Introduction

The primary objective of this research project was to investigate the specific interventions that make the biggest difference to Māori students’ academic motivation and in school engagement within one Kāhui Ako in Aotearoa New Zealand. Student, whānau, school leader, and teacher perspectives were examined to understand which interventions were most successful and why. The project’s second objective was to develop a collaborative mātauranga Māori informed research partnership with Kāhui Ako leaders. This research partnership was designed to assist with developing collaborative expertise and identifying key information for guiding decision making about successful interventions. Using this information, school and Kāhui Ako leaders continue to develop and redefine their intervention programmes into the future.

Background

In 2014, the Aotearoa New Zealand government announced the Investing in Educational Success initiative with a $359 million budget to help raise student achievement (Ministry of Education, 2016). Under the initiative, schools were invited to collaborate with each other via local-school clusters called Communities of Learning / Kāhui Ako. In 2019, most Kāhui Ako had identified improving culturally responsive practice as a core objective of their community (Aim, 2019). All Kāhui Ako are led by a community leader (usually a principal or other leader in the school’s community). Specific teachers are appointed to remunerated roles, allowing them to work collaboratively with teachers and leaders across the schools or within their own school. Depending on the context of the teacher’s work, these roles are called across-school leaders (ASLs) or within-school leaders (WSLs) (Ministry of Education, 2016).

This report describes a study that was conducted in 2020 that focused on initiatives that were undertaken by Rotorua’s Te Maru o Ngongotahā Kāhui Ako. In the 2 years prior to this study, ASLs and WSLs within this Kāhui Ako had been participating in collaborative-inquiry groups to consider approaches that improved Māori student engagement (who comprise approximately 64% of the student population).

Research Context

This research project builds on and consolidates research by Webber and Macfarlane (2018), which was the first of its kind to examine Māori student success from the perspective of Māori students, whānau, community members, and teachers from one iwi (tribal) region. Their important iwi-initiated research project emphasised that success as Māori is unique to specific contexts, hapū/iwi and school communities (Webber & Macfarlane, 2018). Their research concluded that collaborations between academics and practitioners that draw upon iwi perspectives with an inquiry-focused methodology have much to contribute firstly in Aotearoa New Zealand and secondly in an international indigenous research context. The current project, conducted through a research–practice partnership (Coburn et al., 2013), involved ASLs and WSLs as researcher-practitioners working alongside academic researchers to identify the interventions, teacher practices and leadership decisions that support Māori to be successful on their own terms. Four of six ASL whakapapa to the local iwi, Ngāti Whakaue. One academic researcher has whakapapa links to Ngāti Whakaue, with the rest of the research team identifying as Pākehā.

This strengths based study focused on te ao Māori approaches and culturally responsive and relational pedagogies that support increased educational outcomes and engagement for Māori students. The researchers, in collaboration with ASLs, developed collaborative-inquiry questions to explore the interventions that resulted in positive educational outcomes for Māori students. Researchers and ASLs collectively investigated: the practices they recognised as effective and which should be sustained; the practices that were ineffective and should be discontinued; and the practices that should be modified in order to become more effective for Māori learners.

Research Design, Methodology and Analysis

This project, which employed a mixed-methods case-study design, involved gathering quantitative and qualitative data from teachers, ASLs, principals, students and whānau in the Te Maru o Ngongotahā Kāhui Ako during the 2020 school year. This study coincided with and was affected by the global Covid-19 pandemic. Data was drawn from three sources: the Kia Tu Rangatira Ai Survey, intervention stocktake interviews with school leaders, and focus group interviews.

Te Maru o Ngongotahā Kāhui Ako is comprised of 12 schools: one large secondary school, an intermediate school, three full primary schools, six contributing schools, and one special school. All schools were invited to voluntarily participate in the research. Twelve schools chose to participate in the Kia Tu Rangatira Ai Survey, school leaders from ten schools chose to participate in the intervention stocktake interviews, and school leaders/teachers from ten schools participated in focus group interviews.

The primary aim of Te Maru o Ngongotahā Kāhui Ako, was to further develop the pedagogical and leadership response to Māori students and their whānau, by improving Māori student achievement, retention, engagement and attendance. The current project contributes to the development of an evidence base for how students within this Kāhui Ako develop positive attitudes, beliefs, motivation and engagement towards school, by examining student, whānau, and teacher perspectives about “what works, and why?” The specific research questions were:

- What intervention strategies have been utilised to address inequity for Māori students within the Kāhui Ako?

- To what extent do the strategies and interventions implemented by the schools impact on Māori students’ engagement and academic achievement?

- When deliberate, culturally responsive pedagogies are enacted, what are the social and academic gains for Māori students?

Prior to this project, ASLs in the Kāhui Ako had been utilising a framework called Ngā Pūmanawa e Waru (Webber & Macfarlane, 2018) to support development of a localised curriculum. This framework identifies the eight key qualities of successful Māori students from the rohe and has formed the basis of many of the collaborative-inquiry projects focused on addressing equity outcomes for Māori students. As such, the current project Mana Ūkaipō: Enhancing Māori engagement through pedagogies of connection and belonging is built on a solid, contextually appropriate framework and employs Kaupapa Māori-informed approaches that build on positive examples of success and effective practice.

The Kaupapa Māori approach utilised in this research project meant that ethical, methodological and cultural matters were given precedence and influenced our choices regarding methods, technologies, participant preferences, communication strategies and the dissemination of the research findings (Highfield & Webber, 2021). The full research team was focused on ensuring that Māori perspectives and ideas were at the forefront of the initiative, and every effort was made to ensure tikanga Māori, te reo Māori and the contemporary realities of the participants were respected.

Kaupapa Māori theory is based on a number of key principles. Graham Hingangaroa Smith (1992) initially identified six principles or elements of Kaupapa Māori within the context of educational intervention [1]. The six elements include tino rangatiratanga (self-determination), taonga tuku iho (cultural aspiration), ako (culturally responsive pedagogy), kia piki ake i nga raruraru o te kāinga (socio-economic disadvantage), whanaungatanga (family connectedness) and kaupapa (collective philosophy) (Smith, 1997). Researchers have contributed further to these ideas over the last 30 years (Moewaka-Barnes, 2000; Pihama, Cram & Walker, 2002). This project utilised four key principles, which were essential for an authentic response to the context of this project and to ensure the mana of all participants was upheld.

Tino rangatiratanga or the principle of self-determination was utilised in the co-construction and design of the project with the ASLs, four of whom whakapapa to Ngāti Whakaue. These participant researchers were key drivers of the project and worked within and across the schools to support understanding and participation to bring about positive outcomes and ideas aimed at supporting the ongoing autonomy, self-determination and independence of Māori students.

The principle of cultural aspiration or taonga tuku iho asserts the centrality and legitimacy of te reo Māori, tikanga Māori and mātauranga Māori (Rautaki Ltd and Ngā Pae o te Māramatanga. (n.d.). Although all the documentation for the research has been in English, te reo Māori, mātauranga Māori, and tikanga Māori were used extensively in all hui with the researchers and participants. Likewise, the principle of he taonga tuku iho was a key theme in the analysis of the data because the project was aligned with, and contributed to, the aspirations of the Kāhui Ako and local hapū/iwi. The collective vision or kaupapa of this research project aimed to be of positive benefit for Māori students, their whānau and teachers. This was a relevant Māori-derived initiative that was focused on the success of tamariki Māori.

