1. Introduction

In this research project, a group of teachers developed their research capability through their investigation of the use of questioning to facilitate students’ learning in mathematics. Eight teacher researchers worked in partnership with two research team leaders to analyse their own practice in order to identify aspects of questioning behaviour. During this one-year project, the teacher researchers had significant input into the shape and direction of the research. It was intended that this research project would build understanding by adding the teachers’ perspectives of the strengths and weaknesses of current pedagogical practice to the existing body of research.

The project was closely aligned with the following principles of the Teaching and Learning Research Initiative (TLRI):

- Principle 1: Strategic relevance

- Principle 2: Research relevance

- Principle 6: Partnership between researchers and practitioners

The project was conducted over the 2006 school year, in five primary schools in the Wellington area.

Report structure

Section 2 is a review of the literature. This includes a summary of the literature relating to teachers as researchers, then the literature relating to the use of questioning.

Section 3 details the research questions and the methodologies used to collect and analyse data.

Sections 4 and 5 present the project findings. These are divided into two overarching strands: findings related to teachers as researchers, and findings related to teaching and learning.

The conclusions and implications of the research are discussed in the final section.

Where appropriate, sections of this report have been written in a style that is intended to convey the parallel research activity of the teacher researchers and the research team leaders, as well as reflecting the notion of partnership that was central to the project; the “voices” of the teacher researchers and the research team leaders were equally significant to this research, so are presented side by side.

2. Literature review

Teachers developing as researchers

The nature of teacher research

Until relatively recently, there have been “prevailing concepts of the teacher as technician, consumer, receiver, transmitter, and implementer of other people’s knowledge” (Cochran-Smith & Lytle, 1999, p. 16). The creation of a knowledge base for teaching has been largely perceived as belonging in the domain of the universities’ academic researchers. This view is perpetuated by the way in which “some consider the kind of knowledge that teacher research produces to be inferior to, and less valuable than, other kinds of academic work” (Roulston, Legette, DeLoach, & Buckhalter Pitman, 2005, p. 182).

Carr and Kemmis (1986) suggest that most teachers regard research “as an esoteric activity having little to do with their practical concerns” (p. 8). Gould (2005) identified the need to reduce the “gap” that exists between research and practice in classrooms. This gap is described by Cochran-Smith and Lytle (1990):

What is missing from the knowledge base for teaching, therefore, are the voices of the teachers themselves, the questions teachers ask, the ways teachers use writing and intentional talk in their work lives, and the interpretive frames teachers use to understand and improve their own classroom practice. (p. 2)

In response to this, they advocate approaches which encourage teachers to research their own practice. Teacher research is defined as “a systematic and intentional inquiry carried out by teachers” which represents a “significant way of knowing” about teaching (Cochran-Smith & Lytle, 1993, p. 43). This means that traditional views about the relationships of knowledge and practice and the roles of teachers in educational change are challenged, “blurring the boundaries between teachers and researchers, knowers and doers, and experts and novices” (Cochran-Smith & Lytle, 1999, p. 22). Teachers can be mentored to become researchers within the context they know best, by researchers who can offer advice and support in methodologies and interpretative frameworks. Such approaches can produce opportunities for a “hybrid discourse” between practitioners and university researchers based on “democratic research relationships” (Paugh, 2004) that result in increased learning for both partners, and substantial contributions to the knowledge base of teaching.

By participating more significantly in research, teachers are able to offer fresh insights in this field, as well as develop their own skills as researchers which are more likely to have an effect on their practice: “Experienced teacher-researchers become the high risk-takers we need to develop innovative practice” (Mitchell, 2002, p. 253). This may, in turn, encourage other teachers to more closely examine their own pedagogical practice: “Teachers may be influenced to change their practices more readily by reading reports of research by other teachers … rather than university researchers” (van Zee, 1998, p. 792). Dissemination of such research findings, however, can be problematic. In their investigation of the ways such research had had an effect on schools, Berger, Boles, and Troen (2004) found it difficult to find schools where teacher research was making a difference to the teaching and learning culture of an entire school. They established a number of paradoxes which exist within schools which inhibit the effective undertaking and application of teacher research. Other difficulties with teacher research are discussed by a variety of writers: issues of power and ownership (Cochran-Smith & Lytle, 1999; Paugh, 2004), access to resources, isolation (Mitchell, 2002), and possibilities for manipulation and exploitation (Cochran-Smith & Lytle, 1993).

In New Zealand, teacher research is being encouraged by initiatives such as the Teaching and Learning Research Initiative (TLRI), which aims to foster partnerships between practitioners and researchers. Oliver’s (2005) research confirms the positive effect of the TLRI on teacher-researcher partnerships. A practical guide published by researchers Robinson and Lai (2006) to support teachers to do research in the context of their classroom also helps bridge the gap between research and practice.

How teachers use questions to guide students’ learning in mathematics

The role of questioning in a social constructivist classroom

The benefits of social constructivist approaches to teaching have been well-documented (Brooks & Brooks, 1993; Cobb, 1994; Windschitl, 1999). In a social constructivist environment, the teacher’s role is seen not so much as a “traditional” role of transmitting knowledge or providing information on a certain topic, but one in which the teacher orchestrates the environment and provides opportunities for students to create meaning through active and relevant experiences. Power and interactive relationships are continually renegotiated as students become active partners in the learning process.

The New Zealand Curriculum, Draft for Consultation 2006 says that “Learning is inseparable from its social and cultural context” (Ministry of Education, 2006b, p. 24). This statement indicates a social-cultural constructivist underpinning. In New Zealand, a growing number of teachers are exploring aspects of constructivist teaching within their classroom practice. Professional development initiatives and curriculum documents encourage teachers to embed such approaches as: considering students’ background knowledge and experiences; situating learning in “authentic” contexts; engaging students in learning conversations with peers; and encouraging them to strive for deeper understanding of core ideas. The constructivist origins of the Mathematics in the New Zealand Curriculum document (Ministry of Education, 1992), and the anticipated role of the teacher are shown in statements such as this:

As new experiences cause students to refine their existing knowledge and ideas, so they construct new knowledge. The extent to which teachers are able to facilitate this process significantly affects how well students learn. It is important that students are given explicit opportunities to relate their new learning to knowledge and skills which they have developed in the past. Factors such as out-of-school experience and language have profound effects on the way students learn mathematics. (Ministry of Education, 1992, p. 12)

However, much of the discussion about what constructivist teaching involves has been defined through drawing contrasts between this and “traditional” approaches to instruction. This is evidenced in perceptions of the teacher’s role: in a social constructivist context, the teacher’s role is talked about as questioning rather than telling, which is attributed to traditional, transmission approaches. Brooks (1990) describes the teacher’s role in this way: “… it is the teacher’s job to help students negotiate the frictions that inevitably arise in settings that provoke them to challenge ideas” (p. 70). In a social constructivist classroom, students’ misunderstandings are recognised by the teacher, made explicit, and worked on, whereas a teacher with a transmission orientation is likely to see students’ misunderstandings as the result of failure to grasp what was being taught and seek to remedy this by reinforcing the “correct” method (Askew, Brown, Rhodes, Wiliam, & Johnson, 1997; Brooks, 1990).

Exactly what constructivist teaching looks like in the classroom and how the teacher’s instructional strategies should be modified, is essentially unclear and idealised. Windschitl (1999) notes that superior pedagogical skills are required by teachers in a constructivist classroom and describes the difficulty of the task:

Crafting instruction based on constructivism is not as easy as it seems. Educators struggle with how specific instructional techniques … fit into the constructivist model of instruction”. (p. 753)

McClain and Cobb (2001) described certain socio-mathematical norms that reflect and enhance constructivist approaches to learning in mathematics classrooms. These norms include such expectations as students explaining and justifying their reasoning and their attempts to explain being valued, and students listening to and attempting to understand others’ explanations.

