1. Introduction

This Level C TLRI pilot project was conducted in 2006 at Richmond Road School (RRS), a small multicultural, multilingual school in Ponsonby/Grey Lynn, Auckland. In 2006, the school had a total roll of 350. There were 13 classes, with 15 full-time and five part-time teachers.

A key feature of RRS is its long-established bilingual/multicultural education program, which is the principal point of focus of the TLRI project. RRS currently comprises three bilingual units— Māori-, Samoan-, and French-medium—as well as an English-medium area. In addition, the school has on site two Early Childhood Education (ECE) centres, one Māori-and one Samoanmedium.

The school is designated as Decile 7, based on the increasing gentrification of the surrounding inner-city area in Auckland. However, over 60 percent of the children on the roll come from out of zone and are mostly to be found in the bilingual units, where Māori and Pasifika students predominate, suggesting that the school population is more likely representative of a Decile 4–5 school.

RRS operates, in effect, as a ‘magnet’ school, attracting parents from across Auckland— particularly, Māori and Pasifika parents—who want their children to be educated bilingually. Despite the school’s special character, RRS has not been able to secure additional funding for its bilingual programs. As a consequence of funding limits, an enrolment scheme operates on a points system to allow a controlled number of bilingual learners into RRS programs, which are capped at the following maximum numbers: Māori 80, Samoan 80, and French 60.

The three bilingual programs, which operate as vertical or multilevel whānau/rōpu, are all well established. The Māori bilingual rōpu, known as Te Whānau Whāriki (TWW), has run since 1985. The Samoan bilingual rōpu, Mua i Malae (MiM), began in 1987/8, developing out of the on-site Pacific Island new arrival ESOL reception unit at the school. The French bilingual program, L’Archipel (LA), began in 1996, in partnership with FRENZ Inc., a group of Francophone parents who wanted their children to maintain their French in New Zealand.[1]

1.1 School organisation

Further details of the current organisation of the school in relation to its bilingual programs are as follows:

- Whānau Whāriki (WW): This rōpu is based on Māori and English as joint mediums of instruction. The program was started with a Māori language revival focus in the early 1980s. Today approximately 80 percent of the children enter from Te Kōhanga Reo, the Māori medium ECE program on-site. Most of the children, however, come from homes where English is the predominant language spoken, reflecting the wider intergenerational loss of Māori in the latter part of the last century (May, 2004). Over 50 percent of children in this rōpu are also not ethnically Māori.

- Mua-i-Malae (MiM): This rōpu is based on Samoan and English as joint mediums of instruction. The program was started in 1987/88 with both a Samoan language maintenance and a language revival focus. Approximately 50 percent of the children have come from the A’oga Fa’a Samoa, the Samoan language early childhood education program on-site. While the majority of students do come from homes where some Samoan is spoken, the level of Samoan on entry varies widely. Consequently, many students in the program can be regarded as heritage (2nd) language learners rather than native speakers of Samoan. Approximately 10 percent of the children in this program are not Samoan.

- L’Archipel (LA): In this rōpu, French and English are the joint mediums of instruction. Most children come from Francophone families and backgrounds where some French is spoken at home although, as with the other bilingual rōpu, the majority of students can be classified as heritage (2nd) language learners of French. The program was started with a French language maintenance focus over ten years ago. There are very few non-French heritage children in the program, although there is a large demand for such places.

- Kiwi Connection (KC): This is the English medium ‘mainstream’ program in the school. It comprises a diverse group of students, many of whom are bilingual in a wide range of other languages, even though the language of instruction is English. This program is growing rapidly, as the number of Māori and Pasifika bilingual children in the school’s zone decline. Because places on the roll in the school are restricted, due to the demand for bilingual programs, a number of children are enrolled in this rōpu by their parents in the hope that a place in one or other of the bilingual programs will become available. Approximately 20 percent of the KC students are passive or active bilinguals.

1.2 Historical background

The current organisational configuration of RRS has its origins in the school’s longstanding commitment to bilingual and multicultural education. Indeed, RRS was the first urban mainstream school in New Zealand to pursue multicultural and bilingual school program options simultaneously, beginning in the late 1970s (see May, 1993, 1994a, b, 1995). Over a period of nearly 20 years, under its visionary principal Jim Laughton (1972-1988), the school forged a theorised and pedagogically consistent model of critical multiculturalism (May, 1999), recognizing actively in school organization, policy and pedagogy, the importance of students’ home languages and cultures. This approach also included centrally within it the various bilingual program options previously outlined. Alongside this central focus on language and culture, the school also sought consistently to improve the educational achievement of its students, the majority of whom historically came from minority groups that had not fared well in education.

The educational philosophy and approach adopted by RRS under Laughton thus focused specifically on building a theorized, research-led ‘community of practice’ centred on bilingual and multicultural education—an approach developed well before the current emphases in New Zealand, or elsewhere, on such communities of practice (Lave & Wenger, 1991; Wenger 1998). Also central to the teaching and learning conducted in the school was the Māori concept of whānaungatanga, a metaphor for family relationships and reciprocity and inclusive of the largely Māori and Pasifika communities that the school served (cf. Bishop & Glynn, 1999).

For the teachers working together at Richmond Road during the time of Laughton’s innovations, the critical bilingual/multicultural approach adopted by the school also required a radical reconceptualisation of the teacher’s role. Principally, it involved developing a constructivist or participatory approach to pedagogy where teaching and learning were viewed as reciprocal and mutually constructed processes (May, 1994a).[2] A constructivist or participatory approach to learning meant letting go of previously held views about teacher knowledge and authority (Peters, 1973). It also involved considerable changes in school and classroom management and organisation, the pedagogy adopted, and the language(s) of instruction used.

As a result, RRS under Laughton became a place where the traditional structures of Pasifika and Māori learning were used to group children ‘vertically’ in multi-age, multi-level whānau or rōpu—again, the first mainstream New Zealand school to do so across the school as a whole—and where learning took place not necessarily within the conventional approaches of the balanced language program but in a series of independent, collaborative, cooperative or ‘superior/inferior communicative learning ‘arrangements’, shaped and supported by theme or topic based teacher made resources available at every reading access level (May, 1993, 1994a, b).

Such an approach also entailed a critical analysis of resource use, curriculum content and assessment methodology. It demanded an enormous investment of time, energy and the ‘lived’ commitment of the teachers. It compelled and challenged teachers to consider the school as a place where many languages and cultures could reside and be extended side by side, where first languages were an accepted part of the learning process, where bilingual classrooms were the norm and the teina/tuakana relationship (peer partnership based on age or expertise) was a prominent feature of pedagogy and practice (for an extended discussion, see May, 1994a’s critical ethnography of the school).

The innovation and educational effectiveness of RRS over this period subsequently gained wide international academic attention and recognition (see Cazden, 1989; May, 1993, 1994a, b, 1995; Corson, 2000). Indeed, Courtney Cazden, the prominent Harvard University educationalist, recently concluded that RRS, under Laughton’s principalship, was perhaps the most significant multicultural, multilingual primary school model in the world.

Richmond Road’s experiment over that period with variable spaces for learning, forms of grouping arrangements, extended age ranges, family groupings, parent spaces and facilities for pre-schoolers, tutor systems, off site language experiences, deployment and delegations of teachers and active community involvement was also advanced by Cazden (1989) and May (1994a) as a combined bilingual/multicultural strategy that could significantly enhance the subsequent academic achievement and wider life chances of Māori and Pasifika students in New Zealand. And yet ironically, given the ongoing concern about the relatively poor educational achievement of Māori and Pasifika students in mainstream New Zealand schools (Wilkinson, 1998; May, 2002a, b), the widespread national and international academic recognition of the efficacy of RRS’s approach with these students has not been replicated at the local policy level, the result perhaps of a continued (largely untheorised) reluctance by educational policy makers in New Zealand to promote bilingual education options in mainstream school contexts (May 2002b).

