Introduction: Research rationale and aims

In keeping with the spirit, aims, and principles of the Teaching and Learning research Initiative (TLRI) programme, the following whakataukī has guided our research project:

Ma te mahi ka mohio, ma te mahi ka marama, ma te mahi ka matatau.

Through practice comes knowledge, through knowledge comes understanding, through understanding comes expertise.

Our project has been grounded in the realities and complexities of teaching practice, and the fundamental partnership between teachers and their families and communities. Many early childhood settings in Aotearoa New Zealand follow the advice of Te Whāriki (Ministry of Education, 1996) and use children’s interests as a source of curriculum decision making. Earlier New Zealand research found that while teachers intuitively understand the notion of “interests”, a more analytical interpretation of “children’s interests” is required to understand children’s deeper motivations and the influence of their life experiences thus far on the complexity and creativity of their working theories (Hedges, 2007; Hedges, Cullen, & Jordan, 2011; Hedges & Jones, 2012). our project used “funds of knowledge” (González, Moll, & Amanti, 2005; Hedges et al., 2011) and children’s “real questions” (Wells, 1999) or “fundamental inquiries” (Hedges, 2010) as lenses of interpretation within more diverse communities than previous New Zealand research.

Children’s interests and inquiries frequently reveal their working theories as they seek to make meaning in their worlds. working theories are the second major learning outcome identified in Te Whāriki, alongside dispositions. These two learning outcomes are the foci for assessment practices related to Te Whāriki (Carr, 2001; Carr & Lee, 2012). However, research on working theories linked to children’s interests has only recently begun in New Zealand (e.g., Davis & Peters, 2011; Peters & Davis, 2011). researching children’s interests, inquiries, and working theories is fundamental to finding out how children learn and has important implications for early childhood learning environments, curriculum and pedagogy and teacher preparation and professional learning. Children’s continuing inquiry and knowledge construction is dependent on the meaningful responses of the adults in their lives. Therefore this project focused on gaining further insight into teacher practices around children’s interests, inquiries, and working theories.

Research questionsWhat is the nature and content of infants’, toddlers’, and young children’s inquiries and working theories in relation to their everyday lives in their families, communities, and cultures? How might teachers notice, recognise, respond to, record, and revisit infants’, toddlers’, and young children’s interests, inquiries, and working theories in early childhood education? |

Theoretical framings

Recognition of children’s home lives as a strong influence on their learning is central to the sociocultural theories and Māori ways of being, knowing, and doing that underpin Te Whāriki (Ministry of Education, 2009b; Reedy, 2013). Teachers who partner with families can develop the capacity to recognise and utilise children’s family and cultural knowledge in educational settings to connect and enhance children’s learning. Rogoff’s (2003) notion of culture as beliefs, activities, and practices shared in communities that are in continual flux through a process of transformation of participation was adopted in the study. We noted this transformation of participation particularly in relation to New Zealand-born Pasifika families and migrant families who are developing hybrid identities and often supporting children’s development of other languages besides English.

In keeping with current interpretations of Te Whāriki, sociocultural theories and approaches to pedagogy framed the project. These were intent community participation, funds of knowledge, and inquiry-focused learning and teaching.

Intent community participation

Children are enthusiastic to learn when they are motivated by observing and participating in cultural activities (Paradise & Rogoff, 2009; Rogoff, Paradise, Arauz, Correa-Chávez, & Angelillo, 2003). from focused intent community participation, learning is internalised by children, and re-created as opportunities arise. occasions to represent experiences of interest from their communities occur during play in early childhood settings.

Funds of knowledge

As a concept, funds of knowledge aligns with Te Whāriki in that it is a credit-based notion. It acknowledges that households are rich in knowledge and experience. Specifically, Moll, Amanti, Neff, and González (1992) defined funds of knowledge as the bodies of knowledge, including information, skills and strategies, that underlie household functioning, development, and wellbeing. These may include ways of thinking, approaches to learning, and practical skills. Examples might include observing a parent writing a shopping list or reading a recipe. Through participation in these activities, children develop intuitive knowledge of literacy. The pedagogical goal of a funds-of-knowledge approach is to recognise and incorporate children’s, parents’, and community knowledge and expertise in educational settings (see Hensley, 2005; Tenery, 2005). Funds of knowledge is now used to describe everyday knowledge that can be used as a foundation for developing culturally-relevant curricular provision in educational settings.

| Visits to family homes, several months after children join a centre rather than early on, may strengthen relationships. Visits can affirm, clarify, deepen, or raise interesting questions about teachers’ knowledge of children revealed in the centre setting, and ways children’s interests relate to their intent participation in their wider lives. A funds-of-knowledge perspective shifts the balance of power towards the family as the expert while the visiting teacher-researcher presents him or herself as a learner. |

Inquiry-focused learning and teaching

Wells (1999) argued that inquiry learning for children and teachers is most effective when it engages with authentic questions and issues—that is, children’s “real questions” (p. 91)— in ways that involve co-constructing meaningful learning. In previous work adopting Wells’ notion of children’s real questions, Hedges (2007, 2010) interpreted and categorised children’s interests from an adult perspective. These ideas and questions were revisited in this project.

Lindfors (1999) defined an act of inquiry as when “one attempts to elicit another’s help in going beyond his or her own present understanding” (p. ix). Inquiry acts also seek information, confirmation of an idea, explanation of some phenomenon, and/or wonder about something (Bruner, 1986; Lindfors, 1999; Wells, 1999). These acts often involve expressing working theories (Hedges, 2014) and are “simultaneously and inevitably acts of connection, of understanding, of personal expression” (Lindfors, 1999, p. 4). As children absorb information through intent participation and inquire further into aspects of their lives that appear related in some way, working theories likely evolve during inquiry acts as attempts to understand and explain connections between experiences, information, and understandings.

| Inquiry, inquiry acts, and working theories were a focus of the project. We used Hedges and Jones’ (2012) definition of working theories for this project:

Working theories are present from childhood to adulthood. They represent the tentative, evolving ideas and understandings formulated by children (and adults) as they participate in the life of their families, communities, and cultures and engage with others to think, ponder, wonder, and make sense of the world in order to participate more effectively within it. Working theories are the result of cognitive inquiry, developed as children theorise about the world and their experiences. They are also the ongoing means of further cognitive development, because children are able to use their existing (albeit limited) understandings to create a framework for making sense of new experiences and ideas. (p. 36) |

Research design and methods

The study adopted an interpretivist methodology and used qualitative methods. The project partnership between university-based researchers and centre-based teacher–researchers was based on acknowledgement and expectations of shared expertise, a genuine curiosity about the real everyday practices and problems of early childhood teaching and learning, and a mutual commitment to learning from research. In this way, differing expertise could be shared and supported, and links made between research, theory, and practice.

