1. Introduction

The Success for All project sought to examine the ways in which nonlecture teaching helps or hinders Māori student and Pasifika student success in preparing for or completing degree-level studies. Good practice was to be identified. This report is the final in a series of detailed technical reports from UniServices prepared by the Success for All research team.

Purpose

The purpose of the Success for All research was four-fold:

- identify international best practice in nonlecture teaching and learning in university settings

- deliver high-quality research on the nature of nonlecture teaching and learning practices that help or hinder Māori and Pasifika student success in preparing for or completing degree-level study

- identify factors in nonlecture teaching and learning that help and hinder Māori and Pasifika student success

- produce practical programmes for tertiary institutions on how to identify what helps and hinders Māori and Pasifika student success in degree-level studies, and how to develop effective programmes in nonlecture settings to harness strengths and address barriers. The emphasis was to be on the successful development of partnerships between educators, and research that was inclusive of Māori and Pasifika expertise.

The research questions that emerged from the research project purpose fell into two core questions and two associated questions.

Core questions

The two core questions were:

- What teaching practices in nonlecture contexts help or hinder Māori and Pasifika success in degree-level study?

- What changes does research in this area suggest are needed to teaching and university practices in order to best support Māori and Pasifika success in degree-level studies?

Associated questions

The two associated questions were:

- Can such changes have an impact on what students say about what teaching practices in nonlecture contexts help or hinder Māori and Pasifika success in degree-level study?

- What does “success” mean in predegree and degree-level study—from Māori and Pasifika perspectives?

Findings would contribute to understanding how to best teach and organise teaching to ensure best possible success for Māori and Pasifika in degree-level studies. The challenge was twofold: First, “success” in degree-level studies had yet to be understood from the perspective of Māori and Pasifika learners. Second, while evidence had been gathered about lecture-based learning in higher education, little was known about nonlecture teaching activities (activities with less than 50 students) that complement traditional en masse teaching, and their effect on indigenous and minority student success. Without these understandings we cannot be sure that our teaching approaches are delivering success for our students. Success for All was a TLRI-funded University of Auckland multi-academic and service centre research project that attempted to address these challenges, based on extensive interviews with Māori and Pasifika students (using the critical incident technique), and implementing interventions in nonlecture settings, based on the analysis of student accounts of what teaching helped or hindered their success.

Success for All was designed so that researchers and educator-researchers worked together over two years to better understand teaching and learning in nonlecture contexts, use evidence to enhance their practices and influence good practice through the development of the Quality Tertiary Teaching (QTTe) Toolkit of “promising practices” (Airini et al., in press; Parker, 2007).

Situating this research

It is widely recognised that detailed research is needed to uncover the complexities of teaching in university settings. Success for All was a two-year evidence-based project that commenced in January 2007 in four different contexts in a New Zealand university of more than 30,000 students. Of particular concern was understanding what teaching practices in nonlecture contexts help or hinder Māori and Pasifika student success in preparing for or completing degree-level study.

The long-term performance of the university system depends on its ability to teach a broad cross-section of students; adapting to dramatic demographic shifts occurring as a result of social mobility, migration and immigration. Stuart Middleton has argued that the changing demographic in New Zealand is “the largest challenge for higher education” (Middleton, 2008, p. 3). The net effect is that those population groups that have traditionally provided successful students are being replaced by increasing numbers of students “from groups that are traditionally underserved by higher education” (Middleton, 2008, p. 3). This is an issue for both universities and economic growth.

Māori and Pasifika student success in tertiary education is of national strategic relevance. By 2021 more than 25 percent of New Zealand’s population will be Māori or Pasifika because of their higher fertility rates and younger population profile (Department of Labour, 2008). Māori and Pasifika will make an increasing proportion of the eligible workforce in New Zealand, at a time when the median age of the population continues to grow. National trends show there has been an increase in Māori and Pasifika participation in tertiary education since 2005, particularly in lower level programmes and some growth at all levels (Landon, 2007; Middleton, 2008). In general, however, there has been no matching increase in tertiary education outcomes, as indicated by graduation rates (Ministry of Education, 2009). The Government’s tertiary education strategy has prioritised more Māori students enjoying success at higher levels and increasing the number of Pasifika students achieving at higher levels, by 2015 (Ministry of Education, 2010). To achieve these priorities, Government strategy has a number of expectations of universities (Ministry of Education, 2010):

- create learning environments that support progression and completion by a diverse range of students ( p. 15).

- provide “tailored support” (p. 6) for groups of students with low completion rates, such as Pasifika, as this has been identified as likely to be needed in order to achieve national strategic goals in tertiary education.

- implement efficient and high quality provision (p. 18)

- “take responsibility for strengthening Māori education outcomes” (p. 12), improving pastoral and academic support, the learning environment and “teaching practices that are culturally responsive to Māori students” (p. 12 )

- improve “pastoral and academic support, and learning environments” (p.12) for Pasifika students; with a view to progress and achievement in higher levels of study

- “ensure research informs teaching” (p. 7)

- provide “higher quality teaching” (p.13).

The scholarship of teaching in universities goes some way to addressing a gap in the research relating to what university educators do and can do better to help student learning and success. Lee Sulman’s “signature pedagogies” identified teaching modes linked with preparing students for a particular profession (Shulman, 2005). The pedagogies reveal much about the cultures and dispositions of a discipline along with accountabilities to external accrediting professional bodies. The ongoing challenge, however, is understanding how these cultures expressed through signature teaching abilities and competencies are related to outcomes (Poole, Taylor, & Thompson, 2007).

Student voice can help university educators develop a critical understanding of their teaching—its content, effect and complexities. This is something of the honest dialogue Paulo Freire said was vital to education, even where the voices “bear witness to negativity” (Apple, Au, & Gandin, 2009, p. 5). The critical lens in research means seeing educative processes and universities as connected to the larger society; being both about social and individual economic advancement through profession education and the relations of power and in-/equality, transformation and justice that make such advancement complex and often unstable. Education in this sense is the process of “repositioning” (Apple et al., 2009, p. 3). It is a site of action against those processes which reproduce inequality and oppression (Apple, 1995).

When research into teaching respects the voice of the minority students and is founded on critical methodologies of indigenous and minority inquiry, there is a break in the tradition of education research dominated by majority interests (Bishop, 2005). Traditional ways of knowing are disrupted, minority knowledge, voice and experience are privileged (Smith, 2005); and scholars from majority groups learn how to “dismantle, deconstruct, and decolonise” traditional ways of doing research (Denzin & Lincoln, 2008, p. 3).

Through placing Māori and Pasifika student voice and university teaching at the centre, the Success for All research aimed to support success and achievement in higher levels of study, improve the performance of the university system, enable research-informed university teaching and expand understanding of how we might engage in critical research in education.

Project assumptions

Four assumptions underpinned the Success for All research:

Success is more than we think: “Success” includes movement towards and achievement of pass grades or higher, a sense of accomplishment and fulfilling personally important goals and participation in ways that provide opportunities for a student to explore and sustain their holistic growth. The concept of “success” is a broad one that links with individual and community notions of potential, effort and achievement over time.

