1. Research questions and aims

Background to the project

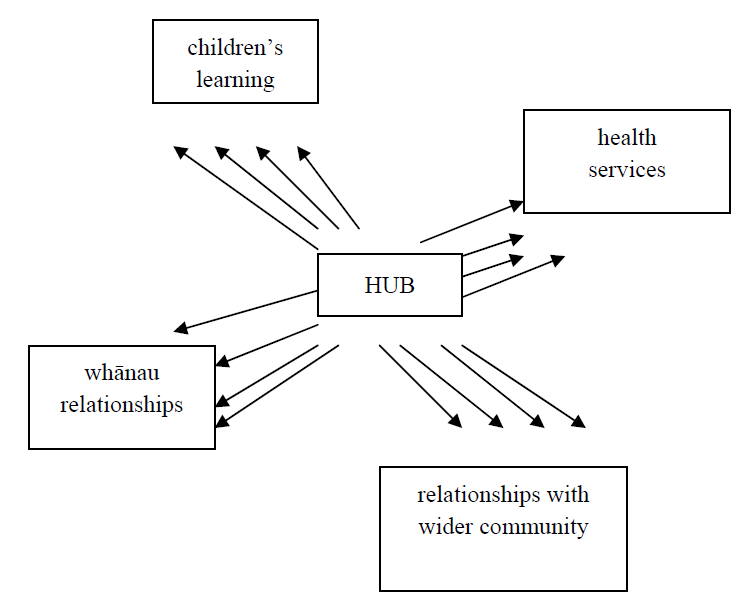

This project came about after discussions with the general manager of the Wellington Region Free Kindergarten Association and Jeanette Clarkin-Phillips (University of Waikato) about setting up a research partnership to support the teachers at Taitoko Kindergarten in Levin. The teachers were establishing an integrated community centre (the whānau tangata centre) as part of a parent support and development initiative funded by the Ministry of Education in conjunction with the Ministry of Social Development. This initiative in Levin includes a drop-in centre for parents, parent workshops on topics of the parents’ choice, a well-resourced whānau room, facilities for infants and toddlers, school liaison visits and liaison with local health centres. The initiative at Taitoko Kindergarten is one of six pilot parent support and development projects. These pilot projects do not include any research components to evaluate the processes and outcomes for teaching and learning, or the level of engagement of the community. This Teaching and Learning Research Initiative (TLRI) project, in one centre, researched these aspects of the initiative in an ongoing action research project.

The parent support and development contracts are a relatively new initiative for New Zealand, and this research project was designed to provide information to guide this teaching and learning policy for future initiatives of this nature. The aim of the TLRI research project was to investigate the development of the whānau tangata centre at Taitoko Kindergarten with teaching and learning in mind.

Integrated services

Integrated or “joined-up” services are not common in New Zealand. In the United Kingdom and the United States, however, this concept has been developing for some time, and current government policy in England is for a children’s centre in every community by 2010 to provide services that are multidisciplinary and interagency (McKinnon, 2006). Research from a New Zealand perspective about integrated services is therefore sparse. There is local research that provides evidence for the importance of involving parents in their children’s learning: a Manukau family literacy project (Benseman & Sutton, 2005) and research on the experience of Years 9 and 10 Māori students in mainstream schools by Russell Bishop and colleagues (2003) indicate that developing strong responsive and reciprocal relationships between teachers, children and whānau in communities of diversity improves children’s learning. In particular, The Parent and Child Together Time of the Manukau family literacy project has shown parents becoming more comfortable in sharing in their child’s learning through the opportunity to work alongside their child. The New Zealand Council for Educational Research’s (NZCER’s) Competent Learners @ 14 longitudinal study indicates that those children who had strong family support were more likely to continue to engage with learning throughout their education (Wylie, Hodgen, Ferral, Dingle, Thompson, & Hipkins, 2006).

An evaluative study of preschool education in five countries for UNESCO concluded that establishing a dialogue that is meaningful to parents and a shared understanding of what children are learning ensures a worthwhile partnership (Sylva & Siraj-Blatchford, 1995).

A number of studies from the United Kingdom demonstrate clear evidence of the benefits of empowering parents to feel competent and confident in their parenting roles. Teachers from the Thomas Coram Early Excellence Centre describe the benefits for children’s learning in their centre through the close support and involvement of parents (Draper & Duffy, 2001). These teachers saw the centre as bringing together two halves of the child’s world which deepened their understanding of the child and their family. They argue that:

…the opportunity to be involved, especially in their own child’s learning and the management and development of the centre, must be open to all parents. (p. 158)

Sheffield Children’s Centre in the north of England reports great success in recognising diversity and involving parents in their children’s learning by acknowledging the wealth and richness of “difference” within the community (Dahlberg & Moss, 2005). Parents who would otherwise feel marginalised and unable to contribute to their child’s learning and development have been empowered to take on responsibilities and opportunities for enhancing their own wellbeing which has, in turn, had a positive effect on their children.

Projects such as the American Perry Preschool High-Scope project (Schweinhart, Barnes, & Weikart, 1993), the W. K. Kellogg Foundation (Washington, Johnson, & McCracken, 1995) and the Peers Early Education Partnership in Oxford (PEEP), (1999) all demonstrate the significant and lasting benefits from encouraging and building greater links between home and the educational setting.

The Pen Green Centre for Under Fives and Families, a well developed initiative in Corby, England, incorporates an early childhood centre at the hub with a wide variety of interagency and multidisciplinary services attached. This centre has continued, over the past 17 years, to work closely with parents and families providing support and opportunities that have benefited the whole community (Whalley, 2001).

The Funds of Knowledge project carried out by researchers from the University of California is based on the cultural-historical psychology of Vygotsky (González, Moll, & Amanti, 2005). Vygotsky emphasised the importance of the cultural practices and resources mediating the development of thinking and the Funds of Knowledge Project uses information gathered from families to enhance teaching and learning for students in the classroom. By interviewing families in their homes, teachers increase their understanding of the cultural practices and resources used by families in their everyday lives. As teachers discover the funds of knowledge that families have they endeavour to incorporate these into everyday classroom learning opportunities, thus making teaching and learning more responsive and meaningful for students. The involvement of parents and families in projects and teaching opportunities based on the funds of knowledge of a family or community have resulted in empowered and motivated students and families (González et al., 2005).

Principles that shaped the TLRI project

The early childhood curriculum, Te Whāriki (Ministry of Education, 1996), has as one of its principles family and community/whānau tangata, which states that:

…the learning and development of children is fostered if the well-being of their family and community is supported; if their family, culture, knowledge and community are respected; and there is strong consistency among all aspects of the child’s world. (p. 42)

Thus the above research project has the potential to have an effect on the understanding and implications for practice associated with this principle.

Mason Durie’s Māori health model, whare tapa wha, outlines four dimensions necessary in equilibrium to ensure good health: te taha wairua/spiritual aspects; te taha hinengaro/mental and emotional aspects; te taha whānau/family and community aspects; and te taha tinana/physical aspects (Durie, 1994). These dimensions not only mirror the four principles of Te Whāriki (empowerment/whakamana; holistic development/kotahitanga; family and community/whānau tangata; and relationships/ngā honongā) but can also be found in the research project as it attempts to strengthen relationships and build a community of learners.

The research takes an ecological perspective on teaching and learning (Barab & Roth, 2006; Bronfenbrenner, 1979). In terms of the children’s learning, the university researchers involved in this project have been interested in assisting with (and documenting) the development of connections between the curriculum at the kindergarten and the world beyond. Barab and Roth (2006) comment that:

…a core challenge of education is how to develop curricular contexts that extend themselves meaningfully into the personal life-worlds of individuals. (p. 7)

Research questions

The project had two research questions:

- What processes and practices have enabled the whānau tangata centre to strengthen relationships with the community and to provide new learning opportunities for the children, parents and whānau?

- What strategies can further strengthen the relationships with the community, and provide enhanced learning opportunities for the children and parents and whānau?

