Introduction

Health and Physical Education (HPE) in New Zealand primary schools has been dominated by games, sports, fitness, and illness prevention. This narrow and teacher-centred version of HPE has been “nice for some and nasty for others” (Evans & Davies, 2002, p. 17). This project draws on the shared expertise of teachers and researchers to reimagine HPE in ways that support teachers and children to have meaningful experiences, relevant to their diverse backgrounds, needs and interests. In doing so, this project offers a rare glimpse of curricular ideals enacted in practice.

What we learnt together

- Reimagining and enacting innovative approaches to HPE curriculum and pedagogy supports children to:

- Be accepting of others

- feel more confident to participate in a wider range of movement experiences

- Act in health-promoting ways in their interactions with their peers across a range of settings

- Think critically about their worlds.

- To effect meaningful curriculum and pedagogical change in HPE, teachers require space and time to think and reimagine, and to engage in critical dialogue as part of respectful communities of reflective inquiry.

- The teaching as Inquiry process (Ministry of Education, 2007, p. 35) is a valuable tool to help teachers and school communities critically examine the macro and micro influences on HPE practice. This tool assists the reimagining of teaching and learning in ways that support the diverse needs and interests of children.

- Teachers’ inquiries into their practice underline the importance of really knowing students. This includes knowing about students’ diverse needs and interests, and using this knowledge as the premise for inclusive teaching and learning in HPE and other learning areas.

- Planning for learning, and engaging students in the planning process, is valuable. In contrast with planning for activities, planning for learning in HPE is more likely to be deep and meaningful for students in the classroom, at school and beyond the school gates.

- When primary school teachers draw on their existing repertoire of classroom pedagogies, and are willing to explore new pedagogical tools in their planning and teaching, they are ideally positioned to teach HPE for diverse learners.

- Contemporary society’s physical health agendas encourage children to hold narrow and judgemental views on what it means to be healthy and unhealthy. Therefore, it is essential that teaching and learning programmes and wider school policies support children to:

- Value themselves and diverse ways of being

- Critically engage with messages about “health” and bodies

- Act in ways to enhance their own and others’ wellbeing.

- HPE offers unique and often untapped opportunities to address the vision, principles, values and key competencies of The New Zealand Curriculum (Ministry of Education, 2007).

What we recommend

- In a complex and contested health and education environment, it is vital to keep children’s learning and wellbeing at the heart of pedagogical decision-making.

- Schools and their communities provide the space and time for teachers to engage in a process of reflective inquiry that supports them to reimagine HPE in ways that better meet the needs and interests of all learners.

- HPE programmes, like any innovative teaching that is responsive to the needs and interests of learners, should look and feel different in different times and places.

- To sustain student learning in HPE, messages and practices should be consistently enacted in class- and school-wide programmes and policies.

The research

Background

Health and Physical Education (HPE) in Aotearoa New Zealand makes a significant contribution to the wellbeing of students, school and local communities, and the environment (Ministry of Education, 2007). Despite this contribution, there is little research about teaching and learning in HPE in primary school settings, particularly in relation to the diverse needs and interests of contemporary students. This project aimed to create understandings of teaching and learning processes in HPE that support success for diverse learners in the 21st century.

Despite the holistic model of health and wellbeing advocated in The New Zealand Curriculum (Ministry of Education, 2007) and Te Marautanga o Aotearoa (Ministry of Education, 2008), recent public- and school-based health initiatives tend to focus primarily on physical health. Increased concern about children’s obesity levels has meant many of these initiatives are explicitly geared towards trimming the fat off children’s bodies through promoting diet and exercise (Burrows & Wright, 2007; Macdonald, Hay, & Williams, 2008; Rich & Evans, 2009). Multiple corporate organisations are also increasingly reaching into schools, further complicating what is already a complex assemblage of policies, initiatives and practices that schools and teachers are dealing with (Petrie & lisahunter, 2011).

Research highlights that well-meaning health initiatives and policies do not always play out as they are intended (Fullan, 2001). New Zealand-based and international research is increasingly pointing to some of the undesirable effects well-meaning health imperatives can have on the kind of child and nature of learning that is valued in schools (Evans, Rich, Davies, & Allwood, 2008; Leahy, 2009; Rail, 2009). In a context where priorities about childhood obesity prevail, a particularly narrow range of physical capacities and appearances are seemingly valued (Burrows, 2010). This often means that activities associated with fitness and nutrition take centre stage in school HPE programmes. In contrast with meeting the diverse needs of all learners, research suggests that those with the “right” image, body type and disposition to eat and exercise well often receive more “time, space, opportunity, attention and reward, both emotional and material” (Evans & Davies, 2004, p. 9) in schools than those who have different bodies and embrace different health practices.