Nonlecture teaching happens and is important: Teaching and learning in degree-level studies happens in mass lectures to 50 or more students, and in complementary nonlecture settings of less than 50 and as small as one-to-one. Adult education teaching can require new kinds of relationships between educator and learning, and new attitudes to teaching that maximise learning in nonlecture settings.

Professional development happens best through partnerships for informed practice: Māori students’ and Pasifika students’ success needs professional development that places university educators in nonconfrontational situations where, by means of engaging in an ongoing and supportive environment with authentic experiences of others, they can critically reflect on their own theorising and its effect on Māori students’ and Pasifika students’ success. In this project, researchers and university educators worked in partnership to better understand and describe good teaching.

Good teaching is helped by university staff understanding their students: Māori and Pasifika peoples are distinct population groups with both overlapping and unique educational priorities. Research needs to recognise that Māori and Pasifika peoples take different routes into university education, with different attributes and issues, at both the individual student and group levels.

This project recognised that there is diversity both within and between Māori and Pasifika.

2. How the project was conducted

Project phases

The Success for All project was conducted in three phases:

- Phase 1 (October–December 2007): In the first phase of the Success for All project, we carried out interviews to record incidents of helpful/hindering teaching in four university sites (the Centre, and Faculties 1, 2 and 3—see below for more detail).

- Phase 2 (June–September 2008): The second phase comprised interventions in each of the four sites to enhance teaching based on the data from the Phase 1 interviews. Without this we cannot be sure that our teaching approaches are delivering success for our students.

- Phase 3 (October–December 2008): In the third phase, we carried out a second set of interviews, again to record incidents of helpful/hindering teaching and see if there was any difference in what was reported compared with the Phase 1 interviews. Without this we cannot be sure that our teaching approaches are delivering success for our students.

Data collection sites

The range of initiatives that provided data for this research gave a rare opportunity for in-depth teaching studies in university settings. This adds to the existing (and limited) knowledge on what quality teaching is in nonlecture contexts, and what “success” means in predegree and degree-level study —from Māori, and Pasifika perspectives.

Data were collected at the following four sites in a single university setting:

- The Centre: These data related to careers guidance and learning activities in university careers education. Evidence suggests that quality careers education can positively influence student success through enhanced motivation and sense of purpose in their studies. A feature of the Centre was that the staff were in contact with students from across the university; and while Māori and Pasifika were present amongst the student clients, staffing at the Centre had limited, if any, Māori and Pasifika expertise to draw upon.

- Faculty 1: These data related to teaching and learning practices in intensive academic support provided by specialists in Pasifika academic support, with one or more Pasifika students; and pastoral and academic mentoring with one Pasifika student or a small group of Pasifika students.

- Faculty 2: These data related to teaching and learning practices in foundation education focused on ensuring that Māori and Pasifika students are successful within a predegree-level qualification (the Certificate in Health Sciences)[1] that prepares students for degree-level studies in the health professions. Pastoral and academic support practices associated with preparing Māori and Pasifika students for success included peer support, tutoring and mentoring at both an individual and group level.

- Faculty 3: These data related to teaching and learning to improve academic outcomes for Māori and Pasifika students in studio and performance core papers. Māori and Pasifika students described experiences in these papers in architecture and planning (studio), fine arts (studio), music (performance) and dance (performance) in Faculty 3. Although pass rates were good for Māori and Pasifika Faculty 3 students when compared to lecture-based majors, achievement was markedly lower when compared to other cultural and ethnic groups within the faculty.

Research methodology

A key distinguishing element in this project was the integration of kaupapa Māori research and Pasifika research methodologies and analytical frameworks. As a result, the project’s focus was not on blaming students, and identifying changes students need to make, but rather on workforce development and organisational change; the project asked, ‘What more can we, from within universities, do to enable our Māori and Pasifika students to fulfil their potential?’

Māori research protocols

Kaupapa Māori research is now a well-established academic discipline and research methodology (see, for example, Smith, 1999). Kaupapa Māori research locates Māori at the centre of inquiry. It has of necessity an understanding of the social, economic, political and systemic influences on expanding or limiting Māori outcomes and is able to use a wide variety of research methods as tools (Curtis, 2007).

Pasifika research protocols

Pasifika research is concerned with the wellbeing and empowerment of Pasifika peoples within New Zealand (Anae, Coxon, Mara, Wendt-Samu, & Finau, 2001; Health Research Council, 2004). Fundamental to Pasifika research is an acknowledgement of the tangata whenua status of Māori and an affirmation of the teina-tuākana (kinship with certain roles) relationship of Pasifika and Māori within the Aotearoa New Zealand context; and ancient whānaungatanga (extended family relationship), of tuākana-teina within the Pacific region (Health Research Council, 2004). Ethnic-specific differences within the grouping “Pasifika” are respected, along with the central importance of principled relationships to all ethical research practice.

What practices were used to support Māori and Pasifika research protocols?

The research team developed explicit, shared practices aligned with each of the stages of the research project.

In the design of the research project, four practices were applied. There was explicit commitment to Māori and Pasifika research methodology in all documentation (expression of interest, funding proposal, ethics application). Researchers with Māori and Pasifika expertise were included in the research team. Māori and Pasifika team members were included at every level of decision making. An additional benefit of this approach was expressed in our third practice, that of growing Māori and Pasifika researchers—both at emerging and active stages.[2] Finally, the group agreed to a set of project principles from the outset to guide practices, including publication protocols.

Once the research project started, five further practices were put into action. First there was open access to all project information (including finances) and second there was opportunity for involvement in project planning and implementation. Most significantly, the “Give Way Rule” was developed. This rule was applied during the analysis of transcripts, particularly when the project team discussed the categorisation of critical incidents from Māori or Pasifika participants. We anticipated there would be times when we would not reach consensus. Where this happened we would note the range of views in the discussion, and then “give way” to the researchers who held the Māori or Pasifika expertise, depending on the ethnicity of the participant. This was a highly active and engaged process in which we would discuss all perspectives as we endeavoured to reach consensus, and even challenge the viewpoints of the researcher(s) who had cultural affinity with the participant. The purpose of such discussions was to ensure the analysis was “trustworthy” meaning that it could be justified according to the evidence from the interviews. Fourth, only Māori and Pasifika interviewers were recruited and trained to work with Māori or Pasifika participants. Finally, participants were provided with the opportunity to be interviewed in te reo Māori and Pacific nation languages.

Report writing and dissemination was shaped to support project commitment to Māori and Pasifika research protocols. First, we have agreed that project members with Māori and Pasifika expertise and ethnicity lead the writing and presentations. Second, a project publication advisory group comprising project members with Māori and Pasifika expertise has been established to receive, approve and monitor requests for use of project data for publications and dissemination.

Research method

Critical Incident Technique

As an established form[3] of narrative inquiry, the Critical Incident Technique is used in this project to reveal and chronicle the lived experience of Māori and Pasifika students preparing for or completing degree-level studies. As Bishop and Glynn (1999) have shown, narrative inquiry provides a means for higher levels of authenticity and accuracy in the representation of Māori and Pasifika student experiences through being grounded in a participatory design. The students are able to “talk their truths rather than present the ‘official’ versions” (Bishop, 1998; Stucki, Kahu, Jenkins, Bruce-Ferguson, & Kane, 2004). We wanted to pursue such “truths” in the university context and so also chose a narrative inquiry research method.