Taitoko Kindergarten had been actively involved in meeting the learning needs of children within the community for 25 years, and has increasingly identified the much broader and interwoven issues facing many Taitoko whānau. Although the teaching team was excited at being a part of the parent support and development initiative, they were also aware that they would face challenges that would have an effect on their practice. The parameters of the initiative did not include an exploration of these challenges. The teaching team’s commitment to ensuring effective teaching and learning at Taitoko Kindergarten has led them to seek evidence-based teaching practices, inside the vision of the parent support and development initiative. The TLRI research partnership has helped to provide this.

Through action research, the teaching team and researchers have addressed the teachers’ questions associated with this involvement and commitment: questions associated with (a) the strengthening of relationships (how this has been done so far, and how might it be furthered); (b) changes in practice (what is possible, what appears to be effective); (c) diversity (how a range of funds of knowledge can be shared and included in curriculum); and (d) documentation (how this can engage families and learners).

Strengthening relationships

An aim of the project was to ascertain whether the establishment of the whānau tangata centre was strengthening the relationship with the community and providing new learning opportunities for the children, parents and whānau.

Changes in practice

The research team’s discussions with the teaching team and Wellington Region Free Kindergarten Association identified the commitment of both to ensuring that the whānau tangata initiative had positive outcomes for children’s learning and that they were able to reflect on their practice and make changes to accommodate the strengths and interests of children and their parents and whānau throughout the establishment of the integrated centre. The teaching team at Taitoko had already identified areas where the establishment of an integrated community centre would affect their current practices and, in response, had made some changes to their practice. If the teachers were to continue to respond to new developments and strengthen the relationships with the community, they needed to be able to identify and reflect on the processes and practices already in place to identify what has been successful and effective. As Day and Harris (2002) suggest from their analysis of research about reflection, re-enacting or recapturing of events and accomplishments in which to analyse and learn from are hallmarks of effective reflection.

Diversity

The teachers were particularly interested in responding to the diversity of the community at the kindergarten. They wanted to know what further strategies they might use as teachers to strengthen their relationships with a community that included 59 percent Māori and 19 percent Pasifika parents and whānau. The teaching team was very mindful of the fact that, at the time the researchers began the TLRI project, they were three Pākehā women in a diverse community who had enjoyed 10 years of engagement in the community but wanted to strengthen their relationships within this community by engaging in teaching practices that accounted for and responded to diverse learners.

Documentation

The teaching team members were keen to have avenues available to them to look at their teaching, planning and documentation in an informed manner and to respond accordingly. In particular, they were interested in strengthening their documentation of the parent and whānau voice in children’s learning and assessing the difference that occurred through parent/whānau involvement in the whānau tangata centre. The Wellington Region Free Kindergarten Association was very insistent that the action research project would keep returning to the value for children’s learning of the kindergarten’s initiatives.

2. Overview and discussion about the research design

Action research

Using an action research design, the study collected both quantitative and qualitative data through a variety of methods. Zuber-Skerritt (1996 p. 85) describes action research as:

critical (and self-critical) collaborative inquiry by reflective practitioners, being accountable and making the results of their inquiry public, self-evaluating their practice, and engaged in participatory problem-solving and continuing professional development.

In this TLRI research project, critical, collaborative inquiry by reflective practitioners occurred by addressing the research questions through discussion, gathering of data and the analysis and exploration of that data with the researchers.

Accountability to the wider public occurred both through regular reporting to parents and whānau and the wider community agencies involved in the project and through teachers taking opportunities to share their research findings with other professionals. The research team engaged in evaluation as they analysed the data and gathered evidence from parents and whānau, making necessary modifications and changes to further strengthen relationships.

Method

Research site

The research site was Taitoko Kindergarten, a sessional kindergarten in Levin with a staff of 3.6 registered and qualified teachers. The roll of 40 children per morning session and 30 per afternoon session comprises approximately 59 percent Māori families and 19 percent Pasifika families, with the remainder being Pākehā and Asian.

Situated in Levin East, Taitoko is an isolated community in which, apart from the Taitoko School, there are no services or a community centre readily available. Parents must walk the approximately five kilometres to the Levin township to access services. This proves particularly difficult for the mothers of children attending Taitoko Kindergarten, many of whom have babies and toddlers and rely on public transport.

The demographics of the Taitoko community show, relative to other communities in New Zealand, a high percentage of younger children, a higher percentage of Māori and Pacific Nations people, lower income levels, a lower percentage of people aged over 15 years with a postschool qualification, a higher unemployment rate and more single-parent families.

Participants

The teaching team at Taitoko worked in partnership with researchers Margaret Carr and Jeanette Clarkin-Phillips from the University of Waikato. The senior teacher from the Wellington Region Free Kindergarten Association, who was responsible for the professional leadership of Taitoko Kindergarten, also supported the research with assistance and advice.

Consent was gained from the parents and whānau to allow the university researchers to access children’s portfolios and to participate in the research through interviews.

Data collection

Data for the research were obtained through a variety of methods, depending on the focus of the research question. Copies of learning stories (Carr, 2001) from children’s portfolios and whānau voice sheets, taperecorded conversations with the teachers and researchers, informal interviews with playgroup parents and semistructured interviews with the senior teacher and general manager of the Wellington Region Free Kindergarten Association all provided data for analysis.

Strategies employed to develop effective relationships and partnerships

The researchers met with the teaching team at least once a term and spent some time engaging with children and whānau during the kindergarten sessions. This allowed the researchers to develop relationships and become familiar faces within the kindergarten community. Regular email contact with the teachers also provided opportunities for maintaining and building relationships over the period of the project. The length of the project (two years) has also been a positive factor in developing effective relationships.

The decision of the researchers to always be mindful of the pressures on the teachers in their dayto-day interactions and teaching responsibilities has ensured that any decisions coming from the data gathering and discussions have not placed extra pressure or burden on the teachers. The majority of initiatives associated with changes in practice were in the context of what was already happening in the day-to-day teaching. Hargreaves (2004) suggests that for enhanced learning to occur for students and for teachers to make changes in practice, this needs to occur through aspects of teaching and learning that apply to every learning environment. Teachers want to know that the changes they make will not result in more work and that they will see tangible benefits from the changes.

Barriers encountered

One of the barriers encountered was time. This was a study of a parent support and development contract over time. Parent support and development projects develop slowly. Thus, the research carried out at the beginning of the parent support and development contract was constrained by the newness of the initiative and by the need to understand what could be achieved, particularly in a relatively transient community that had not always experienced positive professional relationships.

Ethical issues

The project had ethical approval from the School of Education Ethics Committee at the University of Waikato. No ethical issues arose during the research.

3. Findings in relation to the research questions

The research questions for this project were:

- What processes and practices have enabled the whānau tangata centre to strengthen relationships with the community and to provide new learning opportunities for the children, parents and whānau?

- What strategies can further strengthen the relationships with the community, and provide enhanced learning opportunities for the children and parents and whānau?

We will discuss these questions separately, although we explored them together. The findings related to the first question are discussed in Section Four in the context of providing “gateways” or “entry points” for parents and whānau to engage with and participate in their children’s learning. The second question clarified our understandings of the ways in which the whānau tangata centre had strengthened relationships with the community and provided learning opportunities for the children, parents and whānau. We discuss the findings in relation to the second research question in Section Five.

Background initiatives from the parent support and development project

The establishment of a whānau tangata centre at the kindergarten through the parent support and development project meant a number of new initiatives at the kindergarten. The head teacher, Caryll, was the co-ordinator of the parent support and development project, which began before the TLRI research project and was to continue for six months after the completion of the TLRI project. Caryll has had release time to present the project to community agencies, establish relationships and liaise with other professionals. The initiatives that were instigated during 2007 and 2008, and the last six months of 2006, included:

- the employment of two part-time kaimahi (one Māori and one Tongan)

- the establishment of a playgroup for parents and whānau and children under two

- the renovating of the kindergarten to include a whānau room

- a modernised and enlarged kitchen

- a verandah enclosed to provide space for a playgroup

- regular kapa haka sessions for children

- ongoing relationship with local kaumātua

- weaving and craft workshops

- cooking classes.

