending on the teaching point—the metalanguage associated with critical literacy would be discussed.

In the stimulated recall interview, students were able to demonstrate their growing understanding of the metalanguage associated with critical literacy:

Researcher: So what do you think were the key points in [teacher’s] lesson today?

Student: Look at the composer.

Researcher: Who is the composer?

Student: The person who created it. (StimRecall_J_21_05_07, p. 1)

In the SRIs the researchers asked the students to explain what a text is. Over the two years of the project the understanding of metalanguage increased as teachers placed greater emphasis on it. For example, at the time before we placed greater emphasis on direct teaching of metalanguage, student responses to the question, “What is a text?” were typically along the lines of:

Student: It’s a . . . like a paragraph or piece of writing . . .

Student: It’s something people have said. (StimRecall_C_30_03_07, p. 4)

By the end of the two years students were responding more broadly to this question:

Researcher: What is a text?

Student 1: A way of communicating.

Student 2: Communicating ideas to other people. (StimRecall_T_15_03_07, p. 3)

The poster

The critical literacy poster that was developed in 2005 continued to evolve and serve as a fundamental tool in the delivery of critical literacy lessons (Figure 1). The poster had several roles. It provided a framework for individual lessons, acting as a point of focus and a visual reminder of the significant teaching point. The Phase 2 teachers reported that in delivering integrated curriculum the poster provided a text, or visual link, to link critical literacy and the curriculum area under study. It also gave the students a sense of continuity between a topic-based series of lessons and a specific critical literacy lens. Critical literacy was no longer an isolated lesson, but rather a thinking tool to unpack any given text. For example:

Teacher: We are going to be looking at our critical literacy, putting our critical literacy lenses on our exploration of food packages… Today we are going to look at muesli bar packages… When you first go back to your tables with your group I want you to spend a little bit of time looking at those packages and sharing with each other… the choices that people, okay the authors, the people who have designed and made these packages, what choices have they made when they constructed these packages? (Lesson_P_31_05_06, p. 1)

In this case the text is what we have called elsewhere a community text (Sandretto & Critical Literacy Research Team, 2006a) and the students are analysing it in the context of a unit on healthy eating. The teachers continued the evolution of the poster and negotiated a revision during reflection near the end of the project for 2006.

The secondary teachers did not adapt the poster developed in 2005 and revised in 2006. They found that it provided scaffolding and a visual reminder for the students. They revised the poster at the beginning of the lesson as a means to remind the students about the various critical literacy elements (the role of the author, the reader, and the “so what?”).

We noticed that the secondary students were becoming very familiar with the poster as the year progressed and able to refer to it in the stimulated recall interviews. For example:

Researcher: What things on that poster do you think match what today’s lesson was about?

Student: Choices are made about how things and/or people are represented maybe . . . StimRecall_T_26_07_07, p. 1)

Explicit/exploratory teaching—balance

The issue of balance was a key feature when discussing other strategies also. Importantly connected to the previous issue, the teachers—particularly in the Phase 2 group who were utilising wider, often theme- or topic-based curriculum approaches to delivering critical literacy— noticed there was a balance required between explicit “top-down” teaching and a more exploratory approach. The issue of explicit teaching of the metalanguage that harbours increased critical engagement with a text had been identified previously, and this continued to be an important strategy. However, with the use of what for the children were often new learning areas and topics within the Phase 2 team, this issue was extended into considering the importance of the students’ background knowledge. There were benefits to the use of an exploratory model. These included allowing children to explore their own critical meanings of a text and further potentially opening up possible interpretations that the teacher him/herself had not considered. The problem with a dominant exploratory approach was that children—who were often learning a topic for the first time—did not always have the necessary background knowledge to engage critically with a text. As one teacher often reminded the group “the children do not know what they don’t know”. Thus, Phase 2 teachers noticed that, just as Phase 1 teachers were doing with guided reading texts, a second reading of the text was often useful—the first to provide knowledge which could be investigated on a predominantly informative level, and the second when the text itself could be explored critically.

Students’ stimulated recall interviews also supported this:

Student: We do need a bit of background information and discussion to help us understand things that we’re trying to learn. (StimRecall_J_11_09_07, p. 3).

Student: Well, he normally asks like what knowledge we bring to the text, and today he asked what knowledge we bring to the author . . . it helps us to understand the text a bit more if you know about the author. (StimRecall_T_20_09_07, p. 1)

Whilst the need for explicit direction was generally not as noticeable for the Phase 1 teachers, there were similar issues. For example, the teachers and researchers identified the need for careful scaffolding in some questioning areas. Of particular interest were questions regarding who or what was included or excluded in a given text. Children would often respond in a random or irrelevant manner. Sometimes, then, it was important that direct attention was given with respect to the particular critical literacy focus for a given lesson:

Student: Um, she sort of came over and explained it more, So like I actually really knew what I was doing. There’s some teachers that just stand up front . . . most of the time I don’t normally get it [but] . . . she comes around and tells you. (StimRecall_G_15_03_07b, p. 2)

Teacher: In whose interest is the text?

Student: What does that mean?