The Critical Incident Technique is a form of interview research in which participants provide descriptive accounts of events that facilitated or hindered a particular aim. As conceptualised originally, a critical incident is one that makes a significant contribution to an activity or phenomenon (Flanagan, 1954). The critical incident is a significant occurrence with outcomes. The research technique facilitates the identification of these incidents by a respondent. The resultant student “stories” are collaboratively grouped by similarity into categories that can encompass the events and that can guide the co-construction of professional development initiatives and the Quality Tertiary Teaching (QTTe) Toolkit of promising practices.

Participants were asked: Can you describe a time when the teaching and learning practices at “X” (that is, careers advice (the Centre), academic support (Faculty 1), predegree studies (Faculty 2), studio and performance (Faculty 3)), has helped (or hindered) your success in degree-level studies?

Critical incident analysis

A complete incident story was taken to be made up of three parts: trigger (the source of the incident), associated action and outcome. The identification of each component part facilitated the grouping of the incidents into “categories” of incidents that appeared similar. Each identified incident met the following criteria: Is there a trigger for the incident; an associated action; and an outcome? Can the story be stated with reasonable completeness? Was there an outcome bearing on the aim of the study?

Consistent with the Critical Incident Technique, each category was checked for trustworthiness. This happened both formatively (in the development of the categories) and summatively (at the finalisation of the categories). The research team undertook the scrutinising process collaboratively and independently, The following questions tested the soundness and trustworthiness of the categories:

- Can the researchers and research groups working independently of each other use the categories in a consistent way? y Are the categories comprehensive?

- To what extent and in what ways are the categories consistent with previous research on best practice in nonlecture teaching in university settings?

- Where we don’t have consensus on the category, what is the range of views in the discussion, and what is the category name we will “give way” to, depending on the ethnicity of the participant, and the evidence provided by the researchers with relevant expertise?

Participants and incidents

In total, the project interviewed 92 participants and analysed more than 1,900 incidents where Māori and Pasifika students described times when the teaching approach had helped or hindered their success in degree-level studies. As shown in Table 1, 26 percent of all participants were Māori, and 74 percent Pasifika. Participation by ethnicity was affected by the Pasifika-only focus of Faculty 1. Even when this was taken into account and Faculty 1 participants removed from calculations, Pasifika participation in this study remained higher (64 percent of participants, excluding Faculty 1) than Māori participation (36 percent of participants, excluding Faculty 1). This is despite actual numbers of Māori and Pasifika students in the Centre and the faculties being similar.

| Ethnicity | Centre |

Faculty 1 | Faculty 2 | Faculty 3 | Total | Total Māori |

Total Pasifika |

% Māori | Pasifika | ||||

| M | P | M | P | M | P | M | P | ||||||

| Phase 1 | 1 | 7 | 0 | 16 | 4 | 9 | 7 | 9 | 53 | 12 | 41 | 23 | 77 |

| Phase 3 | 1 | 5 | 0 | 10 | 7 | 8 | 4 | 4 | 39 | 12 | 27 | 31 | 69 |

| Total | 2 | 12 | 0 | 26 | 11 | 17 | 11 | 13 | 92 | 24 | 68 | 26 | 74 |

Between four and 24 categories of helpful or hindering teaching practices were identified in each of the project sites of university teaching. Each category was moderated within each project group (through each project group reaching a consensus on category identification and description) and discussed within the project team as a whole, with some amendments made as a result.

| Success for All | 15-May-09 |

||||

| Participants |

Incidents |

Categories |

Subcategories |

Av. no. of incidents |

|

| Phase 1 | |||||

| The Centre | 8 | 71 | 3 | 8 | |

| Faculty 1 | 16 | 518 | 7 | 22 | |

| Faculty 2 | 13 | 247 | 11 | 18 | |

| Faculty 3 | 16 | 87 | 15 | 31 | |

|

Subtotal

|

53 |

923 |

36 |

79 | 17 |

| Phase 3 | |||||

| The Centre | 6 | 278 | 4 | 25 | |

| Faculty 1 | 10 | 81 | 5 | 13 | |

| Faculty 2 | 15 | 551 | 10 | 18 | |

| Faculty 3 | 8 | 119 | 24 | 87 | |

|

Subtotal

|

39 |

1,029 |

43 | 143 | 26 |

|

Total

|

92 |

1,952 |

22 | ||

3. Summary of findings

The following section summarises the main findings from the project. The first part covers general findings across all sites and the final part lists some site-specific findings. More detailed information about the interventions and presentation of the QTTe Toolkit are presented in later sections.

Teaching for university student success

Good university teaching is a combination of practices that help holistic and academic success; however, there is evidence that educators who focus on students achieving a pass (or higher) grade are viewed as the most helpful and most effective. Such a focus will combine generic skills in teaching with helping learners to be both independent and interdependent, and successful in university settings and culturally strong.

Professional development

Effective workforce development occurs where there is an ongoing relationship between teaching staff and researchers, a positive environment that esteems the work and importance of the university educators’ collective (individual and organisational) effort for student success, and evidence of ways students perceive that teaching can help or hinder their success.

University educators want explicit information on how their teaching helps or hinders the success of their Māori and Pasifika students. They have views that can contribute to enhanced practice, professional development and organisational change aimed at Māori and Pasifika student success.

There is a need for induction and professional development for university educators of Māori and Pasifika students.

Nonlecture teaching

Quality tertiary teaching in nonlecture settings can be described

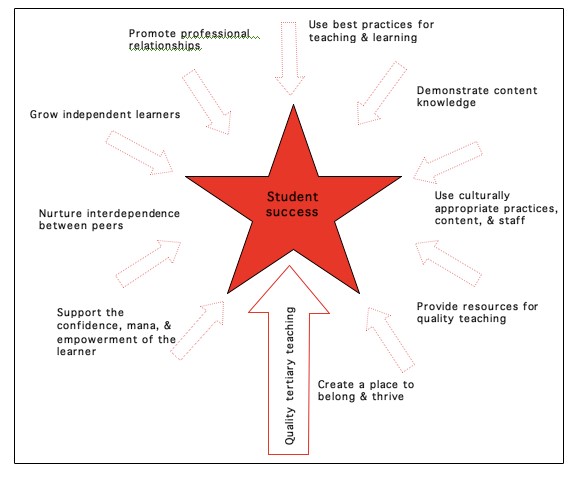

The project collected about 1,900 unique accounts of times where Māori and Pasifika students reported the teaching has helped or hindered their success in degree-level studies. From Phase 1 we developed a profile of promising practices for each of the four sites for teaching, plus some overarching themes. This was revisited and refined following the analysis of Phase 3 findings. The resulting QTTE Toolkit of nine promising practices is illustrated in Figure 1 in Section 5 and described later in this report (see Section 5).

Nonlecture teaching is influential

Students can detail ways in which teaching in smaller contexts (less than 50 students) has helped or hindered their success in university studies. They have distinct views of good practice in nonlecture teaching; for example, they want educators who make sure the students understand class material before moving on to further material, as well as clarity about assignments, challenging academic work in lessons that promote learning, not “wasting time”, and teaching practices that develop students’ independence as learners.