Becoming a teacher-researcher takes time and includes communication with colleagues. The Small Kauri teachers wore high-visibility vests at the beginning of the project to highlight their researcher role. Children’s curiosity was piqued. This was a powerful early example of ways children’s interests can be stimulated by new experiences, and how children draw on their existing experiences to make connections and develop working theories. Children soon theorised, first, that the road workers repairing the road outside the centre were researchers, and, second, that when they wanted to find out about something they ought to wear high-visibility vests too. |

The study involved the following data-generation methods:

- video and audio recordings of children and teachers in everyday teaching and learning interactions • teacher group interviews

- curricular/pedagogical documentation including centre planning materials, wall documentation of projects, and assessment portfolios of children’s learning stories

- reflective and analytic memos

- visits to family homes (interviews) halfway through the project to strengthen relationships and gain deeper insights into the family, community, and cultural contexts that may have influenced children’s interests

- interviews with children

- research team discussions and analysis

- collaborative analysis of data shared with teaching teams for feedback.

Collaborative analysis discussions occurred amongst the research team about children’s expressions of their interests and inquiries and the growing identities that these represented. In this way, consistent with our underlying whakataukī, the five teacher and two academic researchers collaboratively analysed, illuminated, and theorised the complexities of teaching. These interpretations were shared with other teachers in the centres to test their validity.

| The research activities and funds-of-knowledge framework brought on a particular set of challenges for the research team during analysis discussions. While we came from a position of seeing difference as strength, we needed to avoid making assumptions or generalisations about children and families. To address this concern, we considered “cultural repertoires of practice” (Gutiérrez & Rogoff, 2003; Rogoff et al., 2006), where a localised and processual understanding of culture is prioritised. Drawing on Gutiérrez and Rogoff (2003), we use individual examples of children to exemplify the findings and illustrate the value of teachers using theoretical and analytical tools to understand interests, inquiries, and working theories at deeper levels. |

Our partner centres

Small Kauri Early Childhood Education Centre is a privately owned mixed-age-group setting (6 months–school age), situated in Mangere Bridge Village in South Auckland. It is licensed for 37 children (with up to seven aged under 2 years and 30 over 2 years). The centre offers a resource-based, child-centred programme. Children engage in learning through play during sustained interactions with teachers. The turnover of children is very low, with most remaining at the centre until they transition to school. There are usually seven teachers present, six of whom are qualified and registered. Most of the teachers have been employed in the centre for more than 5 years. Children and families were from a diverse range of cultural backgrounds. Most children lived in two-parent families where both parents were in paid employment or one was studying.

Myers Park KiNZ Early Learning Centre is also a mixed-age setting, situated in the central city and managed under the umbrella of the Auckland Kindergarten Association. It is licensed for 50 children (with up to 10 aged under 2 years and 40 over 2 years). The centre has a large, spacious, well-resourced interior and exterior environment. The centre has a high turnover of children as many families are new migrants to New Zealand initially choosing to live in the central city and/or are international students attending university for the academic year only. Most of KiNZ 10 staff with children each day were qualified and registered. There was a 50 percent turnover of staff during the duration of the research. Children who attended represented diverse cultural backgrounds and many did not share a common language until they gained sufficient command of English. Many families lived locally in central city apartments or in homes shared with other relatives to help with the costs of living in a large, metropolitan city. Similarly to Small Kauri, most children lived in two-parent families where both parents were in paid employment or one was studying.

The teacher–researchers were able to build on established positive relationships with children and families to invite their participation and generate data of authentic everyday teaching and learning interactions. Negotiated permissions based on respectful relationships were required throughout the study. The ethical principles of voluntary participation, informed consent, social and cultural sensitivity, and minimising harm were paramount. Approximately 80 children and families and 15 teachers were involved in the project. Teachers undertook 17 family visits and one community visit for 18 children. of the 18 children, two were cousins who lived in the same home, two pairs were siblings, two were visited in their two homes, and one child was visited in a community facility as well as his home. The remaining nine children were visited once in their family home.

The families visited were chosen to represent diversity, using Alton-Lee’s (2003) definition: “Diversity encompasses many characteristics including ethnicity, socio-economic background, home language, gender, special needs, disability, and giftedness” (p. v). families represented in the findings in presentations, publications, and this summary include single-parent, two-parent (mother and father or two mothers) and extended-family households; families with children born in and outside of New Zealand; and families of a range of cultural and ethnic backgrounds, including the hybrid ethnic/cultural identities that represent a growing number of children and families statistically. Boys and girls were selected across the age range of 6 months to 5 years; six were pairs of siblings or cousins who lived in the same household. No children were identified specifically as representing disability or giftedness. Instead, we worked with the image of children in Te Whāriki as confident, competent, capable learners and communicators. Children with special behavioural needs were participants. However, because this research identifies centres, children, and families, for ethical reasons we chose not to report findings about these children publicly. Similarly, while many real names are used in presentations and publications arising from the project, since the ethical principle of credit was offered to acknowledge participation, at times we have chosen to use pseudonyms to be confidential and sensitive.

Findings

Children’s interests, inquiries, and working theories

What is the nature and content of infants’, toddlers’, and young children’s inquiries and working theories in relation to their everyday lives in their families, communities, and cultures?

The findings related to our first research question are reported here in relation to the theoretical tools prominent in the project. These tools assisted teachers to look at curriculum provision more analytically.

Funds of knowledge

Theoretical tool for interpretation of interests and dialogue with families

The construct of funds of knowledge helped teachers to look more deeply into and beyond everyday play events in the centre to make meaningful connections to children’s lives. Showing families video footage was often a stimulus for learning about funds of knowledge. For example, Brooklyn (aged 16 months) was observed rolling a toy car down a wooden ramp and then using his body to repeat the actions of the car. He appeared to be developing early working theories about force, gravity, speed, and spatial concepts. Later that week, footage was captured of him playfully attempting to walk along a large wooden ramp put up for Lebron (aged 4) to ride a bike on. Brooklyn and Lebron showed awareness of safety and each other as they each persisted with their explorations. Brooklyn’s great-grandfather watched this footage with teachers. An in-depth conversation occurred about the family’s frequent trips to the park and the way they supported Brooklyn’s active, sometimes risky, exploration of equipment likely designed primarily for older children. Hence, in his family, Brooklyn had developed skills and dispositions that supported his learning alongside older children.

|

|

Methodological tool

Consistent with previous research (e.g., Tenery, 2005) the teacher-researchers were initially anxious about the visits to families, wondering how they would be received. However, families welcomed the visits as, in most cases, prior good relationships had already been established. The teacher–researchers relaxed and enjoyed this element of data gathering. They used the prepared format and questions/topics for the visit and interview flexibly and informally according to circumstances (see Cooper et al., 2014, for format, questions, and extended findings).

Analytical tool

Teachers often found that they needed to look carefully and deeply at what they saw and discussed with family members during visits to family homes, and subsequently at the centre, in order to make connections to funds of knowledge. Because this form of knowledge is embedded in everyday cultural practices, it is implicit and can be hard for parents to recognise and articulate. Therefore it was often insufficient for teachers to simply ask parents about ways children’s interests might have been stimulated at home, as parents did not always consider their practices significant or unusual. Teachers sometimes needed to engage skilfully in follow-up conversations, ask more probing questions, and/or observe carefully to reveal the funds-of-knowledge influences.