Ako Māori – the principle of culturally responsive pedagogy – was the framework used for the thematic analysis of the leadership focus-group data. It was determined that any interventions likely to make a positive difference for Māori students would be embedded within the teaching and learning practices that are inherent and unique to Māori, as well as practices that may not be traditionally derived but are preferred by Māori.

This principle of whānaungatanga was embedded within this research project. Mana ōrite relationships were established, decision making about the project aims and approaches were negotiated, and power over the interpretation of the data was shared (Rautaki Ltd and Ngā Pae o te Māramatanga. (n.d.). The views of whānau and students were given equal weight to that of teachers and researchers. The strengths-based research approach ensured that positive relationships between whānau and the school personnel were regarded as intrinsic to the success of tamariki Māori and the aspiration and purpose of Māori communities.

Each method of data collection is outlined below.

Intervention Stocktakes

The purpose of the intervention stocktake was to both investigate the interventions school leaders were selecting to resource and understand the effectiveness of those programmes in supporting Māori student success. Stocktake interviews were conducted with school principals (or another senior leader) from each school, led by the research team including ASLs as researcher-practitioners. Ten of the 12 schools participated in the stocktake interviews. All school leaders were provided with the stocktake template prior to the interview. Some principals chose to share the template with their teaching teams who helped them prepopulate the template prior to the interview. Other principals chose to spend the interview time discussing the interventions with researchers who filled in the template in a shared electronic format such as Google Docs to record the discussion. Detailed notes were taken during these conversations. These notes were member-checked by the participants and then thematically analysed using the culturally responsive and relational pedagogies that are known to make a difference for students. A copy of the stocktake template is provided as an Appendix.

The ASLs also completed the stocktake template to describe the across-Kāhui Ako interventions that were being implemented. ASL’s examined the attributes of successful programmes in and across schools, in order to understand the evidence of success, and investigate implementation challenges..

The summary of interim findings from the stocktake and the questionnaires was presented to school leaders at a hui in September. While leaders did add additional intervention initiatives during the hui, we noted that the school-based interventions changed regularly and that the data provided a “snapshot” from one point in time. We also noted that many of the interventions listed were not specifically targeted at Māori students, although school leaders identified that many Māori students had benefited from them. Many of the schools have a high proportion of Māori students on the school roll. It is therefore understandable that principals would perceive almost every intervention as one that would benefit Māori students. For example, leaders and teachers were focused on developing a localised curriculum drawing on Māori histories of the area. While this approach was important for all students who live in the local area, it also supported the mana of Māori students.

The Kia Tu Rangatira Ai Survey

This survey, developed by Associate Professor Melinda Webber (2019), was designed to elicit student, family and teacher perspectives about students motivation and engagement at school, the development of positive attitudes, future aspirations; and who their role models for success are. This project, funded by the Royal Society of New Zealand, Te Apārangi, provided nationally representative numbers of students (n = 18,996), family members (n = 6,949) and teachers (n = 1,866) who have completed the project surveys (Webber & Waru-Benson, in press). This existing data provided a comparison data set with similar schools to those in Te Maru o Ngongotahā Kāhui Ako.

The survey findings were utilised to produce individualised school reports which were presented to each school principal. Furthermore, collated Kāhui Ako reports were presented to all school leaders. The reports primarily focused on the data gathered but also provided comparison data in the form of matched Kāhui Ako results, and national average reports from the national survey. Within the current study, the survey (including separate questionnaires for students, whānau and teachers) were administered in all 12 schools with the support of ASLs. The survey was completed between February 2020 and September 2020. Data from the questionnaires were downloaded and analysed using descriptive statistics on the quantitative data (eg mean scores). Qualitative data in the open-ended questions were thematically analysed. These were analysed using a culturally responsive and pedagogical lens with a second analysis carried out to identify key themes.

Focus-group discussions.

Two focus groups (N participants = 45) formed part of the data gathering and member-checking processes for this project. The first focus group involved the research team meeting with principals and school leaders to collaboratively analyse the data gathered during the survey and stocktake phases of the project. Interim findings were presented to participants to ensure the data (gathered via online meetings due to COVID restrictions) had been understood and captured correctly, and to ensure practitioner validation. The discussion was framed around the principles of culturally responsive schooling that were evident in the data collected. The school leaders worked in groups discussing the interim findings, adding their own comments or adjusting statements they felt didn’t reflect their own experiences. Following the first focus group, the ASL team and researchers concluded that further investigation was needed to understand the pathways for Māori-medium students. Therefore, the second focus group consisted of an hour-long hui comprising 17 Māori-medium teachers and five ASLs (three of whom work in Māori-medium settings). These conversations were recorded, transcribed, and qualitatively analysed using open-ended thematic analysis to identify themes.

| Measure | N |

| Kia Tu Rangatira Ai questionnaires | 3,358 |

| All primary students (Y1–8) | 1,449 |

|

Primary students – Māori

|

896 (62%) |

| All secondary students (Y9–123) | 989 |

|

Secondary students – Māori

|

492 (50%) |

| All family/whānau members | 694 |

|

Māori whānau/family members

|

475 (68%) |

| All teachers/leaders | 226 |

|

Māori teachers/leaders

|

112 (50%) |

| Intervention stocktake interviews | 45 |

| Focus group meetings | 45 |

| All school leaders (Focus Group 1) | 23 |

|

Māori teachers/leaders

|

6 (28%) |

| All Māori-medium hui attendees (Focus Group 2) | 22 |

The project adhered to ethical principles and practices, including informed consent, protection of vulnerable students, anonymity, and confidentiality, as outlined by iwi (tribal) protocols and the University of Auckland Code for Human Ethics. Following ethical review by the team, the ethics proposal was lodged and received approval from the University of Auckland Human Participants Ethics Committee (Approval Number: 024166). The mixed-methods data collection and analyses were iterative and ongoing, as the project evolved during a pandemic.

The trustworthiness of the research process was increased through implementing practices known to enhance credibility, dependability, confirmability and transferability of findings (Nowell et al., 2017). This involved developing a partnership with school leadership, especially ASL’s, to address the fit between the participants’ and researchers’ views and how they were presented. The ASL’s were involved in the intervention audit, administration of the survey, analysis of student data and focus-group discussions. A clear audit trail of field notes gathered through both stocktake interviews and focus group meetings was an additional way to address dependability.

As noted earlier, this research project was conducted during the global Covid-19 pandemic. This was completely unanticipated. Although the methodologies remained aligned with the original research design, the findings need to be considered within the context of 5 weeks of lockdown and national and global uncertainty.

Key Findings

Findings from a triangulation of all three data sets are discussed in relation to each research question. In addition to the research questions, some incidental findings arose during analysis of the data and these are reported separately.