Teacher: Who’s the text for? Who’s the text about? Who’s it benefiting? (Lesson_G_22_05_07, p. 2)

Teacher: What does the word “gospel” mean?

Student 1: Church.

Student 2: Doesn’t that like mean the opposite of like church music kind of stuff?

Teacher: So if I’m standing here and I’m preaching, I’ll preach to you about maybe . . .the Bible, in which case I’m giving you the gospel. OK the word according to the Bible. (Lesson_G_28_03_07, p.3)

Text selection

The teachers identified text selection as an important strategy. Initially, for some Phase 1 teachers this was an arduous task. However, generally, while there was obviously variation in the ease with which critical literacy strategies could be employed with any given text, the teachers found the range of texts they could apply critical literacy to increase as their understanding of critical literacy strategies developed. This was concurrent with an expressed development in the way teachers approached texts themselves and a development in their ability to question or interrogate a particular text.

As teachers’ skills became more sophisticated, the range of texts that they were willing to interrogate increased. Ideas included the use of lower-level texts for students so they could engage on a critical level without the possible burden of a difficult text. For example, Year 8 children explored gender and family stereotypes in a junior reader. Phase 2 teachers highlighted the usefulness of juxtaposing texts so that differences could be noticed and explored. For example, why might different texts on the same topic provide differences in information? Teachers were prepared to utilise wider literacies such as visual texts and illustrations as well as community texts such as flyers and advertisements.

For example, in a lesson exploring the history of segregation in the South to support lessons on To kill a mockingbird, the teacher juxtaposed photographs from the period representing black and white schools (Lesson_J_3_04_07). By the end of the second year, teachers found that they were using a wide range of texts at varying levels. Texts included movies (Happy feet), novels (Number the stars), video clips from YouTube, advertising, and so on. A number of the teachers used digital texts and increased their use of multimedia texts including blogs, wikis and so on. In the inquiry units, teachers found they made use of a wide range of texts. Students also identified that with variation in texts came opportunities for the teachers to select texts that were relevant to the students:

Student: Quite a lot of the things that [teacher’s] made us look at concern us, which kind of makes us more interested in it. (StimRecall_T_20_09_07, p. 2)

Questioning—A matter of balance

The use of appropriate questions was identified as the core strategy in developing comprehension and critical literacy skills. In this way the teachers recognized questioning as an important shared strategy between critical literacy and guided reading lessons. Across the year, and largely as a result of video analysis and collegial discussion, the teachers came to the conclusion that questioning needed to be refined and limited to focus on two to three key questions. The teachers felt the influence of adopting critical literacy strategies had greatly enhanced their range and depth of questioning and consequently the students’ responses reflected this. However, it was important not to attempt too wide a range in any one lesson and they felt exploring a narrow point in depth was both more beneficial to the students and supported the aims of the lesson.

Particular strategies within questioning were highlighted across the year. Wait time was identified as crucial and teachers became aware of the inadvertent habits they had developed to fill in any silence or “pregnant pauses” that often followed a question being posed. For example, teachers noticed they rephrased or repeated the question. Thus deliberate and conscious efforts were made to ensure waiting time was given for students to consider their responses. Another questioning strategy was the increased use of neutral responses. Several teachers noticed during analysis that their verbal responses to students’ discussion were often value laden and as such potentially inhibited a wider-ranging scope of answers. This point gained increased importance given that, firstly, students are highly attuned to offering what they think the teacher wants and, secondly, an often-stated point within critical literacy is that, generally speaking, there is no one correct answer to any given question. Much discussion was given to this issue reflecting a need to balance the idea of positive feedback with the idea of highlighting the notion that in many respects there were no right or wrong answers. The teachers’ general conclusion was to highlight the importance of neutral responses within a wider realization of the balancing act that their professional role entailed in this matter.

Students commented on the value of learning to support their answers and concurred that there were no right or wrong answers:

Researcher: Tell me what you mean by a “good answer”?

Student: Well . . . an answer that makes sense and is relevant and . . .

Student: Yeah, you can back it up.

Student: . . . prove it and stuff. (StimRecall_J_22_05_07, p. 5)

Students also commented on the types of questions used in a critical literacy lesson:

Student: He [the teacher] kind of, you know, explained the question more, rather than just reading it and expecting us to know what it means. ’Cause you know they’re pretty advanced questions . . . the way he put it kind of made it a bit easier for us to understand. (StimRecall_T_15_03_07, p. 4)

Again, the idea that dominated teachers’ responses to these issues was one of balance and the key point became one of identifying at which moment the greater weight of either explicit or exploratory teaching style was adopted. Further, this balancing act was not something merely considered for individual lessons but one that had to be juggled fluidly within lessons and conversations.

Talking atmosphere (no wrong or right answer)

A further strategy that emerged was the aim of encouraging a “talking atmosphere”. We say “aim” because it is important to note that there are a number of dynamic variables that can impact on the willingness and ability of students engaging in a discussion. However, set as a goal and accompanied with explicit teaching of management strategies for engaging in discussion, creating a climate of conversation was identified as an important and useful strategy for critical literacy.