The hallmark of the RRS model becomes more visible in New Zealand, however, when analysed retrospectively through the more contemporary lens of Bishop (1996) and Bishop and Glynn (1999). Many of the principles these authors describe as critical to the success of Māori (and, by extension, other minority ethnic) students were already in place at RRS in the 1980s. RRS demonstrated, for example, Bishop and Glynn’s key assertion that a successful learning environment is one where learners can ‘bring who they are (and know that) … their knowledges, including languages are acceptable and legitimate’ and that ‘learning is active, problem based, integrated and holistic’ (1999: 13). Bishop and Glynn’s subsequent lengthy list—of which Laughton would have certainly approved—includes the following: learning is collaborative, roles may be exchanged, assessment must be culturally responsive, understandings must reflect the authentic experience of all learners, independence is the goal and critical reflection is an indispensable part of the examination of power relationships in teaching and learning.

Bishop and Glynn’s additional points underscore the commitment of RRS to the idea that ‘problem solving, critical thinking and creative analysis are seen as life long skills, teachers are inextricably linked to their students and community, and school/home parental aspirations are complementary’ (1999: 14). Once again, however, a key principle for success in Māori and multicultural education, and neglected perhaps in Bishop and Glynn’s own analysis, is leadership, for change, reform and continuity. Holdaway (Villers et al, 1984: 4) comments to this end: ‘Real educational reform is so especially difficult and unlikely that a model such as Richmond Road in the Laughton years is precious both locally and internationally as a statement of what is really possible.’

1.3 Contemporary school emphases

It is clear from the above historical sketch of RRS that a commitment to bilingualism was pivotal to the framework and the theorised view of teaching and learning that underpinned the school’s early innovative educational approach. This is a legacy of the Laughton years that has endured to the present day, as reflected in the school’s organisational structures. However, as we shall see, the continuance of this commitment to bilingualism was not necessarily guaranteed, nor necessarily as well informed in terms of theory and practice at all points since Laughton’s involvement in the school.

Since Laughton’s death in 1988, and without his inspirational leadership, RRS experienced retrenchment of the whole school bilingual focus at RRS throughout the 1990s (May, 1998) and into this current decade. This was exacerbated by an absence of clear strategic planning on how bilingual/multicultural aspirations might continue to be achieved at the school, and in light of increasing national policy pressure for English language priorities, most often, framed monolingually—as seen, for example, in the imperatives of the National Literacy Taskforce (Ministry of Education, 1999). Between 1994 and 2001, two successive new principals at RRS not familiar with, or committed to the school’s historical bilingual/multicultural rationale, took the school back to a more mainstream English medium position, putting the existing bilingual programs at serious risk.3

Increasing frustration with this more monolingual educational direction, however, led to the appointment in 2001 of a new principal, Hayley Read, who was committed to continuing the school’s bilingual education approach. Her leadership subsequently provided the impetus for four years of review and development within individual bilingual rōpu programs, which culminated in the development and involvement of the school in the 2006 TLRI pilot project, in conjunction with teacher educators from the University of Auckland.

The principal focus of the TLRI project was, first, to gauge the existing bilingual pedagogical content knowledge (PCK) of RRS teachers, in light of the long history of bilingual education programs at the school, and, second, via critical action research (CAR; see Section 3), to enhance/extend that bilingual PCK where possible.

The focus on improving RRS’s bilingual programs, via the TLRI project, was also deemed particularly pressing by the school because of a wider policy and pedagogical vacuum in relation to mainstream schools offering bilingual education (May, Hill & Tiakiwai, 2004; McCaffery & Tuafuti, 1998, 2003; Tuafuti and McCaffery, 2005). There are currently no effective national or regional Ministry of Education (MoE) policies, guidelines, preferred models and approaches, accepted pedagogies, assessment strategies, best practice strategy or practitioner research supports for bilingual education in these contexts. The TLRI pilot project was thus thought as useful not only for RRS itself but also, potentially, in providing a model that might be of use for other mainstream schools which offer bilingual education options.[3]

2. Research aims and objectives

It is within this wider context, that RRS pursued this practitioner-led TLRI pilot study in 2006. The research questions put forward in the initial research proposal (see Appendix A) focused primarily on the knowledge and beliefs that teachers had about bilingual education—their bilingual pedagogical content knowledge (PCK)—and the degree of match with recent research on bilingual education. However, at the start of the project, RRS teachers expressed a strong preference to begin instead with a focus on existing school policies, programs and practices. It was only after this initial focus that teachers felt confident enough to address directly their own bilingual PCK and, from that, the implications for modifying/changing existing bilingual policies, programs and practices in light of the wider research literature on bilingual education. Consequently, these initial research questions were recast in order to incorporate a more responsive and developmental research (and allied professional development) approach, a process that continued throughout the year. This is consonant with the generative and revisable processes involved in critical action research (CAR; see Carr & Kemmis, 1986; Kemmis & McTaggart, 1995; see also Section 3), the principal methodological framework employed in the pilot study.

This more fluid and responsive action research (AR) process does present challenges, however, particularly with respect to ensuring the overall trustworthiness and legitimacy of the research. To this end, the following quality criteria, focused primarily on qualitative research processes, were employed throughout the research to ensure that the AR undertaken did yield trustworthy and valid outcomes (for further discussion of these criteria, see Carr & Kemmis, 1986; Kincheloe, 2003; Kemmis & McTaggart, 2000, 2005):

- The collection and analysis of a variety of data from a range of sources and perspectives;

- The interlinking of reflection and action through a cyclical approach;

- A recognition that AR is inevitably a subjective /value laden approach which is not concerned with the search for objectivity;

- A recognition that the process of AR is not necessarily about finding solutions so much as deepening understanding and identifying areas for further research development;

- AR is concerned with the development of professional competence and collaboration, and peer evaluation should be used as part of the process of critical reflection;

- The interactive dissemination of findings for critical scrutiny and professional debate is essential.

As Carr and Kemmis argue, these AR criteria empower teacher practitioners to take control of the development and direction of change themselves through processes that are more important than immediate short-term outcomes:

Action research recognises that thought and action arise from practices in particular situations, and that situations themselves can be transformed by transforming the practices that constitute them and the understandings that make them meaningful. (1986: 185)

Following from these general AR quality categories, specific effectiveness criteria were also developed during the course of the pilot study. These were framed as follows:

How well did the research:

- leave the teacher practitioners feeling more professionally empowered to understand, challenge, reflect on, evaluate and act to control their own practice;

- promote a critical reflective examination of their own, the school, and the wider education community’s current policies, practices, knowledge, understandings, theories, beliefs and values of bilingual education;

- promote a critical collaborative community of practice (CoP) with high levels of engagement;

- foster sharing with peers in critical discussion, review and debate;

- employ multiple data sources to cross check emerging findings;

- identify key areas for further research?

2.1 Key research questions

The key research questions that emerged, and guided the wider AR research process, over the course of the year, can be summarised as followed:

- What are the existing bilingual pedagogies and practices of RRS and how effective are they?

- What levels of bilingual PCK do RRS teachers demonstrate in relation to these existing bilingual pedagogies and practices at the school?

- How can critical action research (CAR) extend RRS teachers’ bilingual PCK in line with best practices identified in the relevant research literature?

- How might this CAR process provide the basis for changing/modifying/improving teaching practices at the school, within the limits of a one-year pilot study?

The emergent research focus on the role and significance of teachers’ bilingual PCK to the ongoing bilingual pedagogy and practice of RRS was a key feature of this pilot study. Developing further the bilingual PCK of teachers, and linking this directly to their educational practice via critical action research, also came to be seen as a key aspect of the research process over the course of the year.

2.2 Practitioner/researcher partnerships

A hallmark of RRS historically had been its school-initiated, research-based, approach to bilingual education and its partnerships over the years with key educational researchers (see Section 1). The TLRI pilot study was an attempt to revisit this educational model, via a collaborative research partnership with teacher educators from the University of Auckland (UoA). As outlined above, it was hoped that RRS teachers would engage in the research in order to critically reconceptualize, examine and theorize their own individual practice in relation to bilingual education, as well as (re-)develop a critical community of practice within the school, again a key feature of the school historically.