There were ongoing visits from the following organisations, projects or programmes:

- the public health nurse

- Healthy Heart Foundation

- breast screening professionals\

- immunisation nurse

- B4 School co-ordinator

- Car seat and safety programme

- Sports Manawatu

- Cessation of Smoking programme

- Women’s health programme

- Diabetes awareness programme

- asthma, ear and eye health organisations

- No Sweat Parenting programme

- Strengthening Families programme

4. Gateways

Gateways: Research question 1

The first research question asked: What processes and practices have enabled the whānau tangata centre to strengthen relationships with the community and to provide new learning opportunities for the children, parents and whānau?

The findings for this research question are located in the context of entry points or gateways to participation and engagement. Hargreaves (2004) talks about gateways for student personalised learning and that these gateways are part of the everyday context of learning and teaching. The university researchers have drawn parallels with parent learning and engagement and see a similar significance in these gateways. For parents to engage in their children’s learning, they need to have entry points that complement their everyday lives rather than provide barriers by being something outside of their context. Bringing their children to kindergarten provides a gateway for parents and whānau and teachers to build relationships for further engagement in children’s learning. Every early childhood centre and every community is different, and the pathways for developing relational agency (Edwards & D’arcy, 2004) will be very different as well. Relational agency refers to a capacity to engage with a group: interacting, sharing, listening, talking and working together. It includes more than social skills: it adds an (affective) inclination to be engaged, and an expectation that this will be enjoyable and worthwhile. It includes calling on a repertoire of positive experiences that enable someone to “read” a new environment or a new occasion and therefore recognise when and how to relate to, and care for, others. Edwards and D’arcy (2004, p. 149) comment that relational agency “is a capacity to recognise and use the support of others” for a particular goal. The teachers and university researchers at Taitoko discussed a number of initiatives during the two years of the research project, and went ahead to introduce some of them. We describe them as “gateways”, after the work on personalising learning by David Hargreaves.

What then were some of the entry points or gateways for participation and engagement and providing new learning opportunities for the children and whānau?

Gateway one: The playgroup

The establishment of a fortnightly playgroup for children under two years of age provided a means of access and participation for parents and whānau in a variety of activities.

At the onset of the parent support and development initiative, playgroup participants were asked for suggestions about possible activities, workshops, speakers and so on. Over the course of the research project, the playgroup had grown in numbers, became a weekly event and supported parents and whānau in many ways. Interviews with playgroup participants provided the following evidence of the effect of the playgroup in their lives.

Tina is a single parent of two who lived with her mother and accessed support from the disability services for herself and her daughter. The teachers at Taitoko Kindergarten realised the skills Tina had and had been employing her on a casual basis at the kindergarten to carry out tasks which Tina felt comfortable doing. She had become enthusiastic and engaged with the playgroup, her child’s learning and the running of the kindergarten:

| Tina | I just love it, coming to playgroup. Talking about different things, what’s going to happen? You know just interesting stuff like what’s going to happen and what’s gonna for the kids. ‘Cos you know like my daughter you know, she’s a bit slow at the moment, I need more information about how I can get on with her.

Yesterday she was doing a puzzle and she got the right puzzles in the night places. I was shocked to find she could put the right puzzles in the right place. |

Tina also talked about the value of the cooking classes that had been instigated through the playgroup:

| Tina | Sometimes I come to Wednesday’s cooking. |

| Interviewer | Is that good? |

| Tina | Yes that’s good. Yeah we have lunch here and we have meetings and yeah. |

| Interviewer | Do they teach you different ways to cook? |

| Tina | Yeah. And cheap, too, cheap you know how to get cheap budgeting, how to budget your food. What’s the cheapest prices. Yeah. |

| Interviewer | And that’s been good so you’ve been able to follow that up at home? |

| Tina | Yes. When I first tried I cooked some sweet and sour sausages. That’s what I tried out at home. It was nice. ’Cos you get the like the budget sausages the precooked ones instead of beef and yeah, have to get the cheapest ones. |

Regular visits from the public health nurse to the kindergartenhas meant parents such as Tina could access information and help without the barriers of having to make an appointment and get into town. Tina commented: “I like talking to a health nurse about my problems.”

Hinemoa has four children and had recently come to the live in the Taitoko community. The playgroup provided Hinemoa with an opportunity to make friends and feel less isolated:

| Interviewer | So how many times have you been to playgroup Hinemoa? |

| Hinemoa | Three times. |

| Interviewer | Three times right, right, and what made you come? |

| Hinemoa | Just to get out of the house. Bring my boy here. |

| Interviewer | So do you live quite nearby? |

| Hinemoa | Yep just up the road. |

| Interviewer | And how did you find out about it? |

| Hinemoa | Um well Caryll was the one that told me to introduce myself to everybody when I first came here. |

| Interviewer | Did you see the notice at the door? |

| Hinemoa | Yep. |

| Interviewer | ‘Cos they have a little thing at the gate don’t they and you saw it did you? |

| Hinemoa | Yep. |

| Interviewer | And have you enjoyed them? |

| Hinemoa | Yep. I get to meet all the mums and I even get invited to their house. |

| Interviewer | And do you go? |

| Hinemoa | Yep ‘cos I got no family here. |

| Interviewer | Okay. |

| Hinemoa | So there’s only just me and my kids. |

| Interviewer | So you’ve made quite a few friends through playgroup? |

| Hinemoa | Mmm uh huh yep. They’re good. |

| Interviewer | Well it’s good that you get this opportunity to meet other people. What do you think it would have been like if you didn’t have the playgroup to come to? |

| Hinemoa | Oh um I probably be sitting at home, walking around, wouldn’t know anybody. |

Hinemoa also spoke about the value of kindergarten in relation to her child’s learning:

| Hinemoa | My daughter she’s been learning a lot, doing puzzles. She enjoys it, enjoying being here. She comes home with all different ideas like she come home and learnt how to put puzzles all together. She’s quite smart. Yeah. She just enjoys being here. |

On the morning the researchers interviewed the playgroup participants, Hinemoa had baked a cake for morning tea.

Sarah was attending playgroup even though she did not have any very young children, and her youngest child had just started school. Sarah commented on how being involved in playgroup and coming to the kindergarten on a regular basis had helped her with her parenting:

| Sarah | I think I’ve been for well probably just about since it started. |

| Interviewer | Have you. |

| Sarah | Because I had a daughter here my daughter’s done kindy here and my daughter’s nine now and I’ve just stayed involved in the kindy and my fiveyear-old just only left last week. But I like the environment here and like hanging out. |

| I think it’s just the people here you feel so nice well they, Caryll and them, are so nice and you just feel like being around them and catching up with their aura you know. | |

| Interviewer | So what does that mean catching up with their aura? Tell me because it’s a lovely expression. What kinds of things are you thinking of? |

| Sarah | Well picking up on their vibes and that and their well, how do you put it? Their positive vibrance and that and the way well their calmness and that the way that they treat the children and that. I’ve noticed that since I’ve been coming a lot I’m adopting that in my home life with my kids because I was a screamer. Because my mum was a screamer and I ended up being a screamer and I hated it. It used to drive me crazy but I like the environment here it sort of calms you down and you can look and see how they deal with things. It’s not like don’t do that ‘cos I’ll slap you, it’s like don’t do that because I don’t like it. It’s like a learning thing for me as a parent. The way that we’ve been brought up isn’t always the best way. It’s good to get other ideas. |

| Interviewer | So you think you’re changing the way you’re bringing up your kids? |

| Sarah | Yeah definitely yep. ‘Cos I’ve got five kids I don’t get out and socialise, I don’t get out at all and so socialising with parents you know they have got kids so we have things in common and that and it’s nice to talk to other parents and other mothers and that. It makes you feel not so alone as well ‘cos sometimes you feel like why are my children doing that? Why are they doing that for? Oh my gosh I’ve failed and they’ve failed and the more you think that but when you talk with other parents you clarify things that I’m not the only one in this boat sort of thing. |

Karen has three children, one of whom attended kindergarten and another whom she brought to playgroup. Karen liked to be involved at kindergarten and because her partner worked night shift and slept during the day, she found being at the kindergarten and helping out enabled her partner to sleep undisturbed:

I love it. I spent like when I drop off (my daughter) at 8.30 am and I’m here until 5.30 pm everyday. I just help out or just hang around and play with the kids.