One explicitly directed strategy was to encourage students to respond not only to the teacher but also to each other. In this way the teacher became a part of the conversation team when possible and not always its leader. Also, the rights and responsibilities accorded to the students as creators of the discussion were enhanced. Encouraging this often also required explicit guidance in constructive ways to engage in the art of discussion where there are multiple and often disputed points of view:

Teacher: If that’s what you believe and that’s what you see, then that’s what you write down. What is real in this particular image? (Lesson_G_22_5_07, p. 2)

The teachers also sought to encourage more than one answer:

Teacher: Why should there only be two answers? . . . Why should there only be one answer? (Lesson_G_22_5_07, p. 5)

Teacher: Remember what I said to you the other day. Nothing’s the wrong answer, you’ve just got to be able to back it up. Why are they good? (Lesson_G_28_03_07, p.2)

Another means to create a talking atmosphere was that of highlighting the “correctness” of students’ own opinions:

Teacher: You think that’s what they do? Nice. So that’s your opinion. Nice. Write it down. Write down your opinion. (Lesson_G_28_03_07, p.8)

In other words, in order to foster multiple readings of a text, teachers encouraged students to contribute by validating their responses.

Teachers also positioned themselves as a participant in the discussion, rather than a fountain of knowledge. In this lesson on a music video, the teacher acknowledged that the students knew more about the musician than they did:

Teacher: Yeah well there we go. You see I’m going to have to learn more about Tupac. (Lesson_G_28_03_07, p. 9)

As discussed in the previous section, wait time was very important. Phase 2 teachers found that with explicit attention to wait time students began to discuss amongst themselves in whole-class lessons.

The teachers’ contributions could encourage a talking atmosphere in other ways too. In some cases, the teacher made a statement, often contentious, to prompt student thinking and discussion. For example, after reading a short story about the junk left behind in space, the teacher asked the students to consider her friend’s reading of the story. This friend commented that “no more spacecraft should explore space because of the risk of space junk being left behind” (Lesson_P_16_08_06, p. 1). The students were then led through a discussion that encouraged them to explore their own views on that statement along with additional information to take into consideration.

In another example, the teacher drew attention to the ideas a younger class held about the moon, eliciting discussion from the older class about their own knowledge and the different ways the two classes had made sense of a text. Additionally, to enhance the multiple readings of any given text, the teacher offered his/her reading at the end of the lesson. This further served as a means to expose students to readings they might not otherwise come up with.

Teachers employed strategies such as the distribution of tokens to indicate the number of responses a student was responsible for contributing. This served both as a limit to dominant children and an encouragement for those less willing.

The secondary teachers found that with careful planning and scaffolding, group work served to help develop a talking atmosphere. Secondary students seem to feel more confident discussing the ideas with their peers first, and then reporting back to the whole class. The stimulated recall interviews supported the implementation of group work:

Researcher: Think about what [the teacher] did today to help you learn about critical literacy. What are some of the things that she did?

Student: Um . . . got us to revise a sheet that we got.

Student 2: And gave us the task to do it with, in like the groups, so we’ve got two opinions, not just your own. Not just sitting there thinking, “Oh, this is a good question, or this is a good answer”.

Researcher: Now last time you fed back that you liked group work for that reason. Do you still think it’s a valuable thing for teachers to do?

Student 3: Yeah, ’cause it gets you involved. You might be just like a person who just sits there doing work and stuff.

Student: But then you might divide it into like one person writing, one person speaking, one person drawing . . . (StimRecall_J_10_09_07, p. 6)

Researcher: What did [the teacher] do today that helped you learn about critical literacy?

Student: Put us into groups.

Researcher: Did you find that useful?

Student: Yeah. He [the teacher] let us discuss it with other people. What we thought.

Researcher: Why is it useful to discuss with other people in groups? Why?

Student: Umm . . . so you don’t just get your own idea.

Student: Other people’s ideas are important as well. So piece them together and . . . Student: . . . make a bigger idea. (StimRecall_T_26_07_07, p.4)

Student: By splitting up into groups we could all focus and then by getting everyone to explain their . . . it kind of gave us a good overview.

Student: He really put the onus on us to do the work instead of sort of just talking at us. (StimRecall_P_22_05_07, p. 5)

Another strategy that supported the development of a talking atmosphere at the secondary level was the use of a scribe. One student would take notes on the board, highlighting key points during the course of the discussion. These notes could then be distributed later to the entire class. The ideal would be an ICT tool such as a smart board.

Student: Um . . . you can’t refer back to a discussion, unless you’re recording it . . . You can’t really learn a discussion ’cause it’s gone.

Researcher: Can you think of any ways around that? That you could make the discussion more concrete for later work?

Student: Um. Teachers writing out notes and then giving you the page of notes and then go through the page and discuss about that, and then you still have the page and you can refer back to that page. (StimRecall_J_24_07_07a, p. 6)

The secondary students found that when the teacher made statements such as, “It’s just my opinion” or, “I think”, they felt more confident to contribute. This invitation for multiple answers encouraged a talking atmosphere:

Researcher: I noticed a few times he [the teacher] said that there was not [a] right or wrong answer. “This is just my opinion . . . does anyone agree or disagree?”; “Do you find that useful?”

