Note for readers

This report uses the terms “transience” or “transient” to describe families and students who have changed schools frequently. Gilbert (2005) noted that the term transient is the most commonly used term in New Zealand, but there is no “official” nationally agreed definition of what this term means in educational contexts. She also noted that the term has negative connotations. In this report, we have used this term for ease of communication, but are aware that the continual use of the term may contribute to the exclusion of students through a process of negative labelling and categorisation. We ask the reader to be aware of this issue.

1. Background, aims, objectives, and research questions

Background

This Teaching and Learning Initiative (TLRI) project emerged out of a request from the principal and teachers in a small rural area school. School staff observed that student transience complicated the learning and social experiences of some students. At the time of the request, the school had 17 transient students from Year 2 through to Year 13, five of whom were of Māori descent. In 2005, 37.6 percent of students on the roll were considered to be “nonstandard” school arrivals or leavers. Teachers and leaders in the school wanted to learn more about the effects of transience on students’ learning and social experiences, and to develop their teaching to enhance these students’ school experiences.

Transience at this school was described as affecting increasing numbers of students, with students attending school temporarily, or repeatedly moving in and out of the local community. These students faced unique issues in relation to their school experience. While the participating school had some procedures for tracking and uplifting transient students’ records, the teachers identified isolation, relationships with their peers and teachers, social outcomes, achievement (including “gaps” in learning), and participation in the school as issues that needed to be addressed. The school’s status as an area school was thought to add to the challenges, particularly when students engaged with a range of teachers across the school day. In this regard, the principal asked:

What is best practice for engaging these kids, for picking them up, and motivating them?

The research literature describes transient students as having difficulties making friends and socially integrating into their school, as being vulnerable to bullying, and as being academically and behaviourally at risk (Kariuki & Nash, 1999; Lee, 2001; Sanderson, 2003; Shafft, 2003). Significant gaps in students’ knowledge and poor prior records of their learning also place a strain on teachers who do not always have the time needed to adequately assess student achievement and engage them in the curriculum (Sanderson, 2003). Teachers in the participating school alluded to other barriers that compromised student learning. They described some students as having low aspirations for their learning, and as not engaged at school because they were aware that their stay was temporary, a point which is reiterated in the research literature (Sanderson, 2003; Shafft, 2003; Walls, 2003). The literature also refers to schools being financially and pedagogically stretched to meet the often high needs of its most mobile students:

. . . these high need, highly mobile students—through no fault of their own—increasingly are viewed as liabilities by school districts. . . . It is clear that the academic and social needs of highly transient students are going unmet and that schools and school districts have only limited capacity to address this challenge. (Schafft, 2003, p. 26)

In the New Zealand context, Lee (2001) noted that the experience of transient students is poorly understood, and systems and shared practices to support them are generally lacking. A recent study by the New Zealand Council for Educational Research (NZCER) on student movement (Gilbert, 2005) looked at educational issues in 20 schools in four communities. The study recorded high levels of overall student mobility in New Zealand, and participating schools reported a “major impact on their ability to manage, plan, and resource their core work” (p. viii). Gilbert looked at all students’ progress cards (the E19/22a cards) in Years 5, 8, and 11 to examine student movement between schools. She noted inaccuracies and wide variations in the way that student information was entered. Student achievement records were also difficult to analyse, because schools kept different types of records which were not always comparable to those found in other schools. The study found few differences in achievement between frequent movers and other students in the same year group, with some differences in mathematics achievement, especially in the earlier years, and possible differences in reading level at Year 8. No differences were found in attendance rates between the two groups. Gilbert also acknowledged that it is difficult to tease out the effect of transience on student achievement from other factors associated with transience, such as low income.

The main finding of Gilbert’s study was the negative effect of transience on schools. Transient students are regarded negatively because they are considered to disrupt school routines; they have a negative effect on schools’ performance; and schools must undertake further administrative work that is not provided for in the budget. Transient students are perceived as taking resources from other pupils, and disruptions occur because funding and school organisation is based on stable and predictable student cohorts. Schools in Gilbert’s project felt that they did not adequately address the challenges posed by transience, and argued for consistent and systemic communication and record keeping across schools and other agencies. However, it was acknowledged that changes in these areas would not reduce the disruption felt by schools (Gilbert, 2005).

The present project provided an opportunity for participating schools to identify, discuss, and research the particular effects, or disruptions, of transience within their own school, and to do this within the context of a learning community that focused on existing research and an action-research project. The researchers in the project explored the literature on school transience, particularly as it related to student achievement, social experiences, and effective teaching. The project focused on the process of change, and on the actions of teachers in classrooms and in a “community of practice” comprising teachers and experienced researchers (Lewis & Andrews, 2000). (see Research design and methodology)

Relationship to the strategic priorities of the TLRI

This project was related to four strategic priorities of the TLRI in that it sought to contribute to New Zealand’s educational and research efforts to reduce inequality, to address diversity, to understand the processes of teaching and learning, and to explore future possibilities.

Reducing inequality and addressing diversity

The project was particularly concerned with the school experiences of transient students whose relationships with teachers, school achievement, and social experiences were compromised by frequent shifts between schools. Both Gilbert (2005) and Lee (2003) have argued that one of the biggest problems is that schools “have just come to accept that little can be done about transience” (Lee, 2001, p. 3). Transient students may be labelled as “the problem”, and schools struggle with unresponsive educational systems, placing transient students at risk. The principal in the present study, for example, acknowledged that transient students could become “invisible” in the classroom.

While teachers are generally aware of transient students’ social and learning difficulties, Gilbert’s (2005) research suggests that teachers can find it hard to address these issues in the classroom. Some teachers fail to acknowledge the importance of positive and supportive social experiences for all students, and seem unaware of the centrality of these to student learning. In this context, teachers may not seek to address the difficulties that transient students experience socially (MacArthur, Kelly, & Gaffney, 2004). In contrast, Lee (2001) has suggested that change at the level of school culture can be achieved by:

. . . developing a welcoming culture within the school, creating non-violent environments so that the children are comfortable and won’t be bullied, and adapting the classroom programme to meet the needs of these children. (p. 3)

Similarly, Alton-Lee (2003) argued that schools can support marginalised students, including transient students, by actively promoting inclusion through the development of caring and supportive relationships with students and adopting strategies that respect and meet the needs of diverse groups of students. The literature identified key issues that need to be addressed in education. These include eliminating social, educational, and structural barriers to students’ participation, and supporting marginalised students’ agency as they actively shape their own social and learning experiences (Davis & Watson, 2001). This project aimed to address barriers to transient students’ learning and social experiences by exploring some of these processes.

Māori and Pasifika researchers

This project acknowledged that the cultural experiences of Māori students must be understood, respected, and supported in schools and through the research process (Bishop, 2001; Bishop & Glynn, 1999). The project included Māori students who moved frequently between schools. The Donald Beasley Institute’s cultural advisor, Hine Forsyth, provided support and advice about how to include Māori students in this research. Sarah Sharp, the Donald Beasley Institute’s Māori researcher, provided research support for Māori students and their families participating in the project. Also, Dr Khyla Russell (2006) provided useful information and advice about research with Māori in a self-reflective workshop for the Donald Beasley Institute staff, including the researchers on this project.

Understanding the processes of teaching and learning

This project aimed to understand the school experiences of transient students and, through this understanding, enhance teaching practices that challenge barriers and support student learning. It was concerned with transient students identified in the research as at risk in school, both academically and socially, and it aimed to build on the seminal work undertaken by Alton-Lee (2003) that teased out elements of teaching practice that enhance learning for diverse groups of students.

Exploring future possibilities

Through discussions in a community of practice, combined with a range of other data, this project wished to contribute to innovative initiatives for teaching that are based on students’ and teachers’ lived experiences. Students’ perspectives, in particular, are under-represented in the research data on teaching and learning, despite calls to highlight these in the development of teachers’ work (Davis & Watson, 2001; Smith et al, (2000). These experiences have the capacity to challenge adult-dominated constructions of childhood and school experience and open up new ways of thinking about teaching marginalised students.

It is also rare for research to explore different approaches to teaching and diversity within one school, the teacher agency associated with these different positions, and the various opportunities afforded for student learning. The proposed study allows such analysis to be undertaken, and contributes to an understanding of the complexities involved in moving whole schools towards inclusive teaching practice that addresses the needs of diverse students.

Aims and objectives

The project aimed to coconstruct teacher knowledge about teaching and learning through teacher professional development focused on a community of practice and action research. This approach emphasised research-based teaching practices.

This project involved a qualitative case study of one school and involved enquiry at two levels:

- Level one: A study of the impact of an action-research project and a community of practice on teacher behaviour and student learning and social experiences.