It’s kind of relaxing even though the kids are running around. Even when my kids are here I can kind of just sit and have a cup of tea and talk to other mums and I know that the kids are good. Well you know if you’re having a really bad week or something there’s always someone here that you can talk to whether it be a teacher or a parent. It’s just about we work together really well.

Karen had been involved with the cooking classes that the local SuperGrans were taking at the kindergarten at the request of the playgroup parents. Karen had a chef background and enjoyed taking a leading role in the cooking classes.

Recently the kindergarten changed its hours of operation and had some children attending from 9.00 am to 3.15 pm. At the suggestion of the parents, lunch was being provided for these children at a low cost three days a week and Karen was organising the menu and doing the preparation and cooking for these meals.

Makeleta was employed by Group Special Education to assist a child with disabilities at the kindergarten and also as a kaimahi at the kindergarten so did not always have the opportunity to attend playgroup but nevertheless found the times she had attended to be beneficial:

| Interviewer | So what do you think is the value, what is good about playgroups for these parents? |

| Makeleta | I think it’s very good. Like it’s encouraging us to teach our own children and to value things the school values and, like for me, coming from the Islands, we don’t usually have books. |

| Interviewer | In Tonga? |

| Makeleta | Yeah. Our nana’s they just tell us stories and lessons about things about stories about the island and about what happened in the islands. That’s how we get to know all those stories. We don’t have books but like what we did today, it gives me an idea of how important books are. It’s really good ‘cos I see things through playgroup we learn more things about what we don’t know and we don’t value. And how like for myself, I got five children and sometimes I think they only start to read books when they get to primary school. Like now, I’m thinking to myself that I should start reading to my 13-month-old daughter ‘cos I haven’t read any books to her. I was thinking that she is too little for that. Like now, like it’s a new thing for me. That I should start reading now. |

| Interviewer | Hmm well you can get some of these from the library too or borrow them from here. |

| Makeleta | From here, yeah (laughs). |

| Interviewer | So what other things have you learnt or have been good about playgroup? |

| Makeleta | I learnt more ‘cos this one time when I came to playgroup I learnt that they had this guest speaker that was talking about the fat in the food. It’s really wake me up to be aware of what I’m eating, yeah of what I’m eating. |

| I learn a lot from playgroup. Things that you’re not aware of and things that you think that the way that you’re doing it is all right, but when someone comes along with another idea, you think that the one that you have is not good enough. The best is not yet to come. So that we are learning new things I think that it’s very good and you learn to meet other people as well. |

Makeleta had applied and been accepted to do her Diploma of Teaching Early Childhood in 2009 and was to be based at the kindergarten for 15 hours a week for field experience.

Gateway two: Children’s portfolios

Before the TLRI project, teachers had been writing learning stories and revisiting them with the children. During the project, the teachers began to send them home regularly in an “official” book bag—a bit like the school book bags—and invited families to read the stories with their children. The invitations became more insistent with the inclusion of a “whānau voice” formatted page. The “whānau voice” page was also redesigned to encourage contributions. After the introduction of the practice in which portfolios were systematically sent home, there was a marked increase in parent/whānau contributions. By August 2007, there were 37 portfolios that contained a whānau comment, and two of these portfolios included two comments. Twenty-five of these comments were dated August 2007, when the portfolios began to be sent home.

The following is an analysis of those 39 contributions:

- comments about the portfolios, in general, as an artefact (17)

- messages from parents and whānau to children about their work (11)

- comments from wider whānau members (6)

- children talking about kindergarten at home/singing songs and so on (7)

- specific comments about progress in curriculum (19)

– bringing information home (1)

– extending interest from home (1)

– paintings and drawings (3)

– loves books (1)

– writes name (5)

– counting (1)

– puzzles (1)

– shapes and colours (1)

– learning to balance (1)

– team work on construction project (1)

– comments on work child brings home (art and creativity) (2)

– curriculum suggestions (1)

- language development (3)

- comments about children’s general progress, achievements (13)

- behaviour improvement (2)

- comments about friends and social interactions (10)

- home activities described (2).

These responses demonstrate an intelligent awareness and understanding of children’s learning by parents and whānau.

Teachers continued to encourage children to take their portfolios home whenever they wished and from time to time systematically ensured that the portfolios were taken home. By mid-2008, the teachers had added their own profile pages and there was a Samoan teacher. There were 14 new contributions, one in Samoan, and two comments about the teachers’ profiles:

- comments about the portfolios, in general, as an artefact (8)

- comments from wider whänau members (2)

- children talking about kindergarten at home, singing songs and so on (1)

- specific comments about progress in curriculum (4)

– paintings and drawings (2)

– writes name (1)

– extending interest from home (1)

- comments about friends and social interactions (3)

- comments about children’s general progress, achievements (6)

- comments about the inclusion of teachers’ profiles (2).

The following comments were made by whānau, a year apart (in 2007 and 2008):

| August 2007 | Ngauru really enjoys coming to kindy and is really excelling. Thanks to all the teachers. |

| May 2008 | Ngauru enjoys showing her book to all her whānau, nans, koros, aunties, uncles. Ngauru’s whānau are so impressed with all the learning experiences she has had. Thank you. |

| August 2007 | The book is awesome. I am glad to see that my son is interacting with other children and learning so much, over the months since Ngakau has been at kindy the family has noticed a big change in Ngakau. Thank you Taitoko kindy. |

| March 2008 | As Ngakau and myself read through the book it was nice to hear my son explain things to me with excitement and enthusiasm. I see Ngakau has achieved a lot since he has been at Taitoko Kindy interacting with other children and the teachers. Thank you Caryll, Tania and Michelle for opening a whole new world in Ngakau’s eyes. His book is beautiful. |

| August 2007 | Calvin: Daddy says your kindy book is awesome! It is nice to see you being part of a group and playing with your friends. Calvin: Mummy loves looking at your book with you and talking about all the people in your photos. It is neat to see you with your friends in the photos as you often talk about which of your friends you are going to play with. |

| March 2008 | (a comment from Calvin): ‘It looks flash’ Daddy said this about my book. Then mummy took a photo of us reading my book in bed. |

Comments in response to whānau contributions

Teachers also started to write comments back to parents and whānau and the comments included these in the child’s portfolio to validate and encourage contributions from parents and whānau:

| Whānau | I love Tyson’s profile book, it is so full of colour and I love to look back on the things he has done. The work he has done with his name is great and maybe I should get (brother) to help practise. The trip to Kiwi Moon looked like such a fun day. Tyson was worn out, can’t wait to see what other stuff will fill these pages. | |

| Teacher response (with photos of all the teachers) | ||

| Thank you for your comments Tracey. We love getting feedback from parents about their child’s learning. Tyson is doing awesome work, isn’t he? It will be great if Tyson and (brother) practice those letters together at home. It is always fun to learn alongside someone else. Kia ora again for your support. | ||

| Whānau | [I like] that Shyanne is having fun at kindergarten, that she is joining in and learning to play with other children. She is enjoying painting—I notice that she is painting faces instead of just circles and that she is making friends too and enjoying playing with other children. | |

| Teacher response (with photos of all the teachers) | ||

| Thank you for your comments about Shyanne’s work and her profile book. Like you, we can see that Shyanne is really enjoying herself at kindergarten these days. Today when I was watching her playing with (name) in the trolley I noticed her laughing out loud and having lots of fun. It is so good to see her making friends as well. It is exciting to see her progress in the art area and that she has moved from making circles to now putting eyes, nose and mouth on them. We will be watching this learning closely so watch the profile book for a new story soon. |

||

Photos of whānau sharing the portfolios with their children

The capturing, by digital camera, of children, parents and whānau sharing portfolios at the kindergarten also heightened the engagement of parents, whānau and children in learning by revisiting learning stories and having dialogue about the content. The images of children, parents and whānau sharing portfolios were displayed on the wall next to the shelf and couch where the portfolios were kept. They were also included in the books with a caption or a commentary. The following is an example:

