Introduction

We have been studying the cultural constructions and material realities of university-based initial teacher education (ITE) and teacher educators’ work in Aotearoa New Zealand. By examining the work of teacher educators, we have been able to consider how ITE and the academic category of teacher educator is constructed, maintained, and practised within the institution of the university. Exploring teacher educators’ work, including teaching and learning activities from perspectives of both student teachers and teacher educators, has provided us with new insights into teaching and learning within university-based ITE. Our research questions have been:

- How is “teacher educator” constructed and maintained as a category of academic work?

- What do university-based teacher educators do? What are they working on?

- How do the pedagogical activities of teacher educators shape opportunities for student teachers’ learning?

- What are student teachers’ interpretations of and motives towards artefacts and activities within ITE?

This project links New Zealand research in teacher education with an international network of scholarship from the United Kingdom (England and Scotland), Australia, and Canada where teacher educators like us are increasingly interested in studying teacher education from an explicitly materialist stance (Ellis, Blake, McNicholl, & McNally, 2011; Nuttall, Brennan, Zipin, Tuinamuana, & Cameron, 2013). The affordances of cultural-historical activity theory (CHAT) (Engeström, 2001; Virkkunen & Newnham, 2013; Yamagata-Lynch, 2010) offers new insights into who teacher educators in New Zealand universities are, how we understand what they do, and their work motives and outcomes. Our New Zealand project has produced some different findings about the workings of the activity of university-based ITE compared to the Australian and United Kingdom studies. In the United Kingdom, a major finding was the extent to which relationship maintenance was a significant defining feature of teacher educators’ work (Ellis et al., 2013). Relationship maintenance is a major component of teacher educators’ work in New Zealand; however, the imperative to research has been as significant a factor in our study. In the Australian research, when job advertisement and recruitment documents were studied for the ways they constructed the academic category of teacher educator, it was found that the category of teacher educator was all but rendered absent by the institutional processes (Nuttall et al., 2013). In New Zealand, the category was reified in three related but quite different ways (Gunn, Berg, Hill, & Haigh, 2015). Furthermore, the instrumental responses to some university teaching by student teachers observed by researchers in the United Kingdom (Ellis et al., 2013) seemed less visible in our work with student teachers. Their meaning making about teaching as they learned through the activities and with tools designed by their teacher educators is discussed later in this report.

This study has also provided an opportunity to better understand how student teachers within university-based ITE respond to and engage with teacher educators’ work in the service of their own learning.

Governments are intensely interested in questions of how best to educate teachers, which kinds of institutions should host teacher education, and of course from whom prospective teachers should receive their professional education. In New Zealand, the majority of ITE is university-based—a situation that came about after six former stand-alone government-funded colleges of education merged with their local universities between 1990 and 2006. In bringing ITE under their remit, universities have been offered an opportunity to support system-wide improvement and to substantially shape its evidence base. But, they do so with a largely inherited workforce that has collectively been faced with a set of expanded work objects which may or may not have been desired.1 Furthermore, New Zealand is presently trialing postgraduate entry to teaching (Ministry of Education, 2013; Parata, 2012, 2013). This move signals the Government’s interest in raising the academic level of entry into teaching and, if adopted long term, will affect a major change within the system. Given the present context, our study into what ITE looks like, what teacher educators are working on, and how student teachers respond is timely.

Recent empirical New Zealand studies of ITE have tended to be descriptive in nature, but varied in both object of study and methods of enquiry. The existing body of work has provided insight into the content of ITE (Andreotti & Major, 2010; Kane 2005), how ITE addresses issues of inclusion and social justice (Purdue et al., 2009), assessment (Hill, Cowie, Gilmore, & Smith, 2010; Murphy et al. 2005), partnership and preparedness to teach (Anthony & Kane, 2008; Haigh et al, 2013; Ord, 2010). Brennan, Everiss and Mara’s (2010) report about non-university field-based early childhood ITE used elements of the CHAT framework to examine what teacher educators and student teachers were doing in their ITE classrooms. The study explored how student teachers who already worked as unqualified teachers were learning to teach. The analysis revealed the presence of a relational pedagogy within ITE where professional intersubjectivity between teacher educators and student teachers was key to learning. Our study, a focused examination of teacher educators’ work including their choices of pedagogical tools and activities and how these relate with ITE student learning, offers new insights.

Research design and methods

Our Work of Teacher Educators project in New Zealand adopts an explicitly materialist stance on workplace practices and outcomes to better understand present day instantiations of teacher education and consider how tools, artefacts, and activities shape possibilities for student teacher learning in the university. Given the complex intersections of activity systems, policy, and practice surrounding university-based ITE, our CHAT approach has allowed us to look concretely at the activity system of ITE in the university.

Design and data gathering

We undertook a two-phase mixed methods exploration of teacher educators’ work that focused on the nature, scope, and conduct of that work so we could more fully understand teaching and learning within universitybased ITE.

Data gathering: Phase 1

Advertisements and position/person description materials for 37 education faculty positions across seven universities were collected from a national university recruitment website and institutional websites during the 6 months from October 1, 2013 to March 31, 2014. Of these, 11 positions from six of the universities were identifiably related with ITE. Named personnel from the advertisements were contacted and invited to participate in a telephone interview. Using a structured interview guide, we explored how the position had come about, how its advertisement and associated documents were developed, the kind of skills and attributes desired in a potential recruit, and the nature of the work being advertised. Seven telephone interviews were conducted—at least one at each of the universities in our sample. Each interview lasted between 20 and 40 minutes and was audiotaped and transcribed.

Data gathering: Phase 2

In late 2014 and early 2015, a purposive sample of 15 teacher educators who worked across early childhood, primary, and secondary ITE within one-year teacher education programmes were recruited from two New Zealand universities—eight from East University and seven from West University (university names are pseudonyms). They were invited to participate in several data collection activities:

- initial telephone interviews (professional life histories were generated and views about their work shared)

- work diaries (teacher educators kept a log of their work activities across a single week, twice: Time 1 was in October 2014 and Time 2 was in February 2015)

- work shadowing observations (researchers accompanied teacher educators to work for a full day, making notes about activities, photographing artefacts and tools, and discussing teaching and learning activities with student teachers)

- A post-work shadowing telephone interview (researchers’ narrative accounts of teacher educators’ work were discussed for accuracy and tone; collated work dimensions data was re-presented to teacher educators to test the degree of fit between their sense of their individual work, the representation of it in the data, and its comparison to the collective experience of the teacher educators; and researchers enquired into the objects teacher educators’ had in mind with respect to selected teaching activities and tools observed in use during the work shadowing).