For example, Mia (aged 2) often played with dolls after the birth of her baby sister. one day she transformed the centre bathroom into a place where she bathed and showered her doll in focused and determined ways, ignoring and refusing Bianca’s (teacher) offer of help or alternate equipment.

|

|

|

On first viewing this video footage her mother thought that, as Mia had not been involved directly with bathing her sister, she was not re-enacting this. However, on deeper discussion, with teacher consideration of theories of intent community participation and funds of knowledge, all realised that Mia had observed and participated in the family’s quite particular and specific routines and practices and was indeed re-enacting these with the doll.

The key benefits of teachers learning about children’s and families’ funds of knowledge were that:

Not all teachers need to visit and not all families need to be visited to prompt changes to teacher thinking and practice. Members of both teaching teams reported that, through discussion with colleagues and access to reading the interview transcripts, they had learnt from and benefitted from others undertaking the visits. |

Continuum of interests and inquiries

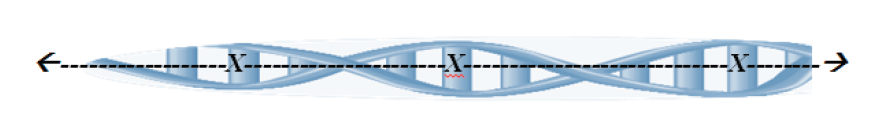

A continuum model from earlier work (Hedges, 2010) was revised (see diagram). This continuum has three points of recognition of children’s interests from surface-level to deeper interpretations. These feed forward and back, circling around and zooming in and out of (Carr et al. 2009) the concept of funds of knowledge. Play remains a vital way in which children demonstrate, re-visit, and extend funds of knowledge-based interests, represented in all points of the continuum.

Children’s funds of knowledge-based interests

activity-based interests—-continuing interests—-fundamental inquiry questions

Notions of spirals and a double helix were used to indicate that these interests are complex, recognisable at all three points, and that sometimes children’s knowledge, thinking, and action may involve “hesitant or backward steps in dealing with discrepant information, theories and experience from time to time” (Hedges, 2014, p. 46).

Activity-based interests

Unstructured play and learning materials (e.g., sand, water, blocks, Lego, playdough, and art resources) can be used for both experimentation with the material itself and to represent children’s interests and understandings. However, by itself, identifying interest in particular “activities” is a somewhat low-level interpretation of children’s interests. Interpretation of interests at this level can mask understanding of what the activity represents in terms of funds of knowledge and/or investigation of deeper interests. A narrow way in which to notice interests and respond to them (i.e., plan further curriculum experiences) is to identify activity-based interests and plan to add further resources.

Continuing interests

At a point further on the continuum were interests that continued over a period of time and often involved children in some early everyday or conceptual learning. This finding is in keeping with Davis and Peters’ (2011) project finding on “islands of interest and expertise” and using these as a focus for working-theory attention and development. Examples of these ongoing interests included children’s interests in the natural, physical, and material worlds—in particular, children’s interests in animals, insects, and the unique physical geography and/ or culture of their part of the country. These interests are among those usefully supported by project work. As children grow and learn, some of these ongoing interests are likely to change, or to alter focus.

For example, over a period of months, Niky (teacher) documented a group of toddlers’ interest in vehicles and ways this interest was encouraged by provision of resources, dialogue, repetition (e.g., reading key books), and trips outside the centre. She also noted that each child had her or his own specific focus and associated working theories within this project.

Fundamental inquiry and “real questions”

Our findings on inquiry have been re-worked as a result of this research project occurring in more diverse communities (see Hedges, 2010, for the original questions). what follows are adult interpretations of children’s “real questions” (Wells, 1999, p. 91) from a team of researchers and teachers who have looked in depth at a range of children’s interests. Most significantly, we recognised that the notion of identity was more central than previously appreciated.

| The fundamental inquiry question was worded in this project as:

How can I build personal, learner, and cultural identities as I participate in interesting, fulfilling, and meaningful activities with my family, community, and culture?

These questions played out differently in the two different contexts but are drawn together in this report. |

How can I build personal, learner, and cultural identities as I participate in interesting, fulfilling, and meaningful activities with my family, community, and culture?

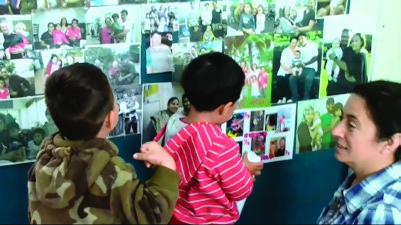

Children’s interests in understanding and negotiating multiple identities were the most notable feature of the project. These interests and the ways they were expressed served to create a sense of personal and shared identities for the children as members of families and wider communities and cultures.

Children’s personal identities (“who are my parents/family?” “what does it mean to be a girl/boy?”), learner identities (“who am I as a learner?” “what learning strategies can I build here?” “How will teachers help me learn?”), and cultural identities (“where do I come from?” “who am I as a member of a family/culture/ community?”), including a shared national identity (“what features do we share?”), merged. These interests and the ways they were expressed served to create a sense of personal, shared, and negotiated identities for the children as members of families and wider communities and cultures.

For example, Hunter and Simeon (aged almost 5 years) shared an interest in working out their personal, learner, family, and cultural identities as they played and sang the national anthems of three countries and negotiated the right words for the haka that the All Blacks undertake before rugby test matches.

|

|

Teachers’ understanding of these interests and children’s families were enhanced by visits to family homes. For example, relationships and understandings were strengthened when Trish and Daniel (teachers) visited Hunter’s home to observe and learn more about valued family practices related to music. over time important knowledge was shared that strengthened Hunter’s identities as a learner and member of his family and cultural community (Cooper, Hedges, Lovatt, & Murphy, 2013).

This fundamental inquiry into exploring and negotiating identities was represented in children’s interests and working theories, particularly through efforts to engage peers and adults in play and dialogue. The fundamental inquiry encompassed several “real questions”. once again, these are worded from an adult interpretation and have been adapted from Hedges (2007, 2010) to reflect the findings of this TLRI project.

What can I do now I am bigger that the older children do?

Children keenly observed the skills and abilities of their older peers and constructed working theories about these to test out in relation to their peers. For example, toddler Chloe keenly watched older children jumping and set herself the task of learning to do so. over several months she practised and persevered until she achieved her goal.

|

|

|

For Cole (aged 4 years), a high turnover of children meant he was constantly practising the skills of friendship making. At one point, Cole used his working theories about size and height of peers and siblings to help him negotiate playing with a group of similarly-aged boys. In the following interaction, Ken’s theorising that height and age were connected was perhaps challenged by Morgan’s height and age.