Finally, studies have shown that HPE has always struggled for legitimacy and “time” in primary schools (Kirk, 1998; Petrie, Jones & McKim, 2007; Petrie, 2008; Stothart, 1974, 1992). This struggle is despite Health and Physical Education in the New Zealand Curriculum (Ministry of Education, 1999) having been internationally recognised as a forward-focused document that embraces a holistic notion of health and affords significant opportunity for innovative and critical pedagogy (Macdonald, 2004; Penney & Harris, 2004). In a “crowded curriculum”, and one where literacy and numeracy are privileged (Key, 2008; Tolley, 2010), it is unsurprising to find that pre- and in-service professional development in the HPE area has been widely regarded as inadequate (Petrie, Jones, & McKim, 2007). Many teachers feel ill-equipped and reluctant to teach HPE (Petrie, 2008).

This project gave teachers and university partners opportunities both to view the wider environment and to focus on practice. First, they could explore ways in which an extraordinarily complex health policy environment contours teaching and learning in HPE. Secondly, they could reflect on what currently constitutes HPE in their particular contexts. Finally, they could consider alternative ways that HPE could be programmed, taught and learned in primary schools in an effort to improve educational outcomes for diverse learners.

Methodology and analysis

Two research questions drove the project.

- What are the characteristics of HPE teaching and learning in primary schools and classrooms?

- How do teachers take up, adapt and deploy innovative approaches in HPE, and with what effects on student learning?

The research took place with four variously experienced teachers drawn from two ethnically diverse schools, one in Hamilton and one in Tauranga. The classes spanned year 3 to year 6. The 2-year duration of the project afforded opportunities for ongoing dialogue and developing respectful relationships among the research team, as well as the chance for the university partners to spend significant periods with teachers and children in their classes.

The overarching methodological approach was focused on building practice through a community of reflective inquiry, where the shared expertise of all participants (teachers and university researchers) was respected. This allowed us to work as partners to co-construct the research, rather than positioning university researchers as “experts”. Across the study we employed a range of research methods, which aligned with the teaching as Inquiry process articled in The New Zealand Curriculum (Ministry of Education, 2007, p. 35).

First, we used ethnographic case studies to glean a detailed picture of the contextual factors which shape teachers’ work. The case studies also gave us a rich understanding of teaching and learning practices, and insights about how curriculum may be reimagined. From this platform for critically reflective inquiry we worked together to co-construct a reimagined version of HPE. Teachers then trialled alternative ways of thinking about and doing HPE in their classes. Here the research approach shifted to teacher-led action research/inquiry, grounded in the community of reflective inquiry. our research process comprised four distinct phases.

Phase one: Building knowledge about current practice

This phase was geared towards developing a situated conception of the macro and micro factors that shape teachers’ curriculum and pedagogical work, and student learning in HPE. This involved auditing the wider local and national health-promotion environment—including analysing newspaper articles over a 3-month period— and developing preliminary case studies of what was going on in the name of HPE in each of the classes and schools.

Phase two: Expanding repertoires and reconstructing practice

Here, phase one findings were shared amongst the research team. This prompted both a critical reflection on the ways children currently understood health and a collaborative reimagining of what HPE that included all learners might be like. Pivotal to this phase was the generation of a shared “ethos” that was to frame all our subsequent work.

Phase three: trying it out and exploring possibilities

The question “what happens to teaching and learning in HPE when innovative approaches for curricula exploration are introduced?” was the focus for phase three. In particular, we explored how innovations might meet the needs of diverse learners, in each of the teacher’s contexts.

Phase four: Extending the learning to the broader community

Phase four focused on how change in practice can be sustained and spread beyond the teachers and classrooms involved in the project to the wider school community and to different school sites. This phase has been extended beyond the length of this TLRI project.

A range of data-gathering strategies were used across each of the four phases. These included:

- Teacher-led classroom learning activities

- A document analysis of school curriculum policy, lesson/unit/long-term plans, student workbooks, information supplied by external organisations that offer HPE-related resources, and print and digital media

- An environmental audit, including visual material displayed, layout of school grounds and buildings, and messages articulated by school leaders, other teachers and the broader school community

- Interviews with teachers and students (individual and focus groups) to explore what teachers and students think and understand about what they are doing in class (or across the school or syndicate)

- Teacher narratives, pictorial representations and diary reflections.