Student: Yeah. It just means like you can . . . sort of feel free to say [what] we want, [and that he] wouldn’t sort of, like, judge you. (StimRecall_T_7_06_07, p. 4)

Resources

The development of resources was an important strategy in that it provided tools to complement the conceptual work involved. Along with the poster the teachers noted a number of other useful resources created and collected throughout the year. All of these can be downloaded from the website (http://criticalliteracy.org.nz ) and some are included here as Appendices 7–10. This site was seen to provide a community for educators in critical literacy both on the project and beyond. These resources included:

- questioning with “plastic” questions—a series of generic questions laminated on card that could be used as prompts for lesson planning or for students to choose an area to explore (Appendix G)

- a list of suggested texts; through the sharing of text discoveries and plans teachers saw the importance of developing a database of texts to aid in sharing

- A lesson plan template (Appendix H)

- A rubric for assessment (Appendix I).

2. What changes were evident in students’ comprehension of texts?

Reading comprehension can be defined as “intentional thinking during which meaning is constructed through interactions between text and reader” (National Reading Panel, 2000 2000 #520, p. 14). The findings of the National Reading Panel in the United States “suggest that text comprehension is enhanced when readers actively relate the ideas represented in print to their own knowledge and experiences” (National Reading Panel, 2000, p. 14), an explicit focus of this project.

However, as noted by Alvermann and Eakle (2003), “comprehension is only the first step toward developing a critical awareness of all kinds of texts” (p. 14), the overarching aim of this project. In addition, when engaging with new technologies, the ability to analyse the construction of texts and to consider representation in texts becomes more vital (Alvermann & Eakle, 2003; Coiro, 2003; Henry, 2006). There can be little doubt we are in an age of information far exceeding any historical precedent. The communication tools of the period we live in within the developed world make vast amounts of information accessible to vast numbers of people. To take the Internet as perhaps the most obvious of these communication tools, we can see along with this rise in information a parallel rise in misinformation. Never before has the ability to discern the accuracy or utility of information been more necessary. Such is the depth of the Internet’s reach; this skill is required of people across generations. Thus it is important that the idea of literacy envelops its wider connotations in terms of the critical comprehension of the texts we are exposed to. This is not to suggest that we are to analyse and “tear apart” every text for debate or discussion. Whilst this is certainly a necessary element of critical comprehension, deciding when this skill is required is also an important attribute of critically comprehending the information that a person is taking in.

Assessment of reading comprehension has always been fraught with difficulty (Sarroub & Pearson, 1998). Researchers have had to appease themselves with measures of “the residue of the comprehension process . . . rather than the process itself” (Sarroub & Pearson, 1998, p. 98). While researchers involved with new literacies or multiliteracies approaches to literacy instruction recommend assessment techniques such as project, performance, group, and portfolio assessment (Kalantzis, Cope, & Harvery, 2003), other researchers note that these types of assessments have been critiqued for being “too personal . . . or too time-consuming” (Sarroub & Pearson, 1998, p. 97).

The Critical Literacy Research Team found that the use of current reading comprehension assessment tools such as running records, STAR tests and asTTle did not assess the aspects of comprehension that were clearly related to text analysis. A finding that warrants further investigation is that the Year 9 focus-group class involved in the project in 2007 improved four steps in the “understanding” portion of the assessment on the AsTTle. This is a very pleasing result and was highlighted by the school’s administration for further discussion within the department. Nonetheless, there is an urgent need to develop a repertoire of assessment tools that can both inform teaching at the classroom level and, more broadly across schools, report directly on the role of text analyst.

While a standardised tool that would enable greater comparisons between cohorts of students would be valuable to have in the repertoire of assessment tools, we are concerned about the ability of multiple-choice type assessment tools to cater for the multiple readings and multiple viewpoints that we are promoting. Finally, we wish to signal a caution here that we would not like to see the development of an assessment tool for critical literacy that drives instruction (Sarroub & Pearson, 1998), and our development of a rubric started with the poster and what we were teaching, rather than with student outcomes that we sought to measure and then had to teach (see Findings, research question 4, for further discussion).

3. In what ways was the reading achievement of students enhanced?

In 2005 the Phase 1 group used running record data as their pre- and post-assessment, the outcome being mixed results overall. They concluded that the kinds of questions being asked in typical comprehension tests were inappropriate to measure critical literacy.

As a result of the 2005 findings the 2006 Phase 1 group decided to use a more standardised test, the STAR test, to try to measure critical literacy. The majority of the participants in the programme showed an increase in STAR results, with some showing marked improvements. For example, in 2007 two classes (Years 5–8) produced STAR results showing 82 percent of the students improved their stanine result or stayed the same, and for a Year 5–6 class all students either remained constant or improved. Despite these positive results, the group felt the STAR test proved an inappropriate way to measure gains. The Critical Literacy Research Team believes the assessment does not reflect the “textual analysis” aspect of comprehension which critical literacy seeks to improve. In addition, the Phase 2 teachers were using critical literacy as a critical thinking tool in inquiry/integrated curriculum lessons. Under our multiple literacies framework we consider texts quite broadly, including “reading” digital texts. Our current literacy assessment tools do not allow us to assess comprehension of digital literacies.