Nonlecture teaching across the university has shared and unique features

What students report as good practice in nonlecture teaching can vary across university settings. The accounts from Māori and Pasifika students suggest that quality university teaching will reflect both unique contexts of study and shared approaches to teaching. The shared elements make up a QTTe Toolkit of promising practices from the Success for All research (see Figure 1, Section 5).

Interventions can help student success

There is evidence that the Success for All teaching interventions positively influenced teachers and students. Teachers had an increased student focus and engagement in a critique of their teaching practices. Students amended their views of what is good practice in nonlecture teaching, and the perceptions of potential for success held by those in student cohorts turned from negative to positive. The interventions are discussed separately in Section 4.

University staff understanding their students

Culture matters

Findings from this project support the view that there is a need to use culturally appropriate, nonracist teaching approaches aimed at supporting academic success. Some university educators were reported as using practices that contribute to students internalising racism. Students spoke of not being worthy to be at university, being reliant upon God (or others) to help them succeed and failing to “represent” (their communities) well enough as students. Alternatively, students described practices where their cultural pride and mana were included positively in classes or activities and, as a result, strengthened. Such practices were identified as helping success in university studies. University teaching practices that perpetuate ongoing colonisation/racism of indigenous and Pasifika rights and potential were rejected by students as hindering their success (Curtis, Townsend, Savage, & Airini, 2009). A key to educators working effectively with Māori and Pasifika students is having a nonblaming approach towards students, in which the focus is on what changes the university (as educators and as an organisation) can make to support student success.

Responding to Māori and Pasifika diversity matters

Students from each population group commented on factors affecting their success being different from those in other population groups. There is evidence that Māori and Pasifika student success is helped when university educators are both proficient in generically effective practices and responsive to the unique learner dimensions of Māori and Pasifika students. Greater understanding of differential practices and goals for either Māori or Pasifika students is needed to ensure most effective teaching practices occur.

Language matters

Educators use language that helps or hinders student success. Helpful language is inclusive (“we”, “us”, “our”), and not exclusive (“they”, “them”) (see also Alton-Lee, 2002). In some cases (notably, with Pasifika students) university educators who were bilingual were identified as particularly effective. These educators were able to converse with the students in their heritage language, increasing understanding of new academic concepts. Good university educators ensure that being bilingual is not an impediment to success.

Professional relationships matter

The dual dimensions of positive professional relations and being responsive to the attributes and resources/experiences of students were identified as being characteristic of good teachers. From this strongly supportive, empathetic, rigorous and academically challenging base, students saw themselves as being set up for success in their studies, risk taking in learning and critical engagement.

Some site-specific findings

In addition, we noted the following site-specific findings. That they were not able to be generalised across the project’s four sites was of interest. Marshall’s (1985) early work on qualitative research methods describes a criteria for assessing the trustworthiness of qualitative research. We were reassured by the emergence of several findings that were distinct for particular sites as this suggested that we did not subsume all the unique features of each site into something homogeneous. Secondly, these site-specific findings suggested to us that it could be worthwhile to explore aspects of each site individually, through further research:

- There are some differences in the views of Māori and Pasifika students of helpful and hindering teaching practices; and differences across disciplines and work contexts.

- Faculty 1 (which had Pasifika participants only) highlighted the importance of good practice nurturing the lagona.

- Judgements about good teaching need to be made over more than one year. One reason for this is that there are substantial effects associated with individual educators, and cohorts.

- It is important to examine how qualitative evidence from this project aligns with quantitative data about success in courses.

- Educators have consistent and coherent approaches to their teaching practices, whether or not they are helpful or hindering.

4. The Success for All interventions: Changes to teaching and university practices to support Māori and Pasifika success in degree-level studies

This section discusses in more detail the interventions referred to in the previous section. The three generic areas on which the interventions focused are described, followed by an account of the interventions undertaken in each of the four research groups. This section closes with a consideration of whether interventions can influence student views on what teaching practices help or hinder success. In total this section provides information in response to the Success for All research question: What changes does research in this area suggest are needed to teaching and university practices in order to best support Māori and Pasifika success in degree-level studies?

Three areas of intervention

The interventions undertaken in Phase 2 answered two research questions: firstly about changes the research in Phase 1 suggested were needed to teaching and university practices in order to best support Māori and Pasifika success in degree-level studies; and secondly whether such changes can have an effect on what students say about which teaching practices in nonlecture contexts help or hinder Māori and Pasifika success in degree-level study.

In general, the interventions in Success for All occurred in three broad areas: staff and teaching; students and learning; and organisational practices and planning. Respective priorities determined which of the three areas were focused on in any of the project groups. For example, in response to Phase 1 data, the Centre’s intervention aimed at increasing awareness of the services it provides, and greater resourcing of services for Māori and Pasifika students. Consequently the Centre focused on increasing staff expertise for working with Māori and Pasifika students, and raising awareness of the Centre and how it can help support success through participating in university student gatherings, and a success-focused poster series of Māori and Pasifika role models. Faculty 1’s focus was on increased success by Pasifika students in that faculty. Their interventions included staff training outside the research team, continuation and promotion of practices being used by the Pasifika academic support team and, at an organisational level, use of the research findings to inform the development of faculty planning and budgets.

The interventions, implemented in response to the Phase 1 data, in each of the four project sites are described below.

The Centre’s interventions

The Centre’s interventions aimed to amend organisational practices and resources to better support Māori and Pasifika students through increased awareness of and increase participation in the services available through the Centre’s career services.

Staff and teaching

Interventions related to staff and teaching included team training on the Treaty of Waitangi and training session to advise and update staff of the Success for All research aims and preliminary findings.

Students and learning

Posters were created that celebrated Māori and Pasifika success and provided resources to encourage and inspire Māori and Pasifika students and their whānau, support them in career planning and underpin students’ retention and success in education and their transition to work. To provide resources for Māori and Pasifika whānau in their own languages, all of the Māori posters were translated into te reo Māori and all of the Pasifika role models’ posters were translated into the different Pacific languages. The project was launched and the posters blessed at the university marae and fale in a unique event that honoured the role models in culturally relevant ways. The posters were distributed throughout the university and into schools and workplaces.

Organisational practices and planning

Marketing of services at the Centre

Presentations were made to intending students in the year preceding their studies, and during student orientation. The aim was to make information about the Centre and its services memorable, entertaining and informative.

Informal marketing and promotion of the services at the Centre

Informal marketing was undertaken through an increased presence in university activities (such as participation in university-based kapa haka group practices), profiling the services during informal networking and advertising at the student hostel.

Personnel

A Māori careers consultant and Pasifika careers consultant were appointed. These appointments provided a “familiar face” for Māori and Pasifika students, to encourage their use of the Centre’s services as well as contacts for employers wanting to target Māori and Pasifika students for work experience, internships or a career within their organisation.