RQ1: What intervention strategies have been utilised to address inequity for Māori students within the Kāhui Ako?

The stocktake conversations and focus groups noted a total of 165 interventions utilised by the 10 schools which contributed data via those methods. The first part of this section outlines all interventions operating in participating schools. The second part discusses the ways that school leaders employed these interventions to address inequity in their school communities. As noted earlier, while leaders were asked to specifically discuss interventions targeted for Māori students, many of the interventions listed were designed to address the needs of all students. School leaders discussed challenges associated with inequity, but the challenges more often related to socioeconomic factors and therefore impacted students from diverse cultural backgrounds and identities.

All Interventions Operating in Participating Schools

Interventions were grouped into four themes for analysis: in-class interventions, school-wide interventions, community interventions and teacher professional learning and development (PLD). These are outlined below and addressed in more detail with respect to Research Question 2 in the next section.

In-class interventions

The stocktake across 10 schools captured 56 in-class interventions which were designed to complement learning and increase engagement in classroom activities. Of the 56 in-class interventions, 19 were centered around either the development of a localised curriculum or the integration of te ao Māori principles into the curriculum. Five schools reported visiting places of significance in the local area, including local marae. Eight schools reported a specific focus on integrating te reo Māori within the classroom and the wider school context. Two schools did not mention specific interventions designed to increase te reo Māori, although the stocktake interviews indicate it was nevertheless a part of their daily routine with students. Of the 10 schools interviewed, six schools had Māori-medium units attached. Some school leaders noted that rumaki (Māori-medium) students took leadership roles in supporting mainstream students to develop te reo Māori skills, and the learning of local whakapapa narratives. The stocktake captured 14 different literacy programmes across the Kāhui Ako, with many of the interventions having similar goals. A summary of the in-class interventions by type is provided in Table 2.

| Intervention focus | N School | N (Tot=56) |

|---|---|---|

| Localised curriculum/te ao Māori approaches | 10 | 19 |

|

Integrating te reo learning e.g., waiata, pepeha, daily karakia

|

8 | |

|

Visits to the local marae / area

|

5 | |

| Literacy development | 10 | 14 |

| STEM | 7 | 7 |

| Academic conferencing/tracking and monitoring | 4 | 6 |

| Extra tutoring programmes | 1 | 3 |

| Special-needs support | 5 | 5 |

| Play-based learning | 2 | 1 |

| Student choice | 1 | 1 |

School-wide interventions.

The stocktake also captured 85 school-wide interventions which supported students’ personal growth and development, cultural and sporting development, hauora,[2] and school transitions. The theme includes activities which could occur in the classroom but are more often enacted in the wider school environment. A summary of the school-wide interventions is provided in Table 3. While there were a range of school-wide approaches, there were two that were more broadly utilised across the Kāhui Ako: Most schools in the Kāhui offered some form of free lunch and/or breakfast; and the most common behaviour-management strategy was Positive Behaviour for Learning (PB4L) (Ministry of Education 2021).

Community-based interventions.

Stocktake documents noted 10 interventions which showed school leaders’ efforts to connect with the local community. Schools encouraged community engagement through activities such as picking up rubbish in the community, taking part in ANZAC services, kapa haka or arts-based performances, eradicating the catfish in local waterways, Matariki events, and encouraging community spirit through events such as gala days. The focus of these events often lay with encouraging a school–community partnership and forming stronger relationships with the school community. Some school leaders noted they were trying to develop a stronger relationship with the local kaumātua at a nearby marae.

| Intervention Focus | N School |

N Intervention (Tot = 85) |

| Personal growth/development | 35 | |

|

Leadership

|

6 | 11 |

|

Life skills

|

5 | 9 |

|

Behaviour

|

5 | 5 |

|

Team building

|

2 | 4 |

|

Values

|

4 | 4 |

|

International visit

|

1 | 1 |

|

Speech competition

|

1 | 1 |

| Culture and sporting | 10 | |

|

Kapa haka

|

7 | 1 |

|

Sport

|

5 | 6 |

|

Dance

|

1 | 3 |

| Transitions | 13 | |

|

Work/tertiary transitions

|

1 | 7 |

|

Between-school transitions

|

5 | 2 |

|

Additional Needs Register

|

4 | 1 |

|

Mentorship

|

2 | 3 |

| Technology | 4 | |

|

iPads and computer equipment

|

3 | 3 |

|

Access to devices during lockdown

|

4 | 1 |

| Hauora | 23 | |

|

Improving school grounds

|

5 | 10 |

|

Kai in schools

|

8 | 3 |

|

COVID-19 lockdown support

|

3 | 4 |

|

Scholarships – fees/sporting/academic

|

1 | 1 |

|

Physical/mental well-being support services

|

1 | 4 |

|

Whānau surveys

|

1 | 1 |

Teacher professional learning and development

All schools noted interventions that supported ongoing Teacher PLD. Stocktake documents noted 14 different PLD programmes for teachers operating across the 10 schools which participated in the stocktake interviews. The majority of PLD programmes were focused on ensuring teachers had the skills to teach in culturally responsive ways, e.g., observations or developing teachers’ te reo language skills.

| Professional Learning and Development | N School | N (Tot=14) |

|---|---|---|

| Teacher observations/coaching – to develop CRP | 6 | 5 |

| Te reo | 4 | 4 |

| Digital technology | 2 | 2 |

| Collaborative inquiry | 1 | 1 |

| Teaching writing | 1 | 1 |

| Teaching numeracy | 1 | 1 |

School interventions which specifically address inequity

Hauora

School leaders were focused on reducing inequity by working to improve the health and well-being of their students (Highfield & Webber, 2021). For example, leaders of schools which experience the greatest inequity discussed “kai in schools” programmes which ensured all students had access to healthy food. Stocktake documents also showed schools were committed to ensuring all students had access to interesting and interactive opportunities in terms of the physical environment. For example, investment in play options such as cycle tracks, adventure playgrounds and new physical education gear.

Technology

Some school leaders noted challenges arising from inequity around the use of digital technology. Four stocktake interviews recorded information about ensuring their students had access to devices, especially through the COVID-19-lockdown period. One school had invested heavily in digital technology in partnership with community sponsors, providing all students with an iPad for use as a normal part of their school day and ensuring teachers had PLD to support the effective use of digital technologies in the classroom. Two school leaders noted some students had limited internet access at home. One school shared they had offered free modems to families although very few families had accepted the offer. The emphasis placed on technology use within schools appeared to reflect the priorities of individual school leaders (Highfield & Webber, 2021)

Equity programmes

One stocktake interview noted a pilot equity programme run in partnership with a local trust. The equity programme provided students with opportunities to take part in various extracurricular activities such as holiday programmes and swimming lessons which they would not normally be able to access.

RQ2: To what extent do strategies and interventions in these schools impact on Māori students’ engagement and academic achievement?

Key findings related to interventions occurring in the Kāhui Ako are outlined below. The first six findings can be found under this research question. Another four key findings are discussed as incidental findings and reported on separately.

