| Education for sustainability (EfS) has been rapidly growing in New Zealand schools, bringing with it an interest in whole-school approaches to develop EfS and a focus on action competence as a means to understand student learning in this field.

It is currently UNESCO’s decade of education for sustainable development, which calls for “a new vision of education that seeks to empower people of all ages to assume responsibility for creating a sustainable future” (UNESCO, 2002). Education for sustainability (EfS) fits with such a vision in that it expands on environmental education to include social, economic, political and cultural perspectives, as well as a focus on global equity in the use and distribution of natural resources. Tilbury and Wortman (2005) describe a whole-school approach to sustainability as a process of change to integrate sustainability principles across all aspects of school life to the extent that a school becomes an evolving model of sustainability. A review of five international EfS programmes identified 12 characteristics and 12 critical success factors associated with sustainable schools (Henderson & Tilbury, 2004). The interaction of the characteristics and factors makes for a rich array of possible expectations and outcomes for whole-school approaches but our literature review did not identify any useful tool for examining these. Previous research has suggested a tentative relationship between whole-school approaches and particular understanding of student learning (Bolstad & Baker; 2004, Mardon & Ritchie, 2002; Tilbury & Wortman, 2005). Nevertheless, while a range of student outcomes have been associated with particular EfS programmes, we identified few robust tools for exploring the holistic nature of student learning in EfS. Our literature review and experience suggested that action competence offers the greatest promise for understanding and supporting student learning in EfS. Jensen and Schnack (1997) define action competence most simply as “the ability to act with regard to the environment”, which they argue goes well beyond pro-environmental activity or behaviour modification. Instead it incorporates intentional, participatory and authentic action taking that requires knowledge about underlying causes of unsustainable practices and is guided by students’ experiences, attitudes, values and local contexts (see for example, Uzzell, 1999). The New Zealand curriculum key competencies converge well with the action competence literature. There is little empirical research available on what whole-school approaches and action competence look like in practice. Nor do we have reliable instruments to examine progress in these two areas. Our previous TLRI project examined action competence in a New Zealand context and led us to recommend that a research-based tool for evaluating action competence be developed (Eames et al., 2006). The current TLRI project provided an opportunity to do this alongside our parallel work on whole-school approaches. |

Project aims and research question

The aims of this TLRI project were to:

- explore what whole-school approaches to EfS in New Zealand schools might look like and to design a framework for analysing these approaches that is meaningful for schools

- design a framework for investigating the development of action competence in students, teachers and their schools

- explore the nature of the relationship of a whole-school approach to EfS and student learning (as action competence).

The main research question guiding the project was: “What is the relationship between whole school approaches to EfS and student learning?”

Research design and methodology

We worked with four primary and two secondary schools in 2007 and 2008 to design and test two frameworks to understand whole-school approaches and action competence, and schools’ development of them. The schools were part of the Enviroschools Programme, which advocates whole-school approaches to sustainability. Six EfS advisors each partnered with 1 to 2 teachers from each of the six schools, and each research-practitioner partnership was supported by a more experienced university-based EfS researcher. These partnerships combined theoretical and practical perspectives on EfS. The project was also informed by a literature review carried out by the research team and a previous TLRI project that investigated teachers’ pedagogy in EfS and its potential to promote students’ action competence in environmental education (Eames et al., 2006).

Action research process

Our action research methodology enabled us to develop our understanding of whole-school approaches to EfS and students’ action competence by designing and testing two analytical frameworks. These frameworks (the whole-school approach framework and the action competence framework) were initially drafted by small teams and then revised, tested in the schools in 2007, revised again, tested again in the schools in 2008 and revised for a final time. The project was conducted in 12 phases:

- discuss project aims and process with team

- begin literature review

- develop initial frameworks drawing on literature and project members’ experience

- conduct six case studies to better understand the nature of whole school approaches to EfS and student action competence and trial initial draft frameworks

- produce written and verbal reports on the results of each case study, including suggestions for a review of the frameworks

- collate and analyse all case study findings as a full team

- review both frameworks, and draft a teacher and facilitation guide for each framework

- pilot revised draft frameworks and the accompanying guides in case study schools

- produce a written and verbal report on the results of each case study, including suggestions for a final review of the frameworks

- collate and analyse all case study findings as a full team

- refine frameworks in response to case study analysis

- finalise frameworks and guides.

We analysed the data from each case study (i.e., phase 4 and phase 8) against the frameworks to produce a site-based analysis report for each school. Team members presented the main findings at full team meetings where we worked together to examine and improve the validity and utility of each framework on the basis of the results.

Case study methods

The six schools ranged in decile, location, size, and ethnicity of the student body. Where possible, each initial case study was based on specific actions for sustainability that the teachers and the students had been involved in, and each included most, if not all, of the following:

- semi-structured interviews with key staff and other members of the school community (e.g., principal, lead EfS teacher, other teachers, caretaker, board of trustees member, parent)

- analysis of relevant school documents, including school vision, newsletters, teaching plans, and operational manuals

- observations of school environment and operational practices, and if appropriate classroom/EfS activities

- interviews with students (students were interviewed whilst they walked around the school describing actions that they had taken for sustainability within the school).