With this in mind the group saw the need to develop an assessment tool that reflected the intent of critical literacy. The critical literacy assessment rubric was developed with consultation and negotiation from both Phase 1 and Phase 2 groups along with advice from colleagues working in assessment. In 2007 this rubric was implemented with both Phase 1 and Phase 2 groups. A control group not involved with the project also took part in the assessment, allowing us to evaluate the accuracy and effectiveness of the rubric.

We were able to chart ways in which students’ reading achievement was enhanced through the lesson transcripts, analysing them against the key teaching points in the poster. Utilising their understanding of these concepts and through exploration of the lesson transcripts the teachers could clearly identify aspects of students’ reading that had developed across the length of the project during the year. For one, there was evidence that the children had an increased awareness and depth to relating texts to their own experiences (see Findings, research question 5).

In another example, in response to the senior journal story, “Tusk the cat” (Anderson, 2002) children demonstrated empathetic responses identifying the storyline with the experiences of others:

Student: . . . I think that most people would be able to relate to it, because if they don’t have cats or a pet then they will know someone who does. Like I think everyone would know someone who has a pet, it’s not like there is a whole group of people who don’t have pets. (Lesson_L_30_8_06, p. 4)

A further example highlights the depth of experience students demonstrated. Following the reading of a senior journal text, “Moving on” (Hill, 1998), which explores grief, children were willing to share some of their own experiences:

Student 1: [If] someone died you can’t, you can’t um, like, um, you can’t just keep him, you can’t hold onto that feeling that, that he is still there ’cause he isn’t anymore.

Student 2: When my grandad died I had to move on.

Teacher: Can you explain that in a bit more detail? How do you mean you moved on?

Student 2: Like have to move on, forget about him. (Lesson_T_26_07_06, p. 1)

Students also demonstrated an increased awareness of being able to recognise and articulate multiple viewpoints as well as consider the construction of texts and multiple messages. While interpreting a journal text about hunting the children expressed several points of view regarding people’s feelings about hunting as a sport. They could see people might see hunting as adventurous, cruel, fun, and a legitimate activity for people to engage in:

Teacher: How has he [main character] been constructed?

Student H: Um, he’s quite responsible.

Student G: I agree with [student]. And like he’s just sort of constructed, so he’s sort of takes after his dad . . . wants to take his dad’s footsteps by hunting.

Student D: Like he wants a bit of adventure . . .

Teacher: Who’s missing from that text?

Student F: The mum’s missing.

Student ?: Sisters and most women.

Student J: Vegetarians . . . I don’t think vegetarians would go hunting and killing wild animals and stuff . . . Um, well, if I was a vegetarian I know I wouldn’t go hunting. I wouldn’t go hunting anyway. Like . . . because it’s kind of . . . it would make them sad to think that people eat [animals] . . .

Teacher: All texts are constructed by people. What do you think the people who constructed this text . . . what messages did that person want us to get?

Student C: Hunting isn’t a bad thing?

Student I: Hunting could be actually just plain . . . like a hobby?

Student G: I think they [authors] might be trying to tell us that you make up your mind whether you want to do hunting or not . . .

Student E: People who go hunting aren’t actually people who like . . . want to kill animals just for fun. Like they hang their heads up on their fireplace. Like not all bad people that are murderers, they just want to go out and do hunting. (Lesson_W_24_08_06, pp. 2-6)

In a junior text, “Cousin Kira” (Cowley, 1988), the children were able to see why the main character might be feeling angry at looking after her young cousins but also discussed how the younger children in the story would be feeling (Lesson_E_8_06_06). The same group explored a text, “My name is Laloifi” (McMullin, 2005), and demonstrated an awareness of the ways in which texts can influence their thinking about cultural difference in both negative and positive ways. Through critical literacy questioning the children were also able to reflect in new ways on cultural differences within their own environment.

This example also suggests the students were demonstrating the way in which a text can influence their thoughts and actions. This development was highlighted in other instances too.

In response to a senior journal text, “Jelly-belly” (Frater, 2002), a child noted: “You can’t judge a book by its cover, like everybody is equal so you shouldn’t make fun of somebody just ’cause they, they look different or think differently from you” (Lesson_R_7_06_06, p.3). On a similar theme, other children explored issues of racism and grasped the text’s message: “Um, you can’t just judge people ’cause they are black . . . ” (Lesson_R_2_07_06, p. 5). Again, but in relation to violence, children realised the text was “showing us that we should be pacifists, like, somebody who doesn’t like arguments, or fighting or anything violent even if it’s just verbal sometimes” (Lesson_R_2_07_06, p.3). When reading a senior journal story, “The Birthday Visit” (Storer, 2005), about the experience of having relatives in prison, the group discussed several elements that encouraged them to consider other points of view:

Teacher: What do you think the author wants us to think about prisons maybe and the people in them?

Student: It’s just a place people go when they make a big mistake.

Teacher: So after you read this text . . . has there been any change in how you thought about prison?