Finding 1:

Localised curriculum is a key feature for all schools and provides opportunities for genuine iwi–school collaboration and shared decision making

All school leaders who participated in the stocktake discussions showed a commitment to developing a localised curriculum, which incorporated learning about local histories, Māori role models, and local marae (Highfield & Webber, 2021). Rumaki settings were especially strong in the development of a localised curriculum. Where rumaki settings were not available within the school, collaboration with Māori ASLs was noted as being useful in developing programme content. However, data collected at the school leaders’ focus group indicated that more between school collaboration could be happening. We posed the question “Are schools sharing their resource/plans?” Responses included “no – we’re not sure why?”, “competition prevents” and “there should be a resource bank” (Artefact 5, Focus Group 1). These responses indicate that some school leaders felt there was an opportunity for more collaboration between schools, especially around the development of a localised curriculum. The sharing of resources, facilitated by ASLs, would provide support to schools which need help developing material and result in less replication of resources (Highfield & Webber, 2021).

Localised curriculum impacts positively on Māori student engagement and academic achievement through enhancing students’ sense of identity and belonging (Webber & Macfarlane, 2018). The localised curriculum provides an opportunity for students to learn using te ao Māori approaches and place-based learning. There was little evidence provided by school leaders about the academic impacts of the individual programmes, although most school leaders within a school agreed that the interventions were successful (Highfield & Webber, 2021). The stocktake captured comments such as “children now have a kete of pūrākau from our area” (Stocktake 6) and feedback from one teacher at the Māori-medium focus group noted:

I see a big improvement of them being proud of themselves, improvement about them learning identity, learning who they are, how they’re participating, and their [understanding of] te ao Māori. (Focus Group 2, Participant T1)

The development of relationships with local iwi were noted as especially important in supporting Māori student engagement. One leader shared the benefits of recently formed connections with the local marae. This had led to/involved a marae visit for students. This school leader explained, “the kids were buzzing…students that whakapapa to here got to hear stories ‘this is my home’” (Stocktake 5).

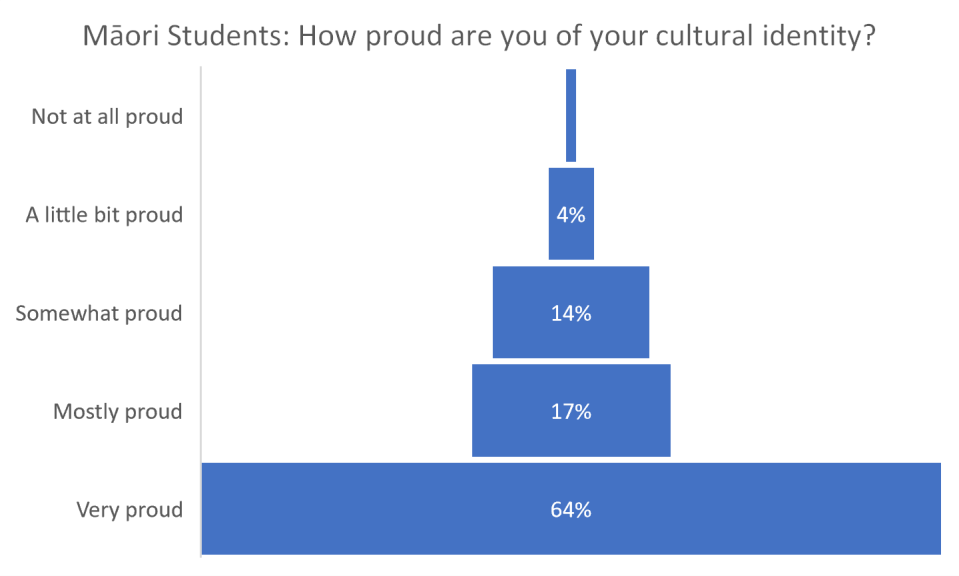

On the whole, Māori students felt very proud of their culture which may reflect schools’ commitment to a localised curriculum. Survey data showed that 60% of all students in the Kāhui Ako, and 64% of all Māori students (see Figure 1) in the Kāhui Ako, felt “very proud” of their culture. These percentages for students in this Kāhui Ako are slightly higher (although within 5 percentage points) than students from a matched Kāhui Ako (matched by demographic and urban area); although slightly lower (but again within 5 percentage points) than the national average taken from the national Kia Tu Rangatira Ai survey results.

Figure 1. Pride in identity (Māori students) within the Kāhui Ako

Finding 2:

Increasing the use of te reo Māori has a positive impact on student and whānau engagement

Many of the participating primary schools, particularly those with Māori-medium units strove “to develop fluency in te reo Māori to set up tamariki Māori for the paepae in the future” (ASL quote – Stocktake 11). Te reo was encouraged through initiatives such as kapa haka, waka ama, and Te Ipu Korero (an oral language programme for Māori-medium classes). These activities were designed to support the normalisation of te ao Māori and te reo in both schools and the wider community. School leaders discussed the importance of observing tikanga protocols and they saw their own use of te reo Māori as essential to the validation of Māori students.

Feedback from kaiako (teachers) at the Māori-medium focus group revealed te reo Māori was key to engaging with whānau and building closer home–school partnerships. One kaiako shared:

If we are looking at ways to get our whānau engaged and coming up against walls – it’s through their tamariki, it’s through their reo, through their āhuatanga, all those sorts of things. (Focus Group 2, Participant T11)

Furthermore, stocktake data suggested that the focus on te reo Māori had positively increased student engagement. For example, one leader shared that the inclusion of karakia in assemblies had led to students requesting karakia at the end of each day. This leader, who explained that children asked to lead the end-of-day karakia, noted “that pronunciation has improved. Students [are] taking [it] seriously” (Stocktake 3).

Finding 3:

Hauora of students is a consistent focus in all schools with benefits for student engagement.

All schools had initiatives in place which aimed to increase the hauora of students and to ensure they felt safe and connected at school. School initiatives included promoting positive behaviour, restorative practice, free lunches, breakfast club, physical activity, improvements to outdoor areas, pastoral care, and clubs to support special interests. PB4L was the behaviour-management framework used by the majority of schools and the stocktake captured anecdotal evidence that its use had encouraged more consistency when managing the behaviour of students within schools. However, the data also showed that students may benefit from more shared behaviour-management practices and procedures between schools in order to provide consistency throughout a student’s schooling. Feedback at the leaders’ focus group indicated a desire for PLD around behaviour management to be shared across the Kāhui.

Principals spoke candidly about the importance of ensuring students in their school (Māori and non-Māori) had enough food to eat so they were ready to learn. The Ministry of Education-funded programme Ka Ora Ka Ako, operating in most schools was kickstarted in 2020 and so little data, other than anecdotal comments, were available to record (Ministry of Education, 2020). However, anecdotal evidence suggested that the initiative was a success. For example, one principal stated “Free lunches has impacted attendance positively and has improved concentration of students” (Stocktake 7). Another principal shared that breakfast in schools ensured students have “time to interact, check in. Start the day with a full puku [stomach]” (Stocktake 8).