Data were scrutinised for how they related to contemporary curriculum issues and agendas detailed in the background section. underpinning our analysis of data were four key principles. First, we were committed to embracing a notion of shared expertise within our group. Secondly, we did not frame the project with a solution to any particular problem in mind. Thirdly, we regarded teachers work as influenced at the micro level by the relationships between teachers, students and the school context, and at the macro level by wider cultural and political practices. Finally, as in action-research methodologies, the classroom teachers were understood as researchers in their own right, willing and able to make sense of their own experiences and those of their students.

Data generated in each phase were communicated to the wider team to inform the ongoing development of the project. For example, during phase one the university researchers wrote environmental scans and case studies which were then explored by the full research team during reflective discussions. These data and the subsequent dialogue were the springboard for the research team to collaboratively reimagine the nature and practice of HPE in their respective classrooms (phase two). As teachers engaged in the action-research process (phase three) they presented data from their inquiries that were then collaboratively analysed and examined by the full team. To supplement this, second interviews with children and with senior leadership teams were used to examine the effects of this reimagining of HPE on classroom culture and student learning, as well as the wider school community. In each instance, data were discussed and analysed by the full team.

A Shared Ethos“Everybody Counts” was the name of the shared ethos that was co-constructed after we had engaged in a critically reflective inquiry about current practices in phase one. This shared philosophy framed subsequent work across the project and formed the basis for the way HPE curriculum design and pedagogy was re-imagined. Everybody Counts also developed in an iterative way as we built our understandings of it through action research. The key tenets of the Everybody Counts philosophy are that children will:

An expanded version of this ethos can be found at: https://tlri.org.nz/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/1133-EBC-Ethos.pdf |

Major findings and implications

Examining one’s beliefs about HPE is a crucial step when developing programmes that are responsive to children’s needs. Prioritising time to reflect on everyday school and classroom practice and children’s sometimes entrenched ideas can yield opportunities to build a shared philosophy. It is also important to understand what children know, think and feel about HPE currently before trying to do things differently.

Conditions for reflection and innovation

The teaching as Inquiry process outlined in the effective pedagogy section of The New Zealand Curriculum (Ministry of Education, 2007, p. 35) provided a useful tool to help us make sense of current practice and refocus teaching and learning in HPE to better reflect the needs and interests of all learners. To support this process it is necessary to establish conditions that give teachers and researchers the space to engage in reflective dialogue. To reflectively think about—let alone do—innovation requires:

- Time to talk, think, discuss, debate and imagine

- Respectful partnerships where the shared expertise of all members of the school and research community are acknowledged

- Awareness of how our view of teaching and learning is influenced by our own assumptions, values and beliefs, as well as the complexity of the landscapes in which we work

- living with the discomfort of not knowing, and therefore being willing to grapple with, question and dither about what teaching and learning may or may not become.

Knowing your learners

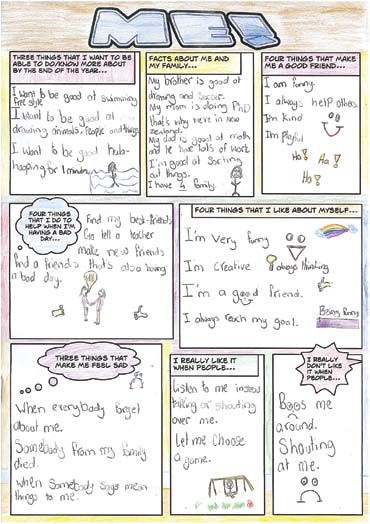

Knowing your learners

Knowing children better, and beyond the superficial, allows teachers to plan for learning that reflects the needs, interests and sensitivities of individual students. When reflecting on their own and others’ practice, teachers found that there was a need to develop learning activities that allowed them get to know more about their students than what is available on their record of learning or from traditional “get to know you” activities such as a “wanted poster”.

To really know and understand learners, it is essential that we make sense of all aspects of their lives including for example, their fears, personal strengths, learning desires, feelings about themselves, things they struggle with, and who they listen and talk to. The image at the right illustrates one of Joel’s strategies he used to really get to know his children.

Meeting the needs of all learners

Teachers’ experiences confirmed that “one-size fits all” programmes of learning were not responsive to the diverse needs and interests of children. Bringing an “Everybody Counts” lens to teaching and learning meant that teachers were continuously reflecting on whose needs and interests were being met in their respective classes. Classroom activities that teachers had previously taken for granted in HPE were reframed and the merits of school-wide practices reassessed (e.g., the cross-country run and packaged health-education resources) with teachers modifying these to make sure they were inclusive of all children.