- Level two: An action-research project to be developed by the researchers, principal, and teachers within a community of practice, to enhance transient students’ social and learning experiences.

The project had three main objectives:

- to enhance teachers’ understanding of transient students’ learning and social experiences through an exploration of data from extant research

- to support teachers to coconstruct knowledge about teaching and learning through a community of practice, and to critically reflect on their teaching and on students’ learning

- to develop and evaluate through action-research teaching initiatives that address barriers to and enhance transient students’ learning and social experiences.

Research questions

Teachers and researchers collaborated to develop the research questions. The following questions guided the project. Further questions relating to the development of research-based teaching approaches emerged as the project proceeded.

Research question 1 (level one)

How does a community of practice and action research:

- enhance teachers’ understanding of transient students’ learning and social experiences?

- contribute to changes in teachers’ assumptions and beliefs about classroom practices and student learning?

Research question 2 (level one)

How does a community of practice involving researchers and teachers:

- develop and sustain itself?

- with action research, contribute to the coconstruction of knowledge about teaching and learning?

Research question 3 (level two)

How does a community of practice:

- develop and evaluate teaching initiatives to improve student learning, and social experiences?

- identify what specific school initiatives contribute to improved student learning and social experience?

2. Research design and methodologies

The study used qualitative methods of enquiry. This approach allowed the voices of transient students and their families to be heard so that teachers could reflect on their experiences (Bishop & Glynn, 1999; Schwant, (2000); Smith et al., 2000; Stake, 2000; Yin, 2003). Qualitative enquiry is concerned with understanding what others are saying or doing. Social actions are understood to be inherently meaningful and the researchers’ task, along with that of the community of practice, was to understand a particular social action and the meanings that constituted that action (Schwant, 2000). Social constructivism is one philosophy used to explain the aim and practice of understanding human action through qualitative enquiry. A social constructivist approach rejects the idea that knowledge is discovered and argues that it is actively interpreted and constructed through researcher participation, as is inherent in a reflexive community of practice and action research. This study involved a single school, or case study, and provided an opportunity to learn in detail about complex social phenomena and transient students’ lived experiences in their natural context, the school, and to study teaching qualitatively through a close relationship with students and teachers (Stake, 2000; Yin, 2003).

A researcher and teacher partnership approach was considered most appropriate to the project as it encouraged: an ongoing process of critical reflection which is a central tenet of a community of practice (Buysee et al., 2003); teacher initiation and direction; and the personal and whole-school pursuit of change in teaching practice (Carr & Kemmis, 1986). Teachers in the school were involved in all stages of planning and decision making in the project. An action-research model and the development of a community of practice was initially discussed with the principal and deputy principal as a method by which teachers could explore and improve their own teaching practice. This study, at both levels, received ethical approval from the University of Otago Human Ethics Committee, and adhered to key principles of confidentiality, anonymity, informed consent, and right of withdrawal (see Appendix A for the participant information sheets that were used in this project).

All data from level one of this project were collected by Dr Jude MacArthur and Dr Nancy Higgins. Level two data were gathered by the researchers and teachers in community of practice. Level two data comprised information about students’ learning and social experiences in school, and was discussed within the community of practice. Transient students and their parents or caregivers were interviewed by the researchers—teachers did not have direct access to the transcripts of these interviews. Salient issues from these interviews were shared through the community of practice. While students were identified in these discussions, identifying features of participants have been removed from this report and pseudonyms have been placed in the data for presentations and publications about the project. The pseudonym, Wooldon, is used for the school and community in this report.

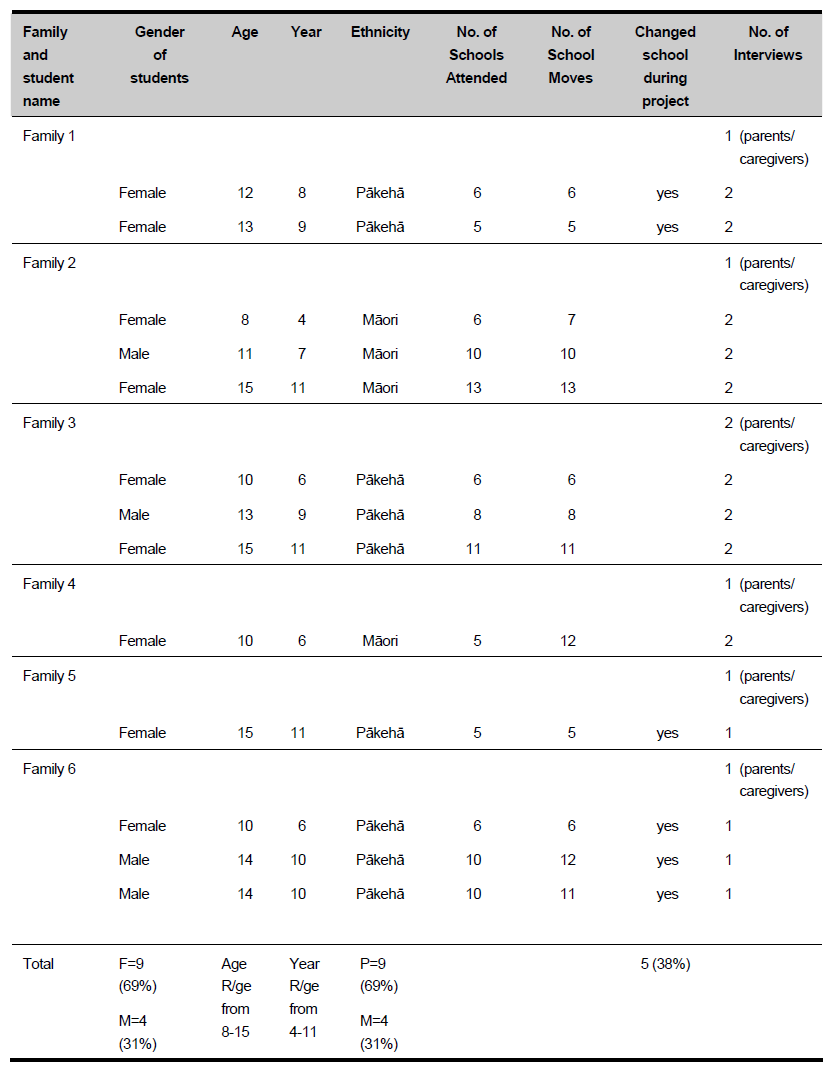

Participants

Participants in the community of practice were the principal, deputy principal, and four teachers at the participating school. Participants in the action-research project included community of practice members themselves, as well as identified transient students at the school and their parents. Informed consent was obtained from all participants. Student participation required the informed consent of the students themselves, and from their parents or caregivers. A total of six families and 13 students (see Table 1) participated in the project.

Table 1 Participating students

Community of practice (level one)

The project began with the development of a collaborative community of practice between researchers, the school principal, deputy principal, and four teachers. A community of practice comprises a group of professionals and relevant others, who learn and work together around a particular topic to improve their educational practice (Buysee et al., 2003, Lewis & Andrews, 2000). Using Palincsar et al.’s (1998) example of communities of practice, researchers met initially with the principal, deputy principal, and teachers for a professional development day about reflective practice techniques, transience, and action research. Following this, meetings were held to work through an action-research process, and for teachers to share their classroom practices and experiences and, thus, coconstruct knowledge about teaching transient students. The school was funded for the equivalent of 40 days teacher-release time to be used for research activities such as community of practice meetings, meetings with other staff, and planning for teaching. Two teachers also attended the New Zealand Association for Research in Education (NZARE) conference at the end of 2000 with the researchers, and participated in a joint presentation based on this project.

The emphasis on developing a community of practice in which researchers and teachers coconstruct knowledge about teaching and learning changes the linear manner by which knowledge is traditionally handed down to teachers, and instead promotes an organic approach whereby teachers can contextualise their learning in their own classroom experience (Buysee et al., 2003). Communities of practice provide opportunities for deep learning, although it is acknowledged that some teachers can find such an approach challenging since it eschews the notion of a “quick-fix” or expert oriented approach (Graham et al., 2004).

Data gathering (level one)

Data within this study was gathered through an ethnographic approach, using field notes, observations in classrooms and in the school grounds, and open-ended conversational interviews with participants. Data included:

- in-depth and open-ended interviews with the principal, deputy principal, and teachers in the community of practice about their teaching practice and professional development ideas relating to their action-research project

- researchers’ field notes and transcripts from community of practice meetings y researchers’ field notes from classroom observations (including notes from informal discussions with students and teachers)

- archival notes (school mission statement and school policies)

- interviews with transient students and their parents or caregivers about the students’ educational experiences during the project.