Furthermore, school leaders took an active role in developing a positive and engaging physical environment in their schools to maximise student motivation to attend school and feel a sense of pride in their learning environment. One primary school principal noted the upgrades to the physical environment were necessary because the previous grounds and equipment were not engaging students during break times. This principal shared:

[the changes] have been massively transformational… students’ increase in happiness at school is immeasurable. Behavioural incidents have reduced from several major issues per day to one or two per term. (Stocktake 8)

The survey results showed students and whānau appreciated the efforts of schools to provide for student well-being. In response to the question about “feeling good at school,” 81% of parents indicated that they feel their children are safe and connected at school “most” or “all of the time,” and 71% of all students, and 73% of Māori students, also “feel good at school” “most” or “all of the time at school.” These findings are almost identical to the national Kia Tu Rangatira Ai survey results.

Finding 4:

Kāhui Ako initiatives have improved transitions between schools and ASLs are focused on continuing improvement, especially in Māori-medium contexts

The stocktake showed many school leaders considered the Additional Needs Register (a resource developed by the ASLs in this Kāhui Ako) as an important tool for supporting students both within school and as they transition to other schools within the Kāhui Ako. The Additional Needs Register provides up-to-date data for teachers to plan and monitor support for students with additional learning needs. This initiative has resulted in approximately 600 students being added to the database and provided the evidence for the appointment of eight new learning support coordinators within the Kāhui Ako in 2020. Some students have benefited from additional assessment conditions which support their academic achievement, e.g., reader/writers or additional time to complete assessments.

Some schools also noted positive transition arrangements between schools, especially for students moving to the high school. The high school facilitates 2–3 enrolment days for Year 8 students, utilising current high-school students as tuākana (older students) to help teina (younger students) in the transition. Whānau are introduced to the school via evening tours and have the opportunity to interact with teachers. Other interventions which support student transitions are the technology classes shared between the intermediate and high school.

ASLs and wider school leadership noted the need to continue working towards improvements in transitioning students between schools, especially from Māori-medium settings to main stream intermediate and secondary schools. The research and ASL team investigated student pathways in the Māori-medium setting with Māori-medium teachers.

They described the challenges associated with keeping students engaged in the Māori-medium settings as students aged and their learning expectations became more complex. One secondary teacher shared:

The challenge is for us as teachers as well, because a lot of them are coming with a full basket of knowledge and we’ve actually got to work a lot harder to try and elevate that student’s learning…we could lose them because we’re not challenging them enough. (Focus Group 2, Participant T1)

Kaiako believed Māori-medium students were confident speakers of te reo and had a strong cultural identity as Māori. Kaiako hoped their students’ identity would remain strong as they progressed through their schooling. Kaiako felt that the English-medium secondary school gained students from wharekura in the region because students sought more advanced science and mathematics options. They were concerned that when Māori-medium students transitioned into the English-medium context some Māori students “felt foreign” because their te reo Māori skills were not adequately recognised (Focus Group 2, Participant T1). Furthermore, there were concerns Māori students were not adequately assessed and this resulted in them being streamed into lower classes. Streaming has long been recognised as a systemic barrier to Māori educational success (Simon, 1993).

The Māori-medium focus group provided an opportunity for kaiako to discuss strategies to improve pathways for Māori-medium students, and ASLs will continue with this work in 2021.

Finding 5:

Developing relationships with the wider school community has a positive impact on student engagement and success

All school leaders were focussed on improving home-school partnerships and recognised the importance of whānau involvement in their children’s education. One school leader discussed their success in replacing traditional parent-teacher interviews with student-led conferences and noted increased parent participation as a result of the power being shifted from the teacher to the student. Other initiatives included picnic days, food festivals or the school gala days. One principal explained the primary purpose of the gala was to strengthen home–school partnerships: “these have gone from small community events to now hundreds of students and whānau attending” (Stocktake 2). Other schools described their involvement in community activities such as picking up rubbish or participating in programmes to rid local waterways of catfish. Schools indicated that students benefitted from the programmes by learning the importance of “individual participation and giving back to the community” (Stocktake 9).

Relationship development with local kaumātua, whānau and tamariki was noted as a key indicator of success for many of the schools. As one principal shared:

Relationship is the key…We’re on our journey and we feel we’ve come a long way. We still have other steps, but feel that the connection and relationship is important, and can share what we have done at our school with others (Principal of a primary school).

This principal described an intervention which required teachers to visit different classrooms twice a week. The sessions involved introducing themselves to students, telling their own stories to illustrate who they were as people, reading stories, or working on visual art projects together. The aim of the sessions was to ensure that all of the teachers and leaders were known to all of the students. The principal felt student engagement and achievement had risen as a direct result of their focus on relationships.

Finding 6:

Ongoing teacher professional learning and development is vital for teachers’ confidence and development of culturally responsive classrooms

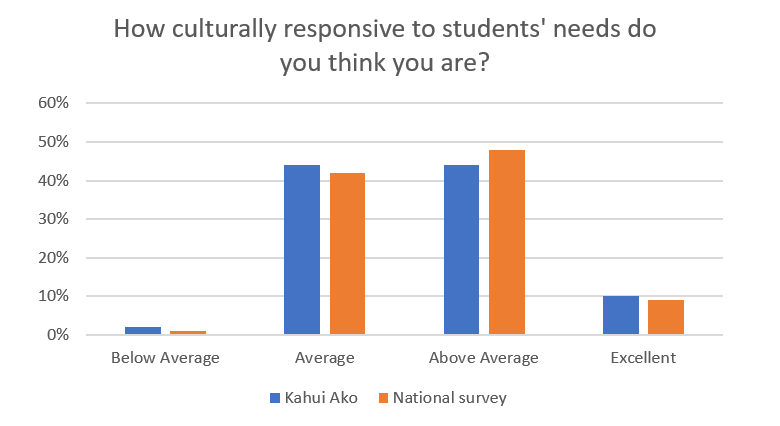

On-going PLD to support teacher’s knowledge of tikanga, te reo and mātauranga Māori was recognised as important by all school leaders. The stocktake noted 14 PLD programmes operating in the Kāhui Ako. Five of these programmes were designed to support teachers in the development of culturally responsive teaching habits through teacher observation and coaching where teachers and school leaders were encouraged to critically self-reflect on their teaching practice and implement changes as needed. In addition, four programmes were designed to help teachers develop te reo Māori language skills and knowledge. For example, one principal noted their school’s te reo PLD was supporting them to enable the school to ensure “Māori culture is valued strongly” (Stocktake 1). Teacher beliefs about their own culturally responsive practices are summarised in Figure 2.

All teachers in the Kāhui Ako believed that “they treated Māori whānau and culture with respect” “most” or “all of the time”. Teachers also agreed that “In my classroom, I respect the Māori students and they respect me” and “Māori students feel cared for” (97% for each statement). Many teachers also believed that “Māori whānau are made to feel welcome in our classrooms” (95%). In terms of areas for development, only 55% agreed with the statement “I know and teach the Māori history associated with where my school is based (e.g., hapū and iwi history).” The survey results, along with comments from school leaders show that a continued focus on culturally sustaining PLD programmes will support schools in achieving their aims for greater student engagement.