Accordingly, research partnerships were established with various stakeholders as a basis for proceeding collaboratively with the research. Key stakeholders included:

- Teacher practitioner team—all RRS staff

- Teacher educator/research team—selected researchers at the University of Auckland

- Advisory Group—including an External Research Advisor, Board of Trustee Members, Community Elders, and Critical Friends

Where this research partnership model differed from other teacher/researcher collaborations was in the locus of control for the study. A research advisory committee, comprising joint representatives from both RRS and the UoA educational research team, was established to oversee the pilot study and was jointly chaired by Hayley Read, RRS Principal at the time, and the lead UoA liaison researcher, John McCaffery. However, the research project remained located, controlled, budgeted and managed from within the school itself. The function of the research team was thus to advise and assist RRS teachers in the undertaking of the research, not to lead the research. Researchers suggested how the research should develop/progress over the course of the year but, in the end, the school made the final decisions about research priorities, focus, issues and topics to be investigated in the pilot study.

This practitioner-led approach to the research did create some tensions. RRS teachers, as expected, demonstrated varying levels of readiness and engagement with respect to the research processes undertaken, both initially and throughout the course of the pilot study. The research focus on bilingual PCK was initially delayed by a teacher-led focus on existing programs and practices, as already discussed. Throughout the year, the distinction between research-based action research and professional development was also not always easy to maintain (see Section 6).

Nonetheless, the tensions that emerged in the research process were, themselves, an important finding in relation to how well such a practitioner-led research partnership could operate. Moreover, in spite of a growing rhetoric about the importance of researcher practitioner partnerships of this kind (Kincheloe, 2003), this remains one of the few attempts we are aware of in the New Zealand context that has sought to operate in this way (Robinson & Lai, 2006).

2.3 Research ethics

The Māori Research Guidelines (Bishop, 1996, 2005; Cram, 2001; L.T. Smith, 1999, 2005) and the National Pasifika Education Research Guidelines (Anae et al., 2001; Coxon et al., 2002) provided the ethical framework for this research.

The pilot study drew directly on the work of G. H. Smith (1997), Cram (2001) and L.T Smith (1999, 2005) with respect to the ethical requirements of working in Māori contexts. These characteristics were summarised in the following way for the purposes of the research:

| • G.H. Smith (1997) | • Cram (2001) | • L.T. Smith (1999, 2005) |

|---|---|---|

| • Tino rangatiratanga

Māori researchers will decide what is significant to Māori and make decisions based on a Māori framework. |

• A respect for people

He aha te mea nui i te ao / he tangata, he tangata. People and relationships are what is important. |

• Kaupapa Māori philosophies and methodologies must provide frameworks for guiding research. |

| • Taonga tuku iho

Cultural aspirations. The right to live in the world and act in research as Māori. |

• He kanohi kitea

Person to person / face to face. |

• Kaupapa Māori methodologies must provide frameworks for research design. |

| • Ako Māori

Culturally preferred pedagogy and ways of promoting teaching and learning. |

• Titiro, whakarongo… korero

Watch / engage / listen / experience / only then talk |

• Kaupapa Māori frameworks must set the ground rules for the way research is conducted. Process is as important as the product. |

| • Ka pïkiake i nga raruraru o te kainga

All must seek the socioeconomic and educational improvement of Māori. |

• Manaaki ki te tangata

Show care concern and respect for all people. |

• Kaupapa Māori must frame the interpretation of data and findings. |

| • Whānau

Act as if all in the research are related, as in whānau, with reciprocal obligations and aroha. Collective responsibility and preference for group processes. |

• Kia tupato

Proceed with caution. Do not rush in. • Kaua e mahaki Remember to be humble and not full of self importance about your status. |

• Kaupapa Māori frameworks must critically interrogate other research methodologies and frameworks for inconsistencies with Māori research and also what they have to offer by being co-opted and adapted. |

| • Kaupapa

Collectively shared Māori philosophy and theories about knowledge education and learning. |

• Kaua e takahia te mana o te tangata

Take care not to trample on the mana of people. |

• Where possible, Māori issues should be researched by Māori. Non Māori working in Māori research areas must have guidance from, and work in partnerships and association with, Māori. |

The pilot study also adhered to the ethical guidelines developed by Anae et al. (2001), Coxon, et al. (2002) and the Health Research Council of New Zealand (2004) in relation to Pasifika research. This involved developing/acknowledging:

- A non-exploitative research process environment;

- Purposes goals and visions for Pasifika education derived from Pasifika communities themselves;

- Pasifika values, beliefs, languages and knowledge systems;

- An empowering process and empowering outcomes for all involved;

- Genuine partnerships between all parties involved;

- Capacity building;

- Research methods that were:

-

- Sensitive to contemporary Pacific contexts

- Embracing of collective ownership

- Responding to emerging Pacific research methodology development

- Effective and culturally appropriate for Pasifika practitioners.

In addition, key elders/kaumātua from both the Māori and Pasifika school communities, as well as parents from all sectors of the school, were regularly consulted, over substantial periods of time, in relation to research processes and potential outcomes.

Ethical considerations applied equally to the teacher practitioners and the teacher educator team from the University of Auckland. The University of Auckland’s Ethics Committee formally approved the research, while approval for the work was also sought from, and granted by the TLRI, the school Board of Trustees, and each participant involved in the research.

In such a small scale, open, whole school action research project on a single site, it is not possible to preserve completely the anonymity of the participants or the confidentiality of all data. Moreover, the school is readily identifiable by its educational approach and school organisation and structure (see Section 1). Consequently, in the writing up process, the authors and the staff agreed with the principal’s suggestion that the school should be named, and so the lack of anonymity became a reasonable and ethical choice in the circumstances. The group also agreed to permit the identification of staff who wished to be named in the reports although, wherever possible, the anonymity of individuals has been maintained. The data gathered as a result of the project were also treated as confidential to those within the UoA research team. Data from within the project were not discussed in the hearing of students, parents or others not subject to the project’s ethical agreement processes.

Despite these safeguards, it soon became apparent that understanding and acceptance of the difference between school and research ‘business’ and ethics was, for those involved in the research, hard to maintain at times (see also Section 6). It would appear that there is an inherent and unresolvable tension that has to be acknowledged and managed in this regard, with systems needing to be put in place to ameliorate any potential conflicts of interest. Checking against the research questions was a useful strategy here, followed by group discussion, in attempting to differentiate between school and research business. That is: ‘Is this issue, discussion, or discourse essential to answering the research question/s?’ If so, it is research business. ‘Is it also essential to school operation?’ If so, it is also school business and the issue needs further discussion on how to manage it in a particular situation. This checking process was used throughout the year to ameliorate this particular issue when it arose.

3. Research design and methodology

Critical action research (CAR) was the overarching research design that framed this TLRI pilot study. Within this broad research framework, a mixed methods approach was employed in relation to exploring each of the research questions identified in Section 2 (see also 3.4 for further discussion). Multiple ways of generating, gathering, interpreting and reporting data within this overall CAR framework were thus used, providing they did not conflict with the wider aims and objectives of the research. It would not be acceptable in CAR, for example, for researchers to design a study where data were to be gathered and interpreted without referring it back to participants for their comment and interpretation. Nor would it be acceptable in CAR to design and impose data gathering and interpretation methods or approaches that excluded teacher practitioners from fully taking part, understanding and engaging in the research work undertaken and the subsequent interpretation of the outcomes (see, e.g., Kemmis & McTaggart, 2005; Kincheloe & Berry, 2004). We sought therefore to use and mentor teacher practitioners in ways that facilitated them learning about and learning to use action research methods and strategies for themselves within the timeframe set for the project.

3.1 Action research

Action research, as a broad qualitative research methodology, is a well-attested approach that involves teacher practitioners directly in educational research work within schools (see, e.g., Carr & Kemmis, 1986; Kemmis & McTaggart, 2000, 2005; Kincheloe, 2003). Action research (AR) can thus usefully be seen as a subset of practitioner research, and teacher research, with strong connections to action learning and reflective practice (Schon, 1983).