Student: Before I read it I thought, well . . . prison would be a bad place to end up and now I think it is not so bad. (Lesson_W_23_03_06, p. 5)

Part of this increased skill in considering representation was to notice when things were misrepresented. The children continued to improve in this. For example, after looking at a journal story, “Do as the Romans do” (Cowely, 1983), on Samoa, the children were able to compare the story with other sources of information on Samoa that they had been consulting as part of a wider unit of study:

Teacher: When the author wrote this story, how did he portray Samoa?

Student B: In Samoa really it’s . . . you start school early and finish early. But in the story it must say that, that they start at the same time as we do and finish at the same time . . .

Teacher: When the author wrote this story, had he been to Samoa?

All: No.

Student C: ’cause it doesn’t sound like he has experienced anything or read something about Samoa. He doesn’t know anything about Samoa, from the book. (Lesson_T_30_08_06, p. 1)

In another example at a student voice interview a child was able to relate to where the resort his family had stayed at had misrepresented its facilities in its advertised brochures. Several teachers explored the use of advertisements as a text for examination, and again the issue of representation was prevalent. Children developed an increasing awareness of the particular approach advertisers take, noting for example the lack of imperfections in models in a Warehouse flyer advertising clothing (Lesson_R_25_08_06).

The secondary teachers involved in the project in 2007 found similar results. The following represents a brief case study of one class. This case study is representative of the other participating classes. The students in this study came from a top-stream, Year 10 class of 31 students. A focus group of six students was selected from this class to participate in the stimulated recall interviews. The focus group was a cross-representation of cultural background.

The pre-test comprised an asTTle test that was administered to the whole Year 10 class. This demonstrated that the group’s comprehension was at Level 5/6 of the New Zealand Curriculum. As part of this test, “Thinking Critically” was also assessed. This also came out at Level 5/6. This data demonstrated that this group were at a higher level than would be expected of a cohort group of the same age.

The post-test showed that there was little difference in the comprehension scores. This could be explained easily. The post-test differed from the pre-test, to meet the requirements for a project outside our school. This is unfortunate as it is difficult to make an objective comparison against the pre-test. It would be fair to say that as there was little difference, this remained insignificant in terms of the results. The “Thinking Critically” component did show an improvement in two of the students, while two remained the same and two decreased only within one grade, which is insignificant in terms of the study.

However, the students’ reading was enhanced. This was noted in the stimulated recall interviews, an integral part of the research process. After the lessons the following comments were noted that demonstrate ways that the critical literacy strategies enhanced their reading. This was demonstrated by how they felt as they were empowered as a reader. This is important as we do not just rely on the quantative data. There is a place for observation and professional judgement and it is through this that we can observe the learners’ empowerment:

Researcher: What do you think were the key points in [teacher]’s lesson today?

Student C: Just sort of like interpreting like sort of the messages that the poms [authors] are trying to like put across to the reader . . .

Researcher: What [do] you think critical literacy is at the moment?

Student D: I think it’s going to be digging a bit deeper into the text you’re reading and trying to interpret it more than you usually would.

Student F: What the author was kind of thinking when they wrote it.

Student E: Their point of view and stuff. (StimRecall_15_03_07, pp. 1-2)

Researcher: What does critical literacy mean to you?

Student A: Like think about the messages behind [the text] and like [what] the writer was thinking when they wrote it and like morals or themes, something they were trying to get across.

Student C: To be able to analyse it. Thinking about why they wrote it.

Student B: Just going deeper than just reading. Like background information and stuff . . . What you can bring to the text. (StimRecall_7_06_07, p. 1)

Researcher: What things on that poster do you think match today’s lesson?

Student: Choices are made about how things and/or people are represented maybe . . .

Student: Readers will make sense of text differently . . .

Researcher: [student] tell me what way you saw your connection . . .

Student: Well, ’cause in the thing it’s like . . . you see how people are represented. It’d be like ’cause you know how they said that it’d be picking on teenagers kind of thing [in the article on boy racers], with the cars and stuff. And like how they make choices and stuff about it . . .

Researcher: And what about you [student name]? In what way was part of the point of the lesson connected to the experiences you guys have?

Student: Well, because we all know like different things . . . We all think about texts differently, and so . . . ’cause we all had different ideas about the article today . . .

Researcher: OK. So what does critical literacy mean to you?

Student: I think it’s not like just reading the text but understanding the text.

Student: Yeah, just understanding the text a bit more and going a bit deeper than just what we read . . .

Student: Learning to go further than just reading a book.

Researcher: Do you think it’s important?

Student: It gives you a better understanding of the text.

Researcher: Do you think you would use it outside an English lesson?

Student: Probably would, yeah.

Reseacher: Can you think of some ways that you might?

Student: When you’re just reading a book in your leisure time or whatever, you could use it there to understand the characters a bit more . . . and where the writer got their ideas and stuff . . .