Vasilotu, you really enjoy looking in your profile book to see if there are any new stories there. Today your Mum, Mavae, was at kindergarten, and I saw the two of you enjoying sitting on the sofa checking out your work. Over the past week or two you have done some wonderful drawings of your family and you have wanted to put them in your book. When I looked at them I could see that you had not only drawn your Mum and your Dad, but also some of your Aunties and cousins as well. Poto Vasilotu, you are such a capable girl and you have a great understanding of, and, interest in literacy. You can write your name, you can represent your thoughts and ideas on paper and you are also very able to communicate those thoughts and ideas verbally. What an amazing girl. We love having you at Taitoko Kindergarten.

Incorporating whānau comments into a learning story written by the teachers

The teachers were aware that many of the parents and whānau in their kindergarten community had not had positive educational experiences and could feel intimidated when asked to write comments in portfolios. Thus, by recording parent comments on their daily session “debrief” sheet, they were often able to then incorporate those comments into learning stories. This showed parents and whānau that their input was valued and appreciated and could encourage further engagement in their children’s learning.

Gateway three: Digital camera and “Spotty Dog” go home

Another initiative by the teachers after discussions with the researchers was the adoption of a kindergarten “mascot” (Spotty Dog) that could be taken home with children, along with a spare digital camera. Spotty Dog, a soft toy, had lived at the kindergarten for some time. He now became available for visits to families, and he came equipped with a backpack for carrying, and a digital camera for taking photographs. Whānau were invited to take Spotty Dog home overnight or over a weekend, and to record his activities on the digital camera. On return, the teachers added a text, dictated by the child or the family. Sometimes the whānau had already written the story of Spotty Dog’s adventures by hand, and sometimes on the computer.

Spotty Dog initially went home with the teachers, to set up his portfolio. The teachers took photos of him participating in everyday events at their home environments. The families then did the same, so that the children then had photographs of siblings, parents, grandparents, aunties and uncles in their portfolios. Te Whāriki (Ministry of Education, 1996) suggests “the curriculum builds on what the children bring to it and makes links with the everyday activities and special events of families, whānau, local communities and cultures” (p. 42). These events are shared with the children back at kindergarten; they provide a glimpse into the sources of “funds of knowledge” from home. The researchers were reminded of the Funds of Knowledge project by Norma González (an anthropologist), Luis Moll (an educational researcher) and Cathy Amanti (a teacher). González wrote:

The underlying rational for this work stems from an assumption that the educational process can be greatly enhanced when teachers learn about their students’ everyday lives. (González et al., 2005, p. 6)

The Funds of Knowledge project had involved visiting the students’ homes. The Spotty Dog project, inspired by a similar project in the Roskill South Kindergarten Centre of Innovation project, gave the families the opportunity to take photos and make commentary on those aspects that they were prepared to share. González writes further about “funds of knowledge”:

In recent years, building on what students bring to school and their strengths has been shown to be an incredibly effective teaching strategy . . . What better way to engage students than to draw them in with knowledge that is already familiar to them and to use that as a basis for pushing their learning? But here is the challenge and dilemma: How do we know about the knowledge they bring without falling into tired stereotypes about different cultures? (González et al., 2005, p. 8)

The Spotty Dog project was an invitation to engagement with a loved character across the border of the kindergarten, and the write-up remained as specific stories for sharing and revisiting. It also became somewhat demanding for the families, since taking Spotty Dog and the digital camera home was very popular.

The aspects of home that the first four families took photos of or commentated on included:

- Spotty photographed with relatives at home and at auntie’s house, going to the supermarket, going to the Warehouse and sleeping with Te Raka (his “Daddy” for the weekend)

- Spotty driving the car, playing Housie, eating and being photographed with relatives y visiting “Pop” (101 years old) at a rest home, assisting Ngauru to make scones, sleeping with baby brother, having a ride in granddad’s truck and playing in a tree hut

- Spot reading Calvin’s “kindy book” to him, eating tea, sleeping with Calvin one night, and with his younger sister another, watching Calvin swim and spinning around.

Like the portfolios themselves, the stories about Spotty Dog might be described as “boundary objects” (Lemke, 2000, p. 281), objects that belong in two places and provide an entry point for conversations and communication across different settings and different time frames.

5. Relationships and Relational Agency

Relationships and relational agency: Research question 2

The second research question asked: What strategies can further strengthen the relationships with the community, and provide enhanced learning opportunities for the children and parents and whānau?

One of the very strong recurring themes that have emerged from the research was the importance of relationships. The teachers realised that it was the building of responsive and reciprocal relationships that provided the foundation for empowering and supporting parents. In a community where professionals were likely to be viewed with suspicion and distrust, the accepting of parents and whānau for their skills and knowledge by the teachers at Taitoko Kindergarten was important in enabling parents and whānau to feel valued and able to make a contribution to the community and their children’s learning.

Our major interest was the children’s learning, whānau relationships, and the intersection between these two. We have borrowed the term “relational agency” from the work of Anne Edwards and her colleagues at the Centre for Sociocultural and Activity Theory Research at the University of Birmingham (Edwards & D’Arcy, 2004; Edwards & Mackenzie, 2008). Edwards and D’Arcy write about the social practices of settings in which the dispositions for collaborative engagement are developed and enhanced. They are writing about school and classroom curriculum, but the idea is relevant here. They call for:

versions of pedagogy (teaching and learning) which aim at strengthening pupils’ capabilities for learning (Bereiter, 2002) through enhancing their dispositions to engage with and transform features of their worlds. (p. 147)

We would change the word “pupils” to read “children and whānau”. In Te Whāriki (Ministry of Education, 1996) terms, relational agency is a combination of the four principles:

- Whakamana/Empowerment. The early childhood curriculum empowers the child to learn and grow. The notion of agency is about being empowered.

- Ngā hononga/Relationships. Children learn through responsive and reciprocal relationships with people, places and things. Relational agency is about engaging with others and helpful resources.

- Whānau tangata/Family and community. The wider world of family and community is an integral part of the early childhood curriculum. The view of the research project is that children’s learning is closely connected to the recognition of learning opportunities by the whānau.

- Kotahitanga/Holistic development. The view of learning that the project is interested in is reflected in the five strands of Te Whāriki, with an emphasis on learning dispositions and working theories.

Relational agency is about enabling and being enabled to recognise and use the support of others. The parent support and development initiative is about the support of others for health and wellbeing. Our interest was the support of others for an understanding and interest in education. Relational agency is a disposition, and the work at Taitoko Kindergarten was designed to strengthen the aspirations and understandings of education for whānau and children in ways that would continue beyond the kindergarten. The wider view of relational agency is that the opportunities for support and helpful resources are available and accessible.