A key feature of AR to this end is the use of reflective cycles of examination, planning, action, reflection, action, evaluation, and the resetting of goals in light of these cycles (Carr & Kemmis, 1986; Kemmis & McTaggart, 2005; Kraft, 2002). Action research then, is less about action cycles and more about collaborative reflective cycles in action. This personal and group enactment of reflective practice is reported in a wide range of studies as having greatly improved outcomes for learners (Carr & Kemmis, 1986, p. 165; Kemmis & McTaggart, 2000, 2005; McNiff & Whitehead, 2002). Reflective practice can also be integrated into a full range of research methods for generating and collecting data. These include data generation and collection methods of observation, video and audio recordings, ethnography, field notes, case study, interviews, focus groups, questionnaires, surveys, narratives, life history, work shadowing, sampling, reflective discussions, and reflective writing (Cooke & Cox, 2005; Reason & Bradbury, 2001).

Carr and Kemmis summarise the purposes of action research thus:

There are two essential aims of all action research: to improve and to involve. Action research aims at improvement in three areas: firstly, the improvement of a practice; secondly, the improvement of the understanding of the practice by its practitioners; and thirdly, the improvement of the situation in which the practice takes place. The aim of involvement stands shoulder to shoulder with the aim of improvement. Those involved in the practice being considered are to be involved in the action research process in all its phases of planning, acting, observing, and reflecting. As an action research project develops, it is expected that a widening circle of those affected by the practice will become involved in the research process. (1986: 165)

Similarly, Johnstone argues:

Action research is characterized as systematic inquiry that is collective, collaborative, selfreflective, critical, and undertaken by [all] the participants of the inquiry. The goals of such research are the understanding of practice and the articulation of a rationale or philosophy of practice in order to improve that practice. (1994: 41)

3.2 Key aspects of Critical Action Research (CAR)

Critical action research (CAR) accords with these general features of AR, but is also characterised, more specifically, by the following key principles:

- ‘Critically theorised’, ‘emancipatory’, ‘critically reflective’ and ‘transformative’: situated within a critical theoretical and pedagogical orientation (Carr & Kemmis, 1986; Kemmis & McTaggart, 2005; Corson, 2000)

- Diagnostic: begins from the reality of current and actual teacher practice (Kincheloe, 2003; Kincheloe & Berry, 2004)

- Problem or issue focused: is derived from the practitioners themselves (Kincheloe, 2003; May, 1994a)

- Situational: is based on the specific context of the school during a specific period of time. (Lave & Wenger, 1991; May, 1994a)

- Collaborative and non hierarchical: researchers and practitioners as equal partners (Kemmis & McTaggart, 2005)

- Participatory: supportive and scaffolded so all are able to play a full and confident part in the project (Kemmis & McTaggart, 2005)

- Cyclical: cycles of development using a ‘plan, act, review, critically reflect and modify’ approach and carrying this into the next action cycle (Carr & Kemmis, 1986)

- Cooperative: including and involving all members where possible (Allen & Miller, 1990)

- Culturally inclusive: providing opportunity to have one’s cultural and linguistic background recognised and included in the research process (Cummins, 2001; Tuafuti & McCaffery, 2005)

- Self–Reflective: critical reflective practice is the basis for all action (Kraft, 2002; Lather, 1986, 1992)

- Self-Evaluative: evaluation carried out by the participants themselves, rather than independent outside researchers (Kemmis & McTaggart, 2005; Kincheloe, 2003; Kincheloe & Berry, 2004)

- Emancipatory: awareness of the way power and knowledge are constructed and the use of critical reflection to prioritise, drive and sustain new visions for change (Kemmis & McTaggart, 2005)

- Sustainable: seeks to replace traditional professional development with sustainable action research driven professional development (Guskey, 1999, 2000; Kincheloe, 2003; Kincheloe & Berry, 2004)

- Dissemination of results: remains an essential characteristic of research activity and essential to CAR goals (Kemmis & McTaggart, 2005; Kincheloe, 2003; Kincheloe & Berry, 2004).

3.3 Key uses of CAR in the study

It is these CAR principles that framed the methodological approach of this TLRI pilot study at Richmond Road School. In particular, it was hoped that the CAR research process undertaken by the school would achieve the following:

- Increase the depth of individual practitioners’ understanding about bilingual education and related bilingual pedagogical content knowledge (PCK);

- (Re-)establish a critical community of practice at the school in relation to bilingual education pedagogy and practice;

- Improve existing school practices in bilingual education.

More generally, it was hope that the pilot study would:

- Promote the development of a network of research relationships, and the related value of teacher education and teacher practitioner partnerships, in conducting school-based research

- Increase the quality and trustworthiness of practitioner research via these research partnerships;

- Assist practitioners via these partnerships to build their own action research capacity and theoretical understandings through praxis.

3.4 CAR methodologies employed

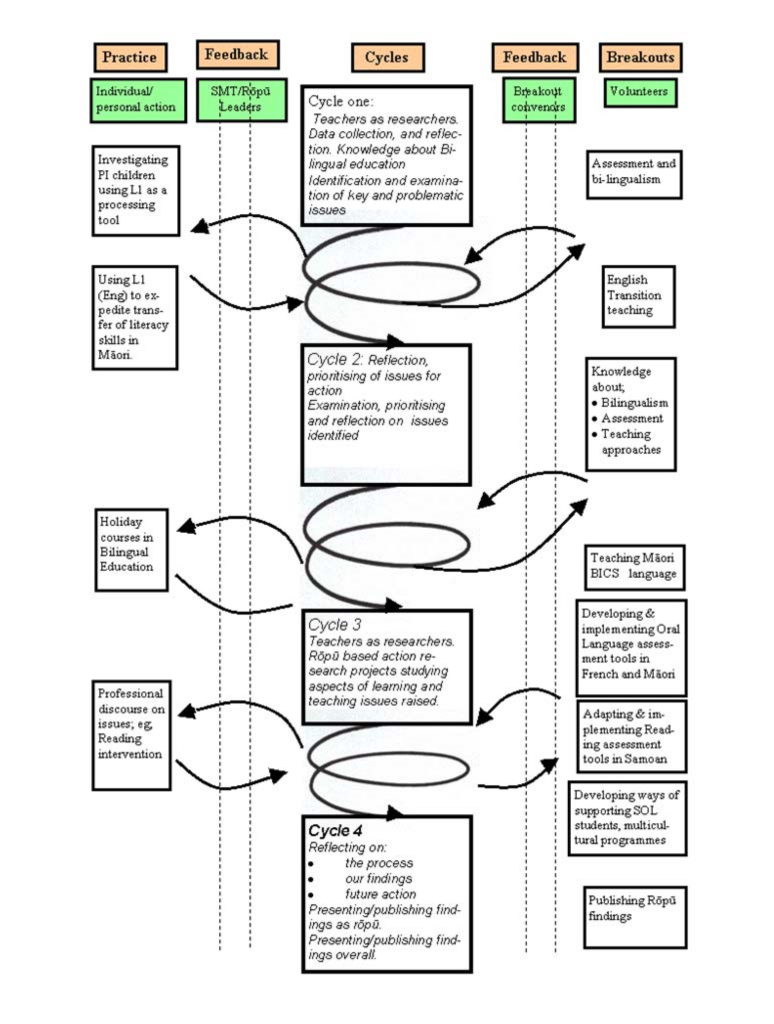

A key feature of AR is the iterative action research cycle, which also formed a central part of the TRLI project reported on here (see Figure 1 below). Four AR cycles were completed over the course of the year and their specifics will be discussed in the following section. Before doing so, however, it is important to highlight the CAR methodologies that were employed throughout all the AR reflective cycles.

In line with its wider objectives, the project adopted an inductive (Burns, 1999) rather than a deductive approach (Mills 2003) to critical action research in each research cycle. As Burns (1999) outlines, this inductive model uses the following interrelated activities in the AR process:

- Explore an issue in policy teaching or learning;

- Identify areas of concern; y Observe or examine how these areas are currently operating;

- Explore/discuss/reflect on how the issue might be addressed;

- Collect data to determine the possible action/s to be taken—from more than one source if possible;

- Plan strategic actions based on the data to address the issue; y Carry out action plan, reflect, and draw conclusions.