Social constructivist approaches to the development of mathematical thinking view the learner as actively engaged in building mathematical thinking within their social context (Carpenter, Fennema, & Franke, 1996; Stigler & Hiebert, 1998; Windschitl, 1999). Discourse is an important aspect of mathematics classrooms which fosters student enquiry and explanation of solution methods (Cobb, 1994; McClain & Cobb, 2001) and the teacher’s role is defined by ways in which the teacher initiates, guides, and intervenes in this process. The use of questioning is a key strategy in providing such guidance; it establishes a means by which learners can make links to prior knowledge, develop their thinking, and explore new possibilities.

Boghossian (2006) describes the tension that exists between constructivist ideas and the “Socratic pedagogy”.[1] There is likely to be a similar tension between teacher questioning and constructivist approaches in the classroom as teachers encourage learners to discover and explore established “truths” about subject matter. Myhill and Dunkin’s (2005) research concluded that, despite a national initiative in the United Kingdom that promoted greater interactivity between teacher and students, “teachers use questioning to maintain control and to support their teaching, rather than pupil learning” (p. 415).

How, then, does a social-constructivist approach to teaching in a mathematics classroom have an effect on such fundamental pedagogical practices as questioning?

Research into questioning

Of the many skills that are required for effective teaching and learning, one core skill is questioning. Classroom questions may be implicit or explicit. A question is “a sentence worded or expressed so as to seek information”, or “a problem requiring an answer or solution”, according to the Concise Oxford Dictionary (Allen, 1990, p. 980). In the classroom context, questions might be expressed as “Tell me more” or “What comes next in the pattern?”. Teachers spend much of their time asking questions, reportedly one to two every minute (Gall, 1971; Wragg & Brown, 2001). In the classroom, questions and questioning are pervasive (Hyman, 1974).

Several intense reviews of questions and questioning occurred in the 1970s and 1980s. However, the 2001 edition of the Handbook on Research on Teaching (Richardson, 2001) gives only two index references: one to higher education and the other to reading comprehension. This receding interest was also reflected in the Handbook of Research on Teacher Education (Houston, Haberman, & Sikula, 1990; Sikula, Buttery, & Guyton, 1996) neither of which contains any index entry for questions or questioning.

A comprehensive review by Doenau (1987) portrayed research evidence as inconsistent across each of four main areas of investigations: questioning frequency, relationships between cognitive features of questions and student achievement, relationships between higher order questioning and student achievement, and teacher-training experiments. While Doenau concluded that the research conducted since the 1970s had produced no conclusive evidence about the correlates of effects or questioning frequency, he noted Nuthall and Church’s (1973) findings that “teaching content through a strong reliance on questioning was more effective than teaching it predominantly through information” (cited in Doenau, 1987, p. 410). Recent investigations in this field (Livdah, 1995; Nathan & Knuth, 2003) have not necessarily treated questioning as an isolated technique, but have incorporated it into research that examines effective teaching practices, or classroom discourse in general.

Links between questioning and learning have been explored by a number of writers in different contexts. Chuska (1995) promotes appropriate teacher models of questioning to assist students in developing their own questions to promote learning, and also aid their metacognitive processes:

Questions are fundamental to teaching because they encompass the three central components for effective teaching; they provide information: they help students connect that knowledge to previous and subsequent learning; and they take students to the highest levels of learning. (Chuska, 1995, p. 7)

Fraivillig, Murphy, and Fuson (1999) highlight the importance of the teacher’s role in intervening to advance students’ thinking in mathematics. Their framework points to the importance of questions in eliciting, supporting, and extending thinking. In New Zealand, mathematics curriculum documents highlight the role of teachers’ questioning in scaffolding students’ learning:

“Good” teacher questions expand and extend students’ thinking by encouraging them to seek their own solutions to problems. Open questions that stimulate discussion reveal students’ thinking to teachers and are useful for diagnosing learning needs. (Ministry of Education, 1997, p. 22)

Many writers suggest that higher level questions produce deeper levels of learning (Gall, 1984; Marzano, Pickering, & Pollock, 2001; Redfield & Rousseau, 1981). A number of studies (Gall, 1984; Perry, VanderStoep, & Yu, 1993; Stigler & Hiebert, 1999; Wragg, 1993) have highlighted the low proportion of “high-level” questions to “low-level” ones when questions are categorised according to taxonomies such as those devised by Bloom (1956). Fraivillig et al. (1999) found that teachers used a higher frequency of supporting strategies when teaching mathematics, but attempts to elicit and extend thinking in students were less frequent. However, the link between higher level questions and deeper learning is tenuous and disputed by researchers such as Dillon (1988) who argues that the supposition that “higher order” questions stimulate higher levels of student thinking has no empirical evidence. Kawanaka and Stigler (1999) found that higher order teacher questions did not necessarily promote higher order responses by students.

Several writers have examined how patterns of questioning develop within the classroom context. Much classroom discourse is thought to be characterised by a pattern of Initiate, Respond/Reply, Evaluation/Feedback (Cazden, 1988; Mehan, 1979) where the teacher initiates, a student responds, then the teacher gives the student evaluative feedback. This pattern places the teacher in a central role and acts to test a student’s knowledge, rather than to encourage them to elaborate on their ideas or to extend their thinking. Other patterns described include “funneling and focusing” (Wood, 1998), and the “reflective toss” (van Zee & Minstrell, 1997) which can act to transfer responsibility for learning from the teacher to the learner.

International comparative studies, such as The Third International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS) (Stigler & Hiebert, 1999), have suggested that cultural differences exist in pedagogical practices such as questioning. The accumulated research has occurred primarily in three national systems—Australia, England, and the United States—that feature primary school classroom practices that differ in subtle though significant ways from those in New Zealand. A key difference is that for several decades, New Zealand primary classrooms have incorporated effective small group teaching strategies, reflecting a child-centred approach to teaching and learning.

Much of the recent focus in New Zealand education has been on effective pedagogy (Alton-Lee, 2003; Anthony & Walshaw, 2007; Hattie, 2003; Ministry of Education, 2006b). The synthesis of research by Alton-Lee (2003) describes questions and prompts as elements of “quality teaching”, forming an important aspect of pedagogy which supports students’ task engagement (p. 74), and serving to “provide scaffolds to facilitate student learning” (p. ix).

Many professional development initiatives have focused on pedagogical approaches, aligning classroom practices with research findings about teaching and learning. In professional development programmes, such as the New Zealand Numeracy Development Project (Ministry of Education, 2006a), teachers have been encouraged to use questioning to support students’ strategic and higher order thinking. Many teachers participating in such professional development have reported changed pedagogical practices within their mathematics teaching (Higgins, 2002; Irwin, 2003; Thomas & Ward, 2002). Within the context of mathematics teaching and learning in New Zealand, research has explored students’ discussion with their peers (Thomas, 1994). In relation to the New Zealand Numeracy Development Project, patterns of teacher–student interactions have been described (Higgins, 2003), and discourse used in mathematics has been explored (Irwin & Woodward, 2005). What is not known, though, is how the professional development has influenced the kinds of questions teachers are asking, how frequently teachers are asking questions, and the kind of thinking that is informing the process of formulating and selecting questions.

Methods of research into questioning

A number of supporting texts and professional development programmes related to teacher questioning have presented improvement in questioning practices as a technical matter which takes practice: “… good questioning is both a methodology and an art; there are certain rules to follow.…” (Ornstein & Lasley, 2000, p. 184). In New Zealand, lists of scaffolding questions to pose at various stages of the problem-solving process are available to teachers on the Ministry of Education’s mathematics website (http://www.nzmaths.co.nz). However, it has also been argued that while furnishing teachers with a list of possible questions may give them a starting point, the most effective questions cannot be pre-planned, and must occur in response to a student’s action or idea (Jacobs & Ambrose, 2003). Formulating questions within a lesson is a complex process driven by a range of variables, and analysis of this process requires more than categorising and counting by researchers: “Real insight into questioning needs to take on board contextual factors which are too subtle for the classification systems to handle” (Kerry, 2002, p. 71).