Cole sits down by Lego with the group already there

| Cole: | … bigger? Morgan is big. See I’m not big, Morgan is big, see Coley? I’m a little bit taller. But Morgan is really taller. |

| Ken: | But my brother is really taller, he’s 7 years old, 7. |

| Morgan: | My mum said that is not taller. |

Cole stands up and goes over to Morgan to measure himself against him.

| Morgan: | I’m bigger. |

| Nevio (stands up): |

Let’s measure me. No! |

Boys all measure themselves one by one against Morgan and Cole. All of the boys are shorter than Morgan.

| Morgan: | I’m bigger. |

| Nevio: | Morgan’s too big. |

| Ken: | And my brother’s tall big, but he’s 7 years old. |

| Cole: | Like him? (points to Morgan) |

What do intelligent, responsible, and caring adults do?

A second theme of children’s fundamental inquiry appeared to involve finding out what it means to be part of a responsible family and community and learning associated funds of knowledge. (The adjectives “intelligent, responsible, and caring” used here are from Berk, 2001). Children were keenly interested in family and adult responsibilities, such as caring for babies, preparing meals, property construction and maintenance, and socialising together.

Children’s play with dolls, where they care for them, adopting the role of a caring adult (parent/grandparent/ teacher), appears a universal theme in children’s play (Rogoff, 2003). one example was Emily (aged 15 months), who was often observed playing with dolls. She sustained her focus on several dolls for more than half an hour in one video recording. She gathered them together carefully and repeatedly placed material over them, and then removed it in a gentle, slow, and caring manner.

In a recorded interview between Trish and Zoe (aged nearly 5) about Zoe’s interests, Zoe revealed current interests, knowledge, and working theories about her imagined future and identities as a responsible adult:

Zoe: I like … playing Mum and Dads … ’Cos what I like about that is I really want to be a Mum when I grow up! And a police officer … ’Cos I’ve been playing with my doll babies a lot and I’ve got good things to look after babies—bottle, foods, and cream and some water and a high chair and a push chair … [Trish asks re: policewoman] Did you know when I went to the swimming pool on Friday I saw two cars parked on the yellow lines and you’re not allowed and I told them off! … And … on Friday, same Friday, we went to fix the windows ’cos they were breaking windows and boys usually break windows instead of knocking on doors and that’s stealing.

How can I make special connections with people I know?

Children’s interest in people seemed to be underpinned by a strong desire to be part of learning through social interactions. Being a member of a family, followed by having relationships with friends that extended into socialising and community activities, was an interest of children’s that, in turn, often determined which interests and inquiries would be followed in a self-initiated and/or shared manner.

Rosa and Angie, both aged 3 years, were good friends as their families spent time together as well as them both attending KiNZ. one of Angie’s mothers worked as a manager for a power company and travelled frequently, including to Wellington, to work. In one video clip, the collage activity of making a crown appeared to be a secondary consideration to a conversation in which Rosa and Angie grappled with working theories about the multiple meanings of the word “go” in terms of stage shows, adult work, and trips involving aeroplanes. Knowing each other well and working to maintain their friendship through helping each other at the activity was a strong motivator to resolving the issues that arose.

How can I make and communicate meaning?

The ability to communicate verbally and non-verbally was a powerful stimulus to interests and inquiry. Dan (toddler) enjoyed playing a repetitive game of hiding and retrieving a pair of oven gloves with Trish. His nonverbal expressions invited Trish into his game and extended the time spent together. Expansion of children’s verbal language enabled adults to respond meaningfully to children’s ongoing interests and inquiries indicated initially through their intent participation.

|

|

Isabella and Zoe (both aged nearly 5) were interested in their identities as a Cambodian/Samoan/New Zealander (Isabella) and in having Hungarian heritage (Zoe). Together they invented their own secret language as a symbol of their friendship that also helped exclude other children and adults when they didn’t want to play with them.

|

|

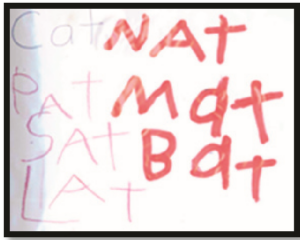

Zoe also enjoyed learning to read and write. Here are items from her learning portfolio:

|

|

How can I understand the world I live in?

Exploration and understanding of the natural, physical, and material worlds was a strong interest across the age groups. Children’s inquiries seemed to pursue questions such as: How are these animals like me? How does this work? What are the features of the world I live in?

The problem-solving function of working theories in relation to real work was evident in 3-year-old Melody and Nyatefe’s efforts to put a tap back in the right place when it came loose in the centre playground.

Some children engaged in exploration of humans’ and animals’ hearts, blood, and skin. over a period of time, Daniel (teacher) engaged 4-year-olds Hal, Isaac, and Richard in exploration of their understandings. This included three visits within walking distance in the local community—one to the medical centre to talk with a nurse, one to the local grocery store to look at meat for sale, and the other to the local butcher—to test their working theories about whether or not animals had hearts and blood like humans. Daniel also encouraged them to look closely at their own and their pets’ bodies and features. Here is a snippet of their exploration as they used a (real) stethoscope to try to listen to their hearts beating.

| Hal: | If … your heart isn’t booming you die … If your heart isn’t booming then you won’t be able to go and you go (gasp). |

| Richard: | Mine is not booming and I’m not going to die. |

| Isaac: | Mine’s not booming. |

| Daniel: | We could go to the medical centre and ask them about hearts and see what they say … Okay, take your stethoscope. |

[walk to medical centre]

| Nurse: | Right, now what do you want to know guys? … What would you like to ask? |

| Hal: | Um when your heart stops you stop breathing … And you will go like that. |

| Nurse: | Your heart, what does your heart do? |

| Richard: | Beats your blood. |

| Nurse: | Your heart, your heart it pumps the blood all around the body, okay, but your heart and your lungs work together as a team, because you can’t have one without the other, okay. And if your heart stops beating your lungs can’t work … So what else do you want to know about your heart? Do you think it’s a muscle? |

| Hal: | Oh yeah it’s a muscle. |

| Nurse: | It’s a muscle because it’s got to work, doesn’t it? |

| Richard: | And the muscles give you muscles. |

| Daniel: | So just like your muscles work like this in your arms, so does your heart, and when it goes like that it’s pumping your blood around. |

Another example was 4-year-olds Lola and Sadhaba’s working theories about human hair. As they gently brushed Moana’s (a teacher’s) hair, they shared working theories about the causes of baldness, and why and how people colour their hair. To do so, Lola sometimes stepped aside from the task to think through her ideas.

|

|

This example illustrated how important knowing a child and family is to interpreting interests, inquiries, and working theories. Bianca (teacher) explained to the research team that Lola had a Belgian mother and that they spoke French as their first language at home. Lola’s mother was on a trip to Belgium and Lola’s father was responsible for her when this interaction occurred. Her hair was quite difficult to manage and the teachers had helped her father keep it tidy. This was how the interest had developed and transferred into the children asking to brush Moana’s hair. Bianca felt that the reason for Lola stepping aside from the hair brushing task was so she could concentrate as she mentally translated Bianca’s questions into French, thought about her responses in French and then mentally translated these back into English before trying to articulate them. Bianca was fascinated in particular by the complexity of the language and thinking processes that occurred to lead to some “magical” elements of Lola’s explanatory working theory of baldness.

