1. Introduction

Successful transition of secondary school students into tertiary study is a priority for secondary schools, tertiary institutions and government alike (see, for example, Bazerman, 2007; Batholomae, 2005). The National Certificate of Educational Achievement (NCEA) has, as one of its goals, the effective preparation of senior secondary students for higher education; the Tertiary Education Commission’s (TEC) Tertiary Education Strategy 2014–2019 highlights student success (particularly of at-risk students, including Māori and Pasifica) in higher education as one of its goals; and universities are responding to this strategy by implementing enhanced transition and retention strategies.

This research was a response to anecdotal evidence that, despite best intentions by secondary schools and tertiary institutions, the transition of students into tertiary education remains problematic. Our hypothesis was that a significant gap existed within the educational experiences of students bridging the transition between secondary and tertiary education, and that the key to addressing this gap was academic literacy (Shanahan & Shanahan, 2008). By focusing on academic literacy pedagogy in both the senior secondary and first year tertiary sectors, bringing teachers across sectors together to engage with academic literacy pedagogy, and supporting transitioning students’ academic literacy, we aimed to reduce the gap in the transition between secondary and tertiary study.[1]

In this research, we distinguish between academic literacy pedagogy and writing skills pedagogy. A basic tenet of academic literacy is that thinking skills and writing skills develop concurrently, and that students learn effective academic writing through understanding how disciplinary knowledge is made (see, for example, Fishman et al, 2005; Emerson et al, 2005). Current conventional interventions for improving levels of academic literacy (e.g. university preparation courses, student learning centres and academic writing courses) typically focus primarily on developing academic writing skills rather than more advanced rhetorical and metacognitive strategies and capacity.[2]

The goal of this project, then, was to strengthen the transition process (particularly for low-mid decile schools with a poor record of transition) by bringing literacy practices across the transition into alignment and improving students’ academic literacy during the transitional years during Year 13 and first year tertiary study. Our objectives were to:

- develop, implement and assess a revised approach to the embedding of academic literacy skills in the senior secondary curriculum and first year tertiary study

- model sustained partnership between secondary and tertiary teachers in the development of academic literacy pedagogy and resources, to facilitate more effective strategies for transitioning students into academic literacy.

Despite a plethora of research into literacy in schools and universities in New Zealand, and a strong strategic interest in transition, particularly of at-risk students, the intersection of these two issues had not, prior to this study, been investigated.

2. Research methods

This study was conducted as a participatory action research (PAR) project over 2 years.[3] The PAR team comprised academic researchers, secondary teachers and peer tutors (see section 3.2.2). PAR was chosen as a methodology because this method:

- facilitates change and change monitoring

- fosters collaborations between researchers and practitioners

- provides effective models of team-driven change to teachers

- takes place in a practical context but ensures that context is informed by research.

The project had three key platforms:

- resourcing teachers

- using young peer tutors and academic induction to develop student confidence

- peer support for teachers.

The first year of the research focused on senior secondary school (students and teachers), and in the second year we extended this research with schools, as well as supporting the student cohort transitioning into tertiary education, and disseminating our work in the tertiary context.

Five rural/provincial secondary schools from the central North Island were part of this project in year 1, and seven (including one from Northland) in year 2. The schools engaged in this project had the following characteristics:

- mid-low decile

- high Māori population

- principal and teachers with high aspirations for their students

- poor record of successful transition to tertiary education.

We invited literacy leaders from each school to coordinate the project within their own institution, and the literacy leaders identified staff within the school to participate in the research. While all students within the participating teachers’ classrooms (at Year 13—and in some instances Year 12) were impacted by the teachers’ project-related activities, we invited only those who were planning to transition to tertiary study to engage with the research.

2.1 Data collection

Reflective enquiry (participant journals, reflection activities during meetings) was central to our data collection methods, but we also gathered data in a variety of forms, including:

- teacher online surveys/interviews

- interviews with students

- observation of classes

- research cycles of the peer tutors

- recorded meetings

- ANCIL transition rubric (in year 2—see section 3.4.1)

2.2 Year 1 (2013): resourcing Year 13

In year 1, the focus of the researchers, literacy leaders and principals was resourcing teachers and developing peer support teams for teachers within each school, and developing peer tutor and academic induction strategies for Year 12–13 students. The main activity of the project team was resourcing and enabling reflective teachers. Strategies for engaging teachers included:

- meetings between secondary and university teachers in associated disciplines

- academic literacy workshops with literacy leaders

- intensive information literacy (IL) workshops with teachers

- provision of resources

- peer support hubs for teachers exploring academic literacy development in their classrooms

- preparing existing regional literacy and subject leaders (i.e. teachers with prior knowledge and professional commitment) to be project champions in their schools in year 2

- raising teachers’ awareness of the nature of contemporary tertiary learning

- co-ordinating a series of hui with participating teachers where we methodically recorded teacher reflections about their practice, identified gaps in pedagogic knowledge or skills, and developed expertise to support senior students’ transition.

At the same time, we worked to support students’ academic literacy through the transition. Strategies included:

- peer tutors working with students to support student literacy/confidence

- academic induction days for students, focusing on note-making, summarising, the role of the lecture and tutorial, critical reading, and writing to synthesise information

- introducing IL strategies through university library visits to enhance on-line research techniques

- explicitly articulating the academic and IL demands of tertiary study and challenging students to consider the implications for their current approaches to study.

2.3 Year 2: Resourcing first year tertiary, and extended dissemination

Year 2 involved extending our work with schools (adding new schools and extending our reach into schools who had participated in year 1) and disseminating our findings to tertiary institutions. We also aimed to support students from our schools who were transitioning from Year 13 into first year tertiary study.