Within this inductive AR approach, the following research methods were specifically employed:

- Participant observation with field notes (UoA research team); y Reflective e-diaries (all participants);

- Focus groups (small group; rōpu-based), with structured tasks—for example, cooperatively developing an agreed written position on bilingual education (RRS teacher practitioners);

- Interviews (including video interviews) with teacher practitioners; y Reflective discussions with the research advisory group and critical friends.

The nature of these research activities addressed the wider critical and participatory aims of the research project:

- To learn (by doing) about being a practitioner CAR researcher in Māori and Pasifika research settings;

- To develop greater PCK about bilingual education among teacher practitioners;

- To provide a structured framework within which to generate, gather, record, share and reflect on AR processes and data in relation to the project

- To plan and organize AR reflective cycles and associated research tasks in light of the above (see 3.5 for further discussion).

These mixed/multiple research methods are also consonant with usual AR methodological research practices. Participant observations, supplemented by field notes, in school-based settings are standard qualitative research practice, including critically oriented research (see, e.g. May, 1997). Reflective e-diaries were chosen, rather than the more usual and extended reflective journals, as a means of ensuring/enhancing teacher buy-in in relation to the reflective processes required of AR. As Shacklock and Smyth (1998) observe, while more in-depth reflective journals are highly effective, they depend on practitioners’ willingness to participate in regular in-depth writing. However, Shacklock and Smyth, together with Sa (2002), argue that the use of diaries still has the potential to promote these reflective higher and deeper higher levels of thinking, but with greater practitioner ‘buy in’ from sometimes-reluctant practitioners who want ‘action’. The latter characteristic was also evident in this particular project, particularly in Cycle 1 (see 3.5; cf. Knight, Wiseman, & Smith, 1992).

In this research, pre-prepared written formats and a laptop e-diary template were used so that entries could be made at any time in the research workshops established as part of the wider AR reflective cycle process. However, RRS teachers were asked only to make entries in their e-diaries on what they saw as problematic and challenging issues as these arose from this process (Tripp, 1998). Teachers were also encouraged to share their reflections and discuss what individual reflections meant for them and their programs in research workshops. Print outs and hard copies of these teacher reflections were regularly collected and content sorted/grouped for major themes and responses as part of the ongoing AR process, with these emergent themes then reflected back to the next workshop for further discussion and analysis.

In addition to whole school research workshops, research focus groups (Kvale, 1996) that were rōpu based were also established as part of the AR reflective cycle process and met at least once every three weeks throughout the year. Focus group activities were structured by specific research tasks. For example, in Cycle 1, rōpu were required to develop an agreed written position on the rationale for their particular approach to bilingual education, linking this position specifically to the theories of bilingual education examined. It was expected that this collaborative research task would highlight the links (and potential discontinuities) between current pedagogy and practice and the wider research literature on bilingual education.

Interviews with teacher practitioners (Kvale, 1996), including video interviews, were also conducted throughout the research. Video interviews in Cycle 1, aimed at exploring the bilingual PCK of individual teachers, had to be abandoned, however, because of the difficulties teachers experienced in articulating their understandings at this early stage (see 3.5). Exit video interviews were also conducted at the end of the pilot study, although because of time and funding constraints these were only analysed after the formal completion of the research.

3.5 The AR reflective cycles

The iterative action research cycles undertaken throughout the course of the TLRI project can be summarised as summarised as follows:

Figure 1 Reflective cycles of the CAR process at RRS

3.5.1 AR Cycle 1 (February-March 2006)

Key research questions addressed:

- What are the existing bilingual pedagogies and practices of RRS and how effective are they?

- What levels of bilingual PCK do RRS teachers demonstrate in relation to these existing bilingual pedagogies and practices at the school?

In AR Cycle 1, voluntary 90-minute research focused workshops, facilitated by members of the UoA research team, were established and met weekly over this period. The initial expectation was that up to 10 teachers from the bilingual rōpu within the school would be involved in these research workshops. However, all RRS staff, including staff in the mainstream English ‘Kiwi Connection’ rōpu, chose to participate, making them, in effect, whole school workshops.

Given the unexpected involvement of the whole staff in the research project, the initial research discussions in these workshops focused on the following:

- Collaboratively negotiating and agreeing the CAR processes of the pilot study and related participation of RRS staff (a process that remained ongoing throughout the year);

- Collaboratively negotiating the research focus for this first cycle.

With respect to the latter, it had been initially anticipated that a major focus of this initial cycle would be on ascertaining the existing bilingual PCK of RRS staff in relation to two key sets of research literature; that associated directly with the historical practices of the school itself (see Section 1) and more recent general literature on research-based best practices in bilingual education (see, for example, May et al., 2004). A literature review incorporating both these sets of literature had been completed early in Cycle 1 as a basis for further research discussion with teachers. However, the teacher practitioners’ concern to begin with an examination of existing school practices resulted in the deferral of this anticipated focus on teachers’ bilingual PCK (see below).

In these Cycle 1 workshops, considerable general discussion and debate took place around the nature of action research and the differences between AR and professional development (PD).

The initial AR cycle, in line with stated teacher practitioner preferences, also provided the opportunity for participants to raise and explore key issues about bilingualism and learning at RRS, particularly the way individual rōpu groups, as well as the school as a whole, were addressing these issues in their pedagogy and practice.

Given this teacher-led emphasis on existing pedagogies practices, it was only towards the end of the first cycle that the AR processes turned to the examination of individual teachers’ own bilingual PCK. At this point, individual video interviews with teachers were conducted, aimed at exploring the articulation of their bilingual PCK, although these interviews were also subsequently abandoned when teachers were unable to satisfactorily complete this task (see Section 4.1).

While these developments were unexpected, the reshaping of preset research questions and related tasks, the development of alternatives, and even their abandonment, are accepted research practice in critical action research such as this. As Blyer (1998, p. 37) argues:

[In CAR] …the researcher is no longer dominant and in control-no longer the “sole arbiter of what counts as knowledge”…. Instead, knowledge is “generated via a dialectic” between researcher and participants … where the participants—not the researcher—arrive at research questions that matter to them and search for answers they require.

3.5.2 AR Cycle 2 (April-June 2006)

Key research questions addressed:

- What levels of bilingual PCK do RRS teachers demonstrate in relation to these existing bilingual pedagogies and practices at the school?

- How can critical action research (CAR) extend RRS teachers’ bilingual PCK in line with best practices identified in the relevant research literature?

The research methods established in Cycle 1 were continued through Cycle 2 of the AR process as RRS teachers began to address more directly the need to extend their bilingual pedagogical content knowledge (PCK) in light of the issues raised in Cycle 1. In particular, first level data from the AR methods employed in Cycle 1, including the areas of existing pedagogy and practice identified for further research, were reflected back to practitioners in this subsequent cycle, and their reflections and interpretations of these first order data were then used to generate further data (Kemmis & McTaggart, 2000, 2005).

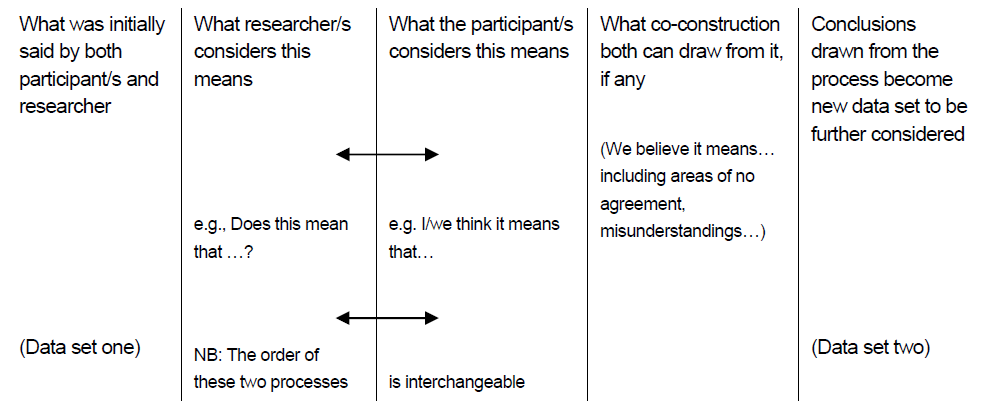

This process is consonant with critical action research (CAR), where each level of reflective discussion about the previous interpretations provides another data set for further reflection of more significance than the earlier data set (Lather, 1992). First order diaries or journals in CAR, for example, were followed by interviews and discussion, about what the data in the writing meant to participants. The reflective links were then made and matches and mismatches between the data and interpretations examined as a basis for further discussion. Only these higher order data sets were used subsequently to draw conclusions about the research. As Kincheloe and Berry argue, critical action research projects need to be seen as ‘actively and ongoingly constructed’ (2004: 2-3) in this way in order to ensure/enhance their validity.