How can I develop my physical and emotional wellbeing?

Children’s focus on their wellbeing and increasing competence and control of their bodies was evident in the study. This focus was supported by teachers’ efforts to empower children emotionally and physically, and an emphasis on positive social relationships and resolving difficulties amicably. Children’s questions here appeared to include: “Am I safe in this setting?” “How can I enjoy and extend my body’s capabilities?” “How can I be healthy and physically active?” “How can I ensure my physical and emotional wellbeing?”

As described earlier, Chloe used such questions as part of working towards her learning goal of jumping successfully. Brooklyn and Lebron engaged in a dance-like manoeuvre and negotiations as a special ramp was set up for Lebron to ride up and down to develop his physical skills. Providing this ramp also enabled Brooklyn to further develop his interest in gravity, speed, momentum, and force.

How can I express my creativity?

Children’s interest in developing and expressing creativity seemed to be a shared, ongoing interest. Some gender bias was evident. More girls than boys engaged in a range of drawing-, painting-, and collage-based creative activities, with associated early writing attempts from older children. More boys than girls worked with Mobilo and other construction equipment.

The creation of planter boxes at Small Kauri involved both boys and girls, however, indicating that shared strengths and expertise can come together in a real project. further, many children were interested in music and dance, possibly linked to their interests in their cultural backgrounds and in being active, extending and challenging their bodies’ growing capacities. We saw this most in ways different children represented the music and songs of their cultural backgrounds—there was much interest in developing early expertise in playing instruments and singing songs, such as national anthems and those representing popular culture (e.g., in these photos, Gangnam style).

|

|

Teacher practices: Notice, recognise, respond, record, and revisit

How might teachers notice, recognise, respond to, record, and revisit infants’, toddlers’, and young children’s interests, inquiries, and working theories in early childhood education?

Our second research question specifically used the framing for formative assessment promoted by Carr’s work (Carr, 2001, 2008; Carr & Lee, 2012; Ministry of Education, 2004, 2007, 2009a). The terms used are therefore familiar to teachers, and thus our findings are reported directly in relation to them.

Notice – Consistent with previous TLRI projects (Carr, Lee, & the Early Years Wisdom Group, 2010; Davis & Peters, 2011), we found that teachers stepping back to observe and/or listen to children carefully for longer before interacting could lead them to consider children’s knowledge and motivations more deeply:

Only once adults slowed down, could they strive to understand the child’s intentions and goals and avoid hijacking the direction of learning. This requires a culture of trust that an individual’s theories will be taken seriously and an environment where critical thought, wondering and creativity, is encouraged and accepted as a desirable outcome for all children and adults alike. (Davis & Peters, 2011, p. 5)

We particularly focused on efforts to notice combinations of ways that infants and toddlers attempted to reveal their interests: body wisdom, eye movements, pointing, social referencing, displaying emotions, vocal utterances, and “baby flirtation” (see Cooper et al., 2012). We noticed that very young children can concentrate on a seemingly small item for a very long time. Again video footage helped us to analyse ways the interests were revealed (Cooper et al., 2012). In this way, infants’ and toddlers’ “question-asking and question-exploring” (Sands, Carr, & Lee, 2012, p. 553) could be explored more deeply without verbal language. We also found these strategies helpful in interpreting the actions of older children at KiNZ who did not share a language and were learning to speak English, largely through attending the centre.

Using a “pedagogy of listening” (Rinaldi, 2006, p. 15) with older children helped us to notice their ideas, theories, questions, and thoughts. Slowing down to listen carefully avoided making assumptions and/or jumping to conclusions about the nature of children’s interests, inquiries, and working theories. We also noted that the conversations children had when engaged in some everyday play activities were sometimes unrelated to the activity itself and of great significance to their lives. For example, while drawing together on one occasion and on another while playing outside, nearly-5-year-olds Zoe and Mikayla discussed what “turning five” would mean in their lives and the behaviours and learning expected of them at school. As noted earlier, Angie and rosa valued their friendship and life outside the centre and used this as a basis for developing and challenging each other’s cognitive and language understandings in ways less familiar child peers may not.

| Often then, we found that the play activity provided the context for expressing the interest but did not represent the interest itself, hence our deeper and more analytical interpretations of interests. |

Recognise – Using a funds of knowledge lens, and developing a greater understanding of children and families through dialogue and visits to family homes, helped a deeper recognition and analysis of what was significant for children, and why. For example, the number of migrant children and frequent turnover of children and families at KiNZ invited recognition that children’s initial interests were in their belonging and wellbeing in ways linked to family funds of knowledge.

Teachers often noticed children “cooking” in the sandpit and family play area. For example, Stella (aged 2½) had a father who was a chef. when teachers videoed her cooking in the sandpit and listened closely to her selftalk, they realised she had a sophisticated understanding of ingredients and techniques and were able to talk with her family about this knowledge.

Provision of musical instruments, music, and songs was already an important everyday component of curriculum at Small Kauri. Visits to family homes established that at least three fathers had strong backgrounds in music that helped to explain the depth and characteristics of their children’s music-based interests and knowledge.

| While collegial dialogue was common in both settings, sometimes teachers hadn’t realised that they had been documenting the same interests in children, hadn’t made the connection to funds of knowledge and therefore asked families more about these, and hadn’t considered ways to incorporate these interests more deeply in planning for both individual children and the group. Teachers usefully reflected on and puzzled over some matters the visits to family homes raised about children’s interests and teacher responses. They became even more aware than previously that their decisions, conversations, and listening skills could either enhance or, unintentionally, shut down interests. |

Respond – we identified three categories of response. The first was providing opportunities so children could choose activities that enabled them to represent their family interests. At KiNZ, the experience of visiting several apartments and shared living spaces prompted changes to the layout of the previously open-plan learning and teaching environment. Teachers re-configured the layout to smaller, more intimate spaces where individual children or small groups could gather with one activity, such as reading a book or playing with cars or Mobilo. The teachers also became aware of the role technological tools, such as laptops and iPads, played in children’s home lives in contemporary cultures/settings. As a result they enabled such play in ways they had not openly done previously. In addition, further in keeping with the notion of funds of knowledge, teachers invited parent expertise as a contribution to the curriculum, such as when 3-year-old Jessica’s mother was asked to share her artistic knowledge and skills with children. At Small Kauri, additional resources and materials that represented children’s funds of knowledge were added to the environment. A set of real drums for Hunter (and other children) was a major example related to children’s music-based interests highlighted in the previous section (see Cooper, Hedges, Lovatt & Murphy, 2013).