Similar forms of interaction with participating schools continued into year 2 (2014). The number of participating schools increased to include two low decile schools, from Taranaki and Northland. Data collection methods remained the same as for year 1, with the addition of the ANCIL transition rubric.

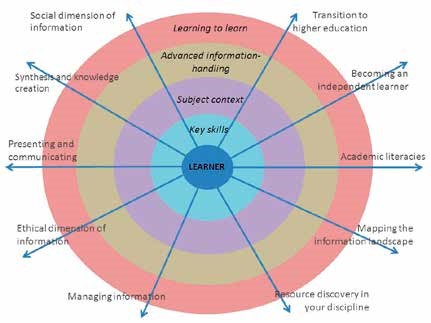

2.4 A key concept: A New Curriculum for Information Literacy (ANCIL)

A central platform that supported our work throughout the 2 years was ANCIL (by British researchers, Secker & Coonan, 2013), which we used to reinterpret achievement standards and NCEA as enablers of academic and information literacy. The ANCIL framework, which is made up of ten strands that recognise the transition from senior secondary to tertiary learning (see Figure 1), provides teachers with “a series of practical steps through which to scaffold the individual’s [literacy] development” (Secker & Coonan, 2013, p. xxiii). ANCIL “advocates a close alignment with not only the intended learning outcomes, but also the assessment mechanisms and learning activities employed to achieve the outcomes.” (Ibid).

Figure 1: ANCIL framework (Secker & Coonan, 2013)

ANCIL is discussed further throughout the report and in detail in section 3.4.1.

3. Key findings

In each of the following sections, we outline the challenges identified at the outset of the research, and then discuss how the research helped shift attitudes/approaches towards supporting students through the transition.

3.1 The secondary sector

3.1.1 Secondary teachers’ understanding of the university sector needed urgent revision

One of the key findings of our research was that, with the exception of recently-graduating teachers, or teachers who had recently upskilled through graduate study, secondary teachers were largely unaware of the extent to which tertiary education has changed (pedagogy, tertiary teachers’ literacy and IL expectations, learning delivery methods, and assessment) over the last 20 years. This recurring theme was expressed most poignantly by one of our senior teachers:

I feel ashamed. I have been telling my year 13 students every year that I am preparing them for university: I was not.

His comments were supported by the teachers in our study. Examples of specific issues of which secondary teachers showed limited awareness included:

- The range and complexity of assessment forms

When we brought together teachers from across the sectors, a key theme was secondary teachers’ astonishment at the range of internal assessment types beyond essays and reports.

It was interesting seeing the range of different formats that assignments should be in; that seemed to have changed quite a lot. There’s a lot more variety … formats that students would largely be unfamiliar with … So it’s not about just making them do a narrow range of presentation styles or formats. There’s not one set way you can show them how do things. It’s trying to get them to be open to different formats and have the skills of ‘how do I approach something that is unknown?’

In an early meeting (year 1) between secondary and university teachers, we asked the university teachers to bring in first year assessment tasks and explain to the secondary teachers the level of support offered to students to complete the assignment. The secondary teachers viewed these tasks as unachievable for their transitioning Year 13 students, who they perceived would lack the writing, thinking and independent management skills to achieve the tasks without detailed scaffolding.

- The increased demands on students’ ability to independently interpret and manage complex tasks

The level of independent learning expected in the first semester at university was of particular concern to teachers. They recognised that the level of support would be severely limited compared to that provided in schools.

[Students can’t] just rely on their ‘this is how it’s done’ or just that openness of, ‘I’ve got a problem, where do I start, what tools do I have’, and not freak out, and give up, and wait for someone to offer help, because they won’t get that support. They won’t have someone come along and say ‘don’t give up. You can do it’.

The extent to which online learning pedagogies in particular required students to become independent learners at university level was another key concern. While online learning was not new to teachers, the extent to which university students were expected to access and engage with online information independently was new. Senior students in our schools largely depended on the teacher as an external motivator and scaffolder of information, and through engaging with our project, teachers saw the need to change. As one of our teachers commented:

I think the biggest thing I’ve taken from it is that if I don’t let go of it and free myself up from feeling responsible for the students’ product and never ask them to take responsibility for their own product, they are going to fail in the future. That we are babying them through NCEA and that we really need to put the pressure back on the student. Still do the quality teaching, but the expectation has to be that they take responsibility.

However, this issue of encouraging student independence in Year 13, in preparation for tertiary study, proved problematic for teachers and was perceived as a high risk strategy in their context—a theme we will return to in section 3.1.3.

- The changing nature and role of the university library

The visits to the library as part of the academic induction days highlighted the shift in demands on first year students being able to access quality information online independently. Teachers were particularly impressed by the provision of multiple academic databases, and their widening role in IL education. But the library environment was a significant issue for our teachers:

I think I was more impressed with the change in the environment rather than—well, I expected it to be a digital age. I expected all that to happen, but it was the environment: the library is now a center of information learning rather than a quiet place to read a book.

IL more broadly became a major theme of this study (see section 3.1.2)

- The strict referencing protocols needed for students to avoid plagiarism

The range of sources available to students and the way tertiary students are expected to engage with sources and acknowledge them appropriately was an area where most teachers agreed they were failing to support their students adequately.

3.1.2 Teachers under-estimate the centrality of information literacy in the transition

Secondary school teachers are less knowledgeable or unaware of rapid expansion and changes in IL. Unless teachers have had recent experience of further university study, this included:

- lack of recent exposure to and use of academic databases for research

- little knowledge of search strategies for optimising search results

- limited understanding of how to verify website integrity, authenticate content and judge currency

- heavy dependence on Google and on prepared resources held on state education websites

- little use of publicly available databases such as EPIC and Google Scholar

- little appreciation of the enhanced role of the school library, or librarians as sources of IL instruction/resource provision.