Up until now, categorisations of teachers’ questions have predominantly been carried out by researchers who focus on only a selection of the questions asked by teachers during a lesson. Some research has allowed for categorisation of questions by general intention rather than “type” (Morgan & Saxton, 1991), allowing for a focus on the function of a question rather than form (Cazden, 2001). Perry, VanderStoep, and Yu (1993) coded questions about addition and subtraction asked in 311 lessons in Japan, Taiwan, and the United States. They deliberately excluded questions they deemed non-mathematical or questions that were asking for agreement. Vale (2003) devised question categories to accommodate the question types teachers nominated they used most often. The teachers in this study also indicated the type of question they would like to ask more often. Other researchers have observed “expert” teachers and synthesised how questions can be used in mathematics lessons to develop students’ thinking (Fraivillig et al., 1999; Jacobs & Ambrose, 2003). In all of these cases, many questions asked in a lesson were excluded from the research.

A limitation of the research to date is the lack of investigations that report teachers’ views. A review of comprehensive research syntheses (Houston et al., 1990; Richardson, 2001; Sikula et al., 1996; Wittrock, 1986) did not reveal any studies deeply grounded in teachers’ perspectives. Much of the research on teachers’ questioning has been synthesised from data gathered by researchers observing in classrooms. The existing knowledge base reflects a “looking from the outside in”. A search of the literature located studies that reported teachers’ questions and questioning, but few investigations were identified that looked from the “inside out”. Walsh and Sattes (2005) identify a mismatch between teachers’ perceptions of their questioning practices and the practices observed by researchers. Perhaps this mismatch has occurred because the research has not accurately reflected the complexity of questioning practices from the perspective of the teacher. Little has been documented about the ways in which teachers view the role and formulation of questions, nor how questioning is shaped by contextual factors within a mathematics lesson—in the “reflection-in-action” mode (Schön, 1983). The factors that influence teachers’ decision-making processes when framing and selecting questions are also largely unexplored.

3. Research methodology

Aims, objectives, and research questions

The research aim for this project was developed from the research team leaders’ shared interest in observed numeracy teaching practice where questions clearly dominated the teacher–student interactions. The principal aim was for a group of teacher researchers to collaborate with the research team leaders to investigate primary teachers’ questioning in mathematics to facilitate student learning and achievement.

The project had two strands that were closely interwoven by the involvement of teachers as partners in the research team. One strand focused on building research capability of teachers. The capabilities arose from within the school context by the participation of teachers as full members of the research team (TLRI Principle 6: Partnership between researchers and practitioners). This built upon New Zealand-based research by adding the teacher’s voice, of which little has been heard until now (TLRI Principle 2: Research relevance).

Capability building objectives were to:

- create opportunities through which experienced teachers can develop a greater capacity and capability for engaging in and undertaking quality research

- conduct research in the context of schools and classrooms in order to “look from the inside out”

- demonstrate methodological capacities that arise from teachers’ existing skills, strategies and thinking, through which the knowledge base of teaching embedded in teachers’ everyday work can be made explicit.

Related key questions addressed were:

- What support is needed to enable teachers to research effectively in the context of their classroom?

- How do teachers view their role within a research team?

- How does engaging with the process of research help teachers to improve their teaching practice?

- To what degree do teachers’ interpretations of their findings align with current research?

- How does teachers’ involvement in research affect their understanding of the relationship between research and practice?

The second strand was focused explicitly on substantive aspects of teachers’ views “from the inside out”. The project sought to build understanding based on the teachers’ perspective of the strengths and weaknesses of current pedagogical practice (TLRI Principle 1: Strategic relevance). It was intended that the outcomes would increase potential for improving student achievement based on teachers’ insights into their own teaching practices. The objectives that focused on teaching and learning were to:

- identify the various kinds of questions teachers use in mathematics

- explicate teachers’ thinking about the use of questioning during lessons

- describe patterns of teachers’ questioning within mathematics lessons

- identify barriers which inhibit the use of questioning

- examine conditions that support effective use of questioning.

Related key questions addressed were:

- How do teachers categorise questions they ask during a numeracy lesson?

- What were the teachers’ purposes behind these questions? y What informed teachers as they formulated questions during lessons?

- How does the process of devising common question categories within a team impact on teachers’ thinking?

- Can the effective use of questioning be defined, and if so, what might this look like?

- What are the factors that support teachers to use questions effectively, and what can hinder this?

Research design

This project drew on methodologies established in the field of action research (Carr & Kemmis, 1986) where researchers aim to improve “their own educational practices, their understandings of these practices, and the situations in which they practice” (p. 180). The teacher researchers were encouraged to act as reflective practitioners (Schön, 1983) and contribute to formulating their own interpretive frames (Cochran-Smith & Lytle, 1990) to make sense of the data gathered. Datagathering methods were chosen to enable teachers to have maximum control over the process, and were responsive to the direction of the project as it evolved with input from the teacher researchers over the year, reflecting a grounded theory approach, such as that described by Strauss and Corbin (1998).

Over the course of the project, two sets of data were collected. While the teacher researchers gathered the data that were to inform the examination of questioning, the research team leaders collected data relating to the teacher researchers’ involvement in the research process. The data gathering methods used to track the teacher researchers’ experience of their involvement in the research, and to yield background information about the teacher researchers, were designed as research team leaders identified a need for them.

Selecting teacher researchers

During the formulation of the research proposal, the research team leaders approached teachers with whom they had established professional relationships. These relationships varied in nature; one research team leader had worked with several of the teacher researchers in her role as a numeracy adviser, while the other research team leader and one of the teacher researchers had worked alongside one another as advisers. Each of the teachers had recently participated in a common in-depth professional development programme: the Numeracy Professional Development Projects (Ministry of Education, 2006a). This meant that each had explored common ideas about mathematics education and effective pedagogical practices. From the research team leaders’ observations, they believed that the teachers had incorporated many of these ideas into their practice and that their classrooms reflected constructivist principles (Windschitl, 1999). The teachers had also demonstrated a willingness to share and examine their practices.

Each of the eight teachers was keen to participate in the research, and they were all respected members of their teaching communities; several were lead teachers of numeracy in their schools. The teachers taught at a variety of year levels, and were drawn from urban schools in communities with varied socioeconomic backgrounds. The schools ranged from decile 1 to 10;[2] one teacher researcher was from a decile 1 school, one from a decile 2 school, one from a decile 8 school, and four teacher researchers taught at decile 10 schools. Two of the teachers who had originally agreed to participate in this project withdrew before the project began because of changes in their teaching responsibilities.

Establishing the research team

At the introductory meeting of the research team, the teacher researchers met for the first time. The roles of the teacher researchers, the research team leaders, and the research consultant were clarified. The research aims for the project were shared, and interview questions were composed with the teacher researchers.

The teacher researcher who had undertaken a trial of the research methods described her experience of the data gathering and analysis processes. These processes were discussed by the team, and instructions for the “F-sort” (Miller, Wylie, & Wolfe, 1986) data categorisation method were presented (see Appendix A). This method allowed teachers to freely generate their own categories for their questions, and provided access to the teachers’ ideas and language about categories of questions from the outset of the project. The team members then familiarised themselves with the method by carrying out a sorting activity in small groups. The teacher researchers were familiarised with the “notetaker” cassette recorders that they would use to audiotape their lessons. The proposed timetable for the first cycle of data gathering and analysis was distributed.

Gathering the data

Table 1 shows the data that were gathered during the project by the teacher researchers and the research team leaders. The data collected by the teacher researchers related to their use of questioning; data collected by the research team leaders was to do with the teacher researchers’ experience of the research processes, as well as what the teacher researchers were learning by analysing and reflecting on their teaching practices.

| School terms | Teacher researchers | Research team leaders |

| Term 1 | Data from the trial:

|

Data from the trial:

|

| Term 2 |

|

|

| Term 3 |

|

|

| Term 4 |

|

* Some of the questions in the final questionnaire, “Reflecting on your

involvement in our research project”, were adapted from Oliver (2005)

For the purposes of this report, excerpts from the original proposal and the quarterly milestone reports have been included. Team emails have been referred to, as well as quotations from the research team leaders’ ongoing reflection journal.