Faculty 1 interventions

Faculty 1’s interventions aimed to address matters raised by the Success for All Phase 1 research, to support Pasifika students to be successful in the Faculty 1 environment. Through the Phase 1 findings, the research team from Faculty 1 further developed an earlier theory underpinning their teaching and learning approaches with Pasifika students: the theory of success. According to this theory, all Pasifika students have the potential to succeed. The role of the university educator is to work with that potential, and to enable the student to pursue their success with confidence in themselves, independent skills and awareness of their networks to support. In this way, the theory is an idea of the university educator and institution providing an environment and experiences that “just add water” to the seed of potential that is in every Pasifika student.

Staff and teaching

As partners in the research project, the Success for All Faculty 1 team members integrated their increased awareness of successful teaching strategies into their contact with students. Professional development was supported through talanoa/discussion sessions on the research and findings, and sharing of times when they as educators put into practice the helpful strategies described by participants in Phase 1. Collaborative planning followed for a staff seminar on the research and findings, working with a small group of volunteer lecturers from outside the Faculty 1 Success for All team.

Students and learning

The Faculty 1 team actively sought to raise student awareness and use of Phase 1 success learning strategies in the QTTe Toolkit through initiatives such as QTTe Toolkit resources and handouts to be used in sessions and independently, and discussing the success learning strategies with students during small-group and one-to-one sessions.

Organisational practices and planning

Quality assurance

The findings were included in quality assurance processes, as indicators for assessing the effectiveness of the practices in Faculty 1’s services.

Annual and semester planning

Formal planning included initiatives and the allocation of resources consistent with the Phase 1 findings; for example, preparation of QTTe Toolkit resources for students and professional development for staff.

Location of service

The relocation of the Faculty 1 Success for All group to a more visible, positive site was explored.

Other interventions

Other interventions were ongoing and dynamic, rather than timetabled. They happened as part of the day-to-day encounters between staff and students. The research data became an explicit part of the language and practices of the Faculty 1 Success for All group. Finding that the research participants valued their practices and having evidence of their effectiveness was of importance to the staff. The research findings were reflective of their practices as university educators and in turn became part of the ongoing life of the practices. As partners in the research, the staff had been immersed in the participants’ transcripts. They found themselves able to name good practices and provide stories to include in their formal and informal time with students. Overall there was an increased awareness amongst the staff of what students perceived to be helpful or hindering practices in the Pasifika student success services in Faculty 1. This influenced how staff and students interacted, student awareness of helpful/hindering practices and increased the esteem within the staff themselves of their current practices.

Faculty 2 interventions

The interventions in Faculty 2 aimed to address issues of concern raised by the research findings highlighting the need to create Certificate in Health Science (CertHSc) students who are independent learners so that they will be successful in the OLY1 (“Overlapping Year 1”: the first year of degree-level studies for students who have completed the CertHSc) environment.

Staff and teaching

Presentation of research findings

All CertHSc staff were invited to attend a presentation of the research findings and a discussion on the proposed intervention. Two sessions were held for course co-ordinators and tutors before the start of Semester 2 in 2008.

Reduced staff “availability” in Semester 2

Students were encouraged to communicate (email/phone) with academic staff to book appointments within these office hours in the first instance or if they would like extra time with staff outside of the office hours. This required CertHSc teaching staff to also defer students to these office hours when requests for additional help were received and to actively reduce their oncall availability.

Reduced pastoral support in Semester 2

In conjunction with reducing availability of teaching staff, pastoral support was provided via the MAPAS[4] Co-ordinator who also had reduced on-call availability and aimed to make students more proactive in their help-seeking behaviour. Pastoral support was readily available; however, students were expected to initiate their engagement with the MAPAS Co-ordinator regarding any personal issues that required support.

Students and learning

Orientation

A Semester 2 re-orientation was put in place to outline to the students how Semester 2 would be different from Semester 1 (i.e., office hours, encouraging independent learning by the students). This included a cohort lunch on the first day of the semester with all CertHSc staff available to give a brief introduction to their Semester 2 course and the timetable in general.

Three-week intensive introduction

This initiative was begun in Semester 1 (immediately following completion of Phase 1 analysis) and continued in Semester 2. Students were divided into groups and mentored by an academic staff member through the first three (or more) weeks. Issues covered in this intervention included reviewing how the students are coping with the workload/new office hours and encouraging navigation via email/phone to request help during office hours (general promotion of the need for them to be independent learners this semester in preparation for OLY1.[5]

Academic 1:1 meetings with students

Each student was offered a 1:1 interview with an academic staff member to review their results from Semester 1, set goals for the next semester (i.e., pass all papers, improve grade point average, move from B+ average to A+ average and so on).

Planning for Semester 1 2009

There was an early introduction of communication and professionalism, teaching students to communicate their issues/problems effectively through multiple media; that is, how to email a lecturer/tutor so they can understand the student’s issue and respond accordingly. Planning included encouraging independent learning skills such as how to create study groups, time management and coping skills.

Organisational changes: CertHSc programme structure

Creation of set office hours in CertHSc timetable

In the second semester in 2008, set office hours were inserted into the timetable for CertHSc teaching staff to be available to address student questions/concerns on a regular/weekly basis.

Experiencing a degree lecture (Semester 1 2009)

It was recognised that there was the potential for the class to experience a large degree-level lecture, experience taking notes and explore issues about being in that environment and so on (to be a component within a CertHSc course).

Other interventions

Other interventions were ongoing, rather than timetabled, and included general changes such as how staff and students interact, student expectations of staff, identifying differences between expectations of workload/difficulty of CertHSc-level study and first-year university courses, as well as multiple approaches to encourage independent learning.

Faculty 3 interventions

The focal point of Faculty 3’s involvement in the Success for All research was its Māori and Pasifika students. The research was viewed as a cycle in which the Māori and Pasifika students are the source of the data and the research ends with a quality-assured studio-based learning environment for Māori and Pasifika students. In this way, the cycle is a tuākana-teina model in practice. The aim for Faculty 3’s interventions was to enhance teaching and learning in the studio environment in order to raise Māori and Pasifika student achievement rates to at least equal those of other cultural and ethnic groups. Faculty 3 developed and adopted a theory of maramatanga (illumination). This was founded on a commitment to transferring models of engagement so that teaching and learning is not about delivery of information, but creating an environment that allows the student to deliver.

Staff and teaching

Guidelines for best practice in the studio environment for Faculty 3 tutors

Tutors active in the Faculty 3 studio disciplines are often artist practitioners who have rarely received formal training in studio pedagogy, and have little in the way of evidence-based research to support their teaching. This intervention focused on providing a framework of best practice models identified by Faculty 3 Māori and Pasifika students as having helped them to succeed. The Faculty 3 intervention also included information on teaching practice that has hindered Faculty 3 students’ success.

Living in two worlds

Faculty 3 had few Māori or Pasifika tutors. Student narratives identified lack of tutor understanding about what Māori and Pasifika peoples valued and therefore what external influences affected their academic success. Using the student narratives as interventions, Faculty 3 tutors were introduced to the cultural complexities of living in two worlds.

Dynamic, organic integration of Phase 1 findings

The Phase 1 data gathered by the Faculty 3 team was seen to be “weaving” through the faculty in a fluid and holistic way. Narratives were used by the team at an organisational level to provide culturally appropriate perspectives on Māori and Pasifika student achievement. Team members used their own studios to implement models developed from the narrative categories and transform discipline-appropriate models gathered from cross-discipline data.