Interviews (level one)

Open-ended and conversational-style interviews were conducted at the beginning of the study with all participating transient students, their parents, and teachers in the community of practice. One family arrived during the study for a short time. This family was interviewed after they moved to another community. The other students in the study were interviewed again at the end of the project. Some of their parents were also interviewed at this time if they were available. The participating teachers in the community of practice were interviewed in the middle of the project, and at the end. Students were interviewed in their own home, either alone or, if they wished, in the presence of their parents. In all the interviews, opportunities for free interaction, clarification, and discussion were pursued through the use of open-ended questions. Questions were framed carefully to maximise reciprocity through the negotiation and construction of meaning between the researcher and participant, ensuring that the researchers did not promote their own agenda or see the interview purely as a data gathering exercise (Bishop & Glynn, 1999). All interviews were digitally recorded, and transcribed for analysis.

Interviews with students focused on the their perspectives on their school experience and included general questions relating to their learning and social experiences at school (see Appendix B for the student interview guide). Interviews with parents focused on parents’ interpretations of their children’s school experience (see Appendix C). Interviews with teachers focused on professional development and adult perspectives on transience and teaching, including the contribution and role of teachers in relation to students’ educational experiences (see Appendix D).

A Māori researcher was part of the research team and was available to interview families identified by the school as Māori. While no participating families were identified in this way, two families indicated they were Māori in the first interview. Subsequent perusal of school records revealed one family was correctly noted to be Māori and the second was not. The researchers informed the families that a Māori researcher was available to work with them on the project if this was their preference. Both families stated that they were happy to continue the relationship with the Päkehä researcher. The researchers informed the school and sought advice from cultural advisors and the Māori researcher on this issue, and continued to work with the advisors and Māori researcher throughout the project.

Observations (level one)

Field notes were recorded during community of practice meetings, and the last meeting was audiotaped for transcribing purposes. Minutes from the notes were provided to the community of practice members for future planning purposes. One researcher facilitated the meeting while the other took notes. The researchers met regularly to discuss the project and their observations.

Archival data (level one)

The school’s mission statements, annual reports, and professional development policies were examined by the researchers to contextualise this case study (Stake, 2000).

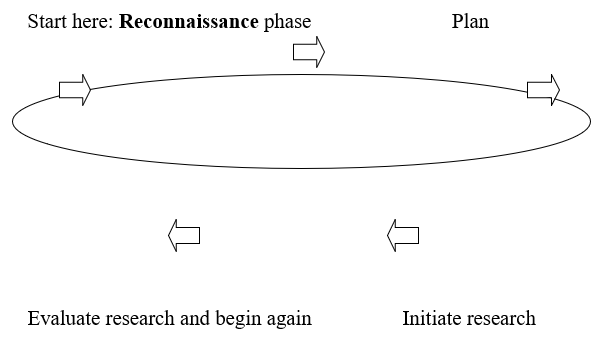

Action research (level two)

The principal, deputy principal, and teachers were supported by the two researchers working with them in the school to develop an action-research plan (Mills, 2003) and work through the steps in an action-research and professional learning and development process. Action research involves providing opportunities for teachers to critically reflect on their own and others’ practice and on the underlying theories, values, and assumptions that inform that practice. It provides a method for “testing and improving educational practices, and basing the practices and procedures of teaching on theoretical knowledge and research organised by professional teachers” (Carr & Kemmis, 1993, p. 221). Action research encourages action for school change (Kember, 2000; Mills, 2003). It is a research process and strategy that is collaborative, relevant, and practical in that the research is not divorced from what happens in classrooms and schools (Meyer et al., 1998). Professional learning communities can encourage the development of a shared school vision so that successful and positive change occurs in a school’s culture (Lewis & Andrews, 2001).

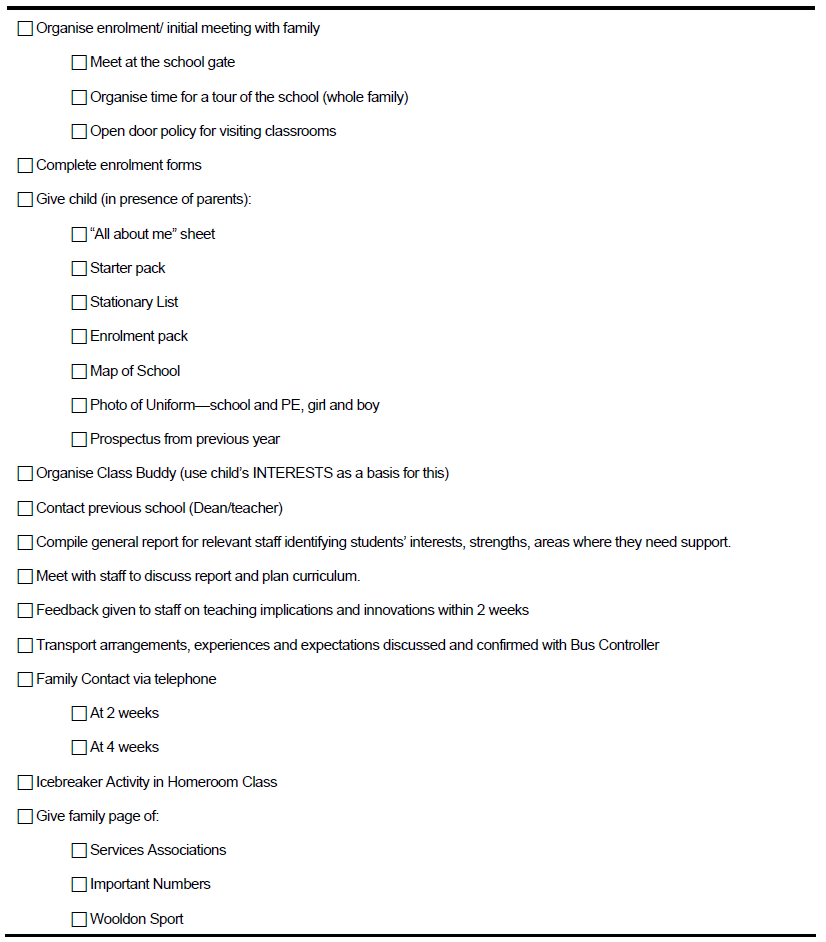

At the first meeting of this project’s community of practice in Term One of 2006, the researchers introduced the project and facilitated a discussion of the key themes about transience arising from the literature. The teachers, in turn, reflected on the salience of these themes in relation to their own teaching practice, and identified areas of strength and weakness in the school. A book of relevant research reports and readings was compiled for teachers about teaching diverse groups of students and transience. In subsequent meetings, strategies to address the school’s specific challenges in regards to transience were discussed so that an action-research plan could be devised. At the end of the term, it was agreed that the action-research plan would focus on developing school-wide guidelines to enable the school to enact a consistent enrolment process for transient students, and to enhance their sense of belonging at the school. The second area of focus was to concentrate on developing improved teaching practices for transient students that were grounded in the child’s lived experiences, strengths, and interests. Eventually three specific students were identified through their initial interviews as having particularly poor social and learning experiences that needed immediate attention and research.