Children’s ideas and voices have substantially informed the shape and substance of teachers’ work in HPE in this study. In one class, a collaborative consideration of what “being active” meant in their own and others’ lives generated questions about what thinking, people and movement skills would enable them to be active in different contexts. Drawing on this analysis, the children then collectively determined what their specific learning foci would be across a year (e.g., balance, aiming and accuracy, coping with different emotions). Centring children’s views meant that HPE classes looked and felt very different for teachers and children. Health education was woven across the course of the school day—rather than delivered as a series of one-off topics— and was consistently responsive to children’s changing needs. Movement contexts seldom contemplated previously by the teachers were drawn on in response to children’s self-identified learning needs and desires (e.g., dance, circus skills for exploring balance activities).

Using what we already know and do well

Making use of existing pedagogical techniques and exploring new pedagogical tools allowed teachers to practice HPE in innovative and responsive ways. By applying approaches such as scaffolding, differentiated activities, guided questioning, and ensuring every student was engaged in active learning, teachers provided learning opportunities that were challenging, inclusive and safe. A willingness to take risks and explore alternative strategies in HPE provided some useful avenues for teachers to explore complex ideas, grapple with the interpersonal dimensions of health and wellbeing, and challenge taken-for-granted assumptions. These alternative strategies included the use of a thought “experiment” (Stainton Rogers & Stainton Rogers, 1992, p.7) in the form of a large tinfoil robot (Mr Metal made by Shane’s class) and video-based documentary making to examine movement participation.

Making use of existing pedagogical techniques and exploring new pedagogical tools allowed teachers to practice HPE in innovative and responsive ways. By applying approaches such as scaffolding, differentiated activities, guided questioning, and ensuring every student was engaged in active learning, teachers provided learning opportunities that were challenging, inclusive and safe. A willingness to take risks and explore alternative strategies in HPE provided some useful avenues for teachers to explore complex ideas, grapple with the interpersonal dimensions of health and wellbeing, and challenge taken-for-granted assumptions. These alternative strategies included the use of a thought “experiment” (Stainton Rogers & Stainton Rogers, 1992, p.7) in the form of a large tinfoil robot (Mr Metal made by Shane’s class) and video-based documentary making to examine movement participation.

Planning for learning versus planning for activity

Shifts in pedagogy reflected a desire to make sure that learning in HPE was deep and meaningful, as opposed to previous HPE teaching where the surface was scratched and then the focus shifted to the next “topic”. Teachers noted that in contrast with previous planning that had been based on the current activity or topic of choice (e.g. T-Ball, bullying), an Everybody Counts approach to HPE supported them to identify the learning first and then determine what activities would best support students to make progress toward the desired outcome. When teachers and children together recognise what is important for children to learn, teachers can then consider what pedagogical approaches will best support this learning (e.g., teachers may abandon predetermined timeframes that could prevent every child from experiencing success).

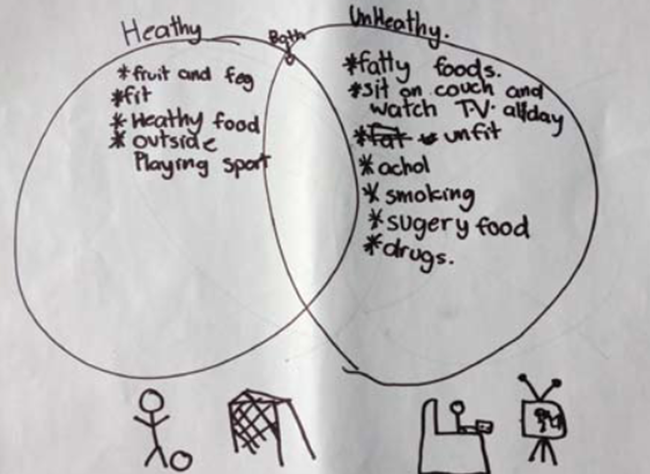

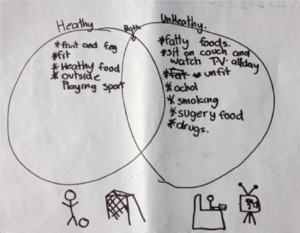

Moving beyond narrow concepts of health

Children’s initial responses to the question “what does it mean to be healthy?” illustrated that they are learning from media, parents, schools and their peers to judge themselves and others based on body shape, dietary choices and engagement in formalised exercise. The example provided demonstrates one approach Jo and Deirdre used to explore students understandings of this issue. The findings from across the classes raised questions such as: What might it be like to be a child in my class/our school who doesn’t really fit these views of being healthy? What am I/we doing that might contribute to my children thinking about being healthy and unhealthy in such narrow ways?