Figure 2. Teacher self-report on own cultural responsiveness

RQ3: When deliberate culturally responsive pedagogies are enacted, what are the social and academic gains for Māori students?

There were indications that employing targeted and deliberate culturally sustaining schooling approaches in the Kāhui Ako made a difference to Māori students (Highfield & Webber, 2021). Students’ positive attitudes towards school and their teachers were evident in the questionnaire results.

Approximately 78% of all students (Māori and non- Māori) indicated they enjoyed learning new things at school “most” or “all of the time”. Furthermore, 75% responded that school was fun, and 73% reported that they felt good while at school. The similar responses from both Māori and non- Māori students indicates that culturally sustaining school approaches benefit all students (Highfield & Webber, 2021). Research shows that when Māori students feel confident in their own culture, and see their culture is valued at school, they are encouraged to develop an academic identity without forsaking their Māori identity to do so (Webber, 2012; Macfarlane et al., 2014).

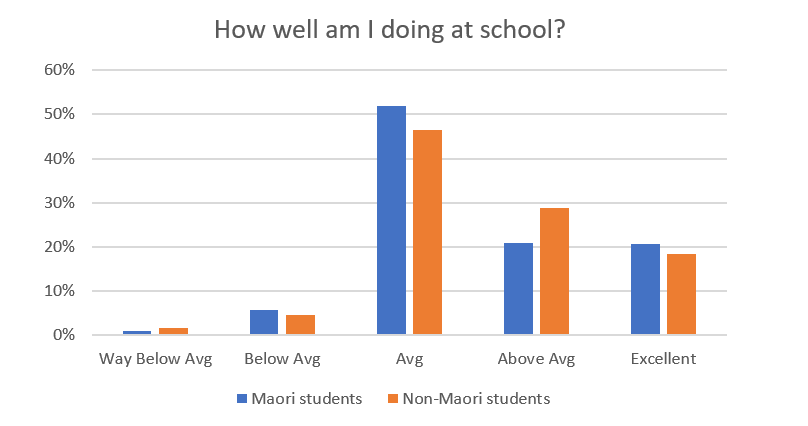

Overall, the evidence from the questionnaires suggests that students in this study experienced high social and attitudinal benefits when culturally responsive and sustaining practices were evident in their schools. While the collection of students’ academic data within the primary schools was not possible during this project, students in this Kāhui Ako – Māori and non-Māori alike – generally had positive perceptions about their own achievement (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Student self-perceptions about achievement at school

Incidental Findings

Finding 7:

Students in this Kāhui Ako may benefit from specific direction about postsecondary school educational pathways

In general, slightly fewer students in this Kāhui Ako had aspirations for university study, compared with the national survey sample and with the sample from the matched Kāhui Ako. Approximately 40% of all Māori students in the Kāhui Ako indicated that they wanted to go on to university study after finishing school, while 43% of Māori students in the national survey sample indicated this. The pattern was similar for Māori whānau – 43% of the whānau in the Ngongotahā Kāhui Ako sample indicated they wanted their students to go on to university study, compared with 52% of Māori whānau in the national sample. However, when we combined the categories of postschool activities into “tertiary study,” “get a job,” and “other,” about 10% more students (and their whānau) were planning on a tertiary pathway after school, compared to the national survey data.

It may be that students in this Kāhui Ako were more interested in non-university tertiary training. However, the anecdotal evidence suggests that students may have assumed that “going to polytech” and “going to university” are synonymous. This indicates a potential need for more deliberate articulation around the different postsecondary educational pathways, what roles they may lead to, and what prerequisites are required to gain entry (Highfield & Webber, 2021). This is consistent with previous research, which identified that students may require support in gathering information about tertiary pathways, particularly in lower decile schools (Theodore et al., 2016; Webber et al., 2016).

Finding 8:

Māori parents have high expectations for their children’s academic success and seek educational pathways they perceive will provide the greatest opportunity

Approximately 43% of all whānau indicated in the surveys that they wanted their children to go to university once they completed secondary school. There was no difference between the university aspirations of Māori whānau and non-Māori whānau in the Kāhui Ako. Kaiako in the Māori-medium focus group reported that students and whānau Māori seek educational pathways which they perceive to provide the greatest opportunity. For example, English-medium secondary schools gain students from Māori-immersion settings because they wanted access to secondary school subject options, such as chemistry, that their wharekura couldn’t provide. Furthermore, some kaiako commented that Māori whānau see English-medium schools as providing more opportunity for their children (and so children aren’t enrolled in the rumaki units). Both of these examples provide evidence that whānau want their children to succeed. These examples also indicate that Māori-medium kaiako need to clearly communicate to whānau the advantages that Māori-medium setting provide students. Likewise, they need to ensure whānau know their children can achieve success in rumaki settings. Like other New Zealand studies, our comparison of ethnic differences between Māori and non-Māori parents shows no significant difference in parental expectations of educational success (Dixon et al., 2008); ERO, 2008; McKinley, 2000).

Finding 9:

The use of digital technology during the COVID-19 lockdown period was critical for teaching, information sharing and guiding students back to school post lockdown.

Digital technology use within classrooms and regular electronic communication with school communities was noted as present in some schools. We noted high variability across the Kāhui Ako. While one primary school was utilising a range of digital tools to engage students and whānau, students and teachers in other schools had very limited access to digital technologies to support modern pedagogies in the classroom. The benefits of digital technology to student engagement and learning were most obvious when Aotearoa New Zealand was placed into lockdown in March 2020. Current literature regarding the impact of COVID-19 on education suggests that many students were disadvantaged through a lack of access and use of digital technologies (Mutch, 2021). Mutch (2021) suggests that “prior economic and social disadvantage led to a digital divide that exacerbated existing educational inequity” (p. 248). In this study, the primary school which used digital technologies as part of their everyday learning were able to quickly respond to support students in an online learning environment. Its principal reported:

On Day 2 of lockdown, 90% students are visibly engaging in online learning. Students are prepared with the materials and pedagogy and students are engaged and confident so are able to learn. (Stocktake 2)

In contrast, the majority of schools in the Kāhui Ako were relying on limited hard-copy teaching resources that had been distributed by the Ministry of Education and the broadcast of education TV (New Zealand Government, 2020). The principals of these schools were concerned for the well-being of some of their students during the lockdown Levels 3 and 4. They expressed their knowledge and understanding regarding the challenges students faced during lockdown without the structure of the school environment, or any electronic device allowing access to teacher-generated learning (Highfield & Webber, 2021). The ongoing uncertainty around the potential for future COVID-19 lockdowns points to the importance of improving access to both electronic devices for each student and reliable access to an internet connection.

Implications for Practice

Overall, our findings indicate three key implications for school practice.