- A participatory analysis workshop in which teacher educators tested and contested the study’s interim findings using tools of the CHAT framework.

Participants and settings

Fifteen teacher educators from two of New Zealand’s universities participated. Both institutions had merged with their local college of education in the first decade of the 21st century. All the volunteering teacher educators were former teachers with professional experience in schools or early childhood education contexts (one early childhood, seven primary, seven secondary). The teacher educators’ professional experience (as teachers in early childhood education or the schools sector) ranged from 5 to 25 years, with a mean of 15.13 years and a median of 17 years. Twelve participants had been employed as teacher educators within former colleges of education prior to their institutional mergers. Years spent as a teacher educator ranged from 2 to 21 years, with a mean of 9.83 years and a median of 10. Six participants had completed doctorates and six were currently engaged in doctoral study. Two-thirds of the participants reported having significant leadership or administrative roles.

Data analysis

For Phase 1, our analysis comprised two main strands: a membership categorisation analysis, linguistic annotation strategy, and identification of key words in context; and a comprehensive discourse analysis. For a full description of the process in Phase 1, see Gunn et al., 2015.

In Phase 2, we:

- analysed professional life history interviews for perceptions of significant turning points and adaptations to participants’ work lives, including changes to material conditions of work and teacher educators’ dispositions towards their work

- analysed work dimensions data individually and collectively for time spent on administrative, service, research, practicum and teaching (later combined into a category we called “combined teaching”) work before using that data to interrogate, with participants, the picture of the work produced after the work shadowing

- identified tools and artefacts used within the activity system of university-based ITE and examined transcripts of student teachers’ and teacher educators’ talk about the tools and artefacts using the CHAT framework

- studied field notes and audio-transcripts from the participatory analysis workshop for the ways teacher educators made distinctions and decisions about teacher educators’ work, thus permitting particular lines of thinking about university-based ITE to emerge.

Statement of ethics

The study was subject to ethics approval from each of the researchers’ institutions. Informed consent was sought from, and granted by, participants.

Key findings

The construction and maintenance of teacher educator as a category of academic work

We explored teacher educator as a category of academic work in both phases of our study. As reported in Gunn et al. (2015) and in accord with our CHAT approach, we accepted that job advertisements and associated documents could be understood as cultural tools that mediate relationships between people and objects. Therefore, in Phase 1 we studied recruitment and appointment processes. Our analysis found that the academic category of teacher educator within New Zealand universities is being produced in three distinct and related ways—a professional expert, a dually-qualified teacher educator, and a traditional academic-type teacher educator (Gunn et al., 2015). Furthermore, we found that the nature of the “service”, “research” and “teaching” work undertaken by teacher educators was different from other academics in the university and from teacher educators who did not work in the university.

Only one of 11 teacher educator positions in our data could be interpreted as wholly a teacher educator position of the dually-qualified type (meaning the recruit would hold a teaching qualification and be registered and therefore able to undertake student teacher practicum supervision as part of their university-based ITE work, and that they held an advanced qualification—a doctorate—enabling them to research and engage in research-informed teaching within the university). There are two important factors to this. First, that only 11 positions were advertised during the six-month time frame of our data gathering suggests either a lack of mobility within the workforce or a hesitation on the part of universities to advertise full-time continuing appointments. Second, of the 11 positions, five were for teacher educators of the traditional academic-type (persons being recruited for leadership, research, university service, and teaching purposes, who were not required to hold a teaching qualification or be registered, and who would therefore not be able to supervise student teachers on practicum). Another five were for professional expert-type teacher educators, recruited for their professional, service, and teaching expertise (people able to be registered and therefore able to supervise student teachers on practicum, but not currently research able or, in some cases, expected to engage in research). Such an approach to recruitment results in divisions of labour amongst teacher educators and represents a bifurcation of the workforce that separates the professional and academic components of the work.

The division of professional and academic components of teacher educators’ work was observed again in Phase 2 of our study. It was experienced by teacher educators as a tension between meeting academic (research) and professional (teaching and service) demands. In a discussion of major contradictions in the activity system of university-based ITE, for instance, teacher educators repeatedly described difficulty in meeting their professional and academic work demands. When forced to prioritise, professionally oriented work such as teaching, teaching administration, and research administration won out. There was a sense of collective failure among our participants with respect to research. Nat said, “I differentiate research from writing … I’m really good at collecting data and doing lovely research projects … so I am meeting those goals” but producing papers for publication was difficult. Another participant, Ash, reported avoiding anything to do with “APR or PBRF in the title” but also reflected that, on the other hand, if someone were to go to the local school and enquire about Ash’s ability to teach, the suspected response would be something in the order of:

Oh well, Ash hasn’t had a class for, you know … so they don’t like me, they wouldn’t like me either … I’m fully registered … I care about teaching [general laughter] … I try to connect with schools, I try to be realistic, but it’s not like they would think I’m the most fabulous thing since sliced bread either … that’s being colloquial about it, but it does feel like that, that I’m neither fish nor fowl.

Cas, from the perspective of a professional expert-type teacher educator with a large teaching load, spoke of managing professional and academic work demands as pressure:

We were talking about the pressure of I … so those of us who have a large teaching load, we need to be seen as, being relevant. So we do find the time to go out to schools … and you can come back, and you can tell the stories. So to me, that’s super important but there’s a pressure from the other side. Even though I’m employed as a professional teaching fellow here and I’m not required, I’m not employed to write, there is still an expectation, constantly here, that we have to do that. So there’s now the pressure to not only publish, but to do your PhD.