- reluctance to use resources that were perceived as outside the purview of their teaching course, or which did not have immediate relevance to the topic and its assessment task.

Furthermore, teachers’ engagement with source material within the classroom was problematic in terms of preparing students for transition. Unless students were studying a discipline where primary sources were explicitly required (e.g. history), most students were not exposed to primary research, not expected to engage with long or complex texts, and not required to engage critically with source material. Instead, the teachers in this study most often provided synthesised sources they had written themselves. Changing this strategy was a significant aspect of the project:

I saw my role as the teacher as being one of processing information for the students to make it more appealing and easier to understand. By doing this I was taking away from my students some very valuable and meaningful opportunities for them to learn and develop into a more independent learner. Through being involved in this project, I have stopped doing this. Students are now working with very sophisticated and demanding texts. They are spending more time looking at the structure of the text and how to approach it. I am now explaining to students how to do this process for themselves instead of doing it for them in advance.

Our research further showed that senior secondary school students adopt non-critical positions with respect to evaluating information. This includes:

- dependence on Google to locate relevant websites

- acceptance of the first few hits as relevant and valuable

- a cut and paste approach to assignment completion

- difficulty integrating information into their own writing.

A critical issue was teacher perceptions regarding students’ attitudes to reading: they perceived students as reluctant to engage with reading difficult texts, and believed that difficulties with reading would impact on students’ ability to produce quality work:

Sometimes the more academic texts that we actually put in front of [students] the further away the accessibility comes for them … . If we asking them to read the academic texts, you are creating a rod for your own back.

Teachers reported that exposure to academic texts and quality sources during university visits resulted in two key changes in their classroom: students overcoming resistance to reading and engaging in more reading and writing, enabling teachers to take new approaches when encouraging students to read:

I think that they are becoming more used to having to read more, and getting the information from the texts and put it out in a way that shows they’ve gained a good understanding of what they read. They’re writing more than they used to. They are more willing to work on a piece of writing rather than … offer it to you just before it’s due and say, “can you just have a look at this. Is this okay, and what more you think I might need to do.

The strategic decision to bring students and teachers into the university environment and expose them to forms of current tertiary practice made visible the absence of IL instruction in senior instructional programmes. Teachers indicated that school libraries are not well-equipped to engage students in research practices:

I don’t think we’re that well equipped at all. [The library] has been an area that we’ve been very weak in and I don’t just mean that in terms of books, I just mean in terms of staffing it. We’re reliant on volunteers at the moment and I have raised it at the curriculum development level, but there’s a great deal of potential there to actually have someone who knows what they’re doing and can direct students to good sites and help them actually do that research because oftentimes teachers may not have the information or the time to help the students do that.

At times, the lack of school-based technical resources led to frustration regarding IL:

It’s like Pandora’s Box. I feel very frustrated because I haven’t got a functioning library. I think I’ve been teased by the possibility of what I could be doing. … We cannot access as much information as we would like to be able to access but when [students] saw what was inside that box at University, it was mind-boggling for them… [The problem is] database issues; at library level, and school-wide, there are not enough computers, an inconsistent approach to the research process and the inability to access information through what’s available to us.

A further frustration related to the need for increased resourcing in terms of having skilled, professional librarians in schools and greater access to databases:

The limitation for me as a science teacher then wasn’t the lack of information or availability of information. It was not having someone else like a core librarian who has enough science or research ability to go and find sources so that I could provide kids with a wide enough range of sources so I wasn’t spoon feeding, but I was still giving them sources that were scientifically accurate enough for them to be able to do the assignment at the level they needed to do it at … I couldn’t do it all myself. I simply haven’t got time to go out and read all of those sources myself.

Teachers also recognised their own IL levels as a barrier to how much they could teach students effective research processes:

We’ve found looking at the data from last year at the school that there was no significance with research in the school. … lots of departments steer away from research because they’re not quite sure how to teach it … The reality of research at secondary school is that frequently the teacher will say ‘go and find out about …’ and the students are not given much of a framework to use, you know, a method around how to collect, how to store and how to use the information that they do find.

The university library sessions in particular confirmed information skills as an important feature of senior secondary academic instruction in tandem with academic literacy skills. Teachers indicated that the university library visits helped shift both their approaches to teaching IL, and students’ approaches to research.

I’m much more aware. I’ve got half an eye on university and the demands of that with my students, and I’m teaching them now at Year 13. And certainly the information literacy, the skills and the knowledge that they need for that, is actually taught much more actively than it was in the past. Obviously, the standards realignment has changed that, as well, in the sense that now the research at Level 3, which I do, does require them, to do a lot more research of secondary texts and to use databases such as EPIC and Google Scholar and so on. And that’s, again, part of the programme that is actively taught.

Information literacy became an unexpectedly significant issue in this project: we had not anticipated that this would become such an important part of the process of transitioning students into academic literacy. Subsequently, we ran intensive IL workshops for teachers, including upskilling teachers on databases that were available to them and their students, and worked to support them as teachers of information literacy.

3.1.3 The impact of NCEA is complex

A key finding of this research is that, while teacher perceptions of the management of NCEA have potentially detrimental impacts on the integration of literacy and independent learning strategies in classrooms, the New Zealand Curriculum (NZC) and NCEA, particularly following the realignment, have the potential to realise and support the aims of this project. Our work has shown how this may be achieved, but teachers need to engage with the aims of the realignment, and acquire the skills to implement the new approach. ANCIL (see section 2.4) proved an effective way of shifting teacher perceptions and enabling them to integrate literacy more effectively into the classroom.