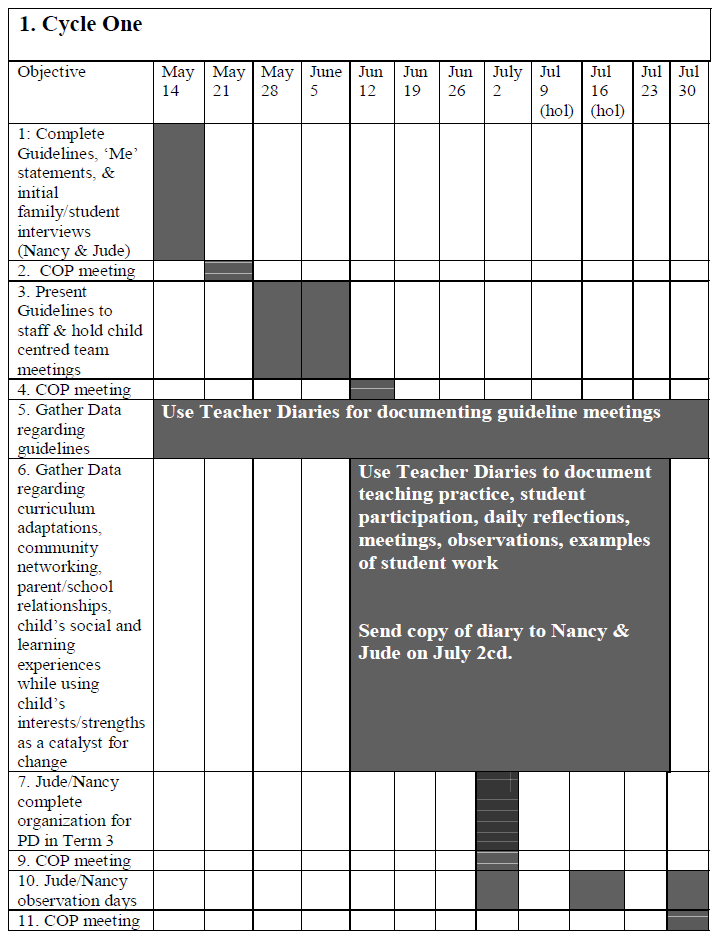

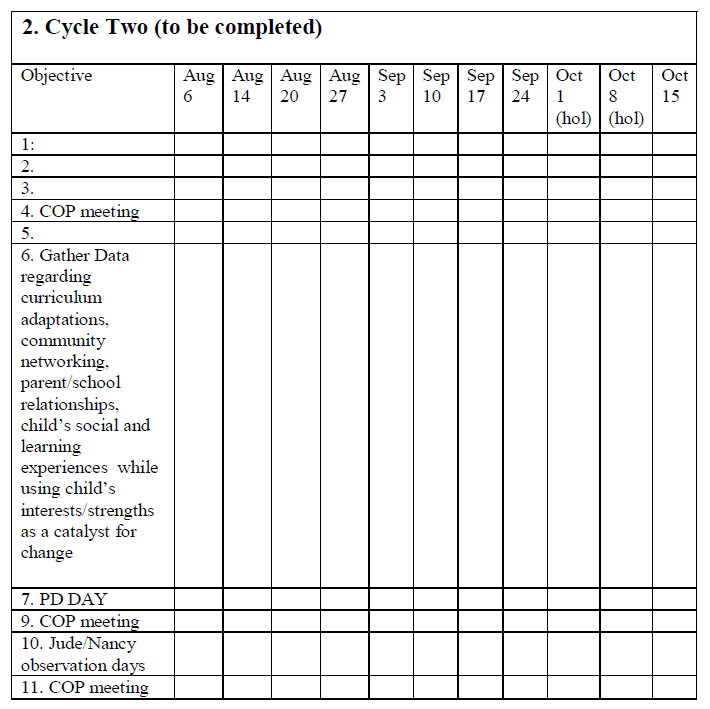

The action-research process involved proceeding through a research cycle of five steps across the period of one school year, although initially it was hoped that two research cycles would be completed. The research cycle included:

Step 1. The teachers began with self-reflection about issues and concerns relating to the experience of transient students, and the implications for teaching at the school. This meeting also included a focus on issues for transient students identified in the research literature.

Step 2. The community of practice developed a plan for improving their teaching practice to enhance transient students’ educational experiences.

Step 3. This plan was implemented through teaching practice and data were gathered.

Step 4. The plan was evaluated through critical reflection by individual teachers and the community of practice.

Step 5. The final step was to begin a second research cycle taking into account the knowledge gained from the first research cycle (Kemmis & McTaggart, 2000; Mills, 2003).

The school’s action plan

The school’s plan aimed to develop and implement an organisational protocol (referred to in the community of practice and in this report as “the guidelines”) and structure that supported transient students’ learning and social life at school and in the community. The challenges that needed improvement included: school structures (facilitate, identify barriers); relationships with families; assessments; teaching practice; community relationships; and social relationships. Thus, the school decided to develop a protocol and structure based on developing:

- positive relationships between transient families on the one hand, and both the school and community on the other

- students’ interests and strengths

- students’ social relationships.

Homeroom teachers would implement the new guidelines by:

- developing a supportive home–school relationship

- leading discussions with other involved teachers

- collecting assessment data (including data on students’ interests)

- implementing related teaching programmes

- fostering community involvement.

Data on the implementation of the guidelines in general and about the subsequent educational experiences of transient students included:

- data on developing the guidelines

| – | meetings with COP members |

| – | meetings with other teachers |

| – | meetings with whole staff |

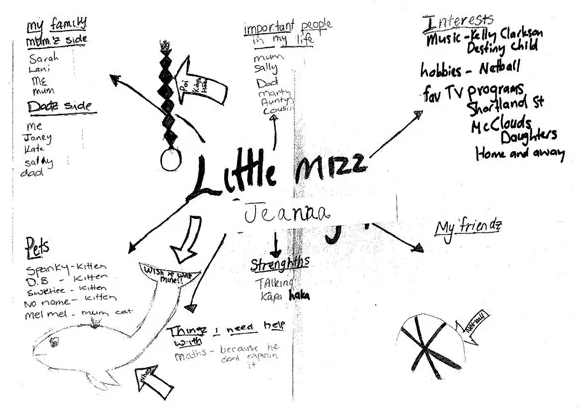

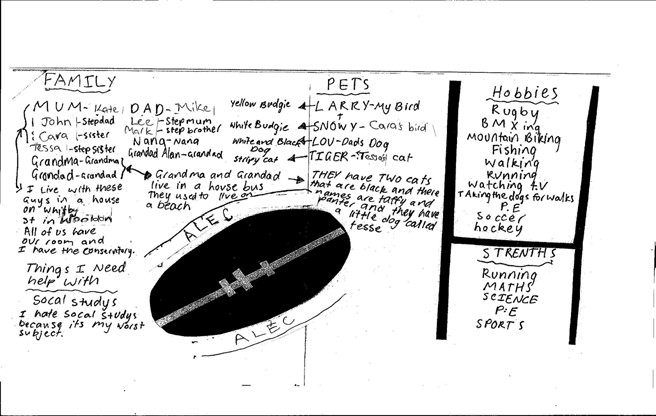

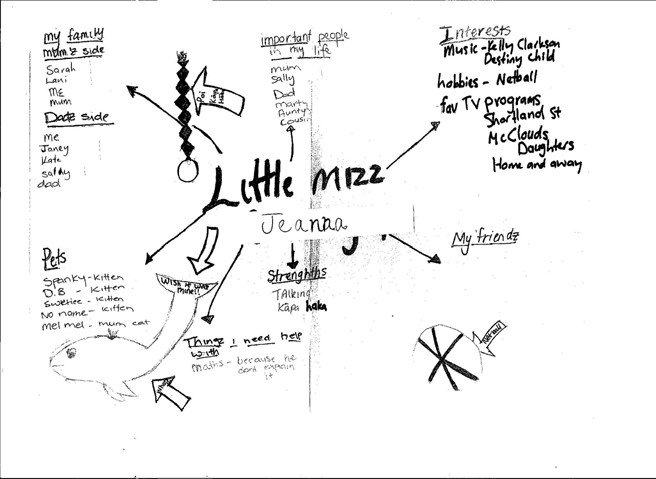

- data on students’ interests (children’s “Me” statements)

| – | interests |

| – | strengths |

| – | family |

| – | friends |

| – | pets |

| – | important people |

| – | things I need help with |

- data on teachers’ classroom practice and their relationships with students, families, and community members, which teachers would record in a daily teacher diary. Diary entries could include:

| – | what the teacher did in relation to students’ strengths/interests |

| – | informal observations of and discussions with students |

| – | assessment data |

| – | personal reflections on teaching and learning |

| – | discussions with parents/other teachers about students’ learning/social relationships. |

Data gathering (level two)

The researchers and the teachers gathered data for this level of the project to document changes in teaching practice and student learning and social experiences through:

- community of practice members’ diaries (from observations in classrooms and the school grounds, and in community of practice meetings)

- researchers open-ended interviews with community of practice participants (as in level one)

- researchers’ open-ended interviews with transient students and parents (as in level one)

- archival data (teaching plans, student work samples, and student achievement data).

Observations: level two

For this level of the project, the researchers observed students and teachers in classrooms and in the school grounds. To understand teachers’ and transient students’ experiences of school, the researchers engaged in a process of two-way exchange with students and teachers. The community of practice, in general, was encouraged to use the observational approaches in their classrooms that Davis (1998) recommended, which is (i) to be reflexive and have a clear role within the student’s world, (ii) renegotiate the power relations between researcher/teacher researcher and the transient child to establish the best possible “participant” relationship, and (iii) accept that throughout the research process the teacher’s and researcher’s ethics, roles, and tools will be put under strain, questioned, and negotiated. Also, it was expected that ideas about giving primacy to the perspectives of all participants, rather than subsuming them to the researchers’ own views and interests, would guide the community of practice’s data collection process (Smith et al., 2000; Luttrell, 2000). The researchers also used their observations to talk with the participating teacher or child about surrounding events, and to check the teacher’s or child’s own understandings and interpretations of those events. Participating teachers and researchers were expected to record these events and discussions in field notes.

Data analysis

Level one data, on the impact of an action-research approach and a community of practice, was the responsibility of the researchers. Level two data, on the impact of the action-research plan, was shared and analysed within the community of practice. The data for both levels of this project comprised archival document analysis, field notes (observations and recorded conversations between the teacher researchers/researchers and students), and transcripts of interviews. Some archival material (student work samples and student achievement data) were used as data to contribute to an understanding of teaching practice and transient students’s educational experiences.