Organisational changes and planning: Tuākana[6]

The Success for All data gathered in the faculty identified peer interaction and cultural networking as the categories with the highest incidents of success. The Tuākana mentoring programme increased its activities and visibility in 2008 and deliberately increased the number of Pasifika mentors, so that the mentorship grew to 50 percent Māori and 50 percent Pasifika. In 2009, the narratives were used in Tuākana training, and mentors were encouraged to collaborate with studio tutors. The following modifications were planned:

- development of a Tuākana-operated, faculty-wide database to track students’ progress through their degrees

- implementation of Tuākana-tutor office hours for each Faculty 3 programme y a Faculty 3 Tuākana Research Assistants’ Workshop (delivered in conjunction with the university’s Student Learning Centre): This trained high-achieving or promising Māori and Pasifika students as research assistants using kaupapa Māori and Pasifika research methodologies. The workshop “rewarded” students by identifying their potential, highlighting their achievements within the research culture of the faculty and providing them with the skills necessary to succeed in postgraduate studies

- the use of incidents and categories from the research to inform faculty and departmental planning to support student success.

Can interventions influence student views on what teaching practices help or hinder success?

There is some evidence the interventions changed the teaching and learning environments to such an extent that students adjusted their views of what teaching practices help their success. Changes were apparent between the types of incidents that dominated in Phase 1 and Phase 3. By Phase 3 the order had changed for what mattered most to the students:

- Readiness then teaching: In Phase 1, what mattered was being ready as students for university study. In Phase 3, what also mattered was good teaching and learning.

- Holistic approaches then pragmatics: In Phase 1, students emphasised teaching approaches that were holistic, supporting both the academic and affective, cultural and pastoral aspects of being a learner. In Phase 3, the incidents also emphasised the ways in which teaching was helpful when practical (e.g., providing academic literacy skills), while still retaining culturally appropriate and specific practices.

On reflection, in the period after the interventions it was apparent that some interventions might not be immediately realised. Critical factors affecting realisation included the breadth and depth of interventions, whether the focus was on teaching, students or organisational changes. A key challenge is to continue the resourcing of interventions long enough to bring about the needed changes to support student success. Sustained change may mean seeking policies and strategic objectives explicit for Māori and Pasifika needs, and policy-based funding.

5. The QTTe Toolkit: Promising teaching practices for Māori and Pasifika success in degree-level study

This section discusses the development of the QTTe Toolkit of promising practices, based on the findings from the research project. The toolkit responds to the Success for All research question: What teaching practices in nonlecture contexts help or hinder Māori and Pasifika success in degree-level study?

As explained in the previous sections, four research sites were established to answer questions about good university teaching practice with Māori and Pasifika students for achieving success in preparing for or undertaking degree-level studies.

In-depth analyses of the critical incident interviews were completed, with checks undertaken to test the trustworthiness of the analysis. These checks were consistent with Critical Incident Technique, as well as kaupapa Māori and Pasifika research methodologies.

Five general hypotheses were developed from evidence gathered in Phase 1, namely:

- pursue best practice

- demonstrate knowledge

- use culturally appropriate practices, content and staff

- support the confidence, mana and empowerment of the learner

- grow independent learners.

The hypotheses were tested and evaluated through the Phase 2 interventions and subsequent Phase 3 interviews at each of the project’s research sites. This resulted in a refinement of the initial set of practices, further practices being added and the development of the nine-point QTTe Toolkit of promising practices (see Figure 1):

- use best practices for teaching and learning

- demonstrate content knowledge

- use culturally appropriate practices, content and staff

- support the confidence, mana and empowerment of the learner

- grow independent learners

- nurture interdependence between peers

- promote professional relationships

- provide resources for quality teaching

- create a place to belong and thrive.

Figure 1 QTTe Toolkit of promising practices

The examination of evidence did not mean the research sites were compared directly; rather the data from each contributed to this emerging model of quality university teaching in nonlecture settings. Individual and collective attributes were linked to the original set of hypotheses. The “emergent” model of promising practices is used to propose answers to the research question: What teaching practices in nonlecture contexts help or hinder Māori and Pasifika success in degree-level study? An explanation of each practice follows.

Use best practices for teaching and learning

Quality university teaching uses the best known practices focused on student success (including social outcomes) and facilitates high levels of outcomes for Māori and Pasifika students. Such educators understand learning in that particular area of study; are flexible; actively encourage and scaffold student learning; and do not unnecessarily frustrate students. Participants in this research were able to identify practices perceived to help or hinder the development of student knowledge, to provide a learning environment or to support student success.

Examples:

(Helpful)

Trigger: You know, like [referring to the lecturer] class and like, you know, has all these little different ways of, instead of reading a book. Action: He’ll like cut out little bits of pieces of paper where you have to sort of organise them together. So it sort of makes you have to read it in order to putting them there and it feels like that, those, you could do the exact same thing just by reading the book, you know, or, and little tricks like that. Outcome:

It’s like it makes it fun and it gets you up and you’re doing things.

(Hindering)

Trigger: You have to just learn about artists that have been dead for a couple of centuries. Action: Most of the courses normally are like two hours long and two hours of sitting down watching videos is, the lights dimmed, it’s gonna help you go to sleep … I mean not that it’s just watching video but I always need to be up and doing things all the time. Most of the time we do it so I wouldn’t wanna say it’s really, really bad, you know … that’s just their teaching style. Outcome: Just sitting there listening can be quite boring, uninteresting … I just don’t take it in sometimes and not learning.

(Hindering)

Trigger: I don’t like some of the tutorials. How some of the teachers teach in tutorials. Action: He’s like not talkative. He doesn’t explain that well. When I ask him a question he’ll be like ‘That’s just how it is’ or he won’t go in depth like most lecturers and teachers. Outcome: And he’ll just tell us … explain … expect us to understand. And it sux because you’re just sitting in there knowing … wasting your time.

Demonstrate content knowledge

The technical and personal knowledge that an educator has of the area they are teaching can help student success (if the knowledge is strong) or hinder student success (if the knowledge is weak). Participants referred to the way in which the educator’s knowledge encouraged confidence as a student; that they believed it was possible to do well in a course; and that they were enabled to develop their own knowledge in the area being studied.

Example:

(Helpful)

Trigger: I remember one time the tutor everyone was really quiet and he was trying to teach us, go through the lecture with us. Action: So what he does was he went through what each one meant, how they related to each other and how they make each other work. Yeah and he went through that whole process and he made sure that we understood before we moved on so if you understood that, we moved on and as we moved on he gradually built on what we knew previously. Outcome: In that 45 minutes I knew three-quarters of that one paper.

Use culturally appropriate practices, content and staff

This research showed that Māori and Pasifika students perceived their success in studies to be linked to experiences in which university educators facilitated learning through creating effective links between university studies and culture. Diversity is valued. Similarly, ineffective links were unhelpful and a barrier to success.