Student: It could help you see the other side of the story . . . you’ve got to think, you know, there’s always another side to the story and maybe look a bit deeper into that. (StimRecall_26_07_07, pp. 1-4)

4. What forms of assessment enabled the team to chart student growth of critical literacy skills?

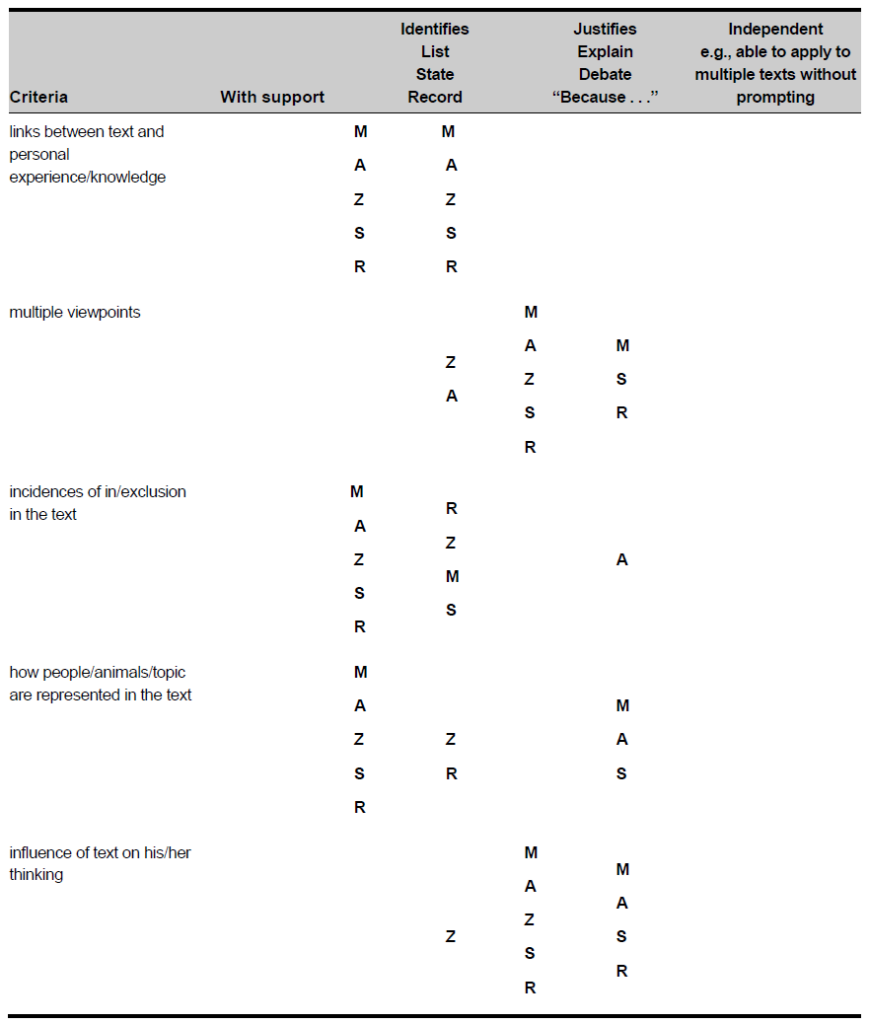

The Critical Literacy Research Team developed a rubric (Appendix I) at the end of the first year during the research team working days. We believe that the rubric represents a form of authentic assessment in that it was developed from the poster and thus measures the areas to which teachers are teaching critical literacy strategies. This rubric was trialled during the second year of the project with students who were part of the project, and at the primary school level with students who were at the same level and attending the same school but not in the project. We found the rubric to be a flexible tool to chart student understanding of critical literacy when used during a critical literacy lesson to assess student responses during discussion.

For example, we found in a Year 2/3 class that was not involved in the project that at the beginning of the year, over two guided reading lessons, all the students in the focus group were located in the “identifies” and “justifies” categories, but with little use of the critical literacy metalanguage. This same focus group at the end of the year was still located in these same categories, with two students needing support on one aspect (“how people/animals/topic are represented in the text”). Again, the students demonstrated little independent usage of the critical literacy metalangauge. This represented little or no growth in critical literacy skills (Table 4).