During the second case study, we put a greater emphasis on explicit staff and student input into the revised draft frameworks. For example, the whole-school approach study was assisted by the draft facilitator guide (see phase 7) and progressed through the four dimensions guided by the following questions:

- Is this aspect meaningful for your school?

- What evidence would you consider in evaluating your school against this aspect?

- What rating would you give your school?

- Would you like to do anything to improve this rating/practice? What could you do?

Findings

The two frameworks, the whole-school approach framework and action competence framework, are the primary output of this research project. We found that the frameworks have three purposes for schools:

- to clarify what is meant by whole-school approaches and action competence in EfS

- to identify what might be involved in initiating or further developing whole-school and action competence approaches in EfS

- to identify evidence by which teachers could assess development of their whole-school approach and student action competence in EfS.

Whole-school approach framework

The whole-school approach framework comprises four dimensions: people, programmes, practices, and place. Each dimension has between 3 and 10 aspects that our action research has demonstrated to be important for developing a whole-school approach to EfS. For each aspect, a set of indicators enables a school to consider its current situation on a five-point scale from emerging to well developed. Table 1 provides an example of one dimension of the framework—the people dimension.

| PEOPLE | WS1 | Working collaboratively across all groups involved in the school |

| WS2 | Reflecting the cultural diversity of the school and its community | |

| WS3 | Acknowledging New Zealand’s bicultural foundations | |

| WS4 | Having community relationships for learning | |

| WS5 | Engaging in participatory key decision making | |

| WS6 | Being involved in action for sustainability | |

| WS7 | Having support from school leaders for EfS in the school | |

| WS8 | Involving staff in professional development in EfS | |

| WS9 | Recognising the school as part of a local, national and global community in EfS |

|

| WS10 | Celebrating whole school achievements in EfS |

Table 2 provides an example of the five-point scale for one aspect of the people dimension on the framework—working collaboratively across all groups involved in the school (coded WS1).

| PEOPLE | |||||

| Aspect | Absent | Preparatory | Emerging | Developing | Well Developed |

| Working collaboratively across all groups involved in the school WS 1 |

No collaborative working relationships between groups involved in the school | Awareness of the importance of collaborative working relationships | Collaborative working relationships exist between some groups involved in the school | Collaborative working relationships exist between most groups involved in the school | Collaborative working relationships exist between all groups involved in the school |

Action competence framework

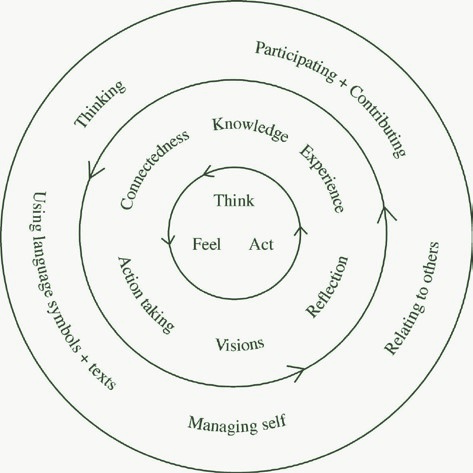

The action competence framework presents six aspects that the research project suggests indicate the development of student action competence: experience, reflection, knowledge, visions for a sustainable future, action taking for sustainability, and connectedness. The framework provides a descriptor and explanation for each aspect (see Table 3). The framework also outlines learner and teacher roles associated with each aspect alongside a range of suggestions for developing these roles, links with the key competencies in the New Zealand curriculum, and multiple sources of evidence for considering assessment of student learning in relation to each aspect.

| CODE | ASPECT |

| AC1 | Experience – Experience refers to a state, condition (feelings) or an event that has happened. The interpretation of this experience may be personal and/or collective. |

| AC2 | Reflection – Reflection is the ability to enquire into your experiences through a process of critical thinking. |

| AC3 | Knowledge – Knowledge relates to both conceptual and practical understanding of sustainability and the processes through which knowledge is gained and used. |

| AC4 | Vision for a sustainable future – Future visions for sustainability consider how we might like things to look and also about what changes need to be made now for the future. |

| AC5 | Action-taking for sustainability – Action is the intentional act of doing something. It is carefully-considered behaviour that promotes sustainability. |

| AC6 | Connectedness – The interconnectedness between people and all aspects of the environment: this includes making connections between thinking, feeling and acting (head, hearts, hands). |

Figure 1 illustrates the development of action competence.

FIGURE 1. The development of action competence

NOTE. The development of action competence (middle ring) is related to international conceptions of EfS (inner ring) and New Zealand key competencies (outer ring).

Case study findings—an example

The following summarises the findings from the second year (phase 9) of one of the case studies, a small city-based Catholic primary school. This school has a high Pasifika population and strong community support, and has been involved in EfS for a number of years.