Second, responses involved teachers’ interactions with children.

| As children expressed interests and inquiries important to them, they did not often want information (or additional resources) from teachers. Instead, they wanted an opportunity to be listened to and respected as learners who would be taken seriously and be allowed to theorise and puzzle during efforts at meaning making. |

Teachers also took on a role of gently challenging children’s theorising and knowledge building. Alongside the “conversational oil” (Carr et al., 2010, p. 3) of sustained attention and verbal and non-verbal invitations to keep talking, Daniel found strategies consistent with Davis and Peters’ (2011) project on working theories to be valuable in challenging and extending working theories (Lovatt, 2013). These strategies could be used generally with children’s interests, too, to take the emphasis away from a sole focus on environmental provision. Daniel noted that strategies were combined in multiple ways and over time to shape working-theory development. Daniel analysed his working-theory interactions with children as comprising:

- facilitation—specific facilitation types included involving other children, focusing, requesting a statement to be repeated, revisiting and managing verbal interaction between children

- summarising

- questioning—generally open-ended, used to attempt to clarify children’s thinking; wait time was used

- modelling inquiry and information-seeking approaches

- presenting new information

- using resources.

Third, “puzzling” became an important response as teachers reflected on ways they might respond that were authentic. For example, Lindy (teacher) revealed her thinking about rosa and Angie’s dialogue in a memo as she considered how to acknowledge and extend their thinking:

In this clip we see little snippets of information and past experiences being brought into the conversation. what is their understanding of ‘going’ – going to the show, going to Wellington, going to work, going to Merry Christmas? Or do they understand that going involves some form of transport/travel and moving to another place? They have both seen other productions, the latest being Angelina Ballerina so perhaps they understand what Constance means by going to the show? Do they think that Mary Poppins and Merry Christmas are places? or perhaps people?

Niky considered the challenges that a deeper way of analysing children’s interests and inquiries presented teachers:

I am actually in a bit of a struggle now because I am noticing interests more in depth. when our children are interested in what looks like animal play, I am now looking at it thinking right it’s a lot more than this, I’ve spoken to the parents, it’s actually about the caring nature this child has, her disposition and other factors in her life that have built her up to this. And so now I am thinking, now that I know all of this, what do I do with it, what do I buy? And it’s more of a challenge. In the past you might have provided trips to see animals, read lots of animal books, read on the internet, explored different ideas, find out what they know, what they want to know, go into that project approach. But now that you know there’s a deeper level, how do you [respond]?

Record – Small Kauri moved towards documenting children’s interests and their changes over time using a chart in children’s portfolios. This chart increasingly included information about funds of knowledge. Both centres developed the use of learning stories to incorporate working theories alongside dispositions. Teachers also included their questions and puzzling about children’s interests as legitimate formative assessment rather than thinking documentation had to be somehow “complete”.

In addition, teachers began to document children’s working theories about matters of interest more often. For example, during a 3-month investigation of the difference between “real” and “pretend”, Binita (teacher) wrote up an example of a discussion between three 4-year-olds that illustrated complex ideas in children’s ideas, questions, and challenges to each other’s thinking.

| Zoe: | Pretend is something you can’t see. ghosts, you can’t see ghosts |

| Kael: | Ghosts is real. |

| Zoe: | Cartoons are real, the things on the cartoon are pretend. |

| Thanvi: | I saw they are real. Spiderman is real |

| Zoe: | Spiderman is pretend. |

| Kael: | They [superheroes] come at night so no one sees them. |

Binita asks if they think Spiderman is real.

| Zoe: | He is not. |

| Thanvi: | He is so, Zoe. People go inside that costume and be Spiderman. |

As a research team, we also experimented with an analysis format that more explicitly identified the component knowledge, skills, and attitudes Te Whāriki notes as comprising working theories. This analysis may help “unpack” the constituent components and assist teachers to consider what further provocations or engagement might be valuable (Hedges & Cooper, 2014).

Revisit – First, where interests became a basis for ongoing dialogue between teachers and families, these were revisited and re-documented. The examples of Chloe, with her goal of learning to jump, and Hunter, with his interest in drumming, were ongoing examples.

Second, given that working theories are dependent on children’s knowledge and experience, further experiences were introduced to re-visit, extend, and, at times, challenge, children’s knowledge development in topics children pursued over a period of time. For example, in relation to ongoing debates and theories about what is “real and pretend”, Niky (teacher) encouraged the children to dress in superhero capes and pose for photos. She later Photoshopped these to illustrate how movie-makers can make it appear as if superheroes can fly.

Third, where teacher interest and knowledge coincided with children’s, projects and ongoing investigations occurred that encouraged ongoing development of working theories. Examples included the exploration of the capacities and capabilities of the human body, growing sunflowers, and making planter boxes. Sometimes, however, teachers documented the progress of the project and were less vigilant about documenting the children’s working theories. They explained that this was because they were concerned about the partially formed nature of these ideas and what parents might think if teachers let children continue to work these ideas out and did not “correct” them. Hence, as noted earlier, we began to unpack the constituent elements of working theories to illustrate the complexity and creativity of children’s thinking, and the uncertainty and complexity of teachers’ roles and decision making in children’s working-theory development.

Limitations and future research

A funds-of-knowledge framing does not address well the way children develop interests in matters they have no direct experience of other than through media or other technologies, such as princesses, dinosaurs, tsunamis, and superheroes. Bereiter (2002) refers to this as the “hands-on fallacy” (p. 301) of early childhood education that derives from narrow interpretations of Piaget and Dewey’s work. Further research might illuminate these types of children’s interests.

The key focus of the project was family funds of knowledge. This focus was chosen to highlight and deepen the connections fundamental to the partnership imperatives of Te Whāriki. Consequently, the role of teacher interests, subject content knowledge, and funds of knowledge in stimulating and responding to children’s interests remain to be investigated in future research, along with other centre and community-based funds of knowledge (Hedges et al., 2011).

Implications and recommendationsCurriculum and pedagogy Teachers need to adopt analytical lenses to interpret children’s interests, inquiries, and working theories beyond identifying the activities children choose. Play has deeper meanings. The analytical lenses promoted here are funds of knowledge and a continuum of interests. These complement “working theory glasses” (White, 2012, p. 22) to foster deeper understandings of children’s interests and efforts at meaning making. These lenses encourage teachers to re-think provision of teaching-and-learning (Wells, 2002) environments to reflect the community and context of the setting. Linking with Davis and Peters’ (2011) work, teachers might consider how they develop and maintain a “culture of trust” (p. 5) for teachers as well as children. Assessment decision making Partnerships with families and communities |

Final words

A major rationale for TLRI projects is to research teaching and learning in order to address the achievement lag that statistics have long illustrated is an issue for diverse learners. As Genishi and Goodwin (2008) point out “children are only at risk of failing in school when curricula leave no room for their multiple interests and identities” (p. 278) and teacher actions limit rather than transform children’s participation. We hope that the findings of our project might be considered within and beyond early childhood settings to join the growing number of voices across the primary and secondary sectors also highlighting funds of knowledge as a way to connect homes and educational settings (Hogg, 2013; Hughes & Pollard, 2006). We argue that funds of knowledge provide one foundation for inquiring minds to thrive, for teachers to respond meaningfully to children’s interests, inquiries, and working theories, and for more equitable and responsive education for all learners to flourish.