1. School leaders within the Kāhui Ako need to develop a culture of relational trust

A culture of relational trust between schools is challenging because it requires Kāhui Ako to share sensitive data and good ideas, hold challenging conversations, take risks and support each other by creating safe environments (Highfield & Webber, 2021). Overall, there was good evidence of practices that provided culturally sustaining and affirming learning opportunities for all students. However, the sheer number of specific interventions or activities – 165 as a minimum estimate – suggests that schools across the Kāhui Ako are creating their own interventions/practices, rather than replicating or extending interventions/practices known to be effective for students within their school community. We noted little collaboration occurring with respect to some intervention activities, despite many schools employing similar intervention programmes and receiving substantial government funding to support them to collaborate (Highfield & Webber, 2021). Literacy, PB4L, and further sharing of resources for localised curriculum units are noted areas for development. Many schools were engaged in localised curriculum development and/or incorporation of te ao Māori approaches to pedagogy, but there was little evidence that these were well shared across the community – and indeed a number of schools indicated this as an area that they needed more support in. This was also true for a number of different interventions (within class or within school) where external “experts” were utilised for teacher PLD. We note a missed opportunity for schools to share these resources – including the cost – as well as missed opportunity to fully utilise the expertise that already exists across the Kāhui Ako.

A key discussion point that arose from the first leaders’ focus group was the consistent and unresolved issue regarding competition for students across the Kāhui Ako. School leaders were reluctant to share staff expertise, ideas or successful initiatives with each other due to competition between schools in attracting students. The potential for school closure due to falling student rolls continues to concern many school communities (Witten et al., 2003). A reluctance to collaborate contradicts a key aim of the Kāhui Ako. Principals made it clear that despite the resources committed to collaboration, school leaders were unlikely to share expertise because it was not in their best interest for the school next door to succeed (Highfield & Webber, 2021).

2. School leaders need to systematically track and monitor the effectiveness of targeted interventions/initiatives so they understand the extent to which Māori students are achieving at or above expectation.

Primary school leaders had collected minimal “hard” evidence regarding the effectiveness of initiatives – so while anecdotal evidence suggests their intervention efforts were successful there was little data to know or understand if this was in fact the case.

3. School leaders and teachers need to continue developing partnerships with whānau, iwi and community

The stocktake data and focus-group hui discussions revealed that when school leaders and teachers were knowledgeable and confident about engaging with local iwi and community initiatives, there were direct benefits for the learning opportunities for Māori students. Māori teachers and leaders were often the catalyst for this engagement with local marae and kaumātua which ensured that the opportunities were positive for all and particularly worthwhile for students.

Conclusion

The primary objective of this project was to consider the interventions that make the biggest difference for Māori students’ academic motivation and engagement in schooling. A key aspect of the project was to partner with school and Kāhui Ako leaders to develop the research and inquiry expertise of the partners and ensure the project direction aligned with the Kāhui’s future objectives. This project investigated the interventions currently used by school leaders and teachers to address inequity for Māori students and the gains for Māori students when culturally responsive pedagogies are enacted in schools and classrooms.

It was never anticipated the project would occur during a pandemic and therefore a number of the equity issues experienced by students were unforeseen. To some extent the “lockdown” context provided further insights into the need for school leaders to address the resourcing difficulties students face in relation to health and nutrition and the barriers to technological connectivity to access modern learning.

Research findings suggest school practices could be strengthened with continued efforts to share resources and knowledge between schools. Furthermore, there is an opportunity for school leaders to develop a stronger evidence base regarding the effectiveness of interventions operating in their schools. Finally, all schools discussed the benefits of engaging with local iwi and community groups. These relationships are resulting in the development of a localised curriculum and are likely to have continued benefits for all, especially Māori students.

Footnotes

- https://www.katoa.net.nz/kaupapa-maori ↑

- Hauora – The Ministry of Education (1999, p. 31) defines hauora as “a Māori philosophy of health unique to New Zealand. It comprises taha tinana, taha hinengaro, taha whānau, and taha wairua” (physical, mental/emotional, social and spiritual well-being). ↑

References

Aim, D. (2019). A critical investigation into the challenges and benefits in developing a culturally responsive framework in a mainstream Kāhui Ako | Community of Learning (Unpublished master’s thesis). Massey University.

Coburn, C. E., Penuel, W. R., & Geil, K. E. (2013). Practice partnerships: A strategy for leveraging research for educational improvement in school districts. William T. Grant Foundation.

Dixon, R., Peterson, E. R., Rubie-Davies, C., Widdowson, D., & Robertson, J. (2008). Student, teacher and parental beliefs and expectations about learning and their impact on student achievement and motivation. The University of Auckland.

Education Review Office. (2008). Partners in learning: Parents’ voices. https://www.ero.govt.nz/assets/Uploads/Partners-in-Learning-Parents-Voices-Sep08.pdf

Highfield, C., & Webber, M. (2021). Mana Ūkaipō: Māori Student Connection, Belonging and Engagement at School. New Zealand Journal of Educational Studies, 56(2), 145–164.

Kiernan, G., & Stroombergen, A. (2020). Economic impacts of COVID-19 on the Rotorua economy – Early estimates. Infometrics.

Macfarlane, A., Webber, M., Cookson-Cox, C., & McRae, H. (2014). Ka Awatea: An iwi case study of Māori students’ success. Te Rū Rangahau, Māori Research Laboratory, College of Education, University of Canterbury.

McKinley, S. (2000). Māori parents and education. NZCER.

Ministry of Education. (1999). Health and physical education in the New Zealand Curriculum. https://health.tki.org.nz/Teaching-in-Heath-and-Physical-Education-HPE/HPE-in-the-New-Zealand-curriculum/Health-and-PE-in-the-NZC-1999/Underlying-concepts/Well-being-hauora

Ministry of Education. (2016). Communities of Learning / Kāhui ako. https://www.education.govt.nz/communities-of-learning

Ministry of Education. (2020). Ka ora, Ka Ako healthy school lunches programme. Ministry of Education.

Ministry of Education. (2021). Positive behaviour for learning. Te Kete Ipurangi.

Moewaka Barnes, H. (2000). Kaupapa Māori: Explaining the ordinary. Pacific Health Dialog, 7(1), 13–16.

Mutch, C. A. (2021). COVID-19 and the exacerbation of educational inequities in New Zealand. Perspectives in Education, 39(1), 242–256.

New Zealand Government. (2020, April 8). Covid19: Government moving quickly to roll out learning from home [Media release]. https://www.beehive.govt.nz/release/covid19-government-moving-quickly-roll-out-learning-home.

Nowell, L. S., Norris, J. M., White, D. E., & Moules, N. J. (2017). Thematic analysis: Striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 16(1), 1–3.

Pihama, L., Cram, F., & Walker, S. (2002). Creating methodological space: A literature review of Kaupapa Maori research. Canadian Journal of Native Education, 26(1), 30–43.

Rautaki Ltd and Ngā Pae o te Māramatanga. (n.d.). Principles of Kaupapa Māori. http://www.rangahau.co.nz/research-idea/27/

Simon, J. (1993). Streaming, broadbanding and pepper-potting: Managing Māori students in secondary schools. Critical Perspectives on Cultural and Policy Studies in Education, 12(1), 30–42.

Smith, G. H. (1992). Research issues related to Māori education. In Research Unit for Māori Education (Ed.), The issue of research and Māori. The University of Auckland.