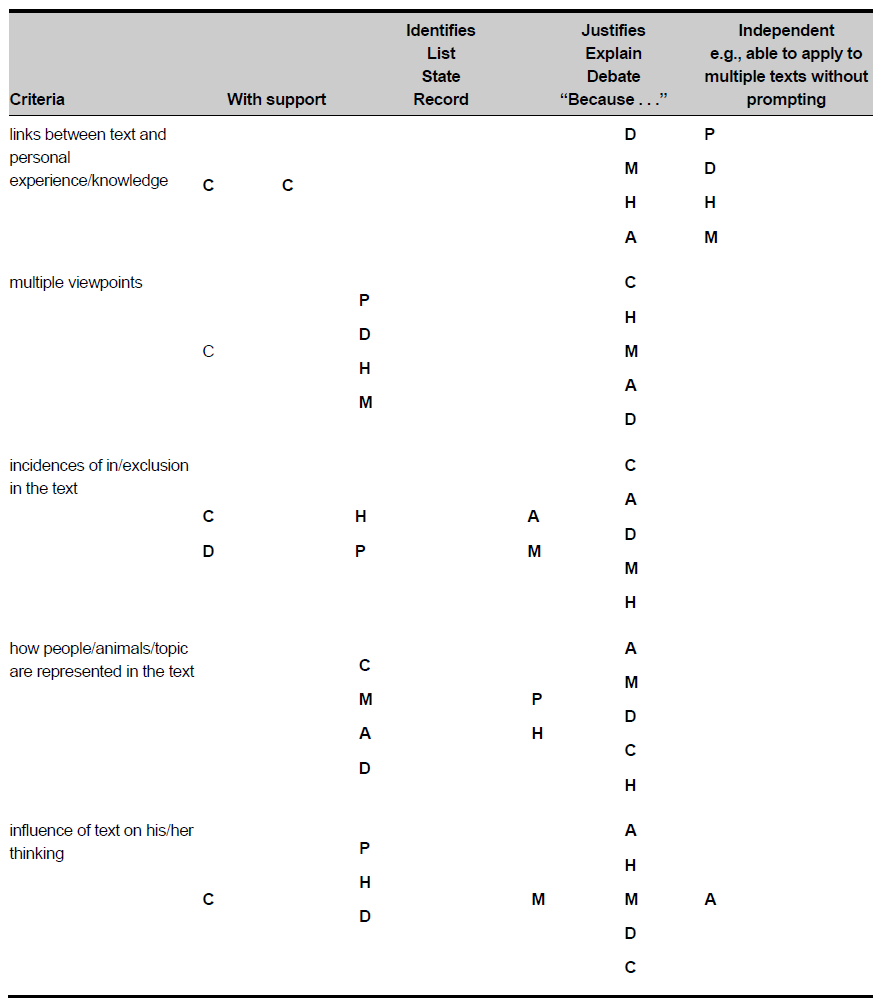

In a Year 5/6 classroom that was involved in the project the teacher found that at the beginning of the year the students were very mixed, with results from “with support” to “identifies” and “justifies”. Four students were able to independently make links between the text and their own experiences/knowledge. At the end of the year the focus group had made considerable gains in most areas. All of the students were located in the “justifies” range (Table 5). Students did not rate as “independent” for making “links between text and personal experience/knowledge” as they did at the beginning of the year—a finding that warrants further exploration.

Table 4 Rubric results Year 2/3 class not in project (Term 1, Term 4)

NB: Letters represent student initials.

Table 5 Rubric results Year 5/6 class in project (Term 1, Term 4)

NB: Letters represent student initials.

In discussion at the end of the project when we reviewed the rubric results and reflected on its use as an assessment tool for critical literacy we identified that the rubric could be used to measure student application of critical literacy to a particular text or to measure their understanding of critical literacy terms and concepts. Another important finding is that in a pre-test/post-test design the rubric was difficult for teachers to administer for a pre-test if they were new to the project. Teachers new to critical literacy who wish to use the rubric in a pre-test/post-test design may wish to have more experienced colleagues administer the pre-test. The secondary teachers in the project recommended that the rubric be revised for use at that level. Further piloting of the rubric is recommended (see Future Research).

We also found that the stimulated recall interviews were a very useful way to chart student understanding of critical literacy. These interviews gave a great deal of in-depth data that teachers could use as either formative or summative assessment. Teachers could use the stimulated recall interview schedule (Appendix K) as a means to gather data at the beginning of the year on student understandings of critical literacy that could inform their teaching, similar to the way in which the Numeracy Project uses student interviews. Although the stimulated recall interviews were not originally formulated as an assessment tool, we have ended up using it as an assessment tool to inform our practice.

5. What changes were found in students’ ability to relate texts to their lives?

Drawing on personal experience in relation to text is a commonly used strategy particularly in guided reading lessons in New Zealand schools (Ministry of Education, 2002, 2003, 2005, 2006). This tactic serves both to introduce a text, nurture interest, and aid in developing comprehension. In addition, by connecting personal knowledge and experience to texts, students may increase their achievement (Hunsberger, 2007). Hunsberger (2007) has called for “research in literacy [to] investigate this connectedness and its benefits for the academic performance of students” (p. 421). In the critical literacy project the use of connecting personal experience to a text means students can develop an awareness that there are a number of valid yet differing experiences people draw on in approaching a text. Consequently, students can acquire the idea that the sense different readers make of a text will vary. From an understanding of the validity of multiple positions readers are thus able to use their own experience to challenge, question, or defend texts.

In one lesson where students were to analyse the prospectus of a number of local high schools, one student commented just before the analysis began: “Generally, couldn’t like this critical literacy thing sway what high school we’re going to?” (Lesson_6_L_08_07, p. 2). Demonstrating an awareness that the critical literacy work they were about to embark on might impact on their personal lives.

In another lesson children used their different experiences of their grandparents to challenge stereotypes not only that were being explored in a senior text, but also that the children held themselves, to some degree:

Teacher: So what experiences have you had with old people?

Student B: Argh! Granddad and grandmas.

Teacher: Well you have got as a great example what you did with your grandfather; what have you done just recently?

Student B: Go on a boat, but he’s fun.

Teacher: But he’s old though—he can’t be fun.

Student B: He is, but he’s not old-fashioned . . .

Student J: Well, my nana normally just sits there and watches telly, but she goes on walks sometimes, and then my granddad, sometimes he plays on computer games.

Teacher: Does he? Well that’s exciting, or fun.