E raka te mauī, e raka te katau.

A community can use all the knowledge and skills of its people.

About the project team

Left to Right: Niky Spanhake (Small Kauri Early Childhood Education Centre), Trish Murphy (Small Kauri Early Childhood Education Centre), Lindy Ashurst (Myers Park KiNZ Early Learning Centre), Helen Hedges (University of Auckland), Maria Cooper (University of Auckland), Bianca Harper (Myers Park KiNZ Early Learning Centre), and Daniel Lovatt (formerly Small Kauri Early Childhood Education Centre)

Helen Hedges is an associate professor in the faculty of Education at the University of Auckland. Her research programme focuses on children’s and teachers’ knowledge, interests, and learning, and ways these coalesce to create curriculum responsive to partnerships with families and communities. Maria Cooper is a professional teaching fellow in the faculty of Education at the University of Auckland. Her research and teaching interests include everyday teacher leadership, early childhood curriculum, infant and toddler pedagogies, teacher–family partnerships, and children’s interests and inquiries. Lindy Ashurst and Bianca Harper were teacher–researchers at Myers Park KiNZ ELC; Daniel Lovatt, Trish Murphy, and Niky Spanhake were teacher-researchers at Small Kauri ECE Centre. Daniel is now teaching at Mangere Bridge Kindergarten. We all continue to question, reflect on, problematise, deconstruct, reconstruct, and theorise the complexities of teaching and learning in early childhood education.

The important thing is not to stop questioning.

Albert Einstein

References

Alton-Lee, A. (2003). Quality teaching for diverse students in schooling: Best evidence synthesis. retrieved from http://www. educationcounts.govt.nz/publications/series/2515/5959

Bereiter, C. (2002). Education and mind in the knowledge age. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Berk, L. (2001). Awakening children’s minds: How parents and teachers can make a difference. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bruner, J. (1986). Actual minds, possible worlds. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Carr, M. (2001). Assessment in early childhood settings: Learning stories. London: Paul Chapman.

Carr, M. (2008). Can assessment unlock and open the doors to resourcefulness and agency? In S. Swaffield (Ed.), Unlocking assessment: Understanding for reflection and application (pp. 36–54). London: Routledge.

Carr, M. & Lee, W. (2012). Learning stories: Constructing learner identities in early education. Los Angeles: Sage.

Carr, M., Lee, W., & the Early years wisdom group. (2010). Learning wisdom: Young children and teachers recognising the learning. Retrieved from Teaching and Learning Research Initiative: http://www.tlri.org.nz/sites/default/files/projects/9259_carr-summaryreport.pdf

Carr, M., Smith, A. B., Duncan, J., Jones, C., Lee, W., & Marshall, K. (2009). Learning in the making: Disposition and design in early education. Rotterdam, Netherlands: Sense.

Cooper, M., Hedges, H., Ashurst, L., Harper, B., Lovatt, D., & Murphy, T. (2012). Infants’ and toddlers’ interests and inquiries: Being attentive to non-verbal communication. The First Years: Nga Tau Tuatahi/New Zealand Journal of Infant and Toddler Education, 14(2), 11–17.

Cooper, M., Hedges, H., Ashurst, L., Harper, B., Lovatt, D., Murphy, T., & Spanhake, N. (2014). Transforming relationships and curriculum: Visiting family homes. Manuscript revised and resubmitted for publication in Early Childhood Folio.

Cooper, M., Hedges, H., Lovatt, D., & Murphy, T. (2013). Responding authentically to Pasifika children’s learning and identity development: Hunter’s interests and funds of knowledge. Early Childhood Folio, 17(1), 6–11.

Davis. K., & Peters, S. (2011). Moments of wonder, everyday events: Children’s working theories in action. A summary. retrieved fromTeaching and Learning Research Initiative: http://www.tlri.org.nz/sites/default/files/projects/9266_%20davis-summaryreport.pdf

Davis, K., & Peters, S. (2012). Exploring learning in the early years: working theories, learning dispositions and key competencies. In B. Kaur (Ed.), Understanding learning and teaching: Classroom research revisited (pp. 171–182). Rotterdam, Netherlands: Sense.

Genishi , C., & Goodwin, A. L. (2008). Diversities across early childhood settings: Contesting identities and transforming curricula. In C. Genishi & A. L. Goodwin (Eds.), Diversities in early childhood education: Rethinking and doing (pp. 273–278). New York: Routledge.

González, N., Moll, L. C., & Amanti, C. (Eds.). (2005). Funds of knowledge: Theorizing practices in households, communities and classrooms. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Gutiérrez, K., & Rogoff, B. (2003). Cultural ways of learning: Individual traits or repertoires of practice. Educational Researcher, 32(5), 19–25.

Hedges, H. (2007). Funds of knowledge in early childhood communities of inquiry. Unpublished doctoral thesis, Massey University. retrieved from http://hdl.handle.net/10179/580

Hedges, H. (2010). Whose goals and interests? The interface of children’s play and teachers’ pedagogical practices. In L. Brooker & S. Edwards (Eds.), Engaging play (pp. 25–38). Maidenhead, UK: open University Press.

Hedges, H. (2014). Young children’s “working theories”: Building and connecting understandings. Journal of Early Childhood Research, 12(1), 35–49.Hedges, H., Cullen, J., & Jordan, B. (2011). Early years curriculum: funds of knowledge as a conceptual framework for children’s interests.Journal of Curriculum Studies, 43(2), 185–205. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00220272.2010.511275

Hedges, H., & Jones, S. (2012). Children’s working theories: The neglected sibling of Te Whāriki’s learning outcomes. Early Childhood Folio, 16(1), 34–39.

Hensley, M. (2005). Empowering parents of multicultural backgrounds. In N. González, L. C. Moll, & C. Amanti (Eds.), Funds of knowledge: Theorizing practices in households, communities and classrooms (pp. 143–151). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Hogg, L. (2013). Applying funds of knowledge in a New Zealand high school: The emergence of team-based collaboration as an approach. Unpublished doctoral thesis, Victoria University of Wellington.

Hughes, M., & Pollard, A. (2006). Home–school knowledge exchange in context. Educational Review, 58(4), 385–395.Lindfors, J. W. (1999). Children’s inquiry: Using language to make sense of the world. New York: Teachers College Press.

Lovatt, D. (2013). Children’s working theories: Invoking disequilibrium. Unpublished master’s thesis, University of Auckland.

Ministry of Education. (1996). Te Whāriki. He whāriki matauranga mō ngā mokopuna o Aotearoa: Early childhood curriculum. retrieved fromFhttp://www.educate.ece.govt.nz/learning/CurriculumAndLearning/Tewhariki.aspx

Ministry of Education. (2004, 2007, 2009a). Kei tua o te pae: Assessment for learning exemplars. retrieved from http://www.educate.ece. govt.nz/learning/curriculumAndLearning/Assessmentforlearning/KeiTuaotePae.aspx

Ministry of Education (2009b). Te Whatu Pōkeka: Kaupapa Māori assessment for learning. retrieved from http://www.educate.ece.govt.nz/ learning/curriculumAndLearning/Assessmentforlearning/TewhatuPokekaEnglishLanguageVersion.aspx

Moll, L., Amanti, C., Neff, D., & González, N. (1992). Funds of knowledge for teaching: Using a qualitative approach to connect homes and classrooms. Theory into Practice, 31(2), 132–141.