Our initial findings in year 1 related to the difficulties caused by teacher anxieties around accountability:

- Product was valued more than process. That is, the accurate completion of NCEA assessment tasks (as products of teaching) appeared to be prioritised at the expense of learning processes which, at senior secondary school, must involve critical engagement with text.

- Teachers saw the use of NCEA as an annual measure of school and teacher effectiveness, and the setting of national achievement targets, as placing them under considerable pressure to “get students through”.

The resulting emphasis on supporting Year 9–11 achievement that tends to take a deficit view of bringing students up to standard thus reduced opportunities for teachers to focus on extending capabilities of more able learners in Years 12 and 13.

- NCEA courses are well resourced through Ministry of Education, NZQA and TKI websites. This helps teachers construct the intensively scaffolded learning experience mentioned above for many students. Ironically our teachers reported that this made their students more dependent upon teacher instruction. Further, such resourcing means that teachers do not necessarily have to look regularly for less familiar teaching materials, beyond those provided—thus inhibiting teachers’ IL skills development.

- The disciplinary or subject structure of NCEA reinforces teachers’ perceptions of NCEA as a test of content learning, and of themselves as primarily content teachers. Important literacy skill instruction happens indirectly along the way, or students at advanced levels are assumed to know how to be literate already, based on earlier years of instruction (Shanahan & Shanahan, 2008).

This focus on product, result, and public measurability is compounded by perceptions that teaching programmes are already crowded—permitting little or no space to strategically introduce other elements, such as disciplinary academic and IL instruction.

A recurring theme from our teachers was “we cannot risk our students failing.” One teacher explained

If I do not get a good enough pass rate, there are consequences for me as a teacher, for the school, and for our community. The media and the ministry will be on our back. We just cannot take risks over outcomes.

As a consequence, the teachers were highly risk-averse. This led to some of the difficulties we have already discussed: teachers synthesising material for students to shift the burden of engaging with complex reading tasks, and engaging in extensive scaffolding of written assessments, including over-reliance on exemplars.

What teachers recognised, in this project, was that a consequence of such risk-aversion was that students did not have the opportunity to develop sufficient independence as learners to cope well in a tertiary environment.

I have to balance [over-compensating] with the fact that we’re a small school and we have to have good results … in a bigger school you can sort of get away with having some kids not achieving and say ‘well, you know, they chose that’ and I have to kind of balance that a little bit. But at the end of the day, they have to do this themselves and I’ve always been of a mind that I try to treat these guys like young adults. It’s up to them to do it. But babying them … is not going to be a good thing.

Significantly, our discussions around NCEA shifted throughout the process of the research. In year 2, teachers came to realise that NCEA and the NZC has the potential to provide a flexible cognitively demanding learning experience for students pursuing higher education. The NZC is a remarkably flexible curriculum, offering opportunities to build literacy into the educational experience of students at senior levels. Our research suggests that the recent Standards Realignment process has the potential to position critical analysis, academic literacy and IL as pedagogic content knowledge crucial to NCEA success at Levels 2 and 3. In particular:

- The NZC—and its delivery and assessment through NCEA—has the flexibility to be customised to learners’ needs. There is no regulatory requirement for each NCEA level to be completed within one year. NCEA gives teachers the opportunity to create time and space to develop content knowledge through a literacy-centred instruction.

- A number of achievement standards use research methods to help build student knowledge. Students are required to critically engage with unfamiliar disciplinary primary and secondary source materials to find, select and retrieve and use information. They are no longer the passive recipient of teacher information.

- Levels 7 and 8 of the New Zealand Curriculum Framework now directly inform the levels of cognitive challenge set at NCEA Levels 2 and 3 of the New Zealand Qualifications Framework. The progression of cognitive demand is now more identifiable across both frameworks. The achievement objectives, criteria and indicators require teachers to scaffold students’ academic skill development in order to co-construct disciplinary knowledge. These skills may be accurately described as advanced academic and IL skills.

- The ANCIL framework, when correlated with the NZC, has the capacity to reframe teachers’ understanding of literacy and provides a way to integrate literacy more effectively. We identified points of alignment between ANCIL and the NZC/NCEA and trialled resources based on the ANCIL framework (Kilpin et al, 2014a) in our participating schools. Teachers were asked to align the NCEA assessment standards with strands of the ANCIL curriculum to determine whether the assessments contained a deeper element of IL development that could be explicitly nurtured as students completed assessment tasks. At least five of the strands were implicit in the assessment standards, and teachers explored ways to extend these competencies in their students’ learning.

Thus, our research suggests that, rather than be seen as a restraint on teacher practice, NCEA (applied differently in schools, and constructed in national policy), when aligned with ANCIL, has the potential to raise academic and IL skills and knowledge of students at senior high school level, and better prepare them for transition to tertiary study.

[This project] is completely relevant and valid and it’s where those Level 3 standards are heading; they’re heading towards a bit more freedom for students and teachers and that whole empowerment through the research process—you can do anything if you can find stuff and use it.

3.1.4 Teachers—summary

In this research, we aimed to enhance teachers’ capacity to support their students into independent learning and to give students the motivation to engage with literacy. The outcomes were positive. Teachers valued the approach this research took of extending the learning capabilities of capable learners in Years 12 and 13, a significant shift away from schools of deficit theorising and allocating significant resources to bringing weaker learners in Years 9–11 up to a passing level. The teachers recognise that Year 12 may be too late to engage students in independent learning practices that would help them more successfully transition into tertiary education, and thus saw a greater focus of scaffolding literacy and independent learning development across the secondary curriculum as desirable:

So we’ve made sure that in our programmes this year we have quite a focus on literacy. We’re looking at scaffolding it up from the Year 9 to the Year 10, 11, 12 and 13 levels by giving students more support with resources at Year 9 and taking away that support as they go up further in the school.