The data were analysed through a process of collaborative analysis and co-construction between the researchers and within the community of practice as the project proceeded. Coding the data was done through the sharing of meanings and the identification of common themes and emergent patterns. Also, at the end of the project, the researchers undertook some inductive analysis of the data and identified key thematic categories that had particular implications for teaching practice and transient students’ educational experiences. These themes included:

- rural mobility is linked to a better life

- mobility can be a consequence of negative school experiences

- good teachers explain things, are friendly, are fun, and are not grumpy

- transient students are at risk academically

- transient students have difficulty making friends, are bullied, and are at risk of becoming “an outcast”

- rural communities are “way too small” and have unique challenges in regards to difference.

3. The lived experience of transience

This section describes the key themes relating to students’, parents, and teachers’ lived experiences of school transience.

Rural mobility is linked to a better life

The six families in this project shifted to Wooldon for positive reasons and described lifestyle improvements as their main motivation for moving frequently. Four of the families moved because they believed the community was safe, the school was responsive, and housing was affordable. One family, for example, moved there because the community was described as safe by a friend who lived locally:

He was the one that basically talked me into moving. But the main reason was I arrived home one night when I was in the city, and a guy held a knife to my throat. I just couldn’t go back in the house after that. So I thought Wooldon was a quiet place and safer for the kids hopefully. . . . And then when I was away from the house, it got broken into two or three times. All my whiteware got pinched. . . . It just felt really unsettling and quite stressing basically.

One parent had searched for a community where she could buy a house and live a reasonable lifestyle with her disability, and Wooldon met her requirements. Another described Wooldon as a place where her daughter could have more freedom. She said:

You have got more freedom, like you have more freedom here because you know where your kids are. In the city, if Tania wanted to go out and be out until 9 o’clock at night I’d say “no”, because it is a big place. Whereas here, you actually roughly know where your kids are.

The Waverly family moved each year to follow seasonal work. They moved to Wooldon because they knew people in the area. Mrs Waverly described her son, Mark, as “running amuck at his previous school”, and she valued the fact that Wooldon was “kind of like a kid jail” because “there was nothing to do except sport basically”.

The Connor family had moved to follow work opportunities for the father. In six years, they had lived in six different places. Mrs Connor said:

Okay, around about six years we have been in the South Island, so we moved from the North Island, to Town A. We went from Town A to Town B, from Town B to Town C, from Town C to Town D, from Town D to Town E, and then up to Wooldon.

Overall, their three students had attended between six and eleven schools. The Smith family’s children had attended between 6 and 13 schools and while the family had moved for a variety of reasons, these were mainly work- or income-related. Mr Smith worked in a rural industry, and they had decided to live in a house in Wooldon where rent was comparatively inexpensive.

Families in this study moved for a variety of reasons, and this variation in families’ experiences is reflected in the research literature (see, for example, Gilbert, 2005; Sorin & Iloste, 2003). Three families followed opportunities for work, but others moved in search of a better and safer lifestyle. Poverty was a concern for some families, and Wooldon provided affordable rents. What seems most important is that families’ decisions to move within and between districts were positive, and were motivated by a desire to improve their circumstances, including improved opportunities for their children.

Mobility can be a consequence of negative school experiences

In Gilbert’s (2005) study, the participating principals stated that it was very uncommon, but not unheard of, for children to be moved because families were dissatisfied with their school. In this study, three families described changing schools within the same district as a consequence of their dissatisfaction with their child’s school experience. Anna had a disability that affected her learning, and had attended 13 schools. Her parents would inform schools about this, but in their experience some schools took too long to acknowledge Anna’s needs and to organise learning support:

| Mother: | Some of the schools Anna moved from. We were in the same district but the school wasn’t actually doing what we had asked them to do for her because of her problems. And she was not getting the help that she needed so we moved her to a school that gave her the help. A couple of times that happened. | |

| Father: | That you move in to a new school and go and see the principal and you tell them about Anna’s problems. And it is normally six months before they come back and say “Do you realise that Anna has got problems?” |

For this family, transience could interact with unresponsive school systems to cause another school move. Consequently, Anna faced further challenges to her learning.

One mother noted that she and her daughter were abused by a teacher in a small community they had lived in previously:

We had a breakdown with the teacher where he had assaulted her and made a bruise like this on her arm. He grabbed her, and he wouldn’t speak to me. So her father rung him and said he had never been so insulted in his life because the guy threatened us and said that if we took any action that he would make sure that we wouldn’t have (our daughter), that she would be taken off us. So I spoke to my mum . . . and she just said ‘look, you have got to live in the bloody area, best take her out of school.’ At the time I was working in the city. So every day for a year and a half we traveled. . . . You had to leave here by 7.30a.m. to make sure we got her to school on time and me to work on time.

This student then moved again to a school where she and her parents had enjoyed positive experiences in the past. This was her fourth enrolment.

Inga, who had an intellectual disability, changed schools within the same city because her parents, who no longer lived together, could not agree on a school that would be best for her. Mrs Jones said:

And when Inga finished Standard Four, she had to go to a different school. And I wanted to send her to (A school) where I was living. . . . So I enrolled her there and her father turned up, took her out and went and enrolled her at (B school where he was living). . . . So I took her out of (B school), put her back into (A school), and he just left it at that. That’s when he stopped seeing her.

Good teachers explain things, are friendly, are fun, and are not grumpy

Consistent with the findings of Adrienne Alton-Lee’s work (2003), this study found that the relationship between teachers and students is a critical part of quality teaching approaches. AltonLee describes pedagogical practices that enable classes to work as caring and inclusive learning communities. Caring interactions between teachers and students enhance student learning, and responsive pedagogies encourage teachers to focus on students’ experiences and learning processes. Students in this study consistently described “good teachers” as those who formed positive relationships with students; were kind; were “nice”; and took time to explain school work so that students could understand what was required. Now in secondary school, Jeanna described the teachers she had liked at school:

| Jeanna: | At X College the teacher explained our science . . . . I just liked my form teacher, she was nice. . . . | |

| Researcher: | Like what does that mean if you are a nice teacher? | |

| Jeanna: | She is just nice with it. If you don’t understand something she will explain it to you until you do understand it. |

She also said that good teachers were able to get along with students:

| Researcher: | What makes a good teacher? | |

| Jeanna: | They would have to get along with the children which not very many teachers do here. . . . They get grumpy. |

Inga similarly described her favourite teachers as helpful, fair, and trustworthy, and she said that she liked to reciprocate her teacher’s help:

Well (the best teacher) would have to be at School A and it would be Miss Q. . . . She was really nice and stuff. . . . Miss S. She was really nice. . . . When someone was naughty, she would like give detention but like she won’t yell at them like the other teacher that was there. Like, Mrs T, she grabbed you by the wrist and pulled you. . . . And at this school (good teachers) would have to be mostly Miss B, and Miss C. . . . Miss C is just really nice. She like helps me with problems. . . . She’s just like really helpful. I like to help her. . . . She’s a really friendly teacher. And Miss B, what I like about Miss B is if I tell her stuff she won’t tell anyone, and yeah.

Britney (aged 10) explained that good teachers made learning “fun” and were understanding when students experienced difficulties in their life:

| Brittney: | Mrs I, she would always make things really fun and make sure everything is there. And she always used to bring her pet rabbits to school. And we had spare time with her feeding and playing with them and they would hop around. . . . When we have been good, sometimes she would let us have things like (part of) a day off. . . . She would get us to like work together as a team and then she would give us challenges like a treasure hunt, but you would have to work out a certain times-table and then do it, which would give you a hint to where the next clue is. So it was like working but playing. | |

| Researcher: | Right so what do you think makes a good teacher then? | |

| Britney: | Um, I think fair and an understanding teacher. Like if something bad happened to you, like someone who might at least try to understand and not say like ‘Oh well that’s no excuse’, kind of thing. And someone who is nice and things like that. | |

| Researcher: | Right, that sounds like a good teacher. And here, if you had to make suggestions to a teacher here, how do you think they could teach better. | |

| Britney: | Make it a little more funner, because it is just like plain out boring. Maybe add some like games into it and make it more funner. |

Tania (aged 15) described her favourite teacher as having personality characteristics that made her easy to relate to:

Her attitude was amazing, she was just the best teacher that I have had in any school. . . . She was fun, outgoing, she was just more like a student. . . . She was an older teacher but she always looks young.

Kate (age 15) stated that good teachers were empathetic and listened to students:

Um, just kind of putting their feet in someone else’s shoes and kind of going back and trying to explain the way that they would understand if they were our age. And just by actually listening rather than saying ‘do this and do that’. (Good teachers) try to make it practical and know what you are trying to say.