In this part of the report, the parallel research activity of the teacher researchers and the research team leaders are presented side-by-side. This is intended to reflect the notion of partnership that was central to the project; the “voices” of the teacher researchers and the research team leaders were equally significant to this research. Later in the report, in Section 4, quotations from the research team members will illustrate their perspectives of these processes.

Data gathering process

| Teacher researchers | Research team leaders | ||

| There were two cycles of data gathering for the teacher researchers, each taking five days and occurring in each of the middle two terms of the school year. A timetable was developed for the research team to ensure that the transcribing, analysing, and interviewing components were synchronised for each teacher researcher, and also that the research team leaders interview schedules were manageable. Each teacher researcher was required to record two consecutive lessons, and choose one to analyse. After the second lesson the teacher researcher sent their audiotape to be transcribed; some audiotapes were couriered while others were collected by the research team leaders for delivery to the transcriber.

The transcription was returned to the teacher researcher two mornings later to enable them to analyse their lesson while it was still relatively fresh in their mind. At the end of the second day of analysis, the teacher researcher discussed their findings with one of the research team leaders in a semi-structured, one-to-one interview (Denscombe, 1999). To enable the teacher researchers to have maximum control over the data-gathering process, each teacher researcher worked independently to set up a video camera which remained in one position throughout the lesson, and placed a “notetaker” cassette recorder with built-in microphone, around their neck. Teacher researchers themselves were responsible for setting up the technology and the recording procedures, and this ensured ownership of the process—no one else was “present” in their classroom. The teacher researchers were encouraged to introduce the video camera to the classroom environment prior to the actual recording days, to help reduce the impact of its presence. Only the audio recordings were transcribed and access to these transcripts was restricted to the teacher concerned, the transcriber and the two research team leaders. Between the two cycles, the research team met to debrief the process and also to amalgamate the teacher researchers’ question category labels into some common category headings. The headings were to be further refined after Cycle 2. |

Each research team leader held one-to-one interviews with four teacher researchers at the conclusion of their data gathering and analysis. The interviews were audiotaped for later summary by the research team leaders. These summaries were emailed to the originating teacher researcher for their verification. In Cycle 2, each research team leader interviewed the four teacher researchers they had not interviewed in Cycle 1.

At the research team meeting at the end of Cycle 1, the teacher researchers were asked to record any questions and issues arising from the analysis of their first transcript. Their responses were to be used to inform the future direction of the project. The research team met again before the second cycle began. At this session, the teacher researchers completed a questionnaire that was intended to make explicit their beliefs about teaching and learning in mathematics (see Appendix C). In relation to this questionnaire, they listed four important features of a mathematics lesson along with why they believed these were important. At the same meeting, the teacher researchers responded to a series of questions aimed at revealing their experience as a teacher researcher up to that point in the project (see Appendix D). The next team meeting was after Cycle 2, and the teacher researchers were asked to identify three things they had learnt about questioning, and to highlight evidence of these in their lesson transcripts, where they could. As a follow-up to this session, the teacher researchers were emailed a final questionnaire (see Appendix E). The research team leaders asked them to write reflective responses that could then be included in the final report. Several team meetings were audiotaped to capture quotations for the final report. Throughout the project, the research team leaders kept a reflection journal. |

||

Analysing the data

| Teacher researchers | Research team leaders | ||

| When the teacher researcher had chosen a lesson for analysis, they recorded their initial impressions about their questioning within the lesson, which they later compared to their analysis.

On receipt of their transcript, each teacher researcher was released for two days to analyse their lesson, using their reading of the transcript alongside their recent recollections of the lesson that were assisted by viewing the videotape footage. They reviewed the lesson, making notes as they read through their transcript. They identified key episodes within the lesson, and examined these in some detail. Key episodes were chosen by the teacher researchers, who were asked to describe why they considered these to be key. The main analytical activity involved the identification and categorisation of questions within the lesson. This was achieved by physically extracting their identified questions from a hard copy of their transcript, then sorting them into groups of similar questions for which they then devised labels (Miller et al., 1986). The teacher researchers were furnished with instructions for the sorting process (see Appendix A). The second cycle’s analysis involved similar activities, except that questions were categorised under commonly agreed headings, and teacher researchers also completed a frequency table based on the categories. During the afternoon of the second analysis day each teacher researcher was interviewed by a research team leader, usually at the teacher researcher’s workplace. This interview supported the teacher researcher to reflect on aspects of their findings, and facilitated the communication of the teacher researcher’s thinking. Summaries of the interviews were later sent to the teacher researchers for verification, and findings were shared in subsequent group meetings. Group discussions formed a key aspect of the analysis and interpretation of findings. Each member of the team shared their findings, and similarities and differences were explored and debated. The Cycle 1 group discussion began the process of establishing common categories with which to analyse the lesson in Cycle 2. A further session was held for three teacher researchers to enable further input into this process. |

Overall, the data were analysed using the three main stages of data reduction, data display, and drawing and verifying conclusions (Miles & Huberman, 1994). Most of the data collected were qualitative. The research team leaders used the same sorting process that the teacher researchers had used to identify themes emerging from the two sets of interview summaries; this helped to reduce the collected data to its essence. The reduced data were then displayed to help identify trends.

Responses to the various questionnaires were compiled to support the identification of similarities and differences in the responses. Numeric data from the completed frequency tables (showing the number of each category of question included in the teacher researchers’ second lessons) were collated and graphed. The quantitative data were considered alongside the qualitative information in order to identify similarities and differences. The research team leaders discussed and debated apparent themes. |

||

Interpreting findings

| Teacher researchers | Research team leaders | ||

| The teacher researchers contributed to the process of interpreting findings at all stages of the project by responding to summaries of emerging ideas presented by the research team leaders.

Group meetings were a key aspect in distilling meaning from findings as they emerged throughout the project. The teacher researchers interpreted their findings in light of current research, which they discussed in a group meeting. The research consultant also made a presentation to the first meeting in Term 4, and this allowed the teacher researchers to interpret their findings in a broader context. In relation to the frequency table data, the teacher researchers made a number of suggestions for variations in the number of questions asked. |

The research team leaders verified their interpretations of the data with the teacher researchers by feeding speculations back to them at research team meetings for discussion and comment.

The research team leaders met following the interviews with the teacher researchers to share and compare findings, and then sorted responses from the interviews, enabling themes to emerge. With a collection of data available from each of the eight teacher researchers, apparent findings were readily triangulated by checking all the data from a single teacher researcher, and by checking across the group. Discussion and debate between the two research team leaders also contributed to the rigour of the processes and the findings. Findings were also discussed at meetings with the research consultant. |

||

The report writing process

| Teacher researchers | Research team leaders | ||

| The eight teacher researchers were unable to be fully involved in writing the final report. Instead, they wrote reflective responses to the final questionnaire, and these responses were used to amplify the teacher researcher’s “voice” in later sections of this report.

As well as this, teacher researchers have contributed quotations which have been drawn from a range of sources, including:

At the final team meeting, the teacher researchers were presented with an initial draft of the section on findings from this report for their comment. The teacher researchers received a final draft of the report before publication. |

Part-way through the project, the literature review from the proposal was revised for the teacher researchers, to provide them with a background of the research literature.

Following the completion of data gathering and analysis, the research team leaders worked intensively for two weeks, spending considerable time discussing, analysing, and reflecting on the collected body of data. It was decided that the style of presentation in the final report would reflect the partnership between the research team leaders and the teacher researchers. The research consultant was asked to give critical feedback on drafts of this report. |

||

Limitations of the research process

Some issues related to the data-gathering tools emerged early in Cycle 1. Using the audio and video technology presented a few minor problems; for example, the notetaker had a facility to record at various speeds which proved unhelpful.