It’s given a bigger picture view of what’s going on instead of getting caught up in the individual units or the individual assessments. We have started to view it from the skills that we’re building into them at Year 9 or 10, the different skills they need to access and engage with texts, and that it doesn’t end with Year 13. We are now preparing them for going on and beyond that—whatever that might be. But if you take that bigger view picture, then it does support, justify, having the tough love approach. The bigger picture, preparing them for wherever they might go, ends with them being able to deal with more complex things and having the skills to approach it by themselves, so once they leave school they can do it without you.

This school wide approach to literacy, and the gradual reduction of teacher support, is perhaps the most significant outcome of this project.

3.2 The students

Engaging students in this process was important for determining their approaches to literacy and learning under NCEA and understanding their apprehensions about entering tertiary study. We had two key aims with students: changing their literacy attitudes and expectations, and determining the value of engaging with peer tutors to understand ‘real’ university demands and experiences.

3.2.1 We achieved changed literacy attitudes and expectations

While our teachers had been of the view that students were not motivated to read and write, one of the outcomes of students’ academic induction days and discussions with peer tutors was that students took on board messages around what they needed to do to transition successfully into tertiary learning. Key themes that emerged from student feedback on the university visits and in follow-up interviews included:

- The need to actively pursue opportunities to increase the amount of writing and reading they engaged in. Students understood the importance of these activities if they were to succeed in the tertiary sector and were motivated to change their behaviour.

think I just learnt that I need to be able to do certain things, like issues with my writing because as I said I haven’t always been writing or doing topic sentences and things like that and I took that away and have been putting it into my work. I really need to practise how I’m writing and the things that I’m putting into my writing to make sure it’s correct.

- The need to develop better study skills including note-taking:

I found it quite hard to write down what [the lecturer at the academic induction day] was saying or whether to focus more on what he was showing us on the board. <

- The recognition that university is vastly different to secondary school learning contexts:

The chemistry lecture was quite a bit different to what we experience at school. The information that we received we had to pick what we thought was the most important but it wasn’t just coming from one source, we had to like look at the power-point, look at the whiteboard and listen to the lecturer. It was quite challenging because on the power-point it was kind of just like brief outlines and then when he was talking he would explain more, go into more depth so occasionally while we were still writing down stuff he was at the same time speaking.

- The importance of becoming an independent learner and putting in more effort:

It was like people who were taking us they were there but at the same time we had to assess for ourselves, you know, when we came across information and stuff whether this was really what we were looking for.

You have to remember that University is a step up from school; it’s not something that’s going to be easy and that it’s definitely something that you’re only going to enjoy if you put the time and effort into it.

- The value of developing information skills and utilising the vast amount of resources university libraries offer

Here at school you can use almost any source but there at [university] you had to use more trustworthy sources, like more credible sources.

They really opened my eyes up to how crucial a library is in a University, all the resources they have and they’re willing for you to use it and everything; and it’s like, it’s all for free and it’s all there to help so—and they showed us a lot of ways, easy ways, to look up the things you need and then specify into what you really need and get really onto it.

- The recognition that university is not as scary as they imagined.

I suppose it was sort of a sense of relief I guess because it wasn’t as scary as I originally thought. … I feel that I could approach the lectures and the tutorials and using the library with more confidence because I’ve learnt from experience what they’re like … Beforehand I didn’t really know what I would be getting into except there would be lots of people; but now it’s just helped put things in perspective.

I thought it was going to be like heaps of brainy people talking and all this stuff I didn’t understand, but it wasn’t as highly out there as I thought it was going to be … it was just a big eye-opener that I can do this.

In follow-up interviews with students who had started university in 2014, several reflected on what had been most useful from the academic induction days once they had entered university and had experienced a semester of learning.

Some of the research things we did at [the induction day] helped at uni. We did some referencing stuff and I found that helped because a lot of people didn’t even know about it. I felt like I had a bit of an advantage.

3.2.2 Providing a peer tutor makes a difference

One of the innovative aspects of this project was the provision of peer tutors to support transitioning students. The peer tutors were successful university students who had completed two credit-bearing papers on nondirective peer tutoring (see Brooks, 2003; Bruffee, 2008). These tutors visited schools in pairs to support (in conjunction with the teachers) the Year 13 students, and conducted Q&A sessions. These initiatives were viewed positively by the students.

They made us break down the questions and just take out the key things, what we needed to answer directly and so we could actually pass it and so working on that answer to make it merit or excellence … It worked really well. Like at the start it was sort of slow and then we built up and got more confident in saying it and getting it right and it just got better from there. And I think they really helped us, especially with our speeches we’re doing in class now; they really helped with those. [The peer tutor] said ‘I can’t wait to see what it’s like when it’s finished!’

The peer tutors reported conversations on subjects we had not anticipated, such as anxieties about university life/study:

We finished off the session by just discussing university life and answering any questions the boys had. We talked about learning to balance your study and social life … getting into halls and the universities that are the best for each programme of study. We also talked about applying for student loans and the types of scholarships that they should apply for. I think this was the part that interested the boys the most! We were really just trying to demystify university life, as some of the comments some of the students made during the session (such as: ‘is university really hard?’ and ‘it seems so hard, you might as well not try’) showed that some of the boys were quite worried about how they would find the transition.