Over the course of the project the teachers increasingly valued HPE programmes and practices that consider the person as a whole being, that see beyond the surface of the body or one’s silhouette, and provide opportunities for students to value themselves and others as members of a diverse society. This requires a conscious effort to question assumptions about what being healthy is and reflection on what role teachers play in reinforcing narrowly conceived perspectives that privilege particular types of bodies and ways of behaving. By explicitly exploring holistic notions of wellbeing, and engaging students (at all levels years 3–6) in critical dialogue about the social, spiritual, mental/ emotional, and physical dimensions of wellbeing, teachers are able to begin supporting students to recognise that health is not based on size, and that it is important to adopt a range of strategies to enhance and maintain holistic wellbeing.

Over the course of the project the teachers increasingly valued HPE programmes and practices that consider the person as a whole being, that see beyond the surface of the body or one’s silhouette, and provide opportunities for students to value themselves and others as members of a diverse society. This requires a conscious effort to question assumptions about what being healthy is and reflection on what role teachers play in reinforcing narrowly conceived perspectives that privilege particular types of bodies and ways of behaving. By explicitly exploring holistic notions of wellbeing, and engaging students (at all levels years 3–6) in critical dialogue about the social, spiritual, mental/ emotional, and physical dimensions of wellbeing, teachers are able to begin supporting students to recognise that health is not based on size, and that it is important to adopt a range of strategies to enhance and maintain holistic wellbeing.

Enhancing learning environments

Learning in HPE can shift class culture. The Everybody Counts ethos created a space where every child felt that they were valued for the diverse talents and capacities they brought to the classroom. When what counts as HPE was broadened beyond bats and balls, running and prescriptive health messages, children felt able to engage with one another and with the subject matter in ways not previously possible. When children accepted that every body was different and that this was “okay”, and when children were encouraged to “live” out the inclusive Everybody Counts philosophy in their everyday interactions with each other and in their day-to-day lives, a ‘ripple’ effect occurred. That is, more respectful, open and caring relationships within the class were developed which, in turn, shaped how they treated one another in playgrounds. Further, an improved class culture influenced children’s attitudes towards, and participation in, other areas of school life. In essence, HPE has become a catalyst for teachers and students thinking and doing things differently. These kinds of outcomes strongly align with those advanced in The New Zealand Curriculum (Ministry of Education, 2007), highlighting the unique and often untapped opportunities HPE offers to address the vision, principles, values and key competencies.

Engagement as activist professionals

An Everybody Counts lens prompted ongoing questioning of what kind of learning about physical activity, health and wellbeing was being promoted, and whether this linked to the philosophical intent of The New Zealand Curriculum (Ministry of Education, 2007). It also generated questions about the kinds of dispositions, abilities, bodies and children that are privileged in different health resources and policies. The teachers’ concern to prioritise student wellbeing and meaningful learning in their practice meant they became discerning consumers of outside providers’ health and physical activity resources. They reshaped, rethought and at times, rejected these if they did not meet learning priorities. Critical reflection on what and who contributes to learning about health and physical education is crucial for both school leaders and teachers.

Sustaining change

Sustainable and responsive HPE practice requires focused attention over time, committed teachers and school communities, and consistent messages. Pedagogical approaches that aligned consistently with the Everybody Counts approach to HPE evolved over time and with prolonged thinking and discussion. Teachers had to contend with their own and other colleagues’ uncertainty and questions about what might arise in and through their process of reimagining HPE. The ongoing support of senior leadership teams in the schools was integral to teachers feeling encouraged to challenge their own and wider school practices, and to sustaining a general climate of critical inquiry. Seeing the Everybody Counts ethos lived and enacted in classroom practice and in the playground particularly sparked the interest of other teaching staff. This raises questions about the most effective ways to support other teachers with the adoption of innovative HPE practices school-wide. Consistent messages and practices across the school enable inclusive and holistic understandings about movement, bodies, health and wellbeing to prevail.