Paradise, R., & Rogoff, B. (2009). Side by side: Learning by observing and pitching in. Ethos: Journal of the Society for Psychological Anthropology, 37(1), 102–138.

Peters, S., & Davis, K. (2011). fostering children’s working theories: Pedagogic issues and dilemmas in New Zealand. Early Years, 31(1),5–17. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09575146.2010.549107

Reedy, T. (2013). Tōku rangatira nā te mana mātauranga: Knowledge and power set me free …. In J. Nuttall (Ed.), Weaving Te Whāriki: Aotearoa New Zealand’s early childhood curriculum document in theory and practice (2nd ed., pp. 35–53). Wellington: NZCER Press.

Rinaldi, C. (2006). In dialogue with Reggio Emilia: Listening, researching and learning. London: Routledge.Rogoff, B. (2003). The cultural nature of human development. New York: Oxford University Press.

Rogoff, B., Moore, L., Najafi, B., Dexter, A., Correa-Chávez, M., & Solis, J. (2006). Children’s development of cultural repertoires through participation in everyday routines and practices. In J. Grusec & P. Hastings (Eds.), Handbook of socialisation (pp. 490–515). New York: Guilford.

Rogoff, B., Paradise, R., Arauz, R. M., Correa-Chávez, M., & Angelillo, C. (2003). Firsthand learning through intent participation. Annual Review of Psychology, 54, 175–203. http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.54.101601.145118

Sands, L., Carr, M., & Lee, W. (2012). Question-asking and question-exploring. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 20(4), 553–564. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/1350293X.2012.737705

Tenery, M. (2005). La Visita. In N. Gonzalez, L. C. Moll, & C. Amanti (Eds.), Funds of knowledge: Theorizing practices in households, communities and classrooms (pp. 119–130). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Wells, G. (1999). Dialogic inquiry: Towards a sociocultural practice and theory of education. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Wells, G. (2002). Inquiry as an orientation for learning, teaching and teacher education. In G. Wells & G. Claxton (Eds.), Learning for life in the 21st century (pp. 197–210). Oxford: Blackwell.

White, E. (2012). Yo ho ho and a bottle of theories: Making exploring working theories an everyday practice. Playcentre Journal, 144, 22–24.

Presentations and publications arising from the project

Cooper, M. (2013, September). Healthy in body: Learning to read infants’ and toddlers’ body language when interpreting interests and inquiries. Seminar and workshop for organisation Mondiale l’Education Prescholaire (OMEP), Canterbury chapter, Christchurch.

Cooper, M., Ashurst, L., Harper, B., Lovatt, D., Murphy, T, Spanhake, N., & Hedges, H. (2013, November). (Re)Igniting home visits in early childhood education: Transforming relationships and curriculum. Paper presented at New Zealand Association for research in Education annual conference, Dunedin.

Cooper, M., & Hedges, H. (2014). Beyond participation: what we learned from Hunter about collaboration with Pasifika children and their families. Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood, 15(2), 165-175. http://dx.doi.org/10.2304/ciec.2014.15.2.165

Cooper, M., Hedges, H., Ashurst, L., Harper, B., Lovatt, D., & Murphy, T. (2012). Infants’ and toddlers’ interests and inquiries: Being attentive to non-verbal communication. The First Years: Nga Tau Tuatahi/New Zealand Journal of Infant and Toddler Education, 14(2), 11–17.

Cooper, M., Hedges, H., Ashurst, L., Harper, B., Lovatt, D., & Murphy, T. (2012, November). Infants’ and toddlers’ interests and inquiries: Being attentive to non-verbal communication. Paper presented at Early Childhood research hui, Hamilton.

Cooper, M., Hedges, H., Ashurst, L., Harper, B., Lovatt, D., Murphy, T., & Spanhake, N. (2013, December). Visiting family homes: ECENZ@2013. Early childhood education series seminar, faculty of Education, Auckland.

Cooper, M., Hedges, H., Ashurst, L., Harper, B., Lovatt, D., Murphy, T., & Spanhake, N. (2014). Transforming relationships and curriculum: Visiting family homes. Manuscript revised and resubmitted for publication in Early Childhood folio.

Cooper, M., Hedges, H., Lovatt, D., & Murphy, T. (2013). responding authentically to Pasifika children’s learning and identity development: Hunter’s interests and funds of knowledge. Early Childhood Folio, 17(1), 6–11.

Hedges, H. (2013, March). Holistic curriculum outcomes: Which, why, for whom and to what effect? Presentation and seminar at Australian Catholic University, Melbourne.

Hedges, H. (2013, September). Healthy in mind: Analysing and supporting children’s working theories. Seminar and workshop for organisation Mondiale l’Education Prescholaire (OMEP), Canterbury chapter, Christchurch.

Hedges, H. (2013, September). Theory, theories and working theories. Presentation for Kidsfirst Kindergartens Education Services managers and head teachers, Christchurch.

Hedges, H., & Cooper, M. (2013, September). Shaking up the territory: Re-envisioning children’s interests and inquiries. Keynote address to organisation Mondiale l’Education Prescholaire (OMEP), Canterbury chapter, Christchurch.

Hedges, H., & Cooper, M. (2014). Engaging with holistic curriculum outcomes: Deconstructing “working theories”. Manuscript accepted for publication in International Journal of Early Years Education.

Hedges, H., & Cooper, M. (2014, February). That was then: This is now: (Re)Positioning teachers amongst children’s interests and inquiries. Keynote address to Early Childhood Professional Support symposium at Faculty of Education, Auckland.

Hedges, H., Cooper, M., Ashurst, L., Harper, B., Lovatt, D., Murphy, T., & Spanhake, N. (2014, March). Visiting family homes: Why, when and how? Seminar for Early Childhood Professional Support at Faculty of Education, Auckland.

Hedges, H., Cooper, M., & Lovatt, D. (2013, January). Collaborating with Pasifika families to make sense of children’s interests and inquiries. Paper presented at Pasifika Early Childhood Education conference, Auckland.

Hedges, H., Cooper, M., & Lovatt, D. (2013, May). Responding authentically to Pasifika children’s learning and identity development: Hunter’s interests and funds of knowledge. Faculty of Education seminar, Auckland.

Lovatt, D. (2013). Children’s working theories: Invoking disequilibrium. Unpublished master’s thesis, University of Auckland.

Lovatt, D., & Hedges, H. (2014). The construct of working theories: Constructivist and sociocultural perspectives. In H. Hedges & V. Podmore (Eds.), Early childhood education: Pedagogy, professionalism, and policy (pp. 29–42). Auckland: Edify Ltd.