A strength of the peer tutor initiative was that the tutors were close to the school students’ age, could remember their own anxieties, and could reassure from the perspective of their own experience:

… many high school students are unaware of what is expected of them at university still and they seemed to be quite scared. However, by talking about our own experiences the students seemed to realise that they could do it.

Student anxiety regarding the transition to university was a recurring theme in the peer tutors’ feedback on sessions. One session with the peer tutors took place the day after the academic induction day, and peer tutors commented on student anxiety related to that experience, giving us information on which to base a follow-up strategy:

the students wanted to discuss their academic induction day which had taken place the day before. They seemed to have really enjoyed their day especially the lecture. A few were still concerned about their note-taking skills and the level of work expected from them. The visit seemed beneficial to the students but perhaps a follow-up is needed as the students still seemed to have a lot of questions.

Finally, non-directive tutoring is designed to focus on the skills and knowledge of the student and enable them to make decisions about writing. Further, it enables effective literacy tutoring by tutors who are not disciplinary experts. The following is a description of one of the peer tutors, an English major, working with a group of physics students using non-directive strategies:

I asked the group how they would like to approach the assignment and we all decided that it would be a good idea to begin brainstorming. We went through all of the physics principles, but instead of one person doing all of the talking I encouraged that each person would discuss one specific principle themselves. This way I thought that everyone would become involved and challenged simultaneously. Once we had gone through all of the physics principles, we then applied them to fluid filled glasses. Some of the physics principles voted for the fluid filled glasses to go ahead and others voted against. What was so great to see from this somewhat individual/group brainstorming exercise is that each student fought for their specific principle and why or why not it could be related to the fluid filled glasses. After we had done this exercise we decided that we would begin to think about a thesis statement that embodied the physics principles that related or did not relate to fluid filled glasses. The students had been practising thesis statements and I asked them to do a practice one for me and then I asked them to read them out loud. All of them were fantastic!

Using non-directive peer tutors to support students in their writing proved to be an effective way of building student confidence for the transition in multiple ways.

Some of our peer tutors continued to support our transitioning students in their first semester of tertiary study, by email and text. Students who had this support valued the familiarity in a time of transition:

It was really helpful because she would help me out if I was getting stressed out, but mainly I would send her my completed draft and she would give me feedback and I would fix it. It was really useful having someone familiar to go to and it was a good way to learn how to proofread.

By the end of the semester, this need for support had reduced, and the peer tutors were no longer needed.

Another interesting outcome of the peer tutoring was that those students who went to institutions where Peer Assisted Study Support (PASS) initiatives were in place indicated they engaged fully in this process. When asked if they would have engaged with PASS without the prior tutoring initiative, a typical response was:

I would say that [peer tutoring at school] did encourage me to join the PASS classes as I had already experienced working with older students and found their experience helpful to my learning.

3.2.3 Making the transition remained difficult

While we were able to show that the changes we made through the project had an impact on student confidence and motivation in relation to the literacy transition, the lived reality remained challenging for some students. Although all students indicated they were enjoying university and feeling more confident at the end of the first semester, key challenges they faced initially connected to:

- being away from home

- managing workload (particularly time management and the volume of reading)

- one shot at assessments

- lack of teacher support and intimidating lecturers

- class sizes, classroom contexts and unclear standards of quality

All students felt they could offer advice to incoming students to help them realise that difficulties are not insurmountable and university is worth it. The following excerpt captures common themes in student responses to encouraging Year 13 students to enter higher education:

Definitely pick subjects you want to be doing because otherwise you’re going to struggle or won’t enjoy them, and have a future purpose that you want to strive towards. Just know that you can do it, and your first year is all about learning and adapting, and that the grades that you get don’t define what you’re going to be able to do in the paper. If you try hard enough, you’ll be able to achieve what you want to do. Just enjoy it. Instead of stressing about your essays, do lots and lots of research, find out how interesting it is, really enjoy the topic, and then we’d find the essay would just flow. Just invest yourself in it and actually do the research.

3.3 The tertiary sector

3.3.1 Some of our plans did not come to fruition

Our original plan had been to report on our findings to a range of tertiary institutions and to recruit tertiary teachers as researcher–participants in year 2. We planned that tertiary researcher-participants would analyse their courses in the light of the findings of year 1 of the project, the literature on the first year experience, and literacy good practice, and revise assessments and pedagogical practices.

Attendance at the workshops was higher than anticipated, demonstrating that there was a high level of interest in literacy and cross-sector discussions. Similarly, in year 1, when we approached tertiary teachers to engage in specific activities (e.g. taking part in the student visits, meeting with literacy leader, and sharing assessment activities), we had a 100 percent uptake. Tertiary teachers were keen to engage with the Year 13 students and their teachers. Those who worked with the teachers/literacy leaders found the experience to be a very positive one: discussions went on for longer than scheduled and led to a very fruitful dialogue.

However, no tertiary teachers volunteered to engage with the project more fully in stage 2. The reasons for this are unclear. This is explored further in section 3.5.

What we were able to achieve was wide dissemination of our findings and education about NCEA and NZC to the tertiary sector. Interviews with university teachers showed that, prior to our work, teachers in the university sector in particular were both uninformed and misinformed about NCEA. However, some of the problems that university teachers identified in their classroom and attributed to NCEA were confirmed by our findings as related to the way NCEA is delivered in classrooms. These included:

- gaps in students’ discipline knowledge base

- concerns about multiple opportunities to resubmit assessments at school

- students’ lack of study skills

- students’ inability to critically evaluate and engage with multiple texts

- student approaches to learning

- students’ over-reliance on models.