The following diagram illustrates the iterative CAR processes of data generation developed in this cycle and throughout the TLRI project:

Table 2 Reflective data schedule

On this basis, Cycle 2 involved participants in a more detailed examination and exploration of the interconnections between the school’s existing practices in relation to bilingual education and teachers’ own bilingual PCK about these practices in relation to the relevant research literature on bilingual education. The increasing focus on teachers’ bilingual PCK was also a product of the difficulties involved for many teachers in articulating their beliefs, and the relationship to relevant theory, in the first cycle. Towards the end of this second cycle there were a raft of new questions generated for investigation. These were prioritised as a basis for further investigation and follow up work and then subsequently used as the basis for Cycle 3 rōpu-based AR activities (see below).

AR processes were thus used for reflecting on processes and outcomes, developing new interpretations, linking to theoretical positions, looking for possible answers, and taking ideas back to the classroom for further trial and examination. This process is very similar to that used by Robinson and Lai (2006. pp 15-34) in their ‘Theories of Action” work in Manukau schools.

3.5.3 Cycle 3 (July-September 2006) and Cycle 4 (October-December 2006)

Key research questions addressed:

- How can critical action research (CAR) extend RRS teachers’ bilingual PCK in line with best practices identified in the relevant research literature?

- How might this CAR process provide the basis for changing/modifying/improving teaching practices at the school, within the limits of a one-year pilot study?

In Cycles 3 and 4, the locus shifted to the rōpu level as each rōpu developed an AR investigation of their teaching practice in light of the data and conclusions generated in the preceding cycles.

In particular, each of the four rōpu (including the English-medium ‘Kiwi Connection’) selected an aspect or aspects from the priority issues agreed at the end of Cycle 2 in order to pilot ways of further researching their own classroom practice.

Specifically, each rōpu undertook preliminary scoping work to overview the issue they had identified and to develop appropriate AR questions in light of that. They then drew up and submitted a detailed written AR research proposal in order to obtain teacher release days to investigate and carry out the research. This was discussed with the UoA research team members and further developed in light of their feedback. Proposals went back and forth until approved.

Each rōpu then investigated the issue they had identified. Baseline data were gathered on their and their students’ current situation in relation to the identified research question. Possible solutions were explored in light of the AR processes undertaken to date, as well as additional research information being drawn upon where needed. The action plan was revised accordingly and then implemented. Ongoing results were monitored and explored at weekly meetings and on release days throughout this cycle.

It was anticipated that by the start of Cycle 4 these AR projects would be complete and that each rōpu would subsequently provide oral and written summary reports in this final cycle to all participants on the particular AR project undertaken. However, all AR projects continued into Cycle 4, thus delimiting the opportunity to provide detailed summaries of the projects to the wider group within the remaining timeframe for the research project.

Video exit interviews (Kvale, 1996) were also conducted in this final cycle with teacher practitioners, with 18 out of the 20 teachers involved participating. The focus of the interviews was on how the CAR processes undertaken throughout the course of the year had extended individual teachers’ bilingual PCK, as well as influencing/changing teacher practices, both individually and collectively, within the school. However, time and budgeting constraints meant that these interviews could not subsequently be transcribed or analysed within the remaining time period for the research.

Given these constraints, and in order to provide a summative analysis of the overall project, the lead researcher subsequently analysed the rōpu action research projects, along with the video exit interviews, in 2007.

4. Key findings/outcomes of the research

Hindsight is always deceptive as you have the benefit of the learning you didn’t have at the time. We shouldn’t be wringing our hands about what we didn’t do. We need to celebrate what we did do well and how it set us up for where we go next. (Teacher practitioner, WW, 11 December 2006)

4.1 Cycle 1: Assessing initial bilingual PCK among teachers at RRS

Research questions addressed:

- What are the existing bilingual pedagogies and practices of RRS and how effective are they?

- What levels of bilingual pedagogical content knowledge (PCK) do RRS teachers demonstrate in relation to their bilingual education practice at the school?

The initial aim of Cycle 1 of the critical action research (CAR) process had been to explore and discuss the existing bilingual PCK of RRS staff—that is, their knowledge of best practices in bilingual education and teaching bilingual students—with the allied assumption that teachers would be able to outline, situate and explain their teaching and learning practices in ways that were broadly congruent with the wider research literature on bilingual education.

Both these dimensions were deemed important because of the significance of PCK to effective teaching practice. Shulman (1987), who first introduced the notion of PCK, has argued that it is a unique but essential part of teachers’ knowledge for effective instruction. PCK requires that teachers possess not only deep understanding of the structure and content of a particular discipline, or in this case a broader educational approach, but that they also have the ability to represent content flexibly to students with varying conceptions and development. It includes teacher preconceptions and beliefs about students and their learning. This also calls for teachers to have knowledge of (1) students’ abilities, common learning difficulties, attitudes, motivations, teaching and learning techniques, developmental levels, and prior knowledge, and (2) the social, political, cultural and physical environments within which students are situated. Shulman’s theoretical framework suggests that the integrated nature of PCK continues to grow as teachers increasingly gain teaching experience. As Shulman concludes:

The key to distinguishing the knowledge base of teaching lies at the intersection of content and pedagogy, in the capacity of a teacher to transform the content knowledge he or she possesses into forms that are pedagogically powerful and yet adaptive to the variations in ability and background presented by the students. (1987: 15)

The findings in this initial cycle, however, highlighted a significantly different story. Rather than starting with the wider research literature and examining this in relation to teacher practitioners’ individual bilingual PCK, teacher practitioners at RRS preferred to focus instead on existing bilingual practices within the school. These discussions centred, in particular, on the following key areas of school pedagogy and practice: the development of assessments in languages other than English (all assessments to that point had been in English); appropriate levelling for bilingual students, particularly in relation to the majority of heritage (2nd) language learners in the bilingual programs; separation of instruction versus code-switching in bilingual classrooms; the monitoring of vocabulary; the integration of language and curriculum content. While such discussion was clearly significant for the teacher practitioners, little attempt was made by them at this early stage to link such practices to relevant research literature or to explore such practices in relation to their own PCK.