Another issue was the timely delivery of transcripts to the teacher researchers. The timetable was very tight, leaving no margin for the late arrival of transcripts. Some of the teacher researchers commented on the inaccuracy or absence of the students’ comments in the transcripts; it had been difficult for the transcriber to decipher parts of some of the audiotapes.

A couple of research team meeting dates had to be changed; in one instance, this was to accommodate a particularly busy time for some of the teacher researchers who were involved in major school events. In a few cases, a teacher researcher was unable to attend a team meeting.

The timing for writing this report coincided with the competing demands of the end of the university and school years, including writing students’ end-of-year reports, devising class lists for the following year, and planning for camps. The extended deadline for completion of this report made the task manageable.

Ethical considerations

Informed consent was sought from each of the teacher researchers before their participation in the project. The teacher researchers were provided with a consent letter for parents of students in their class that explained that the students were not the “target” of the research. Principals, as the board of trustees’ representative for each school, signed statements giving their support to the project. The transcriber completed a confidentiality agreement.

During the report writing process it became evident that if the partnership was authentic, and the teacher researchers’ “voice” was to be as strong as it was intended, then the teacher researchers should be acknowledged as co-authors, although the use of pseudonyms throughout the report would be maintained. This entailed an addendum to the original consent form being signed. The principals of participating schools were also asked to give their consent, because by identifying the teacher researchers their schools could readily be identified.

4. Findings: Teachers developing as researchers

Ownership of the research and roles of the research team

An important principle of teacher research is that teachers have a “sense of ownership and control of their research” (Mitchell, 2002, p. 250). Current definitions of teacher research describe the selection and development of research questions as emerging from the teachers’ own practices (Cochran-Smith & Lytle, 1993). Although each of the teacher researchers joined the team with an awareness of the field they were to research, the requirements for the funding for this research had meant that the research questions and aims were established before they met together as a team. The research questions emerged from the research team leaders’ close links to teaching practice, both in their current and recent classroom teaching experience, and in the considerable number of mathematics lessons they had observed as numeracy advisers.

The project methodology was intended to ensure the teacher researchers assumed a sense of ownership of the project through major responsibility for the classroom-based data-gathering and analysis. As the project progressed it became apparent that much of the responsibility for its direction and the interpretation of findings also needed to be shared with the teacher researchers. Assumptions made by the research team leaders about the shape and course of the project were challenged as the teacher researchers took on greater ownership.

The research team leaders’ sense of ownership was strong at the onset of the proposal process as initiators of the research questions and the methodology. This sense of ownership diminished as the proposal progressed and as the three institutions involved established areas of territory and accountability. Ownership was further dispersed as the research team leaders continued to work with the teacher researchers. It became apparent that the research team leaders had begun the project expecting significant but limited input from the teacher researchers rather than an authentic partnership. Thus, to ensure the development of research capabilities of the teacher researchers, and to increase the validity of the findings, it was felt necessary to share the “power”. This was not easily achieved, as teacher researchers demonstrated differences in perceptions of their role and the research team leaders’ role. When asked to describe these roles within the research project, (see Appendix E, final questionnaire, Question 6) a number of common verbs were used in descriptions for both roles: provide, analyse, advise, develop, conclude, reflect and share. However, verbs used exclusively for research team leaders seemed to reflect the perception of research team leaders as project drivers, initiators and interpreters of findings: lead, organise, drive, generate, co-ordinate, facilitate, assist, support, encourage, interview, synthesise, question, and open. These verbs contrasted with ideas of the teacher researchers as workers and learners: gather, collect, complete, contribute, work, categorise, establish, challenge, debate, help, process, understand, learn, bring, impart, and review. It would seem that the co-researcher relationship “was infiltrated by the discursive positionings more in common in relationships between academics and teachers, or teachers and students” (Honan, 2007, p. 622).

Perceptions of roles were further complicated by the relationships previously established by the research team leaders as mentors and advisers within the context of in-depth professional development. Having previously assisted the teachers to analyse aspects of their mathematics teaching practice, the research team leaders were, to some extent, regarded as “experts” in the field under research. The diversity of perception of roles is apparent in the following quotations and excerpts.

| Teacher researchers | Research team leaders | ||

| Researchers appeared to give direction to the project and confidence that outcomes would be achieved. Researchers have provided the enthusiasm and momentum. Good support in terms of providing readings.

Natalie, final questionnaire I felt that at times there was a slight lack of direction during the meetings. Truman, final questionnaire We did have some partnerships although I think a partnership is a sharing of ideas and a forming of ideas together. In this form the researchers were facilitators but didn’t necessarily work on completing the same tasks. Ingrid, final questionnaire Leaders provided a great idea and framework. They were always confident about our role in the team, and were enthusiastic and supportive. Ursula, final questionnaire |

Part of this tension may have arisen because both of the research team leaders have acted as mentors in the context of mathematics education. Similar relationships exist with other members of the research team. This highlights the importance of clearly communicating to the teacher researchers our different role as co-researchers in this project.

Milestone Report 1

… clarified that my role is as a fellow researcher, not adviser. Research team leader comment from teacher researcher interview 1 summary |

||

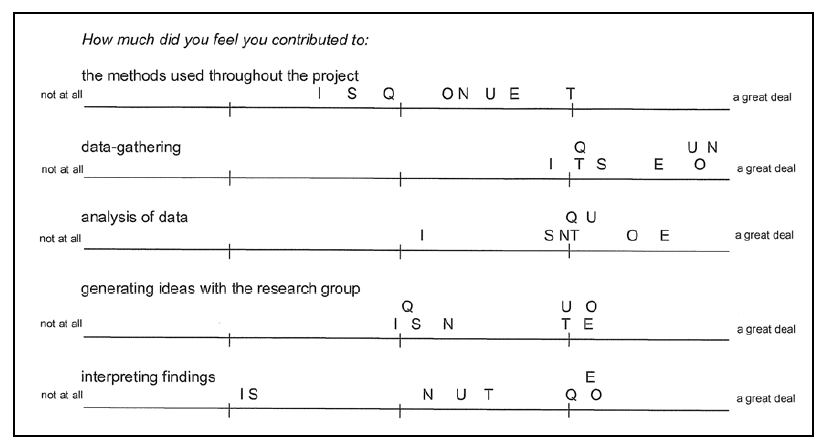

Figure 1 shows a range of perceptions expressed by the teacher researchers about their contributions to various aspects of the project.

Figure 1 Teacher researchers’ responses to Question 7 from final questionnaire (see Appendix E)

(letters in the figure refer to the initials of the teacher researcher pseudonyms)

In Cycle 1 of the data gathering and analysis, some of the teacher researchers described difficulty with the initial sorting of questions into categories. At this early stage, the teacher researchers tended to draw on frameworks and language about questioning that were previously known to them. In some cases they struggled to produce efficient descriptors from their own language to label groups of questions.

Had difficulty finding words to describe categories.

Ingrid, interview 1 summary

First time putting the questions into categories felt like you were on your own and

didn’t have a clear picture of what to do.

Stephanie, final questionnaire

One of the teacher researchers resorted to searching for question categories on the internet and many of the categories developed at this stage reflected the language in established taxonomies.

Perhaps this indicated the teacher researchers’ doubt that what they had to say would have validity or authority in the research project. The teacher researchers may have seen the research in traditional terms such as those described by Cochran-Smith and Lytle (1993) as “outside-in”, or as research which “constructs and pre-determines teachers’ roles in the research process” (p. 7).

| Teacher researchers | Research team leaders | ||

| Sometimes I think we are our hardest critics and this has helped to confirm or not confirm certain ideas I have had.