Examples:

(Helpful)

Trigger: You know I’d rather have a Pacific Island person critique my work than a Päkehä one to be honest, you know; Action: Like at least they’ve got a sense of what I’m on about, even if it’s not exactly, even if they don’t really understand Māori things, they’ve got an idea of something other than Päkehä culture. And actually we were, everyone was really excited in the second half of the year because the two, there’s these two new Asian tutors in Digital Media. One is Chinese and I don’t know if the other one is Chinese or not but they’re both Asian, and one is an older man and he just has that old, wise, Chinese look about him. Outcome: And everyone, even the Päkehä students, were really excited because you’re getting someone who’s coming in who’s got another perspective other than the Kiwi, New Zealand, Päkehä perspective coming and looking at your work, and that’s what you want. So just a bit of diversity, it doesn’t have to be a Māori person, just someone who has an understanding of culture other than mainstream Päkehä understanding.

(Helpful)

Trigger: Well we had a cultural paper and it was the time where we, it was a weekend, it was for assessments but we slept over at the marae, the university one. Action: The purpose of that was to educate us about Māori and Pacific Island culture, we were discussing the traditional aspects of our past people kind of thing. Outcome: It was fun, like being part of MAPAS, that was probably the weekend where we actually strongly identified ourselves with our culture.

(Hindering)

Trigger: [Being taught by a particular lecturer] Action: Without really realising it … I think [the lecturer] thought he/she was doing the best for us, but coming from a British educational background (which doesn’t work well necessarily), um, you know, [with] New Zealand, Māori, Pacific Island students, because it is foreign. Oh, so they are bringing all these ideas, all these ways of teaching, all these pedagogies that don’t suit well … Outcome: … the way that [the lecturer] taught, like; it was already decided like what we were going to learn, rather than letting that happen in the moment and within the experience of the class.

Support the confidence, mana and empowerment of the learner

The research indicated that student success grows where teaching practices motivate students, and respect and affirm student identity and intellect. High expectations operate in alliance with quality teaching practices and a focus on student achievement.

Example:

(Hindering)

Trigger: Cause Māori people and Pacific people are quite protective I suppose of their culture or whatever, or their way of expressing culture. Action: The fact that I was shot down in such a brutal way [in a studio crit] so many times when I was just simply trying to illustrate these things that are normal to me, was quite difficult. Outcome: I mean it will lead to me being unsure of myself and my beliefs. It made me question myself and what I was trying to achieve because they were all questioning me and so it just led (or [sic]) to this whole (unclear) confusion for me, that restricted me in more ways than just university.

Grow independent learners

A commitment to teach in ways that develop indepence is a commitment to student success. The research showed that independence can be developed through specific and relevant feedback, a planned approach to students’ academic skill development, confidence building through progressively challenging studies and/or students’ strong sense of involvement in goal setting, targeted and scheduled intensive academic support, opportunities for critical thinking and selfregulation. A further research-based characteristic of independent learners was that they remained in touch with others, and were often motivated by those others—whether friends, family or communities. Quality university teaching supports “independence”, not “isolation”.

Example:

(Helpful)

Trigger: I don’t know of practices as such but I think I think of um a very important thing is that like our tutors and like our lecturers within our course tend to kind of have a lot of faith in us like they actually want us to succeed. Action: Like it’s not like school where they just want you to pass so they can look good you know, and like they make it clear that if you need help you can go to anyone you want. Outcome: So I think I really just kind of have a balance between like supporting us in giving us our own individual sort of way of doing things.

Nurture interdependence between peers

Research-based university teaching practices create environments that encourage collaborative, peer interaction supportive of academic success. Group work (in pairs and larger) happens to support the learning and success for all. Students help each other to succeed in their studies.

Example:

(Helpful)

Trigger: There was another paper that we did in the first semester that was the history of western music so that was a more writing based paper like we did a lot of essays and that kind of stuff. And one of the assignments was a group assignment. Action: You could choose a recording, they gave to you a list of recordings to choose from and it ranged from like Bach to Michael Jackson and that kind of stuff … We had to go on to Google docs or Google groups or something and we also had to start a forum on Cecil and like yeah, have a discussion with the members of our group and we had to each pose a question and each pose an answer to one of those questions just to get us all. Outcome: I just like working with other people and cos sometimes if I do something myself I’m not sure what other people will think about it so if I’m like working on something with someone else then I just feel a bit more secure (unclear) confident that I’m on the right track … I was really happy with my mark and then cos it was group work but then you had to do your individual essays so it was, yeah, an individual mark as well.

Promote professional relationships

Quality university teaching supports success through maintaining a clear delineation between educator and learner. The university educator accepts and promotes understanding of their role as educator. For some this means a role comprising both leadership and service to students.

Friendship is not helpful for student success; being approachable and attentive though, are.

Example:

(Helpful)

Trigger: Well most of the teachers are really like approachable um oh I think all of them are actually. Action: They’re really yeah like bend over backwards for us if we want something. Oh this was last semester anyway. They really help us with like office hours they’re really helpful. They used to come down and see us instead of us going to them which is what’s happening this semester but I think it was really cool they went out of their way to help us. Outcome: Last semester they were really, really helpful. So they’re trying to not do that so much this semester which is good to try and get us more independent and being able to do stuff by ourselves because that’s how it’ll be next year.

Provide resources for quality teaching

Student success requires resources that support quality teaching. The research identified key resources of educators with relevant cultural and educational expertise, materials and equipment to support the teaching activities within a particular area of study. As a result (and sometimes without using available resources, but simply knowing they are accessible) the students felt increased confidence in their ability to succeed.

Example:

(Helpful)

Trigger: I think it also comes back to support. Action: Cause that’s a huge level of support right there [Faculty 3 research assistant workshop], and the tutors … they all, you could tell they all really care about what you are going to become and who you are and all this kind of thing and that’s really important to me because, especially with, I think with people who are trying to achieve something that’s quite radical perhaps, or evolved or whatever, you need people who believe in you and that’s been a huge issue for me. Outcome: I know that I would be able to seek those people out and I wouldn’t have a problem expressing any worries to them or, and I know that they’d be able to understand as well.

Create a place to belong and thrive

The research showed that Māori and Pasifika student success is associated with having a place to gather together informally and formally, to study and interact. Such spaces created havens in which minority culture, language and identity could be the norm, and learning, support and success could occur through the lens of culture, language and identity. Without space, the possibility to succeed was undermined and students felt stressed, isolated and lacking in confidence.

Examples:

(Helpful)

Trigger: Yes the CertHSc room. Action: Well for me just having the CertHSc room is always somewhere to go like you know and be surrounded by your friends, your peers, like people you feel comfortable with, like there’s always the library but I always find I need to talk or read my work out loud, something you can’t do in the library. Outcome: So the CertHSc room is always good like there’s tables and chairs in there to study on and there’s also computers so you’ve got nothing to worry about, you can just go in there and just do your thing.

(Helpful)

Trigger: [Going to the Centre]. Action: I would just describe the whole experience that I had here [in the Centre facility] as the uplifting bit, every time I spoke to someone I was really lucky … when you get encouragement like I did … Outcome: … you get quite excited … It was just uplifting and helped my spirits and that’s all part of the bigger picture … it was more of a spiritual thing more than anything else.