Comments from whānau about the parent support and development initiative

The following were comments from the 12 family members who responded to an invitation to comment on the parent support and development initiative in September 2008. Almost all of them were about the warm and relaxed relationships:

I like detailed profile work and reporting back to parents. Staff have more time to do this and I like it. (Chanel)

I like the work put into profiles. Colourful, well done, good information. My child is seen as an individual. (Tracey)

I like this place heaps better than when my nieces were here. More learning for the children. Like the extra activities for parents. Netball and Coffee morning. I like it! (Samantha)

Kindergarten is now more family orientated. Not just for the children but it involves the whole whānau. (Kirstie)

More community-orientated and opportunities for links to the community, school etc. (Maria)

I like the flexibility. I feel OK about staying. It feels a good place for adults too. (Corall)

I like the way diversity is celebrated. (Jeanette)

A friendly place. I like the groups for parents. (Jashana)

There is more time. Teachers have time to talk to parents. (Horiana)

Nice and relaxing here. (Jo)

People awesome. My daughter loves coming and talks about kindy all the time at home. ‘I did a puzzle today.’ She even wakes me up to take her. I like that she has made a friend too. (Hiria)

The final comment was not directly about relationships, except in the sense that it appeared to be about enhanced communication between the parent and her child, with the educational experience at kindergarten as the topic:

What I like is that my child is more open. He jumps in the car and tells me all about what he has done for the day. Like, singing me a song he learned at Kapa haka. (Azonette)

Relationships: People

The teachers

Threaded through this report are comments about the relationships between the teachers and the kindergarten community. As for Karen, a parent who had found the whānau tangata centre a place to use her many strengths and skills, it was the attitudes of the teachers that allowed parents and whānau to have a sense of belonging and worth. This is evidenced in Karen’s comment about the community and the kindergarten:

This is classed as a low decile area and I don’t think this kindergarten reflects anything like that. These teachers don’t put that kind of image forward around here. Nowhere does it say that this is a low decile kindergarten and therefore, you know, we shouldn’t have good resources, we shouldn’t have good teachers and things like that. The teachers are very professional, Caryll is one of the most professional ladies I have ever met. She comes from a very different background to all of us but you’ll never know it talking to her because she will never look down at you because you do this or you live like this and you wear these clothes.

Administrative support

Carmella is the administrative support person at the kindergarten. Her role became multifaceted. Her skills with information and communications technology (ICT) enhanced the learning stories and the newsletters. Her older children have all attended the kindergarten, and her youngest child, born during the project, will also attend Taitoko Kindergarten. When Carmella was a kindergarten parent, Caryll, the head teacher, recognised Carmella’s strengths, and invited her to apply for this part-time position. She made a positive contribution to the playgroup. The following interview with Carmella demonstrates her influence and advice in setting up the playgroup:

I thought well it was something to draw the mothers, the parents together and for under two children. Parents for under twos what it has sort of focused on and I thought a coffee group morning tea was a more ideal starting point for that. So yeah we weren’t really sure how it would go it was sort of a trial and error thing. It’s gradually got better. We knew from the start that that it wouldn’t draw a lot of attention first. It takes a lot of time for people to get out and come to familiar things around this community. I said ‘It will gradually get there.’

It was quite slow at the start but it’s picked up a lot yeah and it’s good to see a lot more mums coming from the community. The good thing about it is the speakers I suppose, learning about different things you know you find some interesting stuff, you know, the slightest things, a nurse might come and talk about asthma and you think you know everything but you don’t. It’s good having the education and health sectors like nurses or teachers coming to talk about books. Just how you know to teach you about things for your children when it comes to the health and welfare of them I suppose. You know just teaching their strategies of learning and giving you ideas, which I think has been the main thing for me. It’s getting a lot of ideas and you know that saying that you learn something new everyday and it’s sort of just what goes here.

Kaimahi

The parent support and development contract provided funding to employ two kaimahi (cultural aides), one Māori (Daveida) and one Tongan (Makeleta). The kaimahi attend kindergarten sessions and work both with children and parents and whānau. They are able to assist teachers with language translation and protocols and with developing a greater understanding of cultural responsiveness. Language support has also been enhanced by the recent employment of a Samoan teacher, Rasella; language has become less of a barrier to engagement and communication.

The following comments by Carmella and Rasella demonstrate the importance of the kaimahi in making the kindergarten environment accessible and responsive to these families:

| Carmella | We had a parent come here the other day that had only been in New Zealand for six weeks and she could only speak like 10 words of English. She come in and she was saying to one of kaimahi that she liked coming here because if she can’t get something across in English she can turn to them and they will be able to relay it for her. She sat here for about two or three hours one day listening to everybody and you can even see in the last couple of weeks that her language skills have developed that much more. By feeling comfortable because there is someone here that can understand her but also having other mums and teachers around that don’t treat her different ‘cos she is different. |

| Rasella | Before I was here they used to come here and drop off their children and took off. Sometimes they come here, the Samoan born they come here and drop off their children and talk to them in Samoan. They want to talk to them but are not confident enough to talk to them in English. They think they might say something wrong …

Even the New Zealand born she said ‘Sometimes I can say hello and go but now I’m feeling, I’m feeling that I want to stay’ and I said ‘Tell me the reason why’ [and she replied] ’Cos you’re here.’ |

Daveida is a highly respected member of the community and as the whaea of the kindergarten, mothers, in particular, seek her out for advice. She has had children attend the kindergarten in the past and now her mokopuna are coming to Taitoko Kindergarten. Thus, she knows many families and her mana is recognised in the community. Kaimahi contribute to children’s portfolios and the recording of comments and stories from whānau where appropriate. They often feature in the stories. In one example, Tania wrote about Daveida helping one of the children complete a floor jigsaw of a digger. (Tania commented in the story about the child’s perseverance, and, knowing the family well, she wondered if this was the same as the digger that the child’s uncle had.)

Senior teacher with the Wellington Region Free Kindergarten Association

The Wellington Region Free Kindergarten Association initiated this TLRI research project because it wanted to be sure that relationships to do with the children’s learning was central. During the TLRI research project, the senior teacher attached to Taitoko Kindergarten (Margaret) attended most of the meetings. Frequently she would offer ideas about the project and how the association could assist. Commenting on her assistance to Caryll in the six months before the TLRI project began, she said:

I suppose the way I supported Caryll was from my experience of setting up PAFT [Parents as First Teachers] in Porirua, because I had set up something from scratch and had to go out and do all the networking and working with agencies. Plus all the experience I have had of doing Milestone reports was invaluable. I knew what Caryll was faced with, but, you know, Caryll is wonderful and it didn’t take long. I just kept pulling back as fast as I could but set it up hopefully (so) that the processes we’ve set up are fail safe . . . And so I actually went with her to do some of the early networking but that didn’t last long because she’s such a natural and she took over and got into it.

This policy of sensitively sharing the leadership continued during the TLRI project. We have written more about the contribution to the project by both the senior teacher and the general manager in the section entitled “Willing leadership”.

Relationships: Artefacts that contribute: Teacher profiles in the portfolios

As another attempt to strengthen and build relationships the teachers decided to put together a page each about themselves to place at the front of children’s portfolios. It was hoped that these “profiles” would provide connections with families and break down barriers by allowing parents and whānau to have some knowledge about each teacher. The teachers felt that this modelled reciprocal relationships and might encourage parents and whānau to share things about themselves.

The teachers have recorded comments by parents and whānau in response to their “profiles” and in some cases include them in children’s portfolios. Parents and whānau have commented in their contributions about these profiles. One comment states, “We also like the teacher profile parts, it’s nice to know a little about the teachers” while another parent states, “It’s awesome to learn about the teachers.”

Relationships: Artefacts that contribute: Displays on wall

When the university researchers visited the kindergarten they photocopied some of the stories about the children that were on display near the entrance to the centre. This was a place where families and visitors hovered before they entered the busy activity area of the kindergarten; it was also readily accessible to the playgroup families.

This wall display was continually kept up to date. On this day, the most recent addition was dated 15 September, and all the stories were dated August or September, except for one that documented continuity in learning from July to August (George’s strengthening interest in lawnmowers). These were copies: the stories were also filed in the children’s profile books, and would therefore have been available to the families.