Conclusion

Any teaching innovation will look and feel different in different times and places. Everybody Counts was the shared philosophy that made a difference for this project’s teachers, but it will not necessarily do so for others. What is clear, however, is that teaching as inquiry processes have been pivotal for thinking and doing HPE in ways that meet the diverse needs of children. The capacity to critically reflect on one’s own practice and afford children opportunities to critically engage with taken-for-granted knowledge is pivotal to reimagining HPE in primary schools. Planning for learning rather than activities, designing curriculum around children’s interests and drawing on the vision, principles, values and key competencies embedded in The New Zealand Curriculum (Ministry of Education, 2007) are practices that yield the possibility of equitable outcomes for diverse children.

References

Burrows, L. (2010). Kiwi kids are Weetbix kids: Body matters in childhood. Sport, Education and Society, 15(2), 235–251

Burrows, L., & Wright, J. (2007). Prescribing practices: Shaping healthy children in schools. International Journal of Children’s Rights, 15, 83–98.

Evans, J., & Davies, B. (2002). Theoretical background. In A. Laker (Ed.), The sociology of sport and physical education: An introductory reader (pp. 15–35). London, England: RoutledgeFalmer.

Evans, J., Davies, B., (2004). Pedagogy, symbolic control, identity and health. In J. Evans, B. Davies & J. Wright, (Eds.). Body knowledge and control: Studies in the sociology of physical education and health (pp. 3–18) London, England: Routledge.

Evans, J., Rich, E., Davies, B., & Allwood, R. (2008). Education, eating disorders and obesity discourse: Rat fabrications. London, England: Routledge.

Fullan, M. (2001). The new meaning of educational change (3rd ed.). New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Key, J. (2008). Sport for young Kiwis: A national priority. Retrieved from http://www.national.org.nz/Article.aspx?ArticleID=28149

Kirk, D. (1998). Schooling bodies: School practice and public discourses 1880–1950. London, England: Leicester University Press.

Leahy, D. (2009). ‘Disgusting pedagogies’. In J. Wright & V. Harwood (Eds.), Biopolitics and the ‘obesity epidemic’: governing bodies (pp. 172–182). New York/London: Routledge.

Macdonald, D. (2004). Physical education’s challenge: Choosing the ‘right’ purposes. Proceedings of the 2004 Pre-Olympic Congress, vol. 1, p. 12. Aristotle University of Thessaloniki.

Macdonald, D., Hay, P., & Williams, B. (2008). Should you buy? Neo-liberalism, neo-HPE and your neo-job. Journal of Physical Education New Zealand, 41(3), 6–13.

Ministry of Education. (2007). The New Zealand Curriculum. Wellington, New Zealand: Learning Media.

Ministry of Education. (2008). Te Marautanga o Aotearoa. Wellington, New Zealand: Learning Media.

Penney, D., & Harris, J. (2004). The body and health in policy: Representations and recontextualisation. In J. Evans, B. Davies, & J. Wright (Eds.), Body knowledge and control: Studies in the sociology of physical education and health (pp. 96–111). London, England: Routledge.

Petrie, K., Jones, A., & McKim, A. (2007). Evaluative research on the impacts of professional learning on curricular and co-curricular physical activity in primary school. Wellington, New Zealand: Ministry of Education. Retrieved from http://www.educationcounts.govt.nz/ publications/schooling/25204/25331

Petrie, K. (2008). Physical education in primary schools: Holding on to the past or heading for a different future. Journal of Physical Education New Zealand, 41(3), 67–80.

Petrie, K., & lisahunter. (2011). Primary teachers, policy, and physical education. European Physical Education Review, 17(3), 325–329.

Rail, G. (2009). Canadian youth’s discursive constructions of the body and health. In J. Wright & V. Harwood (Eds.). Biopolitics and the ‘obesity epidemic’: Governing bodies (pp. 141–156). New York/London: Routledge.

Rich, E., & Evans, J. (2009). Performative health in schools: Welfare policy, neoliberalism and social regulation? In J. Wright & V. Harwood (Eds.), Biopolitics and the ‘obesity epidemic’: Governing bodies (pp. 157–171). New York/London: Routledge.

Stainton-Rogers, R. , & Stainton-Rogers, W. (1992) Stories of childhood: Shifting agendas for child concern, Hassocks, England: Harvester Stothart, R. A. (1974). The development of physical education in New Zealand. Auckland, New Zealand: Heinemann Educational Books.

Stothart, R. A. (1992). What is physical education? New Zealand Journal of Health, Physical Education and Recreation, 25(2), 7–9.

Tolley, A. (2010). National standards training for teachers. Retrieved from http://www.beehive.govt.nz/speech/national+standards+training+ trainers