Nevertheless, the two key issues that we would identify in relation to tertiary teachers are these:

- Tertiary teachers do want to know more about senior secondary teaching and learning. There are, however, no obvious mechanisms by which they can be informed (other than family experience).

- There is reluctance to engage in transition learning strategies amongst tertiary teachers.

To enable effective transition, we would argue that these two issues need to be addressed.

3.4 Resources and sustainability

3.4.1 The ANCIL rubric

We identified the need for a resource that would enable students to assess their readiness for tertiary study, teachers to develop appropriate resources and curricula, and researchers to measure the success of teachers’ literacy strategies in terms of student preparedness for academic literacy. Hence, we developed the key resource output from the study: an information and academic literacy self-awareness rubric entitled: Are you ready? An academic literacy self-assessment tool to help you transition into tertiary learning. The rubric was designed to highlight key literacy competencies students entering higher education would be expected to develop through scaffolded instruction and independent learning experiences.

Key considerations in design included:

- identifying four key competency areas aligned with ANCIL framework, based on conversations with teachers about which strands they could actively embed in their classrooms

- integrating goal setting into the document to allow for discussion with teachers around improving areas of identified weakness

- using appropriate language for Year 12/13 students.

The rubric went through several stages of design, trial and implementation.

- Designed—on the basis of ANCIL and teacher conversations related to the curriculum.

- Tested—teachers were asked to complete the rubric and provide feedback on wording, structure, repetition.

- Modified—teacher feedback was used to refine the rubric and produce the final version distributed to the participating schools.

- Implemented—the rubric was completed in schools and sent them back for analysis

- Calibrated—teachers were asked independently to assess students, as a comparative measure. In most cases, the teacher and students responses aligned.

- Analysed—the analysis revealed categories we had not considered: personal preference, skill, cognitively demanding task. Data are still under analysis.

In addition to feedback from the participating teachers, the rubric was presented to staff at other schools/ tertiary institutions during presentations around the country. The rubric is now being refined based on this feedback. We are beta testing methods of analysis and investigating ways to create an electronic version and allow for wider distribution to New Zealand secondary schools and, potentially, tertiary institutions.

3.4.2 Sustainability

The programme with secondary teachers was designed to be both sustainable in the schools we worked with and able to infiltrate more deeply into those schools through the work of the literacy leaders. Year 2 was particularly important here as the literacy leaders engaged with the wider school community to effect change. Furthermore, we disseminated our findings through workshops and publications targeted at the secondary sector, and we have a book contract with NZCER to enable us to reach more deeply into the sector. The ANCIL rubric is a substantial tool that can be used in schools and tertiary institutions alike and we are working with the TLRI and Ako Aotearoa to refine the tool and make it widely accessible.

One further question of sustainability concerns the use of peer tutors. The peer tutors were an important part of building student confidence and motivation, especially those who were first in family or unfamiliar with university life. However, it is unclear how this aspect of the project could be sustained and who should take responsibility for this. Our recommendation is that tertiary institutions might see training and providing peer tutors as an effective way of both preparing potential students for the transition and recruiting students. This would be a cost, but it would reduce the need for costly (and potentially less effective) academic literacy support and the costs associated with failures in retention. If this aspect of the project is to be sustained, another resource that needs to be developed (and could be developed by our team) is a training manual for peer tutors.

3.5 Limitations

There were a number of limitations to our study:

Lack of tertiary engagement: As already stated, although tertiary teachers showed a great deal of interest in our research, we were unable to find tertiary teachers who were willing to engage fully with the research. One possible reason for this is that teaching-based research is not prioritised by tertiary teachers in relation to PBRF, or that systemic issues (such as the long planning time for changes in assessment to be approved through centralised systems) made research that involved changes to assessment too challenging. Alternatively, tertiary teachers’ beliefs and attitudes to literacy may have deterred their engagement with the project: if they see literacy as generic and transferable, they may see no need to teach skills they view as remedial. Future studies are needed to examine tertiary teacher literacy-related attitudes and beliefs.

Difficulties in maintaining contact with students: Although the majority of students who engaged with the project agreed to continue with the research through their first year of tertiary study, and expressed strong interest in maintaining the support of their peer tutors through the transition, only a small number of students retained their connection with the project in year 2. We have not, therefore, been able to ascertain fully the impact of the project on transition. This lack of sustained engagement of students may be attributable to a number of factors: perhaps tertiary study and living was so all-consuming that they didn’t have time or sufficient support available through their tertiary institution to meet their needs. The students who did stay in contact provided positive feedback on the project, but future studies do need to find ways of staying in contact with students through the transition.

Generalising the findings: This research was focused on small low-mid decile schools, with a poor history of transition to tertiary study but with high aspirations for their students. The consistent results across the schools suggest that our findings are applicable to schools with a similar profile. However, it would be useful to see if similar strategies would be equally effective in large, urban schools. We are of the view that the use of the ANCIL transiting matrix, in particular, as a diagnostic tool for teachers, would benefit all schools.

4. Conclusion

This research has major implications for practice in terms of the transition students make between school and academic literacy in New Zealand education. Our research has demonstrated that there are systemic problems related to integrating literacy into the curriculum which relate to secondary teachers’ academic and professional self-concepts, perceived accountability pressures associated with NCEA achievement, and insufficient attention given to strategic information and academic literacy instruction. In identifying and addressing those issues, we demonstrated that adopting a pedagogic literacy pathway in senior secondary school and familiarising secondary teachers with the tertiary environment can, at least in part, enable a more efficient transition to tertiary study.

Furthermore, familiarising students with the literacy and independent learning requirements of tertiary learning can shift their attitudes to literacy. When students see the need for more reading and writing, and teachers recognise the need to develop students’ independent literacy skills, change can happen. With support, particularly through the use of the ANCIL framework, teachers can be assisted to overcome their own anxieties around accountability, stop over-managing their students’ learning, and still be confident of results. The outcome is students who are more prepared for tertiary learning through increased academic literacy, improved independent learning skills, and greater familiarity with the expectations of life in a tertiary institution.

However, our research also showed that, for a fully effective transition, change is needed in the tertiary sector— and achieving that change proved beyond the capacity of this project.

5. Recommendations

Our research indicates the following:

Secondary schools

- There is a need for in-service PLD for senior teachers of text rich secondary school subjects focusing on contemporary academic and information skills teaching within the NCEA context, using the ANCIL framework.

- Pre-service programmes should introduce compulsory instruction in literacy pedagogic content knowledge required for effective instructional practice.

- Measures should be taken to promote NCEA as a qualification that requires teachers to explicitly instruct students in the processes that nurture critically literate thinkers in disciplinary settings, reading and writing skills at advanced academic levels for academic success, and efficient and effective researchers.

- Further exploration is needed into ways to promote the flexibility of NCEA as a tool within which teachers can plan safely for programmes of learning in the context of annual accountability and performativity protocols.

Tertiary institutions

- A mechanism for educating tertiary teachers about the NCEA and the NZC is needed.

- More pedagogical consistency is needed across the sectors.

- Tertiary institutions need to actively engage with their catchments’ secondary institutions, beyond promotion, recruitment and induction days, in order to reach common understandings about each other’s educational setting, pedagogic practices, expectations and academic demands.

- Tertiary institutions consider using academic induction and peer tutors as a way of supporting transitioning students who are at risk (e.g. first in family) during the senior secondary school years.

Across sectors

- At a policy level, a smoother transition between sectors needs to be considered. We recommend the use of the ANCIL framework to achieve this.

- At a local level, we need to find new ways to bring schools and tertiary institutions together, to share information, expectations, practices and pedagogy.

Research

- Further investigation into teacher identity, attitudes and beliefs related to literacy is needed across sectors.

- Further research is needed to extend the methods of this research into a broader range of schools.

- Further research into the ANCIL framework as a way of enabling transition is needed, particularly within the tertiary sector.

- Future research is needed to extend our findings into the tertiary sector.

Footnotes

- This project was also designed to support government literacy intentions through the realignment of the NCEA. The realignment of NCEA Levels 2 and 3 (of the NZQF) to levels 7 and 8 of the New Zealand Curriculum (2007) has reinforced government’s commitment to students’ academic literacy knowledge and skills, requiring students to apply a range of written literacy skills and strategies to produce short answer paragraph and essay responses in accordance with the academic disciplinary conventions. There is an explicit requirement for students to demonstrate evidence of deeper critical understandings and analysis of text and information. Our project emphasised the simultaneous learning of strategic approaches to academic literacy, of the conceptual knowledge that underpins its contextual practice, and the need to build students’ capacity to think critically and deeply about and with text. ↑

- The distinction between academic literacy and academic writing skills pedagogy is best illustrated through an example: a core issue in writing for tertiary study is referencing/plagiarism. Using an academic writing skills pedagogy, students would be taught how to avoid plagiarism, how to use in-text citations and construct a reference list; the motivating factor for students using an academic writing pedagogy is avoiding plagiarism and penalties. Academic literacy pedagogy, in contrast, considers why these issues matter: it examines the nature of information literacy, what constitutes knowledge (and how it is constructed), how the discipline uses information, and how students can find a voice while managing disciplinary conventions. In an academic literacy framework, students not only learn skills of academic referencing, but they understand why they matter. ↑

- For a description of PAR in action in an educational context, see Kane, 2014 or Feekery & Emerson, 2013), ↑

References

Bartholomae, D. (2005). Writing on the margins: Essays on composition and teaching. Boston: Bedford/St. Martins.

Bazerman, C. (Ed.). (2007). Handbook of research on writing: History, society, school, individual, text. New York: Routledge.

Brooks, J. (2003). Minimalist tutoring: Making the student do all the work. In Murphy, C., & S. Sherwood (Eds.), The St. Martin’s sourcebook for writing tutors (2nd ed.) (pp. 169-174). Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s.

Bruffee, K. (2008). What being a peer tutor can do for you. Writing Center Journal, 28(2), 5-10.

Emerson et al. (2005). Scaffolding academic integrity: Creating a learning context for teaching referencing skills. Journal of University Teaching and Learning Practice, 2, 3a.

Feekery, A., & Emerson, L. (2012). Promoting information literacy development by assessing the research process in first-year tertiary assessments. Proceedings of the Symposium on Assessment and Learner Outcomes, p. 111. Retrieved from: http://www.victoria.ac.nz/ education/pdf/jhc-symposium/Assessment-Learner-Outcomes-2011-Symposium-Proceedings.pdf

Fishman et al. (2005). Performing writing, performing literacy. College Composition and Communication, 57(2), 224–252.

Kane, R. (2014). Systemic action research: Changing system dynamics to support sustainable change. Action Research, 12: 3–18.

Kilpin, K., Emerson, L. & Feekery, A. (2014a). Information literacy and the transition to tertiary. English in Aotearoa, 83, 13–19.

Secker, J. & Coonan, E. (2013). Introduction. J. Secker & E. Coonan, E. Rethinking information literacy: A practical framework for supporting academic literacy. London: Facet Publishing

Shanahan, T. & Shanahan, C. (2008). Teaching disciplinary literacy to adolescents: Rethinking content-area literacy. Harvard Educational Review, 78(1), 40–59.