Introduction

Background, research literature overview, research questions and why they are important to learning and teaching in New Zealand

Aotearoa is an increasingly diverse society. The many languages and cultures of children and families raise questions and considerations for early childhood teachers. We designed research to address gaps in our knowledge, by exploring the languages used and the experiences and learning outcomes that parents, teachers, young children and communities value. Our focus was on children who learn in more than one language in the early years. The research was credit-based, through our application of the theoretical constructs of funds of knowledge and an additive approach to learning through more than one language.

An additive model of bilingualism emphasises the capability of young children to learn effectively in more than one language when this is adequately resourced and supported (Cummins, 2001a, 2001b, 2009; Garcia, 2009). An additive approach occurs in an educational setting where the heritage/home languages (or community or first languages) are acknowledged and not replaced by additional languages. In contrast, subtractive bilingualism occurs where the additional language (for example, English) replaces the first or heritage language. Subtractive bilingualism is assimilationist and may lead to the loss of heritage/home language and culture.

Funds of knowledge is a credit-based notion of everyday knowledge found in families, communities, and cultures.Consistent with sociocultural approaches, “the concept of funds of knowledge is based on a simple premise:People are competent, they have knowledge, and their life experiences have given them that knowledge” (González, Moll, & Amanti, 2005, p. ix). A funds of knowledge theoretical lens, applied to bilingual children and households, emphasises the need for teachers to extend their understanding of children’s diverse learning experiences in their homes, families, communities and cultures (Hedges & Cooper, 2014; Moll, 2000).

In this report we signal the plurilingual nature of children’s and teachers’ learning and teaching experiences. Plurilingualism introduces a dynamic view of bilingualism in educational settings and refers to an individual’s ability to draw upon her/his total language resources for learning and teaching (Cummins & Early, 2011; Garcia & Kleifgen, 2010). Plurilingual activity occurs in any environment that encourages and validates the complex and interrelated linguistic repertoires and practices that each child/adult can use to engage with others in that particular context or community (Garcia & Wei, 2014). A plurilingual environment in an early childhood centre context is generated by teachers, families and whānau where children and teachers feel empowered to use their heritage/home languages for learning and teaching.

Learners in Aotearoa/New Zealand are increasingly likely to speak more than one language. This nation-wide trend is most evident in the Auckland region (Morton, et al., 2014; Statistics NZ, 2006, 2013). Accordingly, this study collated and reported data that illustrate the diversity of the language experiences of children and their families from four early childhood centres within the Auckland region. The primary focus was on children aged from birth to 5 years who participated in early childhood education (ECE) centres, their teachers, and their families.

Our four participating partner centres represented the languages most prevalent within the Auckland region: English, Māori, Samoan (and Pasifika languages), Hindi and Mandarin. The centres were: (1) Te Puna Kōhungahunga, a Māori-medium centre; (2) The A’oga Fa’a Samoa, a Samoan-immersion centre; (3) Mangere Bridge Kindergarten, an English-medium kindergarten with families who spoke Pasifika, Asian and European languages; and (4) Symonds Street Early Childhood Centre, an English-medium centre with families who spoke a wide range of Asian, Middle Eastern and Pasifika languages.

We designed this research to advance knowledge and practice in the field of children learning in more than one language in the early years. There were three overarching research questions:

- What languages do children from participating ECE centres use in their learning in the centre and at home?

- What experiences and outcomes for children who learn in more than one language in the early years are valued by parents, teachers and children?

- How might the opportunities and challenges for children who learn in more than one language be addressed in educational practice?

These research questions were important, given that languages and literacies are key cultural tools for learning and teaching (Vygotsky, 1978) in early childhood centres, homes and communities. For some time, researchers have reported that there are gaps in our knowledge concerning children who learn in more than one language. In particular, Meade (2010) noted the need for ECE centre-wide data. One practice that needed addressing more widely was superficial attention to culturally responsive pedagogies (Cowie, et al., 2011). Cummins (2009) noted that teachers have an ethical responsibility to understand the role of languages and cultures in children’s learning. Cross-generation transfer of languages is a goal for many families, for example, from fluent grandparent to children, or from children participating in an immersion setting to their parents (McCaffery & McFall-McCaffery, 2010; Tuafuti, 2010). Therefore, the research questions we addressed were timely and the issue that required attention was attending to linguistic responsiveness alongside cultural responsiveness.

Research design

Design, methods, and approaches to analyses

This was a multi-method design incorporating questionnaires, focus groups, child interviews and observations, across each of the four ECE centre settings. We used a range of quantitative and qualitative methods to address the research questions and to obtain rich data about valued experiences, outcomes, opportunities and challenges associated with learning in more than one language.

By applying funds of knowledge and an additive approach to learning in more than one language, this research was overarched by a “transformative–emancipatory paradigm for mixed-methods research” (Siraj-Blatchford, 2010, p. 202). The methodology was primarily inductive, and the research design was collaborative and iterative (Penuel, Fishman, Cheng, & Sabelli, 2011).

The study’s methodology was consistent with sociocultural theories that influence Te Whāriki, the New Zealand early childhood curriculum (Ministry of Education, 1996). Sociocultural researchers have shown links between language, identity and cultural practices (Rogoff, 2003). The four partner centres comprised a collaborating cluster of ECE centres, so this project was a case study in four settings (Yin, 2014).

Data generation tools and procedures

We compiled census data from the March 2013 census to provide information about ethnicities and languages used, to situate the research in its wider demographic context and explain further its timeliness and relevance to policy and practice.

Our team administered questionnaires for parents and teachers to generate, collate, and analyse data on the languages spoken by children, parents, and teachers; and on the valued learning experiences and outcomes for young children who learn in more than one language. We adapted several items from questionnaires that a research programme had used previously to explore te reo Māori use in the home (Keegan, Trinick, & Morehu, 2009).

Observations, carried out by the teacher–researchers, included field notes of, and reflections on, children’s and parents’ arrivals and departures. Thereafter, the teacher–researchers’ observations in centres focused mainly on making and reflecting on video clips of children’s, teachers’, whānau and community members’ interactions and the languages used during learning experiences.

Teacher–researchers also recorded video clips of a “mat time”, that is, a group activity involving teacher/s and children that normally and naturally happened in their centres. The “mat time” video clips were used to trial the software: Human Behaviour Analysis Observer XT 12.5 to analyse excerpts of child–teacher interactions and experiences valued by teachers and parents. Scrutiny of our initial video data had suggested that Observer XT’s usefulness, accuracy and consistency would be limited to learning and teaching contexts where a group of children and teachers remained in the same place together.

Researchers and teacher–researchers collaboratively held focus group interviews with teachers and parents separately in each centre (i.e., eight focus groups). These occurred in English, Māori, or Samoan, as appropriate.

Teacher–researchers also undertook short interviews with older children who were learning in more than one language, to discuss their experiences. The focus was on each child’s languages and valued learning experiences, and generally took the form of a discussion with the child about her/his portfolio. Teachers’ assessments including narratives, team curriculum documentation and learning stories (Carr & Lee, 2012) supplied further in-depth data on children’s learning experiences and outcomes.

Data analyses

We tabulated 2013 census data to display the relevant trends for ethnicities and languages used in Auckland and throughout New Zealand. The research team used the statistical package R to analyse responses to the questionnaires, entered the data for each item into Microsoft Excel spreadsheets, and computed descriptive statistics. We then generated and presented graphs, using the R package ggplot2, via RStudio to illustrate the questionnaire findings related to research question 1, and transferred the responses to open-ended questions to spreadsheets in order to facilitate further scrutiny and reflection on the data in relation to research questions 2 and 3.

Focus group analyses involved searching the teacher and parent focus group transcripts for key themes, under each of the three overarching research questions. Teacher–researchers sorted the transcribed child interview data under each of the three research questions. These transcriptions were translated into English.

Teacher–researchers selected, from the wealth of video data generated, a series of video clips that they considered most relevant to the research questions and illustrative of the experiences valued within their centres. The teacher–researchers sorted the transcriptions of these video clips and identified pertinent excerpts that illustrated key points or themes emerging from the research. Finally, we trialled the usefulness of Observer XT, by analysing short video clips of “mat times” from each centre.

Ethical considerations

Prior to commencing any data generation, we obtained ethics committee approvals. We submitted ethics applications to the Human Ethics Committee of the University of Auckland, and to the Auckland Kindergarten Association Research Ethics and Access Committee in relation to Mangere Bridge Kindergarten’s participation. Voluntary participation and confidentiality were important considerations. At each centre, parents received an information letter, together with a consent form that included specifying consent for video recording of their child. The focus of video recordings was on positive aspects of learning in more than one language. The research team members were also aware that it is “essential to exclude or erase non-consenting persons from the recording or picture” (Podmore, 2006, p. 94).

Census data findings

Data from the New Zealand 2013 census provided evidence of ethnic diversity, particularly within the Auckland region where European, Māori, Pasifika people and Asians are the most prevalent groups. Table 1 shows that notably high proportions of the country’s Pacific peoples and Asians reside in Auckland.

| Ethnic Group | Auckland | New Zealand | Auckland as a proportion of NZ | ||

| Count | % | Count | % | % | |

| European | 789,306 | 59.3 | 2,969,391 | 74.0 | 26.6 |

| Māori | 142,767 | 10.7 | 598,602 | 14.9 | 23.9 |

| Pacific Peoples | 194,958 | 14.6 | 295,941 | 7.4 | 65.9 |

| Asian | 307,233 | 23.1 | 471,708 | 11.8 | 65.1 |

| Middle Eastern/Latin American/African | 24,945 | 1.9 | 46,956 | 1.2 | 53.1 |

| Other | 15,639 | 1.2 | 67,752 | 1.7 | 23.1 |

| Total People specifying ethnicity | 1,331,427 | 110.8 | 4,011,402 | 111.0 | 33.2 |

| Not elsewhere included | 84,123 | 230,646 | 36.5 | ||

| Total People | 1,415,550 | 4,242,048 | 33.4 | ||

The languages spoken most widely throughout New Zealand, as recorded in the 2013 census, are: English, Māori, Samoan, Hindi, and Northern Chinese (Mandarin). In Auckland, there is a high concentration of Hindi, Northern Chinese and Samoan speakers (see Table 2).

| Language | Auckland | New Zealand | Auckland as a proportion of NZ | ||

| Count | % | Count | % | % | |

| English | 1,233,633 | 95.6 | 3,819,969 | 97.8 | 32.3 |

| Samoan | 58,200 | 4.5 | 86,406 | 2.2 | 67.4 |

| Hindi | 49,518 | 3.8 | 66,312 | 1.6 | 74.7 |

| Northern Chinese | 38,781 | 3.0 | 52,263 | 1.3 | 74.2 |

| Māori | 30,927 | 2.4 | 148,395 | 3.8 | 20.8 |

| Yue | 30,681 | 2.4 | 44,625 | 1.1 | 68.6 |

| Sinitic not further defined | 30,282 | 2.3 | 42,750 | 1.1 | 70.8 |

| Tongan | 26,028 | 2.3 | 31,839 | 0.8 | 81.7 |

| Korean | 19,365 | 1.5 | 26,373 | 0.7 | 60.8 |

| French | 17,433 | 1.4 | 49,125 | 1.3 | 35.5 |

| Tagalog | 14,925 | 1.2 | 29,016 | 0.7 | 51.4 |

| Afrikaans | 13,992 | 1.1 | 27,387 | 0.7 | 51.1 |

| Total People Stated | 1,316,262 | 134.1 | 3,973,359 | 101.7 | |

The number of Hindi speakers increased markedly between the 2006 and 2013 census. In 2006 there were 34,614 Hindi speakers in Auckland, but by 2013 there were 49,518, an increase of 43 percent.

Of concern is a consistent decrease in te reo Māori speakers in New Zealand. The number of te reo Māori speakers decreased by 12,132 between 2001 and 2013, with a decrease of 8,715 between 2006 and 2013. Reversing this trend will be an urgent challenge for teachers, families, and policy makers.

Findings across the partner centres

Ethnicities and languages spoken

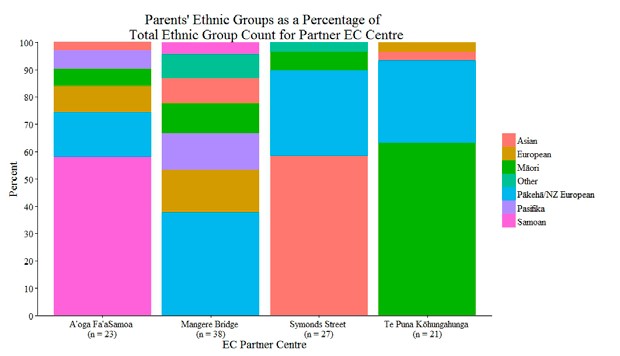

Quantitative analyses across the four centres yielded patterns of data on parents’ reported ethnic group identities. There was a range of reported ethnicities at all centres, most notably at Mangere Bridge Kindergarten and also at Symonds Street Early Childhood Centre. Predictably, Māori were in the majority at Te Puna Kōhungahunga, and Samoans were prevalent at the A’oga Fa’a Samoa. Figure 1 shows parents’ ethnic groups(s) as a percentage (of total ethnic group count) for each partner early childhood centre.

Figure 1.

Note: The percentages given in Figure 1 are the percentages of the total number of ethnic groups identified in each EC centre. For example, at Te Puna Kōhungahunga, n = 21 (parents), ethnic groups identified by those 21 totalled 30 (i.e., 30 tokens) (19 of those 30 are Māori, so = 63.3 %). Percentages in Figure 1 (for comparison purposes) are percentages of the total number of ethnic groups (tokens) identified for that EC centre.

Almost all parents responding to the questionnaires reported that they spoke conversational English. A wide range of spoken languages was evident among parents at Symonds Street Early Childhood Centre and Mangere Bridge Kindergarten.

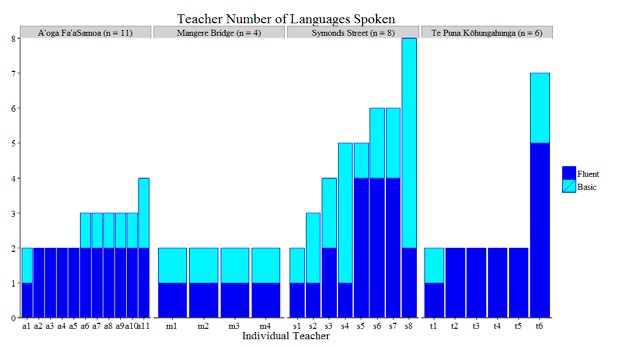

The number of languages spoken by individual teachers varied across centres (see Figure 2). For example, at Symonds Street Early Childhood Centre (s) most teachers spoke several languages and several were fluent in multiple languages, whereas at Mangere Bridge Kindergarten (m) the four permanent teachers were fluent in English only. Kaiako (teachers) at Te Puna Kōhungahunga (t) were almost all fluent speakers of te reo Māori, and faiaoga (teachers) at the A’oga Fa’a Samoa (a) were almost all fluent speakers of Samoan. We were able to code and present individual teachers’ multiple languages.

Figure 2.

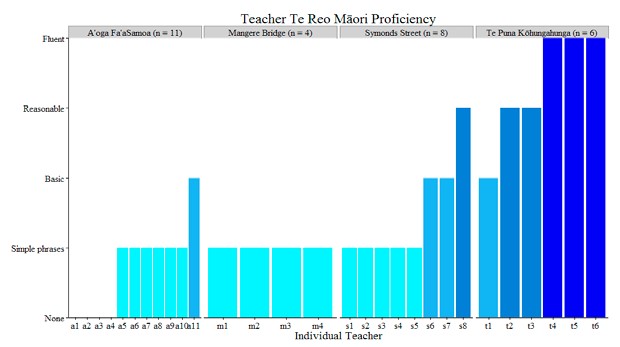

Where possible, we are reporting on te reo Māori proficiency because of the bicultural imperative of Te

Whāriki. As might be expected, teachers reporting proficiency in te reo Māori was most prevalent at Te Puna Kōhungahunga. Further, within all centres, almost all teachers reported that they spoke at least simple words and phrases in te reo Māori (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Observer XT analyses

Observer XT proved effective to quantify and reflect on patterns of events, behaviours, activities and specific language/s used, as captured by digital video recordings. Our team explored using Observer XT to code spoken language and interaction patterns across similar events recorded at all four partner centres. Teacher– researchers from each centre selected a 3-4 minute video clip of group time/mat time from their video data collection. Each clip was selected as representative of the centre’s customary group time activity and accompanying contextual information and translations were provided.

We coded spoken language use according to the language used, type of language or function of language used, and the speaker(s). Language use is generally mutually exclusive and was readily coded for a particular language (e.g., Māori, Samoan, English, Hindi), or for mixed (and sometimes undetermined) language where one language is being used with vocabulary or phrases from another language. The speaker may be either an individual, for example, teacher, parent, or child, or a group such as everybody saying a greeting or singing a song. It was generally straightforward to classify the use of languages that were not the language of instruction in an ECE centre, as this was often restricted to songs, greetings, high frequency words or phrases such as animals, people terms, days of week, and colours.

This set of coded analyses focused on languages yielded information about the languages spoken by the children in the centre (research question 1). We used an Observer XT coding scheme to analyse language across all four partner centres. Not surprisingly, very different patterns of language were used, even when undertaking a similar type of event such as mat times. In the A’oga Fa’a Samoa and Te Puna Kōhungahunga children and teachers used very little language outside their respective target languages of Samoan and Māori. Participants at both Mangere Bridge Kindergarten and Symonds Street Early Childhood Centre used a wide range of languages but with very restricted functions.

We also adapted the coding categories designated for coding types of interchanges and illocutionary forces(intentions and effects of interchanges) between child and teacher from the Inventory of Communicative Acts—Abridged (INCA-A) scheme proposed by Ninio, Snow, Pan and Rollins (1994). This coding system takes as observational focus the function of the communicative language, and the verbal and non-verbal interactive behaviours and intentions of speakers and listeners.

A short example of the many types of codes that may be used is presented in the following summary.

| Teacher or child interchange type codes (Visuals or actions) |

Eliciting code | Clarification code |

| DJF discuss joint focus

NIA negotiate into activities or roles NMA establish mutual attentiveness PRO perform moves/activities or parts of games MRK marking (this includes praise) |

AC answers call to | CL Call attention to hearer by name |

Observer XT allowed the classification of interaction types, frequency and durations. It also allows the comparison of interaction types between participants (such as teachers and children). Interaction types can be compared within both similar partner centre activities and across the four partner centres. Interactions can also be classified and analysed by language use.

Our research team identified both strengths and limitations associated with use of Observer XT in ECE settings. Observer XT has extremely powerful analytical capabilities. It does have a steep learning curve and works better with videos that effectively capture all speaker activities. Coding of interactions and language use is very laborious and time consuming. The visual coverage of all children interacting with their teacher/teachers was constrained by the use of a single camera, but audio tracking was possible for all talk and exchanges. Restricting the use of Observer XT to mat times would be considered a limitation within early childhood settings. Overall however, within these specific constraints, Observer XT was useful for quantifying observations, reflecting on patterns, coding interactions, and determining the duration of interactions in target languages.

Findings within four partner centre settings

Findings from each of the four partner centres are summarised here to answer the three overarching research questions.

Te Puna Kōhungahunga

Centre context

Ko te manu e kai ana i te miro, nōna te ngahere

Ko te manu e kai ana i te mātauranga, nōna te ao

The bird who feeds from the miro owns the forest

The bird who feeds off knowledge claims the world.

Te Puna Kōhungahunga is a Māori-medium early childhood centre based at the Epsom campus of the University of Auckland. It is a mixed-age centre, with 53 tamariki enrolled at the time of data collection, and eight permanent, fulltime kaiako (teaching staff). The centre’s philosophy of whanaungatanga is linked directly to the above whakataukī. The kaupapa is whānau driven to enable tamariki mokopuna to be confident, capable, and competent ki te taha Māori me te taha Pākehā (bilingual and bicultural learners). Kaiako described the centre curriculum as diverse, practical, and ultimately holistic in the sense that the many regular activities include: hīkoi maunga, swimming, hosting and attending pōwhiri, and attending annual noho marae. Te Puna Kōhungahunga leadership and management have been consistent and strong for the past decade, with a centre manager who has built extensive relationships in Auckland, Aotearoa and overseas. These relationships were not restricted to early childhood; they extend across many communities and disciplines and were nurtured continuously, with many of the centre whānau remaining involved directly or indirectly with the centre.

Research participants

Six teaching staff at Te Puna Kōhungahunga completed questionnaires and participated in the kaiako focus group. Five whānau (parents) participated in the whānau focus group, representing four tamariki (both parents of one child participated). Of the people present at the whānau focus group, past whānau were represented by both the facilitator and the recorder. As an icebreaker for the participating whānau, the facilitator and recorder spoke about their own children’s experiences at Te Puna Kōhungahunga and how these influenced their own journeys with te reo Māori.

In addition to compiling their usual learning story portfolios, kaiako chose 20 tamariki to revisit photographs about their learning experiences and situations, thereby eliciting further kōrero about learning. This process provided one-to-one time with tamariki, with opportunities to build confidence and trust among several less vocal/confident children.

Languages spoken by the children in the centre and at home

Research question 1: What languages do children from participating ECE centres use in their learning in the centre and at home?

All kaiako spoke te reo Māori, with varying degrees of fluency. Teacher questionnaire data showed that three were fluent (one was a native speaker), two reported a reasonable level of fluency, and one had a basic knowledge. In addition to te reo Māori, the kaiako (including regular relievers) were able to speak New Zealand Sign Language, German, French, Spanish and Japanese. Kaiako questionnaire findings and their focus group dialogue consistently advocated that tamariki should learn through te reo me ōna tikanga, and experience consistency in daily routines and practices.

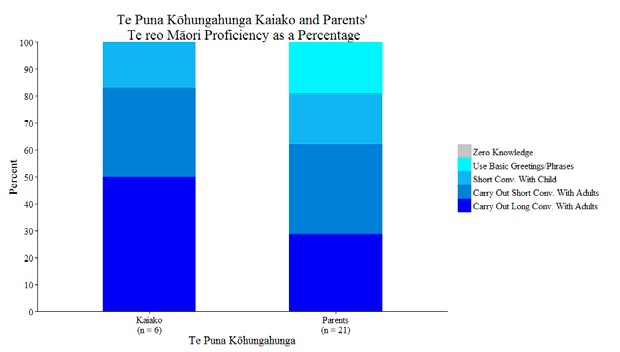

Kaiako and whānau te reo Māori proficiency are presented as percentages in Figure 4. Among whānau questionnaire respondents, all reported at least basic proficiency in te reo Māori, 80 percent could carry out short conversations with their child, around 60 percent could carry out short conversations with adults, and almost 30 percent could carry out long conversations with adults.

Figure 4.

The teacher–researchers reported that the questionnaire data were valuable for assessing the languages spoken by whānau. For example, the kaiako learnt that Spanish and French were third languages for three whānau. They were able to choose one trilingual whānau (German, English, and Māori) to be part of the whānau focus group discussion as well as three other whānau strongly committed to Te Puna kaupapa.

Valued experiences and outcomes for tamariki (children)

Research question 2: What experiences and outcomes for children who learn in more than one language in the early years are valued by parents, teachers and children?

Findings from the whānau questionnaire showed that generally whānau wanted their tamariki to be competent and happy to stand confidently in both worlds—Māori and Pākehā. There was a strong emphasis on bilingualism and biliteracy as well as overall academic success. In the whānau focus group, one father stated he wanted his children to speak te reo Māori all the time.

The kaiako and researchers established key themes across the questionnaire and focus group data. These themes were derived from the philosophy of Te Puna Kōhungahunga, with links to four tools that were used in the centre’s daily curriculum, assessment and planning processes: Te Whāriki, Te Whatu Pōkeka (Ministry of Education, 1996, 2009), Te Hāpai Ō (Jenkins, Harris, Morehu, Sinclair, & Williams, 2012), and Tātaiako (Ministry of Education & New Zealand Teachers Council, undated).

The kaiako reported that the key themes cannot be explained separately because they are closely interconnected, and there were often multiple āhuatanga (circumstances) for each whānau response. These six key themes are interlinked and mesh together: whanaungatanga (relationships); kaitiakitanga (guardianship); manaakitanga (to support, take care of); wairuatanga (spirituality); tangata whenuatanga (indigeneity); and tuakana/teina (mentorship). Data from kaiako and whānau questionnaires and focus groups, together with video recordings, support these interwoven themes.

Questionnaire responses showed that whanaungatanga was important, and that relationships and connections to te ao Māori were both tangible and intangible. The diversity of whānau cultures at Te Puna Kōhungahunga was evident. Kaiako and whānau responses indicated that with whanaungatanga connections, children could become confident to achieve their aspirations.

All focus group whānau had children who started at Te Puna Kōhungahunga as babies and they were there for the relationships fostered. One parent stated that coming to Te Puna was not for te reo Māori exclusively, but for the whanaungatanga and the whānau-driven kaupapa. Another whānau grew up on the marae, but because they found it difficult to provide this experience within an urban setting, whanaungatanga and kaitiakitanga fostered at Te Puna were important for the tamariki and whānau.

Kaiako described how whanaungatanga gave the whānau confidence to belong and to be responsive and proactive to look after others—kaitiakitanga. Questionnaire and focus group responses from whānau emphasised that bilingual and biliterate aspects and overall academic achievement were important to whānau. The focus group whānau indicated that their tamariki and mokopuna are the ones who will carry on te reo and tikanga.

In regard to wairuatanga, kaiako commented on spiritual connections to the land. Video recordings on the whāriki (mat times) showed tamariki confidently participating in karakia and waiata (prayers, songs).

In the focus groups, kaiako and whānau emphasised how manaakitanga is embedded in the philosophy of being Māori. One whānau spoke about commitment to the kaupapa of Te Puna, and stated that commitment was across all aspects of whānau life.

The theme of tangata whenuatanga was woven through the comments of both kaiako and whānau. All kaiako responding to the questionnaire stated that pepeha, karakia, waiata, Maungawhau (their nearby mountain), pōwhiri, and noho marae were focal parts of every day Te Puna life. Three of the whānau at the focus group reported their commitment to supporting (by coming to help) on noho marae and visits up Maungawhau. Questionnaire responses from some whānau showed they wanted their tamariki to help others; to be socially confident and competent not only in the Puna but also in the bush, the community, and the home; and to have equal opportunity.

Kaiako stated in the questionnaires that tuakana/teina—older tamariki looking after younger ones—occurred naturally, even among the babies. They gave examples of the contexts where this was evident: pānui pukapuka (reading), wā whāriki (mat time), hīkoi Maungawhau (group walking up Maungawhau), and play.

Opportunities and challenges

Research question 3: How might the opportunities and challenges for children who learn in more than one language be addressed in educational practice?

Kaiako considered that a positive outcome of these multiple themes was that they had come to realise that these āhuatanga (circumstances) are always interconnected in all aspects of Te Puna Kōhungahunga practices and approaches. As an example we will use our fortnightly Maungawhau hīkoi (walk up Mt Eden, the mountain close to Te Puna Kōhungahunga) to illustrate all themes.

Our centre philosophy is based on whanaungatanga and our hīkoi aren’t possible without whānau to support our teacher ratios. Our whānau are able to get to know each other during these hīkoi. One of our whānau lives on the maunga as kaitiaki and he shared valuable insights and knowledge about the maunga and local tikanga (tangata whenuatanga) [This was evident in the video data of interactions]. Our relationship with Maungawhau allows us to naturally practise wairuatanga and our spiritual connection not just to the land but to the language we use. One of our kaiako composed a karakia that we use to teach acknowledgement, respect and gratitude for tūpuna and iwi. Tuakana/teina relationships are present between kaiako/whānau and tamariki as well as amongst themselves (especially our new two- year-olds coming up for the first time). This aspect flows on to the āhuatanga of manaakitanga where everyone is responsible for self-care, care for each other, as well as their wider environment. (Marama Young and Jasmine Castle)

Within this Māori-medium setting, pepeha at mat times provided opportunities for tamariki to experience a sense of belonging. One challenge related to tangata whenuatanga was how to support identities and overseas whānau. Kaiako became more conscious of the whānau aspirations for their tamariki and how that impacts on centre practice. The data collected enabled deeper connections in kaiako relationships with tamariki, whānau, and one another. Kaiako put strategies in place to encourage more meaningful one-to-one tamaiti interactions, to improve assessment and planning methods and ultimately valuable learning experiences and outcomes for tamariki.

The A’oga Fa’a Samoa

Centre context

The A’oga Fa’a Samoa is a Samoan-language immersion centre located in the grounds of Richmond Road Primary School in Ponsonby, Auckland. The centre began operating in 1984 and in 1990 was the first licensed Pacific Island centre in New Zealand (Taouma, Tapusoa, & Podmore, 2013). At the time of data gathering, the centre was staffed by 12 registered teachers and licensed for 50 children, 16 of whom were aged under two years.

A philosophy statement developed by and for the A’oga Fa’a Samoa was supported by research on language immersion and bilingualism. This statement showed evidence of connections between children’s learning of their heritage/home language, their identity, and their educational success (Cummins, 2001a, 2001b, 2009; Podmore & Wendt Samu, 2006; Tuafuti, 2010; Tuafuti & McCaffery, 2005).The philosophy states that the A’oga Fa’a Samoa will:

- promote Samoan language and culture, so nurturing the positive identity of the children

- employ trained educators (qualified teachers) and encourage further training so that quality care and education is provided

- encourage a family atmosphere for parents and children so children feel secure and loved

- emphasise enjoyment of learning through the medium of Samoan language.

Consistent with the centre philosophy, the curriculum, resources and learning programme were entirely in the Samoan language. Teachers spoke Samoan only, documentation was in Samoan, parents were encouraged to attend Samoan language programmes/classes, and books and teaching resources are developed in Samoan. English-speaking areas were set up for visitors, parents and family members who are not fluent Samoan speakers.

Research participants

Twelve teachers completed questionnaires in English, and 11 participated in the teacher fono/focus group, conducted and analysed in Samoan and then translated into English.

Thirty-five parents completed questionnaires, and seven participated in the parents’ focus group, including two couples (i.e., five families were represented). Teachers selected the focus group parents from different language backgrounds, to represent the diversity within the centre. Several spoke languages other than Samoan in the home (i.e., Tongan, Japanese and Māori).

Six child interviews were completed and transcribed in Samoan, then later translated into English.

Languages spoken by children in the centre and at home

Research question 1: What languages do children from participating ECE centres use in their learning in the centre and at home?

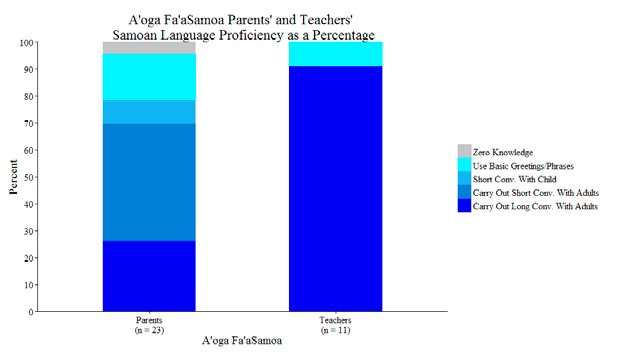

Questionnaire findings on parents’ and teachers’ reported proficiency in speaking Samoan are summarised in Figure 5 below which confirmed that almost all of the teachers could carry out long conversations with adults and were fluent speakers of Samoan, whereas fewer than 30 percent of the parents responded that they could carry out long conversations with adults in Samoan.

Figure 5.

Questionnaires and video observations confirmed that in the centre, teachers spoke Samoan and the children spoke both Samoan and English. Teachers in the focus group described how, when a group of children were speaking English, the teacher would respond entirely in Samoan. As evident in video clips of the context of mat times, the children mainly used the Samoan language to talk, recite and interact. Observations of arrival and departure times showed that, along with Samoan and English, one Japanese, one Tongan, and three Māori parents regularly used their heritage/home languages with their own children.

Teachers in the focus group reported that in the home, children used both Samoan and English. Some focus group parents explained that when they used Samoan at home they might be corrected by their children. Parents commented that they actively encouraged their children to speak Samoan, particularly to their older relatives. Many parents’ responses to the questionnaires, together with some focus group comments, indicated they felt challenged to learn more Samoan.

Valued experiences and outcomes for children

Research question 2: What experiences and outcomes for children who learn in more than one language in the early years are valued by parents, teachers, and children?

The analyses of the focus group interview and the questionnaire data showed considerable consistency on experiences and outcomes valued by teachers and parents. Teachers valued the importance of the Samoan language, and described how parents valued their heritage/home languages. Teachers also valued the support of parents to continue using Samoan in the home, and valued the partnerships with parents.

Teacher–researchers and researchers worked together to sort the participants’ comments on children’s experiences, and the learning outcomes that they valued, into overarching key themes.

1. Holistic development, including spirituality and identity

This theme was consistent with the “holistic development” principle of Te Whāriki. Focus group parents’ comments endorsed the centre practices that reflect the principle of holistic development. In this context, holistic learning and development is inclusive of Samoan (heritage/home) language learning, identity development and spirituality.

When asked about their experience of the cultural practices at the A’oga Fa’a Samoa, several parents spoke about what they valued, including experiences of prayers (lotu), celebrations, respect for elders, language, food and dress, which was associated with self-esteem. The theme of holistic learning and development was similarly evident across the questionnaires completed by a wider group of parents. The learning experiences and outcomes that parents valued for their children focused, alongside academic learning and success, largely on: Samoan language; fa’a samoa/cultural practices, spirituality and respect; and identity and wellbeing. Video observations of children during group sessions that included lotu and introducing themselves, demonstrated further their strong identity, confidence and competence in these holistic learning and teaching situations.

2. Valuing the power of the Samoan language

Discussions with parents highlighted what Cummins (2001a, 2001b, 2009) terms the power of language. Parents and teachers commented that colonisation of language (i.e., historical pressure to use English only) had acted as a trigger for them to recognise what they had lost, to value the Samoan language, and to encourage their children to speak Samoan.

Valuing the power of the Samoan language also encompassed shifting to positive use of the language. Some focus group parents described a tendency to resort to their most familiar language to express anger or “to growl” at their children. Parents valued the use of the Samoan language at the A’oga for “good things”. Teachers explained that valuing the power of child’s language involves using the heritage/home language primarily in a positive way.

3. Heightened meta-linguistic awareness

Focus group parents and teachers commented on their young bilingual children’s receptivity to other languages, indicating children’s meta-linguistic awareness. Parents described how their children became aware of, recognised, and accepted diverse languages and identities. Meta-linguistic awareness was also apparent in children’s transfer of Samoan language from the centre to their home or community.

4. Transfer of languages

One highly valued outcome of children’s learning was the transfer of the Samoan language from the A’oga immersion setting to the home. Less fluent focus group parents described how their own heritage/home language learning became enriched alongside their children’s, thereby reversing a generational trend of language loss.

Opportunities and challenges for children and teachers

Research question 3: How might the opportunities and challenges for children who learn in more than one language be addressed in educational practice?

Findings exemplify an additive approach to bilingualism in action within a language-immersion setting. The overarching key opportunities and challenges for educational practice were: providing additional Samoan language support for children and their families; keeping children’s learning and assessment records entirely in Samoan, the heritage/home language; empowering parents by involving them in the programme; and celebrating identities “being Samoan and others”.

Mangere Bridge Kindergarten

Centre context

Mangere Bridge Kindergarten, built in 1975, operates under the governance of the Auckland Kindergarten Association. It is located within a residential area in south Auckland and has a long history of community involvement. Located on a peninsula, the kindergarten community values the sites of local significance: Ambury Regional Farm Park and Mangere Mountain.

The kindergarten is an English-medium centre. The operating model changed in 2013 from a sessional kindergarten to a day-model kindergarten (8:30 a.m. to 2:30 p.m.). As a result of this change the permanent teaching team increased from three to four teachers to comply with a 1:10 teacher: child ratio. The permanent teaching team are all fully qualified, registered teachers; three have postgraduate qualifications. The number of families belonging to the kindergarten fluctuated between 55 and 60, with a maximum of 40 children on the roll on any one day.

The Mangere Bridge community is one of diversity: culturally, linguistically, ethnically and socio-economically. The kindergarten community comprised a demographic mix of approximately 48 percent Pākehā, 17 percent Māori, 17 percent Pasifika, and 10 percent Asian or South-East Asian, with the remainder made up of people identifying with a range of ethnicities, from Africa, Australia, United States of America, Europe and the United Kingdom.

The kindergarten philosophy statement highlighted a fundamental belief in the importance of working to forge partnerships among teachers, children, families and the community. Also fundamental to the joint philosophy of the teaching team was fostering an inclusive environment, one that recognises children as individuals with their own strengths and funds of knowledge (González, Moll, & Amanti, 2005). The value of play to support children’s learning was embedded in practice. Teachers aimed to provide an environment for children that was safe, challenging and stimulating, where responsibility for self and others is valued.

Research participants

Seven teachers completed questionnaires and participated in the focus group (four permanent fulltime teachers, one long term reliever and two student teachers). The four permanent, full-time teachers considered themselves monolingual English speakers. These four teachers all live in the Mangere Bridge community, are long-time residents and feel the “community stories” are “their stories”.

Thirty-eight parents completed questionnaires, and 10 adults participated in the parent/whānau focus group, including two couples and one mother/daughter pair (i.e., seven families were represented). Teachers selected the focus group participants from those who signed consent forms to gain input from as wide a representation as possible of the diversity of languages within the centre. Criteria included families with a variety of linguistic, cultural and ethnic affiliations; families where the adults spoke different languages to each other; families where there is intergenerational diversity; and a mixture of long-term New Zealand residents and new arrivals. All focus group participants were comfortable speaking English during the interview.

Ten children agreed to be interviewed. There were eight individual interviews and one sibling interview conducted with the two children together.

Languages spoken by children in the centre and at home

Research question 1: What languages do children from participating ECE centres use in their learning in the centre and at home?

Parent questionnaire data indicated that there were 26 languages spoken amongst the kindergarten community, with some children speaking three or more languages in their homes and community. As shown previously in Figure 2, the four permanent teachers reported that they were highly proficient in English only.

Teachers in the focus group reported that some children who shared a heritage/home language in common, for example Tongan or German, often communicated in their heritage/home language and English. They also reported that during mat times, English was the usual language of communication. Video data showed that small groups of children who shared a language clustered to play and some code switching occurred, although they most often used English. At arrival and departure times, observations showed that parents regularly used their heritage/home language with their children and switched between heritage/home language and English. Examples of languages heard at these times were: Japanese, Karen (a Tibeto-Burman language sometimes spoken in Myanmar and Thailand), French, Vietnamese, Kurdish, Gujarati, Hindi, Māori, Samoan, and Tongan.

Parents reported that at home, children used both their heritage/home language and English. Some parents also reported that their children began using English more at home once they were settled at kindergarten.

Valued experiences and outcomes for children

Research question 2: What experiences and outcomes for children who learn in more than one language in the early years are valued by parents, teachers and children?

The analyses of the teacher and parent focus group interviews and the questionnaire data showed some consistency on valued experiences and outcomes.

The overarching themes from the teachers’ focus group included a strong emphasis on the importance of relationships and inclusive practice. Teachers’ responses reflected an additive approach to language and literacy acquisition (Cummins, 2009; Taylor, Bernhard, Garg & Cummins, 2008), valuing the support of parents to introduce heritage/home languages into the kindergarten, and building partnerships with parents to foster children’s sense of belonging and multiple identities.

Teachers’ ideas on valued experiences and outcomes were formed by experience and driven by professional knowledge and understandings of Te Whāriki. Teachers valued the importance of retaining the child’s heritage/ home language and culture, and understood and acknowledged how parents valued their heritage/home languages. Teachers endeavoured to learn words and phrases in as many languages as possible.

Parents in the focus group were emphatic that the responsibility for maintaining the heritage/home language rested with the families. Conversely, the multilingual parents in the focus group regarded the centre as the place where the children would learn English for future educational success.

Both the teachers’ and parents’ questionnaire and the focus group data on valued experiences and outcomes generated three overarching key themes.

1. Relationships

Teachers commented in the focus group that they considered children’s learning outcomes were reliant on the knowledge and relationships they developed with children and families. Parents valued the relationships the teachers built among the diverse children. Parents also appreciated the way teachers valued and included grandparents in the kindergarten programme.

2. Identities

Members of the parent focus group stated emphatically that identity is inextricably tied to language. Parents drew on their own experiences and funds of knowledge to understand the link between language and identity and were aware of the complexities of retaining their own heritage/home language in an English-dominant environment. Parents valued English for the opportunities and status it would potentially give their children for education and employment in the global arena. However, parents also had aspirations for the children to be able return to their home country and to speak the language of that country. A valued outcome was therefore to be a global citizen and a local citizen; one who works in multiple worlds, able to communicate in the language of the country their children are in at the time.

3. Environments and communities

Parents’ comments endorsed the centre practices that reflected the approach of additive bilingualism. Parents also valued the play-based curriculum, as they saw their children acquiring English during their experiences with other children in the centre.

A third of the parents who completed the questionnaire reported a desire for their children to fit in to the range of environments and diverse communities that their children move between in Aotearoa/New Zealand. They wanted their children to be able to engage with the social community of sports and neighbours; the educational community of kindergarten, school, and later tertiary study; and the heritage community of home, wider family, church and homeland.

Opportunities and challenges for children and teachers

Research question 3: How might the opportunities and challenges for children who learn in more than one language be addressed in educational practice?

The overarching key themes suggested opportunities and challenges for educational practice. Findings showed that parents and teachers valued opportunities for children to become bilingual and/or multilingual, as this offered cognitive, educational and social benefits.

Responses from the parent focus group and questionnaire identified an associated challenge for their children as having the social and educational skills to fit in and contribute to society. Some parents spoke of effective strategies for maintaining the heritage/home languages; others found it increasingly difficult to maintain their heritage/home languages as the child’s social connections with English speakers increased.

The major challenge that these monolingual teachers commented on was to acknowledge adequately, and include, the 26 languages present in such a diverse kindergarten community.

Symonds Street Early Childhood Centre

Centre context

The Symonds Street Early Childhood Centre is one of the University of Auckland’s early childhood centres, located in the central city. It is a sessional early childhood centre, licensed for 36 children from 2½ to 5 years at any one session. It provides early childhood services for students and staff of the University of Auckland. Occasionally, spaces are available for children from the local community. It is an English-medium but multiethnic centre. There was a team of seven bilingual or multilingual teachers. Six were qualified and registered teachers.

The centre philosophy embraced and celebrated cultural, social, and linguistic diversity amidst the tamariki, whānau and community. Teachers were expected to respond sensitively to each child and family’s concern to build on their heritage/home languages as well as supporting English language learning. Many families returned to their home country for periods of time and eventually permanently. Consequently their young children needed to be able and adaptable learners within two countries and two education systems.

Research participants

Seven teachers completed the questionnaire and six participated in the teacher focus group. The teacher focus group with the bi/multilingual teachers was conducted in English.

Twenty-seven parents completed the questionnaire. For the parent focus group, teachers selected parents who had consented and responded to the project with interest and who used their home/heritage language with their children. Further criteria were availability during university examination time, and representation of diverse languages. Four parents, all mothers of children at the centre, participated in the focus group. Languages from Korea, Japan, Indonesia and Chile (Spanish) were represented.

Six child interviews were completed. Teacher–child interview pairs were selected according to the teacher’s fluency in the child’s heritage/home language.

Languages spoken by children in the centre and at home

Research question 1: What languages do children from participating ECE centres use in their learning in the centre and at home?

Questionnaire findings on languages spoken both by parents and by teachers showed a wide range of languages were used. In total among the teachers, 12 languages were represented: English, te reo Māori, Cook Island Māori, Tongan, Samoan, Tamil, Singhalese, Urdu, Hindi, Arabic, Malayalam and Telugu.

Parent questionnaire data showed that, collectively, the 27 families spoke many languages in addition to English. Languages most frequently spoken in the home included Bahasa Malaysia (five families) and Urdu (three families). Mandarin, Talalog/Filipino, Bahasa Indonesia, Japanese, Farsi and Spanish were also spoken in homes. In addition, there were parents who reported they were fluent speakers of Russian, French, Niuean, Korean and Singhalese.

At the time of the field-note observations of arrivals and departures, collectively the 41 children observed spoke 16 languages. Twelve spoke English and two spoke te reo Māori. Five children spoke Bahasa Malaysia/ Malay, four spoke Japanese, three spoke Bahasa Indonesia, three spoke Urdu, and two spoke Arabic or Korean. Tagalog, Swedish, Mandarin, Russian, Farsi, Singhalese, Malayalam and Spanish were also documented.

Teachers interacted with the children in English, also using nonverbal communication strategies, and in the child’s heritage/home language when the teacher could speak that language.

Valued experiences and outcomes for children

Research question 2: What experiences and outcomes for children who learn in more than one language in the early years are valued by parents, teachers, and children?

Analyses of the teacher and parent focus group interviews and questionnaire data established four common themes as set out below.

1. Well-being and belonging

A settled, comfortable child who is understood

Focus group findings showed that teachers and parents valued and fostered a well-settled and happy child, aligned with Well-being, a strand of Te Whāriki (Ministry of Education, 1996). Teachers recognised that transitions brought challenges as the children and families were new to New Zealand, to the English language, and to the early childhood environment. Reflections from a focus group teacher, who shared a common heritage/home language with an unsettled child, revealed the child was frustrated when not understood.

Responses from the teacher questionnaire detailed many non-verbal strategies used to communicate with unsettled children. Through talking with parents, teachers also developed a list of useful words, phrases, sentences and greetings to use to settle the children. All teachers in the focus group valued children’s use of their heritage/home languages for learning in the centre. Parents valued experiences that led to children being understood, participating and enjoying learning.

2. Relationships and identities

Friendships and building strong identities and communities

Parents and teachers in the focus groups also spoke of the value of children experiencing friendships and building strong identities that empowered the child’s sense of belonging. Families new to New Zealand welcomed the friendships among the children, particularly when they shared a common language or culture. These friendships generated a sense of community across families.

3. Contribution

Contributing by being a same-language buddy and settling a younger child

Focus group teachers highlighted the value of settled, older children taking responsibility for younger children who usually shared their language (the tuakana teina concept). This was also documented in learning stories and supported by video observations. This “buddying” settled the younger children, enabled them to learn, and set up a pattern for the younger children to take on similar responsibilities. These valued experiences were consistent with parents’ desired outcome of confident, socially able and respectful children.

4. Rich language and cultural environment

The questionnaire and focus group data showed that most parents valued the rich multilingual centre environment for their children. They valued the educational culture of play, the respect for others and the absence of prejudice. This was consistent with the focus group teachers’ responses, and a counterpoint to their personal less empowering experiences as migrants.

Opportunities and challenges for children and teachers

Research question 3: How might the opportunities and challenges for children who learn in more than one language be addressed in educational practice?

Parents’ and teachers’ comments in the questionnaires and in their focus groups showed they experienced major opportunities and challenges related to maintaining heritage/home languages while also acquiring English for learning. Parents were worried about their children’s loss of quality heritage/home language use when they returned to their home countries. Some spoke of finding ways to reconnect with grandparents, extended families, and the education system at home. They also reported strategies to support children’s use of quality English.

Teachers reported on opportunities to help resolve the challenge of so many languages. Their strategies included conversations with parents about languages support, and sharing information about songs, greetings, phrases and cultural artefacts from specific language groups. Parents’ positive responses to requests to share histories, music, cultural treasures and practices were well documented in learning stories and video data. Multilingual teachers acted as role models for learning and teaching in more than one language.

Parents and teachers viewed children’s acceptance of multilingual and multicultural diversities as opportunities. This included acknowledging tangata whenua and becoming familiar with te reo Māori.

Findings indicated that challenges also arose when parents were unsure of the benefits of bilingualism. Parent data endorsed the view that English had high status and was seen as essential for academic achievements and future success.

Implications across settings

Each centre’s research findings were strongly rooted in their own philosophy and defining character, as reflected in the key themes. There were several overlapping principles and concepts. Themes across all four centres strongly connected to aspirations, principles and strands of Te Whāriki. Relationships, family and community, and holistic development, were clearly evident. Overarching this, it was clear that the principle of empowerment guided the philosophy and practices of each centre. However, the findings also showed that each centre had their own priorities and pedagogical pathways, consistent with the shared, valued language and educational aspirations. Parents and teachers valued fostering children as competent, confident learners who are strong in their identities, through engaging with their languages and cultures.

Teachers at all centres reflected on the processes and findings of the research and made some changes. Some of their insights about opportunities and challenges potentially provide suggestions for practice within similar types of ECE settings.

Conclusions

At Te Puna Kōhungahunga the teachers came to know more about parents and children through administering the parent questionnaire and through the process of the parent focus group. For example, teachers learnt more about the languages spoken in the children’s homes, and about parents’ aspirations for their tamaiti. A teacher-researcher explained further that “we now know the whānau have languages other than te reo Māori, but they want their children to [prioritise] te reo Māori and to be bilingual and biliterate”. Through child interviews and discussions with young children about the learning stories and portfolios, teachers listened in greater depth to individual children. As a result of the research, these types of in-depth discussions about each child’s portfolio, languages, and whānau aspirations for children, became more systematic and established practices at the centre. Te Puna Kōhungahunga have moved increasingly towards full immersion, and although respecting diversity, there is a commitment to becoming a full immersion centre. This movement towards full immersion in te reo Māori was supported by the research, but also due to dynamic changes in enrolments, with more babies starting at the centre towards the end of the research project.

During the process of the research at the A’oga Fa’a Samoa, teachers worked alongside three university researchers to identify and analyse key themes arising from the data. Although challenging, this research process provided teachers with an opportunity to examine their practices further, with reference to relevant research literature on bilingualism. Reflections on the results of the research included: “I think something we got from the research is the power of language, how we need to teach the children [entirely] in Samoan, and that scolding [using the heritage/home language] is not needed”. Teacher–researchers contributed to discussions with the researchers about using the heritage/home language in a positive way with young children to extend their learning. Teachers at the A’oga Fa’a Samoa noted that the results of the research encouraged them to continue and extend their Samoan-language immersion practices, and that an ongoing challenge for the centre was to encourage children to transition to the bilingual Samoan class in the primary school to maintain and extend their Samoan language competence.

Teachers at Mangere Bridge Kindergarten redrafted the philosophy statement to include a statement on languages, after participating in the first meeting of the project’s advisory/reference group where advisors and experts identified this as a priority for centres and schools. During the research process, teachers also changed the children’s portfolios by including on the cover and inside it space to prioritise the child and his/her family’s language and cultural identities. Teachers reported that the new portfolios became a point of deeper connection with families: many expressed appreciation of the opportunity to reawaken cultural and languages histories. Teachers from the first years’ classes at two neighbouring schools requested that the languages and cultural information be included in the kindergarten’s “transition to school” portfolios, to provide a valuable introduction to the child and family. Teachers documented children’s fascination with language differences and noted that inquiries about languages spoken, generated initially from the use of individualised language greetings at mat time, became part of home conversations too.

The major changes at Symonds Street Early Childhood Centre were shifting, from an assumption that children came to learn English and that teachers used their own languages only to support that transition and learning, to understanding the deeper value of learning in more than one language. Research provided an opportunity to share concerns, misapprehensions, and the value of learning in multiple languages in a primarily English-speaking nation. Data opened up awareness that home languages had multiple valued purposes and outcomes. Teacher–researchers reported growing confidence and validation to act as knowledgeable guides when bilingual parenting concerns arose for parents. The research became a catalyst for changes: children settling other children who spoke similar languages; language as a cognitive resource not just a settling resource; languages as a way for children and families to connect more; teachers extending the range of languages used beyond greetings and simple words to inclusion of stories in diverse languages; the whole community becoming a wider resource; and growing reciprocal and extended relationships.

In summary, the overall findings within and across the four centres, together with the teacher–researchers’ concluding reflections, showed how the centres were all different, changing and dynamic. There were implications for practice, as indicated in the teachers’ reflections on the findings. Research findings across the four centre settings indicated that the ethos and culture of the centre were important in creating an empowering environment supporting plurilingualism and additive bilingualism. Where parents or teachers did not have the resources, they were able to draw on the funds of knowledge within their communities, including parents and community elders. Across the four centres’ learning and teaching contexts, this research showed strong and powerful images of children as they built their identities and language resources. These images support the benefits of children learning in more than one language.

At all four centres, te reo Māori was evident and being encouraged, influenced by professional uptake of Te Whāriki, greater use of te reo Māori in teacher education, and greater interest in te reo Māori. However, the census findings showing a continuing decrease in te reo Māori are of concern.

Each centre was distinctive in nature, whether Samoan immersion, Māori-medium, or English-medium. The findings, together with changes made in the centres, showed how multiple languages may be fostered intentionally in planned and systematic ways by teachers who are fluently bilingual, multilingual, and in one setting, monolingual. Teachers need the professional knowledge, skills, attitudes and understandings to enact additive bilingual approaches and practices, and to engage with the local funds of knowledge. We invite teachers to consider the type of setting that most closely represents their centre, in order to transfer insights from the research findings and reflections about young children who learn in more than one language from this study to their own contexts.

References

Carr, M., & Lee, W. (2012) Learning Stories: Constructing learner identities in early education. Los Angeles: Sage.

Cowie, B., Otrel-Cass, K., Glynn, T., Kara, H., with Anderson, M., Doyle, J., et al. (2011). Culturally responsive pedagogy and assessment in primary science classrooms: Whakamana tamariki: Summary report. Retrieved from http://www.tlri.org.nz

Cummins, J. (2001a). HER classic empowering minority students: Framework for intervention. Author’s introduction. Harvard Educational Review, 71(4), 649–655.

Cummins, J. (2001b). Negotiating identities: Education for empowerment in a diverse society. (2nd ed.) Los Angeles: California Association for Bilingual Education.

Cummins, J. (2009). Pedagogies of choice: Challenging coercive relations of power in classrooms and communities. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 12 (30), 261–271.

Cummins, J., & Early, M. (2011). Identity texts: The collaborative creation of power in multilingual schools. Stoke-on-trent, UK: Trentham Books.

Garcia, O. (2009). Bilingual education in the 21st century: A global perspective. Malden, MA and Oxford: Basil/Blackwell.

Garcia, O., & Kleifgen, J. (2010). Educating emerging bilinguals: Policies, programs and practices for English language learners. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

García, O., & Li Wei. (2014). Translanguaging: Language, bilingualism and education. New York, NY: Palgrave MacMillan.

González, N., Moll, L. C., & Amanti, C. (2005). Funds of knowledge: Theorizing practices in households, communities and classrooms. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Hedges, H., & Cooper, M. (2014). Early years curriculum: Funds of knowledge as a conceptual framework for children’s interests. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 43(2), 185–205. doi: 10.1080/00220272.2010.511275

Jenkins, K., Harris, P., Morehu, C., Sinclair, E., & Williams, M. (2012). Te hāpai o: Induction and mentoring in Māori-medium settings.

Wellington: New Zealand Teachers Council. Retrieved from http://www.teacherscouncil.govt.nz/content/te-hapai-o

Keegan, P. J., Trinick, A. B., & Morehu, T. R. O. (2009). He kainga korerorero: Project one—baseline survey, final report prepared for Te Puni Kokiri: He kainga korerorero: Project one—baseline survey. Auckland: UniServices.

McCaffery, J., & McFall-McCaffery, J. (2010). O Tatatou o aga’i i fea?/’Oku tatu o ki fe?/ Where are we heading?: Pacific languages in Aotearoa/New Zealand. AlterNative Special Supplement Issue Ngaahi Lea ‘a e Kakai Pasifiki: Endangered Pacific Languages and Cultures, 6(2), 86–121.

Meade, A. (2010). The contribution of ECE Centres of Innovation to building knowledge about teaching and learning 2003-2010. Paper presented to TLRI Early Years Symposium, Wellington, 12 November 2010. Retrieved from http://www.tlri.org.nz

Ministry of Education (1996). Te Whāriki: He Whāriki Mātauranga mō ngā mokopuna o Aotearoa: Early childhood curriculum. Wellington:

Learning Media. Retrieved from http://www.educate.ece.govt.nz/learning/curriculumAndLearning/TeWhariki.aspx

Ministry of Education. (2009). Te whatu pōkeka: Kaupapa Māori assessment for learning early childhood exemplars. Wellington, New Zealand: Learning Media. Retrieved from http://www.educate.ece.govt.nz/learning/curriculumAndLearning/Assessmentforlearning.

aspx

Ministry of Education & New Zealand Teachers Council. (Undated). Tātaiako: Cultural competencies for teachers of Māori learners.

Wellington: Ministry of Education and New Zealand Teachers Council. Retrieved from http://www.minedu.govt.nz/TheMinistry/ EducationInitiatives/Tataiako

Morton, S. M. B., Atatoa Carr, P. E., Grant, C. C., Berry, S. D., Bandara, D. K., Mohal, J., et al. (2014). Growing up in New Zealand: A longitudinal study of New Zealand children and their families. Now we are two: Describing our first 1000 days. Auckland: Growing Up in New Zealand.

Ninio, A., Snow, C. E., Pan, B., & Rollins, P. (1994). Classifying communicative acts in children’s interactions. Journal of Communication Disorders, 27, 157–188.

Penuel, W. R., Fishman, B. J., Cheng, B. H., & Sabelli, N. (2011). Organising research and development at the intersection of learning, implementation, and design. Educational Researcher, 40(7), 331–337.

Podmore, V. N. (2006). Observation: Origins and approaches to early childhood research and practice. Wellington: NZCER Press.

Podmore, V. N. with Wendt Samu, T. (2006). O le tama ma lana a’oga, O le tama ma lona fa’asinomaga Nurturing positive identity in children: Final Research Report from the A’oga Fa’a Samoa an Early Childhood Centre of Innovation. Wellington: Ministry of Education. Retrieved from http://www.educationcounts.govt.nz/publications/ece/22551/22555

Rogoff, B. (2003). The cultural nature of human development. New York: Oxford University Press.

Siraj-Blatchford, I. (2010). Mixed-method designs. In G. MacNaughton, S. A. Rolfe, & I. Siraj-Blatchford (Eds.). Doing educational research: International perspectives on theory and practice (pp. 193–208). Crows Nest, NSW: Allen & Unwin.

Statistics NZ. (2006). QuickStats about culture and identity: Languages spoken; QuickStats about Pacific peoples: language. Retrieved from http://www.stats.govt.nz

Statistics NZ. (2013). 2013 Census. Retrieved from http://www.stats.govt.nz/census/

Taouma, J., Tapusoa, E., & Podmore, V. N. (2013). Nurturing positive identity in children: Action research with infants and young children at the A’oga Fa’a Samoa, an early childhood Centre of Innovation. Journal of Educational Leadership Policy and Practice, 28(1), 50–59.

Taylor, L., Bernhard, J., Garg, S., & Cummins, J. (2008). Affirming plural belonging: Building on students’ family-based cultural and linguistic capital through multiliteracies pedagogy. Journal of Early Childhood Literacy, 8(3) 269–294. doi:10.1177/1468798408096481

Tuafuti, P. (2010). Pasifika additive bilingual education: Unlocking the culture of silence. MAI Review, (1). Retrieved from http://review. mai.ac.nz

Tuafuti, P., & McCaffery, J. (2005). Family and community empowerment through bilingual education. The International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 8(5), 1–24.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978) Mind in society: The development of higher mental processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Yin, R. K. (2014). Case study research: Design and methods (5th ed.). Applied Social Research Methods Series (Vol. 5). Thousand Oaks, California: Sage.

Acknowledgements

- Patisepa Tuafuti, Diane Mara, Jenny Lee (former members of the University of Auckland research team)

- Children, families and teachers in our partner centres

- Funding through the Teaching and Learning Research Initiative

- Auckland UniServices Ltd

- University of Auckland Human Participants Ethics Committee

- Auckland Kindergarten Association Research Access and Ethics Committee

- Members of this project’s reference group

About the authors

Authors from the Faculty of Education and Social Work at the University of Auckland

Valerie N. Podmore, a visiting associate professor in the School of Curriculum and Pedagogy, led this project and supports early childhood research. Her research programme in the area of learning and teaching in the early years is overarched by a commitment to culturally responsive work.

Helen Hedges is an associate professor in the School of Curriculum and Pedagogy. Her research programme focuses on children’s and teachers’ knowledge, interests and learning, and ways these coalesce to create curriculum responsive to partnerships with families and communities.

Peter J. Keegan (Waikato-Maniapoto, Ngāti Porou) is a senior lecturer in Te Puna Wānanga. His research interests include Māori and indigenous languages documentation and conservation, and the education and achievement of Māori and minority group students. He focuses on quantitative approaches to research and data.

Nola Harvey is an honorary academic in the School of Curriculum and Pedagogy. Nola specialises in the area of languages and literacies in the early years, and works in close collaboration with partnership centres in this TLRI project.