We chose 11 stories that referred to connection with community, and we analysed them for the research project in terms of theme and messages about learning. The themes were:

- transition to school: two stories about new entrant teachers visiting the kindergarten y people: photos of family, teachers and new entrant teachers at the school

- connections to the community and the children’s world outside the kindergarten: a child’s trip to Kaitaia with her grandparents, a comment about an uncle’s digger, a trip to the library, an interest in lawnmowers, an event in the kitchen at home where Jayden was a hero

- recognition of home language: a story written in English and Samoan.

The valuing of conversations with children

All of the stories were addressed to the child, and in a number of cases they included the children’s comments. George made a hope and a prediction that when his mother came to pick him up, “Maybe she will bring my baby.” Janice told the story of her trip, beginning “I’ve been on a holiday on my granddad’s house bus.” In Robbie’s Dad Works at the Beehive, the teacher recorded a conversation she had with Robbie and she commented on the long drive that he had from Paraparaumu to kindergarten; the text included: “Then we talked about your Dad whose name is Rob, which is the same as your name. You told me that he works at the Beehive in Wellington. He has a long journey too, and you said that he goes in the train and the car.” In the second story about George’s continuing interest in lawnmowers, the conversation was about his plans to go to buy a lawnmower and he added: “You know Caryll, A. touched Aunty Rose’s lawnmower when Aunty said not to!” (Caryll added the comment that she was impressed that he knew that touching lawnmowers was not a safe thing to do.) The texts added: “We looked closely at the picture and you wondered how the catcher at the back would stay on so we talked about whether there would be some clips or a special bolt to hold it on.” Jayden Saves the Day recounted a story told by Jayden and his mother, when Jayden went into the kitchen and yelled out “Mum, Mum your tea towel is burning!”

Children can read the stories

These stories were re-read to the children at the kindergarten, and went home to families in the profile books. They included good-quality digital photographs, and visual images imported from the Web that illustrated the story. In the story Janice’s Big Trip up North, the teacher writing the story included a map of New Zealand with Levin and Kaitaia marked, and went to the grandparents’ house to photograph the house bus. In Robbie’s Dad Works at the Beehive, the teacher and the child together went on to the Internet and “found this picture of the Beehive” which they included in the story. One of the two lawnmower stories was decorated down the margin by a series of pictures of different lawnmowers.

Continuity of teaching and learning and relationships

Most of these stories included plans to extend the learning or a comment about continuity of relationship. The comments, occasionally abridged, are included here; the numbers refer to the stories in Table 1.

- … in a few months you will be off to school. You will have to pop in sometimes and visit us next year, so we don’t miss you too much.

- … we hope he (baby brother) comes to Taitoko Kindergarten when he grows up a bit.

- Maybe we could go on to the internet and check out some other diggers.

- I think we will see if there are some other stories about Duck in that series. I think I have seen some at the bookshop, so we will have to go shopping so we can have some copies on our kindergarten book shelf. I look forward to our next story time together.

- I wonder if it was the Ninety Mile beach?

- Maybe your Dad could tell us about the Beehive, and some of the people he sees there?

- George, I wonder what other things you know about lawn mowers; I will have to sit down and listen to your other ideas about lawn mowers.

- After I had finished talking with you, I did some thinking about how we could extend your interest, and had an idea that Mr B from Taitoko School mows the school lawns on a ride on mower! George, do you think we should call out to Mr B over the fence and ask him if he could show you the mower, and maybe he may let you sit on it, and look at the controls and we could ask about how the catcher is attached!

- It is not long now until you will be leaving us and going off to school, where you will see Mr Harry and Priscilla (in photograph) every day.

Table 1 includes the themes and the messages about learning in the September wall display.

| Story | Theme | Messages about learning | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Elias’s Teacher from Levin East School Comes to Kindergarten | Transition to school | There is a continuity in activities, environment, caring and learning from early childhood education to school. |

| 2 | We Get to Meet George’s Baby Brother | Family as part of the kindergarten community | Children’s conversations and contributions are valued.

|

| 3 | Working Together | Problem solving (jigsaw) together with Nan

Connection with “Uncle Jarrod’s digger” |

Listening to others and thinking are central to problem solving.

Completing a self-set task. Comparisons across contexts (this jigsaw, Uncle Jarrod’s digger and the Internet). |

| 4 | Where’s Duck’s Keys? | A trip to the library. Reading to teacher | Reading stories and interacting with books are a great way to learn. |

| 5 | Janice’s Big Trip up North | Telling a story of a trip away from kindergarten | Retelling a real life story is valued, and a map can provide background information. |

| 6 | Robbie’s Dad Works at the Beehive | Connecting child and Dad’s journey to “work” | Conversations with the teachers can be as reciprocal as talk between adults. |

| 7 | What Great Mathematical Concepts | Home language and Manu Samoa haka | Creative additions to a cultural format.

Home languages are valued. Teaching others. Counting in a meaningful context. |

| 8 | Lawn Mowers (i) | Pictures in a book made by Nanny: Nanny is a teacher too | Being engaged in a strong interest is both possible and desirable.

Sharing discoveries with teachers. |

| 9 | Lawn Mowers (ii) | Connections to machinery and lawnmowing outside kindergarten | Continuity—strengthening and deepening an interest over time—is a key aspect of learning.

Wondering and talking about an interest is part of this learning. |

| 10 | Jayden Saves the Day | A story about heroism in the home kitchen | Storytelling is part of the fabric of reciprocal learning at kindergarten.

Being alert and helpful. |

| 11 | The New Entrant Teacher Visits Manaia at Kindergarten | Transition to school | Teachers at kindergarten and at school are interested in the contexts of children’s identities as learners: being a bus driver, a train-set player, a painter. |

Relationships: Artefacts that contribute: T-shirts and social netball

Two unintended initiatives that assisted in strengthening and widening relationships with the community were the provision of T-shirts that included a logo for the Taitoko whānau tangata centre, and the formation of a social netball team.

T-shirts

The T-shirts were produced by the Wellington Region Free Kindergarten Association for the staff, children and parents and whānau to wear at the official opening of the whānau room in March 2007. In the ensuing months, teachers, children and parents and whānau wore their T-shirts regularly. This resulted in the community becoming familiar with the whānau tangata centre and generated interest and questions from members of the wider community. The T-shirts were worn with pride and they have been reproduced to meet demand.

Social netball

One of the teachers, Michelle, was involved in netball and decided to see if she could recruit parents and whānau to join the local social netball competition. A team from Taitoko Kindergarten participated in this event for the past 18 months. The team comprised parents and whānau (both female and male) from the kindergarten and a number of other people from the wider community; some members have been consistent attendees while others have come and gone at various stages. In order for the netball team to continue to participate, the Wellington Region Free Kindergarten Association paid the weekly team fee so that this was not a barrier for parents and whānau wanting to play. The involvement in the netball competition has enabled further relationships to be established and strengthened and connections to be made with children and parents and whānau within the kindergarten programme.

Relationships: Willing leadership

Since her initial employment at Taitoko Kindergarten, the head teacher, Caryll, has always had a vision for the kindergarten and community. She has recognised the potential for supporting and involving parents and whānau to help strengthen the community. It was Caryll’s initiative on seeing a call for expressions of interest for parent support and development contracts that resulted in the kindergarten being successful in securing a parent support and development contract to establish a whānau tangata centre. Another key factor was the support, and later the leadership, provided by the Wellington Region Free Kindergarten Association. The fact that the management of the association was prepared to support an application and then provide time and resources to formulate the application has been pivotal in the success of the parent support and development initiative. It has been the expertise and strong relationships between the Taitoko teaching team, their senior teacher from the Wellington Region Free Kindergarten Association and the association’s general manager that have facilitated many of the initiatives to do with those aspects of the parent support and development contract that provided the foundation for the TLRI research project.

The attitude of all these leaders was that the process of strengthening responsive and reciprocal relationships in this whānau tangata centre was about removing barriers and viewing people as capable and competent. The general manager talked about the importance of providing opportunities and breaking down barriers:

If you really believe the children are competent and confident then you must believe their parents are and you must believe therefore that the teachers are. So if you provide, cut down the barriers and provide the support then hopefully they’ll run with it and that’s what’s been really good about this (project).