The school staff found the whole-school framework useful for helping them to understand the complexity of EfS. They were initially daunted by its size but were more comfortable when able to see it in its four sections (people, programmes, practices, and place).

They rated themselves strongly on most of the people aspects, believing that they put a lot of emphasis on their community and its culture. The teachers explained how they were developing EfS in their teaching programmes but the framework helped them to identify that there was still further progress to be made in some programme aspects. They rated the school lowest on the other two aspects, practices and place, seeing these as key areas to work on further.

When considering development of action competence, the teachers were most comfortable with, and could provide evidence for, three of the six aspects. They were students’ development of knowledge, experiences, and action taking for sustainability. Teachers were least confident about developing reflection and interconnectedness with their primary school students. Interviews with students corroborated these findings. The students demonstrated knowledge and experience they had gained through sustainability-focused actions, but were less able to critically reflect on this or articulate an understanding of interconnectedness.

There was some evidence of a relationship of a relationship between aspects of the whole-school approach being taken and development of particular aspects of action competence.

Limitations, and suggestions for future research

While this project drew significantly on international literature, and the experiences of experts in EfS research and practice, the validation of the frameworks rests currently on a sample of six New Zealand schools. We would therefore like to see these frameworks continue to evolve. We raise the following questions for future research:

- How effective are these frameworks in bringing about change in schools across a variety of schools?

- What does student progression in action competence look like across school levels?

- Can these tools be used in other educational settings such as tertiary, early childhood, and so on?

- What does an action competent teacher/school look like?

Conclusion

Through our research we came to understand the incredible complexity of whole-school approaches to EfS and, in particular, of action competence. While we were able to produce a development matrix for the whole-school approach framework, it became clear during the research process that this was neither possible nor appropriate for the action competence framework. This complexity means that we can only offer very tentative responses to our research question.

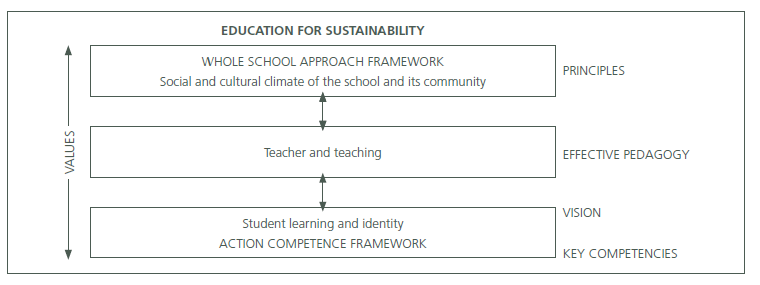

When we discussed each case study school in depth, we found that the particular nature of its whole-school approach could be seen to be embedded in the social and cultural climate of the school and its community. Teacher and student descriptions of environmental action projects provided us with additional insight into what appeared to be a relationship between that climate and student learning and identity. This relationship appears to be mediated by teachers who act as interpreters, conduits and culture brokers between the social and cultural climate of the school and its community, and the development of student learning and identity. As Figure 2 shows, this reciprocal process sits within the New Zealand curriculum (components in italics).

FIGURE 2. The relationship between a whole-school approach to EfS and action competence in the context of the New Zealand curriculum

Research Team Members

Project director:

Chris Eames, University of Waikato.

EfS/research mentors:

Barry Law, University of Canterbury; Miles Barker, University of Waikato; Heidi Mardon, Enviroschools Foundation.

Advisor-researchers:

Lyn Rogers, University of Waikato; Anna Scott, University of Waikato; Anne Radford, Massey University; Jock McKenzie, Massey University; Rosemarie Patterson, Private Consultant; Faye Wilson-Hill, University

of Canterbury.

Teacher-researchers:

* Cathy Carroll, Kevin Booth, Andrea Soanes, Jo Barlow, Jill Crossland, Jenny Clarke.

* School names protected

References

Bolstad, R., & Baker, R. (2004).Environment education in New Zealand schools: Research into current practice and future possibilities. Vol.2. Wellington: Ministry of Education.

Eames, C., Law, B., Barker, M., Iles, H., McKenzie, J., Williams, P., et al. (2006). Investigating teachers’ pedagogical approaches in environmental education that promote students’ action competence [Electronic version]. Retrieved 3 November 2008, from www.tlri.org.nz/publications.

Henderson, K., & Tilbury, D. (2004). Whole school approaches to sustainability: An international review of whole school sustainability programs: Report prepared by the Australian Research Institute in Education for sustainability for the Department of the Environment and Heritage. Sydney: Australian government.

Jensen, B. B., & Schnack, K. (1997). The action competence approach in environmental education.Environmental Education Research, 3(2),163–179. Mardon. H., & Ritchie, H. (2002). Enviroschools programme evaluation report. Wellington: Enviroschools.

Tilbury, D., & Wortman, D. (2005). Whole school approaches to sustainability.Geographical Education, 18, 22–30.UNESCO. (2002).Education for sustainability – From Rio to Johannesburg: Lessons learnt from a decade of commitment. Paris: UNESCO.