The focus did turn towards bilingual PCK towards the end of this first cycle, however, once teacher practitioners had begun to realise that their practices needed further exploration in relation to relevant research literature. Even so, teachers still clearly struggled to make the necessary conceptual links. For example, teachers from each rōpu were set a research task that involved them worked cooperatively for one research session to see if they could set out their current beliefs explicitly in writing. At the end of that session they reported back to the wider group. Results were very mixed. Even those who were acknowledged as being very successful at teaching bilingually found this a very challenging task. Similarly, when teachers were interviewed about their rōpu’s current pedagogy and practice, they had considerable difficulty in articulating a clear rationale beyond that of historical or customary practice(s). These interviews, which were videoed, were subsequently discontinued when it became apparent that the teacher practitioners were clearly struggling to articulate the necessary level of bilingual PCK at this early stage of the research to satisfactorily complete this task.[4]

In addition, it became evident in Cycle 1 that individual rōpu had little knowledge of the bilingual education approaches adopted in other rōpu or an overarching view of bilingual practices within the school. The English-medium (Kiwi Connection) rōpu, in particular, had difficulty situating its pedagogy in relation to wider bilingual practices. Moreover, stated beliefs by teachers about bilingual practices in this initial cycle were often directly contrary to best evidence research. By way of example of the latter, each of the following statements made by individual teachers in Cycle 1, contradicts a key research-based bilingual education principle or practice that is outlined subsequently within square brackets (see May et al., 2004 for a useful overview:

- Bilingualism is not an issue for our children in Kiwi Connection English medium [while the approach in Kiwi Connection is English-medium, there remain many students within the rōpu who are bilingual, or exhibit varying degrees of bilingualism. Bilingual PCK is necessary if these students are to be taught well; see May, et al., 2004]

- Bilingualism means to be equally capable if both languages at all stages and phases of development [such ‘balanced bilingualism’ is actually rare—bilinguals normally exhibit a continuum of bilingualism and biliteracy, depending on the educational and/or wider social context; Baker, 2006]

- The more time spent in learning English the better children will be at it [quite the contrary: bilingual students will best learn English if they are allowed to become literate in their first language; see Cummins, 2000; Thomas and Collier, 2002; May et al., 2004; Baker, 2006; Baker & Prys-Jones, 1998]

- Getting them started on English literacy should be a prime goal of Year 1 programs [see previous comment]

- The success of the programs can be measured by assessment of outcomes in English at each stage of the program [testing only in English does not allow for the accurate measurement of bilingualism or biliteracy among students, nor does it recognise the relationship between bilingual learning and the acquisition of English; see Cummins, 2000; Corson, 2000; May et al., 2004)

In short, and contrary to initial assumptions, Cycle 1 of the CAR process highlighted a low level of bilingual PCK among RRS staff. That said, the demonstrable difficulties encountered by teachers in relation to the research tasks and video interviews, did serve as a useful catalyst for turning to a more direct focus on teachers’ bilingual PCK in the following cycle.

4.2 Cycle 2: Building a bilingual community of practice (CoP) at RRS

Research question addressed:

- How can critical action research (CAR) extend RRS teachers’ bilingual PCK in line with best practices identified in the relevant research literature?

- How might this CAR process provide the basis for changing/modifying/improving teaching practices at the school, within the limits of a one-year pilot study?

As a result of the findings from Cycle 1, Cycle 2 focused on extending the individual bilingual PCK of RRS teachers as well as (re-) building a wider, cohesive community of practice (CoP) in relation to bilingualism and bilingual education—a key feature historically of RRS (see Section 1). Wenger (1998) and his colleague Jean Lave (Lave & Wenger, 1991) identify a CoP as a central strategy in understanding, and subsequently reforming, learning and teaching in schools.

Such reform seeks to recognize and value the social and cultural contexts and influences on learning and argues for reflection about and, if necessary subsequent rethinking of, current institutional conceptions of teaching and learning.

The CAR activities undertaken in Cycle 2 continued to address in an iterative manner the issues that had emerged in Cycle 1. In particular, an overarching research question that emerged in Cycle 2 was how to promote additive, as opposed to subtractive, bilingual contexts within each rōpu and across the school. The additive/subtractive distinction is a key one in the research literature—the former associated with achieving bilingualism, biliteracy and academic success for bilingual students the latter with delimiting these (see May et al., 2004; Baker, 2006 for further discussion). This increasing focus on the conditions necessary for achieving additive bilingualism saw teachers shift from an initial isolated, disjointed and largely untheorised position on their bilingual practices, evident in Cycle 1, to an emerging CoP based explicitly on fostering additive bilingual teaching and learning environments. As one teacher practitioner observed of this development at the end of the year, when reflecting back on the wider research process:

It brought the whole school together in one dialogue, one [research] conversation. It brought the issues to the table in a common dialogue. [It gave] us parameters, headings and labels to [be able to] talk about the same contexts [as well as] references to refer to … (11 December, 2006)

This growing sense of ownership—a key feature of CoP—was also encapsulated by the following reflection about the role of Kiwi Connection teachers in the research, who after some initial reticence about the relevance of the research project to their own practices had, by Cycle 2, begun to realize that this CoP was also important for them:

We began to look at whether our mainstream environment was additive or subtractive it. Initially we assumed that our environment was additive, but upon closer examination we realised that we could do SO much more for these children. In March 2006, the School Council put on a ‘culture day’, whereby children were encouraged to come to school dressed in a cultural outfit. One Samoan boy … came to school in a lavalava, and [his teacher] said later on that she’d never seen him look so relaxed and so well behaved. This scenario resurfaced after we had learned about additive and subtractive teaching, and provided us with the ‘aha!’ moment. From then on the ideas began to roll. [Another teacher] decided to actively encourage the two Portuguese speakers in her class to translate their written work into their home language. Furthermore, she encouraged them to speak to each other in their home language and asked them a lot of questions about their backgrounds and life in Brazil. Of course this extended to the other children in her class, who began to talk about their home language and culture and share it with others. Similarly, in my class (seniors) we began to use the topic of ‘immigration’ as a vehicle to find out about other children’s cultures and backgrounds. My Niuean students taught other students hand clapping games, and bits and pieces of the language. Two Tongan boys, one an underachiever, began to work together, the more able assisting the less able. This was something that came out of their own sense of belonging. It was not directly requested by me. In the other classes, the discussions and learning took place in a similar, informal discourse. Children talked about their culture, their family, food, dances and languages, and this was shared. We began to feel much more comfortable with the project… (Kiwi Connection Report; 8 November 2006)

As this example highlights, RRS teachers had also become more confident in this cycle about the CAR research process itself—using it in increasingly focused and applied ways in relation to their teaching and learning processes. As one teacher observed: ‘[I feel the action research is] exciting, helpful to know … I am much more confident now. It’s good to see us working together as a school on this issue’ (Reflective diary, June-July 2006). Particular points of focus that emerged in this cycle included, among others: the assessment of bilingual students within rōpu and across the school; appropriate planning for the English component of bilingual programs; planning systems for bilingual programs; and fostering oral language development. These emergent points of focus, and their relationship to wider research on bilingual education, were to provide the basis for the particular rōpu-based action research projects undertaken in Cycles 3 and 4.

4.3 Cycles 3 & 4: Assessing and modifying bilingual pedagogy and practice at RRS

Research questions addressed:

- How can critical action research (CAR) extend RRS teachers’ bilingual PCK in line with best practices identified in the relevant research literature?

- How might this CAR process provide the basis for changing/modifying/improving teaching practices at the school, within the limits of a one-year pilot study?

In Cycles 3 and 4, each rōpu developed an AR investigation of their own teaching practices in light of the data and conclusions generated in the preceding cycles. Each of the four rōpu (including the English-medium ‘Kiwi Connection’) selected a pedagogical focus, with the specific aim of increasing their bilingual PCK within the particular teaching and learning contexts of their rōpu. Over the two cycles, each rōpu investigated the issue they had identified, drawing on the research-based knowledge about CAR and bilingual education that had developed over the course of the wider research project.

These applied investigations by rōpu proved to be the most significant aspect of the project for those involved. As one teacher observed of them: ‘the need to get and use PCK in order to be able to do [this] research … it made us aware of the need to know what we were doing and why’. (LA, 11 December, 2006). Another commented: ‘We actually [now] have the expertise within our own staff here at RRS to do these things and bring about change…. We now have the knowledge base … to do it within our own rōpu…’ (Field Notes: 11 December, 2006). As well as enhancing further teachers’ bilingual PCK, the AR investigations (detailed below) also contributed positively to students’ learning experiences: ‘[Students] have internalised many of the language learning strategies [promoted in the AR investigations] and are using them’.

A summary of each of the four AR investigations follows:

4.3.1 Te Whānau Whāriki (WW)—Māori-English medium rōpu

The key research question for this rōpu was:

- What are some effective ways of increasing the students’ use of basic interpersonal communicative skills (Cummins, 2001) in Māori?

Earlier AR observations within the rōpu had revealed that students could increasingly use Māori as the language of the school curriculum, as it was the prime focus for teaching and learning activities. However, because the students were primarily from English-speaking home backgrounds their informal everyday conversational Māori appeared to be less well developed. Findings confirmed that their students were limited in the range of informal conversational language in Māori that they used inside and outside the classroom.

WW teachers reviewed the literature on the place of oral language in bilinguals’ literacy and academic development and found rapid informal oral language development is crucial for second language learners who enter school with very low oral language proficiency in comparison with native speakers of a language. Drawing on the ideas of language development through the use of lexical chunking (Lewis, 1993/2003) and functions of language (Halliday 1973), they developed and trialled their own draft oral Māori assessment task (see Appendix 2) in order to collect baseline data on their students oral language competence in Māori.

Following from this, and in conjunction with other rōpu, WW teachers also developed researchbased oral language promotion activities based on vocabulary, ‘trans-languaging’, front loading and scaffolding within a wider language experience approach (see Gibbons, 2002). Their students were retested three months later using Mac Books with built in video capacity. Teacher observations and reflective diary material provided a second data set. It was found that students’ oral Māori language abilities had increased rapidly and noticeably in the rōpu over that period, as noted in the following reflective review:

Children demonstrated a growing awareness of the syntactic content of utterances, which in turn led to greater learner awareness of their role as language learners. They also demonstrated increasing appreciation of the form and style of language chunks. Children’s critical awareness was evident in seeing themselves as collectors of words/chunks … they began to use the strategies undirected (and) they internalized many of the strategies. (11 November 2006)

4.3.2 Mua-i-Malae (MiM) Samoan-English medium rōpu

The key research question explored by this rōpu was:

- How to accurately monitor and assess reading levels in Samoan?

The MiM rōpu in their AR investigation focused on developing measures for monitoring and assessing Samoan literacy development, particularly reading comprehension. Through the bilingual schools network, the team trialled the Finlayson Park Samoan Running Records within their rōpu, prose and reading inventories developed as part of an earlier action research project running at that school (see McCaffery, et al., 2003, for details). However, the MiM teachers found that entry levels set for the Finlayson Park students were designed for native speakers of Samoan, whereas the majority of the students in their rōpu were heritage/ second language learners. Entry levels and related materials were thus modified accordingly to account for these differences in language background. Additional issues that MiM addressed in this AR investigation included:

- Which language should answers to comprehension be given in?

- How can comprehension best be measured for bilingual heritage (2nd language) learners?

MiM initially believed comprehension answers should only be Samoan. However, on further exploration of the research literature, it was decided that responses in English would also be allowed since this demonstrated understanding, if not language development. Further probing to encourage a response in Samoan would then show the degree of Samoan language ability. MiM recommended changes to the Finlayson trial kits as a result of this AR process. The monitoring of reading was built in as an ongoing part of the MiM program and the liaison and sharing of RRS ideas and resources with Finlayson continued into the following year:

We are now well on the way to having a sound working reading assessment system for Samoan readers. We have learned a lot and this is what we set out to do. Our books are levelled and are being cross checked with Finlayson Park [school]. But we need to begin many levels below them, as our children are not native speakers of Samoan…. Understanding more about this difference and the issue of measuring testing and reporting comprehension remains to be resolved, but we are well on the way. (Field notes MiM Rōpu workshop: December 2006)

4.3.3 L’Archipel: French-English medium rōpu

The research question explored by this rōpu was:

- How can we monitor and assess oral French heritage language development more effectively/accurately?

This rōpu investigated how best to measure French oral language development in relation to those students for whom French was their heritage (2nd) language (cf. 4.3.1). While the native speaker entering school might have a vocabulary of around 2500 words, these children may only have a vocabulary of around 100-200 words at school entry. As one of the rōpu teachers observed: ‘Oral language is paramount—it takes priority but we didn’t know how to assess or promote effectively for non French speakers before’ (L’Archipel Field Notes, July 2006).

After examining all currently available published systems and criteria they could find on this issue, the rōpu agreed that First Steps (Education Department of Western Australia, 1997) best met the criteria for their heritage language learners. Using criteria from this scheme, L’Archipel developed and trialled an assessment of French as a heritage language, using a grid rubric continuum. Monitoring strategies developed included a listening task with multiple choice oral answers, sentence repetition, and picture dictation. Speaking, however, was the prime focus, so a ‘show and tell’ technique or a ‘tell me about this picture’ process was combined with a running record comprehension discussion.

As a result of the development of these assessment practices, subsequent oral language results in French for students in the rōpu improved. The data on student oral achievement were also subsequently combined with data on reading and writing levels on a modified Canadian Bilingual assessment schedule. Both recording systems have since been used to inform students and their families, and the full assessment strategy developed in these AR cycles is now built into the rōpu program. As two of the rōpu teachers observed after the completion of the AR investigation:

This assessment should allow us to target our oral language program more accurately so we no longer need to rely just on our assumptions. We need to find out what each child is capable of and what they need to learn in order to progress.

We can now do that very well. We are very pleased with this [CAR] research cycle. (Rōpu minutes, December 2006)

Our oral language measure has really worked well. It is based on the [relevant] literature and research as well as our own hard work in this project. Our grid works for bilinguals and until now we haven’t had a way of monitoring children’s oral development in both languages. (Reflective Diary, December 2006)

434 Kiwi Connection: English-medium rōpu

The research question for this rōpu was:

- How can we support student bilingualism and use it as a resource for program development?

At the beginning of the AR project, this rōpu had struggled to see how they fitted into a wider research focus on bilingualism and bilingual education (see 4.1). Over the course of the year, their awareness of the importance and relevance of bilingual research for teaching students in their program, many of whom were bilingual, increased significantly. This was demonstrated by the refinement of their research questions over time, with an increasing focus on bilingual learning. For example, in April 2006, their research question had been: ‘How can we include children from the many diverse cultural backgrounds and help them to feel a sense of belonging in our mainstream teaching environment, whilst still fostering Māori language development?’

By Cycles 3 and 4, however, there was an increasing awareness of the number of bilingual learners in their rōpu and the significance of their bilingualism to (and in) the teaching and learning process, features that the AR investigation subsequently undertaken by the rōpu confirmed.

For example, the rōpu began their investigation with a survey, followed by discussion with students. The aim of the survey was to explore students’ (and their wider families’) language backgrounds. It uncovered a wide diversity of language backgrounds among students and varying levels of bilingual proficiency:

‘Mum speaks Dutch all the time. It’s fun speaking Dutch. I like to speak Dutch.’

‘And it’s good being Tongan, cos’ I’m only one of heaps who can speak Tongan. If others [non Tongan kids] were speaking and learning in their own language then I would feel more comfortable doing it’.

‘I want to learn Irish so that I know it, so the Irish people can understand me’.

‘Mum knows some Irish. I would be happy to speak Gaelic at so long as I could speak it to someone’.

Reflecting on the findings, teachers expressed surprise about the numbers of bilingual students within their rōpu and the desire of many of the students who wanted to keep up or learn their own family heritage languages. The following reflective observation illustrated this new understanding:

I thought we were really different form other rōpu but we [actually] have a lot of bilingual children who we never saw in that way … now we have to recognize and value their bilingualism. We can’t just go on as we were before, thinking that this is the English-only program… (Rōpu leader; Field notes, December 2006)

The Kiwi Connection (KC) rōpu explored ways of building student bilingual resources into their everyday units of work and ongoing rōpu programs on the basis of the research discussions and activities undertaken over the course of the year. These developments included establishing two new initiatives, a language enrichment program and first language reading groups:

In light of this, we started a ‘Friday Enrichment’ (program) based on learning languages. We put our children into cross-age groups and established six language groups. The children rotate around these groups and are taught by “leaders’ (children who hold the cultural knowledge). The first session was a success, and we now have parents offering their knowledge and skills. Our children came away feeling proud and nourished by the experience. This has been set up as a permanent weekly aspect of the KC program. The groupings are: Tongan, Samoan Niuean, Cook Islands Māori, Portuguese, and other European. (KC rōpu report, November, 2006)