The willingness of people in leadership roles to provide opportunities and use resources to remove barriers has been particularly significant in ensuring that relationships were strengthened and nurtured.

Parents and whānau as leaders

Throughout the research project, a vision for the community has begun to emerge and take shape. This vision is based on teachers’ beliefs about communities of learners. Through the provision of an “under-twos” centre for 2009 and through continuing to strengthen the relationship with the school next door, the teachers see further possibilities opening up to support parents and whānau to develop leadership roles within the community.

The instigation by the parents and whānau of a holiday programme at the kindergarten during the summer break has been supported by the teachers in that they have helped provide the opportunity and removed barriers so that this can become a reality. This initiative is being led by the parents and whānau and it came out of their desire to have some activities and “another place to go” for their children to help alleviate some of the boredom and tension that can arise during the long summer break.

This initiative provides clear evidence of the willingness of the teachers to see the community as leaders and learners and view them as capable and competent in meeting their own needs.

As has been mentioned previously with respect to the change of kindergarten hours and children staying over lunchtime, it was at the suggestion of the parents and whānau that healthy lunches be provided for the children three days a week. Karen, one of the parents with a background and interest in food, took a key role in this. It is the vision of the teaching team that parents and whānau will continue to develop leadership skills and take on leadership roles.

Relationships: Local legend in curriculum and transition-toschool profiles

This TLRI project continues to be work in progress. A number of initiatives were being developed towards the end of 2008.

Inclusion of local legend in curriculum and portfolios

An initiative that is still developing is through the relationship with the local kaumātua. The teachers have been keen to introduce a relevant local legend to the children and include it in portfolios to provide another gateway for making connections. Visits and discussions by the kaumātua and his wife are helping meet this goal and is hoped that this relationship will also provide support for the community.

Transition-to-school profiles

The teaching team had been reflecting on their transition-to-school practices and in discussions with the researchers decided to put together a transition profile for children going to school. This profile was to make connections between Te Whāriki (Ministry of Education, 1996) and the key competencies in the new New Zealand Curriculum (Ministry of Education, 2007). The teachers and researchers had designed a template that connected selections from the work in the children’s portfolios with the key competencies. This initiative was first trialled with the last child who started school in 2008.

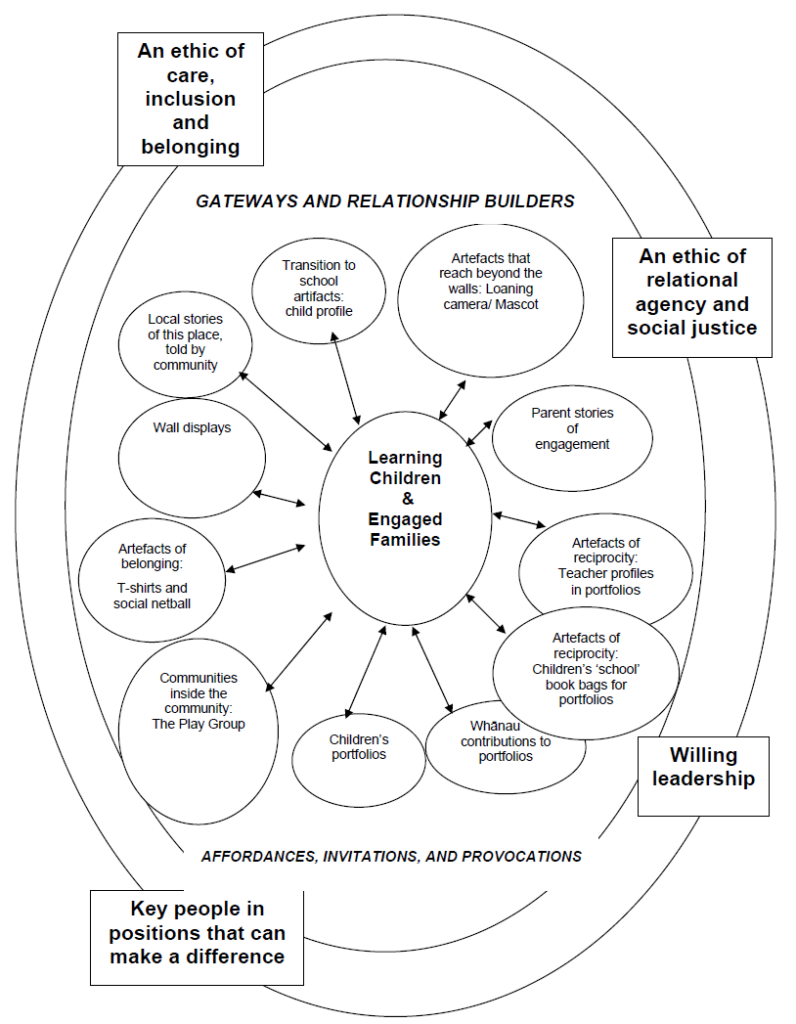

Strategic and practice value: A framework

Support and helpful resources may be available, but they may not be taken up. We have found it useful to adapt a framework in Claxton and Carr (2004), developed to describe teaching, to suggest that these opportunities for support and helpful resources can be described in terms of increasing demand as (a) affordances, (b) invitations and (c) provocations. An affordance is there, physically available, but may not be noticed or recognised as significant for an understanding of education in its widest sense by whānau or children. Play equipment in the kindergarten, for instance, may be seen as keeping children happy. An invitation is more demanding, but it can be turned away. A wall display of the children’s learning as the whānau enter the building might be seen as an invitation. A provocation is a more insistent invitation. Sending children’s portfolios home in an official “book bag” with a page for whānau comment was a provocation.

The minimum requirement of a resource is as an affordance: this is necessary, but for many families and community agencies it may not be sufficient; invitations and provocations will be needed to make things happen. However, many families will watch and observe the way an affordance (an opportunity that is recognised as helpful) works before they accept an invitation or a provocation to participate and to be engaged

We might sum up the research project findings as three key practices that need to happen for family engagement and participation, and a culture of relational agency: (a) processes, resources and practices that include affordances, invitations and provocations; (b) an ethic of care; and (c) an ethic of relational agency.

Processes, resources and practices that include affordances, invitations and provocations

In our view, the most successful practices were those in which the level of demand could be changed. The portfolios, for instance (gateway two), afforded engagement by parents and whānau in their children’s learning—and the children’s engagement too. The teachers included invitations to revisit the portfolios with wall displays and photographs of families and children looking at the profiles together. Sending the portfolios home, in rotation, in a “school book bag”, became a provocation, and the families responded accordingly. The playgroup offered invitations, and many of the workshops included provocations (for example, to read to their children) for the families who accepted the invitations.

For early childhood centres that do not have the funding provided through a parent support and development contract but are interested and committed to engaging parents and whānau in their children’s learning and providing support to empower parents and whānau, the research from Taitoko Kindergarten offers possibilities for achieving these outcomes without extra finding.

These possibilities include:

- the initiatives associated with the children’s portfolios (such as teacher profiles, a “mascot” to take home accompanied by a camera)

- the displaying of learning that shows clear connections between the centre and home y establishing a playgroup for parents and whānau and younger children

- the building of relationships with other agencies with a view to incorporating their services into the life of the centre

- using parent and whānau “funds of knowledge” to provide support and learning for other parents and whānau.

An ethic of care

There is considerable interest in the research literature on establishing an “ethic of care” in classrooms and schools, inspired by the work of Nel Noddings (1992). This includes practices and processes that ensure inclusion and belonging. Taitoko Kindergarten had established, over time, just such an ethic. It was centred on the people (relationships one) who care about the community and about social justice. The playgroup also contributed to this ethic of care, and there were occasions when the parents and whānau rallied around other families who were sick or hurt.