6. Implications: What does this mean for teaching in universities?

The general and specific summaries of findings, presented in Section 3, contain implications for universities. These fall into three major groupings: (a) implications for the development and use of evidence for improving teaching and learning practices in universities; (b) implications of the Success for All research; and (c) implications for the development of good practice in nonlecture settings in universities. The following gives some examples of the implications in each of these three groups.

Implications for the development and use of evidence for improving teaching practices in universities

This research has highlighted benefits that can come from collecting evidence of how the teaching practices used by university departments, faculties and service groups help or hinder student success. This suggests a need for resourcing to support evidence-based university teaching: for example, for workforce development programmes, and access to expertise in teaching skills relevant for Māori and Pasifika student success.

It is also apparent, however, that this research, while enabling student voice to express what helps or hinders success would benefit from a complementary study of quantitative evidence about Māori, Pasifika and other students’ success in degree-level studies; and how improved teaching practices affect student achievement.

Implications for research into student success in wider tertiary settings

To better understand the common and unique features of good teaching, more research is needed on the features of nonlecture teaching in programmes not currently featured in the Success for All research; of particular interest are those programmes that are more effective with Māori and Pasifika students. This research has focused on nonlecture university settings. Further research could be undertaken at postgraduate level, in lecture settings with groups larger than 50 and in nonuniversity settings such as polytechnics, and industry training.

Wider data are needed in order to understand teaching practices and their effect on student success; in particular, there is a need for both student and educator views on what teaching helps or hinders, along with both qualitative and quantitative data regarding success rates and on factors that affect student learning and success.

Finally, research partnerships between educators and researchers can positively influence university teaching. The concept of research as an evidence-based, professional learning, applied process has been developed through this project. Research that creates a community has been described in earlier work on research in school settings (Airini, 2010). Success for All highlights the relevance of such an approach by university educators (both academic and general staff) in their own university settings. The notion of research as a learning community denotes the interdependence of the research endeavour and the university educator in optimising student success. The Success for All research also indicates how student success is linked to university educators getting close (through research) to student experience and student learning. Finally, through having a team of both academic and general staff involved in educational encounters with students, this research was unusual and nontraditional, yet also practical and real to the actual world of university.

Implications for the development of good practice in nonlecture settings in universities

The development of the QTTe Toolkit of promising practices means helpful practices can now be described in relation to four university teaching contexts. The Success for All research provides university educators with examples of helpful and hindering practices in each of the nine areas on the toolkit, and thereby illustrate the tools-in-action. In addition, the Phase 2 interventions provide examples of what directive actions individuals and organisations might take to improve practices, with the aim of supporting student success. Professional development can be informed by accounts of student experiences in each of those contexts. Finally, the QTTe provides Māori and Pasifika accounts, thereby informing studies into indigenous and minority student experience, while also expanding the general body of knowledge into quality teaching in university education.

This research highlights the important and relevance of evidence-based approaches to university teaching. Research-based information can provide a foundation for good university teaching practices. In addition, without wishing to state the obvious, it is also clear that the identification and advancement of good practice needs university educators willing to develop their practices. The development of good practice is a partnership between research and educator.

In relation to success by all university students, a commitment to locating students, in particular, Māori and Pasifika students, at the centre of good practice initiatives is needed if success for all is to be achieved. Success for all means forgoing equality for equity.

7. Conclusion

The purpose of the Success for All research was to contribute to ongoing, evidence-based and evolving dialogue about university teaching amongst policy makers, educators and researchers that can inform planning and practices, and optimise Māori and Pasifika student success in New Zealand universities. While evidence has been gathered about lecture-based learning in university education, little is known about nonlecture teaching activities that complement traditional en masse teaching and their effect on Māori and Pasifika student success. This report describes findings from the Success for All research investigating what teaching practices in nonlecture contexts help or hinder Māori and Pasifika success in preparing for or completing degree-level study. Two sets of observations can be made at this stage in the research process—one about the research method itself, and the second about the findings.

The research method

Putting Māori and Pasifika realities at the centre of research

The integration of kaupapa Māori research and Pasifika research protocols means explicitly advocating research from Māori and Pasifika realities. As a research method, the Critical Incident Technique was effective in enabling indigenous and minority group perspectives to be elicited. This is important as Success for All is directly connected to Māori and Pasifika philosophies and principles. It assumes the validity of Māori and Pasifika peoples and knowledge; the importance of Māori and Pasifika languages and cultures; and the importance of the pursuit of leadership by Māori and Pasifika peoples for one’s own cultural wellbeing. This is leading to new research processes and new findings.

The concept of “culturally responsive research” is central to the Success for All methodology. This frame rejects notions of “normal” or “culturally neutral” research. Diversity and equity are central to the research endeavour and central to the focus of quality teaching in universities in Aotearoa New Zealand. It is fundamental to the approaches taken to research in New Zealand university education that it honours Articles 2 and 3 of the Treaty of Waitangi, and pursues equitable outcomes for all.

As indicated by Curtis (2007), the traditional positivist approach to research, where dispassionate objectivity is paramount, is not the only “true” way to make sense of the world. Other approaches to research are not only appropriate but desirable and represent valid ways in which one can structure one’s world and hence one’s study of it. The integration of kaupapa Māori research and Pasifika research protocols directly challenges Western notions of what does, and does not, constitute appropriate research. Māori and Pasifika are brought from the margin to the centre; centralising Māori and Pasifika concerns and approaches, so that Māori and Pasifika ways of knowing and, therefore, researching, may be validated.

A key challenge is communicating new findings that are potentially culture- and site-specific. The team is challenged to produce information that can be useful in improving teaching practices by all educators working with indigenous and minority students. At the same time, there may be findings that are particular to Māori and Pasifika realities and interventions. For the Success for All findings to be applied to greatest effect, ways need to be found to communicate culturally embedded findings widely and also to Māori and Pasifika specifically. This research has commented on how to research in culturally responsive and relevant ways for innovative outcomes.

Learning from extracts, themes and linkages

It is difficult to know how well an interview extract can do in communicating the full experience of a student. The reporting of the research requires the cutting of small elements from an overall story. This helps in deriving categories essential to developing professional development programmes. The team’s intention is that this practice is to be continued; the principle being that the extracts are the medium towards improved practice and not the message. What is also apparent, however, is that a single category may not fully describe the nature of the student experience or outcomes. Students link outcomes in one category (such as clarity and action) with outcomes in another (such as independence). The team was interested in ways to communicate overarching themes from individual student interviews, which necessarily means publishing larger sections of the transcript; and the communication of linkages between categories. At times, the interconnections between one part of a student’s interview and others made it difficult to isolate the critical incident. Student accounts of what help and hinder success could be more akin to an orchestral score than a few bars of music from one instrument. A remaining challenge is how to represent these full accounts in research papers.

Working with the generic and contexualised

A particular focus of university teaching has been applied in this research. Our field of study was four areas in which university teaching occurs in one New Zealand university. This means that the discussion in this report is context focused. The context and process of one New Zealand institution’s efforts in university teaching have been described. The nine research-based characteristics of quality teaching derived from this research are generic in that they reflect principles derived from research across a range of university settings. How these apply in practice is, however, dependent on the particular area of study, and the experience, expertise, knowledge and needs of the students in those particular contexts.

What can the findings tell us?

Research to improve university practices and outcomes