Quentin, final questionnaire We sound more knowledgeable than we thought we were! Ursula, final evaluation meeting |

Much of the research undertaken to investigate teachers’ questioning has been synthesised from data gathered by researchers observing in classrooms. There is little known about ways in which teachers view the role and formulation of questions within a mathematics lesson.… The extant knowledge base reflects a “looking from the outside in.” Our search of the literature located quite a few studies reporting teachers’ questions and questioning, but no investigations were identified that looked from the “inside out.”

TLRI Proposal for funding |

||

The process of sorting their questions had meant that the teacher researchers were encouraged to take responsibility for generating language and ideas, and the commonly agreed categories developed in the forum reflected their own language.

During the second cycle of data gathering and analysis, their sorting experience was more positive:

Felt better this time—having some categories to put the questions into, having some understanding of what she was doing, not feeling lost time.

Ingrid, interview 2 summary

The question categories worked—I could place all questions.… Analysis was easier with predetermined headings.

Quentin, interview 1 summary

Changes to the methodology

Aspects of the methodology were continually adjusted to allow the teacher researchers to develop a greater sense of control within the project.

| Teacher researchers | Research team leaders | ||

| The approach was good because it was flexible and allowed the group to have true ownership. The “organic” nature of the form of our meetings allowed researchers to listen without taking over with pre-determined paths.

Erin, final questionnaire |

The task of sorting their individual question categories didn’t go as intended. We had planned for the teacher researchers to work in 2 groups.… However … [one of the teacher researcher’s] suggested they undertake the task as one group. We OKed this as we wanted to be responsive to the group—give them a sense of control over the process.…

Research team leaders’ reflection journal |

||

In some respects this flexibility paralleled the way the teacher researchers responded to their students, (see Findings: Questions—planning and adapting questions) changing direction and transferring power within their classroom practice:

One thing I’ve really enjoyed about the research, is that it’s just confirmed for me a lot of good teaching practice.… It’s made me be a little bit more relaxed about letting the children take control.… I like to have clear learning intentions and know where I’m going and how I will know that the children have got there, but maybe I’m thinking I need to be a little bit more relaxed about that, so they can take the lesson where they want it to go a little more.… And I think to have less control you have to be more secure in yourself and you also have to be more secure in yourself to guide—not in a pushy way—but to guide as a good teacher.

Erin, interview 2 summary

It was originally intended that the research team leaders would conduct an analysis of each lesson at the same time as the teacher researchers, reading the transcript and viewing a video of the lesson. Their analysis would then be “compared” with the teacher researcher’s findings. However after the initial trial phase, it was decided that the teacher researchers would be solely in charge of the analysis process. This meant that the teacher researchers’ own observations and views on their lessons were paramount. The trial teacher referred to the interview process following the analysis as a “grilling”, so the subsequent interviews were conducted by only one research team leader, and preparation consisted of familiarisation with the lesson transcript. The interview then served as an aid to reflection, rather than as a comparison of findings.

| Teacher researchers | Research team leaders | ||

| Interviews were a supportive and positive process.

Stephanie, final questionnaire

|

Another factor that may have contributed to the tension in the interview was the presence of both research team leaders and the fact that we did not provide the teacher researcher with the interview questions before we met. At a later meeting with [the research consultant], it was agreed that it would be better for the teacher researchers to work as a team, along with the research team leaders, to develop questions to be discussed at the interview. This is more in line with our aim of developing the teacher researchers’ research capabilities and sits more comfortably within our project. It was also decided that only one team leader would be present at each interview.

Milestone report 1 |

||

Along with the generation of interview questions, other measures were taken to encourage ownership of the project during group forum sessions, such as writing a definition of a question, establishing category labels and defining “effective questioning”. Following each of the interviews, interview summaries were sent to each of the teacher researchers for verification.

An important aspect of developing the teachers’ capability as researchers was introduced between the two cycles of data gathering. At the suggestion of the research consultant, relevant research readings were sent to the teacher researchers for discussion at the forthcoming meeting. The themes for these readings were established in response to ideas emerging throughout the interviews and in the second research team meeting, and were also directly indicated by the teacher researchers in their responses to questions and issues arising from the analysis of transcript 1 (Appendix B). An additional day was allocated to discuss these and other relevant themes, to enable the teacher researchers to see their current research in the context of other research in this area. This also allowed them access to language and ideas when examining and discussing their questioning in Cycle 2; for example, the use of the phrases “reflective toss” (van Zee & Minstrell, 1997), “funnelling and focusing” (Wood, 1998), “classroom norms”, and “sociomathematical norms” (McClain & Cobb, 2001) in subsequent interviews and group forums.

Discussions with two research consultants prompted moves to incorporate the teacher researchers’ “voice” more prominently in the writing aspects of the research. The teacher researchers’ workloads did not allow for a period of sustained, focused writing; it was decided that a questionnaire would allow them maximum opportunity to review the research outcomes and processes, and contribute reflective and crafted responses which could be incorporated into the report. The style of the written report would also reflect the partnerships developed in the project, making visible the key role the teacher researchers had throughout by anchoring interpretations of findings in their statements. Aligning the research team leaders’ contributions, observations, and interpretations alongside those of the teacher researchers’ further reflected this partnership. A well-developed draft of the findings in Sections 4 and 5 were shared with the teacher researchers for their editorial comment at the final evaluation meeting.

Developing community and accessing support

The research team meetings were important in refining the methodology and allowing the research team to discuss and interpret findings. They contributed toward establishing a shared understanding of the research question and a common language to discuss findings, generated common categories for coding questions, and assisted the teacher researchers to establish a common interpretation of findings. These forums also provided the collaborative support necessary for such projects highlighted in Mitchell (2002).

Being away from the school environment and discussing ideas with other teachers was a definite plus. Obtaining other people’s perspective on issues surrounding them. Developing relationships with similar people in similar roles [worked well].

Quentin, final questionnaire

Mitchell notes the loneliness of the process often present in such studies which was also identified within our project, as the following quotations show.

| Teacher researchers | Research team leaders | ||

| First time putting the questions into categories [you] felt like you were on your own and didn’t have a clear picture of what to do.

Stephanie, final questionnaire For the first release days I felt isolated and completely lost. Ingrid, final questionnaire I was wondering if by doing some of the work in teams might have helped relationships between the teachers to develop. I found it was just my ideas and me. Olivia, final questionnaire |

How are we mentoring our teacher researchers as researchers? … Perhaps we need to formally set up a buddy system, and give the teacher researchers purposes for communicating with each other to break down isolation?

Research team leaders’ reflection journal

|

||

At times, interactions at the research team meetings caused concern. The fact that three of the teachers were drawn from one school, and knew each other well, may have affected the group dynamics:

| Teacher researchers | Research team leaders | ||

| The main issue when working together would be the dynamic or mix of the group where people had strong views and opinions, and decisions were sometimes dominated and preconceived.

Quentin, final questionnaire I also felt disadvantaged by not having someone to talk to and felt that three teachers from the same school had an advantage over everyone else. Ingrid, final questionnaire Group putting all questions into categories— some too dominant and some not assertive enough! (Hadn’t established a sense of the group working together.) More work [was needed] to establish an environment for all the group to feel comfortable where all ideas would be valued. (This did become better during the project.) Stephanie, final questionnaire I know we did share in the wider group, but not everyone felt comfortable doing that. Olivia, final questionnaire

|

More significant was an issue that emerged at our second meeting of the research team. In order to develop common question categories, the teacher researchers were asked to each take their own sorted questions, with category labels they had devised, and see how they could group them together where categories were alike. There was a lot of very rich, and at times animated, discussion during this sorting task. However, some of the teacher researchers found a number of difficulties with aspects of this task and remained on the fringe of the activity. The research team leaders have done several things to determine why they did not fully engage with this work. We have:

adapted from Milestone Report 2 To enable them to contribute more significantly to the process, these teacher researchers were released to attend an extra half-day meeting with the research team leaders. This enabled them to include their ideas with those of the group, and to refine the question categories which were then disseminated to the rest of the team. adapted from Milestone Report 3 |

||

As Cochran-Smith and Lytle note: “Participation in teacher research requires considerable effort by innovative and dedicated teachers to stay in their classrooms and at the same time carve out opportunities to enquire and reflect on their own practice” (1993, p. 20). An awareness of the issue for the teacher researchers of managing their research project commitments along with teaching workloads was evident throughout:

| Teacher researchers | Research team leaders | ||

| The amount of time involved was underestimated and at times it got stressful with other demands of work.

Stephanie, final questionnaire Was concerned about amount of time out of class and scheduling relievers, etc., as well as added workload for us!! Ursula, “Working as a teacher researcher” questionnaire Concerned over scheduling release time and added workload. Natalie, “Working as a teacher researcher” questionnaire |

Thanks everyone for this round of data-gathering—we realise it’s been difficult to complete this with everything going on in your schools at the moment!

As we have received some objections to the proposed date for our next meeting in the holidays, but none for the new proposed date of 24 October … our next meeting is now set for … Email to team, September

|

||

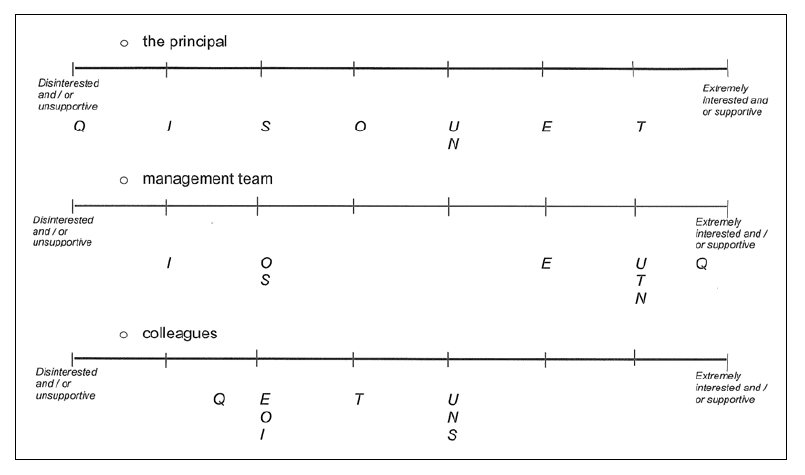

Oliver (2005) found that school support was a significant factor in the success of teacher research projects. Responses to a questionnaire given to the teacher researchers midway through the research (Appendix D) described a full range of support from the teachers’ schools, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2 Teacher researchers’ responses from “Working as a teacher researcher” questionnaire

Following the questionnaire, the research team leaders sent out a letter to participating principals to update them on the progress of the research.

| Teacher researchers | Research team leaders | ||

| This was viewed as something extra I was doing and not really seen as part of my work so didn’t really get support from school.

Stephanie, final questionnaire

|

We thought it was time we updated you on your teacher’s participation in our Teaching and Learning Research Initiative project. We are aware that teachers need support within your school, and that you need to be well informed in order to provide this!

… We are very appreciative of the hard work your teacher is doing as a valuable member of our research team. Examining one’s teaching practice as closely as the Teacher researchers are doing is a potentially isolating experience; the support and interest you show in the challenging work in which your teacher is engaged plays an important role. We would also like to thank you for allowing your teacher to be released from their normal duties, to spend time reflecting on and analysing their practice. This time factor has been essential for the success of the project. Thanks again for the support you are showing your Teacher researcher and the work they are engaging in as key members of our research team. Letter to principals, prior to Cycle 2 |

||

External systemic support (Osler & Flack, 2002) was also essential to the project. Money allocated from funding provided through the Teaching and Learning Research Initiative allowed the teachers to have release time to analyse their lessons in detail, and to attend meetings.

… having the days provided to analyse the transcript helped with workload.

Natalie, final questionnaire

Process of video/taping and sending off to get transcribed was great. It was fantastic to receive the time to do this properly.

Ursula, final questionnaire

Links to practice

The research process was seen as being of significant relevance and having an immediate effect on the teacher researchers’ own classroom practice.

| Teacher researchers | Research team leaders | ||

| This project is about your daily maths teaching, it is highly relevant to classroom teaching.

Natalie, final questionnaire I have developed an awareness of the types of questions that I can use to get responses from the children. Teacher-directed to more childcentred.… I always knew that learning and teaching run together but the research has helped to identify a specific area of focus and thought and therefore it must have an impact back in the classroom. Quentin, final questionnaire I have learnt a lot more about me than I ever thought I was going to. This has identified needs and gaps in my questioning and there have been surprises in other areas. I have enjoyed the experience and would do it again. Olivia, final questionnaire Has made me reflect more deeply on my daily practice and the types of questions I ask. It has made me consider more carefully the purpose of questions. Videoing lessons also gave me lots of feedback about all aspects of my teaching. Ursula, final questionnaire Through video, transcribing etc. have just thought more about the purpose of questions. Why am I actually asking this question? Moreover, after doing this, I can sense when the questioning direction is not as effective as it could be and know (mostly) where I need to lead it! Truman, “What have you learnt about |

The outcomes [from the research] will increase potential for improving student achievement based on teachers’ insights into their own teaching practices.

TLRI Proposal

|

||

The teacher researchers also described possible directions for further research about their own practice:

Maybe the biggest question for me personally is how to take the information I have now about my questioning and find practical ways to implement change in the class. Maybe I need to do more reading about that.

Olivia, final questionnaire

It would be interesting to look again at the types of questions asked at which part of the lesson. I found the frequency table interesting and it would have been good to have another one to compare. I would also like to compare the frequency of questions between different levels. Are there any significant shifts in the types of questions asked?

Stephanie, final questionnaire

Early on in the project the teacher researchers recognised that this research should be able to inform the wider teaching community, and five of them described possibilities for dissemination (“Working as a teacher researcher” questionnaire).

Research within the real context of the classroom has a higher degree of validity and acceptability to other teachers.

Erin, final questionnaire

When the teacher researchers were asked to consider possible wider applications of what they had learnt from their research, it was the research process rather than their findings about their use of questioning that they considered important in developing teaching practice:

Having the opportunity to micro-analyse within a subject area has heightened my awareness of the strengths and weaknesses of my own classroom practice. This in turn has challenged me to either strengthen those practices that are valuable and to adjust/ improve those practices that are weak.

Erin, final questionnaire

The research has allowed me to look at myself as a practitioner. I did not really have an opinion about questioning before I started this research but through this process I have been able to focus more on developing questions that require more input from the student.

Quentin, final questionnaire

The teacher researchers found it difficult to be specific about exactly how the research findings relating to questioning might be useful to teachers in general. The suggestion was made that the categories may be useful for planning, and one teacher described how she had placed a list of the categories on her classroom wall so that she could refer to them during a lesson. The categories were seen as useful to the teachers involved in the project, as they had created them and “owned” them. There was a lack of confidence that other teachers would find them useful.

We need to be careful with transferring research to their [other teachers’] situations— qualify it with the fact that it is for “here and now” and may be less relevant when different factors are taken into account.

Ursula, final questionnaire

This was an interesting exercise and I wonder how it can be brought back into a school setting for whole staff development. It could be a nightmare to organise and facilitate, let alone fund!

Stephanie, final questionnaire

This research was done by a small group of teachers. What are the implications for other teachers? How would it transfer across to other teachers? How does questioning measure up against other factors to produce effective outcomes for children?

Natalie, final questionnaire

Perhaps this reflects findings from Mitchell (2002), who noted: “teacher researchers are more interested, at least initially, in finding what may appear to be context-specific solutions in their own classrooms” and that many aspects of the research process are personal: “[I]n some important ways, the journey is experiential—some parts of the story cannot be told, they must also be experienced” (pp. 262–263).

Changing views of research

Osler and Flack (2002) found that skills to be developed by teacher researchers included: “reflection, articulation, familiarity with research literature, linking their own work to the work of others, writing and presentations” (p. 243). The development of each of these skills was in evidence in various forms throughout the project. The developing capability of the teachers as researchers was reflected in their changing views about the nature of research. They showed an ability to reflect on and articulate their practice:

Classroom research helps you to reflect on what you do and can only benefit student and teacher learning.

Ingrid, final questionnaire

It is a huge learning curve because you see things from a different perspective. You’re not critical but more reflective of how things are.

Quentin, final questionnaire

Research was seen as a vehicle for sharing, challenging or confirming existing ideas and introducing new ones. One aspect described by the teacher researchers was the complexity and scale of the research process:

Research is fascinating when you are involved in it!! It is really difficult to do. [There are] heaps of factors to consider. It doesn’t always give us answers.

Ursula, final questionnaire

It has been fun, scary, challenging and time consuming.… I realise how much work goes into these projects.

Olivia, final questionnaire

That it involves many facets and ideas … the sharing of thoughts with other researchers and the intricacies involved.

Quentin, final questionnaire

Some major shifts in understanding about research were evident.

| Teacher researchers | Research team leaders | ||

| When we first started out I was not sure of what I was getting into and therefore my mind was a bit of a blank slate. I think there is a definite need for teacher research to continue as it informs practice and changes views and brings together your own personal experiences which must be better for your classroom.

Quentin, final questionnaire Research doesn’t always provide you with answers. It often provides more questions. There isn’t always a neat, tidy conclusion that can be drawn. Natalie, final questionnaire |

This [the project] will develop skills and understandings about the nature of research.…

TLRI Proposal |

||

An opportunity for a teacher researcher and a research team leader to present aspects of the research process at a national conference further contributed to the development of research skills. This enabled the research partnership fostered during the project to be made visible. It also allowed the teacher researcher to be included in the national research community and aspects of the research to be critiqued.

Further research questions

Throughout the research, areas for future investigation continually arose.

| Teacher researchers | Research team leaders | ||

| Discussed whether we might be limiting students’ responses by the questions we ask them.

Ursula, interview 1 summary Natalie wondered why she had asked so many more closed than open questions. Natalie, interview 1 summary Maybe when you put the open question is key? Natalie, interview 2 summary “Is that the easiest way to do that?” Ursula is reflecting on the wording of this question—is there a better way to ask students to evaluate strategies? Ursula, interview 1 summary |

What is the role of telling students, in relation to using questioning?

Research team leaders’ reflection journal What does make a teacher change their practice? Research team leaders’ reflection journal Do patterns of questioning change over the school year, e.g., would a teacher be more focused on fostering student interaction as they establish the class culture at the start of the year? Research team leaders’ reflection journal |

||

At the completion of the research, a range of diverse questions for further research had emerged from the group:

| Teacher researchers | Research team leaders | ||

| Do teachers need more time to plan and think about questions to ask in lessons?

Ingrid, final questionnaire Have we swung the pendulum too far … Can there be too much talk in the classroom? Erin, final questionnaire Outcomes are extremely difficult to measure. How can we make judgements about effectiveness of questioning, when we are only looking at questions, not really comparing effectiveness of individual lessons? Ursula, final questionnaire |

There seems to be a trend towards asking more higher order questions of more able students. Is this pedagogically justifiable?

Research team leaders’ reflection journal If decisions about questions are made “in action”, how do teachers know where to go next? Research team leaders’ reflection journal |

||

5. Findings: Teachers’ use of questions in mathematics

Identifying the various kinds of questions teachers use in mathematics

Definition of a question

The research team devised a working definition of what constitutes a question. For this project, a question was “any form of language that is aimed at eliciting a response”. This is a broader definition than that found in the Concise Oxford Dictionary (Allen, 1990). This extended what might be identified as a question beyond a sentence that ended with a question mark in the lesson transcripts, so that utterances such as, “Listen carefully to what Lily is saying and let’s see if we can understand how the mirror, how their hands coming together helped” (Erin, lesson transcript 2), were counted as a question. Although the definition included “any form of language”, the methodology of the project allowed for a focus only on oral questions.

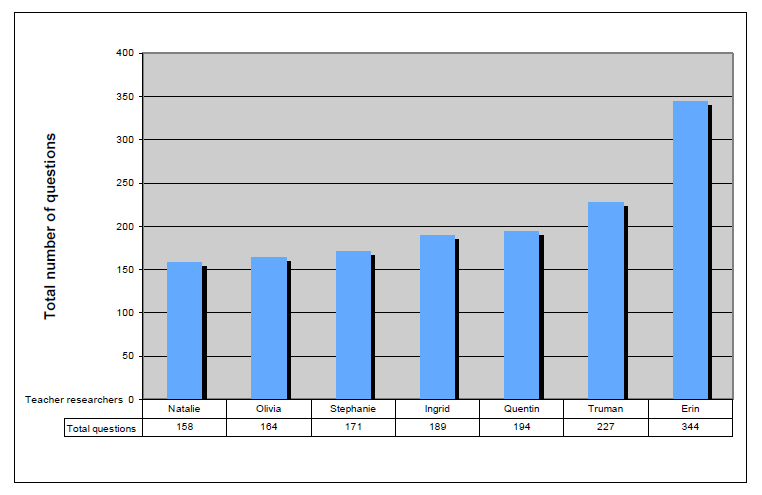

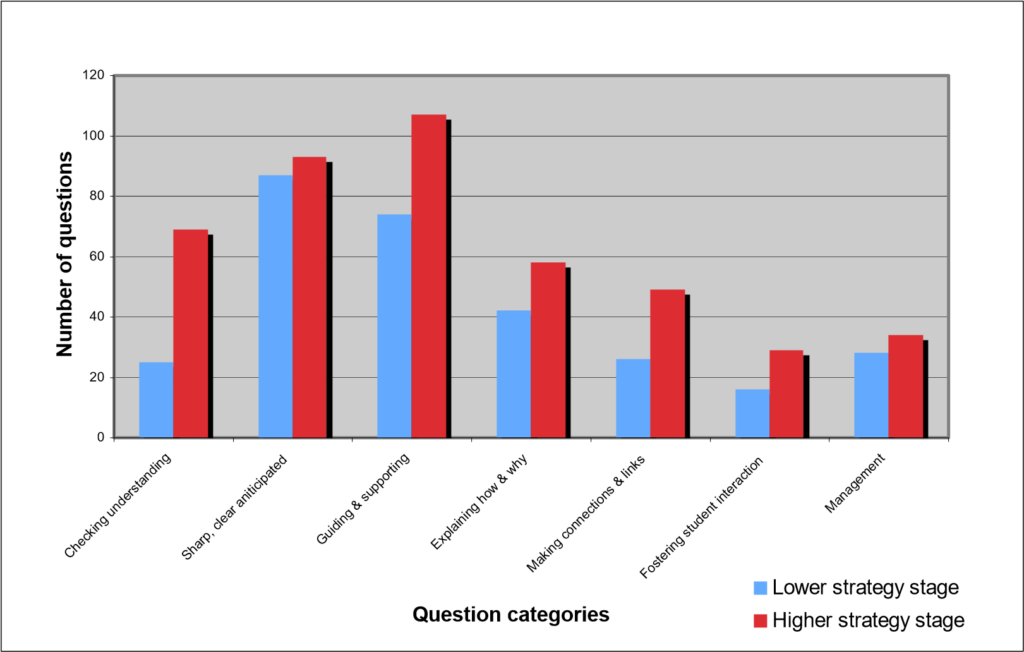

Development of question categories

In the first cycle of data gathering and analysis, the teacher researchers worked independently to devise their own question categories to include every question they asked during one numeracy lesson. The teacher researchers created between six and 17 categories for the questions, with three people each devising eight categories. The research team met at the end of this cycle, with the main purpose of developing shared question categories from the teacher researchers’ individual ones. This proved to be a complex task that could not be completed with sufficient discussion and debate within the time available. The seven teacher researchers who were at the meeting had varying degrees of input into this process.