Students consistently told us that they did not like teachers who were “grumpy”. One student said that good teachers were caring and not intimidating:

| Child: | She was just a brilliant teacher. She cared for everybody. She treated you nice. She didn’t raise her voice ever. . . . | |

| Researcher: | Do you think that your teachers could teach you better. | |

| Child: | I think they are doing as good a job as they can. . . . | |

| Researcher: | Would you have any suggestions for them to make them better teachers. | |

| Child: | If Mrs X. would stop intimidating my sister. . . . Yes, my little sister come to find me one day and she was in tears and miserable. |

This student felt that teachers helped students to learn when they listed to students and acknowledged their learning needs:

| Researcher: | What do teachers do that make it hard for you to learn? | |

| Child: | Um, I don’t find it hard to learn. I find it hard to concentrate because all the kids are being annoying and talking. | |

| Researcher: | Have you ever talked to your teacher about that? | |

| Child: | Yeah, in my wee notebook I do. I have got a notebook. I take it home and get it signed by dad or mum. . . . Yeah, what I have done at school, like ‘the day was great’, or I don’t know, ‘the day was crap’. |

The parents in this study, like their children, also agreed that teachers needed to like children, and be approachable, fair and consistent. When speaking about possible school improvements, one parent said that schools needed to be understanding of, and communicate with parents about, transient students’ social and academic experiences. She said:

I think maybe that they could be a bit more understanding that the kids have moved a bit. I don’t think the schools are that understanding. It is not the children’s fault that they leave schools so often. It is the parents’. I don’t think they support them enough in that respect. Like for instance, with my daughter, to me when they got her file and they seen the struggle that she has had throughout her school, that they could have kept in contact with me over it. I hear nothing so I don’t really know whether she is doing any better than what she was.

Another parent acknowledged that parents should be aware in turn that the home–school relationship goes both ways, and that teachers, like parents, can have their “off days”. She said:

I mean even though she is a teacher, she is human and we all have our bad days. God knows my child knows when I am having one because I yell and scream. I mean I can be horrible.

She described good teachers as child focused, consistent, and fair with clear rules for all of their students. When describing her child’s favourite teacher and school, she said:

Miss P was lovely. In fact that school went through quite a few teachers and they just seemed to have the knack of getting brilliant ones. I mean really kid focused and fair. . . . Clear rules and don’t bend them. . . . They can’t have one rule for one kid and another rule for another because that’s wrong.

Mrs Smith noted that good teachers were able to quickly assess her daughter, Anna, address her learning needs, and listen to parents’ perspectives on their children’s learning and social experiences. She said:

I transferred Anna because of bullies . . . and her teacher and I had an interview after a week and her teacher had picked everything up. You name it – she picked it all up in that one week. She was brilliant.

Transient students are at risk academically

All but two of the students in this study experienced academic and/or social difficulties in the classroom. Three of the students had significant academic needs. Two of these students had a diagnosis of mild intellectual disability and they experienced both social and academic difficulties. Overall, some of the learning difficulties were linked to transience, with participating students describing inconsistent progression through the curriculum because schools do not work to a standard timeline for curriculum delivery. Some students described repeating the same work, or missing out on areas of the curriculum altogether. Kate (aged 15) said:

(Moving) makes it hard because like one school will be doing the subject and then you go to another school and you have only done half of it and they have already done it so you kind of miss that bit out. . . . Different schools just do different things. . . . Last year these guys did Year 11 things and my school didn’t do them, so I missed out on the credits and now I have got to do them. And they have already done it. So it is a lot of work to catch up after you first started.

Anna (aged 15) said that she was repeating work that she had already done through Correspondence School, but that she didn’t mind this at times:

Um, for English and maths it is stuff I have already done last year when I did correspondence . . . It is doing it again. . . . Some days I think its okay to do it again and some days I don’t.

Anna’s parents were also aware of these issues, and suggested that more consistent curriculum delivery between schools would be advantageous:

| Mrs Smith: | I think the curriculum should be mapped because for the likes of us and thousands of other transient type people, especially in the farming community, you move to a different area, the kids move to a different school, and well that school did that part of maths last year . . . But now they are doing this part so they miss certain parts of it. | |

| Mr Smith: | They totally miss. | |

| Mrs Smith: | Or they redo so much | |

| Mr Smith: | Yeah they double up on stuff or miss out on stuff, and I think that (the curriculum) should be mapped at least. . . . So, for example, in) the first term, this is what has to be covered, then they are not missing as much. |

The teachers in the community of practice also described their frustration at students missing out or doubling up on aspects of the curriculum, but they were unsure how to address the challenges that they presented. One teacher stated:

Often these kids are behind the others. They don’t quite fit in and they come in at odd times of the year so you are half way through something and you have just got to make do. . . . I mean I have got one in my class and she is extremely demanding. She is coming up and kind of touching base with me all the time. . . . Yeah, physically and mentally. It is quite intriguing. So there’s gaps. . . . And it is just the luck of the draw what they have (learned).

Another teacher found it difficult to keep transient students interested in class when they had either missed the work or were redoing it:

When you are constantly on the move there are going to be areas of education missing, (and) if you have gone into a class room and you have done something before, it must be really boring for that child. They turn off easy and you have lost that interest. How do you get it back? You have got to. And I do feel sorry for them.

One student had lost her interest in school, was truant, and was going to be moved to a foster home and new school because of this, illustrating again that issues relating to transience can bring further transience:

| Researcher: | How do you think you do at school. | |

| Jeanna: | Bad. I hardly ever come to school. | |

| Researcher: | Oh is that right, how come? | |

| Jeanna: | Because like um Christine my social worker, was meant to be getting me correspondence but she hasn’t and I don’t get along with school. I just stomp off and stuff. . . . I might be moving tomorrow, like going with CYF into a foster home. | |

| Researcher: | Is that something you want to do. | |

| Jeanna: | No. That’s the law, if I don’t go to school. |

Three students also had significant learning needs that required responsive assessment and teaching. These students’ experiences highlighted the need for accurate record keeping and for timely and fluid information sharing between schools. For example, as this project progressed, it became clear that one of the student’s records in this study was incomplete. Inga’s mother indicated that Inga had been diagnosed with a mild intellectual disability, but the teachers at Wooldon School, which was her sixth school, had no record of this. This record was later obtained, but Wooldon School did not have time to make the relevant contacts and referrals needed before this family moved on to another school. Inga’s mother had asked for teacher aide support in previous schools, and had stopped asking because she was consistently told that resources were not available. Inga occasionally had additional reading support on a one-to-one basis. During Mrs Jones’ interview, she brought Inga’s reading books out to demonstrate Inga’s reading level:

| Researcher: | So this is a level 2 book she has got here. It says on the back here. ‘Age 5 to 8. For people that are beginning to read’. | |

| Mrs Jones: | Yeah, and she is 12 and she has trouble with some of the words as well. |

On the whole, though, the parents of the three students with significant learning difficulties in this project appeared to be poorly informed about the education support that was available, and the exact nature of their child’s learning difficulties. For example, one parent stated:

It started off at School B when she used to walk with one foot in that way and everything would flow like she is only just coming up to her reading level now but that wasn’t due to moving schools. That had something to do with the way her foot was. I can’t remember, but it was under that moderate needs thing, and they used to come and do a study on her every now and again at school. And the last one she actually got clearance that they didn’t need to look after her any more.