Smith, G. H. (1997). Kaupapa Māori as transformative praxis, University of Auckland.

Theodore, R., Tustin, K., Kiro, C., Gollop, M., Taumoepeau, M., Taylor, N., Chee, K., Hunter, J., & Poulton, R. (2016) Māori university graduates: Indigenous participation in higher education. Higher Education Research & Development, 35(3), 604–618.

Webber, M. (2012). Identity matters: The role of racial-ethnic identity for Māori students in multiethnic secondary schools. SET Research Information for Teachers, 2, 20–25.

Webber, M. (2019). Kia Tū Rangatira Ai Survey [Unpublished project survey]. University of Auckland.

Webber, M., & Macfarlane, A. (2018). The transformative role of tribal knowledge and genealogy in indigenous student success. In L. Smith & E. McKinley (Eds.), Indigenous handbook of education (pp. 1049–1074). Springer.

Webber, M., McKinley, E., & Rubie-Davies, C. M. (2016). Making it personal: Academic counselling with Māori students and their families. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 47, 51–60.

Webber, M., & Waru-Benson, S. (in press). The role of cultural connectedness and ethnic group belonging to the social-emotional wellbeing of diverse students. In T. Olsen & H. Sollid (Eds.), Indigenous Citizenship and Education. Scandinavian University Press.

Witten, K., Kearns, R., Lewis, N., & Coster, H. (2003). Educational restructuring from a community viewpoint: A case study of school closure from Invercargill, New Zealand. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, 21, 203–222.

Research project team

Dr Camilla Highfield is Deputy Dean at the Faculty of Education and Social Work at the University of Auckland. She was the Director of Team Solutions for 15 years and her research and teaching interests are in equity, leadership, and schooling improvement.

c.highfield@auckland.ac.nz

Dr Melinda Webber (Ngāti Whakaue, Ngāpuhi, Ngāti Hau, Ngāti Kahu) is Te Tumu—Deputy Dean at the Faculty of Education and Social Work at the University of Auckland. She is an Associate Professor in Te Puna Wānanga/School of Māori and Indigenous Education and Rutherford Discovery Fellow, MRSNZ. Melinda is the Co-Director of the University of Auckland–Atlantic Fellows for Social Equity, Associate Director—Woolf Fisher Research Centre and Co-Editor—MAI: The New Zealand Journal of Indigenous Scholarship. m.webber@auckland.ac.nz

Victoria Cockle is an evaluator and was a senior analyst in Office of the Vice Chancellor at the University of Auckland. Prior to this role she was a researcher and research analyst at the Faculty of Education and Social Work (University of Auckland), providing research evidence and analytics across a number of national and international education intervention programmes. She has worked alongside Ministries of Education in Aotearoa, Tonga, the Cook Islands, and the Solomon Islands. Her areas of speciality are in collaborative design of mixed-methods research and evaluation programmes. Her educational background includes a BSc in statistics and biology from the University of Auckland and she has other advanced training in psychology and linguistics.

Rachel Woods is a project assistant at the Faculty of Education and Social Work, University of Auckland. She has provided research assistance on various projects within the faculty including a summer scholarship project “A Material History of Higher Education: Mining an online archive of images of the University of Auckland in the twentieth century”. Rachel has a BA in education and history from the University of Auckland.

School leader partners

Tāmara Simpkins (Ngāti Whakaue) was the Assistant Principal at Ngongotaha Primary School and has worked in Māori Medium education for 17 years. Tāmara currently works for the Ministry of Education. Tāmara was an Across School Leader with the Ngongotahā Kāhui Ako and worked across the Kāhui Ako schools encouraging the use of cultural responsiveness and relational pedagogy principles.

Bubby Soloman (Ngāti Kakahu Tapiki) is an Assistant Principal at Selwyn Primary School. She has been teaching in mainstream education for 20 years and rūmaki for 6 years.

She is an Across School Teacher with the Ngongotahā Kāhui Ako and works across Kāhui Ako schools to lead collaborative inquiry work linked to cultural and responsive pedagogy.

Ruth Broadley is Head of History at Western Heights High School, a school that she has worked in for 27 years. She is an Across School Leader within the Te Maru o Ngongotahā Kāhui Ako. Her work in the Kāhui Ako is to facilitate the use of cultural responsiveness and relational pedagogy principles across the Kāhui Ako schools.

Katherine Mason (Ngāti Whakaue, Ngāti Ranginui) Kath is Senior Syndicate Leader at Rotorua Primary School. She has been teaching rūmaki in a dual medium mainstream school for 15 years. She leads Māori Medium in Te Maru o Ngongotahā Kāhui Ako and is one of the five Across School Leaders. Kahira Morris (Ngāti Whakaue) was Acting Principal of Western Heights High School, Rotorua and was the Kāhui Ako leader of Te Maru o Ngongotahā Kāhui Ako since it was formed in 2017. She held a leadership role at Western Heights High School for 20 years and has strong connections to the Rotorua community. Kahira is deeply committed to instructional leadership and was focused on culturally responsive and relational pedagogy in the whole school learning environment.

Appendix

Mana Ūkaipō: Enhancing Māori engagement through pedagogies of connection and belonging

Intervention Stocktake Framework

The following questions are designed to scope the current interventions occurring within and across schools in Te Maru o Ngongotaha Kāhui Ako. Interventions described in part two below could be at individual, class, school, whanau/community or Kāhui Ako level.

Part One:

| What activities/interventions have been trialled/implemented that focus on Māori student success? | What outcomes/goals were being sought for Māori students? | Is this an individual, class, school, whanau/community or Kahui Ako wide intervention? To what extent have these activities/interventions been implemented (and where)? |

To what degree do you understand those interventions to be successful or not? | How do you know and/or understand the relative success of the intervention? | Are these activities/interventions designed to be ongoing and become business as usual? How will you know when this has happened? If not, how will you know when the activity/intervention goals have been met? |

Prompt Questions:

What activities/interventions have been trialled?

- how do these relate to accentuating outcomes (i.e., direct or indirect)? Do they relate to more than one goal?

- to what extent have these activities/interventions been implemented (and where)?

Is this an individual, class, school etc intervention?

- is it implemented in the same way/same dosage across contexts?

- does this activity/intervention work in silo (or does it interact with other activities/interventions? Is it part of a train?)

- if there is an interaction – do the other elements get implemented in the same dosage, what does that look like?

To what degree do you believe these activities/interventions to be successful in achieving your goals?

- what evidence do you currently have that supports the effectiveness of these activity/interventions (and is this evidence source a suitable proxy? Is there better information that could be collected?)

- do you know if there is variability in the effectiveness across contexts (and if so, why?)

- are these activities/interventions designed to be ongoing ,and how will you know when this has happened? If not, how will you know when they have achieved their objective?

How successful do you believe the intervention (as an overarching set of activities/interventions) has been overall? What else might need to happen – and how do you know?

Approved by the UNIVERSITY of AUCKLAND HUMAN PARTICIPANTS ETHICS COMMITTEE on 27 February 2020 for three years. Reference Number 024166.