For Sam, the problem arose from more than just the institutions (of schooling or the university). One’s intentions as a teacher educator and associated sense of identity were implicated in a perceived separation between professional and academic demands of the work:

I think it’s also how we view ourselves because I think most of us would say that we’re teachers … as opposed to being lecturer or whatever … we still need to keep on top of being current and our greatest joy is when we are going out to classrooms and teaching, or working with students. And yet, there’s the academic, you’ve got to write, you’ve got to spend a week doing your confirmation report or whatever it is, all these other requirements. And then on top of that if you take on a role, like you have Ash, where you’ve got other expectations as well, you obviously have something that’s more service-oriented as well, so, there’s all these different factions pulling in different ways, and yeah, you’ve got the imperative to do the research and do the academic writing and your heart is teaching.

Research, interpreted narrowly as writing and publishing outputs, was a troublesome dimension of the teacher educators’ work. As pointed out by Nat, organising and administering research projects was easy, similar in nature to teachers’ everyday work in administrating and organising teaching, but writing was different, difficult to make time for, and a lack of writing output, be it in the form of publications or PhD theses, was interpreted as failure. So despite the institutional requirements for many of our participant teacher educators to research, to serve, and to teach, the reality of accomplishing this range of work was fraught with difficulty.

From our data we were able to produce a set of labour demands for university-based teacher educators that reflect long accepted elements of standard academic work: teaching, research, and service. However, we found that in university-based ITE, the form of the work was expanded in comparison to other university-based and non-university-based academics.

Professional requirements for ITE programme approval require a certain percentage of teacher educators to be registered and certificated so that student teachers may be adequately supervised when on practicum. To be so professionally credentialed, a teacher educator must have had extensive successful teaching experience and be deemed professionally competent by members of the profession. University teaching typically involves academics drawing upon their own research and scholarship within teaching—an ability that implies one is not only qualified to research but also able to regularly conduct and report on research. University-based teacher educators are therefore required to be dually qualified (to teach and to research) if they are to service the full scope of university-based ITE work. Achieving and maintaining these dual sets of objectives gives an additional complexity to the work.

In addition, we found that service work comprised not only traditional institutional administration, leadership, team, and committee work but also community involvement, the maintenance of professional expertise in curriculum, pedagogy, or educational administration, and the brokering of relationships between all parties to ITE. The irony in this expanded remit of service and teaching work within university-based ITE is that again, only the dually-qualified category of teacher educator is qualified and employed for this work and few such qualified teacher educators were seen to be currently employed.

University based teacher educators’ work—What do they do? What are they working on?

We studied the practical activities and artefacts of teacher educators’ daily work when we accompanied them to work. In this section, we report our key findings about the dimensions of teacher educators’ work, the tools they used to help with the work, and their work objectives when teaching student teachers.

Work dimensions of university-based teacher educators

Work diaries were produced in which teacher educators, on two separate occasions, logged all their work activities across a single week (28 in total; not all teacher educators accomplished this task twice). Logged work was attributed to the following categories: administration, research related activity, combined teaching (including preparation for university teaching and the school-based teaching and supervision of students on practicum), and general administration. Time spent involved in the various categories was calculated for each teacher educator and re-presented to participants during post-work shadowing interviews for member checking. In most cases the accuracy of the data was affirmed, though several participants noted that the weeks that the diary was undertaken did not correspond with school-based placements and that during those peak times the work would look very different (more oriented to combined teaching).

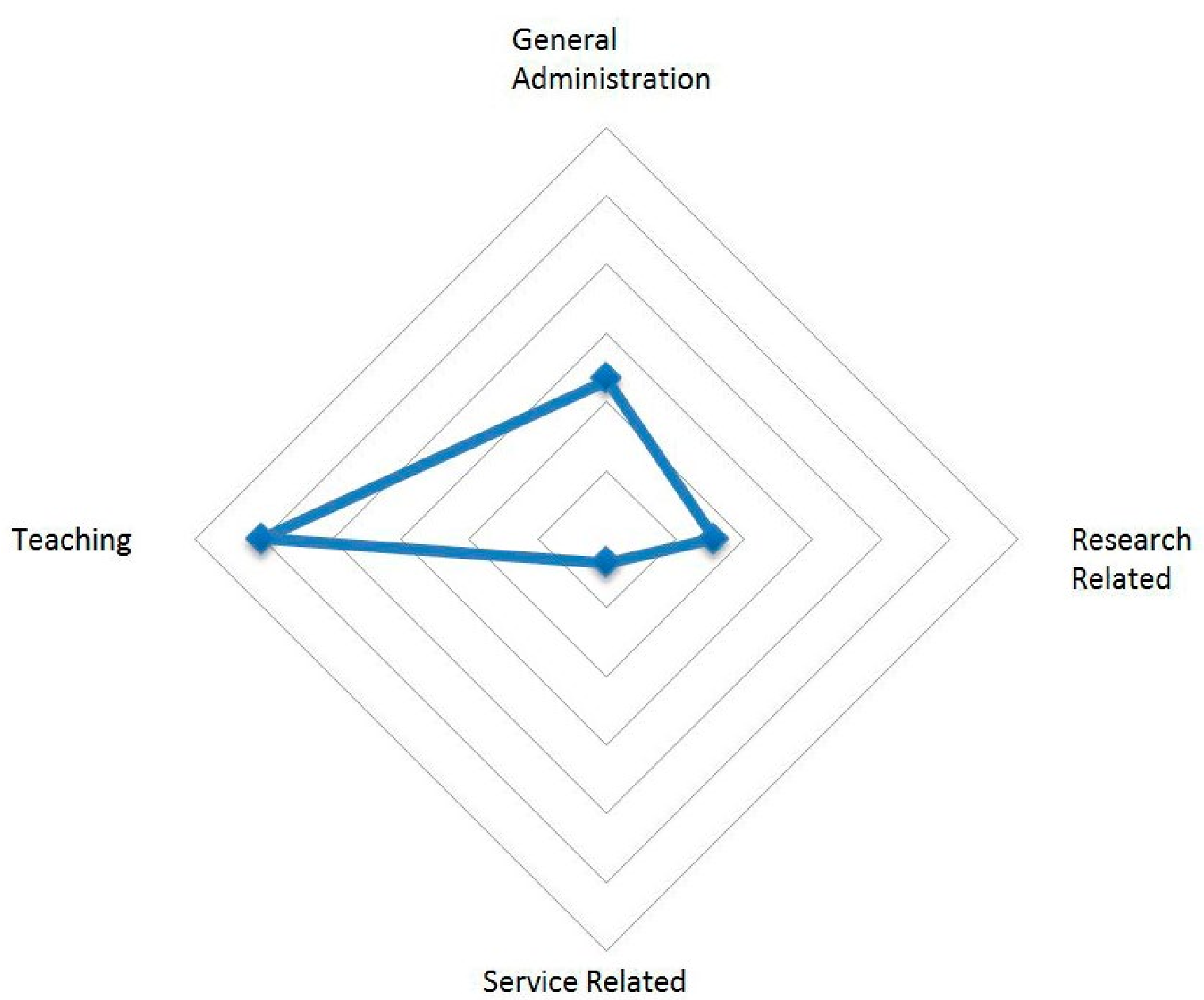

The analysis showed that the majority of teacher educators’ time was spent involved in teaching-related work. Administration was also a large component of the work. This included activities such as responding to emails, and it is likely that much of the recorded administration work was teaching-related. The analysis of work dimensions resulted in very similar attributions of work across our dimensions at both Time 1 (T1) and Time 2 (T2). For that reason we combined the work diary data to collectively represent the work of teacher educators in the activity system of university-based ITE (see Fig.1).

Figure 1: The collective teacher educator subject’s work attributions across T1 and T2 combined

We note for the majority of the participants in this study (9 out of 15) that the emphasis on teaching that was observed during T1 and T2 does not reflect the full scope of work demands asked of them—most of the participants were working within workload formulas that attributed 40 percent of their time to teaching, 40 percent to research and 20 percent to service. Possible explanations may include: the prioritisation of teaching by teacher educators (as discussed earlier); the urgent and immediate demands of teaching taking precedence over research and service work; the challenge of accurately quantifying teaching work within workload allocations; the time involved in ITE work that uses relational pedagogies and occurs with and among student teachers and school/early childhood teachers and institutions outside of the university; and the relative research inexperience of some teacher educators (especially in publishing).

Tools mediating teacher educators’ work

Because the CHAT approach is concerned with the materiality of work, we concentrated on understanding how tools mediated work within the activity system of university-based ITE. We specifically explored: workload formulas, organisers, and email. Although differently constructed in each institution, teacher educators at both universities referred to ways in which workload formulas constructed and represented their work. Sawyer commented:

[T]he university can say, well we’re being fair because this teaching’s worth this much, you can teach this many people in a class … we’ll give this much time for research because if you give this many points it equates to this many hours, yes that looks fair…

But teacher educator discussions indicated that workload formulas did not capture the work sufficiently:

It’s a neat way of accounting for what people are doing but it actually doesn’t reflect the true nature of the work that people are doing. (Sawyer)

Important aspects of the work, such as pastoral care of students and working within the profession were rendered invisible by such tools. Furthermore, participants gave examples of how these formulas led to labour divisions that sought to get the numbers right rather than making use of individual teacher educators’ particular strengths. Lou and Sawyer discussed this:

[I]f somebody for instance is really great at teaching … but other people need teaching and get given it … in preference to the people who are in actual fact really good at it … in fact the strengths of quite a talented group of people actually get washed away and everyone’s doing what they’re not feeling quite so good at, under stress … it’s perpetuated by a management model.

Teacher educators talked about how the workload tool caused them extra, stressful and unproductive work:

[S]o you end up being trapped in this cycle of watching what’s here [in your own formula] rather than being [productive], and … you can actually spend quite a lot of time on negotiations around things like this at the expense of doing other things, and they’re quite stressful things to use. (Sawyer)

Organisers and tools such as timetables placed on teacher educators’ doors, diaries, year-plans and electronic diaries were another kind of tool acting within the activity system of university-based ITE. Organisers were seen as essential due to the extremely variable tasks and self-regulated nature of teacher educators’ work. Yet they also revealed sites of tension for teacher educators. For example, universities communicated a need to block out time for research, but also reminded teacher educators regularly that they should be available to students—configuring one’s diary or year-plan to accommodate both work demands raised questions of “how”.

A third tool mediating teacher educators’ work was email. Several implicit rules about email were identified in the data: email is an official channel of academics’ work; it’s necessary to self-regulate attention to email so that one’s inbox doesn’t rule one’s work life; and, the use of email with student teachers should model professional behaviour. One teacher educator argued that it is not always culturally appropriate to use email for every communication, others discussed the fact that new technologies have encouraged their work to creep into early mornings, evenings, late into the night and through weekends and holidays—none of which appears within workload formulas.

Objects of teacher educators’ work when they were teaching

We discussed with teacher educators the range of teaching activities and artefacts they had used during their observed work. We were interested to explore what they considered themselves to be working on (the objects of the work) when they undertook selected activities and used specific artefacts with student teachers. Data pertaining to five widely observed teaching and learning activities were prepared and taken to the participatory analysis workshop for further analysis with the teacher educators. The activities were: using a technology template (with which primary sector student teachers were making pop-up greeting cards); peer feedback (in which student teachers had been asked to provide feedback to each other on a piece of work they had undertaken in class); lesson planning (a range of activities from both primary and secondary ITE classes where the teacher educator was having student teachers develop lesson plans); NZQA assessment exemplars (where student teachers were provided with NZQA assessment exemplars for NCEA achievement standards in senior secondary subjects for discussion in class); and reading templates (where student teachers were provided a reading template to assist in the analysis of an article for a class).

The teacher educators identified the following objects of their work with student teachers in relation to the teaching and learning activities analysed (as identified in parentheses):

- building professionalism/personal accountability (reading templates)

- building student teacher confidence to work within the system, before teaching design activities with their own class (technology template; knowing how to work within the assessment expectations of the system; NZQA assessment exemplars)

- building student teachers’ literacy (reading templates)

- encouraging risk-taking and creativity within a limited time frame (technology template)

- exemplifying and encouraging collaborative learning/socially constructed learning (peer feedback): “Because I can see in the way the teacher educator facilitated this, it’s very much about socially constructed learning. There are quite a lot of rules about how you relate and who relates to whom and how they do it and so on” (Ash and Sawyer).

- modeling teaching approaches/processes (peer feedback, lesson planning) although in some instances it appeared a case of “do what I say, not what I do” as exemplified in a teacher educators’ instructions to a class of student teachers about the uses of a lesson planning template:

[T]his is the teacher educator explaining the task to the students … “fill in that bit of the box, fill in that bit of the box, then fill in that bit of the box” and so I was sort of thinking oh, actually the tool has become the important thing, “fill in the blanks, this has become the important thing” [murmured agreement].

But, at the very same time the teacher educator is saying “but if this doesn’t work for you do it differently”, so there’s a real contradiction there in terms of the, learning a process [murmured agreement], and having a tool funnel the discussion so much that the learning is really fixed and singular.

- preparing beginning teachers to have agency and to be a critic of the system, able to balance compliance and critique (lesson planning, assessment):

[A]nd the teacher educator has coming through, an emphasis on lesson planning plus freedom and flexibility.(Brook)

[He/She is] trying to present these are all the things you have to do for assessment … [but is also indicating] the critique the teacher educator might have. (Nat and Chris)

- preparing beginning teachers who can give feedback (peer feedback, assessment)

- preparing student teachers for their assignments (peer feedback, lesson planning, reading template)

- producing an artefact that teacher educators could use for formative assessment purposes (reading template)

- provisioning of resources to be used in student teachers’ own teaching (technology template)

- scaffolding student teachers’ learning by providing a template (technology template, peer feedback, reading template):

She talks about scaffolding them so some good learning occurs, but he/she doesn’t talk about scaffolding them to become more independent or more responsible. Her scaffolding is “Articulate a definition”, “Give and explanation”, “Do an assignment”. (Cas)

- teaching safety practices (technology template).

As we considered the participants’ responses, we also gained insight into teacher educators’ thinking about their teaching work in the university, noting that they often felt caught between systems of the university and the profession—for example, teaching student teachers to act as critic and conscience of the profession while also upholding principles and practices within it. This tension was particularly noticeable when teacher educators discussed the teaching and learning activity that used NZQA assessment exemplars. In relation to the mirror data, Chris observed that student teachers were navigating their ways through similar contradictions:

My first feeling is about rules, there were real rules like NZQA and NCEA and subject domains and what have you, and then there were unwritten rules especially from the teacher educator about assessment drivers and practice and so on … somewhere in the middle the teacher education students are trying to navigate their way through what they have to know, [and] be able to use, and what they are picking up implicitly from [comments like], “well yeah, you have to do it this way because you might think you want to do that way BUT”—so [the student teachers are] learning the, being inducted into real teaching rather than, you know, [murmured agreement “theoretical”], theoretical teaching.

As this data demonstrates, the participatory analysis workshop was particularly rich in revealing how universitybased ITE works to produce quality graduates for the profession. Rather than seeing ITE as a linear series of practice-devoid lectures and tutorials accompanied by professional placements, these data alongside the observations we had made, revealed the absolute interdependence of professional and academic knowledge in order for teacher educators to advance their objects with student teachers in university-based ITE.

Teacher educators’ work and student teachers’ learning within university-based ITE

Two insights into the relationships between teacher educators’ work and student teachers’ learning became key as we analysed data. First, the relationship between student teachers’ learning and teacher educators’ (implicit and explicit) teaching developed significance—especially professional rules around how one should learn and/ or teach (see example earlier of the teacher educators’ instructions to student teachers about lesson planning). Second, we became interested in how the CHAT analysis revealed student teachers’ motivations towards the teaching and learning activities designed and implemented by teacher educators—because where different objects were revealed, the effectiveness of the teaching or learning could be questioned.

As demonstrated, teacher educators were working on multiple objects through their teaching. The lesson planning mirror data example, for instance, revealed teacher educators to be teaching student teachers processes for planning (across different levels and curriculum areas—which involved differentiating approaches), helping them do their assignment work, and also teaching that even though there were templates for lesson planning, teachers could develop their own. When we interviewed student teachers about lesson planning activities, they appeared to grasp just the first two of these objects, and the first one only partially:

Int.: So you’re working on lesson planning, why are you doing this lesson planning activity?

ST: Oh well because it’ll be very helpful for actual teaching, just to organise work. And also our first assignments will pretty much be a lesson plan.

Int.: Oh, okay so, you’re getting to practice the kinds of work you’re going to be expected to hand in as well?

ST: Yeah.

However, as the conversation about lesson planning evolved, a student teacher commented on the scope of learning that was occurring as a result of the activity:

Int: Do you know if this kind of tool is used in schools? Do you think teachers would use this kind of …[trails off]

ST: I know from family who are teachers that they do it.

Int.: Yeah okay, so you’ve seen it?

ST: Yeah, I didn’t understand it though.

Int.: Yeah, okay, so what are you understanding about it now?

ST: All the work that’s going into it, I mean it shows there’s quite a lot that goes into it.

Int.: Yeah because it looks like quite a simple sort of exercise on the surface, but there’s actually a lot underpinning what you’re … [trails off]

ST: Yeah.

So even though student teachers were able to comment on the utility of the activity and tools (for learning how to write a lesson plan and for doing assignments), they made no mention of the fact that they might use or design their own lesson plan to meet specific curriculum needs. An understanding of what went into lesson planning was suggested, but differentiated approaches to the process and the ability to develop one’s own tools was not.

In the reading template activity, the teacher educator’s explicit objects and those perceived by the student teachers were also different. Teacher educator’s objects were identified as having student teachers learn to find information that they could later use in an assignment, and developing student teachers’ literacy. When asked from their perspective about the reading template tool, the student teachers acknowledged that it might help them with their assignments but they were also of the view that the tool helped their learning, an insight also noticed by Cas in the participatory analysis workshop:

I thought that the lecturer’s object was for them to know the content of the readings whereas when I read the students’ [response to the activity] the object was for them learning how to learn.

The student teachers, when asked to comment about the reading template activity had commented:

ST1: I think they are [useful] because they help you to break it down in each section so you fully understand [inaudible] …

ST2: And it’s not like you’re going to zone out, ’cos when you have a reading you can easily zone out and you’re like, oh I’ve actually done the reading but you haven’t taken much out from it.

Int.: Yeah, so what does it do for you as you’re reading it?

ST1: It means that you get the important parts of it in one place and you can study like, that to that [indicating between the reading template and article], instead of like reading, where like you can … [trails off]

ST2: Yeah you can, if you’re looking for a specific part you can easily find it in a worksheet and then go find it in the reading.

ST1: Especially like when your brain’s just like, “no I’m done”, and then at least you’ve got it all there and then you can go back through the reading.

ST2: Yeah instead of going like through hundreds of pages.

Student teachers’ comments also revealed that such tools might act to limit engagement with concepts and literature, and that they may actually impede one’s own interpretive processes:

Int.: Yeah okay, so the questions that are on it [the reading template], are they given to you or are they … ? [trails off]

ST1: Yeah.

Int.: Oh they are?

ST2: Yeah, we consistently get them.

Int.: Yeah okay, is that a good thing do you think? How does that help you?

ST1: Um I think it draws your attention to the main parts of the reading.

ST2: ’Cos there’s a lot that we don’t actually need to know. ’Cos sometimes I know I’m guilty of kind of going through everything with a highlighter and thinking it’s important. So when you look at the worksheet and see what’s important, you can go like, well I thought this was really important but it’s really not so.

ST1: Or it’s less important.

Int.: Important from whose point of view?

ST2: I assume that what is pulled out will be used in terms of what is important for our knowledge and what will be used for our assessments.

Thus the dual objects of what to learn and what will be assessed emerged from the student teachers as key motivating forces for their engagement with a tool like a reading template. The broader teacher educators’ sense of purpose—for improving student teachers’ literacy—was not explicitly shared by the student teachers, and in fact, could be seen as being contradicted through the student teachers’ uses of the tool as a device to narrow what should be taken notice of from readings for their knowledge and assessments.

Student teachers’ motivations towards the teaching and learning activities designed and implemented by teacher educators

We found student teachers’ articulating a narrower range of objects in relation to the teaching and learning activities designed by the teacher educators. They were largely focused on learning how to learn (reading templates); completing assignments (lesson planning, reading templates); and preparing for “actual teaching” (lesson planning, assessment exemplars, peer feedback, technology template, reading template). At times the student teachers’ objects did align with those of the teacher educator, but if teacher educators’ objects were not recognised by student teachers, or student teacher and teacher educator objects became misaligned, the effectiveness of teaching could be open to question. An example of this was seen when some student teachers did not perceive the full range of teacher educators’ object motives during the technology template session— they viewed the time spent on the actual production of the card as non-productive. We included mention of this in the mirror-data for teacher educators during the participatory analysis workshop when we reported student teachers’ responses to the activity:

The students believed that using the template materials helped them to understand and fill in parts of the technology process. One said that this is what they don’t see in schools, “it’s the hidden work of teaching”. Another said that she would have thought that this activity was art and craft but the activity in the context of technology was helping her to see the technology aspects. Towards the end another student critiqued the use of class time for this activity, stating that she would have liked to have “take home” activities (such as this one), as this would leave more time in class to talk and ask questions about processes of planning.

Cas, when responding to the student teachers’ reported comments, said:

Well, I thought because they said things like “Should it be a take home activity, or not?” that [the student teacher was] … looking on it [just] as an activity rather than as a process for understanding teaching and learning … because they might think that’s what a teacher educator’s job is—to show them stuff to do with kids at school.

Student teachers not understanding the breadth of a teacher educators’ teaching objects reveals the importance of teacher educators explicitly communicating to their student teachers the multiple reasons and motivations for engaging them in the kinds of teaching and learning activities that they do. When teacher educators are explicit about the objects they’re working on when teaching, student teachers have an opportunity to interpret the situation and align their own objects with those of the teacher educator, or contest them—a fact not lost on Lou, as teacher educators in the participatory analysis workshop reflected on their work:

I hadn’t realised until we did this [CHAT analysis] how vastly different the student teachers may be perceiving the artefacts and processes as to what is intended, and the importance of nailing things to the GTS (graduating teachers standards), or having learning intentions up. … And I think being explicit from the word go, you know, the whole purpose of the outcome. And at the end, actually coming together and saying “What did you get, what did you learn from this, what do you want to learn more about?”

Major implications for practice

Universities’ employment practices, workforce planning, and the promise of university-based ITE

We accept that university-based ITE straddles two major policy environments: higher education and initial teacher education, and that university-based ITE is intersected by multiple activity systems, policies, and practices (those of schools and early childhood settings, the profession, the broader education community, and so on). The historical evolution of ITE in New Zealand means that universities have been offered an opportunity to support system-wide improvement and to contribute substantially to an evidence base for high quality ITE. However, the findings of our study suggest that this may be jeopardised in the longer term if change does not occur. The category of university academic worker known as teacher educator has, by virtue of their professional and scholarly expertise, obligations to both the academy and to the profession. These must both be supported by employment practices and conditions within university-based ITE. With a bifurcated workforce of those who can research but not teach (in schools and early childhood settings) and those who can teach but not research, university-based ITE will do little to disrupt historical divisions between theory/practice, research/ teaching, and academic/professional, and the opportunity to expand teaching (be it in the university or in early childhood education or school settings) through research-informed and evidence-based practice will be lost.

What have we learned about teacher educators’ work within the activity system of university-based ITE?

Workload formulas, organisers, email, and such tools communicated expectations to teacher educators about their work and created contradictions in the activity system of university based ITE. In this study, teacher educators strove to meet both the explicit expectations of the university and their own implicit rules about what it takes to be a professional teacher educator. This resulted in stressed dually qualified and professional experttype teacher educators working on multiple objects, some not even within their current formally agreed role. A clear example of this was seen with professional expert teacher educators, who, even when their employment contract did not include a research component, were driven to engage in research so their teaching was research-informed, for career prospects, and so they could access funds for conference attendance which they needed for professional development and networking purposes—both of which advantaged the university-based ITE activity system. Dually-qualified teacher educators worked at meeting university research expectations (tied to published outputs), teaching, and service, while also maintaining professional teaching credentials (registration and certification) so student teacher visiting work could also be achieved. Teacher educators in this project felt under a great deal of pressure to serve the multiple simultaneous objects of their work, and their health and well-being suffered. As well as providing healthy and safe work policies and environments, we think universities would be well advised to involve teacher educators in considering how such work contradictions and demands might be tackled. Simply dividing the labour between traditional academic and professional expert-type teacher educators threatens to extend rather than reduce the theory–practice gap and does little to ensure the long-term sustainability of the professional education of teachers within the university system.

Another implication from this project’s findings relates to the accelerated push for electronic systems to regulate, mediate, and communicate teacher educators’ work. As reported, email was a significant tool for mediating work within the activity system of university-based ITE. But other electronic tools were evident in the findings also. East University, at the time of the study, was implementing a learning management system that would do away with all paper documentation for teaching and require all readings and assignments to be electronically communicated. Such systems can be institutionally efficient but have implications for the ways teacher educators interact with student teachers—fundamentally shifting the locus of the relationship from a face-to-face to a technologically mediated one. While neither we nor our participants are by any means technophobes, the take-up of these tools is changing the way teacher educators do their work, and the work itself. We caution against the ad hoc headlong rush into new hardware and software platforms, arguing that both the intended and unintended consequences of such changes must be considered.

What have we learned about the relationships between teacher educators’ teaching and student teachers’ learning within university-based ITE?

This study has provided an opportunity to better understand how student teachers within university-based ITE respond to and engage with teacher educators’ work in the service of their own learning. The research design allowed us insight into the professional intersubjectivity between teacher educators and student teachers as they shared teaching and learning experiences. We identified a range of objects being worked on by teacher educators and saw how these related to student teacher learning. With the use of some tools reaching “rule” status (e.g., teacher educators’ strong guidance about uses of tools like planning templates or use of assessment exemplars), a critical examination of how teacher educators use such tools would appear timely. The CHAT framework has helped us to explore the objects that teacher educators and student teachers pursued when teaching and learning within university-based ITE. We have identified a potential for misunderstanding and/or contradiction between teacher educator and student teacher objects that may limit student teachers’ learning. We believe that teacher educators and student teachers need to make their objects explicit, and that opportunities to check on shared understandings be designed into teaching and learning experiences.

Project limitations

In Phase 2 of our study, we have sampled work practices, activity systems, and professional life histories of a group of teacher educators working within two of New Zealand’s seven universities where ITE is currently offered. Between us, the research team has recently worked within four of these seven settings, and the practices and issues raised within this study resonate with our own and our participants’ experiences of university-based ITE across many universities. However, the research findings produced in the course of this study are particular to those sites within which they were generated, and of a particular time period.

Our recruitment for Phase 2 of the study did not result in the “traditional academic”, as we termed it in Phase 1, being recruited into the study. One of our participants, Chris, was a dually qualified teacher educator, but by virtue of having taken up a leadership role, Chris had relinquished student teacher visiting for the time being and was therefore working in the domains of university teaching, service, and research only. The fact that no traditional academic-type teacher educator was recruited means that we did not develop a sense of how their everyday work was similar to or different from other teacher educators. Perhaps with no requirement to visit student teachers as part of their work, these academics did not see themselves as teacher educators and therefore disregarded the possibility of participating in the study. Or perhaps they were not willing or able to participate because of their own work demands. In any case, studying these academics’ work would provide a fuller insight into the scope of work required within university-based ITE and of the academics whose work is in the field.

Conclusion

We have argued that university-based ITE offers rich opportunities for research-informed teaching and the generation of new knowledge for education based on strong partnerships between universities and the profession of teachers (including the student teachers whom teacher educators work with in university classrooms). We also claim that student teachers’ learning within university-based ITE will be advantaged, and that practices of ITE developed, when teacher educators work more purposefully to reveal their own and student teachers’ object within teaching and learning experiences. Our study has pointed to some key contradictions in the activity of university-based ITE. With such knowledge, we have the means to act for change. Engeström theorises a form of knowledge called “possibility knowledge” (2007, 2013), describing it as something that “opens up insights into what may be possible in a human activity and what alternative directions of development and change are available” (2013, p. xvii). For him, possibilities are created and articulated by those whose lives are imbricated in the forms of activity under scrutiny, in our case, teacher educators and student teachers working within the activity system of university-based ITE. As this project has shown, the CHAT approach and the promise of Engeström’s developmental work research (DWR) provide for development and learning, led from within. As people recognise and work with contradictions in their shared activity, they are able to develop new solutions and become motivated towards longer-term sustainable change. For us, there is much potential in teacher educators investing in such forms of enquiry because as our project has shown, the largely enforced expansion to the activity system of ITE through its relocation into the university sector has resulted in troubling work practices and system contradictions that must be challenged from within if change is to occur.

We think that CHAT and DWR provide tools for setting university-based ITE activity and its subjects into motion.

Reference List

Andreotti, V. & Major, J. (2010). Shifting conceptions of knowledge and learning in initial teacher education in Aotearoa/New Zealand. Journal of Education for Teaching: International Research and Pedagogy, 36(4), 441–459.

Anthony, G., & Kane, R.(with Bell, B., Butler, P., Davey, R., Fontaine, S., . . . Stephens, C.) (2008). Making a difference: The role of initial teacher education and induction in the preparation of secondary teachers (Summary Report). Wellington: Teaching & Learning Research Initiative, New Zealand Council for Educational Research.

Brennan, M., Everiss, L. & Mara, D. (2010). An exploration of field-based early childhood teacher education in Aotearoa New Zealand (Final Report). Wellington: Teaching & Learning Research Initiative, New Zealand Council for Educational Research.

Ellis, V., Blake, A., McNicholl, J., & McNally, J. (2011). The work of teacher education, Final research report. WOTE phase 2. Oxford: Department of Education, University of Oxford.

Ellis, V. Glackin, M., Heighes, D., Norman, M., Nicol, S., Norris, K., Spencer, I. & McNicholl, J. (2013). A difficult realization: The proletarianisation of higher education-based teacher educators. Journal of Education for Teaching: International Research and Pedagogy, 39(3), 266–280.

Engeström, Y. (2001). Expansive learning at work: Toward an activity theoretical reconceptualization. Journal of Education and Work, 14(1), 133–156.

Engeström, Y (2007). From stabilization knowledge to possibility knowledge in organizational learning. Management Learning, 38(3), 271–275.

Engeström, Y (2013). Foreword: Formative interventions for expansive learning. In, J. Virkkunen & D. S. Newnham, The change laboratory: A tool for collaborative development of work and education, (pp. xv–xviii), Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

Gunn, A. C., Berg, D., Hill, M. F., Haigh, M. (2015) Constructing the academic category of teacher educator in Aotearoa New Zealand university recruitment processes in Aotearoa New Zealand. Journal of Education for Teaching: International research and pedaogy, 41(3), 307-320.

Haigh, M., Aitken, S., Ala’alatoa, B., Chandler, S., Ell, F., Grudnoff, L. … Vilers, H., (2013). Are they ready to teach? Assessing student teachers’ final practicum, Summary Report). Wellington: Teaching & Learning Research Initiative, New Zealand Council for Educational Research.

Hill, M., Cowie, B., Gilmore, A., & Smith, L. (2010). Learning to become assessment capable teachers. Wellington: Teaching & Learning Research Initiative, New Zealand Council for Educational Research.

Kane, R. (2005). Initial teacher education policy and practice (Final report). Wellington: Ministry of Education.

Ministry of Education, (2013, June). Request for application for provision of exemplary postgraduate initial teacher education programmes. Wellington: Author.

Murphy, T., Edlin, A., Everiss, L., McClew, J., Margrain, V. & Meade, A. (2005). Effective teacher education practice: The impact of written assessment feedback for distance learners. Wellington: Teaching & Learning Research Initiative, New Zealand Council for Educational Research.

Nuttall, J., Brennan, M., Zipin, L., Tuinamuana, K., & Cameron. L. (2013). Lost in production: The erasure of the teacher educator in Australian university job advertisements. Journal of Education for Teaching: International Research and Pedagogy, 39(3), 329–343.

Ord, K. (2010). Bodies of knowledge: Early childhood teachers’ experiences of their initial teacher education programme and sense of preparedness for teaching (Doctoral thesis). Massey University, Palmerston North.

Parata, H. (2012, 16 May). Building a brighter future: Budget 2012—Extra $511.9 million for education. [Press Release]. Retrieved from www.national.org.nz/Article.aspx?articleId-38507, accessed 25/03/13.

Parata, H. (2013, June). Quality teaching agenda: Transformation of the New Zealand Teachers Council into a professional body for the 21st century. [Cabinet paper]. Retrieved from http://www.minedu.govt.nz/~/media/MinEdu/Files/TheMinistry/ NZTCReviewProposals2013/CabinetPaperTransformationOfTheNZTC.pdf

Purdue, K., Gordon-Burns, D., Gunn, Alexandra C., Madden, B. & Surtees, N. (2009). Supporting inclusion in early childhood settings:Some possibilities and problems for teacher education. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 13(8), 805–815.

Virkkunen, J. & Newnham, D S. (2013). The change laboratory: A tool for collaborative development of work and education. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

Yamagata-Lynch, L. C. (2010). Activity systems analysis methods: Understanding complex learning environments. doi:10.1007/978-1-44196321-5_2, Springer Science+Business Media.

Author information

|

David Berg, BA Hons. (Lancaster), MSc (Liverpool), EdD (Otago), the University of Otago, College of Education. I have a longstanding interest in and commitment to effective teaching and learning in pre-service teacher education. This has grown from my experience as a deputy principal and pre-service teacher mentor/ coordinator in a large primary school in the United Kingdom. This interest has been further developed in my role as a pre-service teacher educator/lecturer in both New Zealand and the United Kingdom. My doctoral research explored the teacher efficacy beliefs and concerns about teaching of pre-service teachers. This research considered how pre-service teachers formed these beliefs and in so doing identified the part that teacher educators play in the development of teachers with healthy and robust beliefs. |

|

Alexandra Gunn, Dip.Tchg.ECE (Dn.), B.Ed (Otago), MA (Cant.), EdD (Waik.), the University of Otago, College Of Education. My interest in initial and ongoing teacher education has been with me for many years and is expressed through a strand of research involving relationships between teachers’ beliefs, conceptions, and practices. I have also contributed to teacher education across the last 20 years through my work at the former Christchurch College of Education, University of Canterbury and now University of Otago. The opportunity to pick up the Work of Teacher Educators project and add to the international picture of teacher education work in these partner countries is one I welcome. |

|

Mavis Haigh, BSc (Auck), BA (Auck), PhD (Waik), DipTchg (Auck), the University of Auckland, Faculty of Education, School of Learning, Development and Professional Practice My professional and research interests revolve around educating quality teachers. Current research projects include investigating how we judge student teachers’ readiness to teach, how teacher educators build their research capability, and how using a complexity theory and critical realist frame can assist us to rethink teacher education to improve learning outcomes for all learners. |

|

Mary Hill, BA (Vic. Wgtn.), Med (Waikato), PhD (Waikato), DipTchg (Wgtn), the University of Auckland, Faculty of Education, School of Learning, Teaching and Development My passion is educating teachers who effect successful learning for all children. This theme drives my research as well. Current projects include investigating how student teachers learn about assessment, how teacher educators build their research capability, and how using a complexity theory and critical realist frame can assist us to rethink teacher education to improve learning outcomes for all learners. Participating in the Work of Teacher Educators project will provide a new lens to understand, extend and improve teacher education for this purpose. |

For further information about the project email alex.gunn@otago.ac.nz

(Endnotes)

1 Object as it is used here and throughout the report reflects the specific interest within CHAT of the object-centredness of actions (Engeström, 2001) which are thought key to understanding what people are doing and why. Object is taken to mean the objective or objectives of activity as understood by the person or persons working on it.