However, later in the interview, she acknowledged that difficulties remained, and she was uncertain about how whether these were being addressed at school:

| Researcher: | (Have you) had any contact with the school at this stage about where your daughter is at with her reading and whether she needs extra support? | |

| Mother: | No | |

| Researcher: | So you are not too clear about where she is at in that regard. | |

| Mother: | No I have no idea where she is now. . . . That’s just as much my fault as the school’s, I should have kept in contact but with working here (over an hour’s drive away), I just can’t.Researcher: |

Students and parents also talked about the importance of appropriately matching teaching with the student’s ability, so that students would experience success and not failure. For example, Mr And Mrs Smith did not want their daughter to fail, and were unsure about the NCEA system. They were confused about Anna’s achievement across the curriculum at secondary school, noting variations in teacher’s description and knowledge of her abilities:

| Mr Smith: | One teacher . . . in the end of last year’s report, was saying how he wants her to be mainstreamed. He said she is coping really well (but) one of her hardest things is English, trying to comprehend the whole thing. Comprehension is one of the things she struggles with the most and to say that she could be mainstreamed in English, for School C, well NCEA Level 1 or whatever it is. | |

| Mrs Smith: | They have changed everything so much. I never know what it is. | |

| Mr Smith: | I know how hard School C English was. | |

| Mrs Smith: | And Anna would never be able to do it. | |

| Mr Smith: | It is just something you are setting her up to fail, so why. | |

| Mrs Smith: | That would be heart breaking for her and she would stop trying whereas with what she is doing now, at least they are not setting her up to fail. | |

| Mr Smith: | It wouldn’t just be an almost pass/fail. It would be a drastic fail. But it would be good for her to work harder on (school work that) she can handle.Mrs Smith: |

Jodie was achieving significantly below her peer group in reading. She said that it would be easier for her to learn if her homework was not so difficult, and she asked for the work to be matched to her abilities and to have questions she could work on independently:

| Researcher: | So you wouldn’t have any suggestions for them. What do teachers do that makes it harder for you to learn? | |

| Jodie: | Probably the homework sheets. | |

| Researcher: | Too much homework? | |

| Jodie: | Yeah. | |

| Researcher: | Why is it hard for you to do homework? | |

| Jodie: | They put questions on it that you don’t know. |

Transient students are described in the research literature at being at risk of academic failure (Kariuki & Nash, 1999; Lee, 2001; Sanderson, 2003; Shafft, 2003). In a review of North American research Hartman (2002) described the “long-term effects of high mobility” (p. 229) that included lower achievement levels, slower academic pacing, and reduced likelihood of high school completion. In the present study, two students nearing school leaving age talked about their desire to leave school as soon as they could, despite their parents’ and teachers’ encouragement to stay on and gain academic qualifications. A parent of one of these students commented that it was important for schools to have high expectations for students in this regard, and to ensure that students understand the real disadvantages associated with leaving school at an early age. It is also important to note that some students in the present study were doing well academically and were achieving at or above the level of their peers. It was clear that some families had a resilience that allowed them to transcend the potential problems associated with transience, but it is noteworthy that these particular families did not face the additional burden of living in poverty. This issue of resilience in transient families may be one that is worthy of future research.

Transient students have difficulty making friends, are bullied and are at risk of becoming “an outcast”

Friendships at school

Friendships and peer support in school are described in the literature as essential for students’ social and emotional development, and for their learning (Alton-Lee, 2003; Alton-Lee & Nuthall, 1992; Bayliss, 1995; Bukowski et al., 1996; George & Browne, 2000; Heiman, 2000). Morris (2002) emphasises that students’ interactions need to be understood as central to their school lives and to learning:

There is little recognition in current policy and practice that, from children’s point of view, friendship is the main motivation for going to school and that difficulties with making and maintaining friendships are a key barrier to getting the most out of education. (p. 13)

Social connections enrich students’ private worlds by providing practical and emotional support; offering a means for relaxation, fun and enjoyment; and providing opportunities to voice frustrations, to self-disclose and encounter new experiences (Fraser, 2002; Heiman, 2000).

In this study, variations were found in transient students’ social experiences at school. Three students had no “real” friends and felt they did not belong at Wooldon. The issues were serious enough for the community of practice to make a decision that these students would be a priority for intervention through the school’s action-research project.

Six of the thirteen students interviewed described being part of a social group at school. Alec, for example, said that “pretty much everyone” in his Year 9 class were his friends, with one particular friend considered to be “my mate”. Out of school, Alec spent much of his time doing odd jobs in the community and like some of the other transient students, he rarely spent time outside school with friends because “. . . pretty much everyone lives out of town here . . . on farms and stuff”. Both Alec and another student, Tania, enjoyed sports and named friends with whom they played sports at school. Alec loved rugby and in winter would play in the same team as his friends, often driving out of the district to attend games. Alec’s love of sports meant that much of his break time at school was spent playing sport with “pretty much all the Year 9 boys”, and with an adult sports and physical education facilitator employed by the school.

Alec’s two siblings, Kate and Jodie, also had friends at school. Kate said she got on well with the other three girls in her Year 11 class, and that she had friends out of school. She also stayed in touch with friends from her previous school:

| Researcher: | Have you got like a best friend would you say? | |

| Kate: | No, not really, no, I treat all my friends the same so | |

| Researcher: | What sort of things do you like doing together? | |

| Kate: | Um, we talk, and just hang out and party. I don’t know, just do a lot of things really, walk around and talk and hang. | |

| Researcher: | Okay, what do you do during the break times at school. | |

| Kate: | Just hang out with friends. | |

| Researcher: | And what about at lunch time here, what sort of things do you do at lunch times. | |

| Kate: | Sometimes we play basketball or rugby or touch or we just talk again, other times I go on the computer so I can talk to my friends in the city. |

Sarah, in Year 4, said that the best thing about school was her friends, and she described active break times at school playing games with her peers. The only difficulties she had encountered involved maintaining friendships when new students arrived at school:

| Researcher: | You said that some kids were here before you and you were here before some other kids, is that important in terms of your friendship? | |

| Sarah: | Yes sometimes they steal my friends off me and they are being mean to me and it is like | |

| Researcher: | When you say they, is that the kids who have been here longer than you. | |

| Sarah: | The new kids. | |

| Researcher: | The new kids, right. . . . Do you worry that your friends might be taken away by the new kids? | |

| Sarah: | Yeah | |

| Researcher: | Does it work like that at other schools too? | |

| Sarah: | No, only at this school. |

Three students described feeling “different” and having no friends. Two of these students, Anna and Inga, had diagnoses of mild intellectual disability. Inga (aged 12) named Anna as her only friend at school, noting that Anna was older and in a different class. Other students in the school were “younger” and Inga said that she was not allowed to play with them because of the school rules. Anna felt that she was not part of her peer group, because she was not interested in parties and alcohol. Like Inga, she also preferred to play with younger students. The school had a rule that older students could not play in the junior students’ play area, ensuring that younger students had good and safe access to playground equipment. Unfortunately this rule was misinterpreted by some students and parents in the study, who thought that students were required to have friends their own age. For example, Mrs Scott and her daughter, Britney, said:

| Britney: | I play with my friends of a different age (at my favourite school). It wasn’t allowed, not up here. | |

| Mrs Scott: | Yeah, they have real strict rule about this and I think that’s really bizarre/ I don’t like that rule at all because I had a girl friend from Christchurch come and stay with us for a while and we sent her wee girl to school with Britney and this girl was 6 years old and she was petrified. Because I mean being 6 and going to a school that has got kids up to 7th form, I mean that’s pretty intimidating and Britney was told she was not allowed near her and not allowed to talk to her and that to me is just. . . . Yeah, that’s a really bizarre one. That really blew me away, I mean I can see good points of it in that you must socialise people your own age, but at the same time, how many of us socialise with only people our own age. One of my closest friends is 55 years old. I am only 30, you know. . . . I mean we all have to learn to deal with people of different ages anyway and a good place to do it is at school. We learn it | |

| Britney: | And I am not allowed to play with my friend and she is only a year older than me. |

Anna said she had different interests from her peer group, no friends in her age group, and liked to play with her younger friends. However, she also believed that she was not allowed to do this:

| Researcher: | Can you just tell me again what you think the problems are with friends? Is it just that you are not interested in the same things that some of the other girls are interested in like boys and parties? | |

| Anna: | And parties and drinking and all that stuff. | |

| Researcher: | Right, and that’s not your thing at all. [Nah] Do you have any particular friends here at school? | |

| Anna: | Not really no. . . . I do hang around with the little kids quite a lot but then I get told off because I am too old to be hanging around with them and I think that’s kind of unfair. . . . (The teachers) tell me to go away because I shouldn’t be there and this is the junior school and to go off to your own area where you are supposed to be. | |

| Researcher: | Right, but if you go up to your area the other girls don’t like to play with you or don’t want to spend time with you. That’s difficult isn’t it? [Mm]. So are you enjoying being at Wooldon school. | |

| Anna: | Not really, no. | |

| Researcher: | Who are your friends at school? | |

| Anna: | Don’t really have any. . . . I just hang around with the little kids or my brother and sister will be my friends. . . . (At lunch times) sometimes I walk along by myself.Researcher: |

Aaron, Anna’s younger brother, said that he “got on” with people at school, but did not consider other pupils to be “best friends”. He played sports with some of the boys at break times, but because he lived a long way from school he did not have friends to his home. He conceded that he was a soccer fan in a school where the boys played rugby and described himself as “different”:

| Researcher: | Does your teacher help you to get new friends. | |

| Aaron: | I am different. | |

| Researcher: | Why are you different, what is it that makes you different? | |

| Aaron: | I don’t know. | |

| Researcher: | You don’t know but you feel different from the other kids do you? | |

| Aaron: | Yeah, I try to fit in but it’s not that easy. . . . | |

| Researcher: | You said to me our teacher tries to help you make new friends, what sorts of things does she do? | |

| Aaron: | She tries to help me fit in, tries to—I don’t know, I find it hard to fit in because I don’t like rugby. I find it hard to fit in because I am not like them. |

We asked students whether their teachers helped them to make friends at school, and indeed whether this was expected to be part of the teacher’s role. Students varied in their response to this question, and most commented that teachers did help them to get to know their peers when they first came to Wooldon School. Several students referred to “buddy” approaches set up by their class teacher. Alec and his sister, Kate, both thought the buddy systems were helpful as newcomers:

| Researcher: | When you first came here, did your teacher help you to make friends with the other kids at all. | |

| Alec: | Oh yeah, I suppose so. They had somebody to help me around and show me everything and showed me who everyone was, the teachers, just what every school has done pretty much. | |

| Researcher: | Were you pretty happy with those sorts of things that they did. Did you want them to do any more than that? | |

| Alec: | Nah, its not really their job to anyway. | |

| Researcher: | Okay, do you think that teachers need to be able to help kids with their friendships sometimes? | |

| Alec: | No, I reckon they should just leave it . . . it is going to happen sooner or later. |

Most students said that they appreciated their teacher’s support but felt that it was really up to them though to work out new friendships themselves. Kate said:

I pretty much sorted (friendships) out myself, like (the teacher) kind of put me with one person for the day and then one person gets you the next and the next and you just get the whole group sort of thing. . . . That’s how I got to know everyone else and we just all kind of combined and talked and became friends. . . . There is not a lot (teachers) can do because if you decide you don’t like someone, you decide you don’t like them and they can’t really tell you, ‘Oh you have to be friends with so and so’. So it just makes more trouble and harder probably really. . . .

She was aware that some students had no friends, and suggested that while teachers might be able to intervene to help in this area, they could only be expected to do so much, and that having friends at school involved individual responsibility:

There is about three kids in my class that no one actually likes—I don’t have any problem with them, I talk to them but I am not actually friends with them and maybe if something was done about it, though I don’t know what, they would probably have more friends. . . . I don’t know what they can do because they kind of keep to themselves, they don’t sort of get out and get involved and if they got out and got involved and kind of stop making up excuses they might actually have more friends, so kind of they have got to help themselves for others to help them.

In contrast, Anna, who struggled to have friends, felt that her teachers had not helped her with this aspect of her school life, and she did not feel confident that they would be able to provide the support she needed:

| Researcher: | You have been telling me you have got quite a few issues with friends like you don’t feel as though you have got a group of friends at all. Do any of your teachers help you to get new friends. | |

| Anna: | No, not really. | |

| Researcher: | None of them have tried to set you up with a buddy or do they help you to work in groups with other kids and that kind of thing? You know like in class, do you ever get to work in groups with other kids or do you just mostly work on your own. | |

| Anna: | Mostly I work on my own. Michael is doing the same stuff as me in English and science. | |

| Researcher: | Right, what would you like the teachers to do around the friendship thing, would you like the teachers to help you to make friends with the other kids? | |

| Anna: | No, because I just think they are pretty useless.Researcher: |

Parents generally agreed that teachers could not force friendships, but they did need to support students’ social life at school, and be aware of their particular experiences resulting from transience. One parent said:

Probably a bit more (focus) on the social side of things because like my daughter . . . has always had difficulties in making friends and with us moving she always seems to just get a friend and then we end up moving. That just sort of keeping an eye on that so that she is not just a loner because for the first couple of months at Wooldon School, she was following my son all around the school all day long. I know that’s probably just as much our responsibility but I am not there during the day at school so I can’t see that. So it is just really keeping an eye on them to make sure that they are fitting in and they are not getting bullied or pushed away.

Mrs Jones also recognised that aspects of Inga’s impairments could present further challenges for teachers wanting to encourage friendships at school:

| Mrs Jones: | ODD, yeah she was diagnosed with ADHD, ODD and borderline mental retardation. . . . | |

| Researcher: | Has that affected her through friendships or school relationships? | |

| Mrs Jones: | Definitely her friends because she tends to be bossy—would you call it bossy? Probably even to the point of bullying, dominant . . . she hasn’t really got to the point of physical, like actually hitting her friends and that. But the verbal abuse is probably just as bad and is quite foul and disgusting for a child of her age. She could teach us a word or two.: |

Some parents stated that supporting friendships was also the role of the family and other community members. One parent said:

Well there’s a girl at school and my daughter said, ‘She is strange mum.’ And I said ‘You have got to give people a go. . . . She might be quite a nice girl for all you know’. And um she was quite a nice girl. And I think, parents need to communicate a lot better with their kids. Like I am straight with my kids and plenty of parents in Wooldon can communicate with their kids to give people a chance . . . to find out what they are like.

Teachers’ beliefs were mixed when it came to their views about their role in the promotion of friendships for students in their classrooms. It was common for teachers to feel that “they could only do so much”, and a few teachers attributed a lack of friendships to transient students’ personalities. The research literature encourages teachers to be alert to students’ social experiences at school. Teachers need to develop an understanding of the features of students’ social relationships because these can provide them with a framework for making good decisions about supporting their students’ social lives (Cushing & Kennedy, 2003).

In this study, teachers were aware of some variations in students’ social experiences as a result of age with one teacher suggesting that older students may experience greater difficulties with friendships:

There is not that shyness as much at that younger level as there is when they get older. I mean certainly in the teenage years that’s really important for them to be able to feel comfortable with meeting new people and trying to fit in.

The teachers also explained that secondary students at Wooldon, who did not go to boarding school became even closer, or ‘tight knit’, and developed their own specific mores and norms. For example, one teacher said:

There is a core group of kids who have been Wooldon kids all their lives basically and they are a quite happy go lucky bunch. And they are willing to accept anyone that conforms to their mores or norms. If you sit outside that, then it can become very difficult, very quick.

Gender was considered to be less influential, with teachers agreeing that for girls and boys, sport was popular and involvement in this promoted the development of social relationships at Wooldon School.

Bullying

Most of the students in the study referred to bullying both at school and on the way to and from school. Kate was one of the few who said that she had not encountered bullying at Wooldon School because usually “it gets sorted out because they go and talk to everyone sometimes because it is so small and you can’t really avoid everyone and they get told to get over it. And they get over it and they are talking the next day”. Bullying had been a problem for her in other schools she had attended and had involved “your hair colour, simple stupid things and boys”.

Inga said that getting bullied and having no friends were the worst things about school. She was bullied by one girl in particular and by some of the boys who called her names. She said:

| Inga: | I don’t want to do netball if Claire is around. . . . she beats me up and stuff…. she’s like bigger in the waist and taller. . . . She still calls me names and stuff but I don’t care. Names don’t hurt and I don’t really care if she tries to beat me up either as long as she doesn’t give me a black eye or anything, so that’s okay | |

| Researcher: | So the teachers don’t know about it, does anything ever happen at school or do the teachers know about it do you think? | |

| Inga: | I don’t know. | |

| Researcher: | Do things happen at school (to stop bullying)? | |

| Inga: | No not really. |

Britney (aged 10) also said that bullying was one of the things she hated about school, but that with time things had improved:

Um, one of the things that I hate about school is bullies. And how people like write things like ‘I hate you’ on other people’s belongings. And that happened to me last year and this year. . . . they don’t like to give new people a chance. And they were like that with me but once I had been here for a while it was like ‘Oh she is okay’ and they were being my friends

One parent described how her child was bullied on the school bus and how she had taken matters into her own hands by going on to the bus and making an “announcement” about the issue:

Let’s face it kids can be the nastiest pieces of work. My daughter has had a hard time on the bus. . . . I mean (called) ‘slut’ and all this. . . . by (older) kids. . . . I mean ‘nice’. I think the school has a lot to do with this. They don’t really back up. Like as far as I am concerned, they condoned bullying because nothing was ever really said. No punishment was ever dealt out. . I mean I expected firm discipline over this. I really did, and it got to the point where I was dragging her out of bed, ‘Get up and go to school’, she wasn’t wanting to go. That was hard, because she knew what she was getting on the bus for. . . . I (got on the bus) and threatened them.

One student felt that school was characterised by “a lot of bullying” and said that in response he was capable of behaving “in an unsocial manner” himself. He was aware of the school’s antibullying procedures but did not think they worked very well:

Ah the first step is um, report to the teacher, walk away, then report to the teacher, um, that’s step one, and then there’s step two and then step three and step four. That’s primary school and here (in Year 7), you just get a detention.

Another student said that older students picked on her and teased her “because I have got big teeth and I have got short hair and I look like a boy”. She usually dealt with it by telling them to go away and would also report to the teachers, although her perception was that “they don’t really punish the kids, they just let them get away with it”. A younger primary age student also said she was teased